#The Countess of Chester

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

When doctors warned that she might be a killer, hospital bosses took her side — offering to support her with a master’s degree and find her a role at a top children’s hospital. This is the inside story.

By: Shaun Lintern and David Collins

Published: Aug 19, 2023

Lucy Letby sat with her parents in a meeting with senior managers at the Countess of Chester Hospital, where she worked, waiting patiently for an apology. She had prepared a statement that was read out by her parents to Tony Chambers, the hospital’s chief executive, about being bullied and victimised on the neonatal unit.

It was December 22, 2016, and for the previous 18 months, two doctors on the unit had been trying to find an answer for a series of mysterious deaths of babies. Their detective work had led them to a single common denominator: Letby. The neonatal nurse had been on shift for each of the incidents.

Rumours of a killer on the ward had spread and Letby had complained about the doctors and their finger-pointing, claiming she was being wrongly blamed.

Chambers, who had trained as a nurse, was convinced by Letby’s account, and in front of her parents, John and Susan, offered sincere apologies on behalf of the hospital trust. The doctors in question would be “dealt with’’.

Except the doctors were right. By that point Letby had secretly murdered seven babies and tried to kill six more, one of them twice.

Last week a jury sitting at Manchester crown court found her guilty following a ten-month trial. She was cleared of two attempted murders and the jury was unable to reach a conclusion over charges of attempted murder relating to four other babies.

An investigation by The Sunday Times, based on a cache of internal documents, can now reveal in detail how the hospital delayed calling the police for months and that senior management, including the board, sided with Letby against doctors after commissioning perfunctory investigations.

The files, including the outcome of a grievance case that Letby brought against the trust in September 2016, reveal that an apology from the hospital and the doctors was not all the 33-year-old got. She was also to be offered a placement at the world-famous Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool and was to be given support for a master’s degree or advanced nurse training.

The grievance report details how consultants first raised concerns with board directors in 2015 and that doctors had been heard referring to “killing” on the ward.

One doctor was said to have described a “drawer of doom” containing links between Letby and as many as 16 unexpected deaths and collapses of babies on the neonatal unit. Another told the ward manager: “You are harbouring a murderer.”

But Ian Harvey, the medical director, told the grievance the trust wanted to “protect Lucy Letby from these allegations”. A senior nurse, Karen Rees, had told Letby “the intention was to get her back onto the neonatal unit”.

Some doctors were threatened with misconduct investigations and their attempts to escalate their worries were met with angry responses. One nurse described the consultants as conducting a “witch-hunt” against Letby.

Responding to the Sunday Times investigation, Susan Gilby, the former chief executive of the trust, said a full public inquiry was required. She said she knew within a week of arriving at the trust, in 2018, that police needed to be involved.

She said managers “had a very fixed view” and the paediatricians were “clearly psychologically in distress” when she arrived at the trust a month after Letby’s arrest.

Along with the then trust chairman Sir Duncan Nichol, Gilby commissioned an independent investigation of the trust’s handling of the Letby scandal by the consultancy firm Facere Melius. Nichol has called for it to be published and said he believes the trust board were misled by hospital executives.

First suspicions

In June 2015, Dr Stephen Brearey, a senior paediatrician and head consultant at the hospital’s neonatal unit, was trying to work out why four relatively healthy babies on his unit had “collapsed” — suffered a catastrophic and unexpected decline in their health — for no clear reason in a fortnight. Three babies had died; one had been saved. That is more than they would normally expect in a year.

Brearey, a calm, measured, clear-headed consultant, decided to open up the medical notes for each case to examine one by one their care on the ward.

He noted the doctors and nurses on duty, the times of the collapses, and the people in the room at the time. Letby was the only one at each of the four collapses.

The nurse, then 26, had a wide circle of friends at the hospital. “She was like Miss Perfect,” said a former friend. “Maybe slightly awkward, but sociable. She’d go on nights out with the hospital staff into bars and nightclubs in Chester. Her parents used to think butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth. She’s literally the last person anybody would suspect as a killer.”

She was a godmother to two children, did salsa classes, went on holiday to Ibiza with friends, and lived in a £200,000 semi-detached house close to the hospital with her two cats, Smudge and Tigger. She had grown up in Hereford, and went to Aylestone School, a state secondary, before moving to Hereford Sixth Form College. She graduated in 2011 and started at the Chester hospital in 2012.

She also had an alleged close relationship with a married registrar. He had driven her home the night one of the babies died, and it was claimed in court that many of her actions were motivated by a desire to be noticed by him. Records showed she had searched for his wife on Facebook, and had sent him heart emojis in a WhatsApp message.

Letby’s first murder was of a one-day-old boy known as Child A, on June 8, 2015. Delivered by caesarean section at 31 weeks, he had been admitted to the intensive care room at the neonatal unit, but was in good condition and breathing without help.

An hour after starting her shift, Letby called doctors to the baby’s incubator because his health had suddenly deteriorated. Both a doctor and a consultant noticed an odd discolouration on the boy’s skin — patches of pink over blue skin that appeared and disappeared — but had no idea what it could be.

Letby had injected air into the baby’s bloodstream through one of two tubes attached to his body, in what would become a tried and tested method of killing for the nurse.

Despite resuscitation attempts, Child A was pronounced dead at 8.58pm. A day later, Letby targeted Child A’s twin sister, Child B, using a similar method of air injection. She too suffered an unexpected collapse, but survived with no long-term consequences. On June 14, Letby murdered a five-day-old baby, Child C, using an injection of air through a nose tube.

Seven days later, she killed Child D, with an injection of air into the bloodstream. The baby collapsed three times in the early hours, and could not be saved.

All Brearey had was a suspicion that something was amiss. Healthy babies, no matter how premature, do not collapse and die for no reason. In neonatal units it is accepted that sudden unexplained deaths of babies is rare.

Brearey’s informal review of what had happened to Children A, B, C and D was shared with his colleague, Dr Ravi Jayaram, a consultant paediatrician in the children’s ward, who once presented Channel 4’s TV show Born Naughty?, a programme about children with behavioural problems. Brearey told Jayaram there was nothing that linked the deaths, “other than one nurse”.

The deaths were reported by consultants to the hospital trust’s committee for serious incidents, responsible for examining matters of patient safety. But the hospital classified them as “medication errors”, rather than a “serious incident involving an unexpected death”.

Had they been classified as unexpected deaths, NHS England policy would have allowed the hospital to group them together, which could have led to an immediate further investigation about what had caused them.

New ways to kill

In the early hours of August 4, Child E, a twin boy, collapsed and died. Letby had injected air into his bloodstream. The next day she used insulin to try to poison the baby’s twin brother, Child F. He survived.

Letby was becoming more prolific, and she started experimenting with her killing methods. In September, she twice tried to murder Child G, by feeding him an excessive amount of milk. The baby was left severely disabled.

On October 23, Child I died. Letby had injected a large amount of air into her stomach via a nasogastric tube. She sent a sympathy card to her parents and made Facebook searches for the family.

The same day as Child I’s collapse, Eirian Powell, a nurse and ward manager responsible for the nursing staff on the neonatal unit, conducted her own review of the cases. Like Brearey, she spotted that Letby was the only member of staff on shift for all the deaths. She emailed her findings to Brearey.

“Unfortunate that Lucy Letby was on — however each case of death is different,” she told him. By now, doctors and staff on the unit were gripped by fear and confusion. What was going wrong?

By November 2015, Ian Harvey, the hospital’s medical director and second in charge overall, was aware of the rising death rate on the neonatal unit. He felt assured, however, that the hospital had a mortality rate lower than or comparable with other similar-sized hospitals.

Joining the dots

In February 2016, Brearey, who remained suspicious of Letby, carried out a half-day thematic review into the deaths and collapses on the neonatal unit. With the help of a specialist consultant from Liverpool, he tried to join the dots.

The working group produced a report detailing complex clinical issues alongside a mortality table and an appendix. The appendix, which was reproduced in a police report, showed Letby was on shift for each of the deaths and collapses and that they had happened only between midnight and 4am.

On February 15, Brearey emailed a table of deaths, showing Letby on shift for each one, to Harvey, who as well as being medical director, had been a respected orthopaedic surgeon. Still there was no action and hospital management, believing Letby’s involvement was a coincidence, allowed her to continue her work at the neonatal unit.

Brearey continued to be concerned and emailed Jayaram. “I think we still need to talk about nurse Letby . . .”

The head nurses at the hospital were also emailing each other. On March 17 Powell, the neonatal unit’s ward manager, emailed the hospital’s chief nurse, Alison Kelly, and they discussed how Letby was a “commonality” in all the deaths. Powell asked for help.

Her plea went unanswered and she twice had to chase for a meeting, getting one 56 days later.

On April 7, Powell moved Letby from night to day shifts, telling her it was to support her “wellbeing” because she had been present for so many of the collapses. Two days after the switch, Letby attacked twin baby boys. She attempted to murder Child L using insulin and Child M was injected with air. Both survived.

These attacks would become a cornerstone of evidence in the police and prosecution’s case against her. The prosecution was able to show the jury that the deaths and collapses “followed” Letby from night shifts to day shifts.

Powell was feeling under increasing pressure. The neonatal unit was busy and understaffed. Stressed and anxious nurses were at breaking point. Internal emails from a consultant to Chambers warned of doctors working shifts of more than 20 hours. And the Letby rumours showed no sign of going away.

At the beginning of May 2016, Brearey emailed Kelly, the chief nurse, flagging Letby’s presence at the deaths and also asking for a meeting. Kelly sent it to Harvey, the medical director, expressing alarm that a doctor was implicating a nurse and told him she had been reassured there was no evidence but that a wider review might be needed.

She asked senior nurse managers to examine any staffing trend linked to the deaths, adding that it was “potentially very serious”.

After the exchange of messages, Brearey and other doctors met Kelly and Harvey to set out their concerns. They agreed to review all deaths and to keep Letby on day shifts for three months.

Doctors remained concerned. In one meeting with Powell on May 16 a senior doctor told her: “You are harbouring a murderer.”

A few weeks later, in June, Letby tried to murder Child N, a baby born at 34 weeks with mild haemophilia, a blood disorder. She injected him with air and a clear fluid into his stomach via a tube.

‘Back with a bang’

In June 2016, Letby travelled to Ibiza for a week-long holiday in the sun with two close friends. She returned to work on June 23, texting a friend the day before: “Probably be back in with a bang lol.”

Within 72 hours, she murdered two triplets Children O and P. Child O suffered “trauma” akin to a road traffic accident that damaged the liver. Both babies had air in the stomach via a nasogastric tube that would have put pressure on their diaphragm, making it difficult to breathe.

The latest unexpected deaths proved traumatic for the neonatal unit. Brearey held a staff debrief, but noticed Letby did not seem upset at all. He decided he wanted Letby off the ward.

On June 24, he called the hospital’s nursing director, Karen Rees, and expressed concerns about Letby being on duty. He wanted to stop her working.

Brearey told the trial that Rees insisted there was no evidence against Letby and said she would take responsibility for allowing the nurse to continue to work.

Claims of a witch-hunt

June’s deaths caused a flurry of emails and meetings between doctors, nurses and hospital executives. “[We need] help from outside agencies . . .” one doctor emailed. “I believe it is the police.”

Jayaram replied to the email chain, with Harvey, the hospital’s second in command, copied in: “They [the hospital directors] do not seem to see the same degree of urgency as we do.”

Harvey replied, denying a lack of action and saying concerns were being “discussed and action taken”. He told the doctors: “All emails will cease forthwith.”

At the end of June, the executive directors met and sources say they debated for the first time calling in the police, with notes from the meeting recording “all say yes to the police”. The discussion went on to consider the impact of an investigation and the arrest of Letby and the “subsequent reputational issues” and impact on the trust.

The evidence was circumstantial and directors had concerns about the unit leadership and fears the doctors were carrying out a “witch-hunt”.

Kelly, the chief nurse, contacted the Nursing and Midwifery Council for advice about Letby and whether to refer the problems to the police.

The trust did not contact the police. But the board agreed to downgrade the unit so the sickest babies were sent to neighbouring hospitals. This was designed to relieve pressure on the unit.

In late June, Harvey and Chambers, the chief executive on a salary of £160,000 plus benefits, decided to ask the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) for an independent review. The parameters were set narrowly and did not specifically ask the experts to look at Letby’s actions or the deaths but to carry out a general review of the service.

Harvey and Chambers met the doctors and told them the trust had considered calling the police but would handle the situation “in a different way”.

Letby was called to a meeting with a senior nurse and HR manager. For the first time, she was told of her link to the baby deaths and that she would be one of several staff placed under supervision. She was visibly “upset” and “distressed”.

Staffing shortages meant she could not be supervised on the ward and in mid-July she was redeployed to an administrative role. She never returned to the unit, despite her best efforts.

On July 14, the trust board held an extraordinary meeting at which the neonatal unit was the only item of discussion. Jayaram and Brearey presented their concerns. Discussions included the link between Letby and the unexplained deaths and the possibility of involving the police. The board also discussed installing CCTV.

One source said the doctors were told that calling in the police would mean “blue tape everywhere and the end of the unit as well as the trust’s reputation”. The next day, a non-executive director, James Wilkie, went to Kelly with concerns following the board meeting. She agreed to escalate his concerns.

Letby’s grievance

At the start of September, the RCPCH arrived. Letby was one of the first to be interviewed. She hoped that engaging with the review might help her back to a frontline nursing role.

At the same time she was fighting back against the doctors she claimed were falsely blaming her for the deaths. On September 7, she raised a formal grievance against the trust for victimisation and discrimination. She said she felt she had been singled out, moved away from the job she loved, and the hospital trust had not been honest about doctors’ allegations against her.

Her Royal College of Nursing (RCN) union representative emailed hospital bosses outlining “grave concerns” about her treatment. Letby was demanding to know the grounds for an investigation into her practice.

In October, the RCPCH reported back to Chambers and Harvey. They found that what had happened “appears unusual and needs further inquiry to try to explain the cluster of deaths”. They recommended a forensic review of each death but it never happened.

The review also found that not all the deaths had been classed as serious incidents and some were not sent for post-mortem examinations, despite this being best practice. It also found gaps in staffing and poor decision-making. But it did not explain why babies had died.

Harvey contacted Dr Jane Hawdon, an expert neonatalogist at the Royal Free Hospital in north London, asking her to examine the deaths, but she told him she could offer only a summary.

Another consultant at Alder Hey told Harvey he should commission an expert review. Three separate experts had now advised him to do this.

A draft version of the RCPCH report, including a confidential section linking the baby deaths with Letby and the “subjective” concerns of the doctors, was drawn up but only a redacted version was circulated to the board, the doctors or bereaved parents.

When Letby lodged her grievance complaint in September 2016, it started a two-and-a-half-month investigation into her treatment by the hospital and, in particular, the consultants. Documents show that in particular she wanted to know what allegations were being investigated about her.

Doctors who had raised concerns about her being a baby killer, including Brearey and Jayaram, were forced to sit through interviews, along with their union reps, where an investigator grilled them about Letby’s bullying complaint.

By now, the relationship between seven senior consultants and the hospital’s management had deteriorated. The doctors felt they had not been listened to and police needed to be brought in.

In October, the executive managers met again and sources say they were told “not calling police was the right decision” and that the doctors’ evidence was “unconvincing”.

Ten hospital staff were interviewed as part of Letby’s complaint. Many of them had threatened to call the police if she was allowed back on the ward.

Not everybody agreed with them, however. One senior nurse gave evidence saying the doctors were operating “a witch-hunt”, adding: “I hope she returns to the unit . . . we would be delighted.”

Harvey is quoted as saying the doctor’s concerns felt “purely circumstantial . . . we wanted more if we were going to call the police”. He said the executive team felt strongly that if they raised concerns with the police without foundation, Letby would have been arrested which would have resulted in a “bomb-site” for the trust to manage.

As part of the grievance, investigators looked into Letby’s conduct too. The formal report found no concerns about her competence. “No red flags,” according to documents.

The grievance process had found no evidence to justify calling in the police. In fact, it found the doctors were at fault for suspecting her of murder. “This behaviour has resulted in you, a junior colleague and fellow professional, feeling isolated and vulnerable, putting your reputation in question,” the grievance inquiry told Letby. “This is unacceptable and could be viewed as victimisation.”

The report said the hospital would aid her professional development by supporting her wih a master’s degree or an advanced neonatal course. She was also offered weekly welfare meetings with a senior nurse. Documents show that hospital managers proposed offering her an observational role at Alder Hey.

On November 12, the investigation was completed, and three days later, HR and senior nurses discussed Letby’s possible return to the neonatal unit, which had not suffered a single mysterious death or collapse since her transfer more than four months earlier.

Three days before Christmas 2016, Letby and her parents arrived at the hospital. Chambers issued her with a full apology on behalf of the hospital trust, and assured her family that the troublesome doctors who had victimised her would be dealt with accordingly.

Letby had had her revenge.

Bosses back nurse

In January 2017, the hospital held an extraordinary board meeting, at which the board, chaired by Sir Duncan Nichol, was updated on the RCPCH review.

Nichol was a career hospital administrator and head of the NHS at the time of the Beverley Allitt scandal. Allitt was the serial killer nurse who injected infants with insulin and air bubbles. She was given 13 life sentences in 1993. Copies of the redacted report were handed out at the start and taken in at the end.

Harvey said that the report had found the incidents in the ward were down to “issues of leadership, escalation, timely intervention” and that it “does not highlight any single individual”. He said some case reviews were continuing but were not expected to change that finding.

The doctors were not invited to the board, and a victim impact statement from Letby’s grievance was read out. “There was an unsubstantiated explanation that there was a causal link to an individual,” Chambers, the chief executive, said. “This is not the case and the issues were around leadership and timely clinical interventions.

“As a board we did nothing wrong,” Chambers said, with Harvey adding the trust was “close to drawing a line” under their investigations.

Chambers described the behaviour of the doctors as “unprofessional” and told Nichol he was “seeking an apology from the consultants”.

By now, Brearey and Jayaram, along with five other clinicians, were being backed into a corner by management.

In January they met Chambers and Harvey and were told: “Things have been said and done that were below the values and standards of the trust.”

Managers also demanded “mediation” between Letby and the two lead doctors, Brearey and Jayaram. Harvey told them it would protect them from a referral to the General Medical Council (GMC), the doctors’ watchdog.

Their BMA union rep told them that while there were “disturbing similarities to Beverley Allitt” they should agree to write Letby an “apology letter”.

They reluctantly agreed, but behind the scenes kept trying to find an explanation for the deaths.

In late January, they wrote to Chambers asking for a full investigation: “What is the reason for the unexpected and unexplained deaths? What should we as paediatricians do now?”

On February 5, The Sunday Times reported that deaths in the baby unit at the hospital were being investigated.

In a letter to Letby dated March 1, all the paediatricians apologised. “We are sorry for the stress and upset that you have experienced in the last year,” they wrote.

On March 27, Brearey again told the hospital’s most senior managers that it was time to bring in the police. Chambers finally requested a formal investigation in a letter to the chief constable of Cheshire police on May 2, 2017. Two weeks later, after meeting the doctors, police launched Operation Hummingbird.

‘I am evil’

Letby was arrested on July 3, at her home in Chester. In her home, police discovered hospital paperwork relating to some of the babies she had murdered. They also found erratic scribbles on pieces of paper: “I don’t deserve to live. I killed them on purpose because I’m not good enough. I am a horrible evil person.” Then, in capital letters: “I AM EVIL I DID THIS.”

In November 2020 she was charged with the murders and attempted murders. Her trial began in October last year.

Her defence team always argued that she was a victim of coincidence and of a conspiracy by doctors. They said the neonatal ward was poorly run and dirty.

Inside a glass-windowed box at the back of the court, Letby showed little emotion as the prosecution and medical experts described how she murdered baby after baby on the ward. Her parents attended every day.

The attention of the police will now focus on Letby’s activities at Liverpool Women’s Hospital where she had worked briefly before Countess of Chester — Hummingbird is investigating the entire time Letby was employed as a nurse. Cheshire police are supporting an unknown number of families affected by their new inquiries, and serious questions remain for the NHS and Countess of Chester Hospital about how Letby was allowed to kill for so long.

Almost immediately after Letby’s arrest the doctors started to find justice. Trust sources say Harvey was criticised for his secrecy during a private meeting of the board, and then Chambers wrote to the doctors.

He said: “The issues were the most intellectually and emotionally challenging sequence of events I have ever had to manage in my professional career and I am sure I have been found lacking.”

In August 2018, Harvey retired from Countess of Chester. A month later Tony Chambers resigned after agreeing a non-disclosure agreement with the trust.

The Countess of Chester Hospital said it welcomed the announcement of an independent inquiry. Jane Tomkinson, the acting chief executive, said: “The trust will be supporting the ongoing investigation by Cheshire police. Due to ongoing legal considerations, it would not be appropriate for the trust to make any further comment at this time.”

Sir Duncan Nichol was head of the NHS when the serial killer nurse Beverley Allit was convicted and was tasked with writing to all hospitals following an inquiry into that case to ensure similar failings never happened again.

He said: “We were told explicitly that there was no criminal activity pointing to any one individual, when in truth the investigating neonatologist had stated that she had not had the time to complete the necessary in-depth case reviews. We were not given the full information we needed.”

In a statement Chambers said he would co-operate with the inquiry, adding: “What was shared with the board was honest and open and represented our best understanding of the outcome of the reviews at that time.”

He added: “All my thoughts are with the children at the heart of this case and their families and loved ones at this incredibly difficult time. I am truly sorry for what all the families have gone through. As chief executive, my focus was on the safety of the baby unit and the wellbeing of patients and staff. I was open and inclusive as I responded to information and guidance.”

After the trial it was reported that Harvey, who retired to France in 2018, said his comments to the board were true to the best of his knowledge. “I wanted the reviews and investigations carried out, so that we could tell the parents what had happened to their children,” he said.

He added: “These are truly terrible crimes and I am deeply sorry that this happened to them. I believe there should be an inquiry that looks at all events leading up to this trial and I will help it in whatever way I can.”

Alison Kelly, the former chief nurse who is now interim director of nursing for Salford, within the Northern Care Alliance Trust, is reported to have said: “These are truly terrible crimes and I am deeply sorry that this happened to them.”

She said lessons needed to be learned and she would co-operate with any investigation.

Karen Rees, now Moore, could not be reached for comment but is understood to dispute the account given by Dr Brearey.

[ Via: https://archive.md/a63Iq ]

==

This is horrific, and the fact we live in a culture where she could fabricate and successfully exploit a fake claim of victimization, where despite the justified suspicion around her, she was shielded and protected, at the cost of multiple infant lives is incredible.

#Lucy Letby#victimhood culture#serial killer#baby murderer#Countess of Chester Hospital#victimhood#baby killer#religion is a mental illness

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hospital Reputations v Patients Safety

Nurse Lucy Letby has been found guilty of murdering babies, but the hospital management are also to blame. Doctors made their fears known to the Countess of Chester Hospital but the hospital management’s first concern was for the hospital’s reputation and not for the health and lives of their patients. The management even forced the doctors expressing their concerns about nurse Lucy Letby to…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucy Letby Appeals Conviction Amid Evidence Scrutiny

Lucy Letby Appeals Conviction Amid Renewed Scrutiny Lucy Letby, a former neonatal nurse, was convicted of the murder of seven infants and the attempted murder of another seven, and she is set to seek an appeal regarding one of her convictions in a London court this Thursday. The appeal comes at a time of increasing examination of the evidence presented during her trial, with a growing number of…

#appeal#attempted murder#Baby K#conviction#Countess of Chester Hospital#Criminal Cases Review Commission#Lucy Letby#miscarriages of justice#murder#neonatal nurse#UK justice system

0 notes

Text

Grim plan for Lucy Letby's life in Prison - Lucy Letby, who lived near Chester, worked as a neonatal nurse at the Countess of Chester Hospital.

Grim plan for Lucy Letby’s life in Prison – Lucy Letby, who lived near Chester, worked as a neonatal nurse at the Countess of Chester Hospital.

View On WordPress

#Chester#Chester Hospital#Countess#Grim#Grim plan for Lucy Letby&039;s life in Prison#Lucy Letby#Neonatal#Neonatal Nurse#Nurse#Prison

0 notes

Text

How New Zealand whistleblowers and law advocates are watching " retaliatory NHS trusts" in the UK who stamp on doctors

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

HAPPY 42ND BIRTHDAY TO HRH THE PRINCE OF WALES, WILLIAM ARTHUR PHILIP LOUIS ♡

On 21 June 1982, Prince William was born to Diana and Charles, then known as Prince and Princess of Wales in St Mary's Hospital, London, at at 21:03 BST. He was born during the reign of his paternal grandmother Elizabeth II and was the first child born to a Prince and Princess of Wales since Prince John's birth in July 1905.

The little prince's name was announced on 28 June as William Arthur Philip Louis. Wills was christened in the Music Room of Buckingham Palace by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, on 4 August.

William studied at Jane Mynors' nursery school and Wetherby School in London before joining Ludgrove. He was subsequently admitted to Eton College, studying geography, biology, and history at the A-level.

The Prince undertook a gap year taking part in British Army training exercises in Belize, working on English dairy farms, and as part of the Raleigh International programme in southern Chile, William worked for ten weeks on local construction projects and taught English.

In 2001, William enrolled at the University of St Andrews, initially to study Art History but then changed his field of study to Geography with the support of the love of his life Catherine Elizabeth Middleton who he met while at school.

Will and Cat fell in love during their time at uni, and married at Westminster Abbey on 29 April 2011. The couple have three adorable cupcakes Prince George (b.2013), Princess Charlotte (b.2015) and Prince Louis (b.2018). The family of five divide time between their official residence, Kensington Palace and their two private residences - Amner Hall & Adelaide Cottage.

After university, William trained at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. In 2008, he graduated from the Royal Air Force College Cranwell and joined the RAF Search and Rescue Force in early 2009. He transferred to RAF Valley, Anglesey, to receive training on the Sea King search and rescue helicopter, which made him the first member of the British royal family since Henry VII to live in Wales.

During his active career as a Search and Rescue Pilot, William conducted 156 search and rescue operations, which resulted in 149 people being rescued. He then served as a full-time pilot with the East Anglian Air Ambulance starting in July 2015, donating his full salary to the EAAA charity.

Working with all branches of the military, he holds the ranks of Lieutenant Colonel in the Army, Commander in the Navy and Wing Commander in the Air-Force

Upon their wedding, WillCat became HRH The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, The Earl and Countess of Strathearn and Baron and Lady Carrickfergus. He became the heir apparent on 8 September 2022, receiving the titles of the Duke of Cornwall & The Duke of Rothesay. William & Catherine were made The Prince and Princess of Wales by Kimg Charles on 9 September 2022. Additionally, William also became the Prince & High Steward of Scotland, Earl of Chester, Earl of Carrick, Lord of the Isles, and Baron Renfrew.

As well as undertaking royal duties in support of The King, both in the UK and overseas, The Prince devotes his time supporting a number of charitable causes and organisations with some of his key areas of interest being Mental health, Conservation, Homelessness, Sports and Emergency Workers.

He has undertaken several overseas trips representing the monarch, covering a wide array of countries like Australia, Canada, Namibia, Malaysia, South Africa, Tanzania, Pakistan Italy, Jordan, Kuwait, France, India, The Bahamas, Belize, Afghanistan etc ; He is also is also a founder of various initiatives like United For Wildlife, Heads Together, Earthshot and Homewards.

#happy birthday william ❤️#william's 42nd birthday#prince of wales#the prince of wales#prince william#william wales.#william prince of wales#british royal family#british royals#royals#royalty#brf#royal#british royalty#catherine middleton#kate middleton#duchess of cambridge#2024 wales birthdays#prince george#princess charlotte#prince louis#royaltyedit#royalty gifs#royalty edit#royaltygifs#my gifs#21062024

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

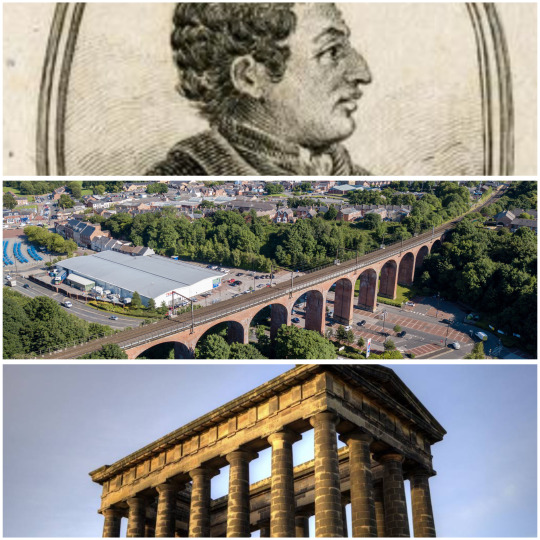

Baronet -> Coal-miners -> Royalty

“A time may yet come, perchance, when a descendant of one of these simple artizans may arise, not unworthy of the Conyers' ancient renown; and it will be a gratifying discovery to some future genealogist, when he succeeds in tracing in the quarterings of such a descendant the unsullied bearing of Conyers of Durham." Sir Bernard Burke, 1861.

In 1861 the genealogist and publisher of Burke’s Peerage Sir Bernard Burke, in his book "Vicissitudes of Families", dedicated a chapter to the “The Fall of Conyers" which concludes with the following: "Magni stat nominis umbra! The poor Baronet left three daughters, married in very humble life: Jane, to William Hardy; Elizabeth, to Joseph Hutchinson; and Dorothy, to Joseph Barker, all working men in the little town of Chester-le-Street. A time may yet come, perchance, when a descendant of one of these simple artizans may arise, not unworthy of the Conyers' ancient renown; and it will be a gratifying discovery to some future genealogist, when he succeeds in tracing in the quarterings of such a descendant the unsullied bearing of Conyers of Durham."

Sir Thomas Conyers, was the 9th and last Baronet Conyers of Horden Hall. While a gentleman at birth, he was reduced to poverty and resided at the Durham Workhouse. His pride made him reject financial aid from his distant relatives, among them his second cousin Mary Eleanor Bowes, Countess of Strathmore, whose funeral he attended at Westminster Abbey in 1800. At the time she was one of the wealthiest women in England and is an ancestor of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyons, the late Queen Mother.

His later years were made somewhat more comfortable at the aid of another distant cousin, George Lumley-Saunderson, the 5th Earl of Scarborough who provided him with a small house. Sir Thomas died a pauper on 15 April 1810. His surviving children, three daughters had married working men in the little town of Chester-le-Street, County Durham. As if from a Thomas Hardy novel, his daughter Jane married a man named William Hardy.

For five generations Sir Thomas Conyers descendants would work as labourers, and often in coal mines once owned by distant ancestors and now owned by the Bowes-Lyon family. By the sixth generation his descendant Robert Harrison, a carpenter left his family still working in the coal mines to seek opportunities in London. There he married and had a daughter, Dorothy who married a builder named Ronald Goldsmith.

The early years of Dorothy and Ronald’s marriage and their children's upbringing were spent in a comfortable council house, providing the security needed to buy their own home. Their daughter, Carole, became a flight attendant and married a young flight dispatcher, Michael. They settled in Berkshire and spent a few years in Jordan, working for British Airways, before returning to Berkshire, where Carole started her own business at her kitchen table.

Almost ten generations and 201 years after Sir Thomas Conyers died a pauper, his descendant Catherine Middleton married Prince William of Wales on 29 April 2011.

Family Line

Sir Thomas Conyers 9th Bt. Conyers of Horden (drawing) m. Isabel Lambton

Jane Conyers of Chester Le Street, County Durham m. William Hardy of

Jane Hardy of Biddick, County Durham m. James Liddell

Anthony Liddell of Little Lumley, County Durham m. Martha Stephenson

Jane Liddell (photo) m. John Harrison

John Harrison (photo) m. Jane Hill

Robert Harrison (photo) m. Elizabeth Temple

Dorothy Harrison (photo) m. Ronald Goldsmith

Carole Goldsmith m. Michael Middleton

Catherine Middleton m. Prince William of Wales

#ktd#brf#british royal family#kate middleton#princess of wales#prince william#Carole Middleton#The north#england#northern england#durham#coal#mining#elizabeth bowes lyon#the queen mother#queen mother

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

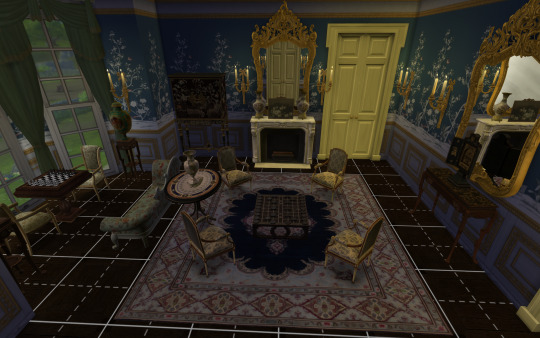

Windenburg Royal Brides

Queen Marina (Formerly Princess Marina of Brindleton)

Queen Margaret (Formerly Princess Margaret of Antwerp)

Princess Anne, Princess Royal, Duchess of Chester

Princess Alice, Countess of Arbor

Queen Cecelia (Formerly Lady Cecelia Warren)

Princess Lorelei, Princess Royal, Countess of Thurlby

Queen Caroline (Formerly Princess Caroline of Brindleton)

Princess Adelaide, Empress of Alderaan (@threesimsroyal)

Princess Victoria, Duchess of Stonesby

Mary III, Queen of Windenburg

#statfordlegacy#sims4#legacy#royalty#royallegacy#ts4 legacy#sims#sims 4 royals#ts4#royal wedding#the sims 4 wedding#ts4 royals#extras

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunderland's Royal Jewel Vault (32/∞) ♛

↬ The Trethewey Wreath Tiara

One of the few wreath tiaras in the royal vault, the Trethewey tiara remains one of the most notable tiaras of Queen Katherine (née Lady Katherine Rothman), despite not being seen since the 1950s. The tiara is named after Katherine’s family, holders of the once powerful and influential Trethewey Earldom. The daughter of the Earl and Countess of Trethewey, Katherine’s charmed life was cut short during the Great Depression. In 1931, Katherine’s family moved from their sprawling country estate into a modest three-storey townhouse. The family retained only a cook and the Countess’s lady’s maid, and for the first time in her life Katherine had to do her own chores. A new home also meant a new school, as Katherine’s parents could no longer afford a private tutor. Friends and relatives noted that the once boisterous girl became withdrawn and prone to tears almost overnight. Further tragedy struck when Katherine’s only sibling, big brother Clarence, was killed during World War Two. At the time, Sunderland was constrained by a non-aggression act it passed a year earlier, but many Sunderlandians still volunteered to fight under the Allied forces. Clarence, called Red Clarence for his socialist views, was adamantly against Sunderland’s non-interventionist stance. Despite the pleas of his parents and sister, Clarence volunteered with the United Kingdom’s Territorial Army. Following Clarence’s death, Katherine recalled becoming mad, downright neurotic. By 1941, Katherine’s behaviour reached a fever pitch, I thought I should be institutionalized and that’s what I wanted. To be put away, as they say. So I acted out more and more. My parents saw through me, I think. During this time, Katherine’s favourite exploit came in the form of Prince James, the second son of King George II and an old childhood friend. The two had begun a tryst years earlier, but after Katherine’s brother died James asked Katherine to marry him. I laughed because I thought he was joking, but he didn’t even smile. Said that he’d seen how much I’d suffered and that he wanted to save me. When Katherine rejected James he only became more and more insistent.

He went to Daddy. And then Mommy. Both insisted that it was my choice. He showed up at all sorts of crazy hours. Wouldn’t leave me alone. Every time he saw me, he would throw himself at my feet and cry: “Marry me, Kitty! I’ll make you smile again.” It devastated me; royal life was a terrifying prospect. At the time I’d wanted to fold into myself, become invisible. Now James wanted to put me in a bell jar.

In 1942, Prince James enlisted the help of his mother Queen Anne. Anne had some reservations about Katherine’s suitability for royal life, but she was also firm in her belief that each of her children should marry for love. That spring, Katherine and her mother were called to Chester Palace. Her Majesty sat me down and told me Jim would never love another girl as much as he loved me. Katherine agreed to marry James that summer. I told him to ask that same ol’ question, because I’ll respond the way he wants this time. Upon Katherine’s marriage, the fortune of her parents increased greatly. Their daughter was now the Duchess of Woodbine, the third lady of the land behind the Queen and the Princess of Danforth. Ahead of the wedding, the Earl and Countess gifted their daughter a diamond wreath tiara, featuring diamond laurel leaves between sprays of cabochon rubies. It came with a note about how proud they were and how much they loved me. I cried myself to sleep that night. It was as if something fundamental had shifted, all at once it came to me that I was no longer theirs. In the early years of her marriage, Katherine wore the tiara for her first official portraits as the Duchess of Woodbine. Images of the duchess in this tiara were displayed on stamps, posters, and even cigarette packages. Katherine disliked the publicity, but it was just a taste of what was yet to come in the years ahead. In late 1943, Katherine’s brother-in-law George, the Prince of Danforth, was assassinated. In 1944, Prince James was formally declared heir apparent. One year later, Katherine was pregnant with her first child. By 1956, King James II and Queen Katherine sought romantic comfort from other people. The Trethewey wreath tiara hasn’t been worn since.

#warwick.jewels#✨#this is the best one . . . in terms of the writing . . . i really did that#it might just be better than the westminster aquamarine post#ts4#ts4 story#ts4 royal#ts4 storytelling#ts4 edit#ts4 royal legacy#ts4 legacy#ts4 royalty#ts4 monarchy#ts4 screenshots

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Folklore Fact - Wyverns

Another month, another folklore fact! Wyverns handily won the poll over on my Patreon this month (be sure to take a look if you'd like to vote in the next one or even suggest all new subjects!)...

(nearly all modern dragon designs seen in visual media, especially film and television but now quite often also video games, count as the traditional British heraldic classification of wyverns, really; see my post here for a discussion of that, although I could expand that post today and discuss things like Monster Hunter, etc, which I didn't really know much about at the time, and even further discuss some of the subjects already therein... Anyway, maybe I'll revise that sometime in the future and improve it)

Wyverns are often described as a dragon with two hind legs, two wings, no forelegs, and a barbed tail. There are varieties, of course; some say the wyvern has the head of a dragon, the legs of an eagle, and a barbed "serpent tail" or simply a long tail with no barb. There are many varieties. Traditionally, at least if you ask English heraldry, the requirement to be a wyvern is that it has no forelegs - unlike the dragon, which has four legs in addition to wings. However, this is a technicality that was obviously not always applied elsewhere, including the European mainland. More on that shortly.

The word "wyvern" is not in itself all that old; it originated around 1600, derived from "wyver" from 1300, so the term is not ancient. Like dragon, it essentially means "snake," though in this case it is derived from "viper." As mentioned, "dragon" itself is derived from "drakon" meaning serpent (and/or "giant seafish") [source: again, one of my favorite sites].

Stamp of Clifford, Anne, Countess of Dorset (1590 - 1676) [source], depicting a wyvern.

There was apparently some discussion around the rise of the heraldic wyvern in England, Scotland, and Ireland regarding what exactly classified a wyvern as opposed to a dragon. In 1610, the writings of John Guillim described a wyvern (then "wiverne") thus: "partake[ing] of a Fowle in the Wings and Legs … and doth resemble a Serpent in the Taile," and in 1682, John Gibbon agrees that a wyvern specifically has "but" two legs. It is noteworthy that both men in question were officers of heraldry, and these remarks are quotations from book on coats of arms, and thus it was specifically heraldry they discussed.

"Wyverns" as per monsters of myth and folklore were, for most intents and purposes of their time period, referred to as "dragons" and not thought of as their own sort of beast rather than just a variation of dragon for heraldry specifically or even exclusively. Were there any legends about something called a "wyvern?" I haven't found any in all my extensive research on dragon legends, and most all academic sources agree that a "wyvern" is a heraldic creature rather than something you'd find in a bestiary and/or folktale.

As mentioned, depictions of what we today might think of as "wyverns" were not always called "wyverns," of course, especially throughout a lot of Europe (as opposed to Great Britain). Here we see a depiction of what we would now think of as a "wyvern" referred to as a dragon ("drago"), from a work dated 1691, so during the same time period that heraldic wyverns were already being classified as such.

There are also bestiaries and other things that depict two-legged dragons as "dragons" rather than ever referring to them as "wyverns" specifically, and the creatures depicted therein were in fact meant to simply be "dragons." Older eras lacked the picky categorization that exists more recently, particularly myth and folklore. This is why there are no "categories" of werewolf legends, either, for instance, or different "types" of werewolves - except as put on them retroactively by modern scholars.

A "wyvern" from 1380 in the Chester Cathedral in England; given its hooves and head of a man, it isn't exactly a "standard" wyvern.

So, again, the idea of the wyvern as a unique creature as opposed to another sort of dragon likely stemmed from heraldry - which in itself has a lot of unique creatures and specifics, such as the enfield and bagwyn - and specifically heraldry from Great Britain and Ireland, which meant that such defined notions of a wyvern came about in later centuries. There are certainly depictions of dragons and dragon-like creatures without forelegs from other centuries, such as the 1300s, but these are not explicitly as sourced "wyverns" during their own time period. Rather, they are described as such now by people retroactively applying the wyvern concept onto them. Such a concept became common starting around the 1600s, as mentioned earlier with the heraldic writings of Guillim and Gibbon. There are plenty of examples of "dragons" with two legs and, sometimes, even "wyverns" with four legs floating around out there.

But since modernity also thrives on technicality, categories, and specifics, things like D&D for a while there often referred to a "wyvern" as a two-legged dragon (which I personally find preferable, despite my usual aversion to categorization of mythological things) - at least, until a lot of media is today started changing that ever since Reign of Fire in 2003. These days, outside of a handful of fantasy things, like D&D with their older established rules and a few other fantasy games that originated before this sweeping design change occurred, dragons very often have two legs instead of four. I could say a lot more about that, but I won't get into it...

And that covers a general overview on wyverns! Until next time. For June, expect to see a brand new werewolf fact.

( If you like my blog, be sure to follow me here and sign up for my free newsletter for more folklore and fiction, including books! And plenty of werewolf things.

Free Newsletter - maverickwerewolf.com (info + book shop) — Patreon — Wulfgard — Werewolf Fact Masterlist — Twitter — Vampire Fact Masterlist — Amazon Author page )

#folklore#mythology#wyvern#wyverns#dragon#dragons#fantasy creature#folklore fact#folklore thursday#myth#medieval#medieval folklore#heraldry#history#fantasy

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

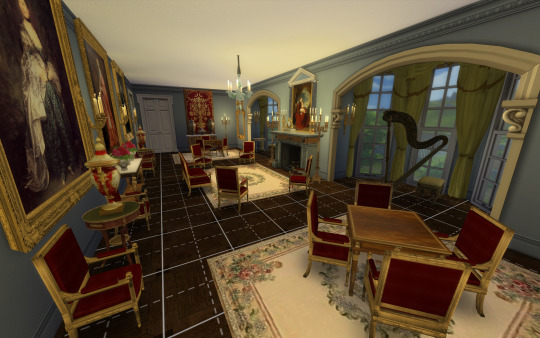

Grimsthorpe Castle

Hi guys!!

I'm sharing another grand english state!

House History: The building was originally a small castle on the crest of a ridge on the road inland from the Lincolnshire fen edge towards the Great North Road. It is said to have been begun by Gilbert de Gant, Earl of Lincoln in the early 13th century. However, he was the first and last in this creation of the Earldom of Lincoln and he died in 1156. Gilbert's heyday was the peak time of castle building in England, during the Anarchy. It is quite possible that the castle was built around 1140. However, the tower at the south-east corner of the present building is usually said to have been part of the original castle and it is known as King John's Tower. The naming of King John's tower seems to have led to a misattribution of the castle's origin to his time.

Gilbert de Gant spent much of his life in the power of the Earl of Chester and Grimsthorpe is likely to have fallen into his hands in 1156 when Gilbert died, though the title 'Earl of Lincoln' reverted to the crown. In the next creation of the earldom, in 1217, it was Ranulph de Blondeville, 4th Earl of Chester (1172–1232) who was ennobled with it. It seems that the title, if not the property was in the hands of King John during his reign; hence perhaps, the name of the tower.

During the last years of the Plantagenet kings of England, it was in the hands of Lord Lovell. He was a prominent supporter of Richard III. After Henry VII came to the throne, Lovell supported a rebellion to restore the earlier royal dynasty. The rebellion failed and Lovell's property was taken confiscated and given to a supporter of the Tudor Dynasty.[2]

The Tudor period

This grant by Henry VIII, Henry Tudor's son, to the 11th Baron Willoughby de Eresby was made in 1516, together with the hand in marriage of Maria de Salinas, a Spanish lady-in-waiting to Queen Catherine of Aragon. Their daughter Katherine inherited the title and estate on the death of her father in 1526, when she was aged just seven. In 1533, she became the fourth wife of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, a close ally of Henry VIII. In 1539, Henry VIII granted Charles Suffolk the lands of the nearby suppressed Vaudey Abbey, founded in 1147, and he used its stone as building material for his new house. Suffolk set about extending and rebuilding his wife's house, and in only eighteen months it was ready for a visit in 1541 by King Henry, on his way to York to meet his nephew, James V of Scotland. In 1551, James's widow Mary of Guise also stayed at Grimsthorpe. The house stands on glacial till and it seems that the additions were hastily constructed. Substantial repairs were required later owing to the poor state of the foundations, but much of this Tudor house can still be seen today.

During Mary's reign the castle's owners, Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk (née Willoughby) and her second husband, Richard Bertie, were forced to leave it owing to their Anglican views. On Elizabeth's succeeding to the throne, they returned with their daughter, Susan, later Countess of Kent and their new son Peregrine, later the 13th Baron. He became a soldier and spent much of his time away from Grimsthorpe.

The Vanbrugh building

By 1707, when Grimsthorpe was illustrated in Britannia Illustrata, the 15th Baron Willoughby de Eresby and 3rd Earl Lindsey had rebuilt the north front of Grimsthorpe in the classical style. However, in 1715, Robert Bertie, the 16th Baron Willoughby de Eresby, employed Sir John Vanbrugh to design a Baroque front to the house to celebrate his ennoblement as the first Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven. It is Vanbrugh's last masterpiece. He also prepared designs for the reconstruction of the other three ranges of the house, but they were not carried out. His proposed elevation for the south front was in the Palladian style, which was just coming into fashion, and is quite different from all of his built designs.

The North Front of Grimsthorpe as rebuilt by Vanbrugh, drawn in 1819. Vanbrugh's Stone Hall occupies the space between the columns on both floors.

Inside, the Vanbrugh hall is monumental with stone arcades all around at two levels. Arcaded screens at each end of the hall separate the hall from staircases, much like those at Audley End House and Castle Howard. The staircase is behind the hall screen and leads to the staterooms on the first floor. The State Dining Room occupies Vanbrugh's north-east tower, with its painted ceiling lit by a Venetian window. It contains the throne used by George IV at his Coronation Banquet, and a Regency giltwood throne and footstool used by Queen Victoria in the old House of Lords. There is also a walnut and parcel gilt chair and footstool made for the use of George III at Westminster. The King James and State Drawing Rooms have been redecorated over the centuries, and contain portraits by Reynolds and Van Dyck, European furniture, and yellow Soho Tapestries woven by Joshua Morris around 1730. The South Corridor contains thrones used by Prince Albert and Edward VII, as well as the desk on which Queen Victoria signed her coronation oath. A series of rooms follows in the Tudor east range, with recessed oriel windows and ornate ceilings. The Chinese drawing room has a splendidly rich ceiling and an 18th-century fan-vaulted oriel window. The walls are hung with Chinese wallpaper depicting birds amidst bamboo. The chapel is magnificent with superb 17th-century plasterwork.

More history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grimsthorpe_Castle

This house fits a 64x64 lot and features several impressive rooms, more than 29 bedrooms, a servants hall and several state rooms!

I only decored some of the main rooms, for you to have a glimpse of the distribution. The rest is up to you, as I have stated that I do not like interiors :P

Be warned: I did not have the floor plan for the tudor rooms, thus, the distribution is based on my own decision and can not fit the real house :P.

You will need the usual CC I use: all of Felixandre, The Jim, SYB, Anachrosims, Regal Sims, TGS, The Golden Sanctuary, Dndr recolors, etc.

Please enjoy, comment if you like it and share pictures with me if you use my creations!

DOWNLOAD (Early acces: June 30) https://www.patreon.com/posts/grimsthorpe-101891128

#sims 4 architecture#sims 4 build#sims4#sims4play#sims 4 screenshots#sims 4 historical#sims4building#sims4palace#sims 4 royalty#ts4 download#ts4#ts4 gameplay#ts4 simblr#ts4cc#ts4 legacy#sims 4 gameplay#sims 4 legacy#sims 4 cc#thesims4#sims 4#the sims 4#sims 4 aesthetic#ts4 cc#english manor

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Working Royals of the British Royal Family: A Series

Full name: Catherine Elizabeth (née Middleton) Title: Her Royal Highness The Princess of Wales (Duchess of Cambridge, Countess of Strathearn, Lady Carrickfergus, Duchess of Cornwall, Duchess of Rothesay, Countess of Carrick, Lady Renfrew, Countess of Chester) Birth: 09 January 1982 at Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading Current Age: 41

Catherine is the eldest of three children and was born to Carole and Michael Middleton. She spent her early life in Jordan, where she attended a multicultural nursery, before returning to Berkshire with her sister Pippa and baby brother James. Catherine studied History of Art at the University of St Andrews, where she met the then-Prince William of Wales, whom she later married on April 29th 2011. Catherine has three children - Prince George, Princess Charlotte and Prince Louis. She is passionate about children, mental health and the early years.

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucy Letby: Chester Hospital 'deeply saddened' and 'appalled' by nurse's crimes | News UK Video News | Sky News

The crimes of this nurse Lucy Letby are extremely appalling, but so are the actions of the hospital management of the Countess of Chester hospital for they appear to uphold their reputation rather than the health of their patients. Some doctors were so concerned about the events occurring so went to the hospital management to express their concerns about Nurse Lucy Letby. But the hospital stated…

View On WordPress

#appauling#Countess of Chester hospital reputation#Dr Nigel Scawn medical director at the Countess of Chester Hospital#nurse Lucy Letby#reputation

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A British Nurse Was Found Guilty of Killing Seven Babies. Did She Do It?

Rachel Aviv, The New Yorker

“Last August, Lucy Letby, a thirty-three-year-old British nurse, was convicted of killing seven newborn babies and attempting to kill six others. Her murder trial, one of the longest in English history, lasted more than ten months and captivated the United Kingdom. The Guardian, which published more than a hundred stories about the case, called her “one of the most notorious female murderers of the last century.” The collective acceptance of her guilt was absolute. “She has thrown open the door to Hell,” the Daily Mail wrote, “and the stench of evil overwhelms us all.”

…The public conversation rushed forward without much curiosity about an incongruous aspect of the story: Letby appeared to have been a psychologically healthy and happy person. She had many close friends. Her nursing colleagues spoke highly of her care and dedication. A detective with the Cheshire police, which led the investigation, said, “This is completely unprecedented in that there doesn’t seem to be anything to say” about why Letby would kill babies. “There isn’t really anything we have found in her background that’s anything other than normal.”

The judge in her case, James Goss, acknowledged that Letby appeared to have been a “very conscientious, hard working, knowledgeable, confident and professional nurse.” But he also said that she had embarked on a “calculated and cynical campaign of child murder,” and he sentenced her to life, making her only the fourth woman in U.K. history condemned to die in prison. Although her punishment can’t be increased, she will face a second trial, this June, on an attempted-murder charge for which the jury could not reach a verdict.

Letby had worked on a struggling neonatal unit at the Countess of Chester Hospital, run by the National Health Service, in the West of England, near Wales. The case centered on a cluster of seven deaths, between June, 2015, and June, 2016. All but one of the babies were premature; three of them weighed less than three pounds. No one ever saw Letby harming a child, and the coroner did not find foul play in any of the deaths. (Since her arrest, Letby has not made any public comments, and a court order has prohibited most reporting on her case. To describe her experiences, I drew from more than seven thousand pages of court transcripts, which included police interviews and text messages, and from internal hospital records that were leaked to me.)

The case against her gathered force on the basis of a single diagram shared by the police, which circulated widely in the media. On the vertical axis were twenty-four “suspicious events,” which included the deaths of the seven newborns and seventeen other instances of babies suddenly deteriorating. On the horizontal axis were the names of thirty-eight nurses who had worked on the unit during that time, with X’s next to each suspicious event that occurred when they were on shift. Letby was the only nurse with an uninterrupted line of X’s below her name. She was the “one common denominator,” the “constant malevolent presence when things took a turn for the worse,” one of the prosecutors, Nick Johnson, told the jury in his opening statement. “If you look at the table overall the picture is, we suggest, self-evidently obvious. It’s a process of elimination.”

But the chart didn’t account for any other factors influencing the mortality rate on the unit. Letby had become the country’s most reviled woman—“the unexpected face of evil,” as the British magazine Prospect put it—largely because of that unbroken line. It gave an impression of mathematical clarity and coherence, distracting from another possibility: that there had never been any crimes at all.

Since Letby was a teen-ager, she had wanted to be a nurse. “She’d had a difficult birth herself, and she was very grateful for being alive to the nurses that would have helped save her life,” her friend Dawn Howe told the BBC. An only child, Letby grew up in Hereford, a city north of Bristol. In high school, she had a group of close friends who called themselves the “miss-match family”: they were dorky and liked to play games such as Cranium and Twister. Howe described Letby as the “most kind, gentle, soft friend.” Another friend said that she was “joyful and peaceful.”

Letby was the first person in her family to go to college. She got a nursing degree from the University of Chester, in 2011, and began working on the neonatal unit at the Countess of Chester Hospital, where she had trained as a student nurse. Chester was a hundred miles from Hereford, and her parents didn’t like her being so far away. “I feel very guilty for staying here sometimes but it’s what I want,” she told a colleague in a text message. She described the nursing team at the Countess as “like a little family.” She spent her free time with other nurses from the unit, often appearing in pictures on Facebook in flowery outfits and lip gloss, with sparkling wine in her hand and a guileless smile. She had straight blond hair, the color washing out as she aged, and she was unassumingly pretty.

The N.H.S. has a totemic status in the British psyche—it’s the “closest thing the English have to a religion,” as one politician has put it. One of the last remnants of the postwar social contract, it inspires loyalty and awe even as it has increasingly broken down, partly as a result of years of underfunding. In 2015, the infant-mortality rate in England and Wales rose for the first time in a century. A survey found that two-thirds of the country’s neonatal units did not have enough medical and nursing staff. That year, the Countess treated more babies than it had in previous years, and they had, on average, lower birth weights and more complex medical needs.

Letby, who lived in staff housing on the hospital grounds, was twenty-five years old and had just finished a six-month course to become qualified in neonatal intensive care. She was one of only two junior nurses on the unit with that training. “We had massive staffing issues, where people were coming in and doing extra shifts,” a senior nurse on the unit said. “It was mainly Lucy that did a lot.” She was young, single, and saving to buy a house. That year, when a friend suggested that she take some time off, Letby texted her, “Work is always my priority.”

In June, 2015, three babies died at the Countess. First, a woman with antiphospholipid syndrome, a rare disorder that can cause blood clotting, was admitted to the hospital. She was thirty-one weeks pregnant with twins, and had planned to give birth in London, so that a specialist could monitor her and the babies, but her blood pressure had quickly risen, and she had to have an emergency C-section at the Countess. The next day, Letby was asked to cover a colleague’s night shift. She was assigned one of the twins, a boy, who has been called Child A. (The court order forbade identifying the children, their parents, and some nurses and doctors.)

A nursing note from the day shift said that the baby had had “no fluids running for a couple of hours,” because his umbilical catheter, a tube that delivers fluids through the abdomen, had twice been placed in the wrong position, and “doctors busy.” A junior doctor eventually put in a longline, a thin tube threaded through a vein, and Letby and another nurse gave the child fluid. Twenty minutes later, Letby and a third nurse, a few feet away, noticed that his oxygen levels were dropping and that his skin was mottled. The doctor who had inserted the longline worried that he had placed it too close to the child’s heart, and he immediately took it out. But, less than ninety minutes after Letby started her shift, the baby was dead. “It was awful,” she wrote to a colleague afterward. “He died very suddenly and unexpectedly just after handover.”

A pathologist observed that the baby had “crossed pulmonary arteries,” a structural anomaly, and there was also a “strong temporal relationship” between the insertion of the longline and the collapse. The pathologist described the cause of death as “unascertained.”

Letby was on duty again the night after Child A’s death. At around midnight, she helped the nurse who had been assigned to the surviving twin, a girl, set up her I.V. bag. About twenty-five minutes later, the baby’s skin became purple and blotchy, and her heart rate dropped. She was resuscitated and recovered. Brearey, the unit’s leader, told me that at the time he wondered if the twins had been more vulnerable because of the mother’s disorder; antibodies for it can pass through the placenta.

The next day, a mother who had been diagnosed as having a dangerous placenta condition gave birth to a baby boy who weighed one pound, twelve ounces, which was on the edge of the weight threshold that the unit was certified to treat. Within four days, the baby developed acute pneumonia. Letby was not working in the intensive-care nursery, where the baby was treated, but after the child’s oxygen alarm went off she came into the room to help. Yet the staff on the unit couldn’t save the baby. A pathologist determined that he had died of natural causes.

Several days later, a woman came to the hospital after her water broke. She was sent home and told to wait. More than twenty-four hours later, she noticed that the baby was making fewer movements inside her. “I was concerned for infection because I hadn’t been given any antibiotics,” she said later. She returned to the hospital, but she still wasn’t given antibiotics. She felt “forgotten by the staff, really,” she said. Sixty hours after her water broke, she had a C-section.

The baby, a girl who was dusky and limp when she was born, should have been treated with antibiotics immediately, doctors later acknowledged, but nearly four hours passed before she was given the medication. The next night, the baby’s oxygen alarm went off. “Called Staff Nurse Letby to help,” a nurse wrote. The baby continued to deteriorate throughout the night and could not be revived. A pathologist found pneumonia in the baby’s lungs and wrote that the infection was likely present at birth.

The senior pediatricians met to review the deaths, to see if there were any patterns or mistakes. “One of the problems with neonatal deaths is that preterm babies can die suddenly and you don’t always get the answer immediately,” Brearey told me. A study of about a thousand infant deaths in southeast London, published in The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, found that the cause of mortality was unexplained for about half the newborns who had died unexpectedly, even after an autopsy. Brearey observed that Letby was involved in each of the deaths at the Countess, but “it didn’t sound to me like the odds were that extreme of having a nurse present for three of those cases,” he said. “Nobody had any concerns about her practice.”

…At the end of January, 2016, the senior pediatricians met with a neonatologist at a nearby hospital, to review the ward’s mortality data. In 2013 and 2014, the unit had had two and three deaths, respectively. In 2015, there had been eight. At the meeting, “there were a few learning points, nothing particularly exciting,” Brearey recalled. Near the end, he asked the neonatologist what he thought about the fact that Letby was present for each death. “I can’t remember him suggesting anything, really,” Brearey said.

But Jayaram and Brearey were increasingly troubled by the link. “It was like staring at a Magic Eye picture,” Jayaram told me. “At first, it’s just a load of dots,” and the dots are incoherent. “But you stare at them, and all of a sudden the picture appears. And then, once you can see that picture, you see it every time you look, and you think, How the hell did I miss that?” By the spring of 2016, he said, he could not “unsee it.”

Many of the deaths had occurred at night, so Powell, the unit manager, shifted Letby primarily to day shifts, because there would be “more people about to be able to support her,” she said.

A week later, a mother gave birth to identical triplet boys, born at thirty-three weeks. When she was pregnant, the mother said, she had been told that each baby would have his own nurse, but Letby, who had just returned from a short trip to Spain with friends, was assigned two of the triplets, as well as a third baby from a different family. She was also training a student nurse who was “glued to me,” she complained to Taylor. Seven hours into Letby’s shift, one of the triplet’s oxygen levels dropped precipitously, and he developed a rash on his chest. Letby called for help. After two rounds of CPR, the baby died.

The next day, Letby was the designated nurse for the two surviving triplets. The abdomen of one of them appeared distended, a possible sign of infection. When she told Taylor, he messaged her, “I wonder if they’ve all been exposed to a bug that benzylpenicillin and gentamicin didn’t account for? Are you okay?”

“I’m okay, just don’t want to be here really,” Letby replied. The student nurse was still with her, and Letby told Taylor, “I don’t feel I’m in the frame of mind to support her properly.”

A doctor came to check on the triplet with the distended abdomen, and, while he was in the room, the child’s oxygen levels dropped. The baby was put on a ventilator, and the hospital asked for a transport team to take him to Liverpool Women’s Hospital. As they were waiting, it was discovered that the baby had a collapsed lung, possibly a result of pressure from the ventilation, which was set unusually high. “There was an increasing sense of anxiety on the unit,” Letby said later. “Nobody seemed to know what was happening and very much just wanted the transport team to come and offer their expertise.”

The triplets’ mother said that she was alarmed when she saw a doctor sitting at a computer “Googling how to do what looked like a relatively simple medical procedure: inserting a line into the chest.” She was also upset that one of the doctors who was resuscitating her son was “coughing and spluttering into her hands” without washing them. Shortly after the transport team arrived, the second triplet died. His mother recalled that Letby was “in pieces and almost as upset as we were.”

…Brearey, Jayaram, and a few other pediatric consultants met to discuss the unexpected deaths. “We were trying to rack our brains,” Brearey said. A postmortem X-ray of one of the babies had shown gas near the skull, a finding that the pathologist did not consider particularly meaningful, since gas is often present after death. Jayaram remembered learning in medical school about air embolisms—a rare, potentially catastrophic complication that can occur when air bubbles enter a person’s veins or arteries, blocking blood supply. That night, he searched for literature about the phenomenon.

He did not see any cases of murder by air embolism, but he forwarded his colleagues a four-page paper, from 1989, in the Archives of Disease in Childhood, about accidental air embolism. The authors of the paper could find only fifty-three cases in the world. All but four of the infants had died immediately. In five cases, their skin became discolored. “I remember the physical chill that went down my spine,” Jayaram said. “It fitted with what we were seeing.”

…After Letby returned from vacation, she was called in for a meeting. The deputy director of nursing told her that she was the common element in the cluster of deaths, and that her clinical competence would need to be reassessed. “She was distraught,” Powell, the unit manager, who was also at the meeting, said. “We were both quite upset.” They walked straight from the meeting to human resources. “We were trying to get Lucy back on the unit, so we had to try and prove that the competency issue wasn’t the problem,” Powell said.

But Letby never returned to clinical duties. She was eventually moved to an administrative role in the hospital’s risk-and-safety office. Jayaram described the office as “almost an island of lost souls. If there was a nurse who wasn’t very good clinically, or a manager who they wanted to get out of the way, they’d move them to the risk-and-safety office.”

…The Royal College team interviewed Letby and described her as “an enthusiastic, capable and committed nurse” who was “passionate about her career and keen to progress.” The redacted section concluded that the senior pediatricians had made allegations based on “simple correlation” and “gut feeling,” and that they had a “subjective view with no other evidence.” The Royal College could find no obvious factors linking the deaths; the report noted that the circumstances on the unit were “not materially different from those which might be found in many other neonatal units within the UK.” In a public statement, the hospital acknowledged that the review had revealed problems with “staffing, competencies, leadership, team working and culture.”

…In May, the police launched what they called Operation Hummingbird. A detective later said that Brearey and Jayaram provided the “golden thread of our investigation.” That month, Dewi Evans, a retired pediatrician from Wales, who had been the clinical director of the neonatal and children’s department at his hospital, saw a newspaper article describing, in vague terms, a criminal investigation into the spike in deaths at the Countess. “If the Chester police had no-one in mind I’d be interested to help,” he wrote in an e-mail to the National Crime Agency, which helps connect law enforcement with scientific experts. “Sounds like my kind of case.”

That summer, Evans, who was sixty-seven and had worked as a paid court expert for more than twenty-five years, drove three and a half hours to Cheshire, to meet with the police. After reviewing records that the police gave him, he wrote a report proposing that Child A’s death was “consistent with his receiving either a noxious substance such as potassium chloride or more probably that he suffered his collapse as a result of an air embolus.” Later, when it became clear that there was no basis for suspecting a noxious chemical, Evans concluded that the cause of death was air embolism. “These are cases where your diagnosis is made by ruling out other factors,” he said.

…Evans relied heavily on the paper in other reports that he wrote about the Countess deaths, many of which he attributed to air embolism. Other babies, he said, had been harmed through another method: the intentional injection of too much air or fluid, or both, into their nasogastric tubes. “This naturally ‘blows up’ the stomach,” he wrote to me. The stomach becomes so large, he said, that the lungs can’t inflate normally, and the baby can’t get enough oxygen. When I asked him if he could point me to any medical literature about this process, he responded, “There are no published papers regarding a phenomenon of this nature that I know of.” (Several doctors I interviewed were baffled by this proposed method of murder and struggled to understand how it could be physiologically or logistically possible.)