#The Artist is Maria Cosway

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the artist:

the art!

#ora parlo io 🥶#I love her fr#radical feminists do touch#women's art#women in art#women's history#The Artist is Maria Cosway#Maria Cosway

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a counter to a previous ask: which is your favorite Hamilton painting and/or portrait? Or, period artist? Just genuinely curious.

Hope you’re doing well!

First that comes to mind is that painting of him during his time as an artillery captain :3 ('twas the first pfp of this blog and is currently also my phone wallpaper). Second would be that iconic Trumbull portrait

As for period artist, I love love LOVE Maria Cosway <3 !!!!

She's like,,, my icon frfr. I discovered her from an offhand mention in a Tumblr post and that sorta started my interest with her :3 .

I not only like her because of her incredible talent in art, but also just reading about her life too !!

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there, it's the anon who asked about Maria Reynolds! I realized in hindsight (read: two seconds after I sent the ask lmao) that I got her mixed up with Maria Cosway, and then I realized that I don't know crap about her either. Reading past posts you seem to mostly cover stuff about Hamilton and the people surrounding him, and also Maria Cosway isn't American lol, but I hope you don't mind me at least asking anyway? Sorry for rambling it's cool if you don't answer

hey welcome back! don't worry, you're not the first nor the last person to do that lol. and don't worry! europeans are welcome here, so maria cosway is fair game for asking about. however, apologies for asking questions aren't so i hate you (jk ily <3) now i won't be able to go into as much detail because im not drawing from much of my own personal knowledge, but my internet sources will be linked!

Source: The Judgment of Korah, Dathan and Abriam by Maria Louisa Catherine Cecilia Hadfield Cosway

Maria Louisa Catherine Cecilia Hadfield Cosway was the first child of two hotel owners in Florence, Italy. As a young girl in a convent, she showed proficient artistic talent in both drawing and music. She was educated by Johann Zoffany and introduced her to other European artists.

She began painting by copying other works when she began to get recognition, allowing her to travel Italy. After her father's passing, she moved to London in 1779 and became well connected. One such connection was with Angelica Kauffman Church (not the same as Angelica Schuyler Church, though she was friends with her two) who was also a female painter.

Maria was introduced to Richard Cosway in London, and they were married in January 1781 for primarily financial reasons. The couple were within the most fashionable circles of the time. In 1786, the Cosways went to Paris where they met Thomas Jefferson. Maria and Jefferson became friends who flirted an excessive amount, and I found a really interesting article on that here.

Unfortunately, her husband was a grade-A asshole who wouldn't sell her works and stunted her artistic growth. I'm an artist, and I can tell you, a few months off can really do a lot of damage to your muscle memory and suddenly everything you put on paper looks like absolute shit, so I feel for her.

Maria had her only daughter, Louisa Paolina Angelica, in May 1790 but her health suffered afterwards. She went to Italy to recoup and returned to London in 1794. In 1796, her daughter tragically died.

Maria coped by turning to religion, Catholicism to be specifically (been there too, she just like me fr). However, on the plus side, she got her prints published by Rudolph Ackermann and made etchings of paintings at the Louvre which had been stolen during the Napoleonic Wars. She actually knew the Bonapartes personally and their patronage allowed her to open a girls' school at Lyons in 1803, which is so badass. She would later open another school for girls in Lodi in 1812.

Her husband died in 1821, and she sold his work at auction. She used some of the profit from these sales to fund her school in Lodi which is so fucking metal. She was actually made a baroness by the Austrian Emperor and Empress after they visited her school. That's also fucking metal.

She lived the rest of her life in Lodi where she died in 1838 near her school. In conclusion, Maria Cosway was more badass than I realized, and I think she's absolutely lovely. RAHHH WOMEN!!!

I hope this has helped. Again, sorry I haven't been able to go as in-depth, but I don't know Maria like that. I'm gonna give you extra sources just because I love you so much. I hope you can find a jumping off point!! European painters are always interesting, especially if they're badass, metal women who kick names and take ass, so I encourage you to do more research!!!

Sources: Maria Cosway- Royal Academy of Arts

Royal Collection Trust- Maria Cosway Collection (this has her art!!)

American Heritage- Thomas Jefferson and Maria Cosway (this was quoted in the post!)

Yale Center for British Art- Maria Cosway Was a Part of England's First Celebrity Art Couple

#history#maria cosway#maria hadfield cosway#european history#italian history#art history#women's history#18th century#1700s#1800s#19th century#thomas jefferson#angelica schuyler#angelica schuyler church#asks#publius originals

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Cosway, Georgiana as Cynthia from Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” (1781-82). Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees.

Revealed: The Sensational Lives of 6 Overlooked #BritishWomenArtists | A sweeping exhibition at London's Tate Britain spotlights the U.K.'s great women artists that history forgot.

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/women-artists-tate-britain-2525667

#MariaCosway #Georgiana #Cynthia #FaerieQueene #artherstory #artbywomen #womensart #palianshow #art #womenartists #femaleartist #artist

#Maria Cosway#art by women#art#palianshow#Georgiana as Cynthia from Spenser’s “Faerie Queene”#Faerie Queene

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The critics seemed to agree that Fuseli had personified an idea. The question was, what exactly was the idea?

Where paintings of visions were concerned, the critics seemed much more comfortable describing the visual conventions than they were at explaining what all this might mean. It took a Church of England vicar, Rev. Robert Anthony Bromley, Rector of St Mildred's in the Poultry, to be the first to suggest that The Nightmare might after all be about sex. In the first volume of his Philosophical and Critical History of the Fine Arts — Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (1793), Bromley included in his chapter on 'the qualifications essential in the constitution of moral painting' a longwinded sideswipe at Fuseli's picture. He did not mention the artist by name but he did not need to:

the dignity of moral instruction is degraded, whenever the pencil is employed on frivolous, whimsical, and unmeaning subjects The Night-mare, Little Red Riding Hood [exhibited by Maria Cosway at the Royal Academy in 1783], The Shepherds Dream, or any dream that is not marked in authentic history as combined with the inspiring dispensations of Providence, and many other pieces of a visionary and fanciful nature, are speculations if it be right to follow Nature, there is nothing of her here, all that is presented to us is a reverie of the brain mere waking dreams, as wild as the conceits of a madman. [A recent commentator] very properly calls these persons 'libertines of painting': as there are libertines of religion, who have no other law but the vehemence of their own inclinations

In strongly implying that Fuseli was among the 'libertines of painting', Bromley was breaking new ground. Maybe The Nightmare was an example of the kind of libertine art which had been exhibited in recent Paris salons, or was known to be collected for private consumption by well-heeled connoisseurs. The Philosophical and Critical History continued - at great and pondero's length - to enunciate the principles that 'whatever is outré and extravagant can never be beautiful' and 'whatever is empty or poor of sentiment cannot instruct any persons'. Fuseli was furious. He took bitter offence at Bromley's attack on The Nightmare' it was one thing to encourage a public reputation for eccentricity and even for being 'Painter in ordinary to the Devil' - Fuseli did that whenever the opportunity arose, and on one occasion said of his diabolic reputation 'Aye, he has sat for me many times' - it was quite another to be publicly accused of being a libertine, especially to someone who was desperate to be accepted by the artistic establishment. So Fuseli wrote an ill-tempered notice of Bramley's book in the Analytical Review (July 1793]:

the whole [of Bromley's book] is delivered in the style and with the somnific loquacity of a drowsy homily ... the reader will forgive us if we refuse to enter into a more circumstantial analysis of a work which to us appears to have hardly any other title to grave consideration than its size …

Not content with this (the 'size' reference may have been an echo of criticisms made of himself), Fuseli then took part in a debate at Somerset House which resulted in the Royal Academy cancelling its subscription to the second volume of Bramley's History. This debate took place on 20 February 1794, and during the course of a heated discussion (which resulted in a vote seventeen to four in favour of cancellation), Fuseli's friend the painter Joseph Farington (1747-1821) helped to swing it by stating that 'a man who had written with so little delicacy on the works of living artists already might well traduce 'in his future volumes the professional characters of the very persons then assembled'. The vicar responded to these 'few men, acting in an Academic capacity' - and to Fuseli's 'shallow and contemptible objections' - in a series of seven letters published in the Morning Herald."

"Fuseli's The Nightmare: Somewhere Between The Sublime And The Ridiculous", Christopher Frayling (from Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake, and the Romantic Imagination)

#ska reads a thing#on the one hand this has an enduring resonance... on the other THE GIRLS ARE FIGHTINGGGGG

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 - Tate Britain

This was an ambitious exhibition, trying to cover the variety of women's professional art over four centuries. Each artist only had 2-3 paintings, which did make it difficult to assess their work, and for some, like Louise Jopling and Laura Knight, I would have loved to see a more substantive exhibition. These were some I liked:

Joanna Mary Wells, Thou Bird of God (1861) - title taken from a Browning poem

Elizabeth Butler, Calling the Roll After an Engagement, Crimea (1874) - quite a daring feat for a woman to do a large-scale history painting on a military subject, and quite an original and moving idea for a composition.

Louise Jopling, Through the Looking Glass (1875), fascinating that she chose this title for her self-portrait, only four years after the publication of the book. Is she commenting on the role of a female artist as a kind of fantastical, unreal creature?

Helen Allingham, Feeding the Fowls (1889-90) - my Mum loved these kind of idealised paintings of the countryside - this is what I would call a Milly Molly Mandy cottage (also one of my Mum's favourite children's books) - you come across lots of them unexpectedly where I live in Hampshire.

Emma Barton, The Soul of the Rose (1910) - there were some lovely early photographs in the exhibition but they really deserved an exhibition of their own.

There were some beautiful flower paintings in the exhibition (something women were allowed to excel in) - this is by Mary Moser (1744-1819)

I failed to note down who this Victorian sculpture was by, but it is rather fine.

Laura Knight, At the Edge of the Cliff (1917) - last(ish) but not least, Laura Knight really does deserve her own exhibition, her work was so interesting, and varied throughout her lifetime, from beach scenes, to theatre, circus and ballet themes to, of course, her portraits of women workers in World War II. I love the confident pose of the girl - just the sort of pose I'm usually shown in pictures of when I was a child - if there was a pile of rocks to get to the top of or a wall to be climbed, I was there. Recently saw a picture of my Mum as a child on top of a wall, which was a surprise given her later levels of inactivity, so perhaps the genes come from her - my son is a great wall climber so he's obviously inherited them.

Finally, an extraordinary feminist image to end on, Maria Cosway (1759-1838), The Duchess of Devonshire as Cynthia.

Overall, you do get a sense from the exhibition of the ways in which women's outsider position as artists allowed them to have an original eye.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now You See Us: Women Artists In Britain 1520-192016 May - 13 October 2024

Maria Cosway, Georgiana as Cynthia from Spenser’s ‘Faerie Queene’, 1781-82. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees / Bridgeman Images Tate Britain presents Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920. This ambitious group show charts women’s road to being recognised as professional artists, a 400-year journey which paved the way for future generations and established…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Nwt Moon Goddess Dreamer Kimono One Size.

0 notes

Text

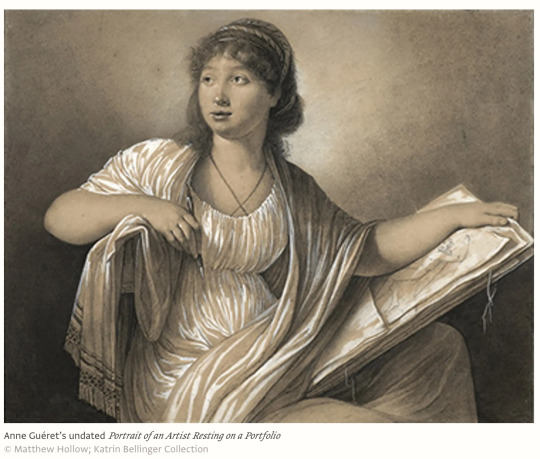

When talking about women artists, it is usual to reference Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? As Paris Spies-Gans—independent scholar and author of this new book—rightly says, it was a call-to-arms to make them visible. But that was over 50 years ago. One may ask now, what has changed since then? In recent years, the answer is a lot.

Around the world there has been a mini-flood of monographs and exhibitions on historic women artists, and their work is suddenly a profitable art market commodity. How to assess their careers remains a question, however. What was their place in and contribution to the art worlds they inhabited? Of what we know of them, what is inherited stereotyping on the one hand or over-eager feminist reading on the other? And to what extent is the current vogue for their work merely diversity box-ticking rather than genuine recognition?

This book sets out to place women artists working in Britain and France between 1760 and 1830—the “Age of Revolutions”—firmly within the art-historical narratives of the period. The task, Spies-Gans argues, demands more intellectual rigour than simply enhancing knowledge of their existence; and in an ideal world it should go beyond dealing with their careers as separate, simply because of their gender. A detailed analysis of the records of public exhibitions in London and Paris, chiefly the Royal Academy of Arts and the Académie Royale respectively, lies at the heart of this survey.

When talking about women artists, it is usual to reference Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? As Paris Spies-Gans—independent scholar and author of this new book—rightly says, it was a call-to-arms to make them visible. But that was over 50 years ago. One may ask now, what has changed since then? In recent years, the answer is a lot.

Around the world there has been a mini-flood of monographs and exhibitions on historic women artists, and their work is suddenly a profitable art market commodity. How to assess their careers remains a question, however. What was their place in and contribution to the art worlds they inhabited? Of what we know of them, what is inherited stereotyping on the one hand or over-eager feminist reading on the other? And to what extent is the current vogue for their work merely diversity box-ticking rather than genuine recognition?

This book sets out to place women artists working in Britain and France between 1760 and 1830—the “Age of Revolutions”—firmly within the art-historical narratives of the period. The task, Spies-Gans argues, demands more intellectual rigour than simply enhancing knowledge of their existence; and in an ideal world it should go beyond dealing with their careers as separate, simply because of their gender. A detailed analysis of the records of public exhibitions in London and Paris, chiefly the Royal Academy of Arts and the Académie Royale respectively, lies at the heart of this survey.

Consistent presence

Unusually for an art history book, data is presented in the form of charts and graphs. It is a powerful way of pressing home the point that the handful of prominent names that make it into standard art histories, such as Angelica Kauffman and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, are not exceptions in a male-dominated world, but part of a much wider and neglected story. Women, it is demonstrated, were a consistent presence in public exhibitions throughout the period. More than 800 individual women artists exhibited in London, and at least 400 in Paris. This is an astonishing statistic. It blows apart the clichéd but hard-to-shift notions of women artists as few in number, pursuing careers that blurred the lines between professional and amateur.

In fact, Spies-Gans sees this period as one that witnessed the first collective rise of the professional female artist. Women used public exhibitions for exposure and opportunity. How they trained, what they chose to exhibit, their networks and commercial acumen, and the strategies they devised to overcome obstacles because of their gender, are examined over six chapters. Preconceptions are regularly challenged.

For example, rather than “still-life” and “flowers” (the lesser genres), most women exhibited portraiture. Maria Cosway’s striking image of the Duchess of Devonshire as the moon goddess Cynthia (1781-82) shows the sitter wrapped in ethereal clouds in a clever blend of “celebrity”, history and literary narrative. The French Academician (one of only four women) Adélaïde Labille-Guiard depicts herself at her easel with two attentive female pupils behind her. It is one of many self-portraits, or images of fellow female artists reproduced in the book that show women proudly in the act of creation. And it is one of many painted on a large scale, demonstrating ambition and painterly skill.

Another preconception, the idea that (broadly speaking) women did not practise history painting as they had no access to essential life-drawing classes, or, put about at the time, because they lacked the capacity for “invention”, is here successfully critiqued. Angélique Mongez, a pupil of Jacques-Louis David, was one of many French women to exhibit large, complex classical narratives that incorporated nude figures while placing the focus on female protagonists. In this context, Kauffman’s decision to represent “Design”—one of four allegorical paintings for the ceiling of the Royal Academy—as female rather than male suddenly assumes more weight.

In support of its central and forceful point not to pigeonhole women along conventional lines, A Revolution on Canvas is illustrated mainly with portraits and historical works: those by Marie-Victoire Lemoine, Marie-Nicole Dumont (showing herself juggling painting and motherhood), Marie-Geneviève Bouliar and Marie-Denise Villers, or Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Adèle Romany and Constance Mayer, may come as a revelation to most readers. And yet, while applauding this desire to avoid stereotypes, perhaps the emphasis towards history and portrait painting, despite the data showing they were the two most exhibited genres (narrative in Paris was second to portraiture), has meant a drift from the complete truth. For the reality is that women did paint still-life, flowers and portrait miniatures. It was what artists such as Anne Vallayer-Coster did brilliantly. And where is landscape? The second most exhibited genre in London, we learn, but not discussed at all by Spies-Gans.

Revolutionary turmoil

Setting the context for women’s growing ambition to pursue creative, public careers was the era itself—the revolutionary turmoil that prompted debates about democracy and citizenship, which in turn shone a light on women’s rights. It was the age of the philosophical writings of Olympe de Gouges and Mary Wollstonecraft. Spies-Gans acknowledges the paradox in charting women’s increasing creative freedom at a time when political democracy did not extend to them. Another inevitable contradiction – in a book devoted to women artists—is the author’s call to embed their histories into broader art-historical narratives, rather than to continue to treat them separately. That, surely, is the ultimate goal.

But how many of the artists that are discussed in this book are genuinely recognisable names, and how many of the 1,200 named exhibitors are represented in public collections? It is still the case that when female artists are mentioned, the question “Were they any good?” still hovers. Books focused on gender are arguably still necessary. By making its points compellingly and driving the agenda forward, A Revolution on Canvas is an important contribution to the field.

Paris Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France 1760-1830, Paul Mellon Centre/Yale, 384pp, 157 col and b/w illustrations, £45/$55 (hb), published 28 June (UK) and 5 July (US)

• Tabitha Barber is the curator of British Art 1500-1750 at Tate and was the lead curator and catalogue editor/contributor of British Baroque: Power and Illusion (Tate, 2020). She is currently preparing an exhibition on historic women artists to be staged at Tate Britain in 2024

#Women’s history#women in art#books for women#A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France 1760 - 1830#Maria Cosway#Anne Vallayer-Coster#Anne Guéret

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georgiana Cavendish, duchess of Devonshire, as Cynthia, by Maria Cosway, 1782.

Italian-English portrait painter, 1760-1838.

#women and arts#women in the arts#women artists#female artists#italian artist#english artist#portrait#georgiana cavendish#cynthia#maria cosway#richard cosway#1782#painter#painting#18th century

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maria Cosway, after self portrait, 1787.

Clip Studio Paint, Rough and Lighter ink India ink brushes

For @StudioTeaBreak’s #PortraitChallenge on Twitter.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I thought I would share some portraits/info about notable black men and women who worked and lived in Georgian Britain. This is not an extensive list by any means, and for some figures, portraits are unavailable:

1. Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797) was a writer, abolitionist and former slave. Born into what would become southern Nigeria, he was initially sold into slavery and taken to the Caribbean as a child, but would be sold at least twice more before he bought his freedom in 1766. He decided to settle in London and became involved in the British abolitionist movement in the 1780s. His first-hand account of the horrors of slavery 'The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano' was published in 1789 and it really drove home the horrors of slavery to the general British public. He also worked tirelessly to support freed slaves like himself who experienced racism and inequality living in Britain's cities. He was a leading member of the Sons of Africa, an abolitionist group, whose members were primarily freed black men (the Sons of Africa has been called the first black political organisation in British history). He married an English woman, Susannah, and when he died in 1797, he left his fortune of roughly £73,000 to his daughter, Joanna. Equiano's World is a great online resource for those interested in his life, his work, and his writings.

2. Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780) was a bit of a jack-of-all-trades (he's described as an actor, composer, writer, abolitionist, man-of-letters, and socialite - truly the perfect 18th century gentleman). He was born in the Middle Passage on a slave ship. His mother died not long after they arrived in Venezuela and his father apparently took his own life rather than become a slave. Sancho's owner gave the boy to three sisters living in London c. 1730s (presumably as a sort of pet/servant) but whilst living with them, his wit and intellect impressed the 2nd Duke of Montagu who decided to finance his education. This was the start of Sancho's literary and intellectual career and his association with the elite of London society saw him ascend. He struck up a correspondence with the writer, Laurence Sterne, in the 1760s: Sancho wrote to press Sterne to throw his intellecrual weight behind the cause of abolition. He became active in the early British abolitionist movement and be counted many well-known Georgians amongst his acquaintance. He was also the first black man known to have voted in a British election. He married a West Indian woman and in 1774, opened a grocer's shop in London, that attempted to sell goods that were not produced by slave labour. Despite his popularity in Georgian society, he still recounts many instances of racist abuse he faced on the streets of London in his diaries. He reflected that, although Britain was undoubtedly his home and he had done a lot for the country, he was 'only a lodger and hardly that' in London. His letters, which include discussions of domestic subjects as well as political issues, can be read here.

3. Francis 'Frank' Barber (1742-1801) was born a slave on a sugar plantation in Jamaica. His owner, Richard Bathurst, brought Frank to England when Frank turned 15 and decided to send him to school. The Bathursts knew the writer, Samuel Johnson, and this is how Barber and the famous writer first met (Barber briefly worked as Johnson's valet and found him an outspoken opponent of the slave trade). Richard Bathurst gave Frank his freedom when he died and Frank immediately signed up for the navy (where he apparently developed a taste for smoking pipes). In 1760, he returned permanently to England and decided to work as Samuel Johnson's servant. Johnson paid for Frank to have an expensive education and this meant Frank was able to help Johnson revise his most famous work, 'Dictionary of the English Language.' When Johnson died in 1784, he made Frank his residual heir, bequeathing him around £9000 a year (for which Johnson was criticised in the press - it was thought to be far too much), an expensive gold watch, and most of Johnson's books and papers. Johnson also encouraged Frank to move to Lichfield (where Johnson had been born) after he died: Frank duly did this and opened a draper's shop and a school with his new wife. There, he spent his time 'in fishing, cultivating a few potatoes, and a little reading' until his death in 1801. His descendants still live at a farm in Litchfield today. A biography of Frank can be purchased here. Moreover, here is a plaque erected on the railings outside of Samuel Johnson's house in Gough Square, London, to commemorate Johnson and Barber's friendship.

4. Dido Elizabeth Belle (1764-1801) was born to Maria Belle, a slave living in the West Indies. Her father was Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer. After Dido's mother's death, Sir John took Dido to England and left her in the care of his uncle, Lord Mansfield. Dido was raised by Lord Mansfield and his wife alongside her cousin, Elizabeth Murray (the two became as close as sisters) and was, more or less, a member of the family. Mansfield was unfortunately criticised for the care and love he evidently felt for his niece - she was educated in most of the accomplishments expected of a young lady at the time, and in later life, she would use this education to act as Lord Mansfield's literary assistant. Mansfield was Lord Chief Justice of England during this period and, in 1772, it was he who ruled that slavery had no precedent in common law in England and had never been authorised. This was a significant win for the abolitionists, and was brought about no doubt in part because of Mansfield's closeness with his great-niece. Before Mansfield died in 1793, he reiterated Dido's freedom (and her right to be free) in his will and made her an heiress by leaving her an annuity. Here is a link to purchase Paula Byrne's biography of Dido, as well as a link to the film about her life (starring Gugu Mbatha-Raw as Dido).

5. Ottobah Cugoano (1757-sometime after 1791) was born in present-day Ghana and sold into slavery at the age of thirteen. He worked on a plantation in Grenada until 1772, when he was purchased by a British merchant who took him to England, freed him, and paid for his education. Ottobah was employed as a servant by the artists Maria and Richard Cosway in 1784, and his intellect and charisma appealed to their high-society friends. Along with Olaudah Equiano, Ottobah was one of the leading members of the Sons of Africa and a staunch abolitionist. In 1786, he was able to rescue Henry Devane, a free black man living in London who had been kidnapped with the intention of being returned to slavery in the West Indies. In 1787, Ottobah wrote 'Thoughts And Sentiments On The Evil & Wicked Traffic Of The Slavery & Commerce Of The Human Species,' attacking slavery from a moral and Christian stand-point. It became a key text in the British abolition movement, and Ottobah sent a copy to many of England's most influential people. You can read the text here.

6. Ann Duck (1717-1744) was a sex worker, thief and highwaywoman. Her father, John Duck, was black and a teacher of swordmanship in Cheam, Surrey. He married a white woman, Ann Brough, in London c. 1717. One of Ann's brothers, John, was a crew-member of the ill-fated HMS Wager and was apparently sold into slavery after the ship wrecked off the coast of Chile on account of his race. Ann, meanwhile, would be arrested and brought to trial at least nineteen times over the course of her lifetime for various crimes, including petty theft and highway robbery. She was an established member of the Black Boy Alley Gang in Clerkenwell by 1742, and also quite frequently engaged in sex work. In 1744, she was given a guilty verdict at the Old Bailey after being arrested for a robbery: her trial probably wasn't fair as a man named John Forfar was paid off for assisting in her arrest and punishment. She was hanged at Tyburn in 1744. Some have argued that her race appears to have been irrelevant and she experienced no prejudice, but I am inclined to disagree. You can read the transcript of one of Ann Duck's trials (one that resulted in a Not Guilty verdict) here. Also worth noting that Ann Duck is the inspiration behind the character Violet Cross in the TV show 'Harlots.'

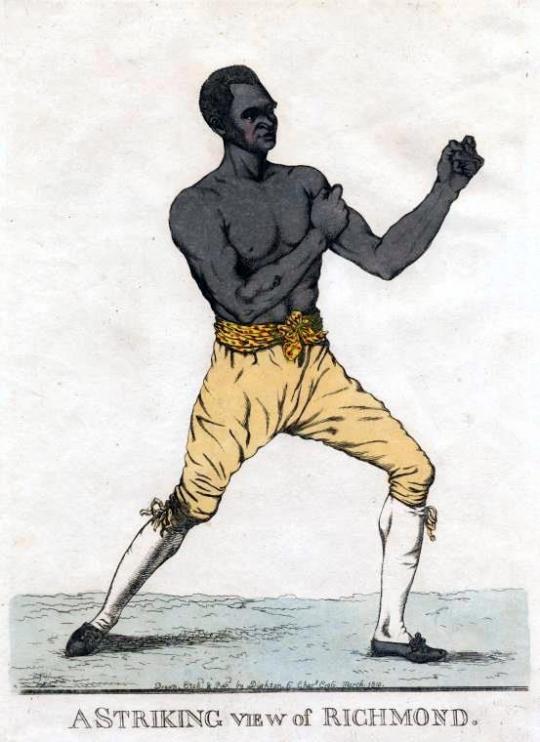

7. Bill Richmond (1763-1829) was a prize winning bare-knuckle boxer of the late 18th and early 19th century. He was born a slave in New York (then part of British America) but moved permanently to England in 1777 where he was most likely freed and received an education. His career as a boxer really took of in the early 19th century, and he took on all the prize fighters of the time, including Tom Cribb and the African American fighter, Tom Molineaux. Richmond was a sporting hero, as well as fashionable in his style and incredibly intelligent, making him something of a celebrity and a pseudo-gentleman in his time. He also opened a boxing academy and gave boxing lessons to gentlemen and aristocrats. He would ultimately settle in York to apprentice as a cabinet-maker. Unfortunately, in Yorkshire, he was subject to a lot of racism and insults based on the fact he had married a white woman. You can watch a Channel 4 documentary on Richmond here: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

8. William Davidson (1781-1820) was the illegitimate son of the Attorney General of Jamaica and a slave woman. He was sent to Glasgow in Scotland to study law at the age of 14 and from this period until 1819, he moved around Britain and had a number of careers. Following the Peterloo Massacre in 1819, Davidson began to take a serious interest in radical politics, joining several societies in order to read radical and republican texts. He also became a Spencean (radical political group) through his friendship with Arthur Thistlewood and would quickly rise to become a leading member of the group. In 1820, a government provocateur tricked Davidson and other Spenceans, into being drawn into a plot to kill the Earl of Harrowby and other government cabinet officers as they dined at Harrowby's house on the 23rd February. This plot would become known as the Cato Street Conspiracy (named thus because Davidson and the other Spenceans hid in a hayloft in Cato Street whilst they waited to launch their plan). Unfortunately, this was a government set up and eleven men, including Davidson, were arrested and charged with treason. Davidson was one of five of the conspirators to not have his sentence commuted to transportation and was instead sentenced to death. He was hanged and beheaded outside of Newgate Prison in 1820. There is a book about the Cato Street Conspiracy here.

9. Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (1705-1775) was born in the Kingdom of Bornu, now in modern day Nigeria. As the favourite grandson of the king of Zaara, he was a prince. Unfortunately, at the age of 15, he was sold into slavery, passing first to a Dutch captain, then to an American, and then finally to a Calvinist minister named Theodorus Frelinghuysen living in New Jersey. Frelinghuysen educated Gronniosaw and would eventually free him on his deathbed but Gronniosaw later recounted that when he had pleaded with Frelinghuysen to let him return to his family in Bornu, Frelinghuysen refused. Gronniosaw also remembered that he had attempted suicide in his depression. After being freed, Gronniosaw set his sights on travelling to Britain, mainly to meet others who shared his new-found Christian faith. He enlisted in the British army in the West Indies to raise money for his trip, and once he had obtained his discharge, he travelled to England, specifically Portsmouth. For most of his time in England, his financial situation was up and down and he would move from city to city depending on circumstances. He married an English weaver named Betty, and the pair were often helped out financially by Quakers. He began to write his life-story in early 1772 and it would be published later that year (under his adopted anglicised name, James Albert), the first ever work written by an African man to be published in Britain. It was an instant bestseller, no doubt contributing to a rising anti-slavery mood. He is buried in St Oswald's Church, Chester: his grave can still be visited today. His autobiography, A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as Related by Himself, can be read here.

10. Mary Prince (1788-sometime after 1833) was born into slavery in Bermuda. She was passed between several owners, all of whom very severely mistreated her. Her final owner, John Adams Wood, took Mary to England in 1828, after she requested to be able to travel as the family's servant. Mary knew that it was illegal to transport slaves out of England and thus refused to accompany Adams Wood and his family back to the West Indies. Her main issue, however, was that her husband was still in Antigua: if she returned, she would be back in enslavement, but if she did not, she might never see her husband again. She contacted the Anti-Slavery Society who attempted to help her in any way they could. They found her work (so she could support herself), tried tirelessly to convince Adams Wood to free her, and petitioned parliament to bring her husband to England. Mary successfully remained in England but it is not known whether she was ever reunited with her husband. In 1831, Mary published The History of Mary Prince, an autobiographical account of her experiences as a slave and the first work written by a black woman to be published in England. Unlike other slave narratives, that had been popular and successful in stoking some anti-slavery sentiment, it is believed that Mary's narrative ultimately clinched the goal of convincing the general British population of the necessity of abolishing slavery. Liverpool's Museum of Slavery credits Mary as playing a crucial role in abolition. You can read her narrative here. It is an incredibly powerful read. Mary writes that hearing slavers talk about her and other men and women at a slave market in Bermuda 'felt like cayenne pepper into the fresh wounds of our hearts.'

#18th century history#georgian britain#black history#olaudah equiano#ignatius sancho#francis barber#dido elizabeth belle#ottonah cugoano#ann duck#bill richmond#william davidson#uksawsaw gronniosaw#mary prince

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maria Cosway (English, 1760 - 1838): A Persian Lady Worshipping the Rising Sun (1784) (via ArtUK)

#Maria Cosway#Maria Hadfield Cosway#women artists#women painters#eighteenth century#orientalism#english painters#art#painting

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

POMPEO GIROLAMO BATONI

On this day of 25th January, Pompeo Girolamo Batoni (25 January 1708 – 4 February 1787) was born in Lucca, Italy.

He was a painter who displayed a solid technical knowledge in his portrait work and in his numerous allegorical and mythological pictures. The foreign visitors travelling Italy and reaching Rome during their "Grand Tour" made the artist specialize in portraits. Batoni won international fame largely thanks to his customers of noble origin, kings and queens of Poland, Portugal, and Prussia, the Holy Roman Emperors Joseph II and Leopold II, Popes Benedict XIV, Clement XIII, Pius VI, Elector Karl Theodor of Bavaria, and many more.

Batoni's style took inspiration from French Rococo, Bolognese classicism, and the work of artists such as Nicolas Poussin, Claude Lorrain, and Raphael. As such Pompeo Batoni is considered a precursor of Neoclassicism.

Pompeo Batoni apprenticed with Agostino Masucci, Sebastiano Conca and/or Francesco Imperiali.

Batoni owed his first independent commission to a sudden storm, when Forte Gabrielli di Gubbio, count of Baccaresca took cover under the portico of the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline Hill. Here the count met Batoni, who was drawing the ancient bas-reliefs and the paintings of the staircase of the palace. Gabrielli was so awed by his talent that he offered him to paint a new altarpiece for the chapel of his family in San Gregorio Magno al Celio, the Madonna on a Throne with Child and four Saints and Blesseds of the Gabrielli family

His notable followers include Vincenzo Camuccini, Angelo Banchero , Benigno Bossi , Paolo Girolamo Brusco , Antonio Cavallucci , Marco Cavicchia, Adamo Chiusole, Antonio Concioli , Domenico Conti Bazzani , Domenico Corvi , Felice Giani , Gregorio Giusti, Gaspare Landi , Nicola Antonio Monti , Giuseppe Pirovani , Pasquale Ciaramponi, Carlo Giuseppe Ratti, Henry Benbridge Maria Cosway Ivan Martos , Johann Gottlieb Puhlmann, and Johannes Wiedewelt .

The painter Benjamin West, while visiting Rome would complain that Italian artists "talked of nothing, looked at nothing but the works of Pompeo Batoni".

#pompeo girolamo batoni#pompeo batoni#master painters#famous painters#famous artists#art history#anniversary of artists#french rococo#bolognese classicism#neoclassicism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've read/heard historians say Thomas Jefferson is like a Jane Austen hero. Which is kinda of true in relation to his personality, but he's in a Bronte sister story with a horrendously unhappy ending for all the women involved.

He promises his dying wife Martha to never marry again, all their children die save for one. He falls in love in France with Maria Cosway, an Italian artist and married woman that has a reputation for leading men on. They write love letters and carry pictures of each other. But being the big fake puritan American that he is with a promise to his dead wife, he resists her and eventually starts to distance himself from her. So he starts to rape his child slave Sally Hemings instead and puts her in a hidden windowless room next to his. I've heard two versions of the next part, either Maria attempts to leave her husband or this happens after he dies, she goes all the way to the United States to declare her love and commitment for Jefferson. He turns her down and the situation is swepted under the rug. He kept his little picture of Maria though and carries on raping Sally.

His only surviving daughter by Martha is screwed over by his massive debt when he dies. His white passing daughters by Sally all have to hide their true identities for the rest of their lives to have any peace and security in a violently racist society that overly idealizes and worships their father.

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Aaa-ooo! So what’d I miss? What’d I miss? Virginia, my home sweet home, I wanna give you a kiss. I’ve been in Paris meeting lots of different ladies… I guess I basic’lly missed the late eighties. I traveled the wide, wide world and came back to this…

Lin-Manuel Miranda

Jefferson was essentially out of the United States for much of the mess of the Articles of Confederation since he was in France from 1785-1789. He did see a little bit of Europe during his time there, but he certainly did not travel across the world extensively. Very few of the Founding Fathers, even the ambassadors o foreign nations went very far outside of where they were required to go.

During his time as ambassador, he did have the chance to meet many different people, a few of them women who seemed to interest him. His wife, Martha Jefferson, had died on the 6th of September in 1782, and part of his reason for leaving to France may have been to try to escape the grief he felt for her, he may have felt he needed a change of scenery. Three years had passed since her death when he arrived in France, and he took up a delightful conversation through letters with Angelica Schuyler Church at one point during his time there. However, his real interest lay with Maria Cosway.

Maria Cosway was an artist, married to Richard Cosway, and was one of the people Jefferson grew close with while in Paris. His famous ‘Head and Heart’ letter was addressed to her, where he debates his feelings against his logical mind. With Cosway, his mind did not always win, for instance, he was foolish enough to show off for her on a traipse through the forest gardens in France and break his wrist. It was never as easy for him to play violin again after that.

On of the interesting similarities between all of the women Jefferson was involved with after Martha Jefferson died is none of them were free for him to marry. They were either married already, Maria, or enslaved, Sally Hemmings. Many historians, and friends of Jefferson’s during his time, believe that when Martha Jefferson was dying, she asked Jefferson never to marry again - she had not had the kindest of times with her step-mothers and perhaps was worried for her (at the time) three surviving daughters.

Sources: the following sources were used - the collected letters/writings of Alexander Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton the Revolution, Ron Chernow’s biography of Hamilton, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton by Allan McLane Hamilton, Hamilton by Richard Syllia, and Charles Cerami’s book called Young Patriots. In addition, War of Two by John Sedgwick and Washington and Hamilton by Tony Williams were used throughout. Thomas Jefferson information: https://www.loc.gov/collections/thomas-jefferson-papers/articles-and-essays /the-thomas-jefferson-papers-timeline-1743-to-1827/1784-to-1789/.

Follow us at @an-american-experiment where we are historically analyzing the lyrics of Hamilton with a new post every day!

#hamilton#alexander hamilton#Lin-manuel miranda#hamilton the musical#hamilton an american musical#history#what'd i miss?#thomas jefferson#jefferson#sally hemmings#maria cosway#angelica schuyler#martha jefferson

12 notes

·

View notes