#Tennessee valley authority

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I got an eBay package that came from a church in Rhode Island. It had a lot of old stamps on the envelope.

#stamps#scrapbook#vintage#john f kennedy#Harry Truman#Nathaniel Hawthorne#Martin Luther#Tennessee valley authority#willa Cather#Paul Lawrence Dunbar#desert shield#desert storm#George Washington Carver

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Glandon family around the fireplace in their home at Bridges Chapel near Loydston[sic], Tennessee. Glandon's wife plays both the guitar and the organ."

Record Group 142: Records of the Tennessee Valley Authority Series: Lewis Hine Photographs for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)

This black and white photograph shows a family consisting of a mother, father, two boys, and a girl. The parents sit in unmatched wooden chairs. To the left of the fireplace, the mother sits playing a guitar. The father sits to the right holding a fireplace poker. One boy sits on the floor holding a small black dog. The girl sits next to him on the wide planked wooden floor. A pile of kindling is between them. The other boy stands behind his father’s chair. The stone fireplace has a roaring fire in it. The mantel is covered with photographs and prints. Fabric or paper covers the walls. On the far left a bureau of drawers with a mirror is visible. On the far right, there is a neatly made bed.

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A woman drawing water in the Appalachian Mountains, ca. 1930 - Tennessee Valley Authority

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

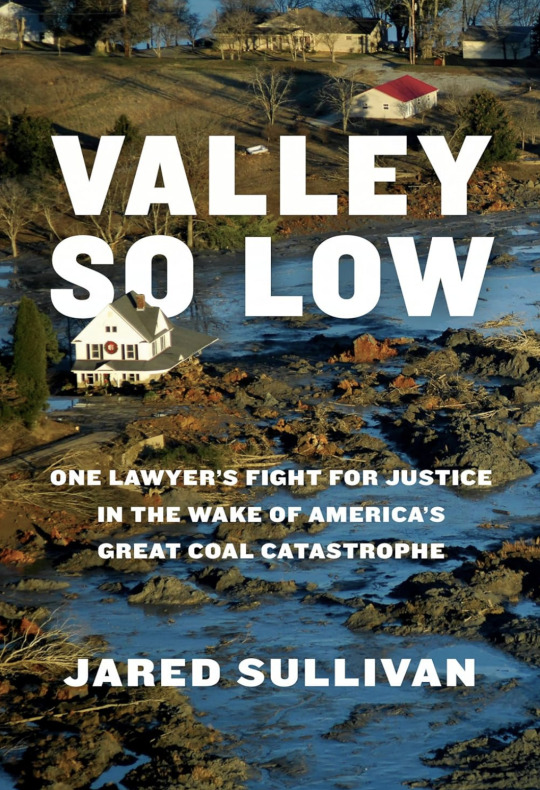

The Toxic Sludge That Ate Tennessee (New York Times)

Excerpt from review of the book, "Valley So Low" by Jared Sullivan in the New York Times:

A concise summary of Jared Sullivan’s “Valley So Low” is offered halfway through the book by its hero, Jim Scott, a plain-talking, suspender-wearing, Skittles-addicted plaintiff’s lawyer: “They had a toxic tub of goop, and it blew up.”

“They” are the Tennessee Valley Authority, the nation’s largest public utility. The “goop” is coal ash, the residual soot after coal is burned for electricity. Soot might not sound so bad (one pictures a burned-out campfire). But this coal ash contained arsenic, iron oxide, aluminum oxide, selenium, cadmium, boron and thallium, what Scott called “a Long Island iced tea of poison.” As for the “tub” …

The tub began as a spring-fed swimming hole. It stood near the site of the T.V.A.’s Kingston Fossil Plant, which, when it was completed in 1954, was the world’s largest coal-fired power station. Every day the plant burned enough coal to power 700,000 homes and produce a thousand tons of ash. The T.V.A. dumped much of that ash into the swimming hole. Over decades there rose from that pond, like a zombie crawling from a tomb, an ashy colossus. It broadened into a mountain range of coal slurry, sprawling across 84 acres — until, on the morning of Dec. 22, 2008, it collapsed.

A 50-foot-high tsunami of poisonous sludge buried docks and homes and soccer fields beneath mounds of coal ash as high as six feet. By volume, it was the largest industrial disaster in U.S. history, a hundred times the scale of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. But for years most of its victims believed themselves unharmed.

Anyone with a passing knowledge of Chernobyl, Deepwater Horizon or the World Trade Center cleanup will not be surprised by what happened next. The T.V.A. announced that exposure to the ash did not pose a “significant” health concern, but nevertheless barred journalists, lawyers, environmental groups and scientists from visiting the site. Workers were warned, under threat of termination, against wearing dust masks and hazmat suits, lest local residents grow alarmed.

One safety officer told his charges that they could eat a pound of ash a day and “be fine.” Incriminating air-monitoring data was ignored, manipulated or tossed out. Before long the workers, and the wives and mothers who cleaned their clothing, began feeling dizzy, having nosebleeds and coughing up “strange black jelly.” Later they discovered that the Kingston ash was not merely toxic. It was radioactive.

There is a grinding predictability to stories of industrial disaster, particularly when it comes to the behavior of the institutions responsible. Jared Sullivan, in his scrupulous account of the aftermath of the Kingston disaster, had not only to dramatize a convoluted series of abstruse, drawn-out legal cases. He also had to contend with his villains’ shameless lack of originality. The T.V.A. and the firm it hired to clean up its mess, Jacobs Engineering, played their assigned roles with great dedication. Nearly every strategic decision they made, Sullivan suggests, seemed calculated to be “cartoonishly wicked.”

While T.V.A. spokespeople urged the public to remain calm and downplayed the extent of the spill, internal communications revealed an institution adrift in confusion and incompetence. “This is unbelievable,” one employee says, despite decades of warnings. “We did not expect this.” The T.V.A. hired white-shoe law firms to force costly trials, refusing settlements and pursuing every delay tactic possible while the plaintiffs began to die off. Meanwhile, the T.V.A.’s chief executive — at one point the nation’s highest-paid federal employee — gave a speech declaring, “We’re going to clean it up, we’re going to clean it up right.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Toxic Wave That Swallowed a Tennessee Town

The night of the 2008 coal ash disaster in Kingston, Tennessee

#Industrial Waste#Tennessee#US History#2008#coal ash#disaster#Kingston#Pollution#Kingston Fossil Plant#coal#power station#Roane County#Tennessee Valley Authority#TVA

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#please sign and share#petition#petitions#please sign this petition#please share#please sign#climate action#climate science#climate activism#tva#tennessee valley authority#go green

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Checking Out: 1942 | Shorpy)

June 1942. "Wilson Dam, Alabama (Tennessee Valley Authority). Workers checking out at end of shift at a chemical engineering plant." Acetate negative by Arthur Rothstein. View full size.

#Wilson Dam Alabama#Tennessee Valley Authority#TVA#chemical engineering plant#Arthur Rothstein#new deal#1942#vintage

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was trying to capture the “fanboy Casey” moment for another post when I realized something adorable.

One of Casey’s pens has leaked.

One of the reasons I love “Loki” so much is because my father was an engineer for the TVA— the Tennessee Valley Authority. And he worked at their headquarters in Knoxville during the 70’s and 80’s. And the set design of this show really gets the Modernist aesthetic of those decades and thus, coincidentally, the aesthetics of the real TVA.

And so getting back to my dad being an engineer before the advent of desktop computers—most of his work when he started at TVA was calculated by slide-rule and hand-drafted, and if you needed to collaborate or get notes on something, you walked over to that person’s desk or took all your stuff to another floor or had big meetings, and you would stick your pens in your shirt pocket just like my boy Casey does.

My father wore a pocket protector, though, so that his pens, should they leak, would not stain his shirts, and while pocket protectors were viewed as “high nerd” by normies, the guys who didn’t use the plastic sleeves for their pens were thought of as nerds by their colleagues. Like nerdy nesting dolls, there were nerds-within-nerddom.

So I saw Casey’s ink stain and was immediately like, “Aw, Casey, honey, go get yourself a pocket protector.”

He’s just so deeply nerd-coded I love him.

#who worked on this show whose parent was also a government employee#i must know#loki#Casey TVA#tva#tennessee valley authority#time variance authority

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are y'all even ready for the results of me autistically deciding to do research on TVA's Tellico Dam?

The History of TVA:

Without a shadow of a doubt, the Tellico Project, first proposed by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in 1939, was the most controversial dam installment along the Tennessee River and its tributaries. TVA, having been formed three years prior to the inception of the idea to build a dam at the place where the Little Tennessee River meets the Tennessee River, was moving too quickly for it to keep up with its own progress. Born in the era of the New Deal, possibly given too much authority over itself, TVA soon found itself mired in discussion over its necessity and legitimacy.

From its inception, the Tennessee Valley Authority had the goal of producing energy for the region along the Tennessee River while also helping to control flooding along its length. The dams under TVA control were also used for the production of fertilizer (and munitions during wartime), transportation, recreational use, and urban planning. From Northeast Tennessee down to South-Central Mississippi, TVA also aided what were historically very impoverished areas in gaining access to affordable electricity. The first city to take advantage of this cheap hydroelectric energy was Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1934; in partnering with TVA to receive energy from the dams, Tupelo saw its energy costs decrease by roughly 68%, allowing for an 83% increase in the number of homes with electricity in the first 6 months of the partnership. This was a major step in modernizing much of the South.

But how did this government agency begin? What is the history of the Tennessee Valley Authority?

As previously stated, the Tennessee Valley Authority Act was passed into being in 1933, only two months into Roosevelt’s New Deal plans. With the creation of the TVA came control over the few dams which had already been built along the Tennessee River. The first of these dams was built in 1916 at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. This, along with the second dam to be constructed - Wilson Dam, named after then president, Woodrow Wilson - were built for the purpose of generating energy as well as producing nitrates and phosphates to be used as fertilizer for surrounding farms. Both of these had largely ceased production after the first World War. By 1923, the US Army Corps of Engineers had taken on the burden of building dams, with the plan to “form a navigable channel from Paducah to Knoxville” (Callahan, 1980), while also taking advantage of the power that could be generated from the construction of the dams. This was the foundation for the Tennessee Valley Authority roughly a decade later, and the mission they absorbed.

TVA was initially awarded 50 million dollars (adjusted for inflation, this is nearly 1.2 billion today) to construct more dams. This was for the goal of helping to control flooding, soil erosion, afforestation, elimination from agriculture use, and aiding in building up industries that could benefit from riverine transportation. Being the largest river in Tennessee, all water in the area eventually ends up in the Tennessee River, causing issues with flooding in many places across, and outside of, the state. In Tennessee alone, flooding was costing an annual 1 million in damages per year - that’s around 23 million today, adjusted. But TVA wasn’t just reshaping the landscape of Tennessee; it also brought with it the promise of jobs. Though some were waiting for the projects to fail, others saw it as a way to break out of poverty, or otherwise looked forward to the changes this new government agency was promising for the area along the Tennessee River.

The first major site the TVA chose for a dam was an area now known as Norris, Tennessee. By 1934, the area that was soon to be inundated had been cleared. Those who had been living there beforehand were bought out of their land and forced to vacate, much to the displeasure of many of the locals. In cases of eminent domain, there is not much one can do but complain, and so people were relocated, largely to the surrounding counties. When people refused to sell and leave their land, TVA had no issue with taking people to court over the disagreement; litigation was the end result in only 5% of all land purchases (about 801 tracts of land), however. Though TVA had promised to help the people impacted by the dam relocate, they did not always do this; in cases where they did, it sometimes resulted in people being lodged in areas knows as “poor farms,” where families and their livestock could stay (in tents, mind) until they were able to locate another tract of land. These tents were described by people at the time as being “not too bad.” Numerous graves also had to be moved. Though some preferred their family members be left where they’d initially been interred, over 5,000 graves were moved from the floodplain. The wishes of each family were respected, unless a grave absolutely needed to be moved for the purpose of construction. Continuing into the year, the Norris Reservoir Basin (as it was now called) was investigated for any evidence of past human occupation. Unfortunately - and this is largely a product of its time - sites were logged, but often not investigated properly. It was at this phase of construction that TVA decided the dam should be open to the public. After all, with so many people displaced due to its construction, they might as well still be able to utilize the land in some way, if for no other reason than leisure. It was argued that the dam would be an engineering marvel, something people would want to see, something that would revitalize American nationalism and inspire awe and pride in being American.

The next construction site was the General Joe Wheeler Dam, with the main purpose being to generate energy. This dam, along with Wilson Dam, were primarily used in times of heavy rains. Norris was not run until the water got low in the winter, ensuring a steady flow of electricity year round.

TVA began construction on the Pickwick Landing Dam in 1934. This was the first dam solely constructed and overseen by the Tennessee Valley Authority. For the rest of the decade, TVA continued to build more and more dams, expanding them from being along the Tennessee River to include several of its tributaries. When World War II began, dam construction was ramped up, reaching its full potential after the tragedy at Pearl Harbor.

In total, by the 1980s, TVA was in control of 58 dams along the Tennessee River and its tributaries. 23 of these were built by the TVA (that being Kentucky Dam, Pickwick Landing Dam, Wheeler Dam, Guntersville Dam, Nickajack Dam, Chickamauga Dam, Watts Bar Dam, Fort Loudoun Dam, Norris Dam, Hiwassee Dam, Cherokee Dam, Appalachia Dam, Nottely Dam, Ocoee Dam Number 3, Chatuge Dam, Fontana Dam, Douglas Dam, South Holston Dam, Watauga Dam, Boone Dam, Fort Patrick Henry Dam, Melton Hill Dam, and Tims Ford Dam). The Main River Wilson Dam was acquired by TVA after it took over the dam from the War Department. Three were acquired from the Tennessee Electrical Power Company (TEP): Ocoee Dam Number 1, Ocoee Dam Number 1, and Blue Ridge Dam. Calderwood Dam, Cheoah Dam, Thorpe Dam, Nantahala Dam, Santeelah Dam, Chilhowee Dam, Mission Dam, Queens Creek Dam, Tuckasegee Dam, Cedar Cliff Dam, Bear Creek Dam, Wolf Creek Dam, and East Fork Dam were previously owned by the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA). Wilbur and Nolichucky Dams were purchased from East Tennessee Light and Power Company (ETL&P). Great Falls Dam, Dale Hollow Dam, Center Hill Dam, Wolf Creek Dam, Old Hickory Dam, Cheetham Dam, Barkley Dam, and J. Percy Priest Dams were also major contributors, though not owned exclusively by TVA. Tellico and Raccoon Mountain Dams were still being tinkered with.

As the Tennessee Valley Authority acquired more and more land in the area, people began to worry about the impact this might have on life in the Tennessee River Valley overall. Whereas TVA had initially been seen as a good for locals, who were mostly impoverished farm workers, people were now considering the drawbacks. Unemployment in the areas affected by the dams was at a record low, but what about all the homes being destroyed? What of the archaeological sites now trapped beneath a man-made lake? How would all of this impact local flora and fauna? Though the Tennessee Valley Authority seemed inept in certain realms (such as project planning), they did fulfill some of their promises. Flooding was down in the entire River Valley, saving taxpayers, the government, and home and business owners alike millions (not adjusted for inflation) per year. However, the downside of this was that smaller waterways were now experiencing higher water levels, leading new areas to flood. Another benefit of the dams was that malaria and other mosquito-borne illnesses decreased rapidly; the movement of the water through various hydroelectric dams and the elimination of large patches of stagnant water helped limit the reproductive potential of mosquitoes. There was also the question of what would happen to newly flooded areas, and how this would be potentially detrimental to plant and animal species alike. Many worried about silt buildup along areas where fish typically spawned, and how this might limit the numbers of various fish populations; in the years since all these projects began, this has luckily been such a miniscule issue that it’s rarely something that even needs to be addressed. As well as trying its best to keep the environment mostly at balance, TVA was helping fight erosion by reforesting areas and planting native plants along previously ruined stretches of land; they also assisted in repairing soil quality by using the dams to help produce phosphides, which could be sold to local farms to help replenish the soil.

By the mid-70s, there were 400 access roads, 19 state parks, 91 local/city parks, and roughly 300 recreational areas open to the public along TVA-owned land. Having all of this available stimulated the local economy, an added benefit of the dams that had not been initially foreseen. Several tens of millions of people annually would visit these areas, making them a clear benefit for both TVA and people living near TVA lands.

Despite a few hiccups along the way, TVA had mostly been managed properly and professionally throughout the years. A shift had been made at some point to move away from a more industrial mindset to more of a community-focused one in response to Eisenhower threatening to dismantle the Tennessee Valley Authority for being too socialist. In this, locals had more of a say in what was being done in the area, a decision no doubt also sparked by new laws and regulations being passed about how TVA could act. The decision was made to build more along tributaries off the Tennessee River, which would not only help local communities with flooding, but also provide more affordable energy, jobs, and recreation areas. Revitalizing the backing for the Tellico Dam within TVA was the major step that was taken in doing all of this. Despite knowing that Tellico Dam would have no impact on energy production, transportation, or flood control by 1959, it was still pushed by the TVA. The mindset of everyone involved in the planning was that it had to happen, no matter what. Tellico Dam had been proposed decades before, and TVA was adamant about it being finalized. By 1961, local opinions of the dam were that it should not happen.

Regardless of this, in 1963, the Tellico Project was approved by Congress.

Tellico Dam:

Having been placed on hold decades before due to the sudden involvement of the United States in World War II, Tellico Dam was scheduled to begin construction in 1965 after a movement to revive this particular project. It was asserted that, because of poor placement of the Fort Loudoun Dam, another would have to be placed in a nearby tributary to further aid in flood control. Knowing energy production and transportation would not be the purpose of this new dam, TVA scrambled to find justification for it being built; after all, they had to present some sort of reasoning behind each construction in order to get funding from the federal government. TVA ended up using “land enhancement, recreation, and general economic benefit” (Wheeler &McDonald, 1986) as their justification. They had also asserted that it would help modernize local communities, which they treated as if they were stuck decades in the past when they were, in fact, rather modernized. These all proved to be difficult to quantify, and, needing to have some idea of the long-term monetary benefits of such a monumental task as dam building, TVA believed they would fail due to their inability to crunch the numbers. But, being a government agency, this did not stop them in their pursuit to have Tellico Dam become a reality.

Since Tellico’s initial stages, TVA had been caught in controversy. Announced to the public in 1961, businesses near the proposed dam began to endorse its construction very early on. People began to notice very quickly, however, that the wording in the endorsement letters was all suspiciously similar. TVA denied any role in this, yet was also caught trying to bribe the Knoxville Chamber of Commerce into endorsing the Tellico Project; because of this, the popular theory is that TVA was paying businesses to back them. In order to keep things under control, TVA decided to: Deny the dam was even being built (something they did up until the time of its completion), lie to the public about how much land would need to be purchased in order to finish the dam, and pay for various local groups to endorse them. From this, the Little Tennessee River Valley Development Association was born. This organization was directly responsible for lobbying on behalf of the Tellico Project, helping to build a plan for developing the area, and ended up being rather useless.

Realizing their own ineptitude, TVA found rather quickly that it would need far more land than initially projected. Some 17,000 additional acres would need to be procured in order to successfully carry out their half-baked plans. This is in addition to the 16,500 acres that were to be flooded. Understandably, this caused a lot of community backlash. Once stating that they cared about the opinions of the community, TVA was now hellbent on the completion of Tellico Dam at any cost.

In 1964, TVA held a meeting at Greenback High School in Greenback, Tennessee. They were met with around 400 people from nearby communities; almost every one of them opposed the Tellico Project, concerned that it would have a negative impact on their lands, fish populations, and archaeological sites, among other factors. They argued that TVA was not listening to what the people wanted, and they were only doing what TVA wished instead. The accusations worried TVA, for this was their largest, most vocal, opposition yet. The dissenting side went so far as to invite Supreme Court justices to East Tennessee to look into exactly what TVA was doing. This brought the controversy to national attention, and TVA began accusing any detractors of being paid opposition; in reality, they were being chastised by several small groups which had little to no connection to one another save for their dissatisfaction with how the Tennessee Valley Authority was operating in their own back yards. TVA began to suspect everyone of being against them, from local farmers to ALCOA to writers. Needless to say, none of these small groups did much more than make TVA look foolish, as a bunch of people with little to no power are often helpless in the face of a government agency.

In 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson released the federal budget for the following year. In this, 6 million was allotted for TVA to begin the Tellico Project. Construction was set to begin in 1967. From that point until the early 1970s, TVA began absorbing more and more of the surrounding land. This led to additional outrage, as they were now evicting people that they had previously told were not to be affected by the land acquisition. What’s worse, TVA had no idea how many people they would have to displace by buying up the land. No numbers had been run on what they were doing to the locals they claimed previously to have cared for. When prompted for an estimate, they gave the answer of 600 families/households affected; in reality, it was much closer to 350. There was also the issue of lack of funds to purchase all the extra land. Still, this did not deter them.

Moving into the 1970s, environmentalists became a big problem for the Tennessee Valley Authority. So the environmentalists said, TVA had no environmental impact statement. In response to this, and under threat of a lawsuit, TVA threw one together haphazardly, resulting in another blunder. The resulting environmental impact statement showed that TVA would break even on the cost of the Tellico Project vs the monetary value land development could bring in (1:1 ratio); in reality, it was closer to a 3:1 ratio, meaning they were spending three times more than what they could feasibly bring in. To further embarrass TVA, an economics professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville had his students run the numbers from the official TVA report to find the inconsistencies. Once again, this made everyone responsible for the Tellico Project look like buffoons.

By 1971, almost all the land needed for the dam had been purchased. The concrete structure of the dam was in place, and any manipulation of the land surrounding the dam had already been completed. Despite running into issue after issue, TVA was pressing forward, doing what they could when they could. In December of that same year, TVA was brought to court over their incomplete environmental impact statement. As they always seemed to do, however, TVA wormed its way out of being sued, stating that any impact the dam would have on fish and plant species or archaeological sites would be nothing compared to the ecological damage left from an incomplete dam, citing erosion from them clear cutting much of the area around the river as a major ecological concern. Despite being set to flood that year, a hold was placed on this due to significant archaeological areas of interest along the floodplain.

In 1972, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals halted any further construction of Tellico Dam. This blindsided TVA, who had, up until this point, only been given a slap on the wrist when they were engaging in activities which may or may not be illegal. The terms of this pause in construction was only limited to the dam itself; noticing this, TVA continued to work on building access roads, working on the canal area, and buying more land. It was also during this year that TVA brought in paid archaeologists to say that there’s nothing wrong with the excavations being performed on various Overhill Cherokee sites, and that things should be promptly wrapped up.

In 1973, Chattanooga experienced a horrible flood. TVA used this to their advantage, stating that the flood would not have happened if only the Tellico Dam were built. This didn’t sway many in their direction. Later that year, a zoologist visiting the Little Tennessee River happened upon a species of fish he’d never seen before. This species, which was dubbed the snail darter, after its primary food source, would be the next tactic for halting construction of the dam. Per the Endangered Species Act, if the snail darter happened to be endangered, TVA would have to stop construction, perhaps indefinitely. While the paperwork for this was being looked through, TVA continued to cut trees and silt the water, which appears to have been an attempt to eliminate the snail darter before the federal government had a chance to deem it endangered or not. Development of the area also picked up steam, as TVA believed they would soon be made to halt everything. Thus far, 40 million (not adjusted for inflation) had been spent overall in construction and land acquisition costs, and TVA was now finding itself possibly in violation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

The following year, to add to the fight, people began to ask what would become of all the priceless Cherokee sites that would soon be buried beneath Tellico. A resurgence of appreciation for indigenous cultures led to more and more people being concerned about the state of these sites. Unfortunate for the (mostly white) people attempting to use Overhill Cherokee sites as the newest way to halt TVA, many Cherokee did not seem to care; this was in part to TVA hiring a white man, who did all he could to mute indigenous voices protesting the dam, as their Cherokee representative, but also likely due to the fact that it seemed as if TVA was paying off high ranking members of the Cherokee nation to act as if they didn’t care what happened to their ancestors. Ecological considerations were also made, which TVA was now notorious for failing to properly address.

It wasn’t until 1976 that construction was officially put on hold due to the status of the snail darter. By 1977, construction was to be halted until further notice. It was also in ‘77 that archaeology in the area ceased. Despite the court-ordered hold, TVA persisted. TVA had already constructed most of the dam and its surrounding structures, as well as acquired some 22,000 acres of land surrounding the flood plain. They argued that they’d already changed the environment so much that stopping now would do more harm than good, and that the snail darter couldn’t get to its natural breeding ground because of the dam; they asserted that relocating populations to different areas in East Tennessee would make more sense. The decision to force the Tennessee Valley Authority to stop construction was upheld for several years. It wasn’t until 1979 that Congress and the House of Representatives decided (allegedly by mistake) to exempt TVA from the Endangered Species Act. This was the final decision in the dam’s construction, and a fatal blow for all in opposition to it.

In November of 1979, the gates on Tellico Dam were closed.

Archaeology:

Though now buried beneath several meters of water, many significant archaeological sites had been found along the Tellico Dam floodplain. In 1967, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville began to dig in the floodplain, having received funding from the National Parks Service. Starting in 1968, UTK was also receiving funding from TVA itself. Despite having adequate funding, the work was very rushed, as flooding was initially planned for 1969 or 1970. Both for the time and with how modern archaeology is performed, the job was executed poorly. Little to no effort was made to ascribe meaning or context to what was found; oversight and security were not even a thought, leading to looting; the archaeologists on site were reported to have left trash everywhere. After being informed as to how their ancestors’ graves were being treated, more and more Cherokee began to protest. Meetings were made with the governor of Tennessee to halt what was being done, but representatives from the Cherokee Nation were told he had no power over what TVA did. In the Eastern Band Tribal Council of 1972, the Cherokee, as well as most other indigenous tribes present, agreed to oppose TVA in their endeavors. Sites along the floodplain were registered as historic places - only to be dismissed as not being relevant or significant enough. In all, these protestations mattered about as much as any before them, and countless archaeological sites were forever destroyed.

The data on these sites is shoddily thrown together and largely unanalyzed. Bag after bag of unprocessed artifacts and remains sit in the McClung museum (on the campus of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville), waiting to be looked at. Reports of the findings from the time are full of inconsistencies, making it hard to know what was actually found, where, and how reliable the reports truly are. Alongside tales of sites being found, collections being made, and no artifacts from the site ever turning up, it’s safe to say that 1) not much care was taken in collecting from the Overhill Cherokee sites, and 2) members of the teams conducting the digs were almost certainly stealing from the sites.

To the advantage of those performing the digs, holdups due to the discovery of the snail darter meant there was more time than initially anticipated to conduct surveys. Beginning in 1967 and ending in 1978, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville sent out various exploratory groups to map and excavate as many archaeological sites as they could under the 16,500 acres the dam would soon be covering. Priorities were placed in areas where little to no work had been done before, such as terraces and islands along the river, slopes along the floodplain where chert had been spotted, and down tributaries off the Little Tennessee. Areas heavy with weeds or pasture, that had recently flooded, or where clear cutting hadn’t begun were to be ignored. This left around 19% of the 16,500 acres to be explored, and only 34% of that number (some 1,000 acres) was exposed enough to yield any results. As with all things, there were roadblocks. Poor preservation, fields that had to be free of crops before exploration, land owners refusing entry to archaeologists.

Survey teams of two people at a time were sent out to areas of interest to find if there was anything significant in those areas. Teams worked on foot, presumably so as to miss as little as possible. During the seasons they were present, 129 new sites were located in the floodplain.

The first dig season was in 1967-68. This was mostly for the purpose of identifying sites and finding how long the Cherokee had occupied the Little Tennessee River Valley. As TVA had not yet acquired all the land needed, there were many tracts of land in the area along the river that archaeologists did not have access to. As this was the case, not much was gathered during this dig season.

Teams went back out in 1969-1971, this time in the hopes of excavating the supposed Overhill Cherokee capital of Chota, and to hopefully find the location of Tuskegee in the process. 29 new sites were located during this season. Of the 29 new sites, 10 seemingly contained no artifacts, as nothing from them ever made its way to the McClung Museum.

From 1972 to 1976, and then again in 1977-1978, UTK sent out two more exploratory teams, neither bringing back much of importance, at least in terms of what was deemed important at the time. It is important, when viewing the past, to realize that methodology and focus change over time. The main goal of TVA archaeology at the time was to locate sites and collect all that could be from them before the inevitable flooding. This was almost purely salvage work, whereas today more time would be spent carefully assembling everything present and helping to paint a picture of what life would have been like for the people who occupied each site. One of the major criticisms is how differently each site within the river valley was treated. Depending upon who was in charge of the survey, bias could be seen in test methods, collection methods, what counted as significant, etc., leading to rather unscientific and unreliable data collection.

In all, 29,722 total artifacts were collected from the sites found. These included: 21,757 lithics/lithic fragments; 5,943 ceramics/ceramic sherds; 2,022 Anglo-American artifacts; and 2,258 faunal remains. By the 1980s, the last of these categories had been almost entirely untouched. Though no exact number could be found for the number of human remains found along the Little Tennessee River, an estimated 500,000 fragments of human remains had been recovered, according to a report on a 1971 survey. Of the artifacts recovered from the surveys over the years, most were fairly local. However, many of the lithics found were sourced from great distances away (New England area down to the Gulf of Mexico region, perhaps up into the Great Lakes). Of the artifacts found from beyond local trade range, it was found that those artifacts were either repaired once broken, or that they were repurposed as much as possible, indicating that they were of a much higher value than local lithics and pottery.

As a general timeline, human beings have been living in the Tennessee River Valley for roughly 10,000 years. The first signs of human occupation in the valley occur in the Early Archaic Period (8,000BC - 6,000BC). It was during this time that runoff from the Smoky Mountains began to form islands and sandbars along the Tennessee River and its offshoots. These were prime habitation zones, as they provided the natural protection water brings. These areas, as one might expect, flooded regularly, leading to quick sedimentary deposits (and thus stratigraphic layers). People at this time were semi-migratory, spending a decent amount of each year in the same area, likely moving to follow migrating prey sources or to a more season-friendly part of the valley. Homes were arranged close to one another, with a hearth at the center of each. Because of soil conditions, little biotic evidence exists at these early sites; almost all human, animal, and plant remains would have long since decomposed. It is assumed, based on recreations of what people were doing in nearby regions, that women primarily gathered foods, cooked, wove, and tanned hides, while men would have been responsible for hunting, gathering lithic materials, and making tools. The average life expectancy was around 25 years of age; this is, of course, brought down by a high infant and child mortality rate, but most people didn’t live very long regardless of that.

The Middle Archaic (6,000BC - 3,000BC) was not very well documented, but contained some floral remains. Analyzing these, it can be seen that there was an overall increase in temperature at the time, as well as a decrease in rainfall. Because of these two factors, it is largely assumed that high temperatures and low rainfall are responsible for why there is less human activity in the region at the time.

From 3,000BC - 900BC (the Late Archaic), hunter-gatherer strategies improved, leading to an increase in population. There is the emerging reliance on more and more riverine resources, especially fish and mussels. It is also in this time period that social stratification becomes more easy to define. Trade routes outside the local area are established, leading up into the Northeast. Domestication is slowly being introduced. The first domestic plants in the region were squash and gourds, presumably originating in Mexico (though there is no evidence that the people of the Tennessee River Valley themselves were traveling that far). Turkey were domesticated and eaten; dogs were a food source, a work animal, and/or a companion depending on a variety of circumstances.

During the Early Woodland (900BC - AD200), there was a change in how pottery was made. Possibly due to the influence of other cultures nearby, it became popular to mix crushed quartz in with the clay one was molding. The traditional fluted point also shifts to be more triangular; the implication here is that the bow and arrow had arrived in the valley, as triangular arrowheads would have made sense in the context of that being the weapon of choice over a spear. There is also evidence of post holes, indicating homes were more permanent than before and people were perhaps leaving semi-nomadic lives behind for a sedentary one. The popular burial position at the time was to inter people in a flexed position, with their knees up to their chin and their arms wrapped around their legs; almost all burial pits were oval or circular.

The Middle Woodland (AD200 - AD600) is marked by a shift into the Hopewell Culture. This is evident by the emergence of blades (a type of flake knapped from chert, obsidian, or similar rock) above more traditional styles of knapping. Trade networks were expanding, evidenced by materials from further and further away being found in the Tennessee River Valley. Though wild flora and fauna still dominated the economic structure of the Tennessee River Valley, cultivated plants (now expanding to include things such as corn, beans, sunflowers, maygrass, knotweed, lambsquarters, and marsh elder) became more of a dietary staple. At this point, it was almost assured that people were staying in the same residence year-round.

Nothing of note seems to have happened during the Late Woodland (AD600 -AD900).

The Mississippian Period is when activity begins picking up in the valley. Ranging from AD900 through AD1600, many changes were made to economic and social structures amongst the indigenous people of the Tennessee River Valley. First is the emergence of mounds. These functioned as burial sites, temples, residence for elites, and council buildings. In addition to this new type of structure is how villages are arranged; instead of being located near one another, now structures were located around a central plaza. Populations in these villages were also higher than they’d ever been, leading societies to both be more stable than before and more susceptible to warfare. Warring among tribes was so common that most villages of any size had a palisade built around them in an attempt to keep invading people out. Chiefdoms arose in this time period, along with further social stratification; chiefs would control the villages, with smaller settlements and farms surrounding their centers of power. Matrilineal lines become the basis for one’s social standing, meaning your status in society is determined by who your mother and her family had been. It was during this time that the first real hint of organized religion begins to show its face, mostly in the form of specific practices and ceremonies surrounding the dead.

Mississippian Culture died out ib the Tennessee River Valley long after it had in many other places in the Southeast. It is believed that the Spanish are responsible for the shift in culture from Mississippian to what is known as the Dallas Culture. After European contact, and the subsequent deaths of countless indigenous people due to the European diseases they had no natural immunity to, dogs being sicked on people, and weapons the Spanish brought with them, the Overhill Cherokee emerge. There is no real evidence of if the Overhill are descendants of the peoples who had been living in the Tennessee River Valley for generations, or if they were migrants who moved in after the Spanish were gone, but the leading theory is that they migrated into the area after the Dallas people were driven out.

Tellico Dam Archaeological Sites:

Many significant sites were found during the excavation years. Smaller sites deemed insignificant at the time have little recorded evidence of their existence, and thus the focus here will be on a few of the larger sites, on which literature is more readily available. All of the following is from those (mostly primary) sources, with the warning that there are inconsistencies within these forty to fifty year old documents that may lead the following to be mildly inaccurate:

Tomotley Site:

First recorded by Eurpoeans in 1894, Tomotley (40MR5) was a habitation site primarily used during the Late Mississippian Phase, but which has evidence of occupation dating back to the Archaic. There are four distinct periods of occupation at the site: Archaic, Woodland, Mississippian, and Historic. The later periods (Archaic and Woodland) are marked by the presence of lithics. Due to stratigraphic disturbances, pottery sherds and lithics from different time periods were mixed among one another; as this was the case, artifacts found were identified by style rather than how deep in the soil they were found. Based on post hole configurations, 14 total structures were located. These structures were constructed over a long period of time, evidenced by the depth the holes are found at. 6,268 total lithics were recovered, with evidence of occupation from all but the Middle Woodland Phase; the majority of these were identified as having been manufactured during the Mississippian Phase. 4,179 faunal remains were recovered. Evidence existed of a modern household once sitting on the site, likely having been constructed somewhere between 1750 and 1775. 84 total burials were identified. 55 of these were from the Dallas Period (AD1250 - AD1550). 8 were Overhill Cherokee. 20 were from an undetermined time period. As stratigraphy was messy, the period in which these people were interred was determined by grave goods associated with them. Those with no grave goods thus had no way of being determined, and were marked as unable to be determined. With modern techniques, it is entirely possible that these remains would be able to be analyzed today.

This site was excavated for a total of 5 days in 1967. It can be assumed that all artifacts recovered remain in the basement of the McClung museum, untouched.

Mialoquo:

Having first been placed on a map in 1761, Site 40MR3 was not considered a proper settlement by the Overhill Cherokee because it lacked a “townhouse.” Underneath the settlement, however, was evidence of occupation dating back to the Archaic Phase. 30 total midden pits were identified; 15 of these contained the refuse of the Overhill Cherokee, 3 were from the Mississippian, and 12 were unable to be determined. 692 total post holes were found, suggesting a long period of occupation before more modern times. A total of 4,986 lithics were identified, ranging from the Archaic through the Historic Periods.Very little found was from the Archaic Period, with the majority being from the Late Woodland to Early Mississippian. 6,677 ceramic sherds were recovered, ranging from the Woodland to Historic Periods. 2,987 faunal remains were identified; of these, 186 were molluscan, with the remainder being vertebrates (mainly whitetail deer and black bears). No mention of human burials comes from the report on this site.

Chota:

Though the report on Site 40MR2 was some 600 pages long, the majority was simply describing, in excruciating detail, what all was found. There was little to no analysis of what time periods the artifacts came from, simply that they were present. As this is the case, the details on what all was found for this site are clear, but the period of time they came from is not.

In total, 18,410 pottery sherds were located. Based on style, it is assumed that they are all from the Early Woodland through Cherokee occupation. An unstated number of lithics were recovered; though the report fails to state the total number, the breakdown is as follows: 287 were utilized flakes (broken pieces of projectiles that could be repurposed); 1,547 were chipped pieces; 5 were unworked nodules (stones chosen to be knapped into projectiles, but which never got used); 74 pipes, or pipe pieces; 1 chunkey stone; 7 anvil stones; 16 net sinkers; 2 gorget fragments; 8 hammerstones; 1 pestle; 3 slate saws; 7 bowl fragments; 10 chipped or broken hoes; 2 celts; 3 whetstones; and 93 stone fragments with evidence of human manipulation. This brings the total of lithics identified to 2,069. A plethora of Historic Era artifacts were also recovered: 19 projectile points; 14 gun parts; 1 powder horn; 23 musket balls; 1 explosive shell fragment; 9 pole axes; 16 knives; 2 straight razors; 3 pair of scissors; 2 saddle braces; 1 iron buckle; 1 strike lighter; 1 pair of eyeglasses; 1 hinge; 9 metal containers; 5 needles; 2 brass wire needles; 3 brass straight pins; 1 iron brace; 3 wood screws; 51 nails; 4 tacks; 40 buttons; 1 sleeve link; 2 broaches; 1 silver pendant; 5 ear ornaments; 32 tinklers (or, bells); 2 silver beads; 8 “c” bracelets; 1 gorget; 1 staple; 1 snuff box; 4 unidentified silver objects; 44 unidentified lead objects; 82 unidentified brass objects; 12,568 glass beads; 63 glass bottles; 14 pieces of mirror; 1 wine glass; 2 glass insets; 54 gunflints; 183 kaolin (a type of clay) pieces; 22 European ceramics; 9 European pigments. 944 total pieces of shell were identified, including 13 conch shell beads and 7 oyster shell beads. All faunal remains found were collected, but not analyzed or counted. Six total structures were able to be identified, as well as four houses. 17 human burials were found, with little detail into who they may have been, or from what time period.

Toqua:

Site 40MR6 was first investigated by European settlers in 1884. 57 burials were found at the time. The next time a professional dig was performed at the site was in the 1930s; an additional 100-150 burials were found in this exploration, but the people conducting the excavation were not concerned about the remains, but their grave goods. This being the case, all human remains were dumped along with the dirt moved to uncover them, with no effort being made to catalog or recover them. As can possibly be inferred from the way in which the humans whose final resting place was Toqua were treated, almost no record of this dig exists, save for the assemblage from it which made its way to McClung Museum. Proper excavation was not made until 1975. TVA had to purchase the land from its previous owner in order to gain access to the mounds which marked the site, and digging continued here for another two years, making it perhaps the most thoroughly excavated site under the Little Tennessee River. Five phases of excavation were performed: The preliminary survey, test excavations (specifically to gain an idea of the stratigraphy within Mound A), excavatory tests on the grounds around Mound A as well as into Mound B, excavation of Mound A, and comparison of results to other Dallas sites in the area.

At its height, Toqua would have covered around 4.8 acres and housed some 250 to 300 people. It was ruled as a chiefdom, with a matrilineal line dictating one’s social standing. Men of higher status were allowed to take multiple wives. Mound A, which took as many as 300 years to get to its full height, was constructed some time around AD1200. Starting around the second phase of construction (of which there were 16), humans began being interred into the mound. At its full size, Mound A would have stood 25ft tall and been 154ft in diameter. Mound B was constructed some time after this, though there was no definitive date for when this would have been. At its completion, Mound B was 6ft high and 93ft in diameter, and may have been built solely for the purpose of housing Toqua’s dead. In total, 133 structures were noted, as evidenced by the 10,127 post holes associated with the structures. Over 200,000 pottery sherds were found at the site, 212 of which were complete or near-complete. A total of 511 burials were recorded. Based on some of these remains, people at Toqua were purposefully flattening their foreheads by placing boards against them for days at a time; this could have been a status symbol or simply something they deemed to have been fashionable. There is also evidence that the people of Toqua may have relied too heavily on crops such as corn and not enough on red meat, as many of the individuals uncovered showed signs of an iron deficiency.

Conclusions:

The Tennessee Valley Authority, while bringing affordable energy and plentiful jobs to a part of the country in dire need of both, also brought with it the destruction of an unknowable amount of precious historic and prehistoric sites. One could argue the obvious tradeoff there being that sacrificing indigenous history in order to help the Tennessee River Valley in the modern day was worth it, but when the entire fiasco of the Tellico Project is taken into consideration, statements such as this simply do not hold water (pun intended).

Firstly, the dam was not constructed to be able to generate electricity. That was not its purpose. Jobs may have been created in the decades it took for construction to be completed, but the only real benefits of Tellico Dam are that it marginally decreased flooding along the Tennessee River (though it aided in smaller tributaries getting more flooding than usual) and provided recreational space.

Second, TVA was so hellbent on getting the dam finished that nowhere near enough time was spent exploring the inundated area. If more responsible, less egotistical people had been in charge, perhaps more would be known about these sites found beyond “people lived here, once.” But, instead, they routinely broke the law (continuing construction and seeming to be trying to destroy habitat in the case of the snail darter incident) and went against court orders to cease construction for lengths of time. The lack of care for both local people in the modern era and or the past is so evident that it’s a wonder TVA was allowed to continue their behavior.

TVA purposefully flooded an area in which this was not necessary in order to make themselves feel good. They had made a plan, and they intended upon completing it no matter what, whether that “what” be questions of its necessity or in spite of laws and regulations. It is clear that the Tellico Dam Project in its entirety was a blunder, a project pushed simply to sate someone’s ego. And, because of it, the archaeology work done in the area was rushed and haphazard, producing artifacts from which little can be derived, solely because of the pace at which they were collected. No time was afforded to do proper work, and so artifacts got tossed into bags and shipped off to McClung museum, if there was even enough oversight for them to have made it that far.

Had the time and care been taken in these excavations, had TVA had enough sense to postpone their project in order to allow the descendants of those who lived along the Little Tennessee River to understand a little more of their history, who knows what we would be able to say about these sites. Anything more than that is pure conjecture, however; perhaps there would have been little else to find. Perhaps major sites existed, overlooked in the hurry to get the job done, lost to history. Due to negligence, we will never know.

But there is still some hope on doing what can be to reconstruct the lives of the people who once resided in the Tennessee River Valley. Countless bags of artifacts exist in the McClung Museum, waiting for an aspiring young archaeologist to uncover their secrets. We may not be able to go back in time and do more thorough digs, but people today can still make basic assessments on what the Overhill Cherokee, and those before them, were doing, or eating, or making. The mistakes of the Tennessee Valley Authority can also be used as a lesson on what not to do in regards to someone’s ancestral lands, a talking point on how to do better in the future. Humanity makes mistakes as reliably as the sun will continue to rise and fall, but that doesn’t mean hope is lost. Wrongs can still be righted. Care can still be taken. Research can still be done.

Works Cited:

·Callahan, North. TVA: Bridge over Troubled Waters. A.S. Barnes, 1980.

·Chapman, Jefferson. Tellico Archaeology 12,000 Years of Native American History. Tennessee Valley Authority, 1985.

·Gleeson, Paul, and Howard H. Earnest. Archaeological Investigations in the Tellico Reservoir: Interim Report, 1970. Dept. of Anthropology, University of Tennessee, 1971.

·Guthe, Alfred K., and E. Marian Bistline. Excavations at Tomotley, 1973-74, and the Tuskegee Area: Two Reports. Tennessee Valley Authority, 1981.

·Kimball, Larry R. The 1977 Archaeological Survey: An Overall Assessment of the Archaeological Resources of Tellico Reservoir. Tennessee Valley Authority, 1985.

·Polhemus, Richard R., et al. The Toqua Site: 40MR6: A Late Mississippian, Dallas Phase Town. Tennessee Valley Authority, 1987.

·Russ, Kurt C., and Jefferson Chapman. Archaeological Investigations at the Eighteenth Century Overhill Cherokee Town of Mialoquo (40MR3). Department of Anthropology, the University of Tennessee, 1983.

·Wheeler, William Bruce, and Michael J. MacDonald. TVA and the Tellico Dam 1936 - 1979. Univ. of Tennessee Pr, 1986.

#not vc sorry#tellico#tellico dam#tva#tennessee valley authority#east tn#east tennessee#history#archeology#archaeologist#research#research paper#government agencies#tennessee history#southeast us#cherokee#overhill cherokee#tennessee river#little tennessee river#dam#chota#toqua#tomotley#mialoquo#tenasi#archaeological site#river#ancient#us history#cherokee history

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elon Musk's massive AI data center gets unlocked — xAI gets approved for 150MW of power, enabling all 100,000 GPUs to run concurrently

Elon Musk’s ‘Gigafactory of Compute,’ the xAI Colossus, received approval from the Tennessee Valley Authority in early November to receive 150MW from the state’s power grid. This increases the site’s initial supply of 8MW by almost twenty times, triggering concerns from local stakeholders about how this much power demand from xAI would impact supply reliability and power prices across the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

To the locals, this place is known as: Mondye Bottoms. Owned by the Tenessee Valley Authority. Located in the rural region of Franklin County, Alabama outside of the town of Phil Campbell. The foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. It is managed by the Bear Creek Development Authority.

#Mondye#Mondye Bottoms#Franklin County#Alabama#TVA#Tennessee Valley Authority#Bear Creek Reservoirs#BCDA#Phil Campbell#Appalachia#Appalachian Mountains#1978#ThisIsMineEO#TumbleDweeeb

0 notes

Text

Erin, Tennessee, September 13, 1943.

Record Group 142: Records of the Tennessee Valley Authority Series: Kodak Negative File File Unit: Kodak Negatives

Image description: View down an unpaved street. Two overalls-clad men stand outside a Texaco station under a large ad for Coca-Cola. At the end of the street is a two-story building with a pointed tower. Telephone/electric lines stretch across and along the street.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

very hard to concentrate on Loki when they keep talking about "the TVA" and you grew up in the Tennessee Valley

#“it's the TVA's fault” what did the Tennessee Valley Authority ever do to you#fynn posts#I have Never seen this show before

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from Canary Media:

The Tennessee Valley Authority, the nation’s largest public power utility, has yet to fully jump on the solar trend that’s sweeping the nation. But it has allowed communities within its seven-state service territory to buy some solar power for themselves. Now Tennessee-based developer Silicon Ranch has signed a contract to build the largest community-driven solar plant the region has ever seen.

Silicon Ranch will construct the multi-million dollar, 110-megawatt Copeland Solar Farm in Cumberland County, Tennessee, the company announced Monday. The farm’s output will benefit customers of Middle Tennessee Electric, the largest cooperative to receive power from the TVA. This arrangement will provide Middle Tennessee Electric’s 750,000 customers with cleaner power, insulate them from rate increases affecting TVA power, and help TVA grapple with the rapidly rising demand for electricity, which elsewhere has prompted the utility to greenlight massive and controversial new fossil gas plants

TVA has one of the more paradoxical approaches to clean energy of any major utility. Created by the federal government during the New Deal, it is governed by a board appointed by the president. But the arrival of Joe Biden’s handpicked board members has not yet prompted the public monopoly to align its power plant investments with Biden’s own climate goals. TVA’s electricity is cleaner than the national average, thanks to decades-old construction of hydropower and nuclear plants, but it gets just 3 percent of its power from wind and solar.

In 2022, TVA did put out a call for 5 gigawatts of clean energy projects, to be online by 2029; this was easily one of the country’s largest ever utility requests for proposals exclusively seeking clean energy. So far, TVA has signed five power purchase agreements from that process, totaling nearly 800 megawatts of solar generation and 20 megawatts of battery storage, spokesperson Scott Fiedler told Canary Media. But those projects have not been built yet, he noted, and the winning developers still have not publicized the details of their projects.

In the meantime, TVA has enthusiastically pursued new fossil gas plants, much to the chagrin of climate and ratepayer advocates. The board has repeatedly delegated power to CEO Jeff Lyash to approve large new gas investments; this happened most recently with the multibillion-dollar, 1.5 gigawatt Kingston project, as documented by Nashville public radio station WPLN.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mark Allen Stevenson, Tennessee Valley Authority in Vintage Postcards, Switchyard at Norris Dam, 1937

#my post#my scan#canoscan 300#photography#b&w#norris dam#rocky top#east tennessee#tennessee#1930s#tva#vintage postcards

532 notes

·

View notes

Text

some ideas i have for the Teen Villain Alliance

Dr. Danny "I stole my PhD from Harvard at gunpoint" Fenton is Damian's best friend despite being at least six years older than him, while Crown Prince Phantom Dark is more of a father figure to Damian despite them being the same flipping person.

Sam is still Damian's favorite though, she's the one who he approached to join.

someone suggested that each "squad" of teens has a different pest as their squad name. So the inner circle (Danny, Jazz, Sam, Tuck, Dani, maybe Klarion since he was there first) are Wolves, with each having a squad under them. Phantom doesn't have a squad, but Fenton's mad science squad are called rats, Jazz has mice, Sam reclaimed bats from the batfam, tuck has his flies, etc

Phantom and Pharaoh tuck pretending that they have no idea what Tennessee is because Wally mistakes them for the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Damian is convinced that the inner circle are Prince Phantom's harem and convinces Dick of that too when he joins.

I really want to add Dick to the Everlasting Trio guys, I really do, but this is about the Teen Villain Alliance, not young adult villain alliance, so the oldest I feel like I can make the trio are 20, with Dick being 24, so if anyone has any problems with that... i guess you can leave, I've already decided on this plan of action.

The first time Red Hood encounters the TVA, they threaten him into buying them alcohol, he buys the nastiest shit he can think of to mess with the brats. Klarion throws up, Sam drinks straight faced

Red Huntress originally liked being an official justice league recognized super hero, but the stress of work and being constantly relied on to save people wears her down. She confronts Phantom for setting these ghosts on her, but he hasn’t done anything, this is the regular amount of ghosts. In fact, he asked that most of his rogues limit their visits to once every two weeks, so its actually less. Valerie has a mental breakdown and joins the TVA

#dcxdp#dp x dc#dpxdc#dc x dp#everlasting trio#plus nightwing#teen villain alliance#mad scientist danny fenton#ghost prince danny phantom#pharaoh tucker foley#badass sam manson#c: danny fenton#c: damian wayne#c: dick grayson#there's a lot of characters i'm not tagging them all

2K notes

·

View notes