#Te Waipounamu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

(by Hari Nandakumar and Nareeta Martin)| South Island, New Zealand

#upl0ad5#landscape#Hari Nandakumar#Nareeta Martin#Lake Tekapo#New Zealand#South Island#Te Waipounamu#photoset#photography#aesthetic

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you need 6 minutes of four-handed nerve-soothing instrumental piano music played live alongside a bunch of birds singing in the mountains of Aotearoa New Zealand, I got you.

It’s here.

youtube

#piano#instumental#instrumental piano#amanda palmer#the dresden dolls#Luke Gajdus#four hand piano#piano improvisation#soothing#birdsong#newzealand#aotearoa#te waipounamu#Youtube

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

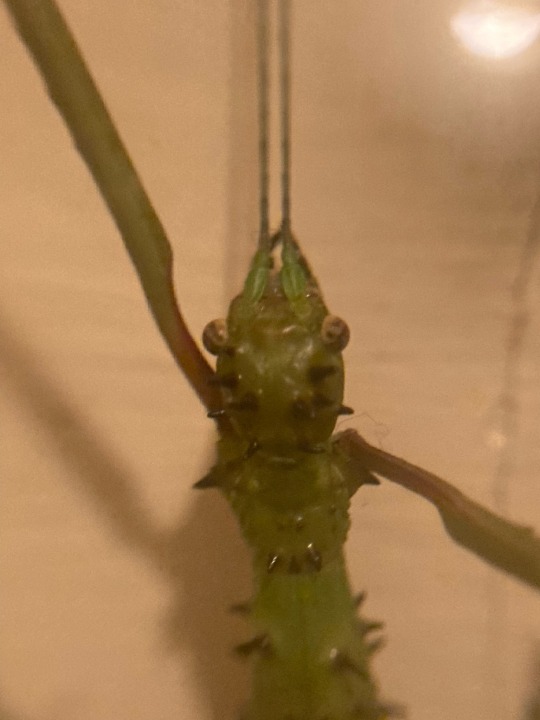

Acanthoxyla prasina, Spiny stick insect. Te Wai Pounamu, photo credit me.

The entirety of the Acanthoxyla genus is made up of species that are female only and reproduce asexually through parthenogenesis. This means that every member of a species are essentially clones of each other!

This genus most likely came about through hybridisation of two different stick insect species which produced a few individuals that, while could not reproduce sexually, still had the ability to reproduce asexually, creating a genetic separation and entirely new genus!

There are a few different Māori words that refer to stick insects more broadly, such as rō or whē, which are also used for many species of preying mantis, as it was thought that these two types of bugs were related. It makes sense, as they are very similar in looks and body plan, and many stick insects and mantises also have similar habitat requirements to each other.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Te Waipounamu (South Island) and Rakiura (Stewart Island), Aotearoa, February 2024

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

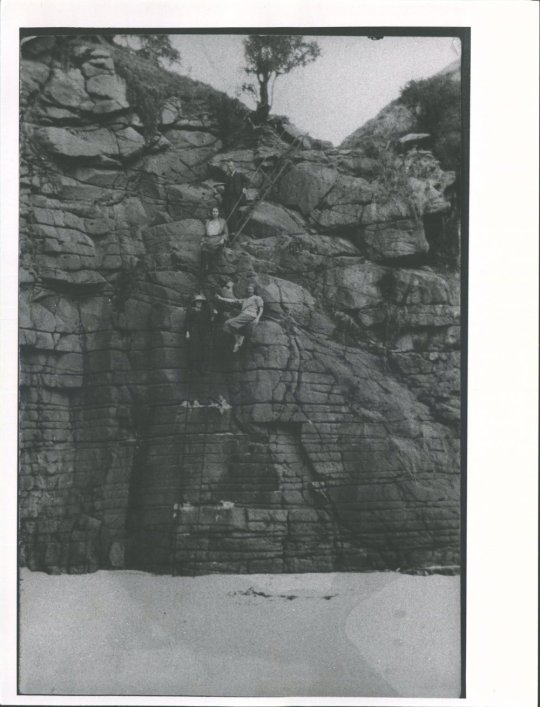

Rock climbers at Long Beach/Warauwerawera, Dunedin/Ōtepoti, New Zealand/Aotearoa, 1925

Image from The Hocken Library

#dunedin#new zealand#otepoti#otago#longbeach#long beach#rock climbing#1920s#1925#vintage#vintage photography#day trip#beach#Aotearoa#East Coast#South Island#Te Waipounamu#Warauwerawera

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

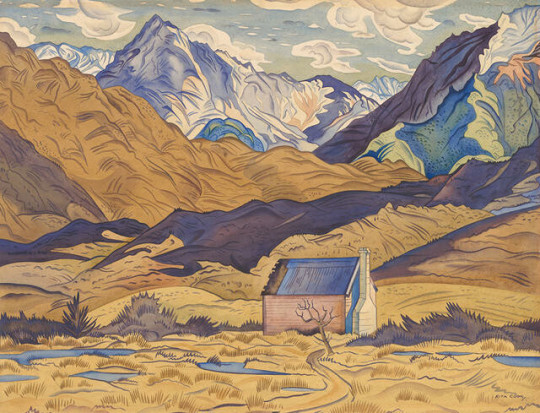

Mountains, Cass - Rita Angus

#1936#watercolour#art#high country#rita angus#mountains#hut#new zealand#te waipounamu#aotearoa#arthur's pass

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hell yeah it happened again! Taken by me, out my laundry door at 4am while I was flinging cat shit into the wilderness cos living rural rocks

1 note

·

View note

Text

Maungatua right now, seem from Dunedin airport

1 note

·

View note

Text

Great news! The Treaty Principles Bill was voted down, 112 votes to 11.

The Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi - ngā mātāpono o te Tiriti o Waitangi - and its "promise of two peoples to take the best possible care of each other" (as beautifully described by Bishop Manuhuia Bennett) have withstood this attempt to gut them of their original* meaning.

*Addition: This is NOT to say that promise has always been well kept by those in power, and it was so ignorant of me to have spoken of the Principles' "original meaning" - it has taken two wars and great effort to begin to address differing understandings of it.

Fifty years of ongoing work toward understanding and reaching agreement on the Principles has made some real progress toward redress of wrongs, but this bill would have undone so much of that work.

That's why this is such good news.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really should finally get a passport so i can go visit my gf.

#soupmother world tour (Te Waipounamu and nowhere else)#actually forget that (joking) i should get a passport so I actually have fucking documentation#because half of everything doesn't accept ID cards that aren't drivers licences

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

(for clarification, aotearoa is the original māori name for new zealand and is used widely across the country. nz is also often referred to as "aotearoa new zealand" instead of one or the other!!!)

please reblog because I'm kiwi and I need this to get to people who don't follow me directly for less biased results!!!

youtube

here's a pronunciation guide for all of you asking [:

EDIT: someone has brought it to my attention that the FULL māori name for new zealand is aotearoa me te waipounamu, which encompasses both north and south island. Some iwi (māori communities/tribes) would rather that aotearoa me te waipounamu become the official name for the country. thank you everyone who is providing opportunities for learning in this post!!

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

You cannot tell me that the Maori stories about what looked like a beaver lodge and dam in a place with no beavers are confused or unreliable, and you especially can't convince me when white settlers saw the same exact things. An actual specimen is needed to describe the species by western standards, but that doesn't erase the effects it's presence had on the ecosystem, including any constructions it made.

If someone finds what looks like an abandoned beaver dam in Fiordland, send me a pic!

New Zealand's lost a lot of wildlife, as colonization of a foreign land is prone to doing. It's particularly rough when a keystone species disappears; the landscape changes, communities disappear and the trophic cascade can be devastating.

This post is about the South Island waitoreke and how it built dams and lodges as reported by both Maori and English settlers

#but seriously#beavers have a massive effect on ecosystems of north america with how they manipulated water#and their loss is stark in places they've been killed off from#crazy drop in biodiversity of all kinds of animals and plants#why wouldn't the waitoreke do similar things in Te Waipounamu?#waitoreke#aotearoa#new zealand

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aurora Australis/The Southern Lights — Tai Tapu, Te Waipounamu, Aotearoa New Zealand

86 notes

·

View notes

Note

ooh, I'll ask - what's your headcanon for Australia, New Zealand, and Polynesia??

Thank you for asking! This was a fun exercise to get down in a doc and out of my head.

I think everyone knows that I’m Australian by now. So yeah, it’s particularly entertaining for me to imagine how things might be in the TLOUinverse on my side of the pond for a change.

Many Polynesian nations escaped Cordyceps completely – Tonga, Tokelau, Kiribati and the Cook Islands amongst these. They closed their borders and were essentially remote enough to be able to protect themselves from the first wave. However, that didn’t mean they had an easy time of it. Many of these nations rely on imports and with those grinding to a complete halt, they struggled in other ways to survive. Some of these nations also had unwelcome visitors in the form of refugees from other countries trying to fly or boat in. Most of these brought in sick people. Some of the nations formed methods of screening refugees who made it to their shores, others rejected them completely, and some nations fell apart over the ensuing years, unable to support so many people.

The North Island of New Zealand was completely overrun. The South Island had a bad few years, but pockets of it were able to resist, and within a few years they were able to rally and take the island back. They were mostly in control by 2005 – they were not fucking around – and Cordyceps-free by 2008. The nation officially reverted back to its name in the Maori language, Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu (but most just called it Aotearoa).

It was many years before they conquered the North Island, and then there were several years of warfare to fully secure it. The haka performed before the Battle of Auckland (which was one of their final victories over Cordyceps in 2015) was renowned the world over – the Kiwis documented much of their war on film, and these were distributed to survivors across the globe. These were often credited as inspiring a new generation of survivors not to endure and survive, but to fight.

Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu maintained contact with Australia throughout the war, but the situations in the two nations were very different. The densely populated centres of Australia were decimated. This is essentially all down the east coast from Brisbane, to Sydney, right down to Melbourne in the south. Darwin, right in the top end, was also destroyed, but this was mainly from refugees fleeing other nations. But Australia is a big, varied place, and not all was lost.

Many of the islands and remote towns around the country were able to find ways to survive. And the largest island, Tasmania, proved to be a haven. While its population centres were initially overrun like the rest of the continent, the army concentrated its efforts on eradicating Cordyceps in Tasmania first. There were three major offensives before they got the tactics right and were able to declare the state Cordyceps-free. The Government relocated here, but it was not the only success story.

Perth did okay. This is probably because the Infected, much like everyone else in Australia, thought it was too expensive and far away to bother with. Perth was the site of the first Quarantine Zone in Australia. Australia had a number of these over time but they were very different to the North American QZs. Australia’s tended to be constructed in remote areas, not large cities (with the exception of Perth). They each supported some kind of industry to try and keep civilisation humming along. These were not perfect, but most were successful.

The one in Port Hedlund said “fuck you cunts,” to the rest of the country and declared itself independent. The army didn’t much like that and it was dealt with pretty quickly. Wagga Wagga, with its RAAF and army training bases, was established not long after Perth and continued recruit training at Kapooka and Forest Hill. But some of the most successful survival stories came not from those within Australian Quarantine Zones.

Many Indigenous Australians, especially those in remote areas towards the centre, returned to country. Some of their camps and communities were overrun like everywhere else, but a lot survived. Some communities adapted so well that their lives were almost uninterrupted.

(It's difficult to explain the scale of Australia, and just how remote some Indigenous communities are, and how far they are from anything else. Suffice to say, there are people who know how to live on country in Australia in a way most of us cannot comprehend, and there are families and tribes that really could weather Cordyceps out - especially those towards the centre of Australia, where the conditions are dry and wholly unsuitable for a mushroom-based infection).

But the QZs kept in contact with one another and most importantly, with Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu. Trade recommenced between Tasmania and the South Island once both these zones were fully secure, and over time, links were reforged with other smaller nations in the region. The South Pacific Alliance was formed. By 2023, there was a good deal of cooperation – except for Perth, who also decided the rest of us could get fucked, and declared themselves as the Independent Nation of Perth or some crap. Nobody was really listening, they’re pretty far away and no one wanted to go there anyway so it was like okay good luck bye.

… I don’t really have beef with Perth. I’m sure it’s lovely. Anyway, thanks for the question! I'm not sure how plausible all of my theories are, but it's fun to consider.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great ACT-NSW-NZ Trip, 2023-2024 - St. Arnaud

After getting across Cook Strait without being shipwrecked (the weather was actually quite pleasant compared to some of the unholy gales that come through the gap, with the wind merely howling), we started our explorations of Te Waipounamu, the Island of Greenstone Waters. Pounamu is such a beautiful and useful stone that the Māori named the entire island after it.

Europeans called it South Island, or archaically New Munster. It covers 150,437 square kilometres, making it the world's 12th-largest island. We stopped at the Omaka Aviation Museum, which was worth it, but our first night was spent at St. Arnaud, formerly Rotoiti, a tiny alpine village.

It's certainly surrounded by mountains, and shows some really nice alpine geomorphology - hanging valleys left where subsiduary glaciers got cut off by the larger glaciers in the main valley, scree slopes where the greywacke of the mountains is disintigrating, and alpine lakes like Lake Rotoiti itself, formed when the glaciers retreated at the end of the last Ice Age and left behind huge piles of pebbles, gravel, and boulders to dam the meltwater.

On the other hand St. Arnaud has also been built right on top of a considerably larger geological feature - the Alpine Fault. This tectonic boundary between the Australian and Pacific Plates runs for over 600km, and is one of the fastest moving faultlines in the world, moving, on average, almost 40mm a year. Geological formations that originally straddled the fault are now 480km apart. Unfortunately most of that movement happens during huge earthquakes every few hundred years - the last big one on the Alpine Fault happens around 1717, rupturing 400km of the fault at once.

Over the last 12 million years a significant upwards element to the fault movement has been added, creating the Southern Alps. Most of what is now the South Island got pushed 20 kilometers up, whereupon New Zealand's weather promptly ground it 16 kilometers back down again. The assorted rubble forms the plains on the east and southern coast, or got swept north by prevailing currents on the west coast. Exposed basement rock on the South Island is mostly greywacke, or heavily metamorphised rocks such as schist from even deeper. That's where the greenstone originally formed.

Anyway, the next big quake will probably trash St. Arnaud completely, and cut every road across the mountains for months. Happily that didn't happen on this trip - @purrdence had enough problems with a cyclone cutting roads and trainlines last time.

The original forest around St. Arnaud is mostly Antarctic Beech (Nothofagus sp.) and forms the basis of a unique and seriously threatened ecosystem. I'll tell you all about that over the upcoming posts.

Here's some species I've covered before.

#st arnaud#new zealand geology#southern alps#alpine fault#alpine geomorphology#pseudopanax#araliaceae#new zealand plant#wahlenbergia#campanulaceae#blechnum#blechnaceae#nothofagus#antarctic beech#nothofagaceae#lycopodium#clubmoss#lycopodiaceae#discaria#matagouri#rhamnaceae#usnea#beard lichen#parmeliaceae#lancewood#Campylopus#new zealand moss#moss#star-moss#leucobryaceae

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aotearoa

znaczy "ziemia pod wielką białą chmurą" i jest to dzisiejsze rodzime określenie Nowej Zelandii w języku Maori.

Dlaczego dzisiejsze? Otóż przed przybyciem Europejczyków Maorysi nie postrzegali Nowej Zelandii jako kraju w obecnej formie i nie traktowali Wyspy Północnej i Południowej jako całości; mieli odrębne nazwy na obydwie. Północną nazywano właśnie Aotearoa, Południową — Te Waipounamu. Nazwa Wyspy Południowej nie zmieniła się do dziś, Północna jest zwana obecnie Te Ika-a-Māui, a Aotearoa zaczęła być utożsamiana z całym krajem.

Prawidłowe wymówienie tego śpiewnego słowa jest dla nas prawie niemożliwe, ale na pocieszenie dodam, że dla anglojęzycznych też. Bardzo słabym przybliżeniem niech będzie "a-o-ti-ro-a", ale tylko Maorysi potrafią ładnie połączyć tylnogardłowe "a" przechodzące w "o" z wibrującym "r" nietypowym dla angielskiego, ale nieco krótszym niż słowiańskie.

Gdzieś pod koniec XX wieku nazwa Aotearoa zaczęła być popularyzowana na fali wskrzeszania zainteresowania kulturą pierwotnych mieszkańców, jak też walki Maorysów o uznanie ich języka za urzędowy, co nastąpiło w roku 1987. Były nawet petycje, by nazwa maoryska została dołączona do oficjalnej nazwy kraju ("Aotearoa New Zealand"), ale nigdy nie zabrnęły one zbyt daleko.

Stosowanie nazwy Aotearoa przez białych jest obecnie swego rodzaju manifestacją inkluzywnych poglądów i promaoryskich postaw. Bardzo często występuje w oficjalnych komunikatach, zwłaszcza w telewizji, korporacjach lub wypowiedziach polityków lewicowo-centrowych. Użycie jej przez osobę dystansującą się od dziedzictwa pierwotnych mieszkańców kraju jest nieprawdopodobne. Nigdy też nie słyszałem, by używała tej nazwy nowa imigracja, czyli ludzie, którzy się tu nie urodzili — na moje wyczucie byłoby to sztuczne.

Co więc z samym znaczeniem dosłownym, "lądu wielkiej białej chmury"? Pochodzi ona z mitów maoryskich; któremuś z ich praprzodków drogę do nowej ojczyzny miała wskazać właśnie taka chmura. Jak czytelnicy wiedzą zapewne, gdyż sklepałem chyba dostatecznie paluchy pisząc o pogodowych fenomenach, rozległe ławice stratokumulusów oraz masywne fenowe wały altokumulusów występują tu nader często. Możliwe tym samym, że stanowiły jakąś wskazówkę dla dawnych żeglarzy. Odkładając więc na bok kontekst polityczny, Aotearoa określa Nową Zelandię pięknie i trafnie.

2 notes

·

View notes