#Tarpaulins Store

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I went outside to look for Steven, because it’s getting dark, and this is how I found her

These are terrifying, she was just sat there like that waiting.

#Steven#also I feel like the random assortment of things we have stored in that area of the garden makes it look creepier#like there’s a rope spade tarpaulin - looks like we could hide a body#plus the demonic looking cat#sitting amongst the chaos

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buy online the Best Tarpaulins Sheet Heavy Duty Waterproof at a Wholesale price We offer quick turnaround, fast shipping, and premium quality products. For more information contact us https://besttarpaulins.co.uk/ +44 20 3239 3962 [email protected]

#canvas tarpaulins#waterproof tarpaulins#transparent tarpaulins#tarpaulins sheet#pvc tarpaulins#economy tarpaulins#store#ecommerce

0 notes

Text

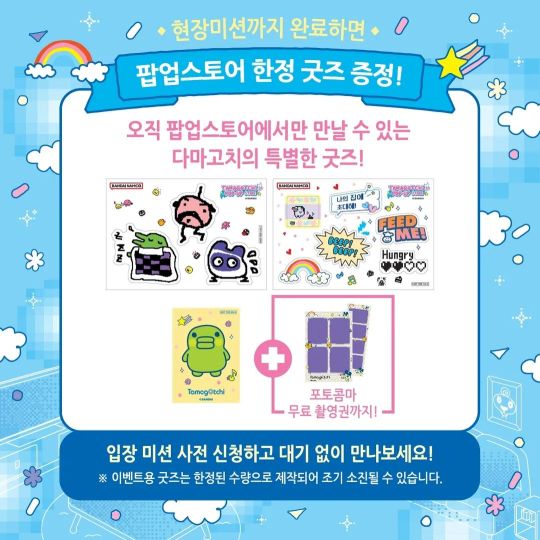

Bandai Korea Announces Tamagotchi Pop-Up Store

More pop-ups, more fun! Bandai Korea has officially announced their Tamagotchi Pop-Up Store which is set to open on Friday, November 15th, 2024! Although the event will be open to the public, there are early bird reservations that you can apply for. 300 of these reservations are available to enter as an early bird, and they’ll also receive a special gift. Reservation will open on Friday, November 15th, 2024 at 12:00AM.

The pop-up store is located at Torotoro Studio located at 1st floor, 7 Yeonjang 17-gil, Seongdong-gu, Seoul. At the pop-up store you’ll find lots of Tamagotchi goodies that you can only find at this pop-up store which include a string backpack (early bird only), knee blanket (early bird only), tarpaulin bag, Tama Stickers (Angel Balloons, Monster Balloons), Kuchipatchi photo card, and three other mystery items which have yet to be announced!

Not only will exclusive merchandise be sold, but also Tamagotchi devices of course! If you purchase a Tamagotchi, you can get your hands on the Angel Balloons and Monster Balloons Tama Stickers! Be sure to check out the Tamagotchi Pop-Up Store in Korea from November 15th (early birthday), Thursday, November 21st, 2024 through Sunday, November 24th, 2024!

Bring your Tamagotchi Uni, because you'll be able to use the Tama Search feature and you can meet Angel & Devil!

Learn more here.

Update: Bandai Korea has revealed the remaining merchandise on the Bandai Namco Korea official Instagram account. Bandai Korea also announced that they will be selling the Tamagotchi Some at the pop-up!

#tamapalace#tamagotchi#tmgc#tamatag#virtualpet#bandai#kr#korea#southkorea#south korea#popupstore#pop-upstore#pop-up#pop-up store#tamasearch#tama search#tamastickers#events

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last February, as the sound of automatic weapons erupted in the early hours before dawn, Amina Museni hurriedly packed a bag while her husband, Joseph, shook their three children awake. They were joining a group of neighbors fleeing their hamlet as the front line between the Congolese army and rebels of the March 23 Movement, or M23, crept closer. For days afterward, they walked across the hilly landscape of Masisi, in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, before reaching one of the camps that have sprung up around Goma, the capital of North Kivu province. There, they pitched their tent, a young family of five among more than a million people displaced by the resurgence of a conflict that has ravaged Congo for nearly three decades.

When Foreign Policy visited the camp last July, Museni sat amid an undulating sea of white tarpaulins stretched over eucalyptus sticks. “When I was little, I lived in a tent with my parents,” Museni said, her youngest child, Nestor, cradled into her neck. “Now my children have to endure the same. It feels like a curse.”

Why Congo has been in a perennial state of upheaval since the mid-1990s has been the subject of much debate, but no other narrative has cut through as much as that of so-called conflict minerals. In the 2000s, the link between markets’ demand for minerals and the war in Congo helped bring attention to the conflict in an unprecedented way. Western organizations such as the Enough Project and Global Witness mobilized around the seductive proposition that the solution to one of the world’s deadliest conflicts was within the grasp of consumers and policymakers, triggering a series of laws and regulations beginning with, in the United States in 2010, Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act. The logic behind the legislation was simple. “Armed groups finance themselves through the exploitation of cassiterite, gold, coltan,” Fidel Bafilemba, a Congolese researcher who used to work for the Enough Project, told me at the time. “By stopping the export of these conflict minerals, we dry up their resources and lessen the violence.”

Section 1502 required companies to conduct due diligence checks on their supply chain to disclose their use of minerals originating from Congo and neighboring countries and to determine whether those minerals may have benefited armed groups. The legislation didn’t outright ban the sourcing of minerals from mines contributing to conflict financing but instead intended “this transparency and its attendant reputational risk” to pressure companies to stop buying them voluntarily, according to Toby Whitney, one of the authors of Section 1502.

What followed is an important lesson for a world rushing to secure critical minerals for the energy transition. Western advocacy led to policies focused on derisking supply chains and virtue signaling to consumers, rather than improving artisanal miners’ living conditions or addressing the conflict’s root causes. That narrative continues today: An Apple store in Berlin was vandalized last week by Fridays for Future activists accusing the tech giant of sourcing so-called conflict minerals from Congo.

ITSCI, the region’s leading private traceability scheme, is facing criticism about the validity of its work—and that it has not improved the lives of artisanal miners in the region. ITSCI stresses its limited mandate and that it is working as intended. But in a cruel twist, the cost of the due diligence program has been shouldered by Congolese miners themselves, effectively asking the world’s poorest workers to pay for the right to sell their own resources to Western companies.

This week, industry leaders and activists gathering at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris for the annual Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains will need to reassess their approach. “We welcomed Dodd-Frank,” said Alexis Muhima, a Congolese researcher, during a meeting in a cramped office in Goma. “But what it did is outsource complex issues to the private sector, and we’ve been paying for it ever since.”

“The Americans didn’t think this through.”

There was a time in the 1970s when the quarries of Nyabibwe, a mining town in South Kivu province, were run with enough capital to employ 500 workers and to invest in semi-industrial machinery. Every month, the French company in charge shipped 20 metric tons of cassiterite ore—a component of tin—back to Europe for cans, wires, and solder. Safari Kulimuchi was a worker at the mines, starting at age 17, who quickly rose through the ranks to become a manager. “It was an exciting time. … Things seemed to be working out,” Kulimuchi recalled to Foreign Policy over dinner in Nyabibwe. But, he said, “it didn’t last.”

In the years that followed, Kulimuchi witnessed the economic unraveling of Congo (then Zaire), rotten under decades of rule by dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, who presided over the country from 1965 to 1997. Amid a global economic downturn in the mid-1980s, the French company departed, abandoning its workers to fend for themselves. “Overnight, we had no wages, no tools, no structure,” Kulimuchi said. “We used to have a stone crusher. Now we had to crush rocks with a hammer.”

Nyabibwe was far from an exception. Across the country, as investment dried up and the state abdicated its responsibilities, people resorted to making ends meet any way they could. An informal economy based on débrouillardise, or resourcefulness, sprouted in the ruins of Mobutu’s derelict regime. That informal economy is estimated to account for more than 80 percent of Congolese economic activity today. Nyabibwe grew into a town as people came from far and wide to work in the mines. They replaced the industrial machinery with picks and shovels, a low-capital, labor-intensive extraction called artisanal mining, as opposed to industrial mining. “Artisanal mining is the heart of our economy. It’s the reason Nyabibwe became this big center,” Kulimuchi said. The World Bank estimated in 2008 that up to 16 percent of the Congolese population depended on the sector. “For us, it’s a lifeline,” Kulimuchi added.

Mobutu was finally ousted in 1997 by a coalition helmed by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel army led by Paul Kagame. Kagame had just seized power in Rwanda in the aftermath of the genocide there and was intent on chasing after Hutus responsible for the massacres, many of whom had crossed into Zaire. What became the First Congo War brought Laurent-Désiré Kabila, a Congolese rebel, to power.

Kabila’s allies in the RPF quickly turned into foes when they refused to relinquish control over an area where instability threatened their security and interests. The Second Congo War began in 1998 with the creation of the RCD, a Tutsi-led, Rwandan-backed armed group that quickly gained control of a large swath of eastern Congo. The rebels began shipping cargo loads of coltan and cassiterite ores out of mines such as Nyabibwe’s into Rwanda just as the price of coltan, a key component of capacitors used in mobile phones and most electronic devices, soared with the demand for electronic goods at the turn of the century. A 2001 United Nations report estimated that Rwanda made at least $250 million during a temporary spike in prices in late 1999 and 2000. A popular formulation in Western campaigns at the time linked the violence in Congo to “blood phones.”

Many experts have criticized the advocacy of the 2000s for sometimes going so far as to suggest that conflict minerals were the root cause of the violence, painting armed actors as merely bloodthirsty, greedy militias—instead of considering real, historical grievances. The Enough Project campaigns, leaning hard on celebrities such as Robin Wright and Ryan Gosling to spread the group’s message, obfuscated the nuances of the conflict and the vital place of artisanal mining in the local economy. “The ‘conflict minerals’ label was problematic,” said Sophia Pickles, a former Global Witness campaigner and U.N. investigator. “This isn’t just about Congo—it’s a global issue.”

The campaigns succeeded in putting the issue on U.S. legislators’ agenda, but Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act was both too specific—singling out the so-called 3T minerals (tin for cassiterite, tantalum for coltan, and tungsten) in eastern Congo—and extremely vague on execution. It deferred the drafting of rules to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), leaving companies with no clear guidelines to report on their supply chain.

The law created a panicked scramble in the industry, said William Millman, a former technical director at Kyocera AVX, a leading manufacturer of electronic components and major coltan buyer. “Everybody was ignorant about the specifics. We just relied on our smelters.” Unlike an oil company directly operating its wells or a sneaker company outsourcing production to a sweatshop in Asia, electronics companies have virtually no way of knowing where the minerals in their products come from upstream of the smelters or refiners that have turned them into smooth metal—unless the smelters themselves know. “I visited all my suppliers to gather information. They knew very little because it was all largely bought on the spot market with international brokers,” Millman said. As a result of Section 1502, companies liable to fall under the SEC rule demanded that their suppliers simply stop buying from eastern Congo.

The result? A de facto embargo dropped like a bomb on the mining communities of North and South Kivu, just as the region was emerging from its latest cycle of violence. Nyabibwe had navigated two major wars mostly unscathed, but when I visited in June 2012, the town was in the midst of an existential crisis. Businesses dependent on the cash flow generated by the mines were closing down one by one, unable to sell stockpiles of rubber boots and shovels, blacksmithing services, or simply food. Tellingly, the local nightclub had shut its doors. More concerning were thousands of families’ insufficient funds to access health care, forcing women to give birth at home. One study found that the boycott increased the probability of infant mortality in affected mining communities by at least 143 percent.

Kulimuchi, who was then 54, was still managing a small team of undeterred miners. “The Americans didn’t think this through,” he said. His team had three metric tons of ore stored in a warehouse in Bukavu, South Kivu’s capital, waiting to be bought and shipped. “School is about to start again. Where are we going to find the money to send our children?”

Though U.S. lawmakers had struck out on their own with Section 1502, industrywide talks to create guidelines for the responsible sourcing of minerals in high-risk areas globally were already underway at the OECD. The OECD guidelines, adopted later in 2010, ended up becoming the foundation for the SEC rules, released in 2012. “The choke point in the supply chain is the smelters—everything has to go through them, and there aren’t many smelters in the world,” Millman said. “The OECD came up with a standardized protocol to audit and certify the smelters on an annual basis to know that they have control and knowledge of their supply chain.”

According to Millman, a handful of downstream companies seemed genuinely interested in doing things right and getting involved at the mine level. In 2011, together with Motorola and the Washington-based NGO Resolve, what was then AVX launched Solutions for Hope, a pilot project in Congo’s Katanga (now Tanganyika) province, where there was no conflict. They created a closed-pipe supply chain, sourcing from artisanal mines through a company that sold directly to a Chinese smelter and then onward to AVX, which manufactured components for Motorola and Hewlett-Packard.

Solutions for Hope also decided to hire the services of ITSCI. Its “bag and tag” traceability scheme set up by the International Tin Association (ITA) promised to trace minerals from the mine and guarantee their origin to buyers through a paper trail associated with sealed tags affixed on bags. According to Millman, Solutions for Hope was successful largely because its integrated supply chain bypassed traders and brought end-user companies closer to the miners. Replicating it would take time and effort. But, Millman said, “what other companies who had sat back saw was that, suddenly, with ITSCI there was a way for their CEOs and CFOs to sign off on their SEC statements. … And so everyone piled in, and it became the easy option.” ITSCI’s first project in eastern Congo was implemented in October 2012 in Nyabibwe.

“Do you think these people stopped working?”

Ten years on from when we first met, Kulimuchi came down from the mountainside where he had been working with his son on a sunny day last July, his broad smile still intact. The mining site hadn’t changed much either. Around us, men wearing flip-flops were using the same basic tools to split the earth open, with no protective equipment.

Initially, Kulimuchi recalled, the artisanal miners had been relieved when a large delegation showed up to officially launch the traceability scheme. “It meant we could finally start selling again. All my financial worries would be a thing of the past,” Kulimuchi said he thought at the time.

Instead, an elaborate public-private bureaucracy emerged, driven in part by regional governments intent on bringing the artisanal mining sector under control but quickly superimposed by foreign private sector initiatives like ITSCI, responding to market demand for paperwork required by end-user companies to file their reports to the SEC.

“We started selling again, but it’s a cacophony. There is a ton of admin, taxes after taxes, and prices have gone down. We have been weakened by all this,” Kulimuchi said.

As the de facto embargo on eastern Congo’s minerals lifted, by 2012 thousands of small sites across the region found themselves effectively outlawed by a new mine site validation process. To be able to sell, Congolese mining sites must now be inspected by a delegation of government representatives, NGOs, and U.N. agencies. At sites given the go-ahead from that audit, the Congolese artisanal mining agency carries out its own checks while also tagging and recording the minerals in logbooks for ITSCI. There are other records kept by the provincial government’s Mining Division and a regional body. Many sites are still waiting for an audit. For those that don’t conform, the consequences are devastating: “You are destroying the livelihood of hundreds or thousands of people,” said Maxie Muwonge, who was a program manager for the International Organization for Migration between 2013 and 2018 when it was tasked with coordinating the validation process. “This excludes entire communities. What are they meant to do? Do you think these people stopped working?”

In fact, even under the de facto embargo, the minerals trade never really stopped. It just went further underground. Rwanda’s export statistics, which experts say don’t match its reserves, suggest that smuggling to neighboring countries spiked during the period. While the volume of trafficked minerals has fallen with the reopening of the legal market in eastern Congo, smuggling is still an issue, not least because of the market distortion caused by heavy regulation and taxation in Congo of small businesses. “Many collapsed because they couldn’t meet the requirements, and the investment in the sector decreased. It broke down artisanal miners even further,” Muwonge said.

Joyeux Mumpenzi followed in his mother’s footsteps when he decided to become a négociant, an intermediary who buys minerals from the creuseurs, or diggers, and transports them to export companies in large cities—a reflection of the highly organized division of labor in the artisanal sector. ��To begin with, we have no say regarding the going price—the London Metal Exchange sets it, and it fluctuates constantly,” he said. “Then there are all the taxes, and finally, the export company retains a penalty on my payment for ITSCI.”

Today, 99 percent of ITSCI’s revenue comes from the levies it collects from upstream actors based on the volumes of minerals tagged and exported, ITSCI program manager Mickaël Daudin said in an interview. The organization says artisanal miners are not supposed to pay for the scheme. But the cost, or at least a percentage of it, is passed down the supply chain to the négociants and ultimately to the miners. “I have no choice” in doing so, Mumpenzi said. “I end up earning little more than they do, and I take huge financial risks.” The 33-year-old trader says he earns about $300 a month, while an artisanal miner’s household makes $200 on average.

ITSCI, which operates in both Congo and Rwanda, applies differentiated levies to businesses in the two countries. Daudin said that’s because “the cost of implementation … remains much higher” in Congo than in Rwanda but declined to disclose the levies’ rates; a Congolese government official called it a “conflict tax.” The rate discrepancy effectively encourages trafficking to Rwanda for Congolese mining operators keen to increase their margins.

A report published in 2022 by Global Witness cited “[s]ome industry sources” alleging that ITSCI was in fact set up to facilitate the laundering of Congolese minerals smuggled into Rwanda. Foreign Policy hasn’t been able to confirm the claim, but the tagging system that ITSCI created does offer the perfect cover for smuggling, in Rwanda or Congo. The integrity of the scheme relies entirely on the integrity of the people implementing it; the tags themselves offer no guarantee. In a statement released in response to the report, ITSCI wrote that it “strongly rejects all Global Witness’ stated or implied allegations of wrongdoing, facilitating deliberate misuse of ITSCI systems or illegal activity.” If ITSCI had aimed to maximize smuggling into Rwanda as alleged, a spokesperson wrote to Foreign Policy in an email, “ITSCI would not have launched in Katanga in 2011 nor in any other adjoining locations at other times. During 15 years of implementation, ITSCI has continued to expand the programme in [Congo], now supporting more than 1,500 sites across 8 Provinces.”

The Global Witness report also documented how the system can be breached without ITSCI’s cooperation. For starters, the tagging is not performed by ITSCI but by Congolese government agents who earn less than the miners themselves and sometimes go for months without pay at all. From bribing agents to trading in tags, the number of ways to circumvent the system is almost limitless—as Mumpenzi demonstrated to Foreign Policy. The négociant stood up from the sofa in his living room and walked to a corner where sturdy white plastic bags had been stacked. “See the tags? The bags were sealed by an agent before I picked them up yesterday,” he said. “The mineral sand now has to be washed, so when I’ll bring the bags to the washing station, the tags will be removed. When minerals are washed, the weight goes down, so this is a perfect time to smuggle in minerals before a new tag goes on. As long as the bag weighs less than it did initially, no one will say anything.”

ITSCI doesn’t rebuke such allegations categorically. The organization says it was aware of many of the incidents documented by Global Witness and had already addressed them. “The program isn’t perfect. There are issues, and there always will be,” Daudin told Foreign Policy. “But from my point of view, it wasn’t better before.”

Kulimuchi and other artisanal miners might beg to differ. Rather than improving their living conditions, the “increasing regulation of the artisanal mining sector and responsible sourcing efforts, have rather had a negative overall effect on the socio-economic position of artisanal miners,” analysts at the International Peace Information Service (IPIS), a leading minerals research institute, wrote in 2019. Guillaume de Brier, a researcher at IPIS, told me that “working in an ITSCI or a non-ITSCI site doesn’t change anything. Conditions are dismal in both cases. There’s no difference in terms of child labor, and miners don’t earn more.”

When asked by Foreign Policy about this criticism, an ITSCI spokesperson stressed the organization’s limited mandate as a traceability and due diligence not-for-profit initiative. “It does not function as a certification mechanism,” the spokesperson wrote, and the organization’s focus “does not extend to working conditions.”

However, evidence suggests that responsible sourcing efforts have failed to shift conflict dynamics. A 2022 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), part of its mandate to evaluate the impact of Section 1502, was titled “Conflict Minerals: Overall Peace and Security in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo Has Not Improved Since 2014.” Violence has instead risen, remaining “relatively constant from 2014 through 2016 but steadily [increasing] from 2017 through 2021,” GAO wrote.

Arguably, some measure of progress has been achieved at the 3T mining sites targeted by Dodd-Frank, where the presence of armed groups has decreased. But while ITSCI claims to have played a role, de Brier says the scheme merely implanted in sites where the situation was already better. Overall, this demilitarization has largely been the result of Congolese policies and the evolution of conflict dynamics themselves: The defeat of the M23 rebellion in 2013 (the armed group changed names multiple times as it successively integrated into and rebelled against the national army) led to the dismantling of one of the country’s most predatory mafia networks. Today, for instance, Bisie, once an iconic mining site under the control of Bosco “The Terminator” Ntaganda, is operated by the Canadian company Alphamin. (Ntaganda is serving a 30-year prison sentence in Belgium following his conviction by the International Criminal Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity.)

Now though, with the resurgence of the M23 rebellion since November 2021—which has displaced Museni, her family, and more than 2.5 million others—even that small measure of progress is under threat.

“This is how the armed groups are paid.”

Belgian colonial administration profoundly altered the Congolese relationship with the land, introducing private ownership and displacing people for commercial exploitation. Since independence, who has the right to own land—and by extension its resources—has remained an unresolved existential question. “The main resource driving conflict isn’t coltan,” said Onesphore Sematumba, an analyst at the International Crisis Group. “It is the land. It’s material ownership, of course, but also who has a legitimate right to be here.”

In the borderlands of eastern Congo, these questions have been exacerbated by intertwined histories with neighboring countries. Hutus and Tutsis, who arrived from Rwanda in successive waves throughout the 20th century—first brought by Belgian colonialists to work on plantations in the territories of Rutshuru and Masisi—have struggled to find acceptance and secure land rights. Rwanda, meanwhile, a small, densely populated country with little resources of its own, largely depends on economic ties and access to Congo’s resources. These two dynamics have helped create the vicious circle of the last three decades. Backed by Rwanda, the RCD rebellion and its successors claiming to fight for Tutsis’ rights have helped entrench tensions along ethnic lines while facilitating land grab by a small elite.

“Indigenous communities in Masisi were dispossessed of their land during the war,” said Janvier Murairi, a Congolese researcher. “Today’s farm and mine owners are people who had links to the RCD. Everything from Mushaki to Masisi town belongs to hardly more than 10 people.”

One such owner was Edouard Mwangachuchu, an aspiring Tutsi politician and a member of the RCD’s political branch, who was awarded a concession covering seven mines in Rubaya by the rebel administration in 2001. Two years later, the Sun City Agreement, a peace deal negotiated between rebel factions with little regard for social justice or community grievances, endorsed Mwangachuchu’s ownership over the mining sites as a prize of war for the RCD, granting his company, MHI (now SMB), control over what have become the most productive sites at Congo’s largest coltan mine. Today, Rubaya accounts for about 15 percent of global coltan production.

Rubaya is emblematic of the way ITSCI, and more broadly due diligence as it is practiced today, treats “conflictual issues, such as concessions and land ownership, … as a black box,” Christoph N. Vogel writes in his 2022 book, Conflict Minerals Inc., turning a blind eye to political issues around social justice and equity, even as those are drivers of the violence it means to help prevent.

In Rubaya, Mwangachuchu’s plan to turn the quarries into an industrial mine spurred a backlash from local communities. “The artisanal miners didn’t accept that this family [the Mwangachuchus] who had come into the possession of the mines through the conflict could take away their livelihood,” Murairi said. The government mediated a deal: The miners were allowed to continue mining SMB sites but had to sell exclusively to the company.

ITSCI began operating in Rubaya in 2014, tagging minerals from both SMB and peripheral sites belonging to a state-owned mining company, SAKIMA. But the situation unraveled as the scheme was embroiled in a tit-for-tat commercial war in the years that followed.

Suspecting that ITSCI’s tags were being used to launder the sale of its minerals to a rival trading company, SMB eventually turned to ITSCI’s main competitor in the tag-and-bag business, Better Mining. The move should have represented a major financial blow to ITSCI, the loss of roughly half its revenues for Congo. Instead, as production at the SAKIMA sites kept growing while SMB’s dwindled, ITSCI’s business was preserved. According to an internal U.N. report provided to Foreign Policy, “Only about seventeen percent of the production that officially originates from the SAKIMA concession has in fact been mined there.” The report noted that “[s]uch discrepancy between official data and reality is only conceivable if a structured mechanism of fraud is established.”

Daudin, the ITSCI program manager, responded that ITSCI is “confident about its data.” He argued that the production increase was due to the higher level of investment going to SAKIMA sites when local miners turned away from SMB.

The M23’s resurgence dealt the last blow to Mwangachuchu, who was arrested in March 2023 and charged with treason after weapons were allegedly found on the grounds of his company’s facilities in Rubaya. According to the prosecutor, Mwangachuchu intended to support the M23 rebellion. The government has since revoked SMB’s mining permits. Few people in North Kivu will feel sorry for Mwangachuchu, “but one of the protagonists was pushed out in favor of the other, and that never works,” said Achile Kitsa, a former private secretary to the provincial mines minister.

The Congolese army took full control of Rubaya last spring, leaving the former SMB concession at the mercy of local armed groups it used as proxies on the front line against the M23. “This is how the armed groups are paid,” said a Congolese researcher who spoke on condition of anonymity. ITSCI resumed its operations in June, tagging minerals from the SAKIMA perimeter up until November, when the road was cut off by the fighting, according to Daudin. “We relaunched our activities after evaluating each site with the government services,” he said in July. “There are no nonstate armed groups in our sites.”

In a December report, the U.N. Group of Experts on Congo contradicted Daudin, establishing that between June and November, the “production from [the former SMB] sites was either smuggled to Rwanda or laundered into the official supply chain using [ITSCI] tags for minerals produced in [the SAKIMA concession], where mining activities were still authorized.”

“ITSCI recognizes that there have been, and remain, ongoing risks regarding fraud and presence of both non-state and state armed groups in the area of Masisi territory, North Kivu,” the ITSCI spokesperson wrote. “These risks are regularly reported through ITSCI’s OECD-aligned systems.”

Muhima, the Congolese researcher, sees the possibility of tainted minerals in the ITSCI supply chain as inevitable, given its built-in conflict of interest. “Their income depends on the volume they export. They cannot stop tagging minerals, or their business will collapse.”

“We don’t need another scheme.”

Congolese activists were not pleased with the Global Witness report exposing the shortcomings of ITSCI when it was published in 2022. They felt that the research mostly rehashed criticisms and evidence that they had presented for many years without being listened to and that the report failed to draw the necessary conclusions, ending with tepid recommendations to reform ITSCI or consider options to replace it with another independent scheme. “We don’t need another scheme,” Murairi said. “We don’t need more foreigners who think Congolese can’t do anything.”

Global Witness’s cautiousness should perhaps not come as a surprise. The activist organization played no small part in paving the way for today’s conundrum, and the risk of triggering another de facto embargo on Congolese minerals hangs heavy. “We’ve learnt some very difficult lessons, and as an activist, I’m not the one who bore the consequences of bad policymaking,” said Pickles, the former Global Witness campaigner.

When I pressed Daudin last July about ITSCI’s resumption of its activities in Rubaya, even as armed groups were swarming the mining area, he dodged: “If we don’t start tagging again, mining communities will be the first ones to suffer from not being able to carry on their activities.”

ITSCI suffered a major setback in October 2022, when the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), a member association of more than 400 of the world’s largest corporations, announced that it was taking the scheme off its list of recognized upstream due diligence mechanisms. ITSCI had failed to submit an independent assessment of its alignment with the OECD guidelines in time. When the organization eventually released an independent audit in June 2023, it failed to assess ITSCI’s activities in Congo, focusing solely on coltan production in Rwanda. The RMI has offered to pay for three site visits in Congo, including in Rubaya, but ITSCI has so far not agreed. (“Site visits outside alignment assessments are not explicitly required,” said the ITSCI spokesperson, who noted the terms of such a visit are nonetheless under negotiation with RMI.)

“They are holding everyone hostage,” an industry insider close to the RMI process told Foreign Policy. “There is so much pressure on the RMI to capitulate and say we need this system. But this isn’t a technical issue.” To many experts and industry insiders, the resurgence of the M23 conflict has at least had the benefit of clarifying the situation. “The system cannot withstand what it was built for. It can’t withstand the conflict. We are back to square one.”

Breaking ITSCI’s quasi-monopoly is often presented as the solution in minerals circles, but SMB’s switch to Better Mining solved none of the problems in Rubaya and only created more confusion. Better Mining’s for-profit business model and its reliance on technology make it hard to scale and mean it is explicitly designed for larger companies with capital, not artisanal miners. “The problem with all these initiatives is that no one is there to control them,” said de Brier, the IPIS researcher.

Who is supposed to exert this control is part of the problem. Much like the fragmented nature of the supply chain, the nebulous ecosystem of public and private actors involved in responsible sourcing means that responsibility befalls no one in particular. In a July 2023 report, the GAO noted that the number of companies filing conflict minerals disclosures to the SEC had been steadily declining year-on-year since 2014, in part because “companies perceive that they are unlikely to face enforcement action by the SEC if they do not comply.”

Pickles noted that, unlike Dodd-Frank, the European Union’s own conflict minerals regulation, which came into force in 2021, avoided the trap of focusing only on Congo but equally fell for industry schemes such as ITSCI. “I’ve spoken to the competent authorities of three member states, and they said that the reports they receive from companies don’t tell them anything. They don’t actually know what’s happening along the supply chain,” she said. “So where does that leave us?”

For Congolese, ending this hypocrisy is a necessary first step but requires trust and support on the part of international partners. “The Congolese government has its own traceability system. All the necessary documents are delivered by Congolese state agencies. They tell you where the minerals come from just as reliably as ITSCI’s tags, which is to say it’s not perfect but it’s no worse,” Muhima said. “The same state agents deliver these documents and implement ITSCI’s program—for free I might add, since ITSCI doesn’t pay for them. What needs to be improved urgently is their payment.”

These lessons are relevant beyond the specifics of the 3T supply chain. The attention around cobalt—the conflict mineral du jour thanks to its use in electric vehicle batteries—is a case in point. While there is no conflict in the area where cobalt is extracted, working conditions and child labor have been discussed in much the same way as conflict minerals were back in the 2000s: in decontextualized and sometimes inaccurate reports that fail to examine the complex ways in which minerals interact with people’s livelihoods. Instead, such reports paint artisanal mining as illegitimate, something to eliminate. They have been used to justify land grab by large mining companies whose supply chains are easily traceable for end-user companies.

“We haven’t learned from our experience with diamonds or 3T minerals. With cobalt, it’s as if those experiences never existed,” said Joanne Lebert, the executive director of IMPACT, a nonprofit organization working on natural resource governance. “Instead of supporting communities, we’re just monitoring. There is no connection in my view between a clean supply chain and governance and security outcomes. Maybe you take kids out of your supply chain, but they’ll go to agriculture, to domestic work. They’ll go to another mine. They’ll sneak in at night. Clean supply chain is about eliminating the risk and not necessarily about doing good. And it’s the doing good we have to get at.”

Following the same pattern, an EU law aimed at preventing products linked to deforestation from entering the European market is pushing coffee companies toward industrial producers able to generate the paperwork and sidelining small farmers from Ethiopia to Brazil. Private companies will always take the shortcut, while black markets, exploitation, and conflict feed on exclusion.

Whether Western consumers like it or not, artisanally mined minerals will continue to find their way into the supply chains that fuel the energy transition and consumer products. Investing in mining communities’ welfare, education, and businesses is indispensable.

Museni is still living in the refugee camp on the outskirts of Goma with her husband and young children. Surrounded, the provincial capital has been struggling to absorb and provide for the constant new waves of displaced families reaching the city as the M23 is inching closer.

Even as evidence of Rwanda’s support to the rebellion has been mounting, the country has still not been sanctioned. In February, the EU signed an agreement “to nurture sustainable and resilient value chains for critical raw materials” with the Rwandan government, calling the country “a major player on the world’s tantalum extraction.” Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi described the deal as a “provocation in very bad taste.”

In Nyabibwe, Kulimuchi took me on a final walk around the town, waving around at the myriad businesses and hard-working people in the streets. “No one here has a bank account, for example. We can’t save. We can’t build,” he said. “We don’t require much—a road to Bukavu, a little boost, you know. Then, we’ll take it from there.”

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, I'm still not making much headway on chapter four of HYH, but I needed to write something or I was going to explode. So have a little bonus scene for the first story instead. :D It takes place somewhere after the mineshaft adventure but before the meteor shower.

}{

"And that one's the Gilded Goose," said Scott, pointing up at the sky with one hand while the other entwined with Jimmy's. "She's only visible at the height of summer. Then she moves on, and when winter approaches its peak the Red Wolf takes her place."

Jimmy gazed up at the pattern Scott pointed out in the stars, his thumb absently moving over the back of Scott's hand. "I can't believe how many there are," he said. "I bet if you combined every story from every place, there wouldn't be a single star left that wasn't part of something bigger."

"No, probably not," agreed Scott. It was one of the many things he liked about traveling; every region he visited saw the same stars in a different way, and every story he collected made the tapestry above that much richer. "Are there any that you know?"

"Just that one," said Jimmy, pointing in another direction. "I don't know any stories, but it's called the King. There's his sash, and over there is his crown."

"Oh, wow," said Scott, recognizing part of the constellation. "He overlaps with the Ocean Queen. You can't see the full pattern from here, but she's the most recognizable thing in the sky if you're near the Shallow Sea. They share a crown, I guess."

Jimmy laughed. "Maybe they were in love. Be a strange pair, though, a king of the mesa and a queen of the ocean."

Scott smiled. "Maybe they were." He lay his head on Jimmy's shoulder. "And now they get to dance together for eternity."

"Sounds kinda nice," said Jimmy, and pressed a kiss to Scott's hair. "Speaking of dancing, I'm sorry you didn't get a chance to when we went to town."

"Eh, it's alright," said Scott, then smirked. "I enjoyed what we did get to do much better." He didn't raise his head to see if Jimmy's ears were turning red, but he assumed they were from the squeak Jimmy made, and he laughed softly.

"Still," said Jimmy, "you said you like dancing. I just think it's a shame you didn't get to do something you – oh!" He sat straight up, the movement dislodging Scott from his comfortable position. "Wait, I forgot! There should be - " He jumped to his feet and darted over to the barn. Scott followed, curious, and watched as Jimmy dug around a corner where it seemed a variety of objects had been stored out of the way.

"Here it is!" Jimmy lifted a tarpaulin to reveal an old phonograph, then opened a chest below it and took out a record. "Let's see, how did this work again?" he muttered to himself, and after a moment of fidgeting with it, music filled the barn and spilled out into the night air as he successfully got the disc in place and spinning.

Jimmy grinned triumphantly, then went to where Scott stood in the doorway and offered his hand. "I, uh, don't actually know how to dance," he said as his grin turned sheepish. "But would you do me the honor of being my partner?"

Scott laughed, delighted by the music and Jimmy's eagerness. "I would love to," he said, and took Jimmy's hand. "Come on, I'll teach you."

He guided Jimmy through the steps of a simple waltz, and it didn't take long before they were swaying together in a comfortable rhythm. Once Jimmy had an idea of what was expected, his hold on Scott was confident and strong, but never lost its gentleness. Scott watched the moonlight slide across his face as they turned, and the way Jimmy gazed at him made him feel like his heart would drift away to dwell with the stars above if it got any lighter.

Scott's smile dimmed as a realization settled against his ribs. I can't do this to him.

Jimmy was not the first person to look at Scott like they were holding the entire world in their arms. It was another of the things he liked about traveling; sometimes when he found someplace to stay for a while, he got lucky and also found a pretty boy to have a little fun with. He would spend a few weeks pretending to be swept away by flattery and attention, until his admirer conveniently revealed the location of a hidden stash of gold or gems, and Scott's visit conveniently came to an end.

It should have been as simple as it always was. Jimmy should have been just like every other lover swept away by Scott's charm. Scott never dreamed anyone would be able to sweep him away in turn.

The record ended, and Scott and Jimmy drifted to a stop. "How was that?" asked Jimmy with a grin. "Was I okay?"

Scott smiled, feeling a pang in his chest at how easily his arms slipped around Jimmy's neck and Jimmy's arms slipped around his waist. "You were wonderful," he said softly.

Jimmy's grin brightened at the praise, and he pulled Scott into a kiss. Scott leaned into him, fingers caressing the nape of his neck, and he never wanted to let go.

He needed to let go.

In the end, Jimmy made the decision for them. "It's getting late," he said as he pulled away. "Let me get that back where it goes, and we'll go to bed."

Scott stepped back and watched Jimmy disappear into the barn again. "Thank you for the dance," he said when Jimmy returned, and their hands found each other again as they headed back to the house.

"You're welcome," said Jimmy, and pulled Scott's hand up to his lips. "I'll be your dance partner whenever you want. I can't imagine ever wanting to dance with anyone else."

Scott laughed, and he blamed the weakness of it on the late hour. "I'm sure you'll have plenty of dance partners in the future, and better ones than I am."

Jimmy's laugh was far warmer. "Impossible," he said, dropping to a near whisper as they entered the quiet house. "You're everything I could ever want."

series masterpost

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Storeroom Couplet

There are two connected storerooms in the basement, or at least one storeroom connected to another room.

We see the second of the rooms (and part of the other room) when Dad is preparing to battle the mischievous fairy… and when he was looking for his Polaroid camera.

This looks like a basement type room full of the sort of stuff one might have in a garage. Note that the Heeler’s house doesn’t have a true basement, it’s more a walkout basement level we’re on, and they don’t have a garage but do store tires in their garden shed.

Note the poster with “Queensland” and a pineapple in the other room. A framed poster might be a clue that the attached room is slightly nicer? (Like a game room or a “man cave” or something.)

There’s also (not a complete list!):

a stop sign,

some tools,

a workbench,

a filing cabinet,

some of Mum’s hockey trophies, and a trophy with a magnifying glass, maybe for Mum's work?

a drying rack for laundry,

a surfboard with a pineapple motif (pineapples are grown in Queensland)

a bodyboard (the short stubby board next to the surfboard),

a tarpaulin covering some house-painting supplies,

some sort of framed document,

a jerry can for water,

a dirty coffee cup,

and a can of WD-40.

There’s also a window.

I’m not 100% confident about the location of this pair of rooms; it might alternatively be one of the two doors off of the main room for instance. A future episode will likely help confirm the location of these rooms.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

PVC Tarp, PVC Tarpaulin Manufacturer, Professional Production Of PVC Tarpaulin | Jum Tarps

Jum Tarps is a professional pvc tarpaulin Manufacturer and have been supplying PVC tarpaulin for over ten years, As the PVC coated tarpaulin manufacturer in China we offer kinds of pvc tarp,pvc tarpaulin,lumber tarps,heavy duty tarp for you want.We can provide high-value solutions of PVC tarpaulin

If you are looking for the best PVC tarpaulins in various colors, sizes and weights sold at factory direct prices, then Jumtarps™ can meet your requirements. We are a leading provider of heavy duty PVC tarpaulins and lightweight PVC tarps. Shop and compare! Our online store offers you high quality, competitive prices, and we believe it is the best overall value found in the tarpaulin and covering industry. We provide a complete line of large heavy duty tarps that can meet almost all needs.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

passion can be ugly too

for the majority of my life i tried making myself more digestible. acceptable, likable, not come on too strong or too weak for certain people i thought really loved me. walking on eggshells. trying to win their approvals. but if they did love me, they wouldn’t try cutting the corners of my character and diluting who i am “to make me a better person.” people only do that when your character threatens them.

but these deep-seated, destructive feelings i hide have given me a breakthrough. “i will not water myself down to make me for digestible for you. you can choke.” you can choke and die, and i’ll watch. i will not try fitting myself into these microscopic boxes you hold and claim store all things perfect. i am much happier being flawed and imperfect than your slave or follower. i am euphoric for you to hate who i truly am than for you to love me for something i’m not. meanwhile i can continue hating you for pretending to be something you aren’t and who you really are. i could pray for it to change, i could supplicate and have faith but i don’t care anymore. you don’t appear in my duas any longer. and it’s fine by me if i don’t appear in yours; you’re only masquerading to be one of us anyway. disgust fills my veins— your self-righteous character thinking Islam needs to change, to reform, to adapt with this wretched “modern” world and your looking down on anyone who opposes or has a functioning brain stem. mean, you say? no dear. this is called being passionate. and i hate you with a passion. it’s almost art.

people think passion is always pretty, that it’s all rosy and dreamy and beguiling but the strongest kind of passion is ugly and unwanted. it’s rage fueled by years of wrongdoing, it’s grief, and it’s no wonder that these are what create the best works of any artist. it isn’t love— because, obviously, despite being the bearer of all my love you still turn out to be like this. it’s disgust, it’s when you realized you’ve been wronged and mistreated and the anger that rises with retaliation. so no, i don’t smile anymore when i see you. i don’t even talk to you let alone initiate small talk. i don’t give a damn about you. you have destroyed me too much to expect my heart to still beat at the sound of your name. all your promises are fake, and your words are wrapped with lies like tarpaulin. at least illusions are beautiful, they’re convincing and enjoyable but you’re none of these things in the slightest. people say truth is uglier but then there’s you, the ugliest, filthiest lie i’ve ever seen, i’ve ever interacted with and pretended like doesn’t break me.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

hosting a reading in this amazing record store (Bric A Brac Records in Chicago) on Saturday from 2p-5p! Stop by, hear some poems, grab some vinyl ❤️

w/ Parker Young, Daniel Borzutzky, Mallory Smart, Johannes Göransson, Nathan Hoks, Zachary Swezy, & Evan Williams

[feat. presses X-R-A-Y x Maudlin House x Future Tense Books x Coffee House Press x Black Ocean x Action Books x Tarpaulin Sky Press]

#poetry#reading#chicago#event#record store#bric-a-brac#music#saturday#free event#live event#fiction#indie press#diy

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your curiouscat is up in absolute flames rn so im popping by here to say that i love your writing and that you're so incredibly talented and i feel like doing a lil jig every time you post something new. Honestly, if you were to do a press conference for your works id be there front and center.

You also seem to have great taste in pretty much everything. You're really fucking cool and if I knew you irl Id wanna be your friend so bad.

the idiots hurling all that horrendous shit at you should step on a lego - i doubt they themselves know what they're talking about. Niche creators always get the worst of it and i really hate that they're going after you now for that tweet (that particular one too, like you've cooked worse ideas than that come on lol).

Anyways, I just wanted to let you know that you're amazing. It's the least I can do as a fan. Hope life has nothing but good stuff in store for you<333

Ps. Currently thinking about shoko in your tojisugushoko fic 'tarpaulin'. She's so sexy there

most of this has blown over now, but thanks man

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Merton: ‘I stayed in one of the world’s worst hotels in China’

The comedian recalls terrible hotels in China, mishaps with malaria tablets and why he’s happiest holidaying in the UK

Interview by Nick McGrath

From The Sunday Times, 22nd February 2023

Paul Merton, 65, first performed at the Comedy Store in 1982 and since 1990 has been a fixture on the BBC’s Have I Got News for You, which returns this spring for its 65th series. He lives in London with his third wife, Suki Webster, his co-star on Channel 5’s Motorhoming with Merton & Webster

My first holiday of any substance was to a holiday camp in Hemsby, on the edge of the Norfolk Broads. I was eight years old and I loved it. I loved the space to run around and the people drinking beer and watching the shows in the ballroom. It felt idyllic.

I visited Ireland a couple of years later and got a lot of attention from my mum’s relatives, which was great for my performer’s ego. We saw the Ring of Kerry and I was charmed by the locals’ love of words and storytelling.

I spent most of the Eighties living in a bedsit earning very little money, so the first time I travelled further afield was in 1987, when I went all the way to Australia, with a heavy cold, to visit my girlfriend at the time.

The cheapest route was London to Sydney, via Athens and Singapore. In Athens, the complimentary coach from the hotel to the airport was full of boy scouts from Liechtenstein, who were on their way to Sydney for an international scouting jamboree. Being stared at by three-dozen hostile Liechtensteiner boy scouts is an experience I won’t forget.

After a two-day delay in Singapore, I eventually got to Sydney on Christmas Day with horrible jet lag and an even heavier cold, sat down to Christmas lunch in 35C heat, then fell asleep for 16 hours. It felt like I’d been kicked in the head by a horse.

I’d only been earning £30 a gig, sometimes £10 even, so holidays were rare. But as my career took off, I travelled more — including to Kenya in 1990, where I had a terrible experience with anti-malarial drugs. Back then you had to take a weekly and daily pill and I had a severe reaction to the weekly pill, but it took a while to work out what the problem was.

Each Friday, first in Kenya and then back home in London, I’d take this pill then start to hallucinate. I got these paranoid thoughts, where I believed I was being followed by the Freemasons and could predict the next song on the radio. Which I couldn’t.

I then went to places like St Lucia, but felt uncomfortable driving around in a rented Land Rover that probably represented what some people there might earn in half a lifetime. I felt the same visiting Cape Town.

I was lucky enough to film a couple of travel documentary series in India and China — and had totally contrasting experiences. The poverty was dramatic in India, but the people were polite and proud and when I returned to film in Mumbai, Delhi and Calcutta, they found our earnestly awful attempts at Bollywood improv hilarious and gave us multiple standing ovations.

I wouldn’t return on holiday to China, as the state interference leaves a bit of a nasty taste, as does the spitting. You literally pull up at some traffic lights and a woman in a very nice car will open her window and spit on the road. Everybody does it. Maybe a popular Chinese film star was a passionate spitter. Or perhaps Chairman Mao decreed it a healthy habit. Filming while surrounded on all sides by armed soldiers wasn’t massively relaxing either.

I also stayed in one of the world’s worst hotels in China. The foyer had a tarpaulin covered in some unusually dark stains and the room had bits of wall missing and stank of urine. I moved to a nearby hotel which was equally basic but clean, at least, although the TV was puzzling. It had a single channel showing a military man laden with medals berating a group of people for hours on end while they looked shamefaced.

I’d love to visit New Zealand as everyone raves about it. Another place I definitely won’t go back to is Tahiti, which everyone imagines is a South Sea paradise, but for me, it wasn’t. The hotel I stayed in was completely overrun by cats.

These days I prefer British holidays, as airports in the 21st century leave you with a low level of anxiety. My wife and I now love travelling round Britain in our motorhome, which is basically a hotel room on wheels. If we all could drop the idea that we have to go on holiday somewhere that has guaranteed sun, holidaying in this country has a lot going for it.

Paul and Suki will be speaking at the Caravan, Camping & Motorhome Show at the NEC Birmingham, which runs from February 21 to 26 (ccmshow.co.uk)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

when our basement flooded several years ago we had to store all our stuff on the lawn, and we built this improvised shed mainly out of an old swingset, and covered the outside in tarps to make up for its limited soundness.

over the course of the ensuing winter one of the support struts wore through the tarp at one end, and speared out through it especially dramatically whenever the wind changed.

dad named the shed 'saint sebastian' and i think about it every time someone mentions him. that's what saint sebastian looks like to me.

modern art version: a punctured blue tarpaulin in the wind.

177K notes

·

View notes

Text

Industrial designs in Zurich West

The former industrial district of Kreis 5 has come alive with studios, ateliers and shops that are edgy enough to snap at the überstyled heels of London's Shoreditch district.

In just under a decade, Zurich has successfully shed its staid banking image to reveal a fresh and creative sensibility. Gone are the days when most visitors came only to check on their private bank accounts; today the city attracts a variety of world travellers, many lured by the city’s new retail offerings.

Related article: The stranger side of Switzerland

As they have in the past, the mainstream and upmarket shops that pepper the Altstadt (Old Town) still cater to a core of designer label-conscious locals and visitors (just take note of the number of Louis Vuitton bags carried along the main shopping street, the Bahnhofstrasse). But today, the transformed former industrial district of Kreis 5 in Zurich West has come alive with studios, ateliers and shops that are as trendy as those found in Berlin or Barcelona, and are edgy enough to snap at the überstyled heels of London's Shoreditch or New York's Meatpacking districts.

Despite being Switzerland's largest city, Zurich is compact and easy for shoppers to navigate, with an efficient tram, bus and boat service each offering their own glimpses of urban life. But often the best way to shop in Zurich is simply to walk. The area around Kreis 5 can be covered on foot in a day, and there are plenty of cafes, restaurants and bars in which to take a break (or as they say in Zurich, a “kleine Pause”) along the way.

Where to shop

Many of the stores and ateliers in Kreis 5 are run by independent designers, and thus are open later in the day and have sporadic hours throughout the week. Generally, Wednesdays, Thursday, Fridays and Saturday afternoons are the best times to find open shops – but this route will ensure you make the most of your time.

Start your shopping trip at the Freitag Flagship Store on Geroldstrasse, which opens at 11 am every weekday and 10 am on Saturdays. Like the rest of Zurich, it is closed on Sundays. The business, founded by two brothers, has become a symbol of Zurich's pared down industrial style. And the shop -- full of unique recycled tarpaulin bags in styles ranging from messengers to rucksacks and accessories like mobile phone and tablet covers -- is an architectural oddity made from five stacked freight containers.

Located on either side of Freitag are Bogen 33 and Walter, two vintage furniture stores selling design classics and quirky pieces from the 1950s onwards. Bogen 33, one of the first stores to open in Kreis 5, is a subterranean den with original, colourful pop-art designer chairs, tables, sofas and lights. Walter is a brighter ground level space that contains a number of solid wooden pieces like original sideboards and drinks cabinets that hark back to the Mad Men-era of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

After you have mentally redecorated your home, follow Geroldstrasse past the cluster of techno clubs to Im Viadukt, a group of newly renovated railway arches that now house about 30 independent shops, selling everything from clothing to kitchenware. Fashionslave, with its graphic design-inspired fittings, was one of the city’s first stores to cater to the fashion-conscious male, with personal grooming in one section of the shop and a stylist on hand to help you select the best European designer threads.

Im Viadukt’s food hall, Markthalle, sells fresh local ingredients and speciality foods from Switzerland and abroad. Take a break at Restaurant Markthalle, the food hall’s child-friendly lunch spot, which offers a seasonal menu of wholesome local organic produce, served in a rustic style (and one of the only venues in Zurich to serve all-day brunch on Sundays). Try the mountain lamb chops from the canton of Graubünden, or mixed sliced meat platters called Metzgerei. Vegetarians will have at least a couple of options on the menu, and many of the products are also available to buy from the adjacent food hall. Try to avoid the noon rush, when most Zürchers have lunch.

After lunch, head across the street to Heinrichstrasse 177, where you will find the charming compact and bijou studio of Anne-Martine Perriard, a women's wear designer who specialises in decadent silk and velvet clothes in muted tones. Her recent collection represents a contemporary take on 1940s French fashion, and in keeping with her preference for the most tactile of materials, she recently branched out into creating soft fabric and leather handbags and purses.

Next, turn left down Ottostrasse to Neugasse, where there is a Dada-esque quality about the next destination. Estelle Gassmann's witty artworks comprise of household objects, such as china serving platters or simple wire mesh waste paper bins, that are brought to life with sprawling alien-like tendrils made of plastic, porcelain, glass and clay, transforming them into surprisingly beautiful and quirky objets d'art.

From Neugasse, turn left onto Quellenstrasse to reach Josefstrasse, the main drag for most of the studios and boutiques in Kreis 5. Waldraud sells limited-edition contemporary furniture -- such as chairs, tables and lamps -- and fashion for women and men, all from designers as far afield as the Netherlands, Latvia and South Korea.

If you are in need of refreshment, then the cosy, wood-panelled confines of the nearby bar/restaurant Josef will cocoon you until you are ready to set forth again. The cocktails (alcoholic and non) are very tasty, and the vast gin selection is unsurpassed in Zurich. The restaurant is considered one of the best and most reasonably-priced in the city, as you can order tasting menus with two to five dishes per person, including dessert from 36 Swiss francs to 70 Swiss francs. The menu is unashamedly fleshy (highlights include pork belly, beef tartare or scallops) but there is always at least one vegetarian option, and the thyme polenta with chanterelle mushrooms is especially recommended.

Across Josefstrasse from Josef, Lesunja Goldschmiede sells bespoke gold jewellery made from new or old pieces, melted down to create a heady mix of delicate and bold new designs. She also takes your old gold as currency for new items. In a unique feature, you can learn how to make you and your partner's wedding rings in her workshops and one-to-one courses. Drop in, or contact her via the website to arrange a personal consultation visit, as schedules vary from course to course.

On the opposite side of the street, Manu Propria is a spectacles store founded by two opticians who design and construct their own frames. They have made a name for themselves as the trendiest place in Zurich to go for serious specs and beautiful sunglasses. Their frames come in all materials, from traditional bone to contemporary Perspex, and they can tailor your prescription to any of their styles. They also have a charming little spectacle museum in their shop with vintage examples from different eras.

Just two doors down is the award-winning Senior Design Factory. As the name suggests, this is a collaboration between Zurich's older citizens, who teach skills like knitting, crochet and candle and soap-making to young designers, resulting in exciting design fusions, like knitted lampshades and sculptural soaps. They also hold workshops for the public; current course schedules are available on their website.

At their cafe/restaurant project called the Senior Design Cafe, you can see some of their waresin action; huge embellished tea cosies adorn the tables while customers lean on the embroidered seat cushions and sit on trendy reupholstered chairs. The food is great too – try the fresh all-day Z'Morge (breakfast) platter with fresh pancakes and croissants, plus a choice of cooked local organic eggs, meats and sausages and rösti (a buttery Swiss hashed potato dish).

Shopping tips

Do not expect to find a bargain. There is no such thing as cheap in Zurich. Quality is king and Zurich's residents are often suspicious of reduced prices.

Your product is usually hand crafted by the designer from beginning to end (rare in these globalised times), so it is worth striking up a conversation with them to learn more about your purchase.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Day 16

drove with my dad to get the new sofa from the previous owner, got it onto the trailer and made sure to cover it properly with our tarpaulin as it was a rainy day.

Then drove to my place with a little rest from driving on the ferry. Put the sofa parts in my living room, then took out the two small sofas I've had for about 10 years and brought them to a friend who kindly allowed me to store them in their cellar.

Drove back to my place and assembled the sofa. We then went to the first christmas markeg of the season, had dinner and went to bed.

Time: ~ 9,5 h

Media: local Radio Stations (Driving route went through a neighbouring country for two hours)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The storage method of fertilizer produced by organic fertilizer equipment during the rainy season

In the rainy season, the fertilizer storage of organic fertilizer equipment needs to pay special attention to moisture-proof and moisture-proof to avoid fertilizer caking and nutrient loss. Here are some effective storage methods and suggestions:

1. Avoid stacking in the open field: In the rainy season, it is strictly prohibited to pile fertilizer in the open field. If temporary stacking is necessary, a high, dry and ventilated place should be selected, and rainproof measures such as covering tarpaulins should be taken.

2. Moisture-proof measures: the wooden pad should be used in the warehouse to be more than 0.3 meters above the ground to avoid the impact of moisture on the ground. At the same time, the warehouse should be kept well ventilated. When indoor temperatures and humidity are higher than outdoors, natural ventilation adjustments can be made by opening warehouse doors and Windows on sunny mornings and evenings.

3. Packaging and storage: Ensure that the fertilizer bag is well sealed, and choose a well-ventilated, watertight and clear room to store the fertilizer. Keep the storage room well ventilated, avoid clumping, and control the height of scattered and packed piles.

4. Safety measures: When storing organic fertilizers, it is necessary to avoid mixing different kinds of fertilizers to prevent chemical reactions from affecting the effect of fertilizers. At the same time, it is necessary to stay away from fire sources and high temperature areas to prevent fire and explosion accidents.

5. Regular inspection: In the storage process, the storage of organic fertilizers should be regularly checked, and the problematic fertilizers should be dealt with in time.

By taking these measures, it is possible to ensure the safe storage of fertilizer in the organic fertilizer production line during the rainy season and prevent fertilizer quality problems caused by wet weather.

0 notes

Text

Affordable Clear Tarpaulins UK – Protection Without Compromise

When it comes to safeguarding your belongings from the elements, clear tarpaulins offer a unique blend of visibility and protection. Whether you need to shield garden plants from unpredictable weather, cover outdoor furniture, or create temporary shelters, affordable clear tarpaulins provide an economical solution without sacrificing quality. In this blog, we will explore the advantages of using clear tarpaulins and why they are the perfect choice for your needs in the UK.

Why Choose Clear Tarpaulins?

Clear tarpaulins are made from durable, transparent materials such as polyethylene or PVC, allowing for maximum light transmission while offering superior protection against the elements. Here are several compelling reasons to consider clear tarpaulins for your projects:

1. Versatility for Various Applications

The adaptability of clear tarpaulins is one of its key benefits.

Greenhouses: Clear tarpaulins create a greenhouse effect by allowing sunlight to penetrate while protecting plants from harsh weather conditions, pests, and debris.

Construction Sites: Protect equipment, tools, and materials without obscuring visibility. Clear tarpaulins help workers monitor their surroundings while shielding valuable items from rain, snow, and dust.

Outdoor Events: Whether you’re hosting a garden party, wedding, or market stall, clear tarpaulins provide shelter while maintaining an open atmosphere, allowing guests to enjoy the outdoor ambiance.

Camping and Temporary Shelters: Clear tarpaulins make excellent ground sheets or temporary shelters, providing protection from rain while allowing natural light to brighten your space.

2. Durability and Weather Resistance

Affordable does not mean low quality. Many clear tarpaulins are designed to withstand the UK’s unpredictable weather. They are typically waterproof, UV-resistant, and reinforced at the edges, ensuring that they remain intact even in challenging conditions. This durability means you can invest in clear tarpaulins with confidence, knowing they will last for many seasons.

3. Cost-Effectiveness

One of the biggest advantages of using clear tarpaulins is their affordability. They provide a budget-friendly solution for protecting your belongings without compromising on quality. Because they are so versatile, you won’t need to purchase multiple types of covers for different applications. A single clear tarpaulin can serve various purposes, helping you save money in the long run.

4. Easy to Install and Maintain

Clear tarpaulins are generally lightweight and easy to handle, making them simple to install. Most products come with grommets or reinforced edges for easy tying down or securing in place. Additionally, they are easy to clean; a simple wipe-down with soap and water is often all that’s needed to keep them in good condition.

5. Eco-Friendly Options

In today’s environmentally conscious world, many manufacturers produce clear tarpaulins using recyclable materials. By choosing high-quality clear tarpaulins, you can protect your property while also making a more sustainable choice. Their durability means you won’t have to replace them as often, reducing waste and contributing to a greener planet.

Where to Buy Affordable Clear Tarpaulins in the UK

With the growing popularity of clear tarpaulins, various retailers in the UK offer a wide selection at competitive prices.

1. Online Retailers

Many online platforms specialize in Tarpaulins Sheets and outdoor equipment. Websites often have user reviews, detailed product descriptions, and competitive pricing, making it easy to compare options. Look for retailers that offer free shipping on larger orders to save even more.

2. Local Hardware Stores

Don’t overlook local hardware and garden supply stores. Many offer seasonal promotions or discounts on tarpaulins. Visiting a local store also allows you to inspect the quality of the product firsthand before making a purchase.

3. Wholesale Suppliers

If you need clear tarpaulins in bulk for a larger project, consider reaching out to wholesale suppliers. Buying in bulk can significantly reduce the cost per unit, providing a more affordable solution for larger-scale needs.

Conclusion

Affordable clear Tarpaulins Tents in the UK offer a reliable and economical way to protect your belongings without compromising quality. Their versatility, durability, and ease of use make them an excellent investment for a variety of applications, from gardening to outdoor events. By choosing clear tarpaulins, you can enjoy the benefits of protection and visibility, ensuring your projects remain safe and inviting.

0 notes