#THE MOST UNUSUAL TEEN-AGERS OF ALL TIME!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jack Kirby and Paul Reinman “The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants!” The X-Men #4 Title Splash Original Art (Marvel, 1964) Source

Colorist uncredited

#jack kirby#paul reinman#the x men#The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants#Title Splash#original art#THE MOST UNUSUAL TEEN-AGERS OF ALL TIME!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

X-Men 7 (Sept 1964)

Stan Lee/Jack Kirby.

HELL YEAH

"The most unusual teen-agers of all time" didn't really hold up as a tagline, but anyway. We're in issue 7 and the X-Men have, canonically, I think, seven villains - Magneto, the four members of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants who work for him, the Blob and the Vanisher. Six of them are coming back for this issue and they're being celebrated like we haven't seen them in years. This is funny but it's especially funny how much of a dunk on the Vanisher this is.

Anyway, the X-Men "graduate" in this issue, which doesn't involve them leaving school, nor does it involve the Professor stopping constantly testing them or anything, but Professor X leaves for a while and Cyclops officially becomes team leader and gets introduced to Cerebro, which looks amazing.

The Vanisher isn't even on Cerebro's list of KNOWN HOSTILE MUTANTS! Owned!

The gang goes to Greenwich Village for some downtime and we get Stan Lee's spoof version of beatniks. This is 1964 so this stuff is already kind of out of date (this is very much a bunch of late 50s gags) but I can't tell if that was part of the joke, or whether Stan Lee just didn't keep up with this stuff, or whether he assumed his imagined audience wouldn't be keeping up with this stuff. Or whether he just liked laughing at beatniks. Anyway, I dig it.

It gets weirder. I haven't even really talked about the stuff with Beast's giant feet but...there's a lot of foot stuff in these comics.

Oh right, the plot. Magneto tries to recruit the Blob, which almost works, until the X-Men show up to interrupt him at a missile base (as usual). The Blob inadvertently shields the X-Men from the blast of a missile, then concludes that he hates both sides and goes home, with a bit of humanisation. We stan the Blob. The end.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sofia Coppola’s Path to Filming Gilded Adolescence

There are few Hollywood families in which one famous director has spawned another. Coppola says, “It’s not easy for anyone in this business, even though it looks easy for me.”

By Rachel Syme January 22, 2024

From Marie Antoinette to Priscilla Presley, Coppola’s protagonists enjoy enormous privilege but little autonomy.Photograph by Thea Traff for The New Yorker

Wshen Eleanor Coppola went into labor with her third child, on May 14, 1971, at a hospital in Manhattan, her husband, the director Francis Ford Coppola, was on location in Harlem, shooting a scene for “The Godfather.” Hearing the news, he grabbed a camcorder from the set and raced over to capture the moment. “When they say, ‘It’s a girl,’ my dad gasps and nearly drops the camera,” Sofia Coppola told me recently, of her birth video. “My mom is there, just trying to focus.” The footage—which has been screened by the family multiple times over the years, and as part of a feminist art installation designed by Eleanor—was the first of many instances in which Sofia would be seen through her father’s lens. When she was just a few months old, Francis cast her in her first official film role, as the infant in the dénouement of “The Godfather,” in which Michael Corleone, the ascendant boss of the Corleone crime family, anoints the head of his newborn nephew as his associates murder rival gangsters one by one.

There are plenty of distinguished bloodlines in the history of Hollywood—the Selznicks and the Mayers, the Warners, the Hustons, the Bergman-Rossellinis, the Fondas—but very few, like the Coppolas, in which one famous director has spawned another. After an early life spent in front of the camera, Sofia Coppola made a career behind it, becoming one of the most influential and visually distinctive filmmakers of her generation, with eight features to her name. Her second, “Lost in Translation,” from 2003, earned her an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and a nomination for Best Director, making her the first American woman recognized in that category. Her career, of course, has been bolstered by an unusual wealth of resources. Francis’s company, American Zoetrope, has been a producer on all her movies. When she made her début, “The Virgin Suicides,” in 1999, she was able to cast an established star, Kathleen Turner, with whom she’d appeared as a teen-ager in her father’s movie “Peggy Sue Got Married.” She got permission to shoot “Somewhere,” her fourth film, inside the clubby Hollywood hotel the Chateau Marmont because in her youth she was a regular there, and even had a private key to the hotel pool. Still, no director can get a project green-lighted at a snap of the fingers, especially in today’s franchise-glutted Hollywood, and especially as a female director in an industry that remains dominated by men. Coppola is self-aware enough to know that it would be bad manners for someone in her position to complain. But she told me, “It’s not easy for anyone in this business, even though it looks easy for me.”

When we first met, in the fall of 2021, for breakfast near her home in the West Village, Coppola had spent the previous two years at work on her most ambitious venture to date, a miniseries, for Apple TV+, based on the Edith Wharton novel “The Custom of the Country,” from 1913. Coppola had adapted the book into five episodes and cast Florence Pugh in the lead role of Undine Spragg, a Midwestern arriviste on a desperate quest to infiltrate Gilded Age Manhattan society. Coppola, like Wharton, is known for her gimlet-eyed portrayals of a rarefied milieu, and for her insight into female characters who enjoy enormous privilege but little autonomy. “Marie Antoinette,” her most expensive movie, had a budget of forty million dollars, still modest by Hollywood standards; for “Custom,” she was planning for, as she put it, “five ‘Marie Antoinettes.’ ”

At breakfast, though, she told me, “Apple just pulled out. They pulled our funding.” Her voice was quiet, and her face—high cheekbones, Roman nose—was placid. “It’s a real drag,” she said. “I thought they had endless resources.” During the project’s development, she’d gone back and forth with executives (“mostly dudes”) on everything from the budget to the script. “They didn’t get the character of Undine,” she recalled. “She’s so ‘unlikable.’ But so is Tony Soprano!” She added, “It was like a relationship that you know you probably should’ve gotten out of a while ago.” (Apple did not respond to request for comment.)

Coppola grew up watching Francis do battle with movie studios. The success of the “Godfather” films hardly assured him funding equal to his ambitions, and he often went to harrowing lengths to get his projects made independently, driving himself to the brink of bankruptcy or nervous breakdown. “Hearts of Darkness,” a documentary co-directed by Eleanor about the notoriously tortured production of “Apocalypse Now,” is subtitled, only a bit hyperbolically, “A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse.” (At the age of eighty-four, Francis is financing a new film, “Megalopolis,” with a hundred and twenty million dollars of his own money, freed up by the sale of a portion of the family’s wine business.) Coppola absorbed from her father the ethos that it was never worth it to cave to the creative demands of executives. In 2014, she agreed to make a live-action version of “The Little Mermaid” for Universal Studios, but amid disputes during development (including, she said at the time, an executive asking her, “What’s gonna get the thirty-five-year-old man in the audience?”) she walked away from the job. “I don’t actually want a hundred million dollars to make a movie,” she told me, of studio deals with strings attached. “I learned it’s better to do your own thing.” She refuses to take on projects unless she is guaranteed the right to choose her creative team and control the final cut.

In January of 2022, after trying in vain to secure alternative funding for “Custom,” Coppola moved on to a new project, an independent film adapted from Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir, “Elvis and Me.” Presley’s relationship with Elvis began when she was just fourteen. Like Marie Antoinette, she found herself unhappily married to a King. Paging through the book while in bed with a case of covid, Coppola had begun to see the picture unfolding in her mind. “I just thought about her sitting on that shag carpet all day,” she recalled. She wrote a draft of the script quickly and told her longtime producer, Youree Henley, that she wanted to be done shooting by the end of the year. She was undeterred by the coming release of Baz Luhrmann’s eighty-five-million-dollar film “Elvis,” which was due out in a few months. A rhinestoned frenzy of a bio-pic, Luhrmann’s movie portrayed Priscilla as a marginal character and a happy helpmate. Coppola called Presley and said, “That’s not how I see you at all,” and after hearing Coppola’s vision Presley signed on as a producer.

“Marie Antoinette” was filmed inside the real Versailles, a cinematic coup. For “Priscilla,” the Elvis Presley estate, wary of a film told from Priscilla’s perspective, denied Coppola access to Graceland. Coppola’s production team instead constructed the façade and the interiors of Elvis’s Memphis mansion on a soundstage outside Toronto. I visited one afternoon in November of 2022, as the shoot was under way. Off set, Coppola, who is fifty-two, dresses with understated elegance—Chanel slingbacks, collared blouses. Now she was wearing her only slightly less polished “set uniform,” gray New Balances and a black Carhartt fleece over a Charvet button-down. She led me through the hangarlike space and into the ersatz Presley home. The entrance was flanked by two large lion statues. In the gaudy living room, she pointed to a floral arrangement. “Those are real orchids,” she said. “It surprised me, with our budget. How extravagant.”

Coppola’s team had budgeted for forty days of shooting, already a squeeze, but at the last minute a piece of financing had fallen through, and she’d had to slash the story to be filmed in just a month, for less than twenty million dollars. Much of the movie is set in the Memphis summer, but they were filming as winter approached, which was cheaper, so Coppola had to coach her cast, shivering through outdoor scenes in their bathing suits, to “act warm.” Instead of filming two long shots she’d wanted in Los Angeles, of Priscilla driving a convertible down a palm-lined street and swan-diving into a pool, Coppola saved money by borrowing footage from a Cartier commercial she’d shot in 2018, with an actress who kind of looks like “Priscilla” ’s lead, Cailee Spaeny, at least from behind.

Whether set in a luxury hotel in Tokyo, like “Lost in Translation,” or in suburban Michigan, like “The Virgin Suicides,” Coppola’s films are sumptuous but also slightly clinical. One of her œuvre’s visual hallmarks is a protagonist gazing out a window, sealed off from the world beyond. “You know I can’t resist a trapped woman,” she said. Yet, even when her female characters are confined, they achieve a degree of self-definition through adventures in style. No filmmaker has so astutely depicted the cloistered atmosphere of teen-age girlhood or the expressive power of its trappings. She is a master of the messy-bedroom mise en scène: piles of clothing and impractical shoes, poster-plastered walls, vanities cluttered with perfume bottles and porcelain figurines. The director Chloé Zhao, who won Best Director at the 2021 Oscars for her film “Nomadland,” told me that she admires Coppola for “world-building that isn’t just based on facts but on emotions.” She added, “There’s a receptivity to her work. To have a commitment to that kind of femininity is hard.” The director Jane Campion, who counts “The Virgin Suicides” among her favorite films, told me that Coppola’s light touch with actors and her attention to surfaces can be deceptive. “Her work is very powerful to me, because it’s got deep roots,” she said. But Coppola’s films have sometimes struck critics as longer on style than on substance, and too close to the privileges they depict to effectively critique them. A few months ago, Coppola sent me an e-mail, unprompted, in which she took issue with a notion that has resurfaced throughout her twenty-five-year career: “I don’t understand why looking at superficiality makes you superficial?!”

Coppola told me she could see herself, in an alternative life, as the editor of a magazine, “like Diana Vreeland,” who commanded Vogue in the sixties. Coppola is an avid curator of images and looks; Campion recalled that once, when they were both judges at Cannes, Coppola offered to help style her, and the next day two huge boxes from the luxury fashion brand Celine arrived at Campion’s hotel. Coppola begins every film project by gathering visual inspiration. In her makeshift office on the soundstage, she had covered a large bulletin board with imagery including the Presleys’ wedding photographs, a glamour shot of Priscilla as a teen-ager, and several William Eggleston pictures of an empty Graceland. There is a famous Bruce Weber photo of Coppola’s stylishly bestrewn home office at the time of “The Virgin Suicides,” and this workspace bore some resemblance. On her desk were pink Post-it notes, a Fujifilm Instax camera, and a half-burned Diptyque candle; on the floor lay wine bottles from the Coppola vineyard (which also makes a “Sofia” champagne that comes in tiny pink cans with individual straws). The director Quentin Tarantino, whom Coppola dated in the two-thousands, recalled her once showing him the look book for “Marie Antoinette.” “It was exquisitely put together, yet you could still tell it was handmade,” he said, “by the loving hands of a fine artist.” He went on, “She had a page of donuts with a pink glaze. I asked her, ‘What’s with the donuts?’ She said, ‘I like that shade of pink, and I want her sofa to have that quality.’ And when I saw the film, sure enough, I wanted to eat the goddamn furniture.”

When conceiving a film about Priscilla Presley’s unhappy marriage to Elvis, Coppola says, “I just thought about her sitting on that shag carpet all day.”Photograph by Kate Cunningham / Courtesy MACK

Coppola led me down a hallway to a room where the film’s costume designer, Stacey Battat, was floofing out Priscilla’s wedding gown, which Coppola had asked the fashion house Chanel to design for the movie as a favor. The dress, with a high-necked lacy bib, closely resembles the original, but among Coppola’s assets as a filmmaker is a preternatural aesthetic assurance, even when it comes to taking liberties with her source material. “I’ve always known what I like,” she told me. The opening shot of the film is a closeup of Priscilla’s feet stepping across a fuzzy expanse of shag carpet, which she made a rosy hue, though in the real Graceland there was no such rug. “In my mind, it was pink,” she told me. She hadn’t visited Graceland to prepare for the film, but a friend had taken a tour and had sent her a picture of poodle-print wallpaper. Coppola decided to re-create it for a shot in which Priscilla languishes in the tub, waiting for Elvis to return.

“It probably wasn’t in a bathroom in Graceland,” Coppola said. “But whatever.”

The lighting on set was dim. A playlist of songs, selected daily by Coppola to “set a vibe,” played over the sound system—Curtis Mayfield, Aretha Franklin, and the French indie-rock band Phoenix, which is fronted by Coppola’s husband, Thomas Mars, who is also a music supervisor for her films. In one corner, crew members were playing pickleball on a court that Coppola had insisted on installing during the first week of shooting. She had played in the crew’s tournament, and her team, the Smashers, won. “Pickleball paddles are so ugly,” she commented. “Maybe I’ll design a new line of them.”

Coppola told me that she learned from her father how to create “a warm set,” and borrowed from him a ritual he picked up in drama school: to kick off every production, stand with the cast and crew in a circle, hold hands, and recite the nonsense word “puwaba” three times. But the elder Coppola has what Eleanor, who has been married to him for sixty years, described to me as “an Italian approach—very theatrical, throwing stuff up in the air and screaming.” Sofia said that she finds such flourishes “so unnecessary.” The protagonists in her films tend to observe more than they speak, and Sofia comports herself in much the same way. The people who’ve worked with her, however, describe an impressive resolve beneath the diffidence. The actress Elle Fanning, who starred in “Somewhere” and “The Beguiled,” told me, “She doesn’t freak out, ever. She’s not going to scream at you across the room. But she’s unwavering.” Bill Murray, a star of “Lost in Translation” and “On the Rocks,” gave Coppola the nickname “the velvet hammer,” for her subtle stubbornness about getting her way.

Henley, the producer, who was sitting in a director’s chair near a video monitor, recalled a day when he and Coppola were scouting ice rinks for “Somewhere.” Coppola said of one, “This is great—um, where should we have lunch?” Afterward, Henley mentioned a few more possible rinks to visit, and Coppola looked puzzled; she’d already chosen. Henley told me, “I wasn’t able to read her softness as well as I can now.”

Coppola and her team were rehearsing a scene in the Presleys’ bedroom, where a large mirror hung behind the bed. Jacob Elordi, the actor playing Elvis, took his place on the King-size mattress, his six-foot-five frame nearly dangling over the edge. Spaeny, who was twenty-four but petite enough to pass for a teen-ager, hovered in the doorframe. The scene takes place shortly after Priscilla’s arrival at Graceland. She has gone shopping and bought a dress, but returns it after Elvis deems it unflattering. “Once again I’d compromised my own taste,” Presley writes of that moment in the memoir, which in Coppola’s world is the worst kind of fate.

Kathleen Turner told me, of working with Coppola on “The Virgin Suicides,” “She would never tell an actor what she wanted specifically, and, boy, that can be very tough.” She added, “Francis is a bulldozer, a very good bulldozer who knows what he wants. Sofia lets you do, and then lets you know if that’s what she wanted.” Elordi, who is twenty-six, told me he interpreted Coppola’s lack of instruction as a sign of trust. She cast him after meeting him just once. “Sofia never checked in before we were filming. She never texted or called about the voice or the look or the walk,” he said. When he arrived on set, excited to show Coppola the Elvis accent he’d been working on for months, she said, “Wow, you really look and talk like him,” and left it at that.

Coppola called, “Action!,” and Elordi looked at Spaeny: “What is that dress? It does nothin’ for your figure.” He glanced toward Coppola, who was standing with her cinematographer. “Was that all right, Sofia?” he drawled, remaining in character. “Should I be laughing at her? I don’t want to be too dramatic.”

“It was not too much,” Coppola replied. She paused and placed her hand on her chin. “It might have been a little Elvis-y.”

Francis’s life as a director was peripatetic, and he did not believe in leaving his family behind for more than ten days at a time. So the rest of the nuclear unit—Eleanor, Sofia, and her brothers, Roman and Gian-Carlo, or Gio—lived away from their home in Northern California for months, and sometimes years. One of Sofia’s first memories is of riding in a helicopter in the Philippines during the filming of “Apocalypse Now.” During the making of “One from the Heart,” when she was in the fourth and fifth grade, they relocated to L.A. After that, for “The Outsiders” and “Rumble Fish,” they went to Tulsa, Oklahoma. “We were circus people, basically,” she said. “I kind of mark my childhood by the movies.”

Coppola never excelled academically, in part because of all the moving around. She left one school before learning multiplication, and by the time she enrolled in a new one she’d missed the same unit. Coppola recalled, “I never really learned math, and I’m what they call a ‘challenged’ reader.” Anahid Nazarian, a researcher and producer who has worked with Francis for forty years, remembers a time when Coppola didn’t turn in a paper: “Her teacher said she had the best excuse, which was ‘I left it on the plane coming back from the Oscars.’ ” On matters of taste, though, Coppola was precociously fluent. She gave herself the nickname Domino and insisted that she be credited as such in several of her father’s pictures. While on the set of “One from the Heart,” she created her own publication, The Dingbat News, to distribute among the cast and crew. She collected photography and decorated her walls with pictures from foreign magazines. “I was the only girl in Napa Valley with a subscription to French Vogue,” she said. Francis described her as having “very, very big opinions” even as a little girl, adding, “It was never difficult to know what she preferred and what she didn’t prefer.” Francis’s best-known films took place in hypermasculine precincts—the Army, the Mob. Coppola was drawn to high-femme self-expression. At her parents’ dinner parties, she was always more interested in the “wives and girlfriends,” she said. “They had the best Bakelite jewelry.”

Francis recalled that he and Eleanor maintained a home base outside of Hollywood to create a semblance of normality for the kids. Nonetheless, many of the stories Coppola told me about her childhood took place in the world of famous adults: Richard Gere, a star of Francis’s “The Cotton Club,” swam in the family’s pool; George Lucas was “Uncle George”; Anjelica Huston assured Coppola that she would grow into her nose. One afternoon last year, during a visit to an L.A. bookstore, Coppola showed me a volume called “Height of Fashion,” a collection of notable people’s most stylish snapshots. Coppola had submitted a picture of herself at fourteen—gawky and beaming, with an asymmetrical haircut—sitting at the tony Parisian restaurant Davé next to the late fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent. “He was a friend of a friend of my parents,” she said.

“Marie Antoinette” sharply divided critics. Some dismissed it as an ahistorical powder puff. Others thought it was a masterpiece.Photograph by Andrew Durham / Courtesy MACK

There is an old-world flavor to the Coppolas’ relationship to the family business: just as cobblers beget cobblers, movie people beget movie people. Roman, Sofia’s brother and frequent collaborator, is a filmmaker and has written screenplays with Wes Anderson. Talia Shire, who starred in the “Godfather” movies and the “Rocky” franchise, is her aunt. Her niece Gia has directed two features. Her first cousins include the actors Jason Schwartzman, whom she cast as a dweeby Louis XVI in “Marie Antoinette,” and Nicolas Cage. Other Coppolas coach actors, write screenplays, make music, and produce or distribute films. Sofia ascribes the field’s popularity within the family to Francis’s contagious passion. “My father is just so into filmmaking that he thinks everyone should be doing it,” she said. Even Francis’s father, a composer, ended up working on scores for his films, winning an Oscar (with Nino Rota) for “The Godfather: Part II.”

One member of the family who struggled to find her way in the business was Eleanor. In “Notes,” the first of two memoirs she has written, she described meeting Francis on the set of his début feature, the horror film “Dementia 13,” in 1962. He was the director, she was the assistant art director, and she thought that they might work on films together for years to come. Instead, within a few months she found out she was pregnant with Gio. She and Francis were married the following weekend, and Francis, as Eleanor put it to me, “made it very clear that my role was to be the wife and the mother.” She writes in “Notes” of a feeling of living in waiting—“waiting for Francis to get a chance to direct . . . waiting to go on location, waiting to go home.” (“At that point, I didn’t even know I could have a career, much less whether my wife would,” Francis said, by e-mail, adding, “I knew she was creative and from day one I always provided full time childcare and a studio for Ellie’s artwork.”) Sofia described a time when her mother visited the set of “Priscilla” and observed a scene in which Elvis is preparing to go on tour, while Priscilla will stay with their daughter, Lisa Marie. Eleanor told her, “I’ve been there.” Eleanor recalled to me, “When Elvis said to Priscilla, ‘You have everything you need to be happy,’ that’s exactly what I was feeling at the time. I went to the psychiatrist and said, ‘Why am I unhappy?’ Not one single person said to me, ‘You are a creative person.’ ”

With his daughter, however, Francis made a point of offering creative encouragement, including by exposing her, along with her brothers, to the technical aspects of filmmaking. “There’s a traditional Italian thing with women, but I wasn’t raised like that,” Coppola said. “I was raised the same as the boys.” She and her mother didn’t discuss the gap in their experiences at the time, and Coppola isn’t inclined to analyze the themes that she explores in her work. Roman told me, “I’ve never heard Sofia say, ‘I want to show this isolation through this thing.’ ” Francis has always advised her that filmmaking should be close to the bone—as he told me, “the more personal, the better.” But, when I asked about the personal element of her movies, Coppola often fell back on abstractions or let her sentences trail off mid-thought. (Other writers have speculated about whether her style of communication is cannily evasive or simply a natural product of valuing the visual over the verbal. “I think sometimes she gives people enough rope to hang themselves with just by not responding,” Fiona Handyside, a British film scholar and the author of “Sofia Coppola: Cinema of Girlhood,” has said.) When I told Coppola about the feelings of stuckness that Eleanor had shared with me, and that seemed to percolate through Coppola’s films, she said, “I think so many people can relate to that, especially women.” Then she added, of her mom, “I’m sure seeing my first impression of womanhood as a woman who felt trapped, and her sadness, is related to the women in my films, more than to a side of myself.”

One morning last July, I met Coppola in the lobby of the Ritz Paris, where she was staying before a meeting about an upcoming line of garments she’d designed for the Scottish knitwear brand Barrie, which is owned by Chanel. (She told me that her dad, who has earned much of his fortune through wine and hotels, “taught us how to make money doing other things, so that you don’t have to count on the movies for that.”) Coppola and Mars spend part of the year in Paris, and she could have just stayed in her apartment across town. But the Ritz was closer to Barrie’s offices, near the Place Vendôme, and she relished the opportunity to hole up there by herself. “Lost in Translation” and “Somewhere” portray hotels as sites of both listless suspension and electric potential. “I love an in-between place,” she said.

When Coppola was fifteen, in 1986, Francis arranged a summer internship for her at Chanel. A month before she was supposed to leave for Paris, Gio, her oldest brother, was killed in an accident. He was twenty-two and had been assisting his father on the film “Gardens of Stone,” set at Arlington Cemetery, and on a day off had gone boating with one of the film’s co-stars, Griffin O’Neal. While driving between two other boats, O’Neal drove into a towline that struck Gio. (O’Neal was replaced in the film and later charged with manslaughter, but was ultimately acquitted.) Francis’s producers offered to shut down the film shoot, but he wanted to press on. In her memoirs, Eleanor recalls his hope that keeping busy “would prevent the torturous reality of Gio’s loss from pervading every moment.” Roman, then a film student at N.Y.U., cancelled his summer plans to step into Gio’s job on the film, but Coppola’s parents decided that she should still go abroad. Eleanor told me, “She was right at that age where she was trying to pull away from me, and so I thought she needed to get away from home, and all the things that surrounded the aftermath, and, frankly, me as a mom.”

There is an old-world flavor to the Coppolas’ relationship to the family business: just as cobblers beget cobblers, movie people beget movie people. Roman, Sofia’s brother and frequent collaborator, is a filmmaker and has written screenplays with Wes Anderson. Talia Shire, who starred in the “Godfather” movies and the “Rocky” franchise, is her aunt. Her niece Gia has directed two features. Her first cousins include the actors Jason Schwartzman, whom she cast as a dweeby Louis XVI in “Marie Antoinette,” and Nicolas Cage. Other Coppolas coach actors, write screenplays, make music, and produce or distribute films. Sofia ascribes the field’s popularity within the family to Francis’s contagious passion. “My father is just so into filmmaking that he thinks everyone should be doing it,” she said. Even Francis’s father, a composer, ended up working on scores for his films, winning an Oscar (with Nino Rota) for “The Godfather: Part II.”

One member of the family who struggled to find her way in the business was Eleanor. In “Notes,” the first of two memoirs she has written, she described meeting Francis on the set of his début feature, the horror film “Dementia 13,” in 1962. He was the director, she was the assistant art director, and she thought that they might work on films together for years to come. Instead, within a few months she found out she was pregnant with Gio. She and Francis were married the following weekend, and Francis, as Eleanor put it to me, “made it very clear that my role was to be the wife and the mother.” She writes in “Notes” of a feeling of living in waiting—“waiting for Francis to get a chance to direct . . . waiting to go on location, waiting to go home.” (“At that point, I didn’t even know I could have a career, much less whether my wife would,” Francis said, by e-mail, adding, “I knew she was creative and from day one I always provided full time childcare and a studio for Ellie’s artwork.”) Sofia described a time when her mother visited the set of “Priscilla” and observed a scene in which Elvis is preparing to go on tour, while Priscilla will stay with their daughter, Lisa Marie. Eleanor told her, “I’ve been there.” Eleanor recalled to me, “When Elvis said to Priscilla, ‘You have everything you need to be happy,’ that’s exactly what I was feeling at the time. I went to the psychiatrist and said, ‘Why am I unhappy?’ Not one single person said to me, ‘You are a creative person.’ ”

With his daughter, however, Francis made a point of offering creative encouragement, including by exposing her, along with her brothers, to the technical aspects of filmmaking. “There’s a traditional Italian thing with women, but I wasn’t raised like that,” Coppola said. “I was raised the same as the boys.” She and her mother didn’t discuss the gap in their experiences at the time, and Coppola isn’t inclined to analyze the themes that she explores in her work. Roman told me, “I’ve never heard Sofia say, ‘I want to show this isolation through this thing.’ ” Francis has always advised her that filmmaking should be close to the bone—as he told me, “the more personal, the better.” But, when I asked about the personal element of her movies, Coppola often fell back on abstractions or let her sentences trail off mid-thought. (Other writers have speculated about whether her style of communication is cannily evasive or simply a natural product of valuing the visual over the verbal. “I think sometimes she gives people enough rope to hang themselves with just by not responding,” Fiona Handyside, a British film scholar and the author of “Sofia Coppola: Cinema of Girlhood,” has said.) When I told Coppola about the feelings of stuckness that Eleanor had shared with me, and that seemed to percolate through Coppola’s films, she said, “I think so many people can relate to that, especially women.” Then she added, of her mom, “I’m sure seeing my first impression of womanhood as a woman who felt trapped, and her sadness, is related to the women in my films, more than to a side of myself.”

One morning last July, I met Coppola in the lobby of the Ritz Paris, where she was staying before a meeting about an upcoming line of garments she’d designed for the Scottish knitwear brand Barrie, which is owned by Chanel. (She told me that her dad, who has earned much of his fortune through wine and hotels, “taught us how to make money doing other things, so that you don’t have to count on the movies for that.”) Coppola and Mars spend part of the year in Paris, and she could have just stayed in her apartment across town. But the Ritz was closer to Barrie’s offices, near the Place Vendôme, and she relished the opportunity to hole up there by herself. “Lost in Translation” and “Somewhere” portray hotels as sites of both listless suspension and electric potential. “I love an in-between place,” she said.

When Coppola was fifteen, in 1986, Francis arranged a summer internship for her at Chanel. A month before she was supposed to leave for Paris, Gio, her oldest brother, was killed in an accident. He was twenty-two and had been assisting his father on the film “Gardens of Stone,” set at Arlington Cemetery, and on a day off had gone boating with one of the film’s co-stars, Griffin O’Neal. While driving between two other boats, O’Neal drove into a towline that struck Gio. (O’Neal was replaced in the film and later charged with manslaughter, but was ultimately acquitted.) Francis’s producers offered to shut down the film shoot, but he wanted to press on. In her memoirs, Eleanor recalls his hope that keeping busy “would prevent the torturous reality of Gio’s loss from pervading every moment.” Roman, then a film student at N.Y.U., cancelled his summer plans to step into Gio’s job on the film, but Coppola’s parents decided that she should still go abroad. Eleanor told me, “She was right at that age where she was trying to pull away from me, and so I thought she needed to get away from home, and all the things that surrounded the aftermath, and, frankly, me as a mom.”

Coppola’s book “Archive” includes behind-the-scenes photos from her films, including this one of her with her first daughter, Romy, on the set of “Somewhere.”Photograph by Andrew Durham / Courtesy MACK

When the film came out, Eleanor’s fears proved founded. In 1991, Coppola won two Razzie awards, for Worst Supporting Actress and Worst New Star. Entertainment Weekly ran a cover story with the teaser line “Is she terrific, or so terrible she wrecked her dad’s new epic?” Whatever one thought of Coppola’s performance (Pauline Kael appreciated her “unusual presence”), the fracas lent a metatextual poignancy to Coppola’s final moment in the film, when, just before she crumples on the theatre steps, Mary looks at Michael and utters a disbelieving “Dad?” Francis later admitted to the Times, “The daughter took the bullet for Michael Corleone—my daughter took the bullet for me.” Sofia absorbed the bad press with characteristic sangfroid. “It was embarrassing to be so publicly criticized for ruining my dad’s movie,” she said, but “I wasn’t devastated, because acting wasn’t my dream.” She went on, “I think that the experience helped me as a director. I know how vulnerable it feels to be in front of a camera.” Kirsten Dunst, who starred in “The Virgin Suicides” at the age of sixteen, and later in “Marie Antoinette” and “The Beguiled,” recalled, of first working with Coppola, “I remember her telling me how much she loved my teeth. I thought I had crooked teeth, but she was, like, ‘They are so cute.’ She gave me confidence about things I didn’t necessarily have, and I’ve carried that with me.”

In the following years, Coppola had the kind of aimless early adulthood particular to the offspring of the Hollywood élite. She enrolled in ArtCenter College of Design to study oil painting but dropped out after a teacher told her she was “no painter.” She audited a course with the photographer Paul Jasmin, whom Coppola cites as “the first person outside my family who told me I had any taste.” She became something of an L.A. It Girl, making cameos in music videos and being featured in newspaper style sections. In interviews, she made blithe pronouncements. (Likes: Karl Lagerfeld, hot rods. Dislikes: bras, Twelve Steppers.) At twenty-three, she bought herself a black Cadillac Seville and dubbed it her “Mafia princess car.” She spent a lot of time floating around the pool at the Chateau Marmont, making use of her private key. In 1994, she launched a fashion line called Milkfed, which produced ironic items like a baby tee printed with the phrase “I ♥ Booze.” That same year, she and her friend Zoe Cassavetes, the daughter of the director John Cassavetes and the actress Gena Rowlands, hosted a Comedy Central series called “Hi Octane.” (When I asked Coppola if she has any friends who don’t have celebrities for parents, she said, somewhat vaguely, “It’s definitely not, like, a through line with all of my friendships,” but acknowledged a special affinity for others who have “big macho powerful artist dads.”) The series, in which the pair undertook stunty adventures and interviewed their famous acquaintances, was cancelled after a few episodes. Francis recalled that Sofia once asked him, “Dad, am I going to be a dilettante forever?”

A breakthrough came when Coppola wrote a short film, called “Lick the Star,” about a clique of teen-age girls who revere, and then violently ostracize, their queen bee. Her cast featured some of her father’s associates, including Peter Bogdanovich as a school principal. The finished film, released in 1998, runs only thirteen minutes and is shot in black-and-white, but it contains the seeds of Coppola’s lush cinematic vocabulary. She told me, “I knew a little bit about photography, a little bit about clothing design, and a little bit about music. I was annoyed that I could never pick one thing. And then, when I made my short film, I realized it was a way to work with all of it.”

In New York, Coppola lives with Mars and their two teen-age daughters in a red brick town house whose narrow façade makes it look deceptively humble from the outside. One morning last March, she met me at the entranceway with the family’s golden retriever, Gnocchi, and guided me into a wide, white-walled living room. Coppola’s home décor, like her fashion sense, is classic with a whimsical feminine touch. The mantel over a gray marble fireplace held a large porcelain chinoiserie vase filled with an architectural array of pink roses and anemones. (They were high-end fakes.) A floor-to-ceiling bookcase was organized into sections on fashion, New York, photography, and French history. In between books she had wedged framed art works, including a drawing made by the director Mike Mills for the poster of “The Virgin Suicides” and a Polaroid of Princess Caroline of Hanover taken by Andy Warhol.

Coppola told me that her least favorite film to make was “The Bling Ring,” her fifth feature, because the world in which it’s set was out of synch with her own sense of taste. The movie—based on the true story of a group of L.A. high schoolers who robbed the homes of the rich and famous—was shot partly inside Paris Hilton’s mansion, where the camera gawks at throw pillows emblazoned with images of Hilton’s face and a “night-club room” equipped with a dancer’s pole. The film is a note-perfect millennial period piece, channelling the haywire intersection of celebrity worship and consumerism at the dawn of social media. But Coppola said, of its milieu of Ugg-boot-wearing teens and the reality stars they worship, “I wouldn’t call it hideous—that sounds snobby—but a big part of my motivation is making beauty.” To her chagrin, “The Bling Ring” is her daughters’ favorite among her movies. “They think it’s really glamorous and cool,” she said, then added, with a shudder, “They’ve started asking me for boot-cut jeans.”

She did not show me the girls’ bedrooms, but she later told me that she’s begun photographing their messes for posterity. “It’s like set dressing for one of my movies,” she said. The girls are forbidden to have public social-media accounts until they’re eighteen, but Romy, the older child, had a rogue viral moment last year, when—sounding, many observers noted, a bit like one of Coppola’s restless protagonists—she posted a plucky TikTok video saying that she’d been grounded for attempting to charter a helicopter with her dad’s credit card “because I wanted to have dinner with my camp friend.” Coppola, who values privacy and the mystery it can afford, called the video “the best way to rebel against me.” (She seemed excited, though, to confirm that Romy had filmed a small speaking role in Francis’s upcoming movie.)

Coppola considers “Lost in Translation,” her second film, to be her most personal.Photograph courtesy Sofia Coppola / Courtesy MACK

Coppola had set out scalloped shortbread cookies on a dainty plate (“I love Italian fancy-lady dishes”) and a floppy stack of paper, the manuscript of a coffee-table book, “Sofia Coppola Archive,” which she released last fall. The finished volume, as thick and pink as a slice of princess cake, is a scrapbook of Coppola’s career, with short, elliptical introductions to each film followed by a cascade of Polaroids, hand-written notes, contact sheets, script marginalia, costume sketches, and other ephemera.

The first chapter opens with a behind-the-scenes image of Dunst smiling in the grass of a football field. Coppola was in her early twenties when she read Jeffrey Eugenides’s novel “The Virgin Suicides,” from 1993, about five adolescent sisters in nineteen-seventies Michigan, who languish under the strictures of their ultraconservative parents and all die by suicide in a single year. Coppola said that when she read the book she thought, I hope whoever makes this into a movie doesn’t ruin it. Then she realized that maybe she could be the one to do it.

Coppola had started writing the script before she learned that a pair of producers had already bought the rights to the book and were working with a male writer-director. “I could hear my dad saying, ‘Don’t ever try to adapt something you don’t have the rights to,’ ” she recalled. “He told me to move on to something else.” Instead, Coppola sent her script to the producers and asked them to consider her for the directing job should the current arrangement fall through. A year later, she got the call. “I was young and naïve and didn’t really know what I was getting into,” she told me, “but I was, like, ‘Shit, O.K., now I have to figure it out.’ ”

“Virgin,” filmed over a month in the summer of 1998, for a budget of four million dollars, was a remarkably assured début, from its opening shot: Dunst lingering on the hot street eating a cherry Popsicle, like a latter-day Lolita, as the synthy sounds of the band Air kick in. From there the film unfolds at an unhurried pace. The sisters’ sadness is scarcely externalized, but the creeping ooze of their despair pervades every frame, including a striking shot of a wooden crucifix with a pink lacy bra slung across it to dry. Eugenides formulated the story as a hazy memory, narrated by a chorus of neighborhood boys who idolize the sisters but know nothing of their inner lives. Coppola’s script used a single narrator and allowed the camera to peek into the private spaces where the boys could never go. “Archive” reproduces an e-mail she received from Eugenides in 1998, expressing concerns that the script lacked “the necessary support around that story, which of course means the boys, the passage of time, the disjunctive narrative, and the right tone.” (She also includes a recent message that Eugenides wrote in response to her request to print the letter, in which he says, “What a whiny little bitch I was in those days.”) The film premièred at the Sundance Film Festival to critical acclaim, but, according to Coppola, her American distributor, Paramount Classics, did little to promote it. “They thought teen-age girls were going to kill themselves if they saw it,” she said, adding, “It barely came out here.”

Coppola told me that every film she makes is a reaction to the one before. After “Virgin,” she wanted to work from an original story. She considers “Lost in Translation,” her next film, to be her most personal. She chose Japan as its setting based on trips she’d taken to promote her Milkfed line, and came up with the story of a twentysomething American woman, Charlotte, who bonds with a famous older actor named Bob at the Park Hyatt Tokyo. She wrote the script with Bill Murray in mind as Bob, then spent a year trying to track him down. (The actress Rashida Jones, a friend and collaborator of Coppola’s, recalled, “She had an assistant whose job it was to hold her phone and tell her if Bill Murray called.”) Charlotte, played by Scarlett Johansson, is smart but lacking direction. She tells Bob, “I tried taking pictures, but they’re so mediocre.” She is married to a hot-shot music photographer (Giovanni Ribisi), and she sits bored at the hotel bar as he schmoozes with Hollywood types.

At the time, Coppola was married to the director Spike Jonze, whom she’d met in the early nineties through her friends Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore, of the band Sonic Youth. But the two were in the process of separating. Jonze released his own feature directorial début, “Being John Malkovich,” the same year that “The Virgin Suicides” premièred, and while Coppola’s film had a modest return his became an indie sensation. She recalled feeling, in their relationship, an echo of her mother’s experiences. Jonze and a few of his friends had discussed launching a directors’ collective, and, according to Coppola, they didn’t even invite her to join. “I don’t want to embarrass Spike and those guys,” she said. “I think it’s just about understanding the dynamic there, which was a very nineties, dudes’-club dynamic. I was going around with Spike to promote his films, and I was just kind of the wife.” (Jonze could not be reached for comment.)

She was surprised when “Lost in Translation” became a runaway hit, not only winning her an Oscar but earning more than a hundred million dollars worldwide on a four-million-dollar budget. “I thought I was writing this really indulgent piece,” she recalled. “I mean, who cares about some rich girl trying to find herself?” But audiences connected to the film’s fuzzed-out mood of dislocation and the tragicomic pleasures of two lost people finding each other for a moment in time. At the end of the film, Bob and Charlotte share a kiss, and he whispers something inaudible into her ear. “I never even wrote that line,” Coppola said. “Bill always said that it was something that should stay between them.”

There is an adage in Hollywood that actors want to win awards to boost their egos, whereas directors want to win awards to boost their budgets. After “Lost in Translation,” Coppola found herself courted by the major studios. The producer Amy Pascal, who was a top executive at Sony Pictures at the time, told me, “I was desperate to work with her.” When they met, in 2004, she asked Coppola what project she dreamed of making. Coppola answered immediately: “Marie Antoinette.”

Not long after the release of “The Virgin Suicides,” Coppola had read an advance copy of a biography of the French queen, by the British historian Antonia Fraser, and had written to Fraser asking to option it. “I know I will be able to express how a girl experiences the grandeur of a palace, the clothes, parties, rivals, and ultimately having to grow up,” she wrote. “I can identify with her role of coming from a strong family and fighting for her own identity.” At first, Coppola endeavored to make her script biographically comprehensive, covering Marie Antoinette’s life all the way up to the guillotine. Fraser, writing later in Vanity Fair, recalled telling Coppola that the script seemed to lose energy in its final act, as if Coppola had been uninterested in “the mature woman’s tragic fate.” Fraser went on, “When she asked me lightly, ‘Would it matter if I leave out the politics?,’ I replied with absolute honesty, ‘Marie Antoinette would have adored that.’ ”

Coppola’s film, released in 2006, tells the story of the profligate, unfeeling monarch from the history textbooks as an intimate coming of age, following her from the time she was shipped to Versailles from her home in Austria as a fourteen-year-old peace offering between nations to her departure from the palace, nineteen years later, as the French Revolution set in. Coppola told me that she wanted to capture the idea of “the kids taking over the kingdom.” She allowed Dunst to retain her American accent and filled the film with anachronistic music and energetic montages, including a feverish shopping scene set to a remix of “I Want Candy.” (Roman, her brother, who shot most of the film’s closeups, planted a pair of Converse sneakers among the rococo mules.) When an angry mob grumbles about the queen’s infamous (and likely apocryphal) line “Let them eat cake,” Dunst tells her girlfriends, “That’s such nonsense, I would never say that!” The movie is almost obscenely beautiful; every shot has the composed lusciousness of a box of petits fours. The bracing opening sequence—Coppola has never missed on an opening shot—was inspired by a Guy Bourdin photograph of a model in repose: lounging in a petticoat, with an attendant massaging her feet, Dunst’s Marie swipes her finger through the frosting of a layer cake and then delivers the camera an insolent stare. When Coppola showed her father an early cut of the film, he advised her to give Louis XVI more lines. Like Eugenides, he was missing the male perspective. “I was, like, ‘Um, Dad, no,’ ” Coppola remembered, adding, “I honestly don’t care about anyone else’s point of view. Just hers.”

Coppola and Mars began dating during the film’s making. Mars, who was born and raised in the town of Versailles, recalled, “It’s like living in a museum. You can’t disturb anything. It’s not welcome.” With “Marie,” there was excitement in seeing Versailles “embrace something new.” But not all French people appreciated the result. At a press screening at Cannes, some viewers booed. Many critics dismissed the movie as an ahistorical powder puff, an impudent exercise in vibes-first filmmaking. Others thought it was a masterpiece. The response was so divided that the Times made an unorthodox decision to publish duelling reviews from its two chief movie critics. Manohla Dargis, in the “anti” camp, wrote, “The princess lived in a bubble, and it’s from inside that bubble Ms. Coppola tells her story.” For some, though, the film’s reception only reinforced Coppola’s claim to its thematic substance, as a woman who knows a thing or two about the distorting effects of public exposure. (One of her close friends, the fashion designer Marc Jacobs, told me, “It’s so easy to throw around these titles like ‘nepo baby.’ What do you do, kill yourself because you come from a good family? Do you just not make art?”) Roger Ebert saw the movie’s slim perspective as a strength: “Every criticism I have read of this film would alter its fragile magic and reduce its romantic and tragic poignancy to the level of an instructional film.”

How one feels about Coppola’s narrow approach to storytelling might depend, in part, on where one stands in relation to her field of vision. When “Lost in Translation” came out, some Asian and Asian American critics took issue with the film’s depiction of Japanese culture through the eyes of Western visitors. Accented English was played in the movie for laughs. Tokyo establishments were portrayed as “superficial, inappropriately erotic, or unintelligible,” as Homay King, a film-studies professor at Bryn Mawr, wrote in Film Quarterly. King wondered what level of awareness Coppola had brought to this portrayal: Did the tone of bewildered Orientalism belong to her characters or to her? Coppola defended her depiction to the Los Angeles Times by saying, “My story is about Americans in Tokyo. After all, that’s all I know.” But she didn’t seem to reckon with the inherent sensitivities of depicting another culture from a distance. “I did wonder if all the ‘r’ and ‘l’ switching would be offensive,” she said back then. “But my crew thought it was funny.” (“It was a different time,” she told me. “I haven’t thought about how I would approach it now, but probably not in the same way.”)

“My father is just so into filmmaking that he thinks everyone should be doing it,” Coppola says.Photograph by Thea Traff for The New Yorker

Coppola confronted a similar backlash more recently, to a movie set on American soil. “The Beguiled,” from 2017, is a remake of a 1971 movie that takes place during the Civil War, about a group of white Confederate women who are driven into an erotic fervor when a wounded Union soldier arrives at their boarding school in an isolated mansion. Both the original film and the novel on which it is based also feature an enslaved Black woman who works in the house. Coppola, fearful of perpetuating stereotypes, decided to omit the character altogether, and explained away the absence with dialogue at the beginning of the film: it was nearing the end of the war, and “the slaves left.” In the U.S., the release was dominated by discourse about the character’s erasure; at Slate, the writer Corey Atad lambasted the film for its “whitewashing of slavery.”

The fallout forced Coppola to consider that there are hazards to writing only what you know, or “leaving out the politics,” if doing so means waving away inconvenient complexities. The critic Angelica Jade Bastién, of New York and Vulture, told me, “What Coppola does best is also her greatest weakness: she creates fables about modern white femininity.” She went on, “Art is political whether the artist wants it to be or not. Coppola is someone studying whiteness, but who doesn’t perhaps understand her own whiteness very well. It is because of that contradiction that her work doesn’t get deeper.” Coppola told me, “I admit it was probably stupid to do something on the Civil War.” But she also suggested that her “creative license” with the source material had been “misinterpreted as insulting.” She’d been interested in portraying the unravelling of a group of cossetted women when there were no men around or slaves left to tend to them. “It’s the kind of world I like, really claustrophobic,” she said, adding, “They were so used to being taken care of, and they didn’t know how to do anything for themselves.”

During one conversation, Coppola confessed, “Sometimes I feel like I make the same film over and over, and I’m probably becoming a cliché of myself.” In some ways, “Priscilla” resembles her previous movies, but in contrast to a film like “Marie Antoinette,” with its baubles and brocades, the new film is strikingly joyless in its depiction of life inside a gilded cage. In part because Coppola was denied the rights to Elvis’s music, the exuberance of rock and roll is all but absent from the film. Priscilla interacts with Elvis mostly at home, where he’s dressed down, needy, and sporadically abusive. Through the murmurings of tertiary characters, Coppola laces the film with reminders of Priscilla’s tender age, which was troubling even if you believe, as Presley claimed in her book, that she and Elvis did not consummate their relationship until they were married, when she was twenty-one. One of the film’s strongest sequences shows Spaeny trying to occupy herself in Graceland while Elvis is away. She ambles around in a doll-like white dress and too-big matching heels. She tries out various seats in the living room and plunks a single key on Elvis’s baby grand. She is less a kid taking over the kingdom than a child left home alone.

Just as Coppola rarely concerns herself with events beyond her characters’ sequestered worlds, she doesn’t show what happens to the ones who escape the waiting room of their lives. The final shot of “Priscilla” shows Spaeny driving out of the gates of Graceland. We hear Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You,” both mournful and triumphant. Coppola has hinted at a desire to, as she put it in one interview, “grow up and do other subject matter,” beyond adolescence, but she gave me little sense of what that might look like, besides, perhaps, teaming up again with Dunst, who is now in her early forties. Coppola’s past films have romanticized the bonds between famous older men and younger women, but she told me that her attitude about such connections has shifted with the times. Her project before “Priscilla,” “On the Rocks,” from 2020, centered on a fortyish writer, Laura (Rashida Jones, who is the daughter of the music producer Quincy Jones), and her big-time art-dealer dad, Felix (Bill Murray). The character of Felix, whom Coppola said she based on her “dada and his buddies,” is a gregarious man of style, who wears silk scarves and considers caviar a road snack. He is also an attention hog prone to errant flirting and chauvinist soliloquies. “Somewhere” was tinged with nostalgic sweetness about fathers and daughters: Coppola had the film’s protagonists—the divorcé movie star Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff) and his eleven-year-old, Cleo (Elle Fanning)—order every flavor of gelato from room service, “which is just the sort of thing my dad would do,” and enlisted the Chateau Marmont’s late “singing waiter” Romulo Laki to serenade Cleo with Elvis’s “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear,” the same song that Laki used to sing to Sofia when she was young. “On the Rocks,” by contrast, is both funnier and pricklier, charting Laura’s struggle to define herself outside of her dad’s overwhelming orbit. Drinking a Martini at Bemelmans, Felix tells Laura that he is going deaf to the frequency of female voices. Laura yells at the end of the film, “You have daughters and granddaughters, so you’d better start figuring out how to hear them!”

Eleanor has often shot behind-the-scenes footage on Sofia’s films, as she did for Francis. She has eighty hours from the making of “Marie Antoinette,” which Sofia told me she’s helping turn into a documentary. In 2016, at the age of eighty, Eleanor also released her first feature, a comedy called “Paris Can Wait,” becoming the oldest American woman to make a directorial début. But lately Eleanor has been ill, and the family has been shuttling back and forth to her bedside in California. On Sofia’s birthday last year, which coincided with Mother’s Day, the two “sat in the hospital and ate tuna sandwiches,” Eleanor told me. Last October, “Priscilla” had its American première at the New York Film Festival. The strikes in Hollywood meant that there were almost no actors on the red carpets, but, because “Priscilla” involved no major-studio funding, Coppola was among the few directors given special dispensation to have her film’s stars do promotion. Elordi and Spaeny were at the première, but Coppola herself was missing. Henley, her producer, read a statement in her stead: “I’m so sorry to not be there with you, but I’m with my mother, to whom this film is dedicated.”

One recent evening, hundreds of Coppola fans lined up at a Barnes & Noble in central L.A. for an “Archive” book signing. Coppola is, as her daughters recently informed her, “big on TikTok,” and some Gen Z fans have taken to calling her “Mother,” an influencer to the influencers. (One viral video shows a young woman ranting about cleaning her room: “When a boy’s room is messy, it’s, like, ‘Oh, my God, he’s filthy,’ ” she says, adding, “When a girl’s room is messy? It’s Sofia Coppola.”) At the bookstore, the crowd was largely made up of teen-agers, many of whom had donned costumes: gossamer pink tutus and oversized hair bows that evoked Marie Antoinette’s style; chokers with heart pendants like one Spaeny wears in the “Priscilla” trailer. One wore a vintage T-shirt by Milkfed, Coppola’s fashion line, which she sold years ago but which has, in recent years, become a cult brand among a new generation of fans, including the pop star Olivia Rodrigo.

A young woman wearing a skirt custom-printed with a still from “The Virgin Suicides” reached the front of the line and held her hand to her chest. “You literally invented ‘aesthetic,’ ” she said to Coppola, using slang for the kind of exquisitely curated look that teens strive for on social media. There was an amusing mismatch between the fans’ gushing and Coppola’s low-key energy. She did not say much more than a warm “oh, thank you” or “that’s so sweet” as she received their compliments.

Leaving the bookstore, at dusk, Coppola said that she was looking forward to ordering room service at the Beverly Hills Hotel, whose menu she knew from childhood breakfasts spent talking filmmaking there with her father. (The eggs Benedict is apparently first-rate.) We walked together toward a black car waiting for her at the curb. After the harsh fluorescent lighting in the bookstore, the L.A. streets looked pleasingly subdued. I pointed at the sunset, which was a shade of powdery pink.

“Oh, yeah,” Coppola said, her eyes moving lackadaisically toward the sky. “It’s a little like I directed it.” ♦

An earlier version of this article misstated Jacob Elordi’s height and the year Sofia Coppola and Amy Pascal met.Published in the print edition of the January 29, 2024, issue, with the headline “Crème de la Crème.”

0 notes

Text

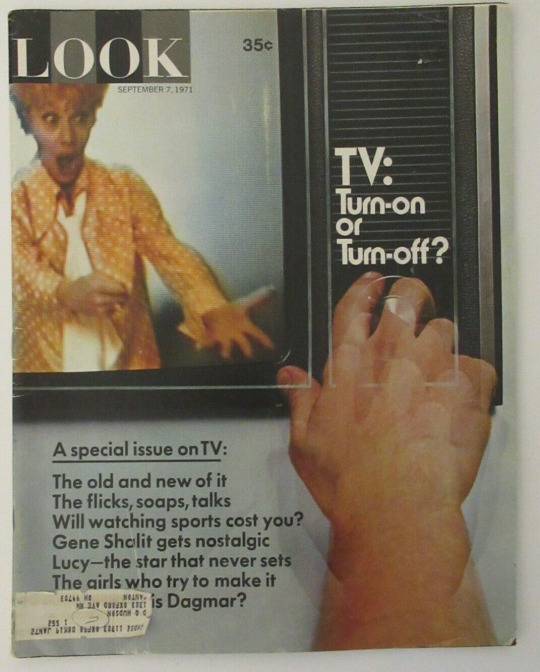

LOOK! TV: TURN ON OR TURN OFF?

September 7, 1971

The September 7, 1971 issue of LOOK Magazine (volume 35, number 18) dedicated their entire issue to the medium of television. Inside, there is a feature titled “Lucille Ball, the Star That Never Sets...” by Laura Bergquist on page 54.

The photograph on the cover is slightly distorted to give it the look of an image through a TV screen. The shot was taken by Douglas Bergquist in January 1971.

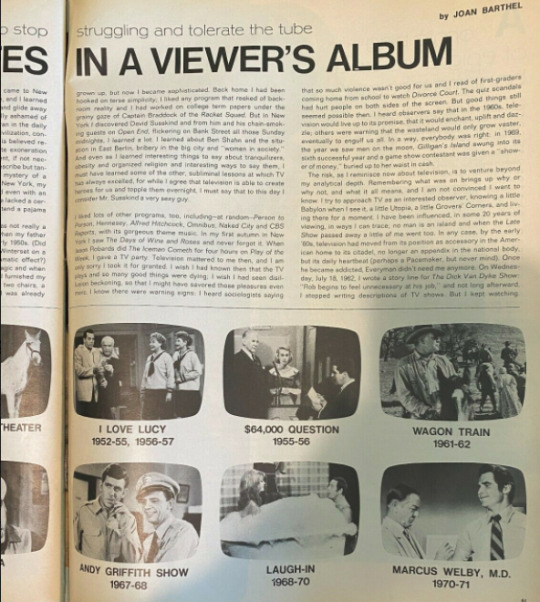

The issue presents a variety of viewpoints about the state of television. Is it ‘tired’ or is there an infusion of new energy to take it into the new decade? John Kronenberger writes an article that asks if cable television is the future. Hindsight tells us that it was not only the future, but is now the past.

“Lucille Ball, the Star That Never Sets...” by Laura Bergquist.

Bergquist first interviewed Lucille Ball in 1956 for the Christmas issue of Look.

The photograph is by Douglas Kirkland, a Canadian-born photographer, who not coincidentally, also took the photograph used on the cover. This shot was taken in the garden of Ball’s home in June 1971. At age 24, Kirkland was hired as a staff photographer for Look magazine and became famous for his 1961 photos of Marilyn Monroe taken for Look's 25th anniversary issue. He later joined the staff of Life magazine.

Bergquist launches the article talking about her friend Sally, who is besot with watching Lucille Ball reruns, preferring Lucy over the news. Under the headline, she sums up the purpose of her interview: “Sorry, Sally. But Lucy is a serious, unfunny lady. So how come she’s a top clown of the fickle tube for twenty years, seen at home 11 times weekly and in 77 countries?”

LUCILLE BALL: THE STAR THAT NEVER SETS...

(Lucille Ball’s quotes are in BOLD. Footnote numbers are in parentheses.)

My neighbor Sally, nine, turns out to be a real Lucy freak. Though she likes vintage-house-wife I Love Lucy best, she'll watch Lucille Ball 11 times a week, if permitted. That's how often Madame Comedy Champ of the Tube, come 20 years this October, can be caught on my local box. Ten reruns, plus the current Here's Lucy on Monday night, CBS prime time. Friends, that's 330 weekly minutes of Lucy, which should be rank overexposure. Did you know that even the U.S. man-on-the-moon walkers slipped in ratings, second time around?

Quel mystery. Variety last fall announced that old-fashioned sitcoms and broad slapstick comedy are passé, given today's hip audiences. With one big exception - Lucy. When the third Lucy format went on in '68, reincarnating Miss Ball as a widowed secretary (with her real-life son, Desi Jr., now 18, and Lucie Jr., 20), Women's Wear Daily said not only were the kids no talent, but the show was "treacle." "One giant marshmallow," quoth the Hollywood Reporter, "impeccably professional, violence-free, non-controversial . . . 100% escapism."

Miss Ball: "Listen, that's a good review. I usually get OK personal notices, but the show gets knocked regular."

So why does Sally, like all the kids on my block, love slapstick, non-relevant Lucy? "Because she's always scheming and getting into trouble like I do, and then wriggling her way out of it." A 44-year-old Long Island housewife: "Of course I watch. I should watch the news?" When the British Royal Family finally unbent for a TV documentary, what was the tribe watching come box-time? Lucy, over protests from Prince Philip. (1)

"I've been a baby-sitter for three generations," says Miss Ball briskly. "Kids watch me during the day [she outpulls most kiddy shows]. Women and older men at night. Teen-agers, no. They look at Mod Squad. Intellectuals, they read books or listen to records.... You know I even get fan mail from China?" MAINLAND CHINA? "Hong Kong, isn't that China?" No. "Where is it anyway?"

The Statistics on the Lucy Industry are numbing. In recent years, she has run in 77 countries abroad, including the rich sheikhdom of Kuwait, and Japan, where, dubbed in Japanese yet, she's been a long-distance runner for 12 years. Where are all those funny people of yesteryear - Jackie Gleason, the Smothers Brothers, Sid Caesar, the Beverly Hillbillies - old reliables like Ed Sullivan, Red Skelton? Gone, all gone, form the live tube - except for reruns dumped by sponsors, out of fashion, murdered in the ratings.

Even this interview is a rerun. Fifteen years ago, I sat in Miss Ball's old-timey movie-star mansion in Beverly Hills, wondering how much longer, oh Lord, could Lucy last? She has a different husband, a genial stand-up comic of the fast-gag Milton Berle school, Bronx-born Gary Morton, 49. He replaced Desi Arnaz, her volatile Cuban spouse (and costar and partner) of 20 years, who lives quietly in Mexico's Baja California, alongside a pool shaped like a guitar, with a second redhead wife. "Ever been here before?" asks Gary, now her executive producer, who's brightened the house decor. "Used to be funeral-parlor gray, right?"

Otherwise, the lady, like her show, seems preserved in amber. Though newly 60, she could be Sally's great-grandmother. Of a Saturday, she's unwinding from a murderous four-day workweek. Her pink-orange-fireball hair is up in rollers. Her black-and-blue Rolls-Royce, inherited from her friend, the late Hedda Hopper, is parked in the driveway. But in attitude and opinion, she comes across Madame Middle America, despite the shrewd show-biz exterior. Good egg. Believer in hard work, discipline, Norman Vincent Peale. Deadeye Dickstraight, she talks astonishingly unfunny - about Vietnam, Women's Lib, about which she feels dimly, marriage to Latins, books she toted up to her new condominium hideaway in Snowmass, Colo. "Snow" is her new-old passion, a throwback to her small-town Eastern childhood. For the first time in family memory, this lifelong workhorse actually relaxed in that 9,700-foot altitude for four months this year, learning to ski, reading Pepys, Thoreau, Shirley MacLaine's autobiography, "37 goddamned scripts, and all those Irvings" (Stone, Wallace, etc.). She had scouted for a mountain retreat far away from any gambling. Why? Is she against gambling? "No, I'm a sucker. I can't stay away from the tables."

From yellowing notes, I reel off an analysis by an early scriptwriter. Perhaps she comes by her comic genius because of some "early maladjustment in life, so you see commonplace things as unusual? To get even, to cover the hurt, you play back the unhappy as funny?"

Forget any deep-dish theorizing. "Listen, honey," says Miss B, drilling me with those big blue peepers, "you've been talking to me for four, five hours. Have you heard me say anything funny? I tell you I don't think funny. That's the difference between a wit and a comedian. My daughter Lucie thinks funny. So does Steve Allen, Buddy Hackett, Betty Grable."

BETTY GRABLE THINKS FUNNY? "Yeah. Dean Martin has a curly mind. oh, I can tell a funny story about something that happened to me. But I'm more of a hardworking hack with an instinct for timing, who knows the mechanics of comedy. I picked it up by osmosis, on radio and movie lots [she made 75 flicks] working with Bob Hope, Bert Lahr, the Marx Brothers, the Three Stooges - didn't learn a thing from them except when to duck. Buster Keaton taught me about props. OK, I'm waiting."

Well, I hedge, I caught Miss Ball in a few funny capers on the Universal lot this week. Like one day, in her star bungalow, she throws a quick-energy lunch in the blender - four almonds, wild honey, water, six-year-old Korean ginseng roots, plus her own medicine, liver extract. "AAAGH," she gags, then peers in the mirror at her hair, which is a normal working fright wig, "Gawd," she moans, "it looks as if I'd poked my finger into an electric-light socket!" No boffo line, but her pantomimed horror makes me laugh out loud. Working, she is fearless - dangling from high wires, coping with wild beasts. She talks of animals she's worked with, chimps, bears, lions, tigers. "I love 'em all, especially the chimps, but you can't trust their fright or panic. Like that baby elephant who gave a press job to a guest actress." (2) What's a press job? "Honey, once an elephant puts his head down, he keeps marching, right through walls." Miss Ball puts her own head down, crooks an arm for a trunk, and voila, is an elephant. Funny as hell. So off-camera she's no great wit, but then is Chaplin?

Four days a week, through the Thursday night filming before a live audience, she labors like some hungry Depression starlet. Monday a.m., she sits at the head of a conference table, lined by 12 staffers, editing the script. Madame Executive Tycoon in charge of everything, overseeing things Desi used to do. Also the haus-frau, constantly opening windows for fresh air and emptying ashtrays. She wears black horn-rims, three packs of ciggies are at the ready. "Do I have to ask for a raise again?" she impatiently drills the writers, "I've done that 400 times." "QUIET!" she yells during rehearsal, perching in a high director's chair, a la Cecil B. DeMille. "Isn't somebody around here supposed to yell quiet?" She frets about the new set. "Those aisles - they're a mile and a half wide. What for?" The audience is too far away, she won't get the feedback from their laughs are her life's blood. (Once I hear Gary Morton on the phone, in his British-antiqued executive office, saying: "We need your laugh, honey. Go down to the set and laugh; that's an order.")

That physical quality about her comedy, a la the old silent movies or vaudeville - which were the big amusements of her youth - seems to transcend any language. (A Moscow acting school, I was told, shows old Lucy clips as lessons in comic timing.) So what did she learn from that great Buster Keaton?

"At Metro, I kept being held back by show-girl-glamour typing. I always wanted to do comedy. Buster Keaton, a friend of director Eddy Sedgwick, spotted something in me when I was doing a movie called DuBarry - what the hell was the name? - and kept nagging the moguls about what I could do. Now a great forte of mine is props. He taught me all about 'em. Attention to detail, that's all it is. He was around when I went out on a vaudeville tour with Desi with a loaded prop." What's that? "Real Rube Goldberg stuff. A cello loaded with the whole act - a seat to perch on, a violin bow, a plunger, a whistle, a horn. Honey, if you noodge it, you've lost the act. Keaton taught me your prop is your jewel case. Never entrust it to a stagehand. Never let it out of your sight when you travel, rehearse with it all week." Ever noodge it? "Gawd, yes. Happened at the old Roxy in New York. I was supposed to run down that seven-mile aisle when some maniac sprang my prop by leaping out and yelling 'I'm that woman's mother! She's letting me starve.'" What did you do? "Ad-libbed it, and I am one lousy ad-libber."

After 20 years, isn't she weary of playing the Lucy character? "No, I'm a rooter, I look for ruts. My cousin Cleo [now producer of Here's Lucy] is always prodding me to move. She once said Lucy was my security blanket. Maybe. I'm not erudite in any way, like Cleo. But why should I change? Last year was big TV relevant year, and I made sure my show wasn't relevant. Lucy deals in fundamental, everyday things exaggerated, with a happy ending. She has a basic childishness that hopefully most of us never lose. That's why she cries a lot like a kid - the WAAH act - instead of getting drunk."

Aha! Is Lucy the guileful child-woman, conniving forever against male authority - whether husband or nagging boss - particularly FEMALE? ("None of us watch the show," sniffed a Women's Libber I know, "but she must be an Aunt Tom." Still, I ponder, hasn't that always been the essence of comedy, the little poor-soul man - or woman - up against the biggies?)

"I certainly hope so. You trying to con me into talking about Women's Lib? I don't know the meaning of it. I never had anything to squawk about. I don't know what they're asking for that I don't have already. Equal pay for equal work, that's OK. The suffragettes rightly pressed a hard case - and when roles like Carry Nation come along, they ask me to play them, perhaps because I have the physical vitality. But they're kind of a laughingstock, aren't they? Like that girl who gave her parents 40 whacks with an ax? Didn't Carry Nation ax things, was she a Prohibitionist or what?" (3)

She'd just said nix to playing Sabina, in the movie of Thornton Wilder's The Skin of Our Teeth. Why? "I didn't understand it." She turned down The Manchurian Candidate for the same reason. "Got that Oh Dad, Poor Dad script the same week and thought I'd gone loony." If she makes another movie, she'll play Lillian Russell in Diamond Jim with Jackie Gleason, "a nice, nostalgic courtship story that won't tax anyone's nerves." (4)

Is Miss Ball warmed by the comeback of old stars in non-taxing Broadway nostalgia shows like No, No, Nanette? (5)

"Listen, I studied that audience. I saw people in their 60's and 70's enjoying themselves. That had to be nostalgia. The 30's and 40's smiled indulgently, that Ruby Keeler is up there on the stage alive, not dead. For the below 30's, it's pure camp. I don't put it down, but it’s not warm, working nostalgia, but the feeling 'Ye gods, anything but today'

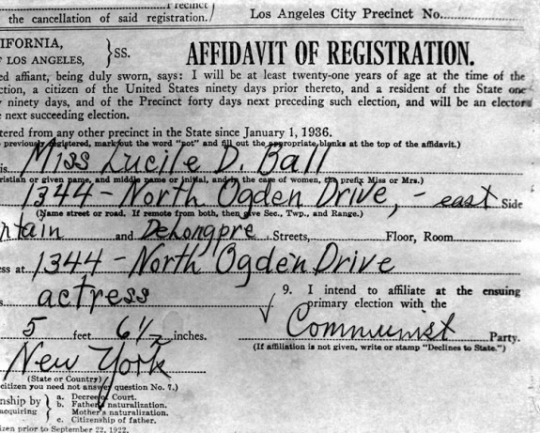

"Maybe I'm more concerned about things that I realize. I told you politics is definitely not on my agenda - I got burned bad, back in the '40's signing a damned petition as a favor. (6) Just say the word 'politician,' and I think of chicanery. Too many subversive angles today. But I must be one of millions who are so fed up, depressed, sobbing inside, about the news...the atrocities, the dead, the running down of America. You can't obliterate the news, but the baddest dream is that you feels so helpless.

"I was sitting in this very chair one night, flipping the dial, and came to Combat! There were soldiers crouching in bushes, a helicopter hovering overhead. Nothing happening, so I make like a director, yelling, 'Move it! This take is too LONG!' It turned out to be a news show from Vietnam. That shook me. There I was criticizing the director, and real blood was dripping off my screen... That drug scene bugs me. It's ridiculous, self-indulgent. We're supposed to be grateful if the kids aren't on drugs. They're destroying us from within, getting at our youth in the colleges. OK, kids have to protest, but how can they accomplish anything if they're physically shot?

"One of the reasons I'm still working is that people seem grateful that Lucy is there, the same character and unchanging view. There's so much chaos in this world, that's important. Many people, not only shut-ins, depend on the tube, too much so - they look for favorites they can count on. Older people loved Lawrence Welk. They associated his music with their youth. Now he's gone. It's not fair. (7) They shouldn't have taken off those bucolic comedies; that left a big dent in some folks' lives. Maybe we're not getting messages anymore from the clergy, the politicians, so TV does the preaching. But as an entertainer, I don't believe in messages.

"Some Mr. Jones is always asking why am I still working - as if it were some crime or neurotic. OK, I'll say it's for my kids. But I like a routine life, I like to work. I come from an old New England family in which everyone worked. My grandparents were homesteaders in New York and Ohio. My mother worked all her life - during the Depression in a factory."

What does she think of the new "relevant" comedy like All in the Family? "I don't know... It's good to bring prejudice out in the open. People do think that way, but why glorify it? Those not necessarily young may not catch the moral. That show doesn't go full circle for me."

Full circle?

"You have to suffer a little when you do wrong. That prejudiced character doesn't pay a penance. Does he ever reverse a feeling? I'm for believability, but I'm tired of hearing 'pig,' 'wop,' 'Polack' said unkindly. Me, I have to have an on-the-nose moral. Years ago, the Romans let humans be eaten by lions, while they laughed and drank - that was entertainment. But I’m tired of the ugly. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dancing, that's my idea of entertainment. Anything Richard Burton does is heaven. Easy Rider scared me at first because I knew how it could influence kids. But at least that movie came full circle. They led a life of nothing and they got nothing. Doris Day, I believe in her. Elaine May? A kook, but a great talent. Barbra Streisand? A brilliant technician."