#Suor Plautilla Nelli

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

👩🏻🎨 artists profile.

Sister Plautilla Nelli

aka Suor Plautilla

1524 - 1588

Nelli is the first known female Renaissance painter of Florence. She was born to a wealthy Florentine family and joined the Dominican convent of Santa Caterina di Cafaggio when she was 14. Nelli changed her name to Suor Plautilla. This is where she was learned art.

The convent was managed by the Dominican friars of San Marco who were lead at the time by Savonarola who was also a prophet. He encouraged the nuns to learn an art to prevent sloth, this turned the convent into a center of art. Nelli chose painting. She had a sister who chose writing.

The most famous of the sisters, Nelli taught herself how to paint and draw by studying other artists. She learned from artists like Angelo Bronzino, Andrea del Sarto, but her main influence was Fra Bartolomeo. Most of Nelli’s art was large and more expressive than the men she learned from. She signed her work “pray for the paintress”.

Plautilla Nelli was mentioned in Vasari’s book Lives of the Most Exellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

Sourced from Wikipedia

#female artist#female artists#Italian art#Italian history#art history#renaissance art#religious art#women in art#Plautilla Nelli#suor Plautilla#sister Plautilla#catholic art

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My first thought was: how sad. What fate could be worse than to be in close proximity to genius, capable of recognizing it, but, alas, something less-than? And [she] must have been less-than, because I’d barely heard of her. How terrible, and sadly typical, that in my long pursuit of women artists I’d apparently learned nothing. Least of all, that they are all too easily lost to time, a condition rarely any reflection on their talent.

- Bridget Quinn, Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (In That Order)

Plautilla Nelli, Suor Plautilla Nelli (1524-88)

Self Portrait, Sofonisba Anguissola (1554)

Irene di Spilimbergo, Titian and Gian Paolo Pace (c. 1560)

Self Portrait with Madrigal, Marietta Robusti (c. 1578)

Self Portrait in a Studio, Lavinia Fontana (1579)

Judith with Head of Holofernes, Fede Galizia (1596)

Self Portrait as Allegory of Painting (La Pittura), Artemisia Gentileschi (c. 1638-9)

Self Portrait as Allegory of Painting, Elisabetta Sirani (1658)

i. ii. iii. iv. v. vi. vii. viii.

#plautilla nelli#suor plautilla nelli#sofonisba anguissola#irene di spilimbergo#marietta robusti#lavinia fontana#fede galizia#artemisia gentileschi#elisabetta sirani#women artists#art history#historical women#history#european history#women#i will never be over it#am firmly staying on my bullshit when it comes to women artists#i have so many emotions#baroque#renaissance

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suor Plautilla Nelli, Annunciation. 16th century. Oil on wood. Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

#suor plautilla nelli#16th century#woman artist#women artists#nun artists#female painter#italian artist#annunciation#art history#history of art#early modern

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le parole dell'amore. Ritratti di donne

Le parole dell’amore. Ritratti di donne

San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Firenze – Festa della Toscana 2021 Biblioteca Comunale, sabato 7 maggio 2022, ore 18 San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Firenze – La conferenza performance ideata e curata da Giovanna M. Carli per esprimere con forza il no ai linguaggi d’odio, in occasione della Festa della Toscana 2021, sarà presentata sabato 7 maggio 2022 alle ore 18.L’evento, organizzato dalla…

View On WordPress

#Agata Smeralda Petrognani#Anna Maria Luisa de&039; Medici#Biblioteca comunale di San Casciano in Val di Pesa#Consiglio regionale della Toscana#Contro i linguaggi d&039;odio#Cristina Campo#Festa della Toscana#Florence Nightingale#Giorgia Frosecchi#Giovanna M. Carli#Margherita Hack#Martina Ciani#Martina Ricci#Maura Masini#Parole d&039;amore#Ritratti di donne#Suor Plautilla Nelli#Tiziana Giuliani

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Sister Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588) was a self-taught nun-artist and the first known female Renaissance painter of Florence. She was a nun of the Dominican convent of St. Catherine of Siena located in Piazza San Marco, Florence, and was heavily influenced by the teachings of Savonarola and by the artwork of Fra Bartolomeo.

Life

Pulisena Margherita Nelli was born into a wealthy family in the San Felice area of Florence. Her father, Piero di Luca Nelli, was a successful fabric merchant and her ancestors originated from the Tuscan valley area of Mugello , as did the Medici dynasty . There is a modern-day street in Florence, Via del Canto de' Nelli, in the San Lorenzo district, named for her family, and the New Sacristy of the Church of San Lorenzo is the original site of her family homes.

She became a nun at the age of fourteen, taking on the name Suor Plautilla, at the convent of Santa Caterina di Cafaggio; she would later be prioress on three occasions. The facility was managed by the Dominican friars of San Marco, led by Savonarola. About half of all educated girls in that era were placed into convents to avoid the cost of raising a dowry. Savonarola's preachings promoted devotional painting and drawing by religious women to avoid sloth, thus the convent became a center for nun-artists. Her sister, also a nun, Costanza, (Suor Petronilla) wrote a life of Savonarola.

Nelli had the favor of many patrons (including women), executing large pieces and miniatures. Sixteenth-century art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote, "and in the houses of gentlemen throughout Florence, there are so many pictures, that it would be tedious to attempt to speak of them all." Fra' Serafino Razzi, a sixteenth-century Dominican Friar, historian and Savonaroliano (disciple of Savonarola), named three nuns of Santa Caterina as disciples of Plautilla, Suor Prudenza Cambi, Suor Agata Trabalesi, Suor Maria Ruggieri, and three others as additional producers: Suor Veronica, Suor Dionisia Niccolini, and his sister Suor Maria Angelica Razzi.

Art and style

Though she was self-taught, she copied works of the mannerist painter Agnolo Bronzino and high Renaissance painter Andrea del Sarto . Her primary source of inspiration came from copying works of Fra Bartolomeo , which mirrored the classicism -style enforced by Savonarola's artistic theories. Fra Bartolomeo left his drawings to his pupil, Fra Paolino who, in turn left them in the possession of "a nun who paints" in the convent of Santa Caterina da Siena. Nelli signed her paintings as "Pray for the Paintress" after her name, confirming her role in spite of her gender. Her work is distinguished from that of her influencers by the heightened sentiment she added to each of her characters' expressions. Author Jane Fortune referred to her Lamentation with Saints and the "raw emotional grief surrounding Christ's death as depicted through the red eyes and visible tears of its female figures" as a case in point. Nelli's Lamentation, which is now in the Museum of San Marco, Florence, has also spurred the writings of The Painter-Prioress of Renaissance Florence, written by Jonathan K. Nelson. Most of Nelli's works are large-scale, which was most uncommon for a woman to paint, in her era.

She is one of the few female artists mentioned in Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Her work is characterized by religious themes, with vivid portrayals of emotion on her characters' faces. Nelli lacked any formal training and her male figures are said to have “feminine characteristics”, as her religious vocation prohibited study of the nude male.

Works created, rediscovered, and restored

DocumentaryThe Restoration of Lamentation with Saints: Plautilla Nelli is a thirty-six-minute documentary on the life of Nelli and on the process of restoring of one of her most significant large-scale paintings. The documentary, produced in 2007 by Art Media Studio, Florence, was developed and funded by The Advancing Women Artists Foundation's founder Jane Fortune and The Florence Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts.The documentary explores the preparatory drawings beneath the painting's pictorial surface using the process of reflectography. It shows various steps of the restoration project safeguarding the painting against woodworms, found in the painting's wood panel and exterminated, and centuries of encrusted dust and dirt. The documentary's main protagonists include museum executives and art conservation experts such as the San Marco Museum director Dr. Magnolia Scudieri and Florentine restorer Rossella Lari. The restored painting was completed in October 2006, and unveiled at Florence's San Marco Museum where it is exhibited in the large refectory. In her closing comment, Scudieri states, "Not only can we more clearly see the painting's expressive intensity thanks to this restoration, we can also more fully understand the convent life of Plautilla Nelli and her time in Florence.

PBS television documentaryThe Emmy-winning PBS television documentary (June, 2013) Invisible Women, Forgotten Artists of Florence, based on Dr. Jane Fortune's book by the same title, features a segment on Suor Plautilla Nelli and the restoration of the Lamentation with Saints. The television special, which spotlights the thousands of works by women in storage in Florence's museums, hails the little-known nun-painter as "the first woman artist of Florence."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plautilla_Nelli

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Punto VIII-Eva e le Monache- Tutte le Eva del mondo

Punto VIII-Eva e le Monache- Tutte le Eva del mondo

L’ultima cena di Suor Plautilla Nelli

Sapete perché molte donne preferivano i voti alla vita matrimoniale nel Medioevo e nel Rinascimento?

Cari miei l’intelligenza femminile a quei tempi era soggetta al patriarcato, prima dei padri poi dei mariti, mentre entrare in convento era una liberazione a questa priorità.

Molte donne là dentro, chiuse tra quattro mura votate alla castità…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Plautilla Nelli, Pained Madonna, c. 16th century Suor Plautilla Nelli was the first known female Renaissance painter in Florence, Italy.

#Plautilla Nelli#womens art#art#painting#religious art#16th century art#late renaissance#women's art#history

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

ARTE RENACENTISTA

El renacimiento en Europa no fue un sitio prometedor precisamente para las artistas emergentes. De las mujeres se esperaba que se casasen y tuviesen hijos, y aquellas que trabajaban no eran bienvenidas a las profesiones dominadas por hombres. De hecho, las mujeres no podían recibir información en las artes.

Pero algunas consiguieron emerger. Gracias a las enseñanzas privadas, generalmente dadas por los padres que las estaban guiando dentro del negocio, eran suficientemente talentosas como para ganar comisiones por sus propios medios, algunas mujeres consiguieron hacer sus vidas como artistas.

A continuación pasamos a conocer algunas artistas que despuntaron en su tiempo.

Levina Teerlinc

Pintora flamenca (ca.1510-1576) que trabajó como pintora en la corte inglesa de Enrique VIII, Eduardo VI, María I y Elizabeth I. Fue la miniaturista más importante en la corte inglesa entre Hans Holbein el Joven y Nicholas Hilliard. Su padre, Simon Bening era un famoso iluminador de libros y pintor en miniatura de la escuela de Gante-Brujas y probablemente la formó como pintora de manuscritos. Pudo haber trabajado en el taller de su padre antes de su matrimonio.

Poco se sabe acerca de su carrera o entrenamiento tempranos, pero en 1545 fue invitada a la corte de Enrique VIII, que había sido el patrón de Hans Holbein y Lucas Horenbout (quienes habían fallecido recientemente), y fue nombrada “dolorosa” real. Después de la muerte de Henry, ella continuó en este papel bajo la reina Mary I y la reina Elizabeth I.

Limitó su producción a las miniaturas de retratos, que son recuerdos personales que tienden a dispersarse ampliamente y no se muestran formalmente como lo son las pinturas de tamaño completo. Como resultado, ella es menos conocida que sus predecesoras y es más difícil atribuir sus obras con autoridad. De hecho, a pesar del hecho de que se sabe que ella pintó a muchos miembros de la corte, solo hay un puñado de obras que se le atribuyen y ninguna que definitivamente se sabe que está en sus manos.

Caterina van Hemessen

Pintora flamenca 1527-1587. Fue miembro del Gremio de San Lucas e incluso se convirtió en maestra de tres estudiantes varones. El patrón principal de Caterina fue María de Austria (Regente de los Países Bajos). Cuando María renunció a su puesto en 1556 y regresó a España, Caterina y su esposo fueron invitados a unirse a ella. María les dio fondos, permitiéndoles vivir el resto de sus vidas cómodamente.

Caterina van Hemessen era la hija del pintor manierista Jan Sanders van Hemessen. Fue entrenada por éste e incluso colaboró con él en algunas de sus pinturas.

Trabajó en retratos, pintando hombres y mujeres adinerados, generalmente sobre un fondo oscuro. y si bien creó al menos dos pinturas religiosas, fue principalmente una retratista. Ocho pequeños retratos y dos cuadros religiosos, con fechas entre 1548 y 1552, que llevan su firma, han sobrevivido. Retrató a hombres y mujeres ostensiblemente ricos posados a menudo contra un fondo oscuro. Las delicadas figuras que pintó tienen un encanto elegante y están provistas de elegantes trajes y accesorios.

Sofonisba Anguissola

Pintora italiana, 1532-1625. Sofonisba Anguissola fue la mayor de siete hijos en una familia aristocrática. En 1554 viajó a Roma y conoció a Miguel Ángel, quien reconoció su talento. Miguel Ángel incluso le envió algunos de sus propios dibujos para que ella los copiara y le enviara para que los critique.

Su padre se aseguró de que Sofonisba y sus hermanas fueran educadas en bellas artes. Sofonisba fue aprendiz de Bernardino Gatti. A la edad de 14 años su padre la envió, junto con su hermana Elena, a estudiar con Bernardino Campi, pintor también nacido en Cremona, un respetado autor de retratos y escenas religiosas de la escuela de Lombardía. Cuando Campi se mudó a otra ciudad, Sofonisba continuó sus estudios con el pintor Bernardino Gatti (conocido como «El Sojaro»).

Un total de 50 obras han sido atribuidas con seguridad a Sofonisba. Sus cuadros pueden ser vistos en las galerías en Bérgamo, Budapest, Madrid (Museo del Prado), Milán (Pinacoteca de Brera), Nápoles, Siena y Florencia (Galería Uffizi). Su obra ha tenido enorme influencia en las generaciones de artistas posteriores. Su retrato de la reina Isabel de Valois con una piel de marta cibelina fue el retrato más copiado en España. Entre estos copistas se incluyen muchos de los mejores artistas del momento, como Pedro Pablo Rubens.

Pintora italiana, 1552-1614. Lavinia Fontana era hija del pintor de la Escuela de Bolonia, Prospero Fontana, quien formó a Lavinia en pintura. El estilo de Fontana fue, efectivamente, muy cercano al manierismo tardío que practicaba su padre. Ya desde muy joven se hizo un nombre como pintora de pequeñas obras de gabinete, principalmente retratos.

La mayoría de las mujeres que en esta época se dedicaron a la pintura, aprendieron con sus padres. Y muchas se casaron con otro pintor del mismo taller. También es el caso de Fontana que se casó en 1577, con 25 años, con Gian Paolo Zappi. También era pintor del taller de Prospero Fontana y miembro de una familia noble. Tuvo once hijos con él. Siguió pintando durante su matrimonio para ayudar a la familia mientras su esposo se encargaba de la casa y asistía a su mujer como ayudante

Lavinia pintada en muchos géneros diferentes. Trabajó tanto con retratos como con escenas religiosas y mitológicas, que incluían desnudos masculinos y femeninos. Se ha documentado que ha pintado más de 100 obras, aunque solo 32 son conocidas hoy en día.

Fede Galizia

Pintora italiana, 1578-1630. Fede Gallizia, mejor conocida como Galizia, nació en Milán en 1578. Su padre, Nunzio Galizia, quien se mudó a Milán desde Trento fue un pintor de miniaturas. De él aprendió Fede a pintar, y se dice que a la edad de doce años era suficientemente considerada artista como para ser mencionada por Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, pintor y teórico del arte amigo de su padre, de la siguiente forma: «Esta joven se ha dedicado a imitar a nuestros más extraordinarios artistas».

Como hija de Nunzio Galizia, pintor de retratos, Fede Galizia fue un artista consumada a la edad de doce años. Enseñada por su padre, Fede tenía un gran ojo para los detalles y su habilidad para pintar ropa y joyas la convirtió en una retratista muy popular.

Además de los retratos, también le encargaron pinturas religiosas y seculares, y pintó varias representaciones de Judith y Holofernes. Fede. También estaba interesada en los bodegones, por lo que quizás sea más conocida. Fue pionera en el género para mujeres y su estilo ha influido en la evolución de la pintura de bodegones.

Artemisia Gentileschi

Pintora italiana, 1593-1652. Artemesia Gentileschi, la hija de Orazio Gentileschi, fue una de las artistas mujeres más reconocidas en el Renacimiento. Después de su muerte, la mayoría de las obras de Artemesia se atribuyeron a su padre y otros artistas hasta hace poco. Desde la reaparición de su obra y su historia, ha habido muchos estudios feministas de sus pinturas.

Fue entrenada por su padre, pero fue rechazada de las academias por su género. Luego continuó sus estudios bajo Agostino Tassi. Tassi violó a Artemesia y su padre posteriormente presentó cargos, lo que llevó a un juicio de siete meses durante el cual se le exigió que prestara testimonio bajo tortura. Tassi fue declarado culpable y Artemisia fue reivindicada, y se casó con el artista Pierantonio Stiattesi poco después.

Se dice que el trauma del acoso sexual y el asalto que ella experimentó aparece en sus obras. Estas incluyen varias descripciones de las violentas historias de Judith y Holofernes y Jael y Sisera, así como versiones de Susanna y los ancianos en las que Susanna exhibe terror genuino.

Judith Leyster

Pintora de la Edad de Oro holandesa. Pintó obras de género, retratos y naturalezas muertas. Toda su obra se atribuyó a Frans Hals o a su marido, Jan Miense Molenaer, hasta 1893, cuando Hofstede de Groot le atribuyó siete pinturas, seis de las cuales están firmadas con su monograma distintivo “JL”. La mala atribución de sus obras a Molenaer puede haber sido porque después de su muerte muchas de sus pinturas fueron inventariadas como “la esposa de Molenaer”, no como Judith Leyster.

Existen especulaciones sobre el hecho de que Leyster siguió una carrera en la pintura como resultado de la bancarrota de su padre y la necesidad de traer fondos para la familia. Ella pudo haber aprendido a pintar con Frans Pietersz de Grebber, que dirigía un taller respetado en Haarlem en la década de 1620. Durante este tiempo, su familia se mudó a la provincia de Utrecht, y ella pudo haber estado en contacto con algunos de los Carvaggisti de Utrecht.

Se especializó en escenas de género de retratos, comunmente, de una a tres figuras, que generalmente exudan buen ánimo y se muestran sobre un fondo liso. Muchos son niños, hombres con bebida, etc. Leyster fue particularmente innovadora en sus escenas de género domésticas. Estas son escenas tranquilas de mujeres en el hogar, a menudo con velas o lámparas, especialmente desde el punto de vista de una mujer.

Plautilla Nelli

Sor Plautilla Nelli (1524–1588) fue una autora autodidacta, que era monja, y la primera pintora renacentista de Florencia, Italia. Pulisena Margherita Nelli nació en una familia adinerada en Florencia, Italia. Su padre, Piero di Luca Nelli, fue un exitoso comerciante de telas y sus antepasados se originaron en la zona del valle toscano de Mugello, al igual que la dinastía Medici.

Las predicaciones de Savonarola promovieron la pintura devocional y el dibujo de mujeres religiosas para evitar la pereza, por lo que el convento al que Nelli pertenecía se convirtió en un centro para monjas-artistas. Su hermana, también monja, Costanza, (Suor Petronilla) escribió una vida de Savonarola.

Aunque autodidacta, copió las obras del pintor manierista Agnolo Bronzino y del pintor renacentista Andrea del Sarto. Su principal fuente de inspiración fue la copia de obras de Fra Bartolomeo, que reflejaba el estilo de clasicismo impuesto por las teorías artísticas de Savonarola. Fray Bartolomeo dejó sus dibujos a su alumno, Fray Paolino, quien a su vez los dejó en posesión de “una monja que pinta” en el convento de Santa Caterina da Siena.

Properzia de Rossi

Properzia de Rossi nació en 1490, en Bolonia, Italia. Fue una de las pocas escultoras que se destacó tanto que Giorgio Vasari la incluyó en su famoso libro “Las Vidas de los Mejores Arquitectos, Pintores y Escultores Italianos”, de 1550. Properzia fue la única mujer escultora de su tiempo.

Era hija de un notario Girolamo Rossi. Sus padres supieron apreciar a una edad temprana el talento de su hija. La joven tuvo la oportunidad de aprender dibujo con grabador Marcoantonio Raimondi, donde se formó con pequeños bajorrelieves. Su pertenencia a una familia boloñesa medianamente poderosa le permitió dedicarse a las artes y acudir a la Universidad.

Su primer contacto con la escultura fue cuando realizó figuras en miniatura con los huesos de melocotones o albaricoques, tallándolos de forma esmerada y delicada, con gran detallismo. Estas piezas estaban consideradas como un objeto de lujo y eran muy solicitadas por la alta sociedad boloñesa. Esta forma de escultura va a hacerla muy popular, de modo que su fama comienza a ascender, comenzando a partir de 1520 a recibir encargos públicos.

Diana Scultori

Diana Scultori (b.1535 dC) fue una grabadora italiana de Mantua, Italia. Es una de las primeras grabadoras conocidas. Después de su matrimonio en 1575 con el arquitecto aspirante Francesco da Volterra, la pareja se mudó a Roma. Aquí, el enfoque de su trabajo fue reinterpretar obras de artistas vinculados a su esposo y los talleres papales.

Fue una de los cuatro hijos del escultor y grabador Giovanni Battista Ghisi. Diana aprendió el arte del grabado de su padre y del artista Giulio Romano.

La mayoría de las impresiones se hicieron para promover y apoyar su carrera como arquitecto. Fue considerada una mujer de negocios muy interesada, y una de las pocas mujeres artistas a quienes Vasari mencionó en la edición de 1568 de sus Vidas. Trabajó dentro de las restricciones que encontraron los artistas de su época, mujeres o no. Utilizó el trabajo de otros artistas como base para sus grabados, pero la mayoría de los dibujos de sus grabados procedían de su esposo, un miembro de la familia, incluido su padre, o un artista.

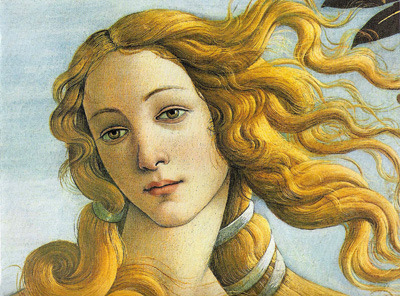

Imagen 1: La Nascita di Venere, Sandro Botticelli, pintura sobre lienzo, 1485 – 1486

Imagen 2: Autorretrato, Levina Teerlinc, pintura sobre lienzo, 1560-1565

Imagen 3: Autorretrato, Caterina van Hemessen, pintura sobre lienzo, 1548

Imagen 4: Autorretrato, Sofonisba Anguissola , óleo sobre lienzo, 1554

Imagen 5: Autorretrato, Lavinia Fontana , pintura sobre lienzo, 1580

Imagen 6: Judit con la cabeza de Holofernes, autorretrato, Fede Gallizia , óleo sobre tela, 1610

Imagen 7: Autorretrato como Santa Catherina, Artemesia Gentileschi , óleo sobre lienzo, 1616

Imagen 8: Autorretrato, Judith Leyster , pintura al aceite, 1633

Imagen 9: Virgen dolida, Sor Plautilla Nelli , óleo, no datado.

Imagen 10: José y la esposa de Potifar, Properzia de Rossi, bajorrelieve sobre mármol

Imagen 11: Diana Scultori, grabado.

0 notes

Text

How Nuns Have Shaped the Course of Art History

The Nun, 1983. Andy Warhol DANE FINE ART

How do you solve a problem like Maria, and unveil her place in art history? Maria di Ormanno degli Albizzi, a 15th-century Italian nun, was one of the earliest females in Europe to audaciously paint her own self-portrait. Forgoing the demure profile view that male artists customarily used in their depictions of refined quattrocento ladies, this miniature version of Maria stares out unswervingly from the heart of a sumptuous gold-and-blue checkered background. Yet this groundbreaking self-portrait was only intended to be seen by her Augustinian sisters; di Ormanno footnoted her likeness on the bottom of a page in a 490-folio prayer book.

We may think of nuns as sequestered, but di Ormanno was able to paint a daring self-image precisely because it was nestled between the covers of her breviary, just as she was safely cloistered inside the walls of the Florentine San Gaggio convent. For Renaissance nuns with a creative bent, convent life was not a problem—it was a creative solution. Many prospective nuns came from wealthy households and had some education; nunneries extracted women from the domestic responsibilities of marriage and motherhood, freeing them to further pursue their studies and even artistic careers.

Guglielmo Giraldi, Saint Catherine of Bologna, ca. 1469. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Suor Plautilla Nelli, Saint Catherine with Lily. Courtesy of the Advancing Women Artists Foundation.

A century later, in the early 1600s, Neapolitan painter Luisa Capomazza sought an escape from her potential future husbands, finding refuge in a convent. She “sent back every advantageous marriage proposal, [instead] nobly enjoying herself with painting, with which she was exceedingly in love,” writes her biographer, the late-Baroque art historian and painter Bernardo de Dominici. “Luisa, seeing herself almost constrained by the irksome pleadings of [a suitor] and his parents, decided to become a nun.” In the habit, Capomazza was free to paint a range of subjects, including altarpieces and landscapes. (The latter was an especially challenging genre for all women artists working in her time—direct study of nature was limited by rules of decorum, which dictated that women be chaperoned outside the home.)

During the Renaissance, it was a common practice for families to send women who weren’t in line to receive the hefty dowry reserved for the eldest daughter off to convents; but for a variety of economic reasons—plus the inclinations of women like Capomazza—convent populations exploded in Italy during the High Renaissance. In 1515, there were 2,500 nuns in Florence alone, and by 1552, 1 out of every 19 Florentines was a nun. The popularity of this lifestyle is unsurprising, considering the often-repressive alternative. In a way, convents have served as one of the most supportive artist residency programs available to women in the history of Western art.

Conservation work for Suor Plautilla Nelli's, Last Supper, c. 1560. Courtesy of the Advancing Women Artists Foundation.

“We think of these nuns as imprisoned, but it was a very enriching world for them,” Linda Falcone told Artsy. Falcone is the director of the Advancing Women Artists Foundation, a nonprofit organization devoted to identifying, restoring, and exhibiting art by women, much of which lies abandoned in the storage rooms of Italian museums. Italian Renaissance women “could obviously paint as part of their cultural education,” Falcone explained, “but the only way they could paint large-scale works and get public commissions was through their convent.”

Art historians have long recognized that a monastic life could be conducive to art-making. Some of the most beloved artists of the Italian Renaissance were monks, such as Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, Fra Bartolomeo, and Fra Carnevale. Paintings, sculptures, and illuminated manuscripts by their sisters, however—many of which have remained shuttered in convents for centuries—are just now coming to light.

Suor Plautilla Nelli, Lamentation with Saints. Courtesy of the Advancing Women Artists Foundation.

Miguel Cabrera, Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, ca. 1750. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

As they slowly emerge, artworks by nuns have been summarized by a derisive umbrella term: Nonnenarbeiten (German for “nuns’ works”). “We would never assign a Sacra conversatione [a type of devotional painting depicting the Virgin and Child] by Fra Angelico and a portrait by Fra Filippo Lippi to the same genre simply because both happen to have been painted by friars,” art historian Jeffrey F. Hamburger writes in his book Nuns as Artists (1997). “Far from providing an apt, let alone productive, characterization of the images it seeks to define, Nonnenarbeit stands by definition for deficiency: a lack of both skill and sophistication.” The term also neglects that these devotional images were, in their time, considered intellectual arts. Convents have always supported themselves with a number of craft enterprises, the real moneymakers being embroidery and textile work. Pursuing the finer arts—like painting and sculpture—would have been a sophisticated choice for any nun.

Recently, a group of scholars has argued that these works deserve a closer look. As Sheila Barker, an art historian affiliated with the Medici Archive Project, has written, it’s time “to liberate the nun-artist from Art History’s Procrustean bed.” Self-taught nun artists may not fit into the mold of the creative male genius, but their work served many important functions: It allowed nuns to exercise their talents, support the financial needs of their religious houses, and generate cultural prestige that attracted educated women to their convents.

Sor Juana Beatriz de la Fuente, Arbol de la Vida, 1805. Photo by Peggy Tenison. Courtesy of the San Antonio Museum of Art.

Plautilla Nelli, for example, was probably enticed to join the Florentine convent of Santa Caterina of Siena because of its artistic reputation. After entering the sisterhood in 1538 at age 14, Nelli gained access to the convent’s large collection of prints and drawings (some of which she may have traded with art historian Giorgio Vasari, who mentioned her in his second edition of Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, 1550). Nelli learned to paint at the convent. “She, beginning little by little to draw and to imitate in colors panels and paintings by excellent masters,” Vasari wrote, “has executed some works with such diligence, that she has caused artists to marvel.”

Her works were in demand, and she soon headed her own workshop at Santa Caterina with as many as eight nun-artists studying and working under her. Though they proudly produced devotional paintings for private collectors, the nuns of Santa Caterina also created expensive, monumental artworks for themselves. Nelli’s workshop painted a large-scale Last Supper (ca. 1560) for the convent’s refectory (nearly equal in length to Leonardo da Vinci’s fresco on the same subject). It is currently undergoing extensive restoration and will be unveiled to the public—for the first time in nearly half a millennium—this October.

If I, 1969. Sister Mary Corita Kent Steven Kasher Gallery

news of the week, 1969. Sister Mary Corita Kent Feuer/Mesler

Convents beyond Italy and after the Renaissance continued to nurture women artists, but their stories are still slowly being patched together as religious works change hands. Decades ago, Marion Oettinger, curator of Latin American art at the San Antonio Museum of Art, spotted an unusual 19th-century painting for sale at a gallery of Latin American folk art in California. He examined the signature and found that it was created by Juana Beatriz de la Fuente, a nun from colonial Mexico. This is still her only known work to date. “We have no idea who she was,” Oettinger told Artsy. He imagines that her life resembled that of her more famous sister of the cloth, the 17th-century Mexican scholar, painter, and poet Juana Inés de la Cruz, who had the luxury of a room of her own and materials provided for her. (Sor Juana has recently received some contemporary attention, from both a Mexican miniseries and a 2017 Google doodle.)

Further north, during the mid-20th century, Sister Mary Corita Kent of the Catholic Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in California created colorful silkscreens that earned her a reputation as the “Pop art nun.” Unlike nun artists of the Renaissance, Kent’s graphic prints were widely seen by a broad public, and her works were favored by celebrities such as director Alfred Hitchcock and composer John Cage. (Kent’s Roman Catholic Church superiors ultimately denounced her more political work, forcing her to leave her religious order in 1968.)

But the most famous artsy nun of our time is the recently departed Sister Wendy Beckett. The beloved British nun became an unlikely champion of art history for the masses, hosting a hugely popular series of BBC documentaries in which she offered guided tours of the world’s most vaunted arts institutions. When she was interviewed on the Charlie Rose Show at the height of her stardom in 1997, Beckett modestly noted that she was happy her programs were a hit, because so many people seemed to find them useful. Her series “helped them to escape from the confines of the narrowness of daily frustrations and anxieties,” she said. Art, Beckett suggested, can lift you out of the limitations of secular life. But for many women, it was religious life that freed them from the restrictions of the secular, and allowed them to flourish as artists.

from Artsy News

0 notes

Text

The New Year Puzzle

I will start my first blog of 2018 with a question, a puzzle for you to solve.

What is the connection between an anonymous group of feminist, female artists dressed up as gorillas, the twentieth century American author, journalist, and philanthropist, Jane Fortunea and the sixteenth century nun and talented artist, Suor Plautilla Nelli ?

Guerilla Girls poster

The Guerrilla Girls, a play on the…

View On WordPress

#Advancing Women Artists Foundation#Art#Art Blog#Art History#Italian Painters#Jane Fortune#Plautilla Nelli#The Florentine#The Guerilla Girls#The Last Supper by Plautilla Nelli#Uffizi Gallery Florence

0 notes

Text

Dr. Jane Fortune: Founder and Chair, Advancing Women Artists Foundation

Dr. Jane Fortune, Founder and Chair, Advancing Women Artists Foundation, who championed the notable research recognizing the work of Florence’s first woman artist, Plautilla Nelli, now being exhibited for the first time at Uffizi Gallery.

AWA founder Jane Fortune admires a newly restored painting by Nelli. Photo by Leo Cardini.

Indeed, until recently, Nelli’s works were mostly unknown, but thanks to the research of the Advancing Women Artists Foundation (AWA) based in Florence and the US, there are now 19 works attributed to her. Nelli was a sixteenth-century painter and a Renaissance woman in every way. She was a creative talent who tackled large-scale commissions despite the social conventions of her time and an entrepreneur whose art graced the homes of Florentine nobles.

Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper (1570s) is one of the most important paintings in the history of art by women. It is “The First Last”: the first and possibly only representation of a Last Supper by a female hand. AWA will restore Nelli’s masterwork to its original dignity with the help of the art-loving public through an international crowdfunding campaign on the Indiegogo platform. The goal of #TheFirstLast is to raise $65,000 by April 16, 2017. The painting, whose restoration is scheduled for completion in April 2018, will be permanently displayed at the Santa Maria Novella Museum. Do you want to join in and help restore Nelli's Last Supper?

Here, Dr. Fortune generously shares with LFF about her own pathway to creative work and research, the importance of this project to her, feminism and collaboration and more...

Where are you from? How did you get into creative work and what is your impetus for creating?

I was born in Indianapolis, IN. My parents were vociferous readers. A rule in our house for my siblings and myself growing-up was that each of us had to read so many pages, which were determined by our age, in a book of our choice, each week, write a report on what we had read and orally discuss what we read at the dinner table. If we failed to do such, we could not watch our allotted one (1) hour a week of TV. Because of this, I learned to love reading and writing, and this began my lifelong love of words and of writing.

Restoring the largest painting in the world by an early woman artist. Photo by Francesco Cacchiani.

Tell me about your current project and why it’s important to you. What do you hope people get out of your work?

I am the founder and chair of an American not-for-profit foundation, Advancing Women Artists (AWA), whose mission is to research, restore and exhibit works of art, by women, languishing, many for centuries, in the museum deposits in Florence, Italy. (I have lived in Florence part time over 20 years). Over the past 10 years, since AWA was founded, it has restored 40 works of art, by women, and found over 2,000 works of art, by women, hidden, and invisible, in the Florentine deposits. My five years of research, into finding these works languishing in the museum deposits, culminated into a book I wrote, titled “Invisible Women, Forgotten Artists of Florence”.

AWA’s current project is a crowdfunding campaign (#TheFirstLast) to fund the restoration of Suor Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper. Nelli is the first known woman artist of Florence and her Last Supper is the largest painting (21 feet long) in the world of that subject by an early woman artist. It has been hidden from the public eye for 450 years. Funding this work is important because she is an unknown in the art world, and as the first known woman artist of Florence, AWA wants to give her a “voice”, so she can reclaim her rightful place in Florence’s the cultural history. Does collaboration play a role in your work—whether with your community, artists or others? How so and how does this impact your work?

Collaboration is ALWAYS important. The more people, or the community, is involved, there is more broad based conversation about the subject and the work. An example: Nelli’s first ever solo exhibition is currently being shown at the Uffizi. AWA restored several of Nelli’s works for this show and underwrote the catalogue. This collaboration has been beneficial to both AWA and the Uffizi — to the Uffizi by AWA’ restoring several works, so they could be in the exhibition, and to AWA, the publicity, nationally and internationally, of the Uffizi show, which hopefully brings attention to its crowdfunding campaign.

Considering the political climate, how do you think the temperature is for the arts right now, what/how do you hope it may change or make a difference?

My overall hope, disregarding the political climate, which by all reports, looks very bleak for the arts in general, is that women artists, particularly of the past, “get their due”. For centuries, women artists have represented the hidden half of art history, invisible and unseen. It is their legacy that creates a connection with women of the present. We must salvage our creative past, for it is the first step in guaranteeing our own legacies as women of talent of the future.

AWA director in Italy researches Nelli manuscripts in storage at San Marco Museum. Photo by Kirsten Hills.

Artist Wanda Ewing, who curated and titled the original LFF exhibit, examined the perspective of femininity and race in her work, and spoke positively of feminism, saying “yes, it is still relevant” to have exhibits and forums for women in art; does feminism play a role in your work?

If feminism is defined as "the belief that women should be treated as intellectual and social equals to men", I guess feminism does play a role in AWA’s work. The reason AWA restores works of art only by women is because women artists, through the ages, have not been on a equal playing field as men and by restoring these works, hidden for centuries in the museum deposits in Florence, and rehung on museum walls for the public to see, it helps make the playing field more equal.

Ewing’s advice to aspiring artists was “you’ve got to develop the skill of when to listen and when not to;” and “Leave. Gain perspective.” What is your favorite advice you have received or given?

Don’t ever take “no” for an answer. When told something can’t be done, always find a way it CAN be done! “No” is never an answer.

http://theflr.net/nelli-crowdfunding

~

Les Femmes Folles is a volunteer organization founded in 2011 with the mission to support and promote women in all forms, styles and levels of art from around the world with the online journal, print annuals, exhibitions and events; originally inspired by artist Wanda Ewing and her curated exhibit by the name Les Femmes Folles (Wild Women). LFF was created and is curated by Sally Deskins. LFF Books is a micro-feminist press that publishes 1-2 books per year by the creators of Les Femmes Folles including the award-winning Intimates & Fools (Laura Madeline Wiseman, 2014), The Hunger of the Cheeky Sisters: Ten Tales (Laura Madeline Wiseman/Lauren Rinaldi, 2015) and BARED: Contemporary Poetry & Art by Women (Edited by Laura Madeline Wiseman, 2017). Other titles include Les Femmes Folles: The Women 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015 available on blurb.com, including art, poetry and interview excerpts from women artists. See the latest call for work on the Submissions page!

0 notes

Photo

Suor Plautilla Nelli, “Lamentation with Saints,” 16th century.

1 note

·

View note

Text

sede: Uffizi, Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture (Firenze); cura: Fausta Navarro.

Alle donne artiste, e in particolare alle donne che coltivarono il loro talento creativo tra le mura conventuali, gli studi hanno dedicato crescente attenzione, specie negli ultimi vent’anni.

Anche la figura di Plautilla Nelli (Firenze 1524-1588), la “prima pittrice fiorentina” le cui opere ai tempi di Giorgio Vasari erano disseminate nei conventi e nelle dimore dei gentiluomini fiorentini, è stata investita dall’impulso dei nuovi studi. Per tale motivo le Gallerie degli Uffizi hanno voluto inaugurare la serie di mostre dedicate alle donne artista con una monografica sulla suora pittrice.

Entrata a quattordici anni nel convento domenicano di Santa Caterina in Cafaggio – a Firenze, in piazza San Marco -, Plautilla, imbevuta della mistica savonaroliana, fu interprete appassionata della poetica figurativa ispirata al magistero di Girolamo Savonarola nel campo delle arti e al nuovo modello disciplinato di santità femminile della riforma tridentina.

Nel monastero fiorentino ricoprì la carica di priora e fu a capo di una fiorente bottega artistica grazie alla quale numerose consorelle sue discepole contribuirono alla diffusione di immagini sacre, avvalendosi di una tecnica pittorica da vere professioniste. Intesa come parte integrante del lavoro quotidiano delle suore e approvato come regola di tutte le terziarie domenicane, la creazione di immagini sacre era valutata essenzialmente per la loro efficacia devozionale e non certo dal punto di vista dell’originalità dello stile o della composizione. Il gusto “conservatore” nel campo artistico delle suore – e di Plautilla Nelli in particolare – rifletteva la scala dei valori maggiormente stimati, tra cui al sommo grado quelli che rappresentavano la continuità della illustre tradizione artistica domenicana.

L’attività artistica del convento di Santa Caterina in Cafaggio fu destinata a soddisfare principalmente la richiesta del mercato dei “parenti e clienti”, ovvero di coloro i quali erano legati alla vasta rete dei conventi toscani dell’Ordine dei Predicatori. La richiesta era diffusa a tal segno da implicare la serialità, come nel caso dei quattro dipinti raffiguranti l’immagine di una santa domenicana ritratta di profilo che costituiscono il fulcro di tutta la mostra.

La vendita di tali opere divenne poi fondamentale per la vita del convento di Santa Caterina all’indomani della riforma dei monasteri femminili emanata dai decreti tridentini (1566), riforma che sanciva la proibizione di ricercare beneficenze fuori delle mura conventuali.

Le modifiche apportate alle iscrizioni che riportano il nome di santa Caterina da Siena distinguibili nella serie dei quattro dipinti tramandano il nome di “un’altra Caterina”: suor Caterina de’ Ricci, coetanea di Plautilla e anch’ella fervente savonaroliana, suggerendo la possibilità che in tali ritratti la Nelli volesse rappresentare la “monaca santa” di Prato, uguagliandola alla santa senese.

Finalmente è giunto il tempo che a Plautilla si dedichi una mostra, il tempo di riscattare la sua memoria storica e le sue opere d’arte spesso, ingiustamente, assegnate a uomini artisti: una mostra questa di Plautilla che apre la serie delle iniziative che le Gallerie degli Uffizi hanno in programma di realizzare ogni anno dedicate all’altra metà del cielo, alle donne che seppero distinguersi anche nel campo delle arti.

#gallery-0-4 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-4 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Plautilla Nelli. Arte e devozione in convento sulle orme di Savonarola sede: Uffizi, Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture (Firenze); cura: Fausta Navarro. Alle donne artiste, e in particolare alle donne che coltivarono il loro talento creativo tra le mura conventuali, gli studi hanno dedicato crescente attenzione, specie negli ultimi vent'anni.

0 notes

Photo

Landmark Exhibition Looking at Work of Plautilla Nelli Extended to 4 June; Crowdfunding Campaign ends 16 April

As part of the push to showcase the works of women artists, the Galleria degli Uffizi launched an exhibition 8 March 2017 on the work of Suor Plautilla Nelli, one of the first documented female artists of the Renaissance. The show has been very well received, so much so that the exhibition is now slated to run until 4 June. Coinciding with the exhibition, sponsored in part by the Advancing Women Artists (AWA) Foundation, a crowdfunding effort has been launched to which supporters can donate through 16 April.

Alexandra Korey, representative of The FirstLast, the organizer of the fundraiser, shared the following release that suggests that the raised funds will be used to support ongoing restoration and conservation work for Nelli’s compositions:

“Plautilla Nelli's 191-pound canvas of The Last Supper needed six men to hoist it through the window and into the conservation studio, but the real 'window' on Nelli has opened during AWA’s campaign to involve the art-loving public in the restoration of this masterwork. In the last 40 days, Nelli has gone from being a virtually ‘invisible artist’ to being featured in 86 international newspapers, blogs, websites and magazines, thanks largely to TheFirstLast and the artist’s much-awaited Uffizi debut. The crowdfunding campaign ends on April 16 (Easter Sunday) whilst Nelli’s solo show will continue at Florence’s famed gallery until June 4.

And what would Girolamo Savonarola (who lit the first match on the Bonfire of the Vanities) think about Nelli’s recent appearance in Vanity Fair? For though the fire-and-brimstone Dominican preached in favor of art by convent women, he would likely be scandalized by the recent attention being showered upon the sixteenth-century nun who painted some of the Renaissance’s most precious works by a female artist. Several best-selling Tuscan-inspired authors from England, Canada and the United States, like Ross King, Dianne Hales and Sarah Dunant have come out in support of Nelli's Last Supper, in addition to Italian actress Elena Sofia Ricci. And so far, 322 people from 14 countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Philippines, United Kingdom, USA, United Arab Emirates) have contributed to crowdfunding campaign, allowing the Foundation to reach 72% of our total goal so far.

A surge of support is expected for the Final Week, but other good news has stemmed from TheFirstLast, which has proved an authentic awareness-raising enterprise, shedding light on the need to salvage the over 2,500 works by women in the Florence museums and storehouses, starting with the largest work in the world by an early women artists—this 21-foot signed Last Supper, the only work of its kind anywhere. The project’s overwhelming participation has inspired AWA Board Member Cay Fortune to create an ‘Adopt an Apostle Program’ for each of the painting’s 13 figures and she then went on to personally ‘adopt’ Saint John for 10,000 dollars. The youngest saint is now ‘taken’ but the other twelve are waiting to be claimed! These funds will serve to complete elements of the conservation project not covered by the crowdfunding and to underwrite the book and AWA documentary spotlighting recent discoveries. The ‘Adopt and Apostle program’ is especially significant because, as yet, not all of the Saints at Nelli’s Last Supper table have been assigned their proper names. Part of the restoration process involves in-depth research with Museum curators, conservator Rossella Lari and the Dominican friars of Santa Maria Novella to discover the iconography and stories behind each of the painting’s characters. Sponsors and the art-loving public will discover ‘who is who’ first hand, as the restoration continues.

The recent hubbub about Nelli and her work has inspired La Effe, an Italian channel broadcast on Sky, to feature AWA and Florence’s first female painter in one of the six episodes of the series ‘Noi siamo Cultura’ (We Are Culture) directed by Giuseppe Carrieri and produced by Natia Docufilm, in collaboration with the Toscana Film Commission.”

Donors can contribute to the fundraised until Sunday, 16 April; those interested in donating can do so here.

The Last Supper, 16th century. Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

Restoration work being executed on The Last Supper, which measures more than six meters in length (photograph courtesy of The Florentine).

Pained Madonna, 16th century. Museum of the Cenacolo of Andrea del Sarto, Florence.

#plautilla nelli#renaissance painting#women artists#florence#exhibitions#uffizi#awa#foundation#advancing women artists#last supper#art conservation#@awa_foundation

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Plautilla Nelli, la prima pittrice fiorentina COMMUNITY ARTISTICA CULTURALE "IL NOSTRO IMMENSO PATRIMONIO ARTISTICO CULTURALE"Google+ INVITO in Allegati:FINO 16 APRILE 2017 CAMPAGNA A FAVORE PER IL RESTAURO DELL'"ULTIMA CENA" 1570 di SUOR PLAUTILLA NELLI nota come POLISSENA DE'NELLI(1524 +1588)L'UNICA DIPINTA DALLA PRIMA PITTRICE FIORENTINA GRAZIE pittrice Susanna Galbarini ARTE.IT online MAPPARE L'ARTE IN ITALIA notizie e informazioni d'Arte con scheda personale profilo: www.arte.it/profilo.php

0 notes