#Standardization universally bad takes from non linguists starting to drive me crazy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

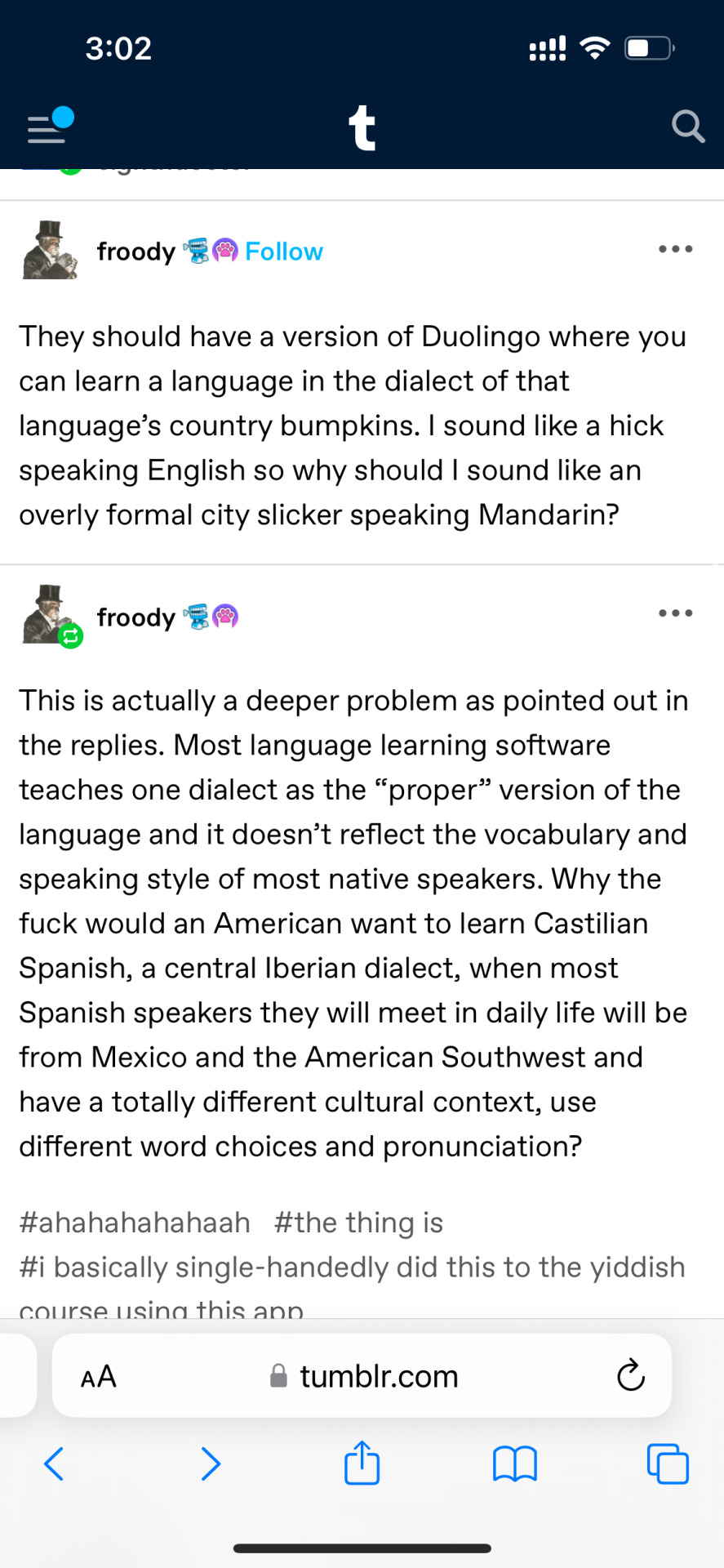

This is a post I think is absolutely Not Wrong but is also a pretty common laymans take about really complex issues made by linguists, educators and language planners around language teaching and style! These decisions often revolve around two issues:

Language is not neutral and strongly indexes region culture class and identity

ways to make language accessible and usable may involve decisions that are not linearly indexed to an Oppressive and Oppressed language form

What do I mean? I mean that “why does language software only teach one specific dialect” is as simple as BECAUSE IT IS MUCH MUCH EASIER FOR HUMAN BEINGS TO LEARN ONE SPECIFIC DIALECT. Why does it teach Standardized form? Because there is pretty much never just One country bumpkin form, and those separate “country bumpkin” forms are often not mutually intelligible to each other! Language teaching materials may well teach the queens English/ep instead of, say, rural Alabama English or rural Yorkshire English because the product is intended for audiences as wide as speakers in India, esl learners from Romania and living in the uk, and francophone elementary students in Canada. Does that mean that Rp is the only “right” English or that it’s better in some ways? No! It doesn’t even mean that the decision to teach rp is an inherently neutral one. It just means that questions of how to ensure usability and access are often infinitely more complex than people assume.

The problem with well meaning posts like this one is that they assume there IS “a vocabulary and speaking style of most native speakers,��� which is almost never the case. The decision to choose a particular “standardized” form often decides this, implicitly, but so do reactionary responses like this one. Instead, the issue is that language planning must by nature choose A VERSION, and usually not all versions, and that those decisions are complex as hell and require careful thought - often there are some outright strange decisions, but there are also some that don’t have an “easy” or good answer, and being able to think critically about them is a central aspect of linguistic justice.

In ref to the specific examples, I almost never see resources for Americans focused on Castilian Spanish - which I should know as someone trying to learn Castilian because it’s closer for the dialect filipino intellectuals actually wrote in. (Why the fuck would someone want to learn [blank] dialect well cause they want to]zInstead you get a semi formalised Latin American accent (that sometimes tends towards upper class Mexico City but not in all ways). While there are significant problems with the lack of dialect specific materials for various accents of latam spanish, a lot of the reasons behind the choice of this form come from the fact that..: there is no one single latam spanish, and many of the speakers in the U.S. speak significantly different dialects of Spanish! To choose, say, the Spanish of Guadalajara leaves out speakers of the Spanish or El Salvador or Puerto Rico etc. nuance

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

My response to extended periods of stress is to distract myself by cramming new things into my head. I had a terrible semester at college once and front-loaded the entirety of the sci.electronics.repair FAQ into my brain. It wasn't useful at the time, but I can repair the shit out of a VCR now, so I assume I'll use it someday. I am so overloaded I am about to claw my own face off, so naturally I am teaching myself Hebrew. I've been using Duolingo to do it, which is frankly a very bad idea. (I should really be using Ha'Ulpan, which is where you'd typically go for a crash course in Hebrew before emigrating to Israel, but that costs money, so no.) Duolingo is billed as a way to teach yourself a language, which it is not. It is a way to memorize a bunch of interactive flashcards. This might be effective for people who don't care how language works -- which is most people -- but it's awful for people like me, who hang all of their memorization off of a framework of base patterns. Duolingo explains nothing. The "lessons":

Do not teach the alphabet. Hebrew is written in this sort of half-assed abjad, where most but not all vowels are not marked in non-teaching texts, and some but not most unmarked vowels are actually represented by a placeholder Alef. 'Aba' is father and 'ima' is mother, but they are both written Alef-something else-Alef. Look at that and imagine how the vowel change looks totally mental to someone who spells things in a full alphabet. Alef comes out looking like it says about six different things, one of which is nothing.

Do not explain the orthography. There are several pairs of letters in Hebrew that do, or at least can, say the same thing. Tet and Tav both say /t/; Kaf and Qof both say /k/; Yod and Ayin are both sort of /j/ and sort of not; Vav and Bet can both say /v/, although both also have other readings; Samekh is /s/ and Shin can be read that way as well. Some other apparent character pairs are actually the same letter that has a 'sofit' form when it comes at the end of the word, which on the Hebrew keyboard is a different key (as opposed to the Arabic IME, which auto-corrects to the final form when it kerns all the cursive joining). I still have no idea if there is a rule behind Tet vs Tav; Yod vs Ayin and Kaf vs Qof are almost certainly because they once represented different sounds (Yaa vs 'Ayin and Kaa vs Qaf are still separated in Arabic), but I don't have enough context to guess which is likely to be which in Modern Hebrew.

Do not consistently read new vocabulary words out loud. If you're not going to explain the letters to me, the least you can do is read me the word so I can figure it out myself. Of course, it also never explicitly mentions that you read all this right-to-left, which seems like an important note to give when you're using a left-to-right language for instruction. You would think it would be obvious when everything is right-justified, but this is the kind of stuff you shouldn't take for granted when building beginning lessons in anything.

Do not use any nekkudot. A nikkud ("point") is a diacritical mark, mainly underneath the consonant but occasionally beside, inside, or above it, that explicitly indicates ('dagesh') a pronunciation change or ('nikkud') an unwritten vowel. This is how you teach people to read Hebrew, in Hebrew. You use it for small children. Or, if you have any sense, novice adult learners.

Do not explain any grammar. There is no explanation of why "you" is sometimes 'at' and sometimes 'atah'. No explanation of why sometimes the present-tense verb has an '-et' on the end and sometimes doesn't, even when the subject is 'ani' in both cases. (Answer: Hebrew inflects according to gender of both subject and speaker, which seems like a thing that should be noted for anglophones.) You are left to guess at wtf to do with prepositions and particles like Ha, V', Be, Le, and others.

Do not consistently account for the direction switch of Hebrew input. Firstly, there's no warning that the thing expects you to type in Hebrew; I installed a Hebrew keyboard before I started, but I also have six other keyboard layouts on the phone, because I'm me. If it wants you to type a full sentence, it can get the text running consistently right to left, but there are exercises that want you to fill in just one word, and that breaks it horribly. The words run right-to-left as intended, but they are arranged left-to-right in English order.

Do not listen to its own internal dictionary of synonyms. I have run into this in other languages and it drives me crazy. There are exercises where it asks you to translate a sentence in the target language into English. If you tap 'derech', Duolingo tells you it means a way, a path, or a road. Translating 'derech' as anything other than "way" in the English sentence gets you marked off. If there is some reason why 'Ha'yeled roah derech' could not mean "The boy sees a road" isolated from context, Duolingo does not give it.

I am already cheating by being a linguist who has some idea of how Semitic languages work. My one attempt at an Arabic class was a disaster for non-Arabic-related reasons, but I do know basic things like the idea behind an abjad, handling regular transformations of letter shapes at the end of a word, and how words are constructed by adding vowels/prefixes/suffixes to a triconsonantal root. These would be completely alien to most English speakers. There is a systemic way to accomplish transformations like the one from "(male) child" ('yeled') to "(female) child" ('yaldah') or "children" ('yeldim'), or from the noun "food" ('okel') to the verb for "to eat" ('le'kol'), but it is never actually pointed out.

I also have a living resource who grew up speaking Hebrew and enjoys teaching people things, usually at great length. I can ask the Eccentric all the weird stuff and he'll give me a long, detailed answer, fully 60% of which will have something to do with the original question. Technical grammar questions can be Googled to good effect, but the answers to cultural questions are, at best, unreliable. (Example: "Does Modern Hebrew have regional accents?" Google answer: "Modern Hebrew is very young and spoken in a contained geographic area. While there are some tiny variations in pronunciation and vocabulary, these are so slight it is unlikely a non-native speaker would ever notice them." Answer from actual Israeli person: "Absolutely, remind me next time I see you and I'll do imitations, some of them are hilarious.") [The question of accents is especially pertinent; I am never comfortable in a language until I sound like myself, and since I don't sound like a textbook all the time, this usually means picking a dialect to drop into. My informal Japanese tends to stay Tokyo-standard in grammar but in tone is rather bokukko, for instance. It's marked in speech (although often the actual pronoun boku is used in internet Japanese by female blog authors who don't want to be explicitly female in text), but I am clearly a non-native speaker, and I feel it conveys a proper warning that I am not going to do well by Japanese standards of femininity. There are a few potential accents I could wind up with in Hebrew. American is fairly far down on the list; I'm usually pretty good at not sounding like a Yank. The letter Resh is most universally difficult for non-native speakers. I could probably use the French or German R and be understood (both voiced uvular fricative /ʁ/, the French one higher and more nasalized), but the Resh as given in the only explicit explanation I've found is actually supposed to be a uvular trill /ʀ/, which occurs more towards the hard palate than either of those, and with a rounder sounding chamber behind it. It comes so far forward that it is the closest thing I have ever seen to the theoretically-impossible velar trill. Wikipedia says this is an Ashkenazim thing, which explains why you hear it so much in Yiddish. I would definitely be understood if I used the Arabic alveolar trill /r/, which is noted as a variation common among the Sephardim, but it's also associated with Arabic-speaking refugees, and I feel like that might not be the accent I want if I'm going to be practicing this on Israeli friends. I've no idea which one the Eccentric uses; I gather he has one parent from either tradition and they lived in Jerusalem, so who the fuck knows. It's impossible to pick up from his English. He's made no effort to zero out his accent, but he has had three decades to nail the English retroflex alveolar approximant /ɻ/, and more or less does. Chet is voiced /χ/, and undotted-Khaf is unvoiced /x/, both of which I have.]

An irksome aspect of learning Hebrew is the transliteration system. There isn't one. You notice that my Japanese is italicized and the attempts at Hebrew are in single quotes? This is because the Japanese is brought straight across using a standard Japanese-to-Latin alphabet system used in some textbooks and on the internet. (There are other, more precise systems, but they involve diacritical marks that can't be typed on a pure-ASCII keyboard.) The Hebrew is... uh, approximate. There is no way to unambiguously transcribe Hebrew text in Latin letters that is immediately readable to people whose languages use the Latin alphabet. Duolingo doesn't even try. I type things using the Hebrew IME whenever possible, because I'm trying to learn to spell, but when the Eccentric explains things to me he does it with the regular QWERTY keyboard. It has quirks. Words whose transliteration ends in '-ah', as in the new year's greeting 'shanah tovah', are words that end in He, a letter which normally says /h/ but when word-final represents /a:/ for grammatical reasons. He also consistently writes his Vav as "U'" when it's used as a conjunction, even though it's pronounced /v/. My guess is that this is how it is taught in Israeli schools. There seems to be a system behind it, but it does not make sense unless you also read the original Hebrew.

This is all somehow working anyway, probably because I'm me. I made it to Day 18 of my first ever stab at learning Hebrew before I started scaring up podcasts. It only took me that long because I had to figure out how to search for the word for "Hebrew (language)" in Hebrew, because searching in transliteration gets you nothing. Day 20 I picked up a series of linguistic interviews put out by Leshoniada (לשוניאדה, a word which gave Google Translate shitfits, but which the Eccentric informs me is a portmanteau that comes out something like "Grammar-lympics"). The details escape me completely, because I lack vocabulary, but because Hebrew has a very regular stress pattern (word-final, almost always) individual terms are easy to pick out. Between that and a lot of straight-up imports from Greek, the topic of the first episode was easy to get.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2JTyn9x via IFTTT -------------------- Enjoy my writing? Consider becoming a Patron, subscribing via Kindle, or just toss a little something in my tip jar. Thanks!

0 notes