#Spinosaurine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

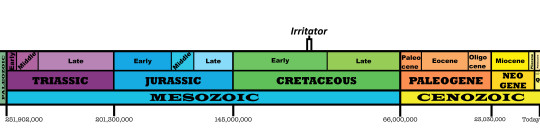

Irritator challengeri, a medium sized Spinosaurine dinosaur from Brazil during the early Cretaceous period, displays its strange pelican-like mouth which it likely used to swallow large fish whole. (113-110 Mya)

#irritator#paleoart#paleontology#dinosaur#dinosaurs#animal art#animals#animal#spinosauridae#brazil#cretaceous#pelican

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dinosaur tooth of an indeterminate spinosaurid, either cf. Spinosaurus sp. or Sigilmassasaurus brevicollis from the Dekkar Group in Talsint, Figuig, Morocco. The deposits in this area are likely the same age as the famous Kem Kem Group, but with a distinct marl matrix and black colored preservation. According to the papers written on the holotype of Spinosaurus by Ernst Stromer, the known teeth of the Egyptian Spinosaurus species should be completely smooth. It is possible that the Moroccan Spinosaurus species differs from the Egyptian Spinosaurus aegyptiacus or that these teeth with ridges belong to a different spinosaurid such as Sigilmassasaurus or an undescribed third taxon. Smooth crown morphologies closer to the holotype can also be found in these Moroccan deposits. This type of morphology shares more similarities to basal spinosaurines like Siamosaurus than to Spinosaurus.

#dinosaur#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#spinosaurus#sigilmassasaurus#spinosauridae#theropod#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#スピノサウルス#シギルマッササウルス#スピノサウルス科#恐竜#化石#古生物学

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patreon request for Magno/rome.and.stuff - Ichthyovenator laosensis!

Icthyovenator is a Spinosaurid from the Early Cretaceous of Laos. Known only from fragmentary material, it seems to be unique among Spinosaurids for the strange divot in its spine. (In this depiction, I’ve also added another small divot further up the back; however, we don’t have that much of the spine, so this is purely speculative.) This strange sail could have been used for display or species recognition. Like other spinosaurines, Icthyovenator was likely adapted for a semi-aquatic lifestyle, hunting aquatic prey like fish, amphibians, and small dinosaurs. Like Spinosaurus, it had unusually tall vertebral spines on its tail which likely aided in swimming.

While it certainly wasn’t snacking on sauropods (except possibly via scavenging), it lived alongside large ones like Tangvayosaurus. Trackways in the Grès Supérieurs Formation belong to sauropods, iguanodontians, and neoceratopsians, though fish and turtles make up the majority of this ancient habitat.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This was a nice warmup for Archovember, and it’s also good to have another Spinosaurid under my belt. I should redraw Baryonyx and give it a size chart. Maybe someday I’ll have enough to make a full spinosaurid comparison chart. 🤔

Btw, the request tier for Patreon starts at only $5 a month. 😉 Link is pinned at the top of my blog.

#Ichthyovenator laosensis#Ichthyovenator#Spinosaur#spinosaurid#theropods#dinosaurs#archosaurs#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#saurischians

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irritator challengeri

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: The One That Irritated

First Described By: Martill et al., 1996

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Megalosauroidea, Megalosauria, Spinosauridae, Spinosaurinae

Status: Extinct

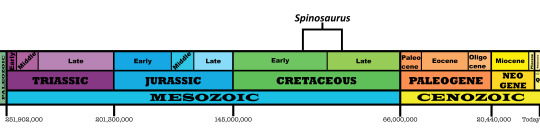

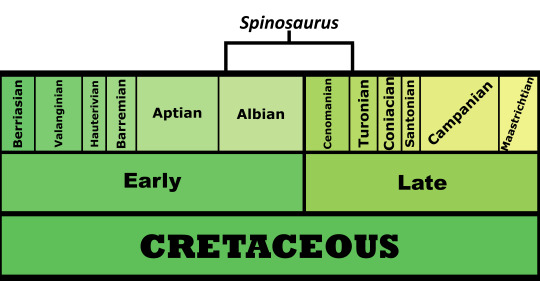

Time and Place: Between 110 and 108 million years ago, in the Albian of the Early Cretaceous

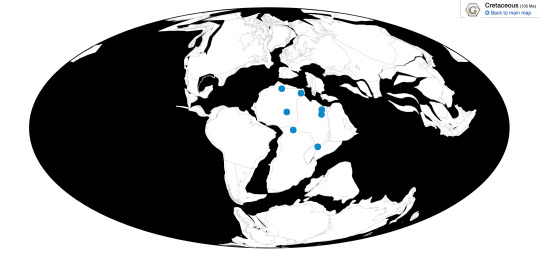

Irritator is known from the Romualdo Member of the Santana Formation in Brazil

Physical Description: Irritator was a Spinosaurid, so the weird crocodile-mimicking theropods that roamed the Cretaceous landscape across the Southern hemisphere (and some of Europe). Irritator, however, is not known from very much material, despite having loads written about it. It was one of the smaller members of the Spinosaur group, only about 7.5 meters long and not weigh more than one tonne - which may actually indicate it could have still had some sort of fluffy integument, though this still seems unlikely based on its ecology. As a Spinosaur, Irritator would have been fairly bulky, with a long and vaguely crocodilian skull. Its skull also featured a long thin crest going from the midline to the eye, where it flattened into a bulge - this was probably some sort of display structure. Little is known of the rest of its skeleton, but it is known to have had a long and well-clawed hand. It probably had some sort of sail on its back, but it probably was a shorter one, and whether or not its legs were a normal size is unknown.

By Alexander Vieira, CC BY-SA 4.0 (Irritator is on the far right, in green)

Diet: Irritator would have mainly fed upon fish and other aquatic organisms.

Behavior: Irritator, being a Spinosaur, spent most of its time in the water, swimming about and searching for food. Since it was rather small, it would have been able to fit in smaller streams of water than most of its other relatives. Though, since it probably still had fairly decent legs, it also would have spent a good amount of time on the land, surveying the shore for food and seeking out prey. Its long snout would then be used to grab fish and other animals from the water, using the lightweight instrument to grab food it might not be able to reach otherwise. While swimming, it would be able to use that snout to reach even more food than before, ducking its head underwater or doing the reverse to hide from land sources of prey. Its very powerful neck muscles would have also been extremely helpful in grabbing and holding onto thrashing prey.

By Fred Wierum, CC BY 3.0

Irritator was probably warm-blooded, and used its sail more for display than for keeping warm. This display structure may have been able to change color based on blood circulation or environment in order to send different messages to other members of the species. The crest on the center of the snout also probably served similar features, for displaying to one another. It seems likely that Irritator, like most other dinosaurs, took care of its young; but there is no evidence either way to support that hypothesis.

By PaleoGeekSquared, CC BY 3.0

Ecosystem: Irritator lived in the Romualdo Environment of Brazil, which was a basin of lakes surrounded by rivers and other wetland environments, filled to the brim with a wide variety of plantlife. Nearby was the burgeoning Atlantic Ocean, making this a Spinosaur’s favorite place of all. Here there were a wide variety of early flowering plants like magnolias, seagrasses, and lilies - all of which were associated heavily with this aquatic environment. There were many types of ray-finned fish, which would have been the primary source of prey for Irritator, as well as lobe-finned fish which would have also been decent sources of food. Sharks seem to have been rare. There were plenty of turtles too, including one of the earliest sea turtles Santanachelys. This was the land of extreme pterosaurs, including Anhanguera, Arirpesaurus, Barbosania, Brasileodactylus, Cearadacytlus, Maaradactylus, Santanadactylus, Tapejara, Thalassodromeus, Tropeognathus, Tupuxuara, and Unwindia. There was also a Notosuchian, Araripesuchus. There were other dinosaurs there too - the compsognathid Mirischia and the Tyrannosauroid Santanaraptor, which would have mainly fed on small animal prey.

By Scott Reid

Other: Irritator was found as part of the illegal fossil trade, initially mistake for a pterosaur, then a maniraptoran, before being finally identified as a spinosaur. The confusion surrounding this fossil - and the fact that the snout had been artificially elongated by the fossil traders - lead to its name. Its position within the Spinosaurs is well supported, and it seems to have been at least somewhat closely related to Spinosaurus itself, rather than Baryonyx on the other end of the family tree.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Allain, Ronan; Xaisanavong, Tiengkham; Richir, Philippe; Khentavong, Bounsou (2012-04-18). "The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (5): 369–377.

Amiot, R.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Wang, X.; Boudad, L.; Ding, Z.; Fourel, F.; Hutt, S.; Martineau, F.; Medeiros, A.; Mo, J.; Simon, L.; Suteethorn, V.; Sweetman, S.; Tong, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z. (2010). "Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods". Geology. 38 (2): 139–142.

Arden, T.M.S.; Klein, C.G.; Zouhri, S.; Longrich, N.R. (2018). "Aquatic adaptation in the skull of carnivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) and the evolution of aquatic habits in Spinosaurus". Cretaceous Research. In Press: 275–284.

Aureliano, Tito; Ghilardi, Aline M.; Buck, Pedro V.; Fabbri, Matteo; Samathi, Adun; Delcourt, Rafael; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Sander, Martin (2018-05-03). "Semi-aquatic adaptations in a spinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 90: 283–295.

Bantim, Renan A.M.; Saraiva, Antônio A.F.; Oliveira, Gustavo R.; Sayão, Juliana M. (2014). "A new toothed pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea: Anhangueridae) from the Early Cretaceous Romualdo Formation, NE Brazil". Zootaxa. 3869 (3): 201–223.

Barrett, Paul; Butler, Richard; Edwards, Nicholas; Milner, Andrew R. (2008-12-31). "Pterosaur distribution in time and space: An atlas". Zitteliana Reihe B: Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung Fur Palaontologie und Geologie. 28: 61–107.

Benson, R.B.J.; Carrano, M.T.; Brusatte, S.L. (2009). "A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 71–78.

Benyoucef, Madani; Läng, Emilie; Cavin, Lionel; Mebarki, Kaddour; Adaci, Mohammed; Bensalah, Mustapha (2015-07-01). "Overabundance of piscivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) in the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa: The Algerian dilemma". Cretaceous Research. 55: 44–55.

Bertin, Tor (2010-12-08). "A catalogue of material and review of the Spinosauridae". PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 7.

Bertozzo, F., B. Favaretto, M. Bon and FM Dalla Vecchia. 2013. The wallpaper of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Taquet, 1976 (Ornithischia, Ornithopoda) exhibited at the Natural History Museum of Venice: history of the find and perspectives for detailed studies [The paratype of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Taquet, 1976 (Ornithischia, Ornithopoda) exhibited at the Museum of Natural History of Venice: history of discovery and prospects for detailed studies]. Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of Venice 64 : 119-130

Bittencourt, Jonathas; Kellner, Alexander (2004-01-01). "On a sequence of sacrocaudal theropod dinosaur vertebrae from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Formation, northeastern Brazil". Arq Mus Nac. 62: 309–320.

Brito, Paulo; Yabumoto, Yoshitaka (2011). "An updated review of the fish faunas from the Crato and Santana formations in Brazil, a close relationship to the Tethys fauna". Bulletin of Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History and Human History, Ser. A. 9.

Buffetaut, E.; Ouaja, M. (2002). "A new specimen of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Tunisia, with remarks on the evolutionary history of the Spinosauridae" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 173 (5): 415–421.

Buffetaut, E.; Martill, D.; Escuillié, F. (2004). "Pterosaurs as part of a spinosaur diet". Nature. 430 (6995): 33.

Candeiro, C. R. A., A. G. Martinelli, L. S. Avilla and T. H. Rich. 2006. Tetrapods from the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian–Maastrichtian) Bauru Group of Brazil: a reappraisal. Cretaceous Research 27:923-946

Candeiro, C. R. A., A. Cau, F. Fanti, W. R. Nava, and F. E. Novas. 2012. First evidence of an unenlagiid (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Maniraptora) from the Bauru Group, Brazil. Cretaceous Research 37:223-226

Carrano, M. T., R. B. J. Benson, and S. D. Sampson. 2012. The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(2):211-300

Charig, A.J.; Milner, A.C. (1997). "Baryonyx walkeri, a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of London. 53: 11–70.

Cuff, Andrew R.; Rayfield, Emily J. (2013-05-28). "Feeding Mechanics in Spinosaurid Theropods and Extant Crocodilians". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e65295.

Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Buffetaut, Eric; Mendez, Marco A. (2005-12-30). "New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its size and affinities". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 888–896.

de Lapparent de Broin, F. (2000). "The oldest pre-Podocnemidid turtle (Chelonii, Pleurodira), from the early Cretaceous, Ceará state, Brasil, and its environment". Treballs del Museu de Geologia de Barcelona. 9: 43–95.

Evers, Serjoscha W.; Rauhut, Oliver W.M.; Milner, Angela C.; McFeeters, Bradley; Allain, Ronan (2015). "A reappraisal of the morphology and systematic position of the theropod dinosaur Sigilmassasaurus from the 'middle' Cretaceous of Morocco". PeerJ. 3: e1323.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2009. Theropod remains from the uppermost Cretaceous of Colombia and their implications for the palaeozoogeography of western Gondwana. Cretaceous Research 30:1339-1344

Figueiredo, R.G.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2009). "A new crocodylomorph specimen from the Araripe Basin (Crato Member, Santana Formation), northeastern Brazil". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 83 (2): 323–331.

Frey, E.; Martill, D.M. (1994). "A new Pterosaur from the Crato Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian) of Brazil". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 194: 379–412.

Furtado, M. R., C. R. A. Candeiro, and L. P. Bergqvist. 2013. Teeth of Abelisauridae and Carcharodontosauridae cf. (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from the Campanian- Maastrichtian Presidente Prudente Formation (southwestern São Paulo State, Brazil). Estudios Geológicos 69(1):105-114

Gaffney, Eugene S.; de Almeida Campos, Diogenes; Hirayama, Ren (2001-02-27). "Cearachelys, a New Side-necked Turtle (Pelomedusoides: Bothremydidae) from the Early Cretaceous of Brazil". American Museum Novitates. 3319: 1–20.

Gaffney, Eugene S.; Tong, Haiyan; Meylan, Peter A. (2009-09-02). "Evolution of the side-necked turtles: The families Bothremydidae, Euraxemydidae, and Araripemydidae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 300: 1–698.

Gibney, Elizabeth (2014-03-04). "Brazil clamps down on illegal fossil trade". Nature. 507 (7490): 20.

Hassler, A.; Martin, J.E.; Amiot, R.; Tacail, T.; Godet, F. Arnaud; Allain, R.; Balter, V. (2018-04-11). "Calcium isotopes offer clues on resource partitioning among Cretaceous predatory dinosaurs". Proc. R. Soc. B. 285 (1876): 20180197.

Henderson, Donald M. (2018-08-16). "A buoyancy, balance and stability challenge to the hypothesis of a semi-aquatic Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". PeerJ. 6: e5409

Hendrickx, C., and O. Mateus. 2014. Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal and dentition-based phylogeny as a contribution for the indentification of isolated theropod teeth. Zootaxa 3759(1):1-74

Hirayama, Ren (1998). "Oldest known sea turtle". Nature. 392 (6677): 705–708.

Holtz, Thomas; Molnar, Ralph E.; Currie, Philip (2004-06-12). "Basal Tetanurae". The Dinosauria: Second Edition. University of California Press. pp. 71–110.

Ibrahim, N.; Sereno, P.C.; Dal Sasso, C.; Maganuco, S.; Fabbri, M.; Martill, D.M.; Zouhri, S.; Myhrvold, N.; Iurino, D.A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–1616.

Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (1996). "First Early Cretaceous dinosaur from Brazil with comments on Spinosauridae". N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh. 199 (2): 151–166.

Kellner, A.W.A. (1996). "Remarks on Brazilian dinosaurs". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 39 (3): 611–626.

Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2000). "Brief review of dinosaur studies and perspectives in Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 72 (4): 509–538.

Kellner, A.W.A. (2001). "New information on the theropod dinosaurs from the Santana Formation (Aptian-Albian), Araripe Basin, Northeastern Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (supplement to 3): 67A.

Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2002). "The function of the cranial crest and jaws of a unique pterosaur from the early Cretaceous of Brazil". Science. 297 (5580): 389–392.

Kellner, A. W. A., S. A. K. Azevedo, E. B. Machado, L. B. Carvalho, and D. D. R. Henriques. 2011. A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcântara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 83(1):99-108

Lee, Yuong-Nam; Barsbold, Rinchen; Currie, Philip J.; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Lee, Hang-Jae; Godefroit, Pascal; Escuillié, François; Chinzorig, Tsogtbaatar (2014). "Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus". Nature. 515 (7526): 257–260.

Lopes, Reinaldo José (September 2018). "Entenda a importância do acervo do Museu Nacional, destruído pelas chamas no RJ". Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese).

Mabesoone, J.M.; Tinoco, I.M. (1973-10-01). "Palaeoecology of the Aptian Santana Formation (Northeastern Brazil)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 14 (2): 97–118.

Machado, E.B.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2005). "Notas Sobre Spinosauridae (Theropoda, Dinosauria)" (PDF). Anuário do Instituto de Geociências – UFRJ (in Portuguese). 28 (1): 158–173.

Machado, E.B.; Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2005). "Preliminary information on a dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) pelvis from the Cretaceous Santana Formation (Romualdo Member) Brazil". Congresso Latino-Americano de Paleontologia de Vertebrados. 2 (Boletim de resumos): 161–162.

Machado, E.B.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2008). "An overview of the Spinosauridae (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with comments on the Brazilian material". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28(3): 109A.

Martill, D. M., A. R. I. Cruickshank, E. Frey, P. G. Small, and M. Clarke. 1996. A new crested maniraptoran dinosaur from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Brazil. Journal of the Geological Society, London 153:5-8

Martill, David M. (2011). "A new pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous) of Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 236–243.

Martill, David; Frey, Eberhard; Sues, Hans-Dieter; Cruickshank, Arthur R.I. (2011-02-09). "Skeletal remains of a small theropod dinosaur with associated soft structures from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Formation of NE Brazil". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 37 (6): 891–900.

Mateus, Octávio; Araujo, Ricardo; Natario, Carlos; Castanhinha, Rui (2011-04-21). "A new specimen of the theropod dinosaur Baryonyx from the early Cretaceous of Portugal and taxonomic validity of Suchosaurus". Zootaxa: 54–68.

Medeiros, M. A. 2006. Large theropod teeth from the Eocenomanian of northeastern Brazil and the occurrence of Spinosauridae. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 9(3):333-338

Medeiros, Manuel Alfredo; Lindoso, Rafael Matos; Mendes, Ighor Dienes; Carvalho, Ismar de Souza (August 2014). "The Cretaceous (Cenomanian) continental record of the Laje do Coringa flagstone (Alcântara Formation), northeastern South America". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 53: 50–58.

Milner, Andrew; Kirkland, James (2007). "The case for fishing dinosaurs at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm". Utah Geological Survey Notes. 39 (3): 1–3.

Naish, D.; Martill, D.M.; Frey, E. (2004). "Ecology, Systematics and Biogeographical Relationships of Dinosaurs, Including a New Theropod, from the Santana Formation (?Albian, Early Cretaceous) of Brazil". Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 57–70.

Naish, D., and D. M. Martill. 2007. Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: basal Dinosauria and Saurischia. Journal of the Geological Society, London 164:493-510

Pêgas, R.V.; Costa, F.R.; Kellner, A.W.A. (2018). "New Information on the osteology and a taxonomic revision of the genus Thalassodromeus (Pterodactyloidea, Tapejaridae, Thalassodrominae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (2): e1443273.

Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (2003). The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. London: The Palaeontological Association.

Rayfield, Emily J.; Milner, Angela C.; Xuan, Viet Bui; Young, Philippe G. (2007-12-12). "Functional morphology of spinosaur 'crocodile-mimic' dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (4): 892–901.

Sales, Marcos A.F.; Lacerda, Marcel B.; Horn, Bruno L.D.; de Oliveira, Isabel A.P.; Schultz, Cesar L. (2016-02-01). "The 'χ' of the Matter: Testing the Relationship between Paleoenvironments and Three Theropod Clades". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0147031.

Sales, Marcos (2017). "Contribuições à paleontologia de Terópodes não-avianos do Mesocretáceo do Nordeste do Brasil" (in Portuguese). 1. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: 54.

Sales, Marcos A.F.; Schultz, Cesar L. (2017-11-06). "Spinosaur taxonomy and evolution of craniodental features: Evidence from Brazil". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0187070.

Sánchez-Hernández, B., M. J. Benton, and D. Naish. 2007. Dinosaurs and other fossil vertebrates from the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of the Galve area, NE Spain. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 249:180-215

Sayão, Juliana; Saraiva, Antonio; Silva, Helder; Kellner, Alexander (2011). "A new theropod dinosaur from the Romualdo Lagerstatte (Aptian-Albian), Araripe Basin, Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31: supplement 2: 187.

Sereno, P.C.; Beck, A.L.; Dutheuil, D.B.; Gado, B.; Larsson, H.C.; Lyon, G.H.; Marcot, J.D.; Rauhut, O.W.M.; Sadleir, R.W.; Sidor, C.A.; Varricchio, D.; Wilson, G.P.; Wilson, J.A. (1998). "A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from Africa and the evolution of spinosaurids". Science. 282 (5392): 1298–1302.

Serrano-Martínez, Alejandro; Vidal, Daniel; Sciscio, Lara; Ortega, Francisco; Knoll, Fabien (2015). "Isolated theropod teeth from the Middle Jurassic of Niger and the early dental evolution of Spinosauridae". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Sues, H.D.; Frey, E.; Martill, D.M.; Scott, D.M. (2002). "Irritator challengeri, a spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 535–547.

Witmer, L.M. 1995.The Extant Phylogenetic Bracket and the Importance of Reconstructing Soft Tissues in Fossils. in Thomason, J.J. (ed). Functional Morphology in Vertebrate Paleontology. New York. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–33.

Witton, Mark P. (2018-01-01). "Pterosaurs in Mesozoic food webs: a review of fossil evidence". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455 (1): 7–23.

Xu, X.; Currie, P.; Pittman, M.; Xing, L.; Meng, Q.; Lü, J.; Hu, D.; Yu, C. (2017). "Mosaic evolution in an asymmetrically feathered troodontid dinosaur with transitional features". Nature Communications. 8: 14972.

#Irritator challengeri#Irritator#Dinosaur#Spinosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Megalosaur#Water Wednesday#Piscivore#South America#Cretaceous#Spinosaurine#prehistoric life#paleontology#prehistory#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

im pissing my pants i just realised canines/felines are called that because you put -ine for subfamilies!!!! caninae!!! felinae!!!!! i JUST realised this oh my god!!

#riel.txt#i was thinkin abt spinosaurids and like#wait a minute... spinosaurine#Then Holy Fuck Canids Canine Felids Feline

1 note

·

View note

Text

There is no much introduction about this fella, the dude itself that carry fame in a cursed way for its taxonomy to its anatomy compared to any other theropod due to its still "disputed" aquatic lifestyle.

If you are wondering, this is suppose to be the S. aegyptiacus from Egypt that was obliterated on WWII, overall I'm taking some considerable opinions about what is valid as S. aegyptiacus.

My conclusion has been that only what was found in Bahariya and can be found and identified should be disputed to have the name, and the material is gone so the current status of all Moroccan specimens should be "cf. Spinosaurus sp." or "Spinosaurine indet." for the moment as not all the remains there doesn't have correlatives of belong to the same species except for being found in the same region and cannot be fully compared with the now missing holotype. Everything related to the investigation on Morroco needs further data.

Reconstruction based from skeletal by Dan Folkes

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

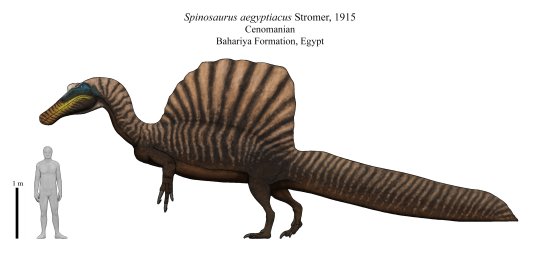

did all spinosaurids have short legs/were close to the ground? i usually only see paleoart of spinosaurus with short legs, and others like baryonyx, suchomimus and ichthyovenator i see with longer legs. does the leg length difference have any significance or is it just people not drawing them correctly?

Other spinosaurids did have normal-length legs! So far, it’s just Spinosaurus that has direct evidence of short legs, though it’s certainly possible that other spinosaurines like Oxalaia would have them too.

(Image by Jaime Headden)

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dinosaur tooth of an indeterminate spinosaurid, likely Suchomimus tenerensis from the Elrhaz Formation in Gadoufaoua, Niger. While it is likely Suchomimus, it lacks fluting typically seen in baryonychine teeth. Depending on the phylogenetic position of the dubious Cristatusaurus lapparenti, it may also potentially belong to this lesser known species. It is also possible it belongs to an undescribed spinosaurine.

#dinosaur#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#suchomimus#cristatusaurus#spinosauridae#baryonychinae#theropod#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#palaeoblr#スコミムス#クリスタトゥサウルス#スピノサウルス科#バリオニクス亜科#恐竜#化石#古生物学

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dinosaur tooth of a Suchomimus tenerensis from the Elrhaz Formation in Gadoufaoua, Niger. Compared to most spinosaurids which are notoriously fragmentary, Suchomimus is known from relatively complete material. The teeth of baryonychines like Suchomimus still retain very fine serrations often lost in the more derived spinosaurines like Spinosaurus. The contemporary spinosaurid, Cristatusaurus lapparenti may or may not be synonymous with this species.

#dinosaur#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#suchomimus#cristatusaurus#spinosauridae#baryonychinae#theropod#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#fossil friday#fossilfriday#スコミムス#クリスタトゥサウルス#スピノサウルス科#バリオニクス亜科#恐竜#化石#古生物学

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dinosaur tooth of the spinosaurid tooth taxon, Siamosaurus suteethorni from the Sao Khua Formation in Khon Kaen Province, Thailand. Unfortunately, this tooth has seen better days with much of the enamel worn away with a few repairs. Similar morphologies have been found in Laos, China, and Japan. These spinosaurine teeth have occasionally been mistaken for plesiosaurs, namely the pliosaur Sinopliosaurus.

#dinosaur#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#siamosaurus#sinopliosaurus#spinosauridae#theropod#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#fossil friday#fossilfriday#シアモサウルス#シノプリオサウルス#スピノサウルス科#恐竜#化石#古生物学

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

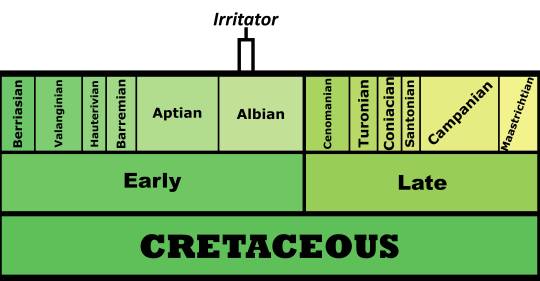

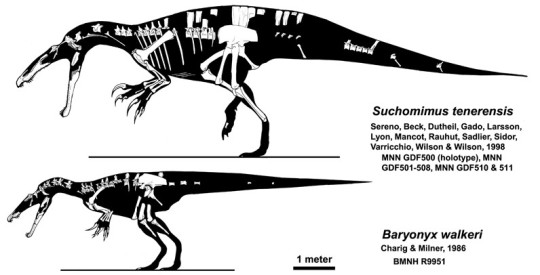

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Spined Reptile

First Described By: Stromer, 1915

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Megalosauroidea, Megalosauria, Spinosauridae, Spinosaurinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Spinosaurus lived between 112 and 93.5 million years ago, from the Albian of the Early Cretaceous until the Turonian-Cenomanian boundary of the Late Cretaceous

Spinosaurus is known from a variety of locations, most notably the Bahariya Formation and the Kem Kem Beds, specifically the Afous and Ifezouane Formations in Kem Kem. It has also been found in the Grés de Gaba Member of the Koum Formation, the Echkar Formation, the Chenini Member of the Aïn el Guettar Formation, the Mut Member of the Quseir Formation, and the Lubur Sandstone Formation. These locations are spread out over Camaroon, Niger, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, and Kenya; though the more southern locations such as Kenya are dubious.

Physical Description: Oh Spinosaurus. A mystery throughout the past one hundred and four years, one that we still have not somehow managed to solve. Despite many breaks in the case, there is always another controversy. Spinosaurus is the longest known theropod - the group of meat-eating and bird dinosaurs - and potentially the largest, though it is not the most heavy in weight (that is still Tyrannosaurus). A variety of estimates as to its size are out there, and it’s kind of a mystery as to its full size, because decent remains of the entire skeleton are not exactly well known.

Size of Spinosaurus and other large predatory dinosaurs: Carcharodontosaurus, Giganotosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus, by Dinoguy2, CC BY-SA 3.0

Size of the smallest, best known, and largest specimens of Spinosaurus, by Marco Auditore, CC BY 4.0

What we know about the physical appearance of Spinosaurus is fairly limited. We do know that it had a long snout, much like that of a modern crocodilian. The upper jaw featured a crescent dip towards the tip, which was matched by a rounded tip on the lower jaw that fit into it. The teeth around this space point inward on the upper jaw and outward on the upper jaw, allowing for catching slippery food tightly in the jaws - pointing to fish being the main food source for Spinosaurus. The skull also features a small crest in front of the eyes.

By Steveoc 86, CC BY 2.5

Along the back of Spinosaurus are the most famous feature of the dinosaur - extremely long neural spines. All vertebrae have spines coming out the back of each individual bone, but on Spinosaurus they extend far beyond what is usually seen in dinosaurs (and other animals). Many other dinosaurs also have extended spines, as do some non-dinosaurs - famously, animals such as Edaphosaurus, Dimetrodon, Ouranosaurus, and others. What these spines are used for, however, can vary. Some animals with large spines use them to support a large hump of fat, supported by the spines for a more sturdy structure. These spines tend to be more thick and closely spaced than those of Dimetrodon, which is known to have a sail. Spinosaurus, awkwardly enough, falls somewhere in between known humped and known sailed organisms. It has thicker spines than Dimetrodon, but not as thick as humped mammals. Correlates on the spines also indicate that skin was wrapped tightly around the bone, rather than fat. So, while the jury is still out, a sail seems more likely than a hump for now.

One recent hypothesis as to the structure of the sail indicates that the sail extended down to the base of the tail, and had a large dip in the middle with higher portions of the sail on either side. While there has been some controversy back and forth on this recent hypothesis, that sail structure seems to have stuck. Spinosaurus in general had a fairly elongate body, with a stretched out torso, a long neck, and a long tail. In addition, the tail was fairly narrow, like that of a thresher shark.

By Charles Nye

Spinosaurus had long arms, ending in sharply curved claws on each of its three fingers. These were very robust limbs, especially for a theropod. The hindlimbs of Spinosaurus are more so controversial - recent estimates say that the pelvis is at a lower angle than in other dinosaurs, and that the legs are extremely short for a theropod dinosaur. However, this has been extensively criticised, and the estimates have been called into question as poorly scaled. Still, many researchers agree with the original hypothesis of this recent study, and say that yes, the legs were that ridiculous looking. So, the jury is once again out - either Spinosaurus was especially squat for a theropod, or Spinosaurus was just a little squat for a theropod. Personally, I favor the former, at least for now.

Spinosaurus was so large, and lived in such a warm climate, it probably didn’t have feathery covering. If it did, it would have mostly likely just been for display - though, how much more display Spinosaurus needed, I’m not sure. It was pretty fancy for a dinosaur. Alternatively, because it was aquatic, it might have used feathers like modern ducks do - though that seems unlikely, given it’s basal (far away from birds) position on the theropod tree.

By Jordiferrer, CC BY-SA 4.0

Diet: Spinosaurus seems to be primarily a piscivore, with jaws designed to catch fish and withstand the force created by catching fish more so than the force created by holding down terrestrial prey. That being said, Spinosaurus probably also ate land-based prey as well.

Behavior: The biggest question with respect to Spinosaurus is whether or not it was semiaquatic. There is data present for either hypothesis. On the one hand, the ratio of oxygen isotopes - forms of oxygen - present in the teeth indicate that Spinosaurus was semiaquatic, similar to modern turtles and crocodilians and different from decidedly land-based, contemporary predators like the large theropod Carcharodontosaurus. It had a jaw built for grabbing fish, as stated above; and weird limb proportions that have been repeatedly suggested to indicate it spent more time in water than out of it. This hypothesis is also bolstered by the fact that it had a tail much like a thresher shark, which would have aided in swimming through the water, and potentially stunning fish prior to catching them.

Still, that’s not the end of the story. Studies on buoyancy of Spinosaurus indicate that it would have had a rather difficult time sinking, an important trait for a water-based predator. In addition, this study indicates that it still would have been okay walking on land. While this study is vital in putting the picture together, it was somewhat flawed - it based its estimations on reconstructions, rather than on studying the bones directly; and even then its conclusions weren’t that strongly backed. So which is it?

By José Carlos Cortés

Right now, our best guess seems to be a mixed lifestyle. While Spinosaurus probably did spend some time on land and, furthermore, ate land-based food from time to time, it was definitely adapted for spending time near the water. Whether that means it would swim through the water or stand at the shore is unclear. It’s possible it did all three - the large claws on its hands would have been excellent in catching fish swimming through the water like modern bears; it did have a good slapping tail so it could swim through deeper waterways to get food when needed; and in drier times of the year, it could hunt for land-based food. This would all allow it to be opportunistic in a good way - specializing in one, less-exploited food source in its environment, but able to take advantage of what it could. This was necessary, since most of its environments were ridiculously predator heavy.

One thing that is clear about Spinosaurus is that it was not a quadruped - even with its weirdly forward-tilting body posture, it would have been able to support its weight on its hind limbs and, furthermore, its front limbs were not built for holding its weight. It wouldn’t, however, have been the best walker on land - personally, I think it probably would have waddle around, much like a living duck - able to get to where it needs to go, but not very gracefully while doing it. And, much like ducks, it wouldn’t have been very graceful at swimming either - without being able to dive very well, it would have probably stuck to the surface, much like living ducks.

Basically Spinosaurus was a huge, terrifying croco-duck with a sail.

Speaking of the sail - what was it for? Was it even a sail?

Going with the idea of Spinosaurus having a sail, there are a lot of hypotheses as to what it could be used for. Given dinosaurs such as Spinosaurus were, on the whole, warm-blooded, it seems unlikely that the sail was used for regulating body temp. It may have allowed for faster movement through the water, like the sail of a sailfish - which would have helped Spinosaurus catch food more easily, since it might not have been that great at sinking. It also could have aided in making turns and moving rapidly while attacking fish, much like adaptations seen in the thresher shark and other analogues. The sail, tail, and neck could have all been used together to attack fish and other aquatic food.

By Joschua Knüppe, CC BY 4.0

Alternatively, the sail - in conjunction with the crest - was probably used for display, regardless of other possible functions. Such a ridiculous looking feature in dinosaurs is, nine times out of ten, for sex and communication. I mean, just remind yourself that dinosaurs are all extinct peacocks, and you get the idea. Spinosaurus probably could have had a brilliantly patterned and colored display on its sail, to make it look fancier for other Spinosaurus, and it may have even differed in coloration by sex. THe little crest on the top of the head probably served a similar function.

If the sail was actually a hump? Though this seems less likely, this could have allowed for the storing of energy, especially during long dry spells when food was not plentiful. It also could have helped to shield Spinosaurus from extreme heat in the equatorial climate.

Spinosaurus probably wouldn’t have been the most social of animals, given the crowded nature of its environment, though it seems unlikely that it wouldn’t have taken care of its young - since most dinosaurs did so. In fact, since semi-aquatic archosaurs today take care of their young - water birds and crocodilians - it seems likely that Spinosaurus would have too. It’s probable that it would have nested near waterways. Baby spinosaurus remains are known, but they’re fragmentary. As for other social groups, it was a common dinosaur in some environments and more rare in others, so it probably didn’t associate with others of its species much.

By Durbed, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ecosystem: Spinosaurus appears to have spread out over a giant range of North Africa, across the middle Cretaceous, with a variety of different environments. Still, it seems likely that Spinosaurus would have associated mainly with mangrove forests and on tidal flats and channels, which would have been extremely full of waterways for Spinosaurus to feed in. Then, during the dry season, it would have switched to more land-based prey, as the environment turned to more scrubland and dry floodplain.

In the original Bahariya Formation of Egypt, from between 100 and 95 million years ago, Spinosaurus lived alongside other large predatory dinosaurs such as Carcharodontosaurus, Deltadromeus, and Bahariasaurus. There were huge titanosaurs - the 15 meter long Aegyptosaurus and the 26 meter long Paralititan. Sigilmassasaurus, whatever sort of Spinosaur it was, was also present. There was a variety of conifers, water ferns, and tree ferns - indicating the climate switched from a swamp forest to a drier environment real quick, potentially due to fluctuations from season to season. There was also a wide variety of molluscs, crustaceans, insects, and a truly spectacular number of fish - both sharks and bony fish. There were turtles and some of the earliest sea snakes - Simoliophys. Finally, there were a variety of crocodylomorphs, which were probably the main competitors of Spinosaurus.

Slightly more south in Egypt, Spinosaurus is known from the Mut Member of the Quseir Formation. Here there are a variety of lungfish, indicating a more muddy environment than the Bahariya; sharks, bony fish, and other water-dwelling creatures. Carcharodontosaurus was also probably present here, though neither come from the same time as the later titanosaur Mansourasaurus.

In Tunisia, Spinosaurus is mainly known from the Chenini Member of the Aïn el Guettar Formation, where it shared an environment with Carcharodontosaurus, a variety of lungfish, many ray-finned fish, and sharks to boot. There were also other dinosaurs present, as well as crocodylomorphs, but they haven’t been named specifically.

By ДиБгд, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Kem Kem Beds were another major ecosystem of Spinosaurus, with Spinosaurus mainly known from the Chenini Member of the formation. This environment was from Morocco, and a little later in time than the Bahariya Formation. Here, Spinosaurus also lived alongside Carcharodontosaurus, Deltadromeus, and Sigilmassasaurus, but it also lived alongside the theropods Sauroniops and Inosaurus, and the sailed sauropod Rebbachisaurus, rather than any titanosaurs. This was probably also a flooding river ecosystem, as it is filled with a variety of turtles, crocodylomorphs, and fish, including extremely large species like Onchopristis. Between that, and aquatic crocodylomorphs like Elosuchus, it is clear that there was extensive water in this habitat, though there isn’t a lot of plant material known. There were also a lot of pterosaurs, which may have also been food sources for the large theropods of the area - pterosaurs such as Alanqa, Siroccopteryx, Colobrhynchus, and Xericeps, as well as unnamed species. These come from the Aoufous Formation primarily, though they can be found in other parts of the Kem Kem Beds such as the Ifezouane Formation. Ultimately, the later Ifezouane was very similar to the Aoufous.

Camaroon also featured Spinosaurus, specifically in the Grés de Gaba Member of the Koum Formation. However, this is extremely suspect - it’s older than the other formations and features creatures that decidedly did not live in the same locations as Spinosaurus, such as the sailed Ouranosaurus. So, this is a question, and one that I doubt in the extreme.

In Niger, the Echkar Formation also has possible Spinosaurus remains, though these are dubious too - just less so, because there’s also the common friend Carcharodontosaurus, as well as dinosaurs such as Rebbachisaurus, Bahariasaurus, and Aegyptosaurus that live with Spinosaurus elsewhere. There’s also Spinostropheus and Rugops, as well as a variety of land and water-dwelling crocodylomorphs. Plus, there were many lungfish for Spinosaurus to feed upon.

By Ripley Cook

Finally, there’s a dubious occurrence of Spinosaurus in the Lubur Sandstone Formation of Kenya. This is a poorly known ecosystem in general, with very poorly known theropod, ornithischian, and sauropod scraps, though a titanosaur is probably present in the location. So, that one is up in the air for Spinosaurus as well.

Other: Spinosaurus shares a complicated taxonomic status with Sigilmassasaurus, a Spinosaurine from the same time and general location. Though Spinosaurus is, of course, its own dinosaur, thanks to the fact that the original specimens were destroyed in World War II, it’s hard to tell apart whether or not the fossils since assigned to Spinosaurus are actually Spinosaurus or belong to other types of dinosaurs. Thus, it is entirely possible that this entire article is actually about Sigilmassasaurus. Alternatively, Sigilmassasaurus might just be a part of Spinosaurus. I don’t know. It’s a mess. We can blame fascism for this mess. For now, let’s assume they’re two different things, and what I talked about above is Spinosaurus. As for other issues of classification, Spinosaurus is a Megalosauroid - a group of middle-of-the-road theropods which featured many that were associated with shoreline ecosystems, though Spinosaurus was definitely the weirdest of the bunch.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the cut

Amiot, R., X. Wang, C. Lécuyer, E. Buffetaut, L. Boudad, L. Cavin, Z. Ding, F. Fluteau, A. W. A. Kellner, H. Tong, F. Zhang. 2010. Oxygen and carbon isotope compositions of middle Cretaceous vertebrates from North Africa and Brazil: Ecological and environmental significance. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 297(2):439-451

Arden, T. M. S., C. G. Klein, S. Zouhri, N. R. Longrich. 2018. Aquatic adaptation in the skull of carnivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) and the evolution of aquatic habits in Spinosaurus. Cretaceous Research 93: 275 - 284.

Bailey, J. B. 1997. Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs? Journal of Paleontology 71 (6): 1124 - 1146.

Bates, K. T., P. L. Manning, D. Hodgetts, W. I. Sellers, I. William. 2009. R. Beckett, ed. Estimating Mass Properties of Dinosaurs using Laser Imaging and 3D Computer Modelling. PLoS ONE 4 (2): e4532.

Benton, M. J., S. Bouaziz, E. Buffetaut, D. Martill, M. Ouaja, M. Soussi, C. Trueman. 2000. Dinosaurs and other fossil vertebrates from fluvial deposits in the Lower Cretaceous of southern Tunisia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 157 (3-4): 227 - 246.

Bouaziz, S., E. Buffetaut, M. Ghanmi, J.-J. Jaeger, M. Martin, J.-M. Mazin, H. Tong. 1988. Nouvelles découvertes de vertébrés fossiles dans l'Albien du sud tunisien [New discoveries of fossil vertebrates in the Albian of southern Tunisia]. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 8e série 4(2):335-339

Brusatte, S., P. C. Sereno. 2007. A new species of Carcharodontosaurus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Cenomanian of Niger and a revision of the genus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(4):902-916

Buffetaut, E., Y. Dauphin, J.-J. Jaeger, M. Martin, J.-M. Mazin, H. Tong. 1986. Prismatic dental enamel in theropod dinosaurs. Naturwissenschaften 73 (6): 326 - 327.

Buffetaut, E. 1989. New remains of the enigmatic dinosaur Spinosaurus from the Cretaceous of Morocco and the affinities between Spinosaurus and Baryonyx. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte 2: 79 - 87.

Buffetaut, E. 1992. Remarks on the Cretaceous theropod dinosaurs Spinosaurus and Baryonyx. Neues ahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte 2: 88 - 96.

Buffetaut, E., M. Ouaja. 2002. A new specimen of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Tunisia, with remarks on the evolutionary history of the Spinosauridae. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 173 (5): 415 - 421.

Carrano, M. T., R. B. J. Benson, S. D. Sampson. 2012. The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(2):211-300

Catuneanu, O., M. A. Khalifa, H. A. Wanas. 2006. Sequence stratigraphy of the Lower Cenomanian Bahariya Formation, Bahariya Oasis, Western Desert, Egypt. Sedimentary Geology 190 (1-4): 121 - 137.

Cau, A. 2014. Spinosaurus Revolution, Episodio IV: Una soluzione a tutti gli enigmi?

Cau, A. 2014. Spinosaurus Revolution, Episodio VI: Sigilmassasaurus vs. Spinosaurus: una battaglia tafonomica.

Churcher, C. S., D. A. Russell. 1992. Terrestrial vertebrates from Campanians strata in Wadi el-Gedid (Kharga and Dakleh Oases), western desert of Egypt. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 12(3, suppl.):23A

Churcher, C. S., G. De Iuliis. 2001. A new species of Protopterus and a revision of Ceratodus humei (Dipnoi: Ceratodontiformes) from the Late Cretaceous Mut Formation of eastern Dakhleh Oasis, Western Desert of Egypt. Palaeontology 44(2):305-323

Cuff, A R., E. J. Rayfield. 2013. Feeding Mechanics in Spinosaurid Theropods and Extant Crocodilians. PLoS ONE 8 (5): e65295.

Dal Sasso, C., S. Maganuco, E. Buffetaut, M. A. Mendez. 2005. New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its size and affinities. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25(4):888-896

Evans, S. E., M. Manabe. 1999. Early Cretaceous lizards from the Okurodani Formation of Japan. Geobios 32(6):889-899

Evers, S. W., O. W. M. Rauhut, A. C. Milner, B. McFeeters, R. Allain. 2015. A reappraisal of the morphology and systematic position of the theropod dinosaur Sigilmassasaurus from the “middle” Cretaceous of Morocco. PeerJ 3: e1323.

Gimsa, J., R. Sleigh, U. Gimsa.2016. The riddle of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus’ dorsal sail. Geological Magazine 153 (3): 544 - 547.

Glut, D. F. 1982. The Ne wDinosaur Dictionary. Secaucus, N. J. Citadel Press. 226 - 228.

Gradstein, F. M., J. G. Ogg, A. G. Smith. Eds. 2004. A Geologic Time Scale. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. 380.

Harris, J. M., D. A. Russell. 1986. Preliminary notes on the occurrence of dinosaurs in the Turkana Grits of northern Kenya. 1-11

Hartman, S. 2014. There’s something fishy about Spinosaurus. Skeletaldrawing dot com.

Hasegawa, Y., G. Tanaka, Y. Takakuwa, S. Koike. 2010. Fine sculptures on a tooth of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Morocco. Bulletin of Gunma Museum of Natural History 14: 11 - 20.

Henderson, D. M. 2018. A buoyancy, balance, and stability challenge to the hypothesis of a semi-aquatic Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda). PeerJ 6: e5409

Hendrickx, C., O. Mateus, E. Buffetaut. 2016. Morphofunctional Analysis of the Quadrate of Spinosauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and the Presence of Spinosaurus and a second Spinosaurine Taxon in the Cenomanian of North Africa. PLoS One 11 (1): e0144695.

Holtz, T. R. 2012. Dinosaurs: The Most complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.

Ibrahim, N., P. C. Sereno, C. Dal Sasso, S. Maganuco, M. Fabri, D. M. Martill, S. Zouhri, N. Myhrvoid, D. A. Lurino. 2014. Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur. Science 345 (6204): 1613 - 1616.

Kellner, A. W. A., B. J. Mader. 1997. Archosaur teeth from the Cretaceous of Morocco. Journal of Paleontology 71 (3): 525 - 527.

Kellner, A. W. A., S. A. K. Azevedo, E. B. Machado, L. B. Carvalho, D. D. R. Henriques. 2011. A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcântara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 83(1):99-108

Jacobs, L. L., D. A. Winkler, E. M. Gomani. 1996. Cretaceous dinosaurs of Africa: examples from Cameroon and Malawi. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 39(3):595-610

Lapparent, 1960. Les dinosauriens du "Continental intercalaire" du Sahara central. Memoirs of the Geological Society of France. 88A, 1-57.

Le Loeuff, J., E. Buffetaut, G. Cuny, Y. Laurent, M. Ouaja, C. Souillat, D. Srarfi, H. Tong. 2000. Mesozoic continental vertebrates of Tunisia. 5th European Workshop on Vertebrate Palaeontology, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Geowissenschaften Abteilung. Program. Abstracts. Excursion Guides 45

Maganuco, S., C. Dal Sasso. 2018. The smallest biggest theropod dinosaur: a tiny pedal ungual of a juvenile Spinosaurus from the Cretaceous of Morocco. PeerJ 6: e4785.

Medeiros and Schultz, 2002. A fauna dinossauriana da Laje do Coringa, Cretáceo médio do Nordeste do Brasil. Arquivos do Museu Nacional. 60(3), 155-162.

Mortimer, M. 2014. Spinosaurus surprise.

Naish, D, P. Barrett. 2016. Dinosaurs: How they Lived and Evolved. London Museum of Natural History, London, United Kingdom.

National Geographic. River Monster: 50 - Foot Spinosaurus.

Rauhut, O. W. M. 2003. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Special Papers in Palaeontology 69: 1 - 213.

Russell, D. A. 1996. Isolated dinosaur bones from the Middle Cretaceous of the Tafilalt, Morocco. Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 4e série, section C 18(2-3):349-402

Sereno, P. C., D. B. Dutheil, M. Iarochene, H. C. E. Larsson, G. H. Lyon, P. M. Magwene, C. A. Sidor, D. J. Varricchio, J. A. Wilson. 1996. Predatory dinosaurs from the Sahara and Late Cretaceous faunal differentiation. Science 272:986-991

Sereno, P. C., A. L. Beck, D. B. Dutheil, B. Gado, H. C. E. Larsson, G. H. Lyon, J. D. Marcot, O. W. M. Rauhut, R. W. Sadleir, C. A. Sidor, D. D. Varricchio, G. P. Wilson, J. A. Wilson. 1998. A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from Africa and the evolution of spinosaurids. Science 282:1298-1302

Sereno, P. C., J. A. Wilson, J. L. Conrad. 2004. New dinosaurs link southern landmasses in the mid-Cretaceous. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 271(1546):1325-1330

Smith, J. B., M. C. Lamanna, K. J. Lacovara, P. Dodson, J. R. Smith, J. C. Poole, R. Giegengack, Y. Attia. 2001. A giant sauropod dinosaur from an Upper Cretaceous mangrove deposit in Egypt. Science 292 (5522): 1704 - 1706.

Smith, J. B., M. C. Lamanna, H. Mayr, K. J. Lacovara. 2006. New information regarding the holotype of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus Stromer, 1915. Journal of Paleontology 80 (2): 400 - 406.

Stromer, E. 1915. Results of research trips by Prof. E. Stromer in the deserts of Egypt. II. Vertebrate remains of the Baharîje stage (lowest Cenomanian). 3. The original of the Theropod Spinosaurus aegyptiacus nov. gen., nov. spec. Treatises of the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences Mathematical-physical class Treatise 28 (3) : 1-31

Stromer, E. 1934. Die Zähne des Compsognathus und Bemerkungen über das Gebiss der Theropoda [The teeth of Compsognathus remarks on the dentition of the Theropoda]. Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, Abteilung B: Geologie und Paläontologie 1934:74-85

Taquet, P., D. A. Russell. 1998. New data on spinosaurid dinosaurs from the Early Cretaceous of the Sahara. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences, Série IIA 327 (5): 347 - 353.

Von Huene, F. R. 1926. The carnivorous saurischia in the Jura and cretaceous formations principally in Europe. Rev. Mus. La Plata 29: 35 - 167.

Weishampel, D. B., P. M. Barret, R. A. Coria, J. Le Loeuff, X. Xu, X. Zhao, A. Sahni, E. M. P. Gomani, C. R. Noto. 2004. Dinosaur Distribution. In Weishampel, D. B., P. Dodson, H. Osmólska. The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press: 517 - 606.

Witton, M. 2014. The Spinosaurus hindlimb controversy: a detailed response from the authors. Markwitton Blogspot.

Witze, A. 2014. Swimming Dinosaur found in Morocco. Nature News.

#spinosaurus#dinosaur#megalosaur#spinosaurus aegyptiacus#palaeoblr#factfile#dinosaurs#prehistoric life#paleontology#prehistory#spinosaurine#cretaceous#africa#carnivore#piscivore#water wednesday#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

874 notes

·

View notes