#Speedway Avenue

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Now you will get bank linked residential property in Yamuna Expressway and that too within your budget?

If you are searching for bank linked residential property then www.apexspeedways.com/ will be the best option for you. with. Our team is especially waiting for you. If you want to take a loan for your home then you can book now at Speedway Avenue. Speedway Avenue Yamuna Expressway offers 2/3/4 BHK apartments with prime location, luxurious amenities and commitment to sustainability, it is a perfect blend of comfort and style.

0 notes

Text

Buy 2/3/4 BHK Apartments in Speedway Avenue Yamuna Expressway

Speedway Avenue is one of the affordable and best residential societies in Yamuna Expressway. Many people dream of living in their own home. If you also have the same dream then you should come to Speedway Avenue Yamuna Expressway Project as soon as possible because it is giving you a golden opportunity and that too within your budget. Apex Speedway Avenue offers 2/3/4 BHK apartments with size range – 1150 to 2365 sq.ft. As the project sets new standards of modern living, residents can truly live lives to the fullest. For more information related to this project, visit the official website of Speedway Avenue.

0 notes

Text

Speedway Avenue Yamuna Expressway Great Option to Live

Speedway Avenue is one of the most luxurious residential projects on Yamuna Expressway. And its location is Sector 25 Yamuna Expressway. Speedway Avenue Yamuna Expressway offers independent 2/3/4 BHK apartments with its prime location, luxurious amenities and commitment to sustainability, it is the perfect blend of comfort and style. https://www.apexspeedways.com/

1 note

·

View note

Text

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐅𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐠 𝐒𝐨𝐥𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐔.𝐒. – 𝐆𝐚𝐢𝐥 𝐖𝐢𝐬𝐞’𝐬 𝐑𝐢𝐝𝐞 𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐇𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲

In the spring of 1964, 22-year-old Gail Wise was a third-grade teacher in Berkeley, Illinois, but little did she know, she was about to make history.

On April 15, 1964, Gail and her father walked into Johnson Ford on Cicero Avenue in Chicago, searching for the perfect convertible.

The family had always driven Fords—her father owned a ’57 Fairlane and a ’63 Thunderbird, so Gail knew exactly what she wanted. There was just one problem: there were no convertibles on the showroom floor.

Seeing her disappointment, the salesman took a chance and showed her something hidden in the back, under a tarp. What he revealed was none other than a "Skylight Blue" Ford Mustang convertible—the first of its kind.

The catch? It wasn’t supposed to be sold for two more days until after the official unveiling at the New York World’s Fair. No test drives allowed either. But Gail didn’t need one. The moment she saw it, she knew it was hers.

The price tag? $3,447.50. Her salary at the time? Just $5,000 a year. But with a loan from her father, Gail became the very first person in the United States to buy a Ford Mustang—two days before anyone else even saw one.

As she drove out of the showroom, heads turned, and people waved. It was as if she had become a celebrity overnight. The next day, she drove her Mustang to school, where the seventh and eighth graders swarmed the car, amazed at what they were seeing.

For the next 15 years, that Mustang was Gail’s pride and joy. She married Tom Wise in 1966, and they had four kids together.

The car became part of their family’s daily life, from McDonald’s runs with the kids to joyrides around town. Back in those days, seatbelts were only in the front seats, and the passenger seat didn’t even adjust.

Despite its quirks, the Mustang was an icon on the road, but after years of Chicago winters, the car began to show its age. Rust took over, and the engine started having problems.

By the late '70s, the Mustang’s glory days seemed over. Tom pushed it into the garage, planning to fix it the next week, but that week turned into 27 years. Gail, ready to move on, suggested scrapping the car, but Tom refused, calling it his retirement project.

In 2005, after retiring at 60, he finally began the long process of restoring the car. He stripped it down to almost nothing, leaving just the four wheels and the steering wheel before handing it off to specialists for bodywork and engine repair.

It took about a year and $35,000, but Tom brought the Mustang back to life, adding a custom horn that sounds like a whinnying horse for good measure.

When the restoration was complete, Tom started researching the car’s history. That’s when they realized Gail’s Mustang was the very first one ever sold in the U.S. It wasn’t long before Ford took notice.

The couple was invited to Mustang events, including the 10 millionth Mustang celebration in Dearborn, and even got the chance to drive the car at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

Though they don’t drive it much now, the Mustang remains a family treasure. Gail and Tom’s four kids haven’t expressed much interest in keeping it, so it will likely be sold when the time comes.

But for now, the first Mustang ever sold in the U.S. sits proudly in their garage, a testament to one couple’s journey through life and the car that’s been with them every step of the way.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ride the Third Avenue El way uptown and you will find yourself in the wide open spaces of Harlem.

Just to the east beyond the bluffs and along the river there is a wide two-mile stretch of road known as the Harlem River Speedway.

Here you can bet on the trotters, watch the carriage races, try out that new pacer, observe the action from the Clubhouse terrace, or just stroll on the promenade, taking in the view and enjoying the breeze from the river. No horseless carriages please.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

PHILADELPHIA (CBS) – A 24-hour gas station in Germantown is blasting opera music at all hours of the day. Neighbors have mixed reactions to the music.

Since Tuesday, a Speedway in Germantown has been playing opera music.

CBS News Philadelphia hasn't heard back from Speedway's corporate offices on why exactly they've decided to do this, but some customers think it's helping deter loitering.

While customers fill up on Chelten Avenue, French tunes of Léo Delibes' Lakmé opera blast over the speakers.

People are either confused or amazed by the sound.

"I've never heard it before at a public place like this," Donald Charles, a gas station customer, said. "That's something."

"I think it's nice," Verna Tarpley, a Germantown resident, said. "It's really nice. The first time I've heard it."

While others are wishing they could just press skip.

"I think they need to change the music," Spencer McLeod, a Mt. Airy resident, said. "It was really loud and then, the echo, it was going like three blocks down over."

Gas station employees won't comment on why they play the music, but CBS News Philadelphia has seen other businesses use this tactic before. They use it as a way to deter loitering.

Several customers believe the new playlist might help with the issue.

"What a creative approach, because we have too much conflict in our community," April Warwick, a Germantown resident, said. "Music soothes the savage beast."

"That'd be good if it kept crime down or loitering," McLeod said.

Some customers and residents in the area say the music was too loud so employees have turned it down.

CBS News Philadelphia also checked in with the businesses across the street and they say the music hasn't been an issue for them.

#nunyas news#there's the hummingbird things too#with the uhf sound most people past 25 can't hear#folks were so mad at places for using those#poor you can't loiter

6 notes

·

View notes

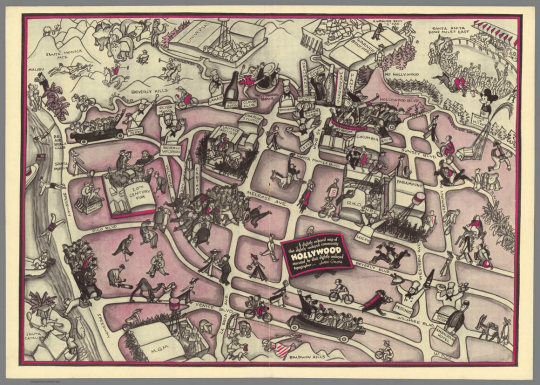

Photo

‘Cockeyed’ Map Shows Both Glamour and Margins of 1930s Hollywood If maps allow our imaginations to travel without care or trouble, then maps of the past do one better: They are time machines into different eras. And pictorial maps, which offer the perspective and subjective detail that mere road maps or city plans don’t, add a bit of couleur locale as extra seasoning. Like this one, of Hollywood in its Golden Age. The humming of 1930s Hollywood street life almost bursts off the page—this is the age of the talkies, after all. A vignette straddling Beverly and Vine sets the scene: A slightly cockeyed map of that slightly cockeyed community, Hollywood, executed by that slightly cockeyed topographer … John Groth. Chicago native Groth (1908–1988) was a cartoonist who became art director of Esquire in his 20s. He would go on to have a brilliant career as a war artist for the Chicago Sun. In 1944, he rode the first Allied jeep into newly liberated Paris. If he’d been any closer to the front, ���he would have had to have sat in the Kraut’s lap,” joked Ernest Hemingway. After WWII, he reported from Korea, the Belgian Congo, and Vietnam, among other places. But back in 1937, when he produced this map of Hollywood for Stage magazine, that was all still in the future. The 1930s was a time when Hollywood was dominated by the old studio system. Old? That’s relative. To be fair, many of their names still sound familiar today. There’s 20th Century Fox, on Pico Boulevard, right next to the West Side Tennis Club. Just to the south is MGM, near Venice Boulevard. In between: a fair bit of golfing. And, inexplicably, a Bedouin leading a camel down the boulevard. Paramount can be found on the corner of Western Avenue and Santa Monica Boulevard. Right next door are RKO and NBC. And right across Santa Monica Boulevard is Columbia. Further down Santa Monica, there’s United Artists, a more elaborate operation than Chaplin Studio, right across the street. To the north, on the other side of the Beverly Hills, there’s the gigantic Universal Studios on Cahuenga Boulevard. It’s big enough to contain an entire village—and attract a herd of elephants, coming down the Santa Monica Mountains. Warner Brothers is also on the other side of the mountains—Mount Hollywood, as it so happens; no mention of the HOLLYWOODLAND sign (the LAND was dropped in 1949). It’s also gigantic: They’re filming a sea battle in the back lot. Astride the roof is a Warner Brothers "g-man": a reference to movie detectives, or to the studio’s real-life enforcers? If you liked fine dining, there were worse places to be than Golden Age Hollywood. Halfway between 20th Century Fox and United Artists, there’s the chefs of the Victor Hugo and the Beverly Wilshire, competing for your attention. In the 1930s, Lamaze was a fancy Hollywood restaurant, not a child-birthing technique; right next door were the Trocadero and the Clover Club—all pretty close to the Hollywood Bowl. By the look on his face, the chef at the Lamaze may be going over to the Clover when his shift is over. Other restaurants of note: Perinos, at Wilshire and Western; Levy’s, at Santa Monica and Vine; and Lucey’s, on Melrose. Sprinkled across town were Brown Derby restaurants. Named after the first of the chain, which opened on Wilshire Boulevard in 1926 and was shaped like a semicircular derby hat, the restaurants were a fixture of Golden Age Hollywood. Even outside the glamour of the studios and the high life of fine dining, Hollywood is portrayed as a city of leisure and entertainment. People in bathing suits are diving into the Pacific along the coast-hugging Speedway, from Malibu via the Bel Air Beach Club and Santa Monica all the way down to Santa Catalina Island. Masses of cyclists—yes, cyclists—are cruising down the city’s boulevards and avenues. Could 1930s L.A. have been a cycling paradise? But then what’s with all the horses, not just polo-playing outside of town, but also racing through the center—their riders showing off with their hats in one hand? Surely, this can’t have been a common sight. Buses overflowing with tourists are driving around town, perhaps already then being shown the homes of the stars. Perhaps a star has been spotted near the Carthay; that would explain the rush of onlookers. In the northeast corner, the Santa Anita racetrack is giving punters a run for their money—literally. Closer by, Mickey Mouse waves to passersby from his home on Riverside Drive, not far from a well spouting oil. Huge crowds gather at the American Legion Stadium in the center. Elegant ladies and gentlemen striding around town complete the picture of a city as elegant and attractive as any in the world. Yet Groth wouldn’t be a perceptive—or ‘cockeyed’—observer if he didn’t also look beyond the glamour. Check the bottom right for a Native American couple and their child making their way into Hollywood, looking for opportunity. Two streets down, a Mexican immigrant is doing the same, his donkey laden with wares he will be hoping to sell. And on the corner of La Brea and Venice, Chinese laborers are moving earth right behind the back of a movie director, seated in the classic folding chair, loudspeaker in hand. All these figures are placed near the edge of the map, a textbook demonstration of what it means to be "marginal." This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think's newsletter. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/1930s-hollywood-map

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"May the blessings of Govardhan Puja bring you prosperity, joy, and protection. Let’s celebrate the bond between humans and nature, just as Lord Krishna did! 🌸🌿 Happy Govardhan Puja to all! 🙏 #GovardhanPuja #KrishnaBlessings #NatureAndDivinity #FestiveSpirit"#GreaterNoidaLuxuryHomes #YourDreamHome #luxuryhomes #lifestyleyoudeserve #luxuriousamenities #epitomeofluxury #YamunaExpressway #GreaterNoida #residential #Apartment #perfectlocation #PremiumLifestyle #premiumhomes #Skyline #Speedway #Avenue #speedwayavenue #motogp

0 notes

Text

Events 9.11 (1840-1970)

1851 – Christiana Resistance: Escaped slaves led by William Parker fight off and kill a slave owner who, with a federal marshal and an armed party, sought to seize three of his former slaves in Christiana, Pennsylvania, thereby creating a cause célèbre between slavery proponents and abolitionists. 1852 – Outbreak of Revolution of September 11 resulting in the State of Buenos Aires declaring independence as a Republic. 1857 – The Mountain Meadows massacre: Mormon settlers and Paiutes massacre 120 pioneers at Mountain Meadows, Utah. 1881 – In the Swiss state of Glarus, a rockslide buries parts of the village of Elm, destroying 83 buildings and killing 115 people. 1897 – After months of pursuit, generals of Menelik II of Ethiopia capture Gaki Sherocho, the last king of the Kaffa. 1903 – The first race at the Milwaukee Mile in West Allis, Wisconsin is held. It is the oldest major speedway in the world. 1905 – The Ninth Avenue derailment occurs in New York City, killing 13. 1914 – World War I: Australia invades German New Guinea, defeating a German contingent at the Battle of Bita Paka. 1914 – The Second Period of Russification: The teaching of the Russian language and Russian history in Finnish schools is ordered to be considerably increased as part of the forced Russification program in Finland run by Tsar Nicholas II. 1916 – The Quebec Bridge's central span collapses, killing 11 men. The bridge previously collapsed completely on August 29, 1907. 1919 – United States Marine Corps invades Honduras. 1921 – Nahalal, a Jewish moshav in Palestine, is settled. 1922 – The Treaty of Kars is ratified in Yerevan, Armenia. 1941 – Construction begins on the Pentagon. 1941 – Charles Lindbergh's Des Moines speech accusing the British, Jews and FDR's administration of conspiring for war with Germany. 1943 – World War II: German troops occupy Corsica and Kosovo-Metohija ending the Italian occupation of Corsica. 1944 – World War II: RAF bombing raid on Darmstadt and the following firestorm kill 11,500. 1945 – World War II: Australian 9th Division forces liberate the Japanese-run Batu Lintang camp, a POW and civilian internment camp on the island of Borneo. 1954 – Hurricane Edna hits New England (United States) as a Category 2 hurricane, causing significant damage and 29 deaths. 1961 – Hurricane Carla strikes the Texas coast as a Category 4 hurricane, the second strongest storm ever to hit the state. 1965 – Indo-Pakistani War: The Indian Army captures the town of Burki, just southeast of Lahore. 1967 – China's People's Liberation Army (PLA) launched an attack on Indian posts at Nathu La, Sikkim, India, which resulted in military clashes. 1968 – Air France Flight 1611 crashes off Nice, France, killing 89 passengers and six crew.

0 notes

Text

Day 5. Friday Sept 6: Nashville Tennessee to Huntsville, Grant, Talledega, and Montgomery, Alabama. 486 kms.

Today, I go from the corn, soybeans, and livestock of Kentucky to the corn, cotton, chickens, and peanuts of Alabama - America's 24th most populous state and the heart of Dixie.

My day starts heading south from Nashville towards the Alabama border just 100 miles away and ultimately Montgomery, the capital of Alabama. On the way, I pass by Huntsville, Alabama's most populous city (222,000), and home of the US Space and Rocket Center.

The thing I notice first and foremost, however, is Alabama's red subsoil, caused by a combination of iron oxides and good drainage and perfect for the growth of corn and cotton.

For some reason, I am also struck by a feeling of "have and have nots" as evidenced not only by the homes and farms I pass but also by the preponderance of Baptist churches which always seem to flourish in the poorer areas. Alabama is not poor. It is America's 33rd richest state. It just doesn't seem like it is very evenly spread out.

After Huntsville, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, I come across Grant, small town in Marshal County of only 1,039. It is, however, the home of the Kate Duncan Smith DAR School. The school was established in 1924 and operates under a public-private partnership between the Marshall County School System and the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The unique and historic campus covers 15 acres and contains 12 buildings, constructed between 1924 and 1957 in the Craftsman style of local stone or logs. Known for its quality education, more than 60% of its students come from families living below the poverty line.

From there, I continue southward to Talladega County, the land of Ricky Bobby, the Talladega International Speedway, and Talladega County Jail, LOL.

One thing I didnt realise was how much water there is in Alabama. The state actually has three broad areas of watersheds:

Tennessee River drainage: Located in the northern part of the state, this watershed contains the Tennessee River, Pickwick Lake, Wilson Lake, Wheeler Lake, and Lake Guntersville, some of which I rode through.

Mobile River Basin: Located in the central part of the state, this watershed contains the upper Tombigbee River, Black Warrior River, lower Tombigbee River, Cahaba River, Coosa River, Tallapoosa River, Lake Martin, Weiss Lake, and Smith Lake, again some of which I rode through.

Coastal Drainages: Located in the southern part of the state, this watershed contains smaller river basins that empty into the Gulf of Mexico. I expect that I'll be riding through that tomorrow.

Soeaking of water, for the last two hours, there have been intermittent rain drops in the air. In Talladega, however, the heavens open, and I'm forced to pull over to rainproof my ride. It continues all the way to my hotel in Montgomery, and as I sit here blogging, the rain is pouring down outside. It's a gentle reminder of how lucky I have been with the weather so far. This afternoon and tomorrow, that comes to an end. It looks like rain all day tomorrow. I have rain gear, but it likely means, like today, not so many pictures.

A final word on Montgomery. Population 198,000 and capital of Alabama, it was the original capital of the Confederate states before it moved to Richmond, Virginia, and is home to the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, the home church of Martin Luther King Jr. It is also a major center of events and protests in the Civil Rights Movement including the Montgomery bus boycott and the Selma to Montgomery marches. A lot of history was made here.

0 notes

Text

Unlocking Financial Solutions with Speedway Loans: Exploring the World of Title Loans

In today's fast-paced world, financial emergencies can strike unexpectedly, leaving individuals in need of immediate cash solutions. For many Texans, title loans have emerged as a dependable resource during times of financial strain. SpeedwayLoans stands out as a trusted provider of title loans, offering quick and convenient access to cash for individuals facing temporary financial setbacks. Let's dive into the realm of title loans and discover how SpeedwayLoans can offer the financial assistance you require.

Understanding Title Loans:

Title loans, also referred to as car title loans or auto title loans, are short-term loans that utilize the borrower's vehicle as collateral. These loans are known for their accessibility, making them a popular choice for individuals with imperfect credit or those in need of rapid cash. To secure a title loan, borrowers must own their vehicle outright and provide the title as collateral to the lender.

SpeedwayLoans: Your Reliable Title Loan Provider:

At SpeedwayLoans, we recognize that financial emergencies can affect anyone, irrespective of credit history or financial status. That's why we're dedicated to delivering fast and hassle-free title loan services to our clients in Texas. Whether you're seeking a Title Loan Quote Online in Texas or fast online title loans, SpeedwayLoans is here to assist you.

Exploring Title Loan Options:

With SpeedwayLoans, Texans have access to a diverse array of title loan options tailored to meet their unique needs and circumstances. From title loans that don't necessitate the car to car title loans with no credit check, we provide flexible solutions designed to address your financial requirements. Our Easy Title Loans in Texas simplify the process of obtaining the cash you need without enduring lengthy approval procedures or credit checks.

Benefits of SpeedwayLoans Title Loans:

Choosing SpeedwayLoans for your title loan needs comes with several advantages:

Fast Approval Process: Our online title loan service facilitates quick and effortless access to a quote, enabling you to acquire the cash you require promptly.

Convenient Application: Our straightforward online application process allows you to apply for a title loan from the comfort of your own home.

Flexible Repayment Options: Recognizing that each individual's financial situation is unique, we offer flexible repayment options tailored to suit your budget.

No Credit Check Required: Unlike conventional loans, SpeedwayLoans title loans do not necessitate a credit check, rendering them accessible to individuals with less-than-perfect credit.

Retain Your Car: While your vehicle's title serves as collateral for the loan, you retain the ability to drive your car as usual while repaying the loan.

Conclusion: Accessing Cash When You Need It Most

In conclusion, title loans provide a convenient and accessible avenue for swiftly accessing cash during financial emergencies. With Speedway Loans, Texans can avail themselves of rapid and straightforward title loan services sans the need for a credit check. Whether you require a title loan quote online in Texas or fast online title loans, Speedway Loans is poised to provide the financial aid you seek. Explore our website today to discover more about our title loan services and how we can assist you in unlocking financial solutions.

#online texas title loan service#approved title loans texas#can you pawn your car#fast online title loans#online title loans for bad credit#title loan without title online#title loans online fast#car title loan texas#will a bank finance a rebuilt title#car title loans no credit check#cash and title loans#easy title loans

0 notes

Text

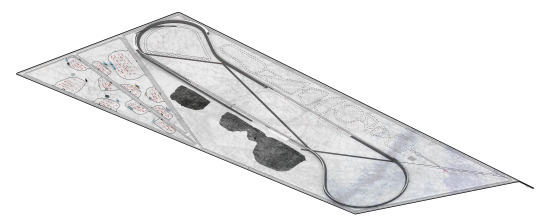

The Dale Earnhardt Memorial Super Speedway

My inquiry into NASCAR-culture and the design of oval-track racing began with a novel interest in the Dale Earnhardt 2001 Car Crash as my initial form of damage control. I took Dale’s case as an avenue into analyzing the intermingling between car and speed culture in relation to American media antics.

Dale Earndhardt’s 2001 crash, when analyzed beyond its immediate impact, could be considered a textbook case of spectacle. Earndhardt, number 3, was already extremely popular at the time of the race, and his instant death only compounded this status, making him reach legendary status in NASCAR history–he is still beloved by fans, both in memory and in material artifacts.

The Daytona 500 is the ultimate competition and broadcast for NASCAR drivers and fanatics–it is their superbowl, so to speak. This was compounded by the fact that the 2001 Daytona 500 marked the first Cup Series race under NASCAR's new centralized television contracts, which shifted responsibility for NASCAR's media rights from the track owners to NASCAR itself.

In analyzing the crash in-itself through autopsy and traffic-collision reports, I realized that the crash could only be understood fruitfully within a system of components–not one single thing “killed” Dale. My drawings then worked towards unraveling these facts. What differentiates his crash from Schrader’s (no. 36, who crashed along with Dale but left the scene basically unharmed) is plentiful, but I mainly focused on the particular velocities and geometries, which created such an arc to enact a particularly brutal impact. I carry this language of forensic and geometrical analysis throughout my design.

The tracks (including Daytona) boast quite an extensive and impressive amount of engineering ingenuity to make racing safer, especially after Dale’s death, which sparked a movement towards safety in NASCAR (which, of note, Dale himself demeaned and constituted as the reason that NASCAR was heading on a downwards path). For example, restrictor plates are enforced upon the stock-cars so that they may not reach the risk of their top-speed.

NASCAR, as many other people comment, has found a way to make the car-crash both safe and beautiful–plenty of crashes have occurred since Dale’s crash in NASCAR, but none of them have been fatal. This is mainly due to the aforementioned engineering ingenuity spawning at NASCAR-tracks, for example, the SAFER-Barrier which enwraps the course of a track so that there is a softer impact, as compared to crashing straight into concrete.

Inspired by this, I initially began by subverting this safer-barrier design to create a seating situation on-top of these barriers to allow viewers an intensely close view of the track while simultaneously maintaining a high amount of safety.

From thereforth, the objective of my final project became clear: to reimagine the in-situ engineering artifacts currently being deployed at oval-track stadiums and push them to their limits to create newfound perspectives for people to experience the races. To agitate the boundary between risk and safety while paying respect to the culture and ingenuity of NASCAR.

I decided upon the site of the Bonneville Salt Flats (Western Utah); both for its historical precedent of landspeed records but also because salt is particularly enthralling for speed because of its frictionary properties. My design is kept incredibly long and short in order to keep the landscape views in-tact.

You enter the stadium through an exit-ramp heading Westbound on the Dwight Eisenhower Highway, just a mile or two before Wendover. This ramp is banked and an autobahn, allowing people to experience oval-track conditions for a mile-long stretch until they reach the track itself. Car circulation is handled by roads which are the offset tangential angles of the track’s banked curves.

0 notes

Photo

The People's Way inside George Floyd Square on Chicago Avenue. Formerly a Speedway gas station, the area has been a protest zone since May 2020 following the murder of George Floyd. The city has since purchased the property.

1 note

·

View note

Text

[ad_1] A transformative improvement is on the horizon in Northlake, including to the swell of actual property exercise in Denton County. Canada-based Western Securities is spearheading Chadwick Farms, a 60-acre mixed-use undertaking slated for as much as 900 flats, 60,000 sq. ft of retail, restaurant and leisure house and a lodge, the Dallas Morning Information reported. Retail Avenue Advisors will deal with leasing for the retail element, which is ready to incorporate a 35,000-square-foot buying middle referred to as Chadwick Commons, in response to Western Securities’ web site. Chadwick Farms, positioned east of Interstate 35 close to Texas Motor Speedway, is close to a deliberate Dallas Stars youth sports activities facility. Northlake residents permitted a $45 million bond in November to fund that improvement. Northlake anticipates that the sports activities complicated will catalyze its financial improvement plan, which identifies sports-oriented tourism as a development driver. The development timeline for Chadwick Farms is considerably synchronized with the sports activities complicated, the outlet mentioned. The primary part will give attention to the multifamily portion. The Star’s facility is a part of the NHL squad’s purpose to develop its affect past the ice, as it really works to create varied youth sports activities alternatives throughout Dallas-Fort Price. The multisport facility, projected to have over 1.3 million guests yearly, will characteristic NHL-level ice rinks, basketball and volleyball courts, pickleball courts, a well being clinic and eating choices. It’s anticipated to open by the tip of subsequent yr. Denton County’s regular inhabitants development has attracted a flock of builders. Irving-based Realty Capital Residential is on the helm of a 20-acre mixed-use undertaking, referred to as Parkway District, southeast of Denton. It should comprise flats, 22,000 sq. ft of retail and restaurant house, 16 townhomes and a lodge. Individually, Dallas-based Technology Housing Improvement is plotting a three-building, $33 million multifamily complicated within the space. —Quinn Donoghue Learn extra [ad_2] Supply hyperlink

0 notes

Text

Hotel for Sale in Indiana: Unveiling Lucrative Investment Opportunities

Indiana, a state known for its diverse attractions, historic sites, and thriving urban centers, offers a compelling landscape for those seeking investment opportunities in the hospitality sector. The quest for hotel acquisitions in Indiana, facilitated by keywords like "hotel for sale," unlocks a realm of possibilities for astute investors eyeing the dynamic market.

Indiana's Allure for Hotel Investment

From the iconic Indianapolis Motor Speedway to the picturesque landscapes of Brown County and the cultural vibrancy of cities like Indianapolis and Bloomington, Indiana boasts an array of attractions. These diverse locales cater to a broad spectrum of travelers, from leisure tourists exploring historic sites to business travelers seeking convenience and comfort.

Crucial Considerations in Hotel Investment

Location stands as a pivotal factor in hotel investments. Proximity to tourist attractions, major highways, and business districts often correlates with higher demand and occupancy rates. Scrutinizing a hotel's financial health by assessing revenue trends, operational costs, and future growth potential is paramount for prudent investment decisions. Furthermore, evaluating property condition, amenities, and adherence to local regulations ensures a solid foundation for successful hotel ventures.

Leveraging Keywords for Insightful Ventures

The strategic use of keywords like "hotel for sale" in Indiana empowers investors to navigate online platforms efficiently. These keywords serve as a compass, guiding investors toward relevant listings and potential investment prospects across Indiana's bustling hospitality market. Leveraging such keywords streamlines the search process, enabling investors to compare options and make informed investment decisions.

Conclusion: Tapping into Indiana's Hospitality Market

Exploring hotel for sale in Indiana offers investors an avenue to tap into a vibrant and diverse market. By leveraging keywords, investors can uncover promising investment opportunities, paving the way for successful ventures in Indiana's thriving hospitality industry. Utilizing these strategic tools, investors position themselves to make informed decisions and secure lucrative hotel investments in the Hoosier State.

0 notes

Text

0 notes