#South Harlem Methodist Episcopal Church

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lost and found department: synagogues of Manhattan

Illustration by A Journey through NYC religions Ellen Levitt is one of the most interesting detectives in the city. Her job as a writer is finding lost synagogues. The book about her sleuthing in Manhattan, Staten Island and Governeur’s Island is available for purchase. The Last Synagogues of Manhattan is a densely packed treasure trove of architectural observations, naming practices, and…

#Abelardo Berrios#B&039;nai Menasheh#Beit Knesset HaGadol#Beth Ha-Knesset Ha Gadal#Congregation B’nai Israel#Ellen Levitt#Iglesia Pentecostal Camino A Damasco#John Lugo#La Sinagoga#Methodist Episcopal Church of the Savior#Nachlath Svi#Nachlath Zvi B’nai Israel Linoth Hazedek B’nai Menashe#South Harlem Methodist Episcopal Church#The Lost Synagogues of Manhattan

0 notes

Text

Rose McClendon (August 27, 1884 – July 12, 1936) was an actress born in South Carolina. Her original name was Rosalie Virginia Scott. Her parents were Sandy and Tena Scott. In 1890, her parents worked for a well-established family as a housekeeper and coachman in New York City. She received her education through the public schools in New York where acting became her main focus of interest.

She married Henry Pruden McClendon (1904) who was trained as a chiropractor but who could only find work as a Pullman porter. Together they moved from lower Manhattan to Harlem where she was involved in the St. Mark’s African Methodist Episcopal Church often using her theatrical talent.

After studying by scholarship at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts between 1916 and 1918, she gave her first stage performance in 1919 in the play Justice. She would perform in other productions including In Abraham’s Bosom, Porgy and Bess, and Deep River. Along with her acting and directing in 1935 she and Dick Campbell created the Negro People’s Theatre.

She was one of the few African American actresses who worked consistently in New York in the 1920s. She toured throughout the US and Europe. She landed a starring role in the 1934 production of “John Henry, Black River Giant.” In October of 1935, she was cast as Cora Lewis in Langston Hughes’s long-running play, Mulatto. She performed in Mulatto 375 times until her death. In 1937 Campbell and Muriel Rahn established the Rose McClendon Players in her honor. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

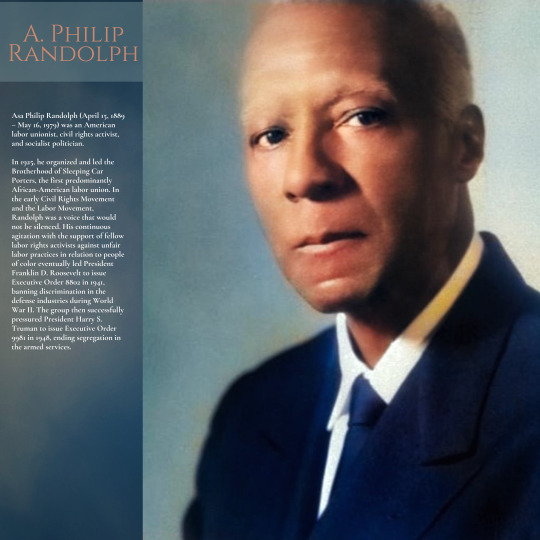

A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American labor unionist, civil rights activist, and socialist politician.

In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly African-American labor union. In the early Civil Rights Movement and the Labor Movement, Randolph was a voice that would not be silenced. His continuous agitation with the support of fellow labor rights activists against unfair labor practices in relation to people of color eventually led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 in 1941, banning discrimination in the defense industries during World War II. The group then successfully pressured President Harry S. Truman to issue Executive Order 9981 in 1948, ending segregation in the armed services.

In 1963, Randolph was the head of the March on Washington, which was organized by Bayard Rustin, at which Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his "I Have A Dream" speech. Randolph inspired the "Freedom Budget", sometimes called the "Randolph Freedom budget", which aimed to deal with the economic problems facing the black community, it was published by the Randolph Institute in January 1967 as "A Freedom Budget for All Americans".

Early life and education

Randolph was born April 15, 1889, in Crescent City, Florida, the second son of the Rev. James William Randolph, a tailor and minister in an African Methodist Episcopal Church, and Elizabeth Robinson Randolph, a skilled seamstress. In 1891, the family moved to Jacksonville, Florida, which had a thriving, well-established African-American community.

From his father, Randolph learned that color was less important than a person's character and conduct. From his mother, he learned the importance of education and of defending oneself physically against those who would seek to hurt one or one's family, if necessary. Randolph remembered vividly the night his mother sat in the front room of their house with a loaded shotgun across her lap, while his father tucked a pistol under his coat and went off to prevent a mob from lynching a man at the local county jail.

Asa and his brother, James, were superior students. They attended the Cookman Institute in East Jacksonville, the only academic high school in Florida for African Americans. Asa excelled in literature, drama, and public speaking; he also starred on the school's baseball team, sang solos with the school choir, and was valedictorian of the 1907 graduating class.

After graduation, Randolph worked odd jobs and devoted his time to singing, acting, and reading. Reading W. E. B. Du Bois' The Souls of Black Folk convinced him that the fight for social equality was most important. Barred by discrimination from all but manual jobs in the South, Randolph moved to New York City in 1911, where he worked at odd jobs and took social sciences courses at City College.

Marriage and family

In 1913 Randolph courted and married Mrs. Lucille Campbell Green, a widow, Howard University graduate, and entrepreneur who shared his socialist politics. She earned enough money to support them both. The couple had no children.

Early career

Shortly after Randolph's marriage, he helped organize the Shakespearean Society in Harlem. With them he played the roles of Hamlet, Othello, and Romeo, among others. Randolph aimed to become an actor but gave up after failing to win his parents' approval.

In New York, Randolph became familiar with socialism and the ideologies espoused by the Industrial Workers of the World. He met Columbia University Law student Chandler Owen, and the two developed a synthesis of Marxist economics and the sociological ideas of Lester Frank Ward, arguing that people could only be free if not subject to economic deprivation. At this point, Randolph developed what would become his distinctive form of civil rights activism, which emphasized the importance of collective action as a way for black people to gain legal and economic equality. To this end, he and Owen opened an employment office in Harlem to provide job training for southern migrants and encourage them to join trade unions.

Like others in the labor movement, Randolph favored immigration restriction. He opposed African Americans' having to compete with people willing to work for low wages. Unlike other immigration restrictionists, however, he rejected the notions of racial hierarchy that became popular in the 1920s.

In 1917, Randolph and Chandler Owen founded The Messenger with the help of the Socialist Party of America. It was a radical monthly magazine, which campaigned against lynching, opposed U.S. participation in World War I, urged African Americans to resist being drafted, to fight for an integrated society, and urged them to join radical unions. The Department of Justice called The Messenger "the most able and the most dangerous of all the Negro publications." When The Messenger began publishing the work of black poets and authors, a critic called it "one of the most brilliantly edited magazines in the history of Negro journalism."

Soon thereafter, however, the editorial staff of The Messenger became divided by three issues – the growing rift between West Indian and African Americans, support for the Bolshevik revolution, and support for Marcus Garvey's Back-to-Africa movement. In 1919, most West Indian radicals joined the new Communist Party, while African-American leftists – Randolph included – mostly supported the Socialist Party. The infighting left The Messenger short of financial support, and it went into decline.

Randolph ran on the Socialist Party ticket for New York State Comptroller in 1920, and for Secretary of State of New York in 1922, unsuccessfully.

Union organizer

Randolph's first experience with labor organization came in 1917, when he organized a union of elevator operators in New York City. In 1919 he became president of the National Brotherhood of Workers of America, a union which organized among African-American shipyard and dock workers in the Tidewater region of Virginia. The union dissolved in 1921, under pressure from the American Federation of Labor.

His greatest success came with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who elected him President in 1925. This was the first serious effort to form a labor institution for employees of the Pullman Company, which was a major employer of African Americans. The railroads had expanded dramatically in the early 20th century, and the jobs offered relatively good employment at a time of widespread racial discrimination. Because porters were not unionized, however, most suffered poor working conditions and were underpaid.

Under Randolph's direction, the BSCP managed to enroll 51 percent of porters within a year, to which Pullman responded with violence and firings. In 1928, after failing to win mediation under the Watson-Parker Railway Labor Act, Randolph planned a strike. This was postponed after rumors circulated that Pullman had 5,000 replacement workers ready to take the place of BSCP members. As a result of its perceived ineffectiveness membership of the union declined; by 1933 it had only 658 members and electricity and telephone service at headquarters had been disconnected because of nonpayment of bills.

Fortunes of the BSCP changed with the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. With amendments to the Railway Labor Act in 1934, porters were granted rights under federal law. Membership in the Brotherhood jumped to more than 7,000. After years of bitter struggle, the Pullman Company finally began to negotiate with the Brotherhood in 1935, and agreed to a contract with them in 1937. Employees gained $2,000,000 in pay increases, a shorter workweek, and overtime pay. Randolph maintained the Brotherhood's affiliation with the American Federation of Labor through the 1955 AFL-CIO merger.

Civil rights leader

Through his success with the BSCP, Randolph emerged as one of the most visible spokespeople for African-American civil rights. In 1941, he, Bayard Rustin, and A. J. Muste proposed a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in war industries, an end to segregation, access to defense employment, the proposal of an anti-lynching law and of the desegregation of the American Armed forces. Randolph's belief in the power of peaceful direct action was inspired partly by Mahatma Gandhi's success in using such tactics against British occupation in India. Randolph threatened to have 50,000 blacks march on the city; it was cancelled after President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, or the Fair Employment Act. Some activists, including Rustin, felt betrayed because Roosevelt's order applied only to banning discrimination within war industries and not the armed forces. Nonetheless, the Fair Employment Act is generally considered an important early civil rights victory.

And the movement continued to gain momentum. In 1942, an estimated 18,000 blacks gathered at Madison Square Garden to hear Randolph kick off a campaign against discrimination in the military, in war industries, in government agencies, and in labor unions. Following passage of the Act, during the Philadelphia transit strike of 1944, the government backed African-American workers' striking to gain positions formerly limited to white employees.

Buoyed by these successes, Randolph and other activists continued to press for the rights of African Americans. In 1947, Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil disobedience. When President Truman asked Congress for a peacetime draft law, Randolph urged young black men to refuse to register. Since Truman was vulnerable to defeat in 1948 and needed the support of the growing black population in northern states, he eventually capitulated. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman abolished racial segregation in the armed forces through Executive Order 9981.

In 1950, along with Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, and, Arnold Aronson, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council, Randolph founded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). LCCR has been a major civil rights coalition. It coordinated a national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.

Randolph and Rustin also formed an important alliance with Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1957, when schools in the south resisted school integration following Brown v. Board of Education, Randolph organized the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom with Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1958 and 1959, Randolph organized Youth Marches for Integrated Schools in Washington, DC. At the same time, he arranged for Rustin to teach King how to organize peaceful demonstrations in Alabama and to form alliances with progressive whites. The protests directed by James Bevel in cities such as Birmingham and Montgomery provoked a violent backlash by police and the local Ku Klux Klan throughout the summer of 1963, which was captured on television and broadcast throughout the nation and the world. Rustin later remarked that Birmingham "was one of television's finest hours. Evening after evening, television brought into the living-rooms of America the violence, brutality, stupidity, and ugliness of {police commissioner} Eugene "Bull" Connor's effort to maintain racial segregation." Partly as a result of the violent spectacle in Birmingham, which was becoming an international embarrassment, the Kennedy administration drafted civil rights legislation aimed at ending Jim Crow once and for all.

Randolph finally realized his vision for a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, which attracted between 200,000–300,000 to the nation's capital. The rally is often remembered as the high-point of the Civil Rights Movement, and it did help keep the issue in the public consciousness. However, when President Kennedy was assassinated three months later, Civil Rights legislation was stalled in the Senate. It was not until the following year, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, that the Civil Rights Act was finally passed. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed. Although King and Bevel rightly deserve great credit for these legislative victories, the importance of Randolph's contributions to the Civil Rights Movement is large.

Religion

Randolph avoided speaking publicly about his religious beliefs to avoid alienating his diverse constituencies. Though he is sometimes identified as an atheist, particularly by his detractors, Randolph identified with the African Methodist Episcopal Church he was raised in. He pioneered the use of prayer protests, which became a key tactic of the civil rights movement. In 1973, he signed the Humanist Manifesto II.

Death

Randolph died in his Manhattan apartment on May 16, 1979. For several years prior to his death, he had a heart condition and high blood pressure. He had no known living relatives, as his wife had died in 1963, before the March on Washington.

Awards and accolades

In 1942, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People awarded Randolph the Spingarn Medal.

In 1953, the IBPOEW (Black Elks) awarded him their Elijah P. Lovejoy Medal, given "to that American who shall have worked most successfully to advance the cause of human rights, and for the freedom of Negro people."

On September 14, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Randolph with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In 1967 awarded the Eugene V. Debs Award

In 1967 awarded the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award. It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII that calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations.

Named Humanist of the Year in 1970 by the American Humanist Association.

Named to the Florida Civil Rights Hall of Fame in January 2014.

Legacy

Randolph had a significant impact on the Civil Rights Movement from the 1930s onward. The Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama was directed by E.D. Nixon, who had been a member of the BSCP and was influenced by Randolph's methods of nonviolent confrontation. Nationwide, the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s used tactics pioneered by Randolph, such as encouraging African Americans to vote as a bloc, mass voter registration, and training activists for nonviolent direct action.

In buildings, streets, and trains

Amtrak named one of their best sleeping cars, Superliner II Deluxe Sleeper 32503, the "A. Philip Randolph" in his honor.

A. Philip Randolph Academies of Technology, in Jacksonville, FL, is named in his honor.

A. Phillip Randolph Boulevard in Jacksonville, Florida, formerly named Florida Avenue, was renamed in A. Phillip Randolph's honor. It is located on Jacksonville's east side, near EverBank Field.

A. Philip Randolph Campus High School (New York City High School 540), located on the City College of New York campus, is named in honor of Randolph. The school serves students predominantly from Harlem and surrounding neighborhoods.

The A. Philip Randolph Career Academy in Philadelphia, Pa was named in his honor.

The A. Philip Randolph Career and Technician Center in Detroit, MI is named in his honor.

The A. Philip Randolph Institute is named in his honor.

PS 76 A. Philip Randolph in New York City, NY is named in his honor

A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is in Chicago's Pullman Historic District.

Edward Waters College in Jacksonville, Florida houses a permanent exhibit on the life and accomplishments of A. Philip Randolph.

Randolph Street, in Crescent City, Florida, was dedicated to him.

A. Philip Randolph Library, at Borough of Manhattan Community College

A. Philip Randolph Square park in Central Harlem was renamed to honor A. Philip Randolph in 1964 by the City Council, under a local law introduced by Council Member J. Raymond Jones and signed by Mayor John V. Lindsay. In 1981, a group of loosely organized residents began acting as stewards of the park, during the dark days of abandonment and disinvestment in Central Harlem. By 2010 that group, now the Friends of A. Philip Randolph Square--founded by Gregory C. Baggett, who named longterm residents Ms. Gloria Wright; Ms. Ivy Walker; and Mr. Cleveland Manley, as Trustee of the park--would be formally incorporated to provide better stewardship and programming at a time when the neighborhood would be undergoing rapid growth and diversification. In 2018, the Friends of A. Philip Randolph Square would further expand the scope of its work beyond stewardship over the park to prepare a major revitalization plan "to improve conditions in the park and the neighborhood around the park" operating under a new entity, the A. Philip Randolph Neighborhood Development Alliance that seeks to obtain broad neighborhood and community representation for its revitalization plan based on building the personal and collective assets within the neighborhood.

Arts, entertainment, and media

+ 1994 Documentary A. Philip Randolph: For Jobs and Freedom, PBS

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed A. Philip Randolph on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

The story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was made into the 2002 Robert Townsend film 10,000 Black Men Named George starring Andre Braugher as A. Philip Randolph. The title refers to the demeaning custom of the time when Pullman porters, all of whom were black, were just addressed as "George".

A statue of A. Philip Randolph was erected in his honor in the concourse of Union Station in Washington, D.C..

In 1986 a nine-foot bronze statue of Randolph by Tina Allen was erected in Boston's Back Bay commuter train station.

On February 3, 1989, the United States Postal Service issued a 25-cent postage stamp in Randolph's honor.

Other

James L. Farmer, Jr., co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), cited Randolph as one of his primary influences as a Civil Rights leader.

Randolph is a member of the Labor Hall of Fame.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Stride Toward Freedom” by Martin Luther King Jr. published 1958

The release of this book was far from being without incident....the most famous being that a mentally ill woman, named Izola Curry-who had growing delusions of paranoia-mostly directed against the NAACP-approached King at a book-signing in Harlem and stabbed him.

According to wiki: King went on a tour to promote his book, Stride Toward Freedom, soon after it was published. During a book signing at Blumstein's department store in Harlem, on September 20, 1958, Curry approached and asked him if he was Martin Luther King, Jr. When King replied in the affirmative, Curry stabbed him in the chest with a steel letter opener.

Careful surgery was required to remove the blade. King wrote in his posthumously published autobiography that he was told that the razor tip of the instrument had been touching my aorta and that my whole chest had to be opened to extract it. 'If you had sneezed during all those hours of waiting,' Dr. Maynard said, 'your aorta would have been punctured and you would have drowned in your own blood.'

While he was still in the hospital, on September 30, King issued a press release in which he reaffirmed his belief in "the redemptive power of nonviolence" and issued a hopeful statement about his attacker: "I felt no ill will toward Mrs. Izola Currey [sic] and know that thoughtful people will do all in their power to see that she gets the help she apparently needs if she is to become a free and constructive member of society." He issued a similar statement on his return home, again stating that he hoped she would get help, and that society would improve so that "a disorganized personality need not become a menace to any man."

On October 17, after hearing King's testimony, a grand jury indicted Curry for attempted murder. At the time of her attack on King, Curry was also carrying a loaded Galesi-Brescia pistol, hidden inside her bra.

I find it crucial here to say now (more than ever-and do pardon my sermon here):

Like so many who have forgiven their attackers: popes, Gandhi, Rosa Parks, the Amish community of Nickel Mines, Robert Rule (father of Green River Killer victim), Tiana Carruthers (first shooting victim of Kalamazoo, MI spree killer Jason “MAGA” Dalton https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/2016/04/14/kalamazoo-shooting-tiana-carruthers/83043798/), the family members and friends of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC (that was targeted by 21 yo. white supremacist Dylann Roof), Ann Arbor resident Keshia Thomas, Theresa Bond (daughter of victim of once-prominent South Boston gangster James “Whitey” Bulger), and so many others of various crimes and senseless attacks and events resulting of gross negligence across this globe, one will never see an act so removed from reflex-based conformist thinking than forgiveness. It is a thing rarely encouraged in TV, films, or popular media saturated with themes of violence and vengeance laden with climatic scenes of the “hero” making a pithy quip before “offing” the bad guy.

The very act of forgiveness just feels so wrong-so awkward and uncharted. It doesn’t make you seem funny or strong....but it requires a different kind of strength-the strength to be vulnerable and to restrain a poison instilled in you that wants to take you over and consume you.

Search and you will come to the proper deduction that there is definitely some potent shadow that remains like some indelible and almost imperceptible pearl only when you set aside the white noise of the culture we’ve been conditioned to accept all around us.

Now we have a right to be angry at an injustice done to us. We have a right to speak out strongly against it and hope to alter the surrounding circumstances that keep creating such similar injustices.

You are under no requirement to continue any interaction with anyone who has hurt you----you are also well in your right to warn others of the behavior of someone still living an unchecked life of victimizing...

....Yet, if we hope to rise above the ones who hurt us, if we even hope to create a miracle---a very profound and sublime miracle of healing in a way that transcends beyond the way the physical body can be healed and can actually create subtle reverberations in our culture-then we must get acquainted with what has now become the incomprehensibly alien notion of forgiveness and the ability to forgive our enemies (for they do exist)-even if just from a distance.

0 notes

Photo

Looking south towards the southeast corner of Central Park, 1858. This view is from atop the State Arsenal, which was designed by Martin E. Thompson and completed in 1851. In 1856, Mayor Fernando Wood approved the purchase of a large tract of land to the north of the city for a park, and created a Board of Commissioners to control it. Nearby Jones’ Wood was briefly considered before the Commissioners decided on a more central location, which they recognized would significantly boost #realestate values. Engineer Egbert Viele came up with a plan for the park, but it was not used, and a competition was held to find a plan for the park. 33 entries were submitted, and Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s Greensward Plan won the competition. Following the adoption of their plan, crews began tearing down structures and removing residents from the land. Over 1,600 people were evicted, many of whom were residents of Seneca Village, a vibrant community of blacks and immigrants that was established in 1825; it was located to the west of the old Croton Reservoir, near 86th Street (the foundations of what is thought to be the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church can be seen in the grass near the Spector playground). Taming the land was an immense undertaking. More than 2.5 million cubic yards of dirt and stone were removed, each load taken out in wagons. Workers labored from 6 A.M. to 5 P.M. six days a week, earning an average of $1.25 per hour. Over the course of construction, twenty thousand laborers were employed. Roughly a fifth of the workers were skilled workers, including blacksmiths, stonecutters, and gardeners who helped craft the park into the idyllic playground that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux imagined. The Lake was the first section of the park to open, as it was a wildly popular place for people to skate in the winter and boat in the #summer. Most of the park was finished by 1863, although later that year the boundaries of the park, which formerly ended at 106th Street, were extended to 110th Street, which included the historic McGowan’s Pass and the Harlem Meer #NYC #CentralPark #GrandArmyPlaza #NYCParks #history #NYChistory #DiscoveringNYC via ✨ @padgram ✨(http://dl.padgram.com) https://www.instagram.com/p/BWPU91CgCIP/

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Just a little history while on my walk through Bronx Park. Here is what the sign says: "Olinville playground bears the name of the Bronx neighborhood of Olinville, named after the author, professor and Methodist bishop, Stephen Olin (1797-1851). A tiny village that emerged in the 1840s as a result of the New York and Harlem Railroad, Olinville originally began as two distinct settlements, Olinville No.1 and Olinville No.2, separated by Olin Avenue. The villages were eventually incorporated between 1852 and 1854. Stephen Olin was born in Leicester, Vermont. He became an instructor at Tabernacle Academy in South Carolina in 1820, was admitted on trial as a preacher to the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1824, and was ordained in 1826. He became professor of ethics and belles-lettres at the University of Georgia in 1827, and from 1834 to 1837, he served as the first President of Randolph-Macon College, a recently founded Methodist institution in Virginia. Renowned as one of the most powerful and fervent preachers of his day, he served as President of Wesleyan University in Connecticut from 1842 to 1851. He wrote with the same zeal with which he preached, contributing to the Christian Advocate and Journal and writing numerous books. Travels in Egypt, Arabia, Petraea, and the Holy Land was published in 1843, but the majority of his works were released posthumously. These include The Works of Stephen Olin (1852), Life and Letters (1853), Greece and the Golden Horn (1854), and College Life and Practice (1867)." #StephenOlin #Olinville #Bronx #BronxHistory #BronxPark #NewYorkCityHistory #NYCHistory #NewYorkHistory #NYC #TouristinNYC #History #Historia #Histoire #HistorySisco (at Bronx Park)

#stephenolin#historysisco#newyorkcityhistory#nyc#bronxhistory#olinville#historia#touristinnyc#histoire#history#newyorkhistory#bronx#bronxpark#nychistory

1 note

·

View note

Text

This is America

If you haven’t heard Donald Glover’s (A.K.A Childish Gambino) ground-breaking number 1 single “This is America” this week, then you’ve likely been living under a rock (or perhaps you aren’t hooked up to the media sphere for life-support like 99% of the world’s population – so congrats). But “This is America” is hugely significant to the politics of today, being both informed by and a reaction to the state of America in 2018, and carrying a crucial message in terms of gun crime and the treatment of black people in the USA.

With already over 100 million views on YouTube within the first week of release, Glover’s latest piece of art has undeniably gone viral, and so the question on everyone’s lips is – why?

Well, not least because of the fact that it is a ‘good song’, “This is America” has gone viral for political reasons. It stands to make a statement in the current sociological climate of the USA, just as McLuhan predicted that electronic media would call upon ethnic minorities for more in-depth participation (as discussed in the first blog of this series). Since we know that the likes of YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are so immensely popular in modern society, it makes sense that activists and artists alike turn to these platforms to get their voices heard. “This is America” is woven with both subtle and not-so subtle political indicators, such as references to Jim Crow; the Horsemen of the Apocalypse; and the 2015 massacre at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

However, one of the most prominent themes to emerge within the video is that of media indifference, represented through the children’s mimicry of Gambino’s exaggerated dance moves. The children can be seen to copy his every move despite the fires and executions that surround them. This can be seen as a representation of the kind of viral videos that we use to distract ourselves the realities of society (remember the Harlem Shake?).

Yet even after the children become aware of the dangers surrounding them, they return back to their dancing within moments, as if having forgotten the very real threat that they just faced. Here, Glover is aiming to represent how the media is quick to shift coverage back towards pop culture despite the very real issues that America faces with regards to gun crime, racism, and police brutality (to name but a few), highlighting the cyclical nature of reactions towards violence in America.

Ironically, despite the severity of the message behind “This is America”, just as the internet does when a popular work enters the mainstream consciousness, Glover’s work has fallen victim to countless online reconfigurations. Be it the “This is America, so call me maybe” YouTube “hit”, or memes about getting soap in your eye, it seems that even a viral video about the consequences of the media on society cannot hide from that exact problem.

This epidemic highlights societies obsession with digital media.

What’s more important, the 13,000 fatalities by cause firearm each year in the US, or your social media popularity?

0 notes

Text

Lost and found department: synagogues of Manhattan

Illustration by A Journey through NYC religions Ellen Levitt is one of the most interesting detectives in the city. Her job as a writer is finding lost synagogues. The book about her sleuthing in Manhattan, Staten Island and Governeur’s Island is available for purchase. The Last Synagogues of Manhattan is a densely packed treasure trove of architectural observations, naming practices, and…

#Abelardo Berrios#B&039;nai Menasheh#Beit Knesset HaGadol#Beth Ha-Knesset Ha Gadal#Congregation B’nai Israel#Ellen Levitt#Iglesia Pentecostal Camino A Damasco#John Lugo#La Sinagoga#Methodist Episcopal Church of the Savior#Nachlath Svi#Nachlath Zvi B’nai Israel Linoth Hazedek B’nai Menashe#South Harlem Methodist Episcopal Church#The Lost Synagogues of Manhattan

0 notes

Text

A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American labor unionist, civil rights activist, and socialist politician.

In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly African-American labor union. In the early Civil Rights Movement and the Labor Movement, Randolph was a voice that would not be silenced. His continuous agitation with the support of fellow labor rights activists against unfair labor practices in relation to people of color eventually led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 in 1941, banning discrimination in the defense industries during World War II. The group then successfully pressured President Harry S. Truman to issue Executive Order 9981 in 1948, ending segregation in the armed services.

In 1963, Randolph was the head of the March on Washington, which was organized by Bayard Rustin, at which Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his "I Have A Dream" speech. Randolph inspired the "Freedom Budget", sometimes called the "Randolph Freedom budget", which aimed to deal with the economic problems facing the black community, it was published by the Randolph Institute in January 1967 as "A Freedom Budget for All Americans".

Early life and education

Randolph was born April 15, 1889, in Crescent City, Florida, the second son of the Rev. James William Randolph, a tailor and minister in an African Methodist Episcopal Church, and Elizabeth Robinson Randolph, a skilled seamstress. In 1891, the family moved to Jacksonville, Florida, which had a thriving, well-established African-American community.

From his father, Randolph learned that color was less important than a person's character and conduct. From his mother, he learned the importance of education and of defending oneself physically against those who would seek to hurt one or one's family, if necessary. Randolph remembered vividly the night his mother sat in the front room of their house with a loaded shotgun across her lap, while his father tucked a pistol under his coat and went off to prevent a mob from lynching a man at the local county jail.

Asa and his brother, James, were superior students. They attended the Cookman Institute in East Jacksonville, the only academic high school in Florida for African Americans. Asa excelled in literature, drama, and public speaking; he also starred on the school's baseball team, sang solos with the school choir, and was valedictorian of the 1907 graduating class.

After graduation, Randolph worked odd jobs and devoted his time to singing, acting, and reading. Reading W. E. B. Du Bois' The Souls of Black Folk convinced him that the fight for social equality was most important. Barred by discrimination from all but manual jobs in the South, Randolph moved to New York City in 1911, where he worked at odd jobs and took social sciences courses at City College.

Marriage and family

In 1913 Randolph courted and married Mrs. Lucille Campbell Green, a widow, Howard University graduate, and entrepreneur who shared his socialist politics. She earned enough money to support them both. The couple had no children.

Early career

Shortly after Randolph's marriage, he helped organize the Shakespearean Society in Harlem. With them he played the roles of Hamlet, Othello, and Romeo, among others. Randolph aimed to become an actor but gave up after failing to win his parents' approval.

In New York, Randolph became familiar with socialism and the ideologies espoused by the Industrial Workers of the World. He met Columbia University Law student Chandler Owen, and the two developed a synthesis of Marxist economics and the sociological ideas of Lester Frank Ward, arguing that people could only be free if not subject to economic deprivation. At this point, Randolph developed what would become his distinctive form of civil rights activism, which emphasized the importance of collective action as a way for black people to gain legal and economic equality. To this end, he and Owen opened an employment office in Harlem to provide job training for southern migrants and encourage them to join trade unions.

Like others in the labor movement, Randolph favored immigration restriction. He opposed African Americans' having to compete with people willing to work for low wages. Unlike other immigration restrictionists, however, he rejected the notions of racial hierarchy that became popular in the 1920s.

In 1917, Randolph and Chandler Owen founded The Messenger with the help of the Socialist Party of America. It was a radical monthly magazine, which campaigned against lynching, opposed U.S. participation in World War I, urged African Americans to resist being drafted, to fight for an integrated society, and urged them to join radical unions. The Department of Justice called The Messenger "the most able and the most dangerous of all the Negro publications." When The Messenger began publishing the work of black poets and authors, a critic called it "one of the most brilliantly edited magazines in the history of Negro journalism."

Soon thereafter, however, the editorial staff of The Messenger became divided by three issues – the growing rift between West Indian and African Americans, support for the Bolshevik revolution, and support for Marcus Garvey's Back-to-Africa movement. In 1919, most West Indian radicals joined the new Communist Party, while African-American leftists – Randolph included – mostly supported the Socialist Party. The infighting left The Messenger short of financial support, and it went into decline.

Randolph ran on the Socialist Party ticket for New York State Comptroller in 1920, and for Secretary of State of New York in 1922, unsuccessfully.

Union organizer

Randolph's first experience with labor organization came in 1917, when he organized a union of elevator operators in New York City. In 1919 he became president of the National Brotherhood of Workers of America, a union which organized among African-American shipyard and dock workers in the Tidewater region of Virginia. The union dissolved in 1921, under pressure from the American Federation of Labor.

His greatest success came with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who elected him President in 1925. This was the first serious effort to form a labor institution for employees of the Pullman Company, which was a major employer of African Americans. The railroads had expanded dramatically in the early 20th century, and the jobs offered relatively good employment at a time of widespread racial discrimination. Because porters were not unionized, however, most suffered poor working conditions and were underpaid.

Under Randolph's direction, the BSCP managed to enroll 51 percent of porters within a year, to which Pullman responded with violence and firings. In 1928, after failing to win mediation under the Watson-Parker Railway Labor Act, Randolph planned a strike. This was postponed after rumors circulated that Pullman had 5,000 replacement workers ready to take the place of BSCP members. As a result of its perceived ineffectiveness membership of the union declined; by 1933 it had only 658 members and electricity and telephone service at headquarters had been disconnected because of nonpayment of bills.

Fortunes of the BSCP changed with the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. With amendments to the Railway Labor Act in 1934, porters were granted rights under federal law. Membership in the Brotherhood jumped to more than 7,000. After years of bitter struggle, the Pullman Company finally began to negotiate with the Brotherhood in 1935, and agreed to a contract with them in 1937. Employees gained $2,000,000 in pay increases, a shorter workweek, and overtime pay. Randolph maintained the Brotherhood's affiliation with the American Federation of Labor through the 1955 AFL-CIO merger.

Civil rights leader

Through his success with the BSCP, Randolph emerged as one of the most visible spokespeople for African-American civil rights. In 1941, he, Bayard Rustin, and A. J. Muste proposed a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in war industries, an end to segregation, access to defense employment, the proposal of an anti-lynching law and of the desegregation of the American Armed forces. Randolph's belief in the power of peaceful direct action was inspired partly by Mahatma Gandhi's success in using such tactics against British occupation in India. Randolph threatened to have 50,000 blacks march on the city; it was cancelled after President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, or the Fair Employment Act. Some activists, including Rustin, felt betrayed because Roosevelt's order applied only to banning discrimination within war industries and not the armed forces. Nonetheless, the Fair Employment Act is generally considered an important early civil rights victory.

And the movement continued to gain momentum. In 1942, an estimated 18,000 blacks gathered at Madison Square Garden to hear Randolph kick off a campaign against discrimination in the military, in war industries, in government agencies, and in labor unions. Following passage of the Act, during the Philadelphia transit strike of 1944, the government backed African-American workers' striking to gain positions formerly limited to white employees.

Buoyed by these successes, Randolph and other activists continued to press for the rights of African Americans. In 1947, Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil disobedience. When President Truman asked Congress for a peacetime draft law, Randolph urged young black men to refuse to register. Since Truman was vulnerable to defeat in 1948 and needed the support of the growing black population in northern states, he eventually capitulated. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman abolished racial segregation in the armed forces through Executive Order 9981.

In 1950, along with Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, and, Arnold Aronson, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council, Randolph founded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). LCCR has been a major civil rights coalition. It coordinated a national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.

Randolph and Rustin also formed an important alliance with Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1957, when schools in the south resisted school integration following Brown v. Board of Education, Randolph organized the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom with Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1958 and 1959, Randolph organized Youth Marches for Integrated Schools in Washington, DC. At the same time, he arranged for Rustin to teach King how to organize peaceful demonstrations in Alabama and to form alliances with progressive whites. The protests directed by James Bevel in cities such as Birmingham and Montgomery provoked a violent backlash by police and the local Ku Klux Klan throughout the summer of 1963, which was captured on television and broadcast throughout the nation and the world. Rustin later remarked that Birmingham "was one of television's finest hours. Evening after evening, television brought into the living-rooms of America the violence, brutality, stupidity, and ugliness of {police commissioner} Eugene "Bull" Connor's effort to maintain racial segregation." Partly as a result of the violent spectacle in Birmingham, which was becoming an international embarrassment, the Kennedy administration drafted civil rights legislation aimed at ending Jim Crow once and for all.

Randolph finally realized his vision for a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, which attracted between 200,000–300,000 to the nation's capital. The rally is often remembered as the high-point of the Civil Rights Movement, and it did help keep the issue in the public consciousness. However, when President Kennedy was assassinated three months later, Civil Rights legislation was stalled in the Senate. It was not until the following year, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, that the Civil Rights Act was finally passed. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed. Although King and Bevel rightly deserve great credit for these legislative victories, the importance of Randolph's contributions to the Civil Rights Movement is large.

Religion

Randolph avoided speaking publicly about his religious beliefs to avoid alienating his diverse constituencies. Though he is sometimes identified as an atheist, particularly by his detractors, Randolph identified with the African Methodist Episcopal Church he was raised in. He pioneered the use of prayer protests, which became a key tactic of the civil rights movement. In 1973, he signed the Humanist Manifesto II.

Death

Randolph died in his Manhattan apartment on May 16, 1979. For several years prior to his death, he had a heart condition and high blood pressure. He had no known living relatives, as his wife had died in 1963, before the March on Washington.

Awards and accolades

In 1942, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People awarded Randolph the Spingarn Medal.

In 1953, the IBPOEW (Black Elks) awarded him their Elijah P. Lovejoy Medal, given "to that American who shall have worked most successfully to advance the cause of human rights, and for the freedom of Negro people."

On September 14, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Randolph with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In 1967 awarded the Eugene V. Debs Award

In 1967 awarded the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award. It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII that calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations.

Named Humanist of the Year in 1970 by the American Humanist Association.

Named to the Florida Civil Rights Hall of Fame in January 2014.

Legacy

Randolph had a significant impact on the Civil Rights Movement from the 1930s onward. The Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama was directed by E.D. Nixon, who had been a member of the BSCP and was influenced by Randolph's methods of nonviolent confrontation. Nationwide, the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s used tactics pioneered by Randolph, such as encouraging African Americans to vote as a bloc, mass voter registration, and training activists for nonviolent direct action.

In buildings, streets, and trains

Amtrak named one of their best sleeping cars, Superliner II Deluxe Sleeper 32503, the "A. Philip Randolph" in his honor.

A. Philip Randolph Academies of Technology, in Jacksonville, FL, is named in his honor.

A. Phillip Randolph Boulevard in Jacksonville, Florida, formerly named Florida Avenue, was renamed in A. Phillip Randolph's honor. It is located on Jacksonville's east side, near EverBank Field.

A. Philip Randolph Campus High School (New York City High School 540), located on the City College of New York campus, is named in honor of Randolph. The school serves students predominantly from Harlem and surrounding neighborhoods.

The A. Philip Randolph Career Academy in Philadelphia, Pa was named in his honor.

The A. Philip Randolph Career and Technician Center in Detroit, MI is named in his honor.

The A. Philip Randolph Institute is named in his honor.

PS 76 A. Philip Randolph in New York City, NY is named in his honor

A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is in Chicago's Pullman Historic District.

Edward Waters College in Jacksonville, Florida houses a permanent exhibit on the life and accomplishments of A. Philip Randolph.

Randolph Street, in Crescent City, Florida, was dedicated to him.

A. Philip Randolph Library, at Borough of Manhattan Community College

A. Philip Randolph Square park in Central Harlem was renamed to honor A. Philip Randolph in 1964 by the City Council, under a local law introduced by Council Member J. Raymond Jones and signed by Mayor John V. Lindsay. In 1981, a group of loosely organized residents began acting as stewards of the park, during the dark days of abandonment and disinvestment in Central Harlem. By 2010 that group, now the Friends of A. Philip Randolph Square--founded by Gregory C. Baggett, who named longterm residents Ms. Gloria Wright; Ms. Ivy Walker; and Mr. Cleveland Manley, as Trustee of the park--would be formally incorporated to provide better stewardship and programming at a time when the neighborhood would be undergoing rapid growth and diversification. In 2018, the Friends of A. Philip Randolph Square would further expand the scope of its work beyond stewardship over the park to prepare a major revitalization plan "to improve conditions in the park and the neighborhood around the park" operating under a new entity, the A. Philip Randolph Neighborhood Development Alliance that seeks to obtain broad neighborhood and community representation for its revitalization plan based on building the personal and collective assets within the neighborhood.

Arts, entertainment, and media

+ 1994 Documentary A. Philip Randolph: For Jobs and Freedom, PBS

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed A. Philip Randolph on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

The story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was made into the 2002 Robert Townsend film 10,000 Black Men Named George starring Andre Braugher as A. Philip Randolph. The title refers to the demeaning custom of the time when Pullman porters, all of whom were black, were just addressed as "George".

A statue of A. Philip Randolph was erected in his honor in the concourse of Union Station in Washington, D.C..

In 1986 a nine-foot bronze statue of Randolph by Tina Allen was erected in Boston's Back Bay commuter train station.

On February 3, 1989, the United States Postal Service issued a 25-cent postage stamp in Randolph's honor.

Other

James L. Farmer, Jr., co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), cited Randolph as one of his primary influences as a Civil Rights leader.

Randolph is a member of the Labor Hall of Fame.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Madam C. J. Walker

Sarah Breedlove (December 23, 1867 – May 25, 1919), known as Madam C. J. Walker, was an African American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and a political and social activist. Eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America, she became one of the wealthiest African American women in the country, "the world's most successful female entrepreneur of her time," and one of the most successful African-American business owners ever.

Walker made her fortune by developing and marketing a line of beauty and hair products for black women through Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, the successful business she founded. Walker was also known for her philanthropy and activism. She made financial donations to numerous organizations and became a patron of the arts. Villa Lewaro, Walker’s lavish estate in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, served as a social gathering place for the African American community.

Early life

Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, near Delta, Louisiana, to Owen and Minerva (Anderson) Breedlove. Sarah was one of six children, which included an older sister, Louvenia, and four brothers: Alexander, James, Solomon, and Owen Jr. Breedlove's parents and her older siblings were enslaved on Robert W. Burney's Madison Parish plantation, but Sarah was the first child in her family born into freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. Her mother died, possibly from cholera, in 1872; her father remarried, but he died within a few years. Orphaned at the age of seven, Sarah moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, at the age of ten and worked as a domestic. Prior to her first marriage, she lived with her older sister, Louvenia, and brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.

Marriage and family

In 1882, at the age of fourteen, Sarah married Moses McWilliams, possibly to escape mistreatment from her brother-in-law. Sarah and Moses had one daughter, Lelia McWilliams, born on June 6, 1885. When Moses died in 1887, Sarah was twenty; Lelia was two years old. Sarah remarried in 1894, but left her second husband, John Davis, around 1903 and moved to Denver, Colorado, in 1905.

In January 1906, Sarah married Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman she had known in Missouri. Through this marriage, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker. The couple divorced in 1912; Charles died in 1926. Lelia McWilliams adopted her stepfather's surname and became known as A'Lelia Walker.

Career

In 1888 Sarah and her daughter moved to Saint Louis, Missouri, where three of her brothers lived. Sarah found work as a laundress, barely earning more than a dollar a day, but she was determined to make enough money to provide her daughter with a formal education. During the 1880s, Breedlove lived in a community where ragtime music was developed—she sang at the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and started to yearn for an educated life as she watched the community of women at her church. As was common among black women of her era, Sarah experienced severe dandruff and other scalp ailments, including baldness, due to skin disorders and the application of harsh products such as lye that were included in soaps to cleanse hair and wash clothes. Other contributing factors to her hair loss included poor diet, illnesses, and infrequent bathing and hair washing during a time when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing, central heating and electricity.

Initially, Sarah learned about hair care from her brothers, who were barbers in Saint Louis. Around the time of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World's Fair at St. Louis in 1904), she became a commission agent selling products for Annie Turnbo Malone, an African American hair-care entrepreneur and owner of the Poro Company. While working for Malone, who would later become Walker’s largest rival in the hair-care industry, Sarah began to adapt her knowledge of hair and hair products to develop her own product line.

In July 1905, when she was thirty-seven years old, Sarah and her daughter moved to Denver, Colorado, where she continued to sell products for Malone and develop her own hair-care business. Following her marriage to Charles Walker in 1906, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker and marketed herself as an independent hairdresser and retailer of cosmetic creams. (“Madam” was adopted from women pioneers of the French beauty industry.) Her husband, who was also her business partner, provided advice on advertising and promotion; Sarah sold her products door to door, teaching other black women how to groom and style their hair.

In 1906 Walker put her daughter in charge of the mail order operation in Denver while she and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern United States to expand the business. In 1908 Walker and her husband relocated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where they opened a beauty parlor and established Lelia College to train "hair culturists." After closing the business in Denver in 1907, A'lelia ran the day-to-day operations from Pittsburgh, while Walker established a new base in Indianapolis in 1910. A'lelia also persuaded her mother to establish an office and beauty salon in New York City's Harlem neighborhood in 1913.

In 1910 Walker relocated her business to Indianapolis, where she established the headquarters for the Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. She initially purchased a house and factory at 640 North West Street. Walker later built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents, and added a laboratory to help with research. She also assembled a competent staff that included Freeman Ransom, Robert Lee Brokenburr, Alice Kelly, and Marjorie Stewart Joyner, among others, to assist in managing the growing company. Many of her company's employees, including those in key management and staff positions, were women.

To increase her company's sales force, Walker trained other women to become "beauty culturists" using "The Walker System", her method of grooming that was designed to promote hair growth and to condition the scalp through the use of her products. Walker's system included a shampoo, a pomade stated to help hair grow, strenuous brushing, and applying iron combs to hair. This method claimed to make lackluster and brittle hair become soft and luxurious. Walker's product line had several competitors. Similar products were produced in Europe and manufactured by other companies in the United States, which included her major rivals, Annie Turnbo Malone's Poro System and later, Sarah Spencer Washington's Apex System.

Between 1911 and 1919, during the height of her career, Walker and her company employed several thousand women as sales agents for its products. By 1917 the company claimed to have trained nearly 20,000 women. Dressed in a characteristic uniform of white shirts and black skirts and carrying black satchels, they visited houses around the United States and in the Caribbean offering Walker's hair pomade and other products packaged in tin containers carrying her image. Walker understood the power of advertising and brand awareness. Heavy advertising, primarily in African American newspapers and magazines, in addition to Walker's frequent travels to promote her products, helped make Walker and her products well known in the United States. Walker became even more widely known by the 1920s as her business market expanded beyond the United States to Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Panama, and Costa Rica.

In addition to training in sales and grooming, Walker showed other black women how to budget, build their own businesses, and encouraged them to become financially independent. In 1917, inspired by the model of the National Association of Colored Women, Walker began organizing her sales agents into state and local clubs. The result was the establishment of the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents (predecessor to the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union of America). Its first annual conference convened in Philadelphia during the summer of 1917 with 200 attendees. The conference is believed to have been among the first national gatherings of women entrepreneurs to discuss business and commerce. During the convention Walker gave prizes to women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents. She also rewarded those who made the largest contributions to charities in their communities.

Activism and philanthropy

As Walker's wealth and notoriety increased, she became more vocal about her views. In 1912 Walker addressed an annual gathering of the National Negro Business League (NNBL) from the convention floor, where she declared: "I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground." The following year she addressed convention-goers from the podium as a keynote speaker.

Walker helped raise funds to establish a branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in Indianapolis's black community, pledging $1,000 to the building fund for the Senate Avenue YMCA. Walker also contributed scholarship funds to the Tuskegee Institute. Other beneficiaries included Indianapolis's Flanner House and Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church; Mary McLeod Bethune's Daytona Education and Industrial School for Negro Girls (which later became Bethune-Cookman University) in Daytona Beach, Florida; the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina; and the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in Georgia. Walker was also a patron of the arts.

About 1913 Walker's daughter, A'Lelia, moved to a new townhouse in Harlem, and in 1916 Walker joined her in New York, leaving the day-to-day operation of her company to her management team in Indianapolis. In 1917 Walker commissioned Vertner Tandy, the first licensed black architect in New York City and a founding member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, to design her house in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York. Walker intended for Villa Lewaro, which cost $250,000 to build, to become a gathering place for community leaders and to inspire other African Americans to purse their dreams. She moved into the house in May 1918 and hosted an opening event to honor Emmett Jay Scott, at that time the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the U.S. Department of War.

Walker became more involved in political matters after her move to New York. She delivered lectures on political, economic, and social issues at conventions sponsored by powerful black institutions. Her friends and associates included Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, and W. E. B. Du Bois, among others. During World War I Walker was a leader in the Circle For Negro War Relief and advocated for the establishment of a training camp for black army officers. In 1917 she joined the executive committee of New York chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which organized the Silent Protest Parade on New York City's Fifth Avenue. The public demonstration drew more than 8,000 African Americans to protest a riot in East Saint Louis that killed thirty-nine African Americans.

Profits from her business significantly impacted Walker's contributions to her political and philanthropic interests. In 1918 the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC) honored Walker for making the largest individual contribution to help preserve Frederick Douglass’s Anacostia house. Prior to her death in 1919, Walker pledged $5,000 (the equivalent of about $65,000 in 2012) to the NAACP's antilynching fund. At the time it was the largest gift from an individual that the NAACP had ever received. Walker bequeathed nearly $100,000 to orphanages, institutions, and individuals; her will directed two-thirds of future net profits of her estate to charity.

Death and legacy

Walker died on May 25, 1919, from kidney failure and complications of hypertension at the age of fifty-one. Walker's remains are interred in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

At the time of her death Walker was considered to be the wealthiest African American woman in America. She was eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America, but Walker's estate was only worth an estimated $600,000 (approximately $8 million in present-day dollars) upon her death. According to Walker's New York Times obituary, "she said herself two years ago [in 1917] that she was not yet a millionaire, but hoped to be some time." Her daughter, A'Lelia Walker, became the president of the Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company.

Walker's personal papers are preserved at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis. Her legacy also continues through two properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Villa Lewaro in Irvington, New York, and the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Villa Lewaro was sold following A'Lelia Walker's death to a fraternal organization called the Companions of the Forest in America in 1932. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has designated the privately-owned property a National Treasure. Indianapolis's Walker Manufacturing Company headquarters building, renamed the Madame Walker Theatre Center, opened in December 1927; it included the company's offices and factory as well as a theater, beauty school, hair salon and barbershop, restaurant, drugstore, and a ballroom for the community. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

In 2006, playwright and director Regina Taylor wrote The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove, recounting the history of Walker’s struggles and success. The play premiered at the Goodman Theater in Chicago. Actress L. Scott Caldwell played the role of Walker.

On March 4, 2016, skincare and haircare company Sundial Brands launched a collaboration with Sephora in honor of Walker’s legacy. The launch, titled “Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture”, comprised four collections and focused on the use of natural ingredients to care for different types of hair.

Tributes

Various scholarships and awards have been named in Walker's honor:

The Madam C. J Walker Business and Community Recognition Awards are sponsored by the National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Oakland/Bay Area chapter. An annual luncheon honors Walker and awards outstanding women in the community with scholarships.

Spirit Awards are sponsored the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Established as a tribute to Walker, the annual awards have honored national leaders in entrepreneurship, philanthropy, civic engagement, and the arts since 2006. Awards presented to individuals include the Madame C. J Walker Heritage Award as well as young entrepreneur and legacy prizes.

Walker was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca, New York, in 1993. In 1998 the U.S. Postal Service issued a Madam Walker commemorative stamp as part of its Black Heritage Series.

Wikipedia

0 notes