#South Africa third wave

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i really do wish gentiles understood how utterly decimated the jewish diaspora was by the end of the 20th century in the wake of the wave of pogroms in eastern europe, the shoah and its aftermath, and the expulsions across north africa and south west asia. in the early 1900’s, around 50% of the world’s jewish population lived outside of eretz yisrael or the us. today, that number is 13%. there are countries who had large jewish populations at the turn of the 20th century that now have no jewish presence. there has not been such a large wave of expulsions and fleeing since the spanish inquisition — which is another horrifically traumatizing series of events that gentiles don’t understand the enormity of.

during the spanish inquisition, almost half a million jews were forced on pain of death to convert or flee. thousands were killed, hundreds of thousands fled. until the shoah, it was the single most massive trauma in jewish history since the siege of jerusalem and expulsion from judea. jews made up nearly a quarter of spain’s population and had been there for centuries. some of our most important texts were written there. ladino developed there, sephardic music, culture, and identity. and then it was gone. everywhere the inquisition could reach, from spain to naples to sicily to malta to the americas, the jewish populations were brutalized, genocided, and expelled. it changed the course of jewish history forever.

in the 20th century, within the span of 50ish years, hundreds of thousands of jews were killed in or fled horrific pogroms in eastern europe, a third of the entire jewish population was systematically murdered within the span of a few years, centuries old jewish communities weren’t just expelled but almost entirely wiped out which led to the loss of centuries old diaspora languages and traditions, and nearly a million jews were expelled from places they’d lived for hundreds or even thousands of years.

like. do you understand? do you understand the kind of communal trauma that kind of massive global upheaval has on a people? the expulsion of 300,000+ jews from spanish territories was enough to leave a centuries old mark on the jewish community. do you understand the impact that the murder of over six million and violent displacement of over 2 million jews will have on the jewish psyche and on jewish history? do you have any idea how earth shattering the last century has been for the jewish people? do you have any idea what we’ve lost? what’s been violently stolen from us? can you try?

962 notes

·

View notes

Photo

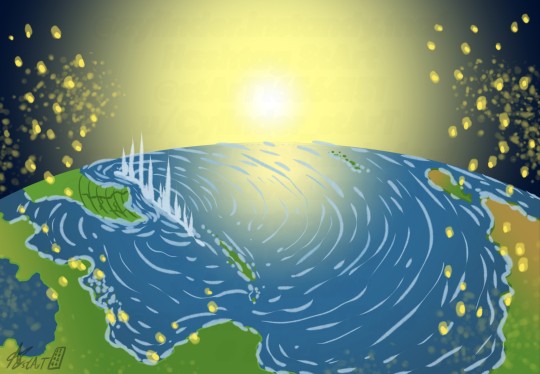

Polynesian Navigation & Settlement of the Pacific

Polynesian navigation of the Pacific Ocean and its settlement began thousands of years ago. The inhabitants of the Pacific islands had been voyaging across vast expanses of ocean water sailing in double canoes or outriggers using nothing more than their knowledge of the stars and observations of sea and wind patterns to guide them.

The Pacific Ocean is one-third of the earth's surface and its remote islands were the last to be reached by humans. These islands are scattered across an ocean that covers 165.25 million square kilometres (63.8 million square miles). The ancestors of the Polynesians, the Lapita people, set out from Taiwan and settled Remote Oceania between 1100-900 BCE, although there is evidence of Lapita settlements in the Bismarck Archipelago as early as 2000 BCE. The Lapita and their ancestors were skilled seafarers who memorised navigational instructions and passed their knowledge down through folklore, cultural heroes, and simple oral stories.

The Polynesian's highly developed navigation system impressed the first European explorers of the Pacific and since then scholars have been debating several questions:

was the migration and settlement of the Pacific islands and into Remote Oceania accidental or intentional?

what were the specific maritime and navigational skills of these ancient seafarers?

why has a large body of indigenous navigational knowledge been lost and what can be done to preserve what remains?

what type of sailing vessels and sails were used to cross an open ocean?

Ancient Voyaging & Settlement of the Pacific

By at least 10,000 years ago, humans had migrated to most of the habitable lands that could be reached on foot. What remained was the last frontier – the myriad islands of the Pacific Ocean that required boat technology and navigational methods be developed that were capable of long-range ocean voyaging. Near Oceania, which consists of mainland New Guinea and its surrounding islands, the Bismarck Archipelago, the Admiralty Islands, and the Solomon Islands was settled in an out-of-Africa migration c. 50,000 years ago during the Pleistocene period. These first settlers of the Pacific are the ancestors of Melanesians and Australian Aboriginals. The small distances between the islands in Near Oceania meant that people could island-hop using rudimentary ocean-going craft.

The so-called second wave of migration into Remote Oceania has been an intensely debated scholarly topic. Remote Oceania is the islands to the east of the Solomon Islands group such as Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Society Islands, Easter Island, and the Marquesas. What is debated is the origins of the first people who settled in this region between 1500-1300 BCE, although there is general agreement that the ancestral homeland was Taiwan. A dissenting view has been that of Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002 CE) who set out in 1947 CE on a balsa raft called Kon-Tiki that he hoped would prove a South American origin for Pacific islanders. Archaeological and DNA evidence, however, points strongly to a southeast Asian origin and seafarers who spoke a related group of languages known as Austronesian who reached Fiji in 1300 BCE and Samoa c. 1100 BCE. All modern Polynesian languages belong to the Austronesian language family.

Collectively, these people are called the Lapita and were the ancestors of the Polynesians, including Maori, although archaeologists use the term Lapita Cultural Complex because the Lapita were not a homogenous group. They were, however, skilled seafarers who introduced outriggers and double canoes, which made longer voyages across the Pacific possible, and their distinctive pottery – Lapita ware – appeared in the Bismarck Archipelago as early as 2000 BCE. Lapita pottery included bowls and dishes with complex geometric patterns impressed into clay by small toothed stamps.

Between c. 1100-900 BCE, there was a rapid expansion of Lapita culture in a south-east direction across the Pacific, and this raises the question of intentional migration.

Continue reading...

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

In May, pro-independence demonstrations spread across New Caledonia, a small Pacific island territory that has been ruled by France since 1853. Waving the flags of the Indigenous Kanak people as well as the flag of the pro-independence Socialist National Liberation Front, demonstrators took to the streets to protest voting reform measures that would give greater political power to recently arrived Europeans.

Curiously, however, they also waved another flag—that of Azerbaijan. Although the similar colors of the New Caledonian and Azerbaijani flags led some to speculate whether the demonstrators had inadvertently acquired the wrong flag, other observers viewed the presence of the Azerbaijani flag as an indication of ideological support from Baku.

It turns out, the Azerbaijani flags were not mistaken. Since March 2023, Baku has strategically cultivated support for the New Caledonian independence movement under the guise of anti-colonial solidarity. As payback for French diplomatic backing of Armenia after Azerbaijan’s 2020 invasion of Nagorno-Karabakh, Baku has disseminated anti-French disinformation related to New Caledonia. Following the outbreak of protests this May, France publicly accused Azerbaijan of doing so.

Baku’s influence campaign successfully inflamed long-simmering hostilities toward French descendants in New Caledonia, culminating in violent demonstrations and riots, which triggered a visit by French President Emmanuel Macron—as well as French police forces—even though Macron ultimately issued a de facto suspension of the reforms.

The incident in New Caledonia is hardly an isolated one. Anti-colonialism, which rose as a powerful ideological force during the 1960s and 1970s, is having a resurgence, and its philosophical underpinnings continue to shape some of the biggest geopolitical crises of the day, from Gaza to Ukraine. But unlike the decolonization movements of the Cold War era, this wave is being driven by opportunistic illiberal regimes that exploit anti-colonial rhetoric to advance their own geopolitical agendas—and, paradoxically, their own colonial-style land grabs.

The basic aims of the decolonization movement during the Cold War were twofold: securing national independence for countries colonized by the West and preserving sovereignty for postcolonial countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, whether through armed struggle or ideological diplomacy. Focused on ending the Vietnam War and fighting white minority rule in southern Africa, the movement quickly became the cause célèbre of the international left.

Despite divergent views on economic and social issues, the movement’s proponents coalesced around a central belief that Western imperialism, particularly the U.S. variant, singlehandedly held back the advancement and development of what was then known as the third world—ignoring the fact that many anti-colonial movements often had their own internal issues of graft and corruption. Disheartened by the West’s history of imperialism, many on the left even embraced authoritarian leaders, such as Zimbabwe’s anti-colonial freedom fighter-turned-despot Robert Mugabe and even former North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung.

Today, the anti-colonial movement is less about securing independence for the few remaining colonial outposts or debating the proper developmental pathway for countries in the global south. Bolstered by powerful state-backed media corporations in the capitals of authoritarian states, the current movement is largely a Trojan horse for the advancement of global illiberalism and a revision of the international rules-based order.

Authoritarian governments in Eurasia have taken their influence operations to social media, where they hope to inflame grievances—possibly into actual conflicts—to divert the attention of Washington and its allies from areas of strategic importance. This is the case for not only Azerbaijan, but also for China in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as Iran, which provides financial support to anti-Israel protest groups in the United States.

But more than any other country, it is Russia that is attempting to ride the resurgent anti-colonial wave and position itself as a leading voice of the global south. Russian leadership describes itself as the vanguard of the “global majority” and claims to be leading “the objective process of building a more just multipolar world.”

After his visit to Pyongyang in June, Putin wrote in North Korea’s main newspaper that the United States seeks to impose a “global neo-colonial dictatorship” on the world. In the United States, several Russians alleged by prosecutors to be intelligence agents have been accused of funneling financial support to an anti-colonial Black socialist group to promote pro-Russian narratives and justify Russia’s illegal military actions in Ukraine. And in regard to New Caledonia, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova fanned the flames when she said in May that the tensions there stemmed “from the lack of finality in the process of its decolonization.”

Moscow’s primary stage to project itself as the spearhead of a new global anti-colonial movement is Africa. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union provided ideological and military support to numerous national liberation movements and anti-colonial struggles in sub-Saharan Africa on the grounds of proletarian internationalism and socialist solidarity. According to a declassified 1981 CIA report, Namibia’s SWAPO guerilla group received nearly all of its arms from the Soviet Union, and Soviet military personnel trained South African anti-apartheid guerrillas in Angola-based training camps. Moscow also trained and educated a large number of African independence fighters and anti-colonial rebels at Communist Party schools and military institutes back in the Soviet Union.

This legacy of Soviet internationalism and socialist goodwill generated lingering sympathy for the Kremlin, and Russia continues to be widely perceived as a torchbearer of anti-colonial justice and national independence on the continent, particularly in the Francophone Sahel region. Before his death in August 2023, former Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin blamed instability in the Sahel on Western interventionism, saying, “The former colonizers are trying to keep the people of African countries in check. In order to keep them in check, the former colonizers are filling these countries with terrorists and various bandit formations. Thus creating a colossal security crisis.”

Despite Moscow’s own imperialist legacy and its current war of recolonization in Ukraine, Russia is increasingly seen as an anti-Western stalwart in the Sahel and a key supporter of anti-French political movements. Kremlin-backed mercenaries from the Wagner Group’s successor, Africa Corps, have supplanted French security services as the primary counterinsurgency force for fragile West African governments. And in addition to the counter-insurgency operations, Russian mercenaries have provided personal protection for key African military and government leaders.

But the shift from French to Russian interventionism in the Sahel raises the question of just how much national sovereignty the governments in the affected countries have.

Military juntas in West Africa exploit anti-French sentiments among the general public in order to obscure the fact that they are merely relying on a different foreign state for regime security, effectively trading one colonialist power for another. Most importantly for the juntas, unlike the French, the Russian security forces have no qualms about violently cracking down on political dissent and committing war crimes. For example, in late March 2022, Russian mercenaries assisted the Malian military in summarily executing around 300 civilians in the Malian town of Moura, according to Human Rights Watch.

With its colonial baggage, France has struggled to penetrate pro-Russian propaganda in its former African colonies. For instance, Afrique Média, an increasingly popular Cameroon-based television network, often echoes the Kremlin’s positions on international events. In April 2022, Afrique Média promoted a Russia-produced propaganda video that depicted a Russian mercenary escaping his African jihadi captors and then revealing U.S, and French flags behind an Islamic State flag, suggesting that these Western countries are supporting religious extremists.

Russia’s anti-colonial crusade belies its efforts to advance its own political and economic interests. Moscow’s efforts in Africa are borne from a desire to undercut Western influence in the region; shore up diplomatic support for itself in multilateral forums, such as the United Nations; and reinstate Russia’s reputation as a global superpower. Moscow may also seek to secure access to Africa’s vast natural resources, including criterial minerals, and take advantage of illicit networks, such as illegal gold mining, to circumvent international sanctions and fund its war in Ukraine.

Authoritarian regimes, including those in Russia, China, and Azerbaijan, would not exploit anti-colonial rhetoric if it did not continue to resonate in the global south. Long-standing economic disparities with the global north and painful histories of Western interventionism, especially the post-9/11 U.S. wars in the Middle East, have fostered sympathy for revisionist authoritarian regimes. The current humanitarian crisis in Gaza has heightened feelings of Western hypocrisy among some commentators and public figures in the global south.

As Kenyan journalist Rasna Warah explains, “There is deep sympathy and support [in the West] for Ukrainians who are being bombed and made homeless by Russia but Palestinians being killed and being denied food and water are seen as deserving of their fate.”

Therefore, it is crucial for Western governments to acknowledge the shortcomings of the current international liberal order to governments in the global south, rather than attempting to gaslight them into believing that it is equitable and just. The Western-led international order has a long history of violence and instability in the developing world. The trauma of Western imperialism and colonialism should not be forgotten but rather reworked into developmental programs that help to build robust institutions and infrastructure in the global south.

For example, Germany’s joint declaration with Namibia in 2021, which acknowledged the genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples between 1904 and 1908, committed $1.2 billion over the next 30 years to funding aid projects in Namibia, which are more likely to have a long-lasting positive effect on the development of Namibian institutions than individual financial handouts to descendants of colonial-era violence.

In the near term, the United States and its Western allies should actively counter propaganda from Baku, Tehran, Moscow, and Beijing that seeks to portray these nations as free from interventionist pasts. Exposing their disinformation campaigns in the global south—starting with labeling social media accounts linked to state-run media—could help to alert the public to the presence of bad-faith actors, who exploit genuine anti-colonial grievances for their own political and economic goals.

While the Soviets were certainly no saints, there was a genuine internationalist and collectivist spirit in their interactions with the Cold War anti-colonial movement. The same cannot be said for Russia today.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"More than 150 workers whose labor underpins the AI systems of Facebook, TikTok and ChatGPT gathered in Nairobi on Monday [May 1st, 2023] and pledged to establish the first African Content Moderators Union, in a move that could have significant consequences for the businesses of some of the world’s biggest tech companies.

The current and former workers, all employed by third party outsourcing companies, have provided content moderation services for AI tools used by Meta, Bytedance, and OpenAI—the respective owners of Facebook, TikTok and the breakout AI chatbot ChatGPT. Despite the mental toll of the work, which has left many content moderators suffering from PTSD, their jobs are some of the lowest-paid in the global tech industry, with some workers earning as little as $1.50 per hour.

As news of the successful vote to register the union was read out, the packed room of workers at the Mövenpick Hotel in Nairobi burst into cheers and applause, a video from the event seen by TIME shows. Confetti fell onto the stage, and jubilant music began to play as the crowd continued to cheer.

The establishment of the Content Moderators Union is the culmination of a process that began in 2019, when Daniel Motaung, a Facebook content moderator, was fired from his role at the outsourcing company Sama after he attempted to convene a workers’ union called the Alliance. Motaung, whose story was first revealed by TIME, is now suing both Facebook and Sama in a Nairobi court. Motaung traveled from his home in South Africa to attend the Labor Day meeting of more than 150 content moderators in Nairobi, and addressed the group.

“I never thought, when I started the Alliance in 2019, we would be here today—with moderators from every major social media giant forming the first African moderators union,” Motaung said in a statement. “There have never been more of us. Our cause is right, our way is just, and we shall prevail. I couldn’t be more proud of today’s decision to register the Content Moderators Union.”

TIME’s reporting on Motaung “kicked off a wave of legal action and organizing that has culminated in two judgments against Meta and planted the seeds for today’s mass worker summit,” said Foxglove, a non-profit legal NGO that is supporting the cases, in a press release.

Those two judgments against Meta include one from April in which a Kenyan judge ruled Meta could be sued in a Kenyan court—following an argument from the company that, since it did not formally trade in Kenya, it should not be subject to claims under the country’s legal system. Meta is also being sued, separately, in a $2 billion case alleging it has failed to act swiftly enough to remove posts that, the case says, incited deadly violence in Ethiopia...

Workers who helped OpenAI detoxify the breakout AI chatbot ChatGPT were present at the event in Nairobi, and said they would also join the union. TIME was the first to reveal the conditions faced by these workers, many of whom were paid less than $2 per hour to view traumatizing content including descriptions and depictions of child sexual abuse. ...Said Richard Mathenge, a former ChatGPT content moderator... “Our work is just as important and it is also dangerous. We took an historic step today. The way is long but we are determined to fight on so that people are not abused the way we were.”

-via TIME, 5/1/23

[Note: In addition to Big Tech outsourcing and exploiting workers for social media and AI moderation, many companies also exploit and vastly underpay mostly overseas workers to straight up pretend to be AI. I'm really glad issues around this are starting to get attention AND UNIONS because exploited overseas labor is so often the backbone of AI--or even the "AI" itself.]

#labor unions#africa#kenya#south africa#open ai#chatgpt#facebook#meta#tiktok#workers rights#labor rights#exploitation#outsourcing#big tech#anti ai#nairobi#unionisation#unionize#good news#hope

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

🏮 20 years since that terrible day 🌊

December 26, 2004, 7:58 (local time), a terrible roar followed by an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 9.1 strikes off the coast of the northern island of Sumatra, Indonesia.

It will be remembered as the third most powerful earthquake in history.

But that's not all. The epicenter, located on the ocean floor, generates waves that reach 30 meters high. The tsunami causes more victims than the earthquake, sowing destruction even in countries that did not even feel the tremors.

Indonesia is the first to suffer the waves surges and cities like Banda Aceh, are completely reduced to plains of rubble and mud.

Other people pay a high price for their lives, without warnings or alarms, due to the then serious lack of monitoring systems in the Indian Ocean.

In the following hours, Thailand, Myanmar, India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Bangladesh and even the eastern coasts of Africa, Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania, Madagascar and South Africa, will suffer the same fate.

🇹🇭 🇲🇲 🇮🇳 🇲🇾 🇱🇰 🇲🇻 🇮🇩 🇧🇩 🇰🇪 🇸🇴 🇹🇿 🇲🇬 🇿🇦

The total number of victims was about 230,000, of which 20,000 were missing and never found. This will be, and is, remembered as one of the most violent disasters in history.

The world woke up to a disaster, but also to so much humanity, especially from other nations, helping, saving, donating and caring for those who had managed to survive.

Thanks: ONU, UNICEF, UNHCR, MediciSenzaFrontiere, SaveTheChildren, CARE, ICRC, IFRC, NOAA, WHO 🪷

#boxing day tsunami 2004#boxing day tsunami#tsunami 2004#tsunami#indian ocean tsunami#indian ocean tsunami 2004#never forget 2004#2004s#2004

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Faunus/White Fang plotline was NEVER inspired by the Irish Troubles/IRA

A few years ago, someone posted a "theory" about how the White Fang plotline was based, not on the American Civil Rights movements of the 1960s such as the Black Panthers and Martin Luther King's protests, but on a similar conflict in Europe that ran for much of the 20th century in the British occupation of Northern Ireland, known in short as "The Troubles."

Recently, I saw it again as someone stole the post so they could feel smart, so I want to put this to bed definitively as an Irish person:

The Faunus and White Fang plotline were never based on the Irish Troubles or the Irish Republican Army. To be frank I don't think Miles and Kerry know anything about Ireland outside of making drunk Paddy jokes in their off-hours. (wouldn't be the first nationality they've made fun of)

Barring that they were both Civil Rights Movements that happened in the general post-World War 2 wave of the 1960s alongside other countries like India and South Africa, the Troubles and Americian Civil Rights movements have little in common. The big dividing point is religion. The Troubles were a conflict that at its core was as much a sectarian divide as it was fighting against British oppression. The Protestant/Catholic divide is still active in Northern Ireland to this day, with people getting assaulted for wearing the wrong clothes or having the wrong names. The city still has dozens of "Peace walls" scattered around as remnants of the conflict. The religious/sectarian divide is at the heart of the Troubles; you cannot do a depiction of it without at least acknowleding that divide. Even Captain Planet managed this, for Christ's sake.

RWBY does not do this. There is no religious element to the White Fang unless you blink and squint at Fennic and Corsac- and they don't matter to the story at large outside of being minibosses in Volume 5 and they are the only White Fang agents who are vaugely religious. There's no religious element to the Faunus at large unless you look up supplementary material and read about the Faunus creation myths in the Fairy Tales of Remnant series. Trying to be inspired by The Troubles without referencing the sectarian part of it, is like trying to write an two-question essay when you only read the first half of the first question- i.e., you're going to fail miserably. Yeah, there was a conflict, and a question can be raised of how appropriate the use of violence was. And that's it. There's not even an Irish character in the show or anyone who uses an accent, so safe to 100% say, no. The Troubles were never on Miles and Kerry's mind when designing the Faunus racism.

Additionally, there is a silver bullet debunking the entire theory. All the way back in Volume 1 on the commentary track, Barbara Dunklemann said this:

"If anybody needs a comparison for what the Faunus are in this world, it's kind of like if you're in the 1930s/1940s and it's the way African American people were treated and viewed."

After someone else asks for clarification, Dunklemann then confirms they meant the 1960s and the Civil Rights Movement by name. No attempt is made to correct Dunklemann or say the White Fang was inspired by other Civil Rights movements- it is firmly, 100%, solely about the American movement.

There you have it- a quote from the crew itself confirming without a doubt that the Faunus and White Fang were always based on the Americian Civil Rights movement, with no mention of the Troubles or the Irish sectarian divisions. Attempting to say otherwise goes directly against stated intent from the beginning of the show.

Now please, don't let this stupid, asinine theory come back a third time, the next time a white RWBY fan gets uncomfortable at the racism in the White Fang plot, and reaches to a different civil rights conflict as a deflection tactic.

tldr- keep my country's history out of your mouth if you only care about using it to deflect blame on the catgirl racism subplot.

97 notes

·

View notes

Note

About this post, out of curiosity, when do you think it all started? Is there research on like how far back it goes? It obviously isn't inherent to human nature; I know it's not. Is it just one of those toxic things that started from the beginning of organized religion :( ?

There's research, but there's a lot of controversy on when/how patriarchy developed. The most important thing to note is that Greek/Roman/Chinese/Japanese style misogyny is not universal and has not always been the norm. Societies differed a lot in how much power and autonomy women had. At the same time, we must be conscious even the 'best' societies of the past still had faults surrounding women.

Some places to start are:

Alice Evans: Ten Thousand Years of Patriarchy: This article looks at it from an economic and cultural perspective. I strongly recommend reading her Substack, where she travels around the world interviewing Third World Women and Feminists to see why their women's liberation movements have succeeded or failed! From the linked article:

Our world is marked by the Great Gender Divergence. Objective data on employment, governance, laws, and violence shows that all societies are gender unequal, some more than others. In South Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, it is men who provide for their families and organise politically. Chinese women work but are still locked out of politics. Latin America has undergone radical transformation, staging massive rallies against male violence and nearly achieving gender parity in political representation. Scandinavia still comes closest to a feminist utopia, but for most of history Europe was far more patriarchal than matrilineal South East Asia and Southern Africa. [...] Why do some societies have a stronger preference for female cloistering? To answer that question, we must go back ten thousand years. Over the longue durée, there have been three major waves of patriarchy: the Neolithic Revolution, conquests, and Islam. These ancient ‘waves’ helped determine how gender relations in each region of the world would be transformed by the onset of modern economic growth.

Another thing to remember/consider when it comes to studying the past is how few resources we have. We only know so much about how pre-historical humans organized their societies. Colonialism destroyed evidence of other societies with different ways of approaching gender. Many of the great apes we study are endangered. And literate societies happened to be patriarchal societies (likely related to literacy going hand in hand with bureaucracy and agriculture and the development of a state?) so we don't know as much as we could about women in literate regions.

Organized religion definitely codified a lot about patriarchy, but the major religions (Christianity, Islam, Buddhism) arose in regions of the world that were already patriarchal. So it's kind of a chicken and the egg problem when it comes to patriarchy and religion. We know that religions that worshipped goddesses, like Greek and Roman paganism and Hinduism, can still coexist with sexist societies.

These aren't great answers, but it's a big question and there are a lot of people working on answering it! It ties back into the bigger question of what our human ancestors were like, and whether we're kind of doomed to violence and xenophobia or whether there are alternatives. Some other books I've read that may be useful reading on this front are:

The Dawn of Everything. A long book, but it's a tour of human history and different societies and ways of organizing society. One of the chapters is on women, if I recall correctly.

Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times. Women have been working with cloth for a very long time. In some societies, this allowed women a high degree of status (see the Minoans!) and in others, women were worked to the bone producing textiles (Ancient Egypt).

The book "Demonic Males" looks at the birth of patriarchy from a primatology perspective. Our ape ancestors show male-dominant behaviors and societies. It's controversial the extent this is directly responsible for misogyny and male violence, but I think it's likely that our ape inheritance influenced the structure of early humans - so we basically have a lot of baggage.

Broadly speaking, reading books on feminist anthropology will help you, because a lot of what we know about patriarchy is based on highly literate societies, which as we established, are also agricultural societies with bureaucracies and a hierarchical culture. That's hardly representative of the human condition. As an example, look at Inuit society - on the one hand, there is arranged marriage and all that it implies; on the other, we do not have the same ideals of silent women who stay at home - women are valued members of the society and their skills are explicitly recognized as necessary for survival. Compare Western cultures that view domestic tasks as "support" tasks while the "real" work is done by men.

Finally, this one is a bit old (1974), but it may give you a starting point for understanding feminist anthropology and the search for the origins of patriarchy: "Is Female to Nature as Male is to Culture". It can help us understand how female subordination manifests itself in different cultures, and to know what to look for.

I hope this has been helpful. If anyone can recommend good books on the origin of patriarchy/female subordination (especially for non-Western cultures), please feel free to add in the replies or reblogs!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello friends. Would you like to meet the antagonist of Faust's route? The dastardly entity responsible for untold pain and misery, for putting our intrepid couple through the metaphorical wringer? The arch-enemy of mankind for centuries??

(spoilers behind the cut)

Here you go! Yersinia pestis, or Y. pestis to its friends, in all its gram-negative, electron scanned, color enhanced glory.

Aww, but Mrs O, you say, it's so cute! Look at its widdle fimbriae waving hewwo! Its pastel pink Lisa Frank inspired palette!

But don't be fooled! This tiny cold-blooded killer is responsible for more deaths than possibly any other infectious agent in the history of humankind - we all know it as the bubonic plague. The Black Death. It's cut down hundreds of millions of people over the course of human history, and it is still a threat today.

Transmitted to humans primarily by the bite of fleas, Y. pestis is a nasty character - without treatment, mortality rates upon infection are 30% - 90%. It sets up shop in a nearby lymph node, gets busy, and the resulting damage causes tissues to die. Victims tend to develop large, swollen, and painful lymph nodes called buboes, which is where the illness gets the name 'bubonic plague'.

One thing to note though, for Faust's route, is that while we generally think of this type of plague as THE plague...there are two other forms an infection with Y. pestis can take. A septicemic infection, where the bacteria enter the blood stream rather than the lymph nodes and which is almost always fatal, and a pneumonic version. This one here is the stuff of epidemiology nightmares. It often is the result of inhaling airborne droplets from another infected individual, and it can spread from person to person very easily unlike the usual bubonic form which requires bodily contact or a bite from an infected flea. It causes fevers, weakness, and violently severe coughing, and without antibiotics is nearly 100% fatal in a frighteningly short period of time - most victims are dead within mere days. Sometimes hours.

The first major recorded outbreak of the bubonic plague was the Plague of Justinian, which began about 1,500 years ago in 541 CE and ravaged the Sasanian and Byzantine empires. It's estimated that the plague resulted in anywhere from 15 to 100 million deaths, up to 40% of the population of Constantinople at the time, and some historians believe people were dying at a rate of 5,000 per day in the capital city.

The second plague epidemic, the one many people are more familiar with, was the one we refer to as the Black Death. This epidemic began raging across Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia in the late 1330s, with Europe being hit particularly hard. By the time it was over Europe would see its population cut between 30% and 60%, and the Middle East losing about a third of its people as well. Numbers are difficult to estimate but they range from 75 -200 million dead.

There is, however, a third plague epidemic, although not as well known. In the 18th century the plague made a resurgence in SW China, remaining somewhat localized until the mid 19th century when it spread to Hong Kong and from there globally. There were outbreaks in the United States, India, many African countries, SE Asian countries, Russia, South America, the Caribbean, and most importantly for our story purposes - Europe. The largest outbreak was in Lisbon, but there were many smaller pockets of infection in various cities across the continent.

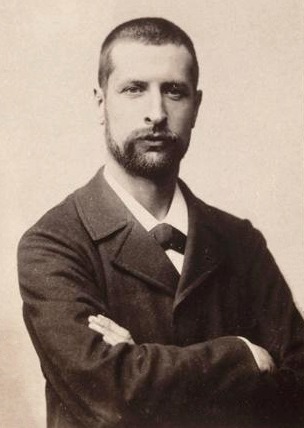

This was around the time the plague bacterium got its scientific name, Yersinia pestis, because of this man - a secondary character in our vampire love story, albeit with a slightly different name:

Say hello to Alexandre Yersin, a Swiss-French doctor and scientist.

Keenly interested in bacteriology, in 1886 he studied in Paris where Louis Pasteur was doing work in microbiology and worked on antiserum for rabies and antitoxin for diphtheria, two other famous scourges. (Antiserum, in the briefest of explanations, is basically a way to transfer antibodies from someone/something exposed to an infectious agent to a different person, thereby triggering the recipients immune system earlier and more vigorously EDITED TO ADD: this also applies to venom and this is actually how antivenom is made as well!)

In 1894, he was sent to Hong Kong to investigate the plague outbreak and it was here that he identified the bacteria responsible, the one that now bears his name, along with confirmation of its transmission route via rodents. (A Japanese scientist in Hong Kong at the same time, Kitasato Shibasaburou, independently identified the bacterium almost simultaneously as well, but because his documentations were not as clear it is Yersin who is generally credited with the initial find)

Yersin spent the next few years continuing his studies of the plague, traveling back to Paris in 1895 to develop the first anti-plague serum. It was the work of scientists like him, and so many others at this time, that paved the way for modern medicine and a path towards eradicating the diseases that have held us in their skeletal grip for so much of mankind's history.

...And perhaps, in the world of Ikevamp, that path owes just a little bit to a certain bespectacled German priest.

#ikemen vampire#ikevamp#ikevamp faust#spoiler#spoilers#ikemen vampire spoilers#ikevamp spoilers#how to tag this?#lore? background? idek#maybe just 'stuff i wish i'd known the first time i read his route'

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

When scholars around the world first began collecting data on civil wars, in the early nineties, they noticed an interesting correlation: Since 1946, right after World War II ended, the number of democracies in the world had surged—but so had the number of civil wars. They seemed to be rising in tandem.

The first wave of democratization began in 1870, when citizens in the United States and many Central and South American countries began to demand political reform. […]

The second wave emerged immediately after World War II, when newly defeated countries and post-colonial states tried to build their own democratic governments.

The third wave moved through East Asia, Latin America, and southern and Eastern Europe in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, when more than thirty countries transitioned to democracy.

The latest wave began to develop with the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and seemed to gain strength as Arab Spring protests spread across the Middle East and North Africa. Civil wars rose alongside democracies.

In 1870, almost no countries were experiencing civil war, but by 1992, there were over fifty. Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) were fighting one another in a fracturing Yugoslavia. Islamist rebel groups were turning on their government in Algeria. Leaders in Somalia and the Congo suddenly faced multiple armed groups challenging their rule, as did the governments in Georgia and Tajikistan. Soon the Hutus and the Tutsis would be slaughtering each other in Rwanda and Burundi. By the early nineties, the number of civil wars around the world had reached its highest point in modern history. That is, at least until now. In 2019, we reached a new peak.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Treat for your favourite character, if you would! :)

Oooh. This one will be fun! Let's see...

I feel kinda silly doing this but... Lemme introduce you to an OC I've never talked about on this blog before. She's technically a fandom OC, but for how much longer she'll stay that way, I can't say.

Meet one of my favorite original characters, Jill Cortez aka DJ Sunshine, my Dead by Daylight oc:

Running a radio station in the Realm wasn't all that easy. The first challenge was getting the place up and running. The second challenge was keeping it, and herself, safe from Killers and hostile Survivors.

The third challenge was finding music to play on the damn thing. Used to be she'd scavenge on her own, finding the technology that may still have musical gems hidden on it. Now she got other Survivors to do it, trading with them through the door, changing her voice so no one would recognize her.

It would be a shame for them to realize the truth, that DJ Sunshine was just boring, useless little Cortez.

As the music ended, she smiled into the microphone.

"Hello world! You're listening to WNTTY, the Fog. I'm your Sunshine! Let's talk."

And she talked, and she talked, and she talked. She talked like someone was listening, even though there was no proof of that.

"Thanks to your help, I've added several thousand new songs to my collection! Great work, all of you! Unfortunately a lot of them are not in English, so I have no idea what they're saying or who is singing them. I'll be playing batches of these now and then. If you recognize the language, song, or singer, leave a note at the station door, or text me at--"

She talked and talked and talked.

"Shout-out to the weirdo who sent me a dick pic, by the way. You're a real piece of shit, and I'm not gonna save you from the hook if we're in a Trial together. Asshole."

She talked. Talked. Talked.

"So here's your question of the day: is love real? Romantic love. Obviously you can love your family or your cat, but is that feeling you get with that one person an actual, separate kind of love? I think a lot of our emphasis on it is just marketing taking advantage of loneliness and a desire for sex. But hey, I've never been in love, what would I know?"

Talking, talking, talking. And as she talked, everything felt alright.

"Anyway! That's my thirty minutes up! We're back to two hours of sweet, sweet tunes. Let's start with early millennium America, jump on over to the British Invasion of the 60s, take a detour to Germany and South Africa, and finish up with the Korean Wave. I have no idea what half of these songs are talking about, but they're fun to listen to, so into the mix they go. Enjoy!"

What do you guys think? Think she's got protagonist potential? I need to finish her fic sometime...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amoricide [Dead by Daylight Dark Soulmate AU - Trickster/Survivor!OC]

Amoricide The act of killing your soulmate Chapter 3: Crush Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Warnings: Blood, but that's about it

Shoutout to @vincent-sinclair-deserved-better for giving me the dopamine hit to go 'fuck it' and post this after having it finished for longer than I want to say.

Her mark was bleeding again. Sunshine grimaced, lifting her arm off the desk. Blood smeared on her skin and the old metal surface. She snatched a rag from the floor and wiped the desk off. The mark would take more effort. But with the music going, two more songs before her entrance, she had plenty of time.

Sunshine tossed the headset on the desk and rolled her chair towards the shelves on the opposite wall. She stopped herself with her foot, reached up for the bandages on the middle shelf, then rolled back to her desk with all her laptops and all her creations.

Running a radio station in the Realm wasn't all that easy. The first challenge was getting the place up and running. The second challenge was keeping it, and herself, safe from Killers and hostile Survivors.

The third challenge was finding music to play on the damn thing. Used to be she'd scavenge on her own, finding the technology that may still have musical gems hidden on it. Now she got other Survivors to do it, trading with them through the door, changing her voice so no one would recognize her.

It would be a shame for them to realize the truth, that DJ Sunshine was just boring, useless little Cortez.

As the music ended, she smiled into the microphone.

"Hello world! You're listening to WNTTY, the Fog. I'm your Sunshine! Let's talk."

And she talked, and she talked, and she talked. She talked like someone was listening, even though there was no proof of that.

"Thanks to your help, I've added several thousand new songs to my collection! Great work, all of you! Unfortunately a lot of them are not in English, so I have no idea what they're saying or who is singing them. I'll be playing batches of these now and then. If you recognize the language, song, or singer, leave a note at the station door, or text me at--"

She talked and talked and talked.

"Shout-out to the weirdo who sent me a dick pic, by the way. You're a real piece of shit, and I'm not gonna save you from the hook if we're in a Trial together. Asshole."

She talked. Talked. Talked.

"So here's your question of the day: is love real? Romantic love. Obviously you can love your family or your cat, but is that feeling you get with that one person an actual, separate kind of love? I think a lot of our emphasis on it is just marketing taking advantage of loneliness and a desire for sex. But hey, I've never been in love, what would I know?"

Talking, talking, talking. And as she talked, everything felt alright.

"Anyway! That's my thirty minutes up! We're back to two hours of sweet, sweet tunes. Let's start with early millennium America, jump on over to the British Invasion of the 60s, take a detour to Germany and South Africa, and finish up with the Korean Wave. I have no idea what half of these songs are talking about, but they're fun to listen to, so into the mix they go. Enjoy!"

Button presses, a flip of the switch, and there it was, Toxic by Britney Spears traveling through the airwaves. Sunshine exhaled and took off her headset, leaning back in her chair. There was something so satisfying about this job… And exhausting, too. She'd never been a people person, always insecure, but it was easier to work with them from the safety of her radio station. It was almost like she could be her true self.

The mark had soaked through the bandages. Sunshine raised her arm to look at it again. How was it that it could bleed for hours and she didn't feel sick at all? It never bled before she came to this place. Maybe the Entity had something to do about it.

Right. She stood from her chair and stretched. Bandage her arm again, check the perimeter, then… she glanced at one laptop in particular. She'd work on her secret project. The idea of it made her smile.

There were reasons to keep going, even in a place like this.

---

It'd just been lying in the middle of the street. He'd stopped, looking down at it, tilted his head to the side. An old radio, outdated by over thirty years, without a single dent or smear of dirt on it.

A cute antique. Trickster took it with him, and if anyone cared, no one complained.

He wasn't much for old technology, but he could tell this was meant for Americans by how ugly it was. For such an influential country, they had hideous toys. But it worked. Somehow, the thing worked. Didn't make a sound, but at least it turned on. Trickster screwed around with it, fiddling with the knobs, and he smiled.

Music burst through. Trickster jerked back. He backed away from the table, part of him glad no one could see his surprise. Music - bullshit. How was that possible? He hadn't heard music on anything but his phone since…

The song stopped, and a voice came over the line.

"I'm your Sunshine!"

Trickster blinked, and listened.

He sat down, and listened. And listened. And listened.

"So I can't do any research on these guys, since there's no Internet here, but I'm really enjoying their sound. Like, I'll play it again when I take a break, so check it out - you hear the violin or something in the background? You wouldn't think about it but I think it adds a lot to the song, and the whole, y'know, theme of it."

Finally, he thought. Someone else gets it.

"I've really been thinking about making my own stuff, cause of this job. I mean, I don't really have anything better to do, aside from… die a lot."

How did a Survivor do this? He laced his hands under his chin, listening. Listening.

"I'll be honest, I can't play any instruments. I don't know anything about major or minor keys, that kind of stuff, but I've always really liked music. Music can keep you alive, you know? Well, not in this place but, I think you get me, right?"

"I do," he mumbled.

He listened.

He enjoyed.

The station host left as quickly as she came on, leaving music in her wake. Trickster reached to turn it off… but didn't. She mentioned the Korean Wave… would she play one of his songs?

Damn it, he thought. Now I have to keep it on.

So he did. And when he hunted down his so called soulmate days later, it was one of the songs Sunshine played he was humming.

#dbd fic#dbd oc survivor#trickster x oc#dead by daylight oc#dead by daylight au#dead by daylight fic#dbd fanfic

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crunchyroll Announces the Premiere Time for the Third Season of The Rising of the Shield Hero Anime

Crunchyroll has announced that it will begin simulcasting the third season of The Rising of the Shield Hero anime on October 6, 2023 at 5:30 a.m. PDT. The simulcast will be available in North America, Central America, South America, Europe, Africa, Oceania, the Middle East and CIS. The anime is described as: Learning that other nations are enduring the Calamity Waves, Naofumi vows to fight. But…

youtube

View On WordPress

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

COP28 was more than a summit for African nations acutely vulnerable to climate disasters despite being the least responsible for carbon pollution. Africans hoped it could be a pivotal moment where the world’s climate crisis would be confronted head-on.

That hope was almost dashed entirely but salvaged at the last minute. Early on in the negotiations to draft the final text, instead of agreeing on a fossil fuel phasedown deal, a historic commitment that would have lit the path out of Africa’s deepening climate despair, the COP28 draft agreement fell far short.

There have been important strides taken by the host nation. Before the summit, the United Arab Emirates had pledged to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, the first Middle Eastern country to do so. And the UAE’s COP28 presidency put forward an ambitious agenda, mobilizing nearly $84 billion in funding and launching a $30 billion catalytic fund, Altérra, to mobilize up to $250 billion for positive climate action – all in the first five days. This COP has also seen the World Bank increase its commitment by an additional $9 billion annually for climate projects—not to mention $22.6 billion toward climate action provided by multilateral development banks on top of that. And the loss and damage fund, so far raising more than $700 million, was a breakthrough.

But given the scale of the crisis, this is not nearly enough. For African nations, the stakes have never been higher. The relentless march of climate change threatens to render large areas of our land uninhabitable within mere decades—not to mention potentially unleashing a massive wave of climate refugees toward the West.

That’s why it was so disconcerting that OPEC heavyweights like Saudi Arabia, along with major economies including China and India, had ruled out calls for a fossil fuel phasedown, let alone a phaseout. Indeed, China and Russia shielded coal—the dirtiest of fuels—from criticism.

And how exactly were these nations justifying their refusal to curb emissions? In the guise of supporting the global south, they claimed that curbing fossil fuel production is detrimental to economies that rely heavily on it, as many African nations do.

Yet they ignored the catastrophic impact of business-as-usual fossil fuel exploitation, which is a lethal blow to the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and a veritable death sentence for our countries. Exceeding 1.5 degrees would be disastrous for Africa, which produces the lowest per-capita emissions out of all continents. If nothing changes, approximately 250 million people in Africa could experience high water stress by 2030 due to climate change, impacting water availability for drinking, agriculture, and industry.

Africa’s hopes were about to be dashed on the rocks of political and economic self-interest. Yes, our economies are intertwined with fossil fuels, but the answer is not reckless continuation of fossil fuel production. The solution lies in a just and equitable transition to clean energy, underpinned by significant climate financing support from wealthier, industrialized nations. Without this, the idea of a fair transition simply does not hold up. Which is why African countries themselves said that they have no choice but to use fossil fuels if rich, industrialized nations refuse to provide funding for their green transition.

Saudi Arabia, India, and China had an opportunity to demonstrate that they are not stuck in the past but are instead ready to embrace the future. That means grappling constructively with the recognition that to retain a safe climate, the world must phase down fossil fuels. Doing so would be consistent with the fact that China and India are, respectively, the world’s first and third top renewable energy producers, with Saudi Arabia picking up the pace this year.

But it’s not just the major oil producers that almost derailed COP28 at the last hour. It’s also the United States and Europe that, despite ramping up their rhetoric in support of a fossil fuel phaseout, have failed to facilitate the climate finance needed to actually make it feasible.

Their calls thus left a sour taste for many African delegates. Many of us had experienced a sense of palpable hope around this critical issue when COP President Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber met with Kenyan President William Ruto during the Africa Climate Summit, where they agreed to support private-sector engagement in climate finance. To kick-start the initiative, the UAE invested over $13 billion to catalyze renewable energy projects across Africa.

In contrast, the failure of the U.S., U.K., and EU to back up their fossil fuel phaseout rhetoric with tangible mechanisms to make it financially viable—especially for the world’s developing nations—has alarmed many African leaders who feel we are being told we can have nothing: no fossil fuels for development, and no finance for a green transition . Without the financing to support a crash program in energy transformation, leaving fossil fuels in the ground would be a recipe to collapse into poverty.

Ultimately, without a drastic reduction in global fossil fuel production, Africa will continue suffering from escalating extreme weather events and natural disasters, leading to a greater need for funds to be directed toward climate disaster response and recovery, rather than proactive mitigation and adaptation efforts.

That is why the final COP28 agreement brokered by the UAE represents such a significant breakthrough. For the first time in history, we have a global climate agreement that formally recognizes the crucial significance of systematically reducing oil, gas, and coal use by incorporating the language of “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems.” That such an agreement was signed off by 198 countries was extraordinary. That it was the UAE, the seventh-largest oil producer in the world, that managed to bring the world’s biggest oil producers—including Saudi Arabia, Iraq, China, and Russia—onto the side of recognizing this transition seemed surprising but revealed that they needed one of their own to broker this stunning compromise.

There’s still much work to do. We lack a mechanism to unlock the trillions of dollars of finance necessary to back such a huge and complex transition. The richest, most industrialized nations that have watered down their financial commitments at every opportunity were eagerly pointing the finger—but it is they who have refused to put their money where their mouths are.

Ultimately, this is the first COP that has managed to rally 198 world governments behind a vision of a world after fossil fuels, backed by a goal of tripling renewable energy and doubling energy efficiency by 2030. That goal is enough to tackle up to three-quarters of the emissions reductions required by that year to avoid dangerous climate change.

There’s no avoiding the fact that global energy markets will receive an unmistakable message from this declaration: The future is renewable, and the age of fossil fuels will soon be behind us.

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

4.2.23

LISTEN TO THIS WEEK'S SHOW! THE GOA EXPRESS – “Portrait” (Communion Records, UK)

BROOKE COMBE – “Black Is The New Gold” (Island Records, UK)

TEENAGE DADS – “Midnight Driving” (Chugg Music, Australia)

HUNDRED REASONS – “So So Soon” (Fierce Panda/SO Recordings, UK)

CAITY BAISER – “Pretty Boys” (EMI Records, UK)

3REE – “Out Of My Mind” (Unsigned, Australia)

THE JORDAN – “I’m Not Sorry” (Unsigned, Holland)

TOM A. SMITH – “Little Bits” (Unsigned, UK)

KAMRAD – “Feel Alive” (Sony Music, Germany)

LOVEJOY – “Call Me What You Like” (Anvil Cat Records, UK)

THE ROYSTON CLUB – “Blisters” (Run On Records, UK)

MADYX – “Walking On The Moon” (Unsigned, N. America) THE LUKA STATE – “Two Worlds Apart” (Unsigned, UK)

MASI MASI – “Moaner Lisa” (Shabby Road, UK)

EMMI KING – “Set The Pace” (Unsigned, Germany)

NOBLE – “Lost In You” (Metrosonic Records, Portugal) BELDON HAIGH – “Dumpster Fire” (Unsigned, UK) TALISCO – “Human” (Talisco Music, France)

CIRCA WAVES – “Your Ghost” (Lower Third/[PIAS], UK)

REST FOR THE WICKED – “Fade Away” (EMI/UMG, Australia)

THE ACADEMIC – “My Very Best” (Capitol Records/EMI, UK)

MATTHEW MOLE – “Countryside” (Universal Music, South Africa)

INHALER – “When I Have Her On My Mind” (Polydor, Ireland)

RUM JUNGLE – “Back Home” (Sureshaker, Australia)

THE SHERLOCKS – “Sirens” (Unsigned, UK)

RHETT REPKO – “Tell Me That It’s Not Over” (Unsigned, N. America)

ALEX LAHEY – “Good Time” (Liberation, Australia)

HIGH TROPICS – “Girlfriends” (Unsigned, Australia)

SINGLE BY SUNDAY – “Severed Ties” (Unsigned, Scotland)

HARINA FT. DANNY BALDURSSON – “Done With You” (Aux Family, Germany) FELLY – “Bad Radio” (Unsigned, N. America)

LIME GARDEN – “Bitter” (So Young Records, UK)

PADDY ECHO – “Butterfly Kissing” (Unsigned, New Zealand)

LAUREN WALLER – “3-2-1” (Unsigned, N. America)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lula’s Out to Get Brazil’s Global Mojo Back

Like Biden, Brazil’s old-new president inherited a mess on the international stage.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, better known as Lula, stepped into his third term ready to rebuild Brazil’s international image, which had been largely diminished by his predecessor. And Lula has a guidebook to follow, not only from his two prior terms, but also from U.S. President Joe Biden’s ascension. From the Jan. 8 riots in Brasília to both countries reentering international organizations, Biden and Lula have fought—and will continue to fight—eerily similar battles.

“Both Lula and Biden are presidents that are positioning themselves as leaders in the democratic world, defending democracy in the region, and with clear priorities on the agenda,” said Bruna Santos, director of the Brazil Institute at the Wilson Center.

During his first two terms as president, between 2003 and 2010, Lula set Brazil up as a major economic and political player on the world stage. Lula was a founding member of BRICS—a geopolitical bloc including Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—and attended its first formal summit in 2009, and Brazil was one of the leading voices calling for U.N. Security Council expansion during the Lula administration. Brazil’s relationships with its neighbors had never been better, with a wave of Lula allies elected into office throughout the region, including Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in Argentina, Evo Morales in Bolivia, and Hugo Chávez in Venezuela.

But things may not be so straightforward this time around. Despite the recent wave of leftist governments echoing the political tides of the early 2000s, instability has rocked Latin America in recent years, with worsening situations in Nicaragua and Venezuela, violent protests in Peru, and the devastating economic and social impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. The new “pink tide” will be far more turbulent than the first.

“It’s very early on to see how successful he’s going to be, but it’s not going to be the easy ride he had on the first pink tide, when everyone was on better terms,” said Cecilia Tornaghi, the senior director of policy at Americas Society/Council of the Americas.

Continue reading.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

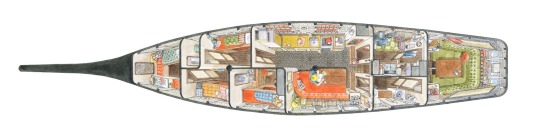

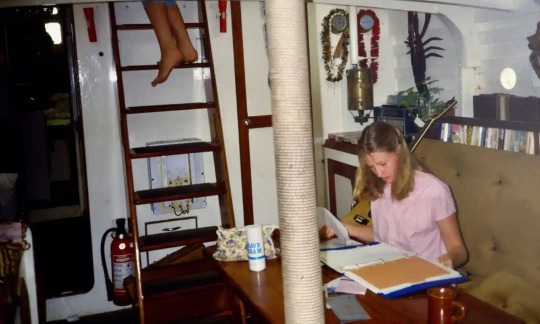

Heywood on the family boat Wavewalker, near Vanuatu in the South Pacific, 1987. Photograph: Courtesy of Suzanne Heywood

‘Dad Said: We’re Going To Follow Captain Cook’: How An Endless Round-The-World Voyage Stole My Childhood

In 1976, Suzanne Heywood’s Father Decided to Take the Family on a Three-Year Sailing ‘Adventure’ – and Then Just Kept Going. It was a Journey into Fear, Isolation and Danger …

— By Suzanne Heywood | March 25th, 2023 | The Guardian USA

When we lived in England my days had a familiar rhythm. Each morning, my mother flung open the curtains in my room, and I tugged my school jumper over my head and pulled on my skirt before tumbling downstairs to eat cereal with my younger brother Jon. After school, we’d play on the swing in our garden, or crouch at the far end of the stream to watch dragonflies hovering above the gold-green surface.

I was used to this rhythm; I liked it and thought it would never change. Until one morning over breakfast, my father announced that we were going to sail around the world.

I paused, a spoonful of cornflakes halfway to my mouth.

“We’re going to follow Captain Cook,” Dad said. “After all, we share the captain’s surname, so who better to do it?” He picked up his cigarette and leaned back in his seat.

“Are you joking?” I asked.

Next to me, Jon watched Dad, his lips parted.

“Not at all,” said my father, puffing out a cloud of smoke. “I’m deadly serious.”

“But why?”

“Well, someone needs to mark the 200th anniversary of Cook’s third voyage, don’t they?” he said, raising his eyebrows at my mother.

“Of course they do, Gordon,” said Mum, returning his smile.

“I’ve told you kids about the captain,” said Dad, stubbing out his cigarette in the ashtray. “He was an incredible man. The people who were going to recreate his first and second voyages didn’t get their act together in time, so this is the last opportunity.”

“How long will we be gone?” I asked.

“Three years. By the time we get back, you’ll have seen more places than most people will visit in a lifetime. We’ll sail down to South America, then cross the Atlantic Ocean to South Africa and Australia. From there, it’s on to Hawaii and Russia.”

The clock was ticking on the wall. I looked out of the window at the empty swing. Dad had taken us sailing before, but this was different.

One evening later that summer, Dad announced that he’d found a boat. A few weeks afterwards, we went down to the Isle of Wight to inspect his find. He marched ahead at the boatyard. “You’re going to love her, I know you will,” he said, and I looked up to see an enormous boat with a long, curved bow, two masts and a raised deck at the stern.

The interior was unfinished, but bunks and cupboards were already taking shape, half-formed in the gloom.

After a while, I went up on to the aft deck to sit next to my father in the cockpit, watching him attach a compass to the binnacle, the wooden instrument stand in front of the ship’s wheel. “She’s called Wavewalker,” he said. “We were lucky – I was able to buy her because the man who was building her ran out of money.”

“Wavewalker,” I said, exploring the edges of the word. This boat would walk us over the waves, carrying us around the world and back again.

“But you’re so normal,” people often say when they find out about my childhood. And in some ways, I am. But, even if it’s not visible, my experience of spending a decade sailing 47,000 nautical miles on Wavewalker, equivalent to circumnavigating the globe twice, shaped who I am today.

The family waving goodbye, Plymouth, 1976. Photograph: Courtesy of Suzanne Heywood

I started thinking again about my past when my children were old enough to ask me about it. Did Dad really sail around the world because he wanted to honour Captain Cook? Why didn’t my parents, middle class and well educated themselves, worry about their children’s education or social isolation? Why was my relationship with my mother so difficult, particularly during my teenage years, and why didn’t my father try to help, when he must have seen how miserable I was?

My parents always claimed our time on Wavewalker was wonderful and told me I’d had a privileged upbringing. But this oft-repeated mantra conceals a much darker story. What I found, when I mustered enough courage to look back, was that many parts of my childhood were worse than I’d been willing to admit.

When I set sail from England with my parents, brother and three crew members in the summer of 1976, I was seven and thought the trip was going to be like an extended, exciting summer holiday. Once we’d settled into our ocean routines, Mum began giving Jon and me some schoolwork to do in the mornings, usually a maths or English worksheet. It was convenient that we were only a year apart in age, she said, since it meant she could teach us together. When I asked about other subjects, such as history, art or science, she said she wasn’t going to bother with those – if we were good at maths and English, everything else would sort itself out. Anyway, our voyage was like a massive geography field trip.

One day, about a week after leaving Gran Canaria, and a month after leaving England, a shadow appeared above the ocean’s southern rim. “I think it’s Ilha de Santo Antão in the Cape Verde islands,” said Dad, “which means we’re about 400 miles off the most westerly tip of Africa and halfway to Rio.”

Heywood with her parents Mary and Gordon and brother Jon. Photograph: Courtesy of Suzanne Heywood

The shadow darkened and gained substance, becoming a craggy rock lurking under a cloud, while the ocean filled with writhing jellyfish. The heat built until, one day, the breeze rotated through every direction and disappeared. “We’ve hit the doldrums,” said Dad when I went to stand beside him on the deck, gazing out at an ocean of thick honey. “They happen where the north and south trade winds meet. But that’s supposed to be a hundred miles south of here.”

We sat sweating under a blue bowl of sky for several days after that, each breath a gasp of heat that scorched the lungs. When the sun was up, I danced across the parched deck, searching for patches of shade, while Dad made a saltwater shower from a bucket punctured with holes that he hung in the rigging. At night, I slept on deck to escape the stifling air below, lying on my sleeping bag, and reaching up to grasp handfuls of the stars peppering the Milky Way.

After the wind returned, we saw a passenger ship ploughing its way towards us from South America. It came so close that I could see the people crowding its balconies and rails to wave, and when it swept past I saw its name etched on the stern: Brazilla.

“I wish we’d asked them for food,” I said, watching it go.

Dad laughed. “Don’t be silly.”

“There’s no fresh fruit left,” I said, giving him my sad look. “And I hate salt tablets.”

Salt was taking over my life. White tidemarks of it bloomed on my skin; my clothes and sleeping bag were sticky with it; and now I had to eat it as well, to stave off dehydration.

An artist’s impression of the interior of Wavewalker. Illustration: Camilla Ashforth

“Do you want to try some ship’s biscuits?” asked Dad, and when I nodded, he showed me where he’d hidden the tins under the step outside the main head, the name for the ship’s toilet.

“Do they have raisins in them?” I asked.

He shook his head and peered at my biscuit. “Oh, don’t worry about those: they’re only weevils. Tap it sharply on the table, and most of them will fall out and crawl away. The rest will give you useful protein.”

From South America, we sailed on to apartheid South Africa. We then set off across the notorious southern Indian Ocean towards Australia, this time with two inexperienced crew members on board, as my father had by then decided that he preferred to teach people how to sail himself. My father was a hero to me and, it seemed, to everyone else; and my mother was his glamorous, if somewhat unwilling, and unmaternal, accomplice.

On the first day of the new year, when we were partway across the Indian Ocean, I opened my eyes to a world I wanted to leave. I wanted to go home. I dragged myself from my bunk, taking care to avoid being hurled back against it when the boat veered the other way. The main cabin was deserted, so I huddled by the table, holding Teddy, my small brown bear, and wondered if anyone else was hungry. When my father came down, I wedged Teddy into the bookcase and followed him into the chartroom.

“How is it up there, Dad?” I asked. “Are the waves getting any better?”

He looked at me, his face expressionless. “No. They’re worse. They’re now over 50ft high. And the wind has changed direction to blow at storm force straight from the south pole.”

“Oh.” The hairs prickled on my neck.

He turned to lean over his chart. “It’s not good,” he said. He spoke the words quietly, as if to himself. Wavewalker’s quivering moments at the summit of each wave had become longer, and her plunges forward more extreme. Everything felt wet: my skin, my clothes, my hair, the floor and every surface I touched.

My fear felt physical – a cold lump I carried in my stomach. Every so often, if the wind wailed or our movement down a wave was particularly steep, my heart pounded and my legs felt weak.

Jon had joined me at the table by the time Mum struggled down the ladder in her oilskins several hours later. “Put on your lifejackets,” she said. “We’re going too fast. We must be prepared.”

I didn’t ask how a lifejacket would help us survive in an ocean full of gigantic, icy waves, and neither did Jon. There was little point in arguing, and, anyway, Mum was already halfway back up into the cockpit. When she returned later, Jon and I were sitting trussed up in our jackets by the table.

“Sue, come and help me make some food,” said Mum. “I need a can of corned beef.”

I nodded, gripping the countertop rail with one hand while unlatching a cupboard door with the other. The cabin tipped backwards. Wavewalker was climbing another watery mountain. This time the pause was endless. It felt as if time had been suspended, leaving us balanced on the head of a monstrous wave.

There was an explosion, and chunks of decking collapsed inwards above my head, followed by an avalanche of cold, grey water. As the boat lurched on to its side, my fingers let go and I was flung against the ceiling and back on to the galley wall. The air filled with screams, some of them mine.

“Icy Water Flooded into the Boat. ‘Do You Think We’re Going to Die?’ Jon Asked. ‘Probably,’ I Said”

Some time passed, though I don’t know how much. When I opened my eyes, I was lying on the floor of the main cabin, half-covered in water and surrounded by pieces of crockery, sodden books and hunks of decking. Icy water, black, grey and foaming white, flooded in through a hole above me. Jagged beams hung down from the ceiling, and one side of the cabin bulged inwards.

Mum was near the ladder. She tilted her head back to shriek through the hatch: “We’re sinking, Gordon! There’s a hole in the deck, and she’s full of water.”

I couldn’t get up – my legs didn’t want to move, and all I wanted to do was sleep. Maybe I could rest here, I thought, the water a blanket around me.

When I opened my eyes again I was lying in one of the top bunks in the four-berth cabin. Below me, the floor was covered with water and bits of debris – books, cushions, pieces of wood. Wavewalker felt full and drunk, and each time she tilted, water poured in through the hatch in the ceiling.

“Stop crying,” said Jon. “You’ve been crying for ages.”

I saw him lying on the bottom bunk on the other side of the cabin. He was right. I was crying.

He was clutching a square biscuit tin.

“Want one?” he asked, holding it up.

“No.” I tried to shake my head, but the pain made me stop.

I was wet, everything around me was wet, and some of the wetness was red. I closed my eyes, exhausted by the pain in my head. Dad appeared. He leaned over my bunk, his eyes underlined with curved shadows, his cheeks and nose red and inflamed.

“Are you OK?” he asked.

“I don’t think so.” My voice was a whimper.

He touched my right forearm, and I glanced down to see that his forefinger was dyed crimson.

“Why didn’t you tell me how bad this was?”

“I didn’t want to worry you,” I said, but really he hadn’t been there to tell.

“Do you think we’re going to die?” Jon asked after our parents had left.

“Probably,” I said, trying to put the lifejacket on without moving my head or touching the swelling above my eye. The lump seemed to be growing. It was taking me over, a foreign thing embedded in my head.

Somehow – miraculously – Dad managed to navigate us over the next few days to a tiny island in the middle of the Indian Ocean: Île Amsterdam. Even more miraculously, we were still afloat when we reached it, due largely to the continuous pumping done by our two crew members, and the tarpaulin and quick-setting cement Dad had spread across the huge hole in our deck.

We were greeted on Île Amsterdam by Commandant Ghozi, who told us he was leading a French scientific mission of 30 people there. He took me to be examined by a thin man in a white coat named Dr Senellart. “She has a broken nose, a fractured skull and there is blood trapped inside the swelling on her head,” he told my parents when we rejoined them in the waiting room.

I slipped my hand inside Dad’s. “What if we do nothing?” he asked.

The family having tea at the helm. Photograph: Courtesy of Suzanne Heywood

“The swelling is pressing down on the fracture. If we do nothing, Monsieur Capitaine, your daughter could end up with brain damage. We must cut into the wound.”

For weeks, my mother kept taking me back to the tiny medical building where I underwent multiple operations on my head without anaesthetic, lying alone on the hospital bed. After my seventh operation, I went to find Mum in the waiting room.

“It is finished, Madame,” said Dr Senellart, following me in. “These,” he said, pointing to the shadows under my eyes, “will go in time. Your daughter is very brave.”

“I Was Nine And We Had Been Travelling For Two Years and 223 Days. Our Trip Was Supposed To Finish. But Dad Had Other Ideas.”

Mum, Jon and I were eventually rescued from Île Amsterdam by a passing container ship, while Dad sailed on with our two crew members to Fremantle in Australia in the dangerously damaged Wavewalker.

After repairing Wavewalker, we sailed from Fremantle to Sydney, and then across to New Zealand before turning north-east to make our way up to Hawaii. By the time we arrived in Honolulu, I was nine and we had been travelling for two years and 223 days. This was the point at which our trip was supposed to finish. Captain Cook had been killed in Hawaii, and we’d arrived there just over 200 years after his death.

But, of course, Dad had other ideas.

In Hawaii, the months turned into years while Dad tried various schemes to raise money, including working in a boatyard, setting up an exhibition on our trip and asking for donations. My 12th birthday came around and I gave up counting the days in my diary. I was learning nothing and was going crazy with boredom, since my parents – for reasons I never understood – had decided not to send us to school.

One night my father came home and said that we needed a family conference. The discussion took place over a dinner of corned beef and cabbage, spiced up with Tabasco sauce.

“Well, we can’t stay in Hawaii for ever,” he said. “I think we have two options. We’ve finished our voyage, so we could go home through the Panama Canal.”

We all nodded.

“Or we could sail back down the Pacific.”

I felt sick. It was the first time that Dad had suggested we might not go back to England

“But if we did that,” I asked, “when would we go home?”

“What’s the hurry? Think of all the places we haven’t seen. We haven’t even been to Tahiti yet.”

I put my hand on the sofa’s red plastic cover. He was listing more destinations – Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea. Mum was nodding and smiling.