#Social safety nets and poverty recovery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In the United States, eligible older adults are accessing means-tested safety net programs at low rates. Particularly, the participation rates of older adults in Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are exceedingly low. Recent data reveals that less than half of eligible adults ages 60 and older participated in SNAP in 2018. Although the recipiency of SSI among older adults is understudied, estimates indicate that since the program’s inception in the 1970s, their participation rate has hovered around 50%.

Participation rates in these programs are low, even with the existence of many outreach efforts. Examples include the SSI/Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) Outreach, Access, and Recovery (SOAR) model designed to increase participation among individuals who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness, and SNAP outreach that occurs at local food banks and pantries across the United States. Current application, determination, and enrollment processes for these programs involve numerous administrative barriers that, along with other factors, result in many individuals, including older adults, from accessing their entitled benefits. In addition, many program rules further discourage participation.

The financial situation of many low-income older adults, given that their income tends to remain generally constant over time, allows for a unique opportunity to reform application and enrollment processes for this specific population. The provisions outlined in this brief apply to beneficiaries receiving SSDI, in addition to older adults. As previously proposed to reduce Medicare premiums, a more automated approach can be applied to the application processes of SSI and SNAP. This reform would be a radical change from current program operations and is likely to result in higher participation rates in both programs. In this brief, we examine in greater detail the current levels of SSI and SNAP enrollment among older adults, illustrate why participation rates are stubbornly low, and describe a solution to this problem.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m not sure how reliably I’ll be able to keep up with it, but I’ve been wanting to start posting weekly or monthly Good News compilations, with a focus on ecology but also some health and human rights type stuff. I’ll try to keep the sources recent (like from within the last week or month, whichever it happens to be), but sometimes original dates are hard to find. Also, all credit for images and written material can be found at the source linked; I don’t claim credit for anything but curating.

Anyway, here’s some good news from the first week of March!

1. Mexican Wolf Population Grows for Eighth Consecutive Year

““In total, 99 pups carefully selected for their genetic value have been placed in 40 wild dens since 2016, and some of these fosters have produced litters of their own. While recovery is in the future, examining the last decade of data certainly provides optimism that recovery will be achieved.””

2. “Remarkable achievement:” Victoria solar farm reaches full power ahead of schedule

“The 130MW Glenrowan solar farm in Victoria has knocked out another milestone, reaching full power and completing final grid connection testing just months after achieving first generation in late November.”

3. UTEP scientists capture first known photographs of tropical bird long thought lost

“The yellow-crested helmetshrike is a rare bird species endemic to Africa that had been listed as “lost” by the American Bird Conservancy when it hadn’t been seen in nearly two decades. Until now.”

4. France Protects Abortion as a 'Guaranteed Freedom' in Constitution

“[A]t a special congress in Versailles, France’s parliament voted by an overwhelming majority to add the freedom to have an abortion to the country’s constitution. Though abortion has been legal in France since 1975, the historic move aims to establish a safeguard in the face of global attacks on abortion access and sexual and reproductive health rights.”

5. [Fish & Wildlife] Service Approves Conservation Agreement for Six Aquatic Species in the Trinity River Basin

“Besides conserving the six species in the CCAA, activities implemented in this agreement will also improve the water quality and natural flows of rivers for the benefit of rural and urban communities dependent on these water sources.”

6. Reforestation offset the effects of global warming in the southeastern United States

“In America’s southeast, except for most of Florida and Virginia, “temperatures have flatlined, or even cooled,” due to reforestation, even as most of the world has grown warmer, reports The Guardian.”

7. Places across the U.S. are testing no-strings cash as part of the social safety net

“Cash aid without conditions was considered a radical idea before the pandemic. But early results from a program in Stockton, Calif., showed promise. Then interest exploded after it became clear how much COVID stimulus checks and emergency rental payments had helped people. The U.S. Census Bureau found that an expanded child tax credit cut child poverty in half.”

8. The Road to Recovery for the Florida Golden Aster: Why We Should Care

“After a five-year review conducted in 2009 recommended reclassifying the species to threatened, the Florida golden aster was proposed for removal from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants due to recovery in June 2021, indicating the threats to the species had been reduced or eliminated.”

9. A smart molecule beats the mutation behind most pancreatic cancer

“Researchers have designed a candidate drug that could help make pancreatic cancer, which is almost always fatal, a treatable, perhaps even curable, condition.”

10. Nurses’ union at Austin’s Ascension Seton Medical Center ratifies historic first contract

“The contract, which NNOC said in a news release was “overwhelmingly” voted through by the union, includes provisions the union believes will improve patient care and retention of nurses.”

This and future editions will also be going up on my new Ko-fi, where you can support my art and get doodled phone wallpapers! EDIT: Actually, I can't find any indication that curating links like this is allowed on Ko-fi, so to play it safe I'll stick to just posting here on Tumblr. BUT, you can still support me over on Ko-fi if you want to see my Good News compilations continue!

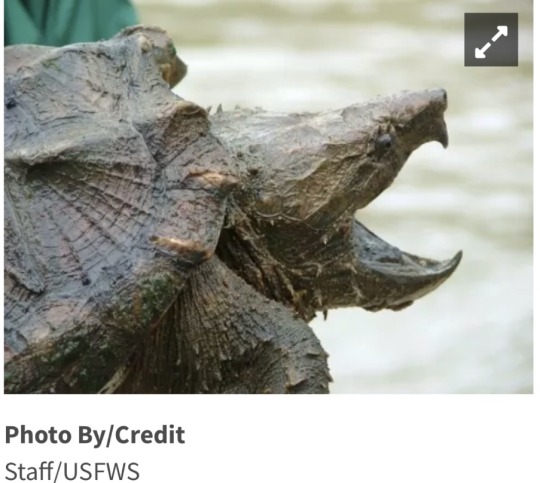

#hopepunk#good news#wolf#wolves#mexican wolf#conservation#solar#solar power#birds#abortion#healthcare#abortion rights#reproductive rights#reproductive health#fish and wildlife#turtles#alligator snapping turtle#snapping turtle#river#reforestation#global warming#climate change#climate solutions#poverty#social safety net#flowers#endangered species#cancer#science#union

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hrngh I just. I don't want to argue with people but. Being an addict is not a moral issue. You are not more morally good and pure for never having experienced addiction. You are not inherently bad for being an addict. Like the recovery narrative centres becoming a "better person" or being "redeemed" BUT BEING IN ACTIVE ADDICTION DOES NOT MAKE SOMEONE INHERENTLY A BAD PERSON. You don't need to be redeemed. That kind of dichotomous thinking is detrimental to recovery, setting people up to see relapse as a moral failure, a weakness in character, something they need to repent and self flagellate for. When it's just... not. It's a part of the process.

And even beyond that, if you can't bring yourself to uncouple addiction from morality, you have to see that addiction never happens in a vacuum. To ignore the socioeconomic factors that contribute, the way that addiction and alcoholism intersect frequently with chronic pain, the way that our society is essentially made hostile to people experiencing addiction which then in turn self-perpetuates... it seems needlessly cruel as well as ridiculously individualistic. Pull yourself up by your bootstraps type of mentality. Poverty and chronic pain are significant contributing factors in many cases of long term addiction; it is far more useful to blame power structures that allow people to remain in poverty, their pain untreated, the inequalities and failed safety nets, disregard for vulnerable populations, all amounting to social murder. Choosing instead to place blame and vitriol at the feet of addicts is unhelpful at best and frankly malicious at worst.

#this is not about one thing in particular just a combination of multiple things ive seen recently but it is getting to me a bit tbh#personal#alcohol#addiction#yes conversation today prompted this but also#frustrating anti harm reduction person earlier and general tone of conversation around these topics in general..#i'm sorry for going on about it and i don't want anyone to feel attacked but this. touched a nerve.#it's the moralising and the blaming and argh can we just be a bit more conscious of the language we're using idk#brain fog is 👍#oh and also mentioning recovery- harm reduction often involves what people who talk like this about addicts would get mad about anyway#people act like you have to do it as fast as possible and suffer the consequences bc you know. 'you did this to yourself'#< awful thing to say btw#but like. it takes time. it's more important for a person to be well than to be sober#completely lost my thread now sdfghjk

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

🧠 Leveraging the cultural and innovative strengths of the United States can provide a pathway out of the current economic climate by focusing on several key areas:

1. Stimulating Economic Growth Through Innovation

Investment in Technology and Research:

- Continued investment in technology and innovation can drive economic growth. Technological advancements create new industries and job opportunities. For instance, the tech sector, including companies like Apple, Google, and Amazon, contributes significantly to GDP and job creation.

- Research and Development (R&D) spending leads to new products and services, boosting productivity and economic expansion. In 2020, the U.S. spent over $600 billion on R&D, which is critical for maintaining its competitive edge.

2. Boosting Consumer Confidence and Spending

Cultural Exports:

- The entertainment industry, particularly Hollywood and the music industry, can stimulate economic activity through global exports. Movies, music, and related merchandise drive significant revenue, which supports various sectors within the economy.

- Streaming services and digital platforms can expand their global reach, increasing revenue streams and promoting U.S. cultural products abroad.

3. Enhancing Workforce Skills

Education and Training:

- Investing in education and skills training ensures that the workforce can adapt to changing economic conditions and technological advancements. Programs that focus on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) can prepare workers for high-demand fields.

- Online education platforms and alternative education models (e.g., coding bootcamps) can provide flexible and accessible learning opportunities, helping workers acquire new skills and improve their employability.

4. Fostering Entrepreneurship and Small Businesses

Support for Startups and Small Businesses:

- Encouraging entrepreneurship through grants, loans, and tax incentives can lead to the creation of new businesses and job opportunities. Startups, particularly in the tech sector, can drive innovation and economic growth.

- Public-private partnerships can provide the necessary support and resources for small businesses to thrive, fostering a dynamic and resilient economy.

5. Utilizing Soft Power and International Influence

Cultural Diplomacy:

- The global influence of American culture can be leveraged to enhance diplomatic relations and trade opportunities. By promoting cultural exchanges and international collaborations, the U.S. can strengthen its global position and create economic opportunities.

- Soft power, derived from cultural influence, can attract foreign investment and enhance the attractiveness of the U.S. as a business destination.

6. Encouraging Domestic Consumption

Stimulating Domestic Markets:

- Promoting domestic consumption through targeted fiscal policies can drive economic recovery. For instance, providing financial support to households can boost consumer spending, leading to increased demand for goods and services.

- Policies that support domestic industries, such as manufacturing and agriculture, can ensure that increased consumption benefits local businesses and worker.

7. Addressing Income Inequality

Note Sure Here: Universal Basic Income and Social Safety Nets:

- Implementing programs like Universal Basic Income (UBI) can provide a financial safety net, reducing poverty and inequality. By ensuring a basic level of income for all citizens, UBI can stimulate consumer spending and support economic stability.

- Strengthening social safety nets, including unemployment benefits and healthcare, can provide security for individuals, allowing them to invest in education and entrepreneurial activities.

Conclusion

By leveraging the cultural, innovative, and educational strengths of the United States, the economy can navigate through the current challenges and emerge stronger. Investment in technology, education, and entrepreneurship, combined with the global influence of American culture, provides a robust foundation for sustained economic growth and resilience.

References

1. [National Science Foundation](https://www.nsf.gov/)

2. [Federal Reserve](https://www.federalreserve.gov/)

3. [Harvard University](https://www.harvard.edu/)

4. [MIT](https://www.mit.edu/)

5. [Stanford University](https://www.stanford.edu/)

6. [Hollywood Industry Report](https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/)

7. [Music Industry Data](https://www.riaa.com/)

8. [Technology Market Analysis](https://www.techcrunch.com/)

9. [Global Innovation Index](https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/)

#business#myuberlife#cultureisdata#economics#mulfmab#beawolfaboutyourdream#federal reserve#philosophy#fashion#culture#art#jeff bezos#kendrick lamar#jey van-sharp#kwasi O Gyasi#winston peters#professor p#merica

0 notes

Text

From Triumph to Tragedy: COVID-19's Devastating Blow on Poverty Eradication

The year 2020 will forever be remembered as a time of unparalleled upheaval, as the COVID-19 pandemic took the world by storm, leaving behind a trail of destruction in its wake. Beyond the tragic loss of lives, the pandemic also unleashed a devastating blow on the global economy and disrupted social systems, derailing the remarkable progress made against poverty over the past four years. The journey towards eradicating poverty that had shown promising strides now stands overshadowed by a daunting reality. This article delves into the impact of COVID-19 on poverty eradication efforts, examining the setbacks, challenges, and potential pathways to recovery.

The Pre-COVID Progress

Before the pandemic struck, significant strides had been made in the battle against poverty. Numerous developing countries had reported declining poverty rates, improvements in education, and better access to healthcare. Global organizations like the World Bank and the United Nations were optimistic that we were moving closer to achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030.

Governments, NGOs, and philanthropic organizations were working together, implementing targeted interventions to lift millions out of poverty. Investments were being made in education and vocational training, empowering individuals with skills to secure better-paying jobs. Microfinance initiatives provided small loans to entrepreneurs, fostering local economic growth and self-sustainability. Moreover, access to healthcare has improved through the expansion of health facilities and immunization programs.

The Unforeseen Blow of COVID-19

Enter COVID-19, and the world witnessed an unprecedented human and economic crisis. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and social distancing measures were put in place to curb the spread of the virus, leading to the shutdown of businesses, the loss of jobs, and disruptions in supply chains. The most vulnerable segments of society were hit hardest, plunging many back into poverty.

Informal workers, day laborers, and those in the gig economy were left without job security or access to social safety nets. Women, who had made significant strides in the workforce, faced a disproportionate burden as they juggled work, childcare, and household responsibilities during the lockdowns.

The Toll on Global Poverty

According to the World Bank, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed an estimated 100 million people into extreme poverty in 2020, erasing more than four years of progress against poverty eradication. The setback was particularly severe in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where poverty rates surged due to the combined impact of health and economic crises.

School closures further exacerbated the situation, with millions of children unable to access education. This could have far-reaching consequences, as education is a crucial pathway to breaking the cycle of poverty. The disruption in education has the potential to create a lost generation of children who are deprived of the knowledge and skills they need to thrive in the future.

The Hidden Toll on Women

COVID-19 also exposed and amplified existing gender inequalities. Women, who often bear the brunt of poverty, found themselves at the frontline of the pandemic response, comprising the majority of healthcare workers and caregivers. Simultaneously, job losses and economic hardships disproportionately affected women, pushing them deeper into poverty.

Moreover, there was a surge in gender-based violence during lockdowns, as victims were confined with their abusers and faced barriers to seeking help. The pandemic further underscored the urgency of addressing gender disparities and promoting women's empowerment as critical components of poverty eradication efforts.

The Struggle for Access to Healthcare

The pandemic highlighted the glaring gaps in healthcare access and infrastructure in many developing countries. Overwhelmed healthcare systems struggled to provide adequate care to COVID-19 patients while maintaining essential health services for other diseases. This left millions without access to basic healthcare and life-saving treatments.

The economic fallout from the pandemic also affected funding for healthcare, diverting resources away from vital health initiatives. Immunization programs suffered, leading to potential outbreaks of preventable diseases that could disproportionately impact vulnerable communities already reeling from the pandemic's effects.

Climate Change and Poverty: A Two-Front Battle

As if battling a global pandemic was not challenging enough, countries also faced the looming threat of climate change. Climate-related disasters such as hurricanes, floods, and wildfires increased in frequency and intensity, exacerbating poverty and displacing communities.

Vulnerable populations living in low-lying coastal regions or arid areas faced the brunt of climate change impacts, losing their homes and livelihoods. The dual challenges of climate change and poverty necessitate urgent and integrated efforts to build resilience and reduce vulnerability.

A Call for a Resilient Recovery

While the road to recovery may seem daunting, there are glimmers of hope on the horizon. Governments, international organizations, and civil society have an opportunity to build back better, ensuring that the recovery from the pandemic is sustainable, inclusive, and resilient.

Investments in healthcare and social safety nets are crucial to ensure that vulnerable communities are better prepared to weather future crises. Rebuilding livelihoods through job creation, vocational training, and microfinance initiatives can empower individuals to lift themselves out of poverty.

Harnessing Technology and Innovation

The pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital technologies, showcasing their potential to bridge gaps in education, healthcare, and financial services. Leveraging technology and innovation can play a pivotal role in reaching marginalized populations and addressing systemic inequalities.

Mobile banking, telemedicine, and e-learning platforms can enhance access to essential services, particularly in remote areas. Moreover, investments in renewable energy and sustainable infrastructure can create jobs while combating climate change, fostering a greener and more inclusive economy.

Global Solidarity for Lasting Change

COVID-19 has underscored the interdependence of nations and the need for global solidarity in addressing poverty and other global challenges. It is essential for developed nations to support developing countries through financial aid, debt relief, and technology transfer to ensure an equitable recovery.

By collaborating on research, sharing best practices, and working towards common goals, the world can emerge from this crisis stronger and more prepared to confront future challenges. International cooperation is key to ensuring that the progress against poverty does not suffer further setbacks in the face of unforeseen adversities.

Conclusion

The impact of COVID-19 on poverty eradication has been nothing short of devastating. More than four years of hard-won progress has been erased, leaving millions trapped in the cycle of poverty once again. However, the pandemic has also shown the resilience of individuals, communities, and nations in the face of adversity.

As we navigate the uncertain terrain ahead, it is crucial for us to learn from the lessons of the pandemic and forge a path towards a more inclusive and sustainable future. By addressing the underlying issues of poverty, inequality, and climate change, we can build a world that is better equipped to withstand and overcome future challenges, ensuring that the progress against poverty is not only restored but accelerated. Together, we can rise from the ashes of this crisis and create a world where no one is left behind.

What's In It For Me? (WIIFM)

In this eye-opening blog article, you'll discover the harsh reality of the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on poverty eradication efforts. Learn about the setbacks, challenges, and potential pathways to recovery, while gaining insights into the global response and initiatives being taken to build a resilient future. Understand how this crisis affects you, your community, and the world at large, and find inspiration in the call for solidarity and global cooperation. Join us on this journey as we delve into the importance of collective action in ensuring progress against poverty is not only restored but accelerated, creating a world where no one is left behind.

Call to Action (CTA)

Let's stand together and take action against the devastating impact of COVID-19 on poverty eradication. Share this article with your friends, family, and social networks to spread awareness about the challenges faced by vulnerable communities. Engage in discussions, explore ways to support local and global initiatives, and volunteer your time or resources to help those in need. Together, we can make a difference and work towards creating a more equitable and sustainable world for everyone.

Blog Excerpt

The COVID-19 pandemic has dealt a severe blow to the progress made against poverty in recent years. The article sheds light on the unprecedented challenges faced by marginalized communities, the toll on global economies, and the alarming rise in extreme poverty. However, amidst the grim reality, glimmers of hope emerge as we explore potential pathways to recovery. From harnessing technology and innovation to fostering global solidarity, there are ways we can build back better and ensure a more inclusive and resilient future for all.

Meta description in 320 characters to appear in the Google Search Engine

Discover the devastating impact of COVID-19 on poverty eradication efforts. Uncover challenges, pathways to recovery, and calls for global solidarity in this enlightening blog article.

#COVID-19's impact on poverty eradication#Progress against poverty during COVID-19#Global poverty setbacks due to pandemic#Resilience in the face of poverty challenges#Building back better after COVID-19#Poverty eradication and the pandemic#COVID-19's toll on vulnerable communities#Challenges in poverty eradication post-COVID#Pathways to recover from COVID-19's impact#Addressing poverty in a pandemic-hit world#Rebuilding livelihoods after COVID-19#Role of technology in poverty eradication#COVID-19's lasting impact on the poor#Global cooperation for poverty alleviation#Women and poverty during the pandemic#Education setbacks amidst COVID-19#Climate change and poverty during COVID-19#Inequality and COVID-19's toll on poverty#Health crisis worsens poverty#Support for developing nations post-COVID#Opportunities for poverty eradication post-pandemic#Lessons from COVID-19 for poverty efforts#Social safety nets and poverty recovery#Microfinance impact during the pandemic#Sustainable development goals post-COVID#COVID-19's impact on vulnerable children#Gender disparities in pandemic poverty#Addressing the poverty pandemic nexus#A resilient future against poverty and COVID-19#Taking action against poverty post-COVID

0 notes

Text

Casting Nets Across Borders: Filipino Fishermen in 1950s Malaysia - A Story of Migration, Cultural Adaptation, and Labor Rights

The turquoise waters of the Sulu Sea, once a lifeline for coastal communities in the Philippines, became a stage for a new kind of exodus in the post-World War II era. The 1950s, a period of rebuilding and recovery for a nation scarred by conflict, also marked the burgeoning wave of Filipinos venturing overseas in search of better opportunities. Among them were fishermen, men accustomed to the rhythm of the tides and the bounty of the sea, who found themselves drawn to the promising fishing grounds of neighboring countries like Malaysia. This nascent stage of Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW) history, specifically focusing on fishermen in the 1950s, provides a glimpse into the complex interplay of economic necessity, cultural adaptation, and the ongoing struggle for fair labor practices.

The Philippines in the 1950s was a nation grappling with the aftermath of war. Infrastructure was devastated, unemployment was rampant, and poverty was widespread. For many Filipinos, particularly those in coastal communities who relied on fishing, the prospect of a stable income abroad became an irresistible pull. Malaysia, with its relatively developed fishing industry and proximity to the Philippines, emerged as a prime destination. While some fishermen might have ventured out independently, many were likely recruited through informal networks or nascent recruitment agencies, often with limited understanding of the working conditions that awaited them.

The journey to Malaysia was often fraught with uncertainty. Travel during this period was less accessible and more arduous than today. Fishermen would have likely travelled by boat, facing the perils of the open sea, or through a combination of land and sea routes, navigating bureaucratic hurdles and logistical challenges. Upon arrival in Malaysia, they encountered a different culture, language, and social environment. The predominantly Muslim Malay society differed significantly from the predominantly Catholic Philippines, requiring Filipino fishermen to adapt to new customs, religious practices, and social norms. This cultural adaptation, while challenging, became a defining characteristic of the OFW experience.

The work itself was demanding and often hazardous. Filipino fishermen in Malaysia likely worked long hours under harsh conditions, facing the unpredictable nature of the sea. They might have been employed on Malaysian fishing vessels or engaged in small-scale fishing operations, often with limited access to safety equipment and adequate healthcare. The lack of formal employment contracts and regulatory oversight left them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Stories of unpaid wages, inadequate food and living conditions, and physical mistreatment began to emerge, highlighting the precarious position of these early OFWs.

The seeds of advocacy for better working conditions were sown during this period. While formal organizations and legal frameworks were still developing, informal networks of Filipino fishermen began to provide support and share information. These networks played a crucial role in raising awareness about the challenges faced by OFWs and in laying the groundwork for future campaigns for labor rights. Back in the Philippines, families and communities began to recognize the contributions of OFWs to the national economy, prompting calls for government intervention to protect their welfare.

The 1950s also witnessed the beginning of formal diplomatic relations between the Philippines and Malaysia. This development paved the way for bilateral agreements and collaborations on issues related to labor migration. While these early agreements might not have fully addressed the specific needs of Filipino fishermen, they represented an important step towards establishing a framework for protecting the rights of OFWs. The growing awareness of the challenges faced by OFWs, both within the Philippines and in destination countries, contributed to the development of labor laws and regulations aimed at improving working conditions and preventing exploitation.

The story of Filipino fishermen in Malaysia during the 1950s serves as a microcosm of the broader OFW experience. It highlights the resilience and adaptability of Filipinos in the face of adversity, their willingness to sacrifice for their families and contribute to the national economy. It also underscores the ongoing struggle for fair labor practices and the importance of international cooperation in protecting the rights of migrant workers.

The legacy of these early OFWs continues to shape the landscape of labor migration today. The challenges they faced, the networks they built, and the advocacy they initiated laid the foundation for the robust OFW community that exists today. Organizations like OFWJobs.org provide vital resources and support to OFWs, connecting them with employment opportunities, legal assistance, and other essential services. These platforms represent a continuation of the efforts initiated by those early pioneers who sought a better life abroad while striving for dignity and fair treatment.

The evolution of OFW rights and protections has been a long and arduous journey. From the informal networks of support in the 1950s to the sophisticated legal frameworks and advocacy groups of today, the fight for better working conditions continues. The experiences of Filipino fishermen in Malaysia during the post-war era serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of this struggle and the need for continued vigilance in protecting the rights and welfare of all OFWs.

The narrative of Filipino fishermen in Malaysia is just one facet of the complex tapestry of OFW history. As the Philippines continued to grapple with economic challenges in the decades following the 1950s, the flow of OFWs to various destinations around the world intensified. Each wave of migration brought its own set of challenges and opportunities, contributing to the rich and multifaceted story of the OFW phenomenon. The lessons learned from the early experiences of fishermen in Malaysia, however, remain relevant and provide valuable insights into the ongoing quest for fair labor practices and the recognition of the invaluable contributions of OFWs to both their home country and the global economy.

The journey of the OFW, from the shores of the Philippines to the far corners of the world, is a testament to the human spirit of resilience, adaptability, and the pursuit of a better life. The struggles and triumphs of these individuals continue to shape the narrative of global migration, reminding us of the interconnectedness of our world and the shared responsibility to ensure fair and ethical treatment for all workers, regardless of their origin. The story of Filipino fishermen in 1950s Malaysia serves as a poignant reminder of the origins of this journey and the enduring legacy of those who paved the way for future generations of OFWs.

0 notes

Text

JUNE 1, 2021

Cities and towns are opening back up after their coronavirus-induced shutdowns. Job vacancies have surged to historic highs. Millions of Americans report that they are looking for work. Yet employers are struggling to fill available positions, leaving them with no option but to shorten their business’s hours of operation and pay overtime. Payroll growth has proved lackluster.

The familiar story about what’s happening goes like this: America is in the midst of a labor shortage. Businesses are unable to find enough workers, in no small part because of the country’s generous unemployment-insurance payments and repeated stimulus checks. This is a nightmare for growing companies, a trend that’s slowing the economic recovery, and a problem that policy must solve. Workers are “dampening what should be a stronger jobs market,” the Chamber of Commerce said, calling the situation a “very real threat” to the recovery. In response, 23 states and counting have slashed unemployment-insurance payments.

But what has rapidly become conventional wisdom is not necessarily wisdom at all. The labor shortage, so far as it exists, seems to have many complicated causes. Even if benefits are among them, policy makers should not rush in to help ensure a flood of low-wage workers for America’s businesses. As the pandemic abates and the economy strengthens, why not focus on creating good ones?

The evidence of a labor shortage comes both from hard numbers and from soft anecdotes. In terms of the hard numbers: Lots of Americans want work. Roughly 10 million Americans are looking for a job, and the unemployment rate is an uncomfortably high 6.1 percent. At the same time, lots of businesses want to hire. Employers report that they have 8.1 million positions open, the largest number in recorded history. Yet the number of Americans taking a job remains subdued: Payrolls grew by just 266,000 in April, when many economists expected a number as high as 2 million.

In terms of the softer stuff: More and more business owners are complaining, loudly, that they cannot find people to work. Restaurants are offering hiring bonuses to try to get potential workers in the door, Uber and Lyft are desperate for drivers, and Costco, McDonald’s, Sheetz, and Chipotle, along with many small businesses, have raised wages to attract employees.

The issue, many business executives and politicians claim, is that the country’s social-insurance and anti-poverty programs are providing more of a hammock than a safety net: Many workers are getting a $300-a-week bonus on top of their regular state UI payments, and are still flush from the rounds of stimulus checks sent out during the pandemic. Workers would rather stay home and collect the dole than go out and take a job, the argument goes. “Continuing these programs only worsens the workforce issues we are currently facing,” Missouri Governor Mike Parson said at a press conference, announcing a cut to the state’s UI payments. “It is time we ended these programs that have incentivized people to stay out of the workforce.”

But surveys of workers—and the simple observation of the strange and still-awful reality we find ourselves in—indicate many reasons why workers are hesitant or unable to take new gigs. The pandemic is abating, but it is not over. Many workers have preexisting medical conditions or a sick family member to worry about, meaning they cannot take a frontline, essential job. Millions of parents are still struggling with the closure of child-care centers and schools. More personal, less easily quantified impulses are at play too: After a year of immense personal and collective trauma, many people just want to take a beat before committing to a new job.

Wages are another pivotal factor. Workers used to making $21 an hour are unlikely to take jobs for $17 an hour—nor would doing so be good for the American economy. Workers used to making $17 an hour are unlikely to take a much more dangerous job for the same amount—nor would doing so be good for the American economy. And workers used to making $15 an hour, who now have a reasonable expectation that more $21-an-hour jobs will be available in a few weeks, are unlikely to take a job for $15 an hour—nor would doing so be good for the American economy.

Yet many employers are dragging their feet in raising wages to make their job offerings worth taking, given the economic climate and the risks of service work. Much of the “wage growth” evident in recent statistics is due to high-wage workers being much less likely to have lost their jobs than low-wage workers; once you account for that fact, wages have not risen much at all. This is part of what accounts for the “labor shortage.” The issue isn’t workers. It’s employers.

The country’s generous UI is likely playing a role too. In a recent survey by ZipRecruiter, job seekers reported feeling far less financial pressure to take the first job they were offered, likely because UI and stimulus checks buoyed family finances. But a large body of research has shown that UI has a more moderate effect on job-acceptance rates than one might think, because it offers only the lowest-paid workers more incentive to say no.

Moreover, UI helping drive wages up by giving workers the option of saying no to a bad job is not a bad thing. Ample UI improves what is sometimes called “job match,” because it gives job seekers the ability to wait for the right position to come along. It also has disproportionate benefits for Black and Latino workers, who have borne a disproportionate burden of both the health crisis and the economic crisis of the past year.

A more philosophical point needs to be made here, too: The job of the government is not to ensure a supply of workers at whatever wage rates businesses set. And workers’ having the power to say no is not a policy problem that the government needs to solve. For decades, though, Washington and America’s statehouses have helped rig the country’s policy infrastructure in employers’ favor.

The federal government has set the country’s wage floor below its poverty line, for instance, and has not increased the minimum wage to account for improvements in productivity and output over time. The current federal minimum is just $7.25 an hour, compared with roughly $10 an hour in Ireland and Canada, $11 in the Netherlands, $12 in France and Germany, and $12.50 in Australia and Luxembourg. Indeed, the United States has the lowest minimum wage compared with typical or average wages of any country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. That helps explain why the United States has the highest share of low-wage work among the OECD countries. Fully one-quarter of American workers earn less than two-thirds of the median wage, compared with just 5 percent in Belgium and 12 percent in Japan.

The government has also proved complicit in the collapse of unionization and collective bargaining, making it easy for businesses to beat back organizing efforts and difficult for workers to band together to demand raises, benefits, and safe working conditions. The country has half, one-fifth, one-ninth of the collective-bargaining coverage of many of our peer countries. This has increased inequality in America, holding down wages while bolstering corporate profits.

At the same time, the government has declined to make companies compete against one another—for customers or for workers. Corporate concentration has increased, and any number of industries are dominated by just a handful of giant players. This pushes up profits and decimates wages, particularly in areas with fewer employers.

In recent decades, the government has also decided to allow the unfettered proliferation of Uber-type jobs, sacrificing the needs of low-wage workers in order to satisfy the preferences of wealthy, urban consumers and calling it all “innovation.” The central “innovation” of the gig economy is to call employees “contractors,” to avoid giving them benefits and a stable salary.

Even the American safety net exists not to eliminate poverty so much as to use poverty as a cudgel to force individuals into low-wage work. The earned-income tax credit goes only to people with earned income; food stamps and welfare benefits require a job-search effort. Over time, UI has become in some ways more and more like welfare; many states have made benefits shorter in term and stingier in size.

The government has long encouraged low-wage jobs and forced people into them. This is what we are seeing when governors rush to slash UI at the first sign of a real recovery and when policy makers describe workers’ demands as a “drag” on the economy. Uncle Sam is acting in the interests of low-wage employers, not the economy as a whole.

Perhaps the status quo is changing. The Biden administration has pushed a new New Deal designed to end poverty and provide greater economic security to the 99 percent. It is arguing that bolstered, extended UI should be kept in place for the benefit of American families. It is also promising to be the most pro-union government in decades. Part of this push must be giving workers the power to say no to employers—and putting employers in the uncomfortable position of having to compete for workers.

Maybe a labor shortage is a good thing.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The WHO Calls for Radical Change in Global Mental Health

On June 10, the World Health Organization released a 300-page document titled “Guidance on Community Mental Health Services: Promoting Person-Centred and Rights-Based Approaches.” The document and its authors call for wholesale change and a revolution in mental health:

Although some countries have taken critical steps towards closing psychiatric and social care institutions, simply moving mental health services out of these settings has not automatically led to dramatic improvements in care. The predominant focus of care in many contexts continues to be on diagnosis, medication and symptom reduction.

Critical social determinants that impact on people’s mental health such as violence, discrimination, poverty, exclusion, isolation, job insecurity or unemployment, lack of access to housing, social safety nets, and health services, are often overlooked or excluded from mental health concepts and practice. This leads to an over-diagnosis of human distress and over-reliance on psychotropic drugs to the detriment of psychosocial interventions – a phenomenon which has been well documented, particularly in high-income countries. It also creates a situation where a person’s mental health is predominantly addressed within health systems, without sufficient interface with the necessary social services and structures to address the above mentioned determinants.

The biomedical model of mental health is an “illness” model, and thus the notion of recovery is associated with a reduction of symptoms. The individual is in recovery from a disease, and psychiatric drugs are understood to be a first-line treatment to help people recover in this way.

The WHO guidance doesn’t spend much energy criticizing the biomedical model of care, but there is an implicit message in all of its pages: that model of care has failed, and what is needed now is a fundamental rethinking of what is possible. The authors write:

A fundamental shift within the mental health field is required, in order to end this current situation. This means rethinking policies, laws, systems, services and practices across the different sectors which negatively affect people with mental health conditions and psychosocial disabilities, ensuring that human rights underpin all actions in the field of mental health. In the mental health service context specifically, this means a move towards more balanced, person-centered, holistic, and recovery-oriented practices that consider people in the context of their whole lives, respecting their will and preferences in treatment, implementing alternatives to coercion, and promoting people’s right to participation and community inclusion.

.

#mental health services#recovery model#human rights#social justice#social model#biomedical model#diagnostic model#psychiatry#psychiatry critical#anti psychiatry#my day job#madness

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help Lisa Recover from the Pandemic Fallout

In 2020, the coronavirus made its way across the world. There were lockdowns to control it’s spread, mask mandates and social distancing sweeping across the globe and everything from corporate offices and small businesses, to schools, libraries and universities shut down with only essential workers still required to report to work in the pandemic. I was one of them still reporting for work at the office while others were instructed to work from home.

As workers, if we became asymptomatic and wanted to get checked out at a medical facility. Back then, we were instructed at the Emergency Room that we were not going to get tested for COVID due to the limited supply of test kits available and hospital directives back then was to test only first responders and the critical ill. Directions for all other citizens was to self-quarantine for 14 days but even if we had COVID, we wouldn’t have known as we were turned away for testing. Workers had no labor protections or safety nets in the pandemic as this was a new strain of virus that the government was unprepared for.

And for that reason, any worker that fell within the CISA’s Critical Infrastructure were still required to report to work in the pandemic https://www.cisa.gov/identifying-critical-infrastructure-during-covid-19

Other workers that were not listed on the list, followed governor mandates in states across the US.

The downside was that when I was instructed to self-quarantine. Within days of that directive by hospital personnel, my employer terminated my contract while in quarantine and I was relieved of my duties which was fast and swift. The termination was sudden, but thankfully I had my savings to turn to while I continued to seek employment but, in the beginning, it was difficult as States were still in a lockdown and job opportunities were scarce due to the pandemic and hiring freezes. Eventually, as days turned to weeks and weeks turned to months, and application after application was denied for anything from not being selected for a position or position closed or a hiring freeze or overqualified, etc. Securing re-employability became a daunting task as my savings depleted pushing me into poverty and lack of housing.

Due to the lack of financial stability, I was also affected by the COVID-19 housing crisis and forced to live out of my car for a while which was drastic and extreme being shower facilities were shut down. This was extremely difficult as access to all necessities like showers were also cut off. No public recreational center or gyms were open at the time due to phases of recovery and shutdowns of these facilities.

My health started regressing quickly while I was living in my car due to lack of shelters availability and lack of resources in the state and their own issues of depletion of their funding also, leaving the vulnerable without available protections or resources available. I have temporary shelter now, but it is just that…. (temporary) and this fundraiser has been started to get some assistance that agencies could not provide with lack of resources and funding and waiting lists. Urgency is needed that a waiting list with no guarantees can provide as we are now going on close to a year since COVID19 initially made its way to the United States from overseas wreaking havoc around the globe and humanity.

These stressors have resulted in neglect of my pre-existing medical conditions and developing new ones such as Type II Diabetes which I never had before the pandemic and loss of housing, I also am required to administered insulin daily of pre-filled pens (#2)

I developed decreased lung volume in my lungs and my right lung nearing atelectasis which probably was exacerbated from not being able to be on my respiratory device daily in the housing crisis.

My blood pressure was unstable and kept spiking with these stressors, putting me at risk of a stroke after previously having a TIA, still encountering seizures at times and speech impairment that luckily I would regain and not be a permanent impairment.

These times have been tough but still have to count my blessings, Every little donation helps and is crucial at this point to regain housing to continue my respiratory treatments as I continue my journey of a safe environment and job security in my continuous journey of a stable housing. I hope to find a job soon and for my life to return to normalcy, but in the meantime, I require your help to stay afloat.

Thank you kindly for taking the time to read my story and hear my plight. The funds will be used for basic essentials, housing and moving near to family for health reasons and emotional support after enduring devastating losses. Homelessness is never a choice for working Americans whose plight took a change of course that no one wanted to endure. COVID19 has taught us many lessons on different levels.

https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-lisa-recover-from-the-pandemic-fallout

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

3 October 2021: King Abdullah II received World Bank Group President David Malpass at Basman Palace.

He expressed appreciation of the longstanding partnership with the World Bank Group, commending the group’s prompt response to the priorities that Jordan raised in July, including working with the government on its 2022-2023 plan, which seeks to enhance the economy’s resilience and recovery. His Majesty said Jordan counts on the bank’s support in a number of priority sectors, including energy, tourism, transportation, job creation, and enhancing the social safety net, stressing the importance of bolstering cooperation to promote the business and investment environment, and supporting public-private partnerships through the bank’s International Finance Corporation. (Source: Petra)

For his part, Malpass commended Jordan’s efforts in addressing poverty, boosting the business environment, and enhancing the growth of the private sector, which helps in creating job opportunities. In addition, the World Bank Group president expressed appreciation of Jordan’s support for refugees, including providing them with education, job opportunities, and health services, stressing the importance of the bank’s partnership with Jordan. The meeting also covered possible World Bank Group support for Jordan’s efforts in enhancing regional economic integration, and energy connectivity projects in the region.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed tragic shortcomings in the American public health system, but it also posed a major challenge to our social safety net programs, from Medicare and Medicaid to Unemployment Insurance to Social Security, and more.

A new report by a working group that we co-chaired at the National Academy of Social Insurance indicates that the safety net was surprisingly resilient in some areas, but that the pandemic also reinforced existing inequalities and revealed system shortcomings. To be ready for the next crisis, America should act now to streamline program administration, increase responsiveness, and reduce disparities.

Despite the closing of many government offices, dedicated workers ensured that programs remained operational, albeit with disruptions and delays. Social Security and Unemployment Insurance benefits continued to be paid, and Medicare and Medicaid continued to finance health care.

Surprisingly, COVID did only limited financial damage to Social Security and Medicare. Because the economic recovery was unexpectedly fast, the dip in payroll taxes to fund these programs was briefer and shallower—and program spending was lower—than projected. COVID reinforced the downward trend in claims for Social Security Disability Insurance benefits, as office closures hindered new applications. Medicare spending also fell, as patients delayed non-urgent care. Despite the spike in COVID-related admissions, overall hospital admissions dropped 30%.

Beyond the existing safety net programs, Congress took further actions to mitigate the financial and health calamity. It increased and extended unemployment benefits and provided sizable lump-sum benefits to most Americans. Together with the Child Tax Credit (now expired) and increases in Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program benefits, these changes helped cut poverty in 2021 by 15% overall and by 46% for children. Changes in Workers’ Compensation provided income assistance and health insurance coverage. Eviction moratoriums mitigated the risk of homelessness for many. Fears that such generous assistance would undermine workers’ incentive to seek new jobs proved largely unfounded, as employment rebounded faster than anticipated.

Congress also extended health care coverage, increasing the share of Medicaid costs borne by the federal government for states that maintained enrollment and liberalizing refundable tax credits for health insurance exchange plans. Between these provisions and the faster-than-expected rebounding of employment-based health insurance, the proportion of non-elderly Americans without insurance in 2021 fell to 10.3%, a historic low. Because Medicare and Medicaid typically pay providers less than private insurers, Congress shored up hospital finances by creating a fund to offset the influx of COVID patients covered by these programs (though the fund was not particularly well targeted to struggling hospitals).

Overall, our social insurance programs did what they were supposed to—though, without congressionally enacted changes, there would have been much greater financial distress. Although the targeting of benefits to those most in need was imperfect, enough cash and in-kind assistance went out to sustain consumer demand, supporting a U.S. economic recovery that was faster than that of many other countries.

Despite these successes, serious failures meant that millions of people suffered much more dire financial as well as health consequences than they might have. The failures of our public health system—from lack of sophisticated monitoring, data, and infrastructure supporting rapid deployment of resources to shortages of supplies addressing foreseeable needs—are well documented, and were major contributors to the shocking 1.3 million deaths due to COVID in the U.S. The death rate of Medicare beneficiaries in nursing homes was thirteen times that of Medicare beneficiaries living elsewhere, and disproportionately higher for African Americans and Hispanics than for whites.

Our social insurance infrastructure was also woefully lacking—particularly the management of unemployment benefits. Archaic computer systems, lack of data and overworked staffs resulted in delays in the delivery of aid to the tsunami of new applicants. Confusion about eligibility rules and lack of information (such as for those not filing tax claims) led to many not receiving benefits for which they were eligible. Insufficient data also meant that aid could not be targeted based on past earnings or economic hardship. Thus, while congressional actions helped mitigate financial hardship, they were often poorly timed and poorly targeted.

The pandemic illustrated once again that those who are least well protected against adverse events in normal times suffer the most during emergencies. Those from low-income or underserved areas suffered disproportionately, as did those from racial and ethnic minority groups. There were not only unconscionable disparities in mortality and adverse health outcomes, but also in access to financial support.

The National Academy of Social Insurance report not only documents the performance of the system under COVID but presents practical and practicable ways to prepare for future health (or economic, environmental or geopolitical) emergencies.

Many of the crucial steps undertaken by Congress could be implemented in a more streamlined and effective way if automatic triggers were enacted now, such as additional Medicaid financing for states that maintain enrollment during emergencies or extended unemployment insurance benefits. Other temporary measures could be made permanent, such as changing regulations about telemedicine or scope-of-practice restrictions.

All of these options could be better supported by modernized infrastructure to allow efficient program administration and the collection of data to allow better benefit targeting. The digital divide further amplified health and access disparities during shut-downs. Adequate internet communication is an essential element of both health and safety net systems.

Our social insurance programs provide a vital safety net at all times but never more crucially than during national emergencies. COVID revealed how very important these programs are to health and economic survival—and also ways that we can shore them up before the next emergency arrives. It behooves us to do so.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Controversy Continues Over SF Restaurant Serving $200 Meals in Private Domes

Last month, California governor Gavin Newsom announced the mandatory closure (or re-closure) of all indoor restaurant dining rooms throughout the state. After investigating its options, Michelin-starred sushi restaurant Hashiri announced that it had purchased three miniature geodesic domes so it could provide a "unique outdoor multi-course dining experience." At the time, the domes seemed like a novel means of providing increased privacy safety for diners during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A few days ago, after a brief hiatus, Hashiri was allowed to start seating customers in its three outdoor geodesic domes again after the staff cut the plastic sides off to bring them into compliance with current public health requirements. Slicing several feet of soft PVC from the Garden Igloos seems to be a satisfactory resolution—at least for now—after two straight weeks of controversy that started when they were assembled on a San Francisco sidewalk.

Hashiri general manager Kenichiro Matsuura told the San Francisco Chronicle that he had previously attempted outdoor dining (pre-plastic bubbles) but it hadn't worked out, due to the restaurant's location in the Mid-Market section of the city. "We wanted to continue offering the fine-dining experience—and safety and peace,” Matsuura said. (The restaurant also offers a swanky to-go menu, including a $500 Ultimate Trifecta Bento box and a $160 takeaway Wagyu Sukiyaki kit, but it is best known for its five-course Kaiseki and Omakase tasting menu.) “Mint Plaza is a phenomenal space, it’s just sometimes the crowd is not too favorable,” he said. In an interview with ABC7, he again emphasized that "it's not the safest neighborhood."

The entire Bay Area has an estimated 35,000 people who are unsheltered or experiencing homelessness and, at the beginning of the pandemic, there were more than 8,000 unhoused individuals in San Francisco alone. In mid-March, when the city issued its first stay-at-home order, homeless residents were encouraged to "find shelter and government agencies to provide it” but that was easier to type than it was to do. The Guardian reports that shelters stopped taking new residents due to concerns of overcrowding or inadequate social distancing, and more than 1,000 people put their names on a futile-sounding waitlist to get a bed.

In April, the city's Board of Supervisors unanimously passed emergency legislation directing the city to secure more than 8,000 hotel rooms to accommodate all of the unhoused people in the city, but the order was denied by Mayor London Breed. It eventually acquired 2,733 hotel rooms for vulnerable individuals but, as of this writing, only 1,935 of them are actually occupied. As a result of the pair of public health crises that the city is enduring—the pandemic and widespread homelessness—the number of unhoused people has increased, as have the number of tents and other makeshift structures that comprise a homeless encampment near Hashiri.

"This is a difficult and upsetting issue," Laurie Thomas, the Executive Director of the Golden Gate Restaurant Association, told VICE in an email. "In San Francisco there are areas in the city where there are real concerns about negative street behavior and cleanliness and how that affects both workers and customers of restaurants relying on outside dining [...] Our restaurants have a strong desire to provide a safe and welcoming outdoor dining experience, especially without the ability to open for indoor dining, and this is so critical to their ability to stay in business and keep staff employed."

It's easy to sympathize with just about everyone in this scenario. The pandemic has caused an ever-increasing number of challenges for restaurant owners, who are doing whatever it takes to keep their doors open for another day, while the essential workers who prep to-go orders and serve outdoor customers are doing so at great risk to their own health and safety. But still: the optics of serving a $200-per-person tasting menu to customers sitting in plastic bubbles a few hundred yards from people who are struggling for basic human necessities...well, they're not great.

"I think what really gets people going about the dome is that it’s a perfect symbol of the complete inadequacy of our social safety net: In a queer reversal, the dome is a shield against, not for, the ones who need sheltering the most," the Chronicle's restaurant critic Soleil Ho wrote. "An unhoused person’s tent is erected in a desire for opaqueness and privacy, a space of one’s own, whereas the fine dining dome invites the onlooker’s gaze as a bombastic spectacle [...] for the housed, being seen eating on the street or in a park is a premium experience, especially now."

Last week, the city's Public Health Department paid Hashiri a surprise visit, and ordered them to remove the domes over concerns that they "may not allow for adequate air flow." According to current regulations, outdoor dining enclosures are required to be open on the sides; the soft structures each have two windows and a door that can be opened, but those features were deemed insufficient.

Matsuura said that he has received hate mail about the domes and he has been accused of making discriminatory comments about the city's most desperate residents, so he believes that someone reported him to the city (though, perhaps the Health Department just saw some of the nationwide media coverage of Hashiri's sidewalk igloos). Regardless, he still says that the domes are there to keep his customers safe… from interacting with the people living on those same streets. "There are people who come by and spit, yell, stick their hands in people’s food, discharging fecal matter right by where people are trying to eat,” he said. “It’s really sad, and it’s really hard for us to operate around that.”

The criticism that Hashiri has faced is similar to what the organizers of a pop-up restaurant in Toronto encountered when they set up their own heated glass domes last year. The Dinner with a View experience, complete with a three-course gourmet meal prepped by a Top Chef winner, was assembled under the Gardiner Expressway, just over a mile from the site of a homeless encampment that had been cleared out by the city.

Advocates for the unhoused said that the meal and its location just further emphasized the ever-increasing gap between the Haves and the Have Nots. More than 300 demonstrators showed up to protest outside the event, and the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP) served a free 'counter-meal' that it called Dinner with a View of the Rich.

"On the one hand you have homeless people whose tents were demolished and who were evicted with nowhere else to go," OCAP wrote. "On the other hand you have people with sufficient disposable income to splurge over $550 on a single meal and who’re facing the possibility of their luxurious dining spectacle being tainted [...] Do they deserve to be mocked for their obliviousness to the suffering around them? Absolutely."

Back in San Francisco, Hashiri is not the only Mid-Market restaurant to express concern about the safety of its patrons, or about the city's ineffective attempts at addressing the social and economic conditions that have contributed to the homelessness crisis. Last month, a group of residents and businesses in the neighborhood sued the city for negligence, alleging that homeless encampments, criminal activity, and unsanitary conditions combined to make Mid-Market a dangerous area.

"The City has created and perpetuated these conditions through its pattern and practice of tacitly treating Mid-Market as a ‘containment zone’ that bears the brunt of San Francisco’s homelessness issues, and its failure to take action to address these issues," the lawsuit said. Two of the restaurants that are among the plaintiffs, Montesacro Pinseria and Souvla, said that if the situation doesn't improve, they could be forced to move to a new neighborhood, or to close their doors for good.

"We are deeply concerned that property owners have taken to suing the city to 'remove tents' without anywhere for [those experiencing homelessness] to go. Worse, these lawsuits would have the courts decide the fate of people who have no seat at the table where 'justice' is being served," Jennifer Friedenbach, the executive director of San Francisco's Coalition on Homelessness, told VICE.

"These situations can be resolved by working collaboratively with the unhoused person to address the issues, while pressing the city, state and federal government to ensure there are dignified housing options available. If the restaurant owner can afford to sue, they can afford to hire someone to advocate successfully for solutions."

Laurie Thomas is also working on behalf of restaurants, sharing their concerns and working toward positive changes and respectful solutions for all involved. Last week, she was among the hospitality and small business leaders who sent a letter to Mayor London Breed, the President of the Board of Supervisors, and the co-chairs of the City's Economic Recovery Task Force.

"We are writing today because we are gravely concerned about the condition of our streets. We are devastated to see so many unsheltered neighbors struggling each day in unfathomable and treacherous conditions," their letter read. "These conditions will prohibit businesses of all sizes from reopening. More companies will leave San Francisco for safer and cleaner places to operate [...] Additionally, with outdoor dining and shopping options being the primary avenues for businesses to survive, the intersection between the unfortunate conditions on our streets and this new heavy reliance on public spaces for commerce will result in disastrous outcomes."

The letter also made a number of recommendations that "should be prioritized" by city officials, including additional housing options, making mental health and substance abuse resources available to those experiencing homelessness, and establishing a 24-hour crisis response team that can respond to "urgent mental health and/or drug induced episodes."

Meanwhile at Hashiri, the DIY-ed, now open-sided domes are back out on the sidewalk. "Signed, sealed and delivered," the restaurant wrote on Facebook. "With small modifications we are back in business."

via VICE US - Munchies VICE US - Munchies via Mom's Kitchen Recipe Network Mom's Kitchen Recipe Network

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Faith can be secular. I’ve recently learned personally how critical faith and trust are to us. Segue to politics from healthcare.

Some of you are aware that our son has had a liver transplant. What you may not know, because frankly I don’t remember what I’ve posted recently, is that the transplanted liver failed. He then received almost immediately a second liver, which was transplanted. The procedure went well initially, but then horribly wrong. He was in an uncontrolled bleeding situation, and almost died. But he didn’t. We learned that the cautious and meticulous actions taken by his healthcare providers has worked, and the bleeding was brought under control after three days.

Today (nine days after the nightmare began), he opened his eyes and communicated with us, through nods and shakes of his head. I was speechless, but I managed an inane, “Tom, I’m here! Hi!” I was in awe. He is now entering into a “normal” transplant recovery and monitoring process. It will be arduous, but not as terrifying or threatening as what he has gone through.

What does this have to do with faith and trust? When the first liver failed, it felt like we were on the precipice of a cliff, looking down into a deep, dark canyon with steep walls. We had no idea what would happen or what to do. We were terrified. We could have been angry, but we weren’t. We were scared, and felt helpless and immobilized. Then, that evening, a second liver was located. We were relieved and grateful, and again thought of the fellow human being who was giving life to our son, and her or his family.

About 24 hours later, when he was in uncontrolled bleeding during the procedure and the lead surgeon told us his prognosis was extremely poor, we were back on that cliff again, but this time the canyon was darker and steeper and had no bottom. The feelings of helplessness, fear and terror were more intense than they had been the day before, and were accompanied by a sense of loss.

In both of these situations, the only thing that kept me going and prevented me from going into uncontrolled despair was faith. I knew that there is a mostly-hidden, but effective organ transplant system out there, functional and mostly successful, and based upon a combination of the private healthcare sector and government partnership. I had faith that the people running that system, or working with or within it, were working hard on locating a second liver. They had to be. I trusted the doctor and the team who told us they were going to find a new liver. Faith in a system and trust in people pulled me through. Then when the death angels were knocking on the door, I watched seven to nine professionals in our son’s room in the ICU, feverishly doing their jobs, running and rushing here and there, poking and prodding, reacting quickly in a controlled chaos, adjusting numbers on digital devices, hearing beeps and whistles and bangs and whoosh noises. At that very intense moment, I had faith in the healthcare system and trust in those women and men working so hard to save our son. And they did, because about 4 or 5 hours after the nightmare starting, the blood loss was reversing.

Looking back now, I realized my faith in social and healthcare systems and their webs and weaved threads and rules and regulations and brilliant people was all I had left at those moments when our son needed a new liver and then later when he was dying. Faith and trust. Now I understand a lot more what faith in the religious context means, and how critically important faith and trust generally are to each of us so that we can live in a complicated and sometimes baffling world.

What does this have to do with “segue to politics?” The politicians in the republican party have for years, since reagan, strived to weaken and then destroy our systems that are our safety nets and sources of comfort and assurance, and have created, intentionally and maliciously, doubts in each of our heads about their need and efficacy, all at the altar of Ayn Rand or whomever else is emerging at the moment as the latest savior of that “old way of life” and rugged individualism. Then came trump and his people, who have accelerated that destruction, and deepened and broadened the destructive impact so that we have reached the point where we doubt if our vote physically counts, because the system is hacked or rigged, or if whom we vote for cares what we think, or if those politicians will redefine disability or poverty to harm millions more, or will change our regulations to tolerate the expulsion of more toxic air or crap into our water, thus making us ill, or whether the Department of Veteran Affairs will fail our veterans or if we will die because our healthcare insurance programs will only cover hangnails, and then only those that weren’t there last week, and so on. We don’t trust much anymore, and are losing faith or have lost faith that the systems embedded within our government to protect our health, environment, safety, savings, children, elderly parents, our kids’ education, and so on will help us, or even acknowledge our existence.

These people must go, and whomever follows has to work really hard to restore whatever can be restored so we can once again have faith in what surrounds us and trust in the people embedded in those systems to help us.

Faith and trust have become my mantra. I now get it, after years of struggling to understand.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peak uncertainty: This is what covid might do to our politics

By Chaminda Jayanetti

Just because something should happen, doesn't mean it will.

Many articles speculating on how Britain will look different after coronavirus mistake what the writer thinks should happen with what probably will, trusting in the logic of the moment when politics often obeys anything but.

Others focus on the party political fallout, which is the most unpredictable aspect of all. Coronavirus may determine the next election - or it may play no role in it at all.

But to really get an idea of how Britain could look on the other side, we need to get away from the big picture discussion and dig deep into policy areas.

Who cares?

The centrality of the NHS is now guaranteed no matter who is in charge. The Tories had already pledged increased funding, and the need for spare capacity in the event of pandemics may force a rethink of service redesigns and efficiency measures that aimed to minimise 'waste'.

Bigger questions surround the adult care system. No-one can now ignore the funding cuts and staff shortages that have left the care sector so depleted. If elderly and disabled people find themselves dying untreated in care homes in large numbers, this might - and should - become a point of national shame over the coming weeks.

The Tories' direction of travel is towards a social insurance system, whereby people pay in to a fund during their working lives that gives them access to care provision when they need it. But those who are retired or have lifelong care needs won't be able to pay into an insurance scheme before receiving care. These immediate care needs will need direct public funding, not long-term insurance.

Labour under Jeremy Corbyn took a different tack: universal free personal care for the over-65s, with an ambition to extend this to all working age adults. This is simpler and more inclusive than our current means tested mess, but it doesn't come cheap: Labour's manifesto estimated the cost as £11bn a year by 2023/24.

Keir Starmer will be under pressure from some to stick with their existing policy, and from others to engage with social insurance proposals. Keeping Labour MPs united behind whatever strategy he adopts won't be easy.

But it's plausible the Tories will also be pulled in another direction - towards voluntarism. The party's social and fiscal conservatives - uneasy bedfellows in recent years - could use the increased community cooperation seen amid the pandemic as evidence that volunteers and family members can take on more of the care burden, while still improving pay and conditions for care staff.

Expect to see rhetoric that the pandemic has 'unleashed' Britain's 'community spirit', which should be 'channelled' after the crisis by relying on family and neighbours to 'look in' on people in need - the soft-soap version of women doing unpaid care work in lieu of public services. The current trend in care provision is towards making use of what 'assets' people already have, including friends and family - an approach that can be used for good or ill. The temptation for the government to lean on unpaid volunteers instead of the taxpayer is not hard to imagine.

The care system was the biggest public service challenge facing the government before coronavirus. Now that's been magnified tenfold. It could become one of the big battlegrounds of post-pandemic politics, between competing visions of society based on universalism, managed markets, and voluntarism.

Bob Crow was right

Before his death in 2014, Bob Crow was one of the most demonised figures in Britain. His readiness to threaten to shut down rail networks as head of the RMT union made him a bête noire for commuters, causing considerable disruption.

Crow was a rarity in post-Thatcher Britain - a union leader who was ready to use strike action as a sword, not just a shield. Whereas most unions only went on strike in defence of existing jobs, pay and conditions, Crow levered the criticality of the role of his members to transform their economic position.

He was accused of holding passengers and politicians to ransom, but his argument was a simple one: the disruption caused by his members going on strike showed how important their role was, and they should be paid more - much more - to reflect this.