#Sharmila Tagore Movies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I love when bollywood heroines are like

#bollywood#sharmila tagore#meena kumari#vajantimala#aishwarya rai#retro movies#retro bollywood#desiblr#desi tag#desi tumblr

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

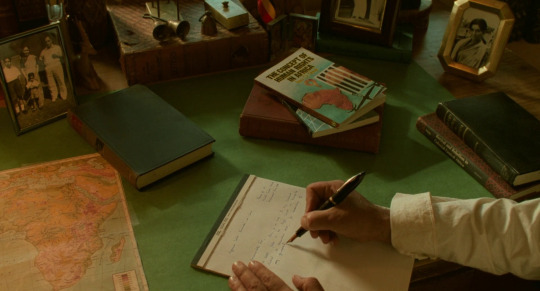

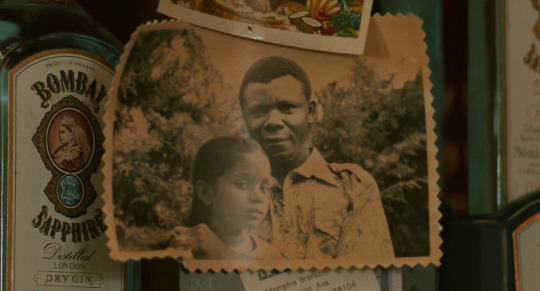

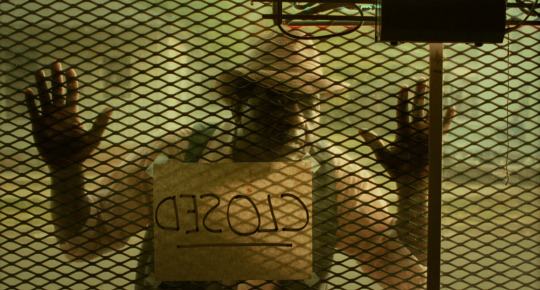

Mississippi Masala (1991)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mississippi Masala (1991) | dir. Mira Nair

#mississippi masala#mira nair#roshan seth#sharmila tagore#denzel washington#sarita choudhury#films#movies#cinematography#scenery#screencaps

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devi / The Goddess (1960) | dir. Satyajit Ray

#devi#devi 1960#the goddess#the goddess 1960#satyajit ray#sharmila tagore#indian cinema#bengali cinema#cinema#movies#films#world cinema#classic cinema#1960s#cinematography#south asian cinema#asian cinema#indian movies#bengali movies#indian films#bengali films#cinephile#film scenes#movie scenes#parallel cinema

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mississippi Masala (1991)

Two of the Hottest People You’ve Ever Seen fall in love—despite the protestations of their families and the cultural differences that divide them—against the backdrop of the dreary Deep South in Mira Nari’s sexy, undeniable romantic dramedy.

Director: Mira Nair

Cinematographer: Edward Lachman

Production Designer: Mitch Epstein

Costume Designers: Ellen Lutter and Susan Lyall

Starring: Sarita Choudhury, Denzel Washington, Roshan Seth, Sharmila Tagore, Charles S. Dutton, Joe Seneca, Ranjit Chowdhry, Mohan Gokhale, Natalie Oliver-Atherton, Sahira Nair, and Konga Mbadu.

#mississippi masala#1991#mira nair#sarita choudhury#denzel washington#sharmila tagore#natalie oliver atherton#romantic comedy#costume design#feminist film#female directed films#90s movies#independent film#mississippi#cult classic#criterion collection#indian american#black history month#steamy#female directors#woman director#directed by women#1990s#90s fashion#production design#cult film#90s cinema#feminist cinema#romantic movies#90s aesthetic

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy 80th, Sharmila Tagore.

Satyajit Ray’s The World of Apu (1959).

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

#movies#polls#apur sansar#apur sansar 1959#apur sansar movie#50s movies#satyajit ray#soumitra chatterjee#sharmila tagore#alok chakravarty#swapan mukherjee#dhiresh majumdar#apu trilogy#the apu trilogy#have you seen this movie poll

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

[অপুর চিঠি] নিজের যত্ন নিন। আমি ভালো আছি, কিন্তু আমার হৃদয় অসুস্থ। তুমি এলে সেরে যাবে। যদি তুমি না করো - আমি আর কখনো তোমার সাথে কথা বলবো না...

#being bengali#bengali movie#apur sansar#soumitra chatterjee#sharmila tagore#desiblr#desi tumblr#me#desi teen#desi academia#love#quotations#spilled ink#txt#intimacy#thoughts#black and white#movies

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

@callonpeevesie @medusasprotegedaughter @beingdevipdf @shaonsim @mitraavarunaa hehe check it out.

#original post#aesthetic#moodboard#desi tag#satyajit ray#apur sansar#soumitra saha#sharmila tagore#bengali movie#old movies#vintage movies

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes desi OTT is a gift that keeps on giving. first we got THE madhuri dixit playing a lesbian character, and now we have THE sharmila tagore playing a bisexual character? we love to see it.

#maja ma#gulmohar#madhuri dixit#sharmila tagore#both the movies were a little meh but women??? yes.#vi.txt#Bollywood#Desi

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devi (1960, India)

One year following his stunning Apur Sansar (The World of Apu) (1959), director Satyajit Ray reunited actors Sharmila Tagore and Soumitra Chatterjee. By this point, Ray was no longer the studious yet inexperienced hand that shepherded the Apu trilogy to its conclusion. But his lead actors were still only starring in their second-ever film. Bengali cinema (Tollywood, based in West Bengal) had a proud history before Ray’s Apu trilogy (1955-1959), but now had caught the attention of audiences beyond India – disproportionately so, as Bollywood (Hindi cinema, based in Mumbai) has always been the largest part of the nation’s film industry. Unlike some of the most popular Tollywood and Bollywood films of the time (and now), Ray never showed interest in romantic-musical escapism and instead dared to make films challenging India’s caste system, sexism, and religious fanaticism.

In his first work addressing religious fanaticism (and arguably his first truly political film) comes Devi, also known by its English-language title as The Goddess. Unlike 1965’s Mahapurush (The Holy Man), which also covers the same topic, Devi is thoroughly a drama, with no hint of comedy or satire. The film’s somber tone did not sit well with general Indian audiences used to lighter fare, and its willingness to criticize the extremes of Hindu religiosity saw the film’s harshest critics deem it (and Ray) as anti-Hindu. If released today, Devi almost certainly would receive a similar, if not more intense, backlash from groups and individuals in India criticizing it out of bad faith.

Somewhere in a rural town in nineteenth century Bengal, younger brother Umaprasad (Soumitra Chatterjee) is ready to depart for Kolkata for university and to study English. Umaprasad’s family is wealthy, with numerous servants tending to their multistory mansion. All is well in their richly-furnished, well-kempt home as he leaves his teenage* wife Dayamayee‡ (Sharmila Tagore) to take of his aging father/her father-in-law Kalikinkar Choudhuri (Chhabi Biswas). One night, Kalinikar awakens from a marvelous dream. An adherent of the goddess Kali, his visions lead him to believe that his daughter-in-law is Kali’s physical incarnation. Upon awakening, he rushes to Dayamayee and falls to his feet in worship. Dayamayee’s life as Umaprasad’s wife has ended. Against her will, she becomes an object of religious devotion as word spreads of Kalikinkar’s dream and a supposed miracle shortly thereafter.

Devi also stars Purnendu Mukherjee as Umaprasad’s brother, Taraprasad; Karuna Banerjee as Harasundari, Taraprasad’s wife; and Arpan Chowdhury as Taraprasad and Harasundari’s son (Dayamayee’s nephew).

Where a year prior Apur Sansar was Soumitra Chatterjee’s movie, Devi is likewise Sharmila Tagore’s. Tagore, sixteen years old upon the film’s release year, again finds herself in a role with little dialogue, even less than her supporting role in Apur Sansar. The moment Tagore’s Dayamayee becomes a devotional figure, her dialogue and ability to exert her own agency disappears. Until Umaprasad returns home shortly after the halfway mark, so much of Tagore’s performance before and after seems spliced from a great silent film. Perched on a small block, a pedestal if you will, she almost never looks at the camera or those intoning “Mā” (“Mother” in Bengali; Kali is the avatar of Durga, and both are forms of the Mother Goddess, Devi) as men and women pray and prostrate themselves in front of her. At times, Dayamayee’s mental and physical exhaustion is clear, even if she is looking sideways or into the ground, as she sits in place for several hours at a time. Is there any one there to make sure that this “goddess” is properly being taken care of? It seems doubtful.

It is unclear how long it takes for word to reach Umaprasad in order for him to return home to see the daily scenes at his family’s residence. Even for less than a day, this whole situation is intolerable to Dayamayee. Her resignation is evident in her slightly hunched back, unable to find a psychological or physical escape. The scene where Umaprasad returns home to see Dayamayee venerated as a goddess contains striking facial acting from both Tagore and Chatterjee. In Chatterjee, we see Umaprasad comprehending the situation in real time, as his horror renders him almost speechless. In Tagore, Dayamayee looks up, and in a figment of hope, there is utter heartbreak. These long days of adoration and miracle-seeking pilgrims have even shaken her sense of reality, as almost all vestiges of her past life wither away. In a rare private moment with Umaprasad, she questions her very being: “But what if I am a goddess?”

Satyajit Ray, who also wrote this screenplay based on the 1899 Bengali short story of the same name by Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyay, was part of the Brahmo Samaj movement, which advocates for a monotheistic interpretation of Hinduism. Brahmos, crucially, reject the caste system and avatars/incarnations of gods and goddesses. Ray’s adherence to the reforms of Brahmo Samaj color his filmography more obviously as his career progresses (I have not seen too much of Ray’s work, but I have not yet encountered a film of his that inelegantly portrayed his beliefs). Ray’s reformist and Western-leaning stances are embodied by Chatterjee’s Umaprasad, who we see clash with his more traditional father over social mores (the latter is distrustful of his son’s education, and derides his son for supposedly espousing Christian beliefs). Except for the scenes of a religious procession immediately after the opening credits, at no point does Ray imbue any of the religious images with any sense of glory, wonder, or veneration. Cinematographer Subrata Mitra (the Apu trilogy, 1966’s Nayak) dispenses of any ethereal lighting until the closing seconds, and his medium to close shots capture the uncomfortable anguish on both sides – Dayamayee’s alternating ambivalence and despair, the worshippers’ desire for comfort, deliverance, and the miraculous.

Like in several of Ray’s films including Mahapurush and Ganashatru (An Enemy of the People) (1989), Devi rejects dogmatism, miracles, superstitions, and anything that cannot have a rational or scientific explanation. Simultaneously, Ray realizes that most Indians, in the face of events profound and improbable, find science and rationality cold, confusing, and unsatisfying. Faith endows meaning to such moments. Faith ascribes purpose to happiness and suffering – something rationalism cannot provide. The unsuitability of both to provide a solution in Devi is the film’s secondary tragedy, as belief systems confront a scenario where a middle ground is impossible.

Devi’s principal tragedy is the religious objectification of Dayamayee. Of all of Ray’s female protagonists from Pather Panchali (1955) to this point, none of them are as constrained as Tagore’s Dayamayee. She may not live in poverty like Apu’s sister and mother in the Apu trilogy, nor is she the wife of an indulgent husband (1958’s Jalsāghar or The Music Room). And though she is not bound by shackles or subject to physical or sexual abuse, Dayamayee is nevertheless a victim of the unpredictable whims of men (and it is almost entirely men who worship her). Her portrayal is nuanced: she does not succumb entirely to self-pity, nor does she possess the strength to tell her father-in-law and his fellow worshippers to halt their devotional displays. She is aware of the communal damage she will cause if she so much renounces her unwanted divinity. At the same time, she cannot help but yearn for freedom, for others to speak to her like a human again – complete with aspirations, desires, and fears that no one can associate with a god.

Too often in cinema – wherever and whenever it hails from, including midcentury India – women play simplistic roles: the lover, the damsel in distress, the spurned wife. Where numerous filmmakers and actresses in the Hollywood Studio System were actively working to dismantle this element of patriarchy, I do not detect a similar level of rebellion in mainstream Indian cinema in the 1950s and 1960s (and, to some extent, this remains true). Ray did not stand alone in attempting to endow female characters with complexity (within and outside Bengali cinema), but his contributions to this development within the context of midcentury Indian cinema are crucial. Many of his films attempt a cinematic dialogue that critiqued patriarchal abuses with subtlety and bluntness – often to the chagrin of the public and government officials. The public outrage following Devi’s initial domestic release saw the film banned from seeking international distribution. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru intervened and reversed that decision.

Nevertheless, consider some of the works in Ray’s first decade as a filmmaker: The Apu trilogy, Devi, Teen Kanya (1961), The Big City (1963), and Charulata (1964). Together, all seven of those films reveal a filmmaker willing to take mainstream Indian filmmaking to task for regressive and simplistic portrayals of women, whether in lead or supporting roles. Devi might be the most shattering of that collection, caught between human weakness and the unknowability of the divine.

My rating: 8.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

* There were no child marriage laws in India in the nineteenth century, when this film is set. Child marriage remains prevalent in India, despite loophole-filled laws and a lack of enforcement.

‡ Multiple spellings of the protagonist's name are out there from reputable sources. I am using either the most or second-most common spelling here.

#Devi#The Goddess#Satyajit Ray#Sharmila Tagore#Soumitra Chatterjee#Chhabi Biswas#Purnendu Mukherjee#Karuna Banerjee#Arpan Chowdhury#Anil Chatterjee#Subrata Mitra#Dulal Dutta#Ustad Ali Akbar Khan#Bengali cinema#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shubho Mahurat শুভ মহরৎ (2003) Dir. Rituparno Ghosh

#indian cinema#bengali cinema#bangla movie#bangla cinema#sharmila tagore#rakhee#nandita das#dir. rituparno ghosh

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Satyajit Ray's 1960 film "DEVI" is fucking phenomenal and if anyone is reading this you should watch it but also watch the interviews with Sharmila Tagore (playing Doya) and Soumitra Chatterjee (playing Uma) from the 2013 Criterion Collection.

The film itself is stunning and incredibly powerful with some of the most haunting shots of just raw emotion I've ever seen conveyed.

the interviews make you appreciate it even more, especially the prayer song (a devotional/shyma sangeet form styled after the poet Ramprasad Sen) that Ray wrote for the film.

highly recommend it shall be joining Queen (2014) and Scooby Doo and the Witch's Ghost as one of my most favorite films

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mississippi Masala (1991) | dir. Mira Nair

#mississippi masala#mira nair#roshan seth#sharmila tagore#denzel washington#sarita choudhury#films#movies#cinematography#scenery#screencaps

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharmila Tagore in Anupama (1966) | dir. Hrishikesh Mukherjee

#anupama#anupama 1966#sharmila tagore#hrishikesh mukherjee#indian cinema#cinema#movies#films#hindi cinema#classic cinema#bollywood#old bollywood#south asian cinema#asian cinema#classic bollywood#world cinema#1960s#cinematography#screencaps#film scenes#movie scenes#indian films#indian movies#hindi films#hindi movies#bollywood films#bollywood movies#indian actress

52 notes

·

View notes