#Seattle History

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

You saw me standing alone...

#aesthetic#aesthetics#seattle#washington#washington state#the blue moon#tavern#blue moon#the blue moon tavern#Seattle dive bar#bars#taverns#Seattle nightlife#Seattle history#vintage#vintage Seattle#vintage signs#city scene#city#cityscape#street photography#street

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

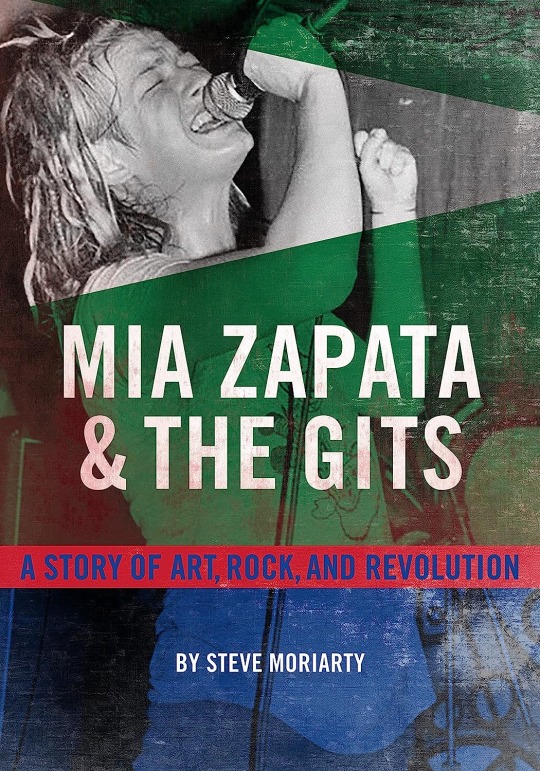

ATTENTION ALL GITS FANS!

I'm super excited to announce the most official biography you'll find of The Gits, written by their original drummer, (and my good buddy) Steve Moriarty. This book has been several years in the making, composed of heartfelt personal stories, meticulous research of Zapata history, and a true labor of love by one of Mia's closest friends. I had a tiny hand in editing a portion of the book so trust me when I say, this is the ultimate must-have guide to Mia Zapata. ❤️

Mia Zapata and The Gits: A True Story of Art, Rock, and Revolution - Hitting your eyes in August of 2024.

Pre-order your copy now on Amazon.

#please do share#mia zapata#the gits#viva zapata#steve moriarty#seattle music scene#punk rock#grunge#seattle history

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

2021

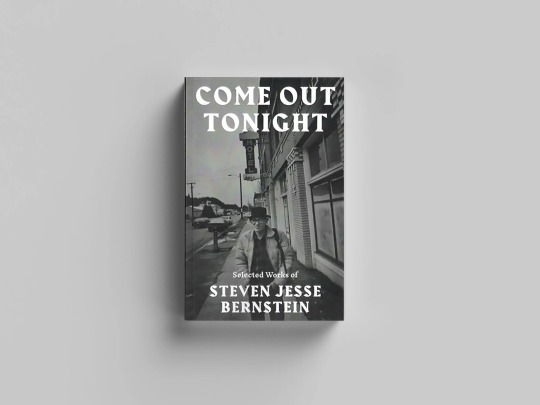

#history#photography#portrait#art#black and white photography#literature#writing#modernism#book#book cover#steven jesse bernstein#poetry#come out tonight#modern poetry#2010s#2021#seattle#washington state#seattle history#washington state history#pacific northwest history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#King Street#Seattle#Pacific Northwest#PNW#PNW Architecture#Pacific Northwest History#Seattle History#Historic Buildings

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hidden mural in Pike Place Market - used to be the exterior of the LaSalle building.

0 notes

Text

Dave Beck

#history#vintage#photography#portrait#black and white photography#american history#us history#dave beck#union#unions#union history#teamsters#teamster#teamster history#u.s.#u.s. history#twentieth century history#twentieth century#20th century history#20th century#seattle#seattle history#washington state#pacific northwest#washington state history#pacific northwest history#america#american

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The legacy of a Japanese American family's variety store When president Roosevelt signed executive order 9066, over 100,00 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry were interned in relocation centers, far from the West Coast. In most cases the farms, homes and businesses they were forced to leave were lost or taken over. — Read the rest https://boingboing.net/2023/03/21/the-legacy-of-a-japanese-american-familys-variety-store.html

0 notes

Link

May 29, 2022

The Duwamish people had some 17 villages and 93 buildings including longhouses on the banks of rivers, lakes, and bays, homes to families linked by alliances of trade and marriage. In the 19th century, non-Native settlers would bring death, destruction and displacement. Settlers tried to push out the first residents of the new city, named for an Indigenous leader they called Chief Seattle, whose signatory X comes first on the Treaty of Point Elliott for the “Dwamish and Suquamish tribes,” ceding Native lands.

Settlers filled the estuaries. Straightened, dredged and straitjacketed the rivers with levees. Hardened the shore of the bay. An entire river, the Black, was sacrificed to create a new connection from Lake Washington to saltwater through the Ballard Locks. Native families were sent to reservations all over the region, to be converted to farmers. Their children were forced into boarding schools intended to destroy their language and culture.

Now a new struggle between the descendants of the survivors of this violence is underway. With ads on television and the web and in newspapers they contest: Who are the “real” Duwamish? This comes as the Duwamish Tribe once more is seeking federal recognition that it is in fact a tribe, in a federal lawsuit filed May 11. Meanwhile, an online fundraising campaign has raised millions of dollars in so-called “Real Rent” for the Duwamish. This claim to sovereign status is at odds with rulings of federal evaluators who have repeatedly found this group of Duwamish descendants are not a continuation of the historic Duwamish Tribe and do not meet the criteria to be federally recognized.

Leaders at the Muckleshoot, Suquamish, Tulalip and Puyallup tribes, among the most prominent in the region, all strongly oppose the Duwamish group’s claim to federal recognition. They also see in well-meaning non-Indian support for Duwamish tribal status — gaining popularity in Seattle in an age of social-justice reckoning — a disregard and devaluation of what it means to be a tribal government. Such endorsements, to recognize tribes, are just one more violation that brings some Native leaders to tears over an unending battle to maintain their culture, identity, history, government, health and well-being.

“It’s such a catchy narrative especially if you are coming from a point of believing in social justice and doing the right thing: ‘This poor beleaguered tribe, they were left without,’ ” said Donny Stevenson, vice chairman of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe. “It is a far more complicated story than that … The problem is they are not who they say they are.”

Cecile Hansen, 85, of Burien, is a great-great-grandniece of Chief Seattle and chairwoman of the Duwamish Tribe. She has been at the forefront of the Duwamish push for recognition since the start of its first filing to the U.S. Department of Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1977. “We are not in any big battle with them,” Hansen said of the area’s recognized tribes. “We are just trying to correct the injustice of not being acknowledged by the federal government. That is what this is about. I am sorry they are offended. We don’t want anything from them.”

There is a lot wrapped up in the Duwamish challenge to the status quo, potentially, from competition from a new casino, to a move for treaty fishing and hunting rights — even a re-rack of membership rolls at recognized tribes, where many people today have some degree of Duwamish ancestry, including the entire Suquamish tribal council and about 95% of the people at Muckleshoot.

To explore this controversy The Seattle Times, through months of interviews and other research, has taken a look all the way back to who and what was here before. Recounted were different histories and choices made by the ancestors of Native people living here today, and stories of survival after the arrival of settlers who burned their ancestors’ homes and destroyed the natural abundance that had sustained their families for generations uncounted. They told of the forced treaty that pushed families out of their home territories to reservations, established to get Native people out of the settlers’ way. Some of their ancestors went to these reservations. Some stayed in Seattle and its environs. Others dispersed into settler society all over Western Washington. What emerged is a story of a traumatic diaspora, so very recent it reverberates today.

Apocalypse

The first written record of a non-Native expedition in Puget Sound comes from Captain George Vancouver and his crew aboard the Discovery in 1792. The explorers noted communities already marked and devastated by smallpox and other diseases that had swept through Northwest Native coastal communities (brought perhaps by the Spanish beginning in about the 1770s), terrorizing and disrupting their societies with a death force they could not control and did not understand.

The Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Nisqually in 1833 for a year-round supply of beaver, otter and other pelts for trade. Reports from the U.S. Exploring Expedition, led by Charles Wilkes from 1838 to 1842, enticed white settlers to Puget Sound. By the mid- 1850s, the region had a few hundred non-Native residents living around Fort Nisqually, Fort Steilacoom, Tumwater and on Whidbey Island. The arrival of the Denny Party at Alki Point in 1851 was not the Native peoples’ first contact there with non-Indians — explorers and traders had been in the area, and the Collins Party had already arrived to stake homestead claims at the Duwamish River.

They encountered not an empty wilderness, but Native people and rich cultures along the Duwamish watershed and beyond. Natives vastly outnumbered early settlers. But this would soon change. The United States, concerned by Russian and British incursions in Oregon Territory, in 1850 offered 320 acres to each white male U.S. citizen 18 years or older — 640 acres to married couples — who arrived in Oregon Territory (extending over what would become the states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho and parts of Wyoming and Montana) and resided on their claim for four years. This accelerated settlement, and it raised the awkward fact the U.S. did not own the lands it was giving away. To aid non-Native settlement of Washington Territory, created by Congress in 1853, Washington Territorial Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs Isaac Stevens worked to secure treaties with Native peoples of the region. His goal was to buy lands as cheaply as he could and remove Native people to as few and as small reservations as possible. This he did on behalf of settlers backed by armies that already were taking by force what could not be gotten by convening a treaty conference.

Isaac Stevens arrived at the treaty grounds in present-day Mukilteo in January 1855. Thousands of Native people had been gathered there for a treaty council. He carried a template treaty last used with the Omaha Indians. He came not to negotiate, but to dictate terms. This would be the second of 10 treaties Stevens would execute on behalf of the U.S., from Western Montana to Neah Bay on the Olympic Peninsula, over just 13 months.

To create parties and signatories for the Treaty of Point Elliott, Stevens recognized Chief Seattle, of the Suquamish and Duwamish, with Duwamish used to include all the groups living along the river and all the lakes and streams draining into it, including present-day Lake Washington. In so doing, Stevens was inventing power for Chief Seattle to sign away lands he had no authority to cede from fluid groups of Native people. On a document twice translated, first from English to Chinook jargon, a limited trade language, and then to Native dialects, the treaty’s terms were laid out. The Great Father (another invention, meaning the U.S. president, representing the authority of the federal government) would pay $150,000 for a vast swath of Native territory including all of present-day Snohomish, Skagit, Whatcom, Island and San Juan counties, most of King County and parts of Kitsap and Pierce counties.

Four reservations were made that would be known as Suquamish, Lummi, Swinomish and Tulalip. Other promises were made to the Native people that day, too, the most important of which to Native negotiators was that they could forever fish, gather and hunt in their usual places — beyond the reservations.

By October, some Natives attacked and killed settlers in South King County and in Thurston County. Skirmishes continued, culminating in the Battle of Seattle in January 1856, the result of Native frustration with tiny reservations that forced some Natives to live away from home with people they neither knew nor liked. In response, the U.S. in 1857, among other changes, created another reservation at Muckleshoot. It was named for the prairie where it was established. It was created for Native people of the upper White and Green rivers in the Duwamish watershed. But it also might be a place, some U.S. officials thought, for Lower Duwamish people who refused to relocate to the Suquamish Reservation, as intended, and persisted in living in villages at the Black River, once a tributary of the Duwamish River near present day Renton.

By 1865, the new government of Seattle was adopting its first ordinances — including Ordinance 5 that called for removal of Indians from the town. The ordinance was not re-enacted when the town reincorporated in 1869 — but the discrimination that inspired it remained. Some settlers wanted Native people in their midst — they needed their labor. But in 1866, settlers successfully raised a petition to snuff efforts to create another separate reservation at the Black River for the Duwamish people, as some U.S. officials were calling for.

Beginning in the 1880s, Native parents were forced to send their children to boarding schools where their culture was destroyed and abuse was rampant. In 1893, settlers burned Herring’s House, the last Duwamish longhouse on the estuary of the river for whom they were named. By the early 1900s, work had begun to dredge and straighten the Duwamish River and fill the tide flats, rich with clams, and the wetlands, sloughs and side channels alive with ducks and salmon. A wholesale destruction of the natural abundance of the land and water was underway by settlers for their burgeoning industries.

In 1916, the Black River disappeared as Lake Washington was lowered 9 feet in the construction of the Ballard Locks. Gone were the waterway and salmon that had sustained Duwamish villages at the Black. Some Natives were starving in their own homeland. Reservation life meant living where traditional ceremonies were suppressed; travel off the reservation was monitored, and Christianity was imposed. Native fishers, hunters and gatherers were instructed to clear dense forests and farm potatoes.

As settlers prospered, Native people tried a variety of strategies to survive, including wage work and farm labor. Some Duwamish people moved to the established reservations. Other Native families stayed where they were in Seattle and surrounding areas, working and persisting in what had always been their home. Others assimilated into settler society all over western Washington.

“They are getting pushed out of the city, they are getting burned out of the city and engineered out of the city, making it harder to fish the Black River, to gather seafood,” said Joshua L. Reid, a citizen of the Snohomish Tribe of Indians and associate professor of history and American Indian Studies at the University of Washington. “Do you follow those kinship connections and take up citizenship at Lummi, at Tulalip, at Muckleshoot, or do we stay here and try to eke out an existence and hope eventually to get a reservation? Those are the devil’s bargain decisions families are making, that is how different Duwamish families ended up at these different tribal nations, while others stayed here, while trying to make it as Duwamish in the greater Seattle area.” Racism in non-Indian society and poverty on the reservations remained rampant. It was not unusual, notes Duwamish tribal councilman Ken Workman, for Indian people to hide in plain sight. His own family did not tell him he was descended from Chief Seattle.

Then, in 1974, U.S. District Court Judge George Boldt affirmed for tribes signatory to the Stevens treaties their reserved fishing rights to half the catch, anywhere within their traditional fishing places. And in 1988, Congress authorized casino-style gambling by tribal governments with proceeds going to their government programs. In this region, these policies were the earthquakes that transformed the stakes both for federal recognition as tribal governments, and enrollment for Native people in recognized tribes.

The Duwamish fight for recognition

The Duwamish Tribe’s fight for federal recognition hinges not on whether the Duwamish petitioners descend from historical Duwamish Indians; evaluators have found most of them do. Instead the fight is over whether this group maintained a distinct Indian identity and community, and exercised political influence and authority over its members since 1900 that distinguishes them as an Indian tribe from a voluntary association of Native descendants.

This is because the settler-colonial framework imposed on the nation’s first people continues today, with seven requirements set by the federal government by which it determines the tribal governments it will recognize. Federal recognition of a tribal government has limited, but powerful meaning. It goes beyond acknowledgment of ancestry. It recognizes that a group possesses and has maintained sovereign political authority since 1900. Federal recognition of tribal governmental authority establishes a diplomatic relationship of sorts between the U.S. and a tribal government, and obligation for consultation in certain federal government actions. Recognition also opens the door to certain federal benefits, for housing, health care and education, access to treaty fisheries and other resources through reserved communal tribal treaty rights, and the ability for tribal governments to run casinos with electronic slot machines to support tribal government programs.

The beginnings of the first petition for Duwamish federal recognition were filed by the Duwamish Tribe in 1977. Judge Boldt — the same judge who had affirmed tribal treaty fishing rights for Stevens treaty tribes — ruled in 1979 on a separate action for fishing rights that the Duwamish Tribe was not an entity that descended from any of the tribal entities that were signatory to the Treaty of Point Elliott. He found the petitioners had not maintained an organized tribal structure in a political sense. He denied the group treaty rights and stated its relations with the U.S. government were more like a social or business group. Boldt also stated his use of the word “tribe” in the ruling did not indicate a finding or conclusion that the Duwamish Tribe actually was an Indian tribe, as the federal government defines it, at all.

His decision was upheld by the Court of Appeals in 1981. The U.S. Supreme Court declined review. Federal evaluators at the U.S. Department of Interior subsequently noted in multiple findings against recognition that the Duwamish group filing for recognition was first organized in 1925 as the Duwamish Tribal Organization (DTO), also known as the Duwamish Tribal Council and other subsequent names. These evaluators found the group played only a limited role in its members’ lives. It did not maintain a distinct tribal community or exercise political influence over its members as required of a tribe. The DTO was not a continuation of the historic Duwamish Tribe, they found.

There was one near miss at recognition along the way, the result of the acting assistant secretary of Interior in the last hours of the Clinton administration, overruling a finding against recognition by the nonpartisan professional staff, according to an Interior Department inspector general report initiated after an investigative series by The Boston Globe. Charges were not filed against the official, Michael Anderson, for getting a staff member to bring him the papers two days after the next administration took office, to sign in his car outside of the Interior building. The Bush Administration paused his finding for recognition, then in the fall of 2001 reversed it.

Another look by the Obama administration in 2015 again found insufficient basis for federal recognition of the Duwamish group as an Indian tribal government: “… Observers identified two traditional Duwamish villages on the Black and Cedar Rivers as late as 1900, but there is no evidence that the ancestors of the DTO petitioner were part of these villages or that they evolved to become the DTO organization … The villages noted on maps located on the Cedar and Black River most likely did not exist after 1907, but at any rate, they were not the petitioner.” The denial was upheld by the Interior Board of Indian Appeals in April 2019, and the secretary of the Interior in July 2019. It’s a process, said Reid, at the UW, that seems to be geared toward denial, and doesn’t account for the reality of settler colonialism. “How can you maintain a tribal government when you are burned out of your tribal homelands … those types of requirements in the paperwork and processing do not account for the reality.”

The Duwamish are going back to federal court, alleging the process on their recognition petition has never been fair and that evaluators made egregious errors. Despite all the violence against her people, they never disappeared, said Hansen, Duwamish tribal chairwoman since 1975. “They burned down all the longhouses. They ruined the village that was right there behind the Fred Meyer (in Renton) that is where our village was, there are apartments built on top of those people buried there; in fact the city is built all over our people,” Hansen said. “But we survived and we are still here, there is no gap where we disappeared off the face of the Earth.”

In the lawsuit, the tribe argues the federal government dealt with the Duwamish as a tribe in the past, including at treaty signing, and recognition was never extinguished by Congress, the only entity empowered to do so. Previous federal findings that the tribe ceased to function as a continuous community and government aren’t true in either fact or law, according to the suit. In the suit the tribe lists 10 tribal leaders in a continuous line since before the signing of the treaty. The tribe also documents actions by the U.S. and federal officials that time and again since 1859 recognized the Duwamish Tribe. “Beginning in 1859 through at least the 1970s, dozens of acts of Congress and two U.S. courts have recognized the Duwamish Tribe as an Indian tribe and the successor in interest to the Tribe that signed the Treaty of Point Elliott,” the suit contends. “Congress has neither abrogated its recognition of the Duwamish Tribe nor otherwise limited the Tribe’s rights.”

The suit also argues the federal government has illegally discriminated against the matriarchal tribe by discounting members descended from marriages between Duwamish women and non-Indian men — a violation of the federal equal protection clause under the Fifth Amendment. The U.S. Department of Interior also did not use rules more favorable to the tribe when considering its prior filing, according to the suit, which was brought against Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland and other federal officials. Duwamish leaders say they have hopes of moving the Biden administration, with its first-ever Native secretary of Interior, to a new finding. The Duwamish also are expected to make a push for recognition in Congress, a path sought unsuccessfully in the past.

Gaining attention

While the fight for federal recognition continues, the Duwamish Tribe has had significant success in gaining a kind of social recognition, stoked by a time of reckoning in racial and social justice — and internet fundraising. Today it is common at many types of gatherings in Seattle to acknowledge the Duwamish as a tribe. Hansen was invited as tribal chairwoman to throw out the first pitch for the Mariners on opening day in 2021. The city of Seattle last year approved a $900,000 grant to the Shared Spaces Foundation intended to buy and return land back to the Duwamish Tribe. The Seattle Times’ editorial board last June called for federal recognition for the Duwamish.

All of this has raised hope at the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center along West Marginal Way, where the nonprofit Duwamish Tribal Services operates. Inside its graceful spaces are a museum dedicated to Duwamish history, a gift shop, a space for gatherings and offices for staff. Here the Duwamish Tribe hosts teas for supporters, holds culture classes and marshals services for members. At duwamishtribe.org, visitors are urged to write letters to support federal recognition and sign an online petition, and there is a link to contribute to Duwamish Tribal Services through the continuous online fundraising campaign, Real Rent Duwamish, launched in 2017 by non-Indian volunteers — today with some 20,000 contributors.

Contributions to Duwamish Tribal Services have grown since Real Rent donations began, and topped $1.5 million reported in the fiscal year 2019 Internal Revenue Service Form 990, the most recent available. On its website the Duwamish urge support for “the host tribe of Seattle, our area’s only Indigenous tribe.” Absence of federal recognition does not bar the creation or maintenance of a Native social or cultural entity, or stop local governments, states or other organizations from recognizing such a group as an Indian tribe.

But it incenses federally recognized tribes, who see in these resolutions and declarations a false and insulting equivalency that devalues Indigenous sovereignty, culture, identity, history and government.

Growing pushback

Duwamish claims to host status for Seattle and its long running recognition campaign are strongly contested by federally recognized tribes. “We feel that the … narrative that they are the host tribe for Seattle ignores the other tribes who were and are present in Seattle to this day,” said Leonard Forsman, chairman of the Suquamish Tribe. He also is the fourth-great-grandson on his father’s side of xtca? tcldax David, Chief Seattle’s brother, and is president of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians, a nonprofit representing 57 tribal governments.

More than half the members of the Suquamish tribe have Duwamish ancestry, and some of the very first people to settle at the Suquamish reservation at Port Madison were Duwamish. The reservation included the Suquamish mother village around Old Man House — Chief Seattle’s longhouse — the largest longhouse in the region until it was burned by the U.S. government in 1870.

“The Suquamish had villages on the Seattle side, as did other Salish tribes,” Forsman said. “The Suquamish Tribe has always been active in the city of Seattle. Chief Seattle lived here at Old Man House and is buried here, in Suquamish, at our cemetery. There are Duwamish people on this reservation. There are prominent Duwamish families that are well represented here, at Muckleshoot, and elsewhere,” Forsman said. “When you lead a tribe you have to be inclusive. Include everybody you can. DTO ignores the other Duwamish people of Puget Sound.” At Muckleshoot, where today most of the enrolled members are of some degree of Duwamish descent, their ancestors fought, and some died, to establish lives under the hardest of circumstances amid poverty and rampant racism to live at the reservation, rather than assimilate in Seattle, said Jaison Elkins, chairman of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe.

The tribe’s opposition isn’t over economic competition, Elkins said, noting that the Muckleshoot did not oppose the Snoqualmie Tribe over its successful fight for recognition. It’s much deeper than money. “We are opposed to them because they are stealing our history and culture and our stories and appropriating them for themselves,” Elkins said. “That is why this is a conflict for us. Everything we fought for, they are trying to undermine it, or get that same status as us.”

Virginia Cross, a Muckleshoot tribal council member and lifelong educator, is one of the longest-standing elected officials in Washington state. She remembers her family carrying water to their shack across the street from where the tribe’s casino now stands — and when the tribe was so poor and vilified. “When we were fighting, they were not there,” Cross said of the Duwamish Tribe. “They want what we have, and they are not entitled to it. They are trying to get that government-to-government relationship that our ancestors fought so hard to maintain.”

Stevenson, the Muckleshoot tribal council vice chairman, notes the finding by multiple federal evaluators that the Duwamish group is not a tribe. “It is a form of identity theft, it is also a form of cultural appropriation,” said Stevenson. He sees a cynical effort to prey on good intentions of well-meaning people to gain sympathy — and money. “A lot of good people are very awake to the plight that the Native American people have suffered, and they want to help and do what is right,” Stevenson said. “This group has tapped into that, they are taking advantage under false pretenses.”

In letters, op-eds and advertising campaigns, the Muckleshoot, Suquamish, Puyallup and Tulalip Tribes note people of Duwamish ancestry are not forgotten or sidelined, many are enrolled today at tribes all around Puget Sound and enjoy all the rights and benefits of tribal citizenship. Hansen — who herself is enrolled at Suquamish, along with several members of her family — said she has no regrets and no retractions. “They should mind their own business,” she said of the area’s recognized tribes.

UW’s Reid sees recognized tribes just trying to defend their own people’s interest. If the Duwamish are recognized, where is that reservation land going to be, what happens when they begin to pursue economic development, and what cost will that be to the others? Reid asked. “It’s part of the colonial system that pits us against each other, and that is why it appears to be such an ugly situation.”

Ryan Miller, director of treaty rights and government affairs for the Tulalip Tribes, said his third-great-grandfather Salalque, or Pilchuck Charlie, was at the signing of the Treaty of Point Elliott. He wishes instead of paying Real Rent, non-Natives who want to help Native people would focus on — and keep — their part of the bargain made that day. The treaty is a powerful, permanent legal commitment — the highest law of the land per the Constitution — and is defended by the U.S. government and tribal governments all over the region who continue to work to enforce it, on and off reservations that were created for Native people of the Seattle region, including the Duwamish people. “They have as much meaning today as they did when they were signed,” Miller said of the treaty promises. “And this is not just a treaty for the tribes, it is for everyone.” The treaty protects everyone living here today — and is why they live here not as visitors or squatters. Rather, Miller said, all people living here today are neighbors, bound together to uphold the treaty. Yet these are promises still not kept. Treaty tribes’ rights were reserved forever to hunt, fish and gather where they always had, off the reservation. Lands and waters that today are paved, dammed, diked, dredged, filled and industrialized beyond recognition are increasingly bereft of salmon, game, roots, berries, plants and medicines central to Native cultures. Miller thinks of his ancestors who went to live on the reservation at Tulalip after the treaty. He wants the treaty, and the meaning of tribal governmental recognition, honored.

“Do you think it was easy for them? To leave where they had been and send their kids to boarding school, to have the Indian agent tell them what they could and could not do? I think people forget how difficult it was for Native people and the decisions they had to make. These people wanted to keep their family together and kept their culture alive. “All of this is here today because of the sacrifices they made.” As the battle continues, camas are in bloom in prairies diminished to less than 3% of their original extent in Puget Sound country. Another salmon season begins in rivers struggling for life. The Black River today is a dammed stream 2 miles long that neighbors a garbage sorting depot, a concrete recycling yard and a sewage treatment plant. The Duwamish Waterway is a Superfund site. A decision on the Duwamish Tribe’s lawsuit is likely years away.

#Duwamish#Suquamish#Muckleshoot#Treaty of Point Elliot#colonialism#displacement#Chief Sealth#Chief Seattle#Seattle#Seattle history#Washington state#Washington state history#american history#american colonial history#19th century#pnw natives#Native Americans#treaties

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

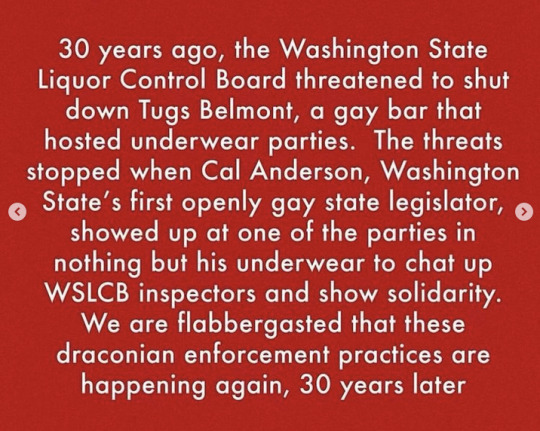

Bar raids should be a thing of the past but police are allowed to selectively enforce laws against queer and trans people. As long as policing continues to exist, so will the attacks on our spaces. https://www.them.us/story/two-seattle-gay-bars-received-lewd-conduct-citations-owners-demand-answers

356 notes

·

View notes

Text

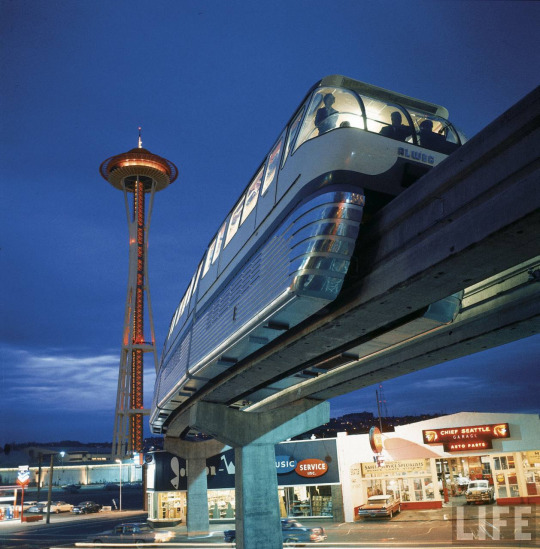

Monorail and Space Needle in Seattle during the Century 21 Exposition, April 1962. Photo by Ralph Crane.

542 notes

·

View notes

Photo

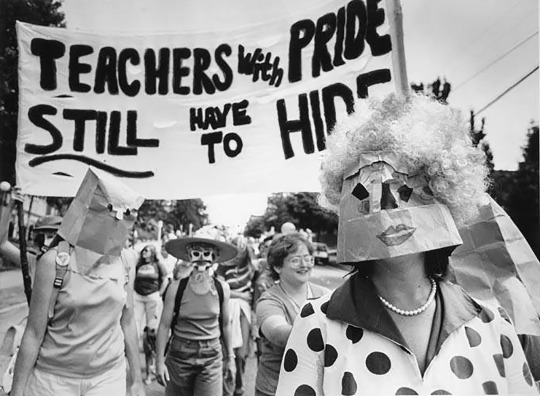

Teachers with Pride Still Have to Hide

Gay schoolteachers wearing masks at parade, June 28, 1986

In this image, Seattle schoolteachers participating in the Gay Freedom Day parade through the Capitol Hill neighborhood hold a banner reading "Teachers with Pride Still Have to Hide," and wear masks to protest the discrimination they have felt. An estimated 10,000 people participated in the event, which is part of Seattle's annual Gay Pride Week.

[ 📷 Jennifer Werner-Jones / Seattle Post-Intelligencer ]

oh, how times have changed!

#queer history#teachers#teacher#pride month#🌈#🏳️🌈#🦄#🏳️⚧️#1980s#80s#1986#queer#school#florida#book ban#book bans#librarians#librarian#anti trans legislation#anti woke legislation#pride march#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbqti#discrimination#demonstration#protest#seattle#capitol hill#cap hill

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

People really should watch sports. Or at least engage with some type of competitive real-time skill-based community: esports, chess, speedrunning, etc. Each community has a rich intersection of history, culture, technical knowledge, and broader societal impact (not all of it good and/or accessible, but there's always a way), and experiencing that can really teach you a lot about humanity and the world we live in.

This post brought to you by everyone who compares Blaseball with 17776/20020 sounding like the "getting a lot of boss baby vibes from this" meme. That's sports fandom culture. What you've identified is sports fandom culture.

Blaseball and 17776 aren't offering an alternative to sports, they're a commentary and a celebration, in the most morally neutral sense of that word. They're both an exaggeration of the most ridiculous or unfair elements and an idealization of what sports could be. Sports are powerful, sports are human. That's the point.

#my stuff#like yeah they have a lot in common beyond that but#'enjoying rule-bending events' and 'focusing on broader player/community narratives' are not exclusive to these works#I'm begging y'all watch some of jon bois's other stuff it will contextualize a lot#17776#blaseball#bob emergency and history of the seattle mariners are probably the best places to start

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

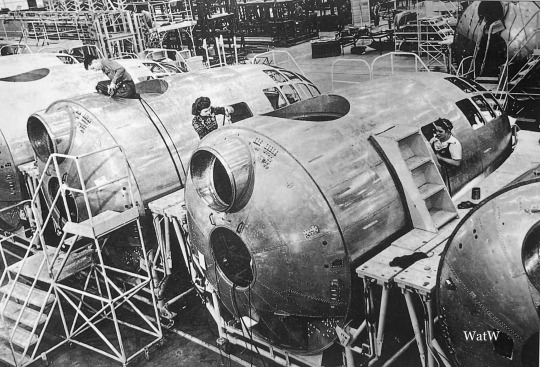

Women workers work on the fuselage of the B-29 Superfortress bomber in the Boeing plant - Seattle, USA, date unknown

#world war two#ww2#worldwar2photos#history#1940s#ww2 history#wwii#world war 2#ww2history#wwii era#assembly plant#Seattle#washington dc#washington#USA#Boeing#b29

107 notes

·

View notes