#Scythian-Saka period

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I remember posting a story some time ago about another pyramid from the same area. Maybe it was the same one? Couldn't find the story in the archives, unfortunately.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shirdal 'Lion-Eagle' Talon Abraxas

Ancient origins of the griffin

A legendary creature with the body, tail, and back legs of a lion, the head and wings of an eagle, and, sometimes, an eagle's talons as its front feet first appears in ancient Iranian and Egyptian art dating back to before 3000 BCE. In Egypt, a griffin-like animal can be seen on a cosmetic palette from Hierakonpolis, known as the "Two Dog Palette", dated to 3300–3100 BCE. The divine storm-bird, Anzu, half man and half bird, associated with the chief sky god Enlil was revered by the ancient Sumerians and Akkadians. The Lamassu, a similar hybrid deity depicted with the body of a bull or lion, eagle's wings, and a human head, was a common guardian figure in Assyrian palaces.

In Iranian mythology, the griffin is called Shirdal, which means "Lion-Eagle." Shirdals appeared on cylinder seals from Susa as early as 3000 BCE. Shirdals also are common motifs in the art of Luristan, the North and North West region of Iran in the Iron Age, and Achaemenid art. The 15th century BCE frescoes in the Throne Room of the Bronze Age Palace of Knossos are among the earliest depictions of the mythical creatures in ancient Greek art. In Central Asia, the griffin image was later included in Scythian "animal style" artifacts of the 6th–4th centuries BCE.

In his Histories, Herodotus relates travelers' reports of a land in the northeast where griffins guard gold and where the North Wind issues from a mountain cave. Scholars have speculated that this location may be referring to the Dzungarian Gate, a mountain pass between China and Central Asia. Some modern scholars including Adrienne Mayor have theorized that the legend of the griffin was derived from numerous fossilized remains of Protoceratops found in conjunction with gold mining in the mountains of Scythia, present day eastern Kazakhstan. Recent linguistic and archaeological studies confirm that Greek and Roman trade with Saka-Scythian nomads flourished in that region from the 7th century BCE, when the semi-legendary Greek poet Aristeas wrote of his travels in the far north, to about 300 CE when Aelian reported details about the griffin - exactly the period during which griffins were most prominently featured in Greco-Roman art and literature. Mayor argues that over-repeated retelling and drawing or recopying its bony neck frill (which is rather fragile and may have been frequently broken or entirely weathered away) may have been thought to be large mammal-type external ears, and its beak treated as evidence of a part-bird nature that lead to bird-type wings being added. Others argue fragments of the neck frill may have been mistook for remnants of wings.

Lucius Flavius Philostratus (170 – 247/250 CE), a Greek sophist who lived during the reign of the Roman emperor Philip the Arab, in his "Life of Apollonius of Tyana" also writes about griffins that quarried gold because of the strength of their beak. He describes them as having the strength to overcome lions, elephants, and even dragons, although he notes they had no great power of flying long distances because their wings were not attached the same way as birds. He also described their feet webbed with red membranes. Philostratus says the creatures were found in India and venerated there as sacred to the sun. He observed that griffins were often drawn by Indian artists as yoked four abreast to represent the sun.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man from the Saka Kingdom of Khotan 7th-9th C. CE

"Saka, or Sakan, was a variety of Eastern Iranian languages, attested from the ancient Buddhist kingdoms of Khotan, Kashgar and Tumshuq in the Tarim Basin, in what is now southern Xinjiang, China. It is a Middle Iranian language. The two kingdoms differed in dialect, their speech known as Khotanese and Tumshuqese.

The Saka rulers of the western regions of the Indian subcontinent, such as the Indo-Scythians and Western Satraps, spoke practically the same language.

In the 11th century, it was remarked by Mahmud al-Kashgari that the people of Khotan still had their own language and script and did not know Turkic well. It is believed that the Tarim Basin became linguistically Turkified by the end of the 11th century [the Islamic Kara-Khanid conquest of Khotan].

Other than an inscription from Issyk kurgan that has been tentatively identified as Khotanese (although written in Kharosthi), all of the surviving documents originate from Khotan or Tumshuq. Khotanese is attested from over 2,300 texts preserved among the Dunhuang manuscripts, as opposed to just 15 texts in Tumshuqese. These were deciphered by Harold Walter Bailey. The earliest texts, from the fourth century, are mostly religious documents. There were several viharas in the Kingdom of Khotan and Buddhist translations are common at all periods of the documents. There are many reports to the royal court (called haṣḍa aurāsa) which are of historical importance, as well as private documents."

-taken from Wikipedia and Alphabet, A Key To The History Of Mankind by David Diringer

#scythian#ancient history#history#art#sculpture#statue#linguistics#indo european#china#ancient china#xinjiang

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 3,400-year-old Pyramid from the Scythian-Saka period found in Karaganda region of Kazakhstan

Arkeonews November 3, 2023 pyramid belonging to the Scythian-Saka period was found in the Karaganda region of Kazakhstan. Experts announced that the Karajartas mausoleum belongs to a ruler from the Begazı Dandibay period, which was the last phase of the Andronovo period. The pyramid, which was excavated over the course of four excavation seasons by archaeologists from Karaganda University, is…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

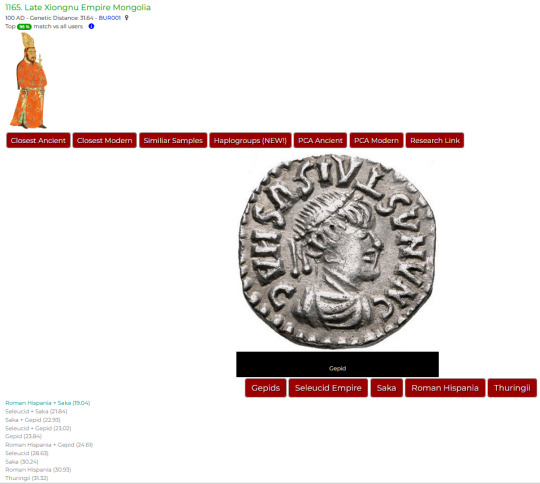

Ancient Indian Coins of Foreign Rulers

Introduction:

Ancient India is a land rich in history, culture, and diversity. Throughout the centuries, it witnessed the rise and fall of various empires, attracting foreign rulers from distant lands. One of the intriguing aspects of this period is the numismatic heritage left behind by these foreign powers. Coins minted by these rulers provide valuable insights into their reigns, their interactions with Indian society, and the fascinating blend of local and foreign influences. In this blog, we will embark on a numismatic journey, exploring the ancient Indian coins of foreign rulers and unraveling the stories they tell.

In ancient times, various foreign empires, such as the Romans, Portuguese, British Empire also ruled over India. During the Roman rule, they introduced their own coins for trade and commerce, known as Roman Empire coins. We possess a collection of currencies from different foreign kingdoms of Portuguese, British, Roman, and others. We have rare currencies and ancient coins such as the Silver Denarius in their period.

1.The Indo-Greeks: The Indo-Greeks were among the first foreign powers to establish their presence in India. Their coins, issued during the 2nd century BCE, serve as a testament to the cultural fusion that occurred during this period. We will delve into the designs, inscriptions, and artistic influences that characterize these coins, shedding light on the cross-cultural interactions between the Greeks and the Indians.

2.The Kushanas: The Kushan Empire, originating from Central Asia, had a significant impact on ancient Indian history. Their coins, minted from the 1st to the 3rd century CE, showcase a blend of Indian, Greek, and Persian artistic elements. We will examine the unique features of Kushana coins, such as the portrayal of rulers, deities, and the introduction of the Brahmi script.

3.The Indo-Scythians: The Indo-Scythians, also known as the Sakas, ruled parts of North India during the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE. Their coins display a distinct Scythian influence while incorporating Indian motifs and deities. We will explore the fascinating iconography and historical context behind these coins, highlighting the cultural amalgamation that occurred under the Indo-Scythian rule.

4.The Gupta Empire: The Gupta Empire is often regarded as the Golden Age of ancient India. The Gupta coins, minted between the 4th and 6th centuries CE, exemplify the pinnacle of artistic and metallurgical achievements. We will analyze the intricate Gupta coinage, which features Gupta rulers, mythological figures, and elaborate inscriptions, and discuss its significance in the context of Gupta society and culture.

5.The Islamic Dynasties: With the advent of Islamic rule in India, a new chapter unfolded in numismatic history. Coins issued by various Islamic dynasties, such as the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals, showcased a unique blend of Islamic calligraphy, Persian influences, and Indian artistic elements. We will explore the evolution of Islamic coinage in India and its role in shaping the socio-cultural landscape.

Importance of Ancient Indian Coins of Foreign Rulers:

1.Historical Documentation: Ancient coins provide valuable historical documentation about foreign rulers who held sway over different parts of Ancient India. These coins bear inscriptions, symbols, and portraits that help in identifying and understanding the rulers, their dynasties, and their political influence in the region.

2.Cultural Exchange: Coins issued by foreign rulers reflect the cultural exchange and interaction between Ancient India and other civilizations. They often incorporate elements of both the ruling civilization and the local Indian traditions, showcasing a fusion of artistic styles, religious symbolism, and linguistic influences.

3.Trade and Commerce: Coins played a vital role in facilitating trade and commerce in Ancient India. Foreign rulers minted their coins to assert their authority and facilitate economic transactions. The presence of foreign coins in Ancient India suggests the existence of trade networks and economic ties with other regions.

4.Economic History: The study of ancient coins provides insights into the economic history of Ancient India. The types of metals used, their purity, and the denominations reflect the prevailing economic systems, monetary policies, and the economic prosperity of the time.

5.Numismatic Research: Ancient coins serve as essential artifacts for numismatic research, which involves the study of coins. Scholars and collectors analyze these coins to determine their minting techniques, metal compositions, and design evolution over time. Such research contributes to a deeper understanding of ancient technology, craftsmanship, and artistic traditions.

6.Preservation of Heritage: Ancient coins are invaluable archaeological artifacts that preserve the heritage of Ancient India. By studying and preserving these coins, we can gain insights into the social, political, and economic structures of ancient societies, helping us reconstruct and appreciate our historical roots.

7.Educational and Cultural Value: Ancient coins have educational and cultural value. They provide a tangible connection to the past, allowing individuals to learn about and appreciate the history, art, and cultural diversity of Ancient India.

Advantages of Ancient India Coins of Foreign Rulers:

1.Historical Significance: Coins issued by foreign rulers in Ancient India provide valuable historical evidence about the political, cultural, and economic interactions between India and other regions. They offer insights into the periods of foreign rule and their impact on the Indian subcontinent.

2.Numismatic Value: Ancient coins, especially those from foreign rulers, have high numismatic value. Collectors and enthusiasts often seek out these coins for their rarity, craftsmanship, and historical significance. They can be valuable additions to coin collections and can appreciate in value over time.

3.Cultural Exchange: Coins from foreign rulers reflect the influence of different cultures and civilizations on Ancient India. They often feature unique designs, symbols, and inscriptions that represent the artistic traditions and ideologies of the ruling empire. They provide a glimpse into the diverse cultural heritage of the time.

4.Trade and Economic Relations: Coins issued by foreign rulers can offer insights into the trade and economic relations between Ancient India and other regions. They can provide information about the circulation of different currencies, the prevalence of specific trade routes, and the economic policies of foreign powers.

Disadvantages of Ancient India Coins of Foreign Rulers:

1.Loss of Sovereignty: Coins issued by foreign rulers signify a period of foreign domination and loss of political autonomy for Ancient India. They remind us of the subjugation and control exerted by outside powers, which can be a sensitive topic for some individuals or communities.

2.Fragmented History: Ancient coins, including those of foreign rulers, often present a fragmented historical narrative. They provide glimpses into specific rulers or periods but may not offer a comprehensive understanding of the broader historical context or the experiences of the local population.

3.Limited Information: While coins can provide valuable historical information, their inscriptions and designs may not always reveal detailed or complete information about the ruler, the ruling empire, or the events of the time. Some coins may lack inscriptions altogether, making their interpretation challenging.

4.Lack of Preservation: Ancient coins face the risk of damage, deterioration, and loss over time. Due to their age and historical significance, it can be difficult to preserve and protect these coins adequately. This poses a challenge for historians, archaeologists, and collectors interested in studying or appreciating them.

Conclusion:

Ancient Indian coins of foreign rulers provide a glimpse into the multicultural tapestry of India's past. From the Indo-Greeks to the Islamic dynasties, each coinage reflects the dynamic interplay between different civilizations, religions, and artistic traditions. By studying these numismatic artifacts, we gain a deeper understanding of the historical, cultural, and economic interactions that shaped ancient India.

#Roman Empire Coins#Silver Denarius Coins#Rare Roman Currency Coins.Silver Denarius Coins#Rare Roman Currency Coins#Ancient Roman Coins#Ancient Roman Denarius Coins#Denarius Coins#Roman Currency Coins.

0 notes

Photo

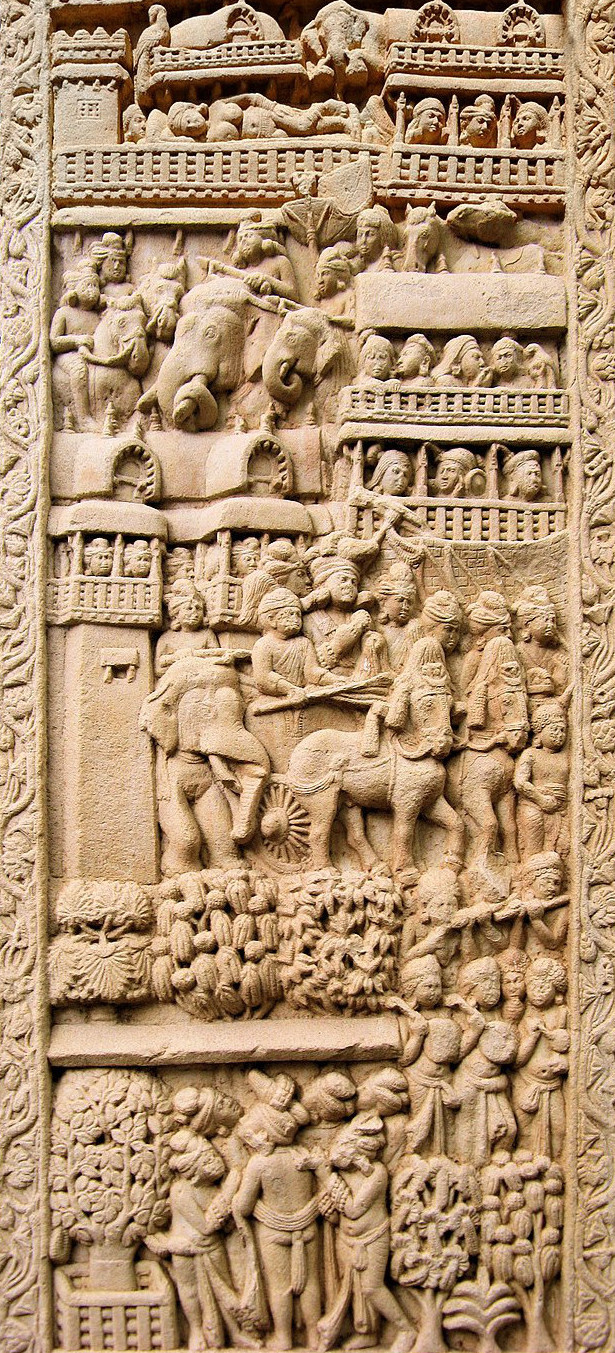

The Quest for Buddhism (10)

The family of Siddhartha (Buddha)

The Shakya (Skt: Sakya)

The Shakya (Skt: Sakya), to whom Gautama Siddhartha, the founder of Buddhism, belonged, were a tribe or nation in ancient northern India.

The Shakya were a clan of Iron age India (1st millennium BCE), inhabiting an area in Greater Magadha, situated at present-day southern Nepal and northern India, near the Himalaya. The Shakyas formed an independent oligarchic republican state known as Sakya Gaṇarajya. Its capital was Kapilavastu, which may have been located either in present-day Tilaurakot, Nepal or present-day Piprahwa, India. It was then under the rule of the Kosala state to the west.

Some scholars argue that the Shakya were Scythians from Central Asia or Iran, and that the name Sakya has the same origin as “Scythian”, called Sakas in India. Scythians were part of the Achaemenid army in the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley from the 6th century BCE. Indo-Scythians were also known to have appeared later in South Asia in the Middle Kingdom period, around the 2nd century BCE to the 4th century CE.

The Shakya afterwards:

According to Buddhist sources, the Shakya tribe was destroyed in the last years of the Buddha by a large army of the King, Virudhaka of the neighbouring state of Kosala.

仏教の探求 (10)

お釈迦さまの家族

釈迦族 (梵:シャーキヤ)

仏教の基礎となる教えを説いたガウタマ・シッダールタ(ブッダ)が属していた釈迦族(梵:シャーキヤ)とは、古代北インドの一部族・小国である。

釈迦族は鉄器時代のインドの氏族で、現在のネパール南部とインド北部、ヒマラヤに近い摩訶陀国(マガダ国)地域に居住していた。釈迦族は独立した寡頭制の共和制国家、シャーキア・ガナ・サンガ国を形成していた。その首都はカピラヴァストゥで、現在のネパール、ティラウラコットか現在のインド、ピプラワのどちらかに位置していた。そして西隣のコーサラ国の支配下にあった。

釈迦族は中央アジアやイランから来たスキタイ人であり、釈迦族の名はインドでサカと呼ばれる「スキタイ人」と同じ起源であると主張する学者もいる。スキタイ人は、前6世紀からのアケメネス朝によるインダス川流域の征服に際して、アケメネス朝軍の一員となった。インド・スキタイ人はその後、南アジアでも紀元前2世紀頃から紀元前4世紀頃の中王国時代に出現したことが知られている。

釈迦族のその後:

仏教文献等によると、釈迦族は釈迦の晩年の時期、隣国コーサラ国の毘瑠璃王(びるり・おう、梵: ヴィルーダカ)の大軍に攻められ滅亡したとされる。

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...“Scythia” was a fluid term in antiquity. For the Greeks, “Scythia” stood for an extensive cultural zone of a great many loosely connected nomadic and seminomadic ethnic and language groups that ranged over the great swath of territory extending from Thrace (another fluid geographic term in antiquity), the Black Sea, and northern Anatolia across the Caucasus Mountains to the Caspian Sea and eastward to Central and Inner Asia (it is more than four thousand miles from Thrace to the Great Wall of China).

“The Greeks call them Scythians,” wrote Herodotus; the Persians called them Saka (Chinese names included Xiongnu, Yuezhi, Xianbei, and Sai). “Although each people has a separate name of its own,” remarked the geographer Strabo, the Scythians, Massagetae, Saka, and other nomadic tribes “are given the general name of Scythians.” Pliny named twenty of the “countless tribes of Scythia.” As Gocha Tsetskhladze, a historian of Scythia, points out, “We call them Scythians because the Greeks did.” There are more restrictive modern descriptions for “Scythians” based on ethnographic, geographic, and linguistic parameters, but the terms Scythia and Scythians, the names used by the ancient Greeks, are convenient catchall terms to refer to the diverse yet culturally similar nomadic and seminomadic groups of Eurasia to western China.

Modern historians and archaeologists use “Scythian” to refer to the vast territory characterized in antiquity by the horse-centered nomad warrior lifestyle marked by similar warfare and weapons, artistic motifs, gender relations, burial practices, and other cultural features. Scythia’s forests, grassy steppes, desert oases, and mountains were home to a multitude of individual tribes with their own names, histories, customs, and dialects but sharing a migratory life centered on horses, archery, hunting, herding, trading, raiding, and guerrilla-style warfare. Endless journeys over waterless prairies, invasions, plunder, wars, alliances, agreements, quarrels, more wars: “such is the life of nomads,” commented Strabo.

Lucian of Samosata (Syria) concurred: “Scythians live in a state of perpetual warfare, now invading, now receding, now contending for pasturage or booty.” Going by myriad names, waxing and waning in population over the centuries, continually on the move, the Scythian nomads, as described in ancient texts, had a history “inseparable from that of the nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes of the Eurasian steppes.” Their common material culture, the “Scythian Triad” of distinctive weapons, horses, and artistic “animal-style” motifs, is evident in archaeological artifacts in burials from the Carpathian Mountains to northern China. Grave goods demonstrate far-reaching trade among these groups.

Not all of these peoples wandered the ocean of grass under infinite skies, however. By the fifth century BC, seminomadic clans known as the “Royal Scythians” had come to reside in wagons or settlements clustered around the northeastern Black Sea–Don area, taking up agriculture and trade, facilitating exchange between Greece and points along the Silk Routes to Asia. It was mainly through the coastal trading colonies that the Greeks first came to hear of the many different tribes of greater Scythia. No aspect of Scythian culture unsettled the Greeks more than the status of women. Hellenes expected strict division of male and female roles. But among nomadic people, girls and boys wore the same practical clothing and learned to ride and shoot together. In small hunting and raiding groups where everyone was a stakeholder and each was expected to contribute to survival in an unforgiving environment, this way of life made good sense.

It meant that a girl could challenge a boy in a race or archery contest, and a woman could ride her horse to hunt or care for herds alone, with other women, or with men. Women were as able as men to skirmish with enemies and defend their tribe from attackers. Self-sufficient women were valued and could achieve high status and renown. It is easy to see how these commonsense, routine features of nomad life could lead outsiders like the Greeks—who kept females dependent on males—to glamorize steppe women as mythic Amazons. The opportunity for an especially strong, ambitious woman to head women-only or mixed-sex raiding parties or even armies was exaggerated in Greek myths into a kind of war of the sexes, pitting powerful Amazon queens against great Greek heroes.

…Despite their rich culture (which flourished from the seventh century BC to about AD 500), the Saka-Scythians, Thracians, Sarmatians, and kindred groups left no written histories. What we know about them must be gleaned from other oral, written, or artistic materials, chiefly from Greece and Rome but also non-Greek sources from what is now Iran, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, India, China. The lifestyles of Eurasian nomads in later times can also contribute to our understanding of ancient life on the steppes.

Excavations of grave mounds (kurgans) began in the 1870s, and every year since then numerous archaeological teams are uncovering more and more evidence, much of it confirming ancient Greek reports and also revealing that Scythian culture was more sophisticated and complex than previously realized. By the seventh century BC, powerful Scythian forces were attacking, plundering, and exacting tribute in Thrace, the Caucasus, and Anatolia, penetrating south as far as Syria and Media, even advancing toward Egypt and moving eastward toward China.

The Scythians’ reach contracted again after defeats in the Near and Far East in the sixth century BC, but Scythians continued to dominate the Caucasus and Central Asian steppes. Scythians were horse people. They traveled extremely long distances by land, much of it harsh going. To reach Thrace or the mouth of the Danube or northern Greece, for example, they would follow a long southwestern arc down from the steppes. To reach Colchis, Armenia, Anatolia, and Persia from the north, they took one of two major migration routes used by nomads, traders, and invaders from time immemorial. These routes, first described by Herodotus, involved arduous journeys over or around the snow-clad Caucasus range. The Scythian Gates (or Keyhole) was a precipitous, winding mountain trail over the central Caucasus: the journey from the Sea of Azov to the Phasis River in Colchis took about thirty days. The ancient Persians called this narrow defile Dar-e Alan, “Gate of the Alans” (Daryal Pass), after one of the nomadic tribes of Scythia.

The other difficult and longer passage, sometimes called the “Caspian Gates” or the Marpesian Rock, was between the steep eastern end of the mountains and the Caspian Sea (Persian, Darband, “Closed Gates,” modern Derbent, Dagestan). From Pontus (northeastern Turkey) Scythians could cross west into Europe (Thrace) in wintertime over the frozen Bosporus Strait between the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara. In about 1000–700 BC, Greeks began establishing colonies along the Aegean coast of Anatolia, where they became aware of local histories and legends about Amazons. Many towns in Anatolia claimed Amazons as their founders; grave mounds and other shrines were local landmarks linked with Amazons. By the eighth and seventh centuries BC, Greek adventurers began exploring the rim of the Black Sea, which they called the Euxine or simply Pontus (“the Sea”). At some later point “Pontus” came to specify the wedge of land between the Phasis River of Colchis and the Thermodon River of northeastern Anatolia.

By the sixth century, Greek colonies were sprinkled around the Black Sea, and by 450 BC more than a dozen Greek colonies were established on the northern Black Sea, from Tyras on the Dniester River to Gorgippia (ancient Sinda), south of the Taman Peninsula, and Tanais, a Scythian trading post at the mouth of the Don River on the Sea of Azov. Descriptions of barbarian societies of the north and east, many distinguished by a degree of gender role blurring unknown in Hellenic society, began to filter back to Greece as a few traders and travelers journeyed beyond the colonies on the Black Sea, venturing deeper into the lands of nomadic groups, on the steppes, the Caucasus Mountains, around the Caspian Sea, and eastward along the trade routes to the distant Altai Mountains, India, and China. As travelers pushed farther, the stories got stranger, but meanwhile the Royal Scythians who had settled near the Black Sea colonies were becoming more familiar to the Greeks.

Literary and archaeological evidence points to an uneasy relationship between Greeks and Scythians in the Black Sea region in the sixth and fifth centuries BC, followed by a period of lively trade and mutual integration in the fourth century BC. Many slaves in Athens came from Thracian and Scythian tribes, purchased at Black Sea emporiums such as Tanais on the Don (see chapter 6 on Thrace-Scythia links). Meanwhile Greek merchants and travelers carried out commerce and made marriage alliances with Scythian clans.

In the fifth century BC, Scythian soldiers and policemen were employed in Athens, but numerous vase paintings and inscriptions about Scythians and Thracians attest to Greek familiarity with their clothing, tattoos, and weapons by the midsixth century BC. Male archers and Amazons wearing Scythian-style costumes became favorite subjects on Athenian vases by 575 BC. Some archaic black-figure paintings (575–550 BC) show men fighting on the Amazons’ side against Greeks; scholars suggest that these could be either Scythians or Trojans.

Around 490 BC, the time of the Persian Wars, the popularity of male Scythian archers in art faded, perhaps because of their association with Persians (although Scythians were also enemies of the Persians). But female Scythian archers—“Amazons”—never lost their popular appeal in Greek vase paintings and other art forms. Archaeologists now know that “legends about Amazons are reflected in the grave goods of excavated Scythian tombs.” The accumulating evidence of female warriors buried with their weapons is leading classical scholars to acknowledge that some Greek beliefs about Amazons were influenced by women who shared the same activities as men in the nomadic cultures of Eurasia. But this “novel” insight from modern archaeology—that Amazons were Scythian women—was already obvious to the Greeks in classical times. Whatever psychological meanings the Amazon myths may have held in antiquity, a wealth of little studied literary evidence shows that Greco-Roman authors clearly associated the Amazons with historical, nomadic Scythians at an early date.

Greek writings about Amazons indicated several different Amazon “habitats” and zones of activity in Scythia. Some sources located Amazons in Thrace and western Anatolia; some placed them in Pontus on the southern shore of the Black Sea; still others put them in the northern Black Sea–Sea of Azov–Caucasus regions; and many writers mentioned more than one locale. Modern scholars have taken this apparent inconsistency as proof that the Greeks were simply making up ecological niches for imaginary beings.

In fact, however, this mobile “sphere of influence” for Amazons makes sense. Whether or not the ancient mythographers and historians realized it, the depiction of shifting environments around the Black Sea for the Amazons’ home bases, strongholds, migrations, and battle campaigns accurately captured the realities of nomadic life. There is no doubt that at various times in historical antiquity groups of Scythians were present in the various regions designated in classical texts as occupied by Amazons .

In Homer’s Iliad, for example, King Priam of Troy recalls seeing Amazons in northern Anatolia as a youth. At the beginning of the war with the Greeks, Priam musters his army at a man-made mound near Troy said to be the grave of the Amazon queen Myrina. Mound tumuli are scattered across Phrygia, Mysia, and Thrace, and Scythian tomb mounds (kurgans) of the seventh–sixth centuries BC exist near Sinope, Pontus. Priam’s ally Queen Penthesilea was a Thracian, but she led a band of Amazons from Pontus. The mythic quest of Jason and Argonauts for the Golden Fleece is at least as ancient in its origins as the Trojan War cycle. According to the Argonautica (the version of the myth composed by Apollonius of Rhodes, ca. 280 BC), Pontus and Colchis were occupied by three different tribes famed for women warriors (chapter 10).

In the mid-seventh century BC, the adventurer Aristeas (from an island in the Sea of Marmara) wrote about his journey east across Scythia to Issedonia and the Altai Mountains. His epic, Arimaspea (a Scythian word meaning something like “people rich in horses”), preserved only in fragments, was very influential in forming the early Greek picture of Scythia and Amazons. Aristeas said that Amazons wandered the ironrich territory around the Maeotis (Sea of Azov) and the River Tanais (Don).

Another lost work, by Skylax of Caryanda (sixth century BC), described the Maeotians, the Sinti (Sinds), and the Sarmatians as “people ruled by women.” Several authors referred to Amazons as Maeotides, “people of the Maeotis.” (Scythian tribes around the Sea of Azov included the Sinds, Dandarii, Doschi, Ixomatae, and many others.) Other ancient historians placed Amazons and their allied forces among the nomads beyond the Borysthenes (Dnieper) River on the steppes north of the Black Sea.

Pontus was the Amazon headquarters in another lost epic, the Theseis, about the Athenian hero Theseus, probably composed in the sixth century BC. In the fifth century BC the playwright Euripides located the Amazons in Pontus; so did the poet Pindar, who described Amazons “armed with spears with broad iron points.” The play Prometheus Bound (Aeschylus, ca. 480 BC) speaks of the “fearless maidens” of Colchis and the Caucasus and the “Scythian multitudes” to the north; it foretells that this Amazon host will “one day settle at Themiscyra by the Thermodon” in Pontus.

The fourth-century BC Greek historian Ephorus (from Cyme, named for an Amazon) reported that a faction of Scythians had once left the northern Black Sea and settled in Pontus, becoming the Amazons. The geographer Strabo (first century BC) located various Amazon tribes in the valleys and mountains of Pontus, Colchis, the Don region, and the Caucasus. Instead of evidence for Greek confusion about where to locate imaginary Amazons, these examples represented Amazons as people who roved around the Black Sea. Scythian culture was consistently recognized as the wellspring of the women warriors known as Amazons.”

- Adrienne Mayor, “Scythia, Amazon Homeland.” in The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post Mauryan Foreign And Indegenious Invasion

In this section, we will learn about the various foreign rulers that attacked India.

Many foreigners came to India during this period and settle down in India. These foreigners are:

Indo-Greeks

Sakas/Scythians

Parthians

Kushanas

In some parts of India there were indigenous kingdoms, these were:

Sungas

Kanvas

Satavahanas

Indo-Greek Rulers

They were the rulers of “Bactria”, a place in Afghanistan. Indo-Greeks were originally called Bactrian Greeks.

Most important Indo-Greek ruler was:

Menander also known as Milinda. Prior to Menander, there was another king called, Demetrius who issued gold coins.

He was a Buddhist king.

They introduced the System of Curtains in drama.

Old name of curtain: Yavanika.

Sakas/Scythians

Original Homeland of Sakas: Central Asia.

Reason for migration of Sakas towards India:

“Yu-Chi” tribe in N-W China, lived between Central Asia and N-W China.

People of this tribe kept entering into China in search of fodder.

To stop the incursion of these people, Chinese king ordered to build a wall – the ‘Great wall of China’.

After the construction of wall, Yu-Chi tribe moved to Central Asia and displaced Sakas.

Sakas then crossed Hindukush mountain and entered India.

Founder of Sakas/Scythians rule: Moga/Maues (First ruler).

Most important of Saka kings was: Rudradaman I.

Rudradaman I

Rudradaman was the gradson of Chastana, the founder of Kshatrapas dynasty.

He was instrumental in the decline of the Satavahana empire.

He also conquered the Yaudheya tribes of Haryana.

He took the title of Maha-kshtrapa (Great Satrap).

The Sanskrit Junagadh Inscription dated 150 CE credits Rudradaman for supporting the cultural arts and Sanskrit literature and repairing the dam built by the Mauryans.

It was the first inscription in ‘Sanskrit’ language in India.

The script used was -> Sharda script which later developed into ‘Devnagiri’.

Parthians

Their original homeland: ‘Persia’.

Most important Parthian ruler was ‘Gondophernes’

During Gondophernes time, for the first time, a new religion came to India – ‘Christianity’.

Christianity was introduced by ‘St. Thomas’

St. Thomas came to India from Palestine.

Kushanas (Old Name: Yu-Chi)

The Kushans were one of the five clans into which the Yu-Chi tribe was divided.

We came across 2 successive dynasties of the Kushanas.

First dynasty was founded by a House-of-Chiefs who were called ‘Khadphises, and ruled for 28 years from about 50 AD. It had 2 kings, namely:

Kujula Khadphises I

Vima Khadphises II

Khadphises I: Issued coins south of Hindukush. He minted the coins as imitation of Roman coins,

Khadphises II: he issued a large number of gold coins and spread his kingdom in east of the India.

House of Khadphises was succeeded by that of Kanishka.

Second Dynasty was founded by Kanishka (78 AD).

Kanishka became ruler in 78 A.D., to mark his coronation, he started a new calendar “Saka Era”.

Kanishka is known to history for two reasons:

He started an era in AD 78 (Saka Era) and is still used by the Government of India.

His whole-hearted patronage to Buddhism.

📷 Read here --> Post-Maurayan Art and Architecture

Impact Of The Foreign Rule

Foreign rulers made a large impact on India, some of which are given below:

Better Cavalry

Sakas and Kushans introduced better cavalry and the use of the horse-riding on large scale.

They made common the use of – Reins and Saddles.

They introduced: Turban, Tunic, Trousers and Heavy-Long coat.

Sherwani is a successor of the long coat.

The Central Asian also brought in – Cap, Helmet and Boots, which were used by the warriors.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Drinking Habits of the Barbarians

Mead Hall by Norm Newberry

We’ve heard it before: barbarians had drinking problems. Unable to comprehend moderation and incapable of limitation, uncivilized barbarians drowned themselves in alcohol constantly. Their violent tempers were partially a result of their alcoholism, partly by their very nature. Greco-Romans crafted these stories with every barbarian civilization they encountered, but not all of it is mere slander. Like every civilization, barbarians too had customs and sometimes excess when it came to drinking culture. Here is a general overview.

The Scythians

The Scythians were a broad-ranging people, with many strange customs among them as attested by several ancient sources. One group of Scythians was called by the Persians “haoma-drinking Saka” (Saka, the Persian name for them). Haoma was a very-potent drink made by pressing the sacred plant of the same name. Apparently, this was equivalent to drinking uncut Greek wine. Herodotus writes that it was Scythian custom to drink with the king and only successful warriors could partake, making it a great shame if one didn’t kill an enemy. The best of the best drank with two cups at once. (They also supposedly drank their potent wine out of the skulls of enemies, and they also drank their enemies’ blood, although I’ve seen no evidence of this last one’s validity.)

While Scythian drinking habits have yet to be validated with strong archaeological evidence, they were no strangers to other substances. Scythians also hotboxed with cannabis and opium in their rituals, which has been substantiated by residue tests on Scythian vessels uncovered in Southern Russia. So if Herodotus’ claim that they liked to take drug steam-baths is true, maybe their excessively strong drinking habits are also authentic.

The Huns

Other elements of Scythian drinking culture are possibly shown through the Huns, or at least as who Priscus attributes them to. (The Huns were, after all, thought to be descendants of the ruling Scythians, though this opinion is likely false. There was a lot of cross-pollination of cultures going on in Central Asia among the different nomad peoples, though.) Huns in Europe typically drank mead, probably as a result of their exposure to the Germanic tribes, but wine was the drink of the upper class. Drinking in Hunnic culture was strongly connected to hospitality and revelry.

Priscus records that the Hunnic women brought food and drink on platters as an offering to important guests, which was “a very great honor amongst the Scythians”. Three times during Attila’s feast the Huns toasted and drank their entire cups of wine (Though Priscus did specify that it was optional to do so), and at the beginning of the feast Attila passed around a goblet for all of his warriors to drink from. The Huns left virtually no artifacts to attest to this (and left virtually no artifacts in general), so we have to rely on Priscus’ accountability.

The Celts

According to several ancient sources, the Celts are also not shy about drinking uncut wine and stumbling around drunk all the time. While this view of perpetual drunkenness is a little ridiculous, let’s talk about what isn’t. The Celts, like most Northern European cultures, primarily drank beer and mead (made with barley, with or without honey) and occasionally wine, which they had to import from the Mediterranean. (This is the alcohol that Diodorus claims that Celts cannot help themselves but to get incredibly intoxicated on). Mead seems to be more important culturally, though, as attested to the Celtic afterlife featuring a river of it. The Celts were apparently “transformed” into having good drinking habits thanks to their Romanization.

What physical evidence we do have of Celtic drinking culture are a few massive cauldrons/vessels which undoubtedly (through chemical analysis) contained honey mead, like one uncovered in Hochdorf, Germany in the Hallstatt period. Either these were merely carrying vessels for transport (though, a ~105-130 gallon, 400-500 liter metal cauldron would be impossibly heavy) or they were meant to be punch bowls at Celtic banquets. The scale of these vessels gives the impression that either these banquets had many guests or the Celts drank a lot at once.

The Germanics

The Germans were, meanwhile, not as tempered by Roman drinking ethics. Germanic tribes drank the same things that the Celts did, as a consequence of Northern Europe’s unfavorable climate for producing anything other than beer. The Norse god Odin drank mead as a source of power. I’d be remiss to not talk about Germanic banquets, too. Tacitus writes: “no other nation abandons itself more completely to banqueting and entertainment.” Tacitus continues on to describe the fantastic German hospitality. Germanic banquets held in “mead halls” are attested in later works of Germanic epic poetry like Beowulf as integral aspects to Germanic culture.

Germanic kingship (for most of the tribes) relied on how large and powerful of a following an individual king had, called a retinue. Banquets were an easy incentive and a way to reward further loyalty from the king’s men. Meanwhile, the other most-ubiquitous aspect of Germanic drinking culture is the drinking horn, which also appears in later Viking motifs. The drinking horn, however, is not uniquely German, though many Germanic artifacts of this type have been uncovered. Scythians, Thracians, Celts, and probably more barbarian cultures also utilized drinking horns. Their styles vary greatly, with the Germanic ones being largely made of glass.

#barbarians#the germanics#the celts#the huns#the scythians#germanic culture#celtic culture#hunnic culture#scythian culture#culture

18 notes

·

View notes

Link

The early nomads of Eurasia, whom ancient writers called Scythians and Sakas, occupied the great Eurasian Steppe from the beginning of the first millennium BCE. The Scythian culture is well known from the excavations of numerous rich, elite barrows north of the Black Sea, but their theatre of action actually stretched from Hungary to the Great Wai! of China. In the steppe zone of Central Asia a number of cultures of the Scythian-Saka type appeared at this period, tor example, the Aidy-Bel’, Maiemir, Tasmola and Tagar cultures. The Tagar culture, which succeeded the Karasuk culture in southern Siberia (Legrand, above) belongs to the earliest stages of the Scythian group, and is dated to the ninth-eighth century BCE (Sementsov et al. 1998; Vasiliev et al. 2002; Bokovenko et al. 2002).

This paper studies the sequence of the Tagar culture in the Minusinsk basin in southern Siberia. It is a sequence which shows how mobile horsemen emerged from their Bronze Age background to dominate their region and spread their culture many thousands of miles westwards into Europe.

Bokovenko, Nikolay. “The emergence of the Tagar culture.” Institute for the History of Material Culture, Russian Academy of Sciences, Dvortsovaya nab., 18 191186, Saint-Petersburg, Russia.

Even today the Tagar burial grounds are quite visible because of the presence of vertical stone slabs around the kerb forming the enclosures or mounds. Graves in the earliest dared cemeteries are not numerous, but, by contrast, cemeteries belonging to the subsequent period contain hundreds of mounds and diverse burial monuments. A characteristic feature of the Tagar burial tradition, as in the Karasuk culture that preceded it, is that the dead were buried in square or rectangular enclosures made of vertically standing stone slabs, covered with a pyramidal burial mound. Occasionally the stones were arranged in horizontal rows with vertical stones set at the corners of enclosures and along their perimeters.

A general trend in the Tagar burial tradition was that the enclosures and the graves they contained increased in size and depth over time (Figure 4). The stone cists were gradually replaced with timber frames that had strong multi-layered floors. The number of bodies buried in each stone cist also increases through time, in the early period the dead were buried in a supine position with their heads consistently oriented to the south-west, and only occasionally to the north-east. In the case of the collective graves, the orientation varied.

In the Biiinov phase the burial enclosure i.s small, still based on the Karasuk pattern which walls up to 1m high constructed of stone slabs, and sometimes with taller slabs 1 to 2m high at the corners (Figure 5). Each enclosure contains one tomb, also built from slabs of stone, and each tomb contains a single skeleton. As in the earlier period, one or two vessels were placed at the head of the deceased person and the same four pieces of meat {from sheep rather than oxen) were laid at the feet. In the male graves, one or two vessels with liquid were usually set at the head and some pieces of beef or more rarely mutton or horse meat were left at the feet. ln a male burial, a dagger and a battle-axe were usually placed adjacent to the body, a knife on the left side of the belt, and a quiver with arrows placed at the feet {Chlcnova 1967: Table 1). A knife or a small bag with toilet articles including a mirror and a comb were attached to women’s belts. Women’s clothes were decorated with numerous beads and pendants. Complex sets of beads decorated the clothing; headdresses adorn the hair of the deceased.

In the Podgornovo phase, the burial enclosures continue to be small and are frequently attached to each other (Figure 6). They contain 1-2 tombs in the centre. The tomb itself is often a timber chamber rather than a stone cist. Multiple tombs contained two to three deceased, but single burials are more common. From that time on in the Tagar culture, numbers of bodies were successively buried in a tomb, and entrances provided for the purpose.

The material culture of the Tagar Period is extremely varied with thousands of bronze artifacts of very fine quality placed in the burials. These artifacts testify to a highly developed bronze-casting industry stemming from very okl traditions. Weapons are represented by three main categories: daggers, batrle-axes and arrowheads (Figure 10). Daggers may have guards at right angles to the blade and roller-shaped handles, or butterfly-shaped guards and pommels in a variety of forms such as roller-shaped, ring-shaped, or zoomorphic. By the end of the Tagar Culture the form of the guards had degenerated. The earliest battle-axes have a head, are round in section, and contain a polyhedral or mushroom-shaped butt on a long sleeve. Later, the sleeve became shorter and the butt was often made in the form of an animal figurine such as a goat or a stag. Sometimes the sleeves were decorated with a rather fine depiction of an animal (Chlenova 1967: Table 8: 10-11; Bokovenko 1995: 304). The earliest arrowheads have two points on a hollow shaft, often with a tenon. The later arrowheads, dating to the sixth-fourth centuries BCE, are tetrahedral or trilobed, and stemmed. Variations in form are achieved through modifying the shape of the fins and the impact point of the arrowhead. The classification of arrowheads has been elaborated in much detail (Chlenova 1967: Table 12: 12). Bone arrowheads are trilobed or tetrahedral and occasionally bullet-shaped but generally of the simpler standard forms that were already well developed during the Neolithic and the Bronze Age.

Utilitarian implements are numerous and versatile. The blades of practically all Tagar knives are the same, and the differences are manifest mainly in the shape of their handles. The handles may be ring-shaped, with an arch, with small or large holes, openwork, loopshaped, insert-type. They have zoomorphic forms and can be decorated with various incised motifs {Bokovenko 1995: 306, 313). Artifacts related to the bronze casting industry are represented mainly by bi-valve stone and clay moulds (Grjaznov 1969). Numerous devices such as clamps, nozzles, and pouring gates used in casting as well as technologically complex and highly artistic bronze artifacts such as bridles, cauldrons and art works indicate a highly specialised and developed bronze industry.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashoka: Satrap of Taxila

Ashoka: Satrap of Taxila by Ashok K. Banker (Westland Publications, 2017). The K. stands for Kumar. I don’t know if Ashok K. Banker goes to the White Castle. I had read somewhere that Ashok Banker said that he liked Robert E. Howard. I remember seeing the Ramayana books published by Aspect/Warner in 2004. I thought I would give him a try. Ashoka is historical fiction, not fantasy. He admits this is a fictionalized account of the life of the Indian emperor, Ashoka the Great. The Mauryan Empire (320- 180 B.C.) was the biggest in India until the British took over the subcontinent. I find Indian history of interest. The north had periodic invasions of Aryans, Sakas, Parthians, Kushans, Turks, and finally the Mughals under Babur. Northern India is tied with Central Asia periodically. The south is tropical with the spices for the cuisine and architecture influencing South East Asia and the East Indies.

Banker plays a little free with history. His main villain is Seleucus Nicator (d. 281 B.C), one of Alexander the Great’s generals who became one of the “Successors.” Seleucus is conspiring to conquer India for the wealth so he can turn west and overwhelm the other Successors. Seleucus ceded territory to Chandragupta, Ashoka’s grandfather and founder of the Mauryan empire for a bunch of war elephants. Chandragupta had an army with Scythians, Parthians, and Greeks in addition to Indians. His territory extended to include what is now Afghanistan. Young Ashoka is sent to quell a revolt in Taxila which is now north-west Pakistan, Osama bin-Laden territory. There is a lot of harem intrigue with a Khorasani princess looking to eliminate Ashoka. Historical mistake: Khorasan did not exist as a name until the Sassanid Persians in the 3rd Century A.D. At this time, it would have been known as Hyrcania. That would have been a great name to use. There is not much action. I was disappointed in there was little description of the weapons used or the armor worn. Part of a chapter was given over to a very awkwardly written sex scene of a threesome of the Emperor Bindusara, the Khorasani princess, and her maid. Andrew Offutt, we need you now! The book ends with some Afghans taking Ashoka prisoner and breaking the bones in his body. The novel just ends. I realize this is the middle of a trilogy or part of a series, but books should be self-contained in narrative. What strikes me as odd is the book is almost marketed as a young adult novel while the contents are most decidedly not.

Banker is from Bombay and has some Irish and Portuguese in the mix. I am not quite sure on the target audience. The books are written English, which as a friend of mine pointed out is the lingua franca of the Subcontinent. The Ramayana was abandoned by Warner after two out of seven books in the series. He might be looking to break out in the U.S. with perseverance. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt did publish his Upon a Burning Throne in hardback last year and paperback this year. Looking at the Amazon preview, The Burnt Empire appears to be a jump from adapting Indian history and mythology to his own world building. I will probably get around to reading more Ashok K. Banker in the future. His prose style is easy enough and the scenery is a change of pace.

Ashoka: Satrap of Taxila published first on https://sixchexus.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

Elephants on Indian coins: An overview and history – Part II

Elephants play a very important role in many cultures and traditions. But we do not have to go deep into the “cultural” and “religious” significance of these majestic animals to understand why they are such a hit with the public! Just type ‘elephant’ in your Google search and you will find so many adorable videos and images of elephants. Right from the “Manny” of Ice Age (although Manny is a mammoth) to “Snorky” of the Banana Splits Club, our cartoons, movies and Facebook walls are full of cute elephants. Today we find elephants all over the social media, but in the ancient and the medieval times, they adorned various paintings, sculptures and coins! Let’s continue our journey of exploring elephants on Indian coins.

In the previous part – Elephants in Indian Coinage Part I – we have seen the importance of elephants in Indian culture and traced the history of elephants on Indian coins since their appearance on Indus Valley Seals. Today let’s take it further.

The tribal states of India also called as the Janapadas[1], form a very intriguing part of Ancient Indian history. The Punch Marked Coinage of these various Janapadas, Mahajanapadas and later the Imperial Mauryas, had a wide spectrum of symbols punched on them. And this mighty elephant is a recurring motif on most.

A) Vemaki: An ancient India tribal nation of north India, the Janapada of Vemaki finds mentions in Mahabharata and Brihatsamhita. Coins of this tribal state are generally identified into four distinct series, out of which two are classified according to motifs found on them[2]. Needless to say, elephants are a recurring symbol on them.

This silver drachm coin weighing 2.28 grams is of King Mahadeva who reigned approximately in 200 BCE. The obverse depicts a humped bull facing right, with a dotted wheel in front and legend in Kharosthi ‘Bhagavata Mahadevasa Rajaraja’ around. The reverse has an elephant facing left with a trident in front and Brahmi legend ‘Bhagavata Mahadevasa Rajaraja’.

B) Vrishni: Vrishni, popularly believed to be the clan of Lord Krishna, was a tribal state in ancient India. The Puranas claim Vrishni to be located near Dwarka and its people to be descendants of Yadu. Panini’s Ashtadhayi, Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Vyas’s Mahabharata all mention Vrishni Janapada.

A silver coin of Raja Vrishni found in Hoshiarpur, Punjab by Alexander Cunningham has on it’s an obverse a mythical creature (half lion and half elephant) within a railing with a circular Brahmi legend ‘Vrishniraja Jnaganasya tratarasya’ and a twelve spoked chakra in pellet border with slightly truncated Kharoshthi legend ‘Vrishniirajanna(ganasa) tra(tarasa)’ on the reverse. Later few copper coins were also attributed to this janapada.

C) Western Kshatrapas: Considering the popularity of the animal, it will be surprising not to find elephants on Western Kshatrapa coins. A dynasty that probably had Scythian origins, Western Kshatrapa was a major ruling dynasty for over 200 years in western India. This dynasty is also known for their remarkable consistency in coinage.

A potin coin from Damasena’s ruling period has Elephant standing right, sun and moon above on its obverse and on the reverse a chaitya (3-arched hill), the river below, crescent moon and sun above, with a date 153 (Saka era) below.

Elephants are almost synonymous with India and you just cannot imagine South India without them! A trip down south will be absolutely incomplete without going on elephant safaris and nature camps. So obviously this majestic animal was an integral part of South Indian coinage too.

And while talking about the South we cannot miss out on the strong empires of the Chola, Cheras and Pandyas which were the three longest ruling dynasties of South India, each of which flourished during the Sangam age and achieved awe striking developments in literature, art and architecture. These mighty empires (Cholas in particular) find a mention in the 3rd century BCE inscriptions of Mauryan king Ashoka.

They were powerful dynasties from the Tamil Sangam ages who continued their rule from ancient till the medieval 13th century CE. Many lustrous kings graced this land and extended their rule beyond the Indian Ocean. Their coinages are rich in design, metal varieties and innovations and as always elephants have played a very vital role in them. Let’s have a look:

A) Chola: Depicted here is a Sangam Age Chola copper coin. This square 2.56 grams coin features an elephant standing facing right on its obverse. The reverse depicts tiger standing facing left with an upraised paw.

B) Chera: This Chera copper of 6.9 grams has an elephant walking to the right in the front of six arched hill, bow with arrow, snake and battle axe depicted on its obverse and the Chera dynasty symbol of the bow and arrow on the reverse.

C) Pandya: Depicted here is a 2.5 gram copper coin of yet another jewel of South India, the Pandyas. Being in circulation from 1st – 2nd century CE, the obverse of the coin depicts an elephant facing left and the Pandya fish emblem (fish swimming below a flowing river) on its reverse.

Finding really good specimens of Sangam Age coins is rare but whatever their condition they have played a very important role in providing source studies for the ancient Tamil history. Especially the ones minted by the Tamil Kings are direct pieces of evidence of the Tamil polity during the Sangam age. Interestingly elephants became rarer in the coins minted during the medieval times of these dynasties.

But the journey of the elephants on Indian coins does not end here. They continued to be portrayed in the coinages of various dynasties of the South in ancient and medieval eras as well.

Depicted here is the Badami Chalukya coin (A) of King Jayashray Mangalarasa who reigned during 596 – 610 CE. The Chalukyas of Badami ruled in the north Maharashtra & South Gujarat regions. This copper coin has on its obverse an elephant facing right and on its reverse has a sun depicted above a Brahmi legends ‘Sri Jayashray’ in the centre with an inverted crescent below.

Yet another branch of the Chalukyas, popularly known as the Solanki Chalukyas of Gujarat or the Later Chalukyas, too has an elephant on their coins. This silver masha coin (B) weighing 0.38 gram is of King Siddharaja Jayasimha. The obverse of the coin depicts an elephant walking to right with a long trunk touching the ground while the reverse had an early Nagari legend which reads “Jaya Si / Piya [Srimaj Jayasimha Priya]” or “Srima Jayasimha/Priya”.

The Kalachuris of Ratnapura, a dynasty that ruled parts of modern day Chhattisgarh during 11th and 12th centuries CE, had on their coins a unique depiction of elephants. The Kalachuri rulers of Ratnapura issued gold, silver and copper coins, which bear the issuer’s name in Nagari script. Out of the basic four designs, the most famous is the “Gaja Shardula”[3] type coins.

The 41/2 Mashas gold coin of King Jajjala Deva II depicted here (C) features a Gaja-shradula (a tiger mounted on an elephant) on its obverse within dotted border while the reverse of this 3.8-gram coin depicts legend is Devanagari script in two lines ” Shri mat pri/ thvi deva”.

Some of the most ornamental depiction of this majestic animal is seen on the coins of the Western Gangas. They were an important ruling dynasty of ancient Karnataka. This gold pagoda (A) of 3.74 grams has a caparisoned elephant to right chewing sugarcane, with Kannada letters ‘Vala’ above the elephant’s back. The reverse depicts a scrollwork. Elephants were never depicted so beautifully in any coinages as those in the Western Gangas, don’t you agree?

The mighty dynasty of the South, the Rashtrakutas need to introduction. They ruled over large parts of the Indian subcontinent between the 6th and 10th centuries CE. Even if their origins are obscured, the latter part of their history is much celebrated. They are famous for the tripartite struggle for the resources of the rich Gangetic plains with the Palas of Bengal and the Pratiharas of Malwa.

Their rich coinage has elephants, a mark of absolute might and power, depicted on them. A silver 0.46 grams drama coin (B) has on its obverse an elephant walking towards right mounted by a human figure (maybe king/mahout), a chakra/wheel with a dot in the centre, dotted border around. The reverse proudly boasts a seated goddess in Padmasana posture with hair bun & halo around with long ears, traces of Brahmi legends around.

Some coins of Hoysala and Kakatiya dynasties too have elephants depicted on them.

The mighty and the lustrous Vijayanagara Empire who procured architectural gems (Hampi) are no less when it comes to their coinage. They too have depicted elephants on their coins. Known for their complex currency systems, their currency structure was followed by their many feudatories too. Depicted here is one such Vijayanagar – Feudatory Issue copper coin (A) of king Devaraya II who reigned from 1425 to 1446 CE. The coin’s obverse depicts an elephant facing right within a circular frame with dotted outer decoration with letter ‘LA’ above the elephant. The reverse had a two-line Telugu Legend: KHA NA / DA NA YA / KA RU – Dhandanayaka[4].

The ‘Tiger of Mysore’ Tipu Sultan of the Kingdom of Mysore was a legendary ruler who not only opposed British rule in South India but also played a major role in keeping the British forces away from South India. He was known for introducing innovative administrative schemes and military technology.

This Othmani / Double Paisa depicted here (C) is a copper coin minted in 1218 Malgudi year. The Coin depicts on its obverse an elephant facing right with an uplifted trunk; flag above the elephant; date 1218 written on the tail which is all within a double lined circle, with a row of dots in the middle. The reverse has a Persian inscription “Othmani Pattan Zarb Darul Sultanat”.

The legacy of depicting elephants continued in the modern era too with the Princely State of Travancore issuing coins with elephants. This copper Thira Kashu / Kasu or Cash (B) of Maharaja Karthika Thirunal Rama Varma of the Royal Family of Travancore was issued in 1797 CE. Depicted on the obverse is a man/warrior or a mahout holding Ankush, riding an elephant with huge tusks marching left within circular border decorated with dots. The reverse a blossomed lotus flower within circular border decorated with dots.

Considered as symbols of good luck and fortune, elephants have played a major role in Indian religious ceremonies, social functions and popular arts. A representation of wisdom, loyalty, strength, honour, stability and persistence, the elephant has for long exerted a powerful hold over the human imagination and Indian numismatic art is no exception.

Making an all-inclusive list of dynasties and kings who issued coins with elephants on them will in itself be a mammoth task. But we are sure you would have enjoyed this brief journey of discovering elephants on Indian coins with us.

Do you have any coins that you would add to this list? Comment away…let’s hear from you!

[1] Mentioned as groups of wandering “janas” (people) in Rigveda, Sutras and various Buddhist and Jain epigraphs.

[2] Geography from Ancient Indian Coins & Seals By Parmanand Gupta, pgs. 51-53

[3] Gaja-shardula design depicts a fight between a tiger and an elephant. This design occurs on all Kalachuri of Ratnapura dynasty’s gold coins, and on some of their copper coins too.

[4] In the name Of Naganna Dannayaka Viceroy of Mulbagal. Issue: Lakhana Dandanayaka. The name Dandanayaka means a leader for a military group i.e a commander/captain. He was appointed by King Devaraya to carry out his military exploits to Ceylon.

Share

The post Elephants on Indian coins: An overview and history – Part II appeared first on Blog | Mintage World.

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on

Magadha owed its enlargement

We’ve got seen how Magadha owed its enlargement to sure primary materials benefits As soon as the information of the usage of these components of tradition unfold to central India, the Deccan and Kalinga because of the enlargement of the Magadhan empire, thp Gangetic basin which fashioned the guts of the empire misplaced its particular benefit The common use of iron instruments and weapons within the peripheral provinces coincided with the decline and fall of the Maurya empire. On the’foundation of fabric tradition acquired from Magadha new kingdoms may very well be based and developed. This explains the rise of the Sungas and,Kanvas in central India, of the Chetis in

Kalinga and that of the Satavahanas within the Deccan

Neglect of the North-West Frontier and the Nice Wall of China

Since Asoka was largely preoccupied with missionary actions at residence and overseas, he couldn’t take note of the safeguarding of the passage on the north-western frontier. This had turn out to be needed in view of the motion of tribes in Central Asia within the third century B.C. The Scythians have been in a state of fixed flux. A nomadic folks primarily counting on the usage of horse, they posed critical risks to the settled empires in China and India. The Chinese language ruler Shih Huang Ti (247-210 B.C) constructed the Nice Wall of China in about 220 B C. to defend his empire agamst.the assaults of the Scythians. No related measures have been taken by Asoka. Naturally when the Scythians made a push in the direction of India they compelled the Parthians, the Sakas and the Greeks to maneuver in the direction of India. The Greeks had arrange a kingdom in north Afghanistan which was referred to as Bactria. They have been the primary to invade India in 206 B.C This was adopted by a collection of invasions which continued until the start of the Christian period

The Maurya empire was lastly destroyed by Pushyamitra Sunga in 185 B.C. Though a brahmana he was a basic of the final Maurya king referred to as Brihadratha. He’s stated to have killed Brihadratha in public and forcibly usurped the throne of Patalipufra. The Sungas dominated in Patahputra and central India, and so they carried out a number of Vedic sacrifices m order to mark the revival of the brahmamcal lifestyle. It’s stated that they persecuted the Buddhists They have been succeeded by the Kanvas who have been additionally brahmanas.

Central Asian Contacts and Their Outcomes

The interval which started in about 200 B.C didn’t witness a big empire like that of the Mauryas, however it’s notable for intimate and widespread contacts between Central Asia and India In japanese India, central India and the Deccan the Mauryas have been succeeded by quite a lot of native rulers such because the Sungas, the Kativas and the Satavahanas In north-western India they have been succeeded by quite a lot of ruling dynasties from Central Asia

Usually, I plan my holidays out of my nation however within the final years I’m critically considering of making an attempt holidays to Bulgaria.

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on

Magadha owed its enlargement

We’ve got seen how Magadha owed its enlargement to sure primary materials benefits As soon as the information of the usage of these components of tradition unfold to central India, the Deccan and Kalinga because of the enlargement of the Magadhan empire, thp Gangetic basin which fashioned the guts of the empire misplaced its particular benefit The common use of iron instruments and weapons within the peripheral provinces coincided with the decline and fall of the Maurya empire. On the’foundation of fabric tradition acquired from Magadha new kingdoms may very well be based and developed. This explains the rise of the Sungas and,Kanvas in central India, of the Chetis in

Kalinga and that of the Satavahanas within the Deccan

Neglect of the North-West Frontier and the Nice Wall of China

Since Asoka was largely preoccupied with missionary actions at residence and overseas, he couldn’t take note of the safeguarding of the passage on the north-western frontier. This had turn out to be needed in view of the motion of tribes in Central Asia within the third century B.C. The Scythians have been in a state of fixed flux. A nomadic folks primarily counting on the usage of horse, they posed critical risks to the settled empires in China and India. The Chinese language ruler Shih Huang Ti (247-210 B.C) constructed the Nice Wall of China in about 220 B C. to defend his empire agamst.the assaults of the Scythians. No related measures have been taken by Asoka. Naturally when the Scythians made a push in the direction of India they compelled the Parthians, the Sakas and the Greeks to maneuver in the direction of India. The Greeks had arrange a kingdom in north Afghanistan which was referred to as Bactria. They have been the primary to invade India in 206 B.C This was adopted by a collection of invasions which continued until the start of the Christian period

The Maurya empire was lastly destroyed by Pushyamitra Sunga in 185 B.C. Though a brahmana he was a basic of the final Maurya king referred to as Brihadratha. He’s stated to have killed Brihadratha in public and forcibly usurped the throne of Patalipufra. The Sungas dominated in Patahputra and central India, and so they carried out a number of Vedic sacrifices m order to mark the revival of the brahmamcal lifestyle. It’s stated that they persecuted the Buddhists They have been succeeded by the Kanvas who have been additionally brahmanas.

Central Asian Contacts and Their Outcomes

The interval which started in about 200 B.C didn’t witness a big empire like that of the Mauryas, however it’s notable for intimate and widespread contacts between Central Asia and India In japanese India, central India and the Deccan the Mauryas have been succeeded by quite a lot of native rulers such because the Sungas, the Kativas and the Satavahanas In north-western India they have been succeeded by quite a lot of ruling dynasties from Central Asia

Usually, I plan my holidays out of my nation however within the final years I’m critically considering of making an attempt holidays to Bulgaria.

0 notes

Text

“Мы пили Сому, Мы становились бессмертными…”

The «divine mushroom» embroidered on the carpet resembles well-known psychoactive species Psilocybe cubensis. The weight of evidence suggests that soma, the ancient ritual drink, has been prepared from the mushrooms of family Strophariaceae which contain the unique nervous system stimulator psilocybin

Inside a deep Xiongnu grave hidden in the thickly wooded Sudzuktè pass, on the bottom of the burial chamber, archaeologists, participants of the Russian-Mongolian expedition, found what they had long been searching for: a layer of clay revealing the outline of textile relics. The fragments of the textile found were parts of a carpet composed of several cloths of dark-red woolen fabric. The time-worn cloth found on the floor covered with blue clay of the Xiongnu burial chamber and brought back to life by restorers has a long and complicated story. It was made someplace in Syria or Palestine, embroidered, probably, in north-western India and found in Mongolia. Finding it two thousand years later is a pure chance; its amazingly good condition is almost a miracle. How it made its way to the grave of a person it was not meant for will long, if not forever, remain a mystery. Of greatest surprise though was the unique embroidery made from wool. Its pattern was the ancient Zoroastrian ceremony, of which the principal personage was …a mushroom. In the center of the composition to the left of the altar is the king (priest), who is holding a mushroom over the fire. The «divine mushroom» embroidered on the carpet resembles well-known psychoactive species Psilocybe cubensis. The weight of evidence suggests that soma, the ancient ritual drink, has been prepared from the mushrooms of family Strophariaceae which contain the unique nervous system stimulator psilocybin Diggings of 31 Xiongnu tumuli (dated from the late 1st c. B.C. to the early 1st c. AD) of the Noin-Ula burial ground (Mongolia) carried out in 2009 by an expedition of the Institute of Archaeography and Ethnography, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (SB RAS), have discovered embroidered woolen textiles preserved by a miracle. Their complete restoration is a long way to go; however, the first fragments restored have revealed exceptional information On the altar the flame burns – two tongues on the sides and an S-shaped sign in the middle. The flame of king’s fireplace mounted on the altar is a symbol of royal grandeur On the altar the flame burns – two tongues on the sides and an S-shaped sign in the middle. The flame of king’s fireplace mounted on the altar is a symbol of royal grandeur Inside a deep Xiongnu grave hidden in the thickly wooded Sudzuktè pass, on the bottom of the burial chamber, archaeologists found what they had long been searching for: a layer of clay revealing the outline of textile relics. This was the third find to date; all of them were made in the well-known Xiongnu burial ground of Noin-Ula: the first fragments of a unique textile were found here as early as in the 1920s by the expedition of the eminent traveler and scholar P. K. Kozlov. Like many other things, the precious fabrics happened to be in the graves of rich nomads because of the trade along the Silk Road. Xiongnu did not participate in the trade deals but they controlled a long stretch of this perennial spring of foreign goods. Basing on the first find, the researchers believed that the textile from the Xiongnu burial ground was made in Bactria (Pugachenkova, 1966). However, the finds made in 2006 and 2009 do not allow identifying this textile so unambiguously. Of greatest surprise though was the find made in 2009, or, to be more exact, the unusual pattern involving people and animals embroidered on the textile. The fragments of the textile found were parts of a carpet composed of several cloths of dark-red woolen fabric. The fabric itself mast have been meant for mantles. A sign of this is the narrow maroon woven stripes with “pockets.” These important ornamental details are known not only from the numerous finds of real textiles in Dura-Europos, Syria, in Palmira and in the Palestinian Cave of Letters, but also from frescos, paintings on Egyptian sarcophagi, and early Christian mosaics (Yadin, 1963). Similarly to the known mantle textile, the woven stripes of the Xiongnu find do not go from one edge to the other but begin and end within a single cloth. Their cut bits were sewn together without taking into account the location of woven stripes: the ornamental element, so important for making mantles, this time proved to be unnoticed. The embroidered fabric filled the narrow space between the chamber’s wooden walls and the coffin, which was placed in the middle on another, not embroidered textile. As a matter of fact, the embroidered carpet was laid along the corridor used for the burial ceremony. On top of the fabric was a thick layer of blue clay brought on purpose, which, according to the Chinese tradition was used to make the chamber waterproof. This clay cover made the restorers’ work very hard but preserved the textile. Beside the altar flame