#Samuel Putnam

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yes, but also no. Oliver in the 70s looks like Samuel Farnsworth, cause that who portrayed him in the season 2 episode The Tell.

Also, they did attended the same party in the 70s, so they probably already met, just he was this up and coming Broadway director, and she, in the world of show business, was nobody. Also, he already fell for Roberta at this point.

I saw these pics and it was inevitable: what if Loretta and Oliver had met in the 70s??? These would have been them ♡

#yes i am very fun at parties why do you ask#oliver putman#loretta durkin#roberta putnam#martin short#samuel farnsworth#meryl streep

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It is rather a curious thing, my young friend, but that is exactly my record. I could outlift any man in Southern Illinois when I was young, and I never was thrown [in a wrestling match]. There was a big fellow named Jack Armstrong, strong as a Russian bear, that I could not put down; nor could he get me on the ground. If George [Washington] was loafing around here now, I should be glad to have a tussle with him, and I rather believe that one of the plain people of Illinois would be able to manage the aristocrat of old Virginia."

-- Abraham Lincoln, to Illinois Judge Samuel H. Treat, after Treat shared stories he had heard from George Washington's step-grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, who had noted that Washington was one of the strongest men of his generation and also a famous wrestler who had never been thrown in a match. ("Recollections of Lincoln" by James Grant Wilson, Putnam's Magazine, February 1909)

#History#Presidents#Abraham Lincoln#President Lincoln#George Washington#President Washington#General Washington#Presidency#Presidential Personalities#Putnam's Magazine#Quotes by Presidents#Presidents About Presidents#Presidents On Presidents#Presidential Quotes

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Stella (Italian-American,1877-1946)

Portrait of Samuel Putnam

Oil on canvas

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giles Corey’s Ghost and Curse

Giles Corey and his wife along with 25 other people were accused of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts by a group of young girls in 1692.

Corey, born in England in 1611, was a wealthy farmer who lived with his wife five miles southwest of Salem in what is today Peabody.

Corey’s accusers were three young girls, Abigail Williams, Ann Putnam and Mercy Lewis, they along with two other girls had implicated most of the victims in the Salem Witch Trails.

Giles and his wife Martha were members of the Salem Town Church where they were a part of a group of members who did not want Reverend Samuel Parris appointed the minister of this church in 1689.

Ironically, Abigail Williams was Parris’s 11-year old niece and one ringleader of the girls involved in the accusations. Putnam was the other leader.

Corey was brought before the local magistrates, he refused to enter a plea so he was thrown in jail.

On September 9th his wife was sentenced to die along with five others.

At his trail the girls stated he was “in league with the devil.” Corey refused to enter a plea because he knew the law stated he could not be tried, condemned, and executed until he stated he was either innocent or guilty.

Historians believe that he was avoiding this because he knew he was going to be found guilty which meant his land would be confiscated. He wanted it turned over to his heirs. He and Martha had 3 children from previous marriages.

Since he stayed mute, the court decided that a confession should be forced out of him. Corey was ordered to undergo peine forte et dure or pressing.

On September 19th he was dragged, naked to an open field where he was placed on a board that had been put in a shallow pit. Another board was placed on top of him.

Heavy stones and bricks were placed on top of him. For three days he endured this torturous pain, all the time remaining silent.

On September 22nd the end was near. Corey’s mouth was dry with thirst and his face was swallow and red. George Corwin, whose ghost is mentioned in another post here, was the Essex County sheriff at the time.

He knelt on the ground next to Corey having seen his lips move. He felt that Corey was about to relent but instead Corey uttered these now famous words, “More weight!”

With his dying breath Corey called out. “I curse you, sheriff, and I curse all of Salem.” That same day Martha was hanged with eight other people.

The witch trail executions stopped after this. Salem’s townspeople realized shortly after Corey’s pressing that all the girl’s testimony had been lies.

Nineteen people were hanged, four or five others died in prison waiting for their trails or executions. And Corey died under stones.

This torturous death resulted in his ghost haunting the Howard Street Cemetery today. It is believed he also haunts the Joshua Ward House in Salem–more information about this is in the link above.

This cemetery did not open until 1801 but it was on this land where Corey was pressed in a pit. It is believed his body is buried here as well.

Several witnesses have stated they have seen his apparition floating among the tombstones. Others state they have felt his clammy hands touch them.

As for the curse, George Corwin died of a heart attack. Other Essex County sheriffs have suffered from heart conditions as well. Several over the years reported seeing Corey’s ghost in their bedrooms.

Those who reported this sight stated they felt a strong pressure on their chests that didn’t go away until Corey’s ghost disappeared.

There is also a legend that states when Corey’s ghost appears he acts as a harbinger. It is said people saw his ghost just before the June 25, 1914 Great Salem Fire that destroyed most of the city.

Others believed Corey’s curse caused this fire.

#Giles Corey’s Ghost and Curse#Giles Corey#Salem#Witch Trials#Salem Witch Trials#ghost and hauntings#paranormal#ghost and spirits#haunted locations#haunted salem#myhauntedsalem#salem massachusetts#paranormal phenomena#ghosts and spirits#ghosts#spirits#Salem Curse

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

In his first, jointly written article for the Crimson, Buttigieg urged his fellow students to view not only community service but also political engagement as a valuable form of extracurricular activity. Buttigieg himself had worked briefly in a shelter for battered women during the summer after his freshman year. But as was happening elsewhere, a rift was opening at Harvard between students committed to such work, or to tutoring students or volunteering at homeless shelters, on the one hand, and those committed to political action on the other. In the Crimson article Buttigieg expressed alarm at how few young people were voting, working in campaigns, or participating in demonstrations. “In a nation where a lifetime of honorable work in direct service could be wiped out by a single stroke of poor policy from an elected official or legislature, the absence of our generation’s voice from the political process is a hazardous reality for anyone committed to social progress, and a red flag for democracy itself.”

That commitment brought Buttigieg to my classes in his senior year. The course he took in the fall semester, Social Thought in Modern America, was described by the Crimson as “the toughest humanities class at the College, combining soul-crushingly dense and difficult material with a will-breaking workload.” In other words, it was a class for people like Pete, Previn Warren, their friend and fellow IOP stalwart Ilan Graff, and fifty-two other smart, intellectually ambitious students keen to study the relation between ideas and politics in post–Civil War U.S. history. Because the course involved a great deal of class discussion, and student demand exceeded the number of names I could learn—and I believe teachers should know their students—I limited enrollment. Instead of choosing the class by lottery, as many professors do in such circumstances, I preferred to decide who should enroll.

To inform my judgments, I required interested students to write an essay explaining why the course was important to their studies at Harvard and, if possible, to their plans afterward. I also required interested students to meet with me, after I had read their essays, to discuss their reasons in greater detail. Because the course involved three discussions a week—twice a week for half of the ninety-minute lecture meetings, and once in the smaller discussion sections run by graduate students—I wanted to know which students were willing to stay on top of the readings, write the required three essays, and prepare for midterm and final examinations that involved identifying passages from the readings as well as writing synthetic essays.

Tempting as it is to contest the Crimson’s characterization, the course was, and has remained, demanding. The readings in 2003, which averaged 250 pages a week, included works of philosophy, social and political theory, religion, literature, and cultural criticism. Writers included the usual suspects for a course in American intellectual history: William James, John Dewey, and W.E.B. Du Bois; William Graham Sumner, Edward Bellamy, and Louis Brandeis; Chief Joseph, Helen Hunt Jackson, and Black Elk; Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Jane Addams; Gertrude Stein, T. S. Eliot, and Walter Lippmann; Reinhold Niebuhr, John Courtney Murray, and Martin Luther King, Jr.; Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, and Malcolm X; Clement Greenberg, Allen Ginsburg, and Betty Friedan; Samuel Huntington, Daniel Bell, and Irving Kristol; Judith Butler, Robert Putnam, and Kwame Anthony Appiah; and others. Students wrote essays on topics such as the impact of science on post–Civil War culture; the role of ethnic diversity and racial differences in shaping twentieth-century American politics and ideas; varieties of American feminist thought; and the relation between pragmatist philosophy and democracy. In short, the course was not intended for those who, in the words of New York Times columnist Ross Douthat (himself a survivor of the course), were looking to “skate through” Harvard.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Amelia Earhart

American aviator

(July 24, 1897–1937)

Amelia Mary Earhart was an American aviation pioneer and writer. Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

Born: July 24, 1897, Atchison, Kansas, United States

Siblings: Grace Muriel Earhart Morrissey

Full name: Amelia Mary Earhart

Known for: Many early aviation records, including first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean

Spouse: George P. Putnam (m. 1931–1939)

Awards: Distinguished Flying Cross, Legion of Honour

Parents: Samuel Stanton Earhart, Amelia Otis Earhart

Amelia Earhart reading letter over radio to Admiral Richard Byrd’s Antarctic expedition, 1929.

511 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Black was enslaved in the household of Nathaniel Putnam of the Putnam family who was accused of witchcraft during the Salem witch trials. Nathaniel’s nephew was Thomas Putnam, one of the primary accusers, though Nathaniel himself was skeptical. She was accused of being a witch and arrested on April 21, 1692, along with several others. The reason for the arrest of these individuals on the surviving arrest warrant is listed as “high suspicion” of witchcraft performed on Ann Putnam Jr., Mercy Lewis, and Mary Walcott based on a complaint by John Buxton and Thomas Putnam. She was arrested, indicted, and imprisoned, but did not go to trial, and was released by proclamation on January 21, 1693. She returned to Nathaniel’s household after she was released, another indication of Nathaniel’s view of the charges against her.

Along with Tituba and Candy, she was one of three enslaved accused during the hysteria. All of them survived.

Her examination, which was recorded by Samuel Parris, was notable for the fact she was asked to re-pin her neckcloth, which caused the afflicted girls, including Mary Walcott, Abigail Williams, and Mercy Lewis to be pricked, to the point of drawing blood, according to the transcript. She maintained her innocence.

She was put on trial and no one appeared against her, so she was released. In his book, Satan and Salem, Benjamin Ray puts forth the “likely” possibility that Nathaniel Putnam was simply too well respected for anyone to accuse his servant of wrongdoing. He did not accuse her himself, and he paid her jailing fees and took her back into his household. He further theorizes that her steadfast testimony as to her innocence might have been due to Putnam’s coaching. Her accusers may have been retaliating for Nathaniel having spoken out in defense of Rebecca Nurse. Little else could be gained by accusing an enslaved, as they did not own property. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Greetings, Scholars!

After our initial introduction, it's time to dive into the heart of our journey - the essential readings. These foundational texts provide a comprehensive exploration of American politics, covering everything from the grassroots to the echelons of power. We'll be going through these readings systematically, discussing their main arguments, implications, and relevance to contemporary political discourse.

Below, I have provided our initial list of essential readings. This list is, by no means, exhaustive. It's a starting point for our exploration, but we're not confined to it. If you have any requests, recommendations, or come across a gem that you believe should be shared, please feel free to suggest. After all, academic pursuit thrives on collaboration and openness to new perspectives.

The list is as follows:

Aldrich, John Why Parties?

Alvarez & Brehm Hard Choices, Easy Answers

Arnold, Douglas The Logic of Congressional Action

Bartels, Larry Unequal Democracy

Baumgartner & Jones The Politics of Attention

Baumgartner & Jones Agendas and Instability in American Politics (latest ed.)

Baumgartner, et al. Lobbying and Policy Change

Bensel, Richard The Political Economy of American Industrialization, 1877-1900

Berry, Jeffrey The New Liberalism

Browning, Rufus, et al. Protest Is Not Enough

Burns, Schlozman & Verba The Private Roots of Public Action

Cameron, Charles Veto Bargaining

Campbell, Louise How Policies Make Citizens

Cohen, et al. The Party Decides

Converse, Philip "The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics," in Apter (Ed.),

Ideology and Discontent

Cox & McCubbins Setting the Agenda

Delli Carpini & Keeter What Americans Know About Politics and Why it Matters

Erikson, MacKuen, & Stimson The Macro Polity

Fiorina, Morris Retrospective Voting in American National Elections

Fiorina, Abrams & Pope Culture War? (3rd ed)

Gilens Affluence and Influence

Green & Shapiro Pathologies of Rational Choice Theory

Green, Palquuist, & Schickler Partisan Hearts and Minds

Hacker, Jacob The Divided Welfare State

Hajnal, Zolton America’s Uneven Democracy

Hansen, John Mark Gaining Access

Harvey, Anna Votes Without Leverage

Hibbing, Smith & Alford Predisposed

Hero, Rodney Latinos and the US Political System.

Iyengar, Shanto Is Anyone Responsible?

Jacobson, Gary The Politics of Congressional Elections

Kernell, Samuel Going Public (latest ed.)

King & Smith Still a House Divided

Kingdon, John Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (latest ed.)

Krehbiel, Keith Pivotal Politics

Mann & Ornstein It's Even Worse Than it Looks

Mayhew, David Electoral Realignments

Mettler, Suzanne Soldiers to Citizens

Milkis & Nelson The American Presidency (latest ed.)

Mutz, Sniderman, Brody Political Persuasion

Neustadt, Richard Presidential Power

Olson, Mancur The Logic of Collective Action

Ostrom, Elinor Governing the Commons

Page & Shapiro The Rational Public

Patashnik, Eric Reforms at Risk

Pierson, Paul Politics in Time

Putnam, Robert Bowling Alone

Rosenstone & Hansen Mobilization, Participation and Democracy in America

Schlozman, Verba & Brady The Unheavenly Chorus

Skocpol, Theda Protecting Soldiers and Mothers

Skorownek, Stephen The Politics Presidents Make

Smith, Steven S. Party Influence in Congress

Stone, Clarence Regime Politics

Stone, Deborah Policy Paradox and Political Reason

Stonecash & Brewer Split: Class and Cultural Divisions in American Politics

Strolovitch, Dara Affirmative Advocacy

Verba, Schlozman & Brady Voice and Equality

Weimer & Vining Policy Analysis (latest ed.)

Wilson, J.Q. Bureaucracy

Zaller, John The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion

Each reading will have its dedicated blog post, where I'll summarize the key arguments, provide a critical analysis, and relate the text to our broader understanding of American politics. More importantly, I encourage you to share your thoughts, critiques, and insights as well.

The sequence of our reading will not necessarily follow the order in which the books are listed. Depending on our discussions, current political events, or requests, we might jump around the list. Flexibility will keep our exploration fresh and relevant.

So, let's embark on this intellectual adventure! It's time to dig into these fascinating texts and unravel the complex, dynamic world of American politics. Here's to a journey full of discovery, debate, and deep insights!

Happy Reading,

The Capitol Scholar

#american politics#american president#political communication#political science#academia#public policy#public opinion#phd scholar#grad school#Comprehensive Exams

1 note

·

View note

Text

discuss

#the crucible#abigail williams#john proctor#elizabeth proctor#mary warren#mercy lewis#giles corey#martha corey#rebecca nurse#tituba#samuel parris#betty parris#ann putnam#thomas putnam#judge danforth#john hale#the crucible memes#arthur miller#english literature

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

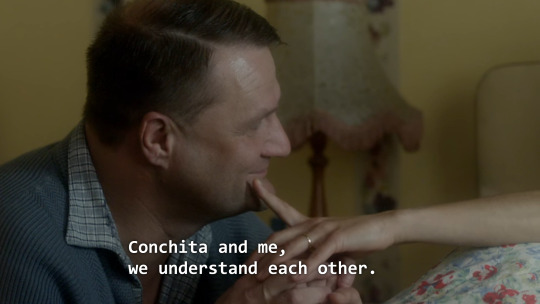

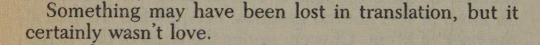

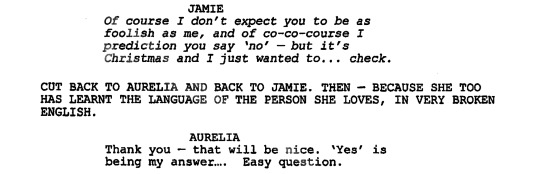

Can you do a web about the crossing of foreign languages, like two people of different translations meeting and communicating despite the barrier? Just generally linguistics I suppose.

Robert A. Johnson, The Fisher King and the Handless Maiden

Andrew Sean Greer, Less

Wiktionary definition of the Irish Gaelic word for ‘pulse’, chuisle

Jack Gilbert, The Forgotten Dialect of the Heart

Jeanette Winterson, The Passion

Call the Midwife (2012–), 1x01

Andrés Neuman, ‘Translating Each Other’ in World Literature Today (trans. George Henson)

Erich Segal, The Class

Nizar Qabbani, Language

Love, Actually (2003) dir. Richard Curtis

Peter Newmark, A Textbook of Translation

Kim Thúy, Ru

R. F. Kuang, Babel, Or the Necessity of Violence

Luigi Pirandello, One, None and a Hundred Thousand (trans. Samuel Putnam)

Sierra Demulder, ‘Heart Apnea’ from The Bones Below

Andrea Gibson, Maybe I Need You

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

#webs#web weaving#theme: language#theme: linguistics#theme: love#theme: connection#theme: the written word#theme: when words are not enough#mine#requests#robert a. johnson#andrew sean greer#jack gilbert#jeanette winterson#andrés neuman#erich segal#nizar qabbani#love actually (2003)#peter newmark#kim thúy#r. f. kuang#luigi pirandello#sierra demulder#andrea gibson#walt whitman#call the midwife#I ALWAYS REMEMEBER ONE THE SECOND AFTER POSTING. ALWAYS#anyway i watched the pilot ten (10) years ago and i still remember this scene

546 notes

·

View notes

Quote

...on our March down [to Bunker Hill] we met many of our worthy friends wounded sweltering in their own Blood, --carried on the Shoulders of their fellow Soldiers--judge you what must be our feelings at this shocking Spectacle,--the orders were, press on, press on, --our Bretheren are suffering and will soon be cut off. Thro the Cannonadeing of the Ships, Bombs,--Chain Shot, Ring Shot & Double headed Shot flew as thick as Hail Stones,--but thank Heaven, few of our Men suffered, by them, but when we mounted the Summit, where the engagement was,-- good God how the Balls flew.--I freely Acknowledge I never had such a tremor come over me before.-- [...] we covered their Retreat till they came up with us by a Brisk fire from our small Arms,--the Dead and wounded lay on every side of me,--their groans were piercing indeed, tho long before this time I believe the fear of Death had quited almost every Breast,--[...] we secured their Retreat,--but alas in the Fort fell some Brave Fellows--among the unhappy Number, was our worthy friend Dr. Warren, alas he is no more, --he fell in his Countrys Cause,--and fought with the Bravery of an Ancient Roman, they are in possession of his Body and no doubt will rejoice greatly over it.--After they entered our Fort they mangled the wounded in the Most horrid Manner, --by running their Bayonets thro them,--and beating their Heads to pieces with the Britch's of their Guns. [...] Good Doctr. Warren, "God rest his Soul," I hope is Safe in Heaven! Had many of [the Provincial] Officers the Spirit & Courage in their Whole Constitution that he had in his little finger, we had never retreated.

Samuel Blachley Webb to his brother, Joseph Webb, on June 19th, 1775, detailing the Battle of Bunker Hill and the death of Dr. Joseph Warren. [Writing from the War of Independence pg 36-40] Samuel Blachley Webb himself was wounded at the battle of Bunker Hill, which I couldn’t help but notice he neglected to write in his letter to his brother. It was a near-miss that could have killed him had he been a little less lucky. He wrote in a letter to his father-in-law, Silas Deane, on July 11th, “For my part, I confess, when I was descending into the valley from Bunker’s Hill, side by side of Capt. Chester at the head of our Company, I had no more tho’ts of ever rising the Hill again, than I had of ascending to Heaven as Elijah did--soul and body together. But after we got engaged--to see the dead and wounded around me--I had no other feeling but that of Revenge. Four men were shot dead within five feet of me; but, thank Heaven, I escaped with only the graze of a musket ball on my head” [x]. Webb had been elected 1st Lieutenant of a Company of Militiamen under Capt. Chester and led the men in his absence until his return just before the battle. Webb and Chester were, apparently, singled out in the General Orders following the battle for their Gallantry at Bunker Hill, having been at the center of the hardest fighting and critical to the success of the retreat [x]. On July 22nd, 1775, Samuel Blachley Webb and Israel Putnam Jr. would be appointed the first Aides-de-Camp to Major-General Putnam [x]. One year later, on June 21, 1776, George Washington would appoint Webb to his own staff, as well as appointing Richard Cary and Alexander Contee Hanson [x], and on the next day, Aaron Burr would be appointed to Putnam’s staff in his place [x].

#Samuel Blachley Webb#Israel Putnam jr#Richard Cary#Aaron Burr#Alexander Contee Hanson#aides-de-camp#Israel Putnam#Joseph Webb#Joseph Warren#John Chester#Silas Deane#Putnam's aides#bout time i did a little talking about Sam

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who would you put in an American statue garden? Assume no limit for how many

all the best presidents (i won't name them all but just to list a few: washington, adams, j. q. adams, jefferson, madison, monroe, fdr, teddy roosevelt, lincoln, etc), franklin, alexander hamilton, friedrich list, henry clay, henry carey, samuel adams, ethan allen, thomas young, john jay, james wilson, gouverneur morris, christopher columbus (tbh i'm tempted to include figures like leif erikson and prince madoc because even though they were never americans, like columbus, there is a mythopoetic/cultural value), lafayette, john winthrop, cotton mather, nathanael greene, friedrich wilhem von steuben, nathan hale, johnny appleseed, emperor norton, robert e. lee, william tecumseh sherman, daniel boone, lewis and clark, sacagawea, davy crockett, emerson, thoreau, walt whitman, longfellow, hilda doolittle, emily dickinson, nikola tesla, einstein, eli whitney, abigail adams, edgar allen poe, john brown, herman melville, butch cassidy, wyatt earp, doc holliday, wild bill hickok, sundance kid, john henry, andrew carnegie, nathaniel hawthorne, washington irving, horace mann, john dewey, wernher von braun, j. robert oppenheimer, john marshall, wiliam penn, junipero sera, john d. rockefeller, clara barton, fanny wright, thomas edison, alexandar graham bell, ezra pound, kerouac, william faulkner, steinbeck, hemingway, dolley madison, john muir, annie oakley, lovecraft, eleanor roosevelt, john browning, samuel colt, elvis presley, claude shannon, henry miller, kanye west, stanley kubrick, john von neumann, thorstein veblen, edward bellamy, henry ford, cornelius vanderbilt, betsy ross, black hawk, sitting bull, tecumseh, hart crane, h. l. mencken, tennessee williams, charles sanders peirce, william james, quine, hilary putnam, richard rorty, charles hartshorne, walt disney, mark twain, etc.

#this list probably isn't exhaustive#well it definitely isn't#but i tried to be pretty thorough#also in this hypothetical statue garden#i would probably make a section dedicated to non-americans#that i consider honorary americans#or people who i believe are influential or important to the american tradition#or just people i consider great and worthy of admiration#like cicero and cato and aristotle and homer and aeschylus and hercules#or john milton or cromwell or napoleon#or machiavelli or montesquieu#yeah i know you said there could be no limit#but i could probably go on for a long time#so i'm just gonna have to leave this list how it is for now

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

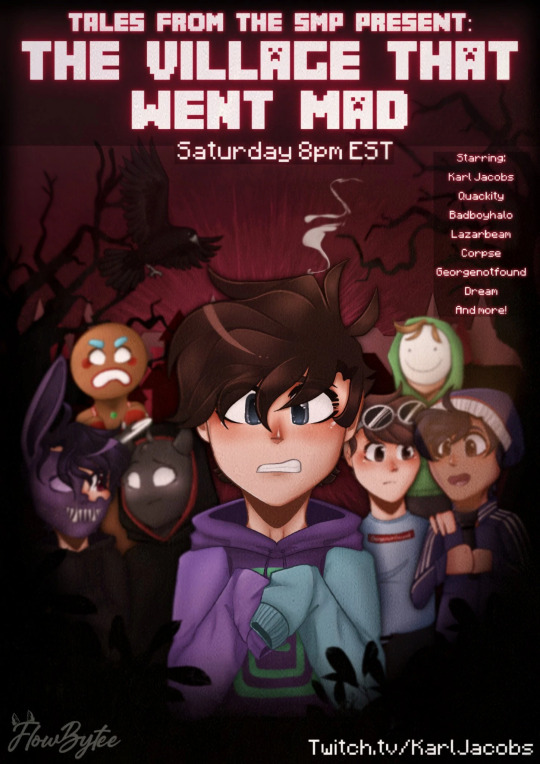

Truth in the Tales: The Town That Went Mad (Parts 1 & 2), Witches, and Jamestown

So, this one’s topical! Definitely not for any political reasons at all (no, not at all), but because we just got a non-canonical sequel!

Hi, I’m A.D., I’m a history student, and this week’s Truths are about two European (specifically English) settlements in the New World that went fucking insane. The lessons won’t be completely comprehensive, but I encourage those interested to go on their own dive, and I’m always willing to explain more in detail if asked.

Once again, I’m using the Tales from the SMP carrd to get these episodes. The carrd is credited to @discduo on Tumblr, but if that’s not right, I’ll figure out who it actually is and link accordingly. With all the credits and citations I’m fixin’ to use, it’ll be a wonder if this makes it into the tags at all...

(Painting: Examination of a Witch by T. H. Matteson.)

The episode stars Karl Jacobs, BadBoyHalo, Corpse Husband, Dream, GeorgeNotFound, LazarBeam, Ponk, Quackity, and Tubbo. The episode takes place hundreds of years in the past and follows the village of "Not A Very Good Town" as its inhabitants (all except Karl) roleplay the game Town of Salem (also known as Mafia). The stream was comprised of two rounds, one practice round and one canon round.

Part One: The Salem Witch Trials

(Note: Most of this section comes from my own memory. I was a weird child.)

The Town That Went Mad is, as the episode description says, based off of the game Town of Salem.

(Image courtesy Steam.)

Town of Salem is (again, as the episode description says) basically the card game mafia. There’s a group of people, and they have to find the witches/the mafia and vote them out before the mafia kills them all.

Now, there wasn’t a mafia in the village of Salem, Massachusetts, in the final decades of the 17th century. What there were a lot of were what we call WASPs these days. That is to say, White Anglo Saxon Protestants. More specifically, these people were Puritans. And the Puritans were bad news. Imagine the most hardcore Christians possible, then make them more hardcore. They didn’t have funerals for their deceased until the mid-18th century because they believed funerals to be unholy. They were heavy believers in the patriarchy. A woman’s place, to a Puritan, was in the home having children and taking care of children. But not too many children, for having too many children would be a sign of dealing with the devil. And not too few children, either, for having too few children would be a sign of dealing with the devil.

The Puritans left England for the New World because of religious persecution. That is because they were so unpopular in England that they got chased out of the country. I am saying this because it is true, not as any part of a political statement. The English fucking hated these guys.

So the Puritans (among other New World settlers) ended up in what is now the northeastern section of the United States. Namely: Massachusetts, New York, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Maine. Rhode Island and Connecticut are outliers and should not be considered for the sake of this post, and nobody gave a fuck about Vermont even back then.

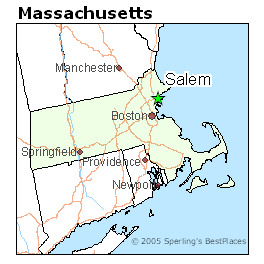

(Map: Salem’s location in Massachusetts.)

Cut to the year 1692. Fresh out of a British war with France in 1689 and a smallpox epidemic, the settlers of Salem Village were on edge. Add to that general Puritan paranoia (you didn’t know who would end up being an agent of the devil) and the villagers’ hatred of outsiders, and maybe some poisonous fungus, and you have the set up for one hell of a year.

In the January of 1692, two young girls- Elizabeth “Betty” Parris and Abigail Williams- began having fits. Imagine a stereotypical demonic possession: coughing, twitching, spasming, uncontrollable screaming. Soon, more and more young girls began showing the same signs of “bewitchment”, including one Anne Putnam, Jr., which will come back up in a moment. In February, an arrest warrant was put out for local minister Samuel Parris’s Caribbean slave Tituba as well as two other women: a homeless beggar named Sarah Good and an elderly woman named Sarah Osborn. See, the women were witches. That was the only reasonable explanation.

From there, things only got worse.

During their trial, Good and Osborn pleaded not guilty. Tituba, likely trying to get off with a lighter sentence, claimed that there were other witches besides her in Salem. And that’s where the fun part began.

(Engraving: Unattributed.)

Beginning in the May of 1692, the Salem Witch Trials proper began. Over the course of the next year, 19 people were hanged upon suspicion of being a witch, 5 people died in prison, and one man, Giles Corey, was pressed under heavy stones until he was dead. Not all of the convicted were women, but the men who were suspected-slash-convicted-slash-killed were all related to the women accused. Interestingly enough, many of the accused were enemies of the Putnam family, with Putnam family members and supporters accusing even upstanding members of the village of witchcraft so long as the accused were people the Putnams were not in favor of.

I could go into long and heavy detail about just how this all went down, but, frankly, it’s a lot of legal bullshit nobody would be interested in. Needless to say, it didn’t reflect well upon the colony of Massachusetts that a single village had managed to spark a hysterical sweep of witch mania across the entire New World.

The Witch Trials ended in the May of 1693 when Governor William Phips stepped in and shut the whole thing down.

To this day, a witch hunt is used to describe a collection of pointless and generally-evidenceless accusation. Former President Tr*mp used the phrase a lot, though he used it incorrectly.

Part Two: Jamestown

There was originally only going to be one part to this post, the Witch Trials, but since Karl gave us a non-canon sequel to the episode, I think it’s only fair that I get to talk about something else neat from this time period as well.

So let me tell you all about the English colony that nearly ate itself to death.

(Note: Most of this section comes from my memory. Again, I was a weird child.)

(Map: Jamestown in relation to other English colonies.)

Jamestown is probably one of the more famous colonies from the time period. It was founded in 1606 by the Virginia Company and, despite going through many hardships, became the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. Prior to Jamestown was the failure colony of Roanoke, famous for its bullshit “disappearing colony” story. You all might remember Jamestown best for one of its leaders, a mister John Smith, who was absolutely nothing like how the Disney movie Pocahontas portrays him.

(Engraving: Jamestown: Massacre, 1622.' / 'The Massacre At Jamestown, Virginia, 1622.)

But this isn’t about John Smith. No. Because he actually went back to England in the winter of 1609, leaving the colony to fend for itself in the harshest winter its settlers had ever seen.

The winter of 1609-1610 is now known as “The Starving Times”, and for good reason! Things were fucked! There was famine. There was snow. There was sickness. Jamestown depended on outside trading for food for the most part, but their main trading partner, the local Powhatan tribe, refused to trade after food supplies began running low on their end after a 7 year famine. On top of that, the settlers were too afraid to leave their homes for fear of getting killed by the Powhatans , and for good reason. See, tensions had only been growing between the settlers and the tribe. It had gotten to the point by winter 1609 that the settlers, after trying to basically steal the last of the Powhatans’ food stores during a famine, had pissed the Powhatans off for the last time. They were killing any and all Englishmen found outside of the settlement, even, so nobody could go hunting. But that isn’t important. What is important is the fun bit that’s about to happen, and one of my favorite topics to talk about: cannibalism.

It starts like this:

You don’t have any food. The ground is cold and dead, and you can’t grow food. You can’t leave your homes to hunt for food. Because of the lack of nutrients, sickness begins sweeping across your village like crazy. Typhoid, mostly, but also colonial favorite dysentery. People start dying. Houses were torn down to be used as firewood.

Settlers, starving, began eating shoe leather and butchering horses. They ate dogs, cats, vermin, anything they could get their hands on. Insects, or whatever insects were hanging around in subzero temperatures in Virginia. Snakes. Rats.

But then they ran out of even that.

One man, George Percy, wrote what came next.

“[Settlers] Licked upp the Bloode which ha[d] fallen from their weake fellowes.”

Settlers dug the dead out of their graves, according to Percy, and there is forensic evidence of at least one person- a 14 year old girl- having been butchered and cannibalized, though it’s assumed that she was already deceased at the time.

(Photo courtesy the National Post.)

The winter was long and tortuous, and it nearly wiped Jamestown off of the map. If it had, then the United States of America might not even be a country, or it wouldn’t be as Anglicized as it is.

But, well, it didn’t disappear. Ships came in 1610 with supplies for settlers, and what came after was a relatively good time for English colonization. Unfortunately, that had horrible consequences for the local Native Americans. And from there, it’s all history.

Part Three: Conclusions?

Now, I originally wanted to do this post on torture devices because I know a lot about those, but I decided against it.

But back to Tales.

The Town That Went Mad is, again, purely Town of Salem. The way that the trials are carried out played out surprisingly close to the way that the original witch trials went. The accused were accused by their own friends and neighbors, people they had previously loved and cared about, and they were shown little to no mercy.

The episode itself has uh. Nothing at all to do with Jamestown. I just think Jamestown’s Starving Times are neat. I could talk all day about cannibalism, and I will when we get to the Wild West episode (if anybody has seen the Donner Party episode of Puppet History, you know what I’m talking about.)

Anyway.

Next ‘Week’: The Beach Episode and Actual Goddamn Motherfucking Piracy

#mcyt#dream smp#dsmp#tales from the smp#tftsmp#dsmp analysis#karl jacobs#truth in the tales#long post

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nathan Hale’s Death vs the Primary Sources

(aka did William Hull actually know anything?)

“The first the Americans heard of Hale’s death was on the evening of the twenty-second [September 1776], when Captain John Montresor…an aide de camp to General Howe, approached an outpost…under flag of truce. His main business…did not concern Hale, but was to transport to Washington a letter from Howe offering an exchange of high-ranking prisoners. Joseph Reed, accompanied by General Israel Putnam and Captain Alexander Hamilton, rode to meet him. After passing over the letter, he casually added that one Nathan Hale, a Captain, had been executed that morning.”

This passage comes from “Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring” by Alexander Rose and it, along with the wonderful @queerrevolution1776 inspired me to go on a (brief) primary source deep dive of Hale’s death. A challenge, given the lack of primary sources surrounding Hale’s spy work, and the tall tales that grew up around it.

I started here: Why was Hamilton there? He was not an aide-de-camp at this point, why would he be present? And that question, my friends, led to a whole host of others!

(Info under the cut because there is a lot, and it’s fascinating :))

The (Un)reliability of Recollection

The idea of Hamilton having been present to hear of Hale’s fate, so far as I can see, is first related in “Revolutionary Services and Civil Life of General William Hull”, a biography based on Hull’s unpublished memoirs, and written by his daughter, Maria Hull Campbell:

“In a few days, an Officer came to our camp, under a flag of truce, and informed Hamilton, then a Captain of the Artillery, but afterwards an aide to General Washington, that Captain Hale had been arrested within the British lines, condemned as a Spy, and executed that morning. I learned the melancholy particulars from this officer, who was present at his execution, and seemed touched by the circumstances attending it.”

William Hull was a friend of Hale’s from Yale, and they were both in the 19th Regiment, before Hale transferred to Knowlton’s Rangers. A lot of what we know of Hale’s death seems to come from Hull’s memoirs, right down to his (possibly incorrect and/or exaggerated) final words: “I only regret, that I have but one life to lose for my country.” Hull was a close friend of Hale’s, so it does make some sense that he’d know something of it. However, the above biography was written in 1848, and related conversations that had taken place a long time earlier. Campbell herself admits she includes conversations not even present in her father’s memoirs.

Though her book is not the only 18th/19th century one about Hale’s death, it quickly became clear that all of them were based on conversations with Hull. The first time the name ‘Nathan Hale’ even entered the public conscious properly after the war was in 1799, in Hannah Adams’ “A Summary History of New England and General Sketch of the American War” where she writes: “The compiler of this History of New England is indebted to Gen. Hull of Newton for this interesting account of Captain Hale.”

Hale isn’t mentioned again until 1824, in a book by Jedediah Morse, who says he got his info from Adams, who in turn got it from Hull. It seems likely, then, that the idea of Hamilton being there (and indeed, that most of what we know) came from Hull’s supposed recollection, 20+ years after the event took place.

Now, this is not to say that Hull was lying. Return records show that he and his Regiment were certainly present at “Camp near to Harlem Heights” with Washington’s forces at the time that Washington would have been given the information about Hale, and we know Hamilton and his Artillery were present also, as it is at Harlem Heights that he apparently first came to Washington’s notice (according to John C. Hamilton). It did seem a bit strange though, to both me and @queerrevolution1776 , for Hull or Hamilton to have met with an official flag of truce, when they were both only Captains, and not on Washington’s staff (he’d only just become aware of Hamilton’s existence, after all).

Washington makes no mention of either of them in his correspondence, instead writing to Jonathan Trumbull Sr. that it was Colonel Joseph Reed whom Howe’s aide, John Montresor, met with. It makes sense that Reed would have met with Montresor, given his position on Washington’s staff. Reed is mentioned in Rose’s book, but not Hull’s account, and I thought that was a discrepancy worth a look. Hull, writing after the fact, mentions only Hamilton, who by then was a well-known, and scandalous, public figure. Reed, on the other hand, was nowhere near as popular, and perhaps did not serve as such an interesting figure in a story about Hull’s friend, one of America’s earliest spies.

Sure, Hamilton could have been nearby, or overheard the discussion, and in turn told Hull what he had heard—which could explain why Hale’s last moments have been exaggerated, or perhaps accidentally falsified, given that a British officer who was present apparently heard: “It the duty of every good officer, to obey any orders given him by his commander in chief” and not what is so often recounted. Even a newspaper (The Essex Journal) publishing an account five months later, quoted Hale as having said: “If I had ten thousand lives I would lay them all down, if called to it, in defence of my injured, bleeding country”—No one seems quite able to agree exactly what he said! Hull may well have also told his children he was there to make the story seem more personal, and exciting.

(And I’m really starting to doubt that Hamilton was at the meeting at all. It’s never mentioned in any of his writing, or in the John C Hamilton biography)

There’s no “official” reports of Hale’s death either (excepting the noting of his death on the 22nd September casualty list) which is why so much has relied heavily on what Hull claimed to have been told. When Washington wrote Trumbull about the flag of truce meeting the next day, he was mostly concerned with the fire that had engulfed New York the day before, and the claims that Continental soldiers and spies had set it. The only possible reference we have from him that concerned the meeting between Reed and Montresor, with perhaps an oblique reference to Hale, is as follows:

“On Friday night about eleven or twelve o’Clock a fire broke out in the City of New York, which burning rapidly till after Sunrise next morning, destroyed a great number of Houses—By what means it happened we do not know; but the Gentleman who brought the letter out last night from General Howe, and who was one of his Aid De Camps informed Colo. Reed that several of our Countrymen had been punished with various deaths on account of it. Some by hanging, others by burning & c. alledging that they were apprehended when committing the fact.”

Howe himself never mentioned Hale explicitly in official correspondence between him and Washington, and Washington never did either. In fact, neither of them mentioned the spies or the fire to one another at all, concerned with prisoner exchanges, and the accusation of ill-treatment of British prisoners (Howe to Washington 21st September 1776 and Washington to Howe 23rd September 1776). Hale, and his fate, was unfortunately left to Montresor’s verbal account, and Hull’s dubious reporting.

Tench Tilghman on Hale’s Death

In terms of other primary correspondence that might reference Hale’s death, even remotely, we have accounts from Washington’s aide-de-camp, Tench Tilghman.

Firstly, Tilghman wrote his father, James Tilghman, on the 25th September 1776, of the events and executions surrounding the fire. He was sent to deliver Washington’s reply to Howe’s camp under another flag of truce the day after Montresor’s, and spoke with some men in Howe’s camp then:

“Reports concerning the setting fire to New York: If it was done designedly, it was without the knowledge or Approbation of any commanding officer in this Army…every man belonging to the Army who remained in or were found near the City were made close prisoners. Many Acts of barbarous cruelty were committed upon poor creatures who were perhaps flying from the flames, the Soldiers and Sailors looked upon all who were not in the military line as guilty, and burnt and cut to pieces many. But this I am sure was not by Order. Some were executed next day upon good Grounds… I went down to the Enemy's lines yesterday with a Flag to settle the Exchange of prisoners…I met a very civil Gentleman with whom I had an Hours conversation…”

In Rose’s book, he mentions Hull & Colonel Samuel B. Webb going with Tilghman to the camp to further question Montresor about Hale. Webb, another aide-de-camp to Washington, may well have gone. But it seems a bit strange for Hull to have done so. And Hull’s account did not mention Webb, or Tilghman, which is also a bit odd. Rose made no note of his source for this, but I’d like to find it! Perhaps it’s mentioned in Webb’s journals, something I’d have to travel to Yale to see :(

Tilghman did, eventually, mention Hale explicitly, though not by name, when he wrote to Egbert Benson on 3rd October 1776:

“I am sorry that your Convention do not think themselves legally authorized to make examples of those villains they have apprehended…The General is determined if he can bring some of them in his hand’s under the denomination of spies, to execute them. General Howe hanged a Captain of ours belonging to Knowlton' s Rangers, who went into New-York to make discoveries. I don’t see why we should not make retaliation.”

So he definitely knew of Hale’s death by then, and it seemed to anger him greatly.

Miscellaneous Reports of Hale’s Death

There were also reports made by various others, that mention explicitly, or might imply, Hale’s death:

“Friday last we discovered a vast cloud of smoke arising from the north part of the city, which continued '‘ill Saturday evening…those that were found on or near the spot were pitched into the conflagration, some hanged by their heals, others by their necks with their throats cut. Inhuman barbarity! One Hale in New York, on suspicion of being a spy, was taken up and dragged without ceremony to the execution post and hung up.” (A Letter from September 28th 1776)

“We hanged up a rebel spy the other day, and some soldiers got, out of a rebel Gentleman’s garden, a painted soldier on a board, and hung it along with the Rebel; and wrote upon it, General Washington, and I saw it yesterday beyond headquarters by the roadside.” (Kentish Gazette, November 1776)

“A spy from the enemy (by his own full confession) apprehended last night, was this day executed at 11 o’clock in front of Artillery Park.” (General Howe’s diary)

“The Enemy charged some stragglers of our people that happened to be in New York with having set the City on Fire designedly and took that occasion as we were told to exercise some inhuman Crueltys on those poor Wretches that were in their power.” (Committee of Secret Correspondence to Silas Deane 1st October 1776)

What does all this mean?

Hamilton probably wasn’t there (but I can’t make a call on that for sure!)

basically, it’s clear that the primary sources on Hale’s death are few, and somewhat contradictory in places. I found it super interesting, and thought y’all might too! Please keep in mind I’m not calling William Hull a liar (and I definitely haven’t done anywhere near enough research to say anything conclusively!)

But I definitely think it’s always worth examining what we think we know from primary sources. And it’s very fun!

#this took me literal days to collate so I hope y’all find it as interesting as I did#should’ve been doing uni work but no regrets#we all know history research makes me ridiculously happy#nathan hale#William Hull#alexander hamilton#tench tilghman#spy work#September 1776#american revolution#amrev#tw: death#izz gets historical#izz rambles

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

deciding if characters from the crucible would be able to survive a cup of mcdonald's sprite

starting off with our main bitch, john proctor: yes ✔and he would ask for another, only only to be killed by me squeezing hand sanitizer into his hand :(

keeping with the family! elizabeth: no ❌ despite being able to keep going through everything, i think that sprite would be the last straw (no pun intended) but she's my bestie and unproblematic fave so i'd simply revive her <3

mary warren: no!! ❌ she couldn't even handle abby and the other girls lying about her, what the fuck is a sprite (of any kind!!!) gonna do??? :/

abigail williams: absolutely! ✔ ms girl deadass drank blood and is also a girlboss. probably drinks orange juice directly after brushing her teeth and considers this a normal activity.

betty parris: no ❌ couldn’t handle a little bit of dancing in the woods, a straw's worth of mcdonald's sprite would end her life

speaking of the parris family, reverend samuel parris: FUCK NO ❌ like his daughter, a single sip of that shit would kill him instantly! the carbonation bubbles would form a faction and end not only his career as a pastor but also his existence

tituba (my beloved): yes ✔ simply because i say so. she deserves it! no one can disagree

the poorest of meow meows, reverend john hale: no ❌ a strong gust of wind could end his life, and that's okay. a mcdonald's sprite would be too much for him :(

that BITCH thomas putnam: yeah :/ ✔ somehow he dealt with the weight of being (basically) a serial killer, so i think the sprite would do nothing. however, a sour patch kid immediately afterwards would be it for him, so don't lose hope 🙏

ann putnam: yeah! ✔ sorta. she'd get halfway through the cup and quit trying to survive :( but also she did nothing wrong besides be kinda mean for a bit far as i'm concerned! that's my truth and i'm sticking to it.

ruth (ann jr) putnam: nah ❌ like betty, she couldn't handle dancing in the woods. but i think her real life counterpart could. schrödinger's ruth <3

(okay okay last three below bc i'm tired of this shit)

giles corey: yeah!! ✔ he'd chug that shit and then continue about his day like nothing happened despite being an old man. good for you giles

(i think his first name is??) thomas danforth: no ❌ not because i don't think he could, but because i hate him next question

and finally, last but not least, rebecca nurse: no ❌ she definitely COULD as one of the three (3) sane individuals in salem village but would elect not to, and i respect that. bless you rebecca

#arthur miller#the crucible#classic lit#classic lit memes#classic literature#yes these are my opinions. no they are not wrong.#why would hand sanitizer kill proctor?? well darlings there is nothing on above or below this earth that can convince me#he knows what the fuck cleanliness is. i reduse to believe he has ever washed his hands in his life. not even during the yearly bath#that all historic white people took those hundreds of years ago#(btw that is a Joke. i do not speak on people's hygiene. it's simply not my style)#anyways!! are there other characters i could have added? yes. did i want to? kinda. but the post would be longer than it already is#nobody needs that#long post

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

What naval battles of the American revolution do you think are most pivotal? Which are most interesting to you personally?

Thanks for your question, and a good one it is indeed, which is why I needed some time to think about it, being unable to pick just one- but now I have. :-)

I think the most obvious answer would be the Battle of the Chesapeake (6 September 1781), simply because it was decisive as the French managed to prevent the British fleet commanded by Rear Admiral Thomas Graves (yes, another Graves- among the officers serving under him were his half-brother by his father's former secret second family and a nephew of his cousin- you've got to keep the business in the family, after all) from delivering reinforcements to Yorktown.

Much has been said about the undoubtedly very important Battle of the Chesapeake and other more well-known actions; but if I had to pick, and keeping in mind your questions, I would go for the Battle of Chelsea Creek (27–28 May 1775).

It aligns very well with my interests, and I think it marks the point where the nascent war, previously a pesky rebellion, turned personal for Graves, and may have prompted him to greater severity in future actions (think e.g. of the Burning of Falmouth).

I've seen you asked @benjhawkins the same question, whose reply was the Battle of Machias (11–12 June 1775), which I found surprising, as the fate of HMS Diana was a similar one to that of HMS Margaretta, and both actions occured within two weeks of another.

The short version of events is that Samuel Graves, spotting a smoke column around 14:00 on the 27th, from hay obviously being burnt on one of the islands (Noddle's Island), immediately ordered marines to be landed to engage the Americans under the command of Colonel John Stark. The American detatchment on Noddle's Island decided on a defensive strategy and instead island-hopped to the main American force on Hog's Island, from where they drove a substantial number of livestock towards the mainland.

HMS Diana was one of the vessels ordered to pursue, and in a best-case scenario, intercept the cattle-thieving Americans. The Diana, commanded by Lieutenant Thomas Graves (c. 1747–1814; guess whose nephew he was) continued in her pursuit until dusk, when her commander decided the waters of Chelsea Creek were too shallow to continue on. In fact, Graves had run the ship so far up Chelsea Creek, that he soon realised he was stuck. Signalling his uncle's flagship, the latter sent boats from HMS Preston and Somerset to come to Diana's assistance in order to pull her free; to add to the misfortune at hand, the day had turned out very calm, which didn't exactly help, either.

Naturally, it didn't take the Americans long to realise HMS Diana was stuck- General Putnam and perhaps as many as 1,000 troops and two field-pieces are said to have been present on the banks, watching on. Putnam is said to have waded waist-high into the water, calling out to the crew of the Diana that they would receive quarter if they were to surrender, but the British, who were still hoping the boats would pull them free, fired their cannon on the enemy troops on shore.

However, their luck ran out about 22:00 when the boats had to abort their mission of pulling the Diana free under heavy enemy fire. Accounts differ somewhat regarding when the Americans managed to set the Diana on fire, but the schooner, which at some point had tipped to one side, had to be abandonned.

Some say that Thomas Graves and his crew were still on board when the fire broke out; in any case, the entire crew could be transferred into the tender Britannia, commanded by Thomas' brother John (1743–1811) who had come to Diana's rescue. The story goes that Thomas Graves sustained severe (facial) burns, and John Graves was burnt as well, trying to rescue his little brother. I think this may well be only a dramatic later invention though (as if having to save your brother from certain death isn't dramatic enough); Samuel Graves' official report exaggerates the numbers of American forces present by multiplying the actual estimate times two, and I suppose he would have brought any serious wounds sustained by his nephew(s) up as a mark of their personal bravery and officer-like conduct.

Thomas Graves was court-martialled for the loss of the sloop, but not found guilty, and his uncle wrote to the Admiralty in order to secure reimbursements for any personal possessions lost by his nephew and crew of the Diana.

To me, the Diana is so important because this is the first time Admiral Graves, so often accused of apathy and a desire to not do anything at all, was personally invested in any action- the war that was merely a little rebellion, had caught up with him personally. Close with his nephews, I suppose a combination of the Battle of Chelsea Creek and the Battle of Machias two weeks later prompted him to abandon his cautious approach for a more direct, forceful one, which ultimately led to the inhabitants of Falmouth losing their homes, and Graves his career.

Actions like Chelsea Creek and Machias also showed the Americans that the British Navy wasn't invincible, which I think must have had a distinct psychological impact on their their morale.

I am rambling on for far too long- I hope this answered your question. :-)

#ask#ask reply#clove pinks#battle of chelsea creek#american revolution#revolutionary war#hms diana#thomas graves#john graves#samuel graves#the whole rotten family

12 notes

·

View notes