#Sackler Museum Harvard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Text

Cambridge, Massachusetts -- 12/15/12

#fotografía#fotografía original#original photography#photographers on tumblr#artists on tumblr#photography#sackler museum#harvard#harvard university

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Prophet’s Mosque at Medina (painting recto, text verso of folio 19) from a manuscript of prayer. Türkiye, Ottoman Empire. 1851 CE.

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum.

#ottoman empire#ottoman#turkiye#turkey#Turkish#turkish history#harvard art museum#art#culture#history#literature#1800s#modern history#turkic#turkic history#turkic culture

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Sage and Attendants Enjoying Chrysanthemums by a Stream Artist: Kanō Tansetsu (Japanese, 1655-1714) Date: ca. 1683 (Edo period) Genre: genre art Medium: album leaf; ink, color, and gold on silk Dimensions: 26.8 cm (11 in) high x 43.0 cm (17 in) wide Location: Arthur M. Sackler Museum (Harvard Art Museums), Cambridge, MA

#art#art history#Asian art#Japan#Japanese art#East Asia#East Asian art#Kanō Tansetsu#genre painting#genre art#album leaf#Edo period#17th century art#Arthur M. Sackler Museum

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

do you like THIEVES? are you a hardcore Leverage fan? somebody who watches Ocean's 11 - or Ocean's 8 - and think 'wish that were me'? do you want to eat Neal Caffrey up with a spoon? do you think the British Museum should give back all their stolen art?

boy, do I have the book for you!

PORTRAIT OF A THIEF by GRACE D. LI

This was how things began: Boston on the cusp of fall, the Sackler Museum robbed of 23 pieces of priceless Chinese art. Even in this back room, dust catching the slant of golden, late-afternoon light, Will could hear the sirens. They sounded like a promise.

Will Chen, a Chinese American art history student at Harvard, has spent most of his life learning about the West - its art, its culture, all that it has taken and called its own. He believes art belongs with its creators, so when a Chinese corporation offers him a (highly illegal) chance to reclaim five priceless sculptures, it's surprisingly easy to say yes.

Will's crew, fellow students chosen out of his boundless optimism for their skills and loyalty, aren't exactly experienced criminals. Irene is a public policy major at Duke who can talk her way out of anything; Daniel is pre-med with steady hands and dreams of being a surgeon. Lily is an engineering student who races cars in her spare time; and Will is relying on Alex, an MIT dropout turned software engineer, to hack her way in and out of each museum they must rob.

Each student has their own complicated relationship with China and the identities they've cultivated as Chinese Americans, but one thing soon becomes certain: they won't say no.

Because if they succeed? They earn an unfathomable ten million each, and a chance to make history. If they fail, they lose everything...and the West wins again.

WHAT YOU GET

pretentious af college students (mostly Will) who think they can get whatever they want (mostly Irene (but also Will))

STREET RACES. do you like Fast & Furious? good

complicated feelings about everything but especially, like, lesbians having complicated feelings about other lesbians who then fall in love (Irene and Alex)

FOUND FAMILY. the real treasure is the friendships we made along the way, and like, maybe also the relationships we repaired along the way

healing through stealing (Daniel (and Lily (and Alex (and Daniel's dad and Will and Irene and—))))

ART

discussions of identity, colonialism (and colonised art), art repatriation, the immigrant experience, class,

THEFT. so much theft. THIEVES BEING THIEVES.

immovable object ("girls have broken themselves trying to change him"!boy by which I mean Will because of course it's Will) meets unstoppable force (Lily)

did I say healing? I think I meant stealing. no healing. no stealing. no—

anyway everyone should read this book

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Press Release

Harvard Art Museums’ Fall 2023 Exhibition Explores

Entwined Histories of the Opium Trade and the Chinese

Art Market

Opium pipe, China, Qing dynasty to Republican period, inscribed with cyclical date corresponding to 1868 or 1928. Water buffalo horn, metal, and ceramic. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop, 1943.55.6.

Cambridge, MA

This fall, the Harvard Art Museums present an exhibition that explores the entangled histories of the western sale of opium in China in the 19th century and the growing appetite for Chinese art in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century. Opium and Chinese art—acquired through both legal and illicit means—had profound effects on the global economy, cultural landscape, and education, and in the case of opium on public health and immigration, that still reverberate today. Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade, on display September 15, 2023 through January 14, 2024 in the Special Exhibitions Gallery on Level 3 of the Harvard Art Museums, looks critically at the history of Massachusetts opium merchants and collectors of Chinese art, as well as the current opioid crisis.

A range of accompanying public programs will encourage community discussion around related topics, including the state of the opioid crisis in New England, the lingering political and economic effects of the Opium Wars, opium’s role in anti-Chinese U.S. immigration laws, and Chinese art collecting in Massachusetts. In addition, the artist collective 2nd Act will present a series of drama therapy workshops challenging ideas about addiction, and the Cambridge Public Health Department and Somerville Health and Human Services will host trainings on the use of naloxone (Narcan) to reverse opioid overdoses. In the early planning stages, Sarah Laursen, the Alan J. Dworsky Associate Curator of Chinese Art at the Harvard Art Museums, worked with Harvard students Emily Axelsen (Class of 2023), Allison Chang (Class of 2023), and Madison Stein (Class of 2024), who were instrumental in the development of the exhibition’s narrative and associated programming. Laursen also held a series of community feedback sessions to solicit reactions to the show’s content from Harvard students, faculty, and staff, as well as local experts and community members. Notably, the exhibition is opening during National Recovery Month, a national observance held each September to educate Americans about substance use disorder and the treatment options and services that can enable them to live healthy and rewarding lives.

“This exhibition is about the past and its impact on the present—but my hope it that it will also help us to think more productively about the future,” said Laursen.

“For example, the stigma around opium use initially resulted in the Qing government imposing harsh punishments for people experiencing addiction, rather than offering the empathy, treatment, and resources that people needed. Today, with overdose death rates in Massachusetts topping 2,300 individuals per year, we can learn from the past and choose to adopt harm reduction measures that will save lives.” On the collecting of Chinese art, Laursen notes, “By reexamining the formation of early 20th-century museum collections—as well as the underrecognized consequences of these initial acquisitions—we become better equipped to shape our policies for ethical collecting in the future.”

The exhibition comprises three thematic sections and presents more than 100 objects, including paintings, prints, Buddhist sculptures and murals, ceramics, jades, and bronzes, as well as historical materials including books, sale and exhibition catalogues, and magazine clippings from the collections of the Harvard Art Museums, with loans generously provided by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Fine Arts Library, Harvard-Yenching Library, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Houghton Library, and Baker Library (all at Harvard), as well as by the Forbes House Museum, the Ipswich Museum, and Mr. and Mrs. James E. Breece III.

Beginning with an examination of the origins of the opium trade, the first section includes a large comparative timeline that lays out events in China, Europe, and the United States in order to contextualize the complex histories of the opium and Chinese art trades. Britain began illegally selling Indian opium in China in the 18th century and increased its exports to counteract the demand for Chinese tea imports in Europe and the United States. In the 19th century, prominent Massachusett merchants such as members of the Perkins, Forbes, Heard, Cushing, Sturgis, Cabot, Delano, Weld, Peabody, and other elite local families were deeply involved in the lucrative Turkish opium trade as well. Conflicts between the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) and western powers over trading rights led to two Opium Wars (1839–42 and 1856–60), whose outcomes had far-reaching political and economic consequences.

In this first gallery, examples of typical Chinese export wares including tea wares, porcelains, and paintings that were popular in Europe and North America are presented alongside opium-related objects, including an opium pipe made of water buffalo horn and an opium account book for the year 1831 that lays bare the volume of the drug imported into the port of Guangzhou by just one firm, Russell & Co., run initially by members of Forbes family. A Qing dynasty painting of the Port of Shanghai (c. 1863–64), which became a commercial center after the first Opium War, shows a bustling harbor filled with boats and ships and reveals the location of the offices of prominent opium traders such as Russell & Co. and Augustine Heard & Co. Also visible is the headquarters of auctioneer Hiram Fogg, the brother of the China trader William Hayes Fogg, for whom Harvard’s Fogg Museum is named. Along with commerce, the first gallery also presents a range of documentary materials and ephemera that demonstrate the devastating impact of opium on Chinese society. Photographs and mass media illustrations critique the use and sale of opium. A slideshow, In Their Own Words, presents quotations from a diverse range of voices of individuals who were involved in or opposed the sale of opium and collecting of Chinese art. In many cases, these quotes flesh out the perspectives of historical figures who are named in labels throughout the galleries. Audio wands available in this space play excerpts from “Opium Talk,” an essay by Zhang Changjia (Shanghai, 1878) translated by Keith McMahon in The Fall of the God of Money: Opium Smoking in Nineteenth-Century China (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002).

The translations are read by Thomas Ho, a member of the local Chinese American community, and a transcript is available in the gallery, printed with permission from McMahon.

The second section highlights the history of imperial art collecting within China and demonstrates the growing appetite for Chinese art in Europe and the United States after the Opium Wars, especially after the looting of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing by British and French Troops in 1860 and in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901). Through the histories of merchants, collectors, dealers, museum directors, and professors, this section examines the early 20th-century formation of Chinese art collections in Massachusetts, including at the Fogg Museum. Chinese works from the collections of the Forbes House Museum and Ipswich Museum—once homes of opium traders of the Forbes and Heard families—show the taste at this time predominantly for functional or decorative objects such as export ceramics, lacquer furnishings, and other curiosities. However, the flood of newly available palace treasures and archaeological materials prompted the collecting of ancient bronzes and jades unearthed from tombs and Buddhist sculptures chiseled from cave temple walls.

Well-connected dealers in Asian art such as C. T. Loo (or Loo Ching-tsai) and Sadajirō Yamanaka 山中定次郎 acquired items from several sources—including from Chinese elites who fled the country after the fall of the Qing dynasty, imperial family members, and American collectors who lost their fortunes in the Depression—and sold those works to eager collectors around the world, such as Harvard alumnus Grenville L. Winthrop, who obtained 25 fragments from Buddhist cave temples in Tianlongshan, China.

The exhibition includes one work from this group, a sixth-century carved fragment depicting Bodhisattva Manjusri (Wenshu Pusa); to learn more about the Tianlongshan fragments now in the museums’ collections, visit hvrd.art/reframingtianlongshan. Others such as Langdon Warner, a Harvard alumnus and curator at the Fogg Museum, joined the First Fogg Expedition to China (1923–24) and personally removed works from the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, leaving permanent scars on the archaeological landscape of China. Two wall painting fragments, among the best preserved of the twelve that Warner brought back to Harvard, are displayed alongside a large-sale photograph showing the present condition of the mural from which they were removed (Bust of an attendant bodhisattva and Bust of a bodhisattva surrounded by a monk and devas).

Exhibition curator Sarah Laursen added: “I am often asked, where did this object come from? How did it come to Harvard? In many cases, we do not know their precise sources nor the circumstances of their removal because in the past there was no demand for documentation. For most U.S. collections of Asian art it is rarely possible to reconstruct the complete chain of ownership. But there are some questions we can start to answer: How can we work with source countries to better document, care for, and understand these objects? How can we curtail the black market? What could ethical collecting or sharing of cultural property look like in the future?”

A third section, entitled Opioids Then and Now, investigates parallels between China’s opium crisis and the opioid epidemic in Massachusetts today. Materials here clarify how addiction affects the brain (an animated video, produced for a free online Harvard edX course, plays on a monitor) and offer potentially life-saving information about harm reduction and overdose prevention. Visitors are invited to share their thoughts and personal experiences on response cards in this space and can either post them publicly on a bulletin board in the gallery or deposit them in a private box to be preserved in the Harvard Art Museums Archives. Visitors will also be able to browse recent books about opioids and harm reduction.

A 24-page printed booklet available in the galleries draws together the exhibition’s extensive content in three thematic essays: Who has benefited from the opium trade? Who has been harmed by opium?

What is the legacy of the opium trade in U.S. museums?

None of the works in the exhibition or in the Harvard Art Museums collections as a whole were collected or gifted by Arthur M. Sackler, nor were they purchased using funds provided by him.

Online Resource

Exhibition webpage: harvardartmuseums.org/objectsofaddiction

Public Programming

A range of public programs held in conjunction with the exhibition Objects of Addiction will encourage community discussion around the opioid crisis, the effects of the Opium Wars on U.S.–China relations, the role of opium in Chinese exclusion in the United States, and art collecting practices. Unless noted, all events are held in-person at the Harvard Art Museums, 32 Quincy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138.

Admission to visit our galleries is free, but some programs have a fee (noted below). For updates, full details, and to register, please click the links below or see our calendar:

harvardartmuseums.org/calendar. Questions? Call 617-495-9400.

Lecture — Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade

Thursday, September 14, 2023, 6–7:30pm

Join curator Sarah Laursen for a lecture on opium and Chinese art—two influential commodities traded in China, the British Empire, and Massachusetts between the 18th and early 20th centuries.

Free admission, but seating is limited and available on a first-come, first-served basis. Following the lecture, guests are invited to visit the exhibition on Level 3. This lecture will be recorded and made available for online viewing; check the link above after the event for the link to view.

Workshops — Rethinking Addiction: A Drama Therapy Workshop with 2nd Act Artist Collective

Saturday, September 16, 2023, 2–4pm

Sunday, October 22, 2023, 2–4pm

Saturday, November 11, 2023, 2–4pm

Drama therapists Ana Bess Moyer Bell and Amy Lazier of the artist collective 2nd Act will lead workshops designed to challenge participants’ ideas about addiction through a drama therapy model. By examining, embodying, and de-stigmatizing addiction and creating metaphorical objects of care, love, and support, participants will develop a shared understanding of addiction and how it affects daily life. $15 materials fee. Registration is required and space is limited. Minimum age of 14; no previous experience required.

Lecture — Objects of Addiction: Perspectives on the Opioid Crisis in New England

Sunday, September 24, 2023, 2–3:30pm

Specialists in addiction medicine, harm reduction, and public health policy will take part in a roundtable discussion about the current state of the opioid crisis in New England. Speakers:

Danielle McPeak, Prevention and Recovery Specialist, Cambridge Public Health Department; Leo Beletsky, Professor of Law and Health Sciences; Faculty Director, The Action Lab at the Center for Health Policy and Law, Northeastern University; Mark Joseph Albanese, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School; Medical Director, Physician Health Programs; former Medical Director for Addictions, Cambridge Health Alliance; Bertha Madras, Professor of Psychobiology, Harvard Medical School; Director, Laboratory of Addiction Neurobiology, and Psychobiologist,

Division of Basic Neuroscience, McLean Hospital; Jay Garg ’24, Policy Chair for HCOPES

(Harvard College Overdose Prevention and Education Students); and Dennis Bailer, Overdose Prevention Program Director, Project Weber/RENEW. Free admission, but seating is limited and available on a first-come, first-served basis. Before and after the discussion, guests are invited to visit the exhibition on Level 3.

Gallery Talks — Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade

Tuesday, October 3, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Wednesday, October 18, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Thursday, November 16, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Friday, December 1, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Wednesday, December 13, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Join curator Sarah Laursen for thematic 30-minute talks focused on select artworks in the exhibition. Free admission, but space is limited to 18 people and registration is required.

Narcan Trainings with the Cambridge Public Health Department and Somerville Health and Human Services

Tuesday, October 17, 2023, 5:30–6:30pm

Sunday, November 19, 2023, 2–3pm

Friday, December 1, 2023 (time TBA)

With an abundance of care for our community, the Harvard Art Museums are hosting one-hour on-site Narcan trainings, facilitated by the Cambridge Public Health Department and Somerville Health and Human Services. Their staff will also distribute the medicine for attendees to take home.

Naloxone (also known as Narcan) is a nasal spray that can rapidly reverse an opioid overdose by blocking opioids from attaching to receptors in the brain. Free admission, but space is limited and registration is required.

Exhibition Tours — Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade

Thursday, October 26, 2023, 12–1pm

Tuesday, November 21, 2023, 12–1pm

Saturday, December 9, 2023, 12–1pm

Join curator Sarah Laursen for hourlong tours of the exhibition. Free admission, but space is limited to 18 people and registration is required.

Online Lecture — Objects of Addiction: A Conversation about Opium and Anti-Chinese Immigration

Laws in the United States

Saturday, October 28, 2023, 10–11am

Award-winning author and Harvard history professor Erika Lee will be in conversation with two Harvard students about the role of opium in the restrictions on Chinese immigration in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. Speakers: Erika Lee, Bae Family Professor of History, Harvard University; Jolin Chan ’25, Harvard University; Student Board Member, Harvard Art

Museums; Madison Stein ’24, Harvard University. This talk will take place online via Zoom. The event is free and open to all, but registration is required.

Lecture — Objects of Addiction: The Legacy of the Opium Wars

Wednesday, November 8, 2023, 6–7:30pm

Harvard faculty in Chinese history, business, politics, and law will take part in a roundtable discussion on the 19th-century Opium Wars and the legacy of the opium trade in U.S.–China relations. Speakers: Mark C. Elliott, Vice Provost for International Affairs; Mark Schwartz Professor of Chinese and Inner Asian History, Harvard University; William C. Kirby, T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies, Harvard University; Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School; Rana Mitter, S. T. Lee Professor of U.S.–Asia Relations, Harvard Kennedy School; Meg Rithmire, F. Warren McFarlan Associate Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School; Mark Wu, Director of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University; Henry L. Stimson Professor of Law, Harvard Law School. Free admission, but seating is limited and available on a first-come, first-served basis.

Lecture — Objects of Addiction: Collecting Chinese Art—Past, Present, and Future

Saturday, November 18, 2023, 2–3:30pm

Curators and specialists will explore early collecting of Chinese art in Massachusetts, historical interpretations of cultural heritage, and how contemporary museum collecting practices have changed and will continue to change in the future. Moderator: Soyoung Lee, Landon and Lavinia Clay Chief Curator, Harvard Art Museums. Speakers: Nancy Berliner, Wu Tung Senior Curator of Chinese Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Amy Brauer, Curator of the Collection, Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art, Harvard Art Museums; Sarah Laursen, Alan J. Dworsky Associate Curator of Chinese Art, Harvard Art Museums; Lisong Liu, Professor of History, Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Free admission, but seating is limited and available on a first-come, first- served basis. Before and after the lecture, guests are invited to visit the exhibition on Level 3.

Credits

Support for Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade is provided by the

Alexander S., Robert L., and Bruce A. Beal Exhibition Fund; the Robert H. Ellsworth Bequest to the

Harvard Art Museums; the Harvard Art Museums’ Leopold (Harvard M.B.A. ’64) and Jane Swergold

Asian Art Exhibitions and Publications Fund and an additional gift from Leopold and Jane Swergold; the José Soriano Fund; the Anthony and Celeste Meier Exhibitions Fund; the Gurel Student Exhibition Fund; the Asian Art Discretionary Fund; the Chinese Art Discretionary Fund; and the Rabb Family Exhibitions Fund. Related programming is supported by the M. Victor Leventritt Lecture Series Endowment Fund. The accompanying booklet was made possible by generous support from Mr. and Mrs. James E. Breece III. Additional support for this project is provided by the Dunhuang Foundation.

About the Harvard Art Museums The Harvard Art Museums house one of the largest and most renowned art collections in the United States, comprising three museums (the Fogg, Busch-Reisinger, and Arthur M. Sackler Museums) and three research centers (the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, the Harvard Art Museums Archives, and the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis). The Fogg Museum includes Western art from the Middle Ages to the present; the Busch-Reisinger Museum, unique among North American museums, is dedicated to the study of all modes and periods of art from central and northern Europe, with an emphasis on German-speaking countries; and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum is focused on art from Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. Together, the collections include over 255,000 objects in all media. The Harvard Art Museums are distinguished by the range and depth of their collections, their groundbreaking exhibitions, and the original research of their staff. Integral to

Harvard University and the wider community, the museums and research centers serve as resources for students, scholars, and the public. For more than a century they have been the nation’s premier training ground for museum professionals and are renowned for their seminal role in developing the discipline of art history in the United States. The Harvard Art Museums have a rich tradition of considering the history of objects as an integral part of the teaching and study of art history, focusing on conservation and preservation concerns as well as technical studies. harvardartmuseums.org

The Harvard Art Museums receive support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Hours and Admission

Open Tuesday–Sunday, 10am–5pm; closed Mondays and major holidays. Admission is free to all visitors. For further information about visiting, including general policies, see harvardartmuseums.org/visit.

For more information, please contact

Jennifer Aubin

Public Relations Manager

Harvard Art Museums

617-496-5331

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (1/6/23) Kasamatsu Shiro (Japanese, 1898-1991) Night Rain at the Shinobazu Pond (1938) Polychrome woodblock print, 38.2 x 26.4 cm. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Cambridge MA

Kasamatsu Shiro was a Japanese engraver and print maker trained in the Shin-Hanga and Sosaku-Hanga styles of woodblock printing. Born in Tokyo in 1898, he apprenticed at the age of 13 to Kaburagi Kiyokata (1878–1973), a traditional master of Bijin-ga, pictures of beautiful women. Kasamatsu however took an interest in landscape and was given the pseudonym Shiro by his teacher, which he used as a signature mark in his prints. Kasamatsu made woodblock prints for the publisher Shozaburo Watanabe from 1919. Almost all the woodblocks were destroyed in a fire in Watanabe's print shop following the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kisokomagadake Ittchōgaike, Yamaguchi Susumu, 20th century, Harvard Art Museums: Prints

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Bequest of C. Adrian Rübel

Size: 54.3 x 39 cm (21 3/8 x 15 3/8 in.)

Medium: Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/199316

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unknown Indian Artist from Rajasthan, Victoria Maharani with the Princess Royal, ca. 1845, watercolor/paper (Harvard Art Museums - Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Cambridge)

That's right - this is a regional colonial portrait of Queen Victoria with her breasts out.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Richard Sackler graduated from medical school, Félix Martí-Ibáñez had tried to impress upon him the sort of esteem he would enjoy in life because he bore the Sackler name. This was only more true now, and perhaps nowhere more so than in London. The name was everywhere in the United Kingdom. There was the Sackler Building at the Royal College of Art, the Sackler Education Centre at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Sackler Room at the National Gallery, Sackler Hall at the Museum of London, the Sackler Pavilion at the National Theatre, the Sackler Studios at the Globe Theatre. In 2013, the Serpentine Gallery was renamed the Serpentine Sackler, with a gala opening co-hosted by Vanity Fair and the New York mayor, Mike Bloomberg (who was a friend of the family). One of the stained-glass windows in Westminster Abbey was dedicated to Mortimer and Theresa. It was decorated in lovely reds and blues depicting the seals of Harvard, Columbia, NYU, and other recipients of the family’s largesse. “M&T Sackler Family,” the window said. “Peace Through Education.” The Sacklers’ impulse to slap their name on any bequest, no matter how large or small, might have found its surreal culmination at the Tate Modern, the cavernous temple to modern art that occupies an old power station on the south bank of the Thames, in which a silver plaque informs visitors that they happen to be riding on the Sackler Escalator.

Patrick Radden Keefe, Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

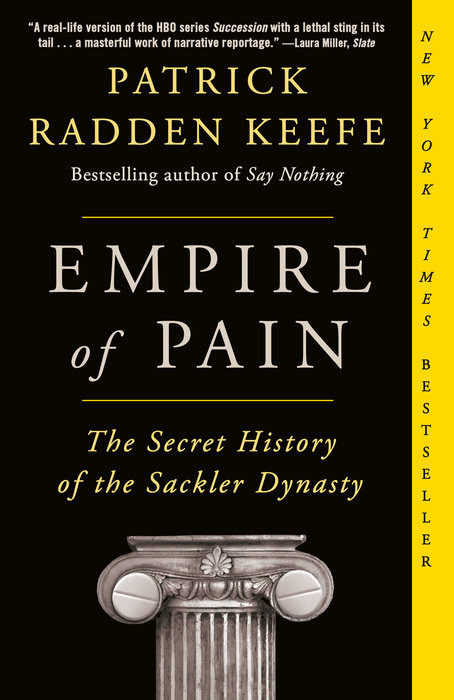

The Sackler name has adorned the walls of many storied institutions—Harvard, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oxford, the Louvre. They are one of the richest families in the world, known for their lavish donations to the arts and the sciences. The source of the family fortune was vague, however, until it emerged that the Sacklers were responsible for making and marketing a blockbuster painkiller, OxyContin, that was the catalyst for the opioid crisis.

Empire of Pain is the saga of three generations of a single family and the mark they would leave on the world, a tale that moves from the bustling streets of early twentieth-century Brooklyn to the seaside palaces of Greenwich, Connecticut, and Cap d'Antibes to the corridors of power in Washington, D.C. The history of the Sackler dynasty is rife with drama—baroque personal lives; bitter disputes; fistfights in boardrooms; glittering art collections; Machiavellian courtroom maneuvers; and the calculated use of money to burnish reputations and crush dissent. Empire of Pain is a masterpiece of narrative reporting—a grand, devastating portrait of the excesses of America's second Gilded Age, a study of impunity among the super elite, and an investigation of the naked greed and indifference to human suffering that built one of the world's great fortunes.

#book covers#patrick radden keefe#empire of pain#did the Chesterton epigraph convince me? perhaps#OxyContin

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stairway study

Cambridge, Massachusetts -- 12/15/12

#fotografía#fotografía original#original photography#photographers on tumblr#artists on tumblr#photography#sackler museum#stairs#stairway#escalera#harvard#harvard university

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Constellations (painting, recto and verso), folio from a manuscript of the Aja'ib al-Makhluqat by Qazwini. Yemeni. 1640 CE.

Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum.

#harvard art museum#Yemen#Yemeni#Yemeni history#art#culture#history#early modern period#early modern history#middle eastern history#painting#literature

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Byzantine Women and Their World October 25, 2002–April 28, 2003, Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums

1 note

·

View note

Text

Genre: Non-Fiction, Adult, True-Crime

Rating: 5 out of 5

Content Warning: Drug abuse, Addiction, Drug use, Suicide, Death, Antisemitism

Summary:

The highly anticipated portrait of three generations of the Sackler family, by the prize-winning, bestselling author of Say Nothing.

The Sackler name adorns the walls of many storied institutions: Harvard, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oxford, the Louvre. They are one of the richest families in the world, known for their lavish donations to the arts and sciences. The source of the family fortune was vague, however, until it emerged that the Sacklers were responsible for making and marketing OxyContin, a blockbuster painkiller that was a catalyst for the opioid crisis.

Empire of Pain is a masterpiece of narrative reporting and writing, exhaustively documented and ferociously compelling.

*Opinions*

As I always start when I am reviewing a non-fiction book, I can’t really talk about the topic that the author is covering because I haven’t spent years of my life researching it like they have. Also, non-fiction books, just like documentaries, provide the reader with facts, but that doesn’t mean those facts aren’t presented in a way to make people lean toward the same viewpoint as the author. All that being said, Patrick Radden Keefe did not have to do much to convince me that I hate all these people and wish them ill. In fact, if you have been following my updates it will be no surprise that the Tiktok sound of “why don’t we just kill these fucking people” played in my head a couple of times.

Empire of Pain chronicles three generations of the Sackler family and their rise from three brothers with MDs to billionaires who produced and peddled Oxycontin until the evidence against them was far too damning to continue. I vaguely remember this trail in the news cycle during 2020, but I also was attempting to avoid all news possible as someone who worked in a hospital, so I didn’t follow it with much interest. More rich people getting a slap on the wrist for doing something unimaginable, that really isn’t anything new. In fact, the actual business aspect of this novel was the least interesting for me. I am American, I am well aware that the country is five corporations and the NRA in a trench coat, so all the sleazy business practices were a given, though Keefe presented them in an easy to digest light. That didn’t mean that when I read about them paying the FDA, physicians, and lobbied in Washington to keep their names and the serious risks of the drugs away from the public didn’t surprise me. It’s a given that money talks, but it especially does in America. What I didn’t expect was how much I would hate the actual members of the family, especially the original three brothers.

While the Arthur Sackler branch of the family attempted to distance themselves from the Mortimer and Raymond branch when the bad press and their immoral dealings came to light, I found him probably the most detestable of the family. While Richard was horrible in his own right, he was born wealthy and so I almost expected him to think that he was God's gift to the world and refuse to take responsibility for what he believed was his gift to the world, oxycontin. Arthur, and his brothers, came from humble beginnings and lived through the Depression, which makes his absolute narcissism more shocking to me. I would figure that men who grew up around all that misery, they would have some compassion, but money is the best corrupter that has been invented. Arthur collected art and wives as if that was his profession, which was surprising given all the other professions the man had. It was comical that he thought that advertising to physicians was fine because they ‘wouldn’t be swayed by an ad’. He set up the framework that Purdue Pharma used to push Oxycontin across the United States and world, but he also got a whole generation of people taking tranquilizers with the same tactics. The audacity of the man was truly on another level and the fact that these men needed to put their names on ALL their Philanthropic efforts was slightly embarrassing. True, with the Carnegies, Rockefellers, etc, it was the same, but guess what it was embarrassing for them as well. Mortimer was what you would expect from someone who came into a lot of money, traveling the world and buying houses everywhere. Raymond was the only one who seemed able to be somewhat normal and have a single wife, well as normal as someone who is evil and owns an evil corporation could be anyway. Then again, Richard is his child, so I guess he couldn’t have been that normal.

The writing of this book was very accessible and wanted to keep me reading, even through the anger and frustration. I had read Say Nothing by Keefe, which had the same readable quality, and that book was part of the reason I picked this one up. I really didn’t have much of an interest in the Sacklers or the opioid epidemic, aside from how I encountered it at my job, but I had heard good things and I couldn’t put Say Nothing down, so I bought this. I am so glad that I did because even though this infuriated me, Keefe made sure that the voices of ‘normal’ people, individuals who attempted to raise concerns, people who became addicted, and those who advocated against the Sacklers were also heard. Nan Goldin had me internally cheering as she staged demonstrations at art galleries to pull the Sacklers out of obscurity and into the light of how they had gotten their billions of dollars. While it is frustrating that none of these people who lied, knew the risks, and still pushed their drugs will ever see jail, I am glad that the name that they were so insistent on being placed on everything had been removed again and again. May their deaths be painful and let them all die in obscurity.

Was this review anything except me screaming about these people? Not really. So,.let me try again. I think this is a fascinating read that pulls the curtain back not only on how one company led to an epidemic that we are still attempting to crawl out from underneath, but the family that tried so hard to hide in the shadows while it all happened. As Keefe states, they are hardly the only evil corporation or the only one selling opioids, but in regards to opioids, they were the first, the most aggressive, and if they weren’t the most irresponsible I would be shocked to learn who was. Keefe gives a look at the American legal system and what a joke that is if you have enough money, the few stalwart individuals who tried to do the right thing, and that at the end of the day you might not be able to take their money or reputation. If you don’t usually read non-fiction, I don’t think it is the first one I would point you to, but it was an engaging and fascinating read. 5 stars.

0 notes

Text

Apsara. China, Northern or Eastern Wei dynasty. 500-550 AD. Gilt bronze . Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University.

0 notes

Text

Empire of Pain by Patrick Radden Keefe (TL;DR)

Mini Book Reviews! originally from Books I Read in January 2023! 5/5 Stars ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ This is the story of the Sackler family and how they changed the world (for the worst). Their name was once the marque of many prestigious institutions around the world. Harvard, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oxford, and the Louvre once proudly displayed the Sackler name and accepted millions in donations from…

View On WordPress

#5 star books#6 months later reviews#adult books#america#audio book#audiobook#audiobooks#best books#best books 2023#best books of 2023#best books of 2023 so far#beth and books#bizarre reviews#book#book list#book of the month#book report#book review#book reviews#book wrap up#books#books i like#books of the month#books of the year#books to read#books to read in 2023#booktok books#business#canada#chuwi minibook review

1 note

·

View note