#SIMA 2017

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

肖顺尧 Xiao Shunyao as Sima Shi 司馬師 in The Advisor's Alliance (大軍師司馬懿之軍師聯盟 / 虎嘯龍吟)

This was the first role I saw him in way back in 2017, and I'd forgotten about him entirely until Mysterious Lotus Casebook, and I looked him and a lightbulb went off in my brain. "Oh, he was the hot son," I thought. (Sorry, TJC fans.)

I have always been of the thought that Yaoyao needs to grow out his beard, he does look quite good with a goatee.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Advisors Alliance Translation Post 2: “Husband, don’t cross the river. Husband, nonetheless, crossed the river.”

The Advisors Alliance 大军师司马懿之军师联盟 is a 2017 two-part Chinese TV series depicting the life of Sima Yi, a government official and military strategist who lived during the late Eastern Han Dynasty 东汉 (25 CE - 220 CE) and the Three Kingdoms Period 三国時代 (220 CE - 280 CE). [Wikipedia of the show’s first season]

The second part is titled Growling Tiger Hidden Dragon 虎啸龙吟 and keeps following Sima Yi’s life as he matures and becomes wiser [Link to the show’s second season’s MyDramaList page].

The Weibo account [Link] of the show made a series of posts in the style of small encyclopedias explaining different historical and cultural facts that where included in the series. The user @moononmyfloor compiled the 50 posts and asked me to translate them. This will be an ongoing series where I will do just that.

The posts are not in order of the episodes but I will provide the episode and season number to avoid confusion. If there are any mistakes in translation, do let me know in the comments or privately message me and I will do my best to fix them. Although I tried to stay as close as possible to the original text, I had to take some liberties in some posts to get the meaning across better. On the side, I have included extra information from personal research that explains certain things better.

If it is difficult to read the letters, tap or click on the image to expand it. Without more preamble, here you go.

Extra information:

Yuefu (乐府), literally Music Bureau, are a genre of ancient Chinese folk songs that, either imitate the style of, or are from the Imperial Music Bureau. The latter was an institution in charge of collecting and writing lyrics to folk songs. Yuefu are known for having strict syllabic rules that change from dynasty to dynasty.

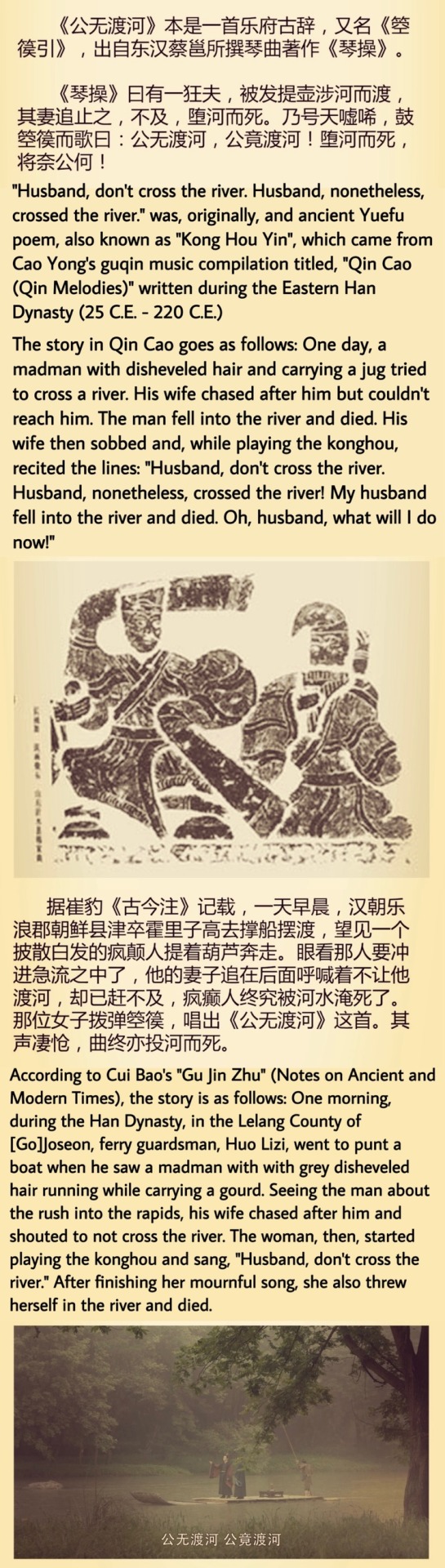

《公无渡河》 is also known as Kong Hou Yin (箜篌引). Konghou is an ancient Chinese stringed instrument similar to a harp. A Yin (引), in this context, is another type of ancient music poetry that has a freer syllabic structure and is characterized by long syllables that go well with the melody of the konghou. Below is a picture of the instrument:

Vertical konghou 箜篌 in exhibit at the Gansu Provincial Museum, Lanzhou, China. Taken on May 10, 2013 by Gary Todd [image source].

Allow me to clarify something. The folk song 《公无渡河》 was recorded by Cui Bao in "Notes on Ancient and Modern Times" to be of Gojoseon origin. As such, Koreans consider it to be their oldest surviving folk song.

The Chinese consider it a Chinese Han Dynasty song on account of the tale being set and song created in the Lelang Commandery [108 B.C.E. - 313 C.E.] which is one of the four regions Gojoseon was split into while under Han rule. Koreans consider the residents of Lelang, and the other commandaries, to be Gojosen Koreans who retained a separate culture to the Han Chinese. If you wish to conduct further research into the song, don’t get surprised if you read different names for the characters that appear in the story.

Koreans call the song "Gongmudohaga (공무도하가)” and the ferryman Gwaklijago (곽리자고). The Korean folk tale differs from the Chinese retelling in that the Korean name of Gwaklijago wife, who is credited with creating the actual song, according to certain Chinese and Korean retellings, is Yeo-ok (여옥) rather than Li Yu (丽玉). In Cao Yong and Cui Bao’s retellings, the wife of the drowned drunk man created the song while, in the Korean version, it was the wife of the ferryman who, upon learning about what had transpired from her husband once he came home, created the song on her harp, called in Korean gonghu (공후).

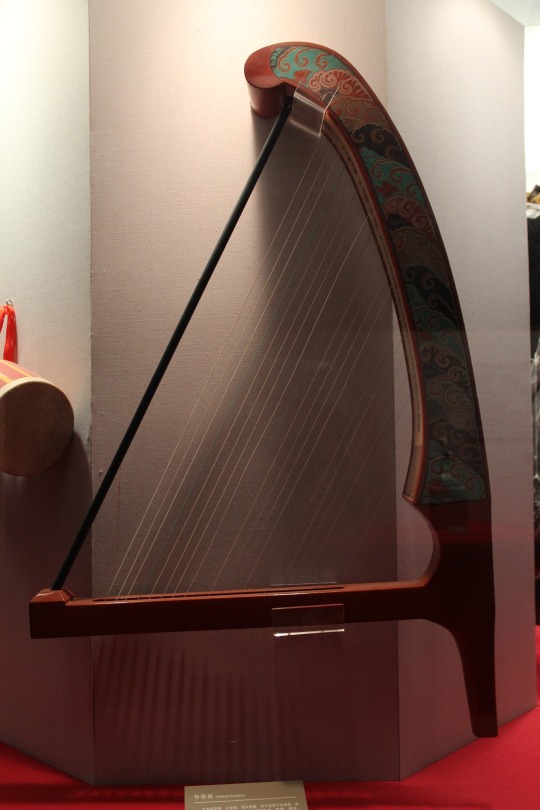

Many Chinese poets have retold the story in their own ways and added, omitted, or reinterpreted content. Some of said poets are Li Bai and Chen Shou of Shu Han. On top is Li Bai's version which lacks strict syllabic structure, a signature of his style and, on the bottom, Chen Shou's more structured one:

This expression 《公无渡河, 公竟渡河》 is often used as an allegory to satirize someone who is heading into clear danger but is too stubborn or obsessed to listen. If this person doesn't listen, then they are sure to run into trouble.

Catalogue (find the rest of the posts):

#chinese culture#chinese history#the advisors alliance#sima yi#history#three kingdoms#eastern han dynasty#korean folklore#li bai#chinese poetry#ancient chinese poetry#ancient china#gojoseon#korea

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

A volume with views of Chinese historians on the history of Western historiography

Herodotus, the founder of Western historiography, and Sima Qian, the greatest historian of ancient China

“History of Western historiography: The views from China—Introduction

Q. Edward Wang

Pages 73-78 | Published online: 04 May 2020

This issue presents a group of articles written by Chinese scholars on the tradition and transformation of Western historiography. Perhaps somewhat surprising to some of our readers, the subject is an important subfield in the garden of history in China. The course of “History of Western Historiography” or “History of Foreign Historiography,” for instance, is regularly taught to history majors on many college campuses. There are also specialists on the history faculty at several key universities who research and publish around the area and supervise students at both M.A. and Ph.D. levels. In fact, the majority of important historical texts constituting the tradition of European historiography from the ancient to modern periods have already had Chinese translations, readily available to Chinese readers and students. In more recent years, notable studies of the European/Western tradition of historical writing, its modern transformation and contemporary developments by scholars in the Western academe have also been rendered into Chinese. As a result, Chinese history students are familiar with major scholars in the field, such as Lynn Hunt, Peter Burke, Georg Iggers (1926–2017), Donald Kelley, Hayden White (1928–2018) and Frank Ankersmit. Indeed, in China’s historical circles, these scholars’ reputation rivals that of well-known China scholars in the West, such as Philip Kuhn (1933–2016), Frederic Wakeman (1937–2006), Jonathan Spence, Susan Mann, Timothy Brook and Benjamin Elman. And this trend of interest, in my opinion, would probably continue into the future. In January 2019, the Chinese government established the Chinese Academy of History (中國歷史研究院 Zhongguo lish yanjiuyuan) under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (中國社會科學院 Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan). Of its six departments, there is an Institute of Historical Theory (歷史理論研究所 lishi lilun yanjiusuo). Its task, needless to say, is to continue exalting the importance of Marxism as the theory in guiding historical research in China. Yet in order to promote the study of Marxism, which originated from the West, it is necessary for Chinese scholars to enhance their knowledge of Western historiography as well as to compare Marxist theory with other theoretical constellations advanced by Western scholars in both Marx’s times and more recent decades.

Looking around the world, it is not a uniquely Chinese phenomenon that the country’s history students and teachers accord substantial attention to Western academic cultures and historiographies. In his influential work, Provincializing Europe, Dipesh Chakrabarty, a prominent postcolonial theorist, has made the following observation:

This engagement with European thought is also called forth by the fact that today the so-called European intellectual tradition is the only one alive in the social science departments of most, if not all, modern universities.

As a result, Chakrabarty continues:

That European works as a silent referent in historical knowledge becomes obvious in a very ordinary way. … Third-world historians feel a need to refer to works in European history; historians of Europe do not feel any need to reciprocate. … “They” [Western historians] produce their work in relative ignorance of non-Western histories, and this does not seem to affect the quality of their work.1

Indeed, not only do historians in the West feel unnecessary to reference the histories of the rest of the world in their writings, but they also feel, as it were, irrelevant to pay attention to how historians outside Euro-America think and study of their history, or the histories of Europe and America. Given the rise of global history, the situation of the former is rapidly changing in recent years—comparative history and historiography, large or small in scope, are becoming increasingly attractive to historians in the West and their counterparts around the world. But no significant improvement has been made on changing the latter, or the indifference of Western historians toward the works of their counterparts in non-Western regions and countries. To a degree, this is perhaps not entirely the fault of Western historians. Concerning scholarly publication, its circulation and translation, there has been an asymmetrical relationship in our world: “Many of the important works in history or related social science and humanistic disciplines are translated from English into non-Western languages, as are important French and German books and articles. But very few Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Farsi, Turkish, or Arabic writings have been translated into English.”2 In other words, many valuable studies of Western history are inaccessible to Western historians as they are untranslated and unavailable. This, of course, also circulates back to the same question addressed earlier: while language proficiency is usually required for a proper training in history, many historians of Britain or the US, for instance, don’t feel the urge to learn a language other than English, which is in stark contrast to their counterparts in other countries and even their colleagues specializing in non-Western history.

All this accounts for the principal reason for editing this issue, which is to showcase some selected studies of Chinese historians on the history of Western historiography. Before moving on to discussing these articles, I think a brief review of the origin and development of Western historiography in China is in order. In China’s long tradition of historical writing, which spanned about two millennia before modern times, it was customarily for historians to record about their neighbors in the surround. Their approach to the writing, however, was ethnocentric, in that they regarded China as the “Middle Kingdom” that radiated its influence, or civilization, outwardly to the neighboring regions. Throughout the period of imperial China, as Ge Zhaoguang, a noted intellectual historian and a frequent contributor to this journal, observes, the idea of “the central empire as the principal, the peripheries as subordinates,” which was formulated by Sima Qian (c. 145–86 BCE) in his magisterial Records of the Grand Historian (���記Shiji), was the guiding principle for Chinese historians to write about the relationship between “China,” or whatever a regime that occupied the Central Plain in a given time, and its relation to and position in the known world. During the long period, Ge avers, there emerged three opportunities for Chinese historians to develop a different worldview, but it was not until the end of the nineteenth century, after a series of defeats the then ruling Qing dynasty (1644–1911) suffered in battling Western powers, that a fundamentally new approach was adopted. This approach was characterized by the full recognition of the development of a multipolar world in modern times, of which China was a part but not the center. As such, it became necessary for Chinese historians to learn and write about the much-expanded world beyond the Sinitic sphere.3

In this newly acquired worldview, the West figured centrally, for it was largely due to the Western powers’ challenge that sufficiently pained Chinese to realize their modern woes as a nation. And from the mid-nineteenth century throughout the twentieth century, this Western-centered worldview persisted, despite the drastic changes happening in the political arena. So much so that in the minds of Chinese students today, “History of Western historiography” is by and large equivalent to “History of foreign historiography.” And, indeed, if one looks and compares the syllabi of the two courses taught in China’s colleges, one often finds that there are substantial overlaps between them, even though the latter is supposed also to cover historical practices in Asia, Africa, South Asia and Latin America. In fact, as shown in Zhang Guangzhi’s article in this issue, the course of “History of Western Historiography” is taught more frequently than its counterpart, “History of Foreign Historiography,” in Chinese universities. Zhang, a seasoned scholar who has witnessed as well as participated in the expansion of the field over the past several decades, also chooses to concentrate his discussion on the teaching of “History of Western Historiography” in the PRC.

As an academic field, the development of the history of Western historiography began only a half century ago in China. Yet from the late nineteenth century, some Chinese historians had already taken an interest in learning about how history was written in the West. In his Pufa zhanji (普法戰紀 Report on the Franco-Prussian War), for example, Wang Tao (王韜 1828–1897), who had gotten an opportunity of sojourning in Scotland while assisting James Legge’s (1815–1897) translation of Chinese Classics, not only recorded the War that led to the German unification, but he also experimented with new ways in constructing his narrative by drawing elements from Western historiography. From the early twentieth century, buoyed by Liang Qichao’s (梁啟超 1873–1929) call for making a “historiographical revolution” (史界革命 Shijie geming), more attempts were made to translate works of Euro-American historians on the nature and methodology of history. He Bingsong’s (何炳松1890–1946) translation of James Harvey Robinson’s New History and Li Sichun’s (李思純 1893–1960) rendition of Charles-Victor Langlois’ and Charles Seignobos’ Introduction aux études historiques were well-known examples at the time.4

Both He and Li were returned students from the West. For the advance of Western historiography as an academic field in China, students with an educational background similar to theirs were forerunners. But the opportunity to formally introduce it into the college curriculum did not occur until 1961, after China, now ruled by the Communists, suffered from the disastrous Great Leap Forward Movement launched by Mao Zedong (1893–1976) in 1958. Perhaps for assuaging the pain and suffering of the Chinese people (the educated Chinese had fared worse because they were severely chastised in the Anti-Rightists Campaign waged by Mao, almost simultaneously as he commanded the Great Leap Forward) had experienced in the previous decade, the Chinese government introduced several projects in the 1960s that permitted, if also covertly encouraged, Chinese historians to find alternatives to the Soviet model of historiography, for, by that time, the honeymoon between Communist China and the Soviet Union had ended. It is perhaps worth noting that in his call for taking the Great Leap Forward, Mao’s hope was for China to catch up with the UK and US, not the USSR. In any case, what transpired was that a group of Western-educated Chinese historians was invited to a meeting held in Shanghai in 1961 by the Department of Education, discussing the likelihood of teaching the course on “History of Western Historiography” and composing a textbook. Motivated by the meeting, some of them also published journal articles in its wake on the need for developing the course and gaining knowledge on Western historiography for history students in China.5

Due to the interruption of the Cultural Revolution, which took place only a few years after but lasted for a decade, Western historiography as a bourgeoning field failed to take root in the 1960s. It was not until the 1980s that its research and teaching were resumed. By the time, most scholars who had received education in the West were already in the retirement age—some had even already passed away. Yet the survivors cherished the hard-earned opportunity and renewed their enthusiasm for plowing and establishing the field. Again, as covered by Zhang Guangzhi’s article, some of the pioneering studies, including valuable translations, of Western historiography were produced by these Western-educated historians from the period, such as Geng Danru (耿淡如 1897–1975), Wu Yujin (吳于廑 1913–1993), Guo Shengming (郭聖銘 1915–2006) and Zhang Zhilian (張芝聯 1918–2007), whose works laid the foundation for historians of younger generations to continue expanding the field to this day.

The importance of the aforementioned scholars, too, is shown that most of the articles sampled here were written by their students and/or students of their students. Wu Xiaoqun, the author of the first article, for instance, worked with Zhang Guangzhi in earning her Ph.D. degree, and Zhang had been a graduate student of Geng Danru during the Cultural Revolution. Taking the recent disputes on Herodotus regarding his “father of history” status as a point of departure, Wu, a professor of history now at Fudan University in Shanghai where Geng and Zhang both worked before, offers her defense of Herodotus as a bona fide historian. She acknowledges the value of recent scholarship on Herodotus, as it offers a much more in-depth analysis of the cultural “context” in which Herodotus worked on his Histories. Meanwhile, she emphasizes that while he inherited the genre of Historia from earlier Greek writers, Herodotus made a great improvement on it in his writing. “Although the “historia” method was not his original invention,” Wu argues, “nor did he elevate it into a theoretical or systematic proof, he [Herodotus] did nonetheless make it the most important method of narration. Since Herodotus, everyone who studies past events in human history and everyone who studies changes in society all add their own judgments and interpretations.” By and large, Wu champions the view advanced by such historians as Arnaldo Momigliano (1908–1987) that modern historiography indeed had “classical foundations.” In her opinion, recent studies of Herodotus in the West have overemphasized Herodotus’ cultural inheritance while overlooking the paradigmatic influence of the Histories in developing European historiography.

Li Longguo contributes the second article to this issue on the transition from ancient to medieval historiography in Europe. A specialist in the history of the Middle Ages at Peking University, where Zhang Zhilian used to teach, Li has made an interesting observation of the transition. As shown by its title, “From ‘Walking’ to ‘Sitting’: Changes in the Practices of Western Historiography From Ancient to Medieval Times,” Li’s article compares the different research styles adopted by ancient and medieval historians. In ancient Greece, he writes, as exemplified by Herodotus and Thucydides, followed also by Xenophon, historical writing was mostly drawn on eyewitness experiences; those Greek historians usually collected information for their writings by personally traveling to the places where historical events had taken place. By comparison, Roman historians like Livy and Tacitus began to use materials already collected in the imperial library; they no longer “walked” as much as their Greek predecessors had. Then in the Middle Ages, historical records were mostly produced by Christian monks who tended to lead a solitary and sedentary life in the monastery. That is, they seldom “walked” to gather source materials but instead they “sat” in the library where they went through its source collections for their writing. This evolution of research style, Li opines, also unveiled a change in epistemology: ancient historians “walked” to locate the sources for ensuring their factuality whereas medieval historians believed that their religious faith could guarantee the truthfulness of their records.

The third article is written by Zhang Yibo, a Ph.D. candidate in the History Department of Peking University. His research focuses on a key moment in the development of European historiography into the modern age. In the so-called “Age of Discovery” of European history, Zhang finds, the tradition of universal-history writing experienced a notable change—after discovering the Americas, European historians embarked on the task of expanding their horizons in perceiving the world. The multivolume Universal History, compiled chiefly by George Sale (1697–1736) but assisted by many others, was a prime example. Appearing in the mid-eighteenth century, Zhang finds, this massive book of sixty-five volumes contained many fresh ideas that were unseen before. However, no sooner had it become a commercial success than it received harsh criticisms, for, in the eyes of the historians who then already aspired to turn history into a science, such as August Ludwig Schözer (1735–1809), Sale’s work was a mere assemblage of unscrutinized materials, lacking the commitment for ascertaining their credibility. Consequently, in Zhang’s words, “the kind of encyclopedic history writing model represented by Sale’s Universal History was a tradition that gradually disappeared following the professionalization and scientificization of historiography.” His study thus offers a specific case that documented the transformation of modern European historiography.

In developing scientific historiography in Europe, German historian Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) evidently played an instrumental role, well recognized by many experts in the West. Over the centuries, a great number of works have been published on Ranke and his influence as the “father of modern scientific historiography.” In his article, “Equal Emphasis on ‘Research’ and ‘Representation’: A New Analysis of Ranke’s Debut Work,” Lü Heying, who teaches at Sichuan University, offers a close-up examination of Ranke’s two Prefaces to the First Edition of the Geschichten der Romanischen und Germanischen Völker von 1494 bis 1515 (Histories of the Latin and Teutonic Peoples from 1494–1514). The Prefaces are important because in which Ranke declared that while previous historians sought in history political idealism and moral didacticism, his writing of the book was merely for telling history “wie es eigentlich gewesen,” or “as how it actually was.” Engaging critically with some of the recent Western publications, such as that by J.D. Braw and Jörn Rüsen in History and Theory,6 Lü argues that for a better understanding Ranke’s well-known statement, one needs to conduct an in-depth reading and textual analysis of the two Prefaces as well as the appendix to the work, Zur Kritik Neuerer Geschichtschreiber (Criticisms of modern historians). He believes that all of them holistically as an organic system that addresses not only what Ranke desired to accomplish in his writing but also how he devised his research method and his style of presentation.

Li Hongtu, our fifth contributor, is a professor of European intellectual history at Fudan University where Lü Heying received his Ph.D. In recent years, Li has published extensively on the modern, postwar trends of intellectual history, centering around the works of Quentin Skinner and Reinhart Koselleck (1923–2006). In this article, he traces the origin of the history of ideas as defined and advanced by Arthur O. Lovejoy (1873–1962) in the prewar period and proceeds to discuss the vicissitudes of its change from the second half of the twentieth century. He notes that the changes stemmed from a wide range of new interests among the practitioners. Due to the “linguistic turn,” intellectual historians developed a focus on context, rhetoric, actions, etc., whereas the growing influence of sociocultural history also prompted them to look into the relationship between ideas and social contexts. Last but not least, echoing the march of globalization, the “spatial turn” has now emerged in the field as well. As a result, Li believes, there is no decline of the history of ideas as a field, but historians have since expanded its boundary and enriched its research paradigms. He himself points out a few cases that call for historians, Western and Chinese alike, to note how the intellectual variances in China could help produce new and different understandings of certain well-received concepts in the field.

The sixth article is written by Huang Yanhong who, after obtaining his Ph.D. from Peking University, worked at the World History Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences for over a decade. He is now a professor of European history at Shanghai Normal University. Having commanded several European languages and translated a number of works from French, English and German into Chinese, Huang has also written extensively on modern historiography and intellectual history in Europe. In this article, he offers a detailed analysis of Pierre Nora’s “Lieux de Mémoire” concept and project and their international influence. His aim is to explore the transformation of historical consciousness and historical writing in postwar France. Nora’s introduction of the project, which incidentally has been translated into Chinese at present,7 according to Huang, reflected the changing intellectual milieu, which gave rise not only to New National History, but also to the idea of “presentism” (présentisme). As such, Huang maintains, while Nora’s project (as he himself admitted) was specific to France, it has far-reaching implications for contemporary historiography in both Europe and beyond.

Zhang Guangzhi, mentioned earlier, provides the seventh and last article for this issue. A professor emeritus of history at Fudan University, where he spent his entire career of over forty years, Zhang is a well-known expert on Western historiography in China. Over the decades, he has trained a number of students in the field, many of whom have also become established scholars (e.g., Wu Xiaoqun). In writing this review article, Zhang observes that the development of the Chinese study of Western historiography went through three major periods in the twentieth century and the progress in the third period, beginning from the late 1970s after China was ushered in the “Reform and Open-up” era, has been most impressive. And, as I point out at the beginning of this introduction, this trend of growth will likely continue in the years to come.

All in all, I believe, editing this issue can help our readers to see the other side of the recent and robust globalization of history writing—as historians in the West are searching for ways to expand their research horizons, their counterparts in the other hemisphere have also been working on enhancing their knowledge of Western history and historiography. In his thought-provoking work, Global Perspectives on Global History, Dominic Sachsenmaier, a noted global historian at the University of Göttingen who serves on our editorial board, observes sharply that for the future expansion of global history, it is necessary for Western historians to diversify their outlooks and augment their knowledge base. For “much of global history in Europe and North America,” he aptly notes, “remained more characterized by a rising interest in scholarship about the world rather than scholarship in the world” (italics original).8 While a rather small step, I hope this issue will make a contribution to reaching this goal by stimulating more interest among our readers in Chinese scholarship on the West and the world.

Notes

1 Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 8, 28.

2 Georg Iggers, Q. Edward Wang and Supriya Mukherjee, A Global History of Modern Historiography (London: Routledge, 2017), 312.

3 Ge Zhaoguang, “The Evolution of World Consciousness in Traditional Chinese Historiography,” a keynote speech delivered at the international symposium on “The Conceptions of the World in Twentieth-century China” at the University of Göttingen on October 26, 2017. See also his What Is China? Territory, Ethnicity, Culture, and History, trans. Michael Gibbs Hill (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2018); and Q. Edward Wang, “History, Space and Ethnicity: The Chinese Worldview,” Journal of World History, 10, no. 2 (Sept. 1999), 285–305.

4 For a general discussion of the origin of modern Chinese historiography and its connection with the West, see Q. Edward Wang, Inventing China through History: The May Fourth Approach to Historiography (Albany: SUNY Press, 2001).

5 Besides Zhang Guangzhi’s article in this issue, Chen Heng also discusses the development of the history of Western historiography in his “Xifang shixueshi de dansheng, fazhan jiqi zai Zhongguo de jieshou” (The Origin and development of the history of Western historiography and its acceptance in China), Shixueshi yanjiu (Journal of historiography), 2 (2016), 56–66. For a discussion in English, see Qingjia Wang, “Western Historiography in the People's Republic of China (1949-to the present),” Storia della Storiografia [History of Historiography], 19 (1991), 23–46.

6 J. D. Braw, “Vision as Revision: Ranke and the Beginning of Modern History,” History and Theory 46, no. 4 (2007), 45–60.

7 Sun Jiang, a professor of history at Nanjing University, is in charge of the translation project, which is expected to complete in 2021.

8 Dominic Sachsenmaier, Global Perspectives on Global History: Theories and Approaches in a Connected World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 4. Also, Sven Beckert and Dominic Sachsenmaier, eds., Global History, Globally: Research and Practice around the World (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

Source: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00094633.2020.1743162?src=recsys

Introduction to “History of Western historiography: The views from China”, in Chinese Studies in History, Volume 53, Issue 2 (2020), Routledge

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern klasszikus, a városi motorosoknak: Triumph Trident 660 2024 teszt - VIDEÓVAL!

Mindig is szerettem volna kipróbálni egy Triumph csoda motort, de nem nagyon találtam szájízemnek megfelelőt. A mindennapokban egy 2017-es Honda CB500F motort hajtok, mert nagy kedvenceim a naked motorok. A várakozásom beteljesülése 2024. júliusában tetőzött, amikor lehetőségem adódott a győri Triumph márkakereskedés jóvoltából, egy Trident 660 modellt megkaparintani hétvégére. A szükséges papírmunka után lelkemre kötötték, hogy még bejáratós a motor így 5000-es fordulatszámot ne nagyon haladjam meg. Ez először ijesztőnek hatott, azonban rájöttem a túrám során, hogy a papíron 80 LE-s (64 Nm) motor alsó tartományban is olyan dinamikusan és fürgén mozog, hogy öröm volt vezetni. Alacsony fordulaton is éppúgy magabiztosan lehetett haladni a sorok között vele, mint kint, a városon kívüli utakon. A 2024-es Trident 660 közvetlen elődje a 2021-ben bemutatott Trident 660, amely a Triumph modern középkategóriás motorjának úttörője volt. Nézd meg a videót is! https://youtu.be/JtA_RbB9lVU A Trident 660 dizájnja ötvözi a klasszikus Triumph stílust a modern elemekkel. A lekerekített formák, a minimalista fényszóró és a stílusos grafikai elemek a motorkerékpárt egyszerre elegánssá és agresszívvé teszik. Az új színválaszték és a frissített grafikák a 2024-es modellnél különösen vonzóak. Az új modell tervezésénél cél volt egy könnyen kezelhető, mégis teljesítményorientált motorkerékpár létrehozása, amely a kezdőktől a tapasztalt motorosokig mindenki igényeit kielégíti. Ez szerintem abszolút sikerült is nekik! A 660 köbcentis, háromhengeres motor sima teljesítményleadást biztosít, a hatsebességes váltó pontos volt és könnyen kezelhető. A Showa felfüggesztés (41 mm-es fordított első villa és monoshock hátsó rugóstag) kiváló stabilitást és kényelmet biztosít, mint említettem, legyen szó városon belüli közlekedésről vagy kanyargós hegyi utakról. A Trident 660 első és hátsó fékei is Nissin gyártmányúak, dupla 310 mm-es tárcsákkal az első keréknél és egy 255 mm-es tárcsával a hátsónál. Az ABS rendszer alapfelszereltség, ami növeli a biztonságot és a vezetési élményt. Az ergonomikus ülés és a kényelmes üléspozíció hosszabb utak során is kényelmes marad. A digitális műszerfal jól látható, könnyen olvasható, és legfőképpen könnyen kezelhető. Az elektronikai felszereltség (ABS, kipörgésgátló, két menetmód) és a kiváló fékrendszer jelentős mértékben növeli a biztonságot. Az új modell finomhangolt elektronikai rendszerei még jobb vezetési élményt nyújtanak. A motor üzemanyag-fogyasztása átlagosan 4,5-5,0 liter/100 km körül alakul, ami jó eredménynek számít ebben a kategóriában. Szerintem a Triumph versenyképes áron kínálja ezt a kis modern paripát, a kiváló teljesítményt és a stílusos dizájnt. Az ár-érték aránya kifejezetten kedvező a középkategóriás motorok piacán. A Trident 660 rendszeres karbantartást igényel, mint minden modern motorkerékpár. Az olajcserék és a szelepállítások a gyártó által ajánlott intervallumok szerint szükségesek. A gumik, fékbetétek és olajok a szokásos karbantartási elemek közé tartoznak. A Michelin Road 5 gumik és EBC fékbetétek kiváló választás a Trident 660-hoz. A motor megbízhatónak bizonyult, de érdemes figyelni a láncfeszítésre és az elektromos rendszerek állapotára. Az alkatrészellátás jó, és a Triumph hivatalos kereskedői hálózatán keresztül gyorsan beszerezheted a szükséges alkatrészeket. Az árak versenyképesek, bár néhány speciális alkatrész azért drágább lehet. Összeségében a Triumph Trident 660 egy kiváló választás mindazoknak, akik egy stílusos, könnyen kezelhető, mégis teljesítményorientált motorkerékpárt keresnek a mindennapi használatra és a hosszabb túrákra egyaránt. TRIUMPH TRIDENT 660 MŰSZAKI ADATOK: - Lökettérfogat: 660 cm³ - Furat x löket: 74 x 51,1 mm - Kompresszió viszony: 11.95:1 - Max. teljesítmény: 80 LE 10,250 1/min - Max. nyomaték: 64 Nm 6,250 1/min - Max. sebesség (1 személlyel): 200 km/h - Váltó: Hatsebességes, lánchajtás - Kuplung: Könnyített, csúszókuplung - Üzemanyag ellátás: Elektronikus üzemanyag-befecskendezés - Első futómű: Showa 41 mm-es fordított villa - Hátsó futómű: Showa monoshock rugóstag - Első fék: Két 310 mm-es tárcsa, Nissin féknyergek - Hátsó fék: Egy 255 mm-es tárcsa, Nissin féknyereg - Kerekek (e/h): Alumínium ötvözet felnik - Gumik (e/h): Michelin Road 5 (120/70 R17 elöl, 180/55 R17 hátul) - Hossz x szélesség x magasság: 2020 x 795 x 1085 mm - Ülésmagasság: 805 mm - Tengelytáv: 1407 mm - Üzemanyag tartály: 14 liter - Útrakész tömeg (benzin nélkül): 189 kg - Ára: 3,499,000 Ft-tól Read the full article

0 notes

Text

"Balneário Camboriú é a cidade que concentra o maior número dos edifícios que estão entre os mais altos do Brasil. Grande parte deles, no entanto, ainda está em fase de obra, o que faz do Infinity Coast Tower, entregue neste sábado (14), o primeiro residencial do país com obras concluídas a constar nesta lista. Assinado pela FG Empreendimentos, o edifício foi o primeiro a passar da linha dos 200 metros de altura (são 234 m, exatamente) quando de seu lançamento, em 2017, com projeto de engenharia de Gustavo Simas. Hoje, esta marca já foi superada por vizinhos como o One Tower (263 m), também da FG Empreendimentos, e o Yachthouse by Pininfarina (281 m), do Grupo Pasqualotto & GT, todos em fase de obras no litoral catarinense." "Para a construção do Infinity Coast foram necessários 25 mil m³ de concreto, cujo transporte utilizou aproximadamente 2,5 mil caminhões betoneira. Durante o pico de obra, um total de 1,5 mil funcionários trabalharam simultaneamente no canteiro. Foram utilizados, ainda, duas mil toneladas de aço, 700 km de cabos elétricos, 46 km de tubulação hidráulica, de abastecimento de água e do sistema preventivo e esgoto. A profundidade da fundação equivale a um prédio de 15 andares. No total, são 66 pavimentos, 115 apartamentos (dois por andar) e 47,5 mil m² de área construída."

0 notes

Text

Palazzo Presta, un Boutique hotel di charme dall’animo nomade

A Palazzo Presta, nel Salento, lo studio di progettazione milanese Atelier P richiama il fascino del viaggio con elementi eclettici e senza tempo. Si può viaggiare restando fermi. Accade a Palazzo Presta, Boutique hotel di charme a Gallipoli, in Salento, trasformato da Atelier P in una stazione obbligata per i globetrotter, invitati ad attraversare una piccola porta per trovare un grande percorso su più livelli: temporale, architettonico, emozionale.

Storia e ristrutturazione di Palazzo Presta

Appartenuto nel Settecento al medico e agronomo Giovanni Presta, nel 2017 l’edificio conosce una nuova destinazione d’uso senza dimenticare lo spirito che animava questo luogo. Un tempo l’antico proprietario apriva le porte ai suoi concittadini per dispensare cure e consigli. Nel progetto di ristrutturazione dello studio milanese, quel senso di protezione e relax torna ad albergare tra le antiche pareti richiamando turisti da ogni parte del mondo. Gli Architetti Mattia Pareschi e Luca Piccinno, e l’interior decorator Alessandro Mario Cesario, intervengono a consolidare le strutture, i solai, fanno riaffiorare il tufo pugliese, valorizzano le volte, creano volumi che dialoghino con quelli originali.

Il risultato è un esempio di hospitality dal sapore internazionale che sedimenta l’idea di un percorso a ritroso, nella storia del territorio e in quella personale di ciascun ospite, grazie a tessuti, colori, in un’architettura lineare e ricca di dettagli che si mescola a oggetti di design nomade che offrono una sintesi geografica del globo. Palazzo Presta si presenta come un hub creativo dove Atelier P riesce a far abitare “il viaggio” solo guardandosi attorno.

Dieci camere, ciascuna con la propria personalità e tonalità

Le dieci camere, distribuite su due piani, sono mappe eccentriche, ciascuna con un proprio nome e una propria personalità, offrono ricordi e suggestioni in ordine sparso, solo apparentemente casuale. Perché ogni dettaglio è studiato, composto, perfino disegnato per una personalizzazione massima dell’ambiente. Un concept realizzato da mani artigiane del luogo, cui Atelier P guarda come plusvalore e necessaria cultura d’impresa.

Così, testate e letti escono dalle “officine” di TAULA INTERIORS, mentre le lampade in tessuto – lampadari, applique e abat jour in stile art déco - sono di MAURIZIO BELLACCI. Quelle in vetro portano la firma di New Fashion Glass. I rivestimenti degli imbottiti e le tappezzerie arrivano da archivi di importanti tessiture a garanzia di unicità.

Mix di materiali antichi e contemporanei

La scala principale in pietra leccese è stretta tra muri trattati con la velatura per far emergere tono e valore delle preesistenze. Sempre al piano terra, il vano ascensore è costruito ex novo e guarda una volta in cemento armato, innesto che sottolinea la relazione tra storico e contemporaneo nel progetto di restyling.

La matericità è un nervo da scoprire in ogni angolo, si rivela nei pavimenti di cementine, originali all’entrata o nuove, di MARRA pavimenti, con decorazioni diverse per ciascuna camera La scelta delle velature garantisce quel sapore di vissuto che permette ad ATELIER P di azzardare con colori e texture dall’effetto tattile.

I bagni sono cubi immessi nello spazio, forme basiche che esaltano l’espressività delle volte e creano un’originale sequenza di forme. I sanitari, classici, li porta SIMAS. FIAS cura serramenti e lavori in ferro.

Terrazza e rooftop di Palazzo Presta

Il racconto di questa fascinazione per un interior che sia insieme nostalgia e modernità, prosegue anche all’esterno di Palazzo Presta. Per la terrazza comune, al primo piano, Atelier P utilizza vasi di manifattura locale riempendoli con palme di grandi dimensioni come sostenibile separé. Al livello superiore, oltre alle camere, si apre il rooftop vista mare, la terrazza LAURUS, un’esperienza per gli occhi e il palato. Nella stagione estiva è qui che si trasferiscono le colazioni, che si apprezza quell’atmosfera da vecchio club per viaggiatori.

L’anima in acciaio Corten del Bar rimanda al volto ricercatamente délabré del palazzo e il bancone in marmo Emperador all’eleganza senza tempo. Uno spazio en plein air con divanetti in okume’ e panchine in tufo salentino dotate di cuscini a strisce bianche e marroni che ricordano le sdraio degli anni Settanta. Completa l’intramontabile Peacock, qui nella versione in nero, ispirata alla seduta inglese Windsor. E se proprio non si vuole scendere in spiaggia, il viaggio prosegue sull’altana, comodamente adagiati sui lettini del solarium, stesso motivo a righe, stesso comfort. www.palazzopresta.it Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cinco leituras para refletir sobre as cidades (e sair caminhando)

[Originalmente publicado em 18/03/2019 aqui]

Na semana passada, falei sobre a Feira Cartográfica que rolou no fim de semana que passou no Sesc Pinheiros e me peguei pensando em alguns livros deliciosos e/ou informativos sobre nossa vida nas cidades e a relação que estabelecemos com elas. Fiz uma pequena lista com cinco deles, de tipos variados — tem crônica, guia, sociologia, história — e enfocando lugares distintos, para inspirar caminhadas por aí.

"O meu lugar" (ed. Mórula, 2015)

Livro delicioso para os andarilhos, reunindo crônicas sobre diversos bairros e cantos do Rio de Janeiro, com os autores escrevendo sobre seus pedaços, de coisas que os emocionam a relações da infância, de trajetos de ônibus a memórias de família. Tem o Irajá de Nei Lopes, tem a Copacabana de Luiz Antonio Simas (um dos organizadores), tem São João de Meriti de Bruna Beber, tem a Tijuca de José Trajano. Enfim, um jeito bem delicioso de ler sobre o Rio.

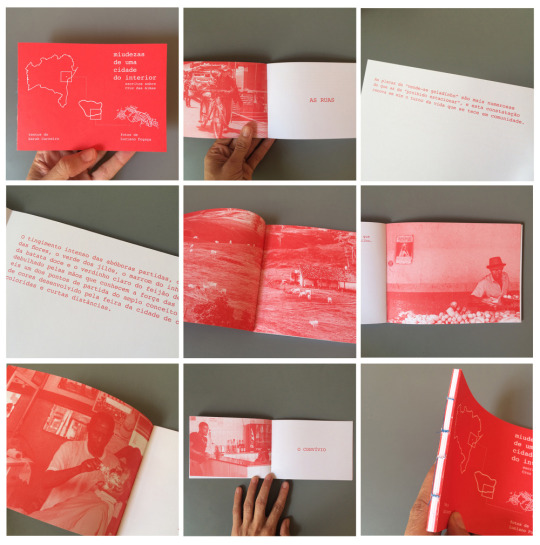

"Miudezas de uma cidade do interior" (Conspire Edições, 2017)

Livro delicado, editado com capricho, com escritos sobre a rotina, a vida em uma pequena cidade baiana chamada Cruz das Almas. A dimensão humana do dia a dia, o convívio, ganham destaque nas observações da autora Sarah Carneiro: da venda de geladinho, as cores da feira que tingem o cenário. Ilustrado com fotos de Luciano Fogaça.

"Escritos urbanos" (editora 34, 2000)

O livro reunindo artigos escritos entre 1985 e 2000 pelo cientista político Lúcio Kowarick é uma oportunidade de pensar as transformações da cidade de São Paulo a partir de sua dimensão política e social, com reflexões sobre moradia, produção de periferias, movimentos ativistas. Importante para entendermos como a cidade foi sendo erguida a partir de escolhas (e descasos).

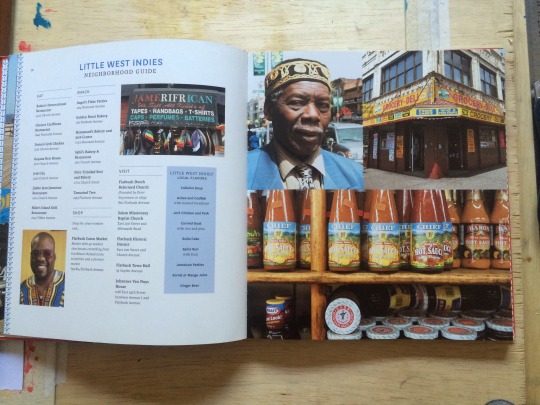

"New York: the big city and its little neighbourhoods" (The NYC & Company Foundation, 2009)

Um dos livros mais legais (foto abaixo) sobre cidades que já tive em mãos, fala sobre Nova York a partir de seus pequenos comércios de bairro, subvertendo a ideia de uma metrópole se fazer a partir somente de seus grande empreendimentos, monumentos, de sua área mais nobre: é nos cantinhos que a cidade imprime sua personalidade.

"Bexiga, um bairro afro-italiano" (Annablume, 2008)

Quem mora no bairro paulistano sabe disso, mas talvez para quem não viva nele, o fato de o Bexiga ser um bairro de origem afro, onde inicialmente havia um quilombo e onde muitos negros alforriados se estabeleceram pós-assinatura da Lei Áurea, talvez seja desconhecido. Esse ótimo livro conta um pouco dessa história que ficou apagada em meio a folclorização do bairro italiano, bem forte em décadas passadas.

[Originalmente publicado em 18/03/2019 aqui]

0 notes

Text

انمي NieR Automata Ver11a الحلقة 2 مترجمة

انمي NieR Automata Ver11a الحلقة 2 مترجمة

شاهد أنمي NieR Automata Ver11a الحلقة 2 ، مع ترجمة ، بدقة عالية على الإنترنت ، حلقات الرسوم المتحركة الخيالية NieR: Automata Ver1.1a 2023 الموسم الأول ، مع ترجمة ، تنزيل مبا��ر عبر الإنترنت. مسلسل أنمي مترجم حصريًا على Sima Taxi. التكيف المتحرك لـ NieR: Automata (2017) ، حيث تظهر قريبًا ما ستكشفه حرب طويلة الأمد على الأرض ما بعد المروع بين androids والآلات […]

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

2017-ben jártam arra, mert hogy Tés rajta van a kéktúrán. És egy sima ház udvarán keresztül lehet bejutni, fotóztam kívül és belül is. Itt lehet megnézni:

Windmill, Tés, 1933. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

165 notes

·

View notes

Photo

drawing sima yi and zhuge liang in place of “buenos dias mandy” is the best suggestion i’ve ever gotten

i promise that’s not a random wheel, i just put more detail into it than the rest of the horse carriage and didn’t feel like fixing it since i already had the pictures

#actually the original suggestion was just the imecil part but i thought it would be funnier to do the rest#i guess i'm posting this everywhere i can#i was losing it while drawing this#this is how i'm ending off 2017#dynasty warriors#sima yi#zhuge liang#arts

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

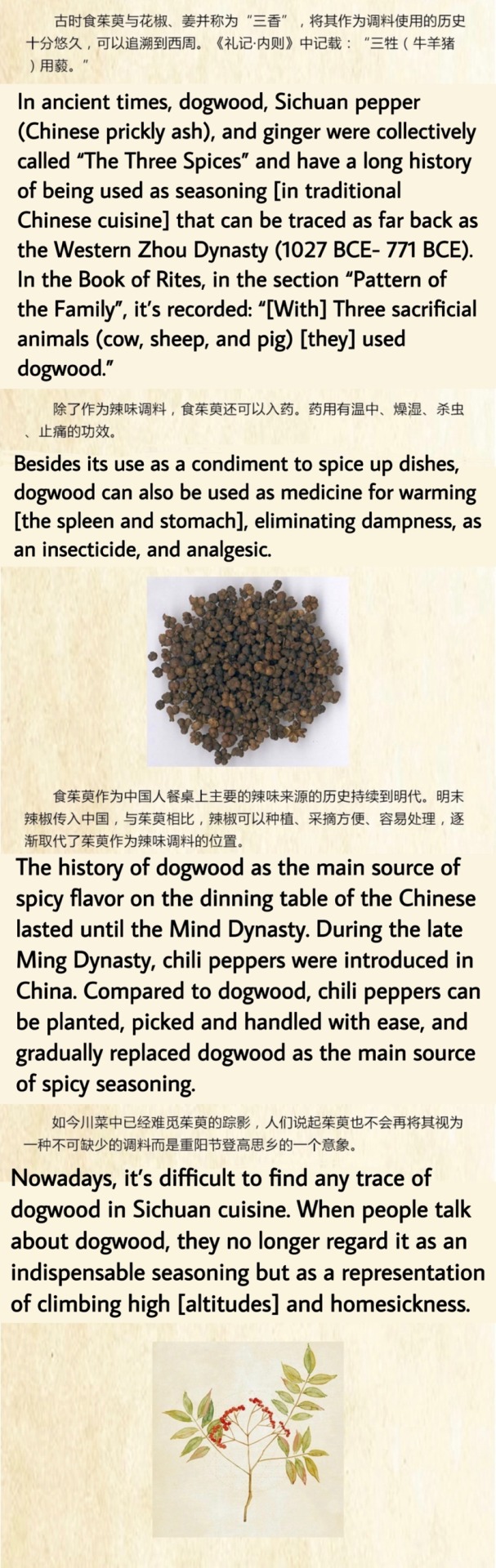

Advisors Alliance Mini Encyclopedia Translation Post 19: Dogwood

The Advisors Alliance 大军师司马懿之军师联盟 is a 2017 two-part Chinese TV series depicting the life of Sima Yi, a government official and military strategist who lived during the late Eastern Han Dynasty 东汉 (25 CE - 220 CE) and the Three Kingdoms Period 三国時代 (220 CE - 280 CE). [Wikipedia of the show’s first season]

The second part is titled Growling Tiger Roaring Dragon 虎啸龙吟 and keeps following Sima Yi’s life as he matures and becomes wiser [Link to the show’s second season’s MyDramaList page].

The Weibo account [Link] of the show made a series of posts in the style of small encyclopedias explaining different historical and cultural facts that where included in the series. The user @moononmyfloor compiled the 50 posts and asked me to translate them. This will be an ongoing series where I will do just that. Although I tried to stay as close as possible to the original text, I had to take some liberties in some posts to get the meaning across better. On the side, I have included extra information from personal research that explains certain things better.

The posts are not in order of the episodes but I will provide the episode and season number to avoid confusion. If there are any mistakes in translation, do let me know in the comments or privately message me and I will do my best to fix them.

If it is difficult to read the letters, tap or click on the image to expand it. Without more preamble, here you go.

There’s a typo. I meant “Ming Dynasty” not “Mind Dynasty”.

Extra information:

Double Ninth Festival, also known as Double Yang Festival and Chongyang Festival, is a Chinese holiday celebrated on the ninth day of the ninth month in the traditional Chinese calendar. It’s called the Double Yang Festival 重阳节 [Trad. 重陽節] because nine, in Chinese culture, was regarded to be a Yang number (6 was Yin). As such, the ninth day of the nine month was considered to have very strong Yang energy and, thus, was auspicious. People celebrated it by climbing high places such as mountains (from there the festival also came to be known as the Height Ascending Festival 登高节), drinking chrysanthemum wine, eating chrysanthemum cakes, appreciating chrysanthemum flowers, wearing dogwood branches on the hair, and visiting the graves of ancestors to leave food, drinks, and gifts. The tradition of climbing mountains likely came from the worship of mountains as ancient Chinese people climbed them to pray and receive blessings from the gods and/or ancestors. The Double Ninth Festival predates the Eastern Han Dynasty.

Like all other traditional Chinese holidays, poets wrote poems dedicated to celebrating the auspicious days. The fragment of the poem that is mentioned at the beginning of the post is one taught to children in China in elementary school. It’s by the Tang poet Wang Wei 王维 and it’s titled 《九月九日忆山东兄弟》 [Trad. 《九月九日憶山東兄弟》]. Below is the poem in both simplified and traditional Chinese. I will leave a translation made by American Poet Witter Bynner below.

Traditional:

獨在異鄉為異客,

每逢佳節倍思親。

遙知兄弟登高處,

遍插茱萸少一人。

Simplified:

独在异乡为异客,

每逢佳节倍思亲。

遥知兄弟登高处,

遍插茱萸少一人。

Translation (On the Mountain Holiday Thinking of my Brothers in Shandong)

All alone in a foreign land,

I am twice as homesick on this day.

When brothers carry dogwood up the mountain,

Each of them a branch -- and my branch missing.

The three sacrificial animals 三牲 changed depending on the dynasty. For instance, nowadays, people associate the three sacrificial animals with chicken, pork, and fish. However, in the time of the Western Zhou Dynasty, people referred to the three sacrificial animals as cow, sheep, and pig. Variations also include chicken, duck (or geese), and fish. Another variation involves five animals instead of three: chicken, duck, pork, fish, and squid. The purpose of animal sacrifice was to ask the gods and ancestors for protection and/or blessings.

Picture showcasing the five animal sacrifices 五牲 of chicken, pork, fish, duck, and squid [image source].

Catalogue (find the rest of the posts):

#chinese culture#chinese history#the advisors alliance#history#food history#food#dogwood#double yang festival#eastern han dynasty#western zhou dynasty#three kingdoms#wang wei#chinese poetry

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#rodrigo simas#boy#guy#man#hot#sexy#shirtless#waterfall#shower#nature#rio de janeiro#brazil#brasil#brazilian#2017

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Emma, Maile, and Angelina!

#calling her angelina is so weird bc i've called her sima since the first time i saw her name#emma malabuyo#maile o'keefe#angelina simakova#junior japan 2017

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I hope you are doing okay with all the discourse going around. Im white and raised in a very white society so i will never have a say in it, but i was wondering, is there any way i can educate myself more in asian/chinese culture? Im aware i consume content thru western lens and because of that i dont really get all the nuances of the shows, but i would like to have at least some backround. Im guessing just watching the shows doesnt give enough of that, can you maybe reccommend some blogs or books to check out? (If you dont thats totally fine and im sorry if i said anything offensive)

Hey friend! Not offensive at all, no worries. Honestly, I’m not too sure. I think just keeping an open mind about things is a really good start. I’m not really sure which blogs to recommend but if I could recommend some dramas? Since it’s probably easier to watch a show then read a book?

《The Story of Minglan》 is a good one to sort of parse out the intricacy of historical Chinese society in the Song Dynasty, keeping in mind that different dynasties have different practices, so even amongst different time periods there were differences. 《The Story of Yanxi Palace》 is another good one for Qing Dynasty (circa 1740s) if you wanna get into imperial harem stuff. (Or you can watch 《甄嬛传》 or 《如懿传》 for harem stuff. I just think The Story of Yanxi Palace is the most palatable, most aesthetic, and most fun out of the three. The other two are kinda tragic?) There are other dramas but I feel they’re not as... accessible?

Chinese historical dramas come in 3 flavours: serious dramas, idol dramas, and those that ride the fence. What I mean by idol drama is...everyone in it is young and hot and the writing is eh and the acting is eh. More often then not there’s a lot of modern elements to it. The Untamed is so popular because it’s idol drama done really well. (xianxia and wuxia genre used to be more quality when I was a kid, but now they’re kind of ehhhh.) I would say Minglan and Yanxi are both successful because they ride the fence.

On the other hand, serious historical drama has A LOT of politics and can be quite dry especially if you’re watching it through half-assed subtitles. The actors typically are more seasoned, older. People jokingly say that idol drama is what mom watches and serious drama is what dad watches, and honestly given my parents’ tv habits...it’s pretty accurate 😂.

Some really well known ones from the past 20 years are:

The 《铁齿铜牙纪晓岚》 series 1-4. I would only recommend part 1-2, 3-4 are not as great. This one has quite a bit of humour but it might fly over your head a bit because of the language barrier. The story surrounds a well known government official and scholar named Ji Xiaolan 纪晓岚, his frenemy and colleague the (EXTREMELY corrupt) prime minister He Shen, and the Emperor Qianlong. For better or worse these three are depicted as both liege and subjects as well as friends. Trying to see Ji Xiaolan and He Shen one up each other while Qianlong tries to balance his court and rule the country is quite interesting. I won’t pretend this is an easy series to follow, but it’s actually quite fun.

《汉武大帝》 - is about Hanwu Emperor of the Han Dynasty circa 150 BC? He’s one of the most famous emperors of distant history. It’s basically about the course of his life and the many people that featured in it.

《大明王朝 》- my memories of this one is very vague, but it is about the Ming Dynasty (the dynasty before the Qing Dynasty c. 1500,1600.)

《The Advisors Alliance 军事联盟》- 2017 two-part television series based on the life of Sima Yi, a government official and military general who lived in the late Eastern Han dynasty and Three Kingdoms period of China. circa 150 AD.

As a side note, a lot of serious dramas for a while now have been focused on the Qing Dynasty, just because it’s the last imperial dynasty before Imperial China fell into decline, WWI and WWII ravaged the country and communism happened. Even a lot of idol drama are about the Qing Dynasty (I feel like I should do a post about this, just to string things together haha).

So for the Qing Dynasty, because they are Manchurian, their last name is Aisin Gioro or in Chinese Aixin Jueluo 爱新觉罗. Their earlier emperors are much more well known than their later ones and have been the focus of MANY dramas. (You’ll notice their names in the beginning spell very different than the Chinese names you’re used to, but once they take over China, the emperors’ names start to become more and more mainland Chinese and less and less Manchurian.)

Nu’er Hachi 努尔哈赤/ Nurhaci - The granddaddy of Qing Dynasty, but was never officially Emperor of China during his life time.

Huang Taiji 皇太极 - Nurhaci’s oldest son. He led the campaign against the Ming Dynasty but died before the campaign was over

Fulin 福林, Emperor Shunzhi 顺治 - Huang Taiji’s 9th son. He is the real first Emperor of the Qing Dynasty. His uncle Duo’Ergun 多尔衮/ Dorgon was his regent as well as his commander-in-chief. Dorgon was the one who won the war against the Ming Dynasty and instated his nephew as the Emperor. Fulin was 6 years old when this happened, and now you may wonder why the fuck is that? It’s because Fulin’s mother, Huang Taijii’s widowed concubine Consort Zhuang (name: pu’erji-jite bumubutai (pinyin) 博爾濟吉特 布木布泰/ Bumbutai Borjigit, Da-Yu’er 大玉儿) remarried her brother-in-law Dorgon. Whether Bumbutai and Dorgon were actually in love is....contestable. Certainly one of my favourite serious dramas that depict this part of history is《大青风云》.

Xuanye 玄燁, Emperor Kangxi 康熙 - Fulin’s third son. Very famous. Very long reign. Serious drama associated 《康熙微服私访记》, 《康熙王朝》

Yinzhen 胤禛, Emperor Yongzheng 雍正 - Xuanye's 4th son. His reign was highly contested because some ppl believed he forged the succession document. It’s probably not true. He was an efficient emperor but very austere, very severe. Not well liked. The best serious drama about him is probably 《雍正王朝》and the aforementioned《甄嬛传》. The former is 100% politics and a fictional re-telling of historical events whereas the latter is 100% harem drama and 100% made up. 《步步惊心》is an idol drama about a girl who transmigrated back to this time and fell in love with Yinzhen. Lol.

Hongli 弘历, Emperor Qianlong 乾隆 - Yinzhen’s 4th son. I think he’s the longest living/reigning emperor of Chinese history. SOOOOO many dramas were made about him or set in his reign. Of the serious drama category: 《铁齿铜牙纪晓岚》 that I mentioned earlier is really good. There are others but I won’t name them here. 《如懿传》 is a serious drama about his harem, but really terrible? I really didn’t like it (just my personal view). Incidentally it was released around the same time as《The Story of Yanxi Palace 延禧攻略》which is also about his harem and MUCH better in my opinion, because the actor for Hongli in Yanxi is much better skills-wise. 《还珠格格》was the OG idol drama about Hongli’s children. I gave a brief synopsis about it here. It was made in the 90s but damn...so nostalgic.

There’s many more emperors after him, but they’re not as important.

Okay yeah, so I’m not sure if any of this is really helpful, but definitely watching serious drama gives you much better context and understanding of Chinese culture than idol drama. I mean when the drama has flying and magic...the historical relevance sort of falls to the side. 🤣

ADDENDUM: I made a typo earlier. Fulin is Huang Taiji’s 9th son, not Nurhaci’s son. Also Abahai is Huang Taijii’s mother’s name (wikipedia lied to me on this one XD).

127 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top 5:

UMK songs

Drinks (alcoholic or not)

Fave school subjects

🥰🎈🎉

top 5 UMK songs

Dark Side 🖤

Something Better (by Softengine, 2014)

Cicciolina (by Erika Vikman, 2020)

Blackbird (by Norma John, 2017)

Let Me Out (by Barbe-Q-Barbies, 2016)

(a special mention to Bananas by F3M, 2020)

top 5 drinks

Coke

sima!

this watermelon & yuzu flavoured soda water

rose hip & hibiscus infusion

...just water :D

top 5 school subjects

Finnish

English

music

arts & crafts

I guess geography was alright

thank youuuu hauskaa vappuaaaaaa!! 💚🥳

#oops i didn't mention jezebel 💁♀️#i hope they do well though. i mean i won't be holding my breath but i hope they at least advance to the final#so that i can scream at my tv over sweden not giving us any points again

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

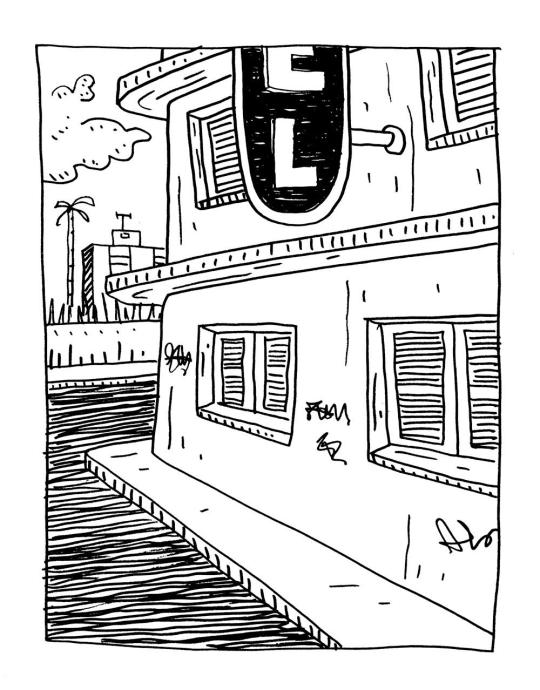

O caminhar como potência criativa: duas mesas da Flip para rever

Arte: MZK (mkz68.tumblr.com)

[Originalmente publicado em 22/10/2018 aqui]

É importante navegar junto à costa e observar as paisagens, mas também entender onde descer a âncora, encontrar quem mora naquelas terras, descobrir estratégias para ir ao encontro dele, aprender a cumprimentar. Sem tudo isso, construir objetos e edifícios parece uma ação com fim em si mesma, vazia de significado, incapaz de produzir mito, história, cultura. A arte de ir ao encontro de alguém produz conhecimento recíproco entre as pessoas que se movem em nosso novo mundo e nos ajuda a imaginar, com elas, uma outra maneira de habitá-lo. – "Caminhar e Parar" (Francesco Careri)

Faz alguns dias que me encontrei com o saboroso "Caminhar e Parar" (GG, 2017), do arquiteto italiano Francesco Careri. Conheci o trabalho de Careri por meio de uma amiga. Pesquisador, ele fundou em 1995, ao lado de outros artistas e arquitetos, o laboratório Stalker/Osservatorio Nomade, uma "reunião de interessados que realizam, na cidade, ações de arte pública, informal e multicultural", diz a orelha do livro.

Durante vinda ao Brasil em 2016, dentre outras atividades, o italiano participou de uma conversa na Festa Literária de Paraty, a Flip. Na mesa "Cidades Refletidas", ele falou ao lado da arquiteta e urbanista Lúcia Leitão, fundadora do Núcleo de Estudos de Subjetividade na Arquitetura (Nusarq – UFPE), sobre a experiência humana nas cidades.

"Acredito que ensinar a caminhar é um grande ato de democracia. Tornar-se si mesmo na rua, se controlar com os próprios olhos, o próprio corpo e a própria presença é a única forma de segurança das nossas ruas", disse Careri.

"Andar na cidade é obrigatoriamente ter o outro em face. E isso fala de que nível de sociedade a gente tem, como ela se organizou, que valores compõem essa sociedade, quão democrática ela é", falou Lúcia Leitão.

youtube

Lendo o livro e assistindo ao vídeo, me lembrei de outra mesa da Flip muito potente sobre ruas e cidades. Convidados em 2017 a falar sobre o Rio na obra de Lima Barreto, o escritor e historiador Luiz Antonio Simas e a pesquisadora e crítica literária Beatriz Rezende lembraram o quanto o "subúrbio é apagado da memória do Rio de Janeiro", disse Simas. "Mais do que nunca, nós precisamos de alguns Lima Barreto", colocou Beatriz Rezende.

"Esse convite do Lima Barreto, esse convite que ele nos faz a conhecer o subúrbio deixando de lado o exotismo turístico, resume um dos grandes gestos revolucionários deste escritor que é de sugerir que o subúrbio faz parte da cidade, e aqueles que a sociedade empurra pras margens também são cidadãos", falou o mediador Guilherme Freitas.

youtube

Em tempos de ódio e posturas antidemocráticas normalizadas, são dois vídeos que trazem não só um pensamento ousado sobre as cidades brasileiras e o modo como nos dispomos a vivê-las, mas também uma dose de otimismo ao olhar para a potência daquilo que é humano.

[Originalmente publicado em 22/10/2018 aqui]

0 notes