#Raphael Rubinstein

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Heather Rubinstein, Painting as a Non-Professional Experiment (for and from James Murphy). 2014, acrylic on canvas. 72 × 84". Painting by Heather Rubinstein, crossing out poem and writing in painting; Poem by Raphael Rubinstein, transcribed from an interview with James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem, where Rubinstein's poem replaced Murphy's original use of the word band. Courtesy of the artist.

0 notes

Text

Brian Dupont defends the current trends of provisional and casual painting.

Dupont writes: “Artists today are confronting an increasingly ramshackle future where aesthetic, political, economic, and ecological promises have been revealed as failures. If they are seeing a future where issues of scarcity become more urgent, materials must be recycled or scavenged from surplus, and long-held political standards become increasingly irrelevant, it would seem natural to see trends in painting (re) emerge that question formal equivalents of these standards. The long-term success of painting can be attributed to its ability to colonize and assimilate outside ideas and approaches, stretching form and content to the breaking point so that the project of the medium is ultimately made stronger. If a provisional vocabulary can provide a timely reinvigoration of the expression of individual concerns, that should be all the ambition anyone needs in a painting.” https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/provisional-painting-raphael-rubinstein-62792/: "For the past year or so I’ve become increasingly aware of a kind of provisionality within the practice of painting. I first noticed it pervading the canvases of Raoul De Keyser, Albert Oehlen, Christopher Wool, Mary Heilmann and Michael Krebber, artists who have long made works that look casual, dashed-off, tentative, unfinished or self-cancelling. In different ways, they all deliberately turn away from “strong” painting for something that seems to constantly risk inconsequence or collapse."

0 notes

Photo

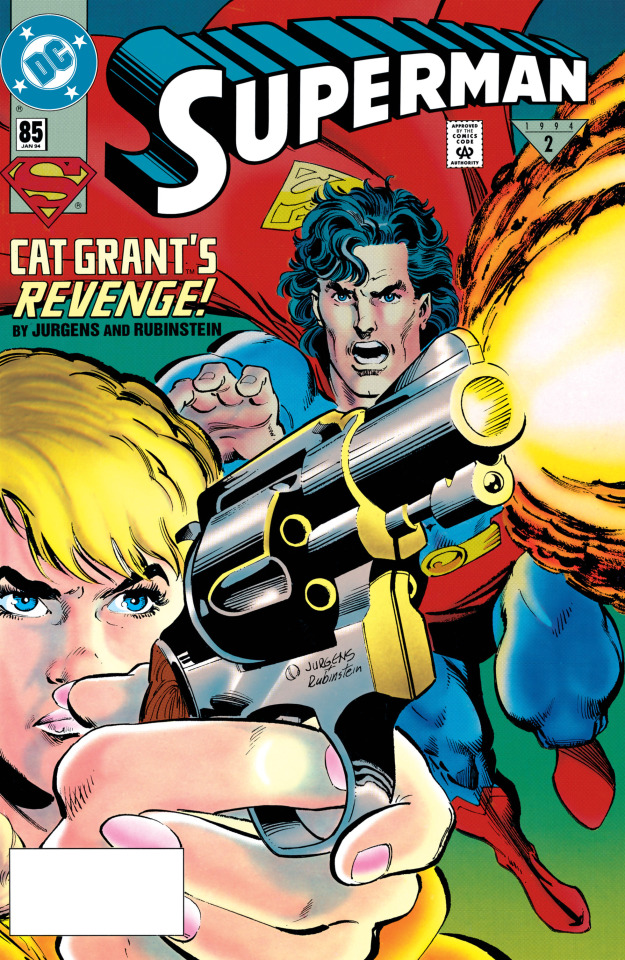

Superman #85 (January 1994)

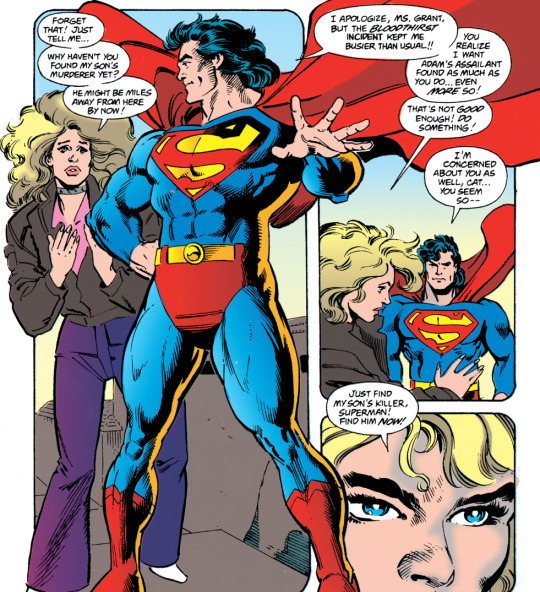

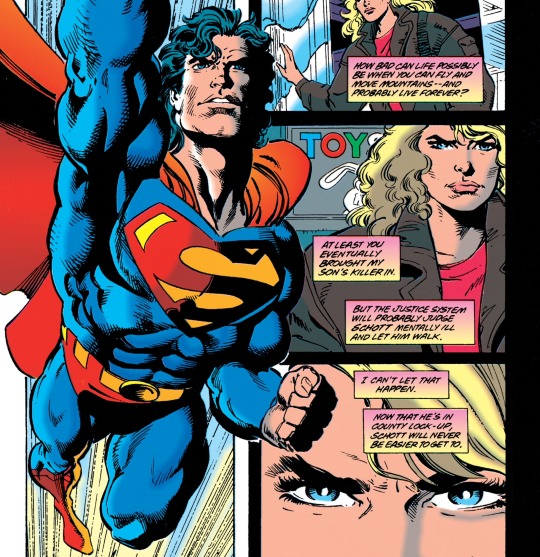

Cat Grant in... "DARK RETRIBUTION"! Which is like normal retribution, but somehow darker. On the receiving end of Cat's darktribution is Winslow Schott, the Toyman, who suddenly changed his MO from "pestering Superman with wacky robots" to "murdering children" back on Superman #84, with one of his victims being Cat's young son Adam. Now Cat has a gun and intends to sneak it into prison to use it on Toyman. She's also pretty pissed at Superman for taking so long to find Toyman after Adam’s death (to be fair, Superman did lose several days being frozen in time by an S&M demon, as seen in Man of Steel #29).

So how did Superman find Toyman anyway? Basically, by spying on like 25% of Metropolis. After finding out from Inspector Turpin that the kids were killed near the docks, Superman goes there and focuses all of his super-senses to get "a quick glimpse of every person" until he sees a bald, robed man sitting on a giant crib, and goes "hmmm, yeah, that looks like someone who murders children." At first, Superman doesn't understand why Toyman would do such a horrible thing, but then Schott starts talking to his mommy in his head and the answer becomes clear: he watched Psycho too many times (or Dan Jurgens did, anyway).

Immediately after wondering why no one buys his toys, Toyman makes some machine guns spring out of his giant crib. I don't know, man, maybe it's because they're all full of explosives and stuff? Anyway, Toyman throws a bunch of exploding toys at Superman, including a robot duplicate of himself, but of course they do nothing. Superman takes him to jail so he can get the help he needs -- which, according to Cat, is a bullet to the face. Or so it seems, until she gets in front of him, pulls the trigger, and...

PSYCHE! It was one of those classic joke guns I’ve only ever seen in comics! Cat says she DID plan to bring a real gun, but then she saw one of these at a toy store and just couldn't resist. Superman, who was watching the whole thing, tells Cat she could get in trouble for this stunt, but he won't tell anyone because she's already been through enough. Then he asks her if she needs help getting home and she says no, because she wants to be more self-sufficient.

I think that's supposed to be an inspiring ending, but I don't know... Adam's eerie face floating in the background there makes me think she's gonna shave her head and climb into a giant crib any day, too. THE END!

Character-Watch:

Cat did become more self-sufficient after this, though. Up to now, all of her storylines seemed to revolve around other people: her ex-husband, Morgan Edge, José Delgado, Vinnie Edge, and finally Toyman. After this, I feel like there was a clear effort to turn her into a character that works by herself. I actually like what they did with Cat in the coming years, though I still don’t think they had to kill her poor kid to do that -- they could have sent him off to boarding school, or maybe to live with his dad. Or with José Delgado, over at Power of Shazam! I bet Jerry Ordway would have taken good care of him.

Plotline-Watch:

Wait, so can Superman just find anyone in Metropolis any time he wants? Not really: this is part of the ongoing storyline about his powers getting boosted after he came back from the dead, which sounds pretty useful now but is about to get very inconvenient.

Don Sparrow points out: "It is interesting that as Superman tries to capture Schott, he at one point instead captures a robot decoy, particularly knowing what Geoff Johns will retroactively do to this storyline in years to come, in Action Comics #865, as we mentioned in our review of Superman #84." Johns also explained that the robot thought he was hearing his mother's voice due to the real Toyman trying to contact him via radio, which I prefer to the "psycho talks to his dead mom" cliche.

Superman says "I never thought he'd get to the point where he'd KILL anyone -- especially children!" Agreed about the children part but, uh, did Superman already forget that Toyman murdered a whole bunch people on his very first appearance, in Superman #13? Or does Superman not count greedy toy company owners as people? Understandable, I guess.

There's a sequence about Cat starting a fire in a paper basket at the prison to sneak past the metal detector, but why do that if she had a toy gun all long? Other than to prevent smartass readers like us from saying "How did she get the gun into the prison?!" before the plot twist, that is.

Patreon-Watch:

Shout out to our patient Patreon patrons, Aaron, Murray Qualie, Chris “Ace” Hendrix, britneyspearsatemyshorts, Patrick D. Ryall, Bheki Latha, Mark Syp, Ryan Bush, Raphael Fischer, Dave Shevlin, and Kit! The latest Patreon-only article was about another episode of the 1988 Superman cartoon written by Marv Wolfman, this one co-starring Wonder Woman (to Lois' frustration).

Another Patreon perk is getting to read Don Sparrow's section early, because he usually finishes his side of these posts long before I do (he ALREADY finished the next one, for instance). But now this one can be posted in public! Take it away, Don:

Art-Watch (by @donsparrow):

We begin with the cover, and it’s a good one— an ultra tight close up for Cat Grant firing a .38 calibre gun, with the titular Superman soaring in, perhaps too late. An interesting thing to notice in this issue (and especially on the cover) is that the paper stock that DC used for their comics changed, so slightly more realistic shading was possible. While it’s nowhere near the sophistication or gloss of the Image Comics stock of the time, there is an attempt at more realistic, airbrushy type shading in the colour. It works well in places, like the muzzle flash, on on Cat Grant’s cheeks and knuckles, but less so in her hair, where the shadow looks a browny green on my copy.

The interior pages open with a pretty good bit of near-silent storytelling. We are deftly shown, and not told the story—there are condolence cards and headlines, and the looming presence of a liquor bottle, until we are shown on the next page splash the real heart of the story, a revolver held aloft by Catherine Grant, bereaved mother, with her targeting in her mind the grim visage of the Toyman.

While their first few issues together meshed pretty well, it’s around this issue that the pencil/inks team of Jurgens and Rubinstein starts to look a little rushed in places. A few inkers who worked with Jurgens that I’ve spoken to have hinted that his pencils can vary in their level of detail, from very finished to pretty loose, and in the latter case, it’s up to the inker to embellish where there’s a lack of detail. Some inkers, like Brett Breeding, really lay down a heavier hand, where there’s quite a bit of actual drawing work in addition to adding value and weight to the lines. I suspect some of the looseness in the figures, as well as empty backgrounds reveals that these pencils were less detailed than we often see from Jurgens.

There’s some weird body language in the tense exchange between Superman and Cat as she angrily confronts him about his lack of progress in capturing her son’s killer—Superman looks a little too dynamic and pleased with himself for someone ostensibly apologizing. Superman taking flight to hunt down Toyman is classic Jurgens, though.

Another example of art weirdness comes on page 7, where Superman gets filled in on the progress of the Adam Morgan investigation. Apparently Suicide Slum has some San Francisco-like hills, as that is one very steep sidewalk separating Superman and Turpin from some central-casting looking punks.

The sequence of Superman concentrating his sight and hearing on the waterfront area is well-drawn, and it’s always nice to see novel uses of his powers. Tyler Hoechlin’s Superman does a similar trick quite often on the excellent first season of Superman & Lois. The full-bleed splash of Superman breaking through the wall to capture Toyman is definitely panel-of-the-week material, as we really feel Superman’s rage and desperation to catch this child-killer.

Pretty much all the pages with Cat Grant confronting Winslow Schott are well-done and tensely paced. While sometimes I think the pupil-less flare of the eye-glasses is a cop-out, it does lend an opaqueness and mystery to what Toyman is thinking. Speaking of cop-outs, the gag gun twist ending really didn’t work for me. I was glad that Cat didn’t lower herself to Schott’s level and become a killer, even for revenge, but the prank gun just felt too silly of a tonal shift for a storyline with this much gravitas. The breakneck denouement that Cat is now depending only on herself didn’t get quite enough breathing room either.

While I appreciated that the ending of this issue avoided an overly simplistic, Death Wish style of justice, this issue extends this troubling but brief era of Superman comics. The casual chalk outlines of yet two more dead children continues the high body count of the previous handful of issues, and the tone remains jarring to me. The issue is also self-aware enough to point out, again, that Schott is generally an ally of children, and not someone who historically wishes them harm, but that doesn’t stop the story from going there, in the most violent of terms. In addition to being a radical change to the Toyman character, it’s handled in a fashion more glib than we’re used to seeing in these pages. The mental health cliché of a matriarchal obsession, a la Norman Bates doesn’t elevate it either. So, another rare misstep from Jurgens the writer, in my opinion. STRAY OBSERVATIONS:

I had thought for sure that Romanove Vodka was a sly reference to a certain Russian Spy turned Marvel superhero, but it turns out there actually is a Russian Vodka called that, minus the “E”, produced not in Russia, as one might think from the Czarist name, but rather, India.

While it made for an awkward exchange, I was glad that Cat pointed out how her tragedy more or less sat on the shelf while Superman dealt with the "Spilled Blood" storyline. A lesser book might not have acknowledged any time had passed. Though I did find it odd for Superman to opine that he wanted to find her son’s murderer even more than she wanted him to. Huh? How so?

I love the detail that Toyman hears the noise of Superman soaring to capture him, likening it to a train coming.

I quibble, but there’s so much I don’t understand about the “new” Toyman. If he’s truly regressing mentally, to an infant-like state, why does he wear this phantom of the opera style long cloak while he sits in his baby crib? Why not go all the way, and wear footie pajamas, like the lost souls on TLC specials about “adult babies”?

I get that Cat Grant is in steely determination mode, but it seemed a little out of place that she had almost no reaction to the taunting she faced from her child’s killer. She doesn’t shed a single tear in the entire issue, and no matter how focused she is on vengeance, that doesn’t seem realistic to me. [Max: That's because this is not just retribution, Don. It's dark retribution. We’ve been over this!]

#superman#dan jurgens#joe rubinstein#cat grant#adam morgan#toyman#dan turpin#joke guns that only exist in comics#cat grant the dark retributor#coming soon to image comics

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Muses I need to add on my page

This is just a list of muses I’ve plotted with and need to add to my muses page. If we’ve plotted with someone else and they’re neither here or on my full muses page, please let me know and I’ll add them!

Bianca Rutherford(Caitlin Stasey fc)

Daphne Greengrass(Tati Gabrielle fc)

Dominic Steele(Casey Deidrick fc)

Eisheth Pentland(Olivia Taylor-Dudley fc)

Jaiden Wheeler(Charlie Rowe fc)

Kerem Aslan(Berker Guven fc)

Priscilla Hawthorne(Natalia Dyer fc)

Prudence ???(India Eisley fc)

Raphaelle Delong(Zoey Deutch fc)

Sturgis Podmore(Ronen Rubinstein fc)

Timothy Watts(Landon Liboiron fc)

Trula Twyst(Katherine McNamara fc)

Valda Blake(Chloe Bridges fc)

Zelda Spellman(Emma Rigby fc)

Still unnamed vampire(Avan Jogia fc)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Art texts in non-art contexts: the potential audience is expanded beyond the typical museum-going public.

Just as importantly, the unexpectedness of encountering the work and its unusual narrative format will connect the texts more deeply with viewers than is often the case with conventional public art. Working collaboratively and across mediums, Bause and Rubinstein will consciously utilize all aspects their materials, from the hybrid nature of the texts (which employ literary devices rather than standard art criticism) to the ambiguous status of the objects.

0 notes

Photo

"‘Pandemic fatigue’ presents a challenge in areas scrambling to avert a second wave." by BY MARC SANTORA, ISABELLA KWAI, SARAH MERVOSH, JULIE BOSMAN, DANA RUBINSTEIN, JULIANA KIM, KAREN ZRAICK AND RAPHAEL MINDER via NYT World https://ift.tt/34H2jiJ

0 notes

Photo

"‘Pandemic fatigue’ presents a challenge in areas scrambling to avert a second wave." by BY MARC SANTORA, ISABELLA KWAI, SARAH MERVOSH, JULIE BOSMAN, DANA RUBINSTEIN, JULIANA KIM, KAREN ZRAICK AND RAPHAEL MINDER via NYT World https://ift.tt/34H2jiJ

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

List of individuals and groups who have participated in an event at 356 Mission

LeanThe New Dreamz (Rose Luardo and Andrew Jeffrey Wright)

Andre Hyland

Whitmer Thomas

Jessica Ciocci

Michael Webster

Asha Schechter

Gabu Heindl & Drehli Robnik (screening)

Rachel Kushner (with parts read by Barry Johnston, Gale Harold, Karen Adelman, Paul Gellman, Stuart Krimko, Stanya Kahn, Alex Israel, Milena Muzquiz)

Mina Stone

Ken Ehrlich & Emily Joyce

Flora Wiegmann with Alexa Wier

James Lee Byars (screening)

Trisha Brown (screening)

Ei Arakawa (screening)

Jennifer Phiffer

Euan MacDonald and Henri Lucas

Fundación Alumnos47

ForYourArt

Derek Boshier

Alex Kitnick

Cherry Pop

De Porres

Aaron Dilloway

Jason Lescalleet

John Wiese

Final Party (Barry Johnston)

Crazy Band

Aram Moshayedi

Bruce Hainley

Gary Dauphin

Kathryn Garcia

Leland de la Durantaye

Sohrab Mohebbi

Tala Madani

Tiffany Malakooti

Negar Azimi

Barbara T. Smith

LeRoy Stevens

Joe Sola and Michael Webster

Math Bass and Lauren Davis Fisher

Angel Diez Alvarez (screening)

Hedi El Kholti

K8 Hardy

Anna Sew Hoy

L.A. Fog

Trinie Dalton

Rita Gonzalez

Alex Klein

Mark Owens

Tanya Rubbak

AL Steiner

C.R.A.S.H.

Lao

Mexican Jihad

Zak-Matic

Laura Poitras (screening)

Parker Higgins

Domenick Ammirati

John Seal

John Tain

Bruce Hainley

Lisa Lapinski

Kate Stewart

Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer

Ian Svenonius

Entrance Band

Allison Wolfe

Geneva Jacuzzi

Chain & the Gang

Shivas

Hunx

Jimi Hey

69

Tim Lokiec

Scott & Tyson Reeder

Total Freedom

Prince William

Kingdom

SFV Acid

Jesse Fleming

William Leavitt

Lucas Blalock

Oliver Payne

Meredith Monk

Jessica Espeleta

Rollo Jackson (screening)

Jack Smith (screening)

Noura Wedell

Sylvère Lotringer

Jesse Benson

Zoe Crosher

Alex Cecchetti

Patricia Fernandez

Jeff Khonsary

Ben Lord

Shana Lutker

Joseph Mosconi

Suzy Newbury

Scott Oshima

Kim Schoen

Clarissa Tossin

Mark Verabioff

Brica Wilcox

Michael Clark

Ben Brunnemer

Ted Byrnes / Corey Fogel

Kirsty Bell

Johnston Marklee

Emily Sundblad & Matt Sweeney

Kevin Salatino

Wooster Group (screening)

Shannon Ebner

East of Borneo

Sue Tompkins

Alexis Taylor

Leslie Buchbinder (screening)

Odwalla88

Dean Spunt

Bebe Whypz

Saman Moghadam (screening)

J Cush

Hive Dwellers

Bouquet

Dream Boys

Jen Smith

Thee Oh Sees

Jack Name

Alex Waterman and Will Holder

Jonathan Horowitz

Ali Subotnick

Brian Calvin

Dean Wareham

Gracie DeVito

Indah Datau

Jake DeVito

Sara Gomez

Luke Harris

Sarah Johnson

Julia Leonard

Jillian Risigari-Gai

Joseph Tran

George Kuchar (screening)

Andrew Lampert

Reach LA

Oscar Tuazon

Black Dice

Danny Perez

Avey Tare

Shinzen Young

Jesse Fleming and Lewis Pesacov

Mecca Vazie Andrews

Mira Billotte

Julian Ceccaldi

Oldest (Brooks Headley & Mick Barr)

DJ Andy Coronado

François Ceysson

Amanda Ross-Ho

Raphael Rubinstein

Wallace Whitney

Bradford Nordeen

Chris Kraus

Samuel Dunscombe & Curt Miller

Jay Chung

Lev Kalman & Whitney Horn (screening)

Maricón Collective

The Shhh

Alice Bag

Martin Sorrondeguy

Sex Stains

Kevin Hegge (screening)

Rhonda Lieberman

Lisa Anne Auerbach

David Benjamin Sherry

Eric Wesley

Tamara Shopsin, Jason Fulford, and Brooks Headley

Deborah Hay

Becky Edmunds (screening)

Kath Bloom

Erin Durant

Ben Vida

Charles Atlas

Laurie Weeks

Kerry Tribe

Renée Green

Fred Moten

The Office of Culture and Design / Hardworking Goodlooking

YUK, MNDSGN, and AHNUU

PATAO

Michael Biel

Mark Von Schlegell

Graham Lambkin

Lex Brown

Jibade-Khalil Huffman

Dan Levenson

Sarah Mattes

Carmen Winant

Gloria Sutton

John Musilli (screening)

Pieter Schoolwerth and Alexandra Lerman (screening)

Nate Young

Safe Crackers

Frances Stark

Liliana Porter (screening)

Adam Linder

Corazon del Sol

Gary Cannone

Ben Caldwell

Jacqueline Frazier

Jan-Christopher Horak

Haile Gerima (screening)

Barbara McCullough (screening)

Jon Pestoni

Andrew Cannon

David Fenster

Dick Pics

Seth Bogart

Lonnie Holley

Rudy Garcia

Dynasty Handbag

Christine Stormberg

Anthony Valdez

Kate Mosher Hall

JJ Stratford

Diana Adzhaketov

DJs Cole MGN and Nite Jewel

Casey Jane Ellison

Gary Indiana + Walter Steding

Kate Durbin

Michael Silverblatt

Hamza Walker

Wynne Greenwood

Robert Morris

Maggie Lee (screening)

Brendan Fowler

Susan Cianciolo

Aaron Rose

John Boskovich (screening)

Michel Auder (screening)

Lauren Campedelli, Leo Marks, and Jan Munroe

Klang Association feat. Anna Homler (Breadwoman), Jorge Martin, Jeff Schwartz

sodapop

Hoseh

Miles Cooper Seaton & Heather McIntosh

Drip City

Geologist

Deaken

Brian Degraw

$3.33

Angela Seo

George Jensen

Carole Kim & Jesse Gilbert & Friends

Aledandra Pelly

dublab

Mariko Munro

Emily Jane Rosen

Lana Rosen

Max Syron

Mark Morrisroe (screening)

Ramsey McPhillips

Stuart Comer

Jordan Wolfson

Kiva Motnyk

Samara Golden

Sam Ashley

John Krausbauer

Kate Valk

Elizabeth LeCompte

Lewis Klahr

Barbara Kasten

Martine Syms

Margo Victor

Studioo Manueel Raaeder

Mary Farley

Wayne Koestenbaum

Jibz Cameron

Sean Daly

Kendra Sullivan

Trinh T. Minh-ha

Johanna Breiding + Jennifer Moon

Tisa Bryant

Cog•nate Collective (Misael G Diaz + Amy Y Sanchez-Arteaga)

Bridget Cooks

Michelle Dizon

Anne Ellegood

Shoghig Halajian

Katherine Hubbard

Simon Leung

Amanda McGough + Tyler Matthew Oyer

Dylan Mira

Litia Perta

Eden’s Herbals

Matt Connors

Flat Worms

Susan

Lucky Dragons

Dos Mega

David Korty

Monica Majoli

Forrest Nash

Sophie von Olfers

Rudolf Eb.er

dave phillips

Joke Lanz

The Dog Star Orchestra

The Edge of Forever (Elizabeth Cline + Lewis Pesacov)

Lutz Bacher (screening)

Agnes Martin (screening)

Marisa Takal

Moyra Davey (screening)

Suzanna Zak

Wu Tsang, boychild and Patrick Belaga

Snake Jé

VIP

Fictitious Business DBA The Geminis

DJ M.Suarez

Asmara

Weirdo Dave

Mission Chinese

Veronica Gonzalez Peña

Thomas Bayrle

Bernhard Schreiner

Bob Nickas

The Cactus Store / Christian Herman Cummings

Atelier E.B

Iman Issa

Diana Nawi

Sqirl

Downtown Women’s Center

Earthjustice

Juvenile Justice Clinic at Loyola Law School

Loyola Immigrant Justice Clinic

N.eed O.rganize W.ork

Planned Parenthood

SoCal 350 Climate Action

St. Athanasius

WriteGirl

Sean/Milan

John Santos

Thomas Davis

Twisted Mindz

Adrienne Adams

Evan Kent

Jasmine McCloud

Gia Banks

Ace Farren Ford

Dennis Mehaffey

Fredrik Nilsen

Paul McCarthy

Joe Potts

Rick Potts

Tom Recchion

Vetza

Oliver Hall

Rigo 23

Gil Kenan & Vice Cooler (screening)

Cassie Griffin

Clara Cakes

Clay Tatum + Whitmer Thomas (Power Violence)

DJ AshTreJinkins

DJs Protectme

Crush

Sara Knox Hunter

Dodie Bellamy

Miranda July

Alexander Keefe

Thomas Keenan

Kevin Killian

Silke Otto-Knapp

Calypso Jete, Essence Jete Monroe, Virginia X, Leandra Rose, Naomi Befierce, Tori Perfection, Foxie Adjuis

Brontez Purnell

Kate Wolf

Adam Soch (screening)

Dar A Luz

ADSL Camels

Cold Beat

Tropic Green

No Sesso

Michelle Carrillo

Ruth Root

Timothy Ochoa

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography

Acton, Mary. Learning To Look At Modern Art. Psychology Press, 2004.

Buchloh, Benjamin H. D., Foster, Hal, Joselit, David, Krauss, Rosalind and Yve-Alain, Bois. Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism. London: Thames & Hudson, 2011.

De Duve, Thierry. Kant After Duchamp. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1998.

Fricke, Roswitha, Sieg, Seth and Fricke, Marion. The Context of Art, The Art of Context : 1969 - 1992 Project. Navado Press, 2004

.Gablik, Suzi. Has Modernism Failed. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2004.

Holmes, A.M. V.F. Portrait: John Currin in Vanity Fair. 2011.

Rubinstein, Raphael. “Provisional Painting.” Art in America. United States: Art Media Holdings, 2009.

Schjeldahl, Peter. Columns and Catalogues. Figures, 1994.

Soloman, Deborah. How to Succeed in Art. New York: New York Times, 1999.

Tomkins, Calvin. Lifting the Veil: Old Masters, pornography, and the work of John Currin. New York: The New Yorker, 2008.

Grogan, Sarah. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women, and Children. London: Routledge, 2008.

Sweetman, Paul Jon. Marking the Body: Identity and Identification in Contemporary Body Modification. University of Southampton, 1999.

Eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz. (n.d.). Stuff and Beauty an Interview with Laura Letinsky. [online] Available at: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=bdf2af88-c1ce-451d-bc3b-5cae759ed7a7%40sessionmgr4010 [Accessed 4 Apr. 2018].

McGuire, K. (2012). Laura Letinsky: Venus Inferred | The Chicago Blog. [online] Pressblog.uchicago.edu. Available at: http://pressblog.uchicago.edu/2012/10/11/laura-letinsky-venus-inferred.html [Accessed 4 Apr. 2018].

Bryson, Norman, Alison M. Gingeras, Dave Eggers, Kara Vander Weg, Rose Dergan, and John Currin. John Currin. New York, NY: New York, N.Y., 2006.

Currin, John, Robert Rosenblum, Staci Boris, and Rochelle Steiner. John Currin. Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2003.

Stover, William, Cheryl A. Brutvan, and John Currin. John Currin Selects with William Stover. Boston: MFA Publications, 2003.

0 notes

Photo

@Glasstire : Join the Houston Art Gallery Association for a conversation between Houston collector and gallerist Gus Kopriva, artist Philip Karjeker, and critic Raphael Rubinstein at Gallery Sonja Roesch. April 2, 7pm https://t.co/dYxcPFBnHk https://t.co/jSOnIMYdrX (via Twitter http://twitter.com/Glasstire/status/1112742925161631744)

0 notes

Text

April 30 in Music History

1717 Birth of composer Guillaume Gommaire Kennis.

1728 FP of Handel's "Tolomeo, rè di Egitto" London.

1757 FP of Giardini's "Rosmire" London.

1781 FP of Salieri's "Der Rauchfangkehrer" Lustspiel, Vienna.

1792 Birth of composer Johann Friedrich Schwencke.

1805 FP of Boieldieu's "La Jeune Femme colère" St. Petersburg.

1837 Birth of composer Alfred Gaul.

1843 Birth of French soprano Hortense Schneider in Bordeaux.

1848 Birth of German soprano Marie Hanfstangel in Breslau.

1855 Death of English opera conductor and composer Henry Rowley Bishop.

1855 FP of Hector Berlioz's Te Deum. The church of St. Eustache in Paris.

1857 FP of Offenbach's "Dragonette" Paris.

1870 Birth of Austro-Hungarian composer Franz Lehar in Komaron.

1871 Birth of American soprano Louise Homer in Shadyside, Pittsburgh, PA.

1873 FP of Dubois' "La Guzla de l'émir" Paris.

1883 Death of violinist and founder of the Rosa Opera Co, Carl Rosa in Paris. 1883 Birth of composer David John de Lloyd.

1884 Birth of American composer Albert Israel Elkus.

1884 Birth of German tenor Georg Baldszun in Berlin.

1885 Birth of Italian composer and futurist painter Luigi Russolo.

1886 Birth of English composer, pianist Frank Merrick in Clifton,

1889 Birth of American composer and conductor Chalmers Clifton. 1889 Birth of composer Acario Cotapos.

1889 Birth of composer Rudolph Hermann Simonsen.

1902 Birth of composer Andre-François Marescotti.

1902 Birth of composer Rudolf Wittelsbach.

1902 FP of Debussy's opera Pelleas and Melisande in Paris at the Opera Comique. Mary Garden as Melisande. Jeanne Gerville-Réache as Geneviève.

1903 Birth of German composer Gunther Raphael.

1903 Victor records release it's first Red Seal recording.

1911 Birth of composer Hans Studer.

1911 Debut of the 10-year-old violinist, Jascha Heifetz in St. Petersburg. 1912 Death of Czech composer Frantisek Kmoch.

1916 Birth of soprano Alda Noni in Trieste.

1916 Birth of American conductor Robert Shaw in Red Bluff, Iowa.

1917 FP of Mascagni's "Lodoletta" Rome.

1922 Death of French tenor Louis Cazette.

1925 FP of Paul Hindemith's Kammermusik No. 3, Op. 36, no. 2. The composer conducting with Rudolf Hindemith, a cellist in Bochum, Germany.

1925 FP of Standford's "The Traveling Companion" in Liverpool, an amateur performance.

1929 Birth of Italian tenor Doro Antonioli.

1931 Birth of Italian bass Ferruccio Mazzoli.

1932 Birth of composer Anton Larrauri.

1934 Birth of American baritone William Chapman in Los Angeles.

1939 FP of Weill's "Railroads on Parade" NYC.

1932 Opening of the first Yaddo, Festival of Contemporary Music at Saratoga Springs, NY.

1934 FP of Igor Stravinsky's opera Persephone. Ida Rubinstein, speaker, and the composer conducting at the Paris Opéra.

1937 Death of Dutch baritone Carel Van Hulst.

1937 FP of U. Gadzhibekov's "Kyor-Oglu" Moscow.

1939 Birth of American violinist and composer Ellen Taaffe Zwilich in Miami.

1941 Birth of Spanish conductor Luis Antonio Garcia Navarro in Valencia,

1944 Birth of Russian violinist Lydia Mordkovitch.

1951 Death of soprano Désirée Ellinger.

1951 Death of American soprano Lucy Gates.

1956 Birth of composer Adrian Williams.

1968 Death of English baritone Clive Carey.

1970 Birth of Spanish composer Josué Bonnin de Góngora in Madrid.

1970 Birth of composer Brian W. Ogle.

1970 Death of composer Hall Francis Johnson in NYC.

1973 FP of Lou Harrison's Concerto for Organ, at San Jose State University, with organist Philip Simpson.

1974 FP of Samuel Barber's Three Songs, op 45. D. Fischer-Dieskau, Chamber Music Society, Lincoln Center, NYC.

1979 FP of Harbison's "Full Moon in March" Cambridge, MA. 1991 FP of Ellen Taaffe Zwilich's Bass Trombone Concerto. Charles Vernon with the Chicago Symphony, Daniel Barenboim conducting.

1994 FP of John Harbison's String Quartet No. 3. Lydian String Quartet at Brandeis University in Waltham, MA.

2000 Death of German-American composer Bernhard Heiden.

2003 FP of Augusta Read Thomas' Sun Threads. Avalon String Quartet, Lincoln Center, NYC

1 note

·

View note

Text

Minha pequena lista de crushes

1. Chris Hemsworth

2. Brock O'Hurn

3. Chris Evans

4. Henry Cavill

5. Chris John Millington

6. Luke Bracey

7. Travis Fimmel

8. Josh Hartnett

9. Sebastian Stan

10. Raphael Sander

11. Brant Daugherty

12. Jason Momoa

13. Boyd Holbrook

14. Ronen Rubinstein

15. Corey Taylor

16. Zac Efron

17. Chris Pratt

18. Colin O'donoghue

19. Colin Firth

20. Colin Donnell

21. Kit Harington

22. Scott Eastwood

23. Sam Claflin

24. Liam Hemsworth

25. Bradley Cooper

26. Jensen Ackles

27. Landon Liboiron

28. Channing Tatum

29. Jake Gyllenhaal

30. Armie Hammer

31. Gerard Butler

32. Hugh Jackman

33. Dan Stevens

34. Heath Ledger

35. Michel Huisman

36. Adam Gontier

37. Jared Leto

38. Mike Vogel

39. Chalie Cox

40. Jared Padalecki

41. Vinnie Woolston

42. Ian Somerhalder

43. Charlie Puth

44. Rodrigo Hilbert

45. Charlie Hunnam

46. Aaron Taylor-Johnson

47. Garrett Hedlund

48. Paul Rudd

49. Beau Mirchoff

50. Patrick Wilson

51. Patrick Dempsey

52. Chris Pine

53. Kevin Zegers

54. Matthew Daddario

55. Alexander Ludwig

56. Robbie Amell

57. Glen Powell

58. Kellan Lutz

59. Cory Monteith

60. Alex Pettyfer

61. Matthew Bomer

62. Chace Crawford

63. Logan Lerman

64. Wes Bentley

65. Jude Law

66. Boyd Holbrook

67. Nick Wechsler

68. Jeremy Sumpter

69. Ronen Rubinstein

70. Brandyn Farrell

71. Luke Mitchell

72. Avan Jogia

73. Brant Daugherty

74. Diego Boneta

75. Andre Hamann

76. Jack Falahee

77. D.J Cotrona

78. Klebber Toledo

79. André Bankoff

80. Jai Courtney

81. Oliver Jackson-Cohen

82. Zachary Levi

83. Sam Heughan

84. Kim Seok-jin

85. Jeon Jung-kook

86. Kim Tae-hyung

87. Christopher Bang

88. Diego Barueco

89. Ken Bek

90. Clive Standen

91. Taron Egerton

92. Lim Jae-beom

93. Kim Jun-myeon

94. Kang Hyung-gu

95. Im Chang-kyun

96. Lee Joo-heon

97. Jackson Wang

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

'9-1-1 Lone Star' is Now Hiring Actors in Austin, Texas

‘9-1-1 Lone Star’ is Now Hiring Actors in Austin, Texas

‘9-1-1 Lone Star‘ casting call for photo doubles in Austin, Texas.

Casting directors are now hiring actors, models, and talent to work on Thursday, November 14th, Friday, November 15th and Saturday, November 16th in Austin, Texas.

Producers are seeking the following types:

Rob Lowe – 5’10”

Liv Tyler – 5’10”

Ronen Rubinstein – 5’11”

Jim Parrack – 6’4″

Natacha Karam – 5’4″

Raphael Silva – 6′

Brian…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Books posted in August 2019

Here is the list of the 58 books that I posted on this site in August 2019. The image above contains some of the covers. The bold links take you to the book’s page on Amazon; the “on this site” links to the book’s page on this site.

The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer (on this site)

Ancient Texts and Modern Readers; by Gideon Kotzé, Christian S. Locatell and John A. Messarra (on this site)

Caging Skies by Christine Leunens (on this site)

Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage: Selected Stories by Bette Howland (on this site)

Covenant & Conversation: Deuteronomy: Renewal of the Sinai Covenant by Jonathan Sacks (on this site)

The Cyprus Detention Camps: The Essential Research Guide by Yitzhak Teutsch (on this site)

A Dreidel in Time: A New Spin on an Old Tale by Marcia Berneger (on this site)

Eternity Now: Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady and Temporality by Wojciech Tworek (on this site)

Forest with Castanets by Diane Mehta (on this site)

From Behind the Curtain: A Chassidic Guide To Finding Hashem by Akiva Bruck (on this site)

From Metaphysics to Midrash: Myth, History, and the Interpretation of Scripture in Lurianic Kabbala by Shaul Magid (on this site)

God’s Voice from the Void: Old and New Studies in Bratslav Hasidism by Shaul Magid (on this site)

A Guide to the Zohar by Arthur Green (on this site)

Heavenly Powers: Unraveling the Secret History of the Kabbalah by Neil Asher Silberman (on this site)

Hillel Takes a Bath by Vicki L. Weber (on this site)

The Hotel Neversink by Adam O’Fallon Price (on this site)

In the Full Light of the Sun by Clare Clark (on this site)

In the Warsaw Ghetto by Glenn Haybittle (on this site)

The Invisible Jewish Budapest: Metropolitan Culture at the Fin de Siècle by Mary Gluck (on this site)

Jewish Religious Architecture; From Biblical Israel to Modern Judaism by Steven Fine (on this site)

The Jews in Italy: Their Contribution to the Development and Diffusion of Jewish Heritage (on this site)

Jocie: Southern Jewish American Princess, Civil Rights Activist by Jocelyn Dan Wurzburg (on this site)

The Juggler & the King: The Jew and the Conquest of Evil: An Elaboration of the Vilna Gaon’s Insights Into the Hidden Wisdom of the Sages by Aharon Feldman (on this site)

Kabbalah by Gershom Scholem (on this site)

Kafka and Kabbalah by Karl-Erich Grozinger (on this site)

Karl Marx: Philosophy and Revolution by Shlomo Avineri (on this site)

The Limits of the World by Jennifer Acker (on this site)

Masada: From Jewish Revolt to Modern Myth by Jodi Magness (on this site)

The Miracle of the Seventh Day: A Guide to the Spiritual Meaning, Significance, and Weekly Practice of the Jewish Sabbath by Adin Steinsaltz (on this site)

The Morning Gift by Eva Ibbotson (on this site)

Mystical Sociology: Toward Cosmic Social Theory (After Spirituality) by Philip Wexler (on this site)

Once upon an Apple Cake: A Rosh Hashanah Story by Elana Rubinstein (on this site)

The Only Woman in the Room by Marie Benedict (on this site)

Opening the Tanya: Discovering the Moral and Mystical Teachings of a Classic Work of Kabbalah by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz (on this site)

A Philosopher of Scripture The Exegesis and Thought of Tanḥum ha-Yerushalmi by Raphael Dascalu (on this site)

Philosophy and Kabbalah: Elijah Benamozegh and the Reconciliation of Western Thought and Jewish Esotericism by Alessandro Guetta and Helena Kahan (on this site)

Religious Thought of Hasidism: Text and Commentary by Norman Lamm (on this site)

The Right to Difference: French Universalism and the Jews by Maurice Samuels (on this site)

The Sabbath in the Classical Kabbalah by Elliot K. Ginsburg (on this site)

The Secret Life: A Book of Wisdom from the Great Teacher by Jeffrey Katz (on this site)

Secrets From the Lost Bible: Hidden Scriptures Found by Kenneth Hanson (on this site)

Secularizing the Sacred: Aspects of Israeli Visual Culture by Alec Mishory (on this site)

The Siege of Tel Aviv by Hesh Kestin (on this site)

Someday We Will Fly by Rachel DeWoskin (on this site)

Sontag: Her Life and Work by Benjamin Moser (on this site)

Splitsville by Howard Akler (on this site)

Studies in Ecstatic Kabbalah by Moshe Idel (on this site)

These Are the Words: A Vocabulary of Jewish Spiritual Life by Arthur Green (on this site)

Thirteen Petalled Rose: A Discourse on the Essence of Jewish Existence And Belief by Adin Steinsaltz (on this site)

Thong of Thongs: 69 Sexy Jewish Stories by Kitty Knish (on this site)

Tough Luck: Sid Luckman, Murder, Inc., and the Rise of the Modern NFL by R. D. Rosen (on this site)

Traces Of Sepharad (Huellas De Sefarad) Etchings Of Judeo Spanish Proverbs by Marc Shanker (on this site)

Understanding the Spiritual Meaning of Jerusalem in Three Abrahamic Religions by Antti Laato (on this site)

An Unorthodox Match by Naomi Ragen (on this site)

Violinist in Auschwitz by Jacques Stroumsa (on this site)

We Stand Divided: The Rift Between American Jews and Israel by Daniel Gordis (on this site)

Who Wants to Be A Jewish Writer?: And Other Essays by Adam Kirsch (on this site)

Zohar: Annotated & Explained by Daniel Chanan Matt (on this site)

The post Books posted in August 2019 appeared first on Jewish Book World.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2ATyPQx via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note