#Ranko Hanai

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Films Watched in 2023: 120. 姿三四郎/Sanshiro Sugata (1943) - Dir. Akira Kurosawa

#姿三四郎#Sanshiro Sugata#Akira Kurosawa#Denjirō Ōkōchi#Susumu Fujita#Yukiko Todoroki#Ryūnosuke Tsukigata#Takashi Shimura#Ranko Hanai#Films Watched in 2023#My Post

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now watching:

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Yamada Isuzu in "Fighting Tobi", 1939, with Ranko Hanai

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Masayuki Mori in Love Letter (Kinuyo Tanaka, 1953)

Cast: Masayuki Mori, Juzo Dosan, Yoshiko Kuga, Jukichi Uno, Kyoko Kagawa, Shizue Natsukawa, Kinuyo Tanaka, Chieko Seki, Ranko Hanai, Chieko Nakakita, Keisuke Kinoshita. Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita, based on a novel by Fumio Niwa. Cinematography: Hiroshi Suzuki. Art direction: Seigo Shindo. Film editing: Toshio Goto. Music: Ichiro Saito.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ginza Cosmetics / Ginza keshō (1951, Mikio Naruse)

銀座化粧 (成瀬巳喜男)

12/6/20

#Ginza Cosmetics#Ginza Kesho#Nikio Naruse#Kinuyo Tanaka#Ranko Hanai#Yuji Hori#Kyoko Kagawa#Eijiro Yanagi#Eijiro Tono#Haruo Tanaka#Japanese#drama#Japanese Golden Age#nightclub#nightlife#hostesses#Ginza#Tokyo#mother and son#money#sisters#bar#gendaigeki

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sanshiro Sugata | Akira Kurosawa | 1943

Yoshio Kosugi, Susumu Fujita, Ranko Hanai, et al.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE IDOLM@STER CINDERELLA GIRLS 7thLIVE TOUR Special 3chord♪

Further information regarding the「THE IDOLM@STER CINDERELLA GIRLS 7thLIVE TOUR Special 3chord♪」7th Live has been announced! The cast list for Glowing Rock! occurring in Kyocera Dome on the 15th and 16th of February 2020 has been released!

Ayaka Ohashi ( Uzuki Shimamura ), Ayaka Asai ( Mirei Hayasaka ), Mayumi Kaneko ( Rina Fujimoto ), Kaoru Sakura ( Chitose Kurosaki ), Risa Sekiguchi ( Chiyo Shirayuki ), Natsumi Takamori ( Miku Maekawa ), Ricca Tachibana ( Sae Kobayakawa ), Atsumi Tanezaki ( Kyoko Igarashi ), Minami Tsuda ( Miho Kohinata ), Hiyori Nitta ( Karin Domyoji ), Yui Makino ( Mayu Sakuma ), Marie Miyake ( Nana Abe )

Ayaka Fukuhara ( Rin Shibuya ), Shiki Aoki ( Asuka Ninomiya ), Ruriko Aoki ( Riina Tada ), Maaya Uchida ( Ranko Kanzaki ), Chiyo Ousaki ( Koume Shirasaka ), Misa Kayama ( Tamami Wakiyama ), Amina Sato ( Arisu Tachibana ), Aya Suzaki ( Minami Nitta ), Haruka Chisuga ( Ryo Matsunaga ), Nao Touyama ( Mizuki Kawashima ), Mai Fuchigami ( Karen Hojo ), Eriko Matsui ( Nao Kamiya ), Tomo Muranaka ( Aki Yamato ), Ru Thing ( Syuko Shiomi ), Mina Nakazawa ( Yukimi Sajo )

Sayuri Hara ( Mio Honda ), Masumi Tazawa ( Ayame Hamaguchi ), Miharu Hanai ( Tomoe Murakami ), Yuko Hara ( Takumi Mukai ), Satsumi Matsuda ( Syoko Hoshi ), Seena Hoshiki ( Riamu Yumemi )

more information will be announced when released.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ginza Cosmetics (1951, Japan)

Mikio Naruse is not a name that many casual fans of cinema will recognize. But Naruse, whose films are regularly compared to those directed by the more familiar names like Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, and Ozu, has a tremendous passion – be it sorrow or a tremendous anger – beneath an Ozuesque calm. His films are noted for their pessimism; many of which belong to a genre/subgenre known as Shomin-geki – a faux Japanese word invented by Western film scholars that is mean to denote a working class drama. Those who are more fluent in classic Japanese cinema and those interested in diving into Naruse’s films should note that Ginza Cosmetics – which stars Kinuyo Tanaka, Ranko Hanai, Kyoko Kagawa, Eijiro Yanagi, Eijiro Tono, and Yuji Hori – as my first Naruse film of the two I have seen so far (1953′s Wife being the other). For Ginza Cosmetics, this concentration on the working class – class is more of a concern to Naruse than to the likes of Japan’s directorial trinity – is affected by a post-War environment that saw many trying to make sense of themselves and others around them in an evolving, Westernizing order.

Yukiko Tsuji (Kinuyo Tanaka) is a forty-something year-old geisha who is struggling to find a steady income elsewhere while attempting to care for her only child. Her duties include being a welcoming bar hostess, an entertainer, and sometimes includes obliging those who are being more than forward to her. Knowing no other feasible means to support herself and her child, Yukiko is resigned that her luckless lifestyle will always revolve around this cycle of men demeaning her very character and agency. As a geisha in a Japan leaning towards Western culture and away from the Imperial, Meiji, and Edo eras, there is a thinly-veiled repugnance towards Yukiko’s line of work than ever before. Geishadom is considered indecent, unbecoming of a woman, let alone someone in her middle ages raising a child without a husband. The film moves at its leisure, reflective and quiet in its observations until Yukiko meets Kyosuke (Hori). Recalling a poem that Yukiko vaguely remembers and as the two spend a moment stargazing – she can only spot Ursa Major – her guard is let down, just for a moment. Where Takashi Shimura’s Watanabe in ikiru has been so consumed in his work that he has forgotten the beauty of a sunset, Tanaka’s Yukiko has forgotten about the glimmering night sky and of life before she was a geisha.

Released in the final year of the American occupation of Japan, changing Japanese attitudes towards geishas – thanks to both its Imperial era and the Americans’ presence – are restrained, but more negatively pronounced than in typical from other Japanese films depicting geishas (Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu, though not taking place in a contemporary Japan, comes to mind). Yukiko claims that she is a war widower to retain any dignity in public. The American and European names in neon that we saw in the Ginza district while Yukiko and Kyosuke stroll the night away are even more reminders that, as Japan recovers from World War II and begins to resemble anything unlike Yukiko or Kyosuke have ever experienced, they realize that society is leaving them behind. Kyosuke, in his romantic recitations of poetry and knowledge of constellations (as a Southern California native who only knows of light pollution, I’ve always been fascinated by those who possess the latter, even in films) retains his morals that, though well-intentioned, are naive and are rooted in traditional Japanese values. The Ginza district, which incurred damage during World War II, is even brighter than before, its buildings taller than before, its customers livelier than ever before. Nations that lose wars are those most willing to forget about them. Amid what was once rubble, Yukiko ruminates over how Ginza fared during the war and how quickly the burgeoning crowds looking for dinner, drinks, and some seedier entertainment have forgotten what once was. They admire the neon signs; she and Kyosuke admire the stars before Tokyo’s newest lights make most of them disappear.

Due to economic and personal circumstance, Yukiko has never been given a chance to prosper, to escape a life where she is objectified daily. “Most men are beasts,” she confides with another woman. The men, including Kyosuke at times, are attempting to reorient themselves where traditional gender roles – many women had been newly employed in Japanese factories while millions of young men were sent to fight in East and Southeast Asia as well as the Pacific – have been fractured. The male assertions of economic, sexual, and social power are a response to this. For Yukiko, who, as far we know, has never been anything other than a talented geisha, this represents a problem that lingers even when she is not working, even as she speaks to her child and asks – in that universal daily routine of parenthood – how the day went. When the possibility of escape, perhaps love, emerges, it departs as fleetingly as this film all-too abruptly concludes without too much reflection on what this possibility has meant to Yukiko. Is she too numbed over decades at her occupation to ponder about what has so quickly departed?

Kinuyo Tanaka, one year from her most heartbreaking role in Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu (1952), plays a character that – unlike Oharu – refuses to wallow in the shaming from others, the possibility of platonic or romantic connections that have passed her by, and the indignities that men and other women have forced upon her or have gossiped about her in hushed tones. Not that Yukiko has never dreamt of being somewhere else, of being something else. No one bothers to be compassionate enough towards her to help; those willing to help are unable to as it might look indecent. Tanaka’s demeanor is not sorrowful, but contemplative and just – if this makes any sense – being just there. There is a restrained beauty in this performance, an acceptance of Yukiko’s life station and its inescapability.

Mikio Naruse’s films are freed from the aesthetic rigidity of a film like Mizoguchi’s or Ozu’s. His camera is more dynamic, more aligned to Hollywood Studio System and European conventions than the two aforementioned directors. For first-time Naruse watchers, I can imagine that it won’t be the visuals that will be jarring, but how pessimistic plot developments are presented when they arise. Ginza Cosmetics doesn’t delve into how Yukiko’s relations to men – especially Kyosuke – affect her and are defined by her past interactions and experiences. Is there a willing forgetfulness within Yukiko that developed, like within so many Japanese who survived World War II, as a survival mechanism? Whatever it may be, it is never developed and Ginza Cosmetics is deprived of emotional punches as a result.

Ginza Cosmetics will be a difficult find outside of – as of the publishing of this write-up – Hulu’s streaming service – as Naruse’s films are largely unavailable in North America. The rights to almost all of his films are held by Janus Films/Criterion Collection (I saw the film as it made its television debut on Turner Classic Movies, which has a close working relationship with Janus), yet so few film academics, critics, and even the most committed disciples of Japanese cinema have ever encountered a single Naruse film. If Ginza Cosmetics is not one of Naruse’s most acclaimed films, then it is reflective of something more profound that awaits – and if you want to hear more about what I think about Naruse, you are in luck, as I will be writing on Wife (1953) sometime soon. For even what might be considered a lesser effort, his directorial vision is unlike anything I’ve encountered and is something I would like to see more of.

My rating: 7/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating.

#Ginza Cosmetics#Mikio Naruse#Kinuyo Tanaka#Ranko Hanai#Kyoko Kagawa#Eijiro Yanagi#Eijiro Tono#Yoshihiro Nishikubo#Yuji Hori#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

1 note

·

View note

Video

Sazen Tange and the Pot Worth a Million Ryo / 山中貞雄 - 丹下左膳餘話 百萬兩の壺(1935) (by eiganihon)

0 notes

Photo

Japanese actress Ranko Hanai , early 1930s

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kinuyo Tanaka in Ginza Cosmetics (Mikio Naruse, 1951)

Cast: Kinuyo Tanaka, Ranko Hanai, Yuji Hori, Kyoko Kagawa, Eijiro Yanagi, Eijiro Tono, Yoshihiro Nishikubo, Haruo Tanaka. Screenplay: Matsuo Kishi, based on a novel by Tomoichiro Inoue. Cinematography: Akira Mimura. Art direction: Takashi Kono. Film editing: Hidetoshi Kasama. Music: Seiichi Suzuki.

I'm not entirely sure what the title, Ginza Cosmetics, means. But I think it has something to do with putting on a good face when things are troubled inside. That applies to the protagonist, Yukiko (the great Kinuyo Tanaka), a bar hostess struggling to raise her young son, Haruo (Yoshihiro Nishikubo), and at the same time trying to keep the bar she works in from going out of business. But it also applies to the Ginza itself, the bustling shopping and entertainment district of Tokyo. At one point, Yukiko is showing a young man from the country around the city, and points out how much of the area he finds oppressively noisy and crowded had been leveled during the war: The Ginza itself has put on a new face, hiding its scars. Mikio Naruse's film is an account of several days in Yukiko's life, a character study without melodrama. She has a few moments of crisis: Haruo, who is usually a quiet and studious child who looks after himself (with the aid of a few neighbors) while Yukiko goes to work, once wanders off for a few hours, to her distress. And she is almost raped by an old acquaintance whom she goes to in search of money to help the bar's owner from having to sell it. There's also some tension among the women who work in the bar when the marriageable young man from the country comes to visit one of them. At the end, life goes on without the usual narrative resolution, and if you're like me you feel you've had a privileged glimpse into another world and another life.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

An image of "Ranko Hanai" from the magazine article of the May special magazine "Movie No Tomo" published in 1935 . Ranko Hanai (1918-1961) was born in Osaka and first staged as a child in 1923 (Taisho 12) .In 1928 (Showa 3) she joined Kamo Matsutakeshita and made a movie debut in the name of Reiko Shimizu, 1931 (Showa 6).

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

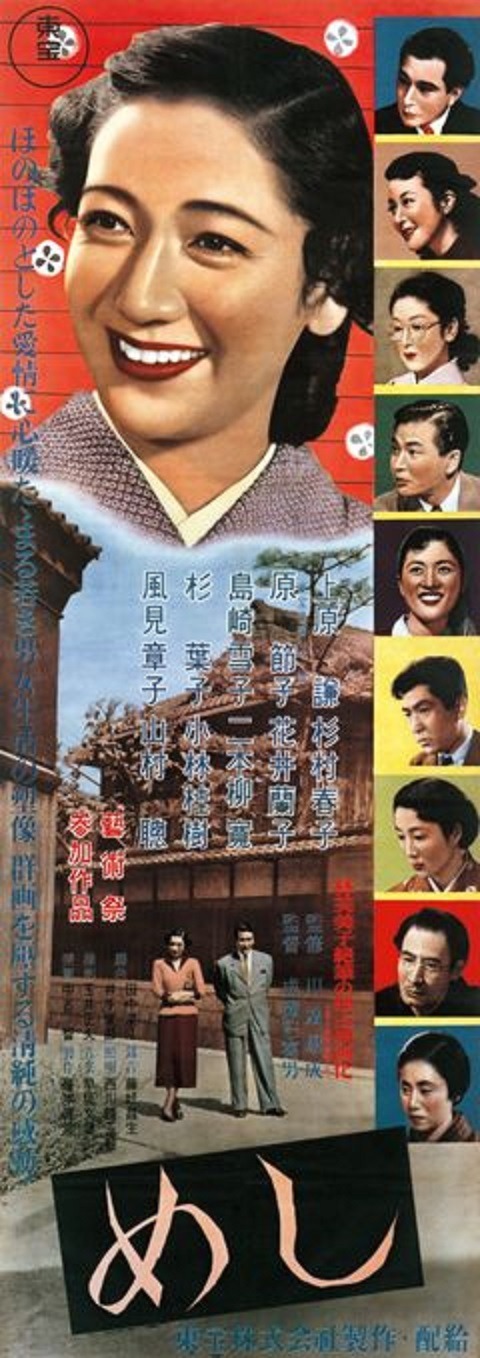

Repast / Meshi (1951, Mikio Naruse)

めし (成瀬巳喜男)

2/23/22

#Repast#Meshi#Mikio Naruse#Setsuko Hara#Ken Uehara#Haruko Sugimura#Yukiko Shimazaki#Yoko Sugi#Akiko Kazami#Ranko Hanai#Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi#drama#50s#Japanese#Japanese Golden Age#gendaigeki#Osaka#marital problems#jealousy#cats#relatives#marriage#visitors

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Japanese actress Ranko Hanai, late 1930s

130 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ryunosuke Tsukigata and Susumu Fujita in Sanshiro Sugata (Akira Kurosawa, 1943) Cast: Susumu Fujita, Denjiro Okochi, Yukiko Todoroki, Ryunosuke Tsukigata, Takashi Shimura, Ranko Hanai, Sugisaki Aoyama, Ichiro Sugai, Yoshio Kusugi, Kokuten Kodo. Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa, based on a novel by Tsuneo Tomita. Cinematography: Akira Mimura. Art direction: Masao Tozuka. Film editing: Toshio Goto, Akira Kurosawa. Music: Seiichi Suzuki. You know the plot: A talented, cocky young newcomer takes on the old pros and gets his ass kicked, but he learns self-discipline and becomes a winner. You've seen it played out with young doctors, lawyers, musicians -- it's even the plot of Wagner's Die Meistersinger -- and others challenging the established traditions. But mostly it's the plot for what seems to be about half of the sports movies ever made, including Akira Kurosawa's first feature, Sanshiro Sugata. It's also a film about the conflict between rival martial arts disciplines, jujitsu and judo, but fortunately you don't need to know much about the nature of the conflict to follow the film. From what I gather from reading the Wikipedia entry on judo, the founder of that discipline, Jigoro Kano, wanted to give jujitsu a philosophical underpinning that would put an emphasis on self-improvement for the betterment of society, and he called it judo because "do," like the Chinese "tao," means road or path. Kano's renaming was meant to shift the emphasis from physical skill to spiritual purpose. In Kurosawa's film, young Sanshiro (Susumu Fujita) comes to town wanting to find someone to teach him jujitsu, and signs up with a teacher who accepts a challenge from the judo master Shogoro Yano (Denjiro Okochi) -- the name is an obvious twist on "Jigoro Kano." Sanshiro watches as not only the teacher but all of the other members of his dojo are defeated -- in fact, tossed into the river -- by Yano. Whereupon Sanshiro becomes a follower of Yano's, but has to undergo some defeats and a cold night spent in a muddy pond before he gets the idea of what judo is all about. The film was not a big hit with the wartime Japanese censors, who wanted more aggression and less philosophy in their movies, so 17 minutes were cut from it, never to be seen again. In the currently available print, the missing material is summarized on title cards, but what's left is more than enough to show that Kurosawa arrived on the scene as a full-blown master director. His camera direction is superb, and he knows how to tell a story visually. For example, when Sanshiro joins up with Yano, he kicks off his geta, his wooden clogs, so he can pull Yano's rickshaw more efficiently. Kurosawa cuts to a passage-of-time montage in which we see one of the abandoned geta lying in the road, then in a mud puddle, covered with snow, then tossed aside as spring comes. The film's crucial scene is a showdown between Sanshiro and his jujitsu rival, Higaki (Ryunosuke Tsukigata), in a field of tall grasses, swept by wind with rushing clouds overhead; it's a spectacular effect, even if the battle turns out to be a bit anticlimactic. However much the censors may have disliked it, audiences were enthusiastic enough that Kurosawa was persuaded to make a sequel.

Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two (Akira Kurosawa, 1945)

Cast: Susumu Fujita, Denjiro Okochi, Ryunosuke Tsukigata, Akitake Kono, Yukiko Todoroki, Soji Kiyokawa, Masayuki Mori, Kokuten Kodo, Osman Yusuf, Roy James. Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa, based on a novel by Tsuneo Tomita. Cinematography: Takeo Ito. Production design: Kazuo Kubo. Film editing: Akira Kurosawa. Music: Seiichi Suzuki.

Patched together from what aging film stock could be gathered during the end-of-war shortages in Japan, and interrupted during its filming by bombing raids, Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two was a labor imposed on the writer-director by the studio, Toho, and Kurosawa's lack of enthusiasm for the project shows. The story is routine: Sanshiro has helped judo triumph over jujitsu as the primary Japanese martial art, but he has gone into retreat for several years, honing his spirituality. But one day he comes across an American sailor (Osman Yusuf) beating up a rickshaw driver -- a job he once took on himself -- and thrashes the bully. This brings him to the attention of a promoter who wants to stage a fight between the judo master and an American boxer named William Lister (Roy James). Eventually, after another fighter is beaten to a pulp by Lister, Sanshiro gives in and thrashes Lister, giving the prize money to the fighter who had been beaten. Meanwhile, his old opponent, Gennosuke Higaki (Ryunosuke Tsukigata), whom he defeated at the end of the first film, warns him that his brothers, Tesshin (also Tsukigata) and Genzaburo Higaki (Akitake Kono), are out to revenge themselves for Gennosuke's defeat. They are masters of karate, which originated on Okinawa and was just making its way into mainland Japan at the time when the film is set, the late 19th century. Gennosuke gives Sanshiro a scroll depicting the basics of karate to help him in the eventual fight with the brothers. Naturally, the film concludes with a fight between Sanshiro and Tesshin -- the other brother is recovering from an epileptic seizure -- that takes place in the snow, an echo of the fight in the original film with Gennosuke in a windswept field of tall grasses. This battle is the only part of the film that shows much commitment on the part of Kurosawa, who insisted that the principals fight barefoot in the snow, not without many complaints from the actors. Unfortunately, the poor film stock, unable to provide shades of gray, turns much of this fight into a battle of silhouetted figures. Much has been made of the propaganda in the film, particularly the portrayal of the hapless American sailor and boxer, but Kurosawa, no lover of the imperial regime, manages to shift the film's emphasis to the fearsomely wild Higaki brothers.

3 notes

·

View notes