#R. F. Kuang

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Book Review 68 - Babel by R. F. Kuang

Overview

I came to Babel with extremely little knowledge about the actual contents of the book but a deep sense of all the vibes swirling around its reception – that it was robbed of a Hugo nomination (if the author didn’t outright refuse it), that it’s probably the single buzziest and most Important sf/f release of 2022, that it was stridently political, and plenty more besides. I also went in having mostly enjoyed The Poppy War series and being absolutely enamoured by the elevator pitch of an alternate history Industrial Revolution where translation is literally magic. And, well-

It is wrong to say I hated this book, but only because keeping track of my complaints and starting organize this review in my head was entertaining enough to keep me invested in the reading experience.

The story is set in an alternate 1830s, where the rise of the British Empire relies upon the dominance of its translators, as it is the mixture of translation and silverworking, the inscription of match-pairs in different languages on bars of worked silver and the leveraging of the ambiguity and loss of meaning between them that fuels the world’s magic. The protagonist is pluckted from his childhood home in Canton after his family dies in a cholera outbreak and whisked away to the estate of Professor Lowell, an Oxford translator he quickly realized is his unacknowledged father. He’s made to choose an English name (Robin Swift) and raised and tutored as a future translator in service to the Empire.

The meat of the story is focused on Robin’s education in Oxford, his relationship with the rest of his cohort, and his growing radicalization and entanglement with the revolutionary Hermes Society. Things come to a head when in his fourth year the cohort is sent back to Canton to, well, help provoke the first Opium War, though none of them aware of that. The final act follows the fallout of that, by which I mean it lives up to the full title of “Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators' Revolution”.

To be clear, this was technically a very accomplished book. The writing never dragged and the prose was, if not exactly lyrical, always clear and often evocative. Despite the breadth of space and time the story covers, I never had any complaints about the pacing – and honestly, the ending was, dramatically speaking, one of the more natural and well-executed ones I’ve read recently. It’s very well-constructed.

All that being said – allow me to apologize for how the rest of this is mostly just going to be a litany of complaints. But the book clearly believes itself to be an important and meaningful work of political art, which means I don’t feel particularly bad about holding it to high standards.

Narrative Voice

To start with, just, dear god the tone. This is a book with absolutely zero faith in its audience’s ability to reach their own conclusions, or even follow the symbolism and implication it lays down. Every important point is stated outright, repeated, and all but bolded and underlined. In this book set in 1830s England there are footnotes fact-checking the imperialists talking heads to, I guess, make sure we don’t accidentally become convinced by their apologia for the slave trade? Everything is just relentlessly didactic, in a way that ended up feeling rather insulting even when I agreed with the points Kuang was making.

More than that, and this is perhaps a more subjective complaint but – for an ostensible period piece, the narrative voice and perspective just felt intensely modern? This was theoretically an omniscient third person book, with the narrative voice being pretty distinct from any of the actual characters – with the result that the implicit narrator was instead the sort of person of spends six hours a day getting into arguments on twitter and for this effort calls themselves a progressive activist. The identities of all the characters – as delivered by the objective narration – were all very neat and legible from the perspective of someone at a 2022 HR department listing how diverse their team was, which was somewhere between a tragic lost opportunity to show how messy and historical racial/ethnic/national identities are and outright anachronistic, depending. (This was honestly one of the bigger disappointments, coming from Kuang’s earlier work. Say what you will of The Poppy War series, the narration is with Rin all the way down, and it trusts the reader enough not to blink.) More than that it was just distracting – the narration ended up feeling like an annoying obstacle between me and the story, and not in any fun postmodern way either.

Characters

Speaking of the cast – they simply do not sound or feel like they actually grew up in the 19th century. Now, some modernization of speech patterns and vocabulary and moral commensense is just the price of doing business with mass market period pieces, granted, but still – no 19th century Anglo-Indian revolutionary is going use the phrase ‘Narco-military state’ (if for no other reason than we’re something like a century early for ‘narco-state’ to be coined as a term at all). An even beyond feeling out of time most of the characters feel kind of thinly sketched?

Or no, it’s not that the characters are thinly sketched so much as their relationships are. We’re repeatedly, insistently told that these four students are fast friends and closer than family and would happily die for each other, but we’re very rarely actually shown it. This is partly just a causality of trying to skim over a four-year university education in the middle third of one book, I think, but still – the good times and happy moments are almost always sort of skimmed over, summarized in the course of a paragraph or two that usually talk in terms of memories and consequences more than the relationships themselves. The points of friction and the arguments, meanwhile, are usually played out entirely on the page, or at least described in much more detail. In the end you kind of have to just take it as read that any of these people actually love each other, given that at least two of them seem to be feuding at any given point for the entire time they know each other.

Letty deserves some special attention. She’s the only white member of Robin’s cohort at Babel and she honestly feels like less of acharacter and more a collection of tropes about white women in progressive spaces? Even more than the rest, it’s hard to believe the rest of the class views her as beloved ride-or-die found family when essentially every time she’s on screen it’s so she can do a microagression or a white fragility or something. Also, just – you know how relatively common it is to see just, blatantly misogynistic memes repackaged as anti-racist because it specifies ‘white women’? There’s a line in this that almost literally says ‘Letty wasn’t doing anything to disprove the stereotype of woman as uselessly emotional and hysteric’.

Also, she’s the one who ends up betraying the other three and trying to turn them in when they turn revolutionary. Which is probably inevitable given the book’s politics, but as it happened felt like less of the shocking betrayal that it was supposed to be and more just, checking off a box for a dramatic reverse. Of course she turned on them, none of them ever really seemed to even like each other.

As a Period Piece

So, the book is set in the 1830s, in the midst of the industrial revolution and its social fallout, and the leadup to the First Opium War (which is, through the magic of, well, magic ,but also mercantilist economics, make into a synecdoche for British global dominion more broadly). On the one hand, the setting is impeccably researched, recent and relevant historical events are referenced whenever they would come up, and the footnotes are full to bursting with quotes and explanations of texts or cultural ephemera that’s brought up in the narration.

On the other, the setting doesn’t feel authentic in the slightest, the portrayal of the British Empire is bizarrely inconsistent, and all that richly researched historical grounding ends up feeling less like a living world and more like a particularly well-down set for a Doctor Who episode.

The story is incredibly focused around Oxford as a city and a university. There’s a whole author’s note about the research and slight changes made into its geography and I absolutely believe its portrayal as a physical location and the laws about how women were treated and how the different colleges were organized and all that is exactly as accurate as Kuang wanted them to be. The issue is really the people. With the exception of a few cartoonish villains who barely get more than a couple pages apiece, no one feels, sounds like, or acts like they actually belong in the 19th century. The racism the protagonists struggle with all feels much more 21st century than Victorian, and the frame of mind everyone inhabits still comes across more as ‘unusually blatantly racist Englishman’ than 19th century scholars and polymaths.

This is especially blatant as far as religion goes. It’s occasionally mentioned, sure enough, but to the extent anyone actually believes in Christianity it’s of a very modern and disenchanted sort – this is a society that sends out missionaries as a conscious tool of colonial expansion, not because of anything as silly or absurd as actually wanting to spread their gospel. Also like, it’s Oxford, in the nineteenth century. For all the racism the protagonists have to deal with, they should be getting so much more shit from ‘well-meaning’ locals and students trying to save their (one Muslim, one atheist, one probably Christian but black and protective of Haitian Vodou on a cultural level which would be more than enough) souls.

Or, and this is more minor, it is a central conceit of the whole finale that if a few (like, two) determined revolutionaries can infiltrate Babel they’ll be able to take the entire place hostage with barely any trouble. This is because the students and professors there are, basically, whimpy bookworms who’ll faint at the sight of blood and have no stomach for the sort of violence their work actually supports and drives. Which – look, I really don’t want to defend the ruling class of Victorian Britain here, but I’m not sure physical cowardice is really one of their failings, as a group? I mean, there’s an entire system of institutionalized child abuse in the boarding schools they went to to get them used to taking and dealing out violence and abuse. Basically every upper-class sport is thinly disguised military drill or ritual combat (okay, or rowing). Half of them would graduate to immediately running off and invading places for the glory of the queen. I’m not sure two sleep-deprived nerds with knives would actually have been able to cow the crowd here, is what I’m saying. (This would stick out less if the text wasn’t so dripping with contempt for them on precisely these grounds.)

Much less minor are our heroic revolutionaries themselves. And okay, this is more a matter of taste than anything but like – the Hermes Society is an illegal conspiracy of renegade current and former Babel scholars dedicated to using their knowledge of magic and access to university resources to oppose and undermine the British Empire in general and the work of the school in particular. Think Metternich’s worse nightmare, but in Oxford instead of Paris and focused on colonial liberation (continental Europe barely exists for the purposes of the book, Britain is Empire.) So! A secret society of professional revolutionaries in the heydey of just that, with a name that just has to be Hermetic symbolism, who concern themselves with both high politics and metaphysics.

They are just so very, very boring. This is the age of the Conspiracy of the Equals, the Carbonari, the Seasons! The literal Illumanti are still within living memory! Where’s the pageantry, the ritual, the grandiosity? The elaborate initiation rituals and oaths of undying loyalty? They’re so pragmatic, so humble, so (and I know I keep coming back to this) modern. It’s just such an utter wasted opportunity. Even beyond the level of aesthetics, these are revolutionaries with remarkably little positive ideology – the oppose colonialism and racism for reasons they take as self-evident and so don’t feel the need to theorize about it (and talk about them with the vocabulary of a modern activist, because of course they do), but they’re pretty much consciously agnostic as to what world should look like instead. They vaguely end up supporting a sort of petty-bourgeois socialism (in the Marxist sense), but the alliance with Luddites is essentially political convenience – they really don’t seem to have any vision of the future at all, either in England or the various places they claim as homelands.

On Empire and Industrialization

The story is set during the early nineteenth century, so of course the Industrial Revolution is a pretty core part of the background. The Silver Industrial Revolution, technically, since the Babellers translation magic is in this world a key and load-bearing part of it. Despite the addition of miracle-working enhancers and supports to its fundamental technology, the industrial revolution plays out pretty identically to history – right down to the same cities becoming hubs of industry, despite steam engines using enchanted silver instead of coal and thus, presumably, the entire economic and logistical system that brought this particular cities to prominence being totally unrecognizable. This is not a book that’s in any way actually about tracing how something would change history – which isn’t a complaint, to be clear, that’s a perfectly valid creative choice.

It does, however, make it rather galling that the single actually significant difference to history is that the introduction of magic turns the industrial revolution into a Legend of Zelda boss with a giant glowing weak point you can hit to destroy the whole enterprise.

On a narrative level, I get it – it simplifies things and allows for a far happier and more dramatic ending if destroying Babel is not just a symbolic act but also literally sends London Bridge falling down and scuttles the entire royal navy and every mill and factory in Britain. It’s just that I think that by doing so it trades away any chance for actually making interesting commentary on anti-colonial and -capitalist resistance. A world where a single act of spectacular terrorism really can destroy a modern empire is frankly so detached from our world that it ceases to be able to really materially comment upon it.

Like, the principle reason to not take the Luddites as your role models is not that they were morally vicious but that they were doomed – capitalism’s ability to repair damage to infrastructure and fixed goods is legitimately very impressive! Trying to force an entire ruling class not to adopt a technology that makes whoever commits to it tremendous amounts of money (thus, power) is a herculean task even when you have a state apparatus and standing army – adding an ‘off’ button to the lot of it just trades all sense of relevance for a satisfyingly cathartic ending.

(This is leaving untouched how the book just takes it as a given that the industrial revolution was a strictly immiserating force that did nothing but redistribute money from artisans to capitalists. Which certainly tracks as something people at the time would have thought but given how resolutely modern all the other politics in the work are rings really weirdly.)

All of which is only my second biggest issue with how the book presents its successful resistance movement. It all pales in comparison to making the Empire a squeamish paper tiger.

Like, the book hates colonialism in general and the British Empire in particular, the narrative and footnotes are filled with little asides about various atrocities and injustices and just ways it was racist or complicit in some particular atrocity. But more than that it is contemptuous of it, it views the empire as (as the cliche goes) a perpetually rotting edifice that just needs one good kick; that it persists only through the myth of its own invincibility, and has no stomach for violent resistance from within. Which is absolutely absurd, and the book does seem to know it on occasion when it off-handedly mentions e.g. the Peterloo Massacre – but a character whose supposed to be the grizzled cynical pragmatic revolutionary still spouts off about how slave rebellions succeed because their masters aren’t willing to massacre their own property. Which is just so spectacularly wrong on every axis its actually almost offensive.

More importantly, the entire final act of the story relies upon the fact that the British Empire would allow a handful of foreign students seize control of a vital piece of infrastructure for weeks on end and do nothing but try to wait them out as the national physically falls apart around them. Like, c’mon, there would be siege artillery set up and taking shots by the end of week two. As with the Oxford students, the Victorian elite had all manner of flaws – take your pick, really – but squeamishness wasn’t really one of them.

On Magic

So the magical system underlying the whole story is – you know how Machinaries of Empire makes imperial ideology and metaphysics literally magical, giving expert technicians the ability to create superweapons and destroy worlds provided that the Hexarchate’s subjects observe the imperial calendar of rites and celebrate its triumphs/participate in rituals glorying in the torture of its ‘heretics’? It’s not exactly a subtle metaphor, but it works.

Babel does something similar, except the foundational atrocity fueling the engine of empire on a metaphysical level is, like, cultural appropriation. As an organizing metaphor, I find this less compelling.

Leaving that aside, the story makes translation literally capable of miracle-working – which of necessity requires making ‘languages’ distinct natural categories with observable metaphysical boundaries. It then sets the story in the 19th century – the era of newborn nation states and education systems and national literatures, where the concept of the national-linguistic community was the obsession of the entire European intelligentsia. Now this is not a book concerned with how the presence of magic would actually have changed history, in the slightest, but like – given how fascinated it is by translation and linguistics you’d think the whole ‘a language is a dialect with a navy’ cliché would at least get a light mention (but then the book doesn’t really treat language as any more inherent or natural than it does any other modern identity category, I suppose.)

As an Allegory

Okay, so having now spent an embarrassing number of words establishing to my own satisfaction that the book really doesn’t work at all as a period piece, let us consider; what if it wasn’t trying to be?

A great many things about the book just fit much better if you take it as a commentary on the modern university with Victorian window-dressing. Certainly the driving resentment of Oxford as an institution that sustains itself and grows rich off the exploitation of international students it considers second-class seems far more apt applied to contemporary elite western schools than 19th century ones. Likewise the racism the heroes face all seems like the kind you’d expect in a modern English town rather than a Victorian one. I’m not well-versed enough on the economics of the city to know for sure, but I would wager that the gleeful characterization of Oxford as a city that literally starts falling to ruin without the university to support it was also less accurate in the 1830s than it is today.

Read like this, everything coheres much better – but the most striking thing becomes the incredible vanity of the book. This is a morality tale where the natural revolutionary vanguard with the power to bring global hegemony to its knees through nothing but witholding their labour are..students at elite western universities (not, I must say, a class I’d consider in dire need of having their egos boosted). The emotions underlying everything make much more sense, but the plot itself becomes positively myopic.

Beyond that – if this is a story about international students at elite universities, it does a terrible job of actually portraying them. Or, properly, it only shows a certain type; just about every foreign-born student or professor we meet is some level of revolutionary, deeply opposed in principle to the empire they work within. No one is actually convinced by the carrot of a life as an exploited but exceedingly comfortable and well-compensated technician in the imperial core, and there’s not really acknowledgement at all of just how much of the apparatus of international institutions and governments in the global south – including positions with quite a bit of real power – end up being staffed by exactly that demographic who just sincerely agree with the various ideological projects employing them. Kuang makes it far too easy on herself by making just about every person of colour in the books one of the good guys, and totally undersells how convincing hegemonic ideology can be, basically.

The Necessity of Violence

This is a pet peeve and it’s a very minor thing that I really wouldn’t bring it up if that wasn’t literally part of the title. But it is, so – it’s a plot point that’s given a decent amount of attention that Griffin (Robin’s secret older brother, grizzled professional revolutionary, his introduction to anti-colonialism) is blamed for murdering one of his classmates who had the bad luck to be studying while he was sneaking in to steal some silver – a student that was quite well-loved by the faculty and her very successful classmates, who have never forgiven him. Later on, it’s revealed that this is an utter rewriting of history, and she’d been a double agent pretending to let herself be recruited into the Hermes Society who’d been luring Griffin into an ambush when he killed her and escaped.

This is – well, the most predictable not-even-a-twist imaginable, for one, but also – just rank cowardice. You titled the book ‘the necessity of violence’, the least you can do is actually own it and show that violent resistance means people (with faces, and names, not just abstractions only ever talked about in general terms) who are essentially personally innocent are going to end up collateral damage, and people are going to hold grudges about it. Have some courage in your convictions!

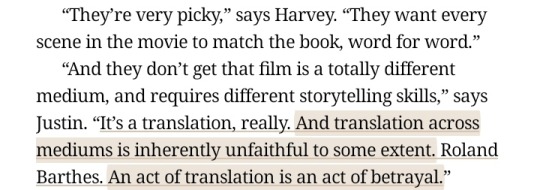

Translation

Okay, all of that said, this isn’t a book that’s wholly bad, or anything. In particular, you can really tell how much of a passion Kuang has for the art and science of translation. The depth of knowledge and eagerness to share just about overflows from the page whenever the book finds an excuse to talk about it at length, and it’s really very endearing. The philosophizing about translation was also as a rule much more interesting and nuanced then whenever the book tried to opine about high politics or revolutionary tactics.

Anyways, I really can’t recommend the book in any real way, but it did stick in my head for long enough that I’ve now written 4,000 words about it. So at the very least it’s the interesting sort of bad book, y’know?

427 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“...That they were all four of them drowning in the unfamiliar, and they saw in each other a raft, and clinging to one another was the only way to stay afloat.”

― R.F. Kuang, Babel: An Arcane History

#Babel#r. f. kuang#my art#Babel fanart#Robin Swift#Ramiz Rafi Mirza#Ramy#Victoire Desgraves#Letitia Price#Letty#one of those books that will stay with you forever#i havent been able to stop thinking about it for days#book rec#outfit and hair are probably not period accurate#sorry not sorry lol

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

textposts that remind me of the poppy war:

#the poppy war#r f kuang#r. f. kuang#the dragon republic#the burning god#fang runin#chen kitay#yin nezha#altan trengsin#chaghan suren#su daji#yin riga#jiang ziya

895 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fang Runin, The Poppy War trilogy by R. F. Kuang

#fang runin#rin#rin the poppy war#the poppy war#the dragon republic#the burning god#tpw#tdr#tbg#r. f. kuang#the poppy war fanart#tpw fanart#fanart#digital art#lami art

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

day at the flea market! 🩶

#tacitus#roman empire#roman history#babel#R. F. Kuang#Rebecca F. Kuang#flea market#flea market finds#second hand bookstore#old books#dark academia#light academia#reading#aesthetic#booklr#studyblr#studyblog#bookblog#delhi#delhigram#دہلی#old delhi

247 notes

·

View notes

Text

book cover redesigns (3/?) ⪢ babel ↳ concepts/themes: paper, light, tower of babel, oxford

image four (2) credit here

image five (5) credit here

image six (9) credit here

#babel#r. f. kuang#babeledit#bookedit#storyseekers#litedit#literatureedit#asianlitedit#litofcoloredit#book cover#usercossette#from the desk#from the bookshelf#issejj redesign series

342 notes

·

View notes

Text

r. f. kuang, quote parallels

—babel

—yellowface

321 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is no one in this fandom talking about the dragon republic first chapter???????

I mean, im sobbing with:

"she saw on the fading horizon boats sailing in from the Federation naval base on the mainland. [...]

Rows and rows of Speerlies lined up on the beach, weapons in hand.

But it was never enough. To the Federation, they must have seemed savages, using sticks to fight gods.

[...] At dawn, the Federation generals marched to the shore, boots treading indifferently over crushed bodies, advancing to slam their flag into the bloodstained sand."

.

.

.

.

.

.

I just, I can't stop thinking about how hard the Speerlies tried to defend their island, to protect themselves because they know no one else would do it for them. And it wasn't enough. An entire culture died that day. They died for a nation that never thought about them as their equal. To Nikan, the Speerlies were just beasts they can use to fight they wars.

#the poppy war#the dragon republic#r. f. kuang#fang runin#altan trengsin#Speer#tpw trilogy#im not crying you are#is this fandom allergic to hapiness?

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

I NEED IT!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“War doesn’t determine who’s right. War determines who remains.”

R. F. Kuang

The Poppy War

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fang runin header enlarged

Original artist: ig: @_olga.exe_

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay 90 pages into Babel and there was a whole bit about how 'Hindustan' was a Victorian anti-Muslim microaggression and...wasn't it a Persianate/Mughal term, or am I misremembering entirely?

#second possibility is that Rammy is supposed to be wrong here and misinformed about his own culture/what he's taking offense to#but given the rest of the book that seems unlikely#babel#r. f. kuang#sff#tht

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

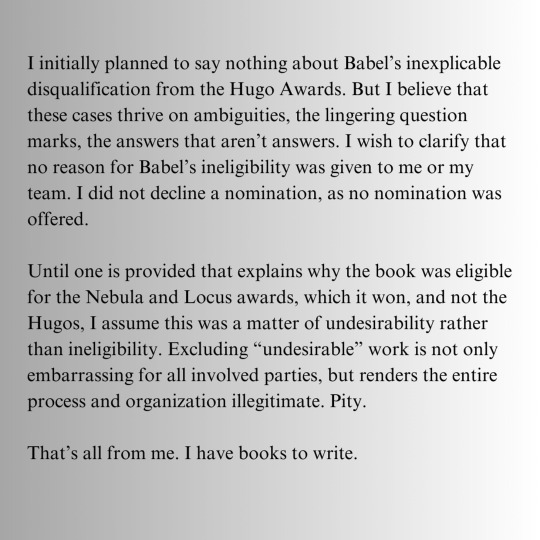

Here's R. F. Kuang's statement:

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

text posts that remind me of the poppy war pt III

#the poppy war#the burning god#the dragon republic#rf kuang#r. f. kuang#rebecca kuang#fang runin#tpw#altan trengsin#yin nezha#chen kitay

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fang Runin, The Poppy War

#i am way too obsessed#fang runin#rin#rin the poppy war#the poppy war#tpw#the dragon republic#tdr#the burning god#tbg#r. f. kuang#fantasy#books#fanart#digital art

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It all builds up, doesn't it? It doesn't just disappear. And one day, you start prodding at what you've suppressed, and it's a massive black rot and it's endless, horrifying, and you can't look away."

Babel, R. F. Kuang

173 notes

·

View notes