#Quipoem

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Happy World Poetry Day & Women’s History Month!

Cecilia Vicuña (b. 1948) is a Chilean poet and artist based in New York and Santiago, Chile. Vicuña has been creating a body of impermanent, participatory work she calls “lo precario” (the precious) since the mid-1960s.

Vicuña’s multi-dimensional works begin as a poem, an image that morphs into a film, a song, a sculpture, or a collective performance. These ephemeral, site-specific installations in nature, streets, and museums combine ritual and assemblage.

Her work calls attention to the politics of ecological destruction, cultural homogenization, and economic disparity, particularly the way in which such phenomena disenfranchise the already powerless.

The precarious : the art and poetry of Cecilia Vicuña Edited by M. Catherine de Zegher Added t. pg. title: Quipoem Hanover, N.H. : University Press of New England, c1997. HOLLIS number: 990076946700203941

#WorldPoetryDay#CeciliaVicuña#WomensHistoryMonth#Poetry#WomenArtist#Quipoem#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens) - Cecilia Vicuña

“Although better known as a poet in her adoptive North American home (she has lived in New York since the 1980s), Cecilia Vicuña has stayed true to her youthful calling as a genre-bending visual artist for more than forty years, and her site-specific projects highlight the artist’s talent for composing poems in space, for a visceral lyricism in three dimensions. Vicuña refers to these particular works as ‘quipoems’—a contraction of poem and quipu; an online dictionary defines quipu, rather reductively, as ‘a device consisting of a cord with knotted strings of various colors attached, used by the ancient Peruvians for recording events, keeping accounts, etc.’ A pre-Columbian type of writing, in other, more poetical words—product of a literary tradition that has given the world such luminaries as Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda, and Nicanor Parra. Vicuña, who was born in 1948 in Santiago de Chile, is supremely aware of the weight of Indigenous history anchoring twentieth-century Latin American culture.

“Blown up to the monumental proportions of immersive ‘soft sculpture,’ her recent Athenian quipoem consists of giant strands of untreated wool, sourced from a local Greek provider, dyed a startling crimson in honor of a syncretic religious tradition that, via the umbilical cord of menstrual symbolism, connects Andean mother goddesses with the maritime mythologies of ancient Greece.”

(source)

#art#installation#textile art#wool#red#menstruation#blood#red thread#soft sculpture#athens#myth#mythology#quipu#poem#poetry#umbilical cord

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cecilia Vicuña, Quipu Womb

The sculpture, Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens), consists of giant strands of untreated wool, sourced from a local Greek provider, dyed a startling crimson in honour of a syncretic religious tradition that, via the umbilical cord, connects Andean mother goddesses with the maritime mythologies of ancient Greece. This mythological theme is a consistent strand throughout Cecilia's work, who is much better known as an accomplished poet in the USA. Cecilia refers to her sculptural work as ‘quipoems’, meaning a cross between a poem and a quipu; ‘a device consisting of a cord with knotted string of various colours attached, used by ancient Peruvians for recording events and keeping accounts.’

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

World Lines A Quantum Supercomputer Poem (2018)

Introduction

During a site visit to the Simons Center for Geometry and Physics at Stony Brook University in October 2017, I spoke with theoretical physicist Giuseppe Mussardo about topological quantum computing, which led to my development of World Lines: A Quantum Supercomputer Poem. The poem uses a theoretical model of a topological quantum computer as its poetic form. While unique in using this model as a poetic form, which makes the poem behave like a quantum system, the poem is not so unlike other poetic forms such as sonnets and sestinas that follow a particular set of rules and pre-determined architectures to produce intended results.

How topological quantum computing works

Nature.com, “Computing with Quantum Knots,” Graham P. Collins, Scientific American 294, 56-63 (2006). doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0406-56. Credit: George Retseck.

The theoretical model of the topological quantum computer that I used for my poem is represented in a diagram, “How Topological Quantum Computing Works,” appearing in a Scientific American article (right) given to me by Mussardo. In the model, pairs of quasiparticles known as “anyons,” which exist in two-dimensional electronic fluids, are created and lined up in rows to represent qubits, the quantum bits in a quantum computer that exist as one, zero, or any quantum superposition of one and zero, where one and zero exist in n-dimensional spacetime. Each qubit in the model has two anyons that are swapped clockwise and counterclockwise in a predetermined order with adjacent anyons, creating a braid. The pairs of the adjacent anyons are measured to produce the output of the computation (Collins, 57-53).

The trajectories in time that the anyons make as they are braided are known as “world lines,” the historical paths that an object traces (Collins 58) in the three dimensions of space and the fourth dimension of time. Theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek, who coined the term, “anyon,” says that world lines are records of relative motion, a memory of an object moving (Wilczek 10). I learned from Mussardo that at each intersection of world lines resulting from the movement of the anyons, a knot can be made from the braiding and by identifying the ends of the world lines. As part of his work as a theoretical physicist, Mussardo creates quantum knots, and he sent me an image of one he developed (below) for my studies.

Quantum knots and quipu knots

To my great interest, during our discussion Mussardo mentioned that the quantum knots in topological quantum computing are thought to be related to the Incan textile known as “quipu,” connected cords and ropes with knots woven into them. The Inca, who did not have a written language, used quipus as a sophisticated system for computation and encryption. I was familiar with quipus through the Chilean and New York-based poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña, who creates iterations of quipus in her performances, art installations, and “quipoems.” Over the years, I had attended some of her performances at Naropa University and elsewhere, where she loosely threads yarns around the audience, figuratively weaving the audience into quipu knots.

Vicuña, in statements on her work, has suggested that quipus were not only used for computation but also as a language for making meaning. In addressing their destruction and banishment during and after the Spanish Conquest, she situates her artistic work with quipus as an act of rebellion “to begin again the process of speaking through the threads” (Vicuña, Quipu Astral). In her poem, “Word & Thread,” Vicuña says that a quipu “is a poem in space, a way to remember” (Ubuweb), which evokes Wilczek’s definition of a world line as a memory of an object moving. In addition to Mussardo’s image of a quantum knot and the Scientific American article with the diagram of the model of the topological quantum computer that I used for my poem, Mussardo sent me an article from Quanta Magazine by Wilczek, who directly discusses the relationship between quantum computing and quipu knots:

Computing with anyons exploits their ability to map their knotted histories into (observable) quantum-mechanical amplitudes. We move anyons around in clever ways and then access the tangled history of their motion. Topological quantum computing is, therefore, a form of computing with knots. As such, it is a modernization of quipu, the Incan technology for computation and encryption. (Wilczek 15)

Eight months after I developed World Lines at the Simons Center, I was on a site visit to the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in the Vicuña, Coquimbo, region of northern Chile to conduct research on the Dark Energy Survey for a different writing project, At the Edge of the Abyss: A Poem for the Dark Energy Survey. After my time on Cerro Tololo, I was in Santiago and saw, for the first time in person, quipus at the Museo Chileano De Arte Precolombino. A few days later, I met with Cecilia Vicuña, who was in Santiago. She said she thought that the large connected quipu (below) I had just seen was the most striking quipu left in the world.

A thought experiment in quantum poetics

If a quipu is a poem in space, and thus a substitution for ordinary language that offers a way to remember, as Vicuña has suggested, it functions like a world line, a record of the path of an object as it moves through space in time. Lines of poetry written on two-dimensional surfaces like paper also can be viewed as world lines that trace the history of letters moving across the page in time, which provide a meaning or perform a literary gesture, a computation.

Just before I created World Lines in my office at the Simons Center, I wondered: What parts of a poem could represent the knots in both quipus and topological quantum computers? Like the woven knots in quipus and the quantum knots in topological quantum computing, poetry is a spatial site—and temporal moment—of complexity in language that both compresses and lengthens the record of the path of the poetic (world) lines traveling through spacetime. Are quantum knots and quipu knots unacknowledged poetic devices where the length and breadth of the spacetime of their constituent parts gathers in a compressed location and moment? In this thought experiment in quantum poetics, my artistic theory and writing praxis, poetry, like science, can braid thoughts in the mind to create a shorthand where meaning is arrived at in a condensed form.

In his book, Physics and Philosophy (1958), Werner Heisenberg, co-founder of quantum theory, references Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe’s verse play, Faust, after articulating the problem that quantum theory does not have a language beyond mathematics to describe it. Heisenberg quotes Mephistopheles, who says that while formal education instructs that logic braces the mind “in Spanish boots so tightly laced,” and even spontaneous acts require a sequential process,

In truth the subtle web of thought Is like the weaver’s fabric wrought: One treadle moves a thousand lines, Swift dart the shuttles to and fro, Unseen the threads together flow, A thousand knots one stroke combines. (171)

Mephistopheles is arguing that nuanced, creative forms of thinking go beyond traditional logic and sequential processes. In creative thinking, the passage claims, the “subtle web of thought” happens when one gesture leads to others that flow together in unseen ways. Mephistopheles, while representing a powerful, malignant, and supernatural figure to whom Faust must sell his soul in order to gain what he desires, is also representative of knowledge and authority and, as a result, acts as a sophisticated advocate of materialism and skepticism, two qualities embedded within the scientific worldview, both then and now.

Heisenberg says that the passage from which this quote by Mephistopheles appears “contains an admirable description of the structure of language and of the narrowness of the simple logical patterns” (171). His comments speak to his interest in broadening what constitutes logic in quantum theory and the inability of ordinary language to describe what happens inside the atom. My own work examines this issue by investigating if poetic language is more capable than ordinary language of describing both subatomic and cosmological scales of matter. World Lines is one experiment testing this principle in quantum poetics.

The passage by Mephistopheles that Heisenberg quotes can be used to describe not only creative thinking but the literary genre of poetry itself. Poetry, as a complex form of creativity, can function as a literary shorthand like “one treadle” moving “a thousand lines,” where a “thousand knots one stroke combines.” One “stroke” of the “treadle,” the loom that weaves the complex thoughts referenced in Faust, can move “thousands of lines” or units of language in a poem where thousands of more “knots” or sites of complexity combine. This ability of poetry to condense language into sites of complexity through literary devices makes poetry a shorthand (Eckhoff 81), where points of complexity converge through the action of the poem.

Shorthand, which lessens the amount of space and time it takes for information to travel, evokes spatio-temporal wormholes, which connect sites in different spacetimes together, creating passage. In previous essays of mine in quantum poetics, I have speculated that a poem itself is a kind of quantum computer or spatio-temporal wormhole made of language that functions as a site of complexity through the action of writing, reading, or speaking. Readers, in this expanded definition of poetry, can be thought of as traveling poems, rather than only reading them, by following their knotted world lines.

The breakthrough

In the model of the topological quantum computer that I used as a poetic form for World Lines, each qubit has two anyons and is represented by two world lines, a green world line and a blue world line. The chalkboard in my office at the Simons Center during my second visit came with different colors of chalk, including blue chalk and green chalk. Seeing the blue and green chalk led me to think about how the world lines used in the diagram of the model were represented in blue and green ink, too, symbolic of the world itself, which is made of so much green and blue in our flora, skies, and seas. It was seeing this connection between the colors in the diagram of the quantum computer and the colors of the chalk at the chalkboard that I realized that I could use the chalkboard as a circuit board to engineer a poem by translating the model of the quantum computer to create four color-coded poetic stanzas. I proceeded to draw the model on the chalkboard and then wrote poetry over each line, which made each stanza a couplet of two qubits that correspond to the blue and green world lines in the model. I had created a world, I mused, one drawn with poetic lines that were also world lines in a theoretical topological quantum computer. What are the physics, and poetics, of this new world?

How World Lines works

My process created four pairs of poetic couplets with eight anyons total in my translation of the four-qubit topological quantum computer. A blue extended line of poetry functions as one world line of the braid, and a green extended line of poetry functions as the other world line of the braid. At the point of intersection where the braiding occurs in my poem—through the action of the quantum knots in the topological quantum computer that evoke quipus—I developed a shared word, shown in white on subsequent images of the poem, that each line of poetry needs in order to more or less syntactically make sense.

In the clockwise swapping of the world lines in my poem, the bottom anyon in the anyon pair is placed over the world line that is forged by the top anyon in the anyon pair. In the counterclockwise swapping of the world lines in the poem, the top anyon in the anyon pair is placed over the world line that is forged by the bottom anyon in the anyon pair. By connecting the world lines in the poem to perform its computation, the shared words highlight the way that a qubit can exist as a one, a zero, or any quantum superposition of one and zero, unlike a digital bit that can exist only as one or zero. The shared word at each intersection also demonstrates how a poem itself might function as a qubit; each shared word can be a word for the green world line, a word for the blue world line, and a word for both world lines in a quantum superposition of the green world line and the blue world line, suggesting that the shared word is a site of complexity in the poem like the woven knots in quipus and the quantum knots in theoretical topological quantum computers.

One outcome of the poem is that there are many possible poems inside the poem that can be thought of as existing in a quantum superposition. Since the reader can decide which world line to follow, and thus which version of the poem to read, the act of reading the poem performs a quantum measurement and, in the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory, collapses the wave function of the lines being read as that version of the poem comes into existence. Like a quantum computer or quipu, it is through the poem’s knots, the shared words, that the poem’s meaning is computed by a reader. Wright, in her article, explains further:

In her poem, Amy Catanzano replaces the weaving anyons with four poetic couplets, which crisscross over one another. Where two lines intersect, they share a word, a literary device…Catanzano used to evoke an anyon knot. These textual knots are like forks in the reader’s path. The text can be read linearly—following each line of text sequentially—or the reader can jump from one line to another when they encounter a textual knot. Different paths through the poem create unique word-braids and lead to different “calculations,” just as in a topological quantum computer. “World Lines: A Quantum Supercomputer Poem” translates the quantum theory behind a topological quantum computer in both its word choices and its visual structure….(Physics)

Tristan Greene, in his article, “Artist explains quantum theory through poetry,” discusses the different paths the reading can take in the poem:

The poem contains four poetic couplets that twist and intersect. Specific words lie at the center of more than one sentence, forcing the reader to choose which words to read next. Because of this, the poem can be read several different ways without losing its message. Think of it like Schr[ö]dinger’s poem: Until you read it, it’s several different poems at once….In quantum computing a qubit—like a computer bit, but quantum—can exist in more than one state at a time. It’s only when a qubit is observed that the universe reveals the mystery of its position (and even then, scientists disagree on whether such a measurement is a ground-truth or not). Amy Catanzano’s work invites the reader to make the ultimate decision. Is the word you’re reading part of one sentence, or another? Once you decide, as the universe does when a qubit is observed, the poem exists as you’ve chosen to read it. Perform another measurement, meaning read it again, and you have the opportunity to change the nature of the poem. (The Next Web)

Rather than attempting to describe how quantum physics works with ordinary language in ordinary forms like expository prose, which is how science is most often communicated to broad audiences, World Lines can be thought of as a quantum system by enacting principles in quantum theory. But the poem doesn’t just perform principles in physics. It also performs principles in poetic thinking. In one of many possible versions of the poem that appears below, the poem explores how a poem like itself can be woven by the mind into an indefinite quantum-quipu knot that computes information, which turns the mind contending with such a poem into both a poem and quantum computer, or, as I put it in the poem’s subtitle, “a quantum supercomputer poem.”

Conclusion and next steps

Creating World Lines allowed me to develop a site of interaction between poetry, physics, and computing through poetic methodologies, involving serious play and associative logic as well as rational thinking, involving scholarly studies of theoretical physics and computing. If the poem does indeed function as a quantum system, is a new mechanics needed that takes into account theory and experiment in both quantum physics and literary artworks such as poetry? What form would this mechanics take?

While it took me just an afternoon to draw the theoretical model of the topological quantum computer and write lines of poetry over it once I had the idea to do so, it was a six-month creative and scholarly process to get there, one that began with my site visit to the Simons Center, where I talked with Mussardo, as well as my preceding site visit to CERN, where I talked with Álvarez-Gaumé. My visits to the Simons Center not only gave me opportunities to talk with scientists in the field as well as precious time to think and write, they provided an enriched setting, one in which I felt inspired to create. My activities during my first visit, for example, included attending presentations by Mussardo, who gave a lecture on a special kind of zero, and artist Lisa Park, who talked about her installation art involving the human heartbeat. During my second visit to the Simons Center, I attended presentations by philosopher Robert Crease, who discussed the role of beauty in scientific experiments, and theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Kip Thorne, who discussed the discovery of gravitational waves.

While phase 1 of World Lines is complete, I am writing other quantum supercomputer poems in Phase 2. For phase 3, I am taking steps to work with scientists to bring World Lines into a 3D environment and art installation. In August 2019, during my second site visit to CERN, I spoke once again with Joao Pequenão, head of the MediaLab at CERN and a multimedia storyteller, about my goal. He suggested the possibilities of using gaming technology, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and virtual reality software to bring the poem into a 3D environment. I imagine an environment through which the reader moves, writing the poem as they walk.

1 note

·

View note

Text

For National Poetry Month, we want to post Cecilia Vicuña’s “lo precario” work, which she has been creating since the mid-1960s.

“The poem is not speech, not in the earth, not on paper, but in the crossing and union of the three in the place that is not.” - Cecilia Vicuña

Cecilia Vicuña (1948 -) is a poet, artist, painter, filmmaker and activist. Her work addresses pressing concerns of the modern world, including ecological destruction, human rights, and cultural homogenization. Born and raised in Santiago de Chile, she has been in exile since the early 1970s, after the military coup against elected president Salvador Allende. […]

Vicuña’s multi-dimensional works begin as a poem, an image that morphs into a film, a song, a sculpture, or a collective performance. These ephemeral, site-specific installations in nature, streets, and museums combine ritual and assemblage. She calls this impermanent, participatory work “lo precario” (the precarious): transformative acts that bridge the gap between art and life, the ancestral and the avant-garde. (from the artist’s website: http://www.ceciliavicuna.com)

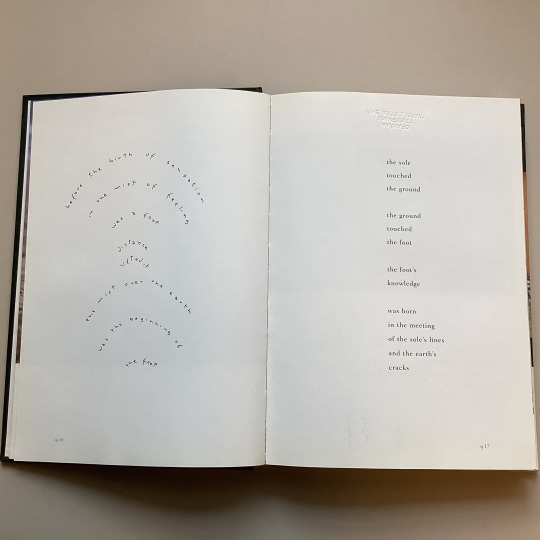

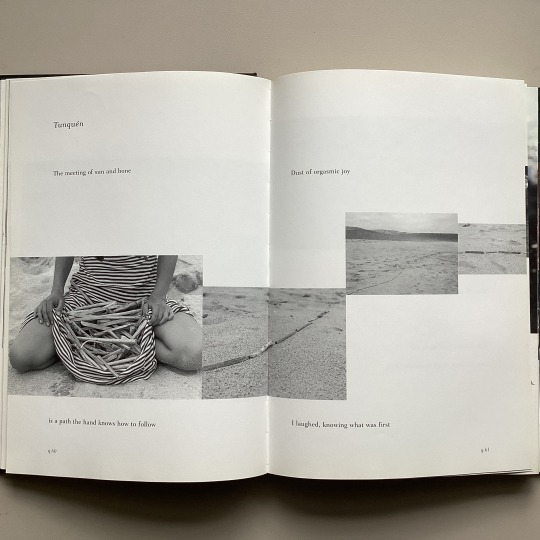

Text for Image 2:

Tunquén

The meeting of sun and bone

Is a path the hand knows how to follow

Dust of orgasmic joy

I laughed, knowing what was first

Vicuña’s exhibition “Brain Forest Quipu” at Tate Modern recently closed on April 16.

The precarious : the art and poetry of Cecilia Vicuña Edited by M. Catherine de Zegher Added t. pg. title: Quipoem Hanover, N.H. : University Press of New England, c1997. HOLLIS number: 990076946700203941

#NationalPoetryMonth#CeciliaVicuña#Womenartists#Poet#Precarious#Poetryandart#Poetry#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#harvardfineartslibrary#fineartslibrary#harvard#harvardfineartslib#harvard library

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cecilia Vicuña created this work in Bogotá, Colombia on September 26, 1979 to protest the distribution of contaminated milk. Vicuña staged a street action by tying red yarn around a glass of milk. When the yarn was pulled from a distance, the milk spilled onto the street. The following poem was written on the sidewalk in front of the home of Simon Bolivar:

A Glass of Milk

“The cow Is the continent whose milk (blood) is being spilled.

What are we doing to our life?”

The precarious : the art and poetry of Cecilia Vicuña Edited by M. Catherine de Zegher Added t. pg. title: Quipoem Hanover, N.H. : University Press of New England, c1997. HOLLIS number: 990076946700203941

#NationalPoetryMonth#CeciliaVicuña#Womenartists#Poet#Precarious#Poetryandart#Poetry#Poem#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#harvardfineartslibrary#fineartslibrary#harvard library#harvardfineartslib

7 notes

·

View notes