#Punic Wars 218 BC

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

0 notes

Photo

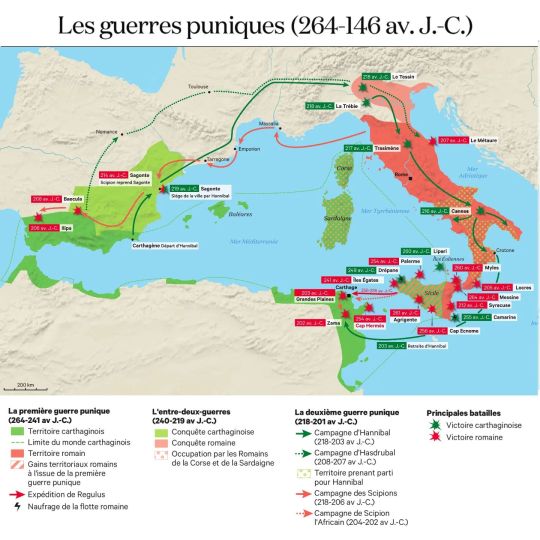

The Punic Wars, 264-146 BC

« Atlas historique mondial », Les Arènes, 2019

by cartesdhistoire

Rome and Carthage stood as the dominant powers in the western Mediterranean. Between these two influential states lay the island of Sicily. Situated at the crossroads of Europe and Africa, and bridging the eastern and western Mediterranean basins, Sicily held immense strategic importance. Rich in wheat and boasting a heritage of prosperity bestowed by both the Carthaginians in the west (in Palermo) and the Greeks in the east (in Syracuse), the island flourished. The Carthaginians established their capital at Lilybaea (modern-day Marsala) and maintained a major naval base at Drepane (modern-day Trapani).

In 264 BC, the onset of the First Punic War marked the first engagement of Roman legionnaires outside of Italy. While battles were fought in open fields, guerrilla warfare, and sieges, the defining feature of this conflict lay at sea. The pivotal Battle of the Aegate Islands in 241 BC resulted in the defeat of the Carthaginians, triggering another conflict, the far more perilous Mercenary War, on African soil. Fueled by grievances over unpaid wages, mercenaries and local allies revolted against Carthage, plunging the region into turmoil until order was restored by Hamilcar in 238 BC. A peace treaty with Rome was signed on March 10th.

The Second Punic War, commencing in 218 BC, was marked by an intriguing characteristic: personalization. The conflict became synonymous with the personalities of Scipio, later known as "the first African," and Hannibal, one of history's greatest military commanders. Hannibal's audacious invasion of Italy, driven by a desire to avenge Carthage's honor, catalyzed the war's escalation.

The war culminated in the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, leading to the signing of a final treaty in 201 BC. From this point forward, Rome emerged unchallenged in the Mediterranean. However, it wasn't until 197 BC that the Senate formally established the two provinces of Spain.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Future Is Noir

Scenography for the darkness with the uncertain future. Architecture of fear in the cinema of 1920s.

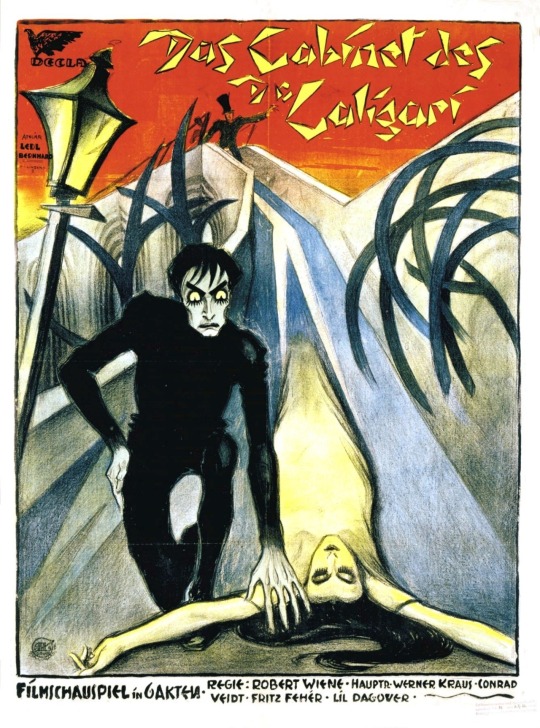

Considered the quintessential work of German expressionist cinema, the Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) by Robert Wiene tells the story of an insane hypnotist who uses a brainwashed somnambulist to commit murders.

youtube

The film thematizes brutal and irrational authority. Caligari can be representing the German war government, with the symbolic of the common man conditioned to kill. The film include the destabilized contrast between the subjective perception of reality, and the duality of human nature.

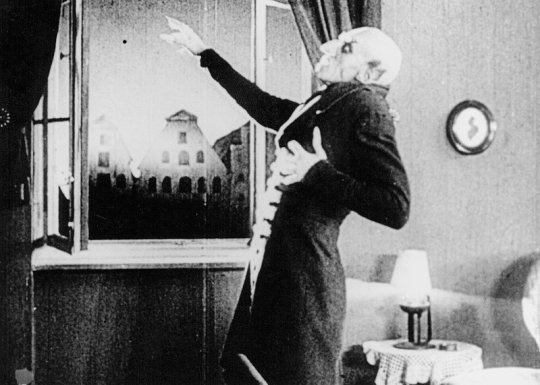

An unofficial adaptation of Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula in film is the German version of Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) by F. W. Murnau. Nosferatu is an archaic Romanian word Nesuferitu` meaning the offensive or the insufferable one. The movie is actually about the First World War and the plague is a metaphor for the mass death and destruction of the war.

youtube

Nosferatu was banned in Sweden due to excessive horror until 1972. All known prints and negatives were destroyed under the terms of settlement of a lawsuit by Bram Stoker's widow.

Berlin – Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (1927) is an experimental documentary by Walther Ruttmann. It begins with a drive of a high-speed train pulled by a steam locomotive through meadows, arbor and residential areas into the city and thus delimits the surrounding area from the big city.

The train arrives at Anhalter Bahnhof near the city center, where streets empty in the morning are filling up with people on their way to work. The rhythm of the city is getting faster and faster. With the 12 o'clock bell strike, the speed collapses. After lunch break and food intake, however, it begins to accelerate again in the afternoon.

youtube

Cabiria (1914), an Italian epic silent film by Giovanni Pastrone, was shot in Turin. The film is set in ancient Sicily, Carthage, and Cirta during the period of the Second Punic War (218–202 BC).

It follows a melodramatic main plot about an abducted little girl, Cabiria, and features an eruption of Mount Etna, heinous religious rituals in Carthage, the alpine trek of Hannibal, Archimedes' defeat of the Roman fleet at the Siege of Syracuse and Scipio maneuvering in North Africa.

youtube

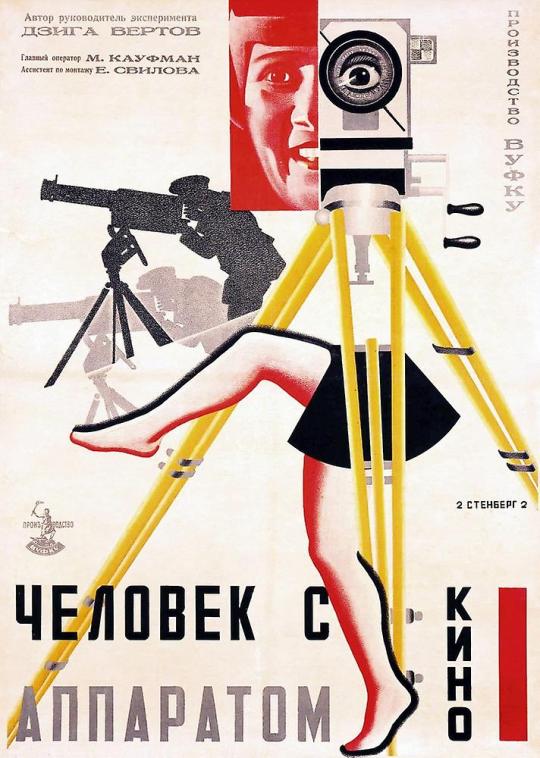

One the most influential films in cinema history, Dziga Vertov's exhilarating ode to Bolshevik Russia the Man with a Movie Camera (1929). It is a visual argument for the place of the documentary filmmaker as a worker, educator, and eyewitness in a proletariat society. The film is an impressionistic view of urban daily life, seen from a purely cinematic perspective.

youtube

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

good news everyone ! i gave up on doing homework and im looking for insects named after ancient romans and other ancient historical figures related to roman history. turns out theres a species of weevil named after hannibal!

and its glorious wikipedia description: "A species from Tunisia, named after the daring Punic general Hannibal. Hannibal was best known for his spectacular, but also costly campaign with 40 war elephants in 218 BC from Spain, France across the Alps to Italy. In 202 BC, the Roman Empire was finally victorious over Hannibal at Carthage (Carthage, today part of the Tunisian capital Tunis). It was only with the victory over Hannibal that Rome gained supremacy in the western Mediterranean. The city of Carthage was finally razed to the ground in the Third Punic War (146 BC), the inhabitants expelled or taken into slavery by Rome. Let us hope that the last Ceratonia forests on Jebel Zaghouan, and with them the new species Onyxacalles hannibali, will not meet a similar fate in the progressive destruction of the last intact biotopes in central Tunisia!""

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam.*

- Cato the Elder

Furthermore, I consider that Carthage must be destroyed.*

At the turn of the 2nd century BCE, the Second Punic War between Carthage and Rome had ended. Rome was eventually victorious, but had suffered some significant and bad defeats. The peace treaty was even tougher for Carthage – it stripped them of many of their territories, their wealth, and restricted their actions. Fast forward 50 years later, there was another conflict between Carthage and Rome – this time in a Punic-turned-Roman-city called Massinissa. Marcus Porcius Cato, a famous Roman orator and senator, was sent to Massinissa to investigate. He had fought in the Second Punic War in his 20s. Cato was surprised to see that, since the end of the Second Punic War, Carthage had become a thriving and wealthy city again.

When Cato came to back to Rome, he called for the war against Carthage – a war to stop them once and for all. He ended his speech with the phrase: Carthago delenda est. (Carthage must be destroyed.)

Plutarch tells us that Cato's call ended his every speech in the Roman Senate, 'on any matter whatsoever', from 153 BC to his death aged 85 in 149. Scipio Nasica - son-in- law of Scipio Africanus, conqueror of Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218-202 BC) - would always reply: 'Carthage should be allowed to exist'. But such challengers were silenced. Rome decided on war 'long before' it launched the Third Punic War just prior to Cato's death. One of his last speeches in the Senate, before a Carthaginian delegation in 149, was critical:

“Who are the ones who have often violated the treaty? . . . Who are the ones who have waged war most cruelly? ... Who are the ones who have ravaged Italy? The Carthaginians. Who are the ones who demand forgiveness? The Carthaginians. See then how it would suit them to get what they want.”

The Carthaginian delegates were accorded no right of reply. In 146 BC, nearly 8 years after Cato ventured back to Carthage and saw its wealth, would Carthage attack Massinissa and give Rome a reason to star the Third (and final) Punic War.

Rome soon began a three-year siege of the world's wealthiest city. Of a population of 2-400,000 at least 150,000 Carthaginians perished. Appian described one battle in which '70,000, including non-combatants' were killed, probably an exaggeration. But Polybius, who participated in the campaign, confirmed that 'the number of deaths was incredibly large' and the Carthaginians 'utterly exterminated'. In 146, Roman legions under Scipio Aemilianus, Cato's ally and brother-in-law of his son, razed the city, and dispersed into slavery the 55,000 survivors, including 25,000 women. Plutarch concluded: 'The annihilation of Carthage . . . was primarily due to the advice and counsel of Cato'.

It was not a war of racial extermination. The Romans did not massacre the survivors, nor the adult males. Nor was Carthage victim of a Kulturkrieg. Though the Romans also destroyed five allied African cities of Punic culture, they spared seven other towns which had defected to them. Yet, the Carthaginians had complied in 149 with Rome's demand to surrender their 200,000 individual weapons and 200 catapults.

Little did they know that the Senate had already secretly decided to destroy Carthage for good, once the war is over. The surprising new demand that they abandon their city meant abandoning its sanctuaries and religious cults to abandon their city, meant abandoning its sanctuaries and religious cults. And in this Carthaginians resisted in vain. Rome opted for the destruction of the nation.

Carthago delenda est has become somewhat of a rallying call against a common enemy - a call for total war.

None of this was lost on Churchill as he addressed British troops in the old Roman amphitheater at Carthage, Tunisia. Nothing short of the total destruction of Nazi Germany for the sake of civilisation and humanity were at stake. The Nazis were an existential threat. Like Cato, Churchill knew the power of oratory to move men into action.

Photo: Churchill leaves the old Roman amphitheatre with Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson after addressing British troops, 1 June 1943.

#cato#roman#latin#classical#quote#rome#carthage#punic wars#war#total war#churchill#winston churchill#british army#second world war#tunisia

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

all you morons laughing at show cersei for the elephant thing as if that didn’t work out great for hannibal of carthage during the second punic war in 218 BC.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apart from the sanitation, the medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, a fresh water system, and public health, what have the Romans ever done for us?

Life of Brian (which incidentally was filmed in Tunisia)!

What is now Tunisia has been conquered and/or settled by Berbers, Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Jews, Arab Muslims (who conquered what became Ifriqiya from the Byzantines and fought off Byzantine and Berber counterattacks between 670 and 705 AD, thus ensuring Tunisia became mostly Arab and Islamic, which it still is), Normans, Italians, Maltese, Spaniards, Ottomans, French, but this post is mostly about the Romans.

This is mainly a post about the ancient history of what is now Tunisia; you can see here for the rest of my series for modern times.

For much of antiquity, what is now Tunisia was part of Carthage, a mostly sea-borne empire founded in the 9th century by the Phoenicians, who had come from the Near East and were a Semitic people related to Arabs and Jews (both of whom live in Tunisia today), conquered and assimilated with the Berbers (who still make up much of Tunisian DNA, though the language and culture is less valued than in Morocco), the Carthaginians believing in racial harmony as long as everyone accepted their rule.

The upstart Roman Republic, later Empire, having defeated the Greek ruler Pyrrhus in the Pyrrhic Wars of 285-270 BC, came into conflict with the Carthaginians, who also fought the Berber kingdom of Numidia.

At first the Romans were bested by the Carthaginian war elephants and their army of not just North Africans but other mercenaries and subjects including Celts, Spaniards, Greeks, and sub-Saharan Africans, in the First Punic War of 264-241 BC; nearby was fought the Battle of Tunis in 255 BC, which Carthage won.

The war ended, though, with a Roman victory on battlegrounds including what is now Tunisia as well as Sardinia and Sicily; then as now, a frontier of Europe and North Africa through which migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, often made unwelcome in modern Tunisia, try to pass.

Despite losing the First Punic war, Carthage endured under the leadership of Hamilcar Barca, who reclaimed much of Carthage’s power in the Mercenary War of 237 BC. Then in the Second Punic War of 218-201 BC, the feared Carthaginian general Hannibal (247BC-183-81 BC), Hamilcar's son, counterattacked.

Hannibal marched on Europe with his feared elephants, crossing the Alps in 218 BC, and after the Carthaginian victory at Cannae in 216 BC 'Hannibal ad portes' was used as a threat by Roman mothers; his status in Roman minds was a bit like that of the Russian and American empires in the minds of the other today.

Hannibal did not march on Rome; we will never know whether doing so would have led to a great victory or hastened Carthage's demise, but Carthage did end up losing this war thanks in part to the efforts of the great general Scipio Africanus (236 BC-183 BC) , and Hannibal went into exile in 195 BC, though this was not yet the end of Carthage.

Carthage fell to the Romans after Roman victory in the Third Punic War of 149-146 BC; it was destroyed but much later rebuilt by Caesar Augustus, who founded the Roman Empire from the republic and reigned from 31 BC to 14 AD, and is now located near the modern capital of Tunis. The Roman province of Africa bordered on Mauretania, which contains modern Morocco (please see here for my series on Morocco, which I went to last year and which has much in common with Tunisia).

The ampitheatre at what is now El Djem was part of a large Roman city, Thysdrus; made of locally quarried stone with 192 arches, it was built in 238 AD by African consul Gordium and held 35,000 fans, who enjoyed chariot races and gladiator fights. Gordian became emperor in the same year but lasted only 22 days before being overthrown and killed! Nevertheless, he will not be forgotten as long as this building stands.

(This building is a symbol of Rome’s huge empire, which sprawled as far as my own country, and I went to the Roman city of Virconium, very near where I live, a few months ago; it’s odd thinking one rule applied from there to here).

The tragedy that happened here was much later; the Revolutions of Tunis in 1695 AD which was a feud/civil war between two brothers. Loyalists of Ali Bey al Muradi barricaded themselves in here and were bombed by supporters of his brother Mohamed Bey al Muradi as part of a struggle that ended only on the seizure of power by Al-Husayn I in 1705, who founded the Husainid Dynasty that was enthroned until Tunisia became a republic in 1957 (later posts will deal with this).

These bombings, without which the ampitheatre was encircled, were a struggle within the Ottoman empire; the Ottomans ruled Tunisia from 1574 to 1881, and you can see here for the rest of my series for what they did and what happened next.

Since 1979 it has been a UNESCO World Heritage site and there is a classical music festival held here every year; sadly I didn’t catch it, but you can if you go this summer.

Legend has it that when Roman general Scipio Aemilianus ( the adopted grandson of Scipio Africanus) saw the destruction of Carthage he wept, and when asked why, answered “A glorious moment, Polybius; but I have a dread foreboding that some day the same doom will be pronounced on my own country”.

This did indeed happen when the Vandals brought down the Roman Empire in 455 AD, but while they and all later empires came and went, Tunisia has remained itself.

0 notes

Text

General Hannibal Barca (247 BC - between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who is widely considered one of the greatest military commanders in history. His father, Hamilcar Barca, was a leading Carthaginian commander during the First Punic War (264–241 BC). His younger brothers were Mago and Hasdrubal, and he was brother-in-law to Hasdrubal the Fair; all commanded Carthaginian armies.

He lived during a period of great tension in the western Mediterranean Basin, triggered by the emergence of the Roman Republic as a great power after it had established its supremacy over Italy. Rome had won the First Punic War, and revanchism prevailed in Carthage, symbolized by the alleged pledge that Hannibal made to his father never to be a friend of Rome. The Second Punic War broke out on November 15, 218 after his attack on Saguntum, an ally of Rome in Hispania. He made his famous military exploit of carrying the war to Italy by crossing the Alps with his African elephants. In his first few years in Italy, he won a succession of dramatic victories at the Trebia, Lake Trasimene, and Cannae. He distinguished himself for his ability to determine his and his opponent’s respective strengths and weaknesses, and to plan battles accordingly. His well-planned strategies allowed him to conquer several Italian cities allied with Rome. He occupied most of southern Italy for 15 years, but could not win a decisive victory, as the Romans led by Fabius Maximus avoided confrontation with him, instead of waging a war of attrition. A counter-invasion of North Africa led by Scipio Africanus forced him to return to Carthage. Scipio had studied his tactics and devised some of his own, and he defeated Rome’s nemesis at the Battle of Zama, having driven his brother Hasdrubal out of the Iberian Peninsula. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

The History of Roman Tidal Baths in Malta

Malta, an archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea, is renowned for its rich history, stunning architecture, and diverse cultural influences. Among its many treasures are the remnants of Roman tidal baths, which offer a fascinating glimpse into the daily life of the ancient Romans who once inhabited the island.

The Roman Influence on Malta

The Romans first arrived in Malta in 218 BC during the Second Punic War. They recognized the strategic importance of the islands and established their presence, which significantly influenced the local culture, architecture, and infrastructure. Roman rule introduced various amenities, including public baths, which played a central role in social life.

The Structure of Roman Tidal Baths

Roman tidal baths, or "thermae," were elaborate complexes that utilized the natural flow of seawater. These baths typically included several sections, such as hot and cold pools, steam rooms, and areas for relaxation and socialization. The innovative design allowed for the natural temperature regulation of water, with tidal forces contributing to the baths' efficiency.

In Malta, one of the most notable examples of these baths is found in the ancient city of Melite, present-day Mdina. Archaeological excavations have revealed the remnants of these baths, showcasing intricate mosaics, stonework, and the advanced engineering techniques employed by the Romans.

Cultural Significance

The baths were more than just places for bathing; they were social hubs where people gathered to discuss politics, conduct business, or simply relax. This communal aspect of bathing was integral to Roman culture, reflecting their values of social interaction and public life.

In Malta, the Roman tidal baths served not only the local population but also visitors and traders traveling through the Mediterranean. They highlighted the island's role as a key stopover for maritime trade and cultural exchange.

Archaeological Discoveries

Recent archaeological efforts have shed light on the extent of the Roman baths in Malta. Excavations have unearthed various artifacts, including pottery, coins, and tools, providing insights into the daily lives of the Romans on the island. These findings have enhanced our understanding of Malta's historical significance during the Roman period.

Preservation and Tourism

Today, the remnants of the Roman tidal baths are preserved as part of Malta's rich heritage. They attract tourists and history enthusiasts eager to explore the ancient civilization's influence on the islands. Efforts to maintain and promote these historical sites are essential for educating future generations about Malta's vibrant past.

Conclusion

The Roman tidal baths of Malta are a testament to the island's historical significance and its connection to the broader Roman Empire. They reflect the architectural ingenuity, social practices, and cultural exchanges that characterized Roman life. As we continue to uncover and preserve these ancient treasures, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complex history of Malta and its enduring legacy in the Mediterranean world.

Exploring the Roman tidal baths is not just a journey into the past; it is an invitation to understand the enduring influence of ancient civilizations on our present-day lives. Whether you're a history buff or a curious traveler, the baths are a must-see when visiting this enchanting island.

0 notes

Text

The Continence of Scipio 1

The Continence of Scipio, sometimes called the Clemency of Scipio, is a wonderful story reflecting a distinctly Roman view of the virtues. The oldest surviving account is in Livy, and it eventually became a common theme in art, literature, and music during the Renaissance.

Publius Cornelius Scipio, later known as Scipio Africanus, commanded a Roman army in Spain during the Second Punic War (218-201 BC). The Roman soldiers captured a beautiful woman, who was engaged to the Celtiberian prince, Allucius, an ally of the Carthaginians.

She was presented to Scipio, perhaps because the soldiers knew of his reputation as a playboy. Instead of forcing himself upon her, making her a slave, or selling her for a hefty ransom, Scipio instead saw the opportunity to exercise his power with character.

If only more leaders could think and act in this way! I find great inspiration in the many paintings of this noble scene.

—3/2003

* * * * *

Soon afterwards an adult maiden who had been captured was brought to Scipio by the soldiers, a girl of such exceptional beauty that she attracted the eyes of all wherever she moved. On enquiring as to her country and parentage, Scipio learnt, amongst other things, that she had been betrothed to a young Celtiberian noble named Allucius.

He at once sent for her parents and also for her betrothed, who, he learnt, was pining to death through love of her. On the arrival of the latter Scipio addressed him in more studied terms than a father would use.

"A young man myself," he said, "I am addressing myself to a young man, so we may lay aside all reserve. When your betrothed had been taken by my soldiers and brought to me, I was informed that she was very dear to you, and her beauty made me believe it. Were I allowed the pleasures suitable to my age, especially those of chaste and lawful love, instead of being preoccupied with affairs of state, I should wish that I might be forgiven for loving too ardently.

"Now I have the power to indulge another's love, namely yours. Your betrothed has received the same respectful treatment since she has been in my power that she would have met with from her own parents. She has been reserved for you, in order that she might be given to you as a gift inviolate and worthy of us both.

"In return for that boon I stipulate for this one reward—that you will be a friend to Rome. If you believe me to be an upright and honorable man such as the nations here found my father and uncle to be, you may rest assured that there are many in Rome like us, and you may be perfectly certain that nowhere in the world can any people be named whom you would less wish to have as a foe to you and yours, or whom you would more desire as a friend."

The young man was overcome with bashfulness and joy. He grasped Scipio's hand, and besought all the gods to recompense him, for it was quite impossible for him to make any return adequate to his own feelings, or the kindness Scipio had shown him.

Then the girl's parents and relatives were called. They had brought a large amount of gold for her ransom, and when she was freely given back to them, they begged Scipio to accept it as a gift from them; his doing so, they declared, would evoke as much gratitude as the restoration of the maiden unhurt.

As they urged their request with great importunity, Scipio said that he would accept it, and ordered it to be laid at his feet. Calling Allucius, he said to him: "In addition to the dowry which you are to receive from your future father-in-law you will now receive this from me as a wedding present." He then told him to take up the gold and keep it.

Delighted with the present and the honorable treatment he had received, the young man resumed home, and filled the ears of his countrymen with justly-earned praises of Scipio. A young man had come among them, he declared, in all ways like the gods, winning his way everywhere by his generosity and goodness of heart as much as by the might of his arms. He began to enlist a body of his retainers, and in a few days returned to Scipio with a picked force of 1,400 mounted men.

—from Livy, The History of Rome, 26.50

IMAGE: Giovanni Bellini, The Continence of Scipio (c. 1508)

1 note

·

View note

Text

March 2024 Reading

I try to read one Italian novel, and one history/political theory book per month. I started early on the Italian novel thinking I'd be finished with it after March 1st, but actually finished it before. So technically I read it in February, but I'm gonna count it as my March Italian novel, so it gets included here.

Busy month with 11 books read.

Seta- Alessandro Baricco (1996) An Italian novel about a Frenchman who travels to Japan. Seta means silk, and the novel is about a Frenchman who travels to find silkworms to bring back to his hometown. There is a pestilence that affects Europe and Africa, so he travels to Japan to buy silkworms there. Japan at the time of the novel (1861) was a closed society, so foreigners weren't really allowed to legally do business. While he is there, he meets with a local warlord who sells him the silkworms. But the Frenchman notices the warlord's concubine and becomes obsessed with her. Before he leaves, she gives him a note in Japanese, which he can't read. When he gets home, he takes it to the one Japanese person he could find in France, and she reads the note for him: Come back or I'll die. He returns and they spend one night together. Back home, he is loving to his wife, but she seems to notice something. He goes back the next year but Japan is in a civil war and the warlord seems to have discovered the incident. He tells the Frenchman never to come back. The Frenchman returns home. A few years later, he receives some pages written in Japanese. He takes it to the Japanese lady in France to have her read it, and it is a love letter describing his night with the warlord's girl, but telling him to forget about her. A few years later his wife dies and he lives quietly for a bit, but then he goes to look for the Japanese lady in France again. When he finds her, he asks if she herself had written the note. She confesses that she did not: it was his wife who had written it, and asked her to translate it into Japanese.

The War with Hannibal: Livy (27-9BC)

This Penguin Classics compilation of Livy's writings covers books 21-30, dealing with Rome's conflict with Hannibal. The details of the second Punic war were fascinating to me. In the previous books of Livy, I was not so interested in the battle details, but this was different. I also found the negotiation speeches interesting. The time period covered was 218 BC to 201 BC.

The Dark Heart of Italy- Tobias Jones (2003)

Really interesting book for someone who loves Italy, but has also been frustrated by the country.

He discusses the deep hierarchy that infects much of Italian life below the surface of vivacity. The Italians love of rhetoric over truth, and the impossibility of getting to anything resembling truth in a highly politicized and polarized governmental system.

But he also recounts the many refinements and sophistications that mark the lives of Italians. While the title is the "dark heart" of Italy, the book isn't really about how Italy is all dark. It's just that the darkness is part of the equation.

Villette- Charlotte Brontë (1853)

This is the last novel Charlotte Brontë wrote. The story is of Lucy Snowe, a young English girl who makes her way across to the fictional village of Villette in France (Belgium), where she finds work as a schoolteacher. The main claim to fame the novel has is it's deeper exploration of the character's psychology, rather than the plot itself.

I could have done with less French in the book, which Brontë sprinkles, untranslated, pretty liberally throughout the book. But while I don’t know French, I've had enough Italian and Spanish to not be totally lost.... assuming at least that my guesses were more or less correct.

The book contains a quote by Lucy Snowe that I very much identified with: "The beginning of all efforts has indeed with me been marked by a preternatural imbecility."

In all the plumbing of Lucy's inner thoughts, I feel like I might be able to recognize them in someone else I know, but that's of course conjecture on some level. It did make the novel more interesting to me though.

The Red and the Black- Stendahl (1830)

The reason for the name of the title is apparently unknown. The story is of a peasant carpenter's son, Julien Sorel, in 1830's France, who manages to rise through various opportunities to a place among the most powerful men in the country. Along the way he picks up the hypocrisy of the day.

One of the constant discussions in the book is how conversation, and really even personality, in the upper class Parisian circles were utterly devoid of any substance. The basic reason is that if one were to show anything more than the most banal cliches, it would open that person up to ridicule- the one thing that must be avoided at all times. This resulted in vapid pointless speech, wrapped in vapid pointless 'wit' and the ever-important "courtesy" and decorum that was considered essential.

Julien, occasionally steps outside this mold though and attracts the attention of some notable ladies, including the daughter of the duke to whom he acts as a personal assistant. She becomes pregnant and Julien's once brilliant career totters. But he then returns home and commits an inexplicable crime, which gets him sentenced to death.

The Turn of the Screw- Henry James (1898)

A short kind of ghost/horror story. Not one of my favorites.

The Prince and the Pauper- Mark Twain (1881)

Well-known story about a beggar boy who, about to be beaten by a guard for merely wanted to glimpse the royalty, is taken in by the young prince. The boys swap clothes and discover they look alike. At some point the prince runs outside, but being dressed as the beggar, isn't recognized as the prince. He is then mistreated. The beggar on the other hand is assumed to be the actual prince.

The morality tale show that being the other isn't always what one imagined. The prince learns a little about how difficult life can be for those not born into privilege, while the beggar learns that being a prince isn't all about getting one's way.

Twain wrote this amusing bit about a conversation between two farm girls who come upon the prince after he fell asleep in their barn:

Who art thou, boy? I am the king, was the grave answer. The king? What king? The king of England! The children looked at each other, then him, then at each other again. Then one said, Didst hear him Margery? He saith he is the king. Can that be true? How can it be else but true, Prissy? Would he say a lie? For look you Prissy, an' it were not true, it would be a lie. It surely would be. Now think on't. For all things that be not true be lies; thou canst make nought else of it. It was a good tight argument, without a leak in it anywhere;

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court- Mark Twain (1889)

This is a funny book, which one might expect when the author is Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens). It's essentially a satire of medieval monarchy and chivalrous notions, that gives the author plenty of opportunities to contrast modern American ideas of democracy against the feudal times where the story takes place. The basic story is that a young mechanical engineer from 1880's Connecticut gets knocked unconscious and is somehow transported to sixth-century Britain at the time of King Arthur's court.

He uses some of his more modern knowledge to impress the people, then travels around confronting various social paradigms of the day.

The Island of Dr. Moreau- H.G. Wells (1896)

Early sci-fi work of the 'mad-scientist' sub-genre. Dr Moreau builds a lab on an otherwise deserted south pacific island so he can conduct his experiments mixing humans with animals. The half human/half beasts at some point rise up against him and everything goes about as badly as one might expect from such experiments, even if they were possible.

Pere Goriot- Honore de Balzac (1835)

Father Goriot, or old Goriot, is an old father obsessed with his two daughters. He lives vicariously through them, even though they have rejected him, and lives in a state of financial ruin hoping only to see them do well, even if from afar. him to financial ruin

The story also includes two other characters who live at the boarding house where Goriot stays: Eugene de Rastignac, a student from outside Paris, and an older prison escapee, Vautrin.

The Invisible Man- H.G. Wells (1897)

Griffin, a young scientist, discovers a way to make himself invisible. He imagined the positive usages for this, but didn't foresee the negatives. Once invisible, however, he finds himself hunted by society. He descends ever deeper into a me-versus-everyone attitude until he reasons the only way he can protect himself is by instituting a reign of terror over the local people.

In his attempt to do so, he is captured and killed, and as he dies, visibility returns to him so the people can see Griffin.

0 notes

Text

Specialist Practice

Research

Spanish language

The history of the world, of Europe, and course, especially the Iberian Peninsula, are all directly related to the development of the Spanish language. Although it is simple to assume that current languages are unchanging characteristics of nations and areas, they continue to change and are fascinatingly shaped by their histories.

From the Roman invasion of Hispania (today's Spain and Portugal) to the use of contemporary Spanish over the world, the history of the Spanish language spans at least 22 centuries.

Where did Spanish originate

Spanish has its roots in the Iberian Peninsula and evolved from spoken Latin, commonly referred to as Vulgar Latin. During the Reconquista period - a time when Spain was reclaimed by Christians after Muslim occupation - Castilian Spanish emerged as the dominant dialect of Spanish. Thereafter, this variety spread across regions worldwide.

The origin of the Spanish language:

The Roman Republic conquered the Iberian Peninsula and carried the Latin language with them beginning in 218 BC with the second Punic War against Rome's Mediterranean foe Carthage.

In a precursor to Spain's subsequent operations in Latin America, the Romans constructed roads and settlements, farmed olive oil and wine, and mined minerals, including significant amounts of silver.

Spain after the Roman Empire:

the Roman Empire declined during the first half of the AD millennium, its grip on Hispania loosened and Germanic tribes seized this opportunity to assert their power. Consequently, in the 5th century, these invaders replaced Rome's influence by founding the Visigothic Kingdom. Although they upheld Christianity which had already taken root towards the end of Rome's rule; nevertheless, their cultural contributions left only a minor imprint on Spain's language and culture.

The Umayyad Caliphate initiated the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula from northern Africa in 711 AD. Within a brief span, Muslims had taken over Portugal and Spain entirely. Nevertheless, their hold on various regions differed significantly with durations ranging between fewer than thirty years in Galicia located to the north and nearly seven hundred eighty-one years around Granada situated towards southern parts of Spain.

Amidst this era, the Arabic dialect fused with the local Latin vernacular that was commonly used in Spain specifically within its southern regions.

The Reconquest:

The Reconquista refers to the almost 800-year-long effort to retake Spain from Muslim domination. From northern Spain southward, many Christian Kingdoms developed their spheres of influence.

The Reconquista was finally completed in 1491 when Granada, the last bastion of Muslim control in Spain, submitted to the forces of Castile and Aragon.

Who invented the Spanish language?

The Spanish language, which developed from spoken Latin, was created by Christian Kingdoms as they retook control of the Iberian Peninsula. Old Castilian Spanish became the official tongue of the unified Spain, and the Kingdom of Castile emerged as the dominant force.

Languages in the Iberian Peninsula:

The diverse kingdoms engaged in the Reconquista communicated through several spoken Latin dialects, which evolved from the formal Latin adopted by the Roman Empire. The contemporary tongues and idioms present in Iberia today like Spanish (Castilian), Portuguese, Catalan and Galician can be linked back to these rival domains.

Over time, both kingdoms progressively repossessed control over the Iberian Peninsula simultaneously from north to south. Thus, a noticeable east-west arrangement is displayed in the languages spoken throughout the territory; like layers of cake stacked on top of each other.

From Galicia southwards on the Iberian Peninsula, a small strip of land is where Portuguese is spoken. Since Old Portuguese has close ties to Galician-Portuguese or Medieval Galician, it's no wonder they're often used interchangeably.

Likewise, on the eastern coast of Spain, Catalan is predominantly spoken whereas Leonese, Castilian and Aragonese dominate the heartland of the Peninsula.

Where did the Spanish language come from

During the Reconquista, Modern Spanish evolved from Old Castilian Spanish and became the dominant language among various Latin dialects spoken in northern Spain. As Christian kingdoms expanded southwards, so too did this linguistic influence.

When was Spanish invented?:

In the 13th century, Toledo was conquered by the Kingdom of Castile which led to the establishment of a standardized written form for Castilian Spanish. This significant historical event marked Spanish as an independent language.

Previously known as a cultural hub, Toledo evolved into an epicentre for translating Arabic and Hebrew manuscripts into Castilian Spanish and Latin. This transformation led to the heightened significance of Castilian Spanish in transmitting antiquated wisdom. The translation efforts carried out in Toledo played a pivotal role in preserving ancient Greek masterpieces that we have access to this day.

After the formation of the unified Spanish Kingdom, Castilian Spanish continued to develop into Early Modern Spanish during Spain's Golden Age. This era produced renowned works of literature such as Miguel

How old is the Spanish language?

Castilian Spanish emerged during the 13th century, making it around 700 years old today - roughly equivalent to the duration of Muslim governance in southern Spain.

The spread of the Spanish language?

With the Reconquista's eventual victory, Spain's rulers turned their attention to the world outside the Iberian Peninsula and funded intrepid sea trips around the globe. The Spanish language was disseminated throughout the Americas, Africa, Oceania, and Asia by Spanish conquistadors, missionaries, and explorers.

The Conquista in Latin America

After the final Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula was destroyed in 1491, Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas and started the Conquista or conquest of Latin America.

Similar to how Latin was introduced to the Iberian Peninsula 17 centuries earlier, Spanish conquistadors and missionaries spread the Spanish language over North, Central, and South America as well as the Caribbean.

Early Modern Spanish spread throughout Spain's colonies in the new globe since this occurred mostly in the 16th and 17th centuries.

How did the Spanish language change over time?

After evolving from spoken Latin, Spanish has undergone a 700-year journey of change to arrive at its present form. Present-day Spanish reflects significant Arabic influence and distinguishes itself through differing grammar and vocabulary across various regions where it is spoken.

Differences Spanish dialects

The Spanish language of the Early Modern period was brought to Latin American colonies during the 16th and 17th centuries. However, its evolution into Modern Spanish varied in each country over time.

The Royal Spanish Academy (Real Academia Española) was established by King Philipp V of Spain in 1713 to maintain the coherence of the language. The Association of Academies, comprised of 22 academies from other nations that promote the use and study of the Spanish language worldwide, includes this academy as an active member.

Despite efforts made by these institutes to ensure uniformity and track the development of Spanish, there are still numerous variations present across different countries and regions. These linguistic differences contribute greatly to the allure of the Spanish language.

0 notes

Photo

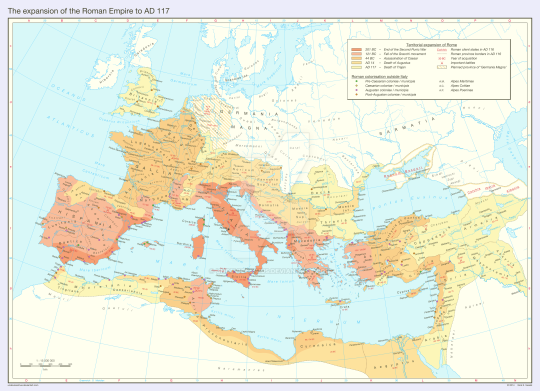

The expansion of the Roman Empire to AD 117.

by Undevicesimus

From its humble origins as a group of villages on the Tiber in the plains of Latium, Rome came to control one of the greatest empires in history, reaching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Tigris and from the North Sea to the Sahara Desert. Its extensive legacy continues to serve as a lowest common denominator not only for the nations and peoples within its erstwhile borders, but much of the modern world at large. Roman law is the foundation for present-day legal systems across the globe, the Latin language survives in the Romance languages spoken on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and beyond, Roman settlements developed into some of Europe’s most important cities and stood model for many others, Roman architecture left some of history’s finest manmade landmarks, Christianity – the Roman state religion from AD 395 – remains the world’s dominant faith and Rome continues to feature prominently in Western popular culture… Rome rose in a geographically favourable location: on the left bank of the Tiber, not too far from the sea but far enough inland to be able to control important trade routes in central Italy: southwest from the Apennines alongside the Tiber, and from Etruria southeast into Latium and Campania. In later ages, the Romans always had much to tell about the founding and early history of their city: tales about the twin brothers Romulus and Remus being raised by a she-wolf, the founding of Rome by Romulus on 21 April 753 BC and the reign of the Seven Kings (of which Romulus was the first). According to Roman accounts, the last King of Rome – Tarquinius Superbus – was expelled in 510 BC, after which the Roman aristocracy established a republic ruled by two annually elected magistrates (Latin: pl. consulis) with the support of the Senate (Latin: senatus), a council made up of the leaders of the most prominent Roman families. Often at odds with their neighbours, the Romans considered military service one of the greatest contributions common people could make to the state and the easiest way for a consul to gain both power and prestige by protecting the republic. The Romans booked their first major triumph by conquering the Etruscan city Veii in 396 BC and went on to defeat most of the Latin cities in central Italy by 338 BC, despite the Celtic sack of Rome in 387 BC. Throughout the second half of the fourth century BC, the republic expanded in two different ways: direct annexation of enemy territory and the creation of a complex system of alliances with the peoples and cities of Italy. Shortly after 300 BC, nearly all the peoples of Italy united to stop Roman expansion once and for all – among them the Samnites, Umbrians, Etruscans and Celts. Rome obliterated the coalition in the decisive Battle of Sentinum (295 BC) and thus became the strongest power in Italy. By 264 BC, Rome controlled the Italian peninsula up to the Po Valley and was powerful enough to challenge its principal rival in the western Mediterranean: Carthage. The First Punic War began when the Italic people of Messana called for Roman help against both Carthage and the Greeks of Syracuse, a request which was accepted surprisingly quickly. The Romans allied with Syracuse, conquered most of Sicily and narrowly defeated the Carthaginian navy at Mylae in 264 BC and Ecnomus in 256 BC – the largest naval battles of Antiquity. Roman fleets gained a decisive victory off the Aegates Islands in 241 BC, ending the war and forcing the Carthaginians to abandon Sicily. Taking advantage of Carthage’s internal troubles, Rome seized Sardinia and Corsica in 238 BC. Rome’s frustration at Carthage’s resurgence and subsequent conquests in Spain sparked the Second Punic War, in which the Carthaginian commander Hannibal crossed the Alps and invaded the Italian peninsula. The Romans suffered massive defeats at the Trebia in 218 BC, Lake Trasimene in 217 BC and most famously at Cannae in 216 BC where over 50,000 Romans were slain – the largest military loss in one day in any army until the First World War. However, Hannibal failed to press his advantage and continued an increasingly pointless campaign in Italy while the Romans conquered the Carthaginian territory in Spain and ultimately brought the war to Africa. Hannibal’s army made it back home but was decisively defeated by Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, securing Rome’s hard-fought victory in arguably the most important war in Roman history. Firmly in command of much of the western Mediterranean, Rome turned its attention eastwards to Greece. Less than fifty years after the Second Punic War, Rome had crushed the Macedonian kingdom – an erstwhile ally of Hannibal – and formally annexed the Greek city-states after the destruction of Corinth in 146 BC. That very same year, the Romans finished off the helpless Carthaginians in much the same way, burning the city of Carthage to the ground and annexing its remaining territory into the new province of Africa. With Carthage, Macedon and the Greek cities out of the way, Rome was free to deal with the Hellenic kingdoms in Asia Minor and the Middle East, the remnants of Alexander the Great’s empire. In 133 BC, Attalus III of Pergamum left his realm to Rome by testament, gaining the Romans their first foothold in Asia. As the Romans expanded their borders, the unrest back in Rome and Italy increased accordingly. The wars against Carthage and the Greeks had seriously crippled the Roman peasants whom abandoned their home to campaign for years in distant lands, only to come back and find their farmland turned into a wilderness. Many peasants were thus forced to sell their land at a ridiculously low price, causing the emergence of an impoverished proletarian mass in Rome and an agricultural elite in control of vast swathes of countryside. This in turn disrupted army recruitment, which heavily relied on middle class peasants who were able to afford their own arms and armour. Two possible solutions could remove this problem: a redistribution of the land so that the peasantry remained wealthy and large enough to be able to afford their military equipment and serve in the army, or else allowing the proletarian masses to enter military service and make the army into a professional body. However, both options would threaten the position of the Roman Senate: a powerful peasantry could press calls for more political influence and a professional army would bind soldiers’ loyalty to their commander instead of the Senate. The senatorial elite thus stubbornly clung to the existing institutions which were undermining the republic they wanted to uphold. More importantly, the Senate’s attitude and increasingly shaky position, in addition to the growing internal tensions, created a perfect climate for overly ambitious commanders seeking to turn military prestige gained abroad into political power back home. Roman successes on the frontline nevertheless continued: Pergamum was turned into the province of Asia in 129 BC, Roman forces sacked the city of Numantia in Spain that same year, the Balearic Islands were conquered in 123 BC, southern Gaul became the new province of Gallia Narbonensis in 121 BC and the Berber kingdom of Numidia was dealt a defeat in the Jughurtine War (112 – 106 BC). The latter conflict provided Gaius Marius the opportunity to reform his army without senatorial approval, allowing proletarians to enlist and creating a force of professional soldiers who were loyal to him before the Senate. Marius’ legions proved their efficiency at the Battles of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC and Vercellae in 101 BC, virtually annihilating the migratory invasions of the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones. Marius subsequently used his power and prestige to secure a land distribution for his victorious forces, thus setting a precedent: any successful commander with an army behind him could now manipulate the political theatre back in Rome. Marius was succeeded as Rome’s leading commander by Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who gained renown when Rome’s Italic allies – fed up with their unequal status – attempted to renounce their allegiance. Rome narrowly won the ensuing Social War (91 – 88 BC) and granted the Italic peoples full Roman citizenship. Sulla left for the east in 86 BC, where he drove back King Mithridates of Pontus, whom had sought to benefit from the Social War by invading Roman territories in Asia and Greece. Sulla marched on Rome itself in 82 BC, executed many of his political enemies in a bloody purge and passed reforms to strengthen the Senate before voluntarily stepping down in 79 BC. Sulla’s retirement and death one year later allowed his general Pompey to begin his own rise to prominence. Following his victory in the Sertorian War in 72 BC, Pompey eradicated piracy in the Mediterranean Sea in 67 BC and led a campaign against Rome’s remaining eastern enemies in 66 BC. Pompey drove Mithridates of Pontus to flight, annexed Pontic lands into the new province of Bithynia et Pontus and created the province of Cilicia in southern Asia Minor. He proceeded to destroy the crumbling Seleucid Empire and turned it into the new province of Syria in 64 BC, causing Armenia to surrender and become a vassal of Rome. Pompey’s legions then advanced south, took Jerusalem and turned the Hasmonean Kingdom in Judea into a Roman vassal as well. Upon his triumphant return to Rome in 61 BC, Pompey made the significant mistake of disbanding his army with the promise of a land distribution, which was refused by the Senate in an attempt to isolate him. Pompey then concluded a political alliance with the rich Marcus Licinius Crassus and a young, ambitious politician: Gaius Julius Caesar. The purpose of this political alliance – known in later times as the First Triumvirate – was to get Caesar elected as consul in 59 BC, so that he could arrange the land distribution for Pompey’s veterans. In return, Pompey would use his influence to make Caesar proconsul and thus give him the chance to levy his own legions and become a man of power in the Roman Republic. Crassus, the richest man in Rome, funded the election campaign and easily got Caesar elected as consul, after which Caesar secured Pompey’s land distribution. Everything went according to plan and Caesar was made proconsul of Gaul for five years, starting in 58 BC. In the following years, Caesar and his legions systematically conquered all of Gaul in a war which has been immortalised in the accounts of Caesar himself (‘Commentarii De Bello Gallico’). Despite fierce resistance and massive revolts led by the Gallic warlord Vercingetorix, the Gallic tribes proved unable to inflict a decisive defeat on the Romans and were all subdued or annihilated by 51 BC, leaving Caesar’s power and prestige at unprecedented heights. With Crassus having fallen at the Battle of Carrhae against the Parthians in 53 BC, Pompey was left to try and mediate between Caesar and the radicalised Roman proletariat on one side and the politically hard-pressed Senate on the other. However, Pompey had once been where Caesar was now – the champion of Rome – and ultimately chose to side with the Senate, realising his own greatness had become overshadowed by Caesar’s staggering military successes and popularity among the masses. When Caesar’s term as proconsul ended, the Senate demanded that he step down, disband his armies and return to Rome as a mere citizen. Though it was tradition for a Roman commander to do so, rendering Caesar theoretically immune from any senatorial prosecution, the existing political situation made such demands hard to meet. Caesar instead offered the Senate to extend his term as proconsul and leave him in command of two legions until he could be legally elected as consul again. When the Senate refused, Caesar responded by crossing the Rubicon – the northern border of Roman Italy which no Roman commander should cross with an army – and marched on Rome itself in 49 BC. Pompey and most of the senators fled to Dyrrhachium in Greece and assembled their forces while Caesar turned around and conducted a lightning campaign in Spain, defeating the legions loyal to Pompey at the Battle of Ilerda. Caesar crossed the Adriatic Sea in 48 BC, narrowly escaping defeat by Pompey at Dyrrhachium and retreating south. Pompey clumsily failed to press his advantage and his forces were in turn decisively defeated by Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus on 6 June 48 BC. Pompey fled to Egypt in hopes of being granted sanctuary by the young king Ptolemy XIII, who instead had him assassinated in an attempt at pleasing Caesar, who was in pursuit. Ptolemy XIII was driven from power in favour of his older sister Cleopatra VII, with whom Caesar had a brief romance and his only known son, Caesarion. In the spring and summer of 47 BC, another lightning campaign was launched northwards through Syria and Cappadocia into Pontus, securing Caesar’s hold on Rome’s eastern reaches and decisively defeating the forces of Pharnaces II of Pontus, who had attempted to profit from Rome’s internal strife. Caesar invaded Africa in 46 BC and cleared Pompeian forces from the region at the Battles of Ruspina and Thapsus before returning to Spain and defeating the last resistance at the Battle of Munda in 45 BC. Caesar subsequently began transforming the Roman government from a republican one meant for a city-state to an imperial one meant for an empire. Major reforms were required to achieve this, many of which would be opposed by Caesar’s political enemies. This was a problem because several of these people enjoyed significant political influence and popular support (cf. Cicero) and while none of them could really challenge Caesar individually and publicly, collectively and secretly they could be a serious threat. To render his enemies politically impotent, Caesar consolidated his popularity among the Roman masses by passing reforms beneficial to the proletariat and enlarging the Senate to ensure his supporters had the upper hand. He then manipulated the Senate into granting him a number of legislative powers, most prominently the office of dictator for ten years, soon changed to dictator perpetuus. Though widely welcomed by the masses, Caesar’s reforms and legislative powers dismayed his political opponents, whom assembled a conspiracy to murder him and ‘liberate’ Rome. The conspirators, of whom Brutus and Cassius are the most famous, were successful and Caesar was brutally stabbed to death on 15 March 44 BC. Caesar’s death left a power vacuum which plunged the Roman world into yet another civil war. In his testament, Caesar adopted as his sole heir his grandnephew Gaius Octavius, henceforth known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Octavian, in English). Despite being only eighteen, Octavian quickly secured the support of Caesar’s legions and forced the Senate to grant him several legislative powers, including the consulship. In 43 BC, Octavian established a military dictatorship known as the Second Triumvirate with Caesar’s former generals Mark Antony and Marcus Lepidus. Caesar’s assassins had meanwhile fled to the eastern provinces, where they assembled forces of their own and subsequently moved into Greece. Octavian and Antony in turn invaded Greece in 42 BC and defeated them at the Battles of Philippi. Octavian, Antony and Lepidus then divided the Roman world between them: Octavian would rule the west, Antony the east and Lepidus the south with Italy as a joint-ruled territory. However, Octavian soon proved himself a brilliant politician and strategist by quickly consolidating his hold on both the western provinces and Italy, smashing the Sicilian Revolt of Sextus Pompey (son of) in 36 BC and ousting Lepidus from the Triumvirate that same year. Meanwhile, Antony consolidated his position in the east but made the fatal mistake of becoming the lover of Cleopatra VII. In 32 BC, Octavian manipulated the Senate into a declaration of war upon Cleopatra’s realm, correctly expecting Antony would come to her aid. The two sides battled at Actium on 2 September 31 BC, resulting in a crushing victory for Octavian, despite Antony and Cleopatra escaping back to Egypt. Octavian crossed into Asia the following year and marched through Asia Minor, Syria and Judea into Egypt, subjugating the eastern territories along the way. On 1 August 30 BC, the forces of Octavian entered Alexandria. Both Antony and Cleopatra perished by their own hand, leaving Octavian as the undisputed master of the Roman world. Octavian assumed the title of Augustus in January 27 BC and officially restored the Roman Republic, although in reality he reduced it to little more than a facade for a new imperial regime. Thus began the era of the Principate, named after the constitutional framework which made Augustus and his successors princeps (first citizen), commonly referred to as ‘emperor’, and which would last approximately two centuries. Augustus nevertheless refrained from giving himself absolute power vested in a single title, instead subtly spreading imperial authority throughout the republican constitution while simultaneously relying on pure prestige. Thus he avoided stomping any senatorial toes too hard, remembering what had happened to Julius Caesar. Augustus and his successors drew most of their power from two republican offices. The title of tribunicia potestes ensured the emperor political immunity, veto rights in the Senate and the right to call meetings in both the Senate and the concilium plebis (people’s assembly). This gave the emperor the opportunity to present himself as the guardian of the empire and the Roman people, a significant ideological boost to his prestige. Secondly, the emperor held imperium proconsulare. Imperium implied the emperor’s governorship of the so-called imperial provinces, which were typically border provinces, provinces prone to revolt and/or exceptionally rich provinces. These provinces obviously required a major military presence, thereby securing the emperor’s command of most of the Roman legions. The title was proconsulare because the emperor enjoyed imperium even without being a consul. The emperor furthermore interfered in the affairs of the (non-imperial) senatorial provinces on a regular basis and gave literally every person in the empire the theoretical right to request his personal judgement in court cases. Roman religion was also brought under the emperor’s wings by means of him becoming pontifex maximus (supreme priest), a position of major ideological importance. On top of all this, the Senate frequently granted the emperor additional rights which enhanced his power even more: supervision over coinage, the right to declare war or conclude peace treaties, the right to grant Roman citizenship, control over Roman colonisation across the Mediterranean, etc. The emperor was thus the supreme administrator, commander, priest and judge of the empire – a de facto absolute ruler, but without actually being named as such. It is worth noting that Augustus and most of his immediate successors worked hard to play along in the empire’s republican theatre, which gradually faded as the centuries passed. The most important questions nonetheless remained the same for a long time after Augustus’ death in AD 14. Could the emperor keep himself in the Senate’s good graces by preserving the republican mask? Or did he choose an open conflict with the Senate by ruling all too autocratically? Even a de facto absolute ruler required the support and acceptance of the empire’s elite class, the lack of which could prove to be a serious obstacle to any imperial policies. The relationship between the emperor and the Senate was therefore of significant importance in maintaining the political work of Augustus, particularly under his immediate successors. The first four of these were Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero – the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Tiberius was chosen by Augustus as successor on account of his impressive military service and proved to be a capable (if gloomy) ruler, continuing along the political lines of Augustus and implementing financial policies which left the imperial treasuries in decent shape at his death in AD 37 and Caligula’s accession. Despite having suffered a harsh youth full of intrigues and plotting, Caligula quickly gained the respect of the Senate, the army and the people, making a hopeful entry into the Principate. Yet continuous personal setbacks turned Caligula bitter and autocratic, not to say tyrannical, causing him to hurl his imperial power head-first into the senatorial elite and any dissenting groups (most notably the Jews). After Caligula’s assassination in AD 41, the position of emperor fell to his uncle Claudius who, despite a strained relationship with the Senate, managed to play the republican charade well enough to implement further administrative reforms and successfully invade the British Isles to establish the province of Britannia from AD 43 onward. But the Roman drive for expansion had been somewhat tempered after Augustus’ consolidating conquests in Spain, along the Danube and in the east. The Romans had practically turned the Mediterranean Sea into their own internal sea (Mare Internum or Mare Nostrum) and thus switched to territorial consolidation rather than expansion. However, the former was still often accomplished by the latter as multiple vassal states (Judea, Cappadocia, Mauretania, Thrace etc.) were gradually annexed as new Roman provinces. Actual wars of aggression nevertheless ceased to be a main item on the Roman agenda and indeed, the policies of consolidation and pacification paved the way for a long period of internal peace and stability during the first and second centuries AD – the Pax Romana. This should not be idealised, though. On the local level, violence was often one of the few stable elements in the lives of the common people across the empire. Especially among the lowest ranks of society, crimes such as murder and thievery were the order of the day but were typically either ignored by the Roman authorities or answered with brute force. Moreover, the Romans focused on safeguarding cities and places of major strategic or economic importance and often cared little about maintaining order in the vast countryside. Unpleasant encounters with brigands, deserters or marauders were therefore likely for those who travelled long distances without an armed escort. At the empire’s frontiers, the Roman legions regularly fought skirmishes with their local enemies, most notably the Germanic tribes across the Rhine-Danube frontier and the Parthians across the Euphrates. Despite all this, the big picture of the Roman world in the first and second centuries AD is indeed one of lasting stability which could not be discredited so easily. The real threat to the Pax Romana existed not so much in local violence, shady neighbourhoods or frontier skirmishes but rather in the highest ranks of the imperial court. The lack of both dynastic and elective succession mechanisms had been the Principate’s weakest point from the outset and would be the cause of major internal turmoil on several occasions. Claudius’ successor Nero succeeded in provoking both the Senate and the army to such an extent that several provincial governors rose up in open revolt. The chaos surrounding Nero’s flight from Rome and death by his own hand plunged the empire into its first major succession crisis. If the emperor lost the respect and loyalty of both the Senate and the army, he could not choose a successor, giving senators and soldiers a free hand to appoint the persons they considered suitable to be the new emperor. This being the exact situation upon Nero’s death in AD 68, the result was nothing short of a new civil war. To further add to the catastrophe, the civil war of AD 68/69 (the Year of Four Emperors) allowed for two major uprisings to get out of hand – the Batavian Revolt near the mouths of the Rhine and the First Jewish-Roman War in Judea. Both of these were ultimately crushed with significant difficulties, especially in Judea where Jewish religious-nationalist sentiments capitalised on existing political and economic unrest. Though the Romans achieved victory with the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 and the expulsion of the Jews from the city, Judea would remain a hotbed for revolts until deep into the second century AD. The fact that major uprisings arose at the first sign of trouble within the empire might cause one to wonder about the true nature of the Pax Romana. Was it truly the strong internal stability it is popularly known to be? Or was it little more than a forced peace, continuously threatened by socio-economic and political discontent among the many different peoples under the Roman yoke? Though a bit of both, the answer definitely leans towards the former hypothesis. While the Pax Romana lasted, unrest within the empire remained limited to a few hotbeds with a history of resisting foreign conquerors. Besides the obvious example of the Jewish people in Judea, whose anti-Roman sentiments largely stemmed from their unique messianic doctrines, large-scale resistance against the Romans was scarce. It is true that the incorporation and Romanisation of unique societies near the empire’s northern frontiers led to severe socio-economic problems and subsequent uprisings, most notably Boudica’s Rebellion in Britain (AD 60 – 61) and the aforementioned Batavian Revolt near the mouths of the Rhine. Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that the Pax Romana was strong enough to outlast a few pockets of rebellion and even a major succession crisis like the one of AD 68/69. The Year of the Four Emperors ultimately brought to power Vespasian, founder of the Flavian dynasty (AD 69 – 96) and architect of an intensified pacification policy throughout the empire. These policies were fruitful and strengthened the constitutional position of the emperor, not in the least owing to the fact that Vespasian’s sons and successors Titus and Domitian were as capable as their father. However, their skills did not prevent Titus and especially Domitian from bickering with the senatorial elite over the increasingly obvious monarchical powers of the emperor. In the case of the all too authoritarian Domitian, the conflict escalated again and despite his competent (if ruthless) statesmanship, Domitian was murdered in AD 96. A new civil war was prevented by diplomatic means: Nerva emerged as an acceptable emperor to both the Senate and the army, especially when he adopted the popular Trajan as his son and heir. Thus began the reign of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty (AD 96 – 192). Having succeeded Nerva in AD 98, Trajan once more steered the empire onto the path of aggressive expansion, leading the Roman legions across the Danube to crush the Dacians and establish the rich province of Dacia in AD 106. Subsequently, the Romans seized the initiative in the east, drove back the Parthians and advanced all the way to the Persian Gulf (Sinus Persicus). Trajan annexed Armenia in AD 114 and turned the conquered Parthian lands into the new provinces of Mesopotamia and Assyria in AD 116. Trajan died less than a year later on 9 August AD 117, his staggering military successes having brought the Roman Empire to its greatest extent ever…

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPQR- Mary Beard; Ch 5

5 A Wider World Roman literature and roman territorial expansion went hand in hand. Rome had used writing for basic communication since its inception. But with its increasing interaction, particularly with Greece, it began to attempt its own literature. At first it was aping Greek literature.

Polybius was one of the first to ask philosophical questions about what made Rome so successful.

In 280 BC, Pyrrhus came from northern Greece to aid Tarentum against Rome. He won, but at such a cost that he remarked "He could not afford any more such victories." From that time to 146 BC when the Romans finally destroyed Carthage, there was nearly continuous warfare.

The first Punic (Carthaginian) war lasted from 264 – 241 BC. It was fought largely in Sicily and ended in Roman control of the island.

The second Punic war was fought between 218 – 201 BC. It started in Spain, but ended with Carthage recalling Hannibal back home as they were increasingly uneasy about the odds. Hannibal had enlisted the Macedonian king Perseus in the fight, but his defeat meant Roman control over Greece in 168 BC.

The Romans also had to engage the Gauls in the 220's, and Antiochus of Syria in 190 BC.

Military campaigning was a way of life for Romans. And one of the consequences of military success overseas was that the profits of warfare made Rome the richest people known in the world. Thousands of captives poured in and became the slave labor that worked Roman fields, mines, and mills. Roman reconstruction and new construction took off, and for a while, Rome's coffers overflowed so that Rome became a tax free zone.

But these changes destabilized the culture too. So much wealth and luxury had an effect on Rome. The expansion of power raised debates and paradoxes about Rome's place in the world, and what counted as "Roman" when so much of the Mediterranean was under Roman control. Winning brought its own problems.

Cannae and the elusive face of battle Hannibal had crossed the Alps and won a decisive battle at Cannae. Romans were in a panic about his eventual invasion of the city. But for some unknown reason, Hannibal stopped and gave the Romans time to recover. Quintus Fabius took command after Cannae and avoided direct confrontation with Hannibal. He waited, and he combined guerilla tactics with a scorched earth policy to wear down the enemy. Scipio Africanus was the more dashing leader and wanted a more direct confrontation.

Perhaps more than anything else, it was Rome's commitment to continue the fight, at any cost, that eventually won the war. Hannibal himself maybe understood that Rome's manpower was due to their relations with those allied to them, and he tried to win them over to his own side. But he never managed it successfully enough to undermine the Romans. Polybius himself goes into this at length, describing the strength and stability of Rome's political structures.

Polybius on the politics of Rome Polybius was a Greek from the Peloponnese that was captured when Perseus lost to Rome. Perseus was an educated writer and as such was placed higher than many slaves. He noted that Romans were afraid of the gods, but that they also were systematically efficient in organization.

The stories of Roman valor, heroism, and self-sacrifice were told to the young to inspire them to endure all for the common good. But Polybius noted within the Roman state structure itself, that there was a mixed constitution that pulled the best aspects of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. The consuls were the monarchical element. The senate was the aristocratic element, and the people were the democratic element. There was a set of checks and balances on each so that none could entirely prevail. In fact, speaking of democracy is a bit misleading, because we tend to see it in our modern terms. Democracy at root means mob rule. Romans fought for liberty, not democracy.

Even though the plebs had won the right to participate, office was still only available to both wealthy plebs and wealthy patricians. But that didn't mean the poor were ignored. In fact, there support was sought after by those in office. Since the rich were rarely united on issues, those that did campaign sought to convince the poor public that their policies were the best. The rich had to learn the lesson that they depended on the people as a whole.

An empire of obedience The Romans didn't start out bent on vast conquest or in the belief of some manifest destiny. They had a thirst for glory and economic profits, but so did their neighbors. They were not the only agents in the process and they didn't march across peace-loving people who were just minding their own business until the thuggish Romans came along. The Mediterranean was a vast area of shifting alliances and continuous brutal violence. The more powerful Rome was perceived to be, the more these warring parties sought to enlist the Romans as allies in their own power struggles. Of course as Rome gained control over these areas they did impose their will to greater or lesser degrees.

The impact of empire As conquered peoples were brought to Rome, Romans traveled to far flung corners of the empire too. By the mid second century BC, probably over half the adult male citizens of Rome would have seen something of the world abroad, leaving children where they went. The Roman population had become the most traveled of any state ever in the Mediterranean.

How to be Roman This wider view of the world also allowed the Romans to be more realistic about themselves. Their sculpture, realistic in the capture of flaws, expressed a willingness to see themselves accurately, and often call out their society for its lack of living up to its own standards.

0 notes

Text

Thunderbolt 216 BC: Rise of Roman Republic /3

Thunderbolt 216 BC: Rise of Roman Republic /3

216 B.C.

“Then it is unanimous. Verucosus is named Dictator for the next 12 months. He shall have absolute authority over all military operations. His primary mission is to protect Rome and her citizens then the provinces surrounding her.”

Verucosus stood to muted applause. “ Senators I will be brief. We shall raise an army of such size and quality that Hannibal will quake. “ But we…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

On this Day | 18 December

Battles of the Second Punic War.

In 218 BC, during the Second Punic War, Hannibal’s Carthaginian army decisively defeated Roman forces on Italian soil at the Battle of Trebia.

#Classics#tagamemnon#ancient history#history#roman history#rome#ancient rome#carthage#Hannibal#Battle of Trebia#trebia#punic wars#second punic war#218 BC#on this day#onthisday#18 december

20 notes

·

View notes