#Post-pleistocene

Text

The Mun Alligator

Somehow 2023 felt like a slow year for new croc taxa, but I'm happy to report that a new one just dropped yesterday.

This new crocodilian is a member of the genus Alligator, which today only includes two living species, the American Alligator and the Chinese Alligator. This new species, Alligator munensis, lived during the Quaternary in what is now Thailand and may be an important species for understanding Asian alligators.

Art by Márton Szabó and size chart by yours truly

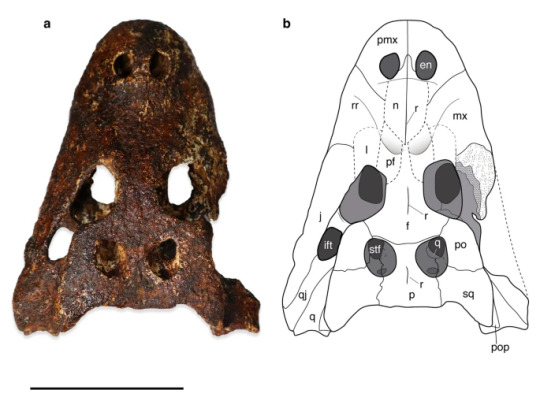

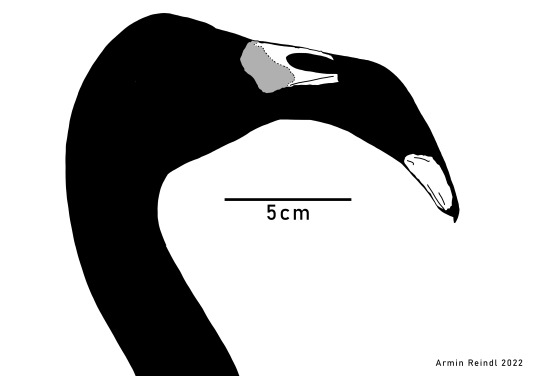

Before we go into the mystery of the Asian alligators and their origin, lets just take a moment to appreciate how weird this guy is. The skull is very short and very deep (altirostral), it was obviously small like its modern relative the Chinese Alligator and its nostrils were weirdly pulled back, with a huge bony element separating them externally. The later looks especially weird when you know alligator skulls, where the nasals do extend over the nares, but never this much. For comparisson, below is an image of the Mun Alligator in a, Chinese Alligator in e and American Alligator in i, as well as a close up.

As you can see in the close up, the skull was also adorned by various ridges, both across the snout and the skulltable. Now the ridges beofre the eyes aren't unique to Alligator munensis, but I still want to highlight them as they are called spectacles. Just think that's something people should know (it's also what gives Spectacled Caimans their name).

What is sadly missing is the dentition, the teeth. This of course leaves out a big indicator of the diet. Which all in all leaves the ecology a bit unknown (we don't know why it has those weird nostrils either). However, Darlim and colleagues still found some clues. Notably, the tooth sockets in the back of the jaw are enlarged, something that's usually seen with globular teeth or teeth that are blunt and sideways flattened. Alligators actually derive from ancestors with globular teeth, which then became more generalized. Well, Alligator munensis may have done another switcheroo and gone back to that. Combining globular teeth with strong jaw muscles (check) and robust skulls (double check) could indicate that it could have fed on hard-shelled prey items. Now this doesn't mean it was specialised per say. Big turtles have big heads and do seasonally feed on snails, but are otherwise omnivores. Multiple alligatorids on the other hand lack globular teeth, but that doesn't stop them from taking hard-shelled prey regardless.

Images showing Caimans feeding on apple snails by Paul Williams and the BBC as well as an American Alligator eating a turtle by Okreb.

Now to discuss the history of Asian alligator species. It does seem rather strange that all extant alligatorids are from the Americas with the exception of the Chinese Alligator and it has been a long mystery how and when they got there. This isn't helped by the fact that alligator fossils from Asia are very much understudied. The Mun Alligator however shows what is to be expected, that diversity was a lot higher in prehistory than it is today. And it wasn't even that long ago, with the deposits dating to the Pleistocene or maybe even Holocene.

However, it doesn not solve the mystery entirely. While both the Chinese Alligator and the Mun Alligator are thought to be closely related, they are not ancestor and descendent. Instead, they seem to have diverged quite some time ago and evolved isolated from one another. That is still an interesting thought tho.

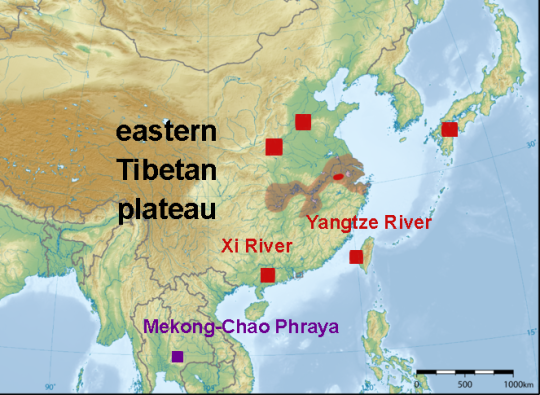

Darlim and colleagues suggest that this could all date back to the Miocene, when the ancestor of these two species inhabited the wetlands of eastern Asia. When plate tectonics caused the Himalayas to form and the Tibetan Plateau to be lifted up, both appear to have been split into distinct river systems. The ancestor of the Chinese Alligator into the Xi and Yangtze river systems and the Mun Alligator into the Mekong and Chao Phraya river systems.

Based on this hypothesis, and figures by Iijima, Takahashi, & Kobayashi (2016) chronicling the fossil record and distribution of Chinese Alligators, I put together this handy-dandy map that should illustrate the whole affair. Red for A. sinensis, purple for A. munensis. The red and transparent red areas are the formers current and former range, whereas squares represent fossil discoveries.

For any wanting to look deeper, there is of course the Wikipedia page Alligator munensis - Wikipedia or the paper, which is open access.

An extinct deep-snouted Alligator species from the Quaternary of Thailand and comments on the evolution of crushing dentition in alligatorids | Scientific Reports (nature.com)

#paleontology#crocodile#palaeoblr#prehistory#croc#long post#alligator#alligator munensis#chinese alligator#mun alligator#pleistocene#holocene#asia#fossils#crocodilia#alligatoridae#science

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

6, 8, 9 and 20 for the ask game!

Thank you!!

6. What are you craving?

I feel like watermelon would really hit the spot right now. Ooh, maybe a watermelon beverage.

8. Last thing you watched?

The Killer (2023) dir. David Fincher. It was surprisingly slow and cerebral, and it had a lot of really unexpected themes for a movie about a contract killer.

9. Shows on your watch list?

I don't watch TV as often as I watch movies, but I am really enjoying the first season of Star Trek: The Next Generation. I'd like to watch the original Trek show soon!

20. Are you a gamer? What was the last game you played?

Ok, this is really easy to answer. So: I am absolutely not a gamer. I'm probably the most clueless person in the world when it comes to video games. However, back in May I decided to get Assassin's Creed: Origins on a whim (I just really wanted to walk around a nicely rendered Ancient Egypt) and now I'm playing that in bits and pieces. This has resulted in a few very funny incidents (like me accidentally drowning my camel while trying to run away) and I'm sure I'd give a more experienced gamer a heart attack if they saw how I play, but I'm having a blast. Ass Creed is the first and last game I've played so far!

#thanks again!!#also- because of your sound of music-posting that movie is definitely on my watchlist as well#I'm long overdue for a rewatch#pleistocene answers asks

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books about the La Brea Tar Pits! I love each of them dearly <3

Rancho La Brea: Death Trap and Treasure Trove, edited by John M. Harris, 2001

Rancho La Brea: A Record of Pleistocene Life in California, by Chester Stock, 1930

Rancho La Brea: Treasures of the Tar Pits, edited by John M. Harris and George T. Jefferson, 1985

#books#my library#la brea tar pits#rancho la brea#tar pits#pleistocene#ice age#john m harris#chester stock#george t jefferson#2001#1930#1985#2000s#1930s#1980s#they have their own posts already but its nice to see them all together <33

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#driftless area#geography#geology#Pleistocene glaciation#interesting#right next door to the sand counties#which were covered by glaciers#my posts

0 notes

Text

The most common mistake people make when thinking about prehistory and how to avoid it.

In "The Dawn of Everything, A New History for Humanity" David Graeber gives what I think might be the best piece of advice I've ever heard for understanding deep human history, and that is to get your mind out of the Garden of Eden.

People speculating about prehistory before modern archeology were quick to frame early humanity as existing in a "state of nature", either with pure innocent tribal communism, or being brutish barbarous cavemen, then something happened to bring us from the state of nature into "society". Did we make a Faustian bargain by domesticating plants and animals? Why is evidence of intergroup violence in prehistory so rare? How did we fall from the innocent state of nature? This, of course, smacks of the biblical creation story, so even if people don't believe it literally, they seem to have a hard time letting go of it spiritually even in a secular context.

This is pretty much nonsense, of course. Humans have existed for over 2 million years. Anatomically modern humans have existed for at least 300 thousand years. Behaviourally modern humans (with symbolism, art, long distance trade, political awareness) have existed for at least 50 thousand years, from our best evidence, but possibly a lot longer. The time between the Sumerians inventing writing and urban living 5,000 years ago and now is only a narrow slice of human history.

If we want to understand human history properly, we shouldn't understand people of the past as fundamentally different from us. They were intelligent, politically aware people doing their best in the world they found themselves in, just like we are today. We didn't fall from innocence with the development of behavioral modernity, religion, farming, war, money, capitalism, computers, or anything else. The world has changed a lot, but people have been experimenting with different ways to live for as long as there have been people, like this example I've posted before about disabled people's role in late pleistocene Eurasian society.

People have been the same as we are now for at least the last 50 thousand years. We have lived in countless different ways and will continue to experiment. There was no fall, and we don't live at the end of history.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

You know you're too far gone when you start thinking about how interesting it is that permafrost response to climate change is complicated not only by future warming but how specific types of permafrost will respond to it.

#Misc reblogs#Anyways turns out pleistocene permafrost is less resilient to degradation post-thaw then Holocene permafrost

0 notes

Text

There was this post a while ago where somebody was saying that Cheetahs aren't well suited to Africa and would do well in Midwestern North America, and it reminded me of Paul S. Martin, the guy I'm always pissed off about.

He had some good ideas, but he is most importantly responsible for the overkill hypothesis (idea that humans caused the end-Pleistocene extinctions and that climate was minimally a factor) which led to the idea of Pleistocene rewilding.

...Basically this guy thought we should introduce lions, cheetahs, camels, and other animals to North America to "rewild" the landscape to what it was like pre-human habitation, and was a major advocate for re-creating mammoths.

Why am I pissed off about him? Well he denied that there were humans in North America prior to the Clovis culture, which it's pretty well established now that there were pre-Clovis inhabitants, and in general promoted the idea that the earliest inhabitants of North America exterminated the ecosystem through destructive and greedy practices...

...which has become "common knowledge" and used as evidence for anyone who wants to argue that Native Americans are "Not So Innocent, Actually" and the mass slaughter and ecosystem devastation caused by colonialism was just what humans naturally do when encountering a new environment, instead of a genocidal campaign to destroy pre-existing ways of life and brutally exploit the resources of the land.

It basically gives the impression that the exploitative and destructive relationship to land is "human nature" and normal, which erases every culture that defies this characterization, and also erases the way indigenous people are important to ecosystems, and promotes the idea of "empty" human-less ecosystems as the natural "wild" state.

And also Martin viewed the Americas' fauna as essentially impoverished, broken and incomplete, compared with Africa which has much more species of large mammals, which is glossing over the uniqueness of North American ecosystems and the uniqueness of each species, such as how important keystone species like bison and wolves are.

It's also ignoring the taxa and biomes that ARE extraordinarily diverse in North America, for example the Appalachian Mountains are one of the most biodiverse temperate forests on Earth, the Southeastern United States has the Earth's most biodiverse freshwater ecosystems, and both of these areas are also a major global hotspot for amphibian biodiversity and lichen biodiversity. Large mammals aren't automatically the most important. With South America, well...the Amazon Rainforest, the Brazilian Cerrado and the Pantanal wetlands are basically THE biodiversity hotspot of EVERYTHING excepting large mammals.

It's not HIM I have a problem with per se. It's the way his ideas have become so widely distributed in pop culture and given people a muddled and warped idea of ecology.

If people think North America was essentially a broken ecosystem missing tons of key animals 500 years ago, they won't recognize how harmful colonization was to the ecosystem or the importance of fixing the harm. Who cares if bison are a keystone species, North America won't be "fixed" until we bring back camels and cheetahs...right?

And by the way, there never were "cheetahs" in North America, Miracinonyx was a different genus and was more similar to cougars than cheetahs, and didn't have the hunting strategy of cheetahs, so putting African cheetahs in North America wouldn't "rewild" anything.

Also people think its a good idea to bring back mammoths, which is...no. First of all, it wouldn't be "bringing back mammoths," it would be genetically engineering extant elephants to express some mammoth genes that code for key traits, and second of all, the ecosystem that contained them doesn't exist anymore, and ultimately it would be really cruel to do this with an intelligent, social animal. The technology that would be used for this is much better used to "bring back" genetic diversity that has been lost from extant critically endangered species.

I think mustangs should get to stay in North America, they're already here and they are very culturally important to indigenous groups. And I think it's pretty rad that Scimitar-horned Oryx were brought back in their native habitat only because there was a population of them in Texas. But we desperately, DESPERATELY need to re-wild bison, wolves, elk, and cougars across most of their former range before we can think about introducing camels.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I was going to save these for later but it's Pride Month. Might as well post them,,

Anyway thank you @pleistocene-polina for helping me discover my new favorite game franchise

#artsing#metal gear solid#mgs#mgs1#metal gear#by 'helped me discover' i mean blasted liquimantis content at me on full auto#but ey. same thing#pride month#pride month 2024

543 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wild vs. Feral, Domesticated vs. Tame, Native vs. Invasive, and Why Words Matter

Originally posted on my website at https://rebeccalexa.com/wild-vs-feral/

Recently a post crossed my dash on Facebook featuring a small group of llamas in the forests of the Olympic Peninsula. The caption described them as “wild” llamas (Lama glama). That may seem pretty innocuous to the average person, but to a naturalist it’s a gross mischaracterization. For one thing, llamas are completely domestic animals, no more wild than a cow or dog; they are descended from the guanaco (Lama guanacoe), which is a truly wild camelid. So this means that the llamas on the peninsula are feral, not wild. But why does the distinction of wild vs. feral matter so much?

The terms we use to describe various species help us to understand their origin and, perhaps more importantly, their current ecological status. These concepts aren’t just relevant to scientists, however. Everyday people are constantly making decisions that can affect the ecosystems around them, and often these decisions are made without having a full understanding of their impact.

For example, look at how many people release unwanted pets into the wild, whether domesticated rabbits, goldfish, snakes, or other, more exotic animals. Some of these unfortunate animals end up dying pretty awful deaths due to starvation, exposure, or predation. But others manage to survive and reproduce, becoming the latest population of non-native–and potentially invasive–species in their ecosystem. This wouldn’t happen if more people understood the impact of non-native species, and how releasing captive animals puts native species at risk.

But it all starts with knowing that there’s a difference, and understanding the terms that explain why that difference exists. So let’s explore some vocabulary that can be used to describe species, whether animal, plant, or otherwise.

Let’s start with domestication, because there often seems to be confusion as to what makes a species domesticated. Domestication is a process that takes many years, often measured in centuries. Humans breed chosen animals for particular traits over a number of generations. As time passes, each subsequent generation becomes more different from the wild species it originated from, and eventually a new, fully domesticated species emerges from this process of artificial selection by humans.

Dogs (Canis familiaris or Canis lupus familiaris) are the first animal humans domesticated in a process that started about 30,000 years ago. They evolved from the now-extinct Pleistocene wolf, a particular lineage of the gray wolf (Canis lupus), and it’s likely that the partnership began as some wolves showed less fear of humans while scavenging from our kills. By 14,000 years ago dogs were a distinct species (or subspecies) from wolves.

Dogs display very different characteristics from wolves. Their faces tend to be shorter with a more pronounced stop (the bump in the forehead where the muzzle meets the rest of the skull.) Floppy ears and curled tails are common, as are patchy-colored coats. Dogs tend to have weaker muscles than wolves of a similar size, shorter legs and smaller feet, smaller teeth, and a smaller size overall. This is a phenomenon known as neoteny, in which domesticated animals have a tendency to retain more juvenile physical traits of their parent wild species, and you can see it in domesticated animals across the board.

But it’s not just physical appearances that matter. Behaviorally dogs are generally more friendly toward humans; in fact, they’ve even developed some human-friendly body language that wolves don’t have, like “puppy dog eyes.” They can be easily trained and, unless poorly socialized, dogs generally enjoy the company of humans.

In many ways, physically and behaviorally, a dog is a wolf that never grew out of its puppy stage. While a young wolf pup may be able to live in someone’s house for a short time, as they grow older they become more destructive and less tolerant of human company. Your dog may love watching out the window during a car ride, but a wolf is going to be much more stressed out by the experience. Even wolf-dog hybrids have to be treated differently than your average domesticated dog because the wolf content has a significant effect on behavior.

This is just one example of how domestication isn’t just a matter of a few generations of selective breeding. You can also compare domesticated horses (Equus ferus caballus) with Przewalski’s horses (Equus ferus przewalskii or Equus przewalskii) or zebras (subgenus Hippotigris), domesticated cows (Bos taurus) with stories of fierce wild aurochs (Bos primigenius), and so forth. In every case the wild and domesticated counterparts are very different in both appearance and behavior.

Now, what about the term “tame”? Many wild animal species have been tamed over the years, either wild-caught individuals or those born in captivity. These tame animals may be more docile in comparison to their fully wild counterparts, but this generally takes a lot of handling and socialization from a young age. Moreover, tame animals retain a lot more wild behaviors than domesticated ones.

Take those supposed “domesticated” foxes that people want to have as pets. Most of the foxes available as pets have no relation to those in the famous Russian fox domestication experiment, but are from modern fur farm lines. And in fact the study foxes came from Russian fur farms, so the researchers were beginning with pre-tamed animals rather than truly wild ones. While some tame foxes may be more amenable to human handling than wild foxes, they are by no means domesticated. They are more prone to wild behaviors like urinating everywhere to mark territory, chewing on anything they can get their jaws on, nipping, and making a LOT of noise. Moreover, whereas dogs adapted to eating an omnivorous diet after millennia of eating alongside us, foxes need a more specialized diet than what you can get at a pet store.

Unfortunately there are unscrupulous people within the exotic pet trade who will advertise their tame (at best) stock as “domesticated.” This often leads consumers to thinking that they’re getting a much more tractable animal that will be as easy to care for as a cat or dog, and sets up everyone involved for disaster (except, of course, the seller with a fatter wallet.)

Next, let's compare wild vs. feral. A wild species is one that has never been domesticated, nor have its ancestors. Generally it will be a native species to its ecosystem, though non-native species can also be introduced to an ecosystem without ever having been domesticated. A feral animal, on the other hand, is a member of a domesticated species that has escaped or been released back into the wild and has survived to reproduce new generations that have never been handled by humans.

I’ve often heard people refer to the feral swine (Sus domesticus) that have ravaged ecosystems worldwide as “wild pigs”. They may behave in a wild manner, and they certainly look rougher and hairier than your average well-fed domesticated pig on a farm. It’s not uncommon for feral animals to regain some traits of their wild ancestors. However, that does not make them truly wild.

If you manage to wrest away a litter of newborn piglets from a feral sow and bottle-feed them, they are likely to be able to be socialized and kept in captivity, though they may still physically resemble feral pigs. They haven’t lost the deeply-ingrained genes that carry domesticated traits. However, if you try to raise a newborn Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa) or red river hog (Potamochoerus porcus), it will lack the domesticated traits of its farm cousins and show more wild traits as it ages, making it a rather unsuitable pet or farm animal. We also see this return to domestic traits in mustangs and other feral horses captured at a young age. While a mustang born in the wild may be tougher to work with at first than a foal born in captivity and handled from birth, the mustang will be much more calm and easier to train than, say, a zebra.

The problem with referring to feral animals as “wild” is that this suggests they are a natural part of the ecosystem they are in. Because a truly domesticated species (or subspecies) is not the same as the parent species, it has no place to which it is native as a wild animal.

A native species is one that has evolved in a given ecosystem for thousands or even millions of years. In the process it has developed numerous intricate interrelationships with many other species in that ecosystem, creating a careful system of checks and balances. A non-native species is any species that has been taken out of the ecosystem in which it evolved and placed in a different ecosystem where it is not normally found.

For example, here in North America the mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) is a wild native species. While it may resemble domesticated pigeons, it has never been domesticated even when kept in captivity. The Eurasian collared dove (Streptopelia decaocto), on the other hand, was introduced to the Americas after a few dozen individuals were released in the Bahamas in 1974. The feral pigeon (Columba livia domestica) is a domesticated species derived from the rock dove (Columba livia), which is native to Europe, west Asia, and northern Africa. Both the collared dove and pigeon are examples of non-native species. Most non-native species do not offer any benefits to the ecosystems they are introduced to because they do not have established relationships with native species. When they compete with native species for resources, they weaken the ecosystem overall.

Non-native species can be further categorized as naturalized or invasive, or even both. A naturalized species is a non-native one that has managed to establish reproducing populations, rather than going extinct without becoming established. Unfortunately, some people take this to mean that the species has become fully integrated into the new ecosystem. However, this is a process that again takes thousands to millions of years as other species adapt to the newcomer, which itself often also changes as it adapts to its new environment.

Ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) are an example of a naturalized species in North America. Native to Asia and parts of Europe, they were introduced here as a game bird 250 years ago. While captive pheasants are regularly released into the wild to offer more hunting opportunities to humans, this species has likely been naturalized from its first introduction.

Again, “naturalized” doesn’t mean “natural”. Pheasants compete with native birds like northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) and prairie chickens (Tympanuchus spp.) Not only do they compete for food, nesting sites, and other resources, but they also spread diseases to native birds. Pheasants even engage in brood parasitism, laying their eggs in native birds’ nests and sometimes causing the native birds to abandon the nest and their own young entirely.

This means that the pheasants are also invasive as well as naturalized. Invasive species are non-natives that aggressively compete with, and sometimes displace or extirpate, native species. There are several hundred species that have become seriously invasive here, including both vertebrate and invertebrate animals, and numerous plants. But even the rest of the over 6000 non-native species that have become naturalized here still put pressure on native species, and have the potential to become invasive if their impact increases to a more damaging point.

Hopefully this gives you a clearer understanding of what these terms mean and why it’s important to know the difference. By knowing a little more about how your local ecosystem works and how different species may be contributing to or detracting from its overall health, you have more power to be able to make decisions that can preserve native species and help ecosystems be more resilient. Given that the removal of invasive species is one of the most important ways we can help ecosystems thrive in spite of climate change, it’s more important than ever that we increase nature literacy among the general populace. Consider this article just one small way to move that effort along.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#wildlife#animals#nature#biology#science#scicomm#invasive species#wild animals#domesticated fox#feral hogs#long post#vocabulary#ecology#educational#biodiversity#conservation#environment#environmentalism#climate change#pigeons

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

the birds of the "aDNA jp"

I need a name for this AU and "pleistocene park" is taken by something else

anyway

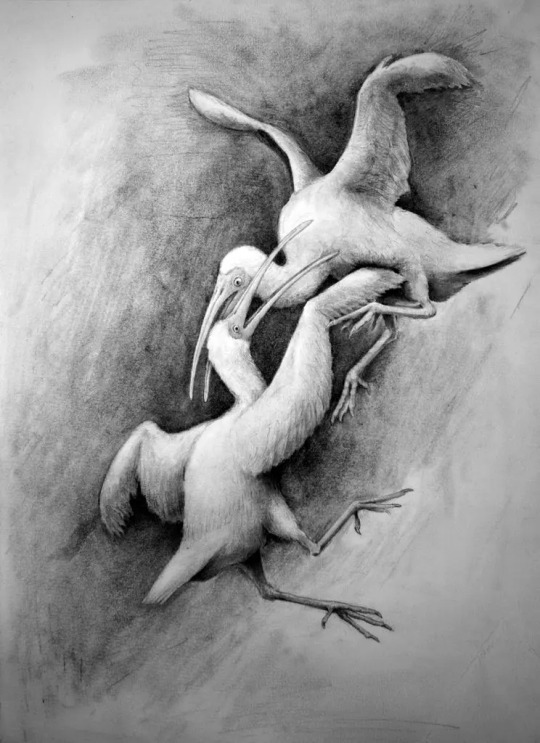

Pelagornis, a terrifying pseudotoothed bird (art by @quetzalpali-art)

Teratornis, a giant vulture relative (art by DiBgd, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Xenicibis, the Club-Winged Ibis (art sourced from NatGeo)

Haast's Eagle, the Moa Killer (art by @thewoodparable)

Moas, the top herbivores of New Zealand (art by @quetzalpali-art and @thewoodparable)

Aepyornis (and Vorombe, if that's a thing), the Elephant Bird, the largest bird to ever exist (art by @drawingwithdinosaurs)

The Giant Ground Owl (over one meter tall) (art by Stanton F. Fink, CC BY-SA 2.5)

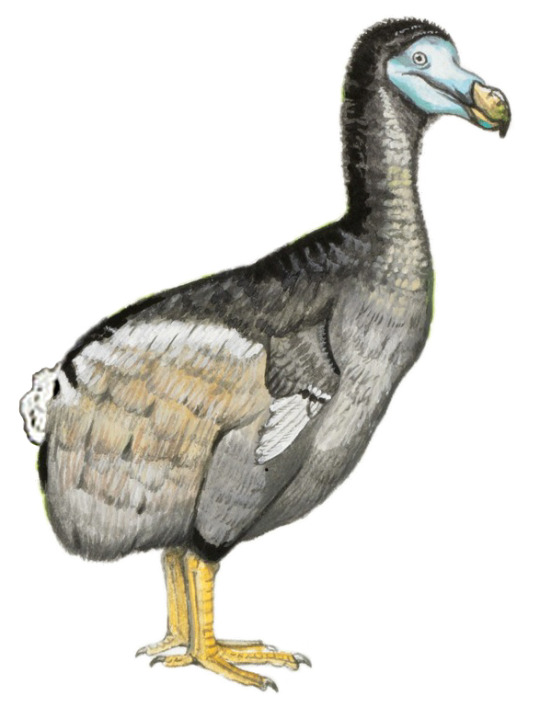

The Dodo (art by Julian P. Hume, CC BY 4.0)

The Passenger Pigeon, great eraser of the sun

Adzebills, the Opportunists of New Zealand (art by Nobu Tamura, CC BY 3.0)

The glorious Mihirungs of Australia (art by @thewoodparable)

The Great Auk, the false-penguin of the north (photo by Mike Pennington, CC BY 3.0)

Chendytes, the giant marine ducks (art by Stanton Fink, CC BY 2.5)

Talpanas, the reverse-platypus (art by @drawingwithdinosaurs)

the Du, the Demon Chicken (art by @franzanth)

The Giant Flores Stork, competitor of the Komodo Dragon (art by Gabriel Ugueto, CC BY 4.0)

the Giant Swan, attacker of dwarf elephants (art by @paleoart)

Carolina Parakeet, the only parrot native to North America (photo by Huub Veldhuijzen van Zanten/Naturalis Biodiversity Center, CC BY-SA 3.0)

and, of course, Titanis: One of the Last Terror Birds (art by @drawingwithdinosaurs)

there are more, of course, but this post is already too long

527 notes

·

View notes

Note

for the character thing: captain ahab!

Thank you kindly!!

How I feel about this character

He is EVERYTHING. Every single aspect of his character is fascinating and dynamic and connected to a million other things. It's like trying to figure out how I feel about a storm. The trauma and torture of it all.

All the people I ship romantically with this character

Starbuck! I'm a Starhab devotee. They just have so much oomph. They would absolutely make each other way worse.

My non-romantic OTP for this character

I mean. The titular whale also therapy

My unpopular opinion about this character

Actual Literary Icon Captain Ahab has had every opinion ever written about him, so I'll just say he deserves to strike the sun if it insults him. As a treat.

One thing I wish would happen / had happened with this character in canon.

THAT HE TURNED THAT SHIP AROUND. Ahab living his life would have been infinitely harder for him than kicking the bucket (and kicking his crew's buckets) but imagine the character development! Imagine him moving on. He was never meant to live and that's why he should have.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

So the Temeraire series doesn’t do the Pern-derived magic/telepathic bond thing, and it’s nice to have some variety on that count since the telepathy thing is pretty widespread. But there’s this passage in crucible of gold that’s like—

Wait, my thriftbooks order arrived, let me go grab the quote

Or, Temeraire thought, he might as easily have gone alone--more easily, in fact; he had to carry Forthing cupped in his talons, and it was not at all convenient to always be looking to make sure he had not dropped out; Temeraire was not aware of him in quite the same way as of Laurence.

(Emphasis mine)

And this combined with the number of times it’s mentioned that (Russians aside) aviators just don’t seem to be capable of fearing their own dragons (and not just aviators who raised the dragons from the egg—it’s the same with inherited dragons) indicates to me that there’s something really interesting psychologically/biologically going on “under the hood,” there, so to speak.

And maybe this is just me and all those anthropology classes I took in college but that actually makes a lot of sense?

The historical record in the series dates the intentional breeding of dragons to a couple thousand years in the past, in china, but there’s a lot of evidence that there’s been a looser symbiotic relationship between humans and dragons a lot longer than that. Namely the domesticated elephants and the dragons in the Americas being the same species and of the same attitudes towards humans as dragons in Eurasia. So that’s likely at least 20 thousand years of symbiosis/mutual domestication, (if we assume they migrated together, which I do because it’s the simplest explanation) and it could well be much longer than that. That’s a long ass time. Like. The spread of IRL lactase persistence took less time than this.

And much like the benefits of being able to drink milk as an adult, the benefits of mutualism with an intelligent dinosaur-sized flying predator would absolutely have selective pressure on human populations. That’s just a given. I would talk about early hominins being third-tier scavengers here and Pleistocene megafauna and the canonical prevention of malaria via dragon proximity as compared to sickle cell anemia, but nobody wants me to regurgitate my entire biological anthropology 215 class in a tumblr post. Just trust me on this one.

Basically, the entire human species in the Temeraire universe will have been under a lot of positive selective pressure to be good symbiosis buddies to the dragons, so it’s no wonder aviator attachment is so intense.

This is likewise true for the dragons. A lot can be put down to intentional breeding in the last couple thousand years, but the foundation of dragons being prosocial with humans would have to be laid before then. Humans have domesticated predators IRL, but dragons are like 2-3 orders of magnitude larger than wolves and it took a long time to get dogs. The romans wouldn’t have had any luck if the dragons weren’t already partially on board. My theory is that this would have started way back. Australopithecus times, way back, because— [Anth 215 sneaks up behind me whilst the jaws theme plays] ANYWAY there’s a few benefits I can guess at for dragons having assistance hunting from small bands of persistence predators on occasion. I also think this would have intensified post-Pleistocene as the megafauna that would have been the dragons’ main prey went extinct and eventually agriculture would be the only way to replace— [Jaws theme intensifies] JUST TRUST ME BRO.

All this to say that humans being able to very quickly lose all instinctive fear of the dinosaur-sized flying predators they spend their time around and said predators developing not only attachment to humans but particular awareness of their humans specifically so as to prevent any possible accidental harm makes a lot of sense from an evolutionary biology perspective. It’s evidence of the same mutualistic relationship biologically shaping both species across the broader time spans that the series hints at.

#Temeraire#the kitten rambles#idk I just think it’s interesting that there’s more going on than the history the characters know#and it makes sense the characters wouldn’t think about this#because the time period in the series is about 35 years pre-theory of evolution by natural selection#'hey chi what are you doing with your Sunday night?’#I’m writing a speculative evolutionary biology essay about a fantasy novel WHAT ELSE WOULD ONE DO ON A SUNDAY EVENING

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you like Clangen and Sabertoothed cats? Great, me too!

My name is Pav and this is my clangen blog!

<Start reading here>

Important Things

🧓 Im a '99 bby so please don't DM if you're a minor (actually would prefer no unexpected DMs period tbh, im anxious)

⛏️ I work 12hrs 7 days, week on/week off, meaning I will completely vanish 50% of the time and there's nothing I can do about it

🦘 I'm also an Aussie, so my time zone is weird even when I'm not at work (So if I don't reply, im not ignoring u! ;v;-b )

❔️Asks and Anons are turned on! Please read the FAQ below before asking to avoid repeats c:

😻 I read all the tags and replies even if I don't reply. Tysm everyone saying nice things, it makes my day ;v;

😵💫 My focus changes like the weather lately, so while I'm Hoping I'll be able to keep this up, please don't get Life Or Death Invested c':

Tags

#mammothmoon -all chapters are tagged with this

#moon (1/2/3/etc) -each moon is tagged by number, and in-character asks from given moons

#mammothask -asks sent to me (will also tag who asks them)

#paleo stuff -anything where I'm nerding about paleo biology etc

#ooc -Pav updates about Pav!

FAQ

This will be added to as I get more asks and replies to go off!

How often do you post pages?

I try for at least once every 2 weeks, as I spend 50% of my life in the outback with no ability to draw!

Where/ when is Mammothclan set?

In late pleistocene North America, around 12ka ago, during the Younger Dryas!

What species are the cats?

They're Homotherium serum, a scimitar toothed cat.

How paleo accurate is this setting?

Relatively accurate? There's not going to be any species out of their time and place, but I'm not super bothered by, say, exact plant species and how realistic certain story aspects are.

Can I ask the characters' questions?

You can, but I can't promise to answer all of them!

Are we allowed to include characters as cameos/ draw fanart?

Yes definitely absolutely!!!!

You are also welcome to change them to regular cats if that fits better cx (please don't humanise them though, I find that specifically very uncanny)

What mode are you playing on Clangen/ what toggles?

Expanded mode, mass extinctions on, cheating on, "pregnancy ignores biology" off, unknown second parent pregnancies off (bc in my trial run every queen was constantly spawning kittens at lightspeed, no ty)

How far ahead are you from the pages you've drawn?

Currently 40moons ahead, cause I like playing the long game with foreshadowing >:3c

Where do you download Clangen?

Here!

Could you elaborate on/ explain content of (page/panel/speech bubble) that confused me?

Sure! If something is unclear, but it seems like it should be explained, please ask and I'll make sure to clarify c:

Can you tell me about (character backstory/spoilers/ aspect of lore not touched on in comic yet)?

No! I don't want to spoil those kinds of things, I'd rather they come up naturally in the comic than dump them under an ask.

I'm a firm believer that if it doesn't happen in text, it's not cannon.

#clangen#homotherium#mammothclan#pinned post#ive never done this before#but i think its a good idea bc ive Already gotten repeat asks cx#warrior cats#comic#warriors#webcomic

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Brief History of Flamingos

People wanted it so here it is, a brief rundown of flamingos throughout prehistory, which is essentially a brief summary of extinct flamingo species that I worked on for Wikipedia.

Because of this, I'll stick to the two main famillies, the Palaeolodidae ("swimming flamingos") and Phoenicopteridae (true flamingos) and leave aside the misc. early forms we don't know are actually related or not.

Palaelodidae

Palaelodids, occasionally referred to as "swimming flamingos" are an interesting and surprisingly long lasting group, containing 3 genera, 10 species and ranging from the Oligocene to the Pleistocene across all continents bar Africa and Antarctica.

The oldest palaelodid is Adelalopus hoogbutseliensis from the Early Oligocene of Belgium. Not much to be said other than that its name is an anagram of Palaelodus.

Palaelodus is the most widespread of the genera in the family, with the type species being Palaelodus ambiguus from the Oligocene and Miocene of Europe. I did actually make a whole post about the genus before here. Anyways, P. ambiguus is the best known species thanks to the ample material collected at Saint-Gérand-le-Puy, France. Remains were also found in Germany and maybe Brazil?

Brazil is interesting, because already by the Oligocene palaelodids were nearly cosmopolitan. Two other species, Palaelodus pledgei and Palaelodus wilsoni, have been recovered from the Oligocene to Miocene of Australia, half a world away from P. ambiguus. P. pledgei is the smallest known species of Palaelodus.

During the early Miocene we also get Palaelodus aotearoa, from New Zealand, and from the middle Miocene Palaelodus kurochkini from Mongolia. The later of the two may in fact be its own genus, but for now its deemed Palaelodus.

Generally, Palaelodus is less specialised than flamingos, though living in brackish waters and feeding on small aquatic insects, they didn't yet have the same suffisticated filter feeding bill as todays flamingos. Whats debated is how they moved. Some suggest wading, others diving and again others propose the idea that they may have been swimmers.

There is one more note on this group, which is that there are some remains assigned to P. wilsoni that appear to have been Pleistocene in age? Obviously this would be a massive deal, but it has also been suggested that this could be a new species given the time gap or a whole new genus. Still, palaelodid remains from the Pleistocene are still incredible.

Palaelodus by Alphinyx and Tom Simpson

The last member of the Palaelodidae is Megapaloelodus. Yes they misspelled Palaelodus in the genus name. The definition of this form is kinda vague and mostly based on size, which is why there's so many issues around Megapaloelodus goliath. You see it was initially described based on its size, but when larger remains of Megapaloelodus were found it was transferred to that genus. However, all other Megapaloelodus species are from the Americas, so thats kinda odd, although of course not a dealbreaker. Still, future research might change things up here.

While Megapaloelodus goliath was contemporary and found at the same place as Palaelodus ambiguus, all others are found in Miocene to Pliocene deposits of America.

Megapaloelodus connectens is the type species and known from the Miocene of South Dakota and California.

Megapaloelodus peiranoi may be the basalmost species and was discovered in Miocene deposits of Argentina.

Finally, we got Megapaloelodus opsigonus from Oregon and possibly Baja California. As this is the youngest species, from the Pliocene, its name means "born in a later age".

Megapaloelodus by Joschua Knüppe (with Argentavis) and Scott Reid

Which actually wraps up palaelodids. Yeah the majority of studies are focused on palaelodids, no surprise given its the only one with really good remains. But based on said animal, its a fascinating group.

This means we can move on to true flamingos, members of the family Phoenicopteridae. I hope you like that name btw, because goddamn "Phoenico" is an overused prefix for these animals to a ridiculous degree. Even I struggled keeping up.

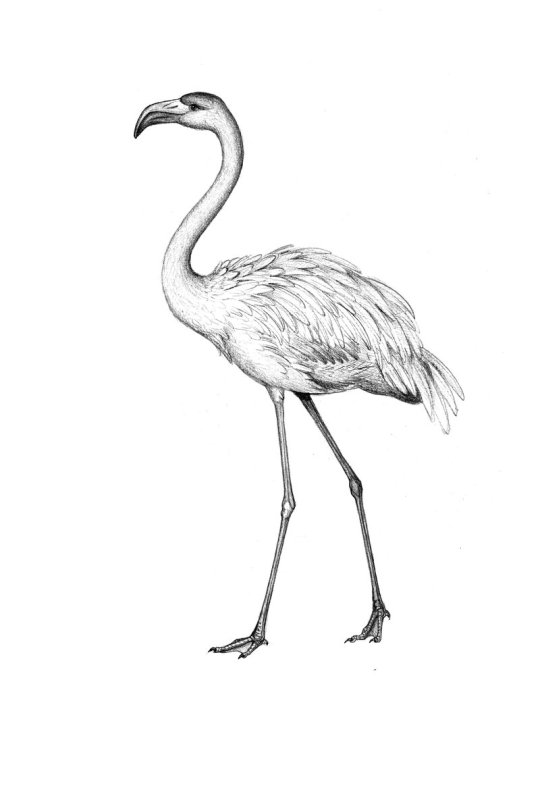

Just to set the stage, lets establish the modern flamingos, split into two to three genera. There is the Lesser Flamingo (Phoeniconaias minor), the only extant member of its genus and native to Africa and Asia. There are two species of Phoenicoparrus, the Andean and Jame's flamingos (Phoenicoparrus andinus and Phoenicoparrus jamesi respectively), both endemic to South America. And then there's the three species of Phoenicopterus. The incredibly whidespread Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus), the American Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) and the Chilean Flamingo (Phoenicopterus chilensis). As if the Greater and American flamingos didn't already have latin names way too similar, they were also synonyms for a while so thats fun when they get brought up in old papers.

Chart of living flamingos by Mr. Gharial

Anyways, lets reset to the Oligocene and do this semi-chronologically as before. And yes, Oligocene. Because contrary to what you might think, palaelodids, as we currently think of them as, aren't the ancestors to flamingos and more a really weird sister group that appeared from the same common ancestor aroundt he same time.

Thankfully, we get to start with something fun and not confusing, Harrisonavis croizeti. Another one I did actually cover in detail on Tumblr right here. The short of it is that Harrisonavis already bears the hallmarks of modern flamingos, possessing that classic curved bill and certainly doing some filter feeding already. And if you paid attention you might recognize where its from. Saint-Gérand-le-Puy, France. Yup, this guy coexisted with Palaelodus and Megapaloelodus. Must have been a fascinating place.

Harrisonavis and Palaelodus by Joschua Knüppe

Of course this being a well known form, we gotta follow it up with something bad. Elornis is, simply put, a mess. We aren't even super sure if its a flamingo or not and its history is convoluted. All we can say for sure is that it lived during the late Oligocene in France.

Like palaelodids, true flamingos seem to have dispersed rapidly, as our next entry managed to reach Australia by the late Oligocene. Phoeniconotius eyerensis, I repeat that one, PhoenicoNOTIUS (you see what I mean with things getting confusing?) is a genus from the Lake Eyre Basin of South Australia. It was a comparably robust animal, much more massive than other flamingos and perhaps more of a wader than a swimmer, staying away from deeper waters?

Same time same place we got Phoenicopterus novaehollandiae. PhoenicoPTERUS, as in the same genus as American and Greater flamingos. Now this guy sticks mostly to the same stuff as its relatives, thus differing clearly from Phoeniconotius.

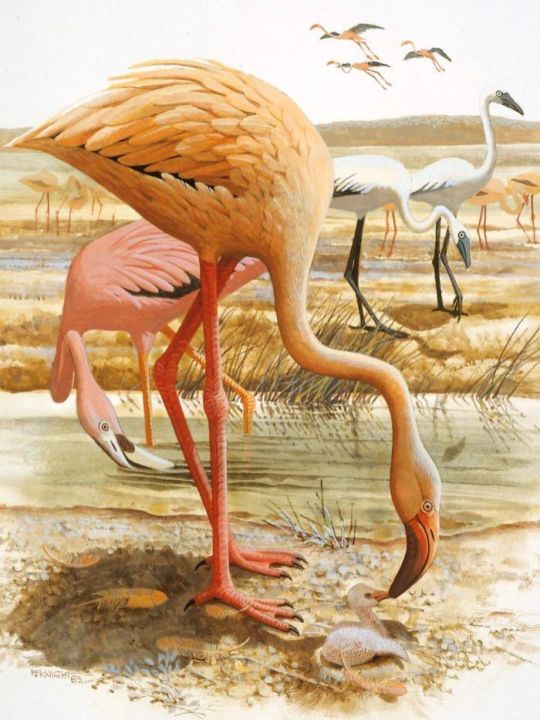

Phoeniconotius (foreground), Phoenicopterus novaehollandiae (?, middle) and palaeolids (background) by Frank Knight, Phoeniconotius by Anne Musser

We can now move into the Miocene. We get a brief break from Phoenico names courtesy of Leakeyornis aethiopicus from Kenya. Tho its not super well preserved, its among the few fossil flamingos with known skull remains, so thats gotta count for something.

Skeletal by me, art by Joschua Knüppe

Also during the Miocene, we get the appearance of the genus Phoeniconaias (PhoenicoNAIAS) thanks to Phoeniconaias siamensis. A small species, only slightly larger than today's Lesser Flamingo, its remains are exclusively known from the Mae Long Reservoir in northern Thailand.

Fossil material of P. siamensis alongside a Lesser Flamingo via เบิร์ดโบราณ - Ancient bird on Facebook

And already we find ourselves in the Pliocene. Oh how time flies. Lets wrap up known fossil species of Phoeniconaias then while we're at it. Phoeniconaias proeses is a species from Australia. Unlike our friend from Thailand, this one is actually smaller than its modern relative. It also coexisted with two other flamingos. Fossils from the region have been assigned to the Greater Flamingo and one other form we'll cover next.

Xenorhynchopsis. Our last truly original name. Xenorhynchopsis minor is the older of the two, Pliocene in age and the species I just alluded to earlier. The genus then went on to continue into the Pleistocene via Xenorhynchopsis tibialis. Neither is especially well known and both had been named by de Vis, who while no doubt an important contributor to Australian paleontology also had plenty of flaws I'll discuss soon with my next post on mekosuchines. Anyways, Xenorhynchopsis has a cool name, a confusing history (they were described as storks) and likely died out when the inland waterways of Australia dried up.

Its all downhill from here folks. It's all PhoenicoPTERUS from now on and none of them are especially good. Lets rewind to the Pliocene to cover them properly.

We got Phoenicopterus floridanus from the early Pliocene of, who guessed it, Florida. It may have also inhabited North Carolina.

Phoenicopterus stocki, or Stock's Flamingo, lived during the middle Pliocene in Mexico. Tho not well described, we got juvenile remains too, young individuals that were not yet capable of flight.

Finally we got two Pleistocene species.

Phoenicopterus minutus from California, specifically Lake Manix. Lake Manix also yielded fossils tentatively assigned to the other Pleistocene fossil species.

Phoenicopterus copei. While fossils of P. minutus are currently exclusive to Lake Manix, P. copei was more widespread, ranging from Mexico in the south to Oregon in the north as well as California in the west and Florida in the east. Where it coexisted with other flamingos, like P. minutus and American flamingos, it would have been the larger species.

And thats it. All the fossil flamingos of the Palaelodidae and Phoenicopteridae. Alas, bird fossils preserve notoriously poorly and though stuff like the ends of tibiatarsi and tarsometatarsi are diagnostic, they aren't super helpful to making them sound interesting to the average joe. So sorry if this whole post is a little dry in spots.

#palaelodidae#phoenicopteridae#palaelodus#megapaloelodus#adelolepus#leakeyornis#harrisonavis#elornis#phoenicopterus#phoenicoparrus#phoeniconaias#phoeniconotius#xenorhynchopsis#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#oligocene#miocene#pliocene#pleistocene#cenozoic#flamingo#phoenicopteriformes#long post

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

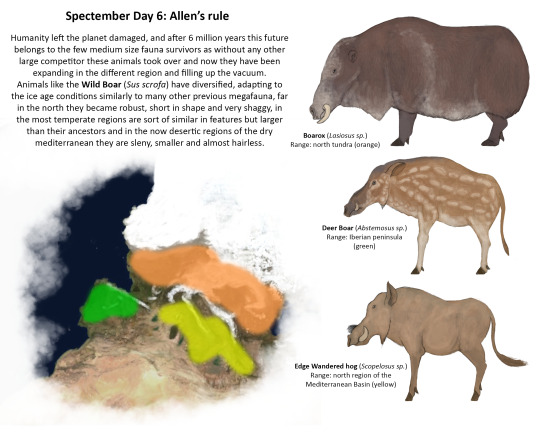

Spectember D6: Allen's Rule

6 million years since humans perished alongside the 50% of the biosphere, earth has recovered though not fully, there is just a handful of megafauna animals that are above a ton descendant of the animals that thrived in the post-human disaster, descendant of invasive and domesticated fauna in some places, others very resilient that were more used to the urbanization of their original terrains and the sudden climatic change for centuries, between these are the descendants of the wild hogs that endured the harsh habitable conditions until the end of humanity, and now with them gone they started to take the empty niches left by all the large herbivores of the Pleistocene and Holocene in Europe. Is not an easy time, the glacial age hasn’t ended yet, and now with the total disappearance of the Mediterranean Sea the once fertile south part of Europe is now more than scattered semi-arid regions.

Hogs have been always strong generalists but the strange conditions of three radically different environments have pushed them to change morphologically depending of the biomes each population managed to adapt, in the far north there are the smaller robust tundra species, the Boarox (Lasiosus sp.) has developed a large coat with a good chunk of fat that help them preserve the heat for the extreme wind storms on the strongest winters, they now resemble a muskox in shape, but unlike those they do not posses robust horns and a very tall head but a wide snout strong lips to tear the vegetation in the snow and large curved tusks protruding of each side help it to plow through the terrain.

Going now to the temperate regions there is something more familiar to the ancestral hogs, but taller, even more gracile and with a shorter coat, Deer Boar (Abstemosus sp.) is something like a suid trying to be a ruminant, has a divergent color pattern that helps them to blend with their environment which derives of the young individual coat, as well their heads are elongate, their ears longer and their snouts narrower than their north relatives, these are more browsers than grazers, a population is increasingly becoming isolated in the once Iberic peninsula.

And finally in the limits of the continent, in the edges of the now permanent dry basin of the Mediterranean there is another species, smaller than the temperate ones, lankier in shape this is the Edge Wandered hog (Scopelosus sp.), a species that resemble the long extinct African savannah species but that inhabit what was once a region covered by a sea. Their ears are larger than their previous relatives, more to accommodate for the heat, their legs are sort of slendy with considerable taller hooves, their coat is very short, with a muted and dull coloration more fitting for this environment, their heads are not as long as their relatives but wider, with short snouts but longer horns, these are more suited to dig for tubers and burrowing insects.

Each of these species are flexing the adaptive potential that suids are fully exploiting as they have claimed this recovering world, one that humanity left it devastated by a mass extinction.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

also. late quaternary extinction of a tree species in Eastern North America.

I've posted a little bit in the past about end-pleistocene megafauna extinctions, the overkill hypothesis, and the impact on "humans are the virus" type interpretations of ecology. This tree is the only documented end-Pleistocene plant extinction, which seems really striking, but this paper (from 1999) is like "yeah we haven't really studied it, and pollen deposits don't really allow for distinguishing plants on the species level, and most macrofossil sites have barely been analyzed."

I tried to do some research on end-pleistocene palynology in the USA and found this paper, which if anything gives a decent glimpse into what palynology does and doesn't allow us to analyze, and it is noted that "Nyssa, however, is distinctly entomophilous (Smiley Apiaries 2014), so just about any amount of its pollen in a sample suggests that the plants grew quite close to the site of deposition, where the discarded flowers accumulated. Because Nyssa is exclusively a freshwater entomophilous genus, the presence of its pollen in any significant quantity (>1%, F.J. Rich, personal observation) marks the site of a former freshwater wetland"

In other words, "Nyssa (blackgum) is insect pollinated, so its seriously weird that its pollen shows up in this fossil pollen sample, and would have to mean that there was a big grove of them with flowers falling to the ground right where the sample was collected."

Most of the species detected in this study are wind-pollinated species that are mega abundant and produce shit tons of airborne pollen, and they are identifiable down to either genus or family level. This means we can't say much about plants pollinated by insects, plants that were a small part of the total plants in the area, or plants that differed from modern ones only on species level.

Which means that it's misleading to say "there was only one End-Pleistocene plant extinction in USA" because we couldn't know that either way!

In fact the presence of plants like Torreya, Franklinia, and other "relict" plants along the Gulf Coast with ultra tiny ranges that likely used to be more widespread suggests that tons of plants could have gone extinct during the Last Glacial Maximum, since all it would take is a plant being 5% more intolerant to the glaciated climate than any of the numerous plants that got severely bottlenecked

It seems like the plants haven't gotten as much attention in research and that keeps being interpreted as "nah, there wasn't really an effect on the plants, only animals went extinct mostly" NO!!!!

187 notes

·

View notes