#Platanavis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Platanavis nana

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Platan Bird

First Described By: Nesov, 1992

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces

Status: Extinct

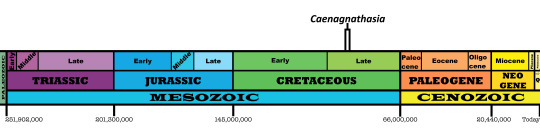

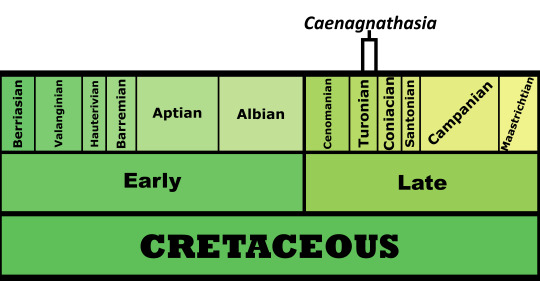

Time and Place: Between 92 and 90 million years ago, in the Turonian age of the Late Cretaceous

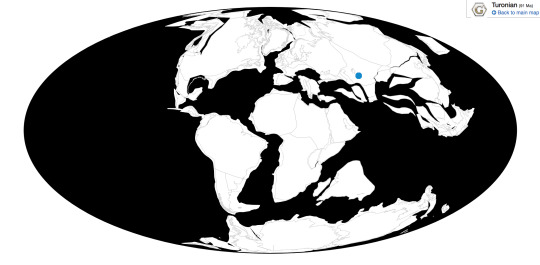

Platanavis is known from the Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan

Physical Description: Platanavis, for better or worse, is only known from a portion of the fused vertebrae above the hip - the synsacrum. As such, we don’t know much about it. We can seem to determine that it was a small proto-bird of some kind, and as such given the time of it being found it was probably not a modern bird (Neornithean). The size was small, and the synsacrum structure indicates that it was probably a short-tailed Avialan - somewhere around the split between Opposite Birds (Enantiornithine) and True Birds (Euornithine). So, what we can glean from that is that Platanavis was small, it was very bird-like, and it probably still had teeth in its mouth. It had a narrow, deep, and not-grooved hip. Beyond that, we cannot be sure.

Diet: Given we know very little of the morphology - especially mouth and teeth shape - of Platanavis, we can’t be sure of its diet; omnivore is probably the most likely thing we can say right now.

Behavior: Well, Platanavis could probably fly in some way, and it probably took care of its young and watched its eggs. Beyond that, we can’t really say much.

Ecosystem: The Bissekty Formation was a very diverse, “middle” Cretaceous seashore ecosystem, filled with brackish swamps and braided rivers along the coast. Unfortunately, the plant life of this environment is not known, but it wouldn’t be surprising if it was filled with horsetails and cycads and ferns, as well as some early flowering plants. It also would have been a very warm environment, being near the equator.

By Ripley Cook

This was an ecosystem filled with a variety of animals that were early versions of the iconic creatures of the Latest Cretaceous, especially in the dinosaurs. There was Turanoceratops, a forerunner of Ceratopsids like Triceratops and Styrcosaurus; Levnesovia, an Ornithopod very close to the soon-to-appear Hadrosaurids; Timurlengia, a transitional Tyrannosaur; Itemirus, one of the earliest known Velociraptorines (possibly, anyway); and Caenagnathasia, one of the earliest “advanced” Chickenparrots. There were loads of proto-birds, too, not just Platanavis - the “True Bird” Zhyraornis, and a gaggle of Opposite Birds including Abavornis, Catenoleimus, Explorornis, Incolornis, Kizylkumavis, Kuszholia, Lenesornis, and Sazavis. Troodontids like Urbacodon and Euronychodon were present, as was some sort of ornithomimosaur. There was also the ankylosaur Bissektipelta, and the ornithopods Gilmoreosaurus and Cionodon.

Non-Dinosaurs in the Bissekty included the huge pterosaur Azhdarcho, a variety of fish, a handful of turtles, some amphibians, and some sharks - many of which were adapted to brackish water that would have been common in the environment. There were also a very diverse selection of crocodylomorphs such as Zhyrasuchus, Zholsuchus, Kansajsuchus, and the earlier alligatoroid Tadzhikosuchus. There were also weird extinct relatives of Iguanas. In addition to all of this, there were a lot of early mammals, weird herbivorous Zhelestids and burrowing Asioryctitherians and insectivorous Zalambdalestids and almost-Marsupials and the rodent-like Cimolodonts. More research on this formation is sure to reveal more fascinating finds!

Other: Platanavis has a similar deep synsacrum to Gobipteryx, and given their similar range and Gobipteryx coming later, perhaps they’re closely related. This would make Platanavis an Enantiornithine, though of course that’s a very preliminary idea.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Averianov, A.O. 2002. An ankylosaurid (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) braincase from the Upper Cretaceous Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan. Bulletin de l'Institute Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre 72. 97–110. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Kurochkin, 2000. Mesozoic birds of Mongolia and the former USSR. in Benton, Shishkin, Unwin and Kurochkin, eds. The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. 533-559.

Mourer-Chauvire, 1989. Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution Information Newsletter. 3.

Nessov, 1992. Review of localities and remains of Mesozoic and Paleogene birds of the USSR and the description of new findings. Russkii Ornitologicheskii Zhurnal. 1(1), 7-50.

Redman, C.M., and L.R. Leighton. 2009. Multivariate faunal analysis of the Turonian Bissekty Formation: Variation in the degree of marine influence in temporally and spatially averaged fossil assemblages. PALAIOS 24. 18–26. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Sues, H.-D., and A. Averianov. 2009. Turanoceratops tardabilis—the first ceratopsid dinosaur from Asia. Naturwissenschaften 96. 645–652. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Sues, H-D., and A. Averianov. 2016. Ornithomimidae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bissekty Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Turonian) of Uzbekistan. Cretaceous Research 57. 90–110. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Weishampel, David B.; Peter Dodson, and Halszka (eds.) Osmólska. 2004. The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, 1–880. Berkeley: University of California Press. Accessed 2019-02-21.ISBN 0-520-24209-2

#Platanavis#Platanavis nana#Dinosaur#Bird#Avialan#Birds#Dinosaurs#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Omnivore#Theropod Thursday#Feathered Dinosaurs#factfile#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Platanavis nana

By Scott Reid on @drawingwithdinosaurs

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Platanavis nana

Name Meaning: Platan Bird

First Described: 1992

Described By: Nesov

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces

Platanavis is some sort of short-tailed Avialan (so either Euornithine or Enantiornithine) from the Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan, living in the Coniacian age of the Late Cretaceous, about 89 to 86 million years ago. It is known from a part of a hip bone. Somehow that makes it distinct given that it is narrow and not-grooved. Still, I can’t use that to talk about its ecology or life history. So. Life is filled with disappointments I suppose.

Sources:

http://theropoddatabase.com/Ornithothoraces.htm

http://www.paleofile.com/Dinosaurs/Aves/Platanavis.asp

Shout out goes to @dangerdino94!

#platanavis#platanavis nana#bird#dinosaur#palaeoblr#dangerdino94#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙#динозавр#dinosaurio

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caenagnathasia martinsoni

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Recent Jaw from Asia

First Described By: Currie et al., 1994

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Oviraptorosauria, Caenagnathoidea, Caenagnathidae, Elmisaurinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 92 and 90 million years ago, in the Turonian of the Late Cretaceous

Caenagnathasia is known from the Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan

Physical Description: Caenagnathasia was a Chickenparrot, and of the kind with particularly long and shallow jaws, with complex ridges inside. Caenagnathids also were more lightly built than Oviraptorids, with more hollow bones, more slender arms and long, gracile legs. They also weren’t very adapted for running as in other Oviraptorosaurs. Caenagnathasia, however, is not very well known. It’s known from a few jaws from a few individuals, as well as some vertebrae and a femur. We do know that Caenagnathasia is one of the smallest known oviraptorosaurs, and one of the smallest non-avian dinosaurs on the whole. It probably was about 0.61 meters long, and weighed 1.4 kilograms. Other than that, it probably would have resembled other oviraptorosaurs in general - fully feathered and bird like, with extensive wings, a tail fan, a beak, and long legs. It also was probably one of the more basal Caenagnathids.

Diet: Like other Oviraptorosaurs, Caenagnathasia was probably an omnivore.

Behavior: It is likely that Caenagnathasia behaved similarly to other Oviraptorosaurs, though we have no proof either way on that score. It probably would have taken care of its young, creating a large nest with eggs laid around the edge. Caenagnathasia would then sit in the center of the nest and use its wings to keep the eggs warm, like modern birds. These eggs were ovular and elongated, and potentially teal or turquoise in color. Caenagnathasia would have also been an an active, warm-blooded animal, using its wings to communicate with other members of the species and in sexual display. It also would have probably been opportunistic in terms of food eaten, feeding on whatever it could get its wings on.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: The Bissekty Formation was a diverse Middle Cretaceous seashore, filled with brackish swamps and braided rivers along the coast. It probably would have been filled with horsetails, cycads, ferns, and early flowering plants, though no plant fossils are known from the formation. There were a variety of animals in this ecosystem, especially many transitional forms to the iconic dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous. There was Turanoceratops, a forerunner of Ceratopsids like Triceratops; Levnesovia, an almost-hadrosaurid, as well as other ornithopods Gilmoreosaurus and Cionodon; Bissektipelta, an ankylosaur; Timurlengia, a transitional Tyrannosaurid; Itemirus, one of the earliest known possible Velociraptorines; the troodontids Urbacodon and Euronychodon, and a variety of early birds such as Platanavis, Zhyraornis, and opposite birds like Abavornis, Catenoleimus, Explorornis, Incolornis, Kizylkumavis, Kuszholia, Lenesornis, and Sazavis. There was also a probable Ornithomimosaur that has not yet been named.

Non-dinosaurs were also present, including the huge pterosaur Azhdarcho, many different kinds of fish, some turtles, amphibians, and even sharks that were adapted to the ample brackish water. There were a lot of crocodylomorphs, too, like Zhyrasuchus, Zholsuchus, Kansajsuchus, and an alligatoroid, Tadzhikosuchus. There were also a lot of weird Iguanas, and early mammals as well - herbivorous Zhelestids, burrowing Asiorhyctitherians, insectivorous Zalambdalestids, almost-marsupials, and rodent-like Cimolodonts. This is surely an exciting ecosystem for further research, as it showcases a transition from the Early Cretaceous, to the Late.

Other:

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Averianov, A.O. 2002. An ankylosaurid (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) braincase from the Upper Cretaceous Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan. Bulletin de l'Institute Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre 72. 97–110. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Currie, P.J.; Russell, D.A. (1988). "Osteology and relationships of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Saurischia, Theropoda) from the Judith River Oldman Formation of Alberta". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 25 (3): 972–986.

Currie, P.J.; Godfrey, S.J.; Nessov, L. (1994). "New caenagnathid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) specimens from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10–11): 2255–2272.

Kurochkin, 2000. Mesozoic birds of Mongolia and the former USSR. in Benton, Shishkin, Unwin and Kurochkin, eds. The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. 533-559.

Lamanna, M. C.; Sues, H. D.; Schachner, E. R.; Lyson, T. R. (2014). "A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America". PLoS ONE. 9 (3): e92022.

Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 152.

Redman, C.M., and L.R. Leighton. 2009. Multivariate faunal analysis of the Turonian Bissekty Formation: Variation in the degree of marine influence in temporally and spatially averaged fossil assemblages. PALAIOS 24. 18–26. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Sato, T., Y. Cheng, X. Wu, D. K. Zelenitsky, Y. Hsaiao. 2005. A pair of shelled eggs inside a female dinosaur. Science 308 (5720): 375.

Sues, H.-D., and A. Averianov. 2009. Turanoceratops tardabilis—the first ceratopsid dinosaur from Asia. Naturwissenschaften 96. 645–652. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Sues, H.-D.; Averianov, A. 2015. "New material of Caenagnathasia martinsoni (Dinosauria: Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Bissekty Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Turonian) of Uzbekistan". Cretaceous Research. 54: 50–59.

Sues, H-D., and A. Averianov. 2016. Ornithomimidae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bissekty Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Turonian) of Uzbekistan. Cretaceous Research 57. 90–110. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Weishampel, David B.; Peter Dodson, and Halszka (eds.) Osmólska. 2004. The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, 1–880. Berkeley: University of California Press. Accessed 2019-02-21.ISBN 0-520-24209-2

Wiemann, J., T.-R. Yang, P. N. Sander, M. Schneider, M. Engeser, S. Kath-Schorr, C. E. Müller, P. M. Sander. 2017. Dinosaur origin of egg color: oviraptors laid blue-green eggs. PeerJ 5: e3706.

#Caenagnathasia martinsoni#Caenagnathasia#Dinosaur#Oviraptorosaur#Chickenparrot#Cretaceous#Omnivore#Eurasia#Theropod Thursday#Bird#Birds#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Feathered Dinosaurs

146 notes

·

View notes

Note

that new post has me wondering-- exactly how much of a bone is needed to id a fresh new species? does it depend on the bone? and if the bone isn't identified, is it usually put in storage, or identified as closely to a known species as possible? and how exactly are entire bodies predicted from one tiny bone fragment?

The short answer: it depends.

The long answer: paleontologists usually justify identifyinga fossil as a new species if the fossil has characteristics that clearlydifferentiate it from similar fossils that are already known (especiallyfossils known from the same time and place as the new specimen). In some cases,a single bone might be distinctive enough to warrant the naming of a newspecies. However, as one might expect, it’s usually easier to figure out ifsomething is distinct from other, similar things if a more complete specimen isknown.

Of course, different researchers might have different ideasabout just how different something must be to be considered a new species. As aresult, it is not particularly rare for supposed “new species” to be deemedinvalid by later research, either because other researchers don’t consider thesupposed differences sufficient to justify a new species, or because evidenceis found that the original specimen forming the basis of the “new species”actually does belong to an already known species. This is especially true whendealing with extremely fragmentary specimens.

As for fossils that aren’t identified to species level: it’sworth pointing out that the identification of fossils may not happen until theyhave been transported to a collection, fully prepared from the surrounding rock,and studied by scientists. Oftentimes, for the purposes of organization, thespecimens are identified and recorded in terms of very broad taxonomic categories(e.g.: “dinosaur”, “crocodylomorph”, “pterosaur”, etc.), but it usually takesmore detailed study to find out whether they represent new species or not. Manymuseums that hold fossil collections have far more fossils than there areresearchers to study them. Paleontologists regularly discover new speciesby poking around in fossil collections and examining species that few if anyonehave properly looked at in the past.

Naturally, some fossils are so incomplete and nondescript thatthey cannot be narrowed down to any one species (old or new) even afterdetailed study. However, they may be important in other ways. For example, perhapsthey are the first known record of a broader group of organisms from a certaintime and place, or they preserve signs of disease or injuries. In these cases,paleontologists studying the specimens may still decide to write up a paperdescribing them. There are many paleontological papers discussing specimens thatcannot be named as any specific species.

And for your last question: restoring the complete body ofan organism from fragmentary fossils is always a necessarily speculativeendeavor. In the best-case scenario, the close relatives of the fragmentaryspecies are well known and can serve as the basis for most of the body. (Thisis obviously not a foolproof method, as closely related organisms can look verydifferent regardless, but from a scientific perspective it represents the mostlikely possibility.)

In the case of something like Platanavis, which can’t be assigned down to anything moretaxonomically specific than “ornithothoracine bird” (a very broad group of birds, including all modern species and thensome), uncertainty in its life appearance would be even higher. For the ADADrestoration, @drawingwithdinosaurs very skillfully and accurately rendered what we would expecta “generic” euornithine bird from the Cretaceous to look like. It is, of course,impossible for us to ascertain whether Platanavisreally looked like this, but it is a plausible depiction given the limitedmaterial that we have.

— @albertonykus, on behalf of A-Dinosaur-A-Day

50 notes

·

View notes