#Chickenparrot

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Trick or treat :D

Gigantoraptor!

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

HEY PALEOBLR

you know how oviraptorosaurs are often called "chickenparrots?"

well i recently learned abt the real life chickenparrot: the kili mooku chicken ("parrot beak/nose" in tamil)

i unfortunately dont know as much about them as i'd like since idk tamil well but from what little i understand, they're a show breed developed in tamil nadu (my state!) who are surprisngly health despite how odd they look! their breed standard also seems to include little to no wattles save a single round comb, so that one comb makes em look even more like oviraptorosaurs!

oviraptorosaur..........2!!!!!

#dinos#chooks#yeah youve probably heard me talking abt them like WEEKS back but#i realized oh man. i should make a post abt these#as you can tell i am very proud of these since theyre from my state afaik#like my tamil isnt great so i cant read much abt them as id like#but from what i can tell theyre like a show offshoot of aseels#aseels themselves come from a different state but i think this particular variant developed here#paleo#paleoblr#paleontology#dinosaurs#oviraptor#chickens#chickenblr#poultry#t

16K notes

·

View notes

Photo

i got ANZU are you kidding me

if i don’t get trike i’m suing

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's Nomingia then, if not a chickenparrot?

There is no question that Nomingia is an oviraptorosaur/chickenparrot. However, it might be a caenagnathid oviraptorosaur instead of an oviraptorid oviraptorosaur.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Trick or treat!!!

Caudipteryx!

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Trick or treat!

Khaan!

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

If I could go back in time and rename Oviraptor “Psittacogallus” (Parrot Chicken, cause ya know Chickenparrots), I would

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the record - and nobody asked this, but I want to write something fun instead of do work - if I were making Goodbye Volcano High, I wouldn't really change anything plot-wise or anything, but I would have every character be based on something from the same place specifically at the end of the Cretaceous

so, because everyone loves Hell Creek, I'd probably pick Hell Creek. as basic as that is

Fang & Naser I'd probably keep as the Hell Creek Azhdarchid? I'm also open to making them "Styginetta" (aka the only thing that would live through the extinction)

Trish can stay Triceratops!

Reed would be Archeroraptor. or maybe Styginetta. I'm debating

Naomi would be Edmontosaurus

Rosa would be Leptoceratops

Sage would maybe be Avisaurus, or Styginetta, or Anzu

Stella would be Ankylosaurus

Ms Roberts would be a Tyrannosaurus

LJ I'd probably make a Pachycephalosaurus

alternatively, we could have fun and go all out with the Nemegt

Fang & Naser would be Therizinosaurus or the Nemegt Azhdarchid

Trish would be Deinocheirus or Therizinosaurus or a Chickenparrot

Reed would be Teviornis or Adasaurus

Naomi would be Saurolophus

Rosa would be Gallimimus maybe? Or Mononykus? Or a chickenparrot?

Sage would be Teviornis, or Brodavis, or Gurilynia?

Stella would be Tarchia or Saichania

Ms Roberts would be Tarbosaurus

LJ I'd probably make a chickenparrot of some kind (there are so many)

at least one person would be Deinocheirus, another would be Therizinosaurus, and another would be Teviornis. everything else is just what makes sense

honestly in both I'd probably exnay the pterosaurs and just do dinosaurs for my own sanity, as much as that'd piss off my pterosaur researcher friends

like I love the game, but man, I would have openly wept if they had stuck to one end-cretaceous ecosystem. like, we know what lived when and what lived with each other (... more or less...), I feel like more games should take advantage of that?

Immersive realism! In my dino-anthro game? It's possible!

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

SO MANY PEOPLE THINK PTEROSAURS ARE DINOSAURS

in that vein, LOTS of people are pissed that A is ahead of B because "A is a bird and B is a lizard" (I don't have the heart to tell them... yet)

everyone loves animal C and I feel very vindicated (that's Kulinda)

no one. not a single person. has correctly ID'd animal D. nyeheheheheheheheheheheheheh

people are convinced Deinonychus is a griffon

it really is feathered bird-type wings. that's the deciding factor. if it has hands its not a bird.

There is a noticeable minority of folks who insist that the important thing is No Teeth. somehow, J doesn't have many votes.

someone thinks a silesaurid is a theropod. I'm crying.

so many people think there's a correct answer and I'm. I'm so excited to write the explanation post where I say "there is not, in fact, a right answer". both because it'll be fun to validate everyone's answers, and also because the people who insist there is a right answer need to calm down.

I'm concerned about humanity's ability to read ("I didn't know there were pictures!" said the hundreth person who didn't read the introduction where I explicitly say there are pictures)

"aren't half of these dinosaurs" surprise, 8 out of 10 are dinosaurs and the 9th is a maybe!

pterosaurs are an affront to g-d

where you live 100% affects the results and people who live in places with ratites or other megafaunal birds (or who work with them frequently) are the most likely to vote for A

lots of people think beaks can't have teeth so that'll be a fun one to dispel

there are at least a few people who want to define bird as Archosauria and I admire their chutzpah

apparently when something is a bird it stops being a dinosaur *headdesk*

lots of people do not know that pterosaurs are bird-line archosaurs and I'm wondering where we went wrong there

apparently ornithomimosaurs are peacocks now

maybe we should go back to lumping bats with birds. sure, it's not evolutionarily correct, but like, apparently bird is more a function of movement (flight) than evolution

multiple people debated what to vote for with their family and/or friends and I'm honored

LOTS of people get thrown off by the visible hands in the chickenparrot image

there is at least one jackass who desperately wants me and other paleontologists to argue with them and we are ignoring them

the results would definitely be different if I had used different taxa and/or images

ah yes the two genders: bird and not-bird

we have a new word for people who limit birds to Avialae through Neornithes: Consbirbative. I will now counter with a new word for people who define bird anywhere between Avemetatarsalia and Theropoda: Libirbal

there are enough people who equate dinosaur and bird and I love them

apparently this is the proper use of the tumblr poll function

*opens up my notifications for the bird poll when I wake up like I’m unfurling the daily newspaper*

Anyone want some highlights?

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

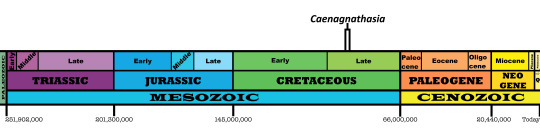

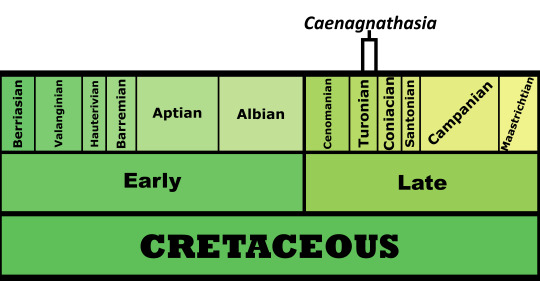

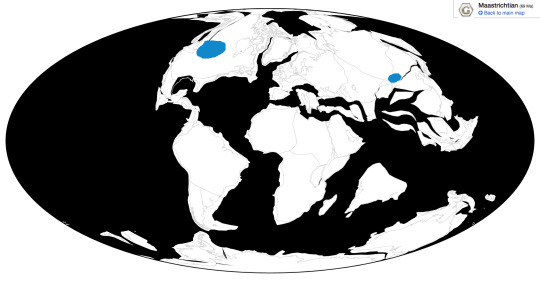

Caenagnathasia martinsoni

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Recent Jaw from Asia

First Described By: Currie et al., 1994

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Oviraptorosauria, Caenagnathoidea, Caenagnathidae, Elmisaurinae

Status: Extinct

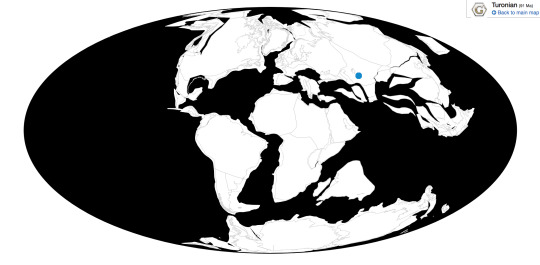

Time and Place: Between 92 and 90 million years ago, in the Turonian of the Late Cretaceous

Caenagnathasia is known from the Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan

Physical Description: Caenagnathasia was a Chickenparrot, and of the kind with particularly long and shallow jaws, with complex ridges inside. Caenagnathids also were more lightly built than Oviraptorids, with more hollow bones, more slender arms and long, gracile legs. They also weren’t very adapted for running as in other Oviraptorosaurs. Caenagnathasia, however, is not very well known. It’s known from a few jaws from a few individuals, as well as some vertebrae and a femur. We do know that Caenagnathasia is one of the smallest known oviraptorosaurs, and one of the smallest non-avian dinosaurs on the whole. It probably was about 0.61 meters long, and weighed 1.4 kilograms. Other than that, it probably would have resembled other oviraptorosaurs in general - fully feathered and bird like, with extensive wings, a tail fan, a beak, and long legs. It also was probably one of the more basal Caenagnathids.

Diet: Like other Oviraptorosaurs, Caenagnathasia was probably an omnivore.

Behavior: It is likely that Caenagnathasia behaved similarly to other Oviraptorosaurs, though we have no proof either way on that score. It probably would have taken care of its young, creating a large nest with eggs laid around the edge. Caenagnathasia would then sit in the center of the nest and use its wings to keep the eggs warm, like modern birds. These eggs were ovular and elongated, and potentially teal or turquoise in color. Caenagnathasia would have also been an an active, warm-blooded animal, using its wings to communicate with other members of the species and in sexual display. It also would have probably been opportunistic in terms of food eaten, feeding on whatever it could get its wings on.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: The Bissekty Formation was a diverse Middle Cretaceous seashore, filled with brackish swamps and braided rivers along the coast. It probably would have been filled with horsetails, cycads, ferns, and early flowering plants, though no plant fossils are known from the formation. There were a variety of animals in this ecosystem, especially many transitional forms to the iconic dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous. There was Turanoceratops, a forerunner of Ceratopsids like Triceratops; Levnesovia, an almost-hadrosaurid, as well as other ornithopods Gilmoreosaurus and Cionodon; Bissektipelta, an ankylosaur; Timurlengia, a transitional Tyrannosaurid; Itemirus, one of the earliest known possible Velociraptorines; the troodontids Urbacodon and Euronychodon, and a variety of early birds such as Platanavis, Zhyraornis, and opposite birds like Abavornis, Catenoleimus, Explorornis, Incolornis, Kizylkumavis, Kuszholia, Lenesornis, and Sazavis. There was also a probable Ornithomimosaur that has not yet been named.

Non-dinosaurs were also present, including the huge pterosaur Azhdarcho, many different kinds of fish, some turtles, amphibians, and even sharks that were adapted to the ample brackish water. There were a lot of crocodylomorphs, too, like Zhyrasuchus, Zholsuchus, Kansajsuchus, and an alligatoroid, Tadzhikosuchus. There were also a lot of weird Iguanas, and early mammals as well - herbivorous Zhelestids, burrowing Asiorhyctitherians, insectivorous Zalambdalestids, almost-marsupials, and rodent-like Cimolodonts. This is surely an exciting ecosystem for further research, as it showcases a transition from the Early Cretaceous, to the Late.

Other:

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Averianov, A.O. 2002. An ankylosaurid (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) braincase from the Upper Cretaceous Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan. Bulletin de l'Institute Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre 72. 97–110. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Currie, P.J.; Russell, D.A. (1988). "Osteology and relationships of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Saurischia, Theropoda) from the Judith River Oldman Formation of Alberta". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 25 (3): 972–986.

Currie, P.J.; Godfrey, S.J.; Nessov, L. (1994). "New caenagnathid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) specimens from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10–11): 2255–2272.

Kurochkin, 2000. Mesozoic birds of Mongolia and the former USSR. in Benton, Shishkin, Unwin and Kurochkin, eds. The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. 533-559.

Lamanna, M. C.; Sues, H. D.; Schachner, E. R.; Lyson, T. R. (2014). "A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America". PLoS ONE. 9 (3): e92022.

Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 152.

Redman, C.M., and L.R. Leighton. 2009. Multivariate faunal analysis of the Turonian Bissekty Formation: Variation in the degree of marine influence in temporally and spatially averaged fossil assemblages. PALAIOS 24. 18–26. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Sato, T., Y. Cheng, X. Wu, D. K. Zelenitsky, Y. Hsaiao. 2005. A pair of shelled eggs inside a female dinosaur. Science 308 (5720): 375.

Sues, H.-D., and A. Averianov. 2009. Turanoceratops tardabilis—the first ceratopsid dinosaur from Asia. Naturwissenschaften 96. 645–652. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Sues, H.-D.; Averianov, A. 2015. "New material of Caenagnathasia martinsoni (Dinosauria: Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Bissekty Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Turonian) of Uzbekistan". Cretaceous Research. 54: 50–59.

Sues, H-D., and A. Averianov. 2016. Ornithomimidae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bissekty Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Turonian) of Uzbekistan. Cretaceous Research 57. 90–110. Accessed 2019-03-22.

Weishampel, David B.; Peter Dodson, and Halszka (eds.) Osmólska. 2004. The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, 1–880. Berkeley: University of California Press. Accessed 2019-02-21.ISBN 0-520-24209-2

Wiemann, J., T.-R. Yang, P. N. Sander, M. Schneider, M. Engeser, S. Kath-Schorr, C. E. Müller, P. M. Sander. 2017. Dinosaur origin of egg color: oviraptors laid blue-green eggs. PeerJ 5: e3706.

#Caenagnathasia martinsoni#Caenagnathasia#Dinosaur#Oviraptorosaur#Chickenparrot#Cretaceous#Omnivore#Eurasia#Theropod Thursday#Bird#Birds#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Feathered Dinosaurs

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is flashiest tailed birb group??? vote now on phones!!!

#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#poll#raptors#birds#I know dromaeosaurs will probably win but I can dream and hope right?#chickenparrots#anzu#velociraptor#stenonychosaurus#anchiornis#archaeopteryx#confuciusornis#yi

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

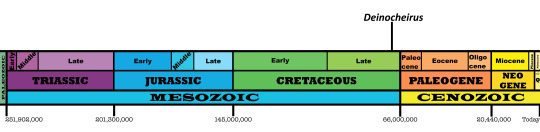

Deinocheirus mirificus

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Horrible Hand

First Described By: Osmólska & Roniewicz, 1970

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Ornithomimosauria, Ornithomimoidea, Deinocheiridae

Status: Extinct

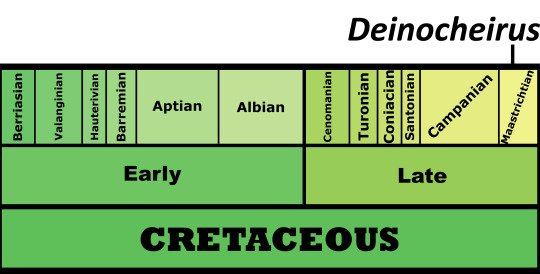

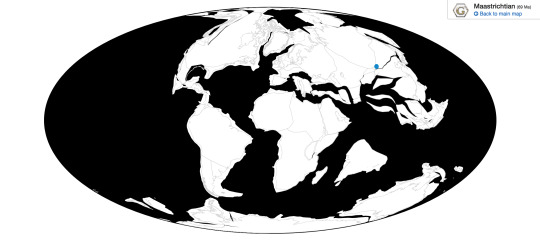

Time and Place: 70 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian of the Late Cretaceous

Deinocheirus is known from the Nemegt Formation of Ömnögovi, Mongolia

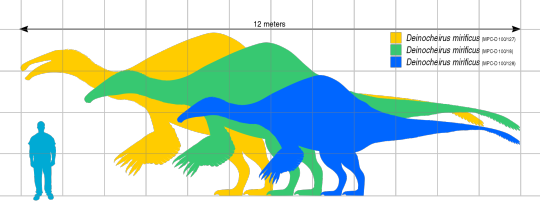

Physical Description: Deinocheirus is one of the absolute weirdest, fantastical, most surprising discoveries of the 2010s in paleontology, and the answer to a mystery older than most of the readers of this blog. Deinocheirus was originally known from two very long, distinctive arms - arms so long, that they could very easily engulf a person. In fact, many of the photographs of the fossil are of an individual standing in between the hands, in order to give scale to them. But these arms and hands gave very little in the way of information about what Deinocheirus looked like. Eventually, it was determined that Deinocheirus was an Ornithomimosaur - but the scale of the arms indicated it would be a ridiculously huge Ornithomimosaur.

By Slate Weasel, in the Public Domain

And then, luckily, more fossils were found of it. To be sure, it was a ridiculously large Ornithomimosaur - in fact, given the fact that it was an Ornithomimosaur, a group of distinctively feathered dinosaurs, it is almost certainly one of the largest feathered animals known to date - but it was More than that by a large margin. It was probably around 11 meters long, weighing up to 6.4 tonnes. It had some of the largest forelimbs known of any bipedal dinosaur - only rivaled by Therizinosaurs - and the arms in question are 2.4 meters long. Its skull, only one specimen of it having been found, is honestly weirdly duck-shaped. It was low and narrow, like other Ornithomimosaurs, but with a longer snout than its relatives. This snout was wide and shaped like a spatula - similar to the snouts of duck-billed dinosaurs and ducks alike. There weren’t any teeth in the jaws, which ended in a distinctive beak, and it was turned down, to make it look fairly massive and deep. When you get down to it, Deinocheirus had a ridiculously triangular head.

By Nix, CC BY-NC 4.0

As for the rest of the body, Deinocheirus had very long and narrow shoulder blades, connected to very pronounced and triangular shoulders. Weirdly enough, compared to the shoulders, Deinocheirus actually had smaller arms than its close relative Ornithomimus - ie, it had a smaller shoulder to arm ratio than its relatives. It had a U-shaped wishbone, which is fascinating since we don’t have the wishbone of other Ornithomimosaurs. Unlike other Ornithomimosaurs, it didn’t have pinched toe bones, so it wasn’t highly adapted for fast movement; it also had very blunt and broad foot claws like those of large Ornithischian dinosaurs. It may have been a bulky animal, but it was also quite narrow - with very tall, straight ribs. It had an S-curved neck, especially given the shape of the skull, which extended back into the oddly indeed shaped back. The spines on the back of Deinocheirus got progressively and progressively longer, until reaching lengths similar to those found on Spinosaurus - indicating that Deinocheirus had a sail or a hump, much like Spinosaurus did. There were interconnecting ligaments on the spines, strengthening it. That sail then lessened as it went down along the tail, until the tail had a very skinny appearance compared to the rest of the body. It had extremely lightweight air bones, through which the respiratory system ran. This also allowed it to be even more lightly built, which aided it in its large size. Interestingly enough, the tail ended in fused vertebrae, like those in Therizinosaurs, Oviraptors, and Birds - indicating it had a pygostyle!

By Michael B. H., CC BY-SA 3.0

As for feathers, it would have probably been covered in a layer of fluff all over the body. Fancy, pennaceous feathers would have been present on the arms and the end of the tail - in fact, a tail fan would have been attached to that pygostyle and used in display. It may have also had display feathers on the back of the head or even the legs. However, that being said, its large size may indicate a decrease in fluff so that it could stay cool - while it is still most likely that it had distinctive and extensive feathers as in its close relatives, fossil evidence is needed to determine its exact integument situation.

By Charles Nye

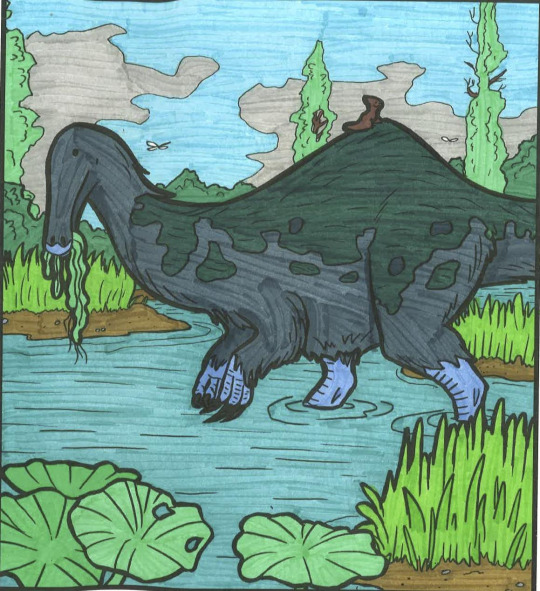

Diet: Deinocheirus was, distinctively, a large herbivore - specializing on water plants and other soft greens that could be shoveled up with that spoon beak.

By Meig Dickson & Diane Remic

Behavior: Deinocheirus probably spent a good amount of time foraging at or near the water, gathering up water vegetation with its spatulate bill. It also utilized gastroliths - stones that were swallowed to grind up that wet and mushy vegetation in the stomach. This was important and helpful, since it couldn’t do much grinding without teeth in its mouth. It did have a very long and large tongue, which allowed it to pull up extensive amounts of plant material up from the ground. It would use the blunt and short claws of its hands in order to dig up plants from the water - and to decrease resistance as it sucked them up from the swamps.

By Rebecca Groom

Deinocheirus wasn’t a fast animal - the short and stocky legs meant that it moved slowly through its environment, and used its large size to protect itself against predators instead. It grew extremely rapidly, too, reaching large size before sexual maturity. Sadly, its giant size means that it didn’t have a very large brain compared to its body size - in fact, the ratio in question was more similar to that of sauropods than other theropods. That beings aid, it was similar in shape to birds and troodontids and other birdie theropods, indicating that it still had a decent sense of smell - which is fascinating as it had a good respiratory system as well. As a warm-blooded animal, however, it would have been very active; and as a dinosaur, it probably took care of its young in nests. It is uncertain whether or not it would have lived in social groups, but it certainly wouldn’t have been particularly isolated as an herbivore.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: The Nemegt Formation was a wetland, filled with a wide variety of dinosaurs right before the end of the time of non-avian dinosaurs. The area was filled with large river channels, which created extensive shallow lakes, mudflats, and floodplains - like the modern Okavango Delta in Botswana. There were also thick coniferous forests surrounding the ecosystem, allowing for drier areas to be retreated to in addition to the swampy mess that was the bulk of the environment. Here, many plant-eaters specialized in feeding on water plants - in fact, I often joke that the Nemegt is the Land of Ducks. In addition to Deinocheirus, there were two other Ornithomimosaurs - Gallimimus and Anserimimus - both featuring duck-like beaks for feeding on water plants. Other ducks of the region include Saurolophus, which, as a duck-billed dinosaur, was especially adapted for feeding on soft plant material; and Teviornis, an early ACTUAL duck relative with the appropriate bill.

By Fraizer

This place also had other dinosaurs that weren’t ducks, of course. There was the large tyrannosaur, Tarbosaurus, which is known to have directly preyed upon Deinocheirus. There were troodontids too, like Tochisaurus, Zanabazar and Borogovia, which would have preyed upon the eggs and young of Gallimimus. There were a million different Oviraptorosaurs, making this also the ecosystem of the Chickenparrots - Avimimus, Elmisaurus, Conchoraptor, Nemegtomaia, Nomingia, and Rinchenia, were all present and feeding on the drier vegetation of the area. There was also the Hesperornithine Brodavis, one of the few freshwater species of Hesperornithines. There were other herbivores too, of course - Pachycephalosaurs like Homalocephale and Prenocephale, ankylosaurs such as Tarchia and Saichania, the titanosaur Nemegtosaurus, and the Therizinosaur Therizinosaurus - which probably all stuck to drier areas of the ecosystem than Deinocheirus. Tarbosaurus wasn’t the only Tyrannosaur, either - there was the smaller Alioramus which would have been more of a nuisance for baby Deinocheirus than the adults. And for other predators, there was the raptor Adasaurus, which may or may not have been a direct descendant of Velociraptor. As for non-dinosaurs, there was at least one Azdarchid, the small mammal Buginbaatar, and a variety of crocodilians that would have been non-negligible threats to young Deinocheirus. There were also plenty of turtles, which would have been a very noticeable part of the wider ecosystem.

By Scott Reid

Other: Deinocheirus is such a weird Ornithomimosaur, it gave its name to an entire group of them - these guys were slower than the Ornithomimids, and larger, but still had that general Ostrich-mimic shape. Instead of being lean and fast, they were large and slow. The discovery of the specimens of Deinocheirus that allowed us to actually learn what it looked like was a big one - since, prior to that point, Deinocheirus had been one of the most fascinating mysteries of dinosaur science, as all we had were two giant hands! Because of its large size, duck-like appearance, and above all, nightmare fodder in terms of past legend and current appearance, Deinocheirus has been fondly dubbed as Duck Satan for a makeshift common name.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Arbour, V. M., Currie, P. J. and Badamgarav, D. (2014), The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 172: 631–652.

Barret, P. M. 2005. The diet of Ostrich dinosaurs (Theropoda: Ornithomimosauria). Palaeontology 48 (2): 347 - 358.

Barsbold, R. (1983). "Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia [in Russian]." Trudy, Sovmestnaâ Sovetsko−Mongol’skaâ paleontologičeskaâ èkspediciâ, 19: 1–120.

Bell, P.R., Currie, P.J., Lee, Y.N. 2012. Tyrannosaur feeding traces on Deinocheirus (Theropoda: ?Ornithomimosauia) remains from the Nemegt Formation (Late Cretaceous), Mongolia. Cretaceous Research 37: 186 - 190.

Chinzorig, T., Kobayashi, Y., Tsogtbaatar, K., Currie, P.J., Takasaki, R., Tanaka, T., Iijima, M., Barsbold, R. 2017. Ornithomimosaurs from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia: manus morphological variation and diversity. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 91 - 100.

Claessens, L. P. A., and M. A. Loewen. 2016. A redescription of Ornithomimus velox Marsh, 1890 (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(1):e1034593:1-15

Fanti, F., Bell, P.R., Tighe, M., Milan, L.A., Dinelli, E. 2017. Geochemical fingerprinting as a tool for repatriating poached dinoaur fossils in Mongolia: A case study for the Nemegt Locality, Gobi Desert. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 51 - 64.

Fowler DW, Woodward HN, Freedman EA, Larson PL, Horner JR (2011) Reanalysis of “Raptorex kriegsteini”: A Juvenile Tyrannosaurid Dinosaur from Mongolia. PLoS ONE 6(6): e21376.

Funston, G. F.; Mendonca, S. E.; Currie, P. J.; Barsbold, R. (2017). "Oviraptorosaur anatomy, diversity and ecology in the Nemegt Basin". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Gradzinski, R., J. Kazmierczak, J. Lefeld. 1968. Geographical and geological data form the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 198: 33 - 82.

Holtz, T.R. 2014. Paleontology: Mystery of the horrible hands solved. Nature 515 (7526): 203 - 205.

Hurum, J. 2001. Lower jaw of Gallimimus bullatus. In Tanke, D. H., K. Carpenter, M. W. Skrepnick. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 34 - 41.

Jerzykiewicz, T., Russell, D.A. 1991. Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. Cretaceous Reserch 12 (4): 346 - 377.

Kobayashi, Y., Barsbold, R. 2006. Ornithomimids from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea 22 (1): 195 - 207.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. 1969. Fossils from the Gobi desert. Science Journal 5(1):32-38

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 5 - 136.

Kundrat, M., Lee, Y.N. First insights into the bone microstructure of Deinocheirus mirificus. 13th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists: 25.

Lauters, P., Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Escuille, F.O., Godefroit, P. 2014. The brain of Deinocheirus mirificus, a gigantic ornithomimosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstracts of Papers: 166.

Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Lee, H.J. 2013. New specimens of Deinocherus mirificus from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstracts of Papers: 161.

Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Lee, H.J., Godefroit, P., Escuillie, F.O., Chinzorig, T. 2014. Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus. Nature 515 (7526): 257 - 260.

Madsen, E. K. 2007. Beak morphology in extant birds with implications on beak morphology in Ornithomimids. Dek Matematisk-Naturvitenskapelige Fakultet - Thesis. 1 - 21.

Makovicky, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Currie, P.J. 2004. Ornithomimosauria. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmolska, H. eds. The Dinosauria. University of California Press.

McFeeters, B., M. J. Ryan, C. Schroder-Adams and T. M. Cullen. 2016. A new ornithomimid theropod from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36:e1221415:1-20

Middleton, K.M., Gatesy, S.M. 2000. Theropod forelimb design and evolution. Zoologicla Journal of the Linnean Society 128 (2): 160 - 172.

Mikhailov, K. E. 1991. Classification of fossil eggshells of amniotic vertebrates. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 36(2):193-238

Molnar, R.E. 2001. Theropod Paleopathology: a Literature Survey. In: Tanke, D.H., Carpenter, K. eds. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press.

Newbrey, M. G., Donald B. Brinkman, Dale A. Winkler, Elizabeth A. Freedman, Andrew G. Neuman, Denver W. Fowler and Holly N. Woodward (2013). "Teleost centrum and jaw elements from the Upper Cretaceous Nemegt Formation (Campanian-Maastrichtian) of Mongolia and a re-identification of the fish centrum found with the theropod Raptorex kreigsteini". In Gloria Arratia; Hans-Peter Schultze; Mark V. H. Wilson (eds.). Mesozoic Fishes 5 – Global Diversity and Evolution. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 291–303.

Norell, M. A., P. J. Makovicky, P. J. Currie. 2001. The Beaks of Ostrich Dinosaurs. Nature 412 (6850): 873 - 874.

Norell, M.A.; Makovicky, P.J.; Bever, G.S.; Balanoff, A.M.; Clark, J.M.; Barsbold, R.; Rowe, T. (2009). "A Review of the Mongolian Cretaceous Dinosaur Saurornithoides (Troodontidae: Theropoda)". American Museum Novitates. 3654: 63.

Novacek, M. 1996. Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs. Anchor. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. New York, New York.

Osmolska, H., Roniewicz, E. 1970. Deinocheiridae, a new family of theropod dinosaurs. Palaeontologica Polonica 21: 5 - 19.

Paul, G.S. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster.

Paul, G.S. 2012. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press.

Roy, B., Ryan, M.J., Currie, P.J., Koppelhus, E.B., Tsogtbaatar, K. 2018. Histological analysis of the gastralia of Deinocheirus mirificus from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. 6th Annual Meeting Canadian Society of Vertebate Paleontology.

Rozhdestvensky, A.K. 1970. Giant claws of enigmatic Mesozoic reptiles. Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal 1970 (1): 117 - 125.

Senter, P., Robins, J.H. 2012. Hip heights of the gigantic theropod dinosaurs Deinocheirus mirificus and Therizinosaurus cheloniformis, and implications for museum mounting and paleoeoclogy. Bulletin of the Gunma Museum of Natural History 14: 1 - 10.

Shuvalov, V.F. (2000). "The Cretaceous stratigraphy and palaeobiogeography of Mongolia". In Benton, Michael J.; Shishkin, Mikhail A.; Unwin, D.M.; Kurochkin, E.N. (eds.). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 256–278.

Takanobu Tsuihiji, Brian Andres, Patrick M. O'connor, Mahito Watabe, Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar & Buuvei Mainbayar (2017) Gigantic pterosaurian remains from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Watabe, M., S. Suzuki, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Tsubamoto, M. Saneyoshi. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2006. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Reasearch Bulletin 3:11 - 18.

Watanabe, A., Eugenia Leone Gold, M., Brusatte, S.L., Benson, R.B.J., Choiniere, J., Davidson, A., Norell, M.A., Claessens, L. 2015. Vertebral pneumaticity in the ornithomimosaur Archaeornithomimus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) revealed by computed tomography imaging and reappraisal of axial pneumaticity in ornithomimosuria. PLoS ONE 10 (12): e0145168.

Zelenitsky, D K., F. Therrien, G. M. Erickson, C. L. DeBuhr, Y. Kobayashi, D. A. Eberth, F. Hadfield. 2012. Feathered non-avian dinosaurs from North America provide insight into wing origins. Science 338 (6106): 510 - 514.

#Deinocheirus mirificus#Deinocheirus#Ornithomimosaur#Dinosaur#Duck Satan#Dinosaurs#Feathered Dinosaurs#Feathered Dinosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Mesozoic Monday#Cretaceous#Herbivore#Eurasia#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Meig, six of theses are among my favorite dinosaurs and you know it :P That said, voting for Gigantoraptor because chickenparrots need more love

Remember: Feathers and Scales are plastic traits, and not mutually exclusive! It seems very likely that most dinosaurs had some form of feathered integument somewhere, even if it is minor or for display only. Living birds, no matter the size, do not completely lose their feathers! And, in fact, many birds have both feathers and scales in the same tissue location! So, while many of these do not have direct evidence either way in terms of their integument, we can be fairly sure (based on ecology and proximity to modern birds) that these friends all had floof ^_^

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nemegtonykus citus

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Nemget Claw

First Described By: Lee et al., 2019

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Alvarezsauria, Alvarezsauroidea, Alvarezsauridae, Parvicursorinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 70 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian of the Late Cretaceous

Nemegtonykus is known from the Nemegt Formation of Ömnögovi, Mongolia

Physical Description: Nemegtonykus is known from a partial skeleton, showing a one meter long, lightly built bipedal animal. Like other Alvarezsaurs, it had a long tail and long, thin legs. We don’t know much about its arms or head, but it’s reasonable to suppose it - like other Alvarezsaurs - would have had single thumb claws, and no other digits on its arms; and a small head, ending in a very pointed snout. Parvicursorines, like Nemegtonykus, were of the small and lightly-built vein of Alvarezsaurs - and the apparently much more diverse group - rather than the heavily built Patagonykines. As a small birdie dinosaur, Nemegtonykus would have been covered in feathers, and possibly even had small wing-like feathers on its arms as display structures.

Diet: Alvarezsaur diets is a bit of question - one of the most popular hypotheses is that Alvarezsaurs are insectivores, however there is still a question and they may have been more generalist omnivores.

By José Carlos Cortés

Behavior: Nemegtonykus, as an Alvarezsaur, would have been extremely specialized in speed - its legs were well built for running, both to escape predators and potentially search for prey. It also would have been fairly good at hopping, able to leap out of the way in times of danger or distress. It is possible that the little claws of Nemegtonykus would have been useful in digging up insects or other sources of food out of hard to reach places. Nemegtonykus, like other Alvarezsaurs, would have been a very skittish and anxious animal, using its ability to run to escape danger as quickly as possible. The feathers would have been useful both in thermoregulation (given its small size) and display to other members of the species; and it probably took care of its young to some extent.

Ecosystem: Nemegtonykus lived in the famous and diverse Nemegt Formation, an environment filled to bursting with different kinds of dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures. This was a vast wetland, flooded with river channels that created extensive lakes, mudflats, and floodplains, much like the modern Okavango Delta in Botswana. This swamp field was surrounded by extensive coniferous forests, where the ground became somewhat drier. This was an area of animals highly specialized for their environment - especially creatures specialized for feeding on water plants, making them all various kinds of vaguely-duck-like animals. There was Duck Satan Deinocheirus, and the ornithomimosaurs Gallimimus and Answerimimus who also had duck-like bills for feeding on soft plants. There was the Hadrosaur (Duck-Billed Dinosaur) Saurolophus, which also fed on soft, mushy plants; and the actual early duck-like thing, Teviornis. In terms of non-duck dinosaurs, there was the large tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus and the smaller Alioramus; Troodontids like Tochisaurus, Zanabazar, and Borogovia; a million kind of chickenparrots like Avimimus, Elmisaurus, Conchoraptor, Nemegtomaia, Nomingia, and Rinchenia; the Hesperornithine Brodavis; Pachycephalosaurs like Homalocephale and Prenocephale; Ankylosaurs such as Tarchia and Saichania; the titanosaur Nemegtosaurus; the Therizinosaur Therizinosaurus; the raptor Adasaurus; and another Alvarezsaur - Mononykus. There was also an Azhdarchid pterosaur, the mammal Buginbaatar, and a variety of crocodilians and turtles.

By Scott Reid

Other: Nemegtonykus was found alongside a specimen of Mononykus, potentially indicating that different Alvarezsaurs potentially socialized with each other, or at least didn’t avoid each other within their shared habitats. This may also indicate a level of niche partitioning between different Alvarezsaurs.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Arbour, V. M., Currie, P. J. and Badamgarav, D. (2014), The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 172: 631–652.

Barsbold, R. (1983). “Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia [in Russian].” Trudy, Sovmestnaâ Sovetsko−Mongol’skaâ paleontologičeskaâ èkspediciâ, 19: 1–120.

Chinzorig, T., Kobayashi, Y., Tsogtbaatar, K., Currie, P.J., Takasaki, R., Tanaka, T., Iijima, M., Barsbold, R. 2017. Ornithomimosaurs from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia: manus morphological variation and diversity. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 91 - 100.

Choiniere, J.N.; Xu, X.; Clark, J.M.; Forster, C.A.; Guo, Y.; Han, F. (2010). "A basal alvarezsauroid theropod from the early Late Jurassic of Xinjiang, China". Science. 327 (5965): 571–574.

Fanti, F., Bell, P.R., Tighe, M., Milan, L.A., Dinelli, E. 2017. Geochemical fingerprinting as a tool for repatriating poached dinoaur fossils in Mongolia: A case study for the Nemegt Locality, Gobi Desert. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 51 - 64.

Fowler DW, Woodward HN, Freedman EA, Larson PL, Horner JR (2011) Reanalysis of “Raptorex kriegsteini”: A Juvenile Tyrannosaurid Dinosaur from Mongolia. PLoS ONE 6(6): e21376.

Funston, G. F.; Mendonca, S. E.; Currie, P. J.; Barsbold, R. (2017). “Oviraptorosaur anatomy, diversity and ecology in the Nemegt Basin”. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Gradzinski, R., J. Kazmierczak, J. Lefeld. 1968. Geographical and geological data form the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 198: 33 - 82.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. (2007). "Ornithomimosaurs and Alvarezsaurs". Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.

Holtz, T.R. 2014. Paleontology: Mystery of the horrible hands solved. Nature 515 (7526): 203 - 205.

Hurum, J. 2001. Lower jaw of Gallimimus bullatus. In Tanke, D. H., K. Carpenter, M. W. Skrepnick. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 34 - 41.

Jerzykiewicz, T., Russell, D.A. 1991. Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. Cretaceous Reserch 12 (4): 346 - 377.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. 1969. Fossils from the Gobi desert. Science Journal 5(1):32-38.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 5 - 136.

Kobayashi, Y., Barsbold, R. 2006. Ornithomimids from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea 22 (1): 195 - 207.

Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Lee, H.J. 2013. New specimens of Deinocherus mirificus from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstracts of Papers: 161.

Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Lee, H.J., Godefroit, P., Escuillie, F.O., Chinzorig, T. 2014. Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus. Nature 515 (7526): 257 - 260.

Lee, S., J.-Y. Park, Y.-N. Lee, S.-H. Kim, J. Lü, R. Barsbold, K. Tsogtbaatar. 2019. A New Alvarezsaurid Dinosaur from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. Scientific Reports 9: 15493.

Lü, JC; Xu, L; Chang, HL; Jia, SH; Zhang, JM; Gao, DS; Zhang, YY; Zhang, CJ; Ding, F (2018). "A new alvarezsaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation of Luanchuan, Henan Province, central China". China Geology. 1: 28–35.

Newbrey, M. G., Donald B. Brinkman, Dale A. Winkler, Elizabeth A. Freedman, Andrew G. Neuman, Denver W. Fowler and Holly N. Woodward (2013). “Teleost centrum and jaw elements from the Upper Cretaceous Nemegt Formation (Campanian-Maastrichtian) of Mongolia and a re-identification of the fish centrum found with the theropod Raptorex kreigsteini”. In Gloria Arratia; Hans-Peter Schultze; Mark V. H. Wilson (eds.). Mesozoic Fishes 5 – Global Diversity and Evolution. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 291–303.

Schweitzer, Mary Higby, Watt, J.A., Avci, R., Knapp, L., Chiappe, L, Norell, Mark A., Marshall, M. (1999). "Beta-Keratin Specific Immunological reactivity in Feather-Like Structures of the Cretaceous Alvarezsaurid, Shuvuuia deserti Journal of Experimental Biology (Mol Dev Evol) 255:146-157.

Shuvalov, V.F. (2000). “The Cretaceous stratigraphy and palaeobiogeography of Mongolia”. In Benton, Michael J.; Shishkin, Mikhail A.; Unwin, D.M.; Kurochkin, E.N. (eds.). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 256–278.

Takanobu Tsuihiji, Brian Andres, Patrick M. O'connor, Mahito Watabe, Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar & Buuvei Mainbayar (2017) Gigantic pterosaurian remains from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Turner, Alan H.; Pol, Diego; Clarke, Julia A; Erickson, Gregory M.; Norell, Mark (2007). "A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight". Science. 317 (5843): 1378–1381.

Watabe, M., S. Suzuki, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Tsubamoto, M. Saneyoshi. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2006. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Reasearch Bulletin 3:11 - 18.

Watanabe, A., Eugenia Leone Gold, M., Brusatte, S.L., Benson, R.B.J., Choiniere, J., Davidson, A., Norell, M.A., Claessens, L. 2015. Vertebral pneumaticity in the ornithomimosaur Archaeornithomimus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) revealed by computed tomography imaging and reappraisal of axial pneumaticity in ornithomimosuria. PLoS ONE 10 (12): e0145168.

Zelenitsky, D K., F. Therrien, G. M. Erickson, C. L. DeBuhr, Y. Kobayashi, D. A. Eberth, F. Hadfield. 2012. Feathered non-avian dinosaurs from North America provide insight into wing origins. Science 338 (6106): 510 - 514.

#Nemegtonykus#Nemegtonykus citus#Alvarezsaur#Dinosaur#Palaeoblr#Prehistoric Life#prehistory#paleontology#Factfile#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Omnivore#Theropod Thursday#Maniraptoran#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

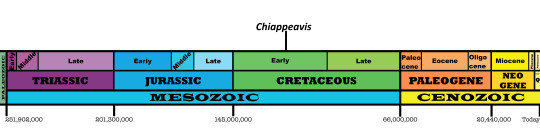

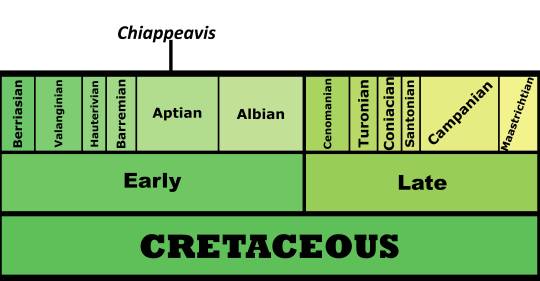

Chiappeavis magnapremaxillo

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Chiappe’s Bird

First Described By: O’Connor et al, 2016

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Enantiornithes, Cathayornithiformes

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 120 million years ago, in the Aptian age of the Early Cretaceous

Chiappeavis is known from the Jiufotang Formation of China, specifically in the Shangheshou Beds

Physical Description: Chiappeavis was an Opposite Bird, ie the group of bird-like dinosaurs that were extremely diverse and widespread during the Cretaceous period. Chiappeavis is known from a nearly complete skeleton, including some feather impressions. It was a fairly large bird, probably around 20 or so centimeters (though this is a very rough estimate). It had a small snout, with small pointed teeth inside of it, and a fairly large head. Its body was long, and it had large wings - good for more powerful flying as opposed to tighter maneuvering in between trees. Interestingly enough, Chiappeavis had a giant tail fan, which was not actually universal among Opposite BIrds as it is in modern birds. It also had fairly thick, strong feet.

Diet: It is probable that Chiappeavis fed mainly on arthropods and other hard invertebrates.

By Ripley Cook

Behavior: It is uncertain what the behavior of Chiappeavis was, given that we do not have extensive skeletons of this dinosaur. Still, it probably wouldn’t have flitted about the trees as much as birds with wings better built for maneuvering. The tail fan of Chiappeavis probably would have been extremely useful in sexual display, as well as other forms of communication - especially since it does not appear to have been very good at generating lift during flight (hence it not being widespread in other Opposite Birds). As such, it is more likely than not that Chiappeavis would have been fairly social, living in groups of multiple birds which communicated and recognized each other with feather displays. This, therefore, leads us to yet another likely hypothesis: that it took care of its young, at least to some extent. Beyond that, the behavior of Chiappeavis is a bit of a question - though it may have been able to dig out insects and other grubs with its strong feet, and then bit into the tough exteriors of these animals with its many needle-like teeth.

Ecosystem: The Jiufotang Formation was one of the Jehol Biota ecosystems, aka a group of extremely diverse and lush environments that preserved birdie dinosaurs of the Early Cretaceous with great detail. In that, Chiappeavis is one of many dinosaurs found in this location with extensive feather preservation. TheJiufotang Environment was a dense forest, surrounding an extensive number of lakes, and near volcanically active mountains. Still, it isn’t quite as well known as the earlier Yixian formation, and in fact doesn’t seem to have as many plants preserved to inform the exact environment and temperature. Still, it’s reasonable to suppose it may have also been a temperate ecosystem, like the earlier Yixian Formation, potentially even with snow.

By Jack Wood

In this environment, there were an extremely wide variety of animals. There was a decent diversity of fish, quite a few kinds of mammals, and the weird, unclassifiable Choristoderes were represented by Philydrosaurus, Ikechosaurus, and Liaoxisaurus. This ecosystem was lousy with pterosaurs, featuring a variety of Chaoynagopterids - like Chaoyangopterus itself, Eoazhdarcho, Jidapterus, and Shenzhoupterus; Pteranodonts like Guidraco, Ikrandraco, Liaoningopterus, Nurhachius, Liaoxipterus, and Linlongopterus; Tapejarids like “Huaxiapterus”, (probably) Nemicolopterus, and Sinopterus; and the weirdly late-surviving Anurognathid Vesperopterylus.

As for dinosaurs, there were many, and most were bird like! There was of course the Ankylosaur Chuanqilong, and the early Ceratopsian Psittacosaurus; there was also an unnamed titanosaur. There was a Tyrannosauroid, SInotyrannus, the Chickenparrot Similicaudipteryx, the raptor Microraptor, and tons of early Avialans like Confuciusornis, Dalianraptor, Jeholornis, Omnivoropteryx, Sapeornis, Shenshiornis, and Zhongjianornis. There were also “true” birds (ie, the line of dinosaurs that would evolve into those we see today) such as Bellulornis, Piscivoravis, Archaeorhynchus, Chaoyangia, Jianchangornis, Parahongshanornis, Schizooura, Songlingornis, Yanornis, and Yixianornis. However, the most diverse group of dinosaurs were the Opposite Birds, of which Chiappeavis was only one of many. There was Alethoalaornis, Boluochia, Bohaiornis, Cathayornis, Cuspirostrisornis, Dapingfangornis, Eocathayornis, Piscivorenantiornis, Pengornis, Gracilornis, Huoshanornis, Largirostrornis, Longchengornis, Longipteryx, Rapaxavis, Shangyang, Sinornis, and Xiangornis - just to name a few! As such the Jiufotange remains as a rich ecosystem in which to study the evolution of this fantastic group of Cretaceous dinosaurs.

By Scott Reid

Other: Chiappeavis is probably not its own thing - it is one of a number of Opposite Birds described without substantial evidence that it was a distinct genus and, indeed, many researchers consider them to be members of other genera. In this case, Chiappeavis is probably the same as Pengornis. Still, until it is officially lumped in, it must be treated as its own genus. It had a lot of similarities to Pengornis, regardless, indicating the two may belong to a larger clade of Opposite Birds. In short, Opposite Bird Phylogeny is kind of a mess, and needs a lot more intensive work than has currently been done.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Czerkas, S. A., D. Zhang, J. Li and Y. Li. 2002. Flying dromaeosaurs. In S. J. Czerkas (ed.), Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal 1. The Dinosaur Museum, Blanding, UT 96-126

Czerkas, S. A., and Q. Ji. 2002. A preliminary report on an omnivorous volant bird from northeast China. In S. J. Czerkas (ed.), Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal 1. The Dinosaur Museum, Blanding, UT 127-135

Dong, Z.-M., Y.-W. Sun, and S.-Y. Wu. 2003. On a new pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Chaoyang Basin, Western Liaoning, China. Global Geology 22:1-7

Dong, Z., and J. Lü. 2005. A new ctenochasmatid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning Province. Acta Geologica Sinica 79(2):164-167

Dong, L., Y. Wang, and S. E. Evans. 2017. A new lizard (Reptilia: Squamata) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China, with a taxonomic revision of Yabeinosaurus. Cretaceous Research

Evans, S. E., and Y. Wang. 2011. A gravid lizard from the Cretaceous of China and the early history of squamate viviparity. Naturwissenschaften 98:739-743

Evans, S. E., and Y. Wang. 2012. New material of the Early Cretaceous lizard Yabeinosaurus from China. Cretaceous Research 34:48-60

Gao, K.-Q., and R. C. Fox. 2005. A new choristodere (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning Province, CHina, and phylogenetic relationships of Monjurosuchidae. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society of London 145:427-444

Gao, K.-Q., D. T. Ksepka, L. Hou, Y. Duan, and D. Hu. 2007. Cranial morphology of an Early Cretaceous monjurosuchid (Reptilia: Diapsida) from Liaoning Province of China and evolution of the choristoderan palate. Historical Biology 19(3):215-224

Han, G., and J. Meng. 2016. A new spalacolestine mammal from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota and implications for the morphology, phylogeny, and palaeobiology of Laurasian ‘symmetrodontans’. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 178:343-380

He, H.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Zhou, Z.H.; Wang, F.; Boven, A.; Shi, G.H.; Zhu, R.X. (2004). "Timing of the Jiufotang Formation (Jehol Group) in Liaoning, northeastern China, and its implications". Geophysical Research Letters. 31 (13): 1709.

Hou, L., and J. Zhang. 1993. [A new fossil bird from Lower Cretaceous of Liaoning]. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 31(3):217-224

Hou, L. H. 1997. Mesozoic Birds of China.

Hu, D., L. Li, L. Hou and X. Xing. 2010. A new sapeornithid bird from China and its implication for early avian evolution. Acta Geologica Sinica 84(3):472-482

Hu, L. Li, L. Hou and D., X. Xu. 2011. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(1):154-161.

Hu, D.-Y., X. Xu, L. Hou and C. Sullivan. 2012. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China, and its implications for early avian evolution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32(3):639-645

Hu, Zhou and O'Connor, 2014. A subadult specimen of Pengornis and character evolution in Enantiornithes. Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 52(1), 77-97.

Hu, D., Y. Liu, J. Li, X. Xu, and L. Hou. 2015. Yuanjiawaornis viriosus, gen. et sp. nov., a large enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Cretaceous Research 55:210-219

Hu, O'Connor and Zhou, 2015. A new species of Pengornithidae (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous of China suggests a specialized scansorial habitat previously unknown in early birds. PLoS ONE. 10(6), e0126791.

Ji, Q., S.-a. Ji, and L.-j. Zhang. 2009. First large tyrannosauroid theropod from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota in northeastern China. Geological Bulletin of China 28(10):1369-1374

Li, J.-J., J.-C. Lü, and B.-K. Zhang. 2003. A new Lower Cretaceous sinopteroid pterosaur from western Liaoning, China. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 42(3):442-447

Li, L., Y. Duan, D. Hu, L. Wang, S. Cheng and L. Hou. 2006. New Eoenantiornithid Bird from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition) 80(1):38-41

Li, Q., J. A. Clarke, K.-Q. Gao, C.-F. Zhou, Q. Meng, D. Li, L. D'Alba and M. D. Shawkey. 2014. Melanosome evolution indicates a key physiological shift within feathered dinosaurs. Nature 507:350-353.

Li, Z., Z. Zhou, M. Wang and J. A. Clarke. 2014. A new specimen of large-bodied basal enantiornithine Bohaiornis from the Early Cretaceous of China and the inference of feeding ecology in Mesozoic birds. Journal of Paleontology 88(1):99-108

Lu, J.-C., Q.-J. Meng, B.-P. Wang, DLiu, C.-Z. Shen and Y.-G. Zhang. 2017. Short note on a new anurognathid pterosaur with evidence of perching behaviour from Jianchang of Liaoning Province, China. In D. W. E. Hone, M. P. Witton, D. M. Martill (eds.), Geological Society of London Special Publications 455:95-104.

Mortimer, M. 2016. Chiappeavis is just another Pengornis. Theropod Database Blog.

O'Connor and Chiappe, 2011. A revision of enantiornithine (Aves: Ornithothoraces) skull morphology. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 9(1), 135-157.

O'Connor, J. K., Y. -G. Zhang, L. M. Chiappe, Q. Meng, Q. Li and D. Liu. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33(1):1-12.

O'Connor, Zheng, Sullivan, Chuong, Wang, Li, Wang, Zhang and Zhou, 2015. Evolution and functional significance of derived sternal ossification patterns in ornithothoracine birds. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 28(8), 1550-1567.

O’Connor, J. K., X. Wang, X. Zheng, H. Hu, X. Zhang, Z. Hou. 2016. An Enantiornithine with a Fan-Shaped Tail, and the Evolution of the Rectricial Complex in Early Birds. Current Biology 26: 114 - 119.

O’Connor, J. K., X.-T. Zheng, H. Hu. X. Wang, Z.-H. Zhou, 2017. The morphology of Chiappeavis magnapremaxillo (Pengornithida: enantiornithes) and a comparison of aerodynamic function in Early Cretaceous avian tail fans. Vertebrata Palasiatica 55: 41 - 58.

Wang, X., T. Rodrigues, S. Jiang, X. Cheng, and A. W. A. Kellner. 2014. An Early Cretaceous pterosaur with an unusual mandibular crest from China and a potential novel feeding strategy. Scientific Reports 4(6329).

Wang, M., Z.-H. Zhou, and S. Zhou. 2016. A new basal ornithuromorph bird (Aves: Ornithothoraces) from the Early Cretaceous of China with implication for morphology of early Ornithuromorpha. 176(1):207-223.

Zhou, S., Z. Zhou, J. K. O’Connor. 2013. A new piscivorous ornithuromorph from the Jehol Biota. Historical Biology 26 (5): 608 - 618.

Zhou, Z.-h., F. Jin, and J.-y. Zhang. 1992. [Preliminary report on a Mesozoic bird from Liaoning, China]. Kexue Tongbao 1992(5):435-437

Zhou, Z. 1995. Discovery of a new enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 33(2):99-113

Zhou, X., and F. Zhang. 2001. Two new ornithurine birds from the Early Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Chinese Science Bulletin 46(15):1258-1264

Zhou, Z. 2002. A new and primitive enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22(1):49-57

Zhou, Z., and F. Zhang. 2002. A long-tailed, seed-eating bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Nature 418:405-409

Zhou, Z., and F. Zhang. 2002. Largest bird from the Early Cretaceous and its implications for the earliest avian ecological diversification. Naturwissenschaften 89(1):34-38

Zhou, X., and F. Zhang. 2003. Anatomy of the primitive bird Sapeornis chaoyangensis from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40:731-747

Zhou, Z., J. Clarke, F. Zhang and O. Wings. 2004. Gastroliths in Yanornis: an indication of the earliest radical diet-switching and gizzard plasticity in the lineage leading to living birds?. Naturwissenschaften 91(12):571-574

Zhou, Clarke and Zhang, 2008. Insight into diversity, body size and morphological evolution from the largest Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird. Journal of Anatomy. 212, 565-577.

Zhou, Z.-H., F. -C. Zhang, and Z. Li. 2009. A new basal ornithurine bird (Jianchangornis microdonta gen. et sp. nov.) from the Lower Cretaceous of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 10:299-310

Zhou, Z., F. Zhang, and Z. Li. 2010. A new Lower Cretaceous bird from China and tooth reduction in early avian evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277:219-227

#Chiappeavis magnapremaxillo#Chiappeavis#Opposite Bird#Bird#Dinosaur#Enantiornithine#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Birds#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Insectivore#Mesozoic Monday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

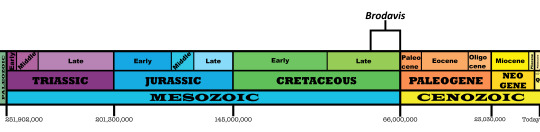

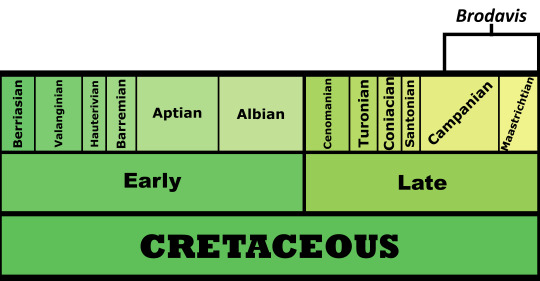

Brodavis

B. americanus by Jack Wood

Etymology: Brodkorb’s Bird

First Described By: Martin et al., 2012

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Hesperornithes

Referred Species: B. americanus, B. baileyi, B. mongoliensis, B. varneri

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 80 and 66 million years ago, from the Campanian to the Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous

Brodavis is known from a variety of habitats, most within the Western Interior Seaway of North America, with one in Asia: the Frenchman Formation, the Hell Creek Formation, the Pierre Shale Formation, and the Nemegt Formation.

Physical Description: Brodavis was a large bird, but a small dinosaur, reaching up to 90 centimeters in body length (though some species were half that size). It had a cylindrical body and long legs, good for propelling it through the water. It had a lightly built skeleton, though, so it wasn’t well adapted to diving - and may have even still been able to fly, though not particularly well. It had a long, skinny neck, and a small head ending in a long and pointed beak. This beak was full will small, pointy teeth for catching fish. It is unclear whether or not it had webbing between its toes, but this is definitely possible. The colors of Brodavis are poorly known, but it was certainly covered with feathers all over its body.

Diet: Brodavis would have primarily eaten fish and other aquatic life.

Behavior: Being a water-based creature, Brodavis spent most of its time near the water, swimming through along the surface and looking for food. Based on other Hesperornithines, it swam mostly with its feet, propelling them like living animals such as grebes today. Its wings, which were still probably functional, would have not been used in the water. Still, given the presence of flight in Brodavis, it probably would have been able to take off from the water to avoid danger - and back to the water to avoid more danger still, given the large predatory dinosaurs it shared habitats with. It would have then gone to the coasts to rest and rejoin other Brodavis, and would have also had nests there that they had to take care of. How social it was, or other specifics on behavior, are unknown at this time - though it would not be surprising if they lived in large family groups, given how common such behavior is in modern aquatic birds and the fact that it’s a fairly common genus of dinosaur.

B. varneri By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Being known from a wide variety of habitats, it’s nearly impossible to completely describe everything Brodavis ever lived with in one dinosaur article. That being said, Brodavis tended to live along the coast of major waterways (especially in freshwater areas), where it would spend most of its time underwater but go back to the shores to rest, mate, and take care of their young. Since Brodavis was found both in the Western Interior Seaway and the Seaway of Eastern Asia, it probably would have encountered a wide variety of other dinosaurs. In the Canadian Frenchman Formation, for example, it would have encountered the small herbivore Thescelosaurus, the large hadrosaur Edmontosaurus, the horned dinosaurs Triceratops and Torosaurus, the ostrich-like Ornithomimus, and the large predator Tyrannosaurus. In Hell Creek the companions of Brodavis were many, but included other dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus, Ornithomimus, Triceratops, Torosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Thescelosaurus like the Frenchman Formation - but also ankylosaurs like Denversaurus and Ankylosaurus, pachycephalosaurs like Sphaerotholus and Pachycephalosaurus, the small ceratopsian Leptoceratops, another ostrich-like dinosaur Struthiomimus, the chickenparrot Anzu, the raptor Acheroraptor, the opposite bird Avisaurus, and the modern bird Cimolopteryx - and more! In the Pierre Shale, Brodavis was accompanied by other Hesperornithines like Baptornis and Hesperornis. And, finally, in the Nemegt, Brodavis lived with another Hesperornithine Judinornis, the duck Teviornis, the ankylosaur Tarchia, the hadrosaur Saurolophus, the pachycephalosaurs Prenocephale and Homalocephale, the titanosaur Nemegtosaurus, the tyrannosaurs Alioramus and Tarbosaurus, Duck Satan Himself Deinocheirus, the ostrich-mimics Anserimimus and Gallimimus, the alvarezsaur Mononykus, the therizinosaur Therizinosaurus, the chickenparrots Avimimus, Elmisaurus, Nomingia, and Nemegtomaia; the raptor Adasaurus, and the troodontid Zanabazar. Given this wide variety of habitats and neighbors, Brodavis was probably able to live in freshwater habitats, unlike other hesperornithines, and it was decidedly a very adaptable dinosaur.

B. baileyi by Scott Reid

Other: Brodavis represents a unique group of Hesperornithines, though it’s possible the genus is overlumped, which would make the family that currently only has Brodavis in it (Brodavidae) actually informative.

Species Differences: These species differ mainly on where they’re from - B. americanus from the Frenchman Formation, B. baileyi from the Hell Creek Formation, B. mongoliensis from the Nemegt, and B. varneri from the Pierre Shale. As such, B. varneri is the oldest of the four, and may be its own genus. It is also the best known species.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Aotsuka, K. and Sato, T. (2016). Hesperornithiformes (Aves: Ornithurae) from the Upper Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Southern Manitoba, Canada. Cretaceous Research, (advance online publication).

Bakker, R. T., Sullivan, R. M., Porter, V., Larson, P. and Saulsbury, S. J. (2006). "Dracorex hogwartsia, n. gen., n. sp., a spiked, flat-headed pachycephalosaurid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota". in Lucas, S. G. and Sullivan, R. M., eds., Late Cretaceous vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 35, pp. 331–345.

Boyd, Clint A.; Brown, Caleb M.; Scheetz, Rodney D.; Clarke; Julia A. (2009). "Taxonomic revision of the basal neornithischian taxa Thescelosaurus and Bugenasaura". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 758–770.

Campione, N.E. and Evans, D.C. (2011). "Cranial Growth and Variation in Edmontosaurs (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae): Implications for Latest Cretaceous Megaherbivore Diversity in North America." PLoS ONE, 6(9): e25186.

Carpenter, K. (2003). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale)." High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437.

Estes, R.; Berberian, P. (1970). "Paleoecology of a late Cretaceous vertebrate community from Montana". Breviora. 343.

Glass, D.J., editor, 1997. Lexicon of Canadian Stratigraphy, vol. 4, Western Canada. Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, Calgary, Alberta, 1423.

Gradzinski, R., J. Kazmierczak, J. Lefeld. 1968. Geographical and geological data form the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 198: 33 - 82.

Henderson, M.D.; Peterson, J.E. (2006). "An azhdarchid pterosaur cervical vertebra from the Hell Creek Formation (Maastrichtian) of southeastern Montana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (1): 192–195

Jerzykiewicz, T., D. A. Russell. 1991. Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. Cretaceous Research 12 (4): 345 - 377.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 5 - 136.

Lerbekmo, J.F., Sweet, A.R. and St. Louis, R.M. 1987. The relationship between the iridium anomaly and palynofloral events at three Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary localities in western Canada. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 99:25-330.

Longrich, N. (2008). "A new, large ornithomimid from the Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada: Implications for the study of dissociated dinosaur remains". Palaeontology. 54 (1): 983–996.

Longrich, N.R., Tokaryk, T. and Field, D.J. (2011). "Mass extinction of birds at the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(37): 15253-15257.

Novacek, M. 1996. Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. New York, New York.

Martin, L. D., E. N. Kurochkin, T. T. Tokaryk. 2012. A new evolutionary lineage of diving birds from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Palaeoworld 21: 59 - 63.

Martyniuk, M. P. 2012. A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves; Vernon, New Jersey.

Pearson, D. A.; Schaefer, T.; Johnson, K. R.; Nichols, D. J.; Hunter, J. P. (2002). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Hell Creek Formation in Southwestern North Dakota and Northwestern South Dakota". In Hartman, John H.; Johnson, Kirk R.; Nichols, Douglas J. (eds.). The Hell Creek Formation and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the northern Great Plains: An integrated continental record of the end of the Cretaceous. Geological Society of America. pp. 145–167.

Tokaryk, T. 1986. Ceratopsian dinosaurs from the Frenchman Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Saskatchewan. Canadian Field-Naturalist 100:192–196.

Varricchio, D. J. 2001. Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Theropoda) dinosaurs from Montana. pp. 42–57 in D. H. Tanke and K. Carpenter (eds.), Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Watabe, M., S. Suzuki, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Tsubamoto, M. Saneyoshi. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2006. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Reasearch Bulletin 3:11 - 18.

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pages.

#Brodavis#Euornithine#Hesperornithine#Bird#Dinosaur#Theropod Thursday#Piscivore#North America#Eurasia#Cretaceous#Brodavis americanus#factfile#Brodavis baileyi#Brodavis mongoliensis#Brodavis varneri#Birds#Dinosaurs#prehistoric life#paleontology#prehistory#birblr#palaeoblr#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

182 notes

·

View notes