#Pier 36 San Francisco

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“San Francisco – P.M.S.S. Co.’s Wharf- Off for China and Japan” c. 1874. Illustrator unknown (from the collection of the National Parks Gallery).

Ships, Sheds and Wharves: Chinese and the Pacific Mail Steamship Co.

The earliest history of the Chinese in America remains intertwined with the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s sheds on San Francisco’s wharf and the broader narrative of maritime transportation, immigration, and economic development during the 19th century in California. Founded in 1848 as a response to the California Gold Rush, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (“PMSSC”) aimed to carry US mail on the Pacific leg of a transcontinental route from the east coast of the US to San Francisco on the west coast via Panama.

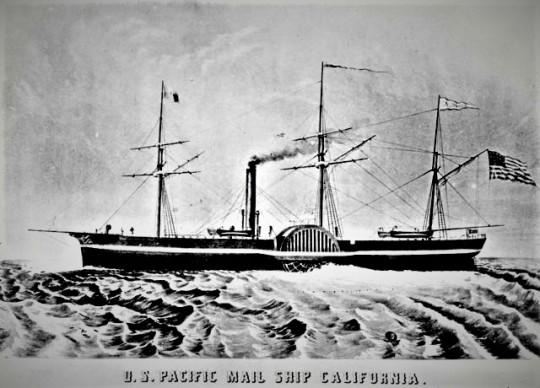

Illustration of the steamship SS California, the first ship of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Only a few passengers were on board when the ship left New York on October 6, 1848. By the time the ship reached its stop on the Panama’s Pacific coast, word had spread of the great new find of gold in California. Over 700 people tried to get passage on the ship in that harbor. The Pacific Mail agent managed to cram 365 people aboard the ship before it set sail for California. The ship and passengers reached San Francisco on February 28, 1849, where all but one member of the crew deserted the ship for the goldfields. The ship was lost in a wreck off the Peruvian coast in 1894. (Illustrator unknown, from the collection of the US National Postal Museum)

The discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada in 1849 produced a massive influx of people to California

from all over the world, including China. According to historian Thomas W. Chinn, “Hong Kong was the general rendezvous for departure to California. The emigrants usually stayed at dormitories provided by the passage brokers or at friends' and relatives' homes until the day of embarkation. The earliest ships between China and California were sailing vessels, some of which were owned by Chinese. . . . However, most of the ships in the early days bringing Chinese immigrants were American or British owned. At the time the shipping of Chinese to California was a very profitable business.”

The voyage in sailing vessels across the Pacific varied from 45 days to more than three months. Chinese passengers typically spent most of the voyage below decks in the overcrowded steerage. Conditions aboard the ships varied with the ship and shipmaster. In March 1852, 450 Chinese arrived in the American ship Robert Browne bound for San Francisco objected to the captain's order to cut off their queues as a hygienic measure. They rebelled, killed the captain and captured the ship. According to Chinn, “health conditions on the bark Libertad were so bad that when she sailed into San Francisco harbor in 1854, one hundred out of her five hundred Chinese passengers and the captain had died during the voyage from Hong Kong.”

In 1866, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (“PMSSC”) entered the cargo and passenger trade to and from the Orient. As the sole federal contract-carrier for US mail, the PMSSC became a key mover of goods and people and a key player in the growth of San Francisco, California.

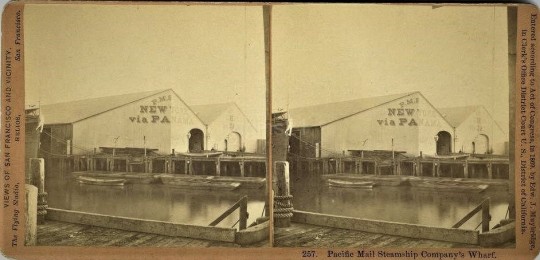

“257. Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s Wharf” c. 1869 -1871. Photo and stereoview by Eadweard J. Muybridge (from a private collection). The Pacific Mail’s wharf at the foot of Brannan Street in San Francisco at the approximate location of its old Pier 36. This was the first waterside view of the city for virtually every Chinese immigrant making landfall in San Francisco.

For the first six decades of the Chinese diaspora to the US, the sheds provided the first experience for every Chinese immigrant on California soil.

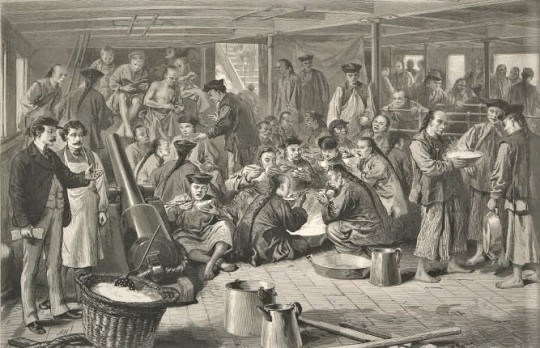

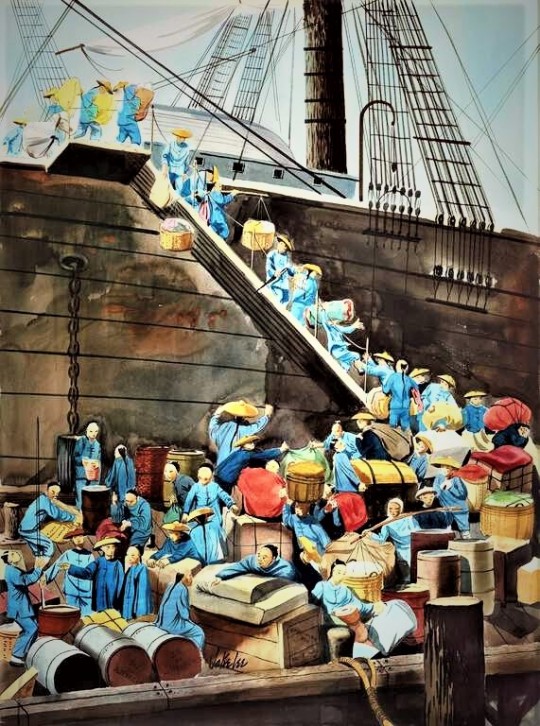

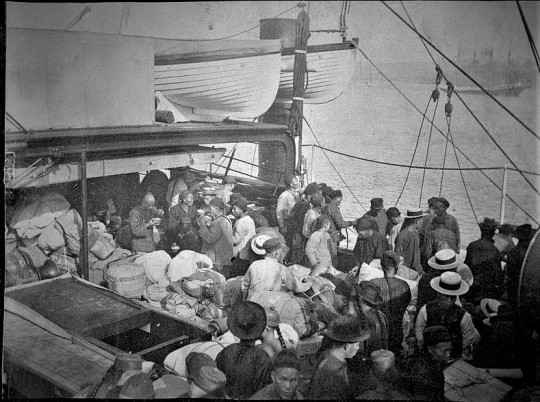

“Chinese Emigration to America,” no date. Illustrator unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). This illustration shows life aboard a Pacific Mail Steamship Co. ship making the passage from China to San Francisco.

Amidst the Gold Rush and burgeoning industries like mining, agriculture, and construction, Chinese immigrants from southern China flocked to California. The PMSSC’s sheds, located along San Francisco’s waterfront, played a crucial role in handling cargo, passengers, and immigrants who arrived via steamships. Serving as pivotal infrastructure, they provided storage space for goods, customs processing areas, and waiting areas for passengers.

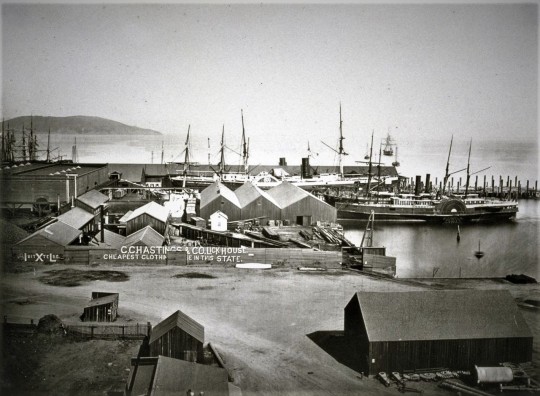

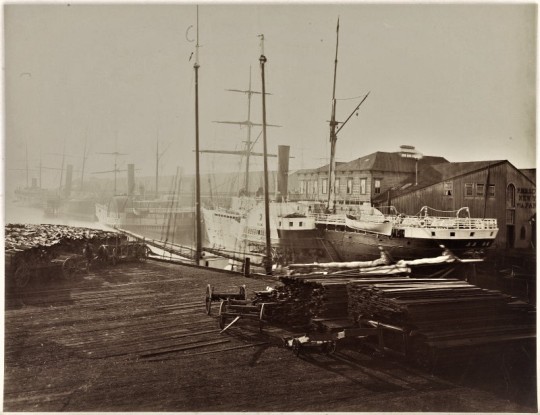

Pacific Mail Steamship Co. dock, c. 1864- 1872. Photograph by Carlton Watkins, probably derived from Watkins Mammoth Plate CEW 611. (from a private collection, the Roy D. Graves Pictorial Collection, Bancroft Library; and the San Francisco National Maritime Museum). In this elevated view east from Rincon Hill to the Pacific Mail dock, sidewheel steamer vessels identified by the SF National Maritime Museum as the SS Colorado (built in 1865 and scrapped in 1879), the steamer SS Senator at right (1865-1882), and various sailing ships are seen with Yerba Buena Island in the background. The Oriental Warehouse (built 1867 and still standing at 650 Delancey Street) is at left. The opensfhistory.org site identifies the three-part wooden structure at center as the Occidental Warehouse, used for grain storage, with blacksmith and boiler shops to the left. Ads for C.C. Hastings & Co. Clothing at Lick House can be seen on the fence.

Even as the Gold Rush waned, the PMSSC initiated in 1867 the first regularly scheduled trans-Pacific steamship service, connecting San Francisco with Hong Kong, Yokohama, and later, Shanghai. This route facilitated an influx of Japanese and Chinese immigrants, enriching California’s cultural diversity.

Pacific Mail Steamship Co. docks, c. 1871. Photograph by Carleton Watkins (from a private collection).

“Disembarking.” Painting by Jake Lee (from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). In this watercolor, one among a suite of paintings commissioned by Johnny Kan for his then-new Kan’s Restaurant on San Francisco’s Grant Avenue in Chinatown, artist Jake Lee depicted a stylized unloading of mostly male passengers at the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. wharf in San Francisco.

When a ship dropped anchor at the dock in San Francisco, the emigrants finally set foot on American soil. A journalist for the Atlantic Monthly in 1869 described the debarkation of 1,272 Chinese as follows:

"… a living stream of the blue coated men of Asia, bearing long bamboo poles across their shoulders, from which depend packages of bedding, marring, clothing, and things of which we know neither the names nor the uses, pours down the plank…. They appear to be of an average age of twenty-five years… and though somewhat less in stature than Caucasians, healthy, active and able bodied to a man. As they come down upon the wharf, they separate into messes or gangs of ten, twenty, or thirty each, being recognized through some to us incomprehensible free-masonry system of signs by the agents of the Six Companies as they come, are assigned places on the long broad shedded wharf [to await inspection by the customs officers]."

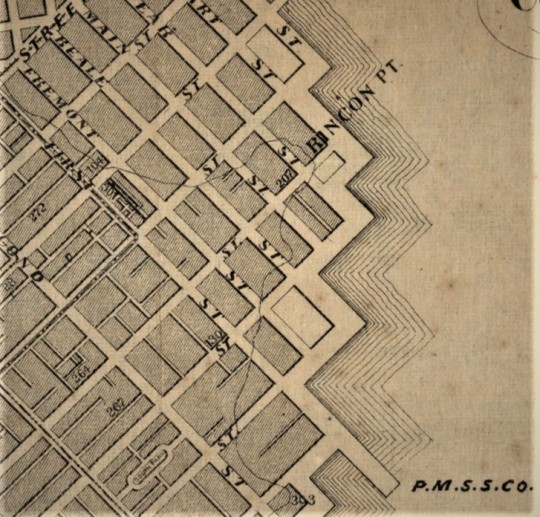

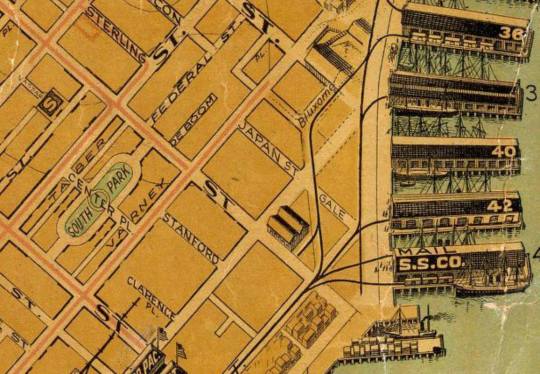

A detail from the "Bancroft's Official Guide Map of San Francisco" of 1873. The lower right corner of the image locates the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. pier at the foot of First Street (at Townsend) running in a southeasterly direction. According to local historian Garold Haynes, "that was before the seawall realignment of the waterfront in the late 1870s."

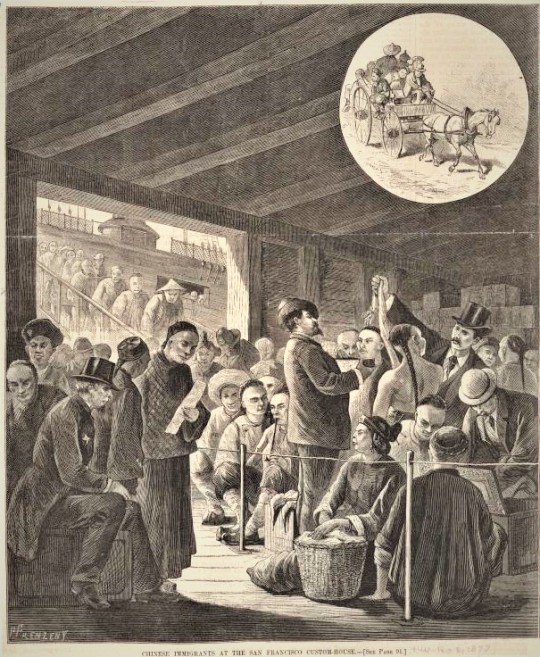

“Chinese Immigrants by The San Francisco Custom House” Harper’s Weekly, February 1877. Illustration by artist Paul Frenzeny (from the collection of the Library of Congress). Chinese immigrants wait for processing in the Pacific Mail Steamship Co.’s sheds while more arrivals from China disembark from the gangway seen in the background.

For many of the immigrants arriving on Pacific Mail steamships, the sheds served as the initial point of contact with the United States. Additionally, the sheds served as immigration processing areas, where Chinese immigrants underwent inspections and screenings. The sheds were a crowded and unsanitary place. Immigrants were often forced to wait for days in the sheds before they could be processed. They were also subjected to medical examinations and interrogations by immigration officials.

As the Atlantic Monthly writer described in 1869 described after each group passed through customs, “. . .They are turned out of the gates and hurried away toward the Chinese quarters of the city hv the agents of the Six Companies. Some go in wagons, more on foot, and the streets leading up that way arc lined with them, running in 'Indian file' and carrying their luggage suspended from the ends of the bamboo poles slung across their shoulders . . .”

In a political cartoon (c. 1888, based on the reference to the Republican Party presidential ticket of 1888 in the upper left corner of the image), Chinese immigrants stream off ships onto the wharves of the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. and the Canadian Pacific Steamship Co. and directly into the factories of San Francisco Chinatown and beyond. Illustrator unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

"New Arrivals." Date, location, and photographer unknown. The wagon on which the Chinese are riding, presumably having come directly from the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. wharf to San Francisco Chinatown, appears very similar to the 1877 configuration seen in the upper right corner of the preceding Harper's Weekly illustration.

The surge in Chinese immigration led to anti-Chinese sentiments, as reported in the illustrated magazines of the era. The arrival was often violent, as hoodlum elements would sometimes throw stones, potatoes and mud at the new immigrants. After the arrival in Chinatown, the newcomers were temporarily billeted in the dormitories of the Chinese district associations (citing Rev. Augustus W. Loomis, “The Chinese Six Companies,” Overland Monthly, os. v. 1 (1868), pp. 111-117).

“Hoodlums” Pelting Chinese Emigrants On Their Arrival At San Francisco” c. 1870s. Illustrator unknown (from a private collection). A rough sketch of the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. sheds appears in the background.

In San Francisco, local efforts to stop Chinese immigrants moved beyond the sheds and onto the arriving ships, which often became the focal points for Chinese litigants in the local and federal courts.

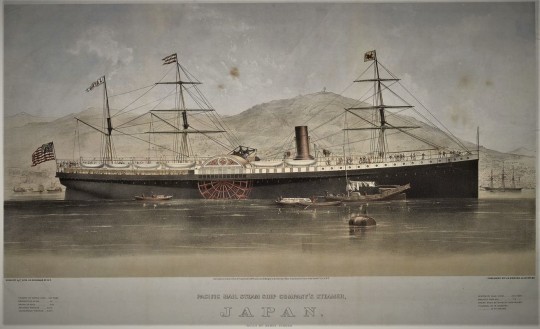

For example, in August of 1874, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s vessel Japan arrived in San Francisco carrying around 90 Chinese women. The Commissioner of Immigration boarded the ship and conducted interviews with about 50 to 60 of these women. From his inquiries, he concluded that 22 of them had been brought to San Francisco for “immoral purposes,” as reported by the Daily Alta California on August 6, 1874. When the Pacific Mail Steamship Company refused to provide the necessary bonds, the Commissioner instructed the ship’s master to keep the 22 women on board.

Pacific Mail Steam Ship Company’s Steamer, Japan, c. 1868. Print created by Endicott & Co. (New York, N.Y.), Menger, L. R., publisher (from the collection of The Huntington Library). Junks in the foreground, and, to the left in the background, Hong Kong’s Victoria Peak with semaphore at top appears in the background, center right. The SS Japan is flying the American flag from its stern, a Pacific Mail house-flag from the middle mast, and a pennant with the vessel’s name from the aft mast. A flag flying from the first mast appears to be a red dragon on a yellow field. Print includes vessel statistics and the name of the builder, Henry Steers.

Promptly, attorneys representing the detained women sought legal recourse by requesting a writ of habeas corpus from the state District Court in San Francisco. For two days, legal representatives from various parties engaged in debates over whether the Commissioner’s authority under the law was valid and whether the so-called “Chinese maidens” were indeed involved in prostitution. Reverend Mr. Gibson, who claimed expertise in this area, confidently asserted that Chinese prostitutes could be easily identified by their attire and behavior, likening the distinction to that between courtesans and respectable women in the city. He concluded that only half of the women were destined for prostitution. Ultimately, the District Court ruled that all the women should remain detained and ordered them to stay on the ship.

Shortly before the ship Japan was set to depart, the County Sheriff boarded and brought the 22 women ashore based on a writ of habeas corpus issued by the California Supreme Court. Two weeks later, Justice McKinstry, in a brief opinion on behalf of the court in Ex Parte Ah Fook, 49 Cal 402 (1874), affirmed the lower court’s decision, validating the Commissioner’s authority as a legitimate exercise of the state’s police power.

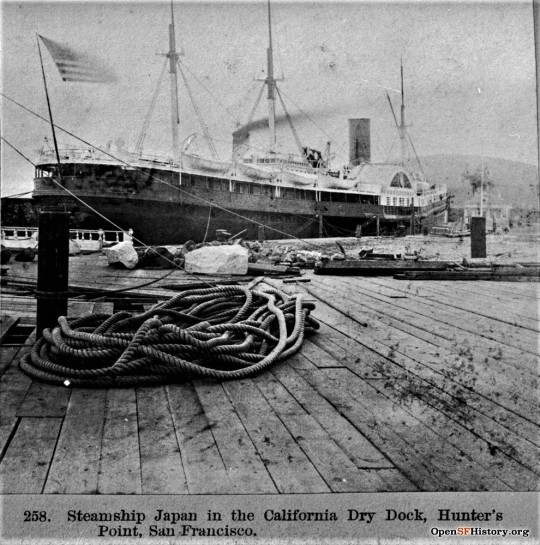

“258. Steamship Japan in California Dry Dock, Hunter’s Point, San Francisco”c. 1869. A side view of the steamship Japan of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company at the dry dock at Hunters Point. Photograph by Thomas Houseworth (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection). The ship would become the setting for a controversial habeas corpus case involving the entry of 22 Chinese women over the objections of state authorities in the case of Ex Parte Ah Fook, 49 Cal 402 (1874).

A third writ of habeas corpus presented the matter to the United States Circuit Court, presided over by Justice Stephen J. Field and Judge Ogden Hoffman. During the oral arguments, Justice Field made it clear that he wouldn’t dismiss constitutional arguments as easily as the state Supreme Court had, emphasizing the principle of equal treatment for citizens and non-citizens.

The Pacific Mail Steamship Co. derrick and coal yard in San Francisco, c. 1871. Photograph by Carleton Watkins (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

In the ruling, Justice Field discharged the petitioners, stating that California’s statute surpasses a state’s legitimate police power and violates the principle of “the right of self-defense.” He noted that the statute could exclude individuals who posed no immediate threat to the state. Judge Hoffman, in a concurring opinion, went further, suggesting that the states should have no control over immigration due to the exclusive nature of the commerce clause.

Although the Circuit Court decision released the Chinese women, while limiting the state’s power over Chinese entry, the Japan case reinvigorated California’s efforts to deter Chinese immigration. The influx of Chinese immigrants coupled with high unemployment in the late 1870s allowed Dennis Kearney of the Workingmen’s Party to target the Chinese as scapegoats. The “Chinese must go” movement gained traction, with both the Republican and Democratic parties adopting anti-Chinese stances.

The Pacific Mail Steamship Co.’s wharf in San Francisco. Photograph by Carleton Watkins (from the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco).

During the San Francisco Riot of 1877, the sandlot mob attacked the wharves of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, because this shipping line represented the primary mode of transportation for America-bound Chinese immigrants headed to California. Although the steamships were not burned, the wharves were partially wrecked. Rioters also burned the lumber and hay yards adjacent to the Pacific Mail wharves.

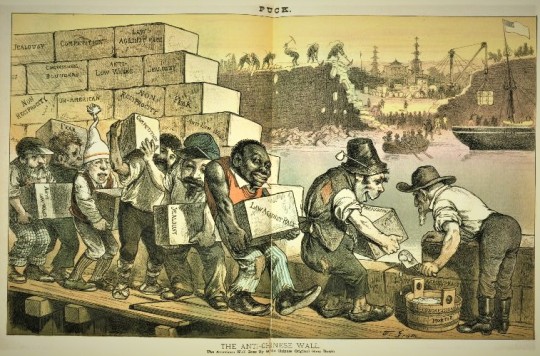

“The Anti-Chinese Wall – The American Wall Goes Up as the Chinese Original Goes Down.” Illustration by Friedrich Graetz in Puck of March 29, 1883 (v. 11, no. 264). The cartoon portrays a multi-ethnic coalition gathered on the wharf to halt Chinese immigration in the aftermath of the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in May 1882.

California was able to transfer its racial grievances and resentments to the national stage, culminating in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This marked a turning point in the history of Chinese immigration and had profound effects on the Chinese-American community. The Act severely restricted Chinese immigration to the United States.

The use the PMSSC’s sheds posed significant challenges to federal and state attempts to enforce the Exclusion Act (and its punitive extension in the Geary Act of 1892), against all Chinese, regardless of birth or immigration status.

As an article in the San Francisco Call of May 12, 1900, details, the chaotic scene at the Pacific Mall dock where Chinese immigrants disembarked from the ship Coptic was typical for that era. In the Coptic case, federal officials were observed allowing the landing of alleged "coolies" despite the spirit of the exclusion act, causing outrage. The detention shed, initially meant for temporary housing, had become a long-term residence for over 370 Chinese immigrants, generating substantial profit for the PMSSC. The maintenance of this facility posed several concerns, including violations of health regulations and potential disease outbreaks. The Call decried the authorities' negligence in enforcing the law and highlighted the role of a Chinese "ring" in facilitating fraudulent practices and illegal immigration. With multiple ships arriving with more immigrants, the newspaper called for investigation and reform.

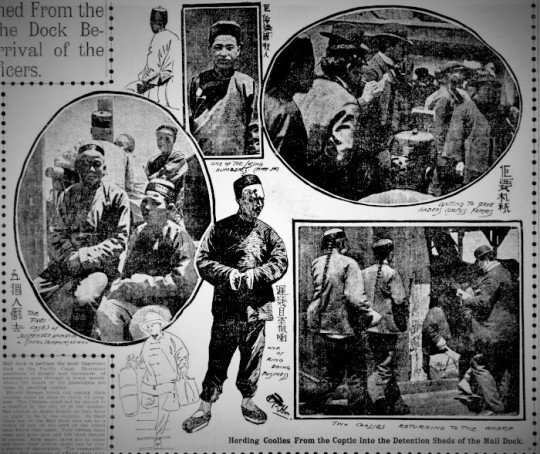

Headlines from the The Call of May 12, 1900, regarding the crowd of detained Chinese immigrants disembarked from the Pacific Mail ships Coptic and America Maru, the lack of security in the Pacific Mail sheds, and alleged immigration fraud.

Illustrations and photographs from the San Francisco Call of May 12, 1900, for its report about the crowd of detained Chinese immigrants disembarked from the Pacific Mail ships Coptic and America Maru, the lack of security in the Pacific Mail sheds, and alleged immigration fraud.

For Chinese and other immigrants and travelers from Asia, the transpacific journey, and even entering San Francisco Bay itself, posed hazards. The dangers were never more evident than in the case of the SS City of Rio de Janeiro. Launched in 1878, this steamship had been an essential component of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company's fleet. Its routes connected pivotal locations such as San Francisco, Honolulu, Yokohama, Japan, and Hong Kong, and the ship had played a role in America's expansion into the Far East and the Pacific in the aftermath of the Civil War and during the Spanish American War.

“A Thousand Boys in Blue S.S. Rio de Janeiro bound for Manila” copyright 1898. Published by M.H. Zahner (from the collection of the Robert Schwemmer Maritime Library). Built by John Roach & Son in 1878 at Chester, Pennsylvania, this vessel had served as a vital link between Asia and San Francisco, regularly transporting passengers and cargo. This stereograph shows its charter by the federal government for use as a military troop transport during the Spanish American War.

On the morning of February 22, 1901, the SS City of Rio de Janeiro commenced its approach to the Golden Gate and the entrance to San Francisco Bay. They had sailed with a crew that was mostly Chinese. History indicates that approximately 201 people were aboard the Rio de Janeiro, as follows: Cabin passengers 29; second cabin, 7; steerage (Chinese and Japanese), 68; white officers, 30; Chinese crewmen, 77. Of the Chinese crewmen, only two spoke English and Chinese. During the long voyage, the ship’s officer gave orders by using signs and signals. The ship’s equipment and lifeboat launching apparatus appeared to be in good working order and were capable of being lowered in less than five minutes.

Near the location of the future location of the Golden Gate Bridge, tragedy struck as the SS City of Rio de Janeiro. In the dense morning fog that obscured the surroundings, the ship collided with jagged rocks on the southern side of the strait, near Fort Point. The vessel’s non-watertight bulkheads led to rapid and unstoppable flooding. In a mere ten minutes, the SS City of Rio de Janeiro succumbed to the relentless forces of the sea.

The majority of the passengers, many of whom were Chinese and Japanese emigrants in steerage, were caught unaware in their cabins as the ship sank. The toll was staggering, with 128 lives lost out of the 210 souls on board. Of the 98 Asians reportedly on board the ill-fated ship, only 15 passengers were rescued, and 41 Chinese crewmen survived.

The SS City of Rio de Janeiro in Nagasaki, Japan, c. 1894. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park). The ill-fated ship, which transported passengers and cargo between Asia and San Francisco, sank seven years later after running into rocks near the present site of the Golden Gate Bridge. The never-salvaged shipwreck rests 287 feet underwater.

The sinking of the SS City of Rio de Janeiro represented the deadliest maritime disaster at the San Francisco Bay's entrance, forever etching its name in the annals of maritime history as the “Titanic of the Golden Gate,” drawing a sad parallel to another infamous shipwreck. Today, the case serves as a reminder of the unpredictable forces of nature and the inherent dangers of maritime travel to which thousands of Chinese immigrants and other Asian travelers subjected themselves to gain a better life in America.

"Chinese Passengers on Deck, 1900–15," enroute to Hawaii. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Hawaii State Archives). Chinese passengers, some eating from rice bowls, crowd the deck of a steamship. After the Exclusion Acts, the numbers of Chinese voyaging to the US had decreased sharply.

Despite reduced immigration due to the passage of successive exclusion acts in 1882 and 1892, the PMSSC's sheds remained operational, their purpose shifting from off-loading immigrants to facilitating trade and commerce between the east and west coasts of the US.

The Pacific Mail Steamship shed on the San Francisco waterfront at the turn of the century. Photograph attributed to Arnold Genthe. Located at the former pier 36, where Brannan Street runs into the Embarcadero, the immigration station was moved to Angel Island in 1910. Pier 36, the last of the docks at Brannan was torn down in 2012. In just one year, 1852, 25,000 Chinese entered California for the Gold Rush and other opportunities. Chinese America began here.

The convergence of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads in Utah in 1869, had started the process of eroding the Pacific Mail's profitability on the Panama-to-San Francisco route over the ensuing decades, eventually leading to the sale or redirection of many of its ships to other routes.

The Pacific Mail Steamship Co. offices on the southeast corner of Market and First streets in downtown San Francisco, c. 1896. Photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The landscape changed drastically in 1906, when a devastating earthquake and subsequent fire struck San Francisco, including the PMSSC’s wharf facilities. Although destroyed during 1906 disaster, the PMSSC’s sheds were rebuilt shortly thereafter. The sheds continued to be used for detaining and interrogating Chinese immigrants until the opening of immigration station facilities on Angel Island in 1910 for the processing Chinese and other immigrants.

A detail from the August Chevalier Map of 1915. The PMSSC sheds were located on Pier 36 at the intersection of Brannan and First Street.

The legacy of the PMSSC’s sheds, intertwined with their role at the inception of Chinese immigration to California and the US, is deeply rooted in San Francisco's maritime and Chinese American history. Both the company's operations and the experiences of the first wave of the Chinese diaspora arriving on American shores by steamships will remain forever part of the socio-economic dynamics of 19th-century San Francisco and the American West.

“Chinese Immigrants by the San Francisco Custom House” c. 1877. Detail of the magazine cover illustration by artist Paul Frenzeny for the Harper’s Weekly (from the collection of the New York Public Library.

[updated 2023-10-17]

#Pacific Mail Steamship Co.#Pacific Mail sheds#Chinese immigration detention#Carleton Wtakins#Paul Frenzeny#Harper's Weekly#SS Japan#In re Ah Fook#Stephen Field#Eadweard Muybridge#Pier 36 San Francisco

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

San Francisco map Old map of San Francisco 1853 Restoration Decor Style Vintage San Francisco map map art housewarming gift fine art print by VintageImageryX

22.00 USD

San Francisco map Old map of San Francisco 1853 Restoration Decor Style Vintage San Francisco map map art housewarming gift fine art print ◆ NEED A CUSTOM SIZE ?!?! Send us a message and we can create you one! ◆ D E S C R I P T I O N An rare and beautiful map of San Francisco and its vicinity circa 1853. This Map features areas as far as the Mission de Dolores or the Mission de San Francisco. Created following the gold rush, this map shows the city extending only about 8 city blocks from the waterfront. Featuring piers, wharf's, parks and roads as well as important buildings such as the City Hall, the Post Office, hospitals, and churches. The ocean areas have detailed depth soundings This map was created by the U.S. Coast Guard This map has a nice watercolor feel to it. This map makes a wonderful gift. Perfect for Home or office Painstakingly restored to its original beauty - more of our antique maps you can find here - https://ift.tt/K1PotWg ◆ S I Z E 16" x 20" / 41 x 51 cm 20" x 30" / 51 x 76 cm 24" x 30" / 61 x 76 cm 24" x 36" / 61 x 91 cm 28" x 43" / 71 x 109 cm 36" x 55" / 91 x 140 cm 43" x 64" / 109 x 163 cm *You can choose Your preferred size in listing size menu ◆ P A P E R Archival quality Ultrasmooth fine art matte paper 250gsm ◆ I N K Giclee print with Epson Ultrachrome inks that will last up to 108 years indoors ◆ B O R D E R All our prints have a small border. But if You need one without just message us at the time of ordering and we will take care of it ◆FRAMING: NONE of our prints come framed, stretched or mounted. Frames can be purchased through a couple of on line wholesalers: PictureFrames.com framespec.com When ordering a frame make sure you order it UN-assembled otherwise you could get dinged with an over sized shipping charge depending on the size frame. Assembling a frame is very easy and takes no more than 5-10 minutes and some glue. We recommend purchasing glass or plexi from your local hardware store or at a frame shop. ◆COLOR OF PRODUCT- Please also note that, although every effort is made to show our items accurately and describe my products in detail, we cannot guarantee every computer monitor will accurately depict the actual color of the merchandise. Please contact us with any further questions or concerns about the color or size of any map before purchasing. ◆ S H I P P I N G Print is shipped in a strong tube for secure shipping and it will be shipped as a priority mail for fast delivery. All International buyers are responsible for any duties & taxes that may be charged per country. ◆Disclaimer: These Restoration Hardware World Map prints are similar in style but are in no way affiliated with or produced by Restoration Hardware.

0 notes

Text

My US Travel Bucket List

1. New York City, NY

2. San Antonio, TX

3. Niagara Falls, New York

4. Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco

5. Old Faithful and Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park

6. South Beach, Miami

7. The Narrows, Zion National Park

8. Santa Fe, New Mexico

9. Pacific Coast Highway, California

10. Nashville, TN

11. Boston, Mass

12. Joshua Tree National Park, California

13. Maui, Hawaii

14. Anchorage, AK

15. Red Rocks Park and Amphitheatre, Colorado

16. Horse Show Bend, AZ

17. Austin, TX

18. Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota

19. Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta, New Mexico

20. Griffith Observatory, California

21. Going-to-the-Sun-Road, Glacier National Park

22. Las Vegas, NV

23. Acadia National Park, Maine

24. Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah

25. Liberty Bell and Independence Hall, Philadelphia

26. Hot Springs, Arkansas

27. Redwood National and State Parks, California

28. Crater Lake National Park, Oregon

29. Taos Pueblo, NM

30. Antelope Canyon, AZ

31. Lake Superior, MN

32. Arches National Park, Utah

33. Kentucky Derby, Louisville KY

34. Maxkinac Island, Lake Huron Michigan

35. Santa Monica, CA

36. NASA Space Center, Houston TX

37. Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

38. Fenway Park, Boston MA

39. Alcatraz Island, San Francisco CA

40. Drive the whole Route 66

41. Hollywood Boulevard, Los Angeles

42. Tour The White House

43. Disneyland

44. Death Valley

45. Elvis Presley’s Home in Memphis

46. Millennium Park, Chicago

47. Big Sur Coast, Carmel to San Francisco

48. Eastern State Penitentiary (Al Capone), Philadelphia

49. Tour Warner Brothers Studio, LA

50. Walk Across the Brooklyn Bridge, NYC

51. Catch a Cubs game in Chicago

52. Wine Tasting in Napa Valley, CA

53. Gateway Arch in St. Louis

54. Swim in the Havasu Falls Pools, Arizona

55. Universal Studios, Hollywood

56. Catch a Broadway Show

57. Visit the Smithsonian Museums in Washington DC

58. Maroon Bells, Aspen CO

59. Lake Tahoe, Straddling Nevada and California

60. Climb to the Hollywood Sign

61. Everglades National Park

62. Navy Pier, Chicago

63. White Sands National Monument, New Mexico

64. Central Park, New York

65. Martha’s Vineyard, Mass

66. Eat Lobster in Maine

67. Go to Coachella

68. Go to SBSW

69. lollapalooza

70. Experience a real American Ranch

71. Ben & Jerry’s Factory, Vermont

72. Watch A Rodeo in Cody, Wyoming

73. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Ohio

74. The Seven Magic Mountains, Nevada

75. Salem Witch Trials Tour

76. Visit Members Mark in Kentucky

77. Watch Talledega Super Speedway, Alabama

78. Salvation Mountain, Niland, CA

79. Hole N The Rock, Moab Utah

80. Carhenge: Alliance, Nebraska

81. Prada Marfa, Valentine TX

82. Enchanted Highway: North Dakota

83. Dinosaur Kingdom II, Natural Bridge Virginia

84. Cadillac Ranch, Amarillo TX

85. Winchester Mystery House, San Jose California

86. Pineapple Garden Maze: Wahiawa Hawaii

87. Gum Wall, Seattle WA

88. Bubblegum Alley, San Luis Obispo California

89. Flintstones Bedrock City, Coconino County Arizona

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rivera, Kahlo, and the Detroit Murals: A History and a Personal Journey

The year 1932 was not a good time to come to Detroit, Michigan. The Great Depression cast dark clouds over the city. Scores of factories had ground to a halt, hungry people stood in breadlines, and unemployed autoworkers were selling apples on street corners to survive. In late April that year, against this grim backdrop, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo stepped off a train at the cavernous Michigan Central depot near the heart of the Motor City. They were on their way to the new Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), a symbol of the cultural ascendancy of the city and its turbo-charged prosperity in better times. The next 11 months in Detroit would take them both to dazzling artistic heights and transform them personally in far-reaching, at times traumatic, ways.

I subtitle this article “a history and a personal journey.” The history looks at the social context of Diego and Frida’s defining time in the city and the art they created; the personal journey explores my own relationship to Detroit and the murals Rivera painted there. I was born and raised in the city, listening to the sounds of its bustling streets, coming of age in its diverse neighborhoods, growing up with the driving beat of its music, and living in the shadows of its factories. Detroit was a labor town with a culture of social justice and civil rights, which on occasion clashed with sharp racism and powerful corporations that defined the age. In my early twenties, I served a four-year apprenticeship to become a machine repair machinist in a sprawling multistory General Motors auto factory at Clark Street and Michigan Avenue that machined mammoth seven-liter V8 engines, stamped auto body parts on giant presses, and assembled gleaming Cadillacs on fast-moving assembly lines. At the time, the plant employed some 10,000 workers who reflected the racial and ethnic diversity of the city, as well as its tensions. The factory was located about a 20-minute walk from where Diego and Frida got off the train decades earlier but was a world away from the downtown skyscrapers and the city’s cultural center.

I grew up with Rivera’s murals, and they have run through every stage of my life. I’ve been gone from the city for many years now, but an important part of both Detroit and the murals have remained with me, and I suspect they always will. I return to Detroit frequently, and no matter how busy the trip, I have almost always found time for the murals.

In Detroit, Rivera looked outwards, seeking to capture the soul of the city, the intense dynamism of the auto industry, and the dignity of the workers who made it run. He would later say that these murals were his finest work. In contrast, Kahlo looked inward, developing a haunting new artistic direction. The small paintings and drawings she created in Detroit pull the viewer into a strange and provocative universe. She denied being a Surrealist, but when André Breton, a founder of the movement, met her in Mexico, he compared her work to a “ribbon around a bomb” that detonated unparalleled artistic freedom (Hellman & Ross, 1938).

Rivera, at the height of his fame, embraced Detroit and was exhilarated by the rhythms and power of its factories (I must admit these many years later I can relate to that response). He was fascinated by workers toiling on assembly lines and coal-fired blast furnaces pouring molten metal around the clock. He felt this industrial base had the potential to create material abundance and lay the foundation for a better world. Sixty percent of the world’s automobiles were built in Michigan at that time, and Detroit also boasted other state-of-the-art industry, from the world’s largest stove and furnace factory to the main research laboratories for a global pharmaceutical company.

“Detroit has many uncommon aspects,” a Michigan guidebook produced by the Federal Writers Project pointed out, “the staring rows of ghostly blue factory windows at night; the tired faces of auto workers lighted up by simultaneous flares of match light at the end of the evening shift; and the long, double-decker trucks carrying auto bodies and chassis” (WPA, 1941:234). This project produced guidebooks for every state in the nation and was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal Agency that sought to create jobs for the unemployed, including writers and artists. I suspect Rivera would have embraced the approach, perhaps even painted it, had it then existed.

Detroit was a rough-hewn town that lacked the glitter and sophistication of New York or the charm of San Francisco, yet Rivera was inspired by what he saw. In his “Detroit Industry” murals on the soaring inner walls of a large courtyard in the center of the DIA, Rivera portrayed the iconic Ford Rouge plant, the world’s largest and most advanced factory at the time. “[These] frescoes are probably as close as this country gets to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,” New York Times art critic Roberta Smith wrote eight decades later (Smith, 2015).

The city did not speak to Kahlo in the same way. She tolerated Detroit — sometimes barely, other times with more enthusiasm — rather than embracing it. Kahlo was largely unknown when she came to Detroit and felt somewhat isolated and disconnected there. She painted and drew, explored the city’s streets, and watched films — she liked Chaplin’s comedies in particular — in the movie theaters near the center of the city, but she admitted “the industrial part of Detroit is really the most interesting side” (Coronel, 2015:138).

During a personally traumatic year — she had a miscarriage that went seriously awry in Detroit, and her mother died in Mexico City — she looked deeply into herself and painted searing, introspective works on small canvases. In Detroit, she emerged as the Frida Kahlo who is recognized and revered throughout the world today. While Vogue still identified her as “Madame Diego Rivera” during her first New York exhibition in 1938, the New York Times commented that “no woman in art history commands her popular acclaim” in a 2019 article (Hellman & Ross, 1938; Farago, 2019).

My emphasis will be on Rivera and the “Detroit Industry” murals, but Kahlo’s own work, unheralded at the time, has profoundly resonated with new audiences since. While in Detroit, they both inspired, supported, influenced, and needed each other.

Prelude

Diego and Frida married in Mexico on August 21, 1929. He was 43, and she was 22 — although their maturity, in her view, was inverse to their age. Their love was passionate and tumultuous from the beginning. “I suffered two accidents in my life,” she later wrote, “one in which a streetcar knocked me down … the other accident is Diego” (Rosenthal, 2015:96).

They shared a passion for Mexico, particularly the country’s indigenous roots, and a deep commitment to politics, looking to the ideals of communism in a turbulent and increasingly dangerous world (Rosenthal, 2015:19). Rivera painted a major set of murals — 235 panels — in the Ministry of Education in Mexico City between 1923 and 1928. When he signed each panel, he included a small red hammer and sickle to underscore his political allegiance. Among the later panels was “In the Arsenal,” which included images of Frida Kahlo handing out weapons, muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros in a hat with a red star, and Italian photographer Tina Modotti holding a bandolier.

The politics of Rivera and Kahlo ran deep but didn’t exactly follow a straight line. Kahlo herself remarked that Rivera “never worried about embracing contradictions” (Rosenthal, 2015:55). In fact, he seemed to embody F. Scott Fitzgerald’s notion that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function” (Fitzgerald, 1936).

Their art, however, ultimately defined who they were and usually came out on top when in conflict with their politics. When the Mexican Communist Party was sharply at odds with the Mexican government in the late 1920s, Rivera, then a Party member, nonetheless accepted a major government commission to paint murals in public buildings. The Party promptly expelled him for this act, among other transgressions (Rosenthal, 2015:32).

Diego and Frida came to San Francisco in November 1930 after Rivera received a commission to paint a mural in what was then the San Francisco Stock Exchange. He had already spent more than a decade in Europe and another nine months in the Soviet Union in 1927. In contrast, this was Kahlo’s first trip outside Mexico. The physical setting in San Francisco, then as now, was stunning — steep hills at the end of a peninsula between the Pacific and the Bay — and they were intrigued and elated just to be there. The city had a bohemian spirit and a working-class grit. Artists and writers could mingle with longshoremen in bars and cafes as ships from around the world unloaded at the bustling piers. At the time, California was in the midst of an “enormous vogue of things Mexican,” and the couple was at the center of this mania (Rosenthal, 2015:32). They were much in demand at seemingly endless “parties, dinners, and receptions” during their seven-month stay (Rosenthal, 2015:36). A contradiction with their political views? Not really. Rivera felt he was infiltrating the heart of capitalism with more radical ideas.

Rivera’s commission produced a fresco on the walls of the Pacific Stock Exchange, “Allegory of California” (1931), a paean to the economic dynamism of the state despite the dark economic clouds already descending. Rivera would then paint several additional commissions in San Francisco before leaving. While compelling, these murals lacked the power and political edge of his earlier work in Mexico or the extraordinary genius of what was to come in Detroit.

While in San Francisco, Rivera and Kahlo met Helen Wills Moody, a 27-year-old world-class tennis player, who became the central model for the Allegory mural. She moved in rarified social and artistic circles, and as 1930 drew to a close, she introduced the couple to Wilhelm Valentiner, the visionary director of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), who had rushed to San Francisco to meet Rivera when he learned of the artist’s arrival.

Valentiner was “a German scholar, a Rembrandt specialist, and a man with extraordinarily wide tastes,” according to Graham W.J. Beal, who himself revitalized the DIA as director in the 21st century. “Between 1920 and the early 1930s, with the help of Detroit’s personal wealth and city money, Valentiner transformed the DIA … into one of the half-dozen top art collections in the country,” a position the museum continues to hold today (Beal, 2010:34). The museum director and the artist shared an unusual kinship. “The revolutions in Germany and Mexico [had] radicalized [both],” wrote Linda Downs, a noted curator at the DIA (Downs, 2015:177). Little more than a decade later, “the idea of the mural commission reinvigorated them to create a highly charged monumental modern work that has contributed greatly to the identity of Detroit” (Downs, 2015:177).

When Valentiner and Rivera met, the economic fallout of the Depression was hammering both Detroit and its municipally funded art institute. The city was teetering at the edge of bankruptcy in 1932 and had slashed its contribution to the museum from $170,000 to $40,000, with another cut on the horizon. Despite this dismal economic terrain, Valentiner was able to arrange a commission for Rivera to paint two large-format frescoes in the Garden Court at the new museum building, which had opened in 1927. Edsel Ford, the son of Henry Ford and a major patron of the DIA, pledged $10,000 for the project — a truly princely sum at that moment — and would double his contribution as Rivera’s vision and the scale of the project expanded (Rosenthal, 2015:51). Edsel also played an unheralded role in support of the museum through the economic traumas to come.

A discussion of Rivera’s mural commission gets a bit ahead of our story, so let’s first look at Detroit’s explosive economic growth in the early years of the 20th century. This industrial transformation would provide the subject and the inspiration for Rivera’s frescoes.

The Motor City and the Great Depression

At the turn of the 20th century, Detroit “was a quiet, tree-shaded city, unobtrusively going about its business of brewing beer and making carriages and stoves” (WPA, 1941:231). Approaching 300,000 residents, Detroit was the 13th-largest city in the country (Martelle, 2012:71). A future of steady growth and easy prosperity seemed to beckon.

Instead, Henry Ford soon upended not only the city, but much of the world. He was hardly alone as an auto magnate in the area: Durant, Olds, the Fisher Brothers, and the Dodge Brothers, among others, were also in or around Detroit. Ford, however, would go beyond simply building a successful car company: he unleashed explosive growth in the auto industry, put the world on wheels, and became a global folk hero to many, yet some were more critical. The historian Joshua Freeman points out that “Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) depicts a dystopia of Fordism, a portrait of life A.F. — the years “Anno Ford,” measured from 1908, when the Model T was introduced — with Henry Ford the deity” (Freeman, 2018:147).

Ford combined three simple ideas and pursued them with razor-sharp, at times ruthless, intensity: the Model T, an affordable car for the masses; a moving assembly line that would jump-start productivity growth; and the $5 day for workers, double the prevailing wage in the industry. This combination of mass production and mass consumption — Fordism — allowed workers to buy the products they produced and laid the basis for a new manufacturing era. The automobile age was born.

The $5 day wasn’t altruism for Ford. The unrelenting pace and control of the assembly line was intense — often unbearable — even for workers who had grown up with back-breaking work: tilling the farm, mining coal, or tending machines in a factory. Annual turnover approached 400 percent at Ford’s Highland Park plant, and daily absenteeism was high. In response, Ford introduced the unprecedented new wage on January 12, 1914 (Martelle, 2012:74).

The press and his competitors denounced Ford — claiming this reckless move would bankrupt the industry — but the day the new rate began, 10,000 men arrived at the plant in the winter darkness before dawn. Despite the bitter cold, Ford security men aimed fire hoses to disperse the crowd. Covered in freezing water, the men nonetheless surged forward hoping to grasp an elusive better future for themselves and their families.

Here is where I enter the picture, so to speak. One of the relatively few who did get a job that chaotic day was Philip Chapman. He was a recent immigrant from Russia who had married a seamstress from Poland named Sophie, a spirited, beautiful young woman. They had met in the United States. He wound up working at Ford for 33 years — 22 of them at the Rouge plant — on the line and on machines. They were my grandparents.

By 1929, Detroit was the industrial capital of the world. It had jumped its place in line, becoming the fourth-largest city in the United States — trailing only New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia — with 1.6 million people (Martelle, 2012:71). “Detroit needed young men and the young men came,” the WPA Michigan guidebook writers pointed out, and they emphasized the kaleidoscopic diversity of those who arrived: “More Poles than in the European city of Poznan, more Ukrainians than in the third city of the Ukraine, 75,000 Jews, 120,000 Negroes, 126,000 Germans, more Bulgarians, [Yugoslavians], and Maltese than anywhere else in the United States, and substantial numbers of Italians, Greeks, Russians, Hungarians, Syrians, English, Scotch, Irish, Chinese, and Mexicans” (WPA, 1941:231). Detroit was third nationally in terms of the foreign-born, and the African American population had soared from 6,000 in 1910 to 120,000 in 1930 (WPA, 1941:108), part of a journey that would ultimately involve more than six million people moving from the segregated, more rural South to the industrial cities of the North (Trotter, 2019:78).

DIA planners projected that Detroit would become the second-largest U.S. city by 1935 and that it could surpass New York by the early 1950s. “Detroit grew as mining towns grow — fast, impulsive, and indifferent to the superficial niceties of life,” the Michigan Guidebook writers concluded (WPA, 1941:231).

The highway ahead seemed endless and bright. The city throbbed with industrial production, the streetcars and buses were filled with workers going to and from work at all hours, and the noise of stamping presses and forges could be heard through open windows in the hot summers. Cafes served dinner at 11 p.m. for workers getting off the afternoon shift and breakfast at 5 a.m. for those arriving for the day shift. Despite prohibition, you could get a drink just about any time. After all, only a river separated Detroit from Canada, where liquor was still legal.

Rivera’s biographer and friend Bertram Wolfe wrote of “the tempo, the streets, the noise, the movement, the labor, the dynamism, throbbing, crashing life of modern America” (Wolfe, as cited in Rosenthal, 2015:65). The writers of the Michigan guidebook had a more down-to-earth view: “‘Doing the night spots’ consists mainly of making the rounds of beer gardens, burlesque shows, and all-night movie houses,” which tended to show rotating triple bills (WPA, 1941:232).

Henry Ford began constructing the colossal Rouge complex in 1917, which would employ more than 100,000 workers and spread over 1,000 acres by 1929. “It was, simply, the largest and most complicated factory ever built, an extraordinary testament to ingenuity, engineering, and human labor,” Joshua Freeman observed (Freeman, 2018:144). The historian Lindy Biggs accurately described the complex as “more like an industrial city than a factory” (Biggs, as cited in Freeman, 2018:144).

The Rouge was a marvel of vertical integration, making much of the car on site. Giant Ford-owned freighters would transport iron ore and limestone from Minnesota and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula down through the Great Lakes, along the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers, and then across the Rouge River to the docks of the plant. Seemingly endless trains would bring coal from West Virginia and Ohio to the plant. Coke ovens, blast furnaces, and open hearths produced iron and steel; rolling mills converted the steel ingots into long, thin sheets for body parts; foundries molded iron into engine blocks that were then precision machined; enormous stamping presses formed sheets of steel into fenders, hoods, and doors; and thousands of other parts were machined, extruded, forged, and assembled. Finished cars drove off the assembly line a little more than a day after the raw materials had arrived at the docks.

In 1928, Vanity Fair heralded the Rouge as “the most significant public monument in America, throwing its shadow across the land probably more widely and more intimately than the United States Senate, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Statue of Liberty.... In a landscape where size, quantity, and speed are the cardinal virtues, it is natural that the largest factory turning out the most cars in the least time should come to have the quality of America’s Mecca, toward which the pious journey for prayer” (Jacob, as cited in Lichtenstein, 1995:13). My grandfather, I suspect, had a more prosaic goal: he needed a job, and Ford paid well.

Despite tough conditions in the plant, workers were proud to work at “Ford’s,” as people in Detroit tended to refer to the company. They wore their Ford badge on their shirts in the streetcars on the way to work or on their suits in church on Sundays. It meant something to have a job there. Once through the factory gate, however, the work was intense and often dangerous and unhealthy. Ford himself described repetitive factory work as “a terrifying prospect to a certain kind of mind,” yet he was firmly convinced strict control and tough discipline over the average worker was necessary to get anything done (Ford, as cited in Martelle, 2012:73). He combined the regimentation of the assembly line with increasingly autocratic management, strictly and often harshly enforced. You couldn’t talk on the line in Ford plants — you were paid to work, not talk — so men developed the “Ford whisper” holding their heads down and barely moving their lips. The Rouge employed 1,500 Ford “Service Men,” many of them ex-convicts and thugs, to enforce discipline and police the plant.

At a time when economic progress seemed as if it would go on forever, the U.S. stock market drove over a cliff in October 1929, and paralysis soon spread throughout the economy. Few places were as shaken as Detroit. In 1929, 5.5 million vehicles were produced, but just 1.4 million rolled off Detroit’s assembly lines three years later in 1932 (Martelle, 2012:114). The Michigan jobless rate hit 40 percent that year, and one out of three Detroit families lacked any financial support (Lichtenstein, 1995). Ford laid off tens of thousands of workers at the Rouge. No one knew how deep the downturn might go or how long it would last. What increasingly desperate people did know is that they had to feed their family that night, but they no longer knew how.

On March 7, 1932 — a bone-chilling day with a lacerating wind — 3,000 desperate, unemployed autoworkers met near the Rouge plant to march peaceably to the Ford Employment Office. Detroit police escorted the marchers to the Dearborn city line, where they were confronted by Dearborn Police and armed Ford Service Men. When the marchers refused to disperse, the Dearborn police fired tear gas, and some demonstrators responded with rocks and frozen mud. The marchers were then soaked with water from fire hoses and shot with bullets. Five workers were killed, 19 wounded by gunfire, and dozens more injured. Communists had organized the march, but a Michigan historical marker makes the following observation: “Newspapers alleged the marchers were communists, but they were in fact people of all political, racial, and ethnic backgrounds.” That marker now hangs outside the United Auto Workers Local 600 union hall, which represents workers today at the Rouge plant.

Five days later, on March 12, thousands of people marched in downtown Detroit to commemorate the demonstrators who had been killed. Although Rivera was still in New York, he was aware of the Ford Hunger March before it took place and told Clifford Wight, his assistant, that he was eager “not [to] miss…[it] on any account” (Rosenthal, 2015:51). Both he and Kahlo had marched with workers in Mexico and embraced their causes. Rivera had captured their lives as well as their protests in his murals in Mexico.

As it turned out, they missed both the march and the commemoration. Instead, the following month Kahlo and Rivera’s train pulled into the Michigan Central Depot, where Wilhelm Valentiner met them. They were taken to the Ford-owned Wardell Hotel next to the Detroit Institute of Arts. The DIA was the anchor of a grass-lined and tree-shaded cultural center several miles north of downtown. The Ford Highland Park Plant, where the automobile age began with the Model T and the moving assembly line, was four miles further north on the same street. Less than a mile northwest was the massive 15-story General Motors Building, the largest office building in the United States when it was completed in 1922, designed by the noted industrial architect Albert Khan, who also created the Rouge. Huge auto production complexes such as Dodge Main or Cadillac Motor — where I would serve my apprenticeship decades later — were not far away.

Valentiner had written Rivera stating, “The Arts Commission would be pleased if you could find something out of the history of Detroit, or some motif suggesting the development of industry in this town. But in the end, they decided to leave it entirely to you” (Beal, 2010:35). Beal points out “that what Valentiner had in mind at the time may have been something like the Helen Moody Wills paintings, something that had an allegorical slant to it. They were to get something completely different” (Beal, 2010:35). Edsel Ford emphasized he wanted Rivera to look at other industries in Detroit, such as pharmaceuticals, and provided a car and driver for Rivera and Kahlo to see the plants and the city.

But when Rivera visited the Rouge plant, he was mesmerized. He saw the future here, despite the fact that the plant had been hard hit by the Depression: the complex had been shuttered for the last six months of 1931, and thousands of workers had been let go before he arrived (Rosenthal, 2015:67). His fascination with machinery, his respect for workers, and his politics fused in an extraordinary artistic vision, which he filled with breathtaking technical detail. He had found his muse.

Rivera took on the seemingly impossible task of capturing the sprawling Rouge plant in frescoes. The initial commission of two large-format frescoes rapidly expanded to 27 frescoes of various sizes filling the entire room from floor to ceiling. Rivera spent the next two months at the manufacturing complex drawing, pacing, photographing, viewing, and translating these images into large drawings — “cartoons” — as the plans for the frescoes. He demonstrated an exceptional ability to retain in his head — and, I suspect, in his dreams — what he would paint.

Rivera’s Vast Masterpieces

Rivera’s “Detroit Industry” murals are anchored in a specific time and place — a sprawling iconic factory, the Depression decade, and the Motor City — yet they achieve the universal in a way that transcends their origins. Rivera painted workers toiling on assembly lines amid blast furnaces pouring molten iron into cupolas, and through the alchemy of his genius, the art still powerfully — even urgently — speaks to us today. The murals celebrate the contribution of workers, the power of industry, and the promise and peril of science and technology. Rivera weaves together Aztec myths, indigenous world views, Mexican culture, and U.S. industry in a visual tour-de-force that delights, challenges, and provokes. The art is both accessible and profound. You can enjoy it for an afternoon or intensely study it for a lifetime with a sense of constant discovery.

Roberta Smith points out that the murals “form an unusually explicit, site-specific expression of the reciprocal bond between an art museum and its urban setting” (Smith, 2015). Over time, the frescoes have emerged as a visible and vital part of the city, becoming part of Detroit’s DNA. Rivera’s art has been both witness to and, more recently, a participant in history. When he began the project in late spring 1932, Detroit was tottering at the edge of insolvency, and 80 years later, the murals witnessed the city skidding into the largest municipal bankruptcy in history in 2013. A deep appreciation for the murals and their close identification with the spirit and hope of Detroit may have contributed to saving the museum this second time around.

I still vividly remember my own reaction when I first saw the murals. As a young boy, the Rouge, the auto industry, and Detroit seemed to course through our lives. My grandfather Philip Chapman, who was hired at Ford’s Highland Park plant in 1914, wound up spending most of his working life on the line at the Rouge. As a young boy, I watched my grandmother Sophie pack his lunch and fill his thermos with hot coffee before dawn as he hurried to catch the first of three buses that would take him to the plant. When my father, Max, came to Detroit three decades later in the mid-1940s to marry my mother, Rose — they had met on a subway while she was visiting New York City, where he lived — he worked on the line at a Chrysler plant on Jefferson Avenue.

One weekend, when I was 10 or 11 years old, my father took me to see the murals. He drove our 1950 Ford down Woodward Avenue, a broad avenue that bisected the city from the Detroit River to its northern border at Eight Mile Road. Woodward seemed like the main street of the world at the time; large department stores — Hudson’s was second only to Macy’s in size and splendor — restaurants, movie theaters, and office buildings lined both sides of the street north from the river. Detroit had the highest per capita income in the country, a palpable economic power seen in the scale of the factories and the seemingly endless numbers of trucks rumbling across the city to transport parts between factories and finished vehicles to dealers.

We walked up terraced white steps to the main entrance of the Detroit Institute of Arts, an imposing Beaux-Arts building constructed with Vermont marble in what had become the city’s cultural center. As we entered the building, the sounds of the city disappeared. We strolled the gleaming marble floors of the Great Hall, a long gallery topped far above by a beautiful curved ceiling with light flowing through large windows. Imposing suits of medieval armor stood guard in glass cases on either side of us as we crossed the Hall, passed under an arch, and entered a majestic courtyard.

We found ourselves in what is now called the Rivera Court, surrounded on all sides by the “Detroit Industry” murals. The impact was startling. We weren’t simply observing the frescoes, we were enveloped by them. It was a moment of wonder as we looked around at what Rivera had created. Linda Downs captured the feeling: “Rivera Court has become the sanctuary of the Detroit Institute of Arts, a ‘sacred’ place dedicated to images of workers and technology” (Downs, 1999:65). I couldn’t have articulated this sentiment then, but I certainly felt it.

The size, scale, form, pulsing activity, and brilliant color of the paintings deeply impressed me. I saw for the first time where my grandfather went every morning before dawn and why he looked so drawn every night when he came home just before dinner. Many years later, I began to appreciate the art in a much deeper way, but the thrill of walking into the Rivera Court on that first visit has never left. I came to realize that an indelible dimension of great art is a sense of constant discovery and rediscovery. The murals captured the spirit of Detroit then and provide relevance and insight for the times we live in today.

Beal points out that Rivera “worked in a heroic, realist style that was easily graspable” (Beal, 2010:35). A casual viewer, whether a schoolboy or an autoworker from Detroit or a tourist from France, can enjoy the art, yet there is no limit to engaging the frescoes on many deeper levels. In contrast, “throughout Western history, visual art has often been the domain of the educated or moneyed elite,” Jillian Steinhauer wrote in the New York Times. “Even when artists like Gustave Courbet broke new ground by depicting working-class people, the art itself still wasn’t meant for them” (Steinhauer, 2019). Rivera upended this paradigm and sought to paint public art for workers as well as elites on the walls of public buildings. By putting these murals at the center of a great museum in the 1930s through the efforts of Wilhelm Valentiner and Edsel Ford — and more recently, under Graham Beal and the current director Salvador Salort-Pons — the Detroit Institute of Arts opened itself and the murals to new Detroit populations. Detroit is now 80-percent African American, the metropolitan area has the highest number of Arab Americans in the United States, and the Latino population is much larger than when Rivera painted, yet the murals retain their allure and meaning for new generations.

Upon entering the Rivera Court, the viewer confronts two monumental murals facing each other on the north and south walls. The murals not only define the courtyard, they draw you into the engine and assembly lines deep inside the Rouge. The factory explodes with cacophonous activity. The production process is a throbbing, interconnected set of industrial activities. Intense heat, giant machines, flaming metal, light, darkness, and constant movement all converge. Undulating steel rail conveyors carry parts overhead. There were 120 miles of conveyors in the Rouge at the time; they linked all aspects of production and provide a thematic unity to the mural. And even though he’s portraying a production process in Detroit, Rivera’s deep appreciation of Mexican culture and heritage infuses the frescoes. An Aztec cosmology of the underworld and the heavens runs in long panels spanning the top of the main murals and similar imagery appears throughout the frescoes.

On the north wall, a tightly packed engine assembly line, with workers laboring on both sides, is flanked by two huge machine tools — 20 feet or so high — machining the famed Ford V8 engine blocks. Workers in the foreground strain to move heavy cast-iron engine blocks; muscles bulge, bodies tilt, shoulders pull in disciplined movement. These workers are not anonymous. At the center foreground of the north wall, with his head almost touching a giant spindle machine, is Paul Boatin, an assistant to Rivera who spent his working life at the Rouge. He would go on to become a United Auto Workers (UAW) organizer and union leader. Boatin had been present at the Ford Hunger March on that disastrous day in March 1932 and still choked up talking about it many decades later in an interview in the film The Great Depression (1990).

In the foreground, leaning back and pulling an engine block with a white fedora on his head may have been Antonio Martínez, an immigrant from Mexico and the grandfather of Louis Aguilar. A reporter for the Detroit News, Aguilar describes how fierce, at times ugly, pressures during the Great Depression forced many Mexicans to leave Detroit and return to their homeland. The city’s Mexican population plummeted from 15,000 at the beginning of the 1930s to 2,000 at the end of the decade. If the figure in the mural is not his grandfather, Aguilar writes “let every Latino who had family in Detroit around 1932 and 1933 declare him as their own” (Aguilar, 2018).

A giant blast furnace spewing molten metal reigns above the engine production, which bears a striking resemblance to a Charles Sheeler photo of one of the five Rouge blast furnaces. The flames are so intense, and the men so red, you can almost feel the heat. In fact, the process is truly volcanic and symbolic of the turbulent terrain of Mexico itself. It brings to mind Popocatépetl, the still-active 18,000-foot volcano rising to the skies near Mexico City. To the left, above the engine block line, green-tinted workers labor in a foundry, one of the dirtiest, most unhealthy, most dangerous jobs. Meanwhile, a tour group observes the process. Among them in a black bowler hat is Diego Rivera himself.

On the south wall, workers toil on the final assembly line just before the critical “body drop,” where the body of a Model B Ford is lowered to be bolted quickly to the car frame on a moving assembly line below. Once again, through his perspective Rivera draws you into the line. A huge stamping press to the right forms fenders from sheets of steel like those produced in the Rouge facilities. Unlike most of the other machines Rivera portrays, which are state of the art, this press is an older model, selected because of its stylized resemblance to an ancient sculpture of Coatlicue, the Aztec goddess of life and death (Beale, 2010:41; Downs, 1999:140, 144).

On the left is another larger tour group, which includes a priest and Dick Tracy, a classic cartoon character of the era. The Katzenjammer Kids — more comic icons of the time — are leaning on the wall watching the assembly line move. The eyes of most of the visitors seem closed, as if they were physically present, but not seeing the intense, occasionally brutal, activity before them. Rivera, in effect, is giving us a few winks and a nod with cartoon characters and unobservant tourists.

~ Harley Shaiken · Fall 2019.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Day 36 — Walk the Plank

Walking the plank was a method of execution practiced by pirates, mutineers, and other rogue seafarers. Captives were bound so they could not swim or tread water and forced to walk off a wooden plank or beam extended over the side of a ship.

Although forcing captives to walk the plank is a motif of pirates in popular culture, few instances are documented, so the frequency of the practice is uncertain.

The phrase is recorded in English lexicographer Francis Grose's Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, published in 1785.

Grose writes: Walking the plank. A mode of destroying devoted persons or officers in a mutiny on ship-board, by blind-folding them, and obliging them to walk on a plank laid over the ship's side; by this means, as the mutineers suppose, avoiding the penalty of murder.

Despite the rarity of the practice in history, walking the plank entered popular myth and folklore via depictions in popular literature. Robert Louis Stevenson's 1884 classic Treasure Island contains at least three mentions of walking the plank.

Photo: Extended beam on fishing pier, Central Basin, San Francisco

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#san francisco#view#hill#tresureisland#alcatraz#pier39#pier 14#pier 36#bay bridge#ocean#russian hill#ferry building#retro#black and white#b/w

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompts

You can find the list of prompts below. Feel free to select any prompt and create OutlawQueen art (fic, manip, video) inspired by it. You can of course combine several prompts in one creation.

You can submit any creation you want whether it is a new one or an old one. About the fics, it can be included in any of your existing verses. However, note that any ancient work will not be counted as an entry to win a button.

OQ on Holidays Week will take place from August 20th to 26th, so please, don’t post anything before.

In the meantime, don’t hesitate to tweet or DM me at this account @OQonHolidays if you have any questions.

Here’s the list of prompts:

1. Regina Roland and Robin, who can’t stand very loud or very crowded spaces, in Times Square.

2. Regina & Robin vacation in England, they visit the ‘real’ Sherwood Forest and town of Nottingham, see the statue of Robin Hood and touristy Robin Hood themed gift shops. Robin isn’t a fan of his likeness being used to make money.

3. Entire Hood-Mills family (Robin, Regina, Henry, Roland and Robyn) goes to Disney World during ‘villains month’.

4. Robin takes Regina camping somewhere out in the wilderness where she doesn’t have her magic. Regina discovers she is NOT an outdoorsy kind of woman...

5. Regina takes Robin to Hyperion Heights for the first time, to the bar and her former apartment, and people still think of her as the wild tattooed bartender Roni. She’s embarrassed of her cursed persona, but Robin wants to get to know ‘Roni’.

6. Evil Queen takes Wish Robin out into the real world for the first time and decides to take him to New York City.

7. Robin and Regina go to Vietnam.

8. On a family vacation, OQ family finds an abandoned puppy on a beach. Roland and Henry try to convince their parents to keep it and take it back home.

9. Robin, Regina, Emma, Mary Margaret, Killian (any other character can be included) are all good friends. Robin and Regina's friends realize they're in love but don't act on their feelings. So, they decide to push them a little. They all plan a holiday trip: book air tickets, hotel accomodation, activities. But at the last minute their friends don't show up and Robin and Regina are forced to spend a week with each other on vacation (maybe sharing a room) and ...well, maybe it's exactly what they need!

10. Robin and Regina go to a fan convention for Henry’s ‘Once Upon a Time’ book outside of Storybrooke to support him and it’s just uncanny how well they ‘cosplay’ as Robin Hood and Regina Mills…

11. Robin and Regina take Robyn to a heavy metal concert out in California. Turns out Robyn wasn’t interested in the music so much as she was interested in the girl from Storybrooke who just so happens to be into this band...

12. DarkOQ are on holiday in the EF with Roland and get attacked by monsters.

13. OQ are in holiday with their children and Roland gets lost

14. Robin and Regina are both skilled contract killers working for different firms meeting for the first time in bogota Columbia during a pretended or real holidays. Of course, they have no idea that the other one is a contract killer, and even less that they have the same target (based on the movie Mr & Mrs. Smith)

15. A weekend camping trip with the boys [dealer's choice on good or bad trip]

16. Regina takes Robin on his first plane ride

17. Honeymooning in Hawaii

18. A romantic cruise that veers into the Bermuda Triangle

19. Hiking in the Redwoods [with or without the boys]

20. Henry or Roland get food poisoning on vacation and need TLC

21. A day at the beach ends with Regina getting sun poisoning

22. Henry and Roland go to summer camp, leaving Regina & Robin on a staycation at home

23. First family roadtrip

24. Robyn's first day at the beach with Robin, Regina, & the boys [Zelena optional]

25. Robyn gets her first period on vacation with the family

26. Regina teaches Roland how to swim

27. Regina and Henry are in holidays on a cruise, the same cruise as Robin and Roland. Robin, Regina’s ex-boyfriend from college. The first time they face each other, things aren’t that simple and a lot of grudge is still present. But as the two kids become friends, their parents are forced to spend time together, and talk about their past...

28. “Best vacation ever!"

29. “Why did I agree to this trip?"

30. "Look! I even laminated our itinerary AND synced it to everyone's phones!"

31. “Your mum is stunning when she lets herself enjoy nature."

32. Family day at the beach

33. OQ spends a few days at the beach, without the kids, and things get steamy on the sands... Or above a rock ;)

34. Regina breaks her leg during her holidays with her parents and sister, and is forced to stay behind while they are out visiting. One day she decides to get out to get some fresh air and ends up running into a certain British boy with deep dimples and ocean blue eyes.

35. Regina isn't in the mood for a holiday, but her friends drags her with them and in the end she ends up being grateful that she went. Because she meets the love of her life.

36. Regina takes a well deserved holiday in Mykonos. Her plan? Party, have fun, maybe meet a guy or two for a one-night stands, and forget her awful boss and pressuring job. But when her eyes fall upon the bartender of her hotel, a handsome British man with blue eyes and a sexy accent, her plans to stick to one-night stands completely fall apart.

37. At Henry’s request, Regina and Robin organize a family trip (Roland comes too) to Maya’s ruins. But as they visit a temple, they unleash a powerful magic that threatens everyone’s lives.

38. Regina is on a holiday trip with her friend Tink in Spain. At her friends’ request, Regina let’s a fortune teller read the lines of her hand. Regina, a confirmed bachelor, doesn’t believe her when the woman predicts that she’ll meet her soulmate during this trip : a man with a lion tattoo. That is, until she meets a handsome man with intriguing blue eyes, adorable dimples, and a certain tattoo...

39. “What are you doing in my hotel room?”

40. Romantic holidays in Paris

41. Robin and Regina take their whole family on holidays. Henry meets a girl he has a huge crush on, and Robin has to help Regina deal with her mama bear feelings and let her son enjoy this summer love.

42. A week at the beach. Roland almost drowns.

43. Wish Robin convinces (after several attempts) the Evil Queen to spend a week in the Forest. Whether it ends up being phenomenal or a complete failure is up to you.

44. Regina, Leopold and Snow take a vacation to one of the other realms of the Enchanted Forest and they meet a certain thief on the road during their journey.

45. Regina discovers that she’s pregnant a week before a long planned holidays, and she’s extremely nauseous. “I’m ruining everyone’s holidays.” “No, you’re not.”

46. Regina and Robin go back to Camelot to take a few days off for themselves and they end up waking up an evil everyone had forgotten about.

47. OQ take their children and Robyn (who’s about 15 yo) on a trip to San Francisco. “Regina, I really like this girl we met on the pier.”

48. Robin and Regina have marital issues. Their therapist suggests they take some holidays, just the two of them, to work on their relationship without having to worry about the kids. Will it work in helping them remember how much they still love each other?

49. “I always dreamt to visit Venise.”

50. During the Missing Year, Regina isn’t doing well, she misses her son and feels like she doesn’t belong. A certain thief offers her to take her away for a few days, to help change her mind.

51. Regina and Robin are best friends who decide to go on a trip to Las Vegas together. As they say, what happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas

52. Leopold takes Regina to his hunting lodge in the mountains, she gets lost and almost dies in a blizzard, Robin finds her, brings her back to his cabin to nurse her back to health.

53. Regina and Robin take a few days off for their first Thanksgiving together as a married couple. Regina has a little more to be greatful for than she expected

54. Robin and Regina are friends. Regina went through a tough break up after a long relationship with Daniel. Daniel was an ass, lied, cheated, whatever. Robin has been secretly in love with Regina, but has waited patiently for her to get over Daniel, and it seems she succeeds.They plan this vacation as friends (it can be with other friends) and in the trip they bump into Daniel. This makes Regina doubtful again, Robin is jealous, maybe Daniel tries to win Regina again, and due to the circumstances Robin has to tell Regina how he feels about her.

55. Modern AU: Regina dedicates most of her time to her job and her best friend convinces her to finally take a break. Her friend books a trip for her with a travel agency. Regina reluctantly goes to the trip and is in a bad mood, always thinking about her job and what she has to do when she goes back, until she meets the tour leader, Robin.

56. Regina and Robin in Greece (preferably not at the most popular and crazy crowded places)

57. Regina and Robin go castle-seeing in England

58. For father's day (or mother's day, you choose), they plan a surprise holiday, so they can celebrate it somewhere else.

59. Robin and Regina on their honeymoon; a week in a haute top floor Paris suite where Robin is completely out of his element but he endures it for his new bride

60. Families were accidentally booked for the same cabin, beach house, airbnb and decide to share the space so neither have to cancel the vacation

61. Visiting Robin’s family in England

62. Visiting Regina’s family in Puerto Rico

63. Regina getting racially profiled at the airport, Robin defends her (either established relationship or first meeting)

64. Roland and/or Henry get lost at airport or at destination

65. Home alone holidays AU

66. Jolly Roger

67. Ship wreck (AU or Jolly Roger)

68. Plane crash

69. Honeymoon

70. Cruise

71. Traveling to meet their new baby/child/children (adoption AU)

72. Mile high club

73. Every year the children point to a spot on a map / globe and that is where they go now $%*^@#* picked Utah / Iran ??? and is so excited but no one else wants to go.

74. Time machine.