#Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

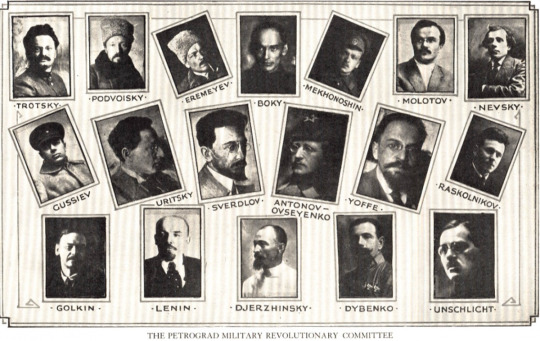

The Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee. (1917)

#Russian Revolution#The Russian Revolution#Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee#Leon Trotsky#Nikolai Podvoisky#Konstantin Eremeev#Gleb Bokii#Konstantin Mekhonoshin#Vyacheslav Molotov#Vladimir Nevsky#Sergey Ivanovich Gusev#Moisei Uritsky#Yakov Sverdlov#Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko#Adolph Joffe#Fyodor Raskolnikov#A. V. Galkin#Vladimir Lenin#Felix Dzerzhinsky#Pavel Dybenko#Józef Unszlicht

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

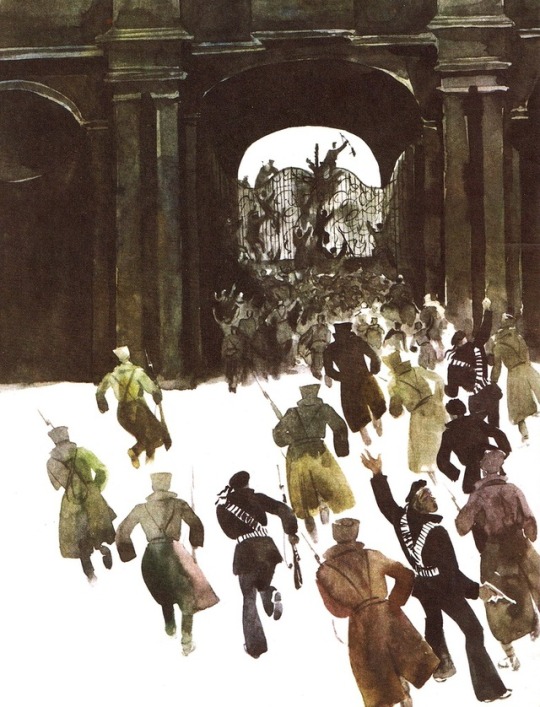

Bolshevik seizure of power

'The instrument of the seizure of power in Petrograd, the Military Revolutionary Committee, was created not by the Bolsheviks, but by the Petrograd Soviet as a whole, to organize the defense of the capital against either a second military coup or a German attack. From about 20 October the MRC began taking control of strategic points in the city in order to ensure that the Provisional Government did not prevent the second All-Russian Congress of Soviets from meeting. The final operation was launched on 24-25 October, when Kerenskii tried to close Bolshevik newspapers and arrest leading Bolsheviks. Most participants in the rising thought that they were fighting for "All Power to the Soviets," to be embodied in the form of a coalition socialist government which would endorse the authority of the workers', soldiers', and peasants' assemblies throughout the country. However, at the Congress of Soviets Lenin was unexpectedly able to set up a single-party Bolshevik government (the "Council of People's Commissars," or Sovnarkom) because by then he had secured the support of a sizeable contingent of SR delegates. ... In most localities the Bolsheviks were able to seize power in similar ways. Where they were popular, they used their majority to dominate local soviets; where they were less popular, they set up or took over an armed militia, usually called a Military Revolutionary Committee, to coerce or replace the soviet and enforce "All Power to the Soviets" on their own terms. Within a few months, wherever they held power, the Bolsheviks consolidated it by closing down nonsocialist newspapers and establishing their own security police in the form of the Cheka, or Extraordinary Commission for Struggle against Speculation and Counterrevolution. They allowed popular elections to the Constituent Assembly to go ahead, but when it became clear that the SRs were to be the largest single party in it, the Bolsheviks simply closed the assembly down.'

Russia and the Russians, by Geoffrey Hosking

#october revolution#russian revolution#bolsheviks#lenin#soviets#military revolutionary committees#kerensky#provisional government#left sr#socialist revolutionary party#cheka#political police#party state

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 11.2

619 – A qaghan of the Western Turkic Khaganate is assassinated in a Chinese palace by Eastern Turkic rivals after the approval of Tang emperor Gaozu. 1410 – The Peace of Bicêtre suspends hostilities in the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War. 1675 – Plymouth Colony governor Josiah Winslow leads a colonial militia against the Narragansett during King Philip's War. 1795 – The French Directory, a five-man revolutionary government, is created. 1868 – Time zone: New Zealand officially adopts a standard time to be observed nationally. 1882 – The great fire destroys a large part of Oulu's city center in Oulu Province, Finland. 1889 – North Dakota and South Dakota are admitted as the 39th and 40th U.S. states. 1899 – The Boers begin their 118-day siege of British-held Ladysmith during the Second Boer War. 1912 – Bulgaria defeats the Ottoman Empire in the Battle of Lule Burgas, the bloodiest battle of the First Balkan War, which opens her way to Constantinople. 1914 – World War I: The Russian Empire declares war on the Ottoman Empire and the Dardanelles is subsequently closed. 1917 – The Balfour Declaration proclaims British support for the "establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people" with the clear understanding "that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities". 1917 – The Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, in charge of preparation and carrying out the Russian Revolution, holds its first meeting. 1920 – In the United States, KDKA of Pittsburgh starts broadcasting as the first commercial radio station. The first broadcast is the result of the 1920 United States presidential election. 1936 – The BBC Television Service, the world's first regular, "high-definition" (then defined as at least 200 lines) service begins. Renamed BBC1 in 1964, the channel still runs to this day. 1940 – World War II: First day of Battle of Elaia–Kalamas between the Greeks and the Italians. 1947 – In California, designer Howard Hughes performs the maiden (and only) flight of the Hughes H-4 Hercules (also known as the "Spruce Goose"), the largest fixed-wing aircraft ever built until Scaled Composites rolled out their Stratolaunch in May 2017. 1949 – The Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference ends with the Netherlands agreeing to transfer sovereignty of the Dutch East Indies to the United States of Indonesia. 1951 – Canada in the Korean War: A platoon of The Royal Canadian Regiment defends a vital area against a full battalion of Chinese troops in the Battle of the Song-gok Spur. The engagement lasts into the early hours the next day. 1956 – Hungarian Revolution: Nikita Khrushchev meets with leaders of other Communist countries to seek their advice on the situation in Hungary, selecting János Kádár as the country's next leader on the advice of Josip Broz Tito. 1956 – Suez Crisis: Israel occupies the Gaza Strip. 1959 – Quiz show scandals: Twenty-One game show contestant Charles Van Doren admits to a Congressional committee that he had been given questions and answers in advance. 1959 – The first section of the M1 motorway, the first inter-urban motorway in the United Kingdom, is opened between the present junctions 5 and 18, along with the M10 motorway and M45 motorway.

0 notes

Text

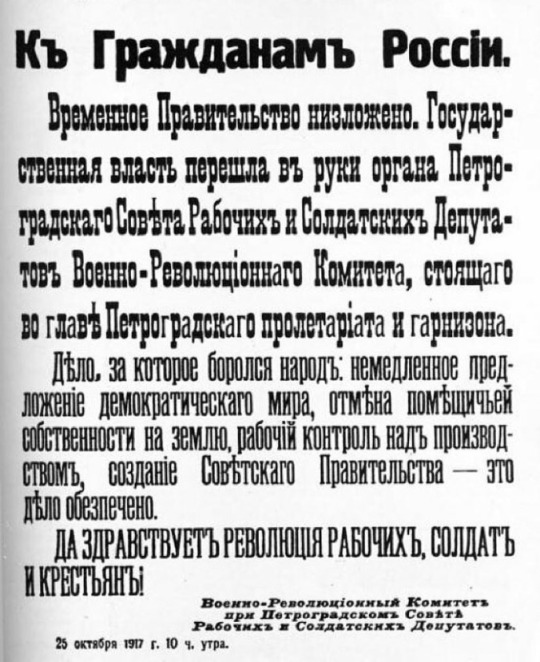

'The Provisional Government has been deposed'

‘The Provisional Government has been deposed’

To the Citizens of Russia!

The Provisional Government has been deposed. State power has passed into the hands of the organ of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies–the Military-Revolutionary Committee, which heads the Petrograd proletariat and the garrison.

The cause for which the people have fought, namely, the immediate offer of a democratic peace, the abolition of landed…

View On WordPress

#Bolsheviks#capitalism#communist#Lenin#Military-Revolutionary Committee#October Revolution#peasants#Petrograd#Provisional Government#sailors#socialism#soldiers#soviets#Trotsky#workers

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fivan + 2 please ❤ in your modern au or in canon, idc

2. “Stay here tonight.”

It is the night of October 25, 1917, in the Old Style, and outside the windows, the streets of Petrograd are in total chaos. The telegraph lines of the Winter Palace have been cut, even as Vladimir Ilyich Lenin's proclamation, To the Citizens of Russia, clatters across the wires to every corner of the country, proclaiming the overthrow of the Provisional Government established in February and the total victory of the Bolsheviks and their Military-Revolutionary Committee. Fedyor Mikhailovich Kaminsky is one of the few soldiers still at his post, even though he knows that it's only a matter of time. He can hear the distant, surging roar of the revolutionaries coming closer and closer, the boom of the cruiser firing shots in the harbor, the song of angry men. They will be in here before the night is out.

His hands are slick with sweat, but he holds his gun as tightly as he can. The cabinet of the Provisional Government is closeted within, leaving a scanty force of soldiers, officers, Cossacks, and cadets to resist the imminent invasion, but it's clear they will have to flee, as Tsar Nicholas II and his family have already done. There are already whispers among the men that they should do the same, turn their coats and join the victorious rebels. Fedyor hasn't decided where he falls. He has a duty here. He can't just leave it. And yet.

The roar comes closer, something living and furious and savage, the crash of breaking windows and rattling iron, as the forty-thousand-strong Bolshevik mob surges against the gates of the Winter Palace and breaks them down. Minutes later, they're inside. There follows almost three hours of confused fighting among the glittering hallways and under the chandeliers where grand dukes and princes whirled their wives and mistresses by the bejeweled hand, in all the decadence and splendor of the imperial court. Priceless paintings are ripped to shreds, glass and woodwork smashed. Fedyor fights messily, hand to hand, whichever of them he encounters. Until he comes around a corner, runs straight into one of them and is caught clean off guard, and the next moment, backhanded viciously to the floor.

As the Bolshevik raises the butt of his rifle to smash Fedyor's face in, he discovers to his disgust that he is in fact, at the end, a coward more than he is a loyalist. "Don't," he begs. "Don't kill me. I surrender."

The Bolshevik stares at him grimly down his long nose, from a face that seems made for the express purpose of scowling. At this close range, Fedyor can tell from the insignia on his collar that he is a member of the Red Guard, the paramilitary people's organization drawn together to support the establishment of a supreme soviet socialist republic. In other words, the most dedicated and ruthless of all the Bolsheviks, and Fedyor has no reason to think this one will show him mercy. He squeezes his eyes shut and waits for the end.

It doesn't come. He dares to open his eyes. The Red Guard is still glaring at him, but in frustration. Then he snaps, "What's someone like you doing here? How old are you? Twelve?"

"Nineteen." Fedyor bristles. To judge from his speech, this newcomer is from Siberia, which has probably been a fertile recruiting ground for long jeremiads about the excessive luxury of the urban elite, and Fedyor does not intend to be judged by some cowpoke. "If we're asking that question, why are you here? Hasn't anyone ever told you that it's treasonous to overthrow the government?"

To his surprise, the Bolshevik snorts, as if he didn't want to laugh, isn't used to laughing, and is slightly annoyed that Fedyor made him do it. "Get out of here," he advises tersely. "Or turn your coat and join us. I might not have killed you, but someone else will."

This is, in all respects, a fine idea, but something still makes Fedyor hesitate. "I, uh," he says awkwardly. "Thank you for, you know. Not doing that. I suppose."

"No honor in killing boys." The Red stares at him, flinty-eyed and imperturbable. This is not the moment, it really is not, to notice that he is rather handsome. "I said. Get out."

Fedyor mutters a prayer for the Almighty to forgive him, if God has not been asleep in Heaven for quite a long time now when it comes to Russia, and the devil, in the person of Grigori Rasputin, has been ruling instead. Then he dodges through the chaotic corridors, clambers through a broken window into the palace grounds, and makes his escape, with no idea what to do or where to go. All around him, the night resounds with sound and fury.

He finally finds somewhere in a side alley to dodge out of sight and await the inevitable. Just past two AM, he hears the bells ringing across the city, a sign that the revolutionaries have fully seized control of the Winter Palace, and it's done, it's over, his side has lost. Perhaps he should feel more upset about this than he does. It is abstract.

Fedyor spends the next two days adrift in the shattered sea of Petrograd, everyone completely agog and afraid and with no idea what will happen to them now. He sells his soldier's coat with its brass buttons for food and a blanket, reduced to no better than any other of the terrified refugees. He can't go back to the Winter Palace, and the revolutionaries are blocking any train he might take home to Nizhny Novgorod. He sits near the dock as the third evening is falling, shivering and hungry and scared. What now, what now, what --

"What are you doing here?"

He jumps out of his wits at the angry hiss, nearly drops his blanket in the water, and startles to his feet. It can't be, but it is, the Red Guard who spared him in the assault. They stare at each other. The Bolshevik looks like he has been on patrol, rifle on his back, and while it's not the wisest thing to say to such a terrifying-looking fellow, it comes out anyway. "Are you ever," Fedyor says, "going to ask me something besides what I'm doing somewhere? Such as my name?"

The humorless Red bastard scowls at him. Then he demands, as if he would in fact like to know the answer and is very annoyed about it, "So what is your name?"

"Fedyor." Fedyor folds his arms. "Fedyor Mikhailovich Kaminsky. You?"

"Ivan." It comes after a long, reluctant pause. "Ivan Ivanovich Sakharov. You should get off the streets."

"I don't have anywhere else to go."

Ivan Ivanovich acknowledges that with a terse nod. He debates with himself, then thrusts out a hand. "This way."

Fedyor follows him warily, not sure if he's being lured off to be shot in the head like the rest of the White Russians, but Ivan leads him to a tiny hovel in the working-class districts of Petrograd, a small room lit by a gaslamp. "You can stay here tonight," he says brusquely. "Just one night, do you hear me? After that, I can't help you."

"All right." Deciding not to look a gift horse in the mouth, Fedyor warily sits down. "And you? Where do you sleep?"

"Since you are there -- " Ivan jerks his chin at the narrow bed -- "on the floor. Do not be mistaken. I do not like you. As I said. It is only a matter of honor. Even rebels have it, you know."

Fedyor isn't sure, but he doesn't want to disagree. He lies down and folds his hands on his chest, staring at the garret ceiling, as Ivan Ivanovich settles on the frayed rug. And so -- it is strange, impossible, but no more than anything else in this new world with no rules -- side by side, imperial soldier and Red revolutionary, they sleep.

#ivan x fedyor#heartrender husbands#fivan#anonymous#ask#anon: modern au or canon!#me barging in with donuts and a cigarette hanging out of my mouth: FIVAN RUSSIAN REVOLUTION AU? ANYONE? I GOT YOUR AUS RIGHT HERE!#anyway i had feelings about this so here you go#fivan ff#russian revolution au

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

103rd Anniversary of the Russian Revolution

On this day in 1917, the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee, an arm of the Soviet, ousted the Provisional Government from the city. It marked the beginning of the October Revolution, the struggle for soviet power in Russia against various counterrevolutionary forces from across the globe, the first such struggle in history. It would conclude in 1923 with the victory of the Red Army and the establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

We have made the start. When, at what date and time, and the proletarians of which nation will complete this process is not important. The important thing is that the ice has been broken; the road is open, the way has been shown.

Lenin, “Fourth Anniversary of the October Revolution”

Vladimir Serov, Lenin proclaims Soviet power in Smolny Palace, Petrograd, 1917

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

143rd anniversary since the birth of comrade F. E. Dzerzhinsky!

( 11.9.1877-20.7.1926 ) A Bolshevik, a people's Commissar, a knight of the revolution, the Creator of the Cheka, who mercilessly fought against the enemies of the Soviet government, restored the country from ruin and saved homeless children. To the young man who thinks about life, solve the problem - make a life with whom, I'll tell you without hesitation: - Do it with comrade Dzerzhinsky.

V. V. Mayakovsky (the poem " Good")

Dzerzhinsky Felix Edmundovich was born on September 11, 1877 in the new style in the estate of Dzerzhinovo, Oshmyansky district, Vilna province. He died on July 20, 1926 in Moscow. Outstanding Soviet, party, statesman, member of the Polish and Russian revolutionary movement. In 1895, he joined the Lithuanian social democratic organization, and in 1900, the Social democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (Sdkpil). Led party work in Vilna, cities of the Kingdom of Poland, St. Petersburg. One of the leaders of the Revolution of 1905-1907 (Warsaw). Since 1906, the representative of the Sdkpil in the Central Committee of the RSDLP. In 1907. elected a member of the Central Committee of the RSDLP. He was arrested several times, escaped twice, and was released several times under Amnesty.he spent 11 years in hard labor and exile. In 1917, he joined the RSDLP (b). From August 1917, he was a member of the Central Committee and the party Secretariat. During the October revolution, he was a member of the Petrograd military revolutionary Committee. From November 1917, a member of the Board of the NKVD. 7 (20). 12. 1917, at the suggestion of V. I. Lenin, was appointed Chairman of the Cheka under the SNK of the RSFSR, whose task is to fight counter-revolution and sabotage. From August 1919, he simultaneously headed a Special Department of the Cheka-military counterintelligence, and from November 1920, border protection. People's Commissar of internal Affairs in 1919-1923, simultaneously with 1921 people's Commissar of Railways, since 1924 Chairman of the Supreme Council of National Economy-VSNH of the USSR; since 1921 Chairman of the Commission for improving the lives of children at the Central Executive Committee. From 1924 a candidate member of the Politburo and the orgburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU(b), a member of the Central Executive Committee and the CEC of the USSR.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

1919: When the Bolsheviks Turned on the Workers—Looking Back on the Putilov and Astrakhan Strikes, One Hundred Years Later

One hundred years ago in Russia, thousands of workers were on strike in the city of Astrakhan and at the Putilov factory in Petrograd, the capital of the revolution. Strikes at the Putilov factory had been one of the principal sparks that set off the February Revolution in 1917, ending the tsarist regime. Now, the bosses were party bureaucrats, and the workers were striking against a socialist government. How would [the dictatorship of the proletariat respond?

Following up on our book about the Bolshevik seizure of power, The Russian Counterrevolution, we look back a hundred years to observe the anniversary of the Bolshevik slaughter of the Putilov factory workers who had helped to bring them to power. Today, when many people who did not live through actually existing socialism are propagating a sanitized version of events, it is essential to understand that the Bolsheviks meted out some of their bloodiest repression not to capitalist counterrevolutionaries, but to striking workers, anarchists, and fellow socialists. Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

If you find any of this difficult to believe, please, by all means, check our citations, consult the bibliography at the end, and investigate for yourself.

A note on the artwork: the artist, Ivan Vladimirov, was a realist painter who participated in the Russian Revolution, joining the Petrograd militia after the toppling of Tsar Nicholas II. He used a style of documentary realism to portray scenes from the Revolution and Civil War. Afterwards, he continued to work as an artist in good standing with the Soviet Union—such good standing that he lived into the 1940s and died of natural causes!—although he was compelled to shift to making fluff pieces lauding Soviet military triumphs and social harmony.

Bolshevik Realism

In March 1919, the Bolsheviks had uncontested power over the Russian state, but the revolution was slipping from their grasp. As self-styled pragmatists and realists, they believed that revolution had to be dictated from above by experts. Who can better understand the needs of the peasants and the proper means for communalizing the land and sharing the harvest than a revolutionary bureaucrat in an office in the city? And who knows more about the plight of the factory workers than a party official who worked in a factory once and now spends all his time going to committee meetings and interpreting the dictates of the Fathers of the Proletariat, men like Lenin, Trotsky, Kamenev, Sokolnikov, and Zinoviev who never worked in a factory or toiled in the fields in their lives?1 And who better to protect the interests of the soldiers than the political commissar who stands at the back of the line during an offensive, pistol in hand, ready to shoot anyone who does not charge into enemy fire?2

Bolshevik realism made it clear that the only way to execute a real revolution was to take over the state, make it even stronger, and use it to stamp out all their enemies—who were, by definition, counterrevolutionaries. But the counterrevolutionaries must have had secret schools in every town and village, because by 1919 more and more people were joining their ranks, especially peasants, workers, and soldiers.

The “dictatorship of the proletariat” would have to kill a whole lot of proletarians. Not everyone could make it to the Promised Land.

1919: Russians searching for food in the garbage during the lean times of the Civil War.

Enemies, Enemies Everywhere

The dastardly anarchists had corrupted the age-old revolutionary slogan, the liberation of the workers is the task of the political commissars—get back to work, it’s under control. They had replaced it with a dangerous revisionist lie—“the liberation of the workers is the task of the workers themselves”—and more and more people had come to believe this lie. In April 1918, the Bolsheviks unleashed a terror against the anarchists, who were becoming especially strong in Moscow. In September, they instituted a general Red Terror against all their former allies, killing over 10,000 in the first two months and implementing the gulag system.

They also had to turn their guns against the peasants, who were in open rebellion against the policy of “war communism” by which the Red Army and party bureaucrats could steal whatever food, livestock, and supplies from the peasants they saw fit.3 Evidently, the uneducated peasants didn’t have the vocabulary to understand that this theft was a “requisitioning,” that their starvation was a form of “communism,” and that it was being supervised by incorruptible men who had their best interests at heart. In August 1918, Lenin directed the Cheka and the Red Army to carry out mass executions in Penza and Nizhniy Novgorod to put an end to the protests. But dissent only spread, and the peasants gave up on protesting in order to arm themselves and fight back. Many formed “Green Armies,” localized peasant detachments that often fought against both the White and the Red Armies.

There was also a shortage of realism in the Red Army. Arguably, the most effective fighting units in the war against the tsarists and the capitalists of the White Army were the localized, volunteer detachments that elected and recalled their own officers; granted no special privileges to officers; defined their goals, general strategies, and organizational principles in assemblies; relied on the goodwill of local soviets to supply them; and were intimately familiar with the terrain they operated on. Such detachments included Marusya’s Free Combat Druzhina, the Revolutionary Insurgent Army, the Dvinsk Regiment, and the Anarchist Federation of the Altai. Few other detachments were able to inflict critical defeats on tsarist forces even when they were overwhelmingly outnumbered and outgunned.4 The fact that the combatants fought for a cause they believed in, were led by strategists elected on account of their abilities, and were wholeheartedly supported by the local peasants and workers enabled them to use the terrain to their advantage, fight more bravely than their opponents, innovate creative and intelligent strategies in response to developing circumstances, and transition between guerrilla and conventional warfare in a way that confounded the enemy. Such groups were instrumental in defeating General Denikin, Admiral Kolchak, and Baron Wrangel, ending the three major White offensives—not to mention capturing Moscow at the beginning of the October Revolution.

But all of these groups suffered a fatal defect. These fighters often prioritized listening to local peasants and workers and their own common soldiers over the wise dictates of the Fathers of the Proletariat emanating from the capital. Even worse, sometimes they did hear those dictates, yet still disobeyed them. And when the Party leaders, in their infinite wisdom, decided that it was necessary to massacre peasants or workers for the sake of the revolution, the detachments led by those very peasants and workers simply weren’t up to the task.

1917: Eating a dead horse.

In order to increase the efficiency of the Red Army, the wise masters of the Bolshevik Party decided to take lessons from the great militarists of history, starting with the Tsarist army. By June 1918, they had abolished all the anti-realist policies that revolutionaries had wrongheadedly introduced into the Red Army: they discontinued the election of officers by the soldiers who would serve under them, reinstituted aristocratic privileges and pay grades for officers, recruited former Tsarist officers accustomed to those privileges, and brought in political commissars to spy on the soldiers and root out any incorrect thinking. After all, rebellious idealist soldiers had toppled one regime in 1917—and without a sufficient dose of realism, they might well topple another.

The Bolsheviks had also learned from imperialist armies throughout history that sent soldiers from one end of the empire to fight rebels at the other end of the empire. This was a sentimental kindness on the part of the Bolsheviks. Psychologically, it was much easier for Korean-speaking soldiers to avoid fraternizing with Ukrainian peasants and workers near Kharkiv—and on occasion to massacre them—and for Ukrainian-speaking soldiers to avoid fraternizing with Korean peasants and workers near Vladivostok (and occasionally to massacre them, too). This strategic practice also helped keep soldiers from getting lost. A Red Army soldier from Ukraine, fighting counterrevolutionaries in Irkutsk, would be hard-pressed to obtain support from locals or find his way home without leave. That ensured that he would know to stay with his regiment rather than deserting in a fit of anti-realism. And if he did get lost, a blond, round-eyed Ukrainian would be easy to find among the locals, who could return him to the proper authorities. Good organization: this is how a successful revolution is waged!

Yet the soldiers of the Red Army weren’t educated enough to understand. A million desertions took place in a single year. Many Red Army detachments took their weapons and joined the peasants who were forming independent Green Armies. Later, huge groups would join Makhno, who was naïvely defeating the Whites without installing a dictatorship of his own. So the Bolsheviks had to be cleverer than their tsarist and imperialist mentors. They shot tens of thousands of deserters, but this age-old tactic wasn’t enough. In a burst of inspired realism, they improvised a new tactic: taking the family members of soldiers hostage, and executing the family members if deserters did not turn themselves in to be shot.5

Propaganda poster: “Deserter, I extend my hand to you. You are as much a destroyer of the Worker-Peasant State as I, a Capitalist!”

While so many of the Red Army’s bullets were ending up in the bodies of Red Army soldiers or in the uneducated brains of anti-realist peasants, too few were being fired at the White Army—and the White Army was growing, threatening the revolution on every side. The Red Army was slowly pushing back the Northern Russian Expedition of British and US troops on the Northern Dvina front, but intense fighting over the winter had failed to dislodge General Denikin from the Donbass area of eastern Ukraine. Meanwhile, a French expeditionary force had landed in Odessa, the White Army had cemented its hold on the Caucasus, and at the beginning of March, Admiral Kolchak had begun a general offensive on the eastern front, quickly capturing Ufa and continuing to gain ground.

The anarchist Black Army held the line in southern Ukraine, but their clever Bolshevik allies were starving them of weapons and ammunition, hoping the White Army would finish them off. This was an effective economization of resources on the part of the Fathers of the Proletariat. They would not have to spend time debating anarchists or making propaganda against them if the anarchists were all dead, and it was much easier to present themselves as the alternative to the confused tsarists and liberals of the White Army than it was to debate the anarchists, with their insidious lies about people being capable of liberating themselves.

The stratagem of denying resources to the Black Army was to backfire in summer 1919. After Denikin broke through the lines, he advanced so far against a helpless Trotsky that he threatened Moscow, and only a resounding success by anarchists at the Battle of Peregenovka in September 1919 cut off White supply lines, ultimately forcing Denikin to retreat. But after all, that was why the Bolsheviks had allies: it was easier not to put all the people they wanted to kill on their “enemies” list all at once, in hopes that they would first kill each other in ways that would be advantageous to the Bolsheviks.

1920: Bolshevik propaganda in the village.

Worker Resistance to the Soviet State

Let’s rewind to early 1919, when, facing so much resistance, the Bolsheviks needed more allies. They had legalized the Mensheviks after a few months of the Terror, and gotten the various anarchist detachments to focus their energies on fighting the Whites, but they still needed more support. After half a year of killing and imprisoning members of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SRs), the Bolsheviks legalized the SRs; to be fair, the previous year, the SRs had tried killing and imprisoning the Bolsheviks, after the Bolsheviks had tried to monopolize all the instruments that would allow them to kill and imprison people. The Bolsheviks had won those monopolies now, but a revolution can’t defend itself if too many of the participants are dead or in prison. They still needed help getting the common people in line working for and fighting for the Bolsheviks. The SRs had been good propagandists and considerably more popular than the Bolsheviks. Besides, it was easier to keep the SRs under their thumb when they were out in the open, with public offices in Moscow, than when they were operating underground.

The SRs decided to trust the Bolsheviks, hoping that they could regain control of the soviets or win over other revolutionary forces. But once they came out of hiding, the Cheka began periodically arresting the SR leadership, accusing them of conspiracy, and hustling them off to the gulags. The organization never regained the strength to oppose the Bolsheviks. Meanwhile, the legalization of the SRs and Mensheviks had reduced the number of enemies the Communists had to fight, and set more forces to work putting out propaganda in favor of the revolution.

The Bolsheviks still had plenty of problems. If it wasn’t bad enough that so many peasants and soldiers were rebelling, the factory workers also began to rebel. In the city of Astrakhan, the workers went on strike. Even worse, many Red Army soldiers joined them, and similar strikes began to spread in the cities of Orel, Tver, Tula, and Ivanovo. Then strikes broke out at the giant Putilov factory in Petrograd, the capital of the revolution.

The Putilov factory had built rolling stock and other products for the railways, before branching out into artillery and armaments for the military. Later, they would also manufacture the tractors that would become essential to the industrialization of Russian agriculture, after Lenin ordained the transition from war communism to the “state capitalism” of the New Economic Policy. A strike at this factory was especially embarrassing for the Bolsheviks, because the Putilov factory had been one of the origin points of the revolution. The revolution of February 1917 had sprung from four groups: rebellious military units at the front, women protesting government food rationing, sailors stationed at Kronstadt and Petrograd, and striking workers at the Putilov factory. Strikes at the Putilov factory had also been one of the sparks that caused the 1905 Revolution.

The Bolsheviks had already dealt with the Dvinsk Regiment—heroes of the revolution and a symbol of the refusal of soldiers to fight in an imperialist war—by assassinating their commander, Grachov, and disbanding the regiment. They had managed to do this quietly and out of the public eye. Later, in 1921, they would explain that in the course of the revolution, the Kronstadt sailors had somehow gone from being the staunchest defenders of revolution to become petty bourgeois individualists infiltrated by White agents. No one really believed Trotsky when he said this, but it didn’t matter.6 What was really at stake was not truth, but power; the Bolsheviks had already crushed all their other enemies, and they resolved questions about the politics of the Kronstadt sailors not by presenting facts, but by slaughtering them, as well.

But the crushing of Kronstadt was still two years in the future. In March 1919, the Bolsheviks still had plenty of enemies, and everyone was watching. The Putilov workers had some simple demands: increased food rations, as they were starving to death; freedom of the press; an end to the Red Terror; and the elimination of privileges for Communist Party members.7 What would the Bolsheviks do? Was it possible to have a revolution without starving the workers, shutting down critical newspapers, disappearing revolutionaries of other tendencies, and elevating Party members as a new aristocracy?

1920: Seeking an escaped kulak.

The Bolshevik Response

What a silly question! The Bolsheviks were realists, and their strategy relied on making the revolution by gaining control of the State. The State was the Revolution, as long as it was a Bolshevik State. They couldn’t make the State stronger without eliminating their rivals, squeezing the workers and peasants for every last drop of sweat and blood, and divvying up the wealth among themselves. Who in their right mind would become a Bolshevik unless that meant obtaining a bigger paycheck, guaranteed food rations, and a chance to move up in the world? The Communist Party needed realists. The idealists would starve. Those who were willing to say that the State was Revolution and obedience was freedom earned a chance to contribute their talents to building the new apparatus.

As for the suckers who remained workers rather than becoming Party officials, the Bolsheviks knew that the role of workers was to work. Workers who did not work were like broken machines. As any realist can tell you, when a machine breaks the only thing to do is take it out back and put a bullet in its brain.

Between March 12 and March 14, the Cheka cracked down in Astrakhan. They executed between 2000 and 4000 striking workers and Red Army deserters. Some they killed by firing squad, others by drowning them—tying stones around their necks and throwing them in the river. They had learned the latter technique from Lenin’s heroes, the Jacobins—enlightened bourgeois revolutionaries who massacred tens of thousands of peasants who weren’t educated enough to know that the commons were a thing of the past and land privatization was the way of the future.8

The Bolsheviks also killed a smaller number of members of the bourgeoisie, between 600 and 1000. The smartest of the bourgeoisie had already joined the Communist Party, recognizing it as the best way to profit in the new situation. But the stuffier bourgeois conservatives were staunchly opposed to the Bolsheviks, the anarchists, and the aristocrats, as well, though they weren’t against allying with the aristocrats. Any political system in which they could not do whatever they wanted to whomever they wanted, they called “tyranny.”

The bourgeois conservatives would also have crushed the striking workers, perhaps with hunger instead of bullets, if they had been in charge. Despite this, the Bolsheviks claimed that the striking workers had to be agents of the bourgeois order. Curiously, when anarchists had expropriated the bourgeoisie in Moscow in April, 1918, the Bolsheviks had called the anarchists “bandits” and returned the property to the bourgeois. Now, they killed bourgeois dissidents as well as striking workers—but they reserved the vast majority of the bullets for the workers.

Two days later, on March 16, the Cheka stormed the Putilov factory. They arrested 900 workers and executed 200 of them without a trial. These were pedagogical killings meant to “teach them a lesson,” educating the workers by executing their peers. The workers did not understand yet, but they would have to learn: workers were meant to work. If they had to starve, it was for the good of the proletariat.

The workers did not learn this lesson right away. At first, state repression only intensified worker opposition. According to intercepted Bolshevik cables, 60,000 workers were on strike in Petrograd alone in June 1919, three months after all the executions at the Putilov factory.9 The poor Bolsheviks had no choice but to kill even more workers and expand their gulag system to the point that it could reeducate not just thousands, but millions.

Many later Marxists unfairly blamed Josef Stalin for the USSR turning into a massive machinery of murder, but we can see the origins of that macabre evolution right here in the need of the Bolshevik authorities to kill workers in the name of workers. The entirety of the Party apparatus, from Lenin all the way down, dedicated itself to liquidating all opposition; and the entirety of this monstrous venture was ordained from the moment that the Communists decided that they were the conscious vanguard of the proletariat, that economic egalitarianism could be achieved through political elitism, and that liberatory ends justified authoritarian means.

1921: Requisitioning.

The Economic Policy of the Communist Party

Other revolutionary currents had conflicting ideas regarding the demands of workers and their instruments of self-organization. Some favored the factory councils that spontaneously arose around the February Revolution. Others favored the workers’ unions that had grown immensely in the course of 1917. Only the Bolsheviks had a realist position, changing their relationship with these structures according to which way the wind blew. As documented by Carlos Taibo,10 the Bolsheviks alternated between promoting the soviets and unions, attempting to capture them within larger bureaucratic structures controlled by the Party, eroding their powers, and suppressing them outright. Their approach varied wildly according to whether they believed that they could use these organizations to prop up their own power or feared, instead, that these organizations threatened Bolshevik supremacy. All power to the Party was their only consistent principle.

Throughout 1917, the Bolsheviks gained immense popularity by making all the right propaganda. They promised to redistribute the land directly to the peasants, to end the war without allowing imperialist Germany to annex territory, and to give the workers control of their workplaces. We have already seen how they broke the first two promises. As for their promise to the workers, they pitted different workers’ organizations against each another as they steadily strengthened their bureaucratic control.

In 1917, factory councils had sprung up in hundreds of factories throughout Russia, while membership in trade unions grew from tens of thousands to 1.5 million. At first, the Mensheviks dominated the unions and used their influence to get the unions to support the pre-October Kerensky government. According to a Trotskyist account, “As they were preparing for the seizure of power, Lenin and his followers tried to approach the trade unions from a new angle and to define their role in the Soviet system.” Promising them greater power, the Bolsheviks hoped to win union support for their project of seizing control of the State—or at least acquiescence to it.

According to two other pro-Leninist scholars, Lenin “essentially abandoned the slogan ‘All Power to the Soviets’” when he “convinced the party that the time was right to seize state power.”11 This is a fairly literal admission of fact. If the soviets were to have all the power, the Party could have none.

In November 1917, immediately after taking power, the Bolsheviks decreed that the factory committees must not participate in the direction of the companies, nor take on any responsibility in their functioning; instead, each committee was subordinated to a “Regional Council of Workers’ Control” which answered to the “All-Russian Council of Workers’ Control. The composition of these higher bodies was decided by the Party, with the trade unions receiving the majority of the seats.12

“The Revolution has been victorious. All power has passed to the Soviets… Strikes and demonstrations are harmful in Petrograd. We ask you to put an end to all strikes on economic and political issues, to resume work and to carry it out in a perfectly ordinary manner… Every man in his place. The best way to support the Soviet Government these days is to carry on with one’s job.”

-Bolshevik spokesmen at the second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, October 26 [Old Style calendar], 1917 (quoted in Maurice Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers’ Control 1917-1921)

“It is absolutely essential that all the authority in the factories should be concentrated in the hands of management… Under these circumstances any direct intervention by the trade unions in the management of enterprises must be regarded as positively harmful and impermissible.”

-Lenin speaking at the Eleventh Congress in 1922

Referring again to the Trotskyist account, “The Bolsheviks now called upon the trade unions to render a special service to the nascent Soviet state and to discipline the factory committees. The unions came out firmly against the attempt of the factory committees to form a national organization of their own. They prevented the convocation of a planned all-Russian congress of factory committees and demanded total subordination on the part of the committees.” At the end of 1917, the Bolsheviks forced the factory committees to incorporate themselves within the trade unions, in an attempt to curtail their autonomy.

1918: A shooting.

From the moment they were in power, the Bolsheviks treated workers’ councils as a threat. Why? Many Leninists, as well as the aforementioned Trotskyist, claimed that the councils were only conscious of their interests at the level of individual factories; they could not take into account the interests of the entire economy or the entire working class. This is contradicted, though, by the many examples of solidarity between soviets and workers’ councils across the country beginning already in 1917, and the fact of material support by peasants and urban workers for the anarchist detachments fighting against the White Army in the anarchist zones of Ukraine and Siberia, where idealist revolutionaries allowed workers and peasants to organize themselves. The simple fact that the factory councils were trying to coordinate at a countrywide level at the end of 1917 shows that they were in the process of developing what one might reasonably call a universal, proletarian, revolutionary consciousness; it was the Bolsheviks themselves who cut that process short.

From the Bolshevik perspective, what was most dangerous about factory council consciousness was that it might not lead to the particular kind of working-class consciousness that the Bolsheviks desperately needed to stay in power. Self-organized factories would support revolutionary armies of workers and peasants, but they probably would not support the Red Army in suppressing workers and peasants, nor would they support Lenin’s highly unpopular cession of Ukraine, Poland, and the Baltics to imperial Germany.

The councils were dangerous for another reason as well. Not only were they an organ of workers’ autonomy and self-organization that rendered any political party obsolete, they also tended to erode party discipline. Workers within the councils who were affiliated to the Mensheviks, the Bolsheviks, or any other party tended to act in accord with their common interests as factory workers rather than maintaining party interests.13

As Paul Avrich pointed out,14 the Bolsheviks made use of a nuanced distinction between two very different versions of workers’ control. Upravleniye meant direct control and self-organization by the workers themselves, but the Communist authorities refused to grant this demand. Their preferred slogan, rabochi control, did not denote anything beyond a nominal supervision of factory organization by workers. Under the system implemented by the Bolsheviks, workers participated in workplace decision-making together with the bosses, who could be the pre-Revolution capitalist owners or agents of the Party and the State, depending on Soviet policy at the moment.

All final decisions were made by the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy (the Vesenkha), an unelected, bureaucratic body established in December 1917 by decree of the Sovnarkom and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. All of these bureaucratic bodies were controlled at all times by the Bolsheviks, meaning that no worker could have a final say in workplace decisions without becoming a full-time party operative and climbing to the very highest ranks of the bureaucracy.

Already in March 1918, an assembly of factory councils in Petrograd denounced the autocratic nature of Bolshevik rule and the Bolshevik attempt to dissolve those factory councils not under Party control.15 Such autocracy only increased when the Bolsheviks finally went ahead with the nationalization of the economy in the summer of 1918, increasing Party control and running the factories with the help of “experts” recruited from the old regime.

Though there was initially an ambiguous continuum between the economically oriented factory councils and the politically oriented town or village councils, the Communist Party quickly homogenized and bureaucratized the territorial soviets, starting with codes governing elections to the soviets in March 1918 and finishing by the time of the Soviet Constitution of 1922. Even more quickly, they got rid of the councils comprising all workers in a factory or other workplace, replacing them with symbolic worker representatives completely subordinate to a director appointed by the Party.

The Communists did all of this while paying lip service to their slogan and key campaign promise of 1917, “All Power to the Soviets.” They eventually got around the contradiction of simultaneously promoting and suppressing the soviets by declaring that councils of representatives of representatives, and even those of representatives of representatives of representatives, were also “soviets.” In fact, the committee furthest removed from any actual soviet of real-life peasants, workers, and soldiers was the “Supreme Soviet.” Since the Bolsheviks tightly controlled all these higher, more bureaucratic organs of government, which they had decided should also be called “soviets,” they could say “All Power to the Soviets” with a straight face—because now all they were saying was, “All Power to Us!”

This ingenious trick was very similar to the one used by the Founding Fathers of the United States, when an assortment of wealthy merchants and slave-owners established a government “of the People, by the People, and for the People.” Slave-owners qualified as people; slaves did not.

The Bolsheviks crushed the factory councils first, though they did not wait long to sink their teeth into the unions and drain them of their independence. It is noteworthy that they moved against the unions preemptively, preventing a possible threat to totalitarian rule even before the unions had offered any sign of resistance. At the First All-Russian Congress of Trade Unions in January 1918, the Bolsheviks successfully defended their position that the trade unions should be subordinated to the Soviet government, in the face of opposition by Mensheviks and anarchists, who argued that the unions should remain independent.

The Bolsheviks were able to dominate the unions using the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions. By 1919, under the pretext of the extraordinary measures required by the Civil War, the Central Council had been fully incorporated into the bureaucracy that was now completely controlled by Party leadership.

Of course, as we have already shown, the Communist Party’s “extraordinary measures” preceded the Russian Civil War; they may have been the primary cause of the opposition and outrage that fueled the multiple and conflicting factions that fought in the Civil War.

In 1921, with the Civil War all but over and Bolshevik dominance indisputable, Lenin and his followers could do away with “war communism.” There followed more excuses about exceptional circumstances, delaying yet again the repartition of the pie in the sky that supposedly awaited the workers in paradise. The result was the New Economic Policy (NEP), which Lenin himself described as “a free market and capitalism, both subject to state control” together with state enterprises operating “on a profit basis.”16 Anarchists may have been among the first to level the accusation of “state capitalism,” but Lenin accepted the label as an objective fact.

In conclusion, the Bolsheviks seesawed from November 1917 to the NEP in 1921, changing their economic policy multiple times. Throughout these changes, they entrusted control over the workplace to capitalist bosses with symbolic worker oversight, to Party lackeys, to bureaucratic supreme committees, and to nepmen, the economic opportunists of the NEP era. It seems the only people the Bolsheviks were not willing to trust were the workers themselves.

Anti-colonial Marxist Walter Rodney, who was sympathetic to Stalin and wholly supportive of Lenin, nonetheless acknowledged that “The state, not the workers, effectively controlled the means of production.”17 He also showed how the Soviet Union inherited and furthered the Russian imperialism of the earlier tsarist regime—though that’s a topic for a future essay.

A realist knows that the best counterargument to all these sentimental complaints is the indisputable fact that, in the end, the Bolshevik strategy triumphed. They eliminated all their enemies. The idealists were dead—and therefore wrong. What better positive evidence can we find for the correctness of the Bolshevik position?

1919: in the basements of the Cheka.

The End of Resistance to Bolshevik Realism

Things immediately got better. The workers no longer had to toil for the enrichment of the capitalist class. Now they reaped the fruit of their own labors. (Except, of course, for all the workers in the free-market enterprises permitted under the NEP, and the millions of peasants who quite literally had to give away the fruits and the grains they grew.) To make things simpler, all the social wealth they reaped was kept in a trust managed by the intellectual workers. The intellectual workers worked a lot harder and required more compensation, better food, and bigger houses—but they also made sure that most of that wealth went to fielding an army of 11 million (shy by just a million of being the largest army in world history). And a damn fine opera. And one of the most extensive secret police apparatuses ever seen, too, to make sure the people stayed safe.

During Stalin’s Five Year Plans, the Soviet economy grew faster than the contemporary democratic economies and steered clear of the Depression that was ravishing much of the rest of the world. Idealistic anarchist critiques of “state capitalism” have long pointed out that the Communists were able to bring capitalism to the countries where the capitalist class had largely failed—they did capitalism better than the capitalists. But this naïve complaint misses out on the fact that a strong State, and thus a strong Revolution, requires a robust economy producing huge amounts of surplus value that can be reinvested as the Fathers of the Proletariat see fit.

Alongside all these exciting developments, the workers eventually got housing and healthcare, if they worked hard and kept their mouths shut. Provided, of course, that they weren’t among the millions of victims of the systematic famines designed to break the peasantry.

And that’s why these are such important days to remember.

On this, the one-hundred-year anniversary of the massacres of striking workers in Astrakhan and Petrograd, workers would do well to remember who has their best interests at heart, and keep in mind that obedience is freedom. To celebrate the triumph of the Bolshevik Revolution, which continues to shine as a beacon to oppressed people everywhere, workers should obey their elected union representatives, prisoners should heed their guards, soldiers should obey the command to fire, and the people should await the directives of the government. Anything else would be anarchy.

1922: A lesson on communism for the Russian peasants.

Bibliography

Paul Avrich, “Russian Anarchism and the Civil War,” The Russian Review. Vol.27 No.3: 296–306. July 1968.

Paul Avrich, The Russian Anarchists. Oakland: AK Press, 2006.

Maurice Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers’ Control 1917-1921. 1970.

Vladimir Brovkin, , “Workers’ Unrest and the Bolsheviks’ Response in 1919”, Slavic Review, 49 (3): 350–73. (Autumn 1990)

Isaac Deutscher, *Soviet Trade Unions: Their Place in Soviet Labour Policy. 1950. https://www.marxists.org/archive/deutscher/1950/soviet-trade-unions/ch02.htm

Nick Heath, “Bolshevik Repression against Anarchists in Vologda,” libcom.org October 15, 2017.

Robin D.G. Kelley and Jesse Benjamin, “Introduction,” in Walter Rodney, The Russian Revolution: A View from the Third World. London: Verso, 2018.

Piotr Kropotkin, The Great French Revolution. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1989.

Nadezhda Krupskaya, “Illyich Moves to Moscow, His First Months of Work in Moscow” Reminiscences of Lenin. International Publishers, 1970.

George Leggett. The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

V.I. Lenin, “Telegram to the Penza Gubernia Executive Committee of the Soviets” in J. Brooks and G. Chernyavskiy, Lenin and the Making of the Soviet State: A Brief History with Documents (2007). Bedford/St Martin’s: Boston and New York, p.77.

V.I. Lenin, “The Role and Functions of the Trade Unions under the New Economic Policy”, LCW, 33, p. 184., Decision Of The C.C., R.C.P.(B.), January 12, 1922. Published in Pravda No. 12, January 17, 1922. Lenin’s Collected Works, 2nd English Edition, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1973, first printed 1965, Volume 33, pp. 186–196. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/cw/pdf/lenin-cw-vol-33.pdf

Mário Machaquiero, A revolução soviética, hoje. Ensaio de releitura da revolução de 1917. Oporto: Afrontamento, 2008.

Igor Podshuvalov, Siberian Makhnovschina: Siberian Anarchists in the Russian Civil War (1918-1924). Edmonton: Black Cat Press, 2011.

James Ryan. Lenin’s Terror: The Ideological Origins of Early Soviet State Violence. London: Routledge, 2012.

Alexandre Skirda, trans. Paul Sharkey, Nestor Makhno: Anarchy’s Cossack. Oakland: AK Press, 2003.

Carlos Taibo, Soviets, Consejos de Fábrica, Comunas Rurales. Calumnia: Mallorca, 2017.

Various, A Collection of Reports on Bolshevism in Russia. London: HMSO, 1919.

Voline, The Unknown Revolution, 1917-1921. New York: Free Life Editions, 1974.

Dmitri Volkogonov, Shukman, Harold, ed., Trotsky: The Eternal Revolutionary, London: HarperCollins, p.180. 1996.

Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartosek, Jean-Louis Panne, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stephane Courtois, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Beryl Williams, The Russian Revolution 1917–1921. Boston: Wiley-Blackwell, 1987.

Additional Reading

1921-1953: A Chronology of Russian Anarchism

Ilyich Moves to Moscow, His First Months of Work in Moscow, from Krupskaya’s “Reminiscences of Lenin”

Bolshevik repression against anarchists in Vologda

April 2018: One Hundred Year Anniversary of the Beginning of Bolshevik Terror

Lenin Orders the Massacre of Sex Workers, 1918

A Century since the Bolshevik Crackdown of August 1918

Manual for Revolutionary Leaders, Michael Velli

Of the seven members of the first Politburo—Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Kamenev, Sokolnikov, Zinoviev, and Bubnov—all but Zinoviev had received elite educations and become professional activists immediately after their education. Stalin was the only one of the seven who came from a less-than-middle class background. His father was a well-to-do shoemaker who owned his own workshop, though he lost his fortunes and became an abusive alcoholic. Young Stalin was able to receive an elite religious education thanks to his mother’s social connections. His first job was as a meteorologist; he later worked briefly at a storehouse in order to organize strike actions there.

Lenin and Sokolnikov were from families of professional white-collar workers; Bubnov was from a mercantile family; Kamenev was the son of a relatively well-paid worker in the railroad industry. Trotsky and Zinoviev were the children of landowning peasants, or kulaks—the very people they identified as the class enemy in the countryside in order to justify the murder of millions, both actual kulaks and poor peasants who opposed Bolshevik policies.

Most anarchists do not believe that a person’s class background determines their beliefs and attitudes, nor that it grants or denies them legitimacy as a human being. We recognize that how we grow up affects our perspective, but we tend to place more importance on how someone chooses to live their life. A few anarchists, like Kropotkin, came from elite backgrounds, whereas many more, such as Emma Goldman and Nestor Makhno, came from working-class or peasant backgrounds.

It is nonetheless significant that practically every single anarchist who was influential in the course of the Russian Revolution or who was chosen to lead a major detachment in the Civil War was a worker or a peasant. This exemplifies the slogan of the First International, “the liberation of the workers is the task of the workers themselves.” (The only exception was Volin, who came from a white-collar background.) It is also significant that, while the Bolsheviks recruited heavily among industrial workers, their entire Politburo was 0% working class.

Given both Marx and Lenin’s systematic use of their adversaries’ class identity—real or perceived—to delegitimize them or even justify murdering them, the fact that neither Marx nor Lenin nor the rest of the Communist leadership were working class is hypocritical to say the least. ↩

On the “blocking units” that did this, see Volkogonov, Dmitri (1996), Shukman, Harold, ed., Trotsky: The Eternal Revolutionary, London: HarperCollins, p.180. ↩

Brovkin, Vladimir (Autumn 1990), “Workers’ Unrest and the Bolsheviks’ Response in 1919”, Slavic Review, 49 (3): 350–73 ↩

Alexandre Skirda, trans. Paul Sharkey, Nestor Makhno: Anarchy’s Cossack. Oakland: AK Press, 2003 ↩

Beryl Williams, The Russian Revolution 1917–1921. Boston: Wiley-Blackwell, 1987. ↩

Even before Stalin, the Bolsheviks spread lies not so much to convince people of them as to force them to repeat the lies. This was an effective loyalty test: anyone who insisted on speaking the truth was clearly a dangerous counterrevolutionary, whereas those who called starving peasants “kulaks” or denounced principled revolutionary sailors as “White agents” had accepted Communist realism. ↩

“We, the workmen of the Putilov works and the wharf, declare before the laboring classes of Russia and the world, that the Bolshevik government has betrayed the high ideals of the October revolution, and thus betrayed and deceived the workmen and peasants of Russia; that the Bolshevik government, acting in our name, is not the authority of the proletariat and peasantry, but the authority of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, self-governing with the aid of the Extraordinary Commissions [Chekas], Communists, and police.

“We protest against the compulsion of workmen to remain at factories and works, and attempts to deprive them of all elementary rights: freedom of the press, speech, meetings, and inviolability of person.

“We demand:

Immediate transfer of authority to freely elected Workers’ and Peasants’ soviets. Immediate re-establishment of freedom of elections at factories and plants, barracks, ships, railways, everywhere.

Transfer of entire management to the released workers of the trade unions.

Transfer of food supply to workers’ and peasants’ cooperative societies.

General arming of workers and peasants.

Immediate release of members of the original revolutionary peasants’ party of Left Socialist Revolutionaries.

Immediate release of Maria Spiridonova [a Left SR leader].”

↩

Piotr Kropotkin, The Great French Revolution. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1989. p.454-458 ↩

Document no. 54, “Summary of a Report on the Internal Situation in Russia,” in A Collection of Reports on Bolshevism in Russia, abridged ed. Parliamentary Paper: Russia no. 1 [London: HMSO, 1919], p.60 ↩

Carlos Taibo, Soviets, Consejos de Fábrica, Comunas Rurales. Calumnia: Mallorca, 2017 ↩

Robin D.G. Kelley and Jesse Benjamin, “Introduction,” in Walter Rodney, The Russian Revolution: A View from the Third World. London: Verso, 2018. ↩

Maurice Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers’ Control 1917-1921. 1970. p.65

“Once power had passed into the hands of the proletariat, the practice of the Factory Committees of acting as if they owned the factories became anti-proletarian.” -A.M. Pankratova, Fabzavkomy Rossil v borbe za sotsialisticheskuyu fabriku (Russian Factory Committees in the struggle for the socialist factory). Moscow, 1923 ↩

Mário Machaquiero, A revolução soviética, hoje. Ensaio de releitura da revolução de 1917. Oporto: Afrontamento, 2008. p.144. ↩

Paul Avrich, The Russian Anarchists. Oakland: AK Press, 2006. p.147 ↩

Carlos Taibo, Soviets, Consejos de Fábrica, Comunas Rurales. Calumnia: Mallorca, 2017. p.58 ↩

V.I. Lenin, “The Role and Functions of the Trade Unions under the New Economic Policy”, LCW, 33, p. 184., Decision Of The C.C., R.C.P.(B.), January 12, 1922. Published in Pravda No. 12, January 17, 1922. Lenin’s Collected Works, 2nd English Edition, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1973, first printed 1965, Volume 33, pp.186–196. ↩

Robin D.G. Kelley and Jesse Benjamin, “Introduction,” in Walter Rodney, The Russian Revolution: A View from the Third World. London: Verso, 2018. p.lvi ↩

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

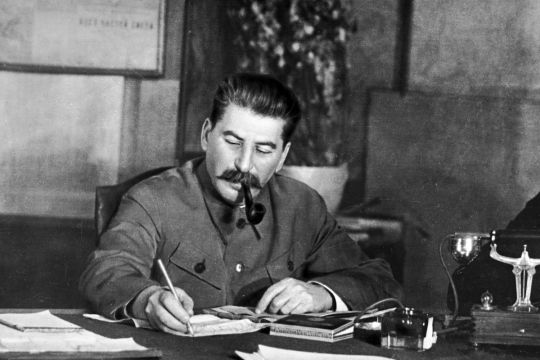

soviet leadership: stalin

Key points:

Editor of Pravda

Commissar of Nationalities

Defended Tsaritsyn

A lot of beef with Trotsky

Head of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate; gained experience in many areas of Soviet leadership

Trusted by Lenin, or at least until Lenin was unable to work then had time to contemplate his regime

Headed the Orgburo

Elected to Politburo

Became the Bolsheviks’ General Secretary in 1922

Everyone else felt “meh” about him until it was too late

In detail:

Georgian boi

Born Joseph Dzhugashvili

Had a genuine working class background: maternal grandparents were religious serfs, father a shoemaker

Got whacked my his mom a lot for being disobedient, but did well in school and went to a seminary to become a priest

But more drawn to Marxism than God

Wrote pamphlets & attended secret revolutionary meetings

Loved Lenin’s writings <3 and became a revolutionary

Organized strikes, bank raids, etc.

Fun fact: “Koba” was Stalin’s pseudonym

1902-13: got arrested frequently --> Siberia!

Big guy still managed to escape like 5 times

Became more hardened after death of first wife in 1907

Took pseudonym “Stalin”

1912: invited to Bolshevik Central Committee that was lacking in working class members / other members still in exile

Involved in Feb. 1917, but did not play key role in Oct.

Trotsky and Sverdlov were key players in the Oct. Rev.

Sverdlov didn’t like Stalin

Editor of Pravda

Held Executive Committee seat in the Petrograd Soviet

Initially pro-war, but after Lenin’s rise to power he supported Lenin

After the Oct. Rev. --> Commissar of Nationalities

Sent to Tsaritsyn (Stalingrad) during the Civil War

Organized food supplies

Heroically defended Tsaritsyn

Didn’t like taking Trotsky’s orders; removed from military post for disobedience

When Sverdlov died in 1919, Stalin became the head of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate

May 1919: Stalin in charge of Orgburo and elected to Politburo

1922: became Party’s General Secretary

Suggests that Lenin trusted Stalin

Gained a reputation for “industrious mediocrity” as other Bolsheviks saw Stalin’s roles as part of party bureaucracy routines

Stalin in the seminary reading Communist literature:

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scheer Orders a Final Attack on the Royal Navy

Admiral Reinhard Scheer (1863-1928), Chief of the German Naval Staff from August 1918; he had previously commanded the High Seas Fleet, including at Jutland.

October 22 1918, Wilhelmshaven--The German army may have been quickly running out of men and losing the war on land, but the navy was still very much intact. After Prince Max ended unrestricted submarine warfare, which navy leaders had long held as the best hope of victory against the Allies (despite mounting evidence to the contrary), Scheer decided to make use of his “fleet in being” one last time, sortieing from Wilhelmshaven for a final confrontation with the Grand Fleet. He had obliquely mentioned this possibility to the Kaiser during the cabinet meeting on the 17th, saying that the end of submarine warfare meant that the High Seas Fleet would again have “complete freedom of action.” The Kaiser did not react to this, which Scheer interpreted as tacit approval, and he did not mention his plans to the Chancellor. Scheer would later state that “I did not regard it necessary to obtain a repetition of the Kaiser’s approval. In addition, I feared that this could cause further delay and was thus prepared to act on my own responsibility.”

On October 22, one of Scheer’s subordinates arrived in Wilhelmshaven in person and gave the following order to Admiral Hipper: “The High Seas Fleet is directed to attack the English fleet as soon as possible.” There was no written order, all part of Scheer’s effort to hide the plan not just from the British, but from his own government as well.�� Scheer hoped that “a tactical success might reverse the military position and avert surrender,” and even if it did not, “an honorable battle by the fleet--even if it should be a fight to the death--will sow the seed for a new German fleet of the future.”

Hipper came up with the details of the plan over the next two days. It was similar to other German sorties in the past, hoping to draw the Grand Fleet over German U-boats and mines before the surface fleet attacked. The lure was to be a bombardment of the recently-abandoned Belgian coast, along with raids deep into the Thames estuary. If the submarines did not find their targets, Scheer and Hipper were determined to engage the British anyway, even if heavily outnumbered. If the two fleets somehow missed each other (as they had before), every destroyer would be sent towards the Firth of Forth and, upon finding the Grand Fleet, would launch their torpedoes at least three at a time. The plan had a reasonable chance of dealing considerable damage to the Royal Navy--though whether the High Seas Fleet’s sailors would be willing to carry out the plan remained to be seen.

Today in 1917: Petrograd Soviet Prepares “Revolutionary Committee of Defense” Today in 1916: Romanians Surrender Constanța Today in 1915: French Engage Bulgarians While British Stay in Salonika Today in 1914: Germans Cross the Yser

Sources include: Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel.

#wwi#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#world war 1#world war i#world war one#the first world war#the great war#High Seas Fleet#Grand Fleet#scheer#Hipper#gotterdammerung#october 1918

106 notes

·

View notes

Link

“ I. A special kind of policeman

The Okhrana took over in 1881 from the notorious Third Section of the Ministry of the Interior. But it only really developed after 1900, when a new generation of police was put in charge. The old officers of the constabulary, in particular the higher ranks, had considered it contrary to military honour to occupy themselves with certain aspects of police business. The new school overrode such scruples, and undertook to organise the secret police on a scientific basis, to carry out provocation, informing and betrayal inside the revolutionary parties. It was to produce talented, erudite men like the Colonel Spiridovich who has left us a voluminous History of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party and a History of the Social-Democratic Party.

Special attention was given to the recruitment, education and professional training of the officers of this police force. At police headquarters, a file was kept on each man, thoroughly documented and including many interesting details. Character, level of education, intelligence and service record were all noted down in an eminently practical spirit. One officer, for example, is described as “limited” – all right for secondary jobs, only requiring firm handling; while another, the file points out, is “inclined to pay court to the ladies”.

Among the many questions on the form, the following are particularly striking: “Does he have a good knowledge of the statutes and programmes of any of the parties? Which parties?” We find that our friend who runs after the ladies “has a good knowledge of Socialist- Revolutionary and anarchist ideas – a passable knowledge of the Social-Democratic Party – and a superficial knowledge of the Polish Socialist Party.” Note the careful grading of learning. But let us carry on examining this same file. Has our policeman “followed courses in the history of the revolutionary movement?” “In which parties has he had secret agents working? How many? Are they intellectuals? Workers?”

Naturally, to train its experts, the Okhrana organised courses in which each party was studied – its origins, its programme, its methods, and even the life-histories of its better-known members.

It should be noted that this Russian police force, trained to do the most sensitive political police work, no longer had anything in common with the local constabularies of Western European countries. Its equivalent is to be found in the secret police of all capitalist states.

...

III. The secrets of provocation

The most important section of the Russian police was unquestionably its “secret service”, a polite name for the provocation agency, whose origins go back to the first revolutionary struggles, developing to an extraordinary degree after the 1905 revolution.

Only policemen (force officers) who had undergone special training, instruction and selection were engaged in the recruitment of agents provocateurs. Their degree of success in this field was taken into account in grading and promoting them. Precise instructions established the very finest details of their relations with their secret collaborators. Finally, highly paid specialists collated all the information supplied by the provocateurs, studied it, sorted it out and cataloged it in reports.

At the Okhrana buildings (16 Fontanka, Petrograd), there was a secret room entered only by the chief of police and the officer in charge of sorting documents. It was the centre of the secret service. Its basic contents consisted of the filing system on the provocateurs, in which we found over 35,000 names. In most cases, though an excess of precautions, the name of the “secret agent” was replaced by a pseudonym.

When, after the triumph of the revolution, these reports fell in their entirety into the comrades’ hands, this made the identification of many of these wretches particularly difficult. The name of the provocateur was to be known to no one but the head of the Okhrana and the officer responsible for maintaining permanent contact with him. Generally only pseudonyms were used, even when the provocateurs signed the monthly receipts for their salaries, which were paid as normally and regularly as to other state employees, for sums ranging from 3, 10 or 15 roubles a month up to a maximum of 150 or 200. But the administration, distrustful of its agents and anxious that police officers should not invent imaginary collaborators, often carried out detailed investigations to check on different branches of their organisation. A fully authorised inspector personally checked up on secret collaborators, interviewed them at his discretion, and either sacked them or gave them a rise. We should add that reports from such inspectors were, as far as possible, carefully checked out against each other.

...

VII. A ghost from the past

Even today we are far from having identified all the agents provocateurs of the Okhrana whose files we now have.

Not a month passes without the revolutionary tribunals of the Soviet Union passing judgement on some of these men. They are met and identified by chance. In 1924, one such wretch appeared, coming back to us from a fifty-year past as though with a sudden rush of nausea – he was a real ghost. This spectre called to mind a page of history, which we insert here simply to project into these sordid pages a little of the light of revolutionary heroism.

This agent provocateur had given 37 years’ good service (from 1880 to 1917) and, even as an old man, was wily enough to give the Cheka the slip for seven whole years.

... Around 1879, the 20-year-old student Okladsky, a revolutionary from the age of 15; a member of the Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will) Party, and a terrorist, planned an attempt on the life of Tsar Alexander II together with Zheliabov. They were going to blow up the imperial train. It passed over the mines without incident. The infernal package had not worked. An accident? So it was thought at the time. But 16 revolutionaries, including Okladsky, had to answer for this “crime”. Okladsky was condemned to death. Was this the beginning of his brilliant career? Or had it already begun? A pardon from the emperor commuted his sentence to life imprisonment.

It was in any case the beginning of the series of inestimable services Okladsky was to render to the Tsarist police. In the long list of revolutionaries he was to hand over, were four names which are among the finest in our history: Barannikov, Zheliabov, Trigoni and Vera Figner. Of these four, only Vera Nicolaevna Figner survived. She spent twenty years in the Schlüsselberg fortress. Barannikov died there. Trigoni, after suffering twenty years in Schlüsselberg and four in exile in Sakhalin, lived just long enough to see the overthrow of the autocracy before his death in June 1917. Zheliabov died on the gallows.

All these brave figures were leaders of Narodnaya Volya, the first Russian revolutionary party, which, before the birth of the proletarian movement, had declared war on the autocracy. Their programme was for a liberal revolution, which if achieved would have been an enormous step forward for Russia. In a period in which no other action was possible, they employed terrorism, constantly striking at the head of Tsarism, driving it mad sometimes, and on March 1, 1881, beheading it. In the struggle of this handful of heroes against the powerfully-armed old society, were forged the customs, traditions and outlook which, carried forward by the proletariat, were to temper many generations for the victory of October 1917.

Of all these heroes, perhaps the greatest was Alexander Zheliabov, and it was certainly he who rendered the greatest services to the party he had helped to found. Denounced by Okladsky, he was arrested on February 27, 1881, in an apartment on the Nevsky Prospekt, in the company of a young lawyer from Odessa, Trigoni, also a member of the mysterious Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya. Two days later, the party’s bombs blew Alexander II to pieces in a St Petersburg street. The following day, the legal authorities received an astounding letter from Zheliabov, jailed in the Peter and Paul prison. Rarely has a judiciary and a monarchy met with such defiance. Rarely has the leader of a party carried out his last duty with such pride. The letter said:

“If the new sovereign, who receives his sceptre from the hands of the revolution, plans to give the regicides the same punishment as of old; if he plans to execute Ryssakov, it would be a crying injustice to spare my life, since I have made so many attempts on the life of Alexander II, and only chance prevented my participation in his execution. I am very concerned that the government may be putting a higher price on formal justice than on real justice, and adorning the crown of the new monarch with the corpse of a young hero, solely for lack of formal proof against myself, a veteran of the revolution.

With all my heart I protest against this iniquity.

Only cowardice on the part of the government could explain why two gallows should not be raised instead of one.”