#Parham House and Gardens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Parham House and Gardens in West Sussex

Parham Park is an Elizabethan house and estate in the civil parish of Parham, west of the village of Cootham between Storrington and Pulborough in West Sussex. It is a great place to visit and we have visited it on many occasions including with some of our friend families from within Brighton and Hove. It is a home that provided people during World War 2 and it has a lovely range of locations…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In Parham House's Walled Garden, West Sussex, England. July 2016.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Harking back to an August day at Parham House. Bountiful borders and dawn light casting soft highlights ~ Clive Nichols

456 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parham House & Gardens.

#Parham House & Gardens#sussex#elizabethan#parham#king henry viii#park#house aesthetic#house#alternative#aesthetic#dark academia#dark academic aesthetic#dark#dark aesthetic#aestheitcs#art#light acadamia aesthetic#light academia#interiors

2K notes

·

View notes

Video

Parham House & Gardens - West Sussex by Mark

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Parham House

#myphotography#parham house#england#greenhouse#garden#plants#flowers#summer house#summer#photography#nature#popular

482 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Inner Garden Villa in #Tehran, Iran by 123DV Modern Villas @123dvarchitects. Read more: Link in bio! Photography: Parham Taghioff @parhamtaghioff. 123DV Modern Villas: This 1400 m2 high-end freestanding villa in Tehran is built against a mountainside, with a garden that is raised 17 meters above street level. The facade is cladded with natural travertine stone: a famous high quality local product collected from the Iranian mountains. The wish of the owners to park their cars underground, resulted in a 20 meter long tunnel below the garden, leading towards the parking underneath the villa… #casa #iran #архитектура www.amazingarchitecture.com ✔ A collection of the best contemporary architecture to inspire you. #design #architecture #amazingarchitecture #architect #arquitectura #luxury #realestate #life #cute #architettura #interiordesign #photooftheday #love #travel #construction #furniture #instagood #fashion #beautiful #archilovers #home #house #amazing #picoftheday #architecturephotography #معماری (at Tehran, Iran) https://www.instagram.com/p/CfKFMx6uJ5Y/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#tehran#casa#iran#архитектура#design#architecture#amazingarchitecture#architect#arquitectura#luxury#realestate#life#cute#architettura#interiordesign#photooftheday#love#travel#construction#furniture#instagood#fashion#beautiful#archilovers#home#house#amazing#picoftheday#architecturephotography#معماری

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

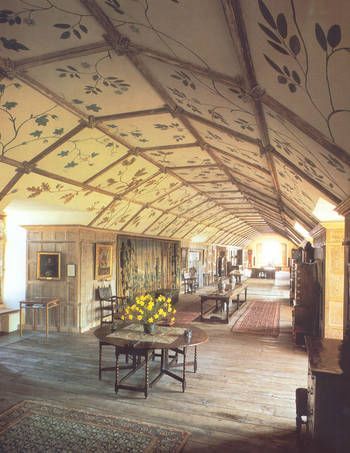

Parham House

Parham House is located in the civil parish of Parham in West Sussex, England. The Elizabethan mansion was built in 1577 upon an estate originally owned by the Monastery of Westminster, but it was granted to Robert Palmer by King Henry VII. Palmer sold the house to the Bysshopp family in 1601. The Bysshopp descendants owned the estate until 1826 when the Pearson family purchased it. The Pearson family spent 60 years restoring the home and filling it with collections of furniture, paintings, textiles, 17th century needlework, and more. During WWII, the house became the home for 30 children evacuated from Peckham in London, after which the War Department requisitioned the estate for Canadian billeting officers. The family continued to live in half of the house, while many of the soldiers were housed in the park’s Nissan huts. The Pearson’s opened the house to the public in 1948. The mansion sits on 300 acres with a four-acre walled garden, a glasshouse, an orchard, a vegetable garden, a garden shop and nursery, a restaurant, a gift shop, and a 1920s playhouse for children. The fallow deer on the property are said to descend from the first herd ever recorded. Parham serves as a family home and is open to the public, but it is currently closed until Easter 2021.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#parham #westsussex #inbloom #flowers #flowerphotography (at Parham House and Gardens) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ch6gVUns2sY/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Great British Gardens -Parham house

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

FUTURE PLANET

The Ancient Persian Way to Keep Cool

— By Kimiya Shokoohi | 10th August 2021

From ancient Egypt to the Persian Empire, an ingenious method of catching the breeze kept people cool for millennia. In the search for emissions-free cooling, the "wind catcher" could once again come to our aid.

The city of Yazd in the desert of central Iran has long been a focal point for creative ingenuity. Yazd is home to a system of ancient engineering marvels that include an underground refrigeration structure called yakhchāl, an underground irrigation system called qanats, and even a network of couriers called pirradaziš that predate postal services in the US by more than 2,000 years.

Among Yazd's ancient technologies is the wind catcher, or bâdgir in Persian. These remarkable structures are a common sight soaring above the rooftops of Yazd. They are often rectangular towers, but they also appear in circular, square, octagonal and other ornate shapes.

Yazd is said to have the most wind catchers in the world, though they may have originated in ancient Egypt. In Yazd, the wind catcher soon proved indispensable, making this part of the hot and arid Iranian Plateau livable.

Though many of the city's wind catchers have fallen out of use, the structures are now drawing academics, architects and engineers back to the desert city to see what role they could play in keeping us cool in a rapidly heating world.

The openings of the towers face the prevailing wind, catching it and funneling it down to the interior below (Credit: Alamy)

As a wind catcher requires no electricity to power it, it is both a cost-efficient and green form of cooling. With conventional mechanical air conditioning already accounting for a fifth of total electricity consumption globally, ancient alternatives like the wind catcher are becoming an increasingly appealing option.

There are two main forces that drive the air through and down into the structures: the incoming wind and the change in buoyancy of air depending on temperature – with warmer air tending to rise above cooler, denser air. First, as air is caught by the opening of a wind catcher, it is funneled down to the dwelling below, depositing any sand or debris at the foot of the tower. Then the air flows throughout the interior of the building, sometimes over subterranean pools of water for further cooling. Eventually, warmed air will rise and leave the building through another tower or opening, aided by the pressure within the building.

The shape of the tower, alongside factors like the layout of the house, the direction the tower is facing, how many openings it has, its configuration of fixed internal blades, canals and height are all finely tuned to improve the tower's ability to draw wind down into the dwellings below.

Some of the earliest wind-catching technology comes from Egypt 3,300 years ago

Using the wind to cool buildings has a history stretching back almost as long as people have lived in hot desert environments. Some of the earliest wind-catching technology comes from Egypt 3,300 years ago, according to researchers Chris Soelberg and Julie Rich of Weber State University in Utah. Here, buildings had thick walls, few windows facing the Sun, openings to take in air on the side of prevailing winds and an exit vent on the other side – known in Arabic as malqaf architecture. Though some argue that the birthplace of the wind catcher was Iran itself.

Wherever it was first invented, wind catchers have since become widespread across the Middle East and North Africa. Variations of Iran's wind catchers can be found in the barjeels of Qatar and Bahrain, the malqaf of Egypt, the mungh of Pakistan, and many other places, notes Fatemeh Jomehzadeh of the University of Technology Malaysia and colleagues.

Due to long disuse, many of Iran's windcatchers are not in a good state of repair. But some researchers would like to see them restored to working order (Credit: Alamy)

The Persian civilisation is widely considered to have added structural variations to allow for better cooling – such as combining it with its existing irrigation system to help to cool the air down before releasing it throughout the home. In Yazd's hot, dry climate, these structures proved remarkably popular, until the city became a hotspot of soaring ornate towers seeking the desert wind. The historical city of Yazd was recognised as a Unesco World Heritage site in 2017, in part for its proliferation of wind catchers.

As well as performing the functional purpose of cooling homes, the towers also had a strong cultural significance. In Yazd, the wind catchers are as much a part of the skyline as the Zoroastrian Fire Temple and Tower of Silence. Among them is the wind catcher at the Dowlatabad Abad Gardens, said to be the tallest in the world at 33m (108ft) and one of the few wind catchers still in operation. Housed in an octagonal building, it overlooks a fountain stretching past rows of pine trees.

Inconveniences like pests entering the chutes and the gathering of dust and desert debris have meant many have turned away from traditional wind catchers

The emissions-free cooling efficacy of such wind catchers make some researchers argue that they are due a revival.

Parham Kheirkhah Sangdeh has extensively studied the scientific application and surrounding culture of wind catchers in contemporary architecture at Ilam University in Iran. He says inconveniences like pests entering the chutes and the gathering of dust and desert debris have meant many have turned away from traditional wind catchers. In their place are mechanical cooling systems, such as conventional air-conditioning units. Often, those options are powered by fossil fuels and use refrigerants that act as powerful greenhouse gases if released into the atmosphere.

The wind catchers of Iran have inspired modern designs in Europe, the US and elsewhere, as architects turn towards passive forms of cooling (Credit: Alamy)

The advent of modern cooling technologies has long been blamed for the deterioration of traditional methods in Iran, the historian of Iranian architecture Elizabeth Beazley wrote in 1977. Without constant maintenance, the harsh climate of the Iranian Plateau has worn away many structures from wind catchers to ice houses. Kheirkhah Sangdeh also sees the shift away from wind catchers as in part down to a tendency among the public to engage with technologies from the West.

"There needs to be some changes in cultural perspectives to use these technologies. People need to keep an eye on the past and understand why energy conservation is important," Kheirkhah Sangdeh says. "It starts with recognising cultural history and the importance of energy conservation."

Kheirkhah Sangdeh hopes to see Iran's wind catchers updated to add energy-efficient cooling to existing buildings. But he has met many barriers to his work in the form of ongoing international tensions, the coronavirus pandemic and ongoing water shortage. "Things are so bad in Iran that [people] take it day by day," says Kheirkhah Sangdeh.

Yazd is said to have the most wind catchers of any city in the world (Credit: Alamy)

Fossil-fuel-free methods of cooling like the wind catcher might well be due a revival, but to a surprising extent they are already present – albeit in a less magnificent form than those in Iran – in many Western countries.

In the UK, some 7,000 variations of wind catchers were installed in public buildings between 1979 and 1994. They can be seen from buildings such as the Royal Chelsea Hospital in London, to supermarkets in Manchester.

These modernised wind catchers bear little resemblance to Iran's towering structures. On one three-storey building on a busy road in north London, small hot pink ventilation towers allow passive ventilation. Atop a shopping centre in Dartford, conical ventilation towers rotate to catch the breeze with the help of a rear wing that keeps the tower facing the prevailing wind.

The US too has adopted wind-catcher-inspired designs with enthusiasm. One such example is the visitor center at Zion National Park in southern Utah. The park sits in a high desert plateau, comparable to Yazd in climate and topography, and the use of passive cooling technologies including the wind catcher nearly eliminated the need for mechanical air-conditioning. Scientists have recorded a temperature difference of 16C (29F) between the outside and inside of the visitor centre, despite the many bodies regularly passing through.

There is further scope for the spread of the wind catcher, as the search for sustainable solutions to overheating continues. In Palermo, Sicily, researchers have found that the climate and prevailing wind conditions make it a ripe location for a version of the Iranian wind catcher. This October, meanwhile, the wind catcher is set to have a high-profile position at the World Expo fair in Dubai, as part of a network of conical buildings in the Austrian pavilion, where the Austrian architecture firm Querkraft has taken inspiration from the Arabic barjeel version of the wind tower.

While researchers such as Kheirkhah Sangdeh argue that the wind catcher has much more to give in cooling homes without fossil fuels, this ingenious technology has already migrated further around the world than you might think. Next time you see a tall vented tower on top of a supermarket, high-rise or school, look carefully – you might just be looking at the legacy of the magnificent wind catchers of Iran.

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view.

0 notes

Text

Seventy Peaks Multipurpose Complex

Seventy Peaks Multipurpose Complex Iran, Central Iranian Building Images, Qom-Arak highway design

Seventy Peaks Multipurpose Complex Design

Contemporary Sorkhrood Residential Building design by Habibeh Madjdabadi Architects

18 September 2021

Design: Habibeh Madjdabadi Architecture Studio

Location: by Qom-Arak highway, central Iran

Seventy Peaks Multipurpose Complex, Iran

The complex, with its 10,000 m2 of the built area is born as a commercial center including restaurants, café, and hotels for travelers. It is located on a plot of 60,000 m2, next to the highway that connects the holy city of Qom to Arak (in the central region of Iran).

70 peaks project, in line with the recent projects of the Iranian architect: Barjeel museum in UAE and Lunar retail and accommodation center in Iran. The name comes from the homonymous protected natural reserve located next to the complex.

The building, with its curvilinear shapes, small windows, and board-like roof, resembles a cruise ship floating in an ocean of soil. Its strange form takes inspiration from the morphology of the land and the traditional architecture of central Iran.

The nozzle-shape skylights and the widely cantilevered roof that flexes downward to the ground, recalls the vernacular architecture of the central region of Iran. Its spatial organization is encouraging the visitors to enter the complex or to climb it up and use the roof as a public plaza.

The big apertures in the frontal and lateral facades create generously protected and inviting ingresses, which are rooted in Iranian architecture traditions. The inner courtyard, with its regular rectangular shape and symmetrical organization, creates a tension between the internal and external forms of the building which is typically Iranian.

The axial organization of the complex is based on rectangular layout and sub-divisions. It extends from north to south and generates both building spaces and their surrounding site. The main entrance is located in the north, close to the highway. A green landscape with pounds and trees creates a buffer between the building and the intense traffic of the main access road. Despite its apparently simple plan, the spatial organization is rather complex and provides a multitude of views and unexpected scenarios.

The northern wing is dedicated to the main lobby, administrative offices, and a restaurant on the upper floor. The east and west side wings house shops and commercial spaces, facing the site and the inner courtyard. A pedestrian ring, connects the aforesaid wings at the first floor, passing over the main entrance and landing to the ground, through comfortable ramps, on both west and east sides of the building. The southern side of the complex is dedicated to hotels and restaurants.

An underground tunnel, with the function of an art gallery, originates from the courtyard and passes under the southern wing of the complex for emerging from the middle of the pond and passing in the middle of the southern garden. This gallery and its extension as a walkway reinforce the main axis of the garden. When moving along the gallery and walkway on the south-north axis the tallest nozzle-shape skylight acts as an axial lighthouse for the visitors

The project includes recreational spaces, cafes, restaurants, commercial spaces, and residences. In the south side garden, there are two fountains, a fish storage pool, and a large greenhouse for growing organic food, which is used by the restaurants of the complex. The landscape also includes green space, pedestrian and bicycle paths, children’s play areas, and parking.

Seventy Peaks Multipurpose Complex – Building Information

Architect: Habibeh Madjdabadi Client: Javad Nouri Plot area: 60000 sqm Built area: 10000 sqm Design year: 2021 Location: Qom-Arak highway, Iran Modeling & Presentation team: Shadi Torkamanpari, Mehrnesa Khani, Negar Asadimehr

Seventy Peaks Multipurpose Complex Iran images / information from Habibeh Madjdabadi Architects

Location: Caspian Sea coast, North Iran

Iranian Architecture

Iran Architecture Designs – chronological list

Iranian Architecture News

Iranian Architecture

Vertical Village 10+10, Sorkhrood, southern coast of Caspian Sea, Northern Iran Design: Habibeh Madjdabadi Architecture Studio image Courtesy architecture office Vertical Village 10+10, Caspian Sea Apartment

A monumental Entrance Gate for The Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, Tehran Province Design: Habibeh Madjdabadi Architect image Courtesy architecture office Entrance Gate for The Atomic Energy Organization of Iran

Lunar Complex Loshan Building Architects: Habibeh Madjdabadi image Courtesy architecture office

House in Mosha, Damavand County, Tehran Province photograph : Parham Taghioff

Residential Complex of Meygoon Design: New Wave Architecture photograph : Parham Taghioff

Tehran Design Competition

Comments / photos for the Seventy Peaks Multipurpose Complex page welcome

Website: Habibeh Madjdabadi Architect Iran

The post Seventy Peaks Multipurpose Complex appeared first on e-architect.

0 notes

Photo

Adrian Sassoon Gallery collaboration with @parham_house_gardens in West Sussex. @elizabethfritschart studio selected left to right: Spout Pot (h32cm), Vase - Doubling the tempo (h44cm), Pyramid (h24cm). #elizabethfritsch unique hand-built stoneware with coloured slips. Availability via Adrian Sassoon @adrian_sassoon_gallery . . . . . . . #museum #contemporaryart #collector #group #spout #handbuilt #fresco #pyramid #britishart #artstudio #makesyouthink #ceramic #art #artist #lizfritsch #handmade #form #vase #vessel #potter #contemporaryceramics #surface #painted #painting #design #raga #time #tempo #pattern (at Parham House and Gardens) https://www.instagram.com/p/CR3l2NoDpPr/?utm_medium=tumblr

#elizabethfritsch#museum#contemporaryart#collector#group#spout#handbuilt#fresco#pyramid#britishart#artstudio#makesyouthink#ceramic#art#artist#lizfritsch#handmade#form#vase#vessel#potter#contemporaryceramics#surface#painted#painting#design#raga#time#tempo#pattern

0 notes

Photo

"Parham House & Garden" by Mark Wordy, Sussex, Great Britain.

3K notes

·

View notes

Video

Parham House & Gardens - West Sussex by Mark

0 notes

Photo

...like a secret garden... Parham is an amazing hidden gem, and one of the most tranquil and beautiful spaces I’ve ever spent time in... . . . . . #getoutside #exploremore #theglobewanderer #letsgosomewhere #optoutside #travelstoke #lensculture #exploremore #lifestyleblog #thehappynow #storytelling #makemoments #lovegreatbritain #visitengland #photosofengland #photosofbritain #englandtourism #rsa_nature #kings_flora #floralfix #ig_flowers #floral_secrets #gardendesign #gardening #secretgarden #secretgardens #chiaroscuro #gardening #gardenlife #gardenlifestyle (at Parham House and Gardens) https://www.instagram.com/p/B0wUem5hXaJ/?igshid=1lv29oljab9l5

#getoutside#exploremore#theglobewanderer#letsgosomewhere#optoutside#travelstoke#lensculture#lifestyleblog#thehappynow#storytelling#makemoments#lovegreatbritain#visitengland#photosofengland#photosofbritain#englandtourism#rsa_nature#kings_flora#floralfix#ig_flowers#floral_secrets#gardendesign#gardening#secretgarden#secretgardens#chiaroscuro#gardenlife#gardenlifestyle

0 notes