#Oncorhynchus kisutch

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

SALMONIDS of ALASKA The bane of my existence for the entirety of 2020 and part of 2021: the salmon poster. You've seen the separate illustrations, but now, finally, here is the full thing.

This entire project was a journey. I had never illustrated fish before, let alone in this much detail. I have retained an appropriate hatred of scales and fin rays from this project. But also a persistent joy from having created these illustrations, and appreciation for what beautiful animals these salmon are. Putting together the poster, making all elements fit together and - not unimportantly - making the poster fit its allotted space on the wall was an additional endeavour.

It is currently displayed aboard the David B, the vessel of Northwest Navigation who commissioned this piece. If you're interested in having a copy of your own, you can contact them. For now I hope you enjoy reading this (if you open the image in a separate tab, I made it big enough to read) - and mayhaps learn something new about the intriguing world of salmon! I certainly did.

#poster#illustrations#scientific illustration#Salmonids of Alaska#Salmonid#Alaska#Chinook salmon#Oncorhynchus tshawytscha#Coho salmon#Oncorhynchus kisutch#Chum salmon#Oncorhynchus keta#Pink salmon#Oncorhynchus gorbuscha#Sockeye salmon#Oncorhynchus nerka#Steelhead#Oncorhynchus mykiss#Coastal cutthroat#Cutthroat trout#Oncorhynchus clarkii#salmon#trout#digital art

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

The world is pretty shitty right now, but the salmon I am raising are learning to swim so it can't be all bad

#Happy things#salmon#i love salmon#coho#coho salmon#Oncorhynchus kisutch#they are my babies#We should be able to feed them next week hopefully#They have lost almost all of their egg sacs#About 20/197 aren't swimming yet but they are all trying!#So excited about them#I love these guys#In a while I'll go to the creek and see if there's any fry there#I don't know if it's too far upstream for them#Ive seen fry there before but I didn't see any spawning salmon this year

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

If I asked Peppi-no if I could hug him would he say yes

Also here is a picture of a fish

Ah yes, thank you for this wonderful specimen of Oncorhynchus kisutch, much appreciated!

As for the question, Peppi-no is reluctant to hugs or physical contact in general. If someone tried to hug him or touch him he would try to scramble away.

But you know what? For the fish I'm going to draw him being hugged anyway :)

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

i /love/ salmon, can i have one?

Salmon for ye

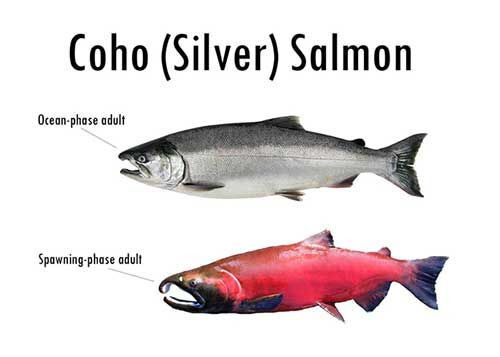

You get a Silver Salmon

Oncorhynchus kisutch

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

You get a Coho salmon

Oncorhynchus kisutch

How do you become a gimmick blog?

step 1: think of a gimmick

step 2: blog

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

Preliminary research sheds light on proper analysis and sample handling for the tire-derived contaminants 6PPD and 6PPD-quinone

Read the full project summary and access project publications. Tire and road wear particles have been shown to cause acute effects to sensitive aquatic animals and degrade their habitats. U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scientists developed methods to accurately identify aquatic compounds, such as 6PPD and 6PPD-quinone, that can cause acute mortality events in coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch).

0 notes

Text

Expired Cans of Salmon From Decades Ago Reveal a Huge Surprise

Jess Cockerill for ScienceAlert:

So when [parasite ecologist] Chelsea Wood got a call from Seattle's Seafood Products Association, asking if she'd be interested in taking boxes of dusty old expired cans of salmon – dating back to the 1970s – off their hands, her answer was, unequivocally, yes.

…

The 178 tin cans in the 'archive' contained four different salmon species caught in the Gulf of Alaska and Bristol Bay across a 42-year period (1979–2021), including 42 cans of chum (Oncorhynchus keta), 22 coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch), 62 pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), and 52 sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka).

Although the techniques used to preserve the salmon do not, thankfully, keep the worms in pristine condition, the researchers were able to dissect the filets and calculate the number of worms per gram of salmon.

They found worms had increased over time in chum and pink salmon, but not in sockeye or coho.

Extremely normal thing to measure, it doesn't get more normal than that in fact

1 note

·

View note

Text

Exploring the Fascinating World of Salmon and Sturgeon Species

Introduction

Salmon and sturgeon are among the most fascinating and important species in aquatic ecosystems. These fish are not only vital for the environment but also hold significant value in culinary and cultural aspects. This comprehensive guide explores the different types of salmon and sturgeon, their characteristics, habitats, and uses.

Types of Salmon

1. Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar)

Characteristics: Known for its silvery skin and spotted back.

Habitat: Native to the North Atlantic Ocean.

Culinary Uses: Highly prized for its tender, flavorful flesh.

2. Pacific Salmon

Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha): Largest of the Pacific salmon, valued for its high-fat content.

Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch): Known for its mild flavor and firm texture.

Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka): Distinctive for its bright red flesh and rich flavor.

Pink Salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha): The most abundant but smallest in size, often canned or smoked.

Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta): Recognized for its pale flesh and lower fat content, commonly used in frozen and canned products.

3. Freshwater Salmon

Kokanee Salmon: A landlocked form of Sockeye, found in freshwater lakes.

Masu Salmon: Native to Japan, unique for its cherry blossom-colored flesh.

Types of Sturgeon

1. Beluga Sturgeon (Huso huso)

Characteristics: One of the largest freshwater fish, known for producing the finest caviar.

Habitat: Found primarily in the Caspian and Black Seas.

2. Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus)

Characteristics: Noted for its bony plates and elongated body.

Habitat: Native to the eastern coast of North America.

3. Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens)

Characteristics: Recognized by its shark-like tail and rounded snout.

Habitat: Inhabits the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins.

Culinary and Cultural Significance

Both salmon and sturgeon hold immense culinary value. Salmon is celebrated for its versatility in dishes, from sushi to grilled preparations. Sturgeon, especially for its roe, is a delicacy in many cultures, symbolizing luxury and fine dining.

Conservation Efforts

Conservation of these species is crucial due to overfishing and habitat loss. Sustainable practices and regulations are essential for their survival.

FAQs

What is the difference between Atlantic and Pacific salmon?

Atlantic salmon are typically larger and have a more pronounced flavor, while Pacific salmon are known for their variety and rich, fatty textures.

Can sturgeon be found in freshwater and saltwater?

Yes, some sturgeon species are anadromous, migrating between freshwater and saltwater environments.

Is caviar only produced by sturgeon?

While sturgeon caviar is the most renowned, other fish like salmon also produce roe used in cuisine.

Conclusion

Understanding the types of salmon and sturgeon is crucial for appreciating their role in ecosystems and gastronomy. Conservation efforts are vital to ensure these species continue to thrive for future generations.

0 notes

Text

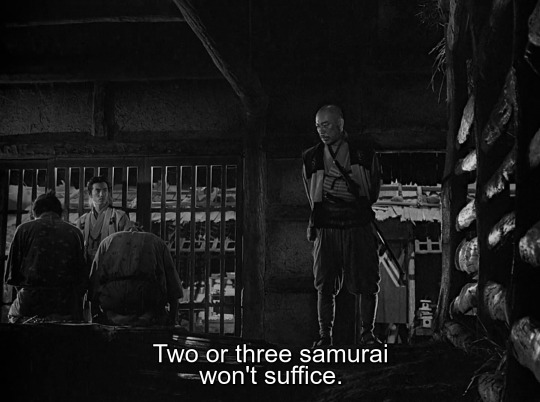

You get a Coho Salmon

Oncorhynchus kisutch

watching Seven Samurai

153K notes

·

View notes

Text

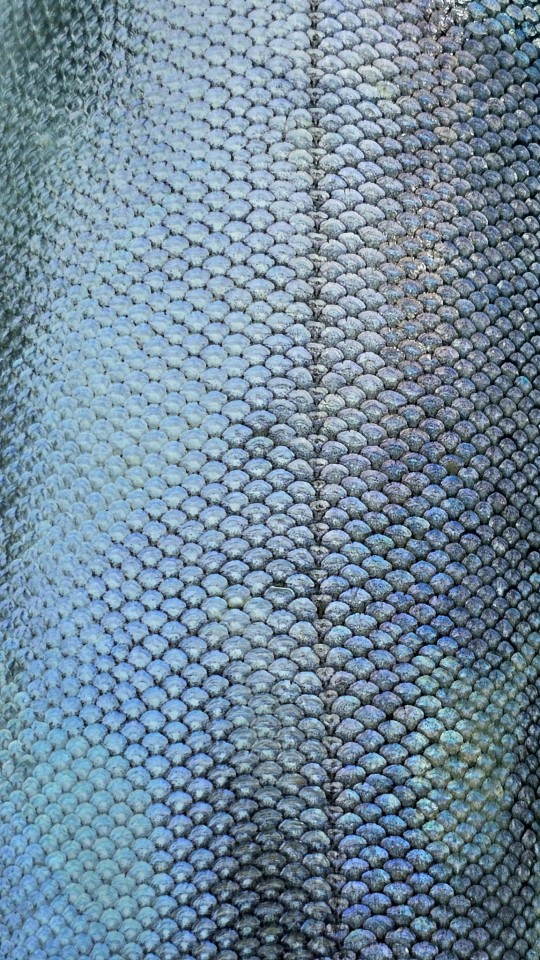

Coho Salmon / Silver Salmon - Oncorhynchus kisutch

Scale Pattern, 07/10/2023

#personal#photography#nature#nature photography#alaska#temperate rainforest#naturecore#southeast alaska#ketchikan#island living#watercore#silver salmon#coho salmon#Oncorhynchus kisutch#sea punk#fish scales#scale pattern#silver#ocean#pacific northwest#pacnw#alaskan wildlife#my photgraphy#sea life#salmon#summer#2023

213 notes

·

View notes

Link

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Coho Salmon Oncorhynchus kisutch

#coho salmon#salmon#animal#animalia#animal photography#wildlife#wildlife photography#icthyology#fish#school#actinopterygii#salmoniformes#salmonidae#oncorhynchus#oncorhynchus kisutch#salmonids

30 notes

·

View notes

Link

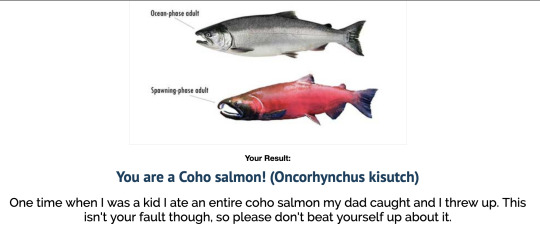

You are a Coho salmon! (Oncorhynchus kisutch) One time when I was a kid I ate an entire coho salmon my dad caught and I threw up. This isn't your fault though, so please don't beat yourself up about it.

Hi I spent the entire afternoon in a salmon-fueled fugue state and now finally the most important quiz is here. I’ve brought it to you.

#rebagel#salmon#salmon quiz#coho salmon#oncorhynchus kisutch#oh hey! i'm also scared of bears!#i really need to go to bed

12K notes

·

View notes

Note

Greetings ! May i have some sort of salmon ?

Many thanks !

You get a Coho Salmon

Oncorhynchus kisutch

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today was Trip # 4 for coho salmon ���� My kid was  excited 😜 To catch a fish #fishing #salmonFishing #SandyRiver #andreyshunt #Fallsalmon #pnwfishing #oregon #oregonfishing #portlandfishing #portland #fishinglife #sandyriverfishing #Oncorhynchus #Pink #gorbuscha #Sockeye #nerka #Coho #kisutch #Chum #keta #Chinook #tshawytscha #Steelhead #mykiss #Cutthroat #clarkiclarki #fishinglife #fishingseason #fishingguide (at Sandy River Delta Park) https://www.instagram.com/p/CU9oKibrwfx/?utm_medium=tumblr

#fishing#salmonfishing#sandyriver#andreyshunt#fallsalmon#pnwfishing#oregon#oregonfishing#portlandfishing#portland#fishinglife#sandyriverfishing#oncorhynchus#pink#gorbuscha#sockeye#nerka#coho#kisutch#chum#keta#chinook#tshawytscha#steelhead#mykiss#cutthroat#clarkiclarki#fishingseason#fishingguide

0 notes

Text

Why Forests Need Salmon

(Originally posted at my blog at https://rebeccalexa.com/why-forests-need-salmon/)

One of my favorite fall activities is to check local streams for salmon runs. Here in the Pacific Northwest, and extending north into Alaska, we have seven species of anadromous Salmonidae: chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), coastal cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii clarkii), and steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss). My favorite run is the chum salmon that run up Ellsworth Creek in southwest Washington each fall, but I’m honestly just happy to see any migrating salmon. And as I hike through stands of ancient western red cedar (Thuja plicata), I like to think about the many ways in which these and other forests need salmon for their ongoing health.

Anadromous fish are those that are born in fresh water, spend much of their adult lives in salt water, and then return to fresh water to spawn. Some, like Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and some populations of American shad (Alosa sapidissima) are iteroparous, meaning they can make this journey multiple times in a lifetime. Pacific salmonids, on the other hand, are semelparous, meaning that they spawn once and then die shortly thereafter. (From here on out I am going to use “salmon” as a general, casual term referring to both the Oncorhynchus species, and the steelhead and cutthroat trout.)

Pacific salmon were originally freshwater fish that inhabited lakes and slow-moving rivers. Somewhere around 25 million years ago, the climate cooled significantly, with average temperatures dropping almost twenty degrees F. We’re not sure at what point after this the salmon began expanding into brackish estuaries and then the Pacific Ocean itself, but when they did they found rich sources of food unlike what they had access to in fresh water. Over time, they evolved a life cycle that let them be born in the relatively safe shelter of freshwater streams, and then go out to the ocean to feast on the banquet found there when they were large enough to have a better chance of survival.

Eventually salmon runs could be found in streams as far inland as eastern Idaho, eastern British Columbia, and the southern two-thirds of Alaska (with some Alaskan runs even crossing over into Canada!) And until the arrival of European colonizers, these streams consistently provided indigenous people all along the Pacific coastline an incredibly important source of food, cultural and economic trade, mythos, and more. Unfortunately, the newcomers overharvested the salmon, dammed and destroyed streams and other habitat, and of course spearheaded the causes of anthropogenic climate change.

Indigenous people fish for salmon at Celilo Falls on the Columbia River. As the single longest continuously inhabited community in North America (over 15,000 years!), this location was a home and hub of cultural activity for many indigenous tribes and communities across the region before it was flooded by the completion of the Dalles Dam in 1957.

All these factors have led to a precipitous decline in the size of both salmon runs, and the salmon themselves. This isn’t just detrimental to indigenous communities, though. It also threatens the health of forests all throughout the salmons’ range.

A forest isn’t just made of trees. It’s composed of entire plant communities, fungi (including mycorrhizal species), and the animals, bacteria, and other living beings that share space with them. When salmon travel up and down the waterways as fry, and then later to spawn as adults, they have a direct impact on that ecosystem.

Salmon fry are an important source of food for larger fish, amphibians, birds, and other beings that seek food in the water. In fact, part of why salmon lay so many eggs (over 5,000 in the case of chinook!) is because most of the fry that hatch will never make it to adulthood. But adult salmon aren’t safe from predation on their return trip to their birthplaces. In fact, they are caught and eaten by a wide variety of animals from bears to eagles, wolves to osprey, sea lions to bobcats.

Bears are of particular interest here. Brown bears (Ursus arctos) are well-known for gorging on summer and fall salmon runs to build up massive amounts of fat in preparation for winter hibernation. (Katmai National Park even celebrates their bears during Fat Bear Week every October!) You can watch video feeds of several bears hanging out in their favorite fishing spots by waterfalls and in the flow of the river.

Imagine that you are a young bear, perhaps recently forced to independence by your mother who is now focused on your younger siblings. You have to not only start catching fish without her protection from bigger bears, but you also need to make sure those stronger bears don’t steal your catch. What’s the best thing to do? Run far away into the woods to eat your salmon in peace, then leave the remains among the trees and head back for more.

If the fishing is good, bears will often eat only the fattiest parts of the salmon like the brains and skin, and then leave the rest behind for scavengers. The nutrients in the salmon then disseminate throughout the forest, whether carried in the digestive systems of animals, or broken down in place by decomposers. This helps make the nutrients available to the plants, particularly trees which may store massive amounts of nutrients in their trunks; when the trees die, they essentially become a food pantry for younger beings like new seedlings, fungi, and so forth.

Now–what’s so special about the nutrients in salmon? Well, remember that these fish spend years out in the ocean. And the ocean has an entirely different balance of nutrients floating around in it compared to what’s found in fresh water or on land. The salmon are essentially the only way these ocean-borne nutrients can make their way into the forest in any meaningful amount, and they do so on a regular basis each year. The trees near salmon runs fished by bears may be 300% larger than usual, and salmon also provide nearly three quarters of the nitrogen in the forest. That’s a pretty impressive contribution!

This isn’t just about how forests need salmon; it’s a reciprocal relationship. While the salmon’s immediate habitats are aquatic, these streams, rivers, and other waterways are directly affected by what happens on the land around them.

Every waterway has a watershed–an area of land from which precipitation drains into that waterway. These watersheds nest within each other; the watersheds of small streams are nested within the watersheds of the rivers the streams feed into. That water carries things with it, from soil to pollutants. So the health of the land has a direct impact on what is found in the water.

But it goes beyond what’s washed downstream, and into how it’s washed down. In a healthy forest, for example, the soil is able to absorb a significant amount of precipitation that falls throughout the year, keeping it from simply cascading down hillsides to create flooding and landslides. Water is also stored in the various living beings in the forest; again trees are often the champions with their great size, but smaller plants help with water retention quite a bit as well, both through internal storage and preventing evaporation from soil. A forest that is badly damaged, such as through a clearcut or wildfire, won’t hold water as well. This can lead to floods, landslides and other erosion, and increase the impact of summer droughts as the land simply can’t store as much water, or for as long.

All of this affects the salmon directly. If the watershed is no longer holding and releasing snowmelt, rain, and other water in a controlled manner, this can lead to flooding in waterways which can wash away salmon eggs and fry. Increased erosion buries the gravel that salmon lay eggs in with silt, smothering the eggs so they never hatch. When a riparian zone–the land along a waterway–is stripped of vegetation, the water loses crucial shaded areas that keep temperatures cool. Salmon easily overheat when temperatures rise even a few degrees. And drought can dry up smaller streams, stranding and even killing young salmon while preventing adults from reaching their spawning grounds.

While not every single salmon run exclusively travels through forests, many of them do. And many spawning grounds are found in forests, or at least areas with significant tree cover in riparian zones. Salmon must have healthy forests in order to continue to survive, and the loss of these forests is just one of many factors contributing to their severe decline.

Thankfully, I am far from the only person concerned about the safety of our wild Pacific salmon. There are numerous organizations working to protect and restore salmon habitat through dam removal, preservation and restoration of aquatic habitat and surrounding land, regulations on salmon fishing, and educating people about sustainable seafood options (or just not eating seafood at all.) And even habitat restoration efforts that aren’t directly in salmon-inhabited waterways still have a positive impact on the forest ecosystem as a whole.

We know that forests need salmon, and salmon need forests. To protect one is to protect the other, and long may they both thrive.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#long post#salmon#fish#forests#nature#ecology#science#science communication#scicomm#wildlife#bears#Pacific Northwest#PNW#ecosystems#biology#extinction#endangered species#conservation#environment#environmentalism

608 notes

·

View notes