#Olympian Glades of Arborea

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Airmark's Guide to Planar Vegetables: Heartshare Rose

This thick, vibrant green shrub grows best in a mild climate in partial shade, making the heavily forested first layer of Arborea its ideal growing conditions. While the stems and stalks of the plant are covered in thick, curved thorns, the plant lacks much that would draw in predators save its beautiful, deep red flowers. These flowers, both the main attraction of the shrub and the rarest element of its biology, do not bloom under any circumstances but under the care of a gardener. This is because, due to some unknown mechanism, the heartshare rose only blooms if it is being tended by one who is in love. This makes the shrub’s reproduction solely dependent on acts of care by the ardent, the other reason it flourishes most successfully in Arborea. The ambient emotional climate of unrestrained but well-intentioned feeling is necessary to the heartshare rose’s growth, and the plant rarely flourishes in large quantity elsewhere, although potted plants are often the centerpiece - and passion project - of the dedicated interplanar gardener.

#Airmark's Guide to Planar Vegetables#D&D#Dungeons and Dragons#Dungeons & Dragons#Planescape#Olympian Glades of Arborea#Arborea

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not ruling out Fearne popping up in Exandria just yet, but if she IS on another plane...based on the Forgotten Realms wiki description, Arborea sounds like a really good candidate:

The Olympian Glades of Arborea, sometimes simplified to just Olympus or Arborea, was the Outer Plane in the Great Wheel cosmology model embodying the chaotic good alignment. A plane of joy as well as sorrow, Arborea was the home of the dreamers, a seemingly delicate sylvan realm of astounding heartiness and deep-seated enchantment. Its beauty was almost overwhelming, the landscape embodying the lovely and peaceful, and the passionate and wild, all at the same time.

#the dreamers and sylvan mentions are what got me going 👀#doubt it's the same name but it could be the inspiration#critical role

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lot of this is true and useful and great. Most notably, the discussion of the copyrightability of mechanics, the things copyright might extend to, the ways you give up rights with the OGL that may be bad, and ways you can avoid the OGL and still publish D&D content. It makes some really good points.

But a lot of it is also wrong. It is ignorant of what Hasbro is actually trying to do with the OGL to destroy it, it is ignorant of the actual terms of the OGL itself, and it is ignorant of the RPG space and why the OGL is important to the people in it.

What the OGL actually licenses

The OGL makes a distinction between Product Identity, which is not licensed, and Open Game Content, which is. Cory claims that OGC is only mechanical, ie, not copyrightable, and that everything else is product identity. That's not really true, but it may not matter.

Let us first look at Open Game Content as defined by the OGL:

"Open Game Content" means the game mechanic and includes the methods, procedures, processes and routines to the extent such content does not embody the Product Identity and is an enhancement over the prior art and any additional content clearly identified as Open Game Content by the Contributor, and means any work covered by this License, including translations and derivative works under copyright law, but specifically excludes Product Identity.

This explicitly cites game mechanics, but clearly states that it also includes "any additional content clearly identified as Open Game Content by the Contributor" (emphasis mine). The SRD5 therefore states:

All of the rest of the SRD5 is Open Game Content as described in Section 1(d) of the License.

"the rest", in context, referring to everything that isn't product identity. And product identity is defined as follows:

"Product Identity" means product and product line names, logos and identifying marks including trade dress; artifacts; creatures characters; stories, storylines, plots, thematic elements, dialogue, incidents, language, artwork, symbols, designs, depictions, likenesses, formats, poses, concepts, themes and graphic, photographic and other visual or audio representations; names and descriptions of characters, spells, enchantments, personalities, teams, personas, likenesses and special abilities; places, locations, environments, creatures, equipment, magical or supernatural abilities or effects, logos, symbols, or graphic designs; and any other trademark or registered trademark clearly identified as Product identity by the owner of the Product Identity, and which specifically excludes the Open Game Content;

Cory claims that the OGL excludes anything copyrightable, but that's just not what this does. The term "clearly identified" is the key here: you have to provide a list of things deemed Product Identity, and if it's not on that list, it's not Product Identity. The SRD5 does exactly this:

The following items are designated Product Identity, as defined in Section 1(e) of the Open Game License Version 1.0a, and are subject to the conditions set forth in Section 7 of the OGL, and are not Open Content: Dungeons & Dragons, D&D, Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master, Monster Manual, d20 System, Wizards of the Coast, d20 (when used as a trademark), Forgotten Realms, Faerûn, proper names (including those used in the names of spells or items), places, Underdark, Red Wizard of Thay, the City of Union, Heroic Domains of Ysgard, Ever-‐‑ Changing Chaos of Limbo, Windswept Depths of Pandemonium, Infinite Layers of the Abyss, Tarterian Depths of Carceri, Gray Waste of Hades, Bleak Eternity of Gehenna, Nine Hells of Baator, Infernal Battlefield of Acheron, Clockwork Nirvana of Mechanus, Peaceable Kingdoms of Arcadia, Seven Mounting Heavens of Celestia, Twin Paradises of Bytopia, Blessed Fields of Elysium, Wilderness of the Beastlands, Olympian Glades of Arborea, Concordant Domain of the Outlands, Sigil, Lady of Pain, Book of Exalted Deeds, Book of Vile Darkness, beholder, gauth, carrion crawler, tanar’ri, baatezu, displacer beast, githyanki, githzerai, mind flayer, illithid, umber hulk, yuan-‐‑ti.

...Now, how much is left that can be copyrighted (beyond the rules text itself) is another issue, but that seems like a pretty cut and dry distinction.

Rob Bodine, who is a real lawyer, claims in the article Cory links that the OGL doesn't actually license anything, but that claim seems to be partly based in the idea that 1) the SRD is not actually licensed under the OGL, but rather a set of the content that wizards considers usable under it and 2) that product identity is maximal under the OGL, encompassing everything possible under that definition, not simply what is enumerated. In fact, the SRD is the only thing licensed under the OGL, and, as stated above, it seems that what is product identity must be stated. He makes some other arguments that might be more valid about issues that might make the OGL invalid or legally fraught (like the OGL claiming to license game mechanics... which it can't, the use constitutes agreement issue—which, despite some claims, doesn't apply to anything other then the SRD: the PHB/DMG/etc aren't actually OGLed—and some unsettled legal issues around shrinkwrap licensing, as well as concerns about the distributability of the SRD itself), which might be valid, but it's hard to say without going to court.

Killing the OGL: It's got nothing to do with the word "irrevocable"

Cory makes a big deal out of the lack of the word "irrevocable" in the OGL. This is not good, but it doesn't matter right now. Bluntly, the lack of the word "irrevocable" isn't a trap, it's just that nobody in the year 2000 thought that it was necessary. And I mean nobody: Creative Commons was born a few years later and didn't include the word "irrevocable". The GPLv2, near as I can tell, also does not use the term. Neither does the MPL or the CDDL (the MPLv2 still doesn't...), Apache didn't have it until Apache-2.0 in 2004, MIT and BSD don't have it, and neither does the Artistic License.

Walsh's article, which Cory links, notes in an update that if Wizards attempted this, anyone currently using the OGL has a strong argument that they can still use the content under its terms, but new people wouldn't be able to (the terms of the OGL 1.0a grant the right to distribute the SRD, so it could be argued you could use this to get around this somehow, but the OGL doesn't explicitly grant you the right to sublicense, nor does it have a GPL-esque automatic license grant clause, so that seems shakey. Kit Walsh is a lawyer and I'm not, and she works in this area of the law specifically, so I'll take her word for it when she says this won't fly—for my money, this is actually the biggest problem with the OGL, and the word "irrevocable" may fix it, but it would be better to also have a proper GPL-esque automatic license grant clause. It's possible that Hasbro's lawyers don't agree with Kit, because it certainly seems like they'd love to revoke the OGL but feel they can't... but there could be social reasons there, ie they think revoking the OGL would make them look even more like assholes).

It also doesn't matter in this case because Wizards isn't trying to revoke the OGL. They are trying to force people to use the OGL 1.1 by making the OGL 1.0 unauthorized. Kit goes on go say that this has serious legal issues, but I'm not getting into that, I already talked about that.

Why would anyone use the OGL?

As Cory and Kit point out, you give up rights to use copyrighted content you otherwise could under fair use by using the OGL. So why would you ever use it?

Kit says this:

the only benefit that OGL offers, legally, is that you can copy verbatim some descriptions of some elements that otherwise might arguably rise to the level of copyrightability.

The thing is, as well-known tumblr user prokopetz (who actually designs RPGs, so I'm trusting him) has stated, having this ability is tremendously useful in the context of a system as complicated as D&D. The fact of the matter is that fair use and avoiding copyrighted material when publishing a D&D compatible supplement is actually really hard. There are terms you can and can't use, and distinctions are murky and only decided through litigation. As Kit also points out:

The primary benefit is that you know under what terms Wizards of the Coast will choose not to sue you, so you can avoid having to prove your fair use rights or engage in an expensive legal battle over copyrightability in court.

And that is the real benefit of an explicit license to content when some but not all of it is covered under fair use or isn't copyrightable. It gives you a legal grounds to do what you want without worrying about having to get a copyright lawyer to check every single sentence you right and then pray you don't get sued.

Because 1) there are things in RPGs, specific verbiage and descriptions, names for different parts of the rules, and so forth that can be copyrighted, and 2) you can be sued out of existence if you don't have some kind of insurance, something Wizards knows all too well because they almost did get sued out of existence for this very reason. And a good, properly written open license is fairly ironclad in protecting you, ideally even in cases where the entity holding the license is actively hostile.

So, assuming that there is copyrightable content in the SRD (which I am fairly certain there is), and that that copyrightable content is covered as OGC under the OGL (which I and many others do believe, but there has been some contention), the OGL does make sense, and it does grant rights you may not have by fair use or public domain. Since fair use is found in court, you might not want to take the chance.

So I don't think the OGL is crazy, and I don't think it's malicious. I do think that it's flawed, and that it has a number of real problems. I think part of the reason might be Wizards' legal department trying to lay claim to as much as they can, and also just the state of the world when the OGL was drafted. Remember: The OGL predates Creative Commons. It was one of the earliest attempts I know of to write a license based on the ideas of open source for something other than software. That doesn't make it exempt from accusations of malice... I just don't think they hold up to inspection.

And if you want to put out an SRD that people can freely use to create a derived work nowadays? Just put it under Creative Commons...

Good riddance to the Open Gaming License

Last week, Gizmodo’s Linda Codega caught a fantastic scoop — a leaked report of Hasbro’s plan to revoke the decades-old Open Gaming License, which subsidiary Wizards Of the Coast promulgated as an allegedly open sandbox for people seeking to extend, remix or improve Dungeons and Dragons:

https://gizmodo.com/dnd-wizards-of-the-coast-ogl-1-1-open-gaming-license-1849950634

The report set off a shitstorm among D&D fans and the broader TTRPG community — not just because it was evidence of yet more enshittification of D&D by a faceless corporate monopolist, but because Hasbro was seemingly poised to take back the commons that RPG players and designers had built over decades, having taken WOTC and the OGL at their word.

Gamers were right to be worried. Giant companies love to rugpull their fans, tempting them into a commons with lofty promises of a system that we will all have a stake in, using the fans for unpaid creative labor, then enclosing the fans’ work and selling it back to them. It’s a tale as old as CDDB and Disgracenote:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CDDB#History

(Disclosure: I am a long-serving volunteer board-member for MetaBrainz, which maintains MusicBrainz, a free, open, community-managed and transparent alternative to Gracenote, explicitly designed to resist the kind of commons-stealing enclosure that led to the CDDB debacle.)

https://musicbrainz.org/

Free/open licenses were invented specifically to prevent this kind of fuckery. First there was the GPL and its successor software licenses, then Creative Commons and its own successors. One important factor in these licenses: they contain the word “irrevocable.” That means that if you build on licensed content, you don’t have to worry about having the license yanked out from under you later. It’s rugproof.

Now, the OGL does not contain the word “irrevocable.” Rather, the OGL is “perpetual.” To a layperson, these two terms may seem interchangeable, but this is one of those fine lawerly distinctions that trip up normies all the time. In lawyerspeak, a “perpetual” license is one whose revocation doesn’t come automatically after a certain time (unlike, say, a one-year car-lease, which automatically terminates at the end of the year). Unless a license is “irrevocable,” the licensor can terminate it whenever they want to.

This is exactly the kind of thing that trips up people who roll their own licenses, and people who trust those licenses. The OGL predates the Creative Commons licenses, but it neatly illustrates the problem with letting corporate lawyers — rather than public-interest nonprofits — unleash “open” licenses on an unsuspecting, legally unsophisticated audience.

The perpetual/irrevocable switcheroo is the least of the problems with the OGL. As Rob Bodine— an actual lawyer, as well as a dice lawyer — wrote back in 2019, the OGL is a grossly defective instrument that is significantly worse than useless.

https://gsllcblog.com/2019/08/26/part3ogl/

The issue lies with what the OGL actually licenses. Decades of copyright maximalism has convinced millions of people that anything you can imagine is “intellectual property,” and that this is indistinguishable from real property, which means that no one can use it without your permission.

The copyrightpilling of the world sets people up for all kinds of scams, because copyright just doesn’t work like that. This wholly erroneous view of copyright grooms normies to be suckers for every sharp grifter who comes along promising that everything imaginable is property-in-waiting (remember SpiceDAO?):

https://onezero.medium.com/crypto-copyright-bdf24f48bf99

Copyright is a lot more complex than “anything you can imagine is your property and that means no one else can use it.” For starters, copyright draws a fundamental distinction between ideas and expression. Copyright does not apply to ideas — the idea, say, of elves and dwarves and such running around a dungeon, killing monsters. That is emphatically not copyrightable.

Copyright also doesn’t cover abstract systems or methods — like, say, a game whose dice-tables follow well-established mathematical formulae to create a “balanced” system for combat and adventuring. Anyone can make one of these, including by copying, improving or modifying an existing one that someone else made. That’s what “uncopyrightable” means.

Finally, there are the exceptions and limitations to copyright — things that you are allowed to do with copyrighted work, without first seeking permission from the creator or copyright’s proprietor. The best-known exception is US law is fair use, a complex doctrine that is often incorrectly characterized as turning on “four factors” that determine whether a use is fair or not.

In reality, the four factors are a starting point that courts are allowed and encouraged to consider when determining the fairness of a use, but some of the most consequential fair use cases in Supreme Court history flunk one, several, or even all of the four factors (for example, the Betamax decision that legalized VCRs in 1984, which fails all four).

Beyond fair use, there are other exceptions and limitations, like the di minimis exemption that allows for incidental uses of tiny fragments of copyrighted work without permission, even if those uses are not fair use. Copyright, in other words, is “fact-intensive,” and there are many ways you can legally use a copyrighted work without a license.

Which brings me back to the OGL, and what, specifically, it licenses. The OGL is a license that only grants you permission to use the things that WOTC can’t copyright — “the game mechanic [including] the methods, procedures, processes and routines.” In other words, the OGL gives you permission to use things you don’t need permission to use.

But maybe the OGL grants you permission to use more things, beyond those things you’re allowed to use anyway? Nope. The OGL specifically exempts:

Product and product line names, logos and identifying marks including trade dress; artifacts; creatures characters; stories, storylines, plots, thematic elements, dialogue, incidents, language, artwork, symbols, designs, depictions, likenesses, formats, poses, concepts, themes and graphic, photographic and other visual or audio representations; names and descriptions of characters, spells, enchantments, personalities, teams, personas, likenesses and special abilities; places, locations, environments, creatures, equipment, magical or supernatural abilities or effects, logos, symbols, or graphic designs; and any other trademark or registered trademark…

Now, there are places where the uncopyrightable parts of D&D mingle with the copyrightable parts, and there’s a legal term for this: merger. Merger came up for gamers in 2018, when the provocateur Robert Hovden got the US Copyright Office to certify copyright in a Magic: The Gathering deck:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/08/14/angels-and-demons/#owning-culture

If you want to learn more about merger, you need to study up on Kregos and Eckes, which are beautifully explained in the “Open Intellectual Property Casebook,” a free resource created by Jennifer Jenkins and James Boyle:

https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/openip/#q01

Jenkins and Boyle explicitly created their open casebook as an answer to another act of enclosure: a greedy textbook publisher cornered the market on IP textbook and charged every law student — and everyone curious about the law — $200 to learn about merger and other doctrines.

As EFF Senior Staff Attorney Kit Walsh writes in her must-read analysis of the OGL, this means “the only benefit that OGL offers, legally, is that you can copy verbatim some descriptions of some elements that otherwise might arguably rise to the level of copyrightability.”

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/01/beware-gifts-dragons-how-dds-open-gaming-license-may-have-become-trap-creators

But like I said, it’s not just that the OGL fails to give you rights — it actually takes away rights you already have to D&D. That’s because — as Walsh points out — fair use and the other copyright limitations and exceptions give you rights to use D&D content, but the OGL is a contract whereby you surrender those rights, promising only to use D&D stuff according to WOTC’s explicit wishes.

“For example, absent this agreement, you have a legal right to create a work using noncopyrightable elements of D&D or making fair use of copyrightable elements and to say that that work is compatible with Dungeons and Dragons. In many contexts you also have the right to use the logo to name the game (something called “nominative fair use” in trademark law). You can certainly use some of the language, concepts, themes, descriptions, and so forth. Accepting this license almost certainly means signing away rights to use these elements. Like Sauron’s rings of power, the gift of the OGL came with strings attached.”

And here’s where it starts to get interesting. Since the OGL launched in 2000, a huge proportion of game designers have agreed to its terms, tricked into signing away their rights. If Hasbro does go through with canceling the OGL, it will release those game designers from the shitty, deceptive OGL.

According to the leaks, the new OGL is even worse than the original versions — but you don’t have to take those terms! Notwithstanding the fact that the OGL says that “using…Open Game Content” means that you accede to the license terms, that is just not how contracts work.

Walsh: “Contracts require an offer, acceptance, and some kind of value in exchange, called ‘consideration.’ If you sell a game, you are inviting the reader to play it, full stop. Any additional obligations require more than a rote assertion.”

“For someone who wants to make a game that is similar mechanically to Dungeons and Dragons, and even announce that the game is compatible with Dungeons and Dragons, it has always been more advantageous as a matter of law to ignore the OGL.”

Walsh finishes her analysis by pointing to some good licenses, like the GPL and Creative Commons, “written to serve the interests of creative communities, rather than a corporation.” Many open communities — like the programmers who created GNU/Linux, or the music fans who created Musicbrainz, were formed after outrageous acts of enclosure by greedy corporations.

If you’re a game designer who was pissed off because the OGL was getting ganked — and if you’re even more pissed off now that you’ve discovered that the OGL was a piece of shit all along — there’s a lesson there. The OGL tricked a generation of designers into thinking they were building on a commons. They weren’t — but they could.

This is a great moment to start — or contribute to — real open gaming content, licensed under standard, universal licenses like Creative Commons. Rolling your own license has always been a bad idea, comparable to rolling your own encryption in the annals of ways-to-fuck-up-your-own-life-and-the-lives-of-many-others. There is an opportunity here — Hasbro unintentionally proved that gamers want to collaborate on shared gaming systems.

That’s the true lesson here: if you want a commons, you’re not alone. You’ve got company, like Kit Walsh herself, who happens to be a brilliant game-designer who won a Nebula Award for her game “Thirsty Sword Lesbians”:

https://evilhat.com/product/thirsty-sword-lesbians/

[Image ID: A remixed version of David Trampier’s ‘Eye of Moloch,’ the cover of the first edition of the AD&D Player’s Handbook. It has been altered so the title reads ‘Advanced Copyright Fuckery. Unclear on the Concept. That’s Just Not How Licenses Work. No, Seriously.’ The eyes of the idol have been replaced by D20s displaying a critical fail '1.’ Its chest bears another D20 whose showing face is a copyright symbol.]

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dismon Fuelon’s Backstory

Before I begin writing this character’s reports and story, I suppose you should know where he came from, and what led him to this. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Dismon’s life began like so many others. His parents; a cambion named Oriel Fuelon and a Tiefling named Victoria Fuelon, lived on a farm in the Abyss. The plane was nice and had plenty of abyssal denizens, and the two were happy with their son. Dismon grew up with the normal duties of a farm hand. Cleaning, training, and helping around the house were his daily duties, and he was content with his loving family. When he turned 7, his parents gave birth to a baby boy, who he cherished and acted as an ideal older brother to.

On the Abyssal Plane they lived on, a Balor, the Lord of Shadows, ruled in a rather backseated way, every generation or so, he would show up on people's doorstep. He warned of a disaster coming, one that only he could protect them from. He would request only one thing, the families first born child, or an able bodied demon to join his thrall. When Dismon’s parents were offered this protection, they instead bartered to be sent to the material plane. Dismon was only 10 at this point. His whole life, he had grown up being loved and cared for by his parents, he loved his little brother and had no control or power in any of this. He remembers the day clearly, the knock at the door, the hushed conversation, and the quick decision. His mother came to him and hugged him, telling him it would be okay, that she loved him, that he had to stay strong. She said one day he’d forgive her. He never understood any of this at the time, and was handed off to the Balor. He looked back to them, begging and crying for them to take him back as his parents turned away and, in a literal snap of the Balor’s fingers, popped from his sight. The training that came next , was simply torture. It was designed to break a new thrall’s spirit, wiper their mind of any thoughts of ever leaving or disobeying. It trained him to never disobey a higher demon or fiend, and if you did, he watched the consequences. The displays of disobedient thralls being tortured until they begged for death leaves an emotional mark on you. Dismon knew this mark well and stayed quiet and obedient. After years of this torture, the blank slates were sent to begin a new type of training. In this training, they learned physical prowess, dexterity, and knowledge (in limited amounts). They were kept dumb, but strong, fast, and flexible. Some thralls went to become servants, some went to serve in the Lord’s army, and a select few were chosen for specialized roles. 10 were chosen among Dismon’s group, all who ranged between 20-25. Their training began to get more specialized. This training involved everything from interrogating, to interrogations. His most apparent sign of that training is a large scar going down the center of his chest which never seemed to properly heal. Among that and many other small scars, he learned to be silent and conscious of his mind in every place. For those who weren’t magically inclined, the Lord gave them a pact, to give them just a sliver of his power. Dismon received a Scroll of Shadows and his training continued into the arcane. In the coming 20 years, Dismon sharpened his skills, and as other thralls fell, he and two other stood at the end. The final test was their first mission. They were to go to another plane in the Abyss, and secretly observe another Balor. One was killed when they were spotted by some of the guards, but Dismon and the other thrall escaped, both having come other with as much information as possible. Both of them were approved to become two new spies for the Lord. Dismon would have his years long training broken up with day long missions to different planes. His second mission brought him to the Olympian Glades of Arborea, where he had to observe and report on the activities of a Eladrin. This mission went without a hitch, and Dismon went back to training. The third plane he was sent to was they Feywilds. He was sent to spy on a hag who had a very specific recipe for a new potion. He needed to record the exact ingredients and amount that went into the potion. This also included the order, and steps to making this potion. He was almost caught, but his wits slimly got him out of the tight situation. Over the years, he was sent to a combination of these planes, mostly on trivial missions that were important in some way to the Lord. The fourth plane he got to visit was that of Soth, the Goddess of the moon and love. This plane ended up being what sparked something inside of Dismon. When he arrived on this plane, he glanced around to find something new, a Statue. For a moment he took it in, a small thought of “why?” came to him. He quickly moved along. The beautiful garden he had landed in was the central key to his mission. The was supposedly a Great Bard here. Dismon was only to follow and take notes on what exactly he was doing there. After wandering in the shadows, Dismon found his target and hide behind a shrub. In front of him stood his target, and a woman. Their backs were turned to him and he began to record what he saw. Their conversation went something like this; “My child,” the woman began, looking to her beloved follower, “You mean you have lost inspiration?” The man furrowed his brow, sighing, “Yes… I used to create without end, but now, it seems I can barely paint a flower. The light that art gave me has faded oh so slowly… what do I do…?”

Dismon’s pen paused as he listened. What did he mean? Inspiration, creating, painting? He listened a bit closer, glancing slowly at his target and the beautiful woman. She seemed to smile and knelt down to the man, pinching his cheek, “You have not lost that inspiration, take a step back, absorb what is around you and relax. Life should be an experience. Enjoy the small moments, a butterfly on a leaf, the breeze catching a fair woman’s hair, the kiss of a lover. Really feel what emotions the world throws at you…” The man sighed softly and smiled warmly, “I suppose I can try again… I may go and walk the garden, clear my thoughts.” Dismon watched and looked to the woman, his head filling with doubts and thoughts for the first time in a long time. His eyes rested on everything around him. The architecture, the flowers in the garden, the way the man walked and the sound of his hum. It all seamlessly meleded together, almost telling it’s own story. He had been trained to focus solely on what needed to be done, but now he was looking. He was analyzing he was… feeling something, though he didn’t understand what. He snapped back, quickly following the target as he made his way through the garden. The moonlight illuminating the bard’s path as he stopped to stare at something. Dismon took a moment to look as well. It was what looked like a field with a little farmhouse. The look of the image filled Dismon with confusion, he just kept staring. Why was this recorded? Why some little house on a hill? Is this what the Goddess was talking about, is this supposed to make him feel? As he questioned this, he saw the Bard wipe a tear from his eye and move on. The bard was crying. Why was he crying? Why?? As Dismon went about his recording, questions filled his mind with each piece of art and statue they passed. And soon, his mission was over. He was returned home where he gave an exhaustive report of the Bard and who he had met over the day. His mind had changed slightly, during the weeks he only began to question more and more, and his thirst for answers grew ravenously. He started to look forward to missions to new places, and even old. Now he kept a separate set of notes on each plane, the unique structure, and the creatures and people who inhabited them. He wondered now about why they did certain things, rituals, or habits. His targets were now both his master’s task and his. He loved watching them and their rituals, doing weird or obscure things for reasons unknown to himself. The next two planes he visited was the Celestial plane, and once, the material plane. He took more of an interest in the material plane. It may have been the memories of his parents, or the varieties of creatures here and the strange customs they have. But he did like the combination of everything he had been seeing, and the questions and knowledge it brought. He now sits in front of a crystal ball, watching a party of a Goblin named Tihx, an Elf named Nissa, a Dragonborn named Soqourel, an Earth Gensai named Metal, a plant being named Douglas, and the prospective new general of his master’s army, Yrgna, a gnoll barbarian. He was tasked with watching them in everything they did. He chuckled a little as he watched the group get surrounded by Hobgoblins. His new order came in, he would join the group, supporting Yrgna and giving her a small guiding hand on her path. He would be doing this indefinitely. It was strange, his missions had only ever been a day at most, and now, how long would he stay on the Material Plane? What would he learn? How would he function in such a strange plane…? He didn’t know, as the hours came ticking down. Was he ready? Of course, not that he had a choice anyways.

0 notes

Text

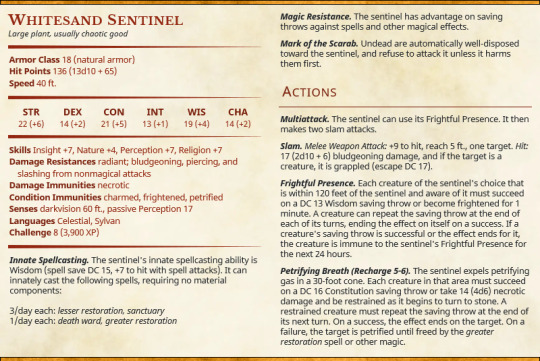

Airmark's Guide to Planar Vegetables: Whitesand Sentinel

Roaming the white sand deserts of Mithardir in Arborea, whitesand sentinels are so named because they claim to be keeping watch for (or against) some unknown phenomenon. This conviction has bought them some measure of acclaim among the layer's inhabitants, most famously among the undead who inhabit Mithardir's tombs and abandoned cities.

Whitesand sentinels are ambulatory cacti growing usually approximately twice the height of the average humanoid; they weigh more than four men put together. Their skin is usually a dark brown or greyish tone with lighter green appearing after they have received a good soaking. They do not adhere rigidly to a humanoid body plan, and often have more than two legs or arms, although two always seem to be primary and the rest secondary.

Like much of the celestial life found in Mithardir (such as the unrelated guiding beetle), the sentinels are willing to help those who find themselves lost in the vast desert, affording them drinks from their own bodies if no other water can be found and curing sunstroke and illness with a touch of their spiny hands. In extreme cases, they have been known to petrify the dying with their breath, assured that they can return them to their previous state when circumstances are more friendly to life.

They extend this courtesy to the undead, and are most often found traveling other planes when they are seeking to conclude the business of a wayward spirit. When interviewed about the subject, they claim it is related to the eternal watch they keep over the desert, although the individual I interviewed was vague on the subject. Whether this is an attempt to protect the knowledge or out of lack thereof, I cannot say.

#Airmark's Guide to Planar Vegetables#D&D#Dungeons and Dragons#Dungeons & Dragons#Planescape#Olympian Glades of Arborea#Arborea#CR 8#CR 5-10

6 notes

·

View notes