#OR c. they do see your strength and see your unwavering devotion and take advantage of that while never lending you a hand-

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

just btw

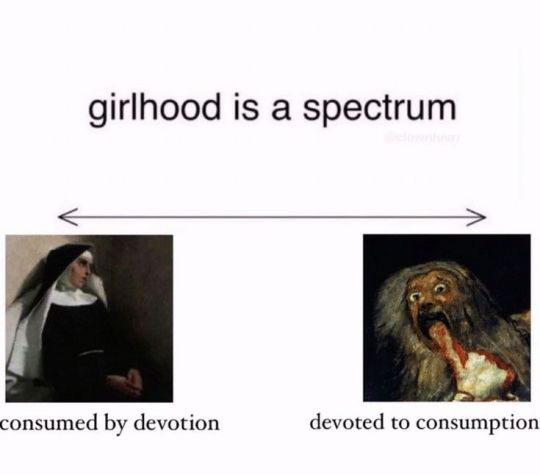

#rambles.#consumed by devotion but also just Devoted To Devotion ykwim#like so consumed by devotion that your every waking moment is spent making sure you don't stray from that path of devotion#and he's still devoted in a way but just to something else. to the opposite#being so devoted to not being devoted the paradox the contradiction the the th#sits in the corner rocking back and forth#tfw the people you're devoted to protect take advantage of that devotion and it's part of the reason you end up going mad#tfw they either a. don't believe you're 'good' enough so they continuously 'test' you or#b. they fear so much for you that they make it their job to make Yours as difficult as possible in hopes you stray from your path#OR c. they do see your strength and see your unwavering devotion and take advantage of that while never lending you a hand-#-in your own time of need bc they know it wont stop you from still helping them#leuthere being run ragged and the last straw being his mother being killed + that entity taking advantage of him#(with promises of never being taken advantage of again ... brother thats what ur doing right neow)#drags my nails down my face#this isn't even comprehensible but i'm vibrating rn#i'm also thinking about SAINT and their own big theme of being taken advantage of and how devotion can be sinister and hurtful and#lays face first down on the floor

1 note

·

View note

Note

Napoleon/Lafayette - can you explain how they viewed and interacted with each other during the Napoleonic era? And what Lafayette did after being freed from jail?

On July 24th, 1797, an Austrian officer arrived at Olmultz prison from Vienna where the Lafayette family was held. The man entered the dismal cell with a court decree: “Because Monsieur de Lafayette is regarded as author of a new doctrine whole principles are incompatible with the tranquility of the Austrian monarch, His Majesty the emperor and the king owes it to reasons of state not to restore his freedom until he pledges not to return to Austrian territory without special permission of the emperor.”

Lafayette laughed: “The emperor does me honor by treating me as one power to another and by believing that as a simple individual I am so strong a threat to a vast monarchy with so many armies and devoted subjects.” Lafayette rejected the new emperors terms, saying he had been arrested and imprisoned illegally. “I have no wish ever again to set foot the in the court of the emperor or in his country even with his permission, but I owe it to my principles to refuse to recognize that the Austrian government has any rights over me.” More ever, he demanded the Austrians release his friend La Tour-Maubourg and Bureax de Pusy and their aides.

Lafayette’s intransigence was ill-times and almost cost him, his family and his friends years of additional imprisonment. A royalist counterrevolutionary broke out in France and Napoleon pulled a division of troops from the Austrian front and returned to France to crush internal dissent. His emissary broke off negotiations for Lafayette’s release to await further instructions. Before returning to Austria, Napoleon helped stage a coup d’etat that replaced the Directory with a three-man junta that added political powers to Napoleon’s military powers.

When negotiations resumed for Lafayette’s release, the new French regime made it clear he was no more welcome in France than in Austria. His fervor for constitutional, republican rule threatened the New Directory as much as it had the Austrian emperor. Napoleon himself saw Lafayette as a threat to his own growing popularity. The French and Austrian soon agreed that the solution lay in exiling Lafayette from Europe in America. On September 19th, 1797 after five years and a month as prisoner, Lafayette and his family were released; they wrote Napoleon a message of thanks:

“Citozen general,

The prisoners of Olmutz, fortunate in owing their deliverance to the benevolence of their nation and to your irrestible military strength, rejoiced, while in captivity, in the kowledge that their liberty and their lives were tied to the victories of the Republic and to your personal glory. Today, they rejoice in the homage they wish to pay to their liberator. “

Before Georges Washington Lafayette returned to see his family for the first time in more than five years he first arrived in Paris. His father’s supporters arranged an audience to plead with Napoleon to end his father’s exile, but Napoleon had left to inspect the troops and his wife, Josephine, received the young man instead. Recognizing the advantages of cloaking her husband’s ambitions in Fayettiste republicanism, she received the boy, declaring, “Your father and my husband must take common cause.”

After long months of illness, Adrienne Lafayette made the trip to Paris in an attempt to revoke her husband’s exile, gain back their land and possibly: their titles. She gained back La Grange but still faced the task of removing his name from the emigres book, In mid-October, Bonaparte returned to France with another ship-load of loot. All Paris cheered and Adrienne stepped forward smartly, offering to add to his laurels by personally presenting the collective praises of the Prisoners of Olmutz if he would grant her an audience to do so. She won her counsel and received the pronouncement she had been hoping for: “You husband’s life, is bound to the preservation of the republic.”

Adrienne sent word to Lafayette to dispatch an obsequious letter to Napoleon–immediately. “Here is my letter for Bonaparte, I have followed your advice about making it short.”:

“My love of liberty and our nation… would have been enough to fill me with joy and hope at your arrival in France. To my concern for the public good, I add an enthusiastic and profound appreciation for my liberator. The welcome that you gave the prisoners of Olmutz has been reported to me by her whose life I owe to you I rejoice in my obligations to you, Citizen General, and in the happy conviction that to applaud your glory and hope for your success is a civic duty as well as an act of attachment and gratitude.”

Adrienne’s sense of timing could not of been better. On November 9th, ten days after she delivered her husband’s letter to Bonaparte, the Corsican stage another coup d’etat, suspending the constitution, dismissing the legislature and establishing dictatorial rule under a three man consulate. Adrienne took advantage of the confusion to obtain a passport with an assumed name for her husband and set a family friend racing north to Holland with instructions to return to France immediately. After Lafayette arrived in Paris, Adrienne urged him to notify Bonaparte and Talleyrand. Bonaparte flew into a rage and Talleyrand demanded that Lafayette return to Holland immediately, but Adrienne believed they were simply posing. She recognized it would be too impolitic to discard the political benefits as “liberator of the Prisoners of Olumtz” by expelling Lafayette–especially while trying to consolidate his control of the shaky new government. Napoleon needed to reconcile his feuding with other factions such as the Fayettiste republicans.

Adrienne offered Bonaparte a diplomatic solution: Lafayette would pledge his support for Bonaparte, then disappear from public life and retire into obscurity. Bonaparte saluted Madame Lafayette’s political skills and courage, “I am proud to know, Madame,” he told her, “you have a great deal of character and intelligence. but you may not fully understand the situation. The arrival of Monsieur de Lafayette embarrasses me… You may not understand me, madame, but General Lafayette, finding himself no longer in the center of things, will understand me… I implore him… to avoid all political activities. I rely on his patriotism.” Bonaparte agreed to allow Lafayette to say in France, but he would remain so illegally, still officially an emigre in exile, without French citizenship, and subject to summary arrest. If Lafayette refrained from all political activities, Napoleon pledged to eventually restore his citizenship.

In 1799, when he received word that George Washington had died, he was forced to remain in seclusion at La Grange, while Napoleon led a lavish memorial service at the invalidates in Paris. Not only did Napoleon not invite Lafayette, and omitted all mention of the American hero’s name. True to his word, Bonaparte quietly removed Lafayette’s name from the list of emigres and restored his French citizenship on March 1st, 1800–as he also did for Lafayette’s exiled friends.

September 30th, the older brother, Joseph Bonaparte helped negotiate a new treaty with the United States and invited Lafayette to lavish in the two day celebrations. In the course of the festivities, the younger brother of Joseph and the elder Lafayette stood face to face for the first time with Bonaparte was a young officer amid his troops.

The two men were twelve years apart but found much in common. Both were of noble birth, both superbly education, both fluent in Latin and through and versed in the words of all the philosophers of the Enlightenment. Both were brilliant military tacticians and leaders who earned unwavering loyalty from their men. Both were charming, skilled diplomats. But unlike Lafayette, Bonaparte eagerly seized power by whatever means he could whenever he had the opportunity.

According to Lafayette, Bonaparte sought to legitimize his dictatorship by offering Lafayette the ambassadorship to America, but Lafayette refused. “I am too American to go America in the role of a foreigner” he replied. Bonaparte resented Lafayette’s “disapproving, if not hostile attitude. No one likes to pass for a tyrant. General Lafayette seems to designate me as such.” Lafayette was quick to answer, “The silence of my retirement if the maximum of the deference; if Bonaparte were willing to serve the cause of liberty, I would be devoted to him. But I can neither approve an arbitrary government, nor associate myself with it.”

In a referendum during the summer of 1802, 3,658,000 Frenchmen voted to make Bonaparte “Consul for life” with Lafayette among the tiny majority of 9,000 who dared vote nay. Later, Napoleon awarded him the Legion of Honor and an appointment as a Peer of the Realm of the Senate. Lafayette’s rejection deeply insulted the emperor who retaliated by blocking all requests for promotion for Georges Washington Lafayette and his sons-in-laws while they were fighting in the army. They were all then forced to resign their commissions and all were angry with the emperor’s pettiness.

On April 19th, 1815, a courier arrived at La Grange with a message from Joseph Bonaparte, begging Lafayette to come to Paris immediately. Napoleon wanted to appoint Lafayette leader of the House of Peers–and, in effect, leader of the entire National Assembly. Although he felt an urge of excitement with taking on this role as a recall to leadership, he remained true and didn’t serve. “If my fellow citizens call me, I will not reject their confidence, but I will not reenter political life by the peerage or any other favor of the emperor.” Understandably, Napoleon was furious. “Everyone in the world has learned his lesson, with the single exception of Lafayette. He had not yielded a jot. You see him calm. Well, let me tell you, he is ready to begin again.”

After the Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon demanded the Chamber of Deputies vote him emergency dictatorial powers and dissolve. Lafayette protested and Napoleon’s brother Lucien accused him of disloyalty which Lafayette denied. “This is a slanderous accusation. What gives the previous speaker [Lucien] the right to accuse this nation of being disloyal for failing to persevere in following the Emperor? The nation had followed him in the sand of Egypt, in the steppes of Russia, on fifty fields of battle, in his reverses as in his successes… and for having thus followed him we now mourn over the blood of three million Frenchmen!” That evening, Lafayette made a motion “that we all got to the Emperor and say to him that… his abdication has become necessary to save the nation.” The Chamber agreed, but Bonaparte rejected their demand. Napoleon abdicated in favor of his son Napoleon II and Lafayette was responsible for arranging passage to America for the Corsican.

44 notes

·

View notes