#O.W. Gurley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

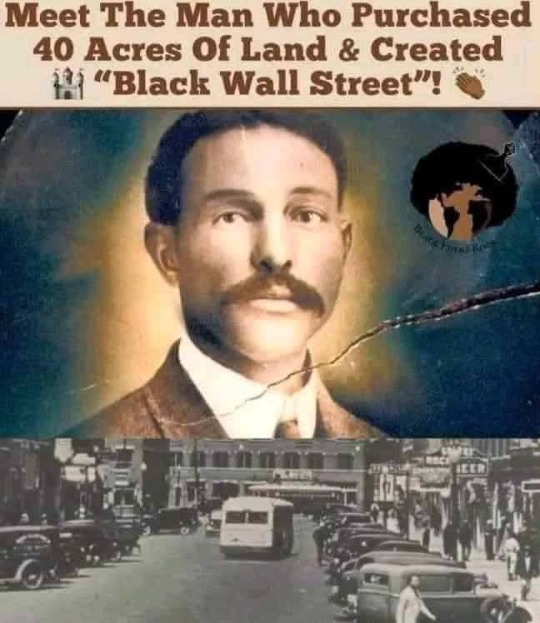

You might have heard of Black Wall Street. Meet the founder, O.W. Gurley.

In 1905 Gurley and his wife sold their property in Noble County and moved 80 miles to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Avenue. He subdivided his plot into residential and commercial lots and eventually opened a grocery store.

As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 in a city with a total population of 72,000. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington.

Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards and theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church.

#Queued#Black Wall Street#O.W. Gurley#Ottowa Gurley#Gurley#Tulsa#North Tulsa#Greenwood Avenue#Greenwood#Tuskegee#Booker T. Washington#Booker T Washington#Vernon AME Church#Black History Month#Black History

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

You might have heard of Black Wall Street. Meet the founder, O.W. Gurley.

In 1905 Gurley and his wife sold their property in Noble County and moved 80 miles to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Avenue. He subdivided his plot into residential and commercial lots and eventually opened a grocery store.

As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 in a city with a total population of 72,000. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington.

Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards and theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church.

Source: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/o-w-gurley-1868-1935/

515 notes

·

View notes

Text

You might have heard of Black Wall Street. Meet the founder, O.W. Gurley.

In 1905 Gurley and his wife sold their property in Noble County and moved 80 miles to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Avenue. He subdivided his plot into residential and commercial lots and eventually opened a grocery store.

As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 in a city with a total population of 72,000. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington.

Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards and theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church.

Source: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/o-w-gurley-1868-1935/

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

You might have heard of Black Wall Street. Meet the founder, O.W. Gurley.

In 1905 Gurley and his wife sold their property in Noble County and moved 80 miles to the oil boom town of Tulsa. Gurley purchased 40 acres of land in North Tulsa and established his first business, a rooming house on a dusty road that would become Greenwood Avenue. He subdivided his plot into residential and commercial lots and eventually opened a grocery store.

As the community grew around him, Gurley prospered. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area he had purchased grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 in a city with a total population of 72,000. The Black community had a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who provided services to them. Soon the Greenwood section was dubbed “Negro Wall Street” by Tuskegee educator Booker T. Washington.

Greenwood, now called Black Wall Street, was nearly self-sufficient with Black-owned businesses, many initially financed by Gurley, ranging from brickyards and theaters to a chartered airplane company. Gurley built the Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood and rented out spaces to smaller businesses. His other properties included a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood, which housed the Masonic Lodge and a Black employment agency. He was also one of the founders of Vernon AME Church.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

O.W. Gurley (Ottaway W. Gurley; December 25, 1867 – August 6, 1935) was once one of the wealthiest African American men and a founder of the Greenwood district in Tulsa known as “Black Wall Street”.

He was born in Huntsville and grew up in Pine Bluff. He worked as a teacher and in the postal service. He came to Oklahoma Territory to participate in the Land Run of 1893, staking a claim in what would be known as Perry, Oklahoma. He resigned from an appointment under President Grover Cleveland to strike out on his own.” He ran unsuccessfully for treasurer of Noble County, but he became principal at the town’s school and started operating a general store for 10 years.

He sold his store and land and moved to the oil boomtown of Tulsa, where he purchased 40 acres of land which was “only to be sold to colored.” The first law passed in the new State of Oklahoma, set in place a Jim Crow system of legally enforced segregation, and required African Americans and whites to live in separate areas. Oklahoma was considered a significant economic and social opportunity by him, politicians, and others, leading to the establishment of 50 all-African American towns and settlements, among the highest of any state or territory.

His first business was a rooming house which was located on a dusty trail. This road was given the name Greenwood Avenue, named for a city in Mississippi. He provided monetary loans to African American people wanting to start their businesses.

He built three two-story buildings and five residences and bought an 80-acre farm in Rogers County. He founded Vernon AME Church. He helped build an African American Masonic lodge and an employment agency.

He formed an informal partnership with another American American entrepreneur, J.B. Stradford. He was made a sheriff’s deputy by the city of Tulsa to police Greenwood’s residents. He owned more than one hundred properties in Greenwood and had an estimated net worth between $500,000 and $1 million, he lost nearly $200,000 in the 1921 race massacre. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Video

youtube

2 Black Business Icons Who Built EMPIRES from Nothing: O.W. Gurley & Reg...

0 notes

Video

youtube

2 Black Business Icons Who Built EMPIRES from Nothing: O.W. Gurley & Reg...

0 notes

Video

youtube

"Rise of Black Wall Street: The Inspiring Story of O.W. Gurley and Green...

0 notes

Text

"Rise of Black Wall Street: The Inspiring Story of O.W. Gurley and Green...

youtube

0 notes

Photo

THIS IS A PIVOTING POINT IN HISTORY

IT SHOW WHAT A BLACK COMMUNITY CAN DO GIVEN THE CHANCE

AND

WHAT A WHITE COMMUNITY CAN DO GIVEN A CHANCE

WE MUST LEARN FROM HISTORY AND ACT ON THE KNOWLEGE TO IMPROVE OR CONTINUE TO LIVE WITH THE DAMAGES IN THE WORST WAY.

One hundred years ago on May 31, 1921, and into the next day, a white mob destroyed Tulsa’s burgeoning Greenwood District, known as the “Black Wall Street,” in what experts call the single-most horrific incident of racial terrorism since slavery.

HOW BLACK WALL STREET STARTED

A BLACK MAN’S DREAM WHO UNDERSTOOD THE POWER OF THE BLACK DOLLAR IN A BLACK COMMUNITY-

IT WAS BLACK ON BLACK DIME NOT CRIME

O.W. Gurley, a wealthy Black landowner, purchased 40 acres of land in Tulsa in 1906 and named the area Greenwood. Its population stemmed largely from formerly enslaved Black people and sharecroppers who relocated to the area fleeing the racial terror they experienced in other areas.

O. W. Gurley (born Ottaway W. Gurley; December 25, 1867 – August 6, 1935) was once one of the wealthiest Black men and a founder of the Greenwood district in Tulsa, Oklahoma, known as "Black Wall Street"

Gurley was born in Huntsville, Alabama to John and Rosanna Gurley, formerly enslaved persons, and grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. After attending public schools and self-educating he worked as a teacher and in the postal service. While living in Pine Bluff, Gurley married Emma Wells, on November 6, 1889. They had no children.

In 1889, he came to what was then known as Indian Territory to participate in the Oklahoma Land Rush, staking a claim in what would be known as Perry, Oklahoma. The young entrepreneur had just resigned from an appointment under president Grover Cleveland in order to strike out on his own. In Perry he rose quickly, running unsuccessfully for treasurer of Noble County at first, but later becoming principal at the town’s school and eventually starting and operating a general store for 10 years.

Greenwood District

In 1905, Gurley sold his store and land in Perry and moved with his wife, Emma, to the oil boomtown of Tulsa, where he purchased 40 acres of land which was "only to be sold to colored. The first law passed in the new State of Oklahoma, 33 days after statehood, set in place a Jim Crow system of legally enforced segregation, and required blacks and whites to live in separate areas.

However, Oklahoma was considered a significant economic and social opportunity by Gurley, politician Edward P. McCabe and others, leading to the establishment of 50 all-black towns and settlements, among the highest of any state or territory.

Among Gurley's first businesses was a rooming house which was located on a dusty trail near the railroad tracks. This road was given the name Greenwood Avenue, named for a city in Mississippi. The area became very popular among black migrants fleeing the oppression in Mississippi.

They would find refuge in Gurley's building, as the racial persecution from the south was non-existent on Greenwood Avenue. On the contrary, Greenwood was later dubbed Black Wall Street as it became increasingly self-sustained and catered to upwardly mobile Black people] Gurley also provided monetary loans to Black people wanting to start their own businesses.

In addition to his rooming house, Gurley built three two-story buildings and five residences and bought an 80-acre (32 ha) farm in Rogers County. Gurley also founded what is today Vernon AME Church He also helped build a black Masonic lodge and an employment agency.

This implementation of "colored" segregation set the Greenwood boundaries of separation that still exist:

PART 1 OF 3

BLACK PARAPHERNALIA DISCLAIMER

IMAGES FROM GOOGLE IMAGE

Gurley formed an informal partnership with another Black American entrepreneur, J.B. Stradford, who arrived in Tulsa in 1899, and they developed Greenwood in concert. In 1914, Gurley's net worth was reported to be $150,000 (about $3 million in 2018 dollars). And he was made a sheriff's deputy by the city of Tulsa to police Greenwood's residents, which resulted in some viewing him with suspicion.

By 1921, Gurley owned more than one hundred properties in Greenwood and had an estimated net worth between $500,000 and $1 million (between $6.8 million and $13.6 million in 2018 dollars). Gurley's prominence and wealth were short lived, and his position as a sheriff's deputy did not protect him during the race massacre. In a matter of moments, he lost everything

During the race massacre, The Gurley Hotel at 112 N. Greenwood, the street's first commercial enterprise as well as the Gurley family home, valued at $55,000, was lost, and with it Brunswick Billiard Parlor and Dock Eastmand & Hughes Cafe. Gurley also owned a two-story building at 119 N. Greenwood. It housed Carter's Barbershop, Hardy Rooms, a pool hall, and cigar store. All were reduced to ruins. By his account and court records, he lost nearly $200,000 in the 1921 race massacre

Because of his leadership role in creating this self-sustaining exclusive black "enclave," it has been rumored that Gurley was lynched by a white mob and buried in an unmarked grave. However, according to the memoirs of Greenwood pioneer, B.C. Franklin, Gurley left Greenwood for Los Angeles, California.

O.W Gurley and his wife, Emma, moved to a 4-bedroom home in South Los Angeles and ran a small hotel. Gurley died from arteriosclerosis and a cerebral hemorrhage, in Los Angeles, California, on August 6, 1935, at the age of 67. His widow Emma passed away three years later, in 1938. (Source: Wikipedia)

BLACK PARAPHERNALIA DISCLAIMER

IMAGES FROM GOOGLE IMAGE

#black paraphernalia#black wall street#O.W. Gurley#black wealth#how greenwood got started#did you know

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Late, but ever poignant.

June 1st, 1921 will forever be remembered as a day of great loss and devastation. It was on this day that America experienced the deadliest race riot in the small town of Tulsa, Oklahoma. 97 years later, that neighborhood is still recognized as one of the most prosperous African American towns to date.

In the early 1900s, many African Americans migrated from southern states hoping to escape the harsh racial tensions while profiting off of the oil industry. Yet even in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Jim Crow laws were at large, causing the town to be vastly segregated. From that segregation grew a Black entrepreneurial mecca that would affectionately be called “Black Wall Street”. The town was established in 1906 by entrepreneur O.W. Gurley, and by 1921 there were over 11,000 residents and hundreds of prosperous businesses, all owned and operated by Black Tulsans and patronized by both whites and Blacks.

The attack that took place in 1921 (motivated largely by jealousy and an unconfirmed sexual assault accusation made by a white woman against a Black man) tore the community apart, claiming hundreds of lives and sending the once prosperous neighborhood up in smoke.

Read more at: www.officialblackwallstreet.com/black-wall-street-story

503 notes

·

View notes

Photo

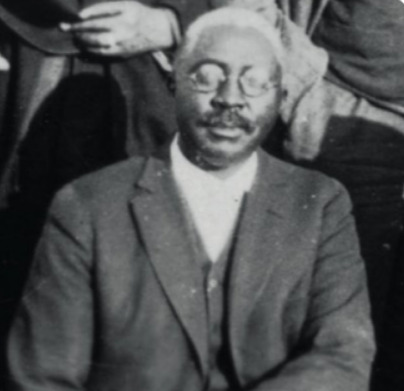

Black History Month Spotlight: J.B. Stradford

John B. Stradford (J.B.) was born in 1861 in Versailles, Kentucky to J.C. Stradford, a former slave. J.B. attended the Oberlin Preparatory Department (much like a modern day high school or secondary school) from 1882-85 and did not graduate. He went on to attend the Indianapolis School of Law, graduating in 1899.

Soon after receiving his law degree, J.B. Stradford had multiple interests in the social growth of Black Americans and Native Americans, real estate, and the oil boom in America. This led him to Tulsa, Oklahoma. He was admitted to the Oklahoma bar after arriving around 1899.

Not long after Stradford made his way to Tulsa, O.W. Gurley began developing an area in Tulsa for Black owned businesses, naming the main avenue “Greenwood.” Greenwood would soon be known as Black Wall Street, allowing Black citizens to participate in the American dream and grow their businesses and their wealth.

Stradford’s interest in real estate led him to build an over 50 room hotel on Greenwood Ave. in Tulsa, and it was the largest Black owned and Black operated hotel at the time. Stradford also owned the Stradford Library and the Stradford Building in the Greenwood area.

Unfortunately, racial tensions were growing in the south and struck Tulsa on May 30, 1921, when a Black man was accused of assaulting a white woman. This accusation has never been proven, but was enough for a fight to break out that evening. On June 1, white mobs descended on Greenwood, burning buildings and even dropping bombs from airplanes. Stradford’s businesses and real estate were destroyed, along with most of the Greenwood area.

Stradford was arrested for inciting violence during the race riots, and his son, C.F. Stradford (Oberlin College A.B. 1912) filed a writ for his release. J.B., fearing for his life, never paid bail upon release and escaped, eventually settling in Chicago and never returning to Tulsa. He died in 1935

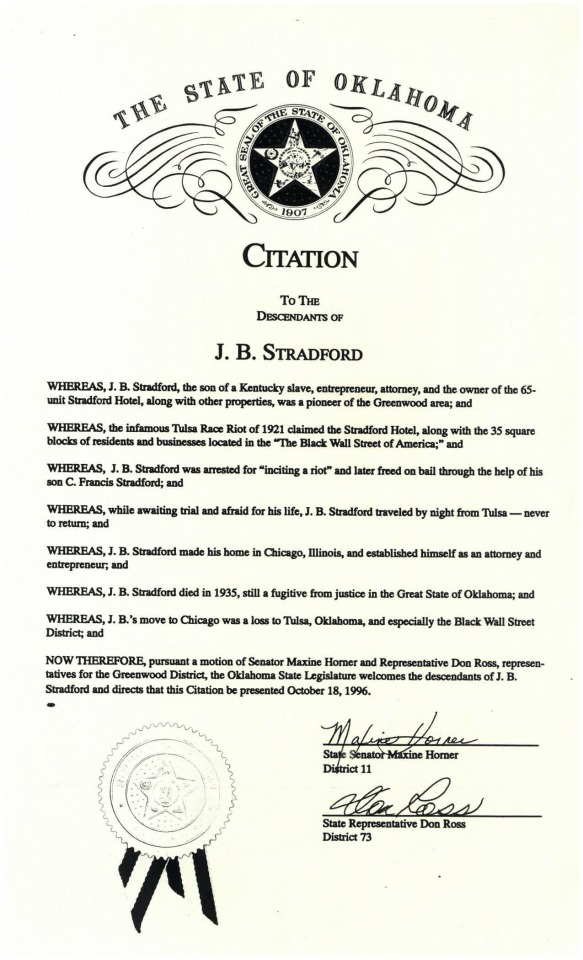

Thanks to the efforts of J.B. Stradford’s family, including his granddaughter Jewel (Stradford) LaFontant-MANkarious (Oberlin College A.B. 1943), a Tulsa jury found Stradford innocent of all charges for inciting a riot, and Oklahoma governor Frank Keating gave Stradford a posthumous executive pardon in 1996.

(Citation given to the Stradford family, recognizing J.B. Stradford’s achievements on the day of his executive pardon, October 18, 1996. From the Jewel LaFontant-MANkarious papers, Oberlin College Archives)

More information about the notable Stradford family can be found in the papers of Jewel LaFontant-MANkarious, held in the Oberlin College Archives. Jewel’s own career as a lawyer, United Nations Ambassador, and other United States government positions is well documented in the collection

#Oberlin#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Archives#Oberlin College Libraries#JB Stradford#Stradford Family#Black Wall Street#Tulsa#Greenwood#Archives#Oklahoma

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

John “the Baptist” Stradford

John B (for the Baptist) Stradford was born a free man in Versailles, Kentucky in 1861. His father, J.C. Stradford was a former slave who had been emancipated and was living in Stradford, Ontario (Canada) but who returned to the U.S. and was in Versailles when his son was born. Not much is known about J. B. Stradford’s his early life before his graduation from Oberlin College in 1896, and Indiana Law School in 1899. Stradford was a shrewd businessman. While living in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, and St. Louis, Missouri, he ran pool halls, bathhouses, shoeshine parlors and boarding houses. Stradford migrated to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) in 1899 with his wife Augusta, and settled in the newly found town of Tulsa, eventually becoming one of the most prominent individuals in the town.

He got involved in the building of the all-black Greenwood section of Tulsa with another early settler, O.W. Gurley, as they both built fortunes in real estate and rental units. By World War I, Greenwood had become what many called the “Black Wall Street of America,” meaning it was one of the most prosperous concentrations of black businesses of any community in the nation. Its booming economy was based on a large working class of African American men and women who supported numerous businesses.

Stradford also became a civil rights activist for local African Americans. He filed a lawsuit against the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway company for failing to provide proper accommodations for black travelers, and he publicly opposed lynching and many of the new Jim Crow laws enacted when Oklahoma became a state in 1907.

On June 1, 1918 Stradford opened the luxurious fifty-four room Stradford Hotel at 301 N. Greenwood Avenue. It was the largest black owned and operated hotel in Oklahoma and one of the few black-owned hotels in the United States. The Stradford had a dining hall, a gambling room, a saloon, and a large hall for events such as live music. By 1920 Stradford had become the richest black man in Tulsa, owning over fifteen rental properties and an apartment building, along with the hotel.

When the Tulsa Massacre began on June 1, 1921, where an estimated 300 blacks were killed by white rioters, Stradford stood in front of his hotel armed with a rifle until he was overwhelmed by the white mobs that had invaded the community. Eventually the entire black commercial district, all the buildings along a thirty-four-block area on and near Greenwood Avenue, were destroyed including the Stradford Hotel. Although the damage was clearly done by white mobs, Stradford and twenty other black people were indicted for inciting a riot. Stradford’s son, attorney C.F. Stradford posted bail but fearing for his life, Stradford jumped bail and escaped to Independence, Kansas before finally settling in Chicago, Illinois. For the next few years, he and his son fought his extradition to Tulsa.

While in Chicago Stradford formed a group of investors to build a new luxury hotel but the project ran out of money and the building was never completed. He did own a candy store, barbershop and a pool hall but he never duplicated his success in Tulsa. J.B. Stradford died in Chicago on December 22, 1935. In 1996, a Tulsa jury acquitted Stradford of all charges relating to the Tulsa Race Riot.

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/john-the-baptist-stradford-1861-1935/

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

John the Baptist (J.B.) Stradford (September 10, 1861 - December 22, 1935) was born a free man in Versailles, KY. His father, J.C. Stradford was a former enslaved who had been emancipated and was living in Stradford, Ontario. Not much is known about his early life before he graduated from Oberlin College and Indiana Law School. He was a shrewd businessman. While living in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, and St. Louis, he ran pool halls, bathhouses, shoeshine parlors, and boarding houses. He migrated to Tulsa with his wife Augusta, becoming one of the most prominent individuals.

He got involved in the building of the all-Black Greenwood section of Tulsa with O.W. Gurley, as they both built fortunes in real estate and rental units. By WWI, Greenwood had become the “Black Wall Street of America”.

He became a civil rights activist. He filed a lawsuit against the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway Company for failing to provide proper accommodations for African American travelers, and he opposed lynching and many of the new Jim Crow laws enacted when Oklahoma became a state.

He opened the luxurious fifty-four-room Stradford Hotel. It was the largest African American-owned and operated hotel in Oklahoma and one of the few African American-owned hotels in the US. It had a dining hall, a gambling room, a saloon, and a large hall for events such as live music. He had become the richest African American man in Tulsa, owning over fifteen rental properties and an apartment building.

When the Tulsa Massacre began on June 1, 1921, he stood in front of his hotel armed with a rifle until he was overwhelmed by the white mobs. The entire Black commercial district was destroyed. He and twenty other African Americans were indicted for inciting a riot. His son, attorney C.F. Stradford posted bail, and he escaped to Independence, Kansas before settling in Chicago. They fought his extradition.

He formed a group of investors to build a new luxury hotel but the project ran out of money. He owned a candy store, barbershop, and a pool hall but he never duplicated his success. A Tulsa jury acquitted him of all charges relating to the Tulsa Race Riot. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Bombing of Black Wall Street

O.W. Gurley

On the night of May 13th, 1985, as Derek Davis has so eloquently documented in previous issues of The Chiseler, the Philadelphia Police Department dropped a packet of C4 explosives onto the West Philly house occupied by MOVE, a black radical group whose sociopolitical agenda was fuzzy at best. You should read Davis’ stories to more fully understand how and why this came to pass, but suffice it to say in the end eleven people in the house (including several children) were killed, and some sixty surrounding homes—an entire city block’s worth—were allowed to burn to the ground.

At noon on September sixteenth, 1920, a group of anarchists detonated a horse-drawn cart packed with explosives and shrapnel in the middle of Wall Street, killing thirty-eight capitalists and sending hundreds more to area hospitals.

Nine months after the Wall Street bombing and sixty-four years before MOVE, an incident which in a way echoed both events took place in Tulsa, Oklahoma, but with far more devastating results. The Bombing of Black Wall Street, as it was sometimes known, would go on to be just as forgotten, at least in white history books, as both the MOVE and Wall Street bombings.

In 1906, a wealthy black entrepreneur named O.W. Gurley moved from Arkansas to Tulsa, where he bought up forty acres of land on the northern outskirts of the predominately white town. He had a plan in mind, and would only sell parcels of the land to other African-Americans, especially those trying to escape the brutal economic conditions in Tennessee.

Within a decade, the resulting thirty-four square block community, which had been dubbed Greenwood, had evolved into one of the most affluent regions of the state, and certainly the wealthiest and most successful black-owned business district in the country. A few of the new residents had even struck it rich when oil was discovered nearby. Along with the grocery, clothing and hardware stores that lined the main commercial strip, Greenwood boasted its own schools, churches, doctors, banks, law offices, restaurants, movie theaters, a post office and a public transportation system. The houses had indoor plumbing, and, even that early in the history of aviation, six of the residents owned private airplanes. Thanks to Segregation laws which prohibited blacks from shopping in nearby Whites-Only stores, the African-American residents of Greenwood shopped at their own local stores, which kept money circulating in the community, only bolstering their economic strength.

By all accounts, the people who lived there were extremely proud of what they had forged, especially the school system, insisting each and every child of Greenwood receive a full and solid education.

Although generally referred to as “Little Africa” or “Niggertown” in the Tulsa Tribune, Tulsa World, and other local papers, the residents of Greenwood preferred to think of it as Black Wall Street, a nickname that has stuck to this day.

As you might imagine, the much poorer white residents in surrounding Tulsa resented the wealth and success of their black neighbors. This resentment was only fueled by the local papers, in particular the Tribune. Taking their lead from the local chapter of the Klan, more often than not the Tribune’s writers insisted, despite all evidence to the contrary, on caricaturing the residents of “Little Africa” as either stupid, shiftless, shuffling drunks or drug crazed, wild-eyed criminals and rapists running wild in the streets. Meanwhile, editorial writers over at the World even recommended conscripting the Klan to restore law and order to the community.

Combining the reality with the grotesque cartoon proved to be a poor white racist’s worst nightmare. Not only were those blacks in Greenwood subhuman, they were rich subhumans. Jesus God Almighty!

The simmering anger reached the boiling point on May 30th, 1921 when seventeen-year-old (and white) Sarah Page accused nineteen-year-old (and black) shoeshine man Dick Rowland of rape. Page worked as an elevator operator in Tulsa’s Drexel Building, and claimed Rowland attacked her while she was on the job. No one really knows to this day what happened in that elevator, but later investigators who’ve looked into the case genrtally agree there was no rape. Rowland would claim he either bumped into Page accidentally or stepped on her foot—he couldn’t remember. At the time it didn’t matter. The following morning’s Tribune ran a racially inflammatory, lurid account of the fictional crime in which they essentially declared Rowland guilty. A hearing was scheduled for that afternoon, and the paper further erroneously reported the gallows was already being built outside the courthouse for that night’s hanging.

Whether or not a rape had occurred was, to be honest, irrelevant. It was simply the easiest and cheapest way to rile up the angry white masses. If the paper had run an article about economic disparity and racial class resentment turned on its head, all it would have encouraged its white readers to do is flip forward to the sports section.

The residents of Greenwood understood this, and on the 31st, the day of the hearing, a group of men, some of them armed, showed up outside the courthouse in hopes of protecting Rowland. When they arrived they found themselves facing off with the much larger (and better-armed) angry white mob, there to ensure Rowland was hanged, trial or no trial.

Words were exchanged and a few scuffles broke out. A white man reportedly approached an armed African-American WWI vet, and demanded he hand over his gun. When the vet refused and the white tried to wrest it from him, the gun went off, and the riot was underway.

Realizing they were outnumbered, the mob from Greenwood retreated towards home, only to be pursued by the white mob, both on foot and in pickups.

It’s worth noting that the confrontation outside the courthouse had gone on for several hours before the few cops onhand to keep the peace finally called for backup. When all hell broke loose after that gunshot, the cops quickly began deputizing whites on the fly, giving them the authority to make arrests. A few did, and an internment camp set up at the local fairgrounds quickly began to fill. Most of the new deputies didn’t bother, and just started shooting.

As the white mob entered Greenwood, they immediately began looting and torching every building they passed. For the next twelve hours they rampaged through the neighborhood, whooping and hooting as they smashed windows, kicked in doors, took potshots at fleeing residents, and set fire to anything that wasn’t already ablaze. Several eyewitness reports claim two small planes flying over the community started dropping what some believe were kerosene bombs and others believe was dynamite on the already raging inferno. Firemen who arrived on the scene to douse the fires were turned back at gunpoint by the rioters.

The number of white families from nearby neighborhoods—a lot of mothers and children—who gathered around the edges of Greenwood to watch the carnage has led some to believe the attack was planned well in advance, likely by the Klan. They were just waiting for an excuse.

The National Guard arrived shortly before noon on June 1st, but by then most of the rioters had gone home. Along with trying to control the flames, the Guardsmen also began arresting Greenwood’s residents. By the time the fires were put out, all thirty-four square blocks of Black Wall Street had been burned to the ground. An estimated three hundred had been killed, another eight hundred hospitalized, ten thousand were left homeless, six thousand were being held in the internment camp at the fairgrounds, and six hundred businesses had been destroyed. No whites were arrested or charged for their role in the massacre.

Some of the dead, it was reported, were buried in mass graves, others dumped in a nearby river, and still others dropped into the shafts of a local coal mine.

The coverage of the destruction of Black Wall Street in the following day’s Tulsa World included the headlines “Fear of Another Uprising” and “Difficult to Check Negroes.” To this day, white media outlets continue to refer to the incident as “The Tulsa Race Riot,” when they refer to it at all. The Tribune quietly removed the front page story about the alleged rape from all their bound editions, and all police and fire department files about the incident mysteriously vanished.

The day after the riot, all charges were dropped against Dick Rowland (who had been safely hidden away in a jail cell throughout it all), and upon his release he quickly and quietly left town.

Only one of Black Wall Street’s buildings was left standing, and those who survived vowed they would rebuild. They did, too, to an extent, but they were never able to fully reclaim the spirit and status the community once had. Making things more difficult, Greenwood was in a prime location in terms of business expansion. City politicians, anxious to reclaim that land, began devaluing Greenwood property, hoping they might encourage residents to sell out and move far away.

Ironically, the real death blow to Black Wall Street came when Segregation was overturned in Oklahoma in the late ’50s and early ’60s, and most Greenwood residents decided they were happy to take their business to formerly whites-only stores.

Seventy-five years after the massacre, the state of Oklahoma ordered an investigation into the events of May 31st-June 1st, 1921. When the investigation ended in 2001, it was suggested a scholarship fund be set up, and reparations be paid to the families of the victims. A few scholarships were handed out before the program was discontinued three years later, but no reparations were ever paid.

by Jim Knipfel

6 notes

·

View notes