#North American armadillos

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Armadillos Don’t See Well, but They Have a Great Nose

Taking a Break On one of my recent trips to Watermelon Pond a pretty little nine banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) found me. I was hiking through the woods towards the water when it happened along. I say it found me because it came out of some heavy underbrush into the more open area where I was walking. It looked around, never saw me, and began to follow its nose around in search for some…

View On WordPress

#armadillo encounters#armadillo photographs#armadillos#Florida armadillos#Florida mammals#Florida small mammals#interesting mammals#mammal photographs#mammals#nine banded armadillos#North American armadillos#photography#small mammals#unusual mammals#wild mammals#wildlife#wildlife photographs#wildlife photography

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#animal polls#poll blog#my polls#north american wildlife#central american wildlife#south american wildlife#wildlife#armadillo#nine-banded armadillo#Cingulata#mammalia#mammals#mammal

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

uhhhhhh no it isn't

#i genuinely have no idea why people think armadillos live in north american deserts#like they spill over into west texas a bit but they're way more prevalent in the south

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.youngnatureexplorers.com/armadillo-facts/

Armadillos are the only living mammals with bony shells.

This newcomer to the United States has spread from Mexico over the past 150 years. People have helped extend its range by transplanting it, possibly as food. It was deliberately introduced to Florida in the 1920’s and, mostly on its own, proceeded to become established over much of the state. Around the same time, Louisiana started to see a large number of armadillos. They are now found throughout the state.

In some cultures, armadillos have been consumed for centuries. The meat is said to taste like chicken or pork and may be cooked in various ways, such as grilling, stewing, or roasting.

Armadillos can carry diseases such as leprosy (Hansen’s disease), which can be transmitted to humans through direct contact with infected animals.

0 notes

Text

I was thinking about Redwall, and how it's kind of a shame that (iirc) they're sort of locked into being animals from Europe, when there's interesting little animals all over the world, when I had an idea

Au where Redwall is set in South America. Imo it would work surprisingly well...?

Anyways, rambles on species and such below

Badgers- while maybe not as aggressive as badgers, size wise they'd have to be Capybaras. I can't remember if their digging is as important as that of other species, but if so then a species of armadillo, maybe the Screaming Hairy Armadillo. Or...maybe a porcupine? Maybe a Grison?

Bats- multiple species in South America of course, but Vampire bats are extra fun

Dormice- are not native to South America, so I propose that a type of opossum could take their place, maybe the bushy tailed opossum. They're more closely related to squirrels though, so maybe the Neotropical Pygmy Squirrel, or another species of dwarf squirrel.

Hares- sadly no hares in South America, but there are a few species of rabbit. Rather than that, what would be more fitting of the boisterous personality would be some sort of monkey honestly? And they form troops, so that's neat . Maybe a Mara? They're somewhat hare-like

Hedgehogs- again, old-world exclusive. Closest relative would be some shrew species. Personality wise I'd go with a Caenolestid, idk they just have the same vibe

Mice- there are so many different species of mice in that every mouse character could probably be a different species from one another, lol

Moles- no moles in South America, so...there is one species of pocket Gopher, Thaeler's Gopher, and I think they'd be a suitable replacement

Otters- Giant otters easily.

Rabbits- see hare section.

Seals- I completely forgot they showed up in the series at all. I'd go with South American Fur seals probably

Shrews- plenty in South America, even marsupial shrews if you'd like

Squirrels- lots in South America as mentioned previously. Maybe focus on climbing and they could also become some sort of primate

Voles- seem to not be present in South America? Maybe replace them with a coypu because of their water habits, or Guinea Pigs just because

Cats- since in the books they're wildcats rather than domestic ones, they'd be some of the many smaller wild cats in South America, maybe Pampas cats or Geoffroy's cat.

Ermines- appear so rarely I'd just have them be actual ermines from up north

Ferrets- maybe replace them with Crab-eating Raccoons? Or one of the native species of skunks?

Foxes- already in South America , pick any species you want

Pine Martens- another one you could fold into weasels, or go with a Coati or something

Rats- lots already, go wild

Sable- again, make 'em weasels or go crazy...maybe these guys are actually Tayras.

Stoats- yet another weasely guy.

Weasels- finally. They're just weasels. There are multiple weasel species in South America

Wolverines- same with the ermines, have them be actual wolverines

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

North American Animal Character Asks

Feel free to change pronouns as necessary, and remember to specify muse for multimuse blogs.

CW: Murder mention

—

[American Eel] - What is the scummiest thing your muse does?

[Bald Eagle] - What does your muse dedicate themselves to wholeheartedly?

[Nine-Banded Armadillo] - Does your muse get overlooked often? How do they feel about their social standing?

[Elk] - Does your muse like to exercise? What is their favorite thing to do at the gym?

** [Canada Lynx]** - What weather is your muse's favorite? Least favorite?

[American Alligator] - When your muse is in a place they shouldn't be in or a situation that makes them uncomfortable, what is their first instinct?

[Moose] - What is your muse's pain tolerance like?

[Mountain Goat] - What would your muse kill for?

[Gila Monster] - Is there something about your muse that people don't expect?

[American Bison] - Does your muse like to be left alone?

[Pronghorn] - Where can your muse be found frequently that isn't their home or place of work?

[Grizzly Bear] - What is their sleep schedule like?

[Arctic Wolf] - What are your muse's ideal surroundings? What is the temperature? Do they have certain scents there? Describe their happy place.

[Beaver] - Does your muse like to work with their hands? Why or why not?

[American Flamingo] - Does your muse like to blend in or stand out?

#roleplay memes#rp memes#writing prompts#headcanon meme#headcanon memes#headcanon asks#headcanon ask#character asks#character ask#askbox meme#inbox meme#ask meme

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

It should come as no surprise that Nigella Lawson, who nicknamed her microwave the mee-cro-wah-vay and regularly refers to pomegranate seeds as “ruby jewels,” has her own name for rugelach: scuffles.

“Scuffles,” the British television cook and proclaimed food writer explains in a recent YouTube recipe tutorial, “is the really delightful American name for an even more delightful Ukrainian pastry, rohalyky. Now if you’ve ever encountered rugelach, you’ll know what they are, but think like doll’s-house-sized croissants.”

So much to unpack here.

As a Brit, I regularly have to turn to my North American colleagues for insight into the food habits and psyche of those across the pond, but only a few had heard of scuffles. Hmm. Further research online revealed that scuffles are a fairly popular Canadian Christmas pastry. A rugelach by any other name would taste as sweet, I concluded, and moved on.

… But not very far.

I was as thrown by the term “scuffles” as I was by Nigella’s pronunciation of rugelach, with its long “oo” like in “arugula,” which is different to the way it’s typically pronounced in the U.K.: rog-a-lach. Ultimately, I reasoned that we’re probably all pronouncing it wrong and there was no need to be petty.

Regional differences resolved, I whiled away a happy hour researching the origins of rugelach and their relationship to Ukranian rohalyky. Turns out, they’re essentially the same pastry, which has long been enjoyed across Eastern Europe by non-Jews and Jews, who called them “rugelach” in Yiddish.

Finally, I addressed Nigella’s description: “doll’s-house-sized croissants,” concluding it’s a bit of a stretch given that 1) her recipe does not call for a laminated dough, 2) you rarely come across cinnamon croissants and 3) neither rohalyky nor rugelach are French. Later in the video, Nigella likens her scuffles to “miniature armadillos,” which if you squint, or live inside Lawson’s kitschy brain (and how I often wish I did), is much more plausible.

Still with me? (Fellow Virgos, I know you are.) Time to dissect Nigella’s recipe, which you can find on the website of upmarket British online grocery store, Ocado.

In a pleasant turn of events, I have few complaints. The scuffles are easier and simpler than most rugelach recipes I’ve come across; on the video tutorial, Nigella even makes the pastries by hand, no mixer required. And you could argue that Nigella’s scuffles are a gratifying hybrid of American- and Isreali-style rugelach. Like Israeli rugelach, she adds yeast to her dough — but unlike the babka-esque Israeli dough, hers doesn’t need to rise. Like American rugelach, she enriches her dough, calling for sour cream rather than the typical cream cheese.

And then, in true Nigella style, she ever-so casually turned my world upside down.

After chilling for an hour or two, ’twas time to roll out the dough — but not in flour. No, in a technique that Lawson correctly calls “fascinating and revelatory,” she rolls out each quarter of dough in cinnamon sugar.

“Geometrists, please turn away because I’m going to describe this as a circle,” Nigella quips as she displays a sparkling disc encrusted in warm, scented sugar (I imagine she might say), which she then cuts, pizza-style, into small triangles (Nigella, use a pizza cutter not a knife, it’s much easier!), rolls up into “enchanting” pastries that may or may not resemble “teeny-tiny croissants” (see above), and bakes.

Having told us her recipe feeds a crowd (64 scuffles, to be exact), which I think we can all agree is very Jewish, Nigella then recommends serving the pastries with ice cream, which is… not very Jewish.

Sadly, as with the entire Ocado YouTube series, we do not get to see Nigella eating a scuffle, nor even sneaking into the kitchen in the middle of the night in a silk nightgown to snatch a couple from the jar. But in the absence of a television show (how much longer must we wait for you to grace our screens once again, Nigella?), this will have to do.

I’ll pass on the ice cream but — just as I always cover my rising bread dough with a leopard-print shower cap and double-butter my toast (once when the toast is warm, so it melts; once when the toast is a little cooler, so it coats the surface) — I shall, forevermore, roll out my rugelach dough in cinnamon sugar, just like Nigella does.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

the commercial building west of San Felasco State Park, December 15, 2024

There is a building west of San Felasco State Park, and the Medium Armadillo has been monitoring it every day for the last month. A wise owl told him that memories are manufactured there, and the Medium Armadillo thinks that sounds suspicious. What is someone trying to hide that they are manufacturing memories? The Medium Armadillo wants to do something about it. Maybe he’ll break in someday.

His father, the Giant Armadillo, thinks that the building looks like the work of humans, and it is better to stay away from humans. Every day they have to put up with bicyclists, and every full moon; and in the dead of winter they appear in droves as some sort of mid-hibernation ritual. It was a step forward when the harvest man left.

The Medium Armadillo thinks his father could stand to have some curiosity. Armadillos are not known for their intelligence, the way the great horned owl is, or the coyote, or the red-shouldered hawk, or the twin-flagged jumping spider, or the golden silk spider, or the double-crested cormorant, or the white ibis, or the Eastern indigo snake, or the green anole, or the American green tree frog, or the white-tailed deer, or the Eastern grey squirrel, or the alligator, or of course the anhinga. But maybe with some curiosity the Medium Armadillo could change that. What secrets could he learn by exploring the building? And they're probably doing something evil, and he could stop them. Perhaps by ramming into their equipment with his hard skin. Or eating all the termites that work for the humans.

And he’d no longer be living in the shadow of his father anymore if he took control of the memory factory.

But tonight the Medium Armadillo is not spying on the building. He is having a good rest in his warm burrow after a pleasant meal of ants with friends.

There’s little activity in the commercial building right now. The crickets are hibernating and the lone star ticks are in diapause, and Florida woods cockroaches are staying warm in the dwellings of man, which is a cockroach's best friend. It’s a full moon, which means that the Friends of San Felasco Community Support Organization is holding their night ride in five days, and the werepanthers are roaming the banks of the Santa Fe River to the north. The hay bales abandoned by the harvest man are singing their sad song. The one-eyed algae monster is eating holes in the ground, preparing his next sinkhole. The creeks are gossiping and the legend of a dead 16th century explorer is waiting to be revived by a vulnerable youth.

Spring is coming and soon the days will be longer again.

#local mysteries#gainesville#florida#magical realism#dream core#poem and photo feed#photography#poetry#my art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Speculative Animals

Quadropedis Gigaavis

Sapient pig

Giant Goose

The Aboropod

Flumenequus

Giant Armadillo

Future Sloths

The North American Cupacabra (Carnotroel ambulapterya)

Callidusavis

u/TortoiseMan20419

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

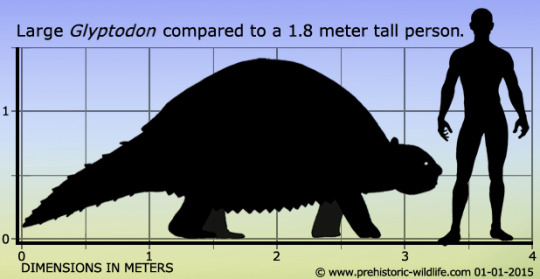

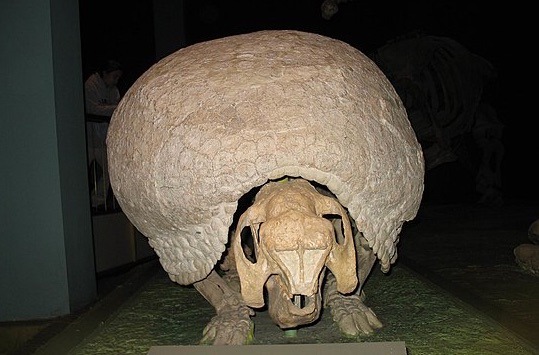

Glyptodon

(temporal range: 3.200-0.011 mio. years ago)

[text from the Wikipedia article, see also link above]

Glyptodon (from Greek for "grooved or carved tooth": γλυπτός "sculptured" and ὀδοντ-, ὀδούς "tooth")[1] is a genus of glyptodont (an extinct group of large, herbivorous armadillos) that lived from the Pliocene, around 3.2 million years ago,[2] to the early Holocene, around 11,000 years ago, in Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Argentina, and Colombia. It is one of, if not the, best known genus of glyptodont. Glyptodon has a long and storied past, being the first named extinct cingulate and the type genus of the glyptodonts. Fossils of Glyptodon have been recorded as early as 1814 from Pleistocene aged deposits from Uruguay, though many were incorrectly referred to the ground sloth Megatherium by early paleontologists.

The type species, G. clavipes, was described in 1839 by notable British paleontologist Sir Richard Owen. Later in the 19th century, dozens of complete skeletons were unearthed from localities and described by paleontologists such as Florentino Ameghino and Hermann Burmeister. During this era, many species of Glyptodon were dubbed, some of them based on fragmentary or isolated remains. Fossils from North America were also assigned to Glyptodon, but all of them have since been placed in the closely related genus Glyptotherium. It was not until the later end of the 1900s and 21st century that full review of the genus came about, restricting Glyptodon to just five species under one genus.

Glyptodonts were typically large, quadrapedral (four-legged), herbivorous armadillos with armored carapaces (top shell) that were made of hundreds of interconnected osteoderms (structures in dermis composed of bone). Other pieces of armor covered the tails and skull roofs, the skull being tall with hypsodont (high-crowned) teeth. As for the postcranial anatomy, pelves fused to the carapace, an amalgamate vertebral column, short limbs, and small digits are found in glyptodonts. Glyptodon reached up to 2 meters (6.56 feet) long and 400 kilograms (880 pounds) in weight, making it one of the largest glyptodonts but not as large as its close relative Glyptotherium or Doedicurus, the largest known glyptodont. Glyptodon is morphologically and phylogenetically most similar to Glyptotherium, however they differ in several ways. Glyptodon is larger on average, with an elongated carapace, a relatively shorter tail, and a robust zygoma, or cheek bone.

Glyptodonts existed for millions of years, though Glyptodon itself was one its last surviving members. Glyptodon was one of many South American megafauna, with many native groups such as notoungulates and ground sloths reaching immense sizes. Glyptodon had a mixed diet of grasses and other plants, instead living at the edge forests and grasslands where the shrubbery was lower. Glyptodon had a wide muzzle, an adaptation for bulk feeding. The armor could have protected the animal from predators, of which many coexisted with Glyptodon, including the "saber-tooth cat" Smilodon, the large dog relative Protocyon, and the giant bear Arctotherium.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Armadillos Like to Check Out Their Surroundings Often

Check it Out Even though they are covered in somewhat protective armor, nine banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) tend to be cautious little animals. They don’t see very well (look at how tiny those eyes are), but they have incredible noses. Frequently, before they go into an area, they will stop and smell the air as their way of looking out for predators. That’s what this little armadillo…

View On WordPress

#armadillo encounters#armadillo photographs#armadillos#cautious mammals#cute mammals#Florida armadillos#Florida mammals#mammal photographs#mammal photography#mammals#nine banded armadillos#North American armadillos#North American mammals#photography#wildlife#wildlife photographs#wildlife photography

0 notes

Text

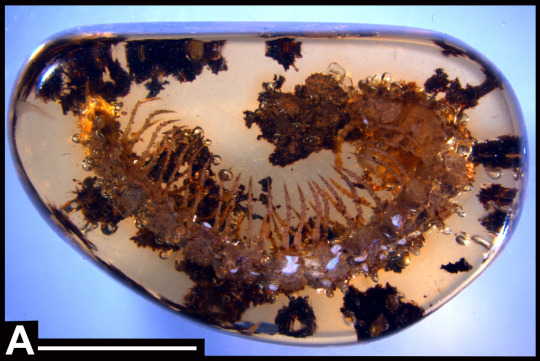

National Fossil: Mexico

It was a very tight race for the title of National Fossil of Canada, but in the end Anomalocaris (28,3 %) won over Tiktaalik (26,7 %) and Borealopelta (23,3 %). So this week you can vote on what should be Mexico‘s National Fossil.

Again: it could be a fossil that is just exceptionally well preserved and beautiful, had a huge impact on paleontology and our knowledge of the past, is very common/representative of the area, is beloved and famous in the public eye, is just a very unique and interesting find, or has any other justification.

My suggestions:

Mexican Amber: Okay, this one isn‘t technically a fossil, but I think amber is always a very unique window into the past, showing us exceptionally well preserved specimen of some the tiny and fragile things that often get overlooked. Mexican amber is from the Miocene and many insects and other arthropod species have been described from it

Columbian mammoth: Very recently the largest known fossil site for mammoths (Mammoth Central) has been discovered during airport constructions near Mexico city. More than 200 specimen have been found here, which is more than 3 times the amount of material found in the next biggest site

Eremotherium: One of the biggest ground sloths ever, they are among the originally South American animal groups that established themselves in North America after the two continents connected (Art by Gabriel Ugueto)

Glyptotherium: The giant armored armadillo-cousin is another one of the animals that migrated into North America after it connected to South America

Megalodon: There are many marine fossil sites in Mexico and some include Megalodon, the famous extinct shark and terrifying movie monster (my only problem with this is that Megalodon had a global distribution, so assigning it to one country feels a bit like cheating)

Monster of Aramberri: Speaking of giant sea monsters, here is a bit of a wild card. The “Monster of Aramberri“ are the remains of a giant pliosaur, possibly related to Kronosaurus. Even though it has been discovered in the 80s, the mysterious fossil still has not been formally described, but it is estimated to be among the biggest pliosaurs that ever lived (Art by Dmitri Bogdanov)

PS: I had a much harder time finding suggestions for Mexico than I did with the US and Canada. I‘m sure I missed some good ones. I also didn‘t include any dinosaurs because from what I could find most of them are either much better known from other countries, are disputed species or are very recent and don‘t feel “well known“ enough.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Most Amazing thing about Nature: the Arctic Tern

There are so many amazing things about nature, so it was very difficult to settle on just one topic. As a wildlife biologist, I know a lot of cool animal facts and characteristics. How does one pick between a venomous mammal and bullet-resistant armadillos? Or the various ways reptiles survive freezing temperatures, such as having antifreeze in their blood like painted turtles or drying out their organs and freezing 60% of their bodies like wood frogs?

There are so many fascinating behavioural and biological adaptations to sort through that I could travel to the ends of the earth and still not find the most amazing one.

“To the ends of the earth.”

Wait a second; that might just be it! The story of a tiny little bird who spends its life doing just that: the Arctic tern!

Image credits: Barni1 (2015).

The Arctic tern is a small seabird known for its incredibly long yearly migration that takes them, literally, to both ends of the earth. Each year, during this migration, they will travel over 40,000km, making theirs’ one of the longest migrations of any animal on earth (Ramroop & West, 2022).

Distribution range and migration routes of the Arctic Tern (nesting region in red):

Picture by Andreas Trepte (n.d.)

How do they do it? Arctic terns have unique adaptations that allow them to be incredible migrators. Their wing shape and lightweight bodies enable them to glide great distances carried by the ocean breeze without expelling much energy (Ramroop & West, 2022). Additionally, they can eat and even sleep while gliding in the air (Ramroop & West, 2022).

Image credits: Canadian-Nature-Visions (2022)

Now, you may wonder why this bird, which weighs slightly less than a quarter-pound burger, is willing to travel such miraculous distances each year (Trepte, n.d.). Well, much like the Beatles’ 5th track on their 1964 album, Beatles for Sale, they “… Follow the Sun.”

In doing so, these birds are constantly perusing summer. As you may know, the seasons are caused by Earth’s tilted axis as it revolves around the sun (Mika, n.d.). As a result, Earth’s northern and southern hemispheres are experiencing opposite seasons at any given time of year. During North American winters, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the sun, making it colder and darker in areas north of the equator. At the same time, the Southern Hemisphere is tilted towards the sun, making it warmer and brighter in areas south of the equator. The duration of daylight also changes depending on the season, especially in areas furthest from the equator (Mika, n.d.). During the summer, the Arctic and Antarctic get nearly 24hrs of sunlight. Conversely, in the winter, it is almost entirely dark. There are less noticeable temperature changes between the seasons in these areas than in other regions. Thus, the Arctic tern is not following the summer heat, as we may have envied. But instead, they are following the summer light (Ramroop & West, 2022).

Arctic terns rely on sunlight to illuminate the ground and ocean surface to see their prey (fish and insects) more clearly (Ramroop & West, 2022). By experiencing the ~24 hr-light of the Arctic and Antarctic summers, the Arctic Tern may experience more daylight than any other animal on earth (Ramroop & West, 2022). Their migration also allows them to take advantage of the good weather that accompanies summer, as it is beneficial to their method of flying. Terns rely so much on good weather and sunny conditions that they will fly thousands of miles out of their way to take advantage of the best weather and acquire the best food (Ramroop & West, 2022).

This post just scratches the surface of how amazing this tiny explorer is. The Arctic tern undoubtedly exemplifies one of nature's most impressive feats.

Google Earth tour of the Arctic tern’s migration:

youtube

Video credits: Encyclopedia of Life (2012).

References:

Barni1. (2015). Glacial lake birds to hunt fish [Image]. Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/photos/glacial-lake-birds-to-hunt-fish-889783/

Canadian-Nature-Visions. (2022). Arctic tern Sambro Island nesting. Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/photos/arctic-tern-sambro-island-nesting-6922063/

Encyclopedia of Life. (2012). Arctic tern migration Google Earth tour video [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bte7MCSBZvo&ab_channel=EncyclopediaofLife

Kaufman, K. (n.d.). Arctic tern: Sterna paradisaea. Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/arctic-tern#

Mika, A. (n.d.). The reason for the seasons. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/activity/the-reason-for-the-seasons/

Ramroop, T., & West, K. (2022). To the ends of the earth: Article on the annual migration of the arctic tern. National Geographic Society. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/ends-earth/

Trepte, A. (n.d.). Distribution range and migration routes of the arctic tern [Image]. Cool Antarctica. https://www.coolantarctica.com/Antarctica%20fact%20file/wildlife/Arctic_animals/arctic_tern.php#:~:text=arctic%20tern%20facts%20Basics,(26%20%2D%2030%20inches)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOOSE. Why are moose portrayed as these donkey-sized little things that are just bulkier, hairier deer, they're FAR more aggressive and dangerous than wolves, black bears, any snake within their range, probably cougars for the most part and definitely any other wildcat in their range... in European and North American forests, they're really only bested by grizzly and polar bears and probably bison in terms of danger to humans.

You see a moose, especially a bull or one with a calf, you get the fuck out of there before it sees you because it WILL become aggressive on sight, they're the size of a lanky teenage elephant, and they will pummel you into little red bits with their enormous hooves and potentially eat your corpse. These things will shrug off full-on highway collisions like a boulder getting an egg tossed at it, casually saunter off into the woods, and ragdoll once the adrenaline wears off. They're surviving ice age megafauna, a relic of the time when a lot of the mammals we know today such as armadilloes, cattle, goats, elephants, bears, cats and sloths had colossal, much hairier counterparts. Moose are to deer what musk oxen are to goats, mammoths were to elephants, and smilodons were to tigers.

Unless you have a particularly powerful gun and are good at using it, a moose will FUCK YOU UP. If you ever have to choose between standing in a field with an Alaskan bull moose or a pack of 2 dozen wolves, pick the wolves. The wolves will likely avoid you or just try to scare you off, the moose will be wearing your intestines as a necklace within 15 minutes tops.

I know it's unfair vilification and stuff but it's also a lot of fun to see old media and stuff where people were SO scared of big animals like lions, sharks, crocodiles and wolves were fully expected to just come and eat you the moment you stepped into their territory. In older media we also made that assumption about gorillas and in still older we thought it'd be whales. But some animals that will actually fuck you up got left behind. Boars will kill you and eat you. They're way more likely to do so than any of those other things actually. Hippos, obviously, got off like bandits always being depicted as cute and dopey. And then there's the squids. Not giant kraken size squids. The eight foot squids that hunt in packs and will fuck you up if you fall in the water at night. I can't BELIEVE people slept on that. It's like all they cared about were the huge deep sea ones we never see. The medium size wolf pack squids were right there.

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

Titanis: North America's Ancient Terror Bird

Meet Titanis, a colossal terror bird that once roamed North America during the Pliocene and earliest Pleistocene epochs. Named after the Greek Titans, this formidable predator was a member of the extinct phorusrhacid family, also known as “terror birds.” 🌍

A Colossal Presence

Discovered by amateur archaeologists Benjamin Waller and Robert Allen in Florida’s Santa Fe River and named Titanis walleri in 1963 by ornithologist Pierce Brodkorb, Titanis was among the largest of its kind. The fossils found include only a fragmentary right tarsometatarsus (a lower leg bone) and a phalanx (a toe bone), but they hint at an impressive size. 🌿🦴

With a height estimated between 1.4 to 2 meters (4.6 to 6.6 ft) and a body mass over 300 kilograms (660 lb), Titanis was a towering figure in its ecosystem. Though its anatomy is partially known due to fragmentary fossils, its skull was estimated to be between 36 cm (14 in) and 56 cm (22 in) long, making it one of the largest known bird skulls.

Terror Bird Traits

Like its phorusrhacid relatives, Titanis had long, powerful hind limbs, a lightweight pelvis, and a large skull with a hooked beak. It was likely an apex predator or scavenger, dominating its environment just as phorusrhacids had in South America before the Great American Interchange. 🏞️🔍

Titanis stood out for its slender, elongated tarsometatarsus, similar to the agile Kelenken. This suggests it might have been swift and capable of high-speed pursuits. Research on related species indicates that these birds had very robust skulls, enabling them to handle high-stress feeding behaviors, possibly swallowing small prey whole or delivering repeated strikes to larger prey.

An Ancient Apex Predator

During its time, Titanis shared its habitat with a diverse range of megafauna in North America, including giant armadillos like Holmesina and Glyptotherium, as well as equids, tapirs, and capybaras. Its impressive size and predatory skills made it a significant predator in the Pliocene savannas. 🌾🦓

What makes Titanis particularly fascinating is that it’s the only phorusrhacid known from North America, having crossed over from South America during the Great American Interchange. Its presence in North America adds a remarkable chapter to the story of prehistoric predators and their adaptations to new environments.

0 notes

Text

i love america. not the country specifically, i mean the continent of north america. i love the place i live in so much. seeing the native species makes me so happy. it’s so terrible that we have such complex issues trampling all our nice things, it’s terrible that the south is known for being bigoted when we’re one of the most vulnerable places in the country. specifically the north american southeast is so gorgeous to me, i’ve been living here so long. we have SO many plants you could never even dream up.

we have giant leopard moths, giant wasps, silly weevils, junebugs, MOLE CRICKETS?? magical-looking creatures you would never think would be under a rock in the middle of nowhere in a red state. we have an abundance of raccoons to where they’re considered pests, but they’re the second-closest thing to a red panda. we have ARMADILLOS! i don’t understand how anyone gets bored of living here, i don’t ever want to permanently abandon it. the way things are going, it seems like it’s not the place for me.. but it’s my place. the government obviously hasn’t considered that this is MY place, and i won’t be going anywhere 💀 all of my favorite plants are here. we have red-winged blackbirds and brown-headed cowbirds. literally why would i leave. we have wild irises and trout lilies. spiderwort?? oh my god. all the violets. all of them

#i can’t say as much about canada since i’ve never been but every ecosystem is complex#im sure i’d love being immersed in the canadian wildlife too#american biodiversity is so personal to me#and im sure latin america is kind of similar to this but on steroids#latin american biodiversity is like wonderland compared to north america but north america is my bae#nationalism#patriotism#i love my home#america#speaking

1 note

·

View note