#Nearly two-thirds of all reported abortions in 2023

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Vance said the following at the anti-abortion March for Life in January: “I want more babies in the United States of America. I want more happy children in our country, and I want beautiful young men and women who are eager to welcome them into the world and eager to raise them.”

Is Vance willing to help the economy so young people can be eager to start a family? Or is he going to be OK with. Or more money being spent of foster care because the potential adoptive parents from even 10 years ago are now sinking their hopes (and money) into IVF and surrogacy to have biological offspring

By Susan Rinkunas | March 4, 2025 |

It’s no secret that conservatives want to ban abortion pills or make them so much harder to obtain that they’re effectively banned. It’s also no secret that a number of freaks currently running our country are obsessed with everyone popping out babies. What we don’t know at this point is which tactics they’ll use to push their anti-abortion, pro-natalist agenda or how they’ll rationalize further limits on abortion access.

One tool Republicans could use would be misapplying the 19th-century Comstock Act to prevent sending the medications mifepristone and misoprostol in the mail. (Nearly two-thirds of all reported abortions in 2023 were done with abortion pills.) In a January letter, activists urged the Department of Justice to begin enforcing the zombie anti-obscenity law that bans sending abortion drugs or devices in the mail. (The Biden administration said the dusty old law shouldn’t be applied to legal abortions, but they’re not in office anymore.) In February, Attorney General Pam Bondi raised alarm bells when she told a Louisiana prosecutor she “would love to work with [him]” on a criminal case against a New York doctor who allegedly mailed abortion pills to a woman and her teen daughter. Bondi could be signaling that she’s open to prosecuting the physician under Comstock, but we have to wait to find out.

This week, one anti-abortion activist implored Bondi to enforce Comstock and gave two rationalizations: One, it could possibly bankrupt abortion providers and, two, it could maybe help with the country’s declining birth rate.

Rev. Jim Harden, the CEO of a crisis pregnancy center chain called CompassCare, said in a Monday interview with an apparent right-wing outlet called Just the News that Planned Parenthood is the single largest provider of abortions and gets millions of dollars from the government from programs like Medicaid. “It’s the biggest abortion business, probably on the planet,” Harden said. “If they shut down, it’s going to be good for women. There’s so many fantastic pro-life pregnancy centers.”

Harden then not-so-subtly hinted that Bondi could achieve the GOP goal of “defunding” Planned Parenthood by hitting them with Comstock prosecutions for actions that occurred even before Trump took office a second time.

“If Pam Bondi decides that she wants to enforce the Comstock Act, which basically says it’s illegal to ship chemical abortion drugs across state lines—and by the way, that’s 60% of all abortions in America right now is chemical abortion—the Comstock Act would essentially bankrupt the abortion industry in a very short period of time, because one violation is [up to] a $250,000 fine with a five-year statute of limitations, plus racketing charges,” he said.

But it got worse. He then claimed that abortion was “decimating minority communities” and that conservatives needed to focus more on women and children, specifically, making the former produce more of the latter. “Our country is facing a baby shortage,” Harden said. “We have a fertility problem in this country, not because women can’t have babies but because abortion is decimating the population.”

This sounds like a dog whistle tuned precisely for the pro-natalist creep ears of shadow president Elon Musk and Vice President JD Vance. Musk has 14 children that we know of, and Vance said the following at the anti-abortion March for Life in January: “I want more babies in the United States of America. I want more happy children in our country, and I want beautiful young men and women who are eager to welcome them into the world and eager to raise them.”

Few people make this birthrate argument against abortion pills, but the ones that do sound extremely weird. The Attorneys General of Kansas, Idaho, and Missouri claim in a lawsuit against the Food and Drug Administration that easier access to medication abortion is lowering teen birth rates in their states, which could reduce their population and lead to losing seats in Congress and federal funds. (In June, the Supreme Court said the original plaintiffs in this case weren’t harmed by the FDA’s actions and thereby didn’t have legal standing to sue, but the state AGs marched into a notorious anti-abortion judge’s courtroom and he said they can continue the litigation.)

Abortion is not the reason the birthrate is falling. That would be unchecked capitalism where working people don’t make enough money to feed and clothe children, let alone afford housing big enough for families, and aren’t guaranteed paid leave to recover from birth. Plus, the proliferation of abortion bans has led to more people choosing permanent sterilization rather than risk being forced to carry pregnancies that could kill or disable them and then parent children they don’t want. Food for thought, Pam!

#reproductive rights#Comstock act#misoprostol#mifepristone#Nearly two-thirds of all reported abortions in 2023#Attorney General Pam Bondi#Rev. Jim Harden#CompassCare#crisis pregnancy center play with the lives of vulnerable women#Planned Parenthood#Medicad#because one violation is [up to] a $250#000 fine with a five-year statute of limitations#plus racketing charges

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the December 21, 2023 item:

One in five in Gen Z and millennials (ages 18-41) say that dictatorship could be good in certain circumstances. ... A new Siena College poll shows that the war in the Middle East is having a real toll on Biden's popularity. Among young voters, Trump leads Biden 49% to 43%. ... The Biden campaign understands this and is trying to make it more concrete to younger voters by framing the issue as authoritarians trying to take away their rights, for example, the right to an abortion and the right to be safe from gun violence. ... One 23-year-old man in Wisconsin said: "I genuinely could not live with myself if I voted for someone who's made the decisions that Biden has." The reporter did not ask him what he expected a president Trump to do about the Middle East. ... These people are viewing the election as an up-or-down vote of approval for Biden and the Democrats, rather than a choice between two alternatives. Older voters better understand the concept of picking the lesser of two evils rather than voting as a way to make a statement. Biden really needs to frame the election as a choice between two candidates, not a vote to approve/disapprove how he is doing his job. ... In reality, of course, no president could have codified Roe v. Wade. Only Congress can do that and there wasn't even a majority among Democrats for that, let alone the entire Congress. But the young voter doesn't know that and he is going to punish Biden for it by voting for a third-party candidate. ... Not all young voters follow the news enough to know that Biden did try and another branch of government said: "Nope." Biden has canceled student debt for a limited number of people, but not nearly as many as he promised. Again, young voters, especially those who don't follow the news, don't distinguish between politicians who promise something, actually try to do it, and get swatted down by one of the other branches and politicians who never even try to make good on their promises.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

This GOP strategy was a crime.

February 20, 2023

One of the reasons Republicans fared so poorly in last November's elections was that GOPer candidates premised much of their closing arguments on being the party that could tackle crime and keep people safe. Especially when contrasted with the supposedly crime-infested "Democrat-run" big cities.

Conservatives had plenty of reason to think this was a winning tactic. According to numbers released by the CDC, the murder rate in the US exploded in 2020, up 30% from 2019 — the largest single increase in 100 years. And in an October 2022 CBS News poll, crime ranked third, behind the economy and inflation, when it came to "very important issues" worrying voters. Finally, a pre-election Faux News poll reported Republicans holding a 15-point advantage over Democrats on handling crime.

And so it was that Republican candidates around the country — from Adam Laxalt in Nevada to Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania — attacked their Democratic opponents' eagerness to defund the police and inability to combat the imagined crime wave threatening America. In September 2022 alone, GOP campaigns and committees spent $39.8 million on ads focused on crime, with an additional $64.5 million in the first three weeks of October, according to ad tracker AdImpact.

CNN's perennially wrong Chris Cillizza pronounced this strategy "devastating for Democrats."

With less than two weeks left before the midterm elections, momentum is clearly with Republicans in the race for both the House and Senate. And that’s in large part due to a big bet the party made that crime would be a central issue for the public this fall.

Yet many of these crime-busting pols went down to defeat. Why? It's not complicated. Sure, crime was an important issue to voters. But wrapped in their cocoon of ignorance, Republicans failed to realize that abortion rights and dislike of clownish, Donald Trump-endorsed candidates ranked much higher.

Then there was the fact that crime, even in our sin-soaked cities, was not nearly as bad as right-wing hysterics portrayed it. For example, the homicide rate was considerably higher in the 1970s, '80s and '90s. And while crime in 2022 increased somewhat across all states, the largest increases were to be found in rural, Republican-controlled states like South Dakota (+81%) and Kentucky (+61%).

In New York's race for governor, Long Island congressman Lee Zeldin too campaigned on the crime issue. Just weeks before the election, he declared, "There is a crime emergency right now in New York State." Regrettably, like many others last November, he thought a make-believe crime wave would turn into an actual red one.

0 notes

Text

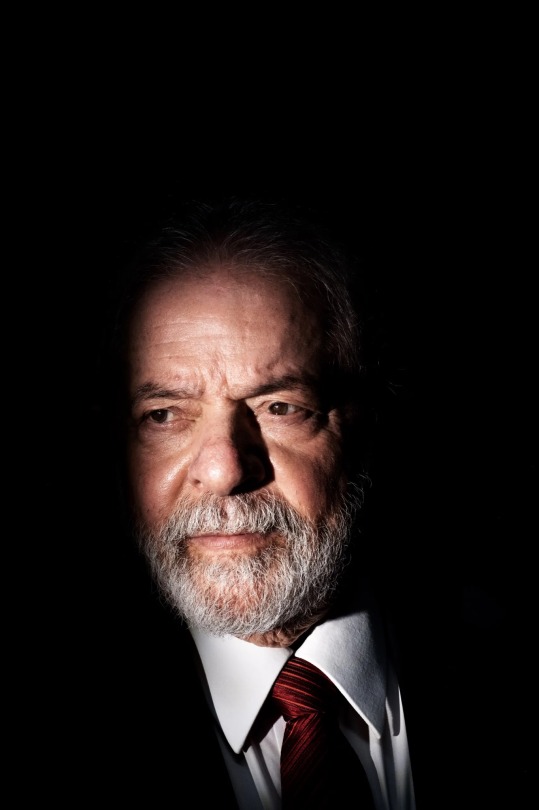

Governing after four years of divisive rule will be a profound challenge. “The Weight on My Back is Greater,” Lula said. Photograph by Tommaso Protti

A Reporter at Large: After Bolsonaro, Can Lula Remake Brazil?

Following a prison term, a fraught election, and a near-coup, the third-time President takes charge of a fractured country.

— By Jon Lee Anderson | January 23, 2023 | January 30, 2023 Issue

All around the immense city of São Paulo, posters on telephone poles display a Pop-art image of the newly elected President of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—Lula, as he is universally known. His head is crowned by dark curls, his face adorned with a red star, a symbol of his Workers’ Party. It is a vision of Lula in his early days: the left-wing idealist, the charismatic strike leader, the prophet of an imaginary future in which Brazil would become a center of social justice where no one went hungry, the rain forest was protected, and the enmity between races and classes dissolved. It is an old cliché that Brazil is the country of the future—a future that will never arrive. It is also true that the colossus of Latin America has not fulfilled many of its people’s hopes.

For generations of Brazilians, Lula is the country’s most familiar public figure. He served two previous terms as President, from 2003 to 2010. In 2018, he was imprisoned on charges of money laundering and corruption. Lula denied any wrongdoing, insisting that he was the victim of a political revenge scheme. His candidacy represented an almost unprecedented comeback.

After a long career of constant crisis, of triumph and embattlement, Lula looks his age. He is seventy-seven, short and sturdy, with a rooster’s erect posture and puffed-out chest. His hands are tough, like a boxer’s, but his skin is pale, and his curly hair has gone thin and white. When I saw him last November, a few days after he won the Presidential election, he entered the living room of a hotel suite in São Paulo surrounded by a phalanx of aides and security guards. He was dressed in a politician’s gray suit jacket and slacks, which he seemed to wish he could trade for his customary guayabera and jeans.

Lula looked not just exhausted but also unwell. In 2011, barely a year after he broke a half-century smoking habit, he had received a diagnosis of throat cancer and undergone chemotherapy. Doctors urged him to take special care of his throat, but of course he had ignored them during the campaign, and often when he spoke now his voice was reduced to a gravelly, theatrical growl. During his victory announcement, he seemed to strain to produce an impassioned whisper.

Lula’s campaign speeches suggested that he was engaged in an existential conflict. His opponent was Jair Bolsonaro, the incumbent, a right-wing populist who had become known as “the Trump of the tropics,” and as one of the hemisphere’s most controversial leaders. Like Trump, he had come to power by appealing to voters who were outraged by abortion rights, gay marriage, and sex education in primary schools. Throughout his career, his rhetoric was often hateful. He once dismissed a female legislator by saying that she was “not worth raping, she is very ugly.” On the subject of homosexuality, he said, “If your child starts to become like that, a little gay, you beat him and change his behavior.” In office, he allowed corporations to hack away at the rain forest virtually unimpeded, and police to shoot suspects without restraint. Responding to the covid-19 pandemic, he was neglectful and often cruel, telling his citizens, “Everyone has to die one day. We have to stop being a country of sissies.” Brazil has had nearly seven hundred thousand reported deaths, second only to the United States.

Lula, in his campaign, had talked in almost messianic terms about his desire to “rescue” Brazil. He had also begun to speak about God, his age, how he felt lucky to have endured his adversities. On the night he finally won, he said, “They tried to bury me alive, but I survived. Here I am.”

When I’d last seen Lula, in December, 2019, he had appeared vigorous and relatively youthful. Now, despite his campaign rhetoric, he seemed a little overwhelmed by the prospects he faced in his mission to save Brazil. Sinking into a chair and exhaling heavily, he said that he’d been on the telephone all morning with world leaders who’d called to congratulate him. When I asked what political initiatives he had planned, he spoke almost by rote, as if still on the campaign trail. But when I said that, outside Brazil, many people expected him to rescue not just his country but the global environment, by reversing the deforestation of the Amazon, his eyes widened almost fearfully, and he exclaimed, “Yes, I know!” Reaching over to grab my knee, he leaned in and began speaking intently of reshaping the country. “People are very optimistic about our governance,” he said. “People are expecting something to change, and it will change.” This was the Lula from the Pop-art poster, the leftist crusader who had enthralled Brazilians since his first appearance on the national stage, forty years earlier. But now the country around him was different, divided sharply between those who loved him and those who despised him.

On New Year’s Day, Lula was inaugurated in the capital, Brasília, a sprawling city carved from the forest in the late nineteen-fifties. In a speech from the Planalto Palace, a modernist building that contains the Presidential offices, he made an attempt at conciliation. “There are not two Brazils,” he said. “It is of no interest to anyone to live in a family where discord reigns. It is time to bring families back together, to remake the ties broken by the criminal spread of hate.”

A week later, Bolsonaro supporters swarmed the capital, arriving on more than a hundred buses from around the country to overturn what they insisted was a stolen election. Shouting, “Overthrow the thieves!” and “We will die for Brazil!,” they invaded the Presidential offices, the Supreme Court, and the legislature, setting fires and smashing whatever they found.

At Lula’s order, Brazilian authorities moved swiftly to turn back the siege, arresting more than fifteen hundred protesters and promising an inquiry into the origins of the violence. Lula also orchestrated a display of unity: dozens of government leaders, including some loyal to Bolsonaro, walked arm in arm across the vast plaza that connects the Planalto Palace with the Supreme Court. It was an effective gesture—a reminder of the street protests that had helped establish his reputation decades before. But Lula seems conscious that making the country function after four years of authoritarian rule will be a profoundly larger challenge. “My responsibility is much greater now,” he told me. “The weight on my back is greater.”

Last October 1st, the day before voting began in the Presidential election, Lula stood in the back of a pickup truck as it rolled along Rua Augusta, a narrow street in São Paulo known for its bars, sex shops, and raucous night life. Crowds had gathered along the sidewalks and on apartment balconies, and more clogged the street around his truck. Brazilian elections have two rounds, but any candidate who wins a simple majority in the first round can clinch the Presidency. Lula, who is at his best in a throng of supporters, was hoping to inspire voters to put him in office without delay.

Electoral rules forbid candidates to speak to voters on the last day of the campaign, so Lula waved silently and blew kisses. The crowd was noisy, though: music was pounding from speakers on his vehicle, and people in the streets were dancing. Suddenly, Lula began jumping around the truck, like a kid in a mosh pit. At his encouragement, his campaign ally Fernando Haddad, two decades his junior and a head taller, began jumping, too. As they bounced, more or less in time to the music, onlookers cheered them on. Video of the spectacle soon spread on social media.

It was a moment of buoyancy in a contentious campaign, one that had divided voters over questions about what kind of a country Brazil is and what kind it should be. Lula’s followers tended to be younger, more multiracial, and lower-income, with a considerable L.G.B.T.Q. contingent; Bolsonaro’s skewed older, whiter, and wealthier. As Lula’s rowdy cavalcade made its way down Rua Augusta, a Bolsonaro procession traversed a nearby avenue, accompanied by squads of hard-faced men on motorcycles.

Most polls suggested that Lula would win by a comfortable margin. But it was uncertain whether Bolsonaro would honor the results of the election if he lost. Like Donald Trump, with whom he had established a close rapport, Bolsonaro had long questioned the security of Brazil’s electronic voting machines—even though they had affirmed his victory in the previous election. In 2021, he told a group of loyalists that he saw only three possible scenarios for himself in the election: victory, arrest, or death. He appeared to be prepping his supporters, the bolsonaristas, to reject any result that favored Lula. He had also hinted repeatedly that the armed forces, where he had a great deal of support, would back him in a contested election. His minister of security, a hard-line former general, made threatening remarks about the possibility of military intervention.

In the United States, Trump’s allies helped amplify Bolsonaro’s arguments. On Fox News, Tucker Carlson warned that Lula would be a puppet of the Chinese President, Xi Jinping. “Allowing Brazil to be a colony of China would be a significant blow to us and potentially a very serious military threat,” he said. “The Biden Administration appears to be in favor of it. One person who is emphatically not in favor of it is the President of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro.” (Days before, Carlson had conducted a fawning interview with Bolsonaro, suggesting that he was a better leader than the Ukrainian President, Volodymyr Zelensky, and posing with him for pictures afterward wearing an Indigenous feather headdress.) The former Trump official Steve Bannon stoked fears that Lula intended to cheat his way to power: “Bolsonaro will win unless it’s stolen by, guess what, the machines.”

With concerns growing, the Biden Administration quietly deployed visiting emissaries, including Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, to warn Bolsonaro, his senior officials, and the military not to interfere in the election. As a U.S. official familiar with the outreach told me, “We made a concerted policy to let them know where the lines were for us. The outcome of the election was their business, but what we cared about was that the process be respected. We think they listened.”

Brazil’s Supreme Electoral Court also joined the effort. Its head justice, Alexandre de Moraes, moved quickly to engage the armed forces, inviting them to participate in an election-transparency commission. To defuse Bolsonaro’s claims, he also arranged for the military to inspect a number of voting machines on Election Day. The proposal drew criticism from advocates of electoral independence, but the armed forces agreed. Whatever else might happen, it seemed, they were unlikely to launch a coup.

The concerns about the stability of the government were not frivolous. Democracy has tenuous roots in Brazil. From 1964 to 1985, the country was ruled by a military dictatorship, whose officers harshly oppressed labor unionists, clergy, academics, and the country’s tiny contingent of Marxist guerrillas. Nearly five hundred people were killed, and thousands were imprisoned and tortured—including Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s successor as President, who was captured when, as a young woman, she was an urban guerrilla.

Some of Brazil’s neighbors suffered far worse. In Argentina, between nine thousand and thirty thousand people were tortured, murdered, and “disappeared” by the military. But, while Argentina reckoned with the regime’s atrocities in a series of trials, Brazil left its military untouched, passing a law in 1979 to provide amnesty for abuses. As an institution, it has expressed no remorse.

The relatively unexamined legacy of Brazil’s dictatorship, in which the hard-right military attacked both leftist protesters and democrats, still informs the country’s politics. Bolsonaro, a former Army captain, was an eager participant in the dictatorship, and during a twenty-seven-year stint in parliament often called for a return to military rule. In one famous outburst, he said that the military had not gone far enough—that, if only it had killed thirty thousand more people, Brazil’s problems with leftists would have been solved. In 2016, when Brazil’s Congress impeached Rousseff, Bolsonaro cast his vote in the name of a notorious military colonel who had commanded the unit that tortured her.

Lula, on the other hand, is Brazil’s archetypal leftist. He was born poor, the sixth of seven children. His parents worked as farmers in famine-stricken Pernambuco, a state in the northeastern part of the country. When Lula was a young child, his father set off for São Paulo, in pursuit of a more stable livelihood, and found work as a day laborer. By the time the rest of the family could join him, when Lula was seven, he had found another woman and started a new family. For four years, they all lived together until Lula’s mother could find another place—a cramped room behind a bar.

Lula did not learn to read until he was about nine, and he quit school soon afterward. He worked as a street vender, a shoeshine boy, a warehouse laborer, and, eventually, a machine operator in a screw factory. At nineteen, he damaged the little finger on his left hand in an accident with a mechanical press. He couldn’t get medical treatment until the next day. To his dismay, the doctor performed a full amputation. In time, his opponents came to deride him as Nine-Finger.

He soon got involved in trade-union politics, organizing protests outside factories and displaying a gift for oratory. He was imprisoned for leading an illegal strike but emerged after a month, and by the waning years of the dictatorship had become a prominent labor leader in São Paulo. In 1980, as the armed forces prepared to relinquish power, he founded the left-wing Partido dos Trabalhadores, the Workers’ Party, known as the P.T. He soon began running for political office, and, over the years, whether winning elections or losing them, he has become the undisputed leader of the Brazilian left. “There’s no one else of his stature in the hemisphere,” a Western official who has met with him several times said. “He’s the boss.”

As the returns came in for the first round of voting, Lula’s campaign team gathered in a São Paulo hotel. In a briefing room, scores of journalists, hangers-on, and politicians crowded around a huge television screen, watching as the tally tipped toward one candidate, then the other. The sound in the room tracked the results: agitated silence when Lula was trailing, laughter and cries of “Lula-la!,” a refrain from an old campaign song, when he took the lead.

By early morning, Lula had 48.4 per cent of the votes—five points ahead of Bolsonaro, but short of what he needed to win the Presidency in the first round. Moreover, Bolsonaro had attracted many more voters than pollsters had predicted. Lula’s team was realizing not only that a second round was going to be necessary but that, even if their candidate won, Brazil had become a vastly different country from the one he had presided over twelve years earlier.

Lula left office in 2010 with a historic eighty-eight-per-cent approval rating. The economy had boomed during his tenure, thanks in large measure to surging commodities prices, a significant oil discovery off the coast, and the explosive growth of China, a major buyer of Brazilian exports. In 2010, the rate of economic growth was 7.5 per cent, the highest in decades. Brazil belonged to a group of fast-growing nations known as the brics—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. But, since then, the economy has slumped, and Brazil, once the world’s fifth-largest economy, is now its ninth.

Bolsonaro worked to make Brazil friendlier to business, but many of his supporters were more energized by his prosecution of a culture war. He had won the Presidency in 2018 with the backing of the powerful consortium known as the three B’s: beef, Bibles, and bullets, signifying agribusiness, the evangelical church, and the arms lobby. In public appearances, his characteristic gesture was shooting make-believe pistols. He enjoyed widespread support among law-enforcement groups, especially the military police, which have a reputation for indiscriminate force and for involvement in organized crime.

In office, he expanded police departments and gave them wide leeway in dealing with criminals. In 2020 and 2021, police in Brazil killed more than six thousand people a year—six times the total in the United States. Bolsonaro also loosened gun laws, arguing that citizens needed to defend themselves against criminals and left-wing land invaders. Registered gun ownership grew sixfold while he was in office; gun shops and shooting ranges flourished.

It is illegal in Brazil to make racist remarks, but Bolsonaro regularly found ways to insult his country’s nonwhite inhabitants, saying that members of Afro-Brazilian communities were “not even good enough to breed” and that the Indigenous were “increasingly becoming human beings just like us.” Refugees were “the scum of the earth.” Violence against these communities, and against L.G.B.T.Q. people, surged during his tenure.

Soon after Lula took office, Bolsonaro supporters stormed the federal district of Brasília, calling for military intervention. Photograph by Antonio Cascio / Reuters / Redux

As Bolsonaro’s popularity grew, Brazilian politicians on the right began proclaiming their adherence to bolsonarismo. In the recent elections, candidates sympathetic to his ideas had done unexpectedly well, taking a majority of Senate and gubernatorial seats. One of those who won legislative posts was Eduardo Pazuello, an Army general who for a time ran Bolsonaro’s calamitous response to the pandemic. Another was Ricardo Salles, Bolsonaro’s first environment minister, who left office while under investigation for conspiring to traffic Amazonian hardwoods. (He denies the allegations.)

In São Paulo state, Brazil’s largest electoral constituency, the returns were mixed. The capital swung to Lula. Smaller cities and the countryside went to Bolsonaro, as they had in many other places where ranching and agribusiness drive the economy. In the campaign press room, Lula professed confidence: “We’ll have to fight on, but we’ll win.” His protégé Guilherme Boulos put it more starkly. Running against Bolsonaro, he said, was “a war between democracy and barbarism.”

Lula began running for President as soon as he was able. He launched his first campaign in 1989, just a year after a new constitution, adopted as Brazil returned to democracy, made it legal for leftist parties to run for office. He lost narrowly to Fernando Collor de Mello, a sharply dressed young proponent of free-market ideas. Collor de Mello resigned two years later, brought down by a corruption scandal. (He was later acquitted.)

Lula ran again in 1994 and 1998, and lost both times to Fernando Henrique Cardoso, a left-wing scholar who had once marched alongside him in street protests. As President, Cardoso moved toward the center, supporting the privatization of several major government-owned corporations. Lula remained a committed leftist, assailing the “neoliberal” reforms that swept the region, with American encouragement. While Cardoso became friendly with Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, Lula was more philosophically aligned with Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez.

But when Lula finally won the Presidency, in 2002, he showed a surprising pragmatism, along with a political survivor’s wiliness. He weathered a scandal involving a scheme to buy legislators’ votes, which became known as mensalão, or “the big monthly payment.” Though several of his closest deputies were implicated, he was not charged. In the same years, he launched a cash-transfer program, known as Bolsa Família, that lifted some thirty million Brazilians out of extreme poverty, and initiated an ambitious program to bring electricity to neglected areas of the countryside. During his tenure, the illegal destruction of the Amazon rain forest decreased dramatically, as he implemented programs to police the region and designated several million acres as conservation areas and as reserves for the Indigenous.

Lula’s personal warmth is probably his greatest political asset, and, unlike other Latin American leftists of his generation, he showed an exceptional ability to work both sides of the political aisle. Despite his opposition to the Iraq War, he cultivated a genial relationship with George W. Bush. When Barack Obama shook hands with Lula for the first time, at a G-20 summit in 2009, he told officials there, “I love this guy. He’s the most popular politician on Earth.” (In fact, the two didn’t get along that well; Lula told me that he had a better rapport with Bush, who, notwithstanding their differences, was a guy you could have a barbecue with. Obama, for his part, wrote in his memoirs that Lula was “impressive” but “reportedly had the scruples of a Tammany Hall boss.”)

At times in last year’s campaign, though, Lula seemed to have lost his easy dexterity. At a television studio in Rio, I watched him take part in the last of three Presidential debates. Bolsonaro’s insistent theme was that if Lula won back the Presidency Brazil would become like Venezuela—a byword for failed left-wing politics. Bolsonaro strutted grimly around the studio, calling his opponent “a thief, a traitor to the fatherland, and an ex-prisoner.” Lula sputtered outraged denials and shouted back that Bolsonaro was “shameless, repulsive,” and unfit to hold the Presidency. Few of Lula’s loyalists were happy about his performance. While Bolsonaro was characteristically vulgar, Lula had reacted badly to his attacks, and failed to express any new ideas or policy initiatives.

Bolsonaro’s accusations—he called Lula a “national embarrassment”—are complicated by the fact that corruption has been endemic in Brazil for much of its modern history. The government owns large sectors of the economy, and many legislators expect to be compensated for their coöperation. “Parliament is either subservient or rebellious,” José Eduardo Cardozo, a lawyer and a prominent Brazilian politician, told me. “And, when it is subservient, it is because it participates in the government—it has the money. If it’s not participating, it wants the government out.”

Lula, in his two terms, managed to cultivate the legislature while avoiding the consequences of the mensalão vote-buying scandal. His successor, Dilma Rousseff, lacked his nimbleness. “She was not a woman who liked to talk to parliamentarians,” Cardozo, who also served as Rousseff’s minister of justice, told me. “She was a cadre who thinks about politics, but who does not perform politics.”

Rousseff was Brazil’s first female President, and a formidable figure. After her early stint as a Marxist guerrilla, she had spent three years in prison, before going on to serve as Lula’s minister of energy and his chief of staff. When she became President, though, the economy was beginning to stagnate, and in her second term a crash in commodities prices meant that Brazil had less money coming in. Street protests became commonplace. So did maneuvering by her political opponents to unseat her. Even her Vice-President, Michel Temer, supported calls for her impeachment, ostensibly for manipulating the country’s budget.

One irony of those years is that Lula and Rousseff strengthened the judiciary, which made corruption more visible in their own government. Under Rousseff, the federal police began a series of investigations known as Lava Jato, or Car Wash. For several years, a team led by a judge named Sergio Moro operated out of Curitiba, in the conservative south of Brazil. It investigated corruption across Latin America, bringing down powerful C.E.O.s, government officials, and even several foreign Presidents for their involvement in money laundering and bribery.

Many of the schemes were linked to Brazil’s state oil firm, Petrobras, and to the construction giant Odebrecht, both of which had thrived during Lula’s tenure. Moro accused Lula of being the mastermind of an international conspiracy, and a years-long investigation began. In the end, the charges were narrow: Moro alleged that Lula was illicitly promised a beachside apartment, and that friends had effectively bought a ranch for his use, where Odebrecht made renovations at the request of Lula’s wife.

In a dramatic televised hearing, Moro coolly interrogated Lula, who angrily denied the charges and demanded proof of the allegations against him. Lula’s supporters have persistently argued that there is little evidence tying him to the properties. But, not long after the hearings, Moro released recordings that his agents had made of phone conversations between Rousseff and Lula, in which she said that she was sending him papers that would secure him a ministerial post. Rousseff said that the post was routine; Moro claimed that she was trying to protect Lula from arrest. A few months later, the legislature forced Rousseff out, and Temer took her place.

Political corruption did not diminish in Brazil. Eduardo Cunha, who had led the congressional campaign against Rousseff, was found guilty of accepting forty million dollars in bribes. Temer himself was implicated, but the same Congress that had voted to impeach Rousseff opted to leave him in office, for the sake of what the presiding judge called the “stability of the electoral system.”

As the 2018 Presidential election approached, Lula remained the most popular politician in the country, with what one poll said was a fifteen-point lead over his closest competitor. But he was increasingly embroiled in criminal investigations. A few months before the voting, police burst into Lula’s house to search for evidence; Marisa Letícia Casa, his wife of four decades, died of a stroke shortly afterward. Lula was convicted of corruption, sentenced to thirteen years in prison, and placed in a federal-police facility in Curitiba.

A contingent of supporters camped outside the fence near Lula’s cell, greeting him every morning with calls of “Good day, Lula.” But Moro’s investigation insured that he was barred from public office, instantly making Jair Bolsonaro the Presidential front-runner. In the election, Bolsonaro secured a narrow victory over Lula’s stand-in, the former São Paulo mayor Fernando Haddad. Soon after being elected, he made Moro his minister of justice.

Among the loyalists who visited Lula in prison was his friend Emidio de Souza—a genial, burly man in his early sixties, who has served for years as a state legislator for the P.T. When Lula was arrested, it was de Souza who negotiated his surrender, persuading the police to abide by two conditions: “no haircut, no handcuffs.” He also arranged for Lula to be picked up discreetly, out of sight of a television crew circling in a helicopter nearby, in the hope of avoiding public humiliation.

Still, the arrest affected Lula profoundly. “He expected to be in prison for a week, maybe, or ten days,” de Souza told me in São Paulo. “But his extended imprisonment showed him that the world was going to move against him.” He passed the time by working through an earnest undergrad’s reading list: a history of slavery in Brazil, a treatise on how oil has led to wars, a biography of Nelson Mandela. He continued to follow party politics, de Souza said: “He wasn’t allowed the Internet, but he received daily written reports, news clippings, sometimes analyses of the political situation in the country. He also recorded the P.T. meetings on a flash drive, and then watched them on TV.”

From prison, Lula looked on as Bolsonaro began to generate his own corruption scandals. Though he had campaigned as a reformer, he and his family members were accused of a series of offenses, all of which they deny. Prosecutors allege that two of his sons embezzled public funds, and that an aide involved in one of the schemes funnelled money into an account owned by Bolsonaro’s wife. The family was eventually found to have bought at least fifty-one properties, largely in cash. (Bolsonaro gave a bluff response: “What’s wrong with buying houses in cash?”) To cultivate political allies, Bolsonaro’s administration maintained a “secret budget,” which gave the legislature access to some three billion dollars—a fifth of all discretionary spending—which could be apportioned without oversight.

In June, 2019, the Intercept published leaks of phone messages between Moro and the prosecutors who had tried Lula, which revealed significant ethical lapses. Moro illicitly discussed tactics with the prosecutors; the lead prosecutor expressed doubts that Lula had actually owned the apartment at the center of the case. In other leaks, the Lava Jato investigators admitted that they hoped to bring down Lula and the P.T. The United Nations Human Rights Council subsequently found that the investigation had violated due process.

In November, 2019, Lula was released, after five hundred and eighty days in prison. De Souza told me that Lula insisted he could rebuild his image, saying, “I’m not going to go down in history as a guy who stole.” In his first speech after being released, he called himself “the victim of the greatest legal lie ever told in five hundred years of history.”

I saw Lula a few weeks later, in a hotel overlooking Rio’s Copacabana beach. He was seventy-four—one year shy of the age at which the Catholic Church would no longer allow him to be a bishop, he joked. He said he’d been working out and felt fitter than he had in years. He had also fallen in love, with Rosângela (Janja) da Silva, a sociologist and a Workers’ Party member twenty-one years his junior; her daily letters had sustained him in prison, he said. He was still legally barred from politics, but he made it clear that he would return as soon as his prohibition was lifted. “If I were a candidate in 2022, I would surely win,” he said. “Because there is a faithful relationship between the Brazilian people and me.”

When Lula won the second round of voting, on October 30th, the crowds in São Paulo were ecstatic. From a two-story soundstage above Avenida Paulista, the city’s main thoroughfare, Lula waved and blew kisses, as his supporters danced and sang and waved flags bearing images of his face. His voice cracked with exhaustion and emotion as he declared, “Brazil is back!”

For many Brazilians I spoke with, though, the main reason for celebrating Lula’s victory was not that it would return the P.T. to power but that it would prevent another four years of Bolsonaro. João Moreira Salles, a documentary filmmaker, the founder of the magazine Piauí, and an astute political observer, told me, “That he could win in these conditions is nothing short of stunning. But we might remember the election as the most admirable part of Lula III. Winning was indeed epic. Governing might be a lot less rewarding.”

Lula’s team was uneasy. He had won by just over two million votes, making this the closest election in Brazil’s history. Bolsonaro had not conceded, and his supporters insisted that the election had been rigged. Along with a large contingent of bolsonarista truckers, they swarmed onto highways to block traffic and, in some cases, to erect burning barricades, halting commerce across the country.

For days, Bolsonaro remained out of sight and issued no public statements. Finally, he made an appearance at the Planalto Palace, apparently under pressure from allies. In a brief, stiff ceremony, he suggested that his supporters had every right to express their anger, but should not block the roads: “Our methods should not be those of the left, which have always been bad for the populace.” As soon as Bolsonaro was finished, he turned and walked off, while his chief of staff remained to say that officials from the current administration would be meeting with Lula’s team to begin handing over power.

There was going to be a transition, it seemed. But, within days, the mobs that had occupied the country’s highways had moved to new positions outside military garrisons. There, they set up camps and demanded an intervention to stop Lula—the thief, the Communist—from taking away their country.

Outside the main gates of the Southeast Military Command, a sprawling Army headquarters in São Paulo, several hundred bolsonaristas held a daily vigil. Men and women draped in Brazilian flags or wearing the national colors of yellow and green stood chanting, “S.O.S., armed forces!” Some held fists in the air. Several knelt to pray, their eyes closed and their arms outstretched in the fashion of Pentecostalism, which has a large following in Brazil. Some had their faces contorted in expressions of pain; others looked to Heaven, beseechingly.

Men strode in front of the chanting crowd, urging them on. When I approached several women to ask why they were there, demonstrators nearby became hostile, screaming at them, “No talking!” With rising hostility, the crowd began to yell, “Go away, dirty press!,” until I backed off.

As I left, I passed a clothesline strung between trees, which was hung with soccer jerseys, many of which were emblazoned with a 10—the number of Neymar, Brazil’s soccer star, who had recently declared that he was a bolsonarista. Alongside them was a green-and-yellow banner that read, in English, “Our flag will never be red. Out Communism.”

All over the country, crowds had gathered to protest and to pray for an intervention. In the U.S., Tucker Carlson broadcast their claims of fraud on his show. On November 2nd, he said, “According to official tallies, a convicted criminal and avowed socialist called Lula da Silva beat the incumbent President of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, by a narrow margin this weekend. And yet millions of Brazilians—millions—don’t believe that’s what actually happened. . . . There are questions about whether all the ballots had been counted. Why so many were thrown out. Millions. And whether election laws were violated in the process. So we can’t render judgment on those questions, but if you care about democracy, if you think the process is essential, then you would look into those allegations.”

Steve Bannon echoed Carlson. Just days after he was convicted of refusing to testify before Congress about his role in the January 6th insurrection, he went on social media to claim that Brazil’s election “was stolen in broad daylight.” He called Lula “a Criminal Atheistic Marxist” and the pro-Bolsonaro demonstrators “freedom fighters.”

Brazil’s military had largely remained quiet throughout the monthlong electoral process. A week after the second round of voting, it still had not produced the results of its inspection of voting machines. In São Paulo, Lula admitted to feeling fretful about the delay. “This report should have been delivered before the elections,” he said.

His concerns extended beyond the silence of the military. When I told him about the protesters outside the Army garrison, he turned grim. “I think we need to find out who is financing and who is feeding them, because this is not spontaneous,” he said. The day before, he’d had a discouraging talk with the governor of Pará state, in the Amazon. “When police went and tried to unblock the roads, demonstrators shot up their car,” he said. “The entire country is like this. And Bolsonaro has locked himself inside his house. We are not used to this kind of thing here. Since the return of democracy, elections have always been respected.”

Lula mentioned reports that pro-Bolsonaro police around the country had interfered with his voters on Election Day, and had assisted bolsonaristas who blocked the highways. Lula said that he wasn’t worried about being kept out of office: “It may be difficult, but, you see, the law exists to give guarantees to society.” The problem was instability, and Bolsonaro’s seeming willingness to deploy the police to keep Lula out of office. “This election was atypical,” he said, “because it was the candidacy of a candidate against the state—an absurd thing.”

Like many others, Lula likened what was happening in Brazil to the Trump phenomenon in the U.S. January 6th had established a destabilizing precedent all over the world. “Whatever disagreements you may have with the United States, it still represents the face of democracy on planet Earth,” he said. “When the most important country fails to exercise democracy, you are giving an endorsement to all the crazies in the world.”

In speeches, Lula often raises the need to address hunger in Brazil, describing it as an unassailable moral imperative. He talked at length about hunger when we met in 2019, and with increasing emotion in his campaign appearances last year. In our interview after his recent victory, it came up when I questioned him about Ukraine. A few months earlier, he’d made acerbic remarks about Volodymyr Zelensky, and had seemed to suggest, as Vladimir Putin had, that the United States was partly responsible for the conflict. Apparently eager to set the issue aside, Lula told me that he intended to talk with Zelensky and Putin, and with Biden as well, but that all he cared about was “world peace.” Soon enough, he returned to the issue of hunger. “I can’t, I can’t, I can’t betray these people,” he said, tears welling in his eyes. “I’ll have to fight with the markets sometimes, but people have to be able to eat again. I don’t want anything much, but people have to have hope again, and a full belly, with morning coffee and lunch and dinner.”

Lula remains an earnest believer in the leftist project in Latin America. But, as Cardozo, Rousseff’s minister of justice, told me, “Lula is not a man who theorizes about politics like Lenin or Trotsky. He is a pragmatist, a trade unionist.” He added, “He is also a political genius and a charismatic man. Inside the P.T., everyone below Lula fights against one another, but not against him. That’s how he conserves his power.”

Lula’s team is mostly made up of fairly doctrinaire leftists, but he has brought in some ideological diversity, in an effort to reassure the business lobby and other conservative interests. His Vice-President is Geraldo Alckmin, a center-right physician who once ran against him for President. His minister of planning and budget is Simone Tebet, who leans to the right on the economy. But Cardozo suggested that he’d need to go further to cultivate people who disagreed with him. “The extreme right is going to be strong and make permanent efforts to destabilize things. To keep the P.T. in its place and the extreme right in its place, he will need a broad alliance,” he said. “You can’t put out a fire with alcohol.”

A couple of days after I met Lula in São Paulo, he travelled to Brasília, hoping to widen his network of allies. Even as he had retaken the Presidency, Bolsonaro’s party had won ninety-nine seats in Congress, forming the largest bloc in the lower house; in the upper house, it secured fourteen of eighty-one seats. For Lula to run the country, he would have to make a deal with the Centrão, a shape-shifting coalition of right-of-center parties that have come to wield extraordinary power in the capital. The Centrão has few ideological allegiances; its members’ main imperative seems to be exchanging their votes for lucrative concessions for their constituencies, and for themselves.

But the Centrão was increasingly aligned with the hard right. It had voted out Rousseff in 2016 and then protected her successor, Temer. It had also effectively partnered with Bolsonaro when he joined one of its parties, the Partido Liberal, to run in last year’s election. Brazilian politicians change parties often. Bolsonaro has belonged to nine. The leader of the lower house of Congress, Arthur Lira, has belonged to five. Lira was a main beneficiary of Bolsonaro’s “secret budget,” and the person Lula most needed to cultivate on this trip. Judging by their encounter, Lira was eager to make a deal; he came out of Congress to greet Lula warmly.

But Valdemar Costa Neto, the president of the Liberal Party, had decided to stick with Bolsonaro. A canny, amiable man in his seventies, Costa Neto was a former Lula ally; in 2012, he was convicted on money-laundering charges related to the mensalão scheme, and spent two and a half years in detention before he was pardoned. “I had to rebuild the Party when I got out, because my image was destroyed,” he told me. The Liberal Party had traditionally leaned to the center, but he had shifted it right, and eventually the affiliation with Bolsonaro had paid off. “Now we have ninety-nine congressmen,” he said, scribbling figures on a scrap of paper to demonstrate how much funding they were bringing in. He explained brightly, “We have to make room for the extreme right now.”

Costa Neto said that he had nothing against the new President. Smiling, he told me that Lula had recently asked if he would back his coalition, but he’d shown him the math and Lula had understood. But, he added, Bolsonaro didn’t approve of him talking to Lula: “Bolsonaro’s not like you or me. He’s not normal.”

Costa Neto said that he thought Lula had won the election fairly. He recalled telling Bolsonaro to accept the results, relax, take a break, become the honorary president of the Liberal Party, and rebuild for the next elections. But Bolsonaro truly believed he had won, he said—he was wounded and “really depressed.” Costa Neto threw up his hands in exasperation. At Bolsonaro’s insistence, he had hired a company to investigate his claims of voting-machine fraud, and, Costa Neto said, it had come back with “troubling data.” He explained vaguely that the issue had to do with voting machines that had inexplicably identical serial numbers. In a few days, he said, he was going to hold a press conference on the matter.

He confessed to feeling anxious, because the claim of fraud would surely bring “three times as many people onto the streets as those already camped out in front of the Army bases.” But Bolsonaro was an important ally, and Costa Neto had promised to advance his cause. A few days later, he held his press conference. The claim was quickly rejected by Brazil’s electoral tribunal; the military had already assessed its sample of voting machines and declared Lula the legitimate winner. Still, the report generated a flurry of headlines—enough to feed the bolsonaristas’ conviction that there had been a conspiracy.

On the afternoon of January 8th, Bolsonaro supporters poured into the federal district of Brasília, overrunning the complex that houses the three branches of government—the Three Powers, as they are known. In the plaza, protesters gathered to confront soldiers protecting the buildings. Others prayed, or yelled slogans: “Brazil was whored out by those nasty, corrupt people!” Rioters forced their way in, shattering windows and setting fires. The district police, led by a former Bolsonaro official, offered little resistance, and sometimes provided aid.

Marina Dias, a Brazilian journalist, was near the Ministry of Defense when she saw an older woman dressed in a camouflage shirt, of a kind that bolsonaristas wear in tribute to the armed forces. The woman said that she had been camped out at the military headquarters in Brasília for two months. She had joined the protest on the eighth to urge Bolsonaro to hide; she explained that Alexandre de Moraes, the head of the Supreme Electoral Court, was conspiring to have him killed.

Dias, like other observers, was confused by the timing of the riots. Why wait until a week after the inauguration? When she asked the woman if she was inspired by the January 6th insurrection in the U.S., another protester yelled, “Don’t answer her! She’s a journalist, a leftist!” Sensing a threat, Dias walked away, but she was surrounded by bolsonaristas, and someone tripped her. “I fell to the street, where people kicked me and punched me,” she told me. “Two men tried to protect me, saying, ‘You will kill her and ruin our movement.’ ” But women were scratching her, pulling her hair, grabbing for her phone. Someone snatched her glasses, broke them, and yelled, “We have to kill her!”

Finally, a military officer forced his way through the crowd and pulled her away. As the officer escorted her off, “people yelled that I was a whore, and someone threw a bottle of water at me,” she told me. “It was clear they felt like there would be no punishment.”

On the day of the insurrection, Lula and Janja were visiting the city of Araraquara, in São Paulo state, five hundred miles away. But they were able to monitor the situation, an aide told me. One of Lula’s bodyguards entered the Planalto Palace, recorded the rampage, and shared it with the President in real time. No one noticed the bodyguard, the aide said, because “they were all filming themselves, too.”

Outside the President’s offices, on the third floor, the rioters wrecked furniture and destroyed art: a seventeenth-century French clock, a painting by Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, an ancient Chinese vase. The vandals broke nearly everything they encountered, but they were stopped at a glass door outside Lula’s private office by his personal security team—a group of longtime loyalists, which includes a former federal police officer who oversaw Lula’s imprisonment and then went to work for him after he was freed.

From São Paulo, Lula and his team worked to assert control, starting by organizing the dismissal of the Bolsonaro official who led the district police and replacing him with a loyalist. As they scrambled, Lula received a phone call from his minister of defense and the chief of staff of the armed forces. They proposed that he sign a “law-and-order assurance”—a directive that would effectively hand them power to reëstablish control. Lula refused, fearing that it was the first step in a coup. Instead, he ordered military police to retake the buildings of the Three Powers. The Supreme Court and the Planalto Palace were quickly secured, and then officers turned their focus on Congress, deploying horses, water cannons, and pepper spray to clear the building and the roof. As helicopters dropped tear gas, protesters ran, coughing and struggling for air. By about seven o’clock that evening, the building had been cleared.

Despite the ferocity of the violence, many Brazilians believed that it was less an attempted coup than an act of political theatre. People took selfies and FaceTimed friends. One rioter, streaming video as he entered Congress, asked viewers to subscribe to his YouTube channel. Venders sold spectators grilled chicken and cotton candy. “On the surface, 1/8 was a resounding failure,” João Moreira Salles said. “The mob ransacked empty buildings and didn’t even try to occupy them. It was more of a simulacrum of a coup, a spectacle—a coup for the Instagram age.”

The lawlessness of the attack had demonstrated Bolsonaro’s hold on his loyalists, but it had also damaged him politically. “It means the end of Bolsonaro as a democratically viable candidate,” Moreira Salles argued. Soon after the elections, Bolsonaro had fled to Florida, and reportedly was staying near Orlando, as the guest of the Brazilian mixed-martial-arts fighter José Aldo. After four turbulent years as President, he suddenly didn’t seem to have much to do. He looked for a church to join. One afternoon, he was spotted sitting alone at a KFC, eating fried chicken out of a box. Admirers reported, with astonishment, that they had been able to drop by his house for a chat. “He’s completely isolated, and his influence is reduced to the fringe of Brazil’s extreme right,” Moreira Salles said. “Flying to Disney when the going gets tough is not exactly conducive to becoming the next strongman.”

The Biden Administration has said that it would take seriously a request to extradite Bolsonaro, but Lula has not yet submitted one. Even from Orlando, though, Bolsonaro can have an effect on Brazilian politics. Like many of his supporters, he is a skilled provocateur. During his Presidency, his opponents faced such vicious attacks online that Brazilians spoke about a clandestine “office of hate,” run by Bolsonaro’s allies. The P.T. is less adroit on social media. (Its leaders are largely older; one told me that sixty is considered young.) Members of Lula’s administration told me that the solution was greater regulation of the media, particularly on the Internet. “You can allow total freedom, but you cannot allow evil, hatred, the encouragement of lies to gain space,” Lula said.

In Moreira Salles’s view, people who were radicalized online were unlikely to succeed in toppling the government. “The danger is of an endless repetition of smaller January 8ths around the country,” he said. “Roads blocked, refineries occupied, that sort of thing. If they can’t seize power, then the next best thing is to make the current Presidency utterly chaotic.”

Still, the threat of political violence remains real; in December, police stopped a bomb plot against Lula. People close to him are particularly concerned about the military, and perplexed by its reluctance to quell the violence on January 8th. It has bases near the Three Powers buildings, and its troops secured the compound during a demonstration in 2017—but this time, despite repeated requests in the preceding days to step up security, it had intervened late, and seemingly halfheartedly. At least fifteen members of the military and the security forces are linked to the insurrection, including a retired senior officer of the Navy and a retired general of the Army reserves.

On Paulista Avenue, in São Paulo, a raucous crowd celebrated Lula's victory in the Presidential election. Photograph by Larissa Zaidan for The New Yorker

When Bolsonaro was President, he handed over large swaths of the government to the armed forces, appointing more than six thousand military personnel to the civilian bureaucracy. To assert control, Lula knows that he will have to purge some officers and cultivate many others. It will be delicate, unpopular work. “The armed forces didn’t join Bolsonaro’s efforts to remain in power, otherwise he would still be in Brasília,” Moreira Salles said. “But they are not coming forward to condemn the events of January 8th. Lula has to decipher this silence and bring the military to his side. It’s going to be one of his hardest tasks. History shows that the armed forces in Latin America are not guarantors of democracy.”

Some of the politicians who benefitted from Bolsonaro’s rise are figuring out how to keep up their momentum without him. Sergio Moro, the judge who put Lula in jail, was for a time a kind of folk hero for right-wing Brazil. In the recent election, he launched a campaign for President before dropping out to support Bolsonaro, whom he coached through the debates. He also ran for the Senate, and won a seat, representing his home state of Paraná, in southern Brazil.

I met him in his office in Curitiba, the state capital, in a modern tower that stood above a downtown of tidy lawns, churches, and steak houses. A neatly groomed man with a deacon’s seriousness, he was imperturbable as we talked about his role in the political combat of the past few years.

When I asked why he had agreed to serve as Bolsonaro’s justice minister, Moro said that he had hoped to do some good for the country: “Who wouldn’t try that?” Before 2018, he said, he’d known almost nothing about Bolsonaro. When I noted that Bolsonaro was already famous for offensive behavior, Moro fidgeted. “I heard from a lot of people who said, ‘I’m relieved that you’re joining the government, because you will be the voice of moderation.’ And I never endorsed any kind of attacks, verbal attacks of the President against women or anything like that,” he said.

Moro pointed out that he had quit his post after a year and a half, after Bolsonaro forestalled a police investigation into one of his sons’ activities. When I asked if he believed that Bolsonaro was guilty of the offenses he had been accused of, he nodded. Then why had he rejoined him during the debates with Lula? “I have never recanted what I said in the past,” he said. “The past is the past. But, if you have a second round with two options, you need to make a choice.” But why imprison one politician you regard as corrupt and aid another? “Well, we are talking about different levels of corruption. And you need to consider other issues. I don’t believe in the economic thoughts of the Workers’ Party.”

Moro did not deny that Lula had won the election, yet he spoke sympathetically about the people who questioned his legitimacy. “I am against any kind of violence or any kind of coup,” he said. “But there are a lot of people unsatisfied with the return of Lula, because there’s this perception that the corruption scandals were not solved in a proper way. So these people believe that Lula should never have been a candidate.” Even before January 8th, he acknowledged that the protesters had “committed some mistakes.” But, he said, “I believe Brazilian democracy should give these people an answer and understand them, and not treat all of them as kind of villains. They are not. They have families—they have children.”

People close to Lula were grappling with the same essential concern: How could they bring Bolsonaro voters over to their side? Lula’s protégé Guilherme Boulos is a forty-year-old activist and politician. We met for breakfast in a buffet-style “kilo” restaurant, where customers pay according to the weight of the food piled on their plates. He lamented, “Before, the opposition was, if you will, civilized. We have a real problem in the countryside.”

As the founder of the Homeless Workers’ Movement, Boulos spent years organizing takeovers of disused buildings to provide shelter for Brazilians in need. He won a legislative seat in the recent elections, and will work closely with Lula. When I asked about the bolsonaristas, he said, “We have to learn to talk to those people.” But he suggested, in the tones of a New Yorker talking about Texans, that Brazil’s rural areas were effectively a different country. “It’s a mostly right-wing culture, which revolves around the idea that one’s properties must be protected from left-wing land invasions,” he said. “Its economic program is neoliberal, and it is socially moralistic. Therein lies our problem: the left hasn’t attended to this sector, and it really has to, if it wants to defeat bolsonarismo.”

Lula, he said, “has an extraordinary capacity to govern and to articulate points in common with different sectors.” But the past four years had made bridging the differences much more difficult: “Bolsonaro didn’t govern—he set out the guideposts for an ideological battle, and he almost beat us by nearly winning reëlection!”

Boulos estimated that bolsonarista extremists represented ten to twelve per cent of the Brazilian population: “These are the people who don’t believe in the pandemic, who defend the use of torture, and who believe that the Earth is flat.” The key, he said, was to improve their economic opportunities. “There are those who say Brazil has increasingly become a polarized country. I’d argue that it’s always been polarized. Think of it: this country is the third-largest food producer in the world, while thirty million of its citizens go hungry, and one per cent of the population owns most of the resources. Of course there’s going to be polarization!” He reminded me that when Lula left office the electorate had overwhelmingly supported him—“because their lives were better!” Now, though, there was less money flowing; the economy was in a downturn, and the country was still recovering from the pandemic. “Lula’s margin of maneuverability will be reduced,” he said.

In the weeks after Lula won the election, he often seemed as if he hoped to simply return the country to the time before Bolsonaro took over—when the Amazon was less imperilled, the economy was thriving, and Brazil was in a cohort of fast-ascending countries. “It was the best moment of social rise of the poor people in Latin America,” he told me in São Paulo, adding, “Let’s recover the brics!”

Four days after the January 8th insurrection, his administration released its economic plan, which called for restoring the Bolsa Família, increasing aid to the poor, rolling back privatization, and increasing taxes on gasoline. According to Brian Winter, the editor of Americas Quarterly and a longtime analyst of Brazilian politics, “The announcements basically got a C-plus from the markets—nobody too excited, nobody too upset.” But Winter was not optimistic that Lula’s government would be able to spend its way out of a decade-long slump.

Recovering the Amazon will be harder still. During Bolsonaro’s term, as ranchers and miners cleared land, fires consumed an area of rain forest estimated to be the size of Belgium. The region is rife with anti-government sentiment, and Lula and his allies are effectively asking residents not to take advantage of the valuable resources around them. One rancher I spoke with said, “How can you live on top of a treasure chest and not be able to do anything with it?”

Lula’s environment minister is Marina Silva, who served for five years during his first tenure but resigned in frustration over his desire to balance conservation with development. Now Lula had called her back, promising a zero-tolerance policy on deforestation. Silva, a rubber tapper’s daughter of Black Brazilian descent, is an evangelical Christian, a soft-spoken, long-haired woman in her sixties. At her office in Brasília, she told me that she hoped to expand sustainable agriculture while halting illegal deforestation. She acknowledged that there would still be violations of environmental laws, and that the process would take time. “We won’t be able to do this in four years—that would be utopian,” she said. “The problem during Bolsonaro was that the transgressors had total impunity. With Lula, at least, the expectation of impunity will end.”

Lula and his aides are conscious that the world will judge them less by the details of ordinary governance than by their handling of monumental crises: the collapse of the environment and the near-collapse of democracy. Simone Tebet, his planning minister, told me, “President Lula’s big problem is not just economic. He can solve the problem of inflation, the problem of unemployment, reduce social inequality, reduce the percentage of poor people in Brazil. But, if you don’t work on political pacification and unity, in four years’ time bolsonarismo will come back with force.” At seventy-seven, Lula had only one term left, and a great deal to do, Tebet reasoned. “He wants to clean the soul of Brazil,” she said. “He wants to halt injustice. I have no doubt that he will assemble a team for this. What worries me is whether he will have the strength, ability, discernment to understand that his main role is not just these four years. It is building bridges so that we can, in 2026 and 2030, have democratic governments in Brazil.” ♦

— Published in the print edition of the January 30, 2023, Issue of The New Yorker, with the headline “Lula’s Restoration.”

0 notes

Text

How Did Republicans Gain Control Of Southern Governments

New Post has been published on https://www.patriotsnet.com/how-did-republicans-gain-control-of-southern-governments/

How Did Republicans Gain Control Of Southern Governments

The Return Of Conservative Control

Shortly after the election, the North Carolina House of Representatives brought charges against Holden, which alleged that he acted illegally in declaring martial law and arresting individuals; in refusing to obey the writs of habeas corpus; and in raising state troops and paying them. After a seven week trial, the Senate convicted Holden and voted to remove him from office. He became the first state governor in the country to be impeached and removed from office. Lt. Gov. Tod R. Caldwell replaced him as governor.

For the most part, after the 1870 election and the return of the Conservatives to power, Klan activity ceased in many areas. The group remained active in the western counties, resulting in federal intervention and trials for Klan leaders. By 1872, the Klan became more focused on race rather than politics and ceased to play a major role in North Carolina’s political circles until the next century.

Back in legislative power, the Conservatives set about changing much of what the Republicans had accomplished. They amended the constitution in 1873 and again in 1875, concentrating power in Raleigh and ensuring that only white Conservatives would hold local offices through legislative control of county governments. Other amendments, like those that outlawed interracial marriage and prohibited integrated public schools, served to relegate African Americans to a lower level of society and politics: the status quo antebellum.

Politics Of The Southern United States

United States Census Bureau

The politics of the Southern United States generally refers to the political landscape of the Southern United States. The institution of had a profound impact on the politics of the Southern United States, causing the American Civil War and continued subjugation of African-Americans from the Reconstruction era to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Scholars have linked slavery to contemporary political attitudes, including racial resentment. From the Reconstruction era to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, pockets of the Southern United States were characterized as being “authoritarian enclaves”.

The region was once referred to as the Solid South, due to its large consistent support for Democrats in all elective offices from 1877 to 1964. As a result, its Congressmen gained seniority across many terms, thus enabling them to control many Congressional committees. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, Southern states became more reliably Republican in presidential politics, while Northeastern states became more reliably Democratic. Studies show that some Southern whites during the 1960s shifted to the Republican Party, in part due to racial conservatism. Majority support for the Democratic Party amongst Southern whites first fell away at the presidential level, and several decades later at the state and local levels. Both parties are competitive in a handful of Southern states, known as swing states.

New Census Numbers Shift Political Power South To Republican Strongholds

Political power in the United States will continue to shift south this decade, as historically Democratic states that border the Great Lakes give up congressional seats and electoral votes to regions where Republicans currently enjoy a political advantage, according to new data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Texas, Florida and North Carolina, three states that voted twice for President Donald Trump, are set to gain a combined four seats in Congress in 2023 because of population growth, granting them collectively as many new votes in the electoral college for the next presidential election as Democratic-leaning Hawaii has in total.

At the same time, four northern states with Democratic governors that President Biden won in 2020 Illinois, Michigan, Pennsylvania and New York will each lose a single congressional seat. Ohio, a nearby Republican-leaning state, will also lose a seat in Congress.

The data released Monday was better for Democrats than expected, as earlier Census Bureau estimates had suggested the congressional gains in Florida and Texas would be even bigger. The margins in certain states that determined the final congressional counts were razor thin, with New York losing a seat because of a shortfall of only 89 people.

Your questions about the census, answered

In other parts of the country, the shifts in population will have a less obvious effect on partisan power.

Ted Mellnik contributed to this report.

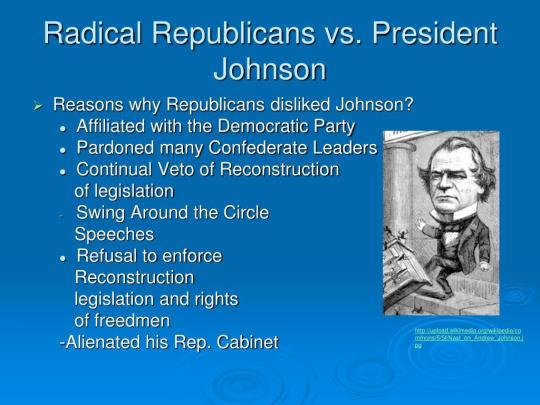

The Radical Republicans Take Control

Northern voters spoke clearly in the Congressional election of 1866. Radical Republicans won over two-thirds of the seats in the House of Representatives and the Senate. They now had the power to override Johnson’s vetoes and pass the Civil Rights Act and the bill to extend the Freedmen’s Bureau, and they did so immediately. Congress had now taken charge of the South’s reconstruction.

Republican America: How Georgia Went ‘red’

July 15, 2004

Relaxing in front of his small ranch house, watching the birds flit around his feeder, Ronnie Pilcher looks out over the changing face of the place he calls home.

In the four decades he and his wife have lived here on 10 verdant acres, Mr. Pilcher has seen an explosion in population and wealth that’s transformed this old orchard crossroads into a booming Atlanta exurb. Where once he knew almost everyone driving by on the old Birmingham Highway – and many of them stopped to chat – now an unfamiliar flow of Beemers and Hummers weave among the dented Fords and Chevys on the traffic-choked road. Nondenominational megachurches are replacing small country chapels, gated communities are spreading rapidly, and big chain restaurants compete with old-time establishments like Shelia’s BBQ, where the sign says proudly: “Parking for Rednecks Only.”

Pilcher, a Baptist deacon and retired data cruncher for SunTrust Bank, says he’s an independent. But as a self-described conservative, he identifies with the GOP far more than with the Democrats. Like many in Crabapple, he admits his vote for President Bush this fall is pretty much assured.

It’s not just because he sees Bush as standing up for “traditional” morals – though he is firmly against gay marriage, and on abortion says: “Only the good Lord has the right to choose life and death.”

Georgia’s swift transformationFrom farms to a surge of new wealthOzzie, Harriet, and a white picket fenceFrom the wallet to the pews

The South Becomes Majority Republican

For nearly a century after , the majority of the white South identified with the Democratic Party. Republicans during this time would only control parts of the mountains districts in southern Appalachia and competed for statewide office in the former border states. Before 1948, Southern Democrats believed that their stance on states’ rights and appreciation of traditional southern values, was the defender of the southern way of life. Southern Democrats warned against designs on the part of northern liberals, Republicans , and civil rights activists, whom they denounced as “outside agitators”.

After the Civil Rights act of 1964 and The Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed in Congress, only a small element resisted, led by Democratic governors Lester Maddox of Georgia, and especially George Wallace of Alabama. These governors appealed to a less-educated, working-class electorate, that favored the Democratic Party, but also supported segregation. After the Brown v. Board of EducationSupreme Court case that outlawed segregation in schools in 1954, integration caused enormous controversy in the white South. For this reason, compliance was very slow and was the subject of violent resistance in some areas.

White Terrorists Resist The Changes

Even before the end of the Civil War, white Southerners had begun to resist the changes occurring in the societyand culture they cherished. The familiar world they had known, in which black people existed as inferior beings fit only to serve whites, was falling down around them, and they fought back. They did so through violent attacks that included arson, beatings, rape, and murder. These attacks were focused not only on the former slaves but on anyone who tried to help them or seemed sympathetic to the idea of freedom, civil rights, and equality, including teachers, soldiers, and white Unionists.