#Napoleon B

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

what the flip nelson in g&b

427 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean when the players don’t even make it out of the catacombs

Twit: @CoeurDeLuciole

#guts and blackpowder#gnb#jean guts and blackpowder#roblox#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#Jean louis le petit oui oui duboire#g&b#g&bp#roblox art#my artwork

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

“But when I met you, right away, I knew that you would never, ever, ever hurt me.” - You Love Me by Kimya Dawson

(Reference picture below)

#g&b#gay people#wow good for them#digital#my art#art#fanart#guts and blackpowder#gnb#roblox art#digital art#napoleonic era#napoleon#roblox#red string of fate#artists on tumblr

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you sent actual napoleonic figures into the G&B universe(totally ooc):

#art#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#marshal davout#louis nicolas davout#michel ney#marshal ney#gutsandblackpowder#g&b

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vive la France

Forget to post this

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first gbp oc and his name is probably Felix do yall think he’s

freaky

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Duty calls, Jacob.

Close up & bonus below

This addition of subtitles was a fun idea I got near the end of my process, so since this was an afterthought, the canvas isn't the correct size xD

And what does that line even mean? Decide yourself.

"There are cannibals nearby, you cannot stop now." "There are survivours nearby, they need your help"

#g&b#guts and blackpowder#art#gnb#guts & blackpowder#artists on tumblr#napoleonic era#<- im playing with fire rn xdddddd i meannn its technically correct?#jacob guts and blackpowder#transformice art#transformice#transformiceart#aight idk about the era tag if its bothering the actual community ill remove it

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barry... HE DIDNT DESERVE TO DIE HE DESERVES TO LIVE HAPPILY WITH ME

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

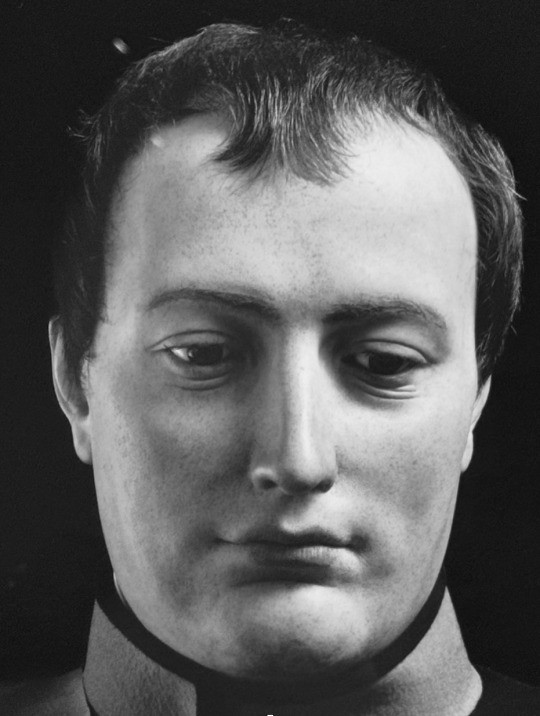

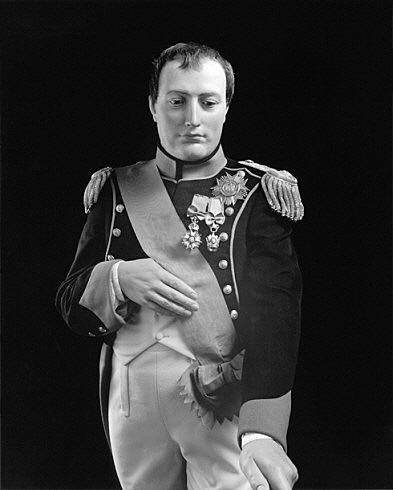

Napoleon Bonaparte by Hiroshi Sugimoto, c. 1999

From Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Portraits, a series of depictions of historical and contemporary figures. Sugimoto isolated wax figures from staged vignettes in waxworks museums, posed them in three-quarter-length view, and illuminated them to create haunting Rembrandt-esque portraits of historical figures, such as Henry VIII, Napoleon Bonaparte, Fidel Castro, and Princess Diana.

(Guggenheim)

#crying because he looks so soft#soft boy <3#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Hiroshi Sugimoto#Sugimoto#napoleonic era#napoleonic#wax figures#first french empire#french empire#art#photography#black and white photography#history#historical figures#1800s#vintage photography#photograph#b&w photography

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nurse activities 101:

milka, again, YOU GO GIRL!!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

birthday gift :3

#guts and blackpowder#gutsandblackpowder#napoleonic era#gnb#gnb oc#g&b#g&bp#g&b oc#gbp#napoleonic wars

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pumpkins drawn at school should be regarded as Halloween 🤓 (I wanted to paint it on dark brown No)立了

#napoleon#napoleonic wars#napoleon bonaparte#alexander i of russia#tsar alexander i#guts and blackpowder#g&b#art

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

End of Vardo gameplay:

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Ferryman x Jacob is the ship ever.

How do I call this ship??? Exportation Barrels maybe???

#guts and blackpowder#g&b#gnb#g&b jacob#jacob guts and blackpowder#guts and blackpowder jacob#jacob g&b#jacob gnb#american ferryman gnb#american ferryman g&b#american ferryman guts and blackpowder#jacob x american ferryman#mlm ship#yaoi#headcanon design#my art#art#digital art#bnc's stupid art#i love napoleonic yaoi so much

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Go on. Ask me about my G&b ocs.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

My g&b oc and he’s extremely stupid

31 notes

·

View notes