#Namely the Bretons the Bretons speak french

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I've been thinking. Several people think O!Ciel's birth name should be revealed on the last page of the manga. If it's "Fin" wouldn't that be extremely fitting? Technically speaking it would be both an Irish and a french name... the end. The end of the story... maybe even the end of his life. 😈

#I thought the same thing too#So we can both be satan#Also a lot of people of Celtic origin speak french#An entire celtic people speak french#Namely the Bretons the Bretons speak french#And so does 20% of Ireland#Does anyone here reading my tags listen to Cécile Corbel?#And wonder why her music sounds similar to Irish or Scottish or Welsh music even though she sings a lot of her work in French?#She's a breton#The more you know#Finnian name theory#Fenian name theory#Also god damn it

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel that one of the most overlooked aspects of studying the French Revolution is that, in 18th-century France, most people did not speak French. Yes, you read that correctly.

On 26 Prairial, Year II (14 June 1794), Abbé Henri Grégoire (1) stood before the Convention and delivered a report called The Report on the Necessity and Means of Annihilating Dialects and Universalising the Use of the French Language(2). This report, the culmination of a survey initiated four years earlier, sought to assess the state of languages in France. In 1790, Grégoire sent a 43-question survey to 49 informants across the departments, asking questions like: "Is the use of the French language universal in your area?" "Are one or more dialects spoken here?" and "What would be the religious and political impact of completely eradicating this dialect?"

The results were staggering. According to Grégoire's report:

“One can state without exaggeration that at least six million French people, especially in rural areas, do not know the national language; an equal number are more or less incapable of holding a sustained conversation; and, in the final analysis, those who speak it purely do not exceed three million; likely, even fewer write it correctly.” (3)

Considering that France’s population at the time was around 27 million, Grégoire’s assertion that 12 million people could barely hold a conversation in French is astonishing. This effectively meant that about 40% of the population couldn't communicate with the remaining 60%.

Now, it’s worth noting that Grégoire’s survey was heavily biased. His 49 informants (4) were educated men—clergy, lawyers, and doctors—likely sympathetic to his political views. Plus, the survey barely covered regions where dialects were close to standard French (the langue d’oïl areas) and focused heavily on the south and peripheral areas like Brittany, Flanders, and Alsace, where linguistic diversity was high.

Still, even if the numbers were inflated, the takeaway stands: a massive portion of France did not speak Standard French. “But surely,” you might ask, “they could understand each other somewhat, right? How different could those dialects really be?” Well, let’s put it this way: if Barère and Robespierre went to lunch and spoke in their regional dialects—Gascon and Picard, respectively—it wouldn’t be much of a conversation.

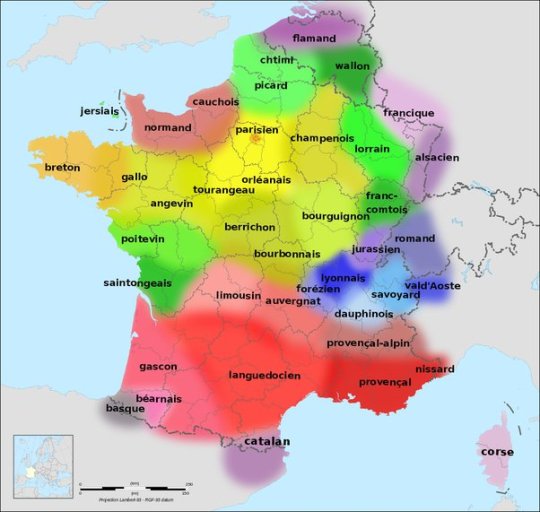

The linguistic make-up of France in 1790

The notion that barely anyone spoke French wasn’t new in the 1790s. The Ancien Régime had wrestled with it for centuries. The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, issued in 1539, mandated the use of French in legal proceedings, banning Latin and various dialects. In the 17th and 18th centuries, numerous royal edicts enforced French in newly conquered provinces. The founding of the Académie Française in 1634 furthered this control, as the Académie aimed to standardise French, cementing its status as the kingdom's official language.

Despite these efforts, Grégoire tells us that 40% of the population could barely speak a word of French. So, if they didn’t speak French, what did they speak? Let’s take a look.

In 1790, the old provinces of the Ancien Régime were disbanded, and 83 departments named after mountains and rivers took their place. These 83 departments provide a good illustration of the incredibly diverse linguistic make-up of France.

Langue d’oïl dialects dominated the north and centre, spoken in 44 out of the 83 departments (53%). These included Picard, Norman, Champenois, Burgundian, and others—dialects sharing roots in Old French. In the south, however, the Occitan language group took over, with dialects like Languedocien, Provençal, Gascon, Limousin, and Auvergnat, making up 28 departments (34%).

Beyond these main groups, three departments in Brittany spoke Breton, a Celtic language (4%), while Alsatian and German dialects were prevalent along the eastern border (another 4%). Basque was spoken in Basses-Pyrénées, Catalan in Pyrénées-Orientales, and Corsican in the Corse department.

From a government’s perspective, this was a bit of a nightmare.

Why is linguistic diversity a governmental nightmare?

In one word: communication—or the lack of it. Try running a country when half of it doesn’t know what you’re saying.

Now, in more academic terms...

Standardising a language usually serves two main purposes: functional efficiency and national identity. Functional efficiency is self-evident. Just as with the adoption of the metric system, suppressing linguistic variation was supposed to make communication easier, reducing costly misunderstandings.

That being said, the Revolution, at first, tried to embrace linguistic diversity. After all, Standard French was, frankly, “the King’s French” and thus intrinsically elitist—available only to those who had the money to learn it. In January 1790, the deputy François-Joseph Bouchette proposed that the National Assembly publish decrees in every language spoken across France. His reasoning? “Thus, everyone will be free to read and write in the language they prefer.”

A lovely idea, but it didn’t last long. While they made some headway in translating important decrees, they soon realised that translating everything into every dialect was expensive. On top of that, finding translators for obscure dialects was its own nightmare. And so, the Republic’s brief flirtation with multilingualism was shut down rather unceremoniously.

Now, on to the more fascinating reason for linguistic standardisation: national identity.

Language and Nation

One of the major shifts during the French Revolution was in the concept of nationhood. Today, there are many ideas about what a nation is (personally, I lean towards Benedict Anderson’s definition of a nation as an “imagined community”), but definitions aside, what’s clear is that the Revolution brought a seismic change in the notion of French identity. Under the Ancien Régime, the French nation was defined as a collective that owed allegiance to the king: “One faith, one law, one king.” But after 1789, a nation became something you were meant to want to belong to. That was problematic.

Now, imagine being a peasant in the newly-created department of Vendée. (Hello, Jacques!) Between tending crops and trying to avoid trouble, Jacques hasn’t spent much time pondering his national identity. Vendéen? Well, that’s just a random name some guy in Paris gave his region. French? Unlikely—he has as much in common with Gascons as he does with the English. A subject of the King? He probably couldn’t name which king.

So, what’s left? Jacques is probably thinking about what is around him: family ties and language. It's no coincidence that the ‘brigands’ in the Vendée organised around their parishes— that’s where their identity lay.

The Revolutionary Government knew this. The monarchy had understood it too and managed to use Catholicism to legitimise their rule. The Republic didn't have such a luxury. As such, the revolutionary government found itself with the impossible task of convincing Jacques he was, in fact, French.

How to do that? Step one: ensure Jacques can actually understand them. How to accomplish that? Naturally, by teaching him.

Language Education during the Revolution

Under the Ancien Régime, education varied wildly by class, and literacy rates were abysmal. Most commoners received basic literacy from parish and Jesuit schools, while the wealthy enjoyed private tutors. In 1791, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand (5) presented a report on education to the Constituent Assembly (6), remarking:

“A striking peculiarity of the state from which we have freed ourselves is undoubtedly that the national language, which daily extends its conquests beyond France’s borders, remains inaccessible to so many of its inhabitants." (7)

He then proposed a solution:

“Primary schools will end this inequality: the language of the Constitution and laws will be taught to all; this multitude of corrupt dialects, the last vestige of feudalism, will be compelled to disappear: circumstances demand it." (8)

A sensible plan in theory, and it garnered support from various Assembly members, Condorcet chief among them (which is always a good sign).

But, France went to war with most of Europe in 1792, making linguistic diversity both inconvenient and dangerous. Paranoia grew daily, and ensuring the government’s communications were understood by every citizen became essential. The reverse, ensuring they could understand every citizen, was equally pressing. Since education required time and money—two things the First Republic didn’t have—repression quickly became Plan B.

The War on Patois

This repression of regional languages was driven by more than abstract notions of nation-building; it was a matter of survival. After all, if Jacques the peasant didn’t see himself as French and wasn’t loyal to those shadowy figures in Paris, who would he turn to? The local lord, who spoke his dialect and whose land his family had worked for generations.

Faced with internal and external threats, the revolutionary government viewed linguistic unity as essential to the Republic’s survival. From 1793 onwards, language policy became increasingly repressive, targeting regional dialects as symbols of counter-revolution and federalist resistance. Bertrand Barère spearheaded this campaign, famously saying:

“Federalism and superstition speak Breton; emigration and hatred of the Republic speak German; counter-revolution speaks Italian, and fanaticism speaks Basque. Let us break these instruments of harm and error... Among a free people, the language must be one and the same for all.”

This, combined with Grégoire’s report, led to the Décret du 8 Pluviôse 1794, which mandated French-speaking teachers in every rural commune of departments where Breton, Italian, Basque, and German were the main languages.

Did it work? Hardly. The idea of linguistic standardisation through education was sound in principle, but France was broke, and schools cost money. Spoiler alert: France wouldn’t have a free, secular, and compulsory education system until the 1880s.

What it did accomplish, however, was two centuries of stigmatising patois and their speakers...

Notes

(1) Abbe Henri Grégoire was a French Catholic priest, revolutionary, and politician who championed linguistic and social reforms, notably advocating for the eradication of regional dialects to establish French as the national language during the French Revolution.

(2) "Sur la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser l’usage de la langue francaise”

(3)On peut assurer sans exagération qu’au moins six millions de Français, sur-tout dans les campagnes, ignorent la langue nationale ; qu’un nombre égal est à-peu-près incapable de soutenir une conversation suivie ; qu’en dernier résultat, le nombre de ceux qui la parlent purement n’excède pas trois millions ; & probablement le nombre de ceux qui l’écrivent correctement est encore moindre.

(4) And, as someone who has done A LOT of statistics in my lifetime, 49 is not an appropriate sample size for a population of 27 million. At a confidence level of 95% and with a margin of error of 5%, he would need a sample size of 384 people. If he wanted to lower the margin of error at 3%, he would need 1,067. In this case, his margin of error is 14%.

That being said, this is a moot point anyway because the sampled population was not reflective of France, so the confidence level of the sample is much lower than 95%, which means the margin of error is much lower because we implicitly accept that his sample does not reflect the actual population.

(5) Yes. That Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand. It’s always him. He’s everywhere. If he hadn’t died in 1838, he’d probably still be part of Macron’s cabinet. Honestly, he’s probably haunting the Élysée as we speak — clearly the man cannot stay away from politics.

(6) For those new to the French Revolution and the First Republic, we usually refer to two legislative bodies, each with unique roles. The National Assembly (1789): formed by the Third Estate to tackle immediate social and economic issues. It later became the Constituent Assembly, drafting the 1791 Constitution and establishing a constitutional monarchy.

(7) Une singularité frappante de l'état dont nous sommes affranchis est sans doute que la langue nationale, qui chaque jour étendait ses conquêtes au-delà des limites de la France, soit restée au milieu de nous inaccessible à un si grand nombre de ses habitants.

(8) Les écoles primaires mettront fin à cette étrange inégalité : la langue de la Constitution et des lois y sera enseignée à tous ; et cette foule de dialectes corrompus, dernier reste de la féodalité, sera contraint de disparaître : la force des choses le commande

(9) Le fédéralisme et la superstition parlent bas-breton; l’émigration et la haine de la République parlent allemand; la contre révolution parle italien et le fanatisme parle basque. Brisons ces instruments de dommage et d’erreur. .. . La monarchie avait des raisons de ressembler a la tour de Babel; dans la démocratie, laisser les citoyens ignorants de la langue nationale, incapables de contréler le pouvoir, cest trahir la patrie, c'est méconnaitre les bienfaits de l'imprimerie, chaque imprimeur étant un instituteur de langue et de législation. . . . Chez un peuple libre la langue doit étre une et la méme pour tous.

(10) Patois means regional dialect in French.

#frev#french revolution#cps#mapping the cps#robespierre#bertrand barere#language diversity#amateurvoltaire's essay ramblings

782 notes

·

View notes

Text

Placing my bets now that Undertaker's last name is Rossignol, the French word for nightingale.

In trying to explain to a friend the plot of black butler via the iceberg meme, I've become so convinced that I've figured out Cedric K. Ros-'s (aka Undertaker's) last name that I've rejoined this site to scream into the void.

At least, I haven't been able to find anything on the English/French speaking internet suggesting this theory has been floated before.

Of course, this is assuming you subscribe to the Cedric K. Ros- = Undertaker = Undertaker x Cloudia affair = Grandtaker pipeline. And, that you think he is of French/Breton origin.

Dates

Important to note that dates and numbers are important in Black Butler's story, both within the fictional narrative and in connection to real historical events (emphasized with the first arc lining up with the actual 'Jack the Ripper' murders). Some examples of this;

1819 is the year in which the real Queen Victoria (and her cousin-husband Prince Albert) were born. 1819 is also the year in which the name 'Cedric' first appears in the novel 'Ivanhoe'. Within the story, this is also right around the time that reaper 136649 attacks Reaper HQ.

1837 is the year in which the real Queen Victoria ascended the throne. In Black Butler, this is year in which Molly G., the first chronological locket on Undertaker's chain, died. 1837 would also be right around the time that Undertaker is noted as having absconded with his death scythe, officially deserting the organization...20 years after a workplace shooting (he must be union).

Vincent Phantomhive is born on Friday June 13th, 1851. Cloudia Phantomhive dies on Friday July 13th, 1866. She is 36 years old when she dies. If you believe that Undertaker's reaper serial number 136649 means he died in the year 1366 (an interesting time period in Brittany, what with the Breton War of Succession, the Hundred Years War, the Black Death...), this would mean Cloudia dies 500 years after he unalives himself.

Prince Albert dies on December 14th, 1861, in the real world. The Phantomhive twins are born on December 14th, 1875 - the 14th anniversary of Prince Albert's death. Vincent is 24 years old when he becomes a father. The manor is attacked on December 14th, 1885 - the 24th anniversary of Prince Albert's death. Vincent is 34 years old when he dies. There's speculation that the story will end on Friday December 13th, 1889 - the twin's last day of being 13 years old, before they turn 14 years old on December 14th, 1889, the 4th anniversary of the attack on the manor.

TLDR, dates matching up with historical events/publications is not coincidental. Yana pays attention to her numbers.

Now, back to Cedric K. Ros-

I've read speculation that the 'Ros-' must have something to do with roses, since Phantomhives are so often associated with roses (and their thorns). Guess what little bird is very commonly associated with roses? Whose song is often associated with melancholy, longing, and mourning? Who so often seems to unalive themselves on thorns?

"the nightingale...can also be seen to provide a link to something, opening out onto something beyond the self. Heard but not seen, the nightingale represents an intangible presence; a longing that can be either terribly earthly, in the guise of sexual desire, or soaringly spiritual, as when the nightingale represents the soul, rising above."

Some fun facts about nightingales;

Female nightingales are mute, only male nightingales sing - though historically people thought the opposite, so many of the nightingales in literature are female.

It is one of the only birds that sing throughout the night (name means 'night singer').

In Persian poetry, the nightingale is a symbol of a lover who is "eloquent, passionate, and doomed to love in vain" - the object of their affections is the rose, which "embodies both the perfection of earthly beauty and the arrogance of that perfection."

The oldest appearance of nightingales in literature goes back to the myth of Philomela, who was turned into a nightingale by the Gods.

In Shakespeare's poem 'Lucrece', the titular character is inspired to commit suicide when a nightingale leans their breast against a thorn to inspire a song and ward off sleep.

The nightingale also makes an appearance in Shakespeare's 'Romeo & Juliet', when Juliet mistakes the song of a lark for that of a nightingale.

I have read a ridiculous amount of poetry about nightingales recently (there is a lot of it), but I'm going to focus on one Breton piece from the middle ages and two English pieces from the 19th century because they have the most relevant dates (which as previously mentioned, are important).

Laüstic

There is the Breton lai 'Laüstic', composed in the late 12th century by Marie de France (Laüstic' is the Breton word for rossignol/nightingale). Breton lais are a form of medieval French romance literature that often involve supernatural and fairy-world Celtic elements.

"In most of Marie de France’s Lais, love is associated with suffering, and over half of them involve an adulterous relationship... In Marie's Lais, "love always involves suffering and frequently ends in grief, even when the love itself is approved.""

The lais of Marie de France explore courtly love, a popular theme in medieval literature that began with Troubadour poetry in southern France in the 11th century.

"The courtly lover existed to serve his lady. His love was invariably adulterous, marriage at that time being usually the result of business interest or the seal of a power alliance. Ultimately, the lover saw himself as serving the all-powerful god of love and worshipping his lady-saint. Faithlessness was the mortal sin...The courtly lover, while displaying the same outward signs of passion, was fired by respect for his lady."

Basically, courtly love emphasized the importance of a man's respect and devotion to their lover, and I don't think anyone could doubt Undertaker's devotion to his cause.

Sidenote: I think the French story 'Floire et Blancheflor', one of the oldest and most popular romances of the middle ages, is also incredibly relevant to Undertaker & Cloudia's love story. It also explores this concept of 'courtly love' (involving a fake tomb, a prince disguised as a merchant, and an attempted suicide, no less)...and the flowers associated with the lovers are red roses and white lilies... You can read part one of my theory on Floire et Blancheflor here.

A plot summary of 'Laustic' from Wikipedia:

Two knights live in adjoining houses, in the vicinity of Saint-Malo in Brittany; one is married and one lives as a bachelor. The wife of the married knight enters into a secret relationship with the other knight, but their contact is limited to conversation and the exchange of small gifts, since a "high wall made of dark stone" separates the two households. Typically, the lady rises at night, once her husband is asleep, and goes to the window to converse with her lover; whenever her lover is home, she is kept under close watch. Her suspicious husband demands to know why she spends her nights at the window, and she says she does so to listen to the nightingale sing. He mocks her, and orders his servants to capture the nightingale. When it is caught he brings it to the lady's chambers, denying her requests to release the bird. Instead, he breaks its neck and throws it at her, "bloodying the front of her tunic just a bit above her breasts". After he leaves, the lady mourns the bird's death and the suffering she must accept, knowing she can no longer be at the window at night. She wraps the nightingale's body in silk, and embroidered with writing in gold thread, and charges her servant to deliver the bird and her message to her lover, who, in response, preserves the nightingale in a reliquary, a small vessel which he has encased with small jewels and precious stones, and carries it with him always.

From the Wikipedia on reliquaries;

"A reliquary (also referred to as a shrine, by the French term châsse, and historically also referred to as a phylactery) is a container for relics. A portable reliquary may be called a fereter, and a chapel in which it is housed a feretory or feretery." "Relics may be the purported or actual physical remains of saints...The term is sometimes used loosely for containers for the body parts of non-religious figures; in particular, the kings of France often specified that their hearts and sometimes other organs be buried in a different location from their main burial." "In Buddhism, stupas are an important form of a reliquary and may be buried inside larger structures such as a stupa or chorten."

Interesting, because the wooden grave markers Undertaker carries/uses to conceal his death scythe are considered to be a variant of stupa (as far as I can tell). The grave markers are sotoba inscribed with sutra - also interesting to note that in Japan, nightingales are considered a religious bird because "its song is reminiscent of the intonation of a Buddhist sutra", which in turn ties into the Buddhist prayer beads he wears around his neck.

The concept of reliquaries is somewhat similar to that of mourning lockets, especially if you consider that in the context of courtly love Undertaker was whipped likely worshipped the ground Cloudia walked on and would have treated her like a saint (good for her).

"Reliquaries are decorative vessels, often in the form of a hand, cranium, or other body part that contain the fragment of a saint or someone of holy importance. Some fragments could include remnants of a garment worn by the individual or even a piece of bone that was part of their body."

A famous reliquary is the Holy Thorn Reliquary, commissioned in late 14th century France by John, Duke of Berry (this dude has relevance to Brittany and the Hundred Years War) to house a relic of the crown of thorns.

"The jewels, which would have been keenly appreciated by contemporary viewers, include two large sapphires, one above God the Father at the very top of the reliquary, where it may have represented heaven, and the other below Christ, on which the thorn is mounted."

Sapphires and a crown of thorns are not new symbols in this story - imma leave it at that because I'm getting off topic and this is already ridiculously long.

The Nightingale and The Rose

The short story The Nightingale and the Rose by Oscar Wilde (snake's snakes) was published in the book of bedtime stories The Happy Prince and Other Tales in May 1888 (which lines up pretty closely with when the first chapter of the manga takes place). This is a bleak tale about the selfless and sacrificial nature of true love.

But the Tree cried to the Nightingale to press closer against the thorn. ‘Press closer, little Nightingale,’ cried the Tree, ‘or the Day will come before the rose is finished. So the Nightingale pressed closer against the thorn, and the thorn touched her heart, and a fierce pang of pain shot through her. Bitter, bitter was the pain, and wilder and wilder grew her song, for she sang of the Love that is perfected by Death, of the Love that dies not in the tomb. And the marvelous rose became crimson, like the rose of the eastern sky. Crimson was the girdle of petals, and crimson as a ruby was the heart. But the Nightingale's voice grew fainter, and her little wings began to beat, and a film came over her eyes. Fainter and fainter grew her song, and she felt something choking her in her throat. Then she gave one last burst of music. The white Moon heard it, and she forgot the dawn, and lingered on in the sky. The red rose heard it, and it trembled all over with ecstasy, and opened its petals to the cold morning air. Echo bore it to her purple cavern in the hills, and woke the sleeping shepherds from their dreams. It floated through the reeds of the river, and they carried its message to the sea. 'Look, look!' cried the Tree, 'the rose is finished now;' but the Nightingale made no answer, for she was lying dead in the long grass, with the thorn in her heart.

The emphasis on the nightingale's song also brought to mind the Mother 3 theory and the importance of the music in that game - and the idea that the last names of Undertaker's lockets make a chord progression. IDK that much about Mother 3, so I can't say if there are any other further parallels to draw.

Also who would read this to a child as a bedtime story???

Undertaker. Undertaker would totally read this to Ciel as a bedtime story, who am I kidding.

An Ode to a Nightingale

Finally, there is the poem "An Ode to a Nightingale" by John Keats (another one of snake's snakes).

There is a clear theme of death in this poem, and of life after death/immortality. There is also a sense of longing for death, of the relief death brings - very relevant for all reapers.

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk: 'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot, But being too happy in thine happiness,— That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees In some melodious plot Of beechen green, and shadows numberless, Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

The first stanza mentions 'Lethe', which is one of five rivers in the Greek underworld. "The shades of the dead were required to drink the waters of the Lethe in order to forget their earthly life. In the Aeneid, Virgil writes that it is only when the dead have had their memories erased by the Lethe that they may be reincarnated."

Afaik the only reaper to reference their previous life is Sascha, and there weren't many specifics. This could just be because speaking of their human life is painful, given they all made the choice to end it...Or is it possible HQ alters their memories?

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been Cool'd a long age in the deep-delved earth, Tasting of Flora and the country green, Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

The reference to Provencal song is once again a reference to the concept of courtly love (seen in Laustic) that began with Troubadour poetry in Provence, France in the 11th century.

Already with thee! tender is the night, And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne, Cluster'd around by all her starry Fays; But here there is no light, Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.

Stars and heaven reference (Astre/Sirius & Ciel), and a reference to the moon as in the Oscar Wilde story... The Queen Moon, on her throne...

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet, Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs, But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet Wherewith the seasonable month endows The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild; White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine; Fast fading violets cover'd up in leaves; And mid-May's eldest child, The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine, The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

A reference to May (we will come back to this), to musk-roses (symbolizes 'capricious beauty'), and to 'the murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves'. As previously mentioned, Cloudia dies in July...

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time I have been half in love with easeful Death, Call'd him soft names in many a mused rhyme, To take into the air my quiet breath; Now more than ever seems it rich to die, To cease upon the midnight with no pain, While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad In such an ecstasy! Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain— To thy high requiem become a sod.

The suicidal ideation is strong here.

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird! No hungry generations tread thee down; The voice I hear this passing night was heard In ancient days by emperor and clown: Perhaps the self-same song that found a path Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home, She stood in tears amid the alien corn; The same that oft-times hath Charm'd magic casements, opening on the foam Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

Immortality. The last few lines immediately brought to mind the theory that Undertaker drowned himself.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell To toll me back from thee to my sole self! Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well As she is fam'd to do, deceiving elf. Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades Past the near meadows, over the still stream, Up the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deep In the next valley-glades: Was it a vision, or a waking dream? Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

The last stanza has the poet bidding 'Adieu' - the French word for goodbye forever which translates literally as 'until God'. Gotta love how dramatic the French are.

From Wikipedia:

"The nightingale described experiences a type of death but does not actually die. Instead, the songbird is capable of living through its song, which is a fate that humans cannot expect. The poem ends with an acceptance that pleasure cannot last and that death is an inevitable part of life."

And here's the thing...Keats composed this poem in one day after a nightingale built its nest near his home. Specifically, he wrote it in one day of May, 1819 - the same month and year in which Queen Victoria was born.

The rest might be me just grasping at straws but the connection to Queen Victoria's birth is what I find most convincing, since Yana has seemingly already sourced Cedric's first name from literature in 1819. I think the setting/plot of the novel 'Ivanhoe' and her name choice of 'Cedric' reveals a lot about Undertaker's past and his motivations, and I think the same could hold true for his last name. I am convinced his name is Cedric K. Rossignol.

God only knows what the 'K.' stands for.

Thanks for reading! My ask box is open and I'm always happy to talk about this stuff. You can find a masterpost of my Black Butler theories here - they mostly revolve around medieval French/Breton literature, French history and French Christianity.

#kuroshitsuji#undertaker#black butler#claudia phantomhive#cloudia phantomhive#Cedric K Ros#Undertaker theory#Undertaker x Claudia#Yana Toboso terrifies me#I've read more poetry in the last few weeks than in my entire life#I've learned more about medieval french history and literature than I ever needed to know#being bilingual is finally paying off#tw: suicide#Idk if this even makes sense

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to LÉGENDES RUSTIQUES

Portrait by Auguste Charpentier, 1838

Original French at Project Gutenberg

English Translation:

To Maurice Sand

My dear son,

You have collected a variety of traditions, songs, and legends, which you also did very well, in my opinion, to illustrate; for these things are only ever lost as the peasantry is enlightened, and it is good to save from this quick-marching oblivion a few versions of that great poem of the marvellous which humanity has nourished for so long, and of which the country folk are today, unbeknownst to themselves, the last bards.

I would therefore like to help you gather some scattered fragments of these rustic legends, the roots of which are found almost all over France, but to which each locality has imparted its unique colour and the stamp of its own imagination.

- George SAND

Foreword

We should find some name for this nameless poem of the universal fabulous or marvellous, whose origins date back to the appearance of mankind on Earth and whose versions, multiplied by infinity, express the poetic imagination of every age and of every people.

The chapter on rustic legends, about the spirits and visions of the night would, in itself, be an immense work. In what corner of the Earth could one escape the popular imagination (which is never anything other than an indistinct or altered form of collective memory), safe from these dark apparitions of evil spirits who chase before them the weeping larval wraiths of their innumerable victims? Where peace now reigns, war, pestilence, or despair will have passed by before, and most terribly so, over the history of mankind. The growing wheat has its foot in human flesh, the dust of which has fattened our furrows. Everything under our feet is ruination, blood, and wreckage, and the world of fantasy, which either ignites or stupefies the minds of the peasantry, is an unpublished history of times gone by. When we want to trace back the root origins of a story, we will find them within some truncated or distorted legend, where we are rarely able to identify a proven fact consecrated by official history.

The peasant is therefore, one could say, the only historian from prehistoric times that remains with us still. Honour and success to those who dedicate themselves to the search for the marvellous traditions of each hamlet which, when collected or grouped, and when compared with one another and minutely dissected, could perhaps cast a great light onto that deep night of the primitive ages.

But it would be the work and the journey of a lifetime even just to explore this in France. The peasant still remembers the tales of his grandmother, but getting him to speak becomes more difficult every day. He knows that whomever is interviewing him is no longer a believer, and he begins to feel a sort of pride, which is certainly estimable, in refusing to serve as curiosity’s plaything. On the other hand, one cannot warn researchers enough that there are also innumerable versions of the same legend, and that each bell tower, each family, and each cottage has its own. Rustic poetry, like rustic music, has as many composers as there are individuals.

I love the marvellous too much to be anything other than a professional idiot. Besides, I must not forget that I am writing the text of a collection devoted to a selection of legends collected on site, and I will strive to collect, along with memories from my youth, some of the stories which define certain fantastic motifs common to all of France. It is in a corner of Berry, in which I have spent my life, that I will be forced to set my legends, because it is there and not elsewhere that I encountered them. They do not have the great poetry of Breton song, where the genius and the faith of old Gaul left a clearer imprint than it did anywhere else. With us, these reminiscences are more vague and more veiled. The marvellous, in our central provinces, is more analogous to that of Normandy, of which an erudite, patient, and conscientious woman has painted a perfect portrait [1].

However, the Gallic spirit bequeathed its features to all of our rustic traditions, as well as a colour which is re-encountered everywhere in France; a mixture of terror and irony, an extraordinary inventive oddness joined with naïve symbolism attesting to the need for true morality within delirious fantasy.

Berry, covered with the ancient debris of mysterious ages past, tombs, dolmens, menhirs (standing stones), and mardelles (pit-houses) [2], seems to have preserved within its legends some memories which predate the Druidic cult: perhaps those of the Cabeiri gods, which our antiquarians place prior to the appearance of the Kimris people on our shore. The sacrifice of human victims seems to hover like a horrible memory in certain visions. Walking cadavers, mutilated phantoms, headless men, and arms or legs without bodies populate our moors and our old abandoned pathways.

And then come the more orderly superstitions of the Middle Ages, still hideous, but more intentionally turned towards the burlesque; impossible animals whose grimacing figures twist within the sculptures of Roman and Gothic churches, who continue to roam alive and howling around cemeteries and within ruins. The souls of the dead knock upon the doors of the houses of the living. The Sabbath of personified vices and strange imps passes whistling within the storm cloud. The entire past is re-animated and all of the beings which Death has dissolved, even the animals, recover their voices, their movements, and their appearances; the furniture, fashioned by men as well as violently destroyed by them, straightens up and creaks upon its worm-eaten feet. Even the stones rise up and speak to the frightened passer-by; the night-birds sing out to men in dreadful tones, as does the hour of death, always reaping and always passing by, yet which seems to never be the end of anything on the face of the Earth thanks to this belief in the certainty that all beings and all things must protest against nothingness, and, taking refuge in the region of the marvellous, illuminate the night with sinister lights or populate the emptiness with floating figures and mysterious words.

George SAND

Whomever wishes to do serious scholarly work on central Gaul should consult the excellent work of M. Raynal, the historian of Berry, the text of Les Esquisses Pittoresques (Picturesque sketches) by M. de La Tremblays and M. de La Villegille, and the research by M. Laisnel de La Salle into certain curious local phrases, etc.

G.S.

#légendes rustiques#george sand#maurice sand#french literature#in translation#folklore#rustic legends#october#french folklore

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Morgan was around 10, Sister Marian had all the girls of Morgan's age present to the class the story of their Biblical namesake. The idea was to deliver the moral of each of these characters, and to vow to live up to it.

Ruth talked about how she would always be there for her family, no matter what she had to sacrifice.

Sarah talked about how she would trust what God said no matter how surprising it may seem.

Leah wanted to talk about how she would sneak in at the last second and steal her sister’s man, but she didn’t dare say that to Sister Marian, so instead she said something about being obedient even when you aren't happy.

All three Marys got together and argued at length over who would get to be Jesus’s mom, and who would have to be Martha’s sister or the Magdalene. In the end, they could only stop arguing if nobody got to be Jesus’s mom, and the third one of them had to settle for the woman Paul meets in Romans 16.

A few of the girls had to do some research with the priest’s help. Judith discovered that she was named for Esau’s wife; Anna for a prophetess in Luke; Gabriella for the angel Gabriel (though perhaps that one shouldn’t have been difficult to figure out).

And of course a few kids here and there had names that weren’t originally from the Bible. Christina got to speak of being Christian, and Arabella got to speak of being “given in prayer.” Lillian, Viola, and Rosa got to share a presentation about flowers and nature.

In other words, everyone else in Morgan’s class had a name that was either in Latin or right out of the Bible. They all had names they could learn about, that they could recognize, that came from an acceptable culture. This was an elite noble convent after all, for the third daughters of important men with more to gain from currying favor with the church than currying favor with another noble. She was the king’s step-daughter, after all.

But “Morgan” was not a Latin name-- and it wasn’t a Bible name either. It was a Breton name. She was named by her mother, duchess of Cornwall and princess of Avalon. Her sister was going to be queen of Lothian. While she didn’t know it yet, she herself was going to be queen of Wales. This was Britain; she had a Breton name, not some importation from the French or the Romans. She would eventually learn to take pride in that.

But she was not taking pride then, as a ten year old student of a nunnery, completely alone and unable to explain the origins of her own name. She was excused from the presentation, and instead got to give a brief talk on any Biblical woman of her choice, and she chose Delilah. She chose Delilah because she liked the story of a woman taking initiative and not always being kind and honest, but then she was the only girl talking about a woman you shouldn’t imitate in addition to all the other ways she was standing out.

A while after that, her sister was married to the King of Lothian; she was 21, and he was 24. An extremely lucky pairing for her, all things considered. Morgan had leave to go visit for the wedding, and while they were alone, she asked her sister if she knew where her name came from.

Morgause laughed. Her laugh was always so high-pitched, but crisp and clear and never shrill.

“They didn’t know?,” she said.

“Everybody else was named for a saint or something,” Morgan said shyly.

“Well you certainly aren’t that,” Morgause said gleefully. “You were named for the mary-morgans!”

Morgan stared, unsure.

“The mari-morgans. The drowner spirits! The merrow, the sirens, the children of dead Dahut?” She put her arm around little Morgan and pulled her in close. “You’re named for the dread enchantresses who live in the sea, who draw out sailors and dash them against the rocks. You are powerful, and magical, and alluring, and deadly. And just like the mari-morgans, you are going to rule the world from your throne in the sea, and anyone who tries to take on Morgan the Fairy will drown.” She kissed the top of her little sister's head.

Morgan hated that nickname, but when Morgause said it, it sounded like a complement. Something to be proud of. She clung to that feeling and buried her head in her sister’s chest. It had been so long.

#morgan le fay#morgause#arthuriana#arthurian legend#fan fic writing#backstory#names#sunday school#britain#bible

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are Brentonce and Francane exonyms? Cause they don't really feel native to either of their real-life languages

The joke of the names "Bretonce" and "Francane" is that they're Britain and France with the ending sounds switched - well, OK, in Britain's case its an old timey spelling/pronunciation, but still. Breton + the "ce" of France, Franc + the "ain" of Britain (but spelled "ane" cause it looks better to me). I also pronounce Francane with a hard c so it sound like "frank," since franks and the bretons were specific ethnic groups in the middle ages.

The reason why I did thus goes back to the interconnected nature of the folklore traditions these fictional countries are based on - British and French folklore have a lot of overlap, in part because of the real world countries' fraught and tangled history together. So their Midgaheim counterparts reflect that by being so interconnected that they've exchanged parts of each others' names.

Midgaheim in general works on the Tolkien idea of "you are reading an English translation of stories that were told in another tongue." No one in Midgageim speaks English or French or what have you, but rather made up fantasy languages. Since I'm not as much of a Linguistics nerd as Tolkien is, I have not created made up languages to use, so I just use modern languages in their stead - i.e. when we need to establish that a Frankish character is speaking a different language than a Bretonch speaker, she'll have her dialog be in French. But she's not really speaking French, just as Bilbo Baggina isn't really speaking English - it's just a translation convention.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally, it seems to us that the integration of the Bretons into the continental culture is linked with the accession of the family of Cornouaille to the ducal power. Before that, as early as the beginning of the 11th century, Benoit, Count of Cornouaille, chose to give to his son the glorious name of Alan, and then to marry him to Judith of Nantes, a descendant of Alan Barbetorte, who, according to the Chronicle of Nantes, was victorious against the Normans. This testifies to the political will to establish the growing power of his lineage on the memory of his ancestor’s exploits and to be linked with the prestigious times of the Breton kings, Nominoé, Erispoé, Salomon and Alan the Great. The princes of Cornouaille were cultured. Alan Canhiart had had a religious and lay education and his son Hoël, count of Nantes, then first Duke of Brittany from the house of Cornouaille, supported two bards in his service. Some literary works, known only by their Old-French version, such as the lais of Tydorel and Graalent, seem to have been born in this political and cultural milieu. Thus, we can better understand why Salomon, Hoël, Rispeu and others became literary characters beyond their native land. As for Hoël’s heir, Alan Fergant, he succeeded in unifying the duchy: last Duke of Brittany to speak Breton; cited in the Welsh literature; married to a Norman princess and then to an Anjevin one, he took part in the first crusade and was a loyal ally to King Henry Beauclerc.

Patrice Marquand, Cultural connections between Brittany and Aquitaine in the Middle Ages (10th- 13th centuries) : ’The Matter of Britain’ and the ’Chansons de Geste.’

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"[Jeanne de Penthièvre] presented a new point which d’Argentré deemed ‘tresnotable’: that the nature of Brittany did not allow it to be confiscated, since it had never been part of France in the first place. This was based on the nature of previous homages from the duke to the king, and maintained a fiction (which the later Montfortists were also to embrace) that no fealty was actually entailed. The conclusion drawn from this version of the Franco-Breton relationship was that the king could take no such action unilaterally, but needed the consent of the Breton lords and people. This claim was closely tied to an argument that had been advanced for the Penthièvre succession in 1341, whereby French control over Brittany was limited simply because of how the duchy had become a French fief: the duke had submitted his duchy to the king, not received it as a gift. The emphasis on the royal status of the duchy, however, was new, and aligned more closely with the Montfortist position of 1341.

... We do not know what response, if any, the king’s lawyers made to this argument, though it took more than a week of deliberation, until 18 December, for the pronouncement of the sentence of condemnation. Both Jeanne and Jean found themselves deprived of their rights, though it was not until April that the change was put into effect. But Charles V inadvertently found himself suddenly deprived of allies as the elites of Brittany put up a strong resistance to the king-as-duke’s attempted takeover of the duchy. On 25 April 1379 they created a league to ‘help one another for the guarding and defence of the ducal rights of Brittany, against all those who might want to take ownership and possession of the said duchy, except for the one to which it must belong in the true line’, a statement of intent which nicely left undefined who that might be. Among most of the major barons, Jeanne’s name was not listed, though she gave them her support and would be included first among the backers of Jean IV for negotiations in October 1379. Her participation in the events to come speaks to her continued clout among the Breton elite, but also to the complicated political tightrope which she had to walk: with her son-in-law as the royal representative in Brittany (and presumably still no love lost for Jean IV) it was prudent for her to keep her options open, and more importantly to formally avoid any compromising situations which might prejudice her in future.

However, drastic steps had already been taken … The league of barons had already sent envoys to England to seek out the exiled duke… As the situation intensified, it became increasingly urgent to change Jeanne’s mind. But better an heirless duke with whom she had a treaty, than a king who had rejected her right to be called duchess. Jean IV did not actually return to reclaim his duchy until August 1379, at which point Jeanne was apparently amenable to her cousin’s presence. The Chronicon Briocense had her at his reception at Dinan, where she set an example for the rest of the lords and, with Jean, received their praise. Whatever conviviality there may or may not have been, this committed Jeanne fully to relying on the eventual applicability of the ‘escape clause’ in the Treaty of Guérande. The duke’s return prompted a further bout of combat and tense negotiations, but Charles V died from illness in September 1380, and a few months into the reign of his successor (Charles VI, a minor under the tutelage of his uncles, including Louis d’Anjou) Jean IV signed the second Treaty of Guérande, which essentially renewed the terms of the first. Jeanne and her son Henri swore to uphold this agreement on 2 May 1381.

Unlike the first treaty, the second did not drive Jeanne to another self-imposed exile from Brittany. In fact, she took up residence in La Roche-Derrien and, as far as our records show, mostly stayed there for the next three years. Presumably during this time she was mostly concerned with the administration of her northern lands. This endeavour was sometimes undertaken in concert with the reinstated Jean IV: when he conceded certain rights to Charles de Dinan on 12 July 1381, Jeanne reissued the grant as her own reward for Charles’ services. Very few acta survive from before her death on 10 September 1384, however,which is an unfortunate loss for the sake of comparison to the period 1365–75. She was buried, as planned, next to Charles at the Franciscan church of Guingamp, as was fitting for ‘the most illustrious lady Jeanne, most outstanding mother and daughter of the order of the Friars Minor, duchess of Brittany, wife of Charles de Blois (of good memory)’"

-Erika Graham-Goering, Princely Power in Late Medieval France: Jeanne de Penthièvre and the War for Brittany

#SLAY GIRL 🌟#historicwomendaily#jeanne de penthievre#14th century#breton history#war of breton succession#queue#my post

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Whats the difference between the north and south of France, culturally

To be honest, France can't be divided between North and South. France is a very unique country because it's on the crossroad of Mediterranean Europe, Northern Germanic & Celtic Europe. Even our language is the hybrid result of all these cultures.

France's population is literally the result of a great replacement mixing of Gallic (natives - who themselves were super diverse) with Romans who invaded them coming from the Mediterranean pool.

Every French kid learn how the last Gallic warrior (Vercingétorix) surrendered to Julius Cesar

After that, for a good chunk of french History, kings worked to unify the kingdom because regions didn't speak the same language. French as we know is actually "parisien" language and all the other languages slowly fell into irrelevancy (although the last decades the government is trying to revive/protect them after being pressured to do so - some region are VERY defensive of their culture and language ex. the Bretons, Basques, Corses...)

Now to explain the main difference with France that don't solely abide in north/south division, I made you a little drawing

Northern France - violet : super poor. It's a region that historically hosted the country textile manufacturers and fell off because of the deindustrialization. Known for being lovely & homely people (which is true). They eat Camembert with coffee in the morning............

Has a stigma of being inbred and pedophiles because of the many incestuous & pedoscandals and child abduction gravitating this region. The fact that it's on the frontier of Belgium and Netherlands (the capital of childp*rn) has definitively something to do with it

Upper West coast - green : super famous for its cows and milk products (cheese, butter, etc.) and bad weather. Bretons are known to be extremely proud of their cultural heritage and had some terrorist movements against the French government to defend them from their erasure 💀

Paris zone - brown : Paris & the banlieues. Extremely socially diverse. Extreme poverty and extreme wealth. Political & cultural capital of France.

Upper east zone - blue : (I was born there <3) like the north of France, use to be an industrial centerfold of the country (metallurgy - they use the metal from that region to build the Statue of Liberty) and then fell off after deindustrialization.

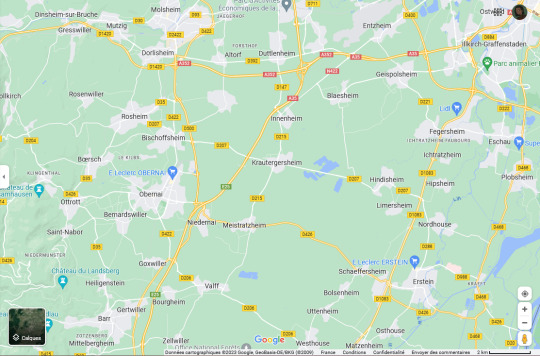

Its closeness to Luxembourg allows many professional opportunities to work abroad (especially in the banking system). The European Parliament has one of its siege here (Strasbourg) because it's on the crossroad of other European countries

This region used to be German between the two WW therefore many cities have German sounding names (the region became French again after Germany lost WWII).

Growing up there as a kid, I remember there was still a HUGE influence of German culture. I learned German before English (I lost everything though lol)

believe me or not, all of those cities are in France🫡

Lower East coast - black : CULTURED FRANCE. That's where Champagne comes from (région Champagne). Bordeaux is the biggest city of that zone and is known to be a more cultured version of Paris for real connoisseurs 👀

Cote d'Azur - red : zone where the far right makes its highest score. Super rich old people go retire there. Cannes festival. Incredible beach. Most Mediterranean zone of France.

....But there's also Marseille which stands out like a sore thumbs because it's a city a lot of corruption and a HUGE North African/Muslim population. EXTREMELY DIRTY and dangerous (lots o gang violence). Lots of corruption too...

Corsica - pink : they fought for decade for their independence against France lol Still do this day hate France lmao Famous for its anti-France terrorism and killing a French préfet 💀 Are known to bomb the holiday house of French people who constructed there because they don't want "foreigners" to invade their island💀💀

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

You were talking about wanting to learn about colonisation, I know most about 2 examples:

1) what's happening in New Caledonia

2) breton history and language recognition

So 1) France owns new Caledonia and they agreed to have a vote every [amount] of years (I don't remember exactly) to decide if they become independent or stay french citizens. Who can vote in that is a matter of how long they lived here, giving some power to long term settlers and some power to natives. Last time the vote was in 2021 and native people asked to report after the pandemic because online voting disadvantages native populations massively. The french government didn't and held a vote, which they refused to recognise for the above reason.

And now some fuckers are trying to change the rules on who can vote to advantage the settlers even more, which even anti-independance activists said was a horrible idea. So tensions are rising. I don't know the most about it so I encourage you to look up more complete info than what I can recall.

2) less active but still a problem- Brittany (Breizh) has been annexes by the french centuries ago, but retained massive cultural independence up until the 19th/20th century. Most of us didn't speak french, and existed basically independently under the french governments. You need to go to the 19th century to see like 50% of people speaking french. But in the late 19th/early 20th century France did what could arguably called a cultural genocide and decided to destroy the breton language systematically, often by refusing breton names, punishing people for speaking it, and most of all completely forbidding it in schools, beating children if they spoke it (people my dad's age, his family lived in Paris at the time but his cousins got it).

So these people stopped speaking breton and didn't teach it to their kids to avoid them suffering the same. And the language started dying rapidly in a few generations, as well as DOZENS of cultural practices. A lot of people started trying to revive it ever since like the 70s which is why some are still alive today. Anyways what's the point? Well, ever since the 2000s breton people have been working to keep our language and culture alive, and asking for language recognition at a legal level. France refuses to acknowledge they ever did anything to our language, let alone apologise, and refuses these protections, even re-enforcing laws that go against recognising any language but french.

And it has not just harmed our language but our culture and our independence (factual if not legal). Language is important, it's a part of your identity, and in a country where the prime minister refuses to pose with a breton flag in the background and asks it be take down, it's kinda important to have some amount of recognition for minority cultures and languages. It might be less urgent than some other fights but still.

I don't know if anything I can say can add to this but I'm posting it so if any of my few followers also want to learn they can <3

Thank you for the knowledge and the ask, I learned a lot.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Brittany/Bretagne/Breizh, France

Oct. 4, 2023

We are home and I have been too busy "being home" to finish my journal - but today I will get back at it. Our suitcases are unpacked and put away and our clothes are laundered and back where they live. We have had one sleepover, spent the day at a petting zoo, watched one soccer game and have seen 3/7 of our grandkids and 1/3 of our kids. We have had 3 Dr. appts too. No dawdling around here!

We have doled out our grandkid gifts to only one kid - but the rest of the gift giving will happen soon.

Oh - and I am still on Europe time... I am also still glowing from all the wonderful times we had during our month away and now I will re-live the last week. So, here goes...

On September 24th said farewell most of our buddies and flew from Madrid Spain to Paris, France with Annie & Carl. We rented a car and drove 5 hours northwest to Brittany. Of course at this time, I didn't realize that this region had 3 names and that "Brittany" is the English word for this region.

Before I get too far - let's look at France. It is the biggest country in Europe and is about 2.2 times the size of Michigan. But the population of France is 63.3 million people while little Michigan is struggling to reach 10 million making the population of France six times that of Michigan. Interesting.

We were the guests of long-time friends of Annie & Carl's, Francoise, her brother Gabby and his wife Danielle and they were hosting us in their Loguivy de la Mer summer house that was the original home of Francoise and Gabby's great-grandparents. Charming!!!

And here is the "de la mer" view from their front yard...

Let me just say that we were treated like royalty!! The connection here is that Francoise's daughter, Helen (prounounced "a - LYNN) was Annie & Carl exchange student in 2002.

While our pace was certainly less intense than our on OAT trip we did a lot of stuff and learned so much. Have I mentioned that the best education is travel?

So let's begin with the name of the province we call Brittany: Bretagne/Breizh. Like Basque Country, Breizh is a diverse region in northwestern France and a historic country with a distinct identity, sharing much of its Celtic heritage with Cornwall and Wales. It has its own language, (Breton) its own food specialities (crepes and sea food of all kinds), and its own flag and culture.

The flag is relatively new - from the 1970's and was first considered a "separatist" flag but it is now accepted as the province flag and is considered apolitical. Breizh has been part of France for a long, long time and while they had good times during the 700 years they were a country before 1498 - they are not getting out of France and are no longer making an effort to do so. They are - however - working hard to save their language.

All the signage is in two languages: French on top and Breton on the bottom.

I read an article that said the average age of a person who speaks Breton is 74 and that in 1950 there were one million Breton speakers, in 2000 there were 200,000 Breton speakers today is number is 80,000. Breton is regional and is spoken primarily in the western part of the province - caller Lower Brittany (in the colors on the map below). The division between Upper and Lower Brittany is language. Upper Brittany (called "upper" based on altitude of the land) speaks French, French and only French.

Francoise and Gabby, grandparents were both teachers in the 1920s when Breton was outlawed. Breton was their native language and the language of their students but to keep their jobs - they had to teach ONLY in French. If you wanted to be employed anywhere - you had to speak French. Francoise and Gabby do not speak Breton and Francoise told me she couldn't even understand it. It is not even close to French, just as Basque is not even close to Spanish.

Hey - Is there some kind of a rule book that conquerors use to get the conquered to assimilate? It is the same ol' method since time began, it appears. When we visited Tibet in 2014, all of the buildings, shops and signage was written in Tibetan on the top and Chinese on the top - in much bigger font and lit. The Tibetan people were told to learn Chinese if they wanted to work and all the schools were teaching in Chinese and that was relatively new. But I digress....

There are schools where Breton is taught as a foreign language and there are a few schools in Lower Brittany where Breton is the language of instruction. The language is listed as "Endangered" by UNESCO.

Staying in the topic of "language", I had a BLAST digging deep to try to speak French. I studied French in high school from 1966-1970 (with the dinosaurs) and took one French Literature class (in French) in college. I have brushed up repeatedly with Duo Lingo or some other app - BUT the one thing I have never done was engage in meaningful conversation with a French speaker. Our hosts' English was better than my French and I think they all had excellent receptive English - but to communicate we spoke "Franglish". I was pulling all kinds of French words right out of my butt - so to speak. I still can read French fairly well and I can buy train tickets or ask for simple directions or order food - but to converse... nope! I loved it. They were so kind and patient and if felt safe to try and make mistakes. We were able to share all kinds of information. I asked "Comment dit-on..." (How do you say...) repeatedly during a sentence and most of the time saying the word in English or pointing at the item worked. But sometimes a more info or even a little charades was necessary - for example I wanted the word for "nephew" and I had to add "the boy baby of my brother) to my sentence. It is "neveu" in case you are wondering. It was delightful and makes me want to get back to studying. My new French friends, Francoise, Gabby and Danielle are coming to the US in February and will stay with Annie and Carl in Palm Desert (while we are there) so I have a good reason to get back at it. YAY!!

We arrived around 8:00 PM on Sunday, September 24 to a lovely meal. We visited a little bit after dinner - but turned in, exhausted after a full day of travel.

Next morning we awoke to a lovely breakfast, lots of conversation and then a walk through their community.

We walked down a couple of streets filled with quaint rock homes and into a park called La Roche aux Oiseaux (Bird's Rock) and onto a trail. BEAUTIFUL!

The first photo below is the river Roc'h ar Hon that flows into the bay - the next photo. This is the same bay we can see from the front porch.

We continued our walk to the Loguivy de la Mer harbor and village. Delightful! There are indications everywhere that this village has been here a long, long time.

The tides here are high - between 5 and 6 metres (15-18 feet). At low tide all the water is gone from the harbor and all the boats are sitting in the mud.

Across from the harbor is the church where Francoise and Gabby's grandparents were married. The gate was locked so this was the pic I took. Notice the palm tree. From the harbor we looking at the English Channel and yet - palm trees grow with ease here. It has snowed - once or twice - but this is a region that doesn't get below freezing much.

This pic I snagged off the Internet.

Of course this palm tree caused me to go down a rabbit hole - but now you won't have to. Check out the map below. Where you see shades of yellow, or orange or red are indeed where you might find a palm tree. Norway? Iceland? WHAT!?! Also it turns out there are low temperature tolerant palm trees too. Who knew?!?!

I'm going to stop here - just because I have other things to do at home. I'll pick up the rest of the day with our French friends soon.

Stay tuned.

0 notes

Text

Doom!

Monday, August 7, 2023

Margaret and Tim went into the Cape Breton Highlands National Park Visitor Center to read maps, inquire about hikes and learn about the history of the area. In particular, we were interested in learning who the Acadians were. We learned they were French who were forcibly removed by the English. In this area, families were removed to make room for the park. One resident we talked to said her grandparents were getting old and didn’t speak English, only French. They were duped by government officials into giving up their home to make way for the park. Injustice is everywhere.

--

We balance our activities by discussing who wants to do what when and then doing some negotiating. Jeanne had a Zoom meeting mid morning, and Margaret and Tim wanted to go for a hike at the same time, so we compromised: Jeanne went to her meeting and Margaret and Tim went for a hike, and when Jeanne was done with her meeting, she joined the hike.

The hike was along a loop trail called Le Buttereau (meaning small hill). It was an easy, mossy walk thru the woods. We passed eight or so ruins of Acadian homes. Each homestead was marked with the name of the family and the number of children. Almost all had at least 10 kids! When Jeanne joined, we walked to the beach and a separate loop of the trail.

We stopped for lunch on a beautiful spot on the Cabot Trail overlooking the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Tim had just finished setting up the table and chairs when he saw rain coming across the gulf and threw them in the back of the van just in time. We watched several squalls heading either for Cheticamp or us or both.

After the rain stopped we drove further along the Cabot Trail to a short boardwalk loop path along a Bog. Jeanne, Margaret and Dora went to look for carnivorous plants so Jeanne could send pictures to Jake. After spotting the bladderworts and pitcher plants, Jeanne was eager to helpfully point them out to passersby. A family with a rather bored little girl came up behind us. Jeanne started explaining how the plant catches insects, “the insect sees the fake flower and then goes to the pitcher to drink the water, then DOOM!” The family were all startled. The little girl was finally interested in the bog. Success.

We headed back to Chéticamp for laundry. RVers all meet at the laundromat — there was the couple with Storyteller van like ours from NJ. We did laundry and exchanged stories of places we recommended.

No one wanted to cook, so we cruised the village discussing potential restaurants. Gluten free pizza! Who expected gluten free pizza in rural Canada? A gastronomic delight for Jeanne.

0 notes

Text

OKAY SO, I was praying for someone with a huge brain like yours to add their input to my silly AU! I'll comment on your suggestions because there's some epic stuff right here :p

I'm glad my breton headcanon for the McGill brothers had such a good reception and is widely accepted now >:) But starting with them : -Your idea of calling Jimmy Jérôme is honestly stellar, and way better than the other suggestions I've received so far. Someone suggested Yoann but I didn't wanna go for a first AND last name from Bretagne, my own idea, Jacques, feels too old-fashioned for a man born in the sixties as I said, and Jean (James' most literal traduction) is too basic and also lacks realism for a man from Jimmy's generation. Jérôme is realistic, not too ugly, close to canon, can be shortened to a stupid nickname that fits Jimmy's personality (Gégé…….. putain) and doesn't sound too bad imo. I second that.

-Charles' name being shortened to Charlie would most likely only be on Jimmy's behalf, sorry for not being clear on that! Americans use their nicknames in everyday settings in a way that french people don't, that's for sure, but I can totally picture Jimmy going salut mon charlot/charlie lol. Howard and the others at the firm wouldn't call him Charlie the same way canon Charles is called Chuck on the regular, granted. On second thought maybe Howard would, but only occasionally and not at work, but that's about it. As for the charlie hedbo connotation, it didn't even cross my mind. Better Call Saul takes place in the early 2000s, so the events of 2013 wouldn't even be pictured nor linger in people's minds, and before that I don't think anyone associated that nickname with the infamous journal. It's most likely a product of our times. Peanut's Charlie Brown would most likely pop into their minds first tbh, at least I think so.

-I absolutely adore your Kim Wexler take. I was indeed wondering if Kimberly had the same connotation in the US as it has in france (aka a lower class feel of someone who likes reality TV), but I honestly doubt it. Stéphanie is a great name for her as it retains a neutral, everyday feel, can be shortened, and Leclerc does sound like Wexler phonetically + as you said alludes to her blonde complexion/morality. How does it feel to be a genius?

-Albuquerque/Lille/Cicero talk : I adore that idea. I totally see why french BCS would fit neatly in a northern setting, and as you said, the drug traffic subplot would most likely be an European thing rather than a strictly french one, obviously. I need to research the specifics before drawing Lalo and the others because I truly know nothing about that topic, but it's great!

-Latouche for Saul is extremely funny, but it reminds me too much of th Ducobu comics fjkdfgfg. I do see why it'd fit tho, and I'll add it to the suggestions I've had so far :] I also thought of something that rimes with his catchphrase rather than something too puny in itself. We truly haven't found the perfect Saul Goodman french equivalent, folks!

-Bill Oakley/Guillaume Duchêne in the red prosecutor dress is not only a great addition, but something I will immediately draw >:) I was frustrated at the lack of prosecutors in BCS (for... normal reasons obviously) so thank you for reminding me of him!

Okay, I'm cracking my knuckles as we speak because there's gonna be some new art incoming lol. Thanks for being so inspiring and for feeding the AU so perfectly! <3

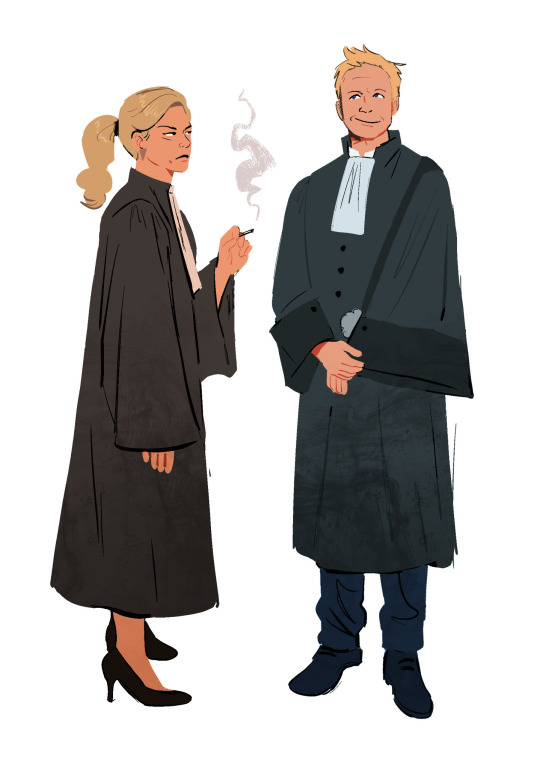

Thinking about better call saul if the action took place in france just because I wanted to see them in cunty robes lmao. More thoughts under the cut!

Obviously the action and the whole premise of bcs/brba wouldn't work in france (legal system aside, the whole cartel and walter white storyline would have to suffer major changes due to social security and the mexican cartel well. not existing here stricto sensu). But let's talk about the real Important Stuff : their names

I think Howard Hamlin would work well as Edouard Hamelin. He looses the cool HH initials yes, but it works really well as a genuine french name imo, and Howard/Edouard are pretty close phonetically

Chuck could still be called Charles without any realism issue, but he'd be nicknamed Charlie rather than Chuck because that's what a french person would go for... nicknames don't work the same, yeah

Kimberly Wexler and James McGill, I have no idea lmao. James when translated becomes Jacques, but it's such a boomerish uncool name that I cannot resolve myself to call my boy like that. It's also one generation too old. Jimmy being born in '60 could technically be called Jacques, but it'd be old-fashioned, as it's a name mostly given to the kids of the decade that came before him. McGill is an irish name, so something funny could be making Jimmy a breton with a funky last name like Gall/LeGall ? That's hilarious to me. But who knows.

Saul Goodman is a pun, so this is even harder for me to conceptualize. Saul's marketing would definitely not work in france at all, as no one would realistically hire a lawyer with a puny name and such chaotic displays (+ I think ads for legal démarchage are illegal mind you). However, let's have a crack at it. It would have to be a pun based off an expression similar to "it's all good man", or implying something positive and familiar... I need to think on that one.

#je pourrais répondre en français mais je veux que le monde sache...#bref tu as un cerveau cosmique et je ne serais que l'humble serviteur de ces ajouts grandioses!#cosigned because that was some real shit you said#french au

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

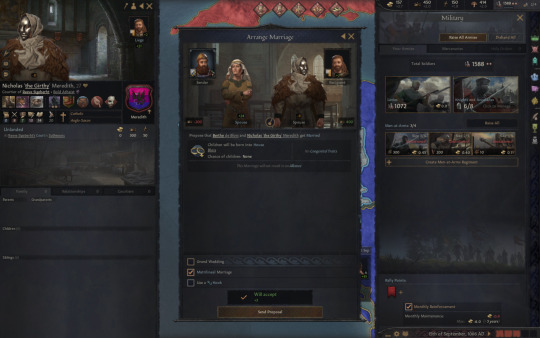

We begin a new play-through in 1066 as the Breton, Duke Konan mab Alan of Brittany of House Rennes whom we've played before in CK2, and whose starting situation is mostly the same barring some minor differences and changes. One of which is instead of being a Diplomacy-focused character, Duke Konan in CK3 is instead a Fortune Builder (Stewardship Level 3 education trait). He is Fickle, Content and Craven with middling stats across the board.

Duke Konan has an unlegitimised Bastard of a son named Alan mab Konan de Rennes who is Cynical and Rowdy who could be legitimised in future if he turns out to be any good. Speaking of Bastards, Duke Konan has a Bastard Half-Brother, Jafrez mab Alan de Rennes who also serves as his Knight.

Next, we have our Player Heir and Duke Konan's sister Countess Hawiz verch Alan of Cornouaille. We don't want the realm to fall to her because her kids are of a different House, in fact belonging to her husband - Count Hoel mab Judhael of Cornouaille of House Cornouaille, Duke Konan's Chancellor and Count of 2 counties within the Duchy of Brittany.

Moving on, Duke Konan's Mother, Berthe de Blois, a French lady who is still alive at 50 years of age. We quickly marry her to pull in a Knight named Nicholas 'the Girthy' Meredith who is a Disfigured Berserker.

Last but not least, we have Duke Konan's Uncle, Spymaster and Vassal, Count Edouarzh mab Jafrez of Penthievre who in CK2 usually is discontent and forms factions against Konan or organises hostile plots against Konan. Let's see if he is as unruly in CK3 as well.

1 note

·

View note

Text

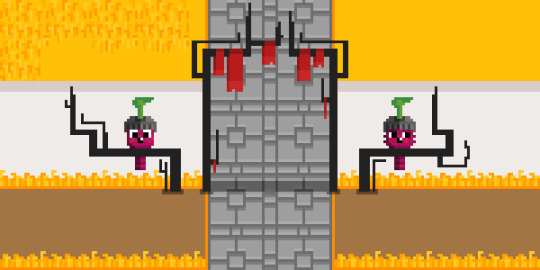

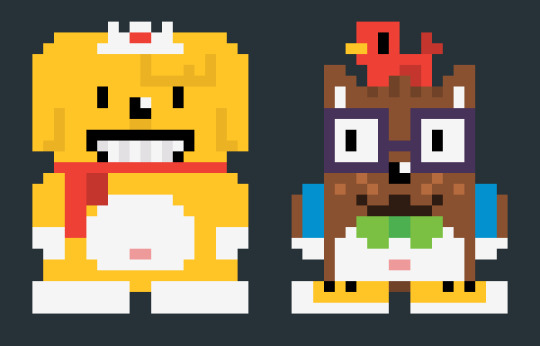

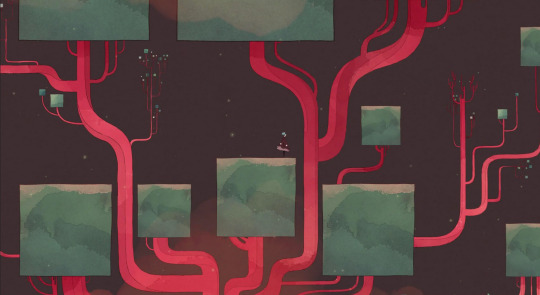

Some years ago I started to draw about a video game idea I had in mind. It was called "Hoari" in reference to the word "C'hoari" which simply means "game" in Breton (a language speaked in French Britanny). So I decided to dig up a bit into my files to show you what I did back then. I already showed some concept arts with the "Kiwiwis" and you can see two more of those creatures on the image below ⬇️

I had two protagonists : Oscar and huh... I don't think I ever gave a name to this yellow dog. Betty maybe ? 🐕 The story was starting with Oscar the otter finding a big yellow dog in an abandonned temple where she was traped since centuries and then they were both going on an adventure to make a lot of friends and find the truth about the world ! ✨ (something like that)

You maybe recognized the inspiration behind them : Shermy and Beth from the last episode of Adventure Time. This episode was amazing and seeing the future of Ooo inspired me a lot. I wanted to make this kind of goofy and impossible world full of mysteries where people are just vibing and living a lot of fun adventures. ⚔️