#Milton De Lugg

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

MEZZ MEZZROW, DE L’ÉCOLE DE RÉFORME AU SWING

Né le 9 novembre 1899 à Chicago, en Illinois, Milton Mesirow, dit Mezz Mezzrow, était issu d’une famille d’immigrants russes d’origine juive. Mezzrow a appris à jouer du saxophone à la Potomac Reformatory School où il a été incarcéré à partir de l’âge de seize ans pour avoir volé une automobile. Selon un de ses biographes, Mezzrow, avait fait de nombreux séjours dans les écoles de réforme et les prisons avant de découvrir le jazz et le blues à la fin de son adolescence. Trouvant une sorte de rédemption dans la musique, Mezzrow avait alors tenté d’imiter ses idoles Freddie Keppard, Joe Oliver, Louis Armstrong et Jimmy Noone.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

À la fois clarinettiste et saxophoniste ténor, Mezzrow avait enregistré à la fin des années 1920 avec les Jungle Kings, les Chicago Rhythm Kings et le groupe d’Eddie Condon. Il avait aussi joué avec un groupe appelé le Austin High Gang. En compagnie d’autres musiciens blancs comme Eddie Condon et Frank Teschemacher, Mezzrow s’était rendu au Sunset Café de Chicago où il avait pu entendre Louis Armstrong et son célèbre Hot Five. Mezzrow admirait tellement Armstrong qu’après la publication du classique "Heebie Jeebies", il avait parcouru la distance de 53 miles jusqu’en Indiana avec Teschemacher pour pouvoir jouer la pièce devant Bix Beiderbecke.

C’est en 1927 que Mezzrow s’était installé à New York et avait commencé à jouer avec Eddie Condon.

Dans les années 1930, Mezzrow avait joué avec différents groupes de swing aux côtés de grands noms du jazz comme Benny Carter et Teddy Wilson. Durant la même décennie, Mezzrow, qui avait contribué à briser la barrière raciale, avait également dirigé un groupe multi-ethnique appelé les The Disciples of Swing. Le groupe était notamment composé d’Eugene Cedric au saxophone ténor, de Mezzrow à la clarinette, de Frank Newton, Sydney De Paris, Max Kaminsky et Dolly Armendra à la trompette, de George Lugg et Vernon Brown au trombone, d’Elmer James au tuba, de John Nicolini au piano et de Zutty Singleton à la batterie. Durant une brève période, Mezzrow avait aussi été le gérant de Louis Armstrong.

Avec l’orchestre de Tommy Ladnier, Mezzrow avait aussi enregistré le thème musical qui l’avait fait connaître et intitulé “Really The Blues”.

Mezzrow a fait ses débuts sur disque en 1933 avec un groupe appelé Mezz Mezzrow And His Orchestra. La formation, qui était surtout composée de musiciens de couleur, comptait dans son alignement des grands noms du jazz comme Benny Carter, Teddy Wilson, Pops Foster et Willie "The Lion" Smith, mais comprenait également le trompettiste d’origine juive Max Kaminsky. Mezzrow a également participé à six enregistrements de Fats Waller en 1934.

Un des grands moments de la carrière de Mezzrow à cette époque avait été un enregistrement en 1938 organisé par le producteur français Hugh Panassie, qui était devenu un de ses grands amis et qui l’avait réuni à son idole Sidney Bechet. Tommy Ladnier participait également à l’enregistrement.

Grand admirateur de Bechet, Mezzrow avait fondé sa propre maison de disques appelée King Jazz, qui avait été en activité de 1945 à 1947 et qui lui avait permis d’enregistrer fréquemment avec Bechet au milieu des années 1940 ainsi qu’avec le trompettiste Oran "Hot Lips" Page. Même si Mezzrow était loin d’arriver à la cheville de Bechet, on doit lui accorder le mérite de s’être trouvé au bon endroit au bon moment, ce qui lui avait permis de participer à plusieurs enregistrements avec Bechet et d’autres grands noms du jazz, tant à New York qu’à Chicago de 1945 à 1947. Ces enregistrements, qui mettaient en vedette le Mezzrow-Bechet Quintet et le Mezzrow-Bechet Septet, mettaient à contribution des musiciens de couleur comme Frankie Newton, Sammy Price, Tommy Ladnier, Sid Catlett, ‘’Pleasant'' Joe ainsi qu’Art Hodes, un musicien blanc né en Ukraine.

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

Après avoir participé en 1948 au Festival de Jazz de Nice, Mezzrow s’est installé en France, où il s’était rapidement acquis le respect des musiciens de jazz locaux. Durant son séjour en France, Mezzrow avait fondé plusieurs groupes composés à la fois de musiciens français comme Claude Luter et de musiciens américains de passage comme Buck Clayton, Peanuts Holland, Jimmy Archey, Kansas Fields, Lee Collins et Lionel Hampton. Avec Clayton, un ancien trompettiste de l’orchestre de Count Basie, Mezzrow avait enregistré une version du classique "West End Blues" de Louis Armstrong en 1953.

Dans les années 1950, Mezzrow a continué d’enregistrer pour plusieurs compagnies de disques françaises.

Mezzrow est demeuré en France jusqu’à sa mort dans un hôpital américain de Paris le 2 août 1972. Il était âgé de soixante-treize ans. Le décès de Mezzrow a été attribué à une crise d’arthrite qui avait atteint sa moelle épinière. Mezzrow a été inhumé au cimetière du Père-Lachaise. À l’époque, l’épouse de Mezzrow, Johnnie Mae Mezzrow, était déjà décédée. On survécu à Mezzrow son fils Milton H. Mesirow, ainsi que ses deux frères domiciliés en Illinois.

Même si Mezzrow était d’origine et de religion juive, il avait épousé une afro-américaine, Johnnie Mae, qui était de religion baptiste. Le couple a eu un fils, Milton H. Mesirow, Jr. Au cours d’une entrevue qu’il avait accordée au New York Times en 2015, "Mezz Jr.", comme il était surnommé, avait déclaré qu’il avait toujours vécu entre deux cultures. Comme il l’avait souligné, "My father put me in a shul, and my mother's side tried to make me a Baptist. So when I'm asked what my religion is, I just say 'jazz.'"

Même si Mezzrow était un saxophoniste et un clarinettiste compétent, Mezzrow était surtout connu pour son autographie intitulée We Called It Music, qui avait été publiée à Londres en 1948. Même s’il était blanc, Mezzrow avait toujours admiré la culture afro-américaine. Dans son autobiographie, Mezzrow avait même catégoriquement rejeté la société blanche et revendiqué la culture afro-américaine. Dans son ouvrage, Mezzrow avait écrit qu’à partir du moment où il avait été mis en contact avec le jazz, il était devenu a ‘’Negro musician, hipping [telling] the world about the blues the way only Negroes can." Eddie Condon avait confirmé: "When he fell through the Mason–Dixon line he just kept going". Avec sa famille, Mezzrow vivait à Harlem. Se définissant lui-même comme ‘’Negro’’, Mezzrow était d’ailleurs décrit comme tel sur sa carte de mobilisation émise durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. L’autobiographie de Mezzrow, qui se concentre principalement sur les décennies de 1920 et 1930, malgré certaines inexactitudes historiques, constitue une des rares autobiographies écrites par un des premiers musiciens de jazz, tout en étant aussi une des mieux documentées et des plus divertissantes.

Grand consommateur de marijuana dont il faisait la promotion dans sa musique, Mezzrow était également reconnu comme ‘’dealer.’’ Surnommé ‘’Muggles King’’ (le mot Muggles étant un terme de slang désignant la marijuana), Mezzrow fournissait également de la marijuana à Louis Armstrong qui était un de ses meilleurs clients. La chanson de 1928 d’Armstrong intitulée "Muggles" fait d’ailleurs explicitement référence à Mezzrow. Dans une de ses lettres écrite en 1932, Armstrong précisait d’ailleurs comment et à quel endroit Mezzrow vendait de la marijuana.

En 1940, Mezzrow a été arrêté sous l’inculpation d’avoir été en possession de soixante joints de marijuana alors qu’il tentait d’entrer dans un club de jazz afin d’en faire le trafic. Au moment d’entrer dans sa cellule, Mezzrow avait informé les gardiens qu’il était noir et qu’il devait être envoyé dans la section réservée aux prisonniers de couleur. Dans son ouvrage Really the Blues, Mezzrow écrivait:

‘’Just as we were having our pictures taken for the rogues' gallery, along came Mr. Slattery the deputy and I nailed him and began to talk fast. 'Mr. Slattery,' I said, 'I'm colored, even if I don't look it, and I don't think I'd get along in the white blocks, and besides, there might be some friends of mine in Block Six and they'd keep me out of trouble'. Mr. Slattery jumped back, astounded, and studied my features real hard. He seemed a little relieved when he saw my nappy head. 'I guess we can arrange that,' he said. 'Well, well, so you're Mezzrow. I read about you in the papers long ago and I've been wondering when you'd get here. We need a good leader for our band and I think you're just the man for the job'. He slipped me a card with 'Block Six' written on it. I felt like I'd got a reprieve.’’

En 2015, un club de jazz a été nommé en l’honneur de Mezzrow à Greenwich Village. Le club était simplement baptisé ‘’Mezzrow.’’

Au cours de sa carrière, Mezzrow a enregistré environ 150 pièces et s’est produit vec les plus grands noms du jazz, de Sidney Bechet à Django Reinhardt, en passant par Frank Teschemacher, Eddie Condon, Tommy Ladnier, Max Kaminski, ‘’Hot Lips’’ Page, Buck Clayton, Lionel Hampton, Sid Catlett, Teddy Wilson, Fats Waller, Pops Foster, Benny Carter, Zutty Singleton, Jack Teagarden, Willie "The Lion" Smith et Memphis Slim.

Malgré le succès remporté par Mezzrow au cours de sa longue carrière, le producteur de disques Al Rose s’était montré plutôt sceptique face à son talent de clarinettiste. Rose avait cependant reconnu à Mezzrow le soutien qu’il avait accordé aux musiciens dans le besoin et avait souligné "his generosity and his total devotion to the music we call jazz." Dans son autobiographie, Mezzrow avait d’ailleurs admis avoir ‘’définitivement traversé la ligne qui séparait les identités blanches et de couleur.’’ Qualifiant Mezzrow de “Baron Munchausen du jazz”, le critique Nat Hentoff avait déclaré à son sujet qu’il avait joué “so consistently out of tune that he may have invented a new scale system.”

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

‘’Mezz Mezzrow.’’ Wikipedia, 2024.

‘’Mezz Mezzrow.’’ All About Jazz, 2024.

‘’Mezz Mezzrow, 73, Clarinetist Who Was a Titan of Jazz, Dead.’’ New York Times, 9 août 1972.

‘’Milton ‘’Mezz’’ Mezzrow.’’ The Syncopated Times, 2024.

‘’Mezz Mezzrow, 73, Clarinetist Who Was a Titan of Jazz, Dead.’’ New York Times, 9 août 1972.

1 note

·

View note

Text

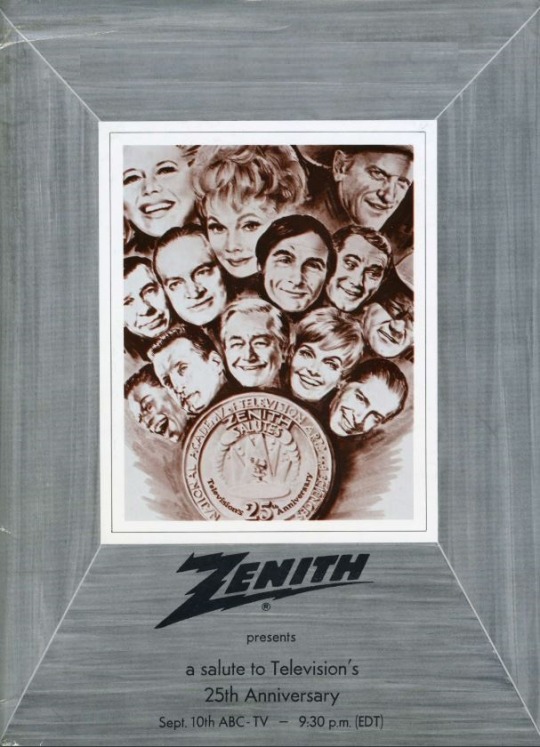

ZENITH PRESENTS: A SALUTE TO TELEVISION’S 25TH ANNIVERSARY

September 10, 1972

Produced & Directed by Marty Pasetta

Written by John Bradford, Lenny Weinrib, Bob Wells

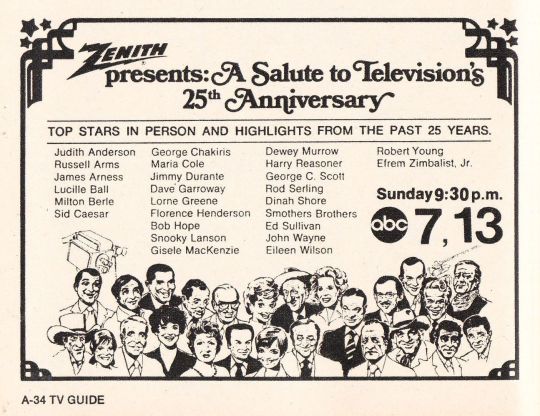

Cast (in alphabetical order)

Judith Anderson, honoree accepting for “Hallmark Hall of Fame”

Russell Arms, performer “Hit Parade”

James Arness, honoree accepting for “Gunsmoke”

Lucille Ball, honoree

Milton Berle, honoree

Sid Caesar, honoree

George Chakiris, performer “Westerns” / “Crime Drama”

Maria Cole, honoree on behalf of her late husband, Nat King Cole

Edward M. Davis, honoree accepting for Jack Webb and “Dragnet”

Jimmy Durante, performer / presenter “Music and Variety”

Dave Garroway, honoree and presenter

Lorne Greene, honoree accepting for “Bonanza”

Florence Henderson, performer “How Sweet it Was”

Bob Hope, honoree

Snooky Lanson, performer “Hit Parade”

Gisele MacKenzie, performer “Hit Parade”

Dewey Murrow, honoree accepting for his brother, Edward R. Murrow

Harry Reasoner, presenter “News”

George C. Scott, presenter “Drama”

Rod Serling, presenter

Dinah Shore, honoree

Tom & Dick Smothers, performers

Ed Sullivan, honoree

Eileen Wilson, performer “Hit Parade”

Robert Young, presenter “Opening” / “Closing”

John Wayne, presenter “Westerns”

Efrem Zimbalist Jr., presenter “Crime Drama”

Dick Tufeld, Announcer

This was a 90-minute special on ABC TV. It was taped August 9 to August 12 in Los Angeles. It featured clips from show’s from television’s past.

Zenith was co-founded in 1918 by Ralph Matthews and Karl Hassel as Chicago Radio Labs. The name "Zenith" came from ZN'th, a contraction of its founders' ham radio call sign, 9ZN. The Zenith Radio Company was formally incorporated in 1923. LG Electronics acquired a controlling share of Zenith in 1995, becoming a wholly owned subsidiary in 1999. Zenith was the inventor of subscription television and the modern remote control, and the first to develop High-definition television (HDTV) in North America.

In his diaries, singer Perry Como mentions jetting to Las Vegas to appear on the show, but he is not in the cast nor is he mentioned as an honoree.

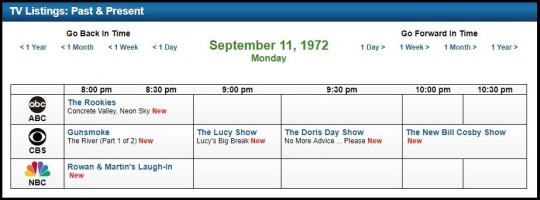

The next night, Monday, September 11, on CBS, “Here’s Lucy” presented its fifth season premiere “Lucy’s Big Break” (HL S5;E1).

“Here’s Lucy’s” lead-in was the 18th season premiere of “Gunsmoke” starring James Arness.

“Gunsmoke’s” competition on NBC was “Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In” which that night started its sixth season with guest star John Wayne. This is very ironic, considering that this Zenith special features a promo that John Wayne did for “Gunsmoke” when it first premiered in 1955!

This was a busy night for television, with the series premiere of “The Rookies” (1972-76) on ABC. At 10pm CBS also presented the premiere of “The New Bill Cosby Show,” which lasted just one season.

The show begins with a boy named John Joyce (played by uncredited actors of various ages) who grew up watching television.

After the opening credits, Florence Henderson performs the seven-minute opening number “How Sweet It Was,” surrounded by dancers. The original song was written by Jack Elliott, Bob Wells and John Bradford. In a section devoted to children's shows, the dancers perform “The Mickey Mouse Club” theme, dressed in mouse ears and sweaters with names on them.

Robert Young (”Marcus Welby”) takes the stage to explain that the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences is also 25 years old and will be honoring a select group of people and programs who have made an impact, had popularity, proved longevity, and demonstrated substance. The recognition award is a silver medallion on a plaque.

A montage of clips from news footage of the Berlin Airlift, the Israeli War, the first Political Convention on TV, and the Kefauver Hearings, and the McCarthy Hearings, follows.

Young pays tribute to television's early comedians with clips of such comics as Jimmy Durante, Martin and Lewis, “The Honeymooners,” and and ending with clips from “Texaco Star Theatre” starring Milton Berle wearing various outrageous costumes.Berle is the first recipient of the medallion. He enters to thank the audience and briefly talk about his type of comedy. Berle claims to have done 641 hours of live television!

Berle closes by introducing a clip from “Your Show of Shows” starring Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca as figures on a Bavarian clock. Caesar takes the stage to thank the Academy for the medallion. His remarks are humble and brief.

After a commercial for Zenith Super Chromacolor, there is a tribute to TV dramas with a montage of clips from anthology shows like “The Alcoa Hour,” “Dupont Show of the Week,” “Westinghouse Studio One,” “The U.S. Steel Hour,” “Playhouse 90,” “Hallmark Hall of Fame,” “Goodyear Playhouse,” “Producer's Showcase,” and “Net Playhouse.” The clips feature actors like Robert Preston, Andy Griffith, Jackie Gleason, and Paul Newman.

George C. Scott enters to talk about the contributions of “The Hallmark Hall of Fame.” Clips from the show feature actors like Charlton Heston, Peter Ustinov, George C. Scott, and Dame Judith Anderson, who accepts a medallion on behalf of the show.

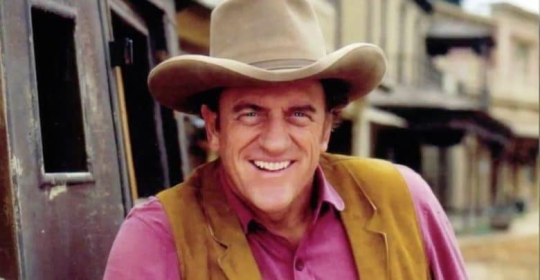

A salute to TV Westerns begins with a stylized Old West town with a handsome stranger (George Chakiris), riding into town on a white horse. Entering the saloon, he plays cards with a man in black, listens to Lily the dance hall girl, and then gets into a shoot out where (naturally) he is the only one left standing.

After the sketch, John Wayne introduces clips from westerns like “The Lone Ranger,” “Cheyenne, ” “Bonanza,” and “Gunsmoke.” James Arness, who played Marshall Dillon on “Gunsmoke,” joins Wayne onstage to receive a medallion on behalf of the show.

Lorne Greene then accepts a medallion on behalf of “Bonanza.”

A salute to TV crime dramas begins with a stylized city street with a handsome stranger (George Chakiris again), riding into town in a white sports car. The scenario deliberately mirrors the previous one for westerns. Entering the bar, he listens to Sally the burlesque dancer, and gets into a shoot out with a man in black where (naturally) he is the only one left standing.

After the sketch, Efrem Zimalist Jr. (“The F.B.I.”) introduces some ‘fast moving scenes’ from crime shows like “Hawaii Five-O” and (oddly) “Batman.” Zimbalist pays tribute to Jack Webb and the series “Dragnet.” Accepting the medallion on behalf of Webb is Los Angeles Police Commissioner Edward M. Davis.

Dave Garroway (“Today”) tells us that there are 121 recipients of the silver anniversary medallion, and that there is no way a 90-minute program can adequately pay tribute them all. Behind him is a scroll of names and clips from the honorees, including Lucille Ball and “The Desilu Playhouse.” Interestingly, for the sake of continuity, all the clips are in black and white, even if a show was aired in color.

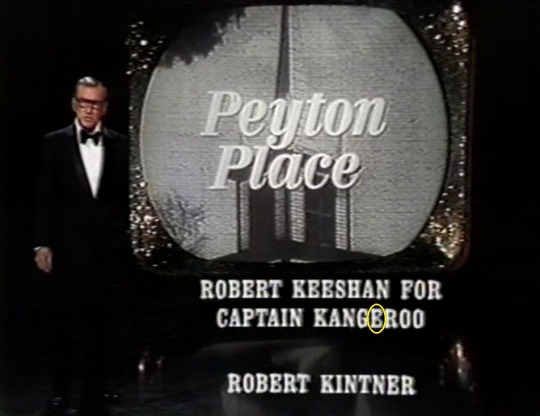

Oops! The list of honorees mis-spells “Captain Kangaroo” as “Captain Kangeroo.”

The Smothers Brothers, Tom and Dick, talk about television, although Tom has trouble not mentioning its many flaws, despite Dick's attempt to keep things positive.

Harry Reasoner talks about television news and tributes Edward R. Murrow. Clips consist of Murrow interviewing such figures as Castro, Marilyn Monroe, and John F. Kennedy. Murrow died in 1965, so his brother Dewey Murrow accepts the medallion on his behalf.

Leading off a tribute to music on television is presented in the style of “Your Hit Parade”:

#5 - “Shrimp Boats” sung by Eileen Wilson. It was written in 1951 by Paul Mason Howard and Paul Weston.

#3 - “(Why Did I Tell You I Was Going To) Shanghai” sung by Russell Arms. It was written in 1951 by Bob Hilliard and Milton De Lugg.

Extra - “Love is Sweeping the Country” performed by the Hit Parade Dancers. It was written by George and Ira Gershwin for the 1931 musical Of Thee I Sing.

#2 - “(How Much is That) Doggie in the Window?” sung by Giselle MacKenzie (above). It was written by Bob Merrill in 1952.

#1 - “This Ole House” sung by Snooky Lanson. It was written by Stuart Hamblen in 1954.

Curiously, there is no #4, perhaps for time limitations or because there are only four alumni of “Your Hit Parade” in the show.

Closing the section, the group sings “So Long for a While,” the closing song of “Your Hit Parade” written by Hy Zaret.

Jimmy Durante enters at the end of the sequence to tribute Music and Variety on television. It begins with a montage that features Steve Allen, Liberace, Durante, Edgar Bergen, and Dinah Shore, who is the next honoree. Dinah talks about her work on “The Chevy Show.”

Dinah Shore: “We were live and our main motivation was fear!”

Shore then tributes the late Nat King Cole, and introduces Maria Cole, his widow. “The Nat King Cole Show” (1956) was the first television show starring a black man.

Durante returns and sings “September Song” by Kurt Weill and Maxwell Anderson for the 1938 musical Knickerbocker Holiday.

After a commercial, Rod Serling (“The Twilight Zone”) presents a medallion to 'Mr. Sunday Night' Ed Sullivan. Clips from “Toast of the Town” (aka “The Ed Sullivan Show”) feature Julie Andrews, the Beatles, Rocky Marciano, and President Eisenhower.

When Ed Sullivan enters to accept his medallion, it is apparent that he is not on the same stage with Serling, but has been inserted into the shot using special effects. When Serling hands him the award, the camera switches to a close-up to avoid the transfer.

Serling also presents medallions to Lucille Ball and Bob Hope. A brief montage of clips from “I Love Lucy” and various Bob Hope specials follows. It includes scenes from “The Audition” (ILL S1;E6), “The Operetta” (ILL S2;E5), “Lucy Meets Harpo Marx” (ILL S4;E28). Interestingly, there are no clips of the two performing together.

Once again, it is apparent that Serling is not on the same stage as Lucy and Bob, despite the fact that they address him as if he were there standing beside him. This time there is no special effect to imply they are together. Hope calls him the “spooky writer” and Lucy refers to Serling's voice on “headache commercials.” Hope and Ball exchange some friendly banter based on their age:

Lucy: “I just love watching 'The Late, Late Show'. Where else could I be 25 for 25 years?" Bob: “On your reruns. You know I'm kidding, Lucy. You're the most beautiful woman in Hollywood and you have been for many years.” Lucy: “That's quite a compliment considering you started as a stuntman for Francis X. Bushman.”

The show closes with the singers and dancers reprising “How Sweet It Was” and Robert Young returning to sum up television's progress and promise for the future. This time the clips behind him are in color. A montage of 'good nights' from various television shows plays under the credits.

This Date in Lucy History ~ September 10

“Lucy and Danny Thomas” (HL S6;E1) ~ September 10, 1974

#Zenith#Lucille Ball#Bob Hope#Here's Lucy#Danny Thomas#A Salute to Television's First 25 Years#Judith Anderson#Hallmark Hall of Fame#Robert Young#Russell Arms#Your Hit Parade#James Arness#Bonanza#Gunsmoke#Milton Berle#Texaco Star Theatre#George Chakiris#Sid Caesar#Your Show of Shows#I Love Lucy#Maria Cole#Nat King Cole#Dinah Shore#The Chevy Show#Edward M. Davis#Jimmy Durante#September Song#Dave Garroway#Lorne Greene#Florence Henderson

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

irritatingly-terrible theme from a ridiculously-tacky movie

0 notes