#Mick Salgado

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

mick schumacher arrives to the track on race day, mexico - october 29, 2023 📷 luis e salgado / imago

#mick schumacher#f1#formula 1#mexican gp 2023#fic ref#fic ref 2023#mexico#mexico 2023#mexico 2023 sunday

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

🖊️ BALLPOINT PEN — does your oc have any tattoos? do they want any (more) tattoos? & ❤️ RED HEART — what are three of your oc's positive traits? & 🍦 SOFT ICE CREAM — what is/are your oc's favorite ice cream flavor(s)? & 💯 HUNDRED POINTS SYMBOL — share three random facts about your oc that others may not know. (jack)

details about ocs: jack ackerman.

🖊️ BALLPOINT PEN — does your oc have any tattoos? do they want any (more) tattoos?

sim. ao todo, tem quatro: uma na panturrilha direita, que inicialmente seria só com as ondas, mas acabou perdendo uma aposta pra irmã e ela decidiu que teria que colocar o sol junto (debochando que seria pra ele ser mais positivo); uma no tornozelo esquerdo (a menor que ele tem), que é o ano de nascimento da clary (nessa fonte) e é uma combinação com que ela tem no tornozelo direito (que fizeram no aniversário de vinte e um dela, e ele jura de pés juntos que foi obrigado mas não foi); uma na parte de baixo do abdômen, que é um raio pequeno; uma na parte de dentro do braço (na mesma fonte e no mesmo lugar da outra tatuagem do link anterior), escrita memento (feita quando fez dezoito anos com uma parcial motivação de irritar o pai, que odiava tatuagens), o que era em parte pelo significado de 'an object kept as a reminder or souvenir of a person or event'. não tem planos no momento de fazer mais, mas nunca se sabe.

❤️ RED HEART — what are three of your oc's positive traits?

sinceridade: seja pelo bem ou pelo mal, o jack é extremamente sincero. o máximo de mentiras que ele conta é quando não quer admitir que alguma coisa incomodou ele de verdade, ou que tá magoado, porém, é mais uma questão de esconder que contar mentiras. especialmente porque ele odeia mentiras, e prefere acabar correndo algum risco de ser mal interpretado que sentir que tá enganando alguém.

lealdade: é extremamente leal às pessoas que ama, e não gosta de deixar ninguém na mão. assume as brigas e problemas dos amigos e da irmã como se fossem dele e, mesmo se souber que a pessoa provavelmente tá errada, vai assumir o b.o junto pra não deixar a pessoa sem apoio (e já se meteu em várias discussões por conta disso, pra defender outras pessoas - não que ele precise de muito pra entrar em discussão, né). por isso mesmo, quebra de confiança é algo tão complicado pra ele.

determinação: quando o jack coloca alguma coisa na cabeça, ele não desiste. algumas vezes acaba sendo algo ruim por influência da teimosia? sim, mas não é a regra. esse lado se aplica em todas as áreas da vida dele, até, por exemplo, quando fica completamente focado em arrumar o encontro ou o presente perfeito pra mick.

🍦 SOFT ICE CREAM — what is/are your oc's favorite ice cream flavor(s)?

como em tudo, jack tem fortes opiniões sobre sabores de sorvete, e vai estar sempre pronto pra julgar quem estiver comendo um sorvete de menta com chocolate ou de pistache no mesmo lugar que ele. já os favoritos dele são o rocky road, o morango e o caramelo salgado.

💯 HUNDRED POINTS SYMBOL — share three random facts about your oc that others may not know.

seu pai queria que ele fizesse medicina, o que jack nem considerou. ao avisar aos dois que iria cursar direito na faculdade (o mesmo curso que a mãe fez), teve de aturar o pai jogando indiretas aqui e ali por algumas semanas, porque, de algum jeito, até a escolha de curso dos filhos era uma competição para o ex-casal. jack nem deu bola (e danielle achou hilário ver seu ex-marido se doendo), e depois de um tempo vincent superou.

o jack tem um lado meio nerd. ele sempre assiste aos filmes de super-heróis que saem (gosta mais da dc, mas se falar disso perto dele vai fazer ele reclamar pelos filmes serem uma desorganização péssima por mais de meia hora) e colecionava alguns quadrinhos quando era mais novo. e, quando era criança, se fantasiou de batman por dois anos seguidos. e, embora ele jogue na reta dos amigos (fazido), gosta muito de jogar videogame/jogos battle royale no computador.

ele tem um conhecimento estranhamente específico sobre alguns realities. diferente de filmes de comédia romântica (que, como já dito na 006, se viu provavelmente alguma ex da vida mostrou), esse conhecimento na verdade vem da irmã do henry. depois que os dois ficaram amigos e se aproximaram muito rápido, ele pegou costume de ficar bastante lá até quando tava nas férias da faculdade, e criou muita proximidade com os irmãos dele também. a cecilia é como uma segunda irmã mais nova pra ele, e é viciada em reality shows de teor duvidoso. então, os dois já assistiram muita coisa com ela - o que explica o jack saber opinar sobre programas tipo love island.

#aproveitando pra postar rapidinho#partner: winter.#in character: answers.#character: jack ackerman.#bend verse.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Mick > Bryan - "Ay, Cuddlemonster. Er... where do you think your violence comes from? Aside from me calling you 'Cuddlemonster'."

Bryan > Mick - Bryan growls deep in his chest and clenches his fists.

“What the fuck man, fuck off. I grew up with a drug dealer for a dad, what the fuck do you think!?”

4 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

me: i love this band

someone 30-40 years older than me: they've been around for awhile you just getting into them?

me: why didn't you prevent vietnam?

539K notes

·

View notes

Text

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, ZAC & MICK SALGADO!

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

@wanderersofthewastelandsocs @pitifulmagicalocs

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

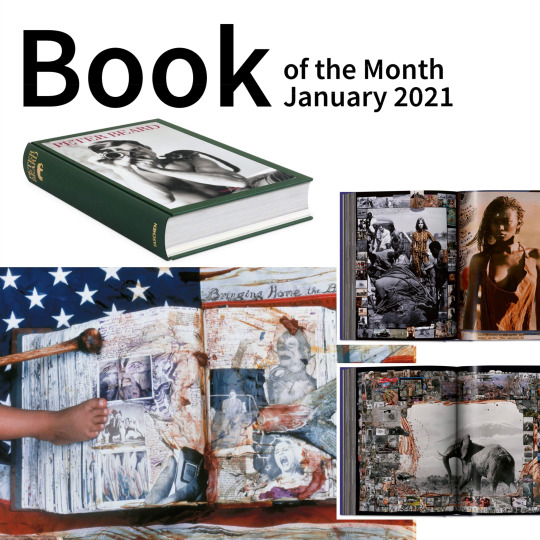

Book of the month / 2021 / 01 January

I love books. Even though I hardly read any. Because my library is more like a collection of tomes, coffee-table books, limited editions... in short: books in which not "only" the content counts, but also the editorial performance, the presentation, the curating of the topic - the book as a total work of art itself.

Peter Beard

Peter Beard

Photography & Art / 2013 / Taschen publishing house

In the early 1960s, Africa was a country largely unknown to Western societies. Despite the colonial past of large parts of the continent, there was no tourist infrastructure whatsoever, and in the sub-Saharan zone there was hardly any socio-political stability to speak of. In other words: a dream for adventurers and individualists!

Peter Beard was born in New York City in 1938 and began taking photographs as a young man. Coming from a well-off family, he could afford to study art with Joseph Albers at Yale University. As a member of New York's high society, he was friends with Truman Capote and Bianca Jagger, for example, and worked artistically with Andy Warhol and Salvador Dali, photographing fashion for Vogue and celebrities such as David Bowie and Francis Bacon on the side. His passion for photography was joined in 1961 by a passion for Africa - the combination of the two was to become his life's mission.

In 1961 Beard came to Kenya for the first time, met the Danish author and country expert Tania Blixen and bought a piece of land next to hers. He witnessed the population explosion in Kenya, which also meant the end of many resources and the threat to many animal species. The mass deaths of some 35,000 elephants in Tsavo National Park, which perished because they could no longer find enough food when pressed by humans, were formative for him. And he had his camera with him.

Beard had already written a diary in his youth. While "written" is not quite right, collage is more accurate, a style he now combined with photography. He used his photographs as a canvas, arranged contact sheets, newspaper clippings, postcards, and other collected objects, and embellished them with handwriting and typewriting, illustrating them with drawings and even animal blood. In this way, his life on the African continent became a synthesis of the arts: a mixture of photography, environmental activism and diary, which was published in exhibitions and books all over the world.

In doing so, Beard does not accuse, he simply lets the images work, combining beauty and cruelty. In his photographs, haute couture models feed giraffes under the Kenyan sun, and elephant carcasses bear witness to man's destruction of nature. Thus, a personal life became an artistic life's work, he takes the viewer on an adventure trip into his own world, which is so far from the spirit of the time of the ideal exotic destination. His pictures "tell of a life that was almost too big, almost too much for one individual" (GQ).

Over the years, my favorite publisher Taschen has developed a penchant for discovering the world in a slightly different way: from fantastic travel picture books to compilations from National Geographic's infinite archive to exclusive works by Sebastiao Salgado. It goes without saying that Peter Beard is a must-have. The 770-page tome with the name of the "author" as its title is my favorite, as it spans the entire life of the artist.

Although set pieces had long been known and loved, this collection struck anew, and the feuilleton was enthusiastic:

"An impressive monograph and an excellent opportunity to learn about and appreciate the full range of Peter Beard's remarkable life and work." (State Magazine, London)

"This XXL volume is the ultimate work on the oeuvre of this artist of the century." (Foto Magazine, Hamburg)

"This extravagant and excellent book is itself a work of art." (L'Express, Paris)

"Sprawling is Peter Beard's world of thought, one that cares for no boundaries, opening up a mythical realm, set between Soho and Savannah. A book in which one can and will lose oneself." (ORF, Vienna)

"The rush of images on the pages quickly draws you into (...) a world in which Mick Jagger and Andy Warhol belong just as much as the animal life of the Savannah, world politics, supermodel eroticism and painting. Big was this world, exciting and glamorous. It is equal parts pop art and Hemingway romance." (Süddeutsche Zeitung, Munich)

Beard's pictorial power is matched by a creative editorial team that explains, classifies, and comments. In addition to his Kenyan wife Nejma, they are gallery owner David Fahey, authors Owen Edwards and Steven M. L. Aronson, and art director Ruth Ansel. It's an academic setting that should be curiously abhorrent to the artist himself, who says, "My whole life has been about escaping art academy. Art academy teaches you exactly the opposite of art. I'm not a person who suffers from that. I'm just of the opinion that you should just do things and try them without giving them a lot of thought beforehand."

Peter Beard would have had his birthday the day before yesterday, but passed away last April: he was found dead at Camp Hero State Park, a nature preserve near Montauk, after having been missing for three weeks. So, in a way, he remained true to himself and his adventurous spirit to the very end.

Here is the link to Peter Beard's website:

https://peterbeard.com

#book#book review#coffee table book#peter beard#taschen#africa#Tania blixen#elephant#extinction#Kenya#photography#collage#visual diary#adventure#new york city

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Denial (Mick Jackson, 2016).

#denial (2016)#mick jackson#justine wright#haris zambarloukos#andrew mcalpine#david hare#deborah lipstadt#auschwitz#sesión de madrugada#sesiondemadrugada#movie stills#movie frames#diego salgado#denial#david irving

48 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

therapist: why do you laugh when you say anything negative about yourself

me: cos honestly its hilarious how incompetent i am

373K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Queer California: Untold Stories April 13–August 11, 2019 at the Oakland Museum of California Image: Brown Rainbow Eclipse Explosion, 2017, Young Joon Kwak. Photo: Ruben Diaz @pingpongpaw , courtesy @commonwealthandcouncil Work by artists and collaborators including Absolute Empress III Shirley, Chloe Aftel, Laura Aguilar, Tina Valentin Aguirre, D-L Alvarez, Steven Arnold, Gilbert Baker, Lisa Ben, Andrea Bowers, Kaucyila Brooke, Ginger Brooks-Takahashi, Craig Calderwood, Pat Campano, Monica Canilao, Tammy Rae Carland, Cassils, Jerome Caja, Willy Chavarria, Kate Clark, Torreya Cummings, Amanda Curreri, Cyclona, Cecil Davis, Reed Erickson, Rhys Ernst, Edie Fake, Eve Fowler, William P. Gaddis Jr., Clay Geerdes, Rick Gerharter, James Gobel, Nicki Green, James Gruber, Barbara Hammer, Mick Hicks, William E. Jones, Lenn Keller, Joseph Richard Kapps, Young Joon Kwak, Vero Majano, DJ Brown Amy (Amy Martinez), Jaguar Mary, Helen Nestor, Yetunde Olagbaju, Kari Orvik, Frances Reid, Augie Robles, Peaches, Grace Rosario Perkins, Marlon Riggs, Nica Ross, Julio Salgado, Helen “Sanders” Sandoz, Jose Sarria, Patrick Staff, Chuck Stallard, Eric A. Stanley, A.L. Steiner, Elizabeth Stevens, Sylvester, Tina Takemoto, Xara Thustra, Wu Tsang, Chris E. Vargas, Lex Vaughn, Travis Y., and Cathy Zheutlin. Additional participants include L. Frank, Joseph Byron Jones, Miss Major, Toshio Meronek, Deborah A. Miranda, Donovan Nation, Kenny Ray Ramos, Kanyon Sayers-Roods, Kayla Strickland, and Karen Vigneault. Contributing archives include The American Philosophical Society; The Archives of the Archdiocese of San Francisco (AASF); Bay Area Lesbian Archives; California State Archives; The Collections of the Kinsey Institute, Indiana University; The Digital Transgender Archive; The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Historical Society; Lambda Archives; The Lesbian Herstory Archives; ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries; San Francisco Public Library; James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center; The UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center; and Willard Library. Curated by Christina Linden @hotcorners (at Oakland Museum of California) https://www.instagram.com/p/BviSLVrl1Lf/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=nb5az71pdl0l

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus Lagoa do Salgados Portugal 19/10/19 from Mick Sway https://ift.tt/35JMAP0

0 notes

Photo

David Bailey ‘Taschen’ is launching a monster 440-page retrospective of the work of British photographer David Bailey. Measuring 50 x 70cm this "Sumo" edition weighs a back-breaking 30kg – and it is so heavy that it comes with its own custom-designed three-legged table so that buyers can actually turn the pages without hurting themselves. Now aged 81, Bailey became one of the most famous fashion and portrait photographers when still in his twenties during the swinging sixties. He is still a highly-sought after and active photographer, running his studio in central London – not far from where he was born. Bailey's book which is simply called ‘David Bailey’ is a who's who of the rich and famous over the six decades of his career. The 300-plus black and white portraits, mainly shot against his signature white background, include iconic portraits of Mick Jagger, the Kray twins, The Beatles, Andy Warhol, Margaret Thatcher, Jack Nicholson and Her Majesty the Queen. The signed limited-edition book costs £2,250 ($3,000) and went on sale in April. Each of the 3,000 books is numbered – with the first 300 selling with signed prints at an even higher asking price. The first 75 of these which comes with a portrait of Lennon and McCartney cost £11,250 ($15,000) and have already sold out. The book can be ordered direct from Taschen. Three other photographers have previously had Sumo editions published by ‘Taschen’: ‘Sebastiao Salgado', ‘Annie Liebowitz’ and ‘Helmut Newton’. #neonurchin #neonurchinblog #dedicatedtothethingswelove #suzyurchin #ollyurchin #art #music #photography #fashion #film #words #pictures #neon #urchin #davidbailey #bailey #photographer #portraiture #blackandwhite #book #sumo #limitededition #taschen #marcnewson https://www.instagram.com/p/BzhwnxCABm5/?igshid=1r0a0lpk3j7ox

#neonurchin#neonurchinblog#dedicatedtothethingswelove#suzyurchin#ollyurchin#art#music#photography#fashion#film#words#pictures#neon#urchin#davidbailey#bailey#photographer#portraiture#blackandwhite#book#sumo#limitededition#taschen#marcnewson

0 notes

Photo

Queer California: Untold Stories

April 13 – August 11, 2019

Oakland Museum of California

Work by artists and collaborators including Absolute Empress III Shirley, Chloe Aftel, Laura Aguilar, Tina Valentin Aguirre, D-L Alvarez, Steven Arnold, Gilbert Baker, Lisa Ben, Andrea Bowers, Kaucyila Brooke, Ginger Brooks-Takahashi, Craig Calderwood, Pat Campano, Monica Canilao, Tammy Rae Carland, Cassils, Jerome Caja, Willy Chavarria, Kate Clark, Torreya Cummings, Amanda Curreri, Cyclona, Cecil Davis, Reed Erickson, Rhys Ernst, Edie Fake, Eve Fowler, William P. Gaddis Jr., Clay Geerdes, Rick Gerharter, James Gobel, Nicki Green, James Gruber, Barbara Hammer, Mick Hicks, William E. Jones, Lenn Keller, Joseph Richard Kapps, Young Joon Kwak, Vero Majano, DJ Brown Amy (Amy Martinez), Jaguar Mary, Helen Nestor, Yetunde Olagbaju, Kari Orvik, Frances Reid, Augie Robles, Peaches, Grace Rosario Perkins, Marlon Riggs, Nica Ross, Julio Salgado, Helen “Sanders” Sandoz, Jose Sarria, Patrick Staff, Chuck Stallard, Eric A. Stanley, A.L. Steiner, Elizabeth Stevens, Sylvester, Tina Takemoto, Xara Thustra, Wu Tsang, Chris E. Vargas/MOTHA, Lex Vaughn, Travis Y., and Cathy Zheutlin.

Additional participants include L. Frank, Joseph Byron Jones, Miss Major, Toshio Meronek, Deborah A. Miranda, Donovan Nation, Kenny Ray Ramos, Kanyon Sayers-Roods, Kayla Strickland, and Karen Vigneault.

Contributing archives include The American Philosophical Society; The Archives of the Archdiocese of San Francisco (AASF); Bay Area Lesbian Archives; California State Archives; The Collections of the Kinsey Institute, Indiana University; The Digital Transgender Archive; The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Historical Society; Lambda Archives; The Lesbian Herstory Archives; ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries; San Francisco Public Library; James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center; The UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center; and Willard Library.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hyperallergic: Arto Lindsay Remembers Hélio Oiticica

Hélio Oiticica in front of a poster for Neil Simon’s play “The Prisoner of Second Avenue,” in Midtown Manhattan, 1972 (© César and Claudio Oiticica)

Arto Lindsay, musician, artist, member of DNA and The Ambitious Lovers, is a singular voice in culture. He has collaborated with numerous artists over the past four decades, including Vito Acconci, Laurie Anderson, Animal Collective, Matthew Barney, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Caetano Veloso and Rirkrit Tiravanija. He also knew the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica, whose retrospective Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium, is currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Lindsay lived for many years of his childhood with his missionary parents in Brazil, where he gained a deep appreciation of Brazilian culture as well as Tropicália (Tropicalism), an artistic movement, especially in music, that merged Brazilian styles with cross-cultural influences, such as African rhythms.

In To Organize Delirium, Lindsay’s voice can be heard over headsets as he reads several of Oiticica’s writings from his years living in New York City, from 1970-1978. This fall, Lindsay will carry out a series of events at the Whitney in conjunction with the retrospective in a project called Myth Astray.

* * *

Cora Fisher: I’m a huge admirer of Oiticica’s work. I saw the Cosmococas when I was a teenager and my mind was blown. And now there’s this show at the Whitney, To Organize Delirium, and I thought it would be such a nice chance to reconnect with you and get a first-hand account of his work and life. How and where did you meet him?

Arto Lindsay: I met Hélio through a guy called Waly Salomão, a Brazilian poet and lyricist who lived in New York. By chance we became roommates. Waly was a close friend of Hélio’s. Through Hélio I met other Brazilian artists and intellectuals who were coming through New York, including the filmmaker Julio Bressane; Neville de Almeida, the guy who did the Cosmocacas with Hélio; and Ivan Cardoso, another filmmaker. I grew up in Brazil and I was surrounded by Brazilian popular culture, which was full of all kinds of artistic information. This was particularly true of Tropicalism, but I didn’t really realize the implications of it when I was a teenager. But as soon as I moved to the States from Brazil I started digging into this stuff and learning more about it.

Hélio was a completely fascinating guy. I got a chance to hang out with him a bit. He actually came to an early DNA show. To a young guy newly arrived in New York, the way that Hélio lived was really interesting. He took his Nests and installed them where he lived. These were inhabitable sculptures that were first shown in the US in the exhibition Information in 1970 at the Museum of Modern Art. When I knew him he lived on Christopher Street and he had reinstalled these Nests in this small apartment. He always had lots happening at the same time: the TV on, a record playing, the radio on and he was often on the phone while talking to whoever he was with — this constant buzz.

Miguel Rio Branco, “Babylonests” (1971), digital projection, dimensions variable (courtesy César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro)

I remember he was taking these pictures of Ivan Cardoso’s girlfriend Helena. They were beautiful photographs, slides, lit the way those photos of young boys in his bed were. And he was also working on maquettes for public sculptures, one of which was eventually built at Inhotim, which is a big art park in Brazil. It’s a mining magnate’s collection of art with pavilions dedicated to specific artists. Inhotim is, as we say in Portuguese, pharoaonic. Matthew Barney, Dominique Gonzalez Forrester, Adriana Vareijao, Miguel Rio Branco, Rivanne Neuenschwander Anish Kapoor, Tunga. All these artists and others have individual pavilions. And these are all out in the middle of the countryside set off from each other by wild vegetation or ornate gardens. Bernardo Paz, who built and owns Inhotim, was close to modernist landscape designer Burle Marx and he collected plants before he collected art. Inhotim built one of sculptures that I saw Hélio planning, with geometric slabs, maybe ten feet tall, colored slabs of concrete. There is also a pavilion with several of his Cosmococas.

I was trying hard to learn as much as I could about art history at that point and trying to fit together his really abstract work, his performances and what we now call installations. I heard that he was a Samba dancer, that he had learned how to samba as an adult and that the other Samba people took him seriously. And gradually I got some notion of his trajectory, where he started and where he ended up.

During the 90s he was such a big deal here in Brazil, before he was discovered outside of Brazil and before he was given the importance that he eventually was given. He was a huge influence on several generations that came after him, in terms of investigating the fact of being Brazilian, in terms of audience participation, of a different way of seeing art and life and how they can connect to each other. Of course there is a kind of basic 20th century idea about the connection between art and life, but he had his own really strong take on that. He was such an interesting theorizer — not exactly theoretician — he was constantly writing stuff, both manifesto style and critically about his own work.

Last night actually Hélio would’ve been 80.

CF: It’s special that he would’ve been 80 yesterday. So when you were in New York in the 70s did you feel that his work was connected to other downtown artists at the time, or did you see him occupying his own cosmology?

AL: I really felt that he was an extremely contemporary artist. I started college in 1970 and I was really excited by reading about Vito Acconci, Yvonne Rainer, and a whole generation of people. I got a chance to see some of it in New York when I first moved up. I didn’t really think of him as being distinctly different. Obviously, he was Brazilian, but it just seemed like people put themselves into their work. It didn’t strike me as being of a different strain. He had a close relationship with music. The musical movement called Tropicalism was named after one of his environments. Musicians Caetano [Veloso] and [Gilberto] Gil, who didn’t know his work heard about him when somebody said, “Hey, you should call your movement this.” And they said, “I don’t think so, we shouldn’t take somebody’s name, somebody’s title.” But then a journalist started to call their work by that name and it took off.

One of Hélio’s best-known aphorisms is — O que faço é music/What I make is music.

Installation view of “Tropicália, 1966-67,” plants, sand, birds, poems by Roberta Camila Salgado on bricks, tiles and vinyl squares. Collection of César and Claudio Oiticica (photo by Matt Casarella)

CF: From what I gather, Tropicalism is something both super-authentic, representing the counterculture of a certain period, and also kind of kitschy at the same time. Can you speak to what Tropicalism might have meant for Hélio as a Brazilian living in New York?

AL: I think he was trying to counter the way that Brazil was exoticized. And the musical Tropicalists were super-aware of Brazil having been exoticized and at the same time they were kind of reclaiming the right to the territory that was considered kitschy by other people. The Carmen Miranda image had been sold all over the world but it was rejected in Brazil. The Tropicalists were saying, “But there’s so much good that’s good there.” At the time there was a really strong cultural lobby, a leftist anti-imperialist lobby that identified culture from outside of Brazil as a form of imperialism. Basically, it was a back-to-the-roots movement by a bunch of white kids enshrining Samba from black people in the favelas or folk music from northeastern Brazil as the only possible authentic Brazilian music.

This wasn’t coming from musicians themselves, this was coming from the politically correct Leftist student movement, which of course, was the main vehicle of resistance and it had plenty going for it, but did have this culturally oppressive attitude. The Tropicalists deliberately went against that, and eventually Hélio did too, though he started from a different place. He became quite close to Caetano and to Gil. And he was a music freak. He was completely in love with Mick Jagger. There were always…two sides to Hélio’s thinking and living: the hyper-rational and then this idea of the Dionysian, the Nietzschean, which was so important to the Brazilian counterculture.

Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida, “CC5 Hendrix-War” (1973), installation view, Walker Arts Center, Minneapolis, 2010 – 2011, slide series, hammocks, and soundtrack. César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro and Neville D’Almeida (© César and Claudio Oiticica, and Neville D’Almeida)

Also Hélio was gay, and coming from a traditional Brazilian background this wasn’t easy. Being involved in the favelas and Samba was a revelation. It was a big deal for him in many ways, including sexually. I think that for him to come to the States was a relief. Remember that at the time New York and San Francisco still were the only places in the States with openly gay communities. People came from all over to the West Village; there was that strongly specific economy there. I think it was really important to him.

CF: What else stood out to you about Hélio’s experience of New York?

AL: I know that he was really interested in some of the Warhol Superstars. It’s important to remember where these ‘60s and ‘70s guys came from, what they had to make their way through to become who they became, and what they saw around them as being culturally significant. Apparently to Hélio, drag queen superstars seem to have been the most meaningful thing about Warhol. To those of us who lived on the Lower East Side, they were truly emblematic figures; these super-loud, super-aggressive Puerto Rican drag queens really ruled. They represented a kind of freedom and beauty and a kind of boundary-pushing to me and to my friends, too.

You know that really beautiful photo — I don’t know if it’s in the show — of Hélio painting Waly’s face an unbelievably bright red? That picture’s actually taken by Eduardo Viveiro de Castro, who’s an important anthropologist. South American Indian Cosmology is his thing. He happened to be really good friends with Ivan Cardoso, and Hélio was in some of Ivan’s movies, and de Castro ended up taking these great pictures of Hélio at that time.

Hélio sold work when he lived in Brazil but when he lived in New York he didn’t make any money from his art at all. He was always talking about leaving the art world and not being interested in it anymore and finding different ways to make his work. He was trying to find some kind of crease or some kind of place between art and life.

Hélio Oiticica, “P15 Parangolé Cape 11, I Embody Revolt (P15 Parangolé Capa 11, Eu Incorporo a Revolta)” worn by Nildo of Mangueira, 1967 (courtesy César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro. © César and Claudio Oiticica. Photo by Claudio Oiticica)

CF: I loved that the show gives some insight into his New York period. There’s this amazing photograph of Hélio and Romero on the subway and they’re putting on the Parangolés [Oiticica’s wearable fabric artworks] and other people start jumping in. There’s something so inclusive and amazing about that moment in terms of that connection between art and life. In Brazil he was going to the favelas, learning Samba and that texture of his work really comes out in the Parangolés. For me those pieces are some of the most exhilarating because they come alive. It’s the dance and the Samba and the accidental meeting on the street.

Were Oiticica’s Parangolés important to you? I think about the parades that you’ve been organizing….

AL: Absolutely. Maybe in a different way. Even back in DNA, I wanted to make something that could work in more than one way at once, as opposed to kind of meshing into a third transcendent form. It’s more about going back and forth between music and art, performance and poetry, art and life, I guess. When we made DNA, I really thought you could look at DNA the way you could look at a piece by Yvonne Rainer or a performance by an artist: gesture, rhythm, confrontation. You could see a kind of structure up against a totally unstructured or spontaneous or organic behavior. You could set up all kinds of conflict.

CF: It’s helpful to hear you talk about music and art not as binary or dialectical or transcendent but polyvalent, androgynous — offering many different outcomes. This openness that Hélio had, how does it relate to Brazilian class-consciousness?

AL: There’s two ways you can look at it. One way is you can say it’s a result of the possibilities presented by a post-slavery culture. When you have a lot of people with a lot of time on their hands, whose labor isn’t worth hardly anything to them, then the ways they find to express themselves in this oppressive situation give rise to this openness. You can see this as a result of the way things are in Brazil. Or, you can look at it the other way and you can say that this is an attempt to inject spontaneity and a more direct relation to physicality into a hide bound, bourgeois, white upper-class culture. So you have both things. That’s the nature of Brazil — and I guess you could say of a lot of places — that oppressive conditions give rise to transforming cultural practices. They require them! And Brazil is such a paradoxical place. It’s got its own set of behaviors that came about because of, or in opposition to, these awful conditions. Famously, Brazilians get along. They’re warm. They’re friendly, as opposed to South Africans or North Americans No legal segregation. No apartheid. But they’re equally racist. It’s just two ways of dealing with the same thing — being absolutely rigid about something or pretending it’s not happening. Obviously the United States and Brazil are so similar and so different in the way they deal with this legacy of slavery.

Installation view of “Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium” (2017), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. From left to right: Nests, 1969-74; Topázion-flor dedicated to Haroldo de Campos, March 20, 1975 (photo by Ron Amstutz)

CF: So let’s talk a little bit about the text you were reading in the exhibition. What was it and did it strike you as musical? Was it exciting?

AL: Hélio’s writing is super-interesting in the way that he can shift quickly from theoretical writing to a rant. There’s got to be a great campy word for this kind of rant… telling people off and making a performance of what you’re saying. He could shift beautifully from inaugurating a new art form to railing against some other artist that he thinks is a fool or getting all excited about Mick Jagger as his — and the world’s — object of desire. So, there’s that in his writing.

There’s one thing about Hélio’s writing that always strikes me as similar to Vito Acconci’s and that of other artists from the ‘60s: they’re not really manifestos but they’re written in the style of manifestos. Every text kind of establishes a new point of view, defines new terms. And this is completely out of fashion, by the way. Most artists now use language in a way that’s completely different. It’s tough to get that flavor, and Hélio’s work still really attracts me. I like that kind of freshness.

You know Hélio was close to the Brazilian Concrete poets and the notion of the visuality of language and how to deal with that was super-current in the ‘50s and ‘60s, from the Concrete poets to Brion Gysin to William Burroughs to Carl Andre, Vito Acconci, and Lawrence Weiner. You can think of a million things. Some of the things I read [in the exhibition] were from these notebooks of his. Words are splayed out across the page; there might be a drawing in the midst of the writing. Mallarmé was important to the Concrete poets in how you arrange the words on the page.

CF: Do you think his writing had to do with, not only the Modernist history of Concrete poetry, but also this new buzzing information — you said you went into his apartment and there would be the radio on and the TV and 10 things going at once — that lent itself to a kind of free association?

AL: Yeah, it was kind of like a proto-internet: a buzz of information.

CF: So did you find revisiting Hélio’s texts and his work inspiring in a new way?

AL: I did. Of course I noticed some of the tics of the period. Very post-Joyce, very portmanteau, where you build these giant words out of various words, there’s a lot of that in there. That’s something that I wish would come back into fashion. And I really enjoyed the descriptions of cocaine because there’s so much humor there. Hélio was really funny as a person. He had this kind of Vincent Price laugh, very self-consciously pseudo-evil. He used to really enjoy it. He obviously knew he was a very brilliant and complex guy. There is an often overlooked, delicate side to his work, too.

In the early ‘90s I visited an apartment in Rio where all his work was stored. A close friend of his called Luciano Figueiredo took care of the work when nobody cared or gave it any value because he wasn’t really a marketable artist. Later, I visited the Hélio Oiticica Foundation, which Rio set up and where the estate was housed for a while. I got a chance to look at flat files full of his stuff, none of it behind glass. That’s when I really started to understand his work. I was always struck by how psychedelic some of the early geometric work was. At the time, Brazilian geometric art was influenced by [Victor] Vassarely, who was considered cheesy in Europe and the United States. There was an oddly Op art flavor to it. But in Brazil there was no such filter. Or there were different filters. And this was before Hélio got high. It was just from the way he got so deep into the materials and ideas he was working on.

Installation view of “Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium” (2017), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (photo by Matt Casarella)

And I particularly love the Bolides, which are sculptures with pigment that he made himself. I love that they’re perishable. He made these things out of wood and pigment and hardware store materials. There was no notion of them lasting forever and I think that’s important. And I think people don’t emphasize that enough. To make something that will rot is a statement.

CF: But there is a notion of preservation now.

AL: That’s always been there. And that’s cool, it’s important. Different approaches.

Hélio Oiticica, “B11 Box Bólide 9 (B11 Bólide caixa 9)” at Rua Engenheiro Alfredo Duarte, Rio de Janeiro, 1964, oil with polyvinyl acetate emulsion on wood and glass, pigment, 19 5/8 x 19 11/16 x 13 3/8 inches, Tate, London; purchased with assistance from the American Fund for the Tate Gallery, Tate Members and the Art Fund, 1970 (photo by Desdémone Bardin)

CF: What do you think is the most fragile aspect of Oiticica’s work? And what do you think is the most durable?

AL: Well I would say that the most durable is maybe the most ephemeral in the sense that it’s about behavior, fitting our body up to these ideas. I don’t know what I would say the most fragile is. I guess to be really historically specific when you try to understand them, like his famous installations, long before people made installations. I remember people looking at his work and saying, “Well, Marcel Broodthaers did that.” And I’m like, “Yes and no.” It’s not really the same thing; it’s not really the same idea. Tropicália, it has such an edge. When you go inside those shack structures you see something really dark and sad, like a TV between channels, you know it was meant as a repudiation of the way people understood Brazil. At the same time, it’s kind of an endorsement of the shacks’ open, almost casual, asymmetrical, hand-built architecture.

I still don’t know what I would say is the most fragile aspect. His work is super-romantic, as is all of Modernism. Homage to Cara-de-Cavalo (1965), which is in the show, contains a photograph of a guy he knew, a guy who was killed by the police. It says, “Seja Marginal Sea Heroi” — “Be Marginal, Be a Hero.” Marginal in Brazil means outside the law. So there’s that aspect which is so easily misunderstood. It’s similar to our fascination with the Red Army Faction in the ‘70s, with the terrorists. It’s romanticism taken to an indefensible conclusion.

CF: So the fragility may be most keenly felt in the historical context?

AL: I guess. I don’t really have a good answer for that because right now it seems so strong and necessary. Some of the art/life stuff maybe seems simplistic in hindsight, because he kind of just harped on it, proclaimed it. He didn’t really have a chance to go further with it because he died. An early death is certainly one kind of fragility.

The post Arto Lindsay Remembers Hélio Oiticica appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2wFZQ6r via IFTTT

0 notes