#Michael Huemer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Having feelings does not make you irrational. Believing that the world must be a certain way because of your feelings does.

— Michael Huemer

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Michael Huemer / Free Black Thought

Published: Oct 14, 2024

Editors’ note: This is an excerpt from Michael Huemer’s new book, Progressive Myths.

The Myth

Many unarmed black people are shot by American police every year. Blacks are regularly killed by police due to racism.

Examples of the Myth

It is hard to find published sources that directly state the first part of the myth, concerning unarmed black men, though there are many sources that devote extensive attention to police shootings of unarmed black men while ignoring victims from other races.

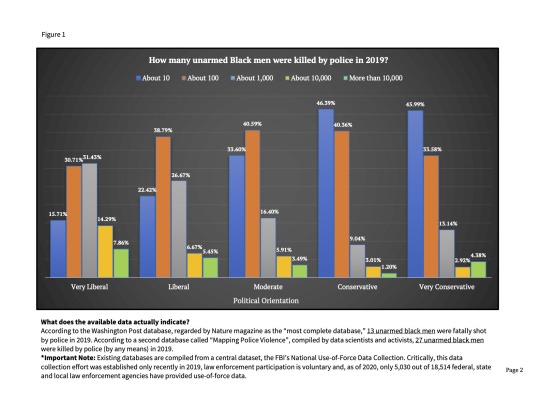

In 2021, Skeptic magazine published survey results indicating people’s answers to the following questions:

Q1: “If you had to guess, how many unarmed Black men were killed by police in 2019?” (Available answers: About 10, about 100, about 1000, about 10,000, more than 10,000.)

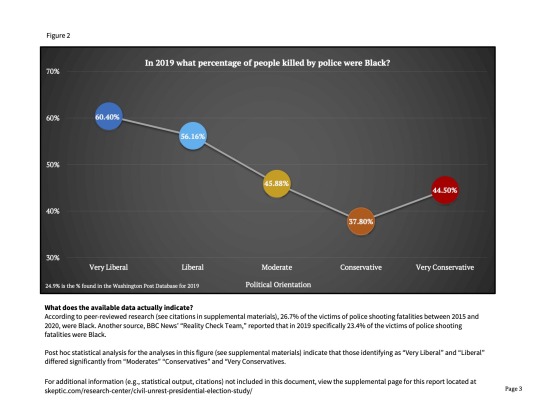

Q2: “If you had to guess, in 2019 what percentage of people killed by police were Black?” (Respondents could choose any number from 0 to 100.)

In answer to Q1, 29% of people answered “about 1,000” or more (1,000: 19%; 10,000: 6%; over 10,000: 4%). In answer to Q2, the average estimate was 48%. (See further here.)

This doesn’t tell the whole story, though. The answers differed greatly by political orientation. Respondents who self-identified as “liberal” or “very liberal” were much less accurate than moderates or conservatives. Among liberal or very liberal respondents, nearly half (46%) thought that the number of unarmed black men killed by police was about 1,000 or more. This same group on average estimated that 58% of people killed by police were black.

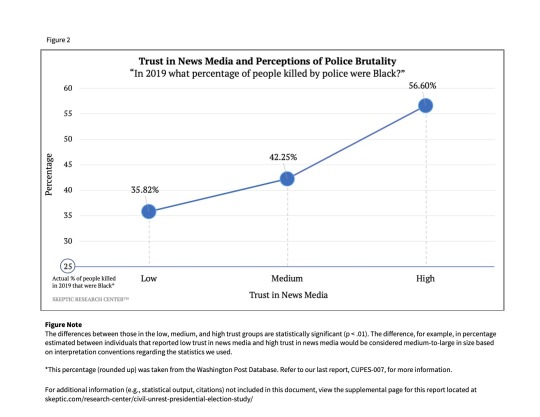

Misconceptions were correlated with trust in the media—people who reported greater trust in the media were more misinformed about police shootings. This may be because media sources give misleading impressions about this particular issue. Alternately, it may be because “racist police shootings are a huge problem” and “the mainstream media are trustworthy” both have independent appeal to liberals.

Concerning the second part of the myth, that police killings show racial bias: The main argument for this is that a higher percentage of the people killed by the police are black than the percentage of the general population who are black:

Police disproportionately shoot and kill black Americans … black Americans were twice as likely to be shot and killed by police officers, compared with their representation in the population. —ABC News

Black people, who account for 13 percent of the U.S. population, accounted for 27 percent of those fatally shot and killed by police in 2021…. That means Black people are twice as likely as white people to be shot and killed by police officers. —NBC News

In 2013, three radical Black organizers—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi—created a Black-centered political-movement-building project called #BlackLivesMatter in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, George Zimmerman. […] We are working for a world where Black lives are no longer systematically targeted for demise. —Black Lives Matter website

Reality

There is evidence that American police are unnecessarily violent. However, that is not my topic here. My topic here is whether police violence shows a widespread racial bias.

1. How often are unarmed black people killed by police?

Start with the number of unarmed black people killed by police. Again, half of liberal respondents estimated this at 1,000 or more for 2019. The correct figure was 36. (The total number of blacks killed by police in that year was 286, of whom just 36 were unarmed, 32 men and 4 women.) In the same year, police killed 54 unarmed white people (46 men and 8 women).

Does this still represent a major problem? Bear in mind that this was in a country of 330 million, which included 47 million blacks. It would not be shocking if, of 47 million black people, a total of 36, despite being unarmed, did something sufficiently threatening to cause them to be killed by police. In any case, the risk of this happening to a given black person is extremely small; they are literally more likely to be struck by lightning.1

2. The racial disproportion

Let’s turn to the total numbers of blacks and other Americans (whether armed or unarmed) killed by police. The statistics in the quotes above are accurate, based on the best available data: Blacks comprise about an eighth of the population but a quarter of the police shooting victims. Hence, you are more likely to be shot if black than otherwise. Does this indicate racism?

Consider another, even more shocking disproportion: Males make up only 50% of the population but 95.5% of the police shooting victims. Men are thus twenty-one times more likely to be shot by police than women. One could claim that this indicates an extraordinary degree of sexism, many times worse than the racism shown by police departments.

But most of us would reject this inference. To determine whether the shooting statistics indicate sexism, we must first consider such things as: How often do police make contact with male suspects? How often do men commit violent crimes, compared to women? How often do men commit violence against police officers, compared to women? Those questions would be relevant because they are proxies for the tendency of men to engage in threatening behavior toward police of the sort that could plausibly lead to a violent police response even in the absence of sexism. As it turns out, about 88% of all murderers and nearly all cop-killers are men. In 2013-14, for example, there were 66 men who killed police officers and one woman who aided her husband in killing a pair of police officers.

This would undercut the narrative of anti-male bias among police. Police may well be killing too many men, but we cannot infer sexism, since the gender disparity can as well be explained by greater numbers of aggressive male suspects as compared to females.

An exactly parallel point applies to the racial disparity. To assess the amount of racial bias, we need to consider such things as number of police contacts, violent crime rates, and rates of violence against police officers.

Begin with numbers of police contacts. Usually, when police make contact with a suspect, this is because a member of the community has called the police to report some apparent criminal behavior. These community members usually give a description of a suspect whom they believe to be committing or about to commit a crime. As it turns out, the racial composition of the group of suspects reported to the police by members of the community matches the racial composition of people shot by the police, leaving no evidence of racial bias on the part of the police.

You could hypothesize that racism by members of the community causes them to disproportionately report black people to the police. But the simpler explanation is that the higher rates at which black individuals are reported to the police are due to the higher crime rates by black individuals.

Apropos of that, recall that, per the quotations above, blacks comprise about 13% of the U.S. population but 27% of police shooting victims. However, blacks also comprise about 40% of murderers in the U.S., and 43% of cop-killers. Therefore, just as in the case of the gender disparity, the racial disparity in police shootings could plausibly be explained by a disparity in threatening behavior. It’s still possible that racism plays a role, just as it’s still possible that sexism plays a role, but the statistics give us no reason to posit racism or sexism. If anything, the statistics suggest a pro-black bias by police, since the rate at which blacks are shot by police is disproportionately low compared to the rate at which black people kill police officers.

3. Experimental evidence

The above sort of evidence has limitations. The database of homicides committed by the police does not have information about all the aspects of suspects and their behavior that may have influenced a decision to use lethal force. In brief, one cannot tell how threateningly each suspect was behaving.

Experimental evidence may address this shortcoming, since a laboratory experiment can control essentially all plausibly relevant factors other than race. This was the task of Lois James et al.’s (2016) study, which observed police behavior in simulators of the sort used during police training. The simulations involve video enactments, using actors, of the sorts of scenarios that police often encounter that have a risk of leading to a shooting. Sometimes, the suspect in the video pulls a gun and shoots at the camera; other times, the suspect pulls out an innocuous object such as a wallet. As the scenario unfolds, officers must decide whether and when to draw their guns and shoot at the suspect in the video. For the experiment, officers were equipped with Glock 22’s (like those used in many police departments), modified to emit infrared light rather than shooting real bullets, to detect when and where officers had shot.

Researchers prepared two versions of each of several scenarios: a version using a white actor, and a version using a black actor with everything else held the same. The purpose was to test whether officers would be quicker to shoot at black suspects.

This sort of experiment admittedly has its own limitations. Since officers know that they are not in any genuine danger, they may not react in the same way that they would in real life (even though they were instructed to do so). Nevertheless, the simulations were highly realistic, subjects showed signs of immersion, and simulations of this kind are widely taken to be the best way of preparing for real-world encounters. If officers were quicker to shoot black suspects in the simulations, progressive commentators would surely be quick to cite this as powerful evidence of racism, and rightly so.

In fact, the reverse turned out to be the case. In the scenarios in which the suspect pulls a gun, officers took 1.1 seconds to shoot if the suspect was white, and 1.3 seconds if the suspect was black. In scenarios in which the suspect pulls out a harmless object, officers wrongly shot the suspect 14% of the time if the suspect was white, and only 1% of the time if the suspect was black. This dovetails with the other evidence cited above for a pro-black or anti-white bias in police shootings.

Objections

1. How could there possibly be an anti-white bias in police shootings? That’s ridiculous.

Reply: The most likely explanation is an effect of media coverage and public attention. In recent years, enormous attention has focused on shootings of black suspects, which causes problems for the police department and the individual officers involved. By contrast, the other three quarters of police shootings, which are of non-black suspects, receive almost no attention. Thus, police officers are much more reluctant to shoot black suspects than suspects of other races.

This is supported by the statements of actual police officers. In 2015, a white Birmingham police detective was attacked by a black suspect, pistol whipped with his own gun, and left unconscious and bleeding on the ground while the suspect drove away. The detective later explained that the suspect was able to do this in part because the detective had hesitated to use force. “A lot of officers are being too cautious because of what’s going on in the media,” he said. “I hesitated because I didn’t want to be in the media like I am right now.” Another cop in the same police department explained that police are “walking on eggshells because of how they’re scrutinized in the media.”

Perhaps this is as it should be—if you could be deterred from using deadly force against someone by fear of your actions’ being scrutinized, then you probably should not use deadly force against that person. Granted, this entails some risk to officers, as the above case illustrates. But perhaps the risk to officers is worth it to reduce the risk of unnecessarily killing civilians.

In that case, the problem is that the media don’t scrutinize shootings of white, Asian, Hispanic, or other non-black suspects. Fewer people would probably be killed if they did.

2. This doesn’t address all other forms of racial bias in policing or the justice system.

Reply: That’s right, it doesn’t. The above discussion is only about homicides by police. This is worth addressing because it is the most momentous action taken by police or the justice system, as well as the most discussed. This issue was the cause of the protests and riots in many American cities in the last few years.

The hypothesis cited in reply to Objection 1 is consistent with the possibility that other aspects of the justice system show more racial bias, since they are much less scrutinized by the media and the public. If police rough up a suspect on the street, or a judge hands out an overly harsh punishment, there will normally be no public scrutiny. This is also consistent with Roland Fryer’s well-known (2019) study, which found that police are more likely to use nonlethal force against minority members than against whites, but not more likely to use lethal force. An obvious explanation for the difference in nonlethal force is that police officers engage in racial profiling.

Michael Huemer is a professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He is the author of more than eighty academic articles in epistemology, ethics, metaethics, metaphysics, and political philosophy, as well as about twelve amazing books that you should immediately buy. Check out his website and his Substack, Fake Noûs. Buy Progressive Myths on Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

--

1 - 400-500 Americans are struck by lightning per year, and 79% of the fatalities are among men. I don’t have lightning strike statistics by race, but assuming that lightning is race neutral, the average black person’s risk of being struck should be about 1.3×10-6, while their probability of being unarmed and shot by police is about 7.7×10-7. For black men, the probability of a lightning strike is probably about 2.2×10-6 (given that men are about four times more likely to be struck than women), while the probability of being shot by police while unarmed is about 1.5×10-6 (32 out of 22 million black men).

==

[ Source: The Washington Post ]

It should be noted that "unarmed" is not the same as "not dangerous." Someone who tries to run an officer down with a car or goes for the officer's gun is classified as "unarmed."

From Skeptic's study:

It's worth noting a second element of Skeptic's study which found that respondents with higher trust in news media were far more misinformed about police shootings compared to the reality.

You don't hate legacy media enough. You think you do, but you don't.

If you're comfortable describing tenets of religious faith that violate demonstrable reality as mythology, you should be equally comfortable describing tenets of ideological faith that violate demonstrable reality as mythology.

#Free Black Thought#Michael Huemer#Progressive Myths#mythology#police shooting#religion is a mental illness

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Say I go to the doctor. "Doctor," I say, "I think I have arthritis." The doctor asks, "Why do you believe you have arthritis?" Now, that is a completely reasonable question to ask; I need a reason to think I have arthritis. So I give my reason: "Because I'm feeling a pain in my wrist." And now suppose the doctor responds, "And why do you believe that you're feeling pain?" - Michael Huemer, Knowledge, Reality, and Value

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#Cognitive Typology#Vultology#Proactive#Fluid#Measured#Suspended#ENTP#Drake Bell#PewDiePie#Bill Wurtz#Bret McKenzie#Michael Huemer#Lights#Christina Perri#Eliza Dushku#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

For a different tack, I think the clunkers things is relevant because your initial claim about the debate was based on said 'clunkers'

I don't think so? Both Caplan and deBoer were posting at something around their usual strength in those debates - I didn't notice them doing particularly badly relative to their average. Conversely, neither Scott nor Huemer seemed particularly strong. That was the thing that prompted me to post - these flattenings weren't tours de force, they were just the ordinary, day-to-day output of those two people; it was the casualness that impressed me.

My point would be I personally have little reason to think that - based on the topic, DeBoer or Scott would be more or less likely to win.

Ok, then I strongly disagree. There's such a thing as a class difference - as I'm sure deBoer would be the first to agree, hah! - and the good middleweight does not beat the good heavyweight outside of a massive upset.

you can imagine a triangle [SA > FdB > NS > SA]

I can indeed imagine it, I just don't think it's very likely to happen.

There's a certain class of public intellectual - the two examples I have in mind are Bryan Caplan and Freddie deBoer, who otherwise have very little in common - who is genuinely quite smart and articulate, and able to defend their positions against almost everyone they debate with (including other people smart and articulate enough to be serious public intellectuals), and who therefore come across as being Well Up There in the human tiers. And then, every so often, whether from hubris or just sheer bad luck - they'll go up against someone with Serious Brainpower and they will get absolutely fucking smashed. Bryan Caplan tried to critique Huemer's book and came out of it looking a lot like the coyote after his own steamroller has squashed him flat; FdB had the very bad luck to post about EA a few hours before the sage Alexander did, which perhaps made his post come to Scott's attention in a way it otherwise wouldn't, and a day later there was a SlateStarCodex post that took FdB's position apart entirely, thoroughly, and without visible effort.

It's like watching, say, the Romanians in WWII going up against late-war Russians: These armies are visibly roughly the same thing, they both have tanks and machine guns and a reasonably up-to-date officer corps, it's not like bolt-action rifles against spears and shields. (That would be a normie trying to argue with the likes of Caplan.) And nonetheless one of these armies is about to cease to exist as a serious military organisation.

And nonetheless both bloggers are multiple tiers removed from the average human! I will give Caplan the win against everyone he's ever debated except Huemer and Alexander; and of course most of those people are still people literate enough to actually come to his attention, far beyond any possible effort of a normie Reddit poster; and even Reddit posters (in politics discussions, that is) are (generally) at least capable of reading a few hundred words and posting some moderately grammatical sentences in tangentially-relevant response, putting them easily in the top 50% of humans.

I get kind of used to reading Scott Alexander (quite aside from anything else, he just posts a lot!) and that makes it easy to forget just how much of a mutant superman he really is. And then you watch fairly heavyweight writers like FdB get casually flattened, and you go "Oh, right... born under a red sun."

#meta-discourse#this is a scott alexander fanblog#but not particularly a michael huemer fanblog so I don't think that's biasing my tier assertions

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are libertarian scholars shills and useful idiots for the rich?

Are libertarian scholars shills and useful idiots for the interests of the rich? Many people are saying this. My take:

Big financial interests, such as Koch funding, are responsible for some growing hazards to the integrity and quality of some academic professions such as philosophy. My own academic philosophy department (BGSU) received Koch funding several years ago, which has been a catalyst for endless insanely complex controversies.

There is some scholarly work which is bad or flawed, but which financial interests cause to either (A) wrongly come into existence in the first place, or (B) attain a degree of high status and influence disproportionate to its objective value.

This adds to an already considerable pile of non-value-tracking biases which wrongly influence the status of many scholarly works—such as the Matthew Effect, various careerist biases, barriers to access stemming from systemic oppressions such as classism, ableism, sexism, racism, and transphobia, as well as social trend feedback cycles (e.g. many philosophers write about X because a bunch of *other* philosophers are writing about it, even if X’s objective importance is questionable), and the fact that many philosophers believe X or work on X because their department mentors or peers do, etc.

As one possible example: Why are there so many capitalist libertarian philosophers? Sometimes philosophers disproportionately support a minority viewpoint because the viewpoint has serious intellectual merit which the general public irrationally fails to recognize. For instance, I think there are a lot of philosophers who support ethical vegetarianism because the arguments for ethical vegetarianism are objectively very strong-- despite widespread popular disagreement by people who irrationally fail to recognize the strength of the case for vegetarianism. Is libertarianism like this? No, I think it is questionable whether libertarianism is objectively strong enough to merit this degree of philosopher support on intellectual grounds.

On the one hand, I think a lot of libertarian scholars have done good work—often they have noticed many flaws in popular and scholarly pro-redistribution (and pro-regulation) arguments, and a lot of them have made important contributions to critiquing drug prohibition, immigration restrictions, and anti-sex-work laws, and they’ve advocated for Universal Basic Income. Sometimes they have noticed evidence for significant downsides to economic and business regulations, which progressives ignored. Robert Nozick, Michael Huemer, and other right-libertarians have shown that redistributionist arguments tend to be sloppy and badly oversimplified. Bleeding heart libertarians of the Steiner-Vallentyne school have made powerful contributions to the case for Universal Basic Income and other good ideas, and have built on the legacy of classical liberalism e.g. by exploring the implications of the "Lockean proviso" (which sets limits on traditional capitalist assumptions). Many progressives have failed to give credit to the diversity and sophistication of the capitalist libertarian tradition.

Rightwing and leftwing capitalist libertarians have also inspired progressive scholars such as GA Cohen (analytical Marxist) to develop improved arguments for redistribution. I want to give serious credit for this, similarly to how I give some gender critical feminists serious credit (despite the evils of their ideas) for inspiring trans rights advocates to improve their arguments for pro-trans advocacy.

On the other hand, libertarianism is a weird and sectarian school of thought, in some ways quite fringe, with a strong connection to insane beliefs like “taxation is wrongful theft.” In fact, it is very obvious that the horrors of poverty are much more severe and vastly more important than the mild badness of stealing from the rich.

...No, seriously, give me a break. Why does the stupid contrary view hold so much influence despite its being manifestly stupid? Overall, stealing from the rich to give to the poor is blatantly good, cool, and based. Who could disagree?

It is highly plausible that libertarianism is so high-profile in large part because a lot of rich people see it as supporting their interests.

Now, are all libertarian ideas pro-rich? Are they all anti-poor? No, that is a common uncharitable misperception. Some libertarian scholars, even some right-libertarians, have been at pains to show that many of their ideas would support the poor and not the rich. I think libertarians support a cluster of policies--some of which would benefit the rich, and some of which would harm the rich.

If libertarians were to win totally (i.e. make all their policy ideas into a reality), it might or might not overall benefit the rich, and it may even harm them—such as by allowing more small businesses to fairly compete in the market, and by ending government subsidies (corporate welfare) for (or deals with) vicious and mass murderous industries like coal companies, the war profiteering industry, the various prison profiteering industries, some surveillance industries, and animal factory farms.

Total libertarianism would also plausibly benefit the poor in many ways, such as by drastically curtailing the power of police over marginalized poor people, cutting off support to various prison industries, combating conservative and progressive forms of puritanism and paternalism, and ending the terror of deportation and associated abuses that hang over the heads of many migrants. It may also end some forms of day-to-day terror against homeless people, sex workers, and some other groups.

However, this may depend on how much power it hands to big business, and on how much of an interest big businesses have in screwing over marginalized people. Such matters could be highly context-sensitive. For instance, some "hostile architecture" (e.g anti-homeless spikes on places to potentially rest in public) are created by private industry, some by government. If libertarianism wins, will there be more or fewer anti-homeless spikes than before? Well, I don't know. Still, there is a good chance that libertarian polices would overall help the poor a lot.

There is also the problem of many, many high-profile libertarian crackpots—such as Walter Block (of the Mises Institute) who has argued in favor of legalizing workplace sexual assault, and Murray Rothbard who has argued in favor of legalizing the right of parents to starve their children to death (although his views on adoption rights may complicate this reading of his view).

Moreover, many lay non-scholarly libertarians are also insane crackpots, such as the “Mises Caucus” people who have apparently taken over the US Libertarian Party (although most libertarian scholars condemn them). The one anarcho-capitalist who has gained power, Javier Milei, is also probably a crackpot who seems on track to reinforce authoritarianism e.g. by strengthening the power of police to crack down on protestors (despite this move’s obvious incompatibility with libertarian principles). Such issues present a serious black mark on the record of libertarianism as a movement, and strengthen the case for thinking that libertarianism as a movement is unable to improve the world (despite the fact that many individual libertarians have good intentions and actively promote good ideas).

Nevertheless, many libertarians are immensely more principled and clear-cut in their stances on immigration, drugs, and sex work than are many liberals and progressives, and they should be praised for this. For instance, many libertarians explicitly support open borders, while many liberals waffle on whether to condemn the Biden administration’s treatment of immigrants. There may also be some underappreciated convergence between libertarians and leftists in critiquing the corporate capture of government. For instance, I wonder if there’s room for more cooperation between Marxian ideological critics and public choice theorists.

All that said, plausibly some rich people see the advocacy of libertarianism as overall beneficial to themselves and their financial interests in actual practice—perhaps because they think that libertarians tend to succeed in implementing their helpful-to-the-rich ideas but fail to implement their harmful-to-the-rich ideas. This may explain why rich people tend to support libertarianism. And there may be some evidence for this combination of trends.

For instance, over the last few decades, libertarians & libertarian-adjacent scholars (such as Milton Friedman) succeeded in advocating some kinds of big business deregulation, tax cuts for the rich, and welfare-cuts (which helped the rich and hurt the poor), but failed in their advocacy of open immigration, medication patent reform (to lower drug prices), residential zoning reform (to lower housing prices), and the legalization of drugs and sex work—all of which would help the poor, and harm at least some of the rich, helping fewer of the rich. Much of this combination of libertarian success and libertarian failure constitutes what is commonly called "neoliberalism," which in practice consistently benefits (most of) the rich while hurting (at least many of) the poor.

Many of the global poor have also benefited from neoliberal globalization. If this is their best option, then it's a good thing overall, since we should aim to help the global poor the most. However, I wonder if better options (such as international unions, raising the floor of the race the bottom) may have been unduly closed off, to the benefit of the rich. Some comparatively good-for-the-poor deals may also have been implemented alongside bad-for-the-poor deal such as international debt traps. I'm not sure of the best empirical evidence on a lot of this and need to research it more.

I’m oversimplifying, but something like this overall view does seem likely to be a common pattern and plausible hypothesis. Libertarians have also failed in their mild advocacy for polyamorous marriage or civil unions (despite some version of this being obviously the correct position—anti-polyamory views are blatant bigotry), possibly because there aren't enough rich people who’d benefit from it.

Progressives have been uncharitable and mistaken in their view of libertarianism as a whole. However, progressives have been largely correct in their view of what effects libertarianism as a movement has caused. And, in some ways, this is more important than the nature of libertarianism as a whole. If libertarians resent being so negatively and unfairly judged, they should aim to improve the actual effects of their movement.

Here's what I suspect is really happening: Libertarians promote a combination of good ideas and bad ideas. In the real world, their bad ideas (the ones which only help the rich) are the ones that win—and the rich know this, and this is why the rich support libertarians. The rich have little to fear from libertarians’ harmful-to-the-rich ideas, because they can ensure these ideas won’t win. The rich can happily fund libertarian scholars to promote welfare cuts & deregulation and zoning reform & cutting subsidies to evil industries—perfectly content in the knowledge that the welfare cuts & deregulation will win, and that the zoning reforms & subsidy-cuts will lose.

(The zoning reforms, or immigration reforms, or whatever, may win if the economic situation changes so that these reforms will help the rich enough, but not otherwise—unless the poor can overcome their collective action problems and successfully fight for their interests and rights, which the rich want to use their power to prevent.)

In fairness, a similar pattern may apply elsewhere too. For instance, maybe bad (authoritarian) leftisms tend to win and defeat the good (non-authoritarian) leftisms, because e.g. (1) authoritarian leftists tend to be willing to screw over the non-authoritarian leftists (their former allies) after the Revolution (e.g. in the USSR), and (2) authoritarian leftist leaders may tend to more successfully prevent counterrevolution and/or imperialist regime-change, compared to non-authoritarian leftist leaders, via repression or suchlike. So maybe leftists, like libertarians, may also face a serious puzzle of how to raise the probability that their *good* versions, rather than *bad* versions, are the ones that will win—yet find that the bad versions have distinctive features which give them strategic advantages over the good versions.

I should also note that not all Koch-funded projects benefit the rich, some leftwing projects are also funded by billionaires (whether Koch or others, such as Soros), and it is disputable whether people should always turn down Koch or billionaire money when it is on offer, especially when other funding sources are scarce. Some people erroneously accuse Koch-funded projects of being objectionable even when they aren’t. For instance, Mich Ciurria insinuated that the Koch-funded project on “Grandstanding” (aka virtue-signaling) by Brandon Warmke and Justin Tosi was biased against leftwing radicals, and I argue she is badly mistaken. In several ways, Ciurria’s description of the “Grandstanding” book is misleading. I defend the Warmke-Tosi “Grandstanding” work as important, even valuable for progressive advocacy.

However, the broader system of funding by rich people in general is an enormous hazard. Rich people have the morally least important needs, and they are the fewest in number. For this reason, their interests are objectively the least important. But they are immensely more powerful than all the non-rich people combined, in most cases. This situation is egregiously unjust. The rich people fund scholarship, in philosophy and elsewhere, largely in order to serve their financial interests—even if not all these projects in fact serve their financial interests.

The rich diversify their investments, and presumably some of their investments don’t pay off for them. The rich may also finance some projects which aren't expected to serve their financial interests, for reasons such as to improve their public image. In light of such facts, I say not all recipients of rich people (e.g. Koch or Soros) funding should be assumed to be shills or useful idiots. Also, on the grounds of my actual engagement with the relevant scholarship, I assert that Brandon Warmke & Justin Tosi’s “Grandstanding” work will not likely function to discredit the viewpoints and advocacy of marginalized people or their allies (even though Brandon and Justin are conservatives), contrary to common allegations. Again, some leftwing scholarship is also funded by billionaires such as Soros, but this does not necessarily discredit it.

All that said, on the whole and in general, the rich are our enemy and we must fight against them. We should take a critical eye toward scholarship that they have an interest in funding.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

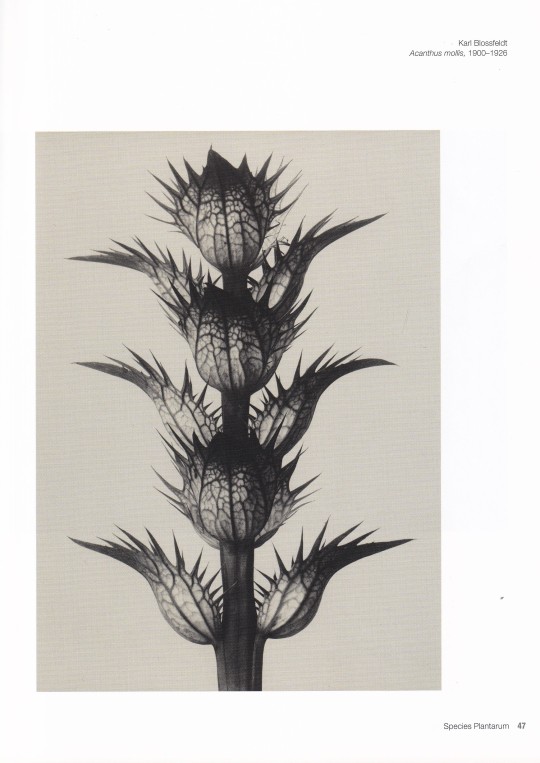

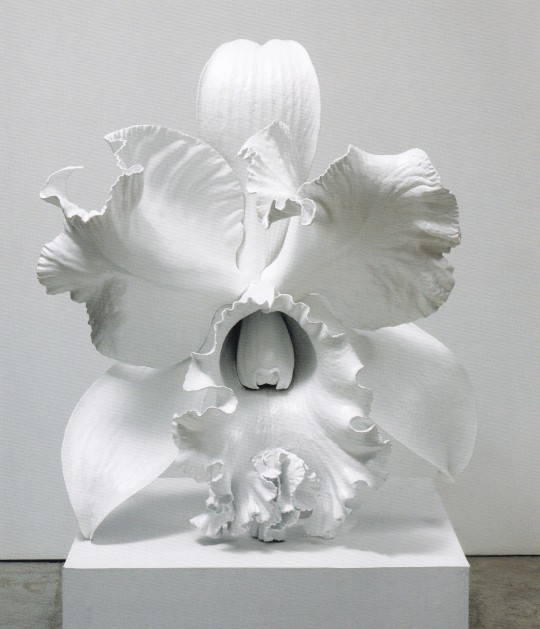

Flowers & Mushrooms

Essays by M. Harder, M. Moschik, T. Teufel, P. Weiermair, V. Ziegelmaier et al.

Hirmer Verlag, München 2013, 256 pages, 24x28,5cm, ISBN 9783777421605

euro 40,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Flowers and Mushrooms takes readers inside the rich and diverse symbolism of its eponymous subjects. Flowers have at times stood for freshness and fertility, transience and death. In addition to its ubiquitous and much-maligned image as a hallucinogen, the mushroom has throughout history signified health and life and served as an important symbol within religious ritual. In recent years though, flowers and mushrooms have become a focus in contemporary art, with artists manipulating the many clichés that surround them and adapting their representation to produce new and unexpected layers of meaning, from social criticism to feminism and the conceptual framework of the erotic. Among the leading plant portraitists are the Swiss duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss, whose series of forty photographs epitomize the potential to shed new light on familiar objects by presenting them in unusual context.

The exhibition at MdM Museum der Moderne - Salzburg presents works from Nobuyoshi Araki, Anna Atkins, Eliška Bartek, Christopher Beane, Karl Blossfeldt, Lou Bonin-Tchimoukoff, Balthasar Burkhard, Giovanni Gastel, Georgia Creimer, Imogen Cunningham, Nathalie Djurberg, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Peter Fischli/David Weiss, Sylvie Fleury, Seiichi Furuya, Ernst Haas, Carsten Höller, Judith Huemer, Dieter Huber, Rolf Koppel, August Kotzsch, David LaChapelle, Edwin Hale Lincoln, Chen Lingyang, Vera Lutter, Katharina Malli, Robert Mapplethorpe, Elfriede Mejchar, Moritz Meurer, Paloma Navares, Nam June Paik, Marc Quinn, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Zeger Reyers, Pipilotti Rist, August Sander, Gitte Schäfer, Shirana Shahbazi, Luzia Simons, Thomas Stimm, Robert von Stockert, William Henry Fox Talbot, Diana Thater, Stefan Waibel, Xiao Hui Wang, Andy Warhol, Alois Auer von Welsbach, Michael Wesely, Manfred Willmann, Andrew Zuckerman.

07/03/24

#Flowers & Mushrooms#exhibition catalogue#MdM Museum der Moderne - Salzburg 2013#Araki#Blossfedt#Gastel#Fischli/Weiss#LaChapelle#Mapplethorpe#Sander#Warhol#Haas#Nam Jun Paik#photography books#fashionbooksmilano

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

01/18/2025•Mises Wire•Lipton Matthews

Michael Huemer’s Progressive Myths is a powerful critique of contemporary progressive dogmas that eviscerates popular cliches with clinical precision. The University of Colorado philosophy professor probes a variety of explosive topics—ranging from racial and gender disparities to environmental and economic concerns—aiming to expose exaggerations and misrepresentations often-perpetuated by progressive narratives.

Progressive Racial Myths

Huemer begins by dissecting myths surrounding race, particularly in the domain of police violence and systemic racism. A prominent thread in progressive discourse is that American police disproportionately kill unarmed black individuals due to systemic racism. However, his interrogation of recent data on police shootings reveals that in 2018, 54 unarmed white people were killed compared to 36 unarmed black individuals. Moreover, conveniently omitted from debates on police misconduct, is that black Americans are overrepresented as dangerous criminals and constitute 43 percent of cop-killers. Huemer finds it odd that progressives can appreciate that most victims of police violence are men because their heightened exposure to violence increases the probability of them having negative interactions with the police. Yet, using this logic to understand why black offenders are shot at higher rates, is a struggle. Admitting that the negative picture of blacks painted by statistics stems from their conduct offends elite sensibilities, however, concocting strange theories to indict the American legal system for racism will not help blacks nor will it protect the victims of crime who are disproportionately black Americans.

Unrelenting in his approach to dismantling myths, he undercuts the credibility of implicit bias, another edifice of progressive propaganda. Citing 2016 research by Carlson and Agerström, Huemer highlights that the widely promoted Implicit Association Test (IAT) does not reliably predict discriminatory behavior. Evidently, priming subjects with images of admirable black people and villainous white people shapes how people perceive race on racial IATs. However, drawing on a meta-analysis by Forscher et al 2019, he notes that there is no evidence suggesting that modifying the Implicit Association Tests translates into behavioral change. These findings undermine the progressive argument that implicit bias is a primary driver of systemic inequality. Heumer concludes that although implicit bias is not a legitimate construct, the concept persists because it is essential to the project of academics who consider themselves crusaders for social justice.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

AfD nutzt „Geheimplan“-Märchen um Remigration zu fordern

Info-direkt:»Im gestrigen „Info-DIREKT Live-Podcast“ sprechen Philipp Huemer (Heimatkurier) und Michael Scharfmüller (Info-DIREKT) über eine von der Antifa-Plattform Correctiv losgetretene Anti-AfD-Kampagne und die patriotischen Reaktionen darauf. Der „Info-DIREKT Live-Podcast“ kann jetzt fast überall nachgehört werden, wo [...] Der Beitrag AfD nutzt „Geheimplan“-Märchen um Remigration zu fordern erschien zuerst auf Info-DIREKT. http://dlvr.it/T1G7lw «

0 notes

Text

If you're rational you don't get to believe whatever you want to believe.

— Michael Huemer

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the twentieth century, everything once held in high esteemhuman nature, science, truth, objective knowledge, art, philosophy, religion, m0rality-had to be debunked. Psychologists sought to show that Man, once considered 'the rational animal', was fundamentally irrational. Freudians found us filled with lust and socially destructive impulses; Marxists found human history dominated by greed and exploitation; sociobiologists found all aspects of human life dominated by 'selfish' drives to reproduce. All three groups found human beings massively self-deceived and considered such supposedly spiritual pursuits as art, religion, and philosophy to be covers for something shallower and far less noble than they appear. Many have remarked on how tiny and insignificant humanity is, how foolish we once were to think ourselves the center of the universe, and how ignorant and helpless we are. Many philosophers, who had once seen their discipline as a rational pursuit of fundamental truths about the nature of reality and our place in it, now denied that philosophy could tell us anything of such truths, if such truths even existed. One influential school of thought declared that philosophers could do no more than discuss how people use words, and that metaphysics, theology, and ethics were all 'meaningless'. Other philosophers declared that there is no such thing as truth, that we can never know it, that we are fundamentally irrational, and/or that objectivity is impossible. American intellectuals attacked what were once their country's most revered forebears-such as Christopher Columbus, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington-as hypocrites, bigots, and exploiters; they attacked the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution similarly. And Western intellectuals attacked Christianity more than any other religion. Modern thinkers have sought to tear down their own society's heros, its religion, its philosophy, its economic and political system-in short, its values.

I do not plan to explain all the intellectual developments mentioned in the preceding paragraph; I rely on the reader's familiarity with contemporary intellectual culture to recognize most of what I have just mentioned. Nor do I plan to discuss their intellectual merits-in some cases, the attitudes may have been justified, while in others they were not. My point here is that, whatever else may be said about them, all those cultural developments have at least one thing in common: cynicism. Western culture of the past fifty years must be among the most cynical cultures in world history. And that thoroughgoing cynicism has made the widespread acceptance of ethical intuitionism impossible in our culture, whatever the intellectual merits of the theory. A culture that insists that humans are fundamentally selfish and ignoble will never accept any account of moral motivation. A culture that declares the notions of truth, knowledge, and objectivity delusory will never accept my account of moral knowledge. And a culture that seeks to tear down all values will never accept moral realism. Subjectivism, non-cognitivism, and nihilism have been popular, in short, because they offer the modern mind the perverse pleasure of debunking morality.

- Michael Huemer. Ethical Intuitionism. pp.242-243

#Michael huemer#huemer#quote#ethical intuitionism#morality#pomo#cynicism#ethics#meta-ethics#meta ethics#philosophy#objective morality

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Suppose that all the knowledge of our civilization was about to be destroyed in some great cataclysm, but we have the opportunity to pass on just one sentence to future generations of people...

The question also features in a Radiolab podcast, where a variety of bad answers are proposed by different people. I was quite struck by how terrible some of them were, which made me glad that these people are not actually making this choice.

Some of the answers are harmful absurdities, like the one that says, "There's no intrinsic value in anything and every action is a futile, meaningless effort." (Yes, someone proposed that that's what we should leave to the future.) Others are just useless, like the person who suggested leaving the single-word sentence, "Why?".

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

El aborto es un tema difícil — Michael Huemer

https://libertades.medium.com/el-aborto-es-un-tema-dif%C3%ADcil-michael-huemer-83486b1d472a

1 note

·

View note