#Menominee poetry

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I Have Not Signed a Treaty with the United States Government // Chrystos

nor has my father nor his father nor any grandmothers We don’t recognize these names on old sorry paper. Therefore we declare the United States a crazy person nightmare lousy food ugly clothes bad meat nobody we know No one wants to go there. This US is theory illusion terrible ceremony The United States can’t dance can’t cook has no children no elders no relatives They build funny houses no one lives in but Everything the United States does to everybody is bad No this US is not a good idea We declare you terminated You’ve had your fun now go home we’re tired We signed no treaty WHAT are you still doing here Go somewhere else and build a McDonald’s We’re going to tear all this ugly mess down now We revoke your papers your soap suds your stories are no good your colors hurt our feet our eyes are sore our bellies are tied in sour knots Go Away Now You must be some ghost in the wrong place wrong time Pack up your toys garbage lies We who are alive now Have signed no treaties Burn down your stuck houses you’re sitting in a nowhere gray glow Your spell is dead Go so far away we won’t remember you ever came here Take these words back with you

#poetry#Chrystos#Indigenous poetry#Menominee poetry#poems of protest#poems of rage#Manifest Destiny#funny#McDonald's#American culture#American poetry#broken treaties#treaties#incantation#Land Rights

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voices of the Land

What better way to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day than to highlight this landmark anthology that commemorates the Indigenous Peoples of North America? When the Light of the World was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry, edited by Joy Harjo with Leanne Howe, Jennifer Elise Foerster, is a curated collection that features the poetry of 160 poets each showcasing a distinct voice from nearly 100 Indigenous Nations. This is the first edition from 2020, published by W. W. Norton & Company in New York.

The anthology is the first to provide a historically comprehensive collection of Native poetry. The literary traditions of Native Americans, the original poets of this country, date back centuries. The book opens with a blessing from Pulitzer Prize winner American Kiowa/Cherokee N. Scott Momaday (1934-2024) and contains introductions from contributing editors for five geographically organized sections. Each section begins with a poem from traditional oral literature and closes with emerging poets, creating a rich and diverse tapestry of Indigenous voices.

Joy Harjo, a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a prominent figure in the literary world. She is known for her work as a poet, musician, playwright, and author. In addition to her contributions to literature, Harjo is also a celebrated performer and has released several albums combining poetry and music. In 2019, she made history by becoming the first Native American United States Poet Laureate and only the second to serve three terms. Throughout her career, Harjo has been a vocal advocate for Indigenous rights and has used her art to shed light on the experiences of Native peoples.

The following is an excerpt from Harjo’s introduction to this work:

“The anthology then is a way to pass on the poetry that has emerged from rich traditions of the very diverse cultures of indigenous peoples from these indigenous lands, to share it. Most readers will have no idea that there is or was a single Native poet, let alone the number included in this anthology. Our existence as sentient human beings in the establishment of this country was denied. Our presence is still an afterthought, and fraught with tension, because our continued presence means that the mythic storyline of the founding of this country is inaccurate. The United States is a very young country and has been in existence for only a few hundred years. Indigenous peoples have been here for thousands upon thousands of years and we are still here.”

View other Indigenous Peoples' Day posts.

View other posts from our Native American Literature Collection.

-Melissa (Stockbridge-Munsee), Special Collections Graduate Intern

We acknowledge that in Milwaukee we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands along the southwest shores of Michigami, part of North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#indigenous peoples' day#When the Light of the World was Subdued#Our Songs Came Through#joy harjo#Leanne Howe#Jennifer Elise Foerster#W. W. Norton & Company#N. Scott Momaday#first nations#native americans#Native poetry#indigenous literature#indigenous poetry#poetry anthology#poet laureate

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Continuing to catch up on recent publications—this time it’s my poem “Ah, My Dear” which appears in the latest issue of Poetry Northwest. So grateful to Keetje Kuipers for including this poem (excerpted above) alongside work by dear poets like Leila Chatti, Michael Wasson, Nicole Callihan, Anna Maria Hong, Eloisa Amezcua, Molly Sutton Kiefer, and Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick! I hope you’ll check out this issue, which includes Kateri Menominee and Kara Briggs, winners of the 2024 James Welch Prize.

0 notes

Text

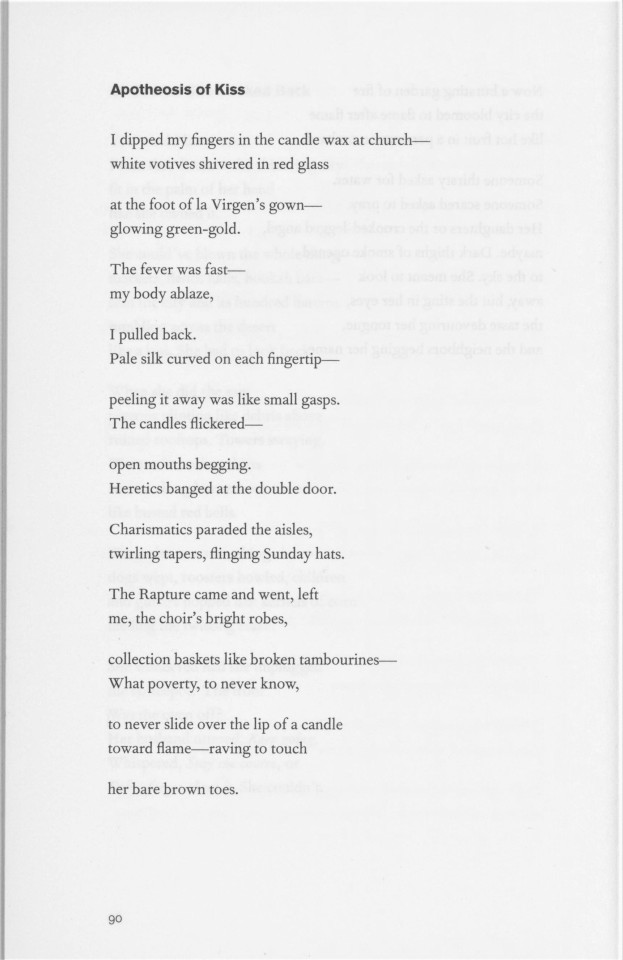

From: Fugitive Colors, by Chrystos (Winner, 1994 Audre Lorde Poetry Competition)

Menominee poet and activist Chrystos was born in San Francisco, California. In her work, she examines themes of feminism, social justice, and Native rights. She is the author of several collections of poetry, including Fire Power (1995), Dream On (1991), and Not Vanishing (1988). In a 2010 interview for the Black Coffee Poet blog, Chrystos stated, “Since my 20’s, when I saw the need to address social justice issues in words, my work just ‘pops out.’ A newspaper story, an incident from my life, a book, a song, a garden snake, a sad face I see—I have no idea, actually, how these become poems. A line begins in my mind and won’t leave me alone. I’ve learned to sit and write it down and the rest just flows.”

Chrystos’s work has been featured in the anthologies This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981), edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa, and Living the Spirit: A Gay American Indian Anthology (1988), edited by Will Roscoe. With Tristan Taormino, she coedited the anthology Best Lesbian Erotica 1999.

(I apologize for not attributing it in the original post!)

#Chrystos#how did I post this without attribution#it's my favorite of her poems!#pls read more of her poetry

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two pieces for The Minison Zine, Issue 12: Mythological Minison (August 2021) .

Read the full issue below!

To see more from the Minison Project, or submit something yourself, check out their website here:

*shoutout to @saradika for the lovely headers!

#writeblr#poetry#spilled ink#writing#mini sonnets#minisons#mythology#folklore#folk tales#legends#Menominee#Egypt#egyption mythology#isis#osiris#isis and osiris#Manabush#Manabush and the Origin of Fire#lit mag#literary magazine#the minison project#mythogical minison#2021#published works#allison dedecker#gods#goddesses#god#goddess

1 note

·

View note

Text

"The Wandering Song" Central American Writing in the United States, prelude by Leticia Hernández-Linares TribeLA Magazine • Los Angeles #Chicano_Writings #HéctorTobar #Hispanicwriters #Latinoliterature #LeticiaHernándezLinares #Luisrodriguez #Tia_Chuca_Press

New Post has been published on http://tribelamagazine.com/wandering-song-central-american-writing-united-states-prelude-leticia-hernandez-linares/

"The Wandering Song" Central American Writing in the United States, prelude by Leticia Hernández-Linares

The Wandering Song: Central American Writing in the United States, Tia Chucha Press, 2017 (Northwestern University Press distributor)

Prelude by Leticia Hernández-Linares LA MISIóN, SAN FRANCISCO November 28, 2016

HOME WAS BEHIND US, always somewhere else. Born into 1970s Los Angeles, a few months after my parents arrived in the United States, I experienced El Salvador as a distant place we referred to as “back home.” Civil war disappeared the pos- sibility of return, and yet, my parents’ country transplanted itself within the walls of this other home, colored our beans, determined our verb conjugations and our difference. “Back home” shadowed our lives here; my parents baptized me en la Parroquía Sagrada Familia, the church in my father’s neigh- borhood, la Colonia Centroamérica, and thanks to his uncen- sored storytelling, I am aware that my conception occurred at la Playa San Diego, La Libertad. Most of my family re- mained in El Salvador and we called them on rotary phones, often communicating through static-filled calls with delays that underscored the vast space between us.

I developed a deep bond with “back home,” despite the distance and thanks to the thick thread of my father’s stories. Donning the folkloric dresses my grandmother would send north, I would put on shows for family and friends, making up the steps no one taught me. My father, bass player for Los Lovers, a bilingual Salvadoran band, and my mother who cro- cheted and did ceramics taught me who I was through mem- ory, lyrics, and handmade things. As I came of age, textured stories wrapped me tight in a web of nostalgia and wander- ing, all despite my privileged place of birth.

Home was behind us, always somewhere else. The only other place my family and I traveled, other than back home, was the Mission District of San Francisco, the Central Amer- ican heart of the Bay Area; the trip, the soundtrack––the very road itself––were equally important parts of the experience. As a twenty-something, I returned to the Mission. I came following in the footsteps of an uncle who taught me how to heal and how to own the indigenous and the migrant in my blood. I came here in pilgrim- age to be part of a thriving community of artists and writers, and have lived on the same block since 1995. Ironically, during the last year, my poet- husband Tomás, our two sons, and I have been fighting an eviction from our home. We have lived under an expiration date on how long we can stay in this community of neighbors, murals, action, and convivencia—at least that’s what it was once. Only the latest victims in a terrible epidemic of displace- ment by eviction or by fire, we live with a sense of impending exile from this, my longest, and our sons’ only home.

WRITERS OF THE CENTRAL AMERICAN DIASPORA have occupiedhaky literary and historical ground ––until now. For so many years the voices in this book have, largely unbeknownst to one another, hummed the melody of a wander- ing song. My co-editors, Rubén Martínez, Héctor Tobar, and I present a chorus of writers, artists, and performers who unequivocally answer a critical question: yes, there really is a Central American Literature and it includes a complex, bilingual, and multinational space. This book offers a literary soundtrack where there was mostly silence, and assembles a spine that can withstand the telling of who we are in this country.

In his study, La Lengua Salvadoreña, Pedro Geoffrey Rivas reflects on the importance of tracing the geography of language, and how “el mundo es el lugar donde uno vive lo que se ha dicho y queda escrito… adónde uno habla. Donde está la voz o su ausencia. La voz es el mundo.” (“The world is the place where one lives what has been said and remains written… where one speaks. Where the voice is, or its absence. The voice is the world.”)

Rivas writes of how inscription makes and unmakes place, and claims that his study, a tribute to homeland, will only capture the Salvadoran voice of a certain time because language is ever-changing with place. The earth is not the only part of our landscape that moves. We compile and present all these words here, in this time and place, without proposing to define or limit what Central American Literature is or will be. Rather, we offer a significant piece of a much larger picture.

The various stages of Central American immigration to the United States have largely emerged from situations of extreme violence and poverty. While movement and presence can be traced to the 1950s and 1960s, war and its long devastating aftermath in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua was the principal impetus for immigration patterns in the 1970s and 1980s. Frequent earthquakes, hurricanes, the importation of gang violence from the U.S., and ongoing economic instability continue to push our gente to make the journey.

During the last few years, “surges” of unaccompanied children arriving in the U.S. provoked renewed attention. Now more than four million Central Americans reside in the United States, and no less than two of our home countries in the so-called Northern Triangle of Central America are consid- ered the most dangerous in the world. We are immigrant and refugee, first, second, and even third generation.

This book enables us to retrace our steps and chart the unincorporated territory of our stories.

We hope that you, Chapín in Los Angeles, Guanaca in D.C., Nicoya in San Francisco, Panameño in New York will feel at home in these pages and invite friends to take the journey with you. In the first section, El Camino Largo, we travel back and forth in time and between here and there, rendering different aspects of the journey that forms the foundation of our community and this anthology. In En La Voz Alta, poets and performers string together voices and pieces of language to craft terms to define themselves. While spo- ken word and performance writers appear throughout the book, this section privileges the act of storytelling and community engagement as a substantive part of our literary craft. In La Poesía de Todos, we feature work that bridges a multiplicity of themes and genres, leaving the path ahead, beyond this book, open.

Ultimately, The Wandering Song: Central American Writing in the United States embodies our canto popular. This Tía Chucha Press anthology demon- strates how we continue to shift the map, what no amount of anti-immigrant sentiment and xenophobic backlash will erase. As Rubén Darío implied in the poem this book is named after, we offer salve through our singing, and we hope you will sing along—loudly, y con ganas.

The Editors: Leticia Hernández Linares, author of Mucha Muchacha – Too Much Girl and three times San Francisco Arts Commission Individual Artist Grantee. Rubén Martinez, the son and grandson of immigrants from El Salvador and Mexico is a writer, performer, and professor of literature and writing at Loyla Marymount University. Héctor Tobar is a novelist and journalist, the author of four books, and the Los Angeles-born son of Guatemalan immigrants

Tia Chucha Press began in 1989 with the publication of Luis J. Rodriguez’s first book, the 19-poem collection “Poems Across the Pavement,” designed by Jane Brunette of Menominee/German/French descent, who has remained as TCP designer ever since. With Jane’s artistic skills for covers and inside pages, and Luis as founding editor, the press began publishing the best collections of the thriving Chicago poetry scene – home of the Poetry Slams – featuring poets such as Patricia Smith, David Hernandez, Michael Warr, Lisa Buscani, Tony Fitzpatrick, Cin Salach, Carlos Cumpian, Elizabeth Alexander, and more.

#Chicano Writings#HéctorTobar#Hispanicwriters#latinoliterature#LeticiaHernándezLinares#luisrodriguez#Tia Chuca Press

0 notes

Text

The Real Indian Leans Against // Chrystos

for Nancy Emery

the pink neon lit window full of plaster of paris & resin Indians in beadwork for days with fur trim turkey feathers dyed to look like eagles abalone & bones The fake Indians, if mechanically activated would look better at the Pow Wow than the real one in plain jeans For Sale For Sale with no price tag On holds a bunch of Cuban rolled cigars one has a solid red bonnet & bulging eyes ready for war Another has a headdress from hell with pained feathers no bird on earth would be caught dead in All around them are plastic inflatable hot pink palm trees grinning skulls shepherd beer steins chuckling check books black rhinestone cats & a blow up blonde fuck me doll for horny men who want a hole that will never talk back There are certainly more fake Indians than real ones but this is the usa What else can you expect from the land of sell your grandma sell our land sell your ass You too could have a fake Indian in your parlor who'll never talk back Fly in the face of it I want a plastic white man I can blow up again & again I want turkeys to keep their feathers & the non-feathered variety to shut up I want to bury these Indians dressed like cartoons of our long dead I want to live somewhere where nobody is sold

#poetry#Chrystos#Indigenous poetry#American poetry#poems of protest#poems of rage#capitalism#sell yourself#feminist poetry#Menominee poetry#American racism#anti-capitalist poetry

1 note

·

View note

Text

I Walk in the History of my People // Chrystos

There are women locked in my joints for refusing to speak to the police My red blood full of those arrested in flight shot My tendons stretched brittle with anger do not look like white roots of peace In my marrow are hungry faces who live on land the whites don’t want In my marrow women who walk 5 miles every day for water In my marrow the swollen hands of my people who are not allowed to hunt to move to be In the scars of my knee you can see children torn from their families bludgeoned into government schools You can see through the pins in my bones that we are prisoners of a long war My knee is so badly wounded no one will look at it The pus of the past oozes from every pore This infection has gone on for at least 300 years Our sacred beliefs have been made into pencils names of cities gas stations My knee is wounded so badly that I limp constantly Anger is my crutch I hold myself upright with it My knee is wounded see How I Am Still Walking

#poetry#Chrystos#Indigenous poetry#American poetry#Menominee poetry#California poetry#Wounded Knee#poems of protest#poems of rage#cultural genocide#resilience#walking#feminist poetry

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week

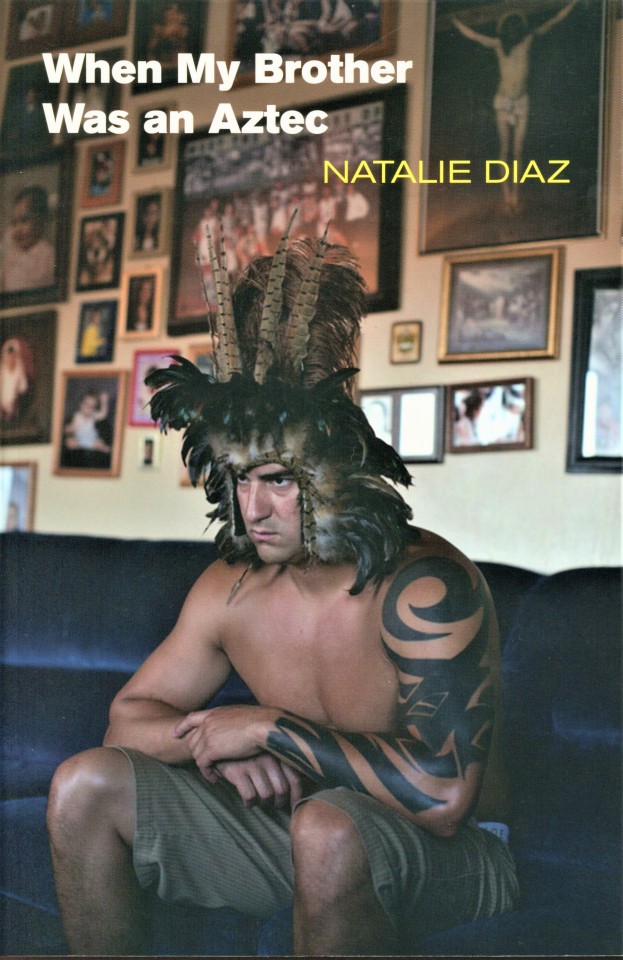

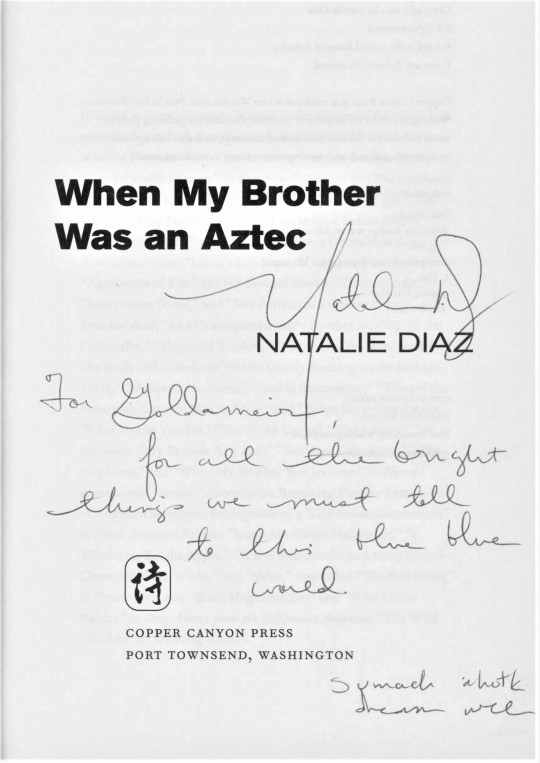

NATALIE DIAZ

Coming at you with another Indigenous woman writer, we present Mojave and Latinx poet, former college and professional basketball player, and Indigenous language activist, Natalie Diaz. Diaz is the author of two collections of poetry. Her most recent publication, Postcolonial Love Poem, published in 2020 by Graywolf Press, won her the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and was a finalist for the National Book Award among many others. UWM Special Collections preserves a signed copy of Diaz’s first poetry collection, published in 2012 by the Copper Canyon Press, When My Brother Was an Aztec. This debut collection was the winner of the 2013 American Book Award for poetry as well as a being a Kessler Poetry Book Award finalist, and was also a 2012 Lannan Literary Selection. [Note: the inscription reads “For Golda Meir”; the UWM Library is named after Israel’s first woman prime minister, as Meir was raised and educated in Milwaukee and attended a UWM predecessor institution.]

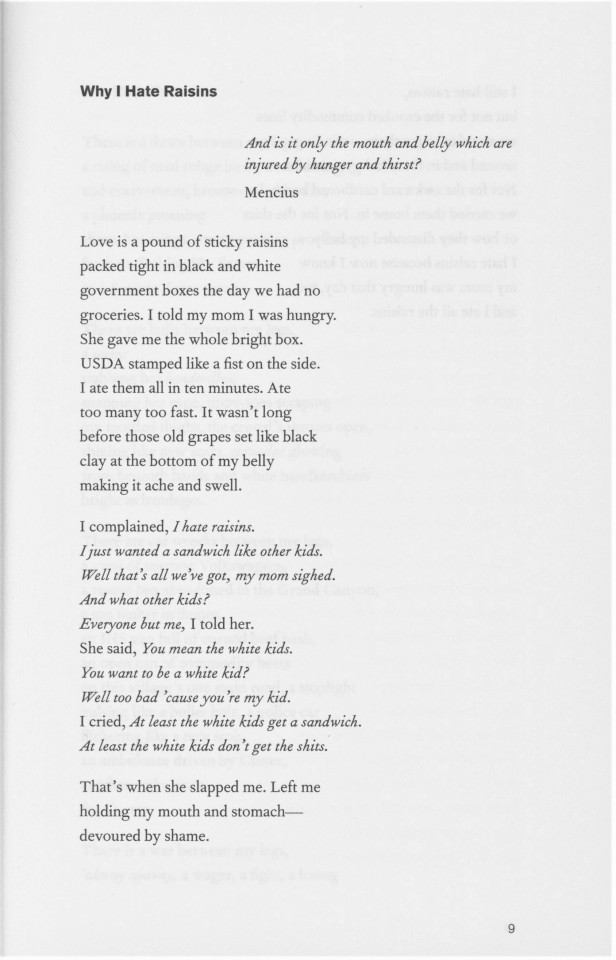

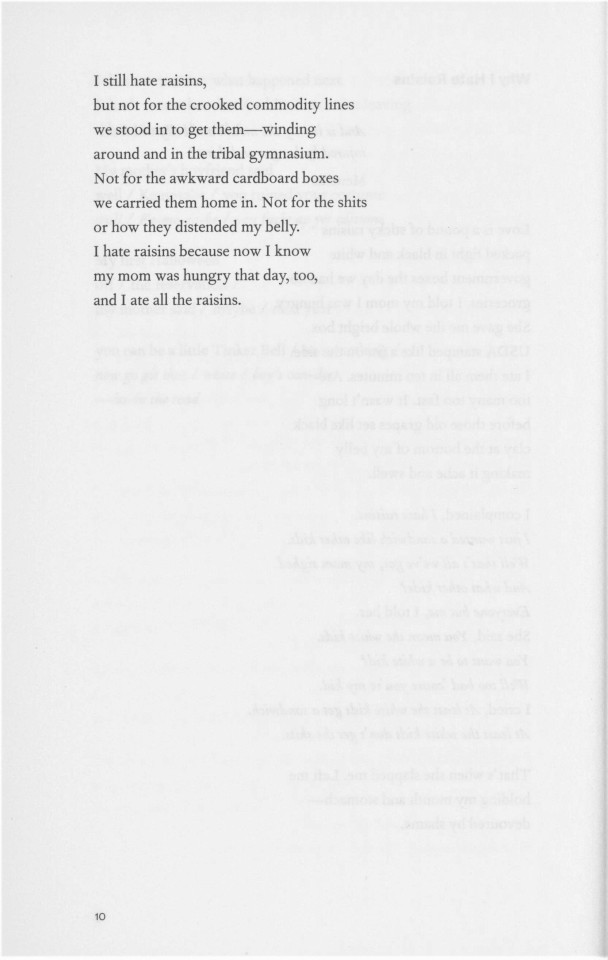

Born on the Fort Mojave Indian Reservation in Needles, California, Natalie Diaz is Mojave and an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Community. Diaz expresses the deeply rooted historical culture found in tribal life in When My Brother Was an Aztec through her documentation of the persona her brother takes on as a fallen Aztec King of mythic power while struggling with addiction. She details her early life dealing with poverty on the reservation, forced assimilation, the bonds of family, witnessing her brother’s struggle with crystal meth, issues with racism off-reservation, and her own growth into adulthood where she explores her sexuality. The cover art for this collection is by Roberto Westbrook and portrays the character that Diaz’s brother identified as while struggling with his addiction.

A speaker of the Mojave language, as well as English, and Spanish, Diaz utilizes all three languages in When My Brother Was an Aztec, beginning the book with a Spanish proverb, “No hay mal que dure cien años, ni cuerpo que lo resista,” which translates to “There is no evil that lasts a hundred years, nor a body that resists it.” In the struggle to keep the Mojave culture alive, Diaz has begun recording and transcribing the Mojave language with the last elder Mojave speakers in 2012 with the help of Arizona State University for the Fort Mojave Language Recovery Program. While working as an Associate Professor at Arizona State University in 2018, Diaz was named the Maxine and Jonathan Marshall Chair in Modern and Contemporary Poetry.

Author Photo is by Joseph Gidjunis.

See other writers we have featured in Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week.

View more Women’s History Month posts.

– Isabelle, Special Collections Undergraduate Writing Intern

We acknowledge that in Milwaukee we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands along the southwest shores of Michigami, part of North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week#women's history month#natalie diaz#when my brother was an aztec#national book award#american book award#poetry#woman poets#native american poetry#mojave#arizona state university#language recovery#gila river indian community#postcolonial love poem#roberto westbrook#joseph gidjunis#lannan literary selection#old dominion university#basketball#california#isabelle

118 notes

·

View notes

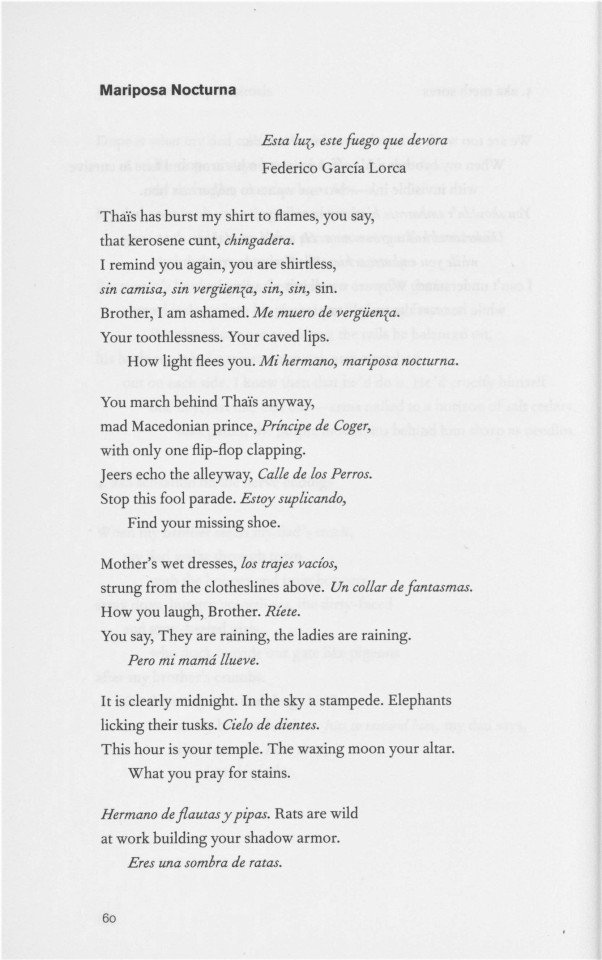

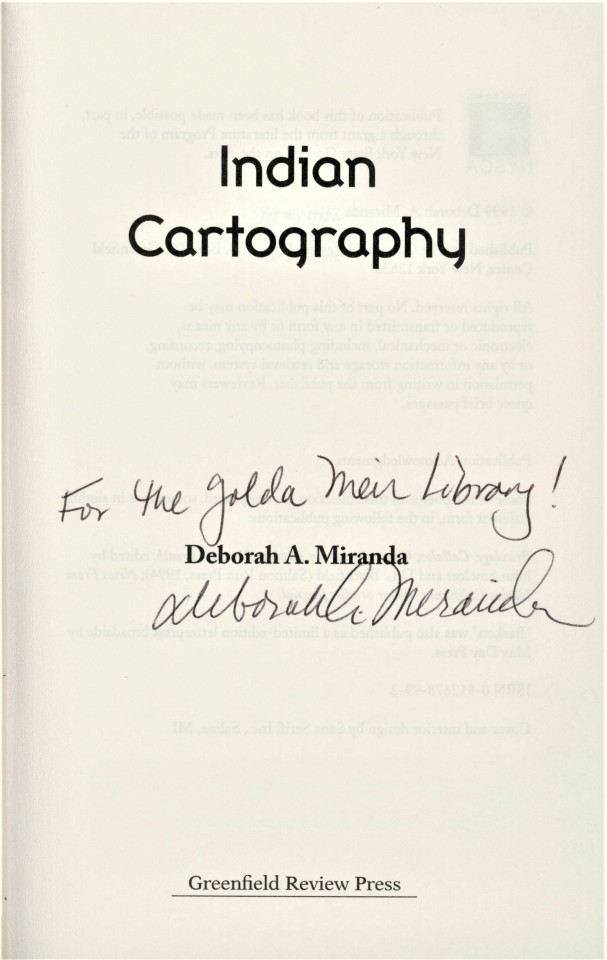

Photo

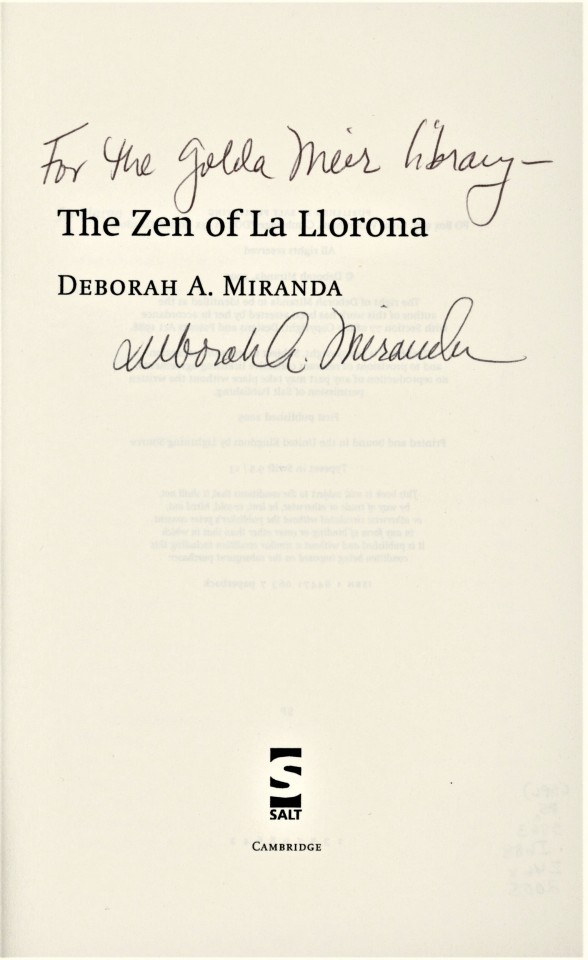

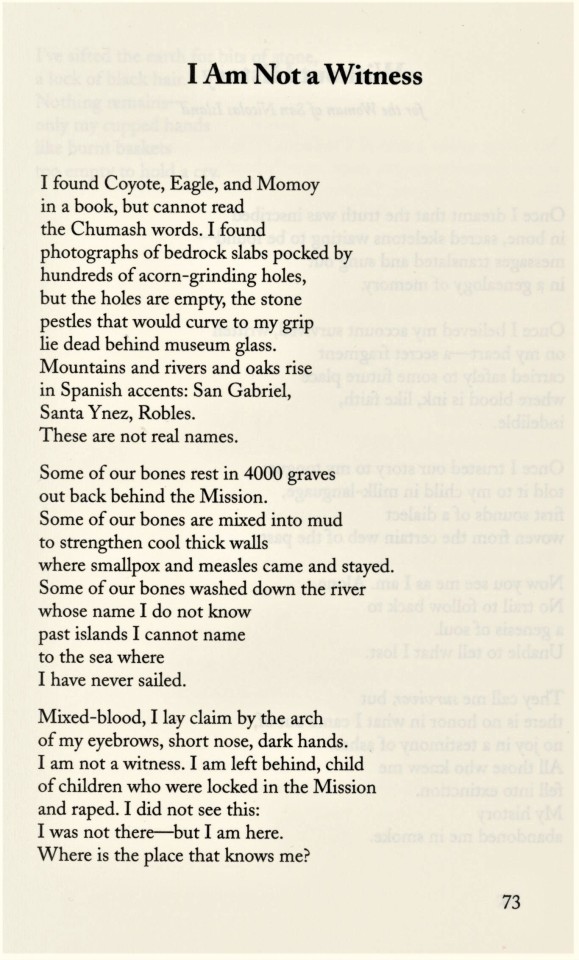

Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week

DEBORAH A. MIRANDA

Deborah A. Miranda is poet, professor, and recipient of the 2000 Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers Writer of the Year Award. An enrolled member of the Ohlone-Costanoan Esselen Nation of California, Miranda was born in Los Angeles to an Esselen/Chumash father and a Jewish-French mother—a mix of cultures that play a central role in the author’s writing.

UWM Special Collections preserves a signed presentation copy to our library (which is named after Golda Meir, who grew up in Milwaukee) of Miranda’s 1999 poetry collection Indian Cartography: Poems, published by the historically diverse Greenfield Review Press. The book received the Diane Decorah Memorial First Book Award for Poetry from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas, a special honor as it is one of the few literary awards presented to Native Americans by Native Americans. The book’s cover is a monoprint, called “August Sky,” by Kathleen R. Smith of the Mihilikawna Pomo and Yoletamal Coast Miwokwhich. Our collection also holds a signed presentation copy of Miranda’s 2005 poetry collection, The Zen of La Llorona, published by Salt Publishing. This collection was nominated for the Lambda Literary Award, which celebrates “vibrant, dynamic” LGBTQ storytelling.

In her author’s note for Indian Cartography: Poems, Miranda observes that people believed all Natives of California to have “died.” Acknowledging her peoples’ struggles, the author dedicates the book: “for my tribe, my family, our children.” This first collection focuses on the author’s childhood and her journey back to her Ohlone-Costanoan Esselen roots, after Spanish Missions’ and Mexican secularization’s near erasure of the culture. Miranda dedicates The Zen of La Llorona to her spouse, poet, Margo Solod, stating that this second collection of her poetry is

a record of my journey out of destruction and into a North American indigenous state of creativity, the erotic, and joy.

This book follows the author’s personal growth into adulthood and motherhood, through a divorce, and her attempts at finding love as a queer person. In this collection, Miranda states that Indigenous peoples are all children of La Llorona, as they continue to fight for federal recognition in the American historical canon after surviving termination efforts by the U.S. government for decades.

Deborah Miranda continues to write and is currently the Thomas H. Broadus, Jr. Professor of English Emeritus at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. Her research includes Indigenous women's poetry, California Indian issues both historically and in contemporary times, and North American Indigenous environmental and social justice concerns. She runs workshops at universities across the United States and maintains a blog through Twitter under the username, @badndns.

The photographic portrait used here is by Margo Solod from the website Split this Rock, presenting Miranda’s poem “We.”

See other writers we have featured in Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week.

–Isabelle, Special Collections Undergraduate Writing Intern

We acknowledge that in Milwaukee we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands along the southwest shores of Michigami, part of North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week#deborah a miranda#women's history month#ohlone costanoan#native american writers#Native American women#esselen#chumash#indigenous poetry#Indian Cartography#Greenfield Review Press#the zen of la llorona#salt publishing#kathleen smith#monoprint#california#first book award#native writers circle#lgbtq poetry#isabelle#women poets

51 notes

·

View notes

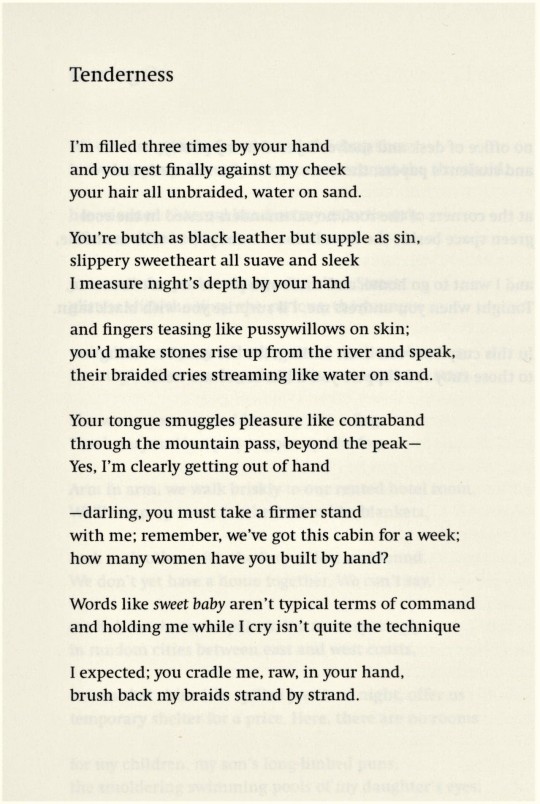

Photo

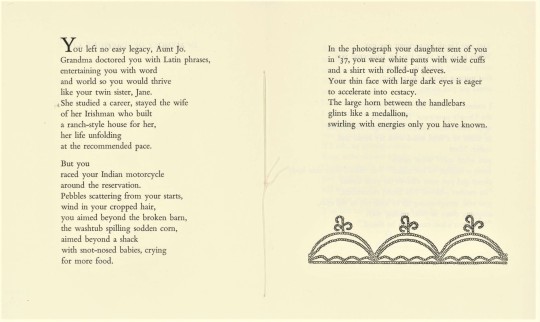

First Nations Fine Press Friday

Roberta Hill

In association with our post this week on Roberta Hill, we present the fine press printing of an excerpt from Hill’s 1993 poem, Your Fierce Resistance. Printed in an edition of 150 copies at the Minnesota Center For Book Arts (MCBA) in conjunction with literary center The Loft for the Inroads: Writers of Color series,Your Fierce Resistance is an excerpt of a longer poem of the same title. The full-length poem can be found in Roberta J. Hill’s (then, Roberta Hill Whiteman) second poetry book collection, Philadelphia Flowers: Poems, published by the Holy Cow! Press in 1996. The edition was was printed by Robert Johnson of the Melia Press and wood engraver, printer, designer, poet, and illustrator Gaylord Schanilec using Bembo type on Mohawk Superfine paper, with Fabriano Italia endsheets and Moriki Over Arches covers, supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Hill completed her PhD with a biographical study of her paternal grandmother, Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill—the second American Indian woman to earn an M.D. in the United States. Minoka was of Mohawk descent, but had moved with her husband to the Wisconsin Oneida Reservation where she opened a “kitchen clinic” to serve the Oneida peoples. She’s said to have been adopted by the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin—the only person in the 20th century to be officially adopted by them—and was given the name Yo-da-gent, meaning “she who saves” or “she who carries help”.

The book, however is dedicated to another family member, Josephine Coté, Hull’s matrilineal aunt. Nonconformity must run in the women of this family, as Hill’s writing honors her aunt’s outward resistance to all pressures of assimilatory expectations, both inside and outside the Oneida reservation. Hill recalls a conversation with Coté, in Your Fierce Resistance,

Then you asked me, “What passes from a mother to her child?” You shifted your thin body closer and put your elbows on your knees. “Its mother’s blood. The blood remembers,” you said, straightening up to look me in the eyes, snapping them in your teasing way. “Whatever’s lost can often be found.”

Roberta Hill’s three poetry collections revolve around the communal feeling of disconnection within the Oneida Nation’s people, where she utilizes nature-centric Native American/First Nations ideals to take a firm stance against the capitalistic consumption polluting our environment. Hill has read her poems throughout the United States and at International Poetry Festivals in Medellin, Columbia and Poesia Do Mundo in Coimbra, Portugal, as well as in China, Australia, and New Zealand. Hill has retired from her position as a Professor of English and American Indian Studies, affiliated with the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, in May of 2020, and now lives in the Driftless area of Wisconsin.

View more Fine Press Friday posts.

–Isabelle, Special Collections Undergraduate Writing Intern

We acknowledge that in Milwaukee we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands along the southwest shores of Michigami, part of North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#Fine Press Friday#Fine Press Fridays#Fine Press#Your Fierce Resistance#Roberta Hill#Josephine Cote#Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill#Robert Johnson#Gaylord Schanilec#Minnesota Center for Book Arts#The Loft#Inroads#Writers of Color series#Mohawk#Philadelphia Flowers#Oneida Nation of Wisconsin#Native American Poets#Indigenous Writers#Bembo#Fabriano#Moriki Over Arches#National Endowment for the Arts#Limited Edition#Isabelle

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week: JOY HARJO

Joy Harjo is the first Native American Poet Laureate for the United States, receiving the honor in June 2019, and is known as a major figure in contemporary American poetry. A member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation from Oklahoma, Harjo draws on First Nation storytelling and histories alongside feminist and social justice poetic traditions in her writing. Her critically acclaimed work is often autobiographical and focused on the need for remembrance and transcendence, earning her the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers Circle of the Americas among many other awards. She published her first volume, a nine-poem chapbook entitled The Last Song, in 1975, demonstrating a powerful insight into the fragmented history of indigenous peoples that later evolved into What Moon Drove Me to This?, a full-length volume of poetry combining everyday experiences with deep spiritual truths. She earned a BA from the University of New Mexico and MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Before being named Poet Laureate, Harjo was a Professor and Chair of Excellence in Creative Writing at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

UWM Special Collections holds 15 titles by Harjo in our Native American Literature Collection. Shown here from top to bottom are:

1.) Photograph of Joy Harjo by Karen Kuehn pilfered of the interwebs. 2.) Crazy Brave: A Memoir. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012. 3.) A Map to the Next World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2000. 4.) What Moon Drove Me to This? New York: I. Reed Books, 1979. 5.) An American Sunrise. New York: W.W. Norton, 2019. 6.) Fishing. Browerville, Minn.: Ox Head Press, 1992. Limited edition of 400 copies.

See other writers we have featured in Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week.

-Emily, Special Collections Writing Intern

We acknowledge that in Milwaukee we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands along the southwest shores of Michigami, part of North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week#Joy Harjo#Poet Laureate#Muscogee Poets#Creek Poets#poetry#Native American#Native American Literature Collection#women's history month

192 notes

·

View notes

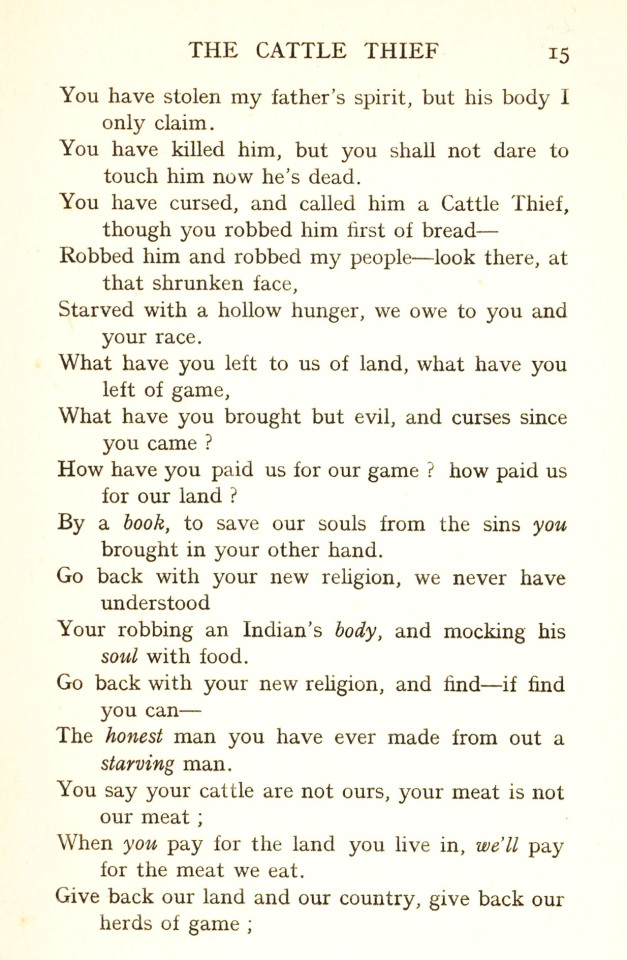

Photo

A Henty A Week

We are using the occasion of Native American Heritage month to state unequivocally that we reject George Alfred Henty’s representation of Native Americans in his work Redskin and Cow-boy: A Tale of the Western Plain. We hold two editions of this title published by Charles Scribner’s Sons: one published in 1891 and another published in 1916.

The tale is exactly what might be expected from a 19th century British imperialist concocting an adventure story based upon the themes of manifest destiny, ranching, and American cowboys. "Cowboys vs Indians” themes and tropes pervade not only popular culture but also the curriculum and academy of the United States still. Instead of reading historical Western fiction written by white people like G.A. Henty, we encourage readers to seek out works created by native peoples. Our own Native American and Hawaiian Literature Collection is a good place to start.

For example, the excerpt above from the poem “The Cattle Thief” by Tekahionwake (E. Pauline Johnson, 1861-1913), published in her 1895 collection The White Wampum, explores the violence of the westward migration of European settlers in the Americas on native people. You can read more about this poet and her publications in this post.

Likewise, one can read Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz‘s and Dina Gilio-Whitaker’s “All the Real Indians Died Off”: and 20 Other Myths About Native Americans (Beacon Press, 2016), to tackle biases and stereotypes about Native American/settler interactions. For example, see their chapters on “Myth 5: Indians Were Savage and Warlike” or “Myth 7: Europeans Brought Civilization to the Backward Indians.” Learn more about these authors and their publication in this post

Want to learn more? Check out our post series Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week.

Or, stop by during our walk-in hours, send us an e-mail, or request a research consultation in order to find more great resources by Native Americans or First Nations people!

UWM Special Collections department has a UWM Native American and Hawaiian Literature Collection, which endeavors to be a comprehensive collection of American Indian and Native Hawaiian thought and literary effort consisting of materials written or created by native peoples of the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, and Canada from all historical and contemporary periods. Materials in the collection include fiction, non-fiction, poetry, poetry, journalism, illustration and photography, transcriptions of oral literature, and native language materials. UWM Special Collections also works closely with the Electa Quinney Institute to identify, acquire, and preserve scholarly, educational, and historical materials relating to American Indian languages, especially the endangered languages of the American Indian peoples of Wisconsin (Ho-Chunk, Mohican, Menominee, Ojibwe, Oneida, and Potawatomi).

-Katie, Special Collections Graduate Intern

We acknowledge in Milwaukee that we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homeland along the southwest shores of Michigami, North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#George Alfred Henty#G.A. Henty#A Henty a Week#racism in literature#Historical Curriculum Collection#young adult fiction#illustrated books#colonialist fiction#Native Americans#american indians#Native American Heritage Month#UWM Native American and Hawaiian Literature Collection#land acknowledgement#Katie

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SPOTLIGHT: Former Kansas Poet Laureate Denise Low (Lenape/Cherokee)

Denise Low, Kansas Poet Laureate from 2007-2009, offered a presentation in Special Collections today on “Indigenous Re-Identification: Cross-Genre Autobiographies,” discussing self identity in the storytelling found in ledger art, the work of Leslie Marmon Silko, Thomas Weso’s Good Seeds: A Menominee Food Memoir, and her own Turtle’s Beating Heart: A Lenape Story of Survival.

Low is an award-winning author of 30 books of prose and poetry. To spotlight her presence here, we present an artist’s book of her poems, Quilting, illustrated and printed in hand-set Caslon Bold in 1984 by Linda Samson-Talleur in an edition of 183 signed copies at the Holiseventh Press in Lawrence, Kansas. The paper was handmade by Jennie Frederick of Kansas City Paperworks.

Of her work in this set of folded, handmade-paper broadsides, Denise Low writes:

These quilting poems, though mostly written during the summer of 1982, have taken all my life to write. . . . Quiltmaking is an apt metaphor for making art. The poetry I like best, in fact, is a synthesis of everyday objects and events, chosen from a rag-bag stockpile and transformed by the human touch. . . . I myself do not quilt, or even sew. Nonetheless, I feel included in the vast circle of women who have had families and have tried to make objects of utility and beauty from fabric and yarn. . . . Such tacit nurturance is an inheritance threaded through the generations.

View other Native American Women Writers we have highlighted.

#Native American/First Nations Woman Writer of the Week#denise low#quilting#Linda Samson-Talleur#Jennie Frederick#Holiseventh Press#Kansas City Paperworks#handmade paper#letterpress printing#bookarts#poetry#poet laureate#Native Americans#indiginous writers#uwm special collections#Milwaukee Native American Literary Cooperative#mnalc#Katie

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wandering Song: New literary anthology from Tia Chucha Press - The press that began with Chicago Poetry, and poet laureate emeritus Luis Rodriguez TribeLA Magazine • Los Angeles #HéctorTobar #Hispanicwriters #Latinoliterature #LeticiaHernándezLinares #Luisrodriguez #Tiachuchapress

New Post has been published on http://tribelamagazine.com/new-literary-anthology-from-tiachucha-press-began-with-chicago-poetry-and-poet-laureate-emeritus-luis-rodriguez/

The Wandering Song: New literary anthology from Tia Chucha Press - The press that began with Chicago Poetry, and poet laureate emeritus Luis Rodriguez

The Wandering Song: Central American Writing in the United States, Tia Chucha Press, 2017 (Northwestern University Press distributor)

Tia Chucha Press presents an anthology of Central American writers living in the United States. It features work that captures the complexity of a rapidly grown community that shares certain experiences with other Latino groups, but also offers its own unique narrative. This is the first-ever comprehensive literary survey of the Central American diaspora by a U.S. publisher, perfect for high school, college, or university courses in U.S. literature, Latino Literature, Multicultural Studies, and Migration Studies.

The Wandering Song: Central American Writing in the United States is a multi-genre collection of poems, short stories, essays, memoir, novel excerpts, and creative nonfiction. The book showcases writers who render a multiplicity of experiences as refugees from the wars of the 1980s to those who barely remember the homeland, or who were born in el norte. These are writers from both coasts and from the middle. Their aesthetics range from hip hop – inflected to high literary to acrobatics in Spanglish. Yet it is a community that shares a history of violence, both here and back home – and the hope, and healing that ensures its survival. They include migrants or children of migrants from countries in the so-called Northern Triangle–El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras–considered one of the most violent places on earth, as well as from Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama.

The Editors: Leticia Hernández Linares, author of Mucha Muchacha – Too Much Girl and three times San Francisco Arts Commission Individual Artist Grantee. Rubén Martinez, the son and grandson of immigrants from El Salvador and Mexico is a writer, performer, and professor of literature and writing at Loyla Marymount University. Héctor Tobar is a novelist and journalist, the author of four books, and the Los Angeles-born son of Guatemalan immigrants

This week, we will feature bookmarks of poetry, a short story, an essay, a memoir, an excerpt, and creative nonfiction from The Wandering Song. Available at amazon.com / tiachucha.org/bookstore / and your local bookstore.

Tia Chucha Press began in 1989 with the publication of Luis J. Rodriguez’s first book, the 19-poem collection “Poems Across the Pavement,” designed by Jane Brunette of Menominee/German/French descent, who has remained as TCP designer ever since. With Jane’s artistic skills for covers and inside pages, and Luis as founding editor, the press began publishing the best collections of the thriving Chicago poetry scene – home of the Poetry Slams – featuring poets such as Patricia Smith, David Hernandez, Michael Warr, Lisa Buscani, Tony Fitzpatrick, Cin Salach, Carlos Cumpian, Elizabeth Alexander, and more.

0 notes