#Max Roach was famous for his protest music

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What your favorite jazzer says about you!

Louis Armstrong- You don’t know why I’ve just broken into your house and asked you at gunpoint what your favorite jazz artist is, as you don’t listen to much jazz.

Miles Davis- You’re basic.

Bill Evans- You’re racist.

Chett Baker- You want to have sex with Chett Baker.

Sun Ra- As a kindergartner, you were reprimanded for eating paper, an event that has haunted you for life. A career as a very unique artist awaits you. Also, you can name every species of preying mantis, all 51 of them.

Pharaoh Sanders- You don’t know shit about preying mantises.

Alice Coltrane- You’ve been trying to find Satchinada for the last 20 years, but it continues to allude you.

Phelonois Monk- Your favorite kind of sandwich is peanut butter and jelly.

Peter Brotzmann- You didn’t stop eating paper at kindergarten. In fact, as you read this, you’re currently eating the stuff. You do you, I guess.

João Gilberto- You constantly carry around a fanny pack full of important provisions such as trail mix. You’re disappointed that no one wants to use your Netflix password.

Wayne Shorter- Everyone laughs at your pointy shoes. “What are you some kind of elf?” they ask. Then, you kick them. They aren’t laughing after that.

Duke Ellington- A prestigious career of drawing of drawing furry smut awaits you. I salute you.

Ryo Fukuri- You keep a shotgun beneath your bed in case someone with tattoos comes too close to your front lawn.

Max Roach- You’re wondering if I may have switched those last two. No, I did not. Shut up.

Charles Mingus- You wear a bald cap wherever you go because it increases the chances of being slapped on the head- the most enjoyable aspect of living.

John Coltrane- You’ve been kicked out of eighteen Whole Foods stores, and you plan to make that number in the triple digits before you depart this green earth. Nothing brings you more satisfaction than opening the nut dispensers and watching the waterfall of cashews descend onto the ground.

Art Blakey- Fuck if I know.

#you see#Louis Armstrong is the most known jazzer#Miles Davis is the second most well known#Bill Evans is white#Chett Baker was a twink#Sun Ra is experimental#Pharaoh Sanders is similar to Sun Ra (both are mystical and psychedelic) but Pharaoh Sanders is more well known#Alice Coltrane made an album called journey to Satchinada or wjatever#Phelonous Monk makea very#very normal jazz#Peter Brotzmann makes incrediblt harsh jazz#Joao Gilberto has very dorky vibes#Wayne Shorter is incredibly non descript. Zero defining features as an artist#Duke Ellington is old#Ryo Fukuri is popular with the kids and people on 4chan#Max Roach was famous for his protest music#so a fan of his would have the balls to correct me on my error#Charles Mingus has a funny name#John Coltrane is the third most famous jazzer (arguably) and getting kicked out of whole foods is a national past time#I really like Art Blakey#but he’s also very nondescript#I forgot about Herbie Hancock#Kamasi Washington and Moondog had to be kicked out for time#I don’t care about Cannonball Adderley or Sonny Rollis#And while you could definetly count him as jazz#I didn’t feel right including Frank Zappa on here#as that would open a door that might not be closable

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I have a recollection of singing "The Banana Boat Song" and "Jamaica Farewell" in school as a kid; that's how embedded in my life Harry Belafonte was.

Before all that, of course, he had already lived a remarkable life. Getting into music to get a little spare cash to support a kick-around early career as an actor, when Lester Young recommended him to Monte Kay and had the greatest first-gig backing band in history, famously accompanied by Charlie Parker, Al Haig, Tommy Potter, and Max Roach. His career was amazing, popularizing Calypso for an American audience, winning a Tony, a film career that went from starring in "Carmen Jones" to his role in "BlacKKKlansman." I don't even know what else you would throw in the topline: singing at JFK's inauguration, maybe the most famous Muppets sketch ever, guest-hosting The Tonight Show, being a Lifetime Grammy winner.

And that's before you get to him bankrolling and helping organize some of the most important civil rights protests of the early 60s. And that was a light he carried throughout his life; the guy who starred in an Otto Preminger film worked on humanitarian efforts in Africa well into the 21st century.

(via Harry Belafonte, 96, Dies; Barrier-Breaking Singer, Actor and Activist - The New York Times)

Harry Belafonte, who stormed the pop charts and smashed racial barriers in the 1950s with his highly personal brand of folk music, and who went on to become a dynamic force in the civil rights movement, died on Tuesday at his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. He was 96.

also: that mic

578 notes

·

View notes

Text

Concerning Jazz Music

A complex debate

An important debate about jazz music affects the question of its ethnicity and its history. As jazz began to develop at the turn of the twentieth century, many people wondered how it would influence representations of white people about the African American community - with which jazz was usually associated. For some African-Americans, jazz music highlighted the contribution of black people to American culture and society, and has drawn attention to black history and culture. Others believe that music and the term “jazz” are reminiscent of an oppressive and racist society, which restricts the freedom of black people.

The various forms of music developed by enslaved Africans in North American and their descendants were rooted in Africa, particularly West Africa. There are several music behind jazz. The music genre was born from the work songs of the slaves. It also includes the music later known as the blues, which expressed hopes and pains of people. Moreover, St. Louis had been a center of ragtime, one of the musical tributaries of jazz music, at the beginning of the century. “Jazz,” according to the pianist Dave Brubeck (speaking in 1950) was “born in New Orleans about 1880” consisting of “an improvised musical expression based on European harmony and African rhythms.”

The term of « jazz » has a contested employment. The musician Max Roach didn’t accept the word : in 1972, he said that he prefered to describe the music as « the culture of African people who have been dispersed throughout North America […] jazz meant the worst kind of working conditions, the worst in cultural prejudice, the worst kind of salaries and conditions that one can imagine … the abuse and exploitation of black musicians ». Later, it was the turn of Artie Shaw : in 1992, he said that the word « jazz » was ridiculous. Archie Shepp also explained to Franck Cassenti in Je suis Jazz that he didn’t like the word neither. Whatever the case, it appears that the first authenticated appearance of the word “jazz” in print was in a newspaper, the San Francisco Call, on 6 March 1913. Originally, the term used to describe this music was associated with sex, and it was seen as a negative connotation.

New Orleans is famous because it’s the place where brass bands were born . The first jazz recording was released in March 1917 by the Original Dixieland Jass Band, an orchestra composed exclusively of white musicians. The pianist Jelly Roll Morton calls himself "inventor of jazz". If he’s indeed a ferryman between ragtime and jazz, it’s Sidney Bechet and especially Louis Armstrong who stand out as the great soloists of the New Orleans bands, characterized by collective improvisation. Jazz categories include Dixieland, swing, bop, cool jazz, hard bop, free jazz, jazz-rock, and fusion. The first jazz-style to receive recognition as a fine art was bebop, which is mainly instrumental and was formed by black jazz musicians during the late night jam sessions. Bebop evolved in the 1940s and was said to have been created by blacks in a way that whites could not copy.

Until recently, the question of the "belonging" of jazz music to white musicians or black musicians has been highlighted by actual jazz musicians. For example, Jacob Collier published on his Instagram account these words (on June 2020):

In the past few days, I have seen just how much power a white voice like mine has to detract from the truth and contribute to the noise, but what I can say with certainty is this : racism is a problem – in the UK, in the USA, ans across the world at large. Those who deny this, and are unwilling to engage with it, are the fabric of the probleme. As a white musician, I walk a path each and every day that has been trail-blazed, paved and illuminated by the colossal, unshakable legacy of black musicians stretching generations before me : the master alchemists, who transformed unspeakable suffering into everlasting power and music.

In the same way, another famous white musician, Jamie Cullum, wrote this, also on June 2020:

I remember when Twentysomething came out in 2004 I used to receive a lot of old fashioned paper mail. There was one short letter that asked me to consider what it meant to be a non-black musician, profiting off of generations of black artistry and culture. The reason I bring it up now is because I remember so clearly how it wasn’t a conversation I was ready to have with myself, as a 23 year old. But these are exactly the kinds of conversations that need to be had by people like myself, by all of us, however uncomfortable.

Both of them underlined that the soul of this music is connected to the roots of the generation that came before us. They explain how it’s important to considere the complexity of this culture and the history.carried for years. It’s important to not avoid or erase the question for the next generation. Of course, jazz music has created a sense of fellowship between black and white musicians. White musicians were hired to perform with several black bands (for example, Roswell Rudd was introduced to jazz audiences by Archie Shepp). It has not only integrated people in the United States but also brought them together, in the entire world, integrating international ideas into the music. But discrimination has existed, and still is.

Social effects of jazz music

In the 1920s, jazz became popular when the music began to spread through recordings. Some black jazz musicians believed that they didn’t get full recognition and compensation for being the inventors of jazz as African American culture. Furthermore, some people oppose the idea that jazz was invented by blacks.

Gradually, opportunities were given to black musicians by the radio and recording industry. Popular black bands were promoted as long as there was a demand for jazz music by white Americans. Some of these jazzmen (and women singers) received recognition as serious artists and several were invited to give concerts in Carnegie Hall, but still encountered criticism and racism. To some extent, jazz music would not have been widely distributed to the general public without the recording industry. However, black jazz musicians were less credited for their innovation of jazz music.

Many musicians expressed their demand for identity, self-expression and community, participating to the « Black Arts Movement » in the 60’s and rejecting the white western gaze. It consists on using slang in literature, the orality rhythm of the blues or the gospel in music. They fight for the destruction of racist stereotypes and some of them conceptualized the « blacknes ».

Artists’ voices in the Civil Rights Movement

In 1939, Billie Holiday’s rendition of Abel Meeropol’s poem, Strange Fruit, described the horrors of Jim Crow ‘s era lynching. The song is often considered as the first and most influential jazz protest song.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit Blood on the leaves and blood at the root Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant South The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth Scent of magnolia, sweet and fresh Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop Here is a strange and bitter crop

youtube

Decades later, while governments and individueals attempted to silence the black political voice, jazz became a way of deep expression. Many jazz musicians became outspoken activists, they made their voices heard and started creating soundtracks to support the Civil Rights movement. Indeed, huge cultural and political shifts were underway in the form of the civil rights movement, which sought to break down the existing social order. Evolving in parallel by similar cultural and historical questions, the civil rights and jazz movements (especially the avant-garde) influenced each other.

John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, Nina Simone and some jazz pioneers made their voices heard during the civil rights movement. For instance, Coltrane was deeply involved in the movement and shared many of Malcolm X’s views on black consciousness and pan-Africanism, which he incorporated into his music. In the 60’s, he was at the height of his career. He performed a song (in fact, a dirge) in 1963, called Alabama, to mourn the Birmingham church bombing that took the lives of four little girls.

In 1964, Nina Simone sang the incendiary song Mississippi Goddam (responded to the 1963 murder of an activist, Megdar Evers) in front of a white audience at Carnegie Hall. The song starts off as a jaunty musical tune, before it evolves into an documentation of racial inequality in the South. In the recording, we can understand that the atmosphere of the concert is changing, as the public realize the intentions of the song. She used her lyrics to prolong her political commitment. She has also composed another famous song, Four Women : it highlight four specific stereotypes about black women.

youtube

Charles Mingus, for his part, wrote a song called Fables of Faubus about Orval Faubus, a racist governor of Arkansas, who infamously ordered the Arkansas National Guard to prevent black students from enrolling at Central High School in 1956. Mingus’ record label, Columbia, felt the lyrics were too incendiary, so he released the full version of the song on a record for another label.

To conclude this theme, I want to share an excerpt written by Dr. Martin Luther Link about jazz, for the Berlin Jazz Festival, in 1964 :

“God has wrought many things out of oppression. God has endowed creatures with the capacity to create-and from this capacity has flowed the sweet songs of sorrow and joy that have allowed humanity to cope with the environment and many different situations. Jazz speaks for life. The Blues tell the story of life’s difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realize that they take the hardest realities of life and put them to music, only to come out with some new hope and sense of triumph. This is triumphant music.”

This quote, from one of the most important figure of the Civil Rights Movement, underlines how jazz music has been a powerful form of art, but also a very political one, fighting against racism and advocating social, economic and political equality.

Anne Vinet

0 notes

Text

Harry Belafonte

Harry Belafonte (born March 1, 1927) is an American singer, songwriter, actor, and social activist. One of the most successful African-American pop stars in history, he was dubbed the "King of Calypso" for popularizing the Caribbean musical style with an international audience in the 1950s. His breakthrough album Calypso (1956) is the first million selling LP by a single artist. Belafonte is perhaps best known for singing "The Banana Boat Song", with its signature lyric "Day-O". He has recorded in many genres, including blues, folk, gospel, show tunes, and American standards. He has also starred in several films, most notably in Otto Preminger's hit musical Carmen Jones (1954), Island in the Sun (1957) and Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow (1959).

Belafonte was an early supporter of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, and one of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s confidants. Throughout his career he has been an advocate for political and humanitarian causes, such as the anti-apartheid movement and USA for Africa. Since 1987 he has been a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador. In recent years he has been a vocal critic of the policies of both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama presidential administrations. Harry Belafonte now acts as the American Civil Liberties Union celebrity ambassador for juvenile justice issues.

Belafonte has won three Grammy Awards, including a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, an Emmy Award, and a Tony Award. In 1989 he received the Kennedy Center Honors. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994. In 2014, he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the Academy’s 6th Annual Governors Awards. In March 2014, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Berklee College of Music in Boston.

Early life

Belafonte was born Harold George Bellanfanti, Jr. at Lying-in Hospital on March 1, 1927, in Harlem, New York, the son of Melvine (née Love), a housekeeper of Jamaican descent, and Harold George Bellanfanti, Sr., a Martiniquan who worked as a chef. His mother was born in Jamaica, the child of a Scottish white mother and a black father. His father also was born in Jamaica, the child of a black mother and Dutch Jewish father of Sephardi origins. This is all Harry says about his Jewish grandfather, whom he never met: “a white Dutch Jew who drifted over to the islands after chasing gold and diamonds, with no luck at all”. From 1932 to 1940, he lived with his grandmother in her native country of Jamaica. When he returned to New York City, he attended George Washington High School after which he joined the Navy and served during World War II. In the 1940s, he was working as a janitor's assistant in NYC when a tenant gave him, as a gratuity, two tickets to see the American Negro Theater. He fell in love with the art form and also met Sidney Poitier. The financially struggling pair regularly purchased a single seat to local plays, trading places in between acts, after informing the other about the progression of the play. At the end of the 1940s, he took classes in acting at the Dramatic Workshop of The New School in New York with the influential German director Erwin Piscator alongside Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Walter Matthau, Bea Arthur and Sidney Poitier, while performing with the American Negro Theatre. He subsequently received a Tony Award for his participation in the Broadway revue John Murray Anderson's Almanac.

Music career

Belafonte started his career in music as a club singer in New York to pay for his acting classes. The first time he appeared in front of an audience, he was backed by the Charlie Parker band, which included Charlie Parker himself, Max Roach and Miles Davis, among others. At first he was a pop singer, launching his recording career on the Roost label in 1949, but later he developed a keen interest in folk music, learning material through the Library of Congress' American folk songs archives. With guitarist and friend Millard Thomas, Belafonte soon made his debut at the legendary jazz club The Village Vanguard. In 1952 he received a contract with RCA Victor.

Calypso

His first widely released single, which went on to become his "signature" song with audience participation in virtually all his live performances, was "Matilda", recorded April 27, 1953. His breakthrough album Calypso (1956) became the first LP in the world "to sell over 1 million copies within a year", Belafonte said on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's The Link program on August 7, 2012. He added that it was also the first million-selling album ever in England. The album is number four on Billboard's "Top 100 Album" list for having spent 31 weeks at number 1, 58 weeks in the top ten, and 99 weeks on the U.S. charts. The album introduced American audiences to calypso music (which had originated in Trinidad and Tobago in the early 20th century), and Belafonte was dubbed the "King of Calypso", a title he wore with reservations, since he had no claims to any Calypso Monarch titles.

One of the songs included in the album is the now famous "Banana Boat Song" (listed as "Day O" on the original release), which reached number five on the pop charts, and featured its signature lyric "Day-O". His other smash hit was "Jump in the Line".

Many of the compositions recorded for Calypso, including "Banana Boat Song" and "Jamaica Farewell", gave songwriting credit to Irving Burgie.

Middle career

While primarily known for calypso, Belafonte has recorded in many different genres, including blues, folk, gospel, show tunes, and American standards. His second-most popular hit, which came immediately after "The Banana Boat Song", was the comedic tune "Mama Look at Bubu", also known as "Mama Look a Boo-Boo" (originally recorded by Lord Melody in 1955), in which he sings humorously about misbehaving and disrespectful children. It reached number eleven on the pop chart.

In 1959, he starred in Tonight With Belafonte, a nationally televised special that featured Odetta, who sang "Water Boy" and who performed a duet with Belafonte of "There's a Hole in My Bucket" that hit the national charts in 1961. Belafonte was the first African American to win an Emmy, for Revlon Revue: Tonight with Belafonte (1959). Belafonte recorded for RCA Victor from 1953 to 1974. Two live albums, both recorded at Carnegie Hall in 1959 and 1960, enjoyed critical and commercial success. From his 1959 album, "Hava Nagila" became part of his regular routine and one of his signature songs. He was one of many entertainers recruited by Frank Sinatra to perform at the inaugural gala of President John F. Kennedy in 1961. That same year he released his second calypso album, Jump Up Calypso, which went on to become another million seller. During the 1960s he introduced several artists to American audiences, most notably South African singer Miriam Makeba and Greek singer Nana Mouskouri. His album Midnight Special (1962) featured the first-ever record appearance by a young harmonica player named Bob Dylan.

As The Beatles and other stars from Britain began to dominate the U.S. pop charts, Belafonte's commercial success diminished; 1964's Belafonte at The Greek Theatre was his last album to appear in Billboard's Top 40. His last hit single, "A Strange Song", was released in 1967 and peaked at number 5 on the Adult contemporary music charts. Belafonte has received Grammy Awards for the albums Swing Dat Hammer (1960) and An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba (1965). The latter album dealt with the political plight of black South Africans under apartheid. He earned six Gold Records.

During the 1960s he appeared on TV specials alongside such artists as Julie Andrews, Petula Clark, Lena Horne and Nana Mouskouri. In 1967, Belafonte was the first non-classical artist to perform at the prestigious Saratoga Performing Arts Center (SPAC) in Upstate New York, soon to be followed by concerts there by The Doors, The 5th Dimension, The Who and Janis Joplin.

From February 5 to 9, 1968, Belafonte guest hosted The Tonight Show substituting for Johnny Carson. Among his interview guests were Martin Luther King, Jr and Sen.Robert F. Kennedy.

Later recordings and other activities

Belafonte's recording activity slowed after he left RCA in the mid-1970s. RCA released his fifth and final Calypso album, Calypso Carnival in 1971. From the mid-1970s to early 1980s Belafonte spent the greater part of his time touring Japan, Europe, Cuba and elsewhere. In 1977, he released the album Turn the World Around on the Columbia Records label. The album, with a strong focus on world music, was never issued in the United States. He subsequently was a guest star on a memorable episode of The Muppet Show in 1978, in which he performed his signature song "Day-O" on television for the first time. However, the episode is best known for Belafonte's rendition of the spiritual song "Turn the World Around", from the album of the same name, which he performed with specially made Muppets that resembled African tribal masks. It became one of the series' most famous performances. It was reportedly Jim Henson's favorite episode, and Belafonte reprised the song at Henson's memorial in 1990. "Turn the World Around" was also included in the 2005 official hymnal supplement of the Unitarian Universalist Association, Singing the Journey.

His involvement in USA for Africa during the mid-1980s resulted in renewed interest in his music, culminating in a record deal with EMI. He subsequently released his first album of original material in over a decade, Paradise in Gazankulu, in 1988. The album contains ten protest songs against the South African former Apartheid policy and is his last studio album. In the same year Belafonte, as UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, attended a symposium in Harare, Zimbabwe, to focus attention on child survival and development in Southern African countries. As part of the symposium, he performed a concert for UNICEF. A Kodak video crew filmed the concert, which was released as a 60-minute concert video titled "Global Carnival". It features many of the songs from the album Paradise in Gazankulu and some of his classic hits. Also in 1988, Tim Burton used "The Banana Boat Song" and "Jump in the Line" in his movie Beetlejuice.

Following a lengthy recording hiatus, An Evening with Harry Belafonte and Friends, a soundtrack and video of a televised concert, were released in 1997 by Island Records. The Long Road to Freedom: An Anthology of Black Music, a huge multi-artist project recorded by RCA during the 1960s and 1970s, was finally released by the label in 2001. Belafonte went on the Today Show to promote the album on September 11, 2001, and was interviewed by Katie Couric just minutes before the first plane hit the World Trade Center. The album was nominated for the 2002 Grammy Awards for Best Boxed Recording Package, for Best Album Notes and for Best Historical Album.

Belafonte received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1989. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994 and he won a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000. He performed sold-out concerts globally through the 1950s to the 2000s. Owing to illness, he was forced to cancel a reunion tour with Nana Mouskouri planned for the spring and summer of 2003 following a tour in Europe. His last concert was a benefit concert for the Atlanta Opera on October 25, 2003. In a 2007 interview he stated that he had since retired from performing.

Film career

Belafonte has starred in several films. His first film role was in Bright Road (1953), in which he appeared alongside Dorothy Dandridge. The two subsequently starred in Otto Preminger's hit musical Carmen Jones (1954). Ironically, Belafonte's singing in the film was dubbed by an opera singer, as Belafonte's own singing voice was seen as unsuitable for the role. Using his star clout, Belafonte was subsequently able to realize several then-controversial film roles. In 1957's Island in the Sun, there are hints of an affair between Belafonte's character and the character played by Joan Fontaine. The film also starred James Mason, Dandridge, Joan Collins, Michael Rennie and John Justin. In 1959, he starred in and produced Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow, in which he plays a bank robber uncomfortably teamed with a racist partner (Robert Ryan). He also co-starred with Inger Stevens in The World, the Flesh and the Devil. Belafonte was offered the role of Porgy in Preminger's Porgy and Bess, where he would have once again starred opposite Dandridge, but he refused the role because he objected to its racial stereotyping.

Dissatisfied with the film roles available to him, he returned to music during the 1960s. In the early 1970s Belafonte appeared in more films among which are two with Poitier: Buck and the Preacher (1972) and Uptown Saturday Night (1974). In 1984 Belafonte produced and scored the musical film Beat Street, dealing with the rise of hip-hop culture. Together with Arthur Baker, he produced the gold-certified soundtrack of the same name. Belafonte next starred in a major film again in the mid-1990s, appearing with John Travolta in the race-reverse drama White Man's Burden (1995); and in Robert Altman's jazz age drama Kansas City (1996), the latter of which garnered him the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Supporting Actor. He also starred as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States in the TV drama Swing Vote (1999). In 2006, Belafonte appeared in Bobby, Emilio Estevez's ensemble drama about the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy; he played Nelson, a friend of an employee of the Ambassador Hotel (Anthony Hopkins).

Personal life

Belafonte and Marguerite Byrd were married from 1948 to 1957. They have two daughters: Adrienne and Shari. Shari Belafonte, married to Sam Behrens, is a photographer, model, singer and actress. In 1997 Adrienne Biesemeyer and her daughter Rachel Blue founded the Anir Foundation/Experience. Anir focuses on humanitarian work in southern Africa.

On March 8, 1957, Belafonte married his second wife Julie Robinson, a former dancer with the Katherine Dunham Company. They had two children, David and Gina Belafonte. David Belafonte, a former model and actor, is an Emmy-winning producer and the executive director of the family-held company Belafonte Enterprises Inc. A music producer, he has been involved in most of Belafonte's albums and tours. David married Danish model, singer and TV personality Malena Mathiesen, who won silver in Dancing with the Stars in Denmark in 2009. Malena Belafonte founded Speyer Legacy School, a private elementary school for gifted and talented children. David and Malena's daughter Sarafina attended this school. Gina Belafonte is a TV and film actress and worked with her father as coach and producer on more than six films. Gina helped found The Gathering For Justice, an intergenerational, intercultural non-profit organization working to reintroduce nonviolence to stop child incarceration. She is married to actor Scott McCray.

At some point, Belafonte and Robinson divorced. In April 2008, Belafonte married photographer Pamela Frank. In October 1998, Belafonte contributed a letter to Liv Ullmann's book Letter to My Grandchild.

On January 29, 2013, Belafonte was the Keynote Speaker and 2013 Honoree for the MLK Celebration Series at the Rhode Island School of Design. Belafonte used his career and experiences with Dr. King to speak on the role of artists as activists.

Belafonte was inducted as an honorary member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity on January 11, 2014.

Political and humanitarian activism

Belafonte's political beliefs were greatly inspired by the singer, actor and Communist activist Paul Robeson, who mentored him. Robeson opposed not only racial prejudice in the United States, but also western colonialism in Africa. Belafonte's success did not protect him from criticism of his communist sympathies or from racial discrimination, particularly in the American South. He refused to perform there from 1954 until 1961. In 1960 he appeared in a campaign commercial for Democratic Presidential candidate John F. Kennedy. Kennedy later named Belafonte cultural advisor to the Peace Corps.

Belafonte gave the keynote address at the ACLU of Northern California's annual Bill of Rights Day Celebration In December 2007 and was awarded the Chief Justice Earl Warren Civil Liberties Award. The 2011 Sundance Film Festival featured the documentary film Sing Your Song, a biographical film focusing on Belafonte's contribution to and his leadership in the civil rights movement in America and his endeavours to promote social justice globally. In 2011, Belafonte's memoir My Song was published by Knopf Books.

Civil Rights Movement activist

Belafonte supported the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s and was one of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s confidants. He provided for King's family, since King made only $8,000 a year as a preacher. Like many other civil rights activists, Belafonte was blacklisted during the McCarthy era. During the 1963 Birmingham Campaign he bailed King out of Birmingham City Jail and raised thousands of dollars to release other civil rights protesters. He financed the 1961 Freedom Rides, supported voter registration drives, and helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington.

During the Mississippi Freedom Summer" of 1964 Belafonte bankrolled the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, flying to Mississippi that August with Sidney Poitier and $60,000 in cash and entertaining crowds in Greenwood. In 1968 Belafonte appeared on a Petula Clark primetime television special on NBC. In the middle of a duet of On the Path of Glory, Clark smiled and briefly touched Belafonte's arm, which prompted complaints from Doyle Lott, the advertising manager of the show's sponsor, Plymouth Motors. Lott wanted to retape the segment, but Clark, who had ownership of the special, told NBC that the performance would be shown intact or she would not allow the special to be aired at all. Newspapers reported the controversy, Lott was relieved of his responsibilities, and when the special aired, it attracted high ratings.

Belafonte appeared on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour on September 29, 1968, performing a controversial "Mardi Gras" number intercut with footage from the 1968 Democratic National Convention riots. CBS censors deleted the segment. The full unedited content were broadcast in 1993 as part of a complete Smothers Brothers Hour syndication package.

Humanitarian activist

In 1985, he helped organize the Grammy Award-winning song "We Are the World", a multi-artist effort to raise funds for Africa. He performed in the Live Aid concert that same year. In 1987, he received an appointment to UNICEF as a goodwill ambassador. Following his appointment Belafonte traveled to Dakar, Senegal, where he served as chairman of the International Symposium of Artists and Intellectuals for African Children. He also helped to raise funds—alongside more than 20 other artists—in the largest concert ever held in sub-Saharan Africa. In 1994, he went on a mission to Rwanda and launched a media campaign to raise awareness of the needs of Rwandan children.

In 2001, he went to South Africa to support the campaign against HIV/AIDS. In 2002, Africare awarded him the Bishop John T. Walker Distinguished Humanitarian Service Award for his efforts to assist Africa. In 2004, Belafonte went to Kenya to stress the importance of educating children in the region.

Belafonte has been involved in prostate cancer advocacy since 1996, when he was diagnosed and successfully treated for the disease. On June 27, 2006, Belafonte was the recipient of the BET Humanitarian Award at the 2006 BET Awards. He was named one of nine 2006 Impact Award recipients by AARP The Magazine. On October 19, 2007, Belafonte represented UNICEF on Norwegian television to support the annual telethon (TV Aksjonen) in support of that charity and helped raise a world record of $10 per inhabitant of Norway. Belafonte was also an ambassador for the Bahamas. He is on the board of directors of the Advancement Project. He also serves on the Advisory Council of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation.

Political activist

Belafonte has been a longtime critic of U.S. foreign policy. He began making controversial political statements on this subject in the early 1980s. He has at various times made statements opposing the U.S. embargo on Cuba; praising Soviet peace initiatives; attacking the U.S. invasion of Grenada; praising the Abraham Lincoln Brigade; honoring Ethel and Julius Rosenberg and praising Fidel Castro. Belafonte is additionally known for his visit to Cuba which helped ensure hip-hop's place in Cuban society. According to Geoffrey Baker's article "Hip hop, Revolucion! Nationalizing Rap in Cuba", in 1999 Belafonte met with representatives of the rap community immediately before meeting with Fidel Castro. This meeting resulted in Castro’s personal approval of, and hence the government’s involvement in, the incorporation of rap into his country's culture. In a 2003 interview, Belafonte reflected upon this meeting’s influence:

“When I went back to Havana a couple years later, the people in the hip-hop community came to see me and we hung out for a bit. They thanked me profusely and I said, 'Why?' and they said, 'Because your little conversation with Fidel and the Minister of Culture on hip-hop led to there being a special division within the ministry and we've got our own studio'."

Belafonte was active in the anti-apartheid movement. He was the Master of Ceremonies at a reception honoring African National Congress President Oliver Tambo at Roosevelt House, Hunter College, in New York City. The reception was held by the American Committee on Africa (ACOA) and The Africa Fund. He is a current board member of the TransAfrica Forum and the Institute for Policy Studies.

Opposition to the George W. Bush administration

Belafonte achieved widespread attention for his political views in 2002 when he began making a series of comments about President George W. Bush, his administration and the Iraq War. During an interview with Ted Leitner for San Diego's 760 KFMB, in October 2002, Belafonte referred to a quote made by Malcolm X. Belafonte said:

There is an old saying, in the days of slavery. There were those slaves who lived on the plantation, and there were those slaves who lived in the house. You got the privilege of living in the house if you served the master, do exactly the way the master intended to have you serve him. That gave you privilege. Colin Powell is committed to come into the house of the master, as long as he would serve the master, according to the master's purpose. And when Colin Powell dares to suggest something other than what the master wants to hear, he will be turned back out to pasture. And you don't hear much from those who live in the pasture.

Belafonte used the quote to characterize former United States Secretaries of State Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice, both African Americans. Powell and Rice both responded, with Powell calling the remarks "unfortunate" and Rice saying: "I don't need Harry Belafonte to tell me what it means to be black."

The comment was brought up again in an interview with Amy Goodman for Democracy Now! in 2006. In January 2006, Belafonte led a delegation of activists including actor Danny Glover and activist/professor Cornel West to meet with President of Venezuela Hugo Chávez. In 2005 Chávez, an outspoken Bush critic, initiated a program to provide cheaper heating oil for poor people in several areas of the United States. Belafonte supported this initiative. He was quoted as saying, during the meeting with Chávez, "No matter what the greatest tyrant in the world, the greatest terrorist in the world, George W. Bush says, we're here to tell you: Not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of the American people support your revolution." Belafonte and Glover met again with Chávez in 2006. The comment ignited a great deal of controversy. Hillary Clinton refused to acknowledge Belafonte's presence at an awards ceremony that featured both of them. AARP, which had just named him one of its 10 Impact Award honorees 2006, released this statement following the remarks: "AARP does not condone the manner and tone which he has chosen and finds his comments completely unacceptable." During a Martin Luther King, Jr. Day speech at Duke University in 2006, Belafonte compared the American government to the hijackers of the September 11 attacks, saying: "What is the difference between that terrorist and other terrorists?" In response to criticism about his remarks Belafonte asked, "What do you call Bush when the war he put us in to date has killed almost as many Americans as died on 9/11 and the number of Americans wounded in war is almost triple? [...] By most definitions Bush can be considered a terrorist." When he was asked about his expectation of criticism for his remarks on the war in Iraq, Belafonte responded: "Bring it on. Dissent is central to any democracy."

In another interview Belafonte remarked that while his comments may have been "hasty", nevertheless he felt the Bush administration suffered from "arrogance wedded to ignorance" and its policies around the world were "morally bankrupt". In January 2006, in a speech to the annual meeting of the Arts Presenters Members Conference, Belafonte referred to "the new Gestapo of Homeland Security" saying, "You can be arrested and have no right to counsel!" During the Martin Luther King, Jr. Day speech at Duke University in January 2006, Belafonte said that if he could choose his epitaph it would be, "Harry Belafonte, Patriot."

In 2004, he was awarded the Domestic Human Rights Award in San Francisco by Global Exchange.

Obama administration

In 2011, he commented on the Obama administration and the role of popular opinion in shaping its policies. "I think [Obama] plays the game that he plays because he sees no threat from evidencing concerns for the poor."

On December 9, 2012, in an interview with Al Sharpton on MSNBC, Belafonte expressed dismay that many political leaders in the United States continue to oppose the policies of President Obama even after his re-election: "The only thing left for Barack Obama to do is to work like a third-world dictator and just put all of these guys in jail. You’re violating the American desire."

On February 1, 2013, Belafonte received the NAACP's Spingarn Medal, and in the televised ceremony, he counted Constance L. Rice among those previous recipients of the award whom he regarded highly for speaking up "to remedy the ills of the nation".

NYC Pride

In 2013, he was named a Grand Marshal of the New York City Pride Parade, alongside Edie Windsor and Earl Fowlkes.

2016 Election

In 2016, Belafonte endorsed Bernie Sanders for the Democratic Primary, saying "I think he represents opportunity, I think he represents a moral imperative, I think he represents a certain kind of truth that's not often evidenced in the course of politics".

Belafonte is an honorary co-chair of the Women's March on Washington, which took place on January 21, 2017, the day after the inauguration of Donald Trump as President.

Discography

Filmography

Bright Road (1953)

Carmen Jones (1954)

Island in the Sun (1957)

The Heart of Show Business (1957) (short subject)

The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959)

Odds Against Tomorrow (1959)

King: A Filmed Record... Montgomery to Memphis (1970) (documentary) (narrator)

The Angel Levine (1970)

Buck and the Preacher (1972)

Uptown Saturday Night (1974)

Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker (1981) (documentary)

A veces miro mi vida (1982)

Drei Lieder (1983) (short subject)

Sag nein (1983) (documentary)

Der Schönste Traum (1984) (documentary)

We Shall Overcome (1989) (documentary) (narrator)

The Player (1992) (Cameo)

Ready to Wear (1994) (Cameo)

Hank Aaron: Chasing the Dream (1995)

White Man's Burden (1995)

Jazz '34 (1996)

Kansas City (1996)

Scandalize My Name: Stories from the Blacklist (1998) (documentary)

Fidel (2001) (documentary)

XXI Century (2003) (documentary)

Conakry Kas (2003) (documentary)

Ladders (2004) (documentary) (narrator)

Mo & Me (2006) (documentary)

Bobby (2006)

Motherland (2009) (documentary)

Sing Your Song (2011) (documentary)

Hava Nagila: The Movie (2013) (documentary)

Television work

Sugar Hill Times (1949–1950)

The Steve Allen Show (1958)

Tonight With Belafonte (1959)

1963 Round Table (1963)

Petula (1968)

"The Tonight Show" (1968)

A World in Music (1969)

Harry & Lena, For The Love Of Life (1969)

A World in Love (1970)

The Flip Wilson Show (1973)

Free to Be… You and Me (1974)

The Muppet Show (1978)

Grambling's White Tiger (1981)

Don't Stop The Carnival (1985)

After Dark (1989) (extended appearance on political discussion programme, more here)

An Evening With Harry Belafonte And Friends (1997)

Swing Vote (1999)

PB&J Otter "The Ice Moose" (1999)

Tanner on Tanner (2004)

That's What I'm Talking About (2006) (miniseries)

When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006) (miniseries)

Speakeasy, interviewing Carlos Santana (2015)

Concert videos

En Gränslös Kväll På Operan (1966)

Don't Stop The Carnival (1985)

Global Carnival (1988)

An Evening With Harry Belafonte And Friends (1997)

Stage work

John Murray Anderson's Almanac (1953)

3 for Tonight (1955)

Moonbirds (1959) (producer)

Belafonte at the Palace (1959)

Asinamali! (1987) (producer)

Wikipedia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jazz Artists in the Civil Rights Era

“John Coltrane, Max Roach, Nina Simone, Charlie Mingus, Cal Massey, and Archie Shepp. Nat Hentoff, a politically-engaged and prolific writer and columnist, ran the Candid Records label, which issued a famous Max Roach album with lunch-counter protest cover art called “We Insist!“. Nina Simone sang the incendiary “Mississippi Goddam.”

Coltrane performed a sad dirge, “Alabama” to mourn the Birmingham, Alabama church bombing in 1963. Sonny Rollins recorded The Freedom Suite for Riverside Records as a declaration of musical and racial freedom.Charles Mingus, for his part, wrote a song called, “Fables of Faubus,” about the racist governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus who infamously ordered the Arkansas National Guard to prevent black students from enrolling at Central High School in 1956.

Finally, there was Cal Massey, a trumpeter-composer who wrote an extended work commissioned by the Black Panther Party called The Black Liberation Movement Suite. Parts of the Suite were recorded by Archie Shepp, but amazingly, it was never recorded in its entirely until 2011. Massey’s music was for a period blacklisted. Let’s not forget Oscar Brown Jr.’s witty song, “Forty Acres and a Mule” from his 1965 album Mr. Oscar Brown Jr. Goes to Washington. It superbly catalogues promises made but never delivered.“

Written by Tom Schnabel Jan. 16, 2017

0 notes

Text

Ridgefield resident, jazz musician David Watson shares his experiences, talent in film, with band

Find out how to get the best plumber in Vancouver Washington

RIDGEFIELD — David Watson is the kind of guy who calls his buddies “cats.”

Cats like Dizzy and Miles. Monk and Hawk. Nat and Frank. Watson met all those famous cats, he said, and played or sang with many of them. The one jazz legend he really wished he had met, but never did, was Ella Fitzgerald.

Watson was just a child, growing up with a singing father in a musical household, when he heard Fitzgerald’s peerlessly acrobatic scat singing. Scat singing means transforming your voice into something like a saxophone and bebopping your way all over a melody, just like an instrumental soloist. Fitzgerald’s famously fast, fearless, joyous jazz explorations inspired Watson’s own scat singing as he grew into the nickname he now wears proudly: “The Doctor of Bebop.”

Watson grew up in Philadelphia, served in the Army, returned and tended bar at the downtown Showboat Jazz Theater. It was the chance of a lifetime, he said, where he not only hobnobbed or jammed with all those jazz cats, he even stole some moments behind their drum kits.

Some of the greatest drummers on the planet — Max Roach, Art Blakey, Tony Williams — “Anybody who played at the Showboat, I played their drums during the daytime,” Watson confesses in a short interview film made last year by Steve Anchell for the Northwest Jazz and Blues Project.

“I have great, warm, wonderful memories of some of the greatest musicians. I got to hang with them. It was a wonderful life,” he said.

Love and art

Wonderful but hard, too. Watson will discuss his philosophy of overcoming racism with love and art when he appears as guest speaker after a film called “Soundtrack for a Revolution” screens Wednesday at Ridgefield’s Old Liberty Theater.

“Soundtrack for a Revolution” is all about the music of the civil rights movement. It features historical film footage and performances by talents such as John Legend, Ritchie Havens, the Roots and the Blind Boys of Alabama. This free screening is part of Meaningful Movies, a Seattle-based effort to bring social-justice documentary films and discussions to neighborhood venues. In Ridgefield, pediatrician and mom Megan Dudley started bringing Meaningful Movies to the Old Liberty in 2017.

“I’ve been through the whole civil rights thing,” Watson said. “I went through extreme segregation. What helped a lot of us was the arts. Music has always been on the forefront of change, in this country and all over the world. When things need to be changed, music is there.”

Watson is still busy singing for social justice, he said. A few weeks ago he sang at a Portland rally to ban the sale of assault rifles. Guns were still on his mind when The Columbian visited his home the day before Valentine’s Day — which was also the day before the anniversary of the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida.

“Gun culture is killing our kids,” Watson said. “It needs to stop. Those kids from that school, the ones protesting — I love those kids.”

Cats and good old boys

Back in the day, one of those friendly jazz cats encouraged Watson to step out from behind the bar and take up both the microphone and the drums for real. Watson has been a professional jazz musician ever since, he said. His career has taken him all around the nation, and he’s always had a spiritual sense that wherever he lands, that’s where he’s meant to be.

He met his wife, Sarah, and started various music-related nonprofit projects while living for 18 years in Sonoma, Calif.; then he and Sarah took refuge from burnout with eight years of “spiritual healing” in Hawaii, he said. But he continued flying to the mainland to perform and record, he said — and it was during a layover in Portland that he discovered the jazz club Jimmy Mak’s, and Portland’s thriving jazz scene.

Watson struck up a warm, working friendship with the owner of Jimmy Mak’s — who died in 2016 — and he and Sarah started exploring real estate in Portland. After they discovered Oregon’s income tax, though, they wound up north of the border, near downtown Ridgefield.

Watson said they had the strong impression that their arrival in Ridgefield doubled the local African-American population — from two to four. “I was wondering, why am I here?” Watson confessed.

Ridgefield supplied the answer. One day Watson took his car to Bob’s Auto Shop downtown, and “up popped this friendship” with shop owner Bob Ford, he said. Ford is not the kind of guy who goes by “cat.”

“He’s a good old boy,” Watson laughed.

What they have in common, Watson said, is service to local veterans and others through the auto shop’s resident American Legion post, which Watson, a veteran, joined.

Some of the post members “are real right-wing, and some are as liberal as I am,” he said. “None of that matters. These guys are real genuine about service. I don’t go for all the flag waving, but I love the service.”

The new guy

Now that he’s in his 80s and supposedly retired, Watson is “working all the time,” he said gratefully. Watch for his gigs with Rebirthing the Cool, an 11-piece band, at Clyde’s Prime Rib Restaurant in Portland, the ilani resort and casino in Clark County and Christo’s Pizzeria and Lounge in Salem, Ore. Rebirthing the Cool also has a concert scheduled for May 24 at the historic Old Church in Portland.

“I’ve got this 11-member band with some of the best players in Portland — and around here, I’m just the new guy,” Watson said. “For a guy my age to be doing what I’m doing, it’s really something.”

If You Go

What: Screening of “Soundtrack to a Revolution,” with special guest Ridgefield resident David Watson, “The Doctor of Bebop.”

When: 7 p.m. Wednesday.

Where: Old Liberty Theater, 115 N. Main Ave., Ridgefield.

Admission: Free.

To Learn More

David Watson scat sings and reviews his life in a short film by Steve Anchell:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=LL9W5YbtKkA

Watson’s own website:

www.re-birthingthecool.com

[Read More …]

Find out how to get the best Vancouver Washington plumber

0 notes

Text

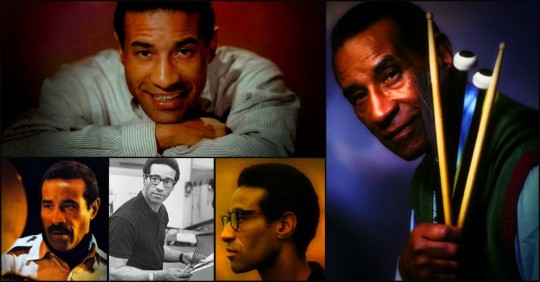

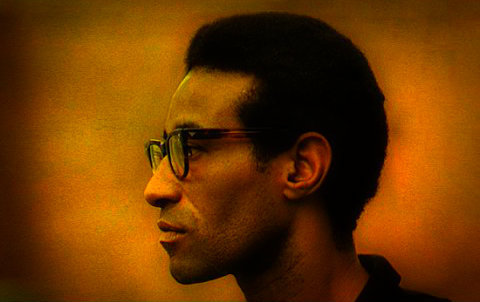

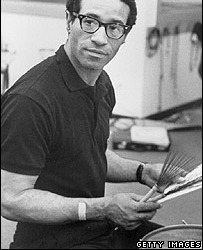

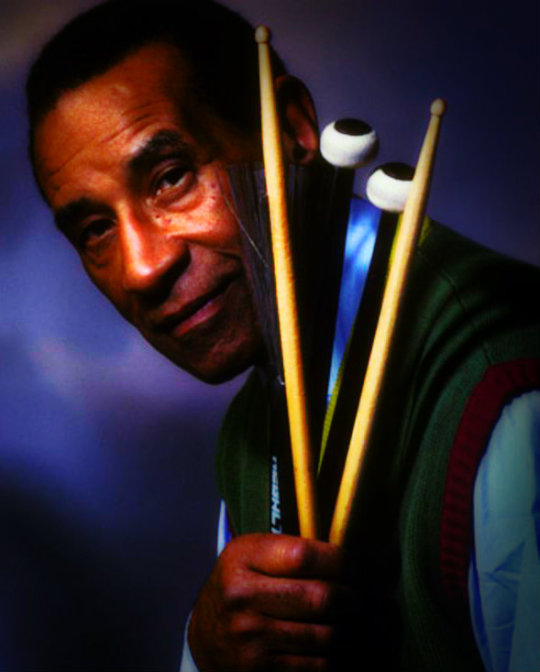

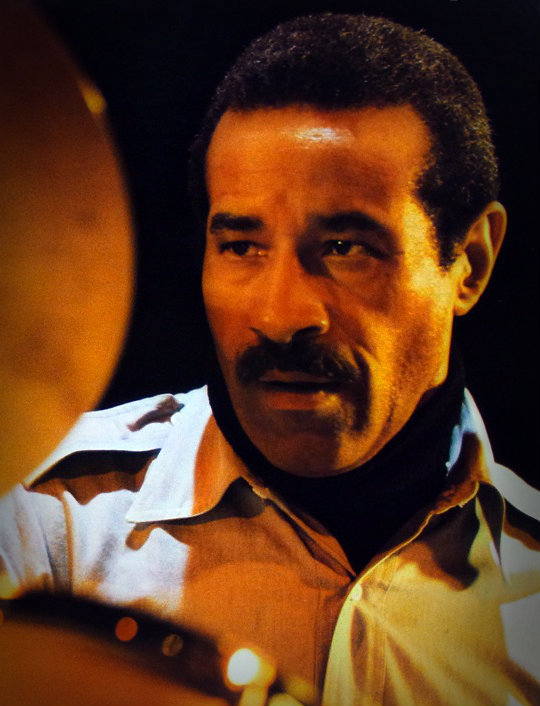

Max Roach

Maxwell Lemuel "Max" Roach (January 10, 1924 – August 16, 2007) was an American jazz percussionist, drummer, and composer.

A pioneer of bebop, Roach went on to work in many other styles of music, and is generally considered alongside the most important drummers in history. He worked with many famous jazz musicians, including Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Billy Eckstine, Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy and Booker Little. He was inducted into the Down Beat Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1992.

Roach also led his own groups, notably a pioneering quintet co-led with trumpeter Clifford Brown and the percussion ensemble M'Boom, and made numerous musical statements relating to the Civil Rights Movement.

Biography

Early life and career

Roach was born in the Township of Newland, Pasquotank County, North Carolina, which borders the southern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp, to Alphonse and Cressie Roach. Many confuse this with Newland Town in Avery County. Although Roach's birth certificate lists his date of birth as January 10, 1924, Roach has been quoted by Phil Schaap as having stated that his family believed he was born on January 8, 1925. Roach's family moved to the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York when he was 4 years old. He grew up in a musical home, his mother being a gospel singer. He started to play bugle in parade orchestras at a young age. At the age of 10, he was already playing drums in some gospel bands. In 1942, as an 18-year-old fresh out of Boys High School, he was called to fill in for Sonny Greer with the Duke Ellington Orchestra when they were performing at the Paramount Theater.

In 1942, Roach started to go out in the jazz clubs of the 52nd Street and at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay's Taproom (playing with schoolmate Cecil Payne). His first professional recording took place in December 1943, supporting Coleman Hawkins.

He was one of the first drummers (along with Clarke) to play in the bebop style, and performed in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis. Roach played on many of Parker's most important records, including the Savoy November 1945 session, a turning point in recorded jazz. The drummer's early brush work with Powell's trio, especially at fast tempos, has been highly praised.

1950s

Roach studied classical percussion at the Manhattan School of Music from 1950 to 1953, working toward a Bachelor of Music degree (the School awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in 1990).

In 1952, Roach co-founded Debut Records with bassist Charles Mingus. This label released a record of a May 15, 1953 concert, billed as 'the greatest concert ever', which came to be known as Jazz at Massey Hall, featuring Parker, Gillespie, Powell, Mingus and Roach. Also released on this label was the groundbreaking bass-and-drum free improvisation, Percussion Discussion.

In 1954, Roach and trumpeter Clifford Brown formed a quintet that also featured tenor saxophonist Harold Land, pianist Richie Powell (brother of Bud Powell), and bassist George Morrow, though Land left the following year and Sonny Rollins soon replaced him. The group was a prime example of the hard bop style also played by Art Blakey and Horace Silver. This group was to be short-lived; Brown and Powell were killed in a car accident on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in June 1956. The first album Roach recorded after their deaths was Max Roach + 4. After Brown and Powell's deaths, Roach continued leading a similarly configured group, with Kenny Dorham (and later the short-lived Booker Little) on trumpet, George Coleman on tenor and pianist Ray Bryant. Roach expanded the standard form of hard-bop using 3/4 waltz rhythms and modality in 1957 with his album Jazz in 3/4 time. During this period, Roach recorded a series of other albums for the EmArcy label featuring the brothers Stanley and Tommy Turrentine.

In 1955, he was the drummer for vocalist Dinah Washington at several live appearances and recordings. Appearing at the Newport Jazz Festival with her in 1958 which was filmed and the 1954 live studio audience recording of Dinah Jams, considered to be one of the best and most overlooked vocal jazz albums of its genre.

1960s-1970s

In 1960 he composed and recorded the album We Insist!, subtitled Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite, with vocals by his then-wife Abbey Lincoln and lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr., after being invited to contribute to commemorations of the hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. In 1962, he recorded the album Money Jungle, a collaboration with Mingus and Duke Ellington. This is generally regarded as one of the very finest trio albums ever made.

During the 1970s, Roach formed a musical organization—"M'Boom"—a percussion orchestra. Each member of this unit composed for it and performed on many percussion instruments. Personnel included Fred King, Joe Chambers, Warren Smith, Freddie Waits, Roy Brooks, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, Francisco Mora, and Eli Fountain.

1980s-1990s

In the early 1980s, Roach began presenting entire concerts solo, proving that this multi-percussion instrument could fulfill the demands of solo performance and be entirely satisfying to an audience. He created memorable compositions in these solo concerts; a solo record was released by Baystate, a Japanese label. One of these solo concerts is available on video, which also includes a filming of a recording date for "Chattahoochee Red", featuring his working quartet, Odean Pope, Cecil Bridgewater and Calvin Hill.

Roach embarked on a series of duet recordings. Departing from the style of presentation he was best known for, most of the music on these recordings is free improvisation, created with the avant-garde musicians Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, Archie Shepp, and Abdullah Ibrahim. Roach created duets with other performers: a recorded duet with the oration by Martin Luther King, "I Have a Dream"; a duet with video artist Kit Fitzgerald, who improvised video imagery while Roach spontaneously created the music; a duet with his lifelong friend and associate Gillespie; a duet concert recording with Mal Waldron.

Roach wrote music for theater, such as plays written by Sam Shepard, presented at La Mama E.T.C. in New York City.

Roach found new contexts for presentation, creating unique musical ensembles. One of these groups was "The Double Quartet". It featured his regular performing quartet, with personnel as above, except Tyrone Brown replaced Hill; this quartet joined "The Uptown String Quartet", led by his daughter Maxine Roach, featuring Diane Monroe, Lesa Terry and Eileen Folson.

Another ensemble was the "So What Brass Quintet", a group comprising five brass instrumentalists and Roach, no chordal instrument, no bass player. Much of the performance consisted of drums and horn duets. The ensemble consisted of two trumpets, trombone, French horn and tuba. Musicians included Cecil Bridgewater, Frank Gordon, Eddie Henderson, Rod McGaha, Steve Turre, Delfeayo Marsalis, Robert Stewart, Tony Underwood, Marshall Sealy, Mark Taylor and Dennis Jeter.

Roach presented his music with orchestras and gospel choruses. He performed a concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He wrote for and performed with the Walter White gospel choir and the John Motley Singers. Roach performed with dancers: the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the Dianne McIntyre Dance Company, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company.

Roach surprised his fans by performing in a hip hop concert, featuring the artist-rapper Fab Five Freddy and the New York Break Dancers. He expressed the insight that there was a strong kinship between the outpouring of expression of these young black artists and the art he had pursued all his life.

Not content to expand on the musical territory he had already become known for, Roach spent the decades of the 1980s and 1990s continually finding new forms of musical expression and presentation. Though he ventured into new territory during a lifetime of innovation, he kept his contact with his musical point of origin. He performed with the Beijing Trio, with pianist Jon Jang and erhu player Jeibing Chen. His last recording, Friendship, was with trumpeter Clark Terry, the two long-standing friends in duet and quartet. Roach's last performance was at the 50th anniversary celebration of the original Massey Hall concert, in Toronto, where he performed solo on the hi-hat.

In 1994, Roach also appeared on Rush drummer Neil Peart's Burning For Buddy performing "The Drum Also Waltzes", Part 1 and 2 on Volume 1 of the Volume 2 series during the 1994 All-Star recording sessions.

Death

Max Roach died in the early morning of August 16, 2007, in Manhattan. He was survived by five children: sons Daryl and Raoul, and daughters Maxine, Ayo and Dara. Over 1,900 people attended his funeral at Riverside Church in Manhattan, New York City, on August 24, 2007. Max Roach was interred at the Woodlawn Cemetery, The Bronx, New York City.

In a funeral tribute to Roach, then-Lieutenant Governor of New York David Paterson compared the musician's courage to that of Paul Robeson, Harriet Tubman and Malcolm X, saying that "No one ever wrote a bad thing about Max Roach's music or his aura until 1960, when he and Charlie Mingus protested the practices of the Newport Jazz Festival."

Personal life

Two children, son Daryl Keith Roach and daughter Maxine Roach, were born from Roach's first marriage with Mildred Roach in 1949. In 1958 he met singer Barbara Jai (Johnson) and fathered another son, Raoul Jordu. He continued to play as a freelance while studying composition at the Manhattan School of Music. He graduated in 1952. During the period 1961–1970, Roach was married to the singer Abbey Lincoln, who had performed on several of Roach's albums. In 1971, twin daughters, Ayodele Nieyela and Dara Rashida, were born to Roach and his third wife, Janus Adams Roach. He had four grandchildren: Kyle Maxwell Roach, Kadar Elijah Roach, Maxe Samiko Hinds, and Skye Sophia Sheffield. Long involved in jazz education, in 1972 he was recruited to the faculty of the University of Massachusetts Amherst by Chancellor Randolph Bromery. In the early 2000s, Roach became less active from the onset of hydrocephalus-related complications.

From the 1970s through the mid-1990s Roach taught at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Style

Roach used traditional grip in his early activity but switched exclusively to matched grip as his career progressed.

Roach's most significant innovations came in the 1940s, when he and jazz drummer Kenny Clarke devised a new concept of musical time. By playing the beat-by-beat pulse of standard 4/4 time on the "ride" cymbal instead of on the thudding bass drum, Roach and Clarke developed a flexible, flowing rhythmic pattern that allowed soloists to play freely. The new approach also left space for the drummer to insert dramatic accents on the snare drum, "crash" cymbal and other components of the trap set.

By matching his rhythmic attack with a tune's melody, Roach brought a newfound subtlety of expression to his instrument. He often shifted the dynamic emphasis from one part of his drum kit to another within a single phrase, creating a sense of tonal color and rhythmic surprise. The idea was to shatter musical conventions and take full advantage of the drummer's unique position. "In no other society", Roach once observed, "do they have one person play with all four limbs."

While that approach is common today, when Clarke and Roach introduced the new style in the 1940s it was a revolutionary musical advance. "When Max Roach's first records with Charlie Parker were released by Savoy in 1945", jazz historian Burt Korall wrote in the Oxford Companion to Jazz, "drummers experienced awe and puzzlement and even fear." One of those awed drummers, Stan Levey, summed up Roach's importance: "I came to realize that, because of him, drumming no longer was just time, it was music."

In 1966, with his album Drums Unlimited (which includes several tracks that are entirely drum solos) he demonstrated that drums can be a solo instrument able to play theme, variations, rhythmically cohesive phrases. He described his approach to music as "the creation of organized sound." The track "The drum also waltzes" was often quoted by John Bonham in his Moby Dick drum solo and revisited by other drummers like Neil Peart and Steve Smith. Bill Bruford performed a cover on the album Flags (1985).

Honors

Roach was given a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant in 1988, cited as a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in France (1989), twice awarded the French Grand Prix du Disque, elected to the International Percussive Art Society's Hall of Fame and the Downbeat Magazine Hall of Fame, awarded Harvard Jazz Master, celebrated by Aaron Davis Hall, given eight honorary doctorate degrees, including degrees awarded by Medgar Evers College, CUNY, the University of Bologna, Italy and Columbia University. While spending the later years of his life at the Mill Basin Sunrise assisted living home, in Brooklyn, Max was honored with a proclamation honoring his musical achievements by Brooklyn borough president Marty Markowitz.

In 1986 the London borough of Lambeth named a park in Brixton after him. Roach was able to officially open it when he visited the UK that year invited by the Greater London Council, when he performed at a concert in March at the Royal Albert Hall together with Ghanaian master drummer Ghanaba and others.

Roach was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame in 2009.

Discography

Compilations

Alone Together: The Best of the Mercury Years (Verve, 1954–60 [1995])

As co–leader

With Clifford Brown

1954: Best Coast Jazz (Emarcy)

1954: Clifford Brown All Stars (Emarcy, [released 1956])

1954: Jam Session (EmArcy, 1954) – with Maynard Ferguson and Clark Terry

1954 : Brown and Roach Incorporated (EmArcy)

1954 : Daahoud (Mainstream) – released 1973

1955 : Clifford Brown with Strings (EmArcy)

1954–55 : Clifford Brown and Max Roach (EmArcy)

1955 : Study in Brown (EmArcy)

1954 : More Study in Brown

1956 : Clifford Brown and Max Roach at Basin Street (EmArcy)

1979 : Live at the Bee Hive (Columbia)

With M'Boom

1973 : Re: Percussion (Strata-East)

1979 : M'Boom (Columbia)

1984 : Collage (Soul Note)

1992 : Live at S.O.B.'s New York (Blue Moon)

Wikipedia

7 notes

·

View notes