#Mary Church Terrell Main Library

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

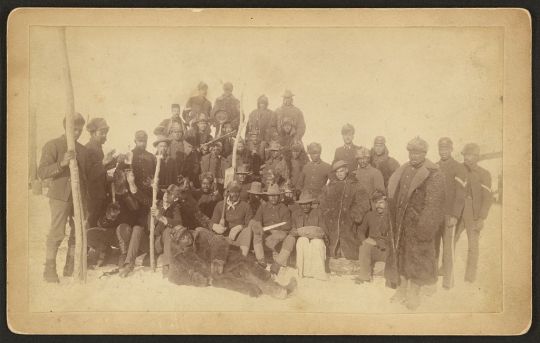

Have you ever seen an episode of Gunsmoke where African American soldiers were part of the regiment guarding the prairie? How about Bonanza? What about The Big Valley? All three were popular television series in which fiction and fact were often blended to add a semblance of reality to certain episodes. All three were set in the western frontier and at similar time periods in American history. Gunsmoke, in particular, issued several episodes depicting the U. S. Calvary scouting the Kansas frontier in hopes of squashing potential “Indian uprisings” and “protecting white settlers" who lived away from the main population clusters from "invasion by Indians." Bonanza, set in Nevada between 1861 and 1870, often had the cavalry in pursuit of "renegade Indians"

One episode of The Big Valley, set in California, stands out in that it mentions the fact that the Buffalo Soldier was a courageous military unit known for their loyalty and passion to serve. The episode featured African American actor, Yaphet Kotto, in the role of Damien. He gets the attention of Victoria, played by Barbara Stanwyck, when her son, Jerrod, played by Richard Long, recognizes Damien as no ordinary prisoner but a member of the Buffalo Soldiers.

Who were these Buffalo Soldiers and what role did they play in America’s history?

According to the federal government sources, the alias ‘Buffalo Soldier’ was the name used by the indigenous population to describe the African American soldiers of the 10th Cavalry, a regiment created to assist in the United States campaign to subdue the Indigenous peoples living on the western frontier.

The regiment, originally stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, suffered many set backs at the outset. In addition to a lack of clerical assistance and necessary number of recruits needed to build the regiment, the first officer appointed to lead the troops resigned. An outbreak of cholera also threatened the survival of the troops.

These soldiers also battled discrimination of the worst kind from within and outside of the military. Their bravery, integrity, and unequivocal commitment to the United States should never be overlooked. In addition to engaging in several battles, including helping to secure the victory on San Juan Hill, “the soldiers of the 10th Cavalry scouted thousands of miles of territory, built forts, opened more than 300 miles of new roads, installed over 200 miles of telegraph lines, located important water sources, protected stagecoach and mail routes, and escorted cattle drives and wagon trains.” (Santa Fe National Historic Trail)

As you celebrate Veterans Day this year, remember the Buffalo Soldiers and all those who serve and have served the nation.

Check out the following Federal sites and resources to find out more about the Buffalo Soldiers and their place in America’s history:

Black Soldier battled prejudice with honor

Buffalo Soldiers Study

Fort Leavenworth and the Establishment of the 10th Cavalry

History of the 10th Calvary

Image: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#government resources#depository library#Veterans Day#Buffalo Soldiers#African-Americans

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Celebrating the 45th Anniversary of the Seeley G. Mudd Learning Center

The Oberlin College Archives will be presenting an exhibit celebrating the 45th anniversary of the Seeley G. Mudd Learning Center, dedicated on May 25, 1974, during Oberlin’s Commencement/Reunion Weekend 2019. Named for the distinguished physician and philanthropist, the Mudd Center is home to the Mary Church Terrell Main Library, the Irvin E. Houck Center for Information Technology, the College Archives and Special Collections, Azariah’s Cafe, and many other departments and resources.

Make sure to come to the Robert S. Lemle ’75 and Roni Kohen-Lemle ’76 Academic Commons of Terrell Library during Commencement/Reunion Weekend to check out the exhibit and see more materials like these!

Pictured Above:

Dedication program for the Seeley G. Mudd Learning Center, May 25, 1974

Eileen Thornton, Oberlin College Librarian, 1956-71. Thornton was instrumental in addressing the space issues in the former Carnegie Library, and securing support for a new building, which took eight years of planning.

Construction of the Mudd Center, September 1973

The completed Mudd Center, ca. 1975

From Left to Right, Herbert F. Johnson, Librarian of Oberlin College, 1971-78, Eileen Thornton, Librarian of Oberlin College, 1956-71, and Julian Fowler, Librarian of Oberlin College, 1927-56, seated in what is now the Academic Commons of the Mudd Center, December 1974.

Please contact us if you have any questions about the Mudd Center’s history at Oberlin.

#oberlin#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Archives#oberlin college libraries#mudd center#seeley g mudd learning center#throwback thursday#mary church terrell main library

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nannie Helen Burroughs

Nannie Helen Burroughs (May 2, 1879 – May 20, 1961) was an African-American educator, orator, religious leader, civil rights activist, feminist and businesswoman in the United States. Her speech "How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping," at the 1900 National Baptist Convention in Virginia, instantly won her fame and recognition. In 1909, she founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, DC. Burroughs' objective was at the point of intersection between race and gender. She fought both for equal rights in races as well as furthered opportunities for women beyond the simple duties of domestic housework. She continued to work there until her death in 1961. In 1964, it was renamed the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor and began operating as a co-ed elementary school. Constructed in 1927–1928, its Trades Hall has a National Historic Landmark designation.

Early life and education

Nannie H. Burroughs born on May 2, 1879, in Orange, Virginia. She is considered to be the eldest of the daughters of John and Jennie Burroughs. Around the time she was five years old, Nannie's youngest sisters died in utero and her father, who was a farmer and Baptist preacher, died a few years later. John and Jennie Burroughs were both former slaves. Nannie's parents had skills and capacities that enabled them to start toward prosperity by the time the war ended and freed them. She had a grandfather known as Lija the carpenter, during the slave era, who was capable of buying his way out to freedom.

By 1883, Burroughs and her mother relocated to D.C. and stayed with Cordelia Mercer, Nannie Burroughs' aunt and older sister of Jennie Burroughs. In D.C., there were better opportunities for employment and education. Burroughs attended M Street High School. It was here she organized the Harriet Beecher Stowe Literary Society, and studied business and domestic science. There she met her role models Anna J. Cooper and Mary Church Terrell, who were active in the suffrage movement and civil rights.

Upon graduating from M Street High School with honors in 1896, Burroughs sought work as a domestic-science teacher in the District of Columbia Public Schools, but was unable to find a position. Though it is not documented that she was explicitly told, Burroughs was refused the position with the implication that her skin was too dark — they preferred lighter-complexioned black teachers. Her skin color and social status had thwarted her for the appointment she was chosen for. Burroughs said that "the die was cast [to] beat and ignore both until death." This zeal opened a door to the profession for low-income and social status black women. This is what led Burroughs to establish a training school for women and girls.

Career

From 1898 to 1909, Burroughs was employed in Louisville, Kentucky, as an editorial secretary and bookkeeper of the Foreign Mission Board of the National Baptist Convention. In her time in Louisville, the Women's Industrial Club had formed. Here they held domestic science and management courses. One of the founders of the Women's Convention was Nannie Burroughs, providing additional help to the National Baptist Convention and serving from 1900 to 1947: nearly half a century. She was president for 13 years in the Women's Convention. This convention had the largest form [attendance?] of African Americans ever seen, and help from this convention was highly important for black religious groups, thanks to the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) which formed in 1896, the largest of three and including more than 100 local women's clubs. Because of her contribution to the NACW, the National Association of Wage Earners was founded to draw the public's attention to the dilemma of African-American women. Burroughs was president, with other well-known club women such as vice president Mary McLeod Bethune and treasurer Maggie Lena Walker. These women placed more emphasis on public interest educational forums than trade-union activities. Burroughs' other memberships included Ladies' Union Band, Saint Lukes, Saturday Evening, and Daughters of the Round Table Clubs. Burroughs' also actively participated in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

By 1928 Burroughs was working in the system. She was appointed to committee chairwoman by the administration of Herbert Hoover, which was associated with Negro housing, for the White House Conference of 1931 Home Building and Ownership, straight from the stock market crash of 1929 just as the Great Depression began. Burroughs spoke at the Virginia Women's Missionary Union at Richmond with the address "How White and Colored Women Can Cooperate in Building a Christian Civilization." in 1933

Burroughs was also a published playwright. In the 1920s, she wrote The Slabtown District Convention and Where is My Wandering Boy Tonight?, both one-act plays for amateur church theatrical groups. The popularity of the comedic, satiric Slabtown necessitated multiple printings through the succeeding century, although sometimes the wording is updated as needed by successive productions.

Training school and racial uplift

Burroughs opened the National Training School in 1908. In the first few years of being open, the school provided evening classes for women who had no other means for education. The classes were taught by Burroughs herself. There were 31 students who regularly attended her classes, however, after time, and due to the high level of teaching, the school began attracting more students. The school was founded in a small farmhouse that eventually attracted women from all over the nation. During the first 40 years of the 20th century, young African-American women were being prepared by the National Training School to "uplift the race" and obtain a livelihood. The emphasis of the school was "the three B's: the Bible, the bath, and the broom". Burroughs created her own history course that was dedicated to informing women about society influencing Negroes in history. Since this was not a topic that was discussed in regular historical curriculum, Burroughs found it necessary to teach African American women to be proud of their race. With the incorporation of industrial education into training in morality, religion, and cleanliness, Nannie Helen Burroughs and her staff needed to resolve a conflict central to many African-American women. "Wage laborer" was their main role of the service occupations of the ghetto, as well as their biggest role model as guardians for "the race" of the community. The dominant culture of African Americans' immoral image had to be challenged by the National Training School, training African-American women from a young age to become efficient wage workers as well as community activists, reinforcing the ideal of respectability, as extremely important to "racial uplift." Racial pride, respectability, and work ethic were all key factors in training being offered by the National Training School and racial uplift ideology. These qualities were seen as extremely important for African-American women's success as fund-raisers, wage workers, and "race women". All these gathered from the school would bring African-American women into the labor of public sphere including politics, uplifting racial aid, and the domestic sphere expanded. By understanding the uplift ideology of its grassroots nature, Burroughs had used it to promote her school. Many disagreed with Burroughs teaching women skills that did not directly apply to domestic housework. None the less, students continued coming and the school carried on.

Death and legacy

On May 20, 1961, she was found dead in Washington D.C. of natural causes. She had died alone; she never married because she had dedicated her life to the National Trade and Professional School. She was buried at the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church where she was a member.

Three years after her death the institution was renamed the Nannie Burroughs School and has remained that way since. Even though more than 50 years has passed since her death, her history and legacy continue to motivate modern African-American women. The Manuscript Division in The Library of Congress holds 110,000 items in her papers.

1907, she received an honorary M.A. from Eckstein Norton University, a historically black college in Cane Spring, Bullitt County, Kentucky. (It merged with Simpson University in 1912.)

In 1964, the school that Burroughs had founded in 1909 as the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, DC, was renamed the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor. Its Trades Hall has been designated as a National Historic Landmark.

1975, Mayor Walter E. Washington declares May 10 Nannie Helen Burroughs Day.

Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue NE, a street in the Deanwood neighborhood of Washington, DC, is named for her.

In 1997 the National Women's History Project honored Burroughs during Women's History Month.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events in honor of the anniversary of President Ambar's inauguration and the naming of the Mary Church Terrell Main Library

1 note

·

View note

Link

1. Oberlin has four main libraries: the Main Library (commonly referred to as Mudd, but it is soon going to be named the Mary Church Terrell Library, which will reside in Mudd Center), the Conservatory Library, the Art Library, and the Science Library. Each offers resources that are available to students regardless of their major or whether they are in the Conservatory or the College.

9. There are great maps of the libraries online that make it much easier to find items if you know the call number. Here are links to Main Library 1st floor, 2nd floor, 3rd floor, and 4th floor. Art library! Conservatory 1st floor east wing, 1st floor west wing, 2nd floor. Science library!

13. Printing! Students get $40 of print money at the beginning of every semester. Before you print on a library computer, you’ll be asked for your ObieID and password, which pays for whatever you’re printing. Be careful of whether or not you check the “print double-sided” box, because I have made too many accidents from that darned box.

17. You can check out electronics, including laptops and laptop chargers, from all four of the campus libraries. iPads are also available to check out from the Main Library. The check-out periods and out of library policies vary between libraries.

0 notes

Text

American History!!

February 6, 2017 *Nannie Helen Burroughs, (May 2, 1879 – May 20, 1961) was an African-American educator, orator, religious leader, civil rights activist, feminist and businesswoman in the United States. Her speech "How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping," at the 1900 National Baptist Convention in Virginia, instantly won her fame and recognition.

In 1909, she founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, DC. She continued to work there until her death in 1961. In 1964, it was renamed the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor and began operating as a co-ed elementary school. Constructed in 1927-1928, its Trades Hall has a National Historic Landmark designation.

Early life and education Nannie H. Burroughs born on May 2, 1879, in Orange, Virginia. She is considered to be the eldest of the daughters of John and Jennie Burroughs. Around the time she was 5 years old, her youngest sister died in utero and her father, who was a farmer and Baptist preacher, died a few years later. Her mother and father belonged to a small fortune of ex-slaves which compelled them to start toward prosperity by the time the war ended and freed them.

She had a grandfather known as Lija the carpenter, during the slave era. He was capable of buying his way out to freedom.

By 1883, Burroughs and her mother relocated to D.C. and stayed with Cordelia Mercer, Nannie Burroughs' aunt and older sister of Jennie Burroughs. In D.C., there were better opportunities for employment and education. She attended M Street High School. It was here she organized the Harriet Beecher Stowe Literary Society, and studied business and domestic science. There she met her role models Anna J. Cooper and Mary Church Terrell, who were active in the suffrage movement and civil rights.

Burroughs expected to work as a teacher in the District of Columbia Public Schools. She was told she was "too dark" — they preferred lighter-complexioned black teachers. It wasn't just skin color that seemed to be the issue — her social pull had thwarted her for the appointment she was chosen for (if, in fact true, or not). Burroughs said it herself "the die was cast [to] beat and ignore both until death." This zeal opened a door to a whole new set of opportunities for low-income and social status Black women. This is what led Burroughs into a whole new path of opportunities such as establishing a training school for women and girls to fight injustice.

Career Burroughs holding Woman's National Baptist Convention banner.

From 1898 to 1909, Burroughs was employed in Louisville, Kentucky, as an editorial secretary and bookkeeper of the Foreign Mission Board of the National Baptist Convention. In her time in Louisville, the Women's Industrial Club had formed. Here they held domestic science and management courses. One of the founders of the Women's Convention was Nannie Burroughs, providing additional help to the National Baptist Convention and serving from 1900 to 1947: nearly half a century. She was president for 13 years in the Women's Convention. This convention had the largest form [attendance?] of African-Americans ever seen, and help from this convention was highly important for black religious groups thanks to the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) which formed in 1896, the largest of three and including more than 100 local women's clubs. Because of her contribution to the NACW, the National Association of Wage Earners was founded to draw the public's attention to the dilemma of Negro women. Nannie Burroughs was president, with other well-known club women such as vice president Mary McLeod Bethune and treasurer Maggie Lena Walker. These women placed more emphasis on public interest educational forums than trade-union activities. Burroughs' other memberships included Ladies' Union Band, Saint Lukes, Saturday Evening, and Daughters of the Round Table Clubs.

By 1928 Burroughs was working in the system. She was appointed to committee chairwoman by the administration of Herbert Hoover, which was associated with Negro housing, for the White House Conference of 1931 Home Building and Ownership, straight from the stock market crash of 1929 just as the Great Depression began. Burroughs spoke at the Virginia Women's Missionary Union at Richmond with the address "How White and Colored Women Can Cooperate in Building a Christian Civilization." in 1933

Training school and racial uplift During the first 40 years of the 20th century, young African-American women were being prepared by the National Training School to "uplift the race" and obtain a livelihood. With the incorporation of industrial education into training in morality, religion, and cleanliness, Nannie Helen Burroughs and her staff needed to resolve a conflict central to many African-American women: "wage laborer" was their main role of the service occupations of the ghetto, as well as their biggest role model as guardians for "the race" of the community. The dominant culture of African-Americans' immoral image had to be challenged by the National Training School, training African-American women from a young age to become efficient wage workers as well as community activists, reinforcing the ideal of respectability, as it is extremely important to "racial uplift." Racial pride, respectability, and work ethic were all key factors in training being offered by the National Training School and racial uplift ideology. These qualities were seen as extremely important for African-American women's success as fund-raisers, wage workers, and "race women." All these gathered from the school would bring African-American women into the labor of public sphere including politics, uplifting racial aid, and the domestic sphere expanded. By understanding the uplift ideology of its grassroots nature, Burroughs had used it to promote her school.

Death and legacy On May 20, 1961 she was found dead in Washington D.C. of natural causes. She had died alone; she never married because she had dedicated her life to the National Trade and Professional School. She was buried at the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church where she was a member.

Three years after her death the institution was renamed the Nannie Burroughs School and has remained that way since. Even though more than a century has passed since her death, her history and legacy continue to motivate modern African-American women. The Manuscript Division in The Library of Congress holds 110,000 items in her papers.

Nannie Burroughs, 1913. 1907, she received an honorary M.A. from Eckstein Norton University, a historically black college in Cane Spring, Bullitt County, Kentucky. (It merged with Simpson University in 1912.) In 1976, the school that Burroughs had founded in 1909 as the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, DC, was renamed the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor. Its Trades Hall has been designated as a National Historic Landmark. Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue NE, a street in the Deanwood neighborhood of Washington, DC, is named for her. In 1997 the National Women's History Project honored Burroughs during Women's History Month.

*Blanche Kelso Bruce (March 1, 1841 – March 17, 1898) was a U.S. politician who represented Mississippi as a Republican in the U.S. Senate from 1875 to 1881; of mixed race, he was the first elected black senator to serve a full term. Hiram R. Revels, also of Mississippi, was the first African American to serve in the U.S. Senate, but did not serve a full term.

Life and Politics Bruce's house at 909 M Street NW in Washington, D.C. was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1975

Bruce was born into slavery in 1841 in Prince Edward County, Virginia near Farmville to Polly Bruce, an enslaved African-American woman who served as a domestic slave. His father was her master, Pettis Perkinson, a white Virginia planter. Bruce was treated comparatively well by his father, who educated him together with a legitimate half-brother. When Blanche Bruce was young, he played with his half-brother. His father legally freed Blanche and arranged for an apprenticeship so he could learn a trade.

Summary of Mr. Bruce's accomplishments through 1890. Bruce taught school and attended Oberlin College in Ohio for two years. He next worked as a steamboat porter on the Mississippi River. In 1864, he moved to Hannibal, Missouri, where he established a school for black children.

In 1868, during Reconstruction, Bruce moved to Bolivar, Mississippi and bought a plantation. He became a wealthy landowner of several thousand acres in the Mississippi Delta. He was appointed to the positions of Tallahatchie County registrar of voters and tax assessor before winning an election for sheriff in Bolivar County. He later was elected to other county positions, including tax collector and supervisor of education, while he also edited a local newspaper. He became sergeant-at-arms for the Mississippi state senate in 1870.

In February 1874, Bruce was elected by the state legislature to the Senate as a Republican, becoming the second African American to serve in the upper house of Congress. On February 14, 1879, Bruce presided over the U.S.

Senate, becoming the first African American (and the only former slave) to do so. In 1880, James Z. George was elected to succeed Bruce.

At the 1880 Republican National Convention in Chicago, Bruce became the first African American to win any votes for national office at a major party's nominating convention, winning 8 votes for vice president. The presidential nominee that year was James A. Garfield, who won election.

May 28, 1880 Herald of Kansas article (page 2) promoting the Blaine - Bruce ticket.

In 1881, Bruce was appointed by President Garfield to be the Register of the Treasury, becoming the first African American to have his signature featured on U.S. paper currency.

Bruce was appointed as the District of Columbia recorder of deeds in 1890–93, which was expected to yield fees of up to $30,000 per year. He also served on the District of Columbia Board of Trustees of Public Schools from 1892-95. He was a participant in the March 5, 1897 meeting to celebrate the memory of Frederick Douglass which founded the American Negro Academy led by Alexander Crummell.He was appointed as Register of the Treasury a second time in 1897 by President William McKinley and served until his death in 1898.

Relationship with other African Americans On the Bruce plantation in Mississippi, black sharecroppers lived in "flimsy wooden shacks," working in the same oppressive conditions as on white-owned estates.

After his Senate term expired, Bruce remained in Washington, D.C., where he secured a succession of Republican patronage jobs and stumped for Republican candidates across the country. There, he also acquired a large townhouse and summer home, and presided over black high society.

One newspaper wrote that Bruce did not approve of the phrase "colored men." He often said, "I am a Negro and proud of it."

Marriage and Family On June 24, 1878, Bruce married Josephine Beal Willson (1853–February 15, 1923), a fair-skinned socialite of Cleveland, Ohio amid great publicity; the couple traveled to Europe for a four-month honeymoon.

Their only child, Roscoe Conkling Bruce was born in 1879. He was named for New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, Bruce's mentor in the Senate. In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Blanche Bruce on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

In the fall of 1899, Josephine, accepted the position of Lady Principal at Tuskegee. While visiting Josephine at Tuskegee, during the summer break of his senior year at Harvard, Roscoe won a fan in Booker T. Washington and secured a position at Tuskegee as head of the Academic Department.

Honors and Legacy In July 1898, the Board of Trustees of Public Schools of the District of Columbia ordered that a then new public school building on Marshall Street be named the Bruce School in his honor. Marshall Street later became Kenyon Street and the Bruce School became Caesar Chavez Prep Middle School in 2009. The name is still used as the Bruce School was combined with the James Monroe school to create Bruce-Monroe, located on Capitol Hill.

*Hallie Quinn Brown (March 10, 1849 – September 16, 1949) was an African-American educator, writer and activist.

Biography Brown was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, one of six children. Her parents, Frances Jane Scroggins and Thomas Arthur Brown, were freed slaves. She attended Wilberforce University in Ohio, gaining a Bachelor of Science degree.

Her brother, Jeremiah, later became a politician in Ohio. Brown graduated from Wilberforce in 1873 and then taught in schools in Mississippi and South Carolina.

She was dean of Allen University in Columbia, South Carolina from 1885 to 1887 and principal of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama during 1892–93 under Booker T. Washington.

She became a professor at Wilberforce in 1893, and was a frequent lecturer on African American issues and the temperance movement, speaking at the international Woman's Christian Temperance Union conference in London in 1895 and representing the United States at the International Congress of Women in London in 1899.

In 1893, Brown presented a paper at the World's Congress of Representative Women in Chicago. In addition to Brown, four more African American women presented at the conference: Anna Julia Cooper, Fannie Barrier Williams, Fanny Jackson Coppin, and Sarah Jane Woodson Early.

Hallie Brown, giving a speech at Poro College in 1920.

Brown was a founder of the Colored Woman's League of Washington, D.C., which in 1894 merged into the National Association of Colored Women. She was president of the Ohio State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs from 1905 until 1912, and of the National Association of Colored Women from 1920 until 1924. She spoke at the Republican National Convention in 1924 and later directed campaign work among African American women for President Calvin Coolidge. Brown was inducted as an honorary member of Delta Sigma Theta.

Published works Bits and Odds: A Choice Selection of Recitations (1880) First Lessons in Public Speaking (1920) Homespun Heroines and Other Women of Distinction, with introduction by Josephine Turpin Washington (1926)

Have a blessed day and week. May Yeshua the Messiah bless you, Love, Debbie

0 notes

Photo

Born on May 10, 1886 to Harry and Helen Rogers in Grand Junction, Michigan, Faith Helen Rogers, graduated from Oberlin College Conservatory of Music in 1907. She seemed to have been joined at the hip to her older cousin, Ruth Alta Rogers.

Like Faith, Ruth was born in Grand Junction, and both their parents moved to West Superior, Wisconsin sometime in the 1890s. Their parents must have been well to do, as both households employed maids from Sweden or Norway. And, just like Ruth, Faith studied piano at Oberlin and taught music after graduation. Neither of them ever married.

Faith was quite popular at Oberlin. She was elected most musical by her classmates at the senior outing. She gave many recitals during her years at Oberlin and was often sought after to give instrumental support to voice and other performers. She did the same after graduation, the most notable as an accompanist to Alice Sjoselius, a well-known soprano, who gave a three city tour of Minnesota during the summer of 1912. Her talents were noted. As a prelude to an expected performance at Cornell University in 1908, one newspaper called her “one of Oberlin’s most brilliant pianists.”

In 1918 at the peek of America’s involvement in World War I, Faith enthusiastically joined the war effort as a member of the Y. M. C. A. entertainment troupe. She set sail for Paris, France in October 1918 but never made it there. She caught influenza on the S. S. Espagne and died of pneumonia. She is buried in Bourdeaux, France.

To learn more about Obies’ involvement in World War I, visit our Military Service in World War I digital collection.

Photo credit: Oberlin College Archives

#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#Oberlin College Archives#digital collections#World War !

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Government websites are some of the best sources for obtaining high quality, public domain images. While some sites such as the Agricultural Research Service and the Library of Congress provide clear indicators, encouraging users to download images, other sites, such as the United States Senate, require users to submit a form to acquire high resolution copies of its images. Some sites, such as PHIL (Public Health Image Library), were specifically created to address the needs of scientists, researchers and educators in need of images representing the agency's focus. Other sites are undeveloped and users may have to devise creative search strategies to find out what's available on those sites.

Many sites have public domain and copyrighted images integrated into their image collection, so users should read the guidelines and disclaimers before downloading. The State Department, for instance, prohibits users from making copies of the Great Seal and warns that doing so is a punishable offense. So, before downloading any of these great images, read the guidelines, and by all means follow the agency's recommendation for providing the proper attribution for the use of its images.

Here is a selected list of agencies and what images users might expect to see and download from their sites:

Agricultural Research Service: images of fruits, foods, flowers, plants, animals, and anything having to do with agriculture and nutrition.

Centers for Disease Control - Public Health Image Library: images of bacteria, viruses, instruments, and anything having to do with medicine, biology, and diseases. If you are the wee bit squeamish, you might want to avoid searching this site.

Central Intelligence Agency: maps of every country and continent

Library of Congress: anything and everything including portraits of famous and ordinary individuals. Metadata often accompany each image and users can chose various sizes and formats to download.

NASA: our amazing universe; features an image of the day accompanied by an article written by a professional astronomer. Each NASA center has its own photo gallery. The Kennedy Center for instance, with its proximity to the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge features photos taken of the wildlife and the habitats of that location.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory: images of space and space travel; space instruments and vessels and our awesome galaxy among other things; images are often accompanied with descriptions. Users have the option of downloading tiffs and jpegs.

National Park Service: America and its amazing landscapes and bounty

United States Geological Survey: our amazing planet with all its natural wonders and threats.

United States Senate: people, places and things covering all periods of United States history including political cartoons and caricatures. To obtain high resolution images, users must make a request to the Office of Senate Curator.

Credit: Photo by Peggy Greb, USDA/ARS

#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#government information#public domain images#Agricultural Research Service#centers for disease control#CIA#Library of Congress#NASA#Jet Propulsion Laboratory#National Park Service#USGS#United States Senate

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

During World War II (1941-1945) the Federal government ran a series of aggressive and targeted campaigns to get Americans to support the war effort. One of the most distinctive and well orchestrated campaigns was organized by the Treasury Department in the promotion of its E, F, and G war bonds series. The Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, was resolute in wanting all Americans involved in the war effort and one of the his first decisions was to target the everyday working American by making the E bonds affordable. One of the programs he used to promote that endeavor was the Payroll Savings Plan. Another was the the Schools-At-War Program.

Promoted by the Education Section of the War Finance Division of the Treasury Department, the Schools-At-War Program encouraged students to save their nickels, dimes, and quarters with the ultimate goal of buying a U. S. Savings Bond. Schools across the nation instituted Stamp Day where students would purchase stamps to help finance jeeps and other military vehicles including airplanes, sponsor individual soldiers, and finance personal items such as shaving kits as well as uniforms and other necessary equipment used by the military.

The main goal of the war savings program was to help finance the war, keep inflation at bay, and build financial security for families in postwar America. The Treasury Department saw the Schools-at-War Program as “one of education, action, and morale-building.” Savings activities were integrated into lesson plans in subjects such as mathematics and English. One ingenious outreach was in the form of plays written to educate young and old alike about the value of the war savings outreach.

The Squander Bug’s Mother Goose, a play written for elementary and junior high school students by Aileen L. Fisher, demonstrated the necessity of saving for the war rather than spending money frivolously.

A Letter From Bob, a play geared towards junior and high school students encouraged supporting the soldiers who were fighting overseas.

Other plays, such as Figure it Out, a musical for all age groups alerted the public to the “threat of inflation and how Bond buyers can help check it.”

The School-At-War Program was a success. During 1942-1943 the Secretary of the Treasury reported that schools bought enough stamps “equivalent to the cost of 39,535 jeeps.” Another story reported that twenty-five schools on the South Side of Chicago, where the majority of students are “negroes,” raised $263,000 in war savings in one month.

To learn more about the Schools-At-War Program, head for your closest Federal Depository Library.

#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#government publications#Federal Depository Library#Treasury Department#World War II

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In January 1980 nine African American students from Oberlin College participated in a winter term project to recreate the journey from Kentucky to Oberlin taken by hundreds of slaves seeking freedom. According to David Hoard, seven students retraced the steps while one went ahead of the group, making arrangements for stops along the way; the other student served as a videographer for the group.

The memorable image below, features the students making their entry into Oberlin at the end of their 420 miles journey.

Linked, arms in arms, from left to right are David Hoard, Marzella Player, Herman Beavers, Richard Littlejohn, Gale Ellison Adrian Banks, and Lester Barclay. Almost hidden from view, directly behind Barclay, are George Barnwell and Larry Spinks.

You can find out more about this image from the Oberlin College Archives Popular Images collection.

Credits: North Star image modified from Nikolay Nikolov’s Double North Star, May 31, 2020.

#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#Oberlin College Archives#Popular Images collection

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Refusing to Be Silenced: the Association for the Advancement of Women and the 1880 Census

In 1878, Mary F. Eastman, Henrietta L. T. Woolcott, and Romelia L. Clapp, members of the Association for the Advancement of Women, sent a memorial to Congress requesting that women be employed as enumerators for the 1880 Census. They argued that the previous census, taken 8 years earlier, was deficient in many respects and that women were specially equipped to collect accurate statistics on women and children. They stated that "gross errors in enumerating the births, ages, diseases, and deaths of children are the inevitable result of the natural barriers in the way of men as collectors of social and vital statistics."

Francis J. Walker, the Superintendent of the Census was amenable to the idea. In February 1880 he issued a circular stating that there were “no reasons existing in law for regarding women as ineligible for appointment as enumerators. Each supervisor must be the judge for himself, whether such appointments in any number would be practically advantageous in his own district." Although Walker’s statement was not an enthusiastic endorsement of the idea, it cracked the door. When the call for enumerators went out in the several districts a few supervisors boldly solicited women for positions as census takers.

Today, on this second day of Women’s History Month, let’s celebrate the women who opened the federal government's eyes to diversifying the federal workforce by employing women as census takers, an occupation that from 1760 was strictly the domain of the male sex.

#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#government publications#women's history month#Association for the Advancement of Women#Senate Documents#1880 Census

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Farnsworths and the Todds: a glimpse of Christian Courtship in 1840's America

What sparked the interest between David Todd and Charlotte Farnsworth is hidden in time. We know that they shared much in common. In addition to being committed to the Christian way of life, they both attended Oberlin College in the 1840s, following in the footsteps of older siblings.

David was following his older brother and reliable confidant, John Todd, when he met Charlotte. Although Charlotte and John did not cross paths as students, David was obviously smitten with her, so much so that, John would become the bridge connecting David to Charlotte during her sickness and ultimate death.

Charlotte was following the footsteps of her older sister, Emeline who after graduation from Oberlin, married another Oberlin graduate, the Reverend Sela Goodrich Wright, the namesake of Oberlin’s Sela G. Wright digital collection.

Of the several letters in the collection, which incidentally, were mostly written by and to Emeline Farnsworth Wright, there is one from John Todd to Charlotte's mother, Rebecca Farnsworth, that describes the last few days, hours and minutes leading up to Charlotte's death. That John stood in for his brother David, who was miles away when Charlotte died, and also for Charlotte's mother and siblings at the funeral, speaks volumes about the relationship that existed between David and Charlotte. There is a sense that Charlotte was expected to become a Todd in the near future but destiny interrupted that course, for John states "I cannot but feel sad, for I had anticipated much pleasure from a better acquaintance with C. and I know that he whose affections were enlisted in her, will feel the shock most deeply."

You can find out more about the Farnsworth family by browsing the correspondences in the Sela G. Wright Collection.

To find out more about the relationship between David and Charlotte, visit the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections, at the University of Illinois Library.

Also visit the Todd family papers in the Kenneth Spencer Research Library Archival Collections at the University of Kansas

Also see Charlotte's obituary in the Oberlin Evangelist, August 18, 1847

#Oberlin College#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#Oberlin College Archives#digital collections#correspondences#Sela G. Wright digital collection#John Todd#David Todd#Charlotte Farnsworth

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

They say “a picture is worth a thousand words” however this black and white photograph showing the back of David Owen’s head as he bleeds from injuries sustained from an attack by ruffians who objected to his presence in their neck of the woods cannot begin to describe the terror leading up to the moments before the picture was taken.

David Owen came to Oberlin College as a freshman in 1963 from Pasadena, California. In 1964 he joined in the struggle for civil rights by volunteering to work during the summer to solicit and register African-Americans to vote in the upcoming presidential election. While walking with a group of two men, one a Rabbi, and two African-American women from a scheduled event in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, he and the two men were brutally attacked by “segregationist.” According to the New York Times story, “a pick-up truck stopped along the highway. In it were two whites, one about 60 years old, the other about 35. One of them said, ‘We’re going to get you.’ Mr. Owen was hit over the head with what was described as a piece of steel about a half-inch in diameter.” (NYT, July 11, 1964)

Thankfully, neither David Owen nor any of the people with him were killed that day and David eventually returned to Oberlin, graduating in 1967 with a degree in economics. His story was quite different than what happened to James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner who were all terrorized and killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan earlier that summer in of all places a city called Philadelphia which is said to sit on Beacon Hill in Mississippi. What a contradiction!

Today, Tuesday, November 3, 2020 is election day. VOTE. Vote because one summer, Freedom Summer, 1964, three young men were killed, many people were attacked violently and subjected to extreme terror because they dared to support the right to vote for all Americans. VOTE.

Photo credit: Oberlin and Activism Collection

#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#digital collections#activisim#civil rights#voting

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who’s Behind That Chat Box?

The core reference team in the Terrell Main Library staffs the library chat box found on the library homepage. You can reach us on Sunday afternoon, during the day Monday through Friday, and evenings Monday through Thursday.

So, who are we? What are our jobs? What do we look like? What do we want you to know?

Meet Megan, Eboni and Elizabeth.

Megan’s job title is Academic Engagement & Digital Initiatives Coordinator/Team Leader of Reference and Instruction. She would like all of you to know, “If you've got a research problem, chances are good that you are not alone. By asking questions, you can help us make things smoother for everyone.”

Eboni’s job title is Outreach and Programming Librarian. She would like share an African proverb: “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” She also wants to let you know, “I’m happy to join you on your research journey. I am passionate about helping you to be the best researcher you can be!”

Elizabeth’s job title is Assessment and User Experience Librarian. She would like you to know, “I enjoy hearing about Oberlin students' research, and I'm happy to help out. If you have questions, always feel free to ask me!"

Meet Runxiao, Alonso and Julie

Runxiao’s job title is East Asian Studies Librarian. She would like you to know, ”We are here for you!”

Alonso’s job title is Information Literacy and Student Success Librarian. He would like you to know, “Don't hesitate to reach out for help to find the information you need."

Julie’s job title is Public Services Assistant. She would like you to know, “The very best part of my job is helping you succeed at Oberlin. No question is too great or to small to be asked.”

Now you can see the faces and learn a bit about each of the staff members behind the chat box found on the Main Library webpage and popping up in a few other places where you might be searching for information for your research project or class assignment. We look forward to chatting with you.

#oberlin college libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#library help#reference department#library question#OCL staff

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It Started in Memphis

Early signals of what would become the ongoing treatment of police brutality against African Americans started in Memphis on the horizon of freedom when newly freed slaves were viciously attacked during the first three days of May 1866 by a police-led mob.

The results of a congressional investigation did little to correct the injustices committed against these victims as the government was indifferent towards pursuing and punishing the perpetrators. Numerous witnesses testified before the Select Committee on the Memphis Riots, often providing the names of those who had committed murders, rapes, mutilations, and destruction of property including homes, schools, and churches, but no legal action was ever taken to signal a no tolerance policy against such egregious acts towards the African American population.

It is no coincidence that a little more than a hundred years later, Memphis would be the place where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., reverend, Nobel laureate, peacemaker, lover of mankind, husband, father, and the voice of love and human dignity was assassinated.

In commemoration of Black History Month, this post pays tribute to the men, women, boys, girls and infants on whom the wrath of racism was unleashed in the early days of May 1866. Here is a list of some of the victims and what they suffered:

Harriet Armour, raped and sodomized by two, one a city official

Rebecca Ann Bloom, raped

Robert Carlton, robbed and killed

Robert Reed Church, father of Mary Church Terrell, robbed and shot at fifteen times by policemen

Rachel Hatcher, killed

Lucy Smith, almost 17 years old, raped and brutally beaten to the point of death after being ordered to prepare a suitable supper for the perpetrators

Lucy Tibbs, raped

Francis Thompson, raped by four, two were policemen

The testimony of Emiline Wilson provides a chilling summary of the depths of the atrocities committed during the three days of terror.

On the night of the 3d of May, 1866, I was a short distance from the house occupied by John Green, and his wife, Ida Green, and family. I saw their house set on fire by a crowd of policemen and citizens. I saw Ida Green attempting to leave the house, but they drove her back into it; she begged and prayed them to let her out of the burning house, but they would not let her. She then attempted to come out anyhow, and they shot her. She fell partly in the house; they then kicked her and rolled her over like a log into the fire, where she was burned up. Her baby was in bed, and was burned up at the same time. Her husband, John Green, has never been seen since that evening, and I heard Mary Black and others say he was killed. (H. Rpt.39-101; Serial Set 1274, pg.353)

#Oberlin College#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#government publications#Black History Month#Racism--United States#Racism in the US#1866 Memphis Riots#gov docs#government documents

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Bit of History

Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Oberlin and the surrounding vicinity several times between 1957 and 1967. From his first speaking engagement on Oberlin's campus in 1957, students were enamored and supportive of King’s message of non-violence. King's speeches were compelling and created a desire for brotherhood and humanity within the hearts and minds of the listeners.

On one occasion in 1963 as students, faculty, staff and community waited in expectation to hear Martin Luther King speak on the "Future of Integration." The audience stood and applauded for four minutes as he made his way to the podium. The majority had waited since 10:30 am to enter Finney Chapel for the noon address by King. There was an electrifying anticipation in the air that Thursday, November 14, 1963 afternoon. It was expected. Earlier that August, the nation had been mesmerized by Dr. King as he delivered the iconic “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. And now, as Dr. King stood at the podium in Finney Chapel on Oberlin's campus, the audience could not withhold its admiration. However, as Dr. King began to speak it became clear that something was wrong. By Friday, the students’ newspaper, The Oberlin Review would report that Dr. King had only given a brief greeting to the audience before he was escorted off the stage by Oberlin College president, Robert K. Carr. A few days later, on November 18, President Carr received a letter from Dr. King explaining what had happened. The letter was published in The Oberlin Review on November 22, the same day President Kennedy was assassinated.

In the letter, Dr. King explained that "Words are inadequate for me to express my deep appreciation to you, your faculty members and students of Oberlin for the warm reception you gave me the other day, in spite of the fact that I was unable to give my scheduled lecture." He went on to say that "never before have I had such an experience. As I drove from Cleveland to Oberlin I felt myself getting progressively weaker and when I arrived on the campus, I knew that my energy was so far gone and my temperature had run so high I could not possibly stand before any audience without eventually collapsing...I am happy to say that I am a little better now. The flu bug doesn't pass easily, so the doctor insisted that I remain in bed five or six days."

To find out more about Dr. King's visits to Oberlin, search for the The Oberlin Review in our Student Newspapers at the Five Colleges of Ohio collection. For transcripts of Dr. King’s speeches and other writings, see the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project, a “cooperative venture of Stanford University, the King Center, and the King Estate.”

#oberlin college#Oberlin College Libraries#Mary Church Terrell Main Library#digital collections#The Oberlin Review#Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

4 notes

·

View notes