#Marthe Keller

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the way ive been fangirling over john cazale and meryl streep this past weekend they’re so cute

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

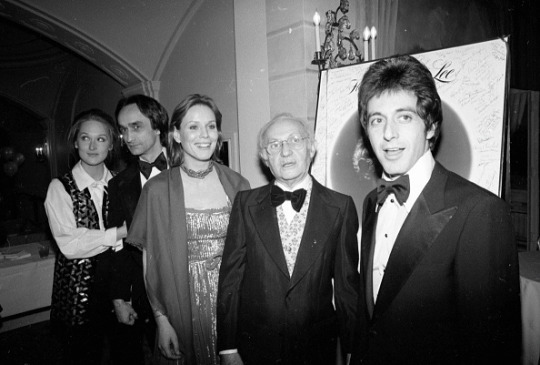

Marthe Keller, Al Pacino, and director Sydney Pollack during production of BOBBY DEERFIELD (1977)

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

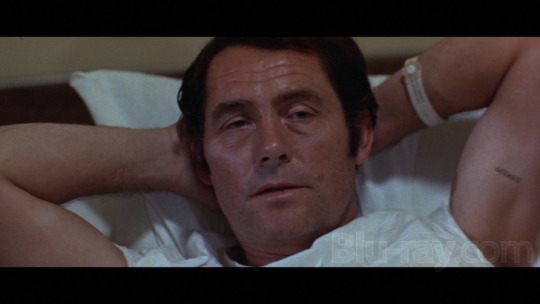

Laurence Olivier on set of Marathon Man (1976)

#marathon man#1976#john schlesinger#william goldman#dustin hoffman#laurence olivier#roy schneider#william devane#marthe keller

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

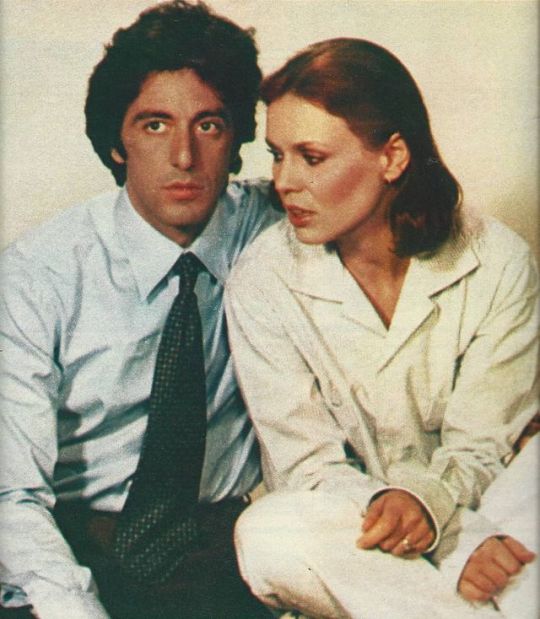

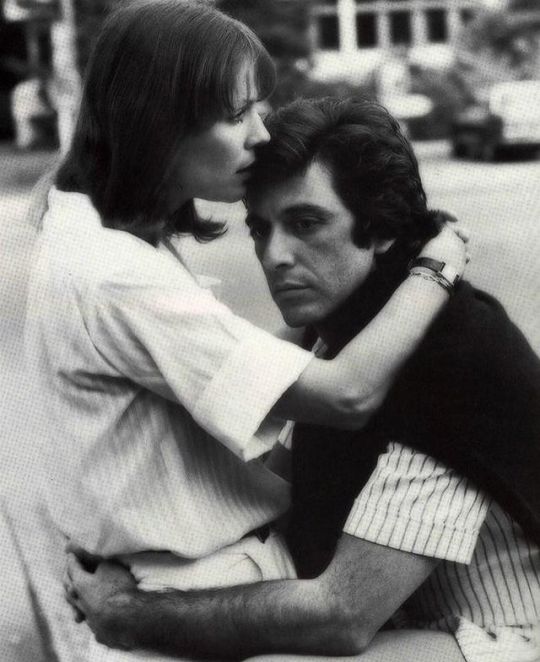

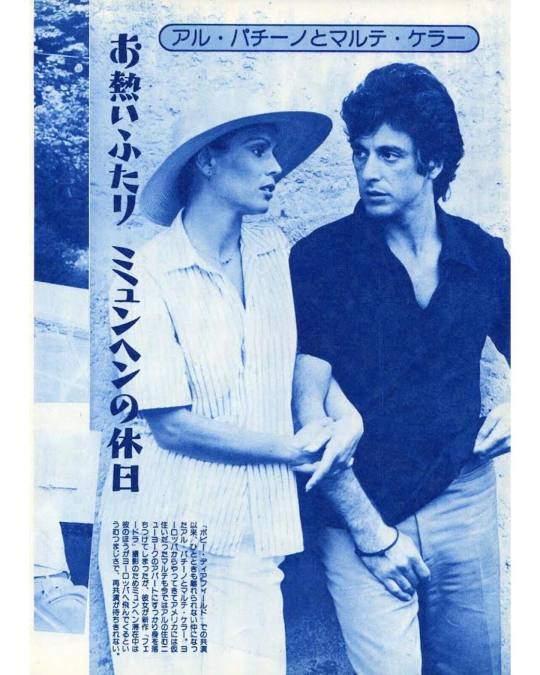

Al Pacino and Marthe Keller in Bobby Deerfield (1977)

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Shaw, Bruce Dern, Marthe Keller, Black Sunday, John Frankenheimer, 1977

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bobby Deerfield (1977) Al Pacino

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

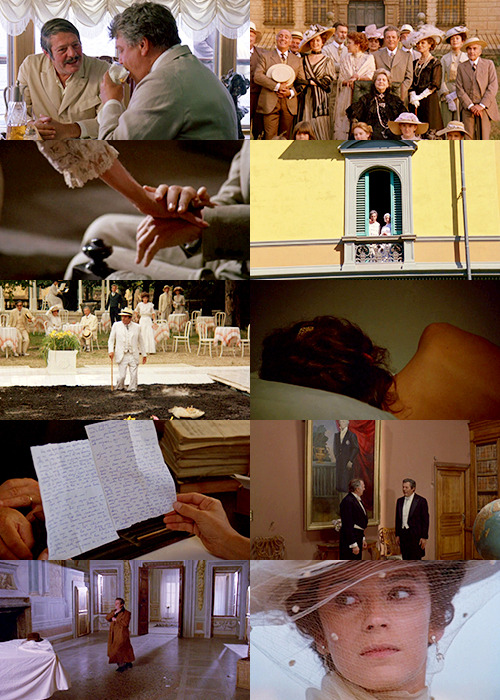

Fedora (1978) dir. Billy Wilder

#billy wilder#fedora#1978#actress#hollywood#moviegifs#william holden#marthe keller#70s hollywood#drama#filmgifs#70s aesthetic

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark Eyes (1987). An Italian tells his story of love to a Russian. In a series of flashbacks, Romano Patroni leaves his wife to visit a spa where he falls in love with a Russian woman. He returns to Italy resolved to leave his wife and marry his love.

Beautifully shot, and navigates the tonal shifts between humorous absurdism and tragic lost love incredibly well. Still, it never quite pulled me in, and the pacing felt off to me, although I'm not sure if I can entirely pinpoint why. A sumptuous period piece, but one that leaves something to be desired. 7/10.

#dark eyes#1987#Oscars 60#Nom: Actor#Oci ciornie#Nikita Mikhalkov#Aleksandr Adabashyan#Suso Cecchi D'Amico#anton chekhov#marcello mastroianni#Marthe Keller#Elena Safonova#romance#russia#italy#italian#russian#period#7/10

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

. It's a whole different business now. The kids with beards have taken over. They don't need scripts, just give 'em a hand-held camera with a zoom lens.

Fedora, Billy Wilder (1978)

#Billy Wilder#I.A.L. Diamond#William Holden#Marthe Keller#Hildegard Knef#José Ferrer#Frances Sternhagen#Mario Adorf#Stephen Collins#Henry Fonda#Michael York#Hans Jaray#Gottfried John#Gerry Fisher#Miklós Rózsa#Stefan Arnsten#Fredric Steinkamp#1978

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bobby Deerfield / full movie / 1977

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fedora (1978) Billy Wilder

January 1st 2024

#fedora#1978#billy wilder#william holden#marthe keller#hildegard knef#josé ferrer#frances sternhagen#mario adorf#hans jaray#Hans Járay#gottfried john#michael york#henry fonda#stephen collins#arlene francis

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mars Express (2023, France)

When it came out in 1988, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira was one of the first Japanese anime films to have a seismic impact beyond its home nation. For many soon-to-be anime fans, it was their first experience with Japanese animation. Akira, along with Ghost in the Shell (1995, Japan), scared off feature film animators from even considering cyberpunk science fiction for decades. Was it a self-consciousness of attempting to make a sort of animated film that the Japanese had seemingly cornered? Or was it a lack of funding and knowhow? In any case (and I will surmise it might be all of those aforementioned reasons), stepping into that extremely limited animated tradition comes Jérémie Périn’s stellar Mars Express.

The film, surprisingly to me, comes from an original screenplay he co-wrote with Laurent Sarfati, and not from, as I thought while watching the film, any graphic novel, comic series, or any preexisting material. Périn and Sarfati are both best known for the 2016 adult animation television series LastMan (an adaptation of the French comic series of the same name) and music videos for electronic dance music (EDM) artists. For them, Mars Express represents a breathtaking leap in narrative ambition, pulling influences from its animated cyberpunk predecessors and classic film noir, as its story unfolds hurriedly in less than a half-hour. And in its mixture of hand-drawn and computerized animation, the seamless effects make the film one of the most fascinating animated works for a mature audience in some time.

By 2200, androids of different forms are an irreplaceable part of human society, which straddles between an impoverished Earth, a metropolitan Mars, and various other colonies. We first meet our two protagonists, private detectives Aline Ruby (Léa Drucker) and android partner Carlos Rivera (Mathieu Amalric), on Earth. Carlos is a “backup”, as he possesses the consciousness of Aline’s deceased partner of the same name. The duo (the film confusingly distinguishes the boundaries between private investigators and police) apprehend a robot hacker, Roberta Williams, who is wanted on a number of charges. But when they are going through Martian security just after landing, the warrant for the hacker disappears – forcing Alina and Carlos to release Roberta.

Soon after, on Mars, Aline and Ruby must find a cybernetics student named Jun Chow. Jun has illegally “jailbroken” androids (freeing androids from human control, a civil rights issue of 2200s human society). Instances of jailbroken androids can lead to the deaths of innocents and wanton destruction, and the very fear of jailbroken androids leads to widespread prejudice and preemptive violence. Before Aline and Carlos realize it, Jun Chow's disappearance and the case behind Roberta Williams' seemingly dropped charges have a connection – one that threatens the coexistence of human and android existence, their separate and shared societies.

Mars Express breaks no ground narratively, and many of its larger themes of android self-determination and human-automaton relations will not be new for science fiction fans. What separates Mars Express from its peers across artistic mediums (television, comics/graphic novels, literature, video games) is its fully realized world. Périn and Sarfati, without any source material to guide them, have constructed a futuristic society that always feels plausible, consistent, and alive. Residential interiors seldom look like a real estate listing photograph, laboratories have wires and machinery strewn about, and crime scenes involving destroyed androids are mechanically gruesome (almost all androids have some sort of purple hydraulic fluid that enables movement), with bolts, screws, and scrap metal mangled and twisted. Human capitalism extends its hand across society and, presumably, politics. Rather than explain the technology that surrounds our characters and comprises this futuristic society, Périn and Sarfati prefer instead to keep Aline and Carlos’ investigations moving. Explanations of how all of this technology works is kept to a bare minimum, keeping the film’s pacing brisk and allowing for the film’s most violent moments to retain an elevated sense of peril.

By this point in human history, technology is approaching a level where robots are nearing indistinguishability from humans. However, the androids in Mars Express range from the brand-new to noticeably outdated. They have a variety of appearances – from the most humanlike (Carlos, the nightclub androids), to something out of Boston Dynamics, to boxy clunkers – and functions. From backups like Carlos to industrial workers to sexual companions, the robots in the Mars Express universe form a fundamental aspect of life in the far future – separate, but not fully free from human demands and impulses.

Embodying this tenuous balance is Carlos. Despite his death, Carlos’ consciousness, now housed inside a machine, carries on while his previous life moves beyond him. Though Carlos remains in his old job as a private investigator, he cannot continue seeing his ex-wife and daughter. The details of their estrangement are murky – did it occur before or after Carlos’ death? – and his wife’s new boyfriend is openly hostile to him. The latter’s hostility is such that Carlos’ relationship to his daughter crumbles. Indirectly, this troubled family life leads Carlos to stray from his humanity and better comprehend the desires of his fellow robots.

By film’s end, perhaps reluctantly, he accepts that humans – at an individual and collective level – might never see him as a full being. Often in modern science fiction, a narrative will present sentient robots and humans coming to a partial or full understanding about the former’s sense of personhood. While this plays out between Aline and Carlos (Aline treats “backup” Carlos essentially the same as her late partner), we see little desire to move beyond using these robots for human self-interest. This lends Mars Express its tragic dimensions – one felt by both humanity and robots (and with very light sprinkles of satire) – and places Carlos as the primary conduit of that tragedy.

Aline, as written, is not as complex as Carlos, but her craftiness and street sense makes her a worthy addition into the line of private detectives in film noir and films derived from noir. Her inner demons are difficult to parse. Yet, as a recovering alcoholic who has a subdermal sobriety chip that is easy to override), she too represents a future imperfect. She has a total dearth of companionship outside her line of work, possibly afraid of commitment, and carries about her a cynicism that rubs her coworkers and others she encounters on the job the wrong way. This is no Star Trek-like utopia as Gene Roddenberry might have envisioned it while he was alive (to the consternation of his fellow producers who saw even the cosmopolitan United Federation of Planets as a future imperfect). Nor is Mars Express a fully dystopian narrative. Surrounded by endless amounts of fellow humans, computers and robots providing luxury that modern viewers can only dream of, and not wanting for anything, Aline remains jaded about her very existence. She would find emotional company in the private detectives that Humphrey Bogart, Glenn Ford, and Dick Powell played on-screen.

In general, any humans of human-appearing characters in Mars Express are 2D while any androids or backgrounds bustling with activity (the car crash scene) are CGI. CGI animation allows to more efficiently render the diversity of robots across the film – very few of them look alike. The 2D/CGI differences are perceptible, but the effects, miraculously, do not clash (as they might have had this film been released ten or twenty years earlier). The heavily CGI backgrounds of the Martian capital, Noctis, fuse well with the nervy electronic score from Fred Avil and Philippe Monthaye. And in moments where the filmmakers juxtapose 2D and 3D animation, the slight variances between the two can be psychologically unsettling and increase the tension in the film’s many violent moments – most notably the opening scene and the climax. Full credit to the animators for achieving such an outstanding visual (and aural) continuity among the two styles.

Jérémie Périn and his fellow crewmembers note that they made those decisions of 2D and CGI animation in respect to the film’s tight budget. European feature animation lacks the commercial foundations and stability seen among the major American and Japanese studios, and requires various public and private funding sources from across the European Union. In French animation (and this applies to live-action French cinema, too), regional subsidies provide a lifeline. Splitting work across five animation studios allowed the Mars Express production to acquire more subsidies, raising the budget (still modest in comparison to those major American and Japanese studios) to coincide with the larger staff necessary to animate the film.

Despite its breakneck speed to cram in all of its narrative and thematic ideas, Mars Express still finds time for reflection and consideration. It may not necessarily slow down to allow the viewer to collect themselves, but Aline and Carlos’ professional relationship and habits are enough for one to feel the weight of the film’s most pressing questions. Can even the most enlightened humans in a futuristic, interplanetary society ever see sentients robots as beings independent from human selfishness and desire? How does rampant capitalism and indulgence play into such a society? In science fiction and, more specifically, cyberpunk sci-fi, these topics are well-worn. Other works in this genre and subgenre provide answers with eerie prescience and compelling optimism. The manner in which Jérémie Périn and Laurent Sarfati approach and depict their society, however, distinguishes itself through its excellent characterization and worldbuilding. Mars Express is a worthy addition to the exploding science fiction milieu, in no small part due to lack of animated works daring to venture there.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#Mars Express#Jérémie Périn#Laurent Sarfati#Léa Drucker#Mathieu Amalric#Daniel Njo Lobé#Marie Bouvet#Sébastien Chassagne#Marthe Keller#Geneviève Doang#Thomas Roditi#Usul#Fred Avril#Philippe Monthaye#GKIDS#My Movie Odyssey

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blu-ray review: “Black Sunday” (1977)

View On WordPress

#Bekim Fehmiu#Black Sunday#Black Sunday bluray#Black Sunday bluray review#bluray#bluray review#Bruce Dern#film#horror#John Frankenheimer#Marthe Keller#movie review#movie reviews#movies#Robert Shaw

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Life (PG): Hopkins, Bonham-Carter and Flynn Glitter in a Moving Biopic.

#onemannsmovies #filmreview of "One Life". #OneLifeMovie. Moving and educational biopic about a real-life hero with a brilliant Hopkins. 4/5.

A One Mann’s Movies review of “One Life” (2023). “One Life” has been doing the film festival circuit, but I missed it at the London Film Festival. But although it’s not officially released until January 1st, I saw it at a Cineworld Unlimited preview screening this week. It’s excellent, and I’ll be paying a second visit in the New Year with the illustrious Mrs Movie Man. Bob the Movie Man…

View On WordPress

#OneLifeMovie#Alex Sharp#Anthony Hopkins#bob-the-movie-man#bobthemovieman#Cinema#Film#film review#Helena Bonham-Carter#James Hawes#Johnny Flynn#Jonathan Pryce#Lena Olin#Lucinda Coxon#Marthe Keller#Movie#Movie Review#Nick Drake#One Life#One Man&039;s Movies#One Mann&039;s Movies#onemannsmovies#onemansmovies#Review#Romola Garai#Samantha Spiro#Tom Glenister#Ziggy Heath

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bobby Deerfield (1977) Al Pacino

13 notes

·

View notes