#Mahan Moalemi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

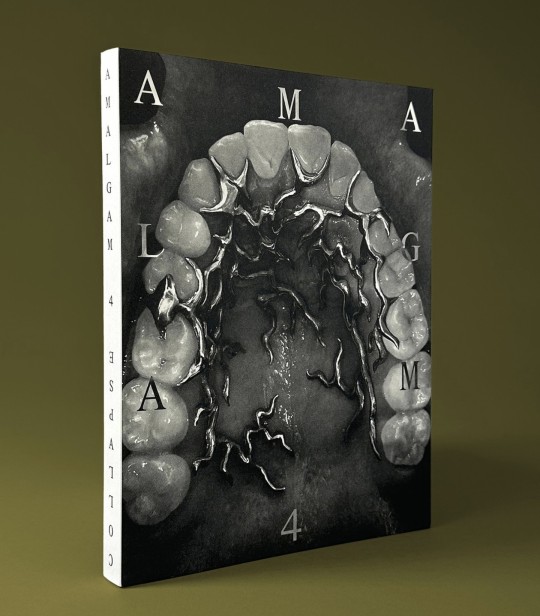

Amalgam 4 — Collapse

Amalgam #4 points toward the inextricably intertwined relationships between typography, language, and power. In doing so, it assembles a series of essays, anecdotal notes, conversations, and artworks that engage with, hint at, or revolve around the theme of collapse.

From collapse of language syntax, to collapse of semantics, barriers between languages, and language itself, this collection reverberates the material and immaterial conditions, formations, reproduction, and dissemination of power through language and typography. A series of revolutionary headdresses; the auditory and polemic bonds between the letters X, ח, and خ; the interiorities of illegibility; the downfall of the ancient Silk Road patterns; the West Asian Goddesses; an asemic grief; a deliberately missing language; a hearty stutter; and an Aleph that wore a hat to school.

Contributors in this issue include Adrien Flores, JJJJJerome Ellis, Klara du Plessis, Sophie Seita, Luis Camnitzer, Slavs and Tatars, Mimi Ọnụọha, Minh Nguyen, Maia Ruth Lee, Mashinka Firunts Hakopian, Helina Metaferia, Paul Soulellis, Carlos Motta, Lucy I. Zimmerman, Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Paul Benzon, Morehshin Allahyari, Anahita Razmi, J. Dakota Brown, Shabahang Tayyari, Mahan Moalemi, Dennis Grauel, Sasha Wilmoth, Thy Hà, and Alec Mapes-Frances

Designed and edited by Pouya Ahmadi

Published by Amalgam, 2023

Softcover, 200 pages, b&w, 6.5 × 9 inches

Available from Draw Down (online): https://draw-down.com/products/amalgam-4-collapse and from Pouya at this weekend's Boston Art Book Fair!

#Amalgam#Pouya Ahamdi#design journals#typography journals#art and design journal#typography and language#typography and power#Draw Down Books

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

My video Quartered (2014) is on Video Club April 11 - May 22 !

Along with the brilliant Mamali Shafahi and Seecum Cheung

Curated by Tabitha Steinberg and Mehraneh Atashi with a beautiful text by Mahan Moalemi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A conversation about Kunstverein München’s group show ‘Not Working – Artistic production and matters of class’ (2020-09-12 – 2020-11-01)

Conversants: The Bensplainer, Magda Wisniowska, and Victor Sternweiler [talking on Skype, in the evening of Nov 11, 2020.]

Victor: We should start our conversation about Kunstverein München’s show ‘Not Working – Artistic production and matters of class,’ [online through 2020-11-22] curated by Maurin Dietrich and Gloria Hasnay, while making clear that we were not able to attend the parallel program, consisting of tours, lectures, performances, and video screenings, which were partially screened online, and an extensive reader was published too. This will simply be a conversation about the actual show. One could claim that such a review can’t do justice to the whole project, but I claim that nobody was able to attend everything, except for the makers, so one can only have a fragmented take on it, and therefore it is legitimate to, mainly or solely, talk about the work installed in the space.

Exhibition consisted work by Angharad Williams, Annette Wehrmann, Gili Tal, Guillaume Maraud, Josef Kramhöller, Laura Ziegler and Stephan Janitzky, Lise Soskolne, Matt Hilvers, Stephen Willats.

A film screening series selected by Nadja Abt, showing work by Adrian Paci, Agnès Varda, Ayo Akingbade, Barbara Kopple, Berwick St Collective, Laura Poitras and Linda Goode Bryant, Max Göran.

A single event screening with films selected by Simon Lässig.

Accompanying program consisting of a book presentation (Düşler Ülkesi) by Cana Bilir-Meier (in conversation with Gürsoy Doğtaş), lectures by NewFutures, Ramaya Tegegne, Tirdad Zolghadr and a publication presentation (Phasenweise nicht produktiv) from a collaboration by Carolin Meunier and Maximiliane Baumgartner.

The reader containing contributions by Annette Wehrmann, Dung Tien Thi Phuong, Josef Kramhöller, Laura Ziegler and Stephan Janitzky, Leander Scholz, Lise Soskolne, Mahan Moalemi, Marina Vishmidt and Melanie Gilligan, Steven Warwick.

Exhibition documentation: https://artviewer.org/not-working-artistic-production-and-matters-of-class/

Magda: To help, I was rereading today the booklet accompanying the exhibition, although I don’t see how the text is really going to address what we see in the actual Kunstverein space. For example, I quote, “The works on view are characterized by a consciousness of how background, socialization, education, and artistic practice are inevitably entangled. They hence allow for a consideration of these categories in relation to the actual lived realities of their producers.” Does it mean that the artists somehow reflect their own social background? Autobiographically on their own lived reality? Well, by large, they don’t. We don’t know what social background these artists are coming from.

Victor: How would you know anyhow?

Magda: Instead, the coherency of the exhibition relies on going through all the positions which were outlined in the booklet’s introduction. So, Stephen Willats investigates the historical aspect of class, Annette Wehrmann performs the interrogation of the economic model, Josef Kramhöller’s is a more personal approach to consumerism, Gili Tal tackles gentrification and cosmopolitanism, and Angharad Williams addresses the performative and fashion , and so on. And at least two of the artists are no longer alive.

Victor: In the time of Covid, where you try to make ends meet, how can you say no? What I’m trying to say is that the precariousness of their class is testified also by artists not being able to nowadays refuse to participate in an exhibition in which they potentially don’t think they fit in. They do it, plain and simple.

The Bensplainer: I don’t think it is due to Covid. It’s a general trend. If you're invited by the artistic director of the Venice Biennale, whatever their exhibition idea is, you participate, as an artist. It’s not anymore the time when an Alighiero Boetti could angrily refuse an invitation by Harald Szeemann.

Magda: Is that really the central problem of this exhibition? There are a lot of problematic issues, and I am now again looking at the text, especially at the end, where it states that “today the question of class is not addressed anymore.” That is completely untrue. Much of postmodernism consisted precisely of the critical inquiry into questions of class. I don’t know about you, Bensplainer, but in my time in London we had to read a lot of Bourdieu, especially his idea concerning cultural capital.

The Bensplainer: Jameson was my lighthouse at that time!

Magda: It was a big thing! You can’t say really the topic had been ignored since then.

The Bensplainer: Especially after the last Documenta in 2017.

Magda: I acknowledge that the question of class is no longer about a white male perspective, defined by simple economics. But really? What does this exhibition add to this conversation?

The Bensplainer: I think that the main problem here is when you set up a thematic exhibition. If you, as a curator, have some aprioristic ideas about the specific interpretations on cultural work, then you tend to apply them to your own exhibition making. Although, you tend to lose contact with the works themselves. You tend to look more at the anecdotal parts of the work and at its processes. Let’s be honest, there are no great works in the exhibition, the ones being able to question your own vision of forms and of the world in which these forms happen.

Magda: I think the older works displayed here, as Stephen Willats’ ones, from the 1980s, present some problems: they are, in fact, historical, and at that time had a certain currency, whereas they seem today …

The Bensplainer: … nostalgic.

Magda: And dry as well: this kind of class idea, of people living in a housing block – like he documented and interviewed – it doesn’t seem relevant anymore. The other thing is that it seems so British, so entwined in that specific culture. We know this Monty Python sketch, right? This kind of satire, for example, wouldn’t fit German society at that time, I think.

youtube

Magda: The other thing I was thinking of, while walking through the exhibition, was Pulp’s ‘Common People.’ (1995) Did anyone think of that? The song is about a girl from the upper classes, who wants to behave as being from the lower. But she never achieves that, because she always has her rich daddy in the background. I think that a potential problem this exhibition faces is of glamorizing this kind of a working-class cliché.

youtube

Victor: That song is especially ironic, as it was brought to my attention by a friend that Danae Stratou, the artist, industrialist heir and wife of Yannis Varoufakis, is the subject of that song.

Magda: Yes, that’s why I mention it.

Victor: I had a chat with The Bensplainer at some point and we had concerns about the installing too. It seemed, we agreed, like an art fair show display. The question is: how do you display all these works like a survey of an idea?

Magda: It is about all the artistic positions that the text referred to. As I said before.

The Bensplainer: If you see such an exhibition, you might consider how it fits a piece of writing, it being a master or a PhD thesis. On the other hand, it really lacks the viewer’s possibility to freely interact with the works. In other terms: how could you translate an idea for an exhibition, if the exhibition itself follows a logocentric and rational process? There is no surprise, indeed: I wanna see something, I don’t wanna learn something.

Victor: This is a kind of philosophy made clear by the exhibition makers: what can art do and how it can utilize itself, in order to convey politics?

The Bensplainer: Do you mean how art can be utilitarian?

Victor: Let’s say you have a curatorial agenda, or an hypothesis: art-making as a precarious condition. And then you, as an exhibition maker, attempt to visualize that. In this sense, these works witness this very aspect, like art illustrating an intellectual point of view.

Magda: Otherwise said, either it is the work that is convincing, or the hypothesis. Right now, it doesn’t seem to be either. About the works I don’t wanna say much, but the text, its arguments can be easily dismantled. In many places, it is simply not coherent. For example, why do you state in the exhibition text that the coronavirus pandemic is what makes visible the rise of social inequalities the exhibition addresses, and then you show works from the 1980s? It makes no sense.

The Bensplainer: Works from the 1980s which recall works from the 1960s.

Magda: Exactly! If you were really consistent with your method, you would research the topic, then find out who’s working with it now. Not the artists who kind of work with the idea… just a little bit, so that they can fit your curatorial idea.

Victor: On the behalf of the curators: why should you do a show like that? What are their motivations?

Magda: Of course, you can do a show addressing the notion of class. There’s nothing wrong about that. Even if it were an illustration of ideas, it could work. But you need a good thesis first, while here the positions that are supposed to illustrate it, are weak. Who liked Laura Ziegler and Stephan Janitzky’s installations?

Victor: As a person who attended some performances by Ziegler and Janitzky previous to the KM show, but not to the last one actually at KM, I would say I see their sculptures as stage props. These performances enchanted or activated their sculptures. So, I’m quite neutral about their works in the show, but at the same time I’m neutral about all the works featured. It seems to me that the show has an agenda in representing all kinds of mediums. Photography, video … like a checklist.

The Bensplainer: Maybe old-fashioned?

Magda: It is a safe agenda. If you take Mark Fisher’s ‘Capitalist Realism,’ he states that museums and related institutions are safe spaces where we can make criticism of capitalism, while capitalism itself allows it.

Victor: Yeah, Roland Barthes already said that. On my part, I am totally opposed to the idea of ‘making art’ as a profession, in the capitalist sense. When paying your rent depends on the money from selling your art, then soon you’ll be under pressure to produce, and that in return, I think, ultimately leads to overproduction and junk.

Magda: Then we ought to know more about the artists and how they position themselves to the capitalist model.

The Bensplainer: I think we are derailing the conversation. I mean, after 1989, there is only one religion, which is capitalism, and you hardly can escape this fact (I agree with Giorgio Agamben on this). Insisting on this leftist nostalgia is counterproductive. Art is luxury. Some artists are fighting against this mindset, but we are still in such a system.

Magda: Indeed – and yet the exhibition promotes an anti-capitalist position. For example, The Coop Fund’s aim is to provide an alternative funding, so that is very clear. Guillaume Maraud is also doing a standard institutional critique by creating an alternative fund.

The Bensplainer: At the same time, these practices are canonized. When KM showed Andrea Fraser in 1993, the questions she raised were novel and on the point. The visuals in this present show are canonized. Stephen Willats repeats a visual language of more established artists, as Hans Haacke for instance.

Magda: Yes, maybe the only thing Willats adds is a British perspective on the problem.

The Bensplainer: Victor, you said on the occasion of our NS-Dokumentationszentrum conversation [link]: „Preaching to the converted.“ Basically, we find here the same pattern. So, you can argue with a lot of reasoning about a motivation for an exhibition – in this case an anti-capitalist agenda – but what I expect is to see works and practices which change the way I see. Sorry if I repeat myself, but seeing works which repeat, without a difference, canonized visual experiences from the past gives me such a kind of déjà vu effect. What is this exhibition about? What are the politics that motivated it? From the point of view of the exhibition making, it is in itself a sort of repetition. In the last Documenta, the assumptions were similar: a lot of nostalgic Marxism and related leftist theoretical positions, which are good, but at the end of the day, the works become an illustration sketched aprioristically by the curators and the artistic director. Here lays the critical point which we really have to address. Paradoxically, if the works are repeating themselves, aren’t also the politics of exhibition making repeating themselves?

Magda: Yes and no. My question is: why are you repeating these positions? You can repeat a practice under the change of circumstances: the pandemic has changed the parameters.

The Bensplainer: I agree: the pandemic has unveiled changes which were not so clear before that.

Magda: So, does the repetition offered in this exhibition reflect that? Does our present context require repetition? How are the works from the 1980s and 1990s relevant now?

The Bensplainer: Let’s be clear: I don’t consider repetition with a negative value. I remember a wonderful group show at KW, Berlin, in 2007, titled ‘History Will Repeat Itself.’ Precisely, it was interesting because it focused on repetition as a visual device, that’s to say how artists and works dealt with the notion of repetition, be it of other works or of overarching experiences. I remember this great video by Jeremy Deller, ‘The Battle of Orgreave’ (2001), directed by Mike Figgis, in which the artist reenacted the famous 1984 clash between workers and police in Orgreave, South Yorkshire, England, and interviewed some participants from both sides too. By the way, it was a ground breaking show, but if you now repeat because it is fashion, a canon, then repeating loses its critical charge. Moreover, works become simply an illustration of the curator’s idea. It seems to me so frustrating now, especially when Anton Vidokle already addressed the question in his seminal and controversial article ‘Art Without Artists?’ on e-flux already in 2010. [link]

Victor: Yeah, that’s what I find problematic with this show: in this time of existential precariousness, how can an artist be critical or be able to question the politics of an exhibition? You’re invited, you get attention and funds, you simply go along with it. The institutions are creating ideological precariousness by wagging with the money. Nonetheless, I see that an artist needs the money. I think it is an inherent issue of institutional exhibition making, but I can’t see an immediate way out of it. It is a trap. The people in the institutions are also paid to play their role, and if they refuse to, replacement will be found quickly.

The Bensplainer: I don’t think that it is the main point here.

Magda: I recognize that there are many artists that suffer contemporary financial precariousness, but there are equally many who do not. Let’s be honest, how many artists, or student artists, may claim that they are coming from working class families? I mean, many are playing the role, but really?

The Bensplainer: I have to check it again, but there is a statistic in Bavaria that states that families on the edge of or below existential and financial poverty who are able to send their kids to higher education are 6 or 7%. That’s a ridiculous percentage, especially because these underprivileged students or artists have then a structural difficulty in order to enter the so-called art system.

Magda: Mid- or upper-class people study art. They come from that comfortable background. At any given time, they may or may not have money, but they indeed have a safety net.

Victor: People that I talked to were missing a critical view on the institution itself and how this show sits within its history and why they did the show there, since the Kunstverein was developed specifically to cultivate an image and space for the bourgeoisie, the middle class, by propagating aesthetic values from the upper class. It was the beginning of the ‘public sphere’ separate from the court, but also was the image of upward mobility and how its members today, generally upper middle class, use the space as a form of patronage and charity as an additive to their cultural capital. So, one might interpret this show as cynical, but I personally think that there is also the possibility of freeing yourself up from that tradition and subverting or bastardizing that project of that middle class of 200 years ago. However, I think that the show is too conventional and there is an opportunity missed here.

The Bensplainer: Sorry if I always bring up my PhD topic about the Russian so-called Avant-Garde. If you analyze it socially, the Avant-Garde cloud was also animated by class and social warfare. Practitioners from the periphery came to the capitals, Moscow and St. Petersburg, and they had to fight with their contemporaries belonging to the urban mid- or upper-class world. For instance, you have Malevich who needs to rent a big apartment for him and his family, in order to sub-let and make a little profit from other people. But he also has to provide meals for them and he can paint only when he has some spare time. You still have today this romantic idea of the Avant-Garde, forgetting that it was also a very hard social situation.

Magda: But, the thing is that the economic or even its symbolic model, doesn’t seem to be really relevant. Class as it was in the 1970s, 1980s or even 1990s doesn’t exist anymore. What about class and technology? You can’t apply for jobs because you don’t have easy access to the Internet, because you don’t own a laptop or a smartphone. You can’t have a flat because you don’t get the notification on time. And flexibility changed the notion of work. There are a lot of structural changes in our societies, which the show’s accompanying text acknowledges clearly, but they are not examined in the work, or at least only in the orthodox leftist way. These positions are repeated nostalgically in the art. To me, the working class today is exemplified by DHL delivery workers.

The Bensplainer: I would add this. Today's working class might also be embodied by wannabe successful TikTok accounts! You may immediately perceive the fakeness in appropriating models from the supposed upper class in order to convey a different idea about yourself.

Magda: Fake it until you make it! TikTok responds to an already established model.

The Bensplainer: The novel level conveyed by TikTok is that it is not about hustling or conning anymore. Everybody knows everything is fake, so everybody accepts the coded rules.

Victor: That’s the classic definition of Žižek’s ‘ideology.’

Magda: Coming back to the show, I was surprised that urgent political issues were not questioned. I mean, the rise of populism is an issue, and it is class oriented. I don’t know much about Berlusconi and his years in power, but he did address the narrative of his politics to a certain class and set up a model for the recent years, didn’t he?

The Bensplainer: We Italians are not recognized in such a way anymore, but we’re still at the verge of the Avant-Garde! If history repeats itself as a farce, after Berlusconi everything is a farce. He had – and to some extent still has – an appeal to the working class, in the sense that he sold a narrative through which you can change your life only by willing it. At his first election run in 1994 he won in working class’ bastions, where traditionally the former Communist Party won with ease, efficiently selling his abstract ideas on liberty through his glittering television sets. So, already then, you might perceive that categories such as the Left and the Right were structurally changing. And this historical and epochal shift, so charged with ideological questions, is totally forgotten in this exhibition.

Magda: Thus, I could have accepted as legitimate the exhibition’s assumptions, even if illustrational, if they would have addressed the ongoing complexity of the topic of populism, digitalization, 0-hours contracts, and so on, all related to an idea of the working class. Then it would have been fair enough!

The Bensplainer: I would add another topic to this. If you consider the state of satire, especially from the US, comedy is way ahead of visual art. It addresses those topics in a much more effective and creative way than visual art is actually doing. Only because they’re really reaching millions of people.

Magda: Yes, John Oliver, for instance.

The Bensplainer: I became a huge fan of Jimmy Kimmel’s late-night monologues in the last two years, because he and his authors adapted his style of comedy shifting from weird Hollywood absurdities to overall US social and political issues. So, his and his authors’ craft reached a new level of satire, and the audience’s awareness. What can visual art do, as powerful as it might be, in comparison to mainstream satire? Let’s simply think about how Kimmel dealt with the topic Obamacare and how he related to – his personal history.

youtube

youtube

Magda: This is important, as access to healthcare in the US especially, is a class issue. But then, yeah, why don’t you simply invite a comedian to KM, then? Ok, you could never afford that, but who knows?

The Bensplainer: It would be so wonderful! But this idea should also be declined in a weirder approach.

Magda: For sure, a comedian in an art space could have more freedom compared to the one he could have on national television.

The Bensplainer: Victor, do you remember Olof Olsson’s performance at Lothringer 13’s cafe in Munich in 2017?

Victor: Yes.

The Bensplainer I found it brilliant, mixing visual and comedy devices, and very generous, because it lasted so long! This kind of transdisciplinary performance says more about social, political and economic issues, than a conventional show, like this one at KM. If I had to make a single critical statement about this show at KM is that it doesn’t move our present cultural perception to a different plane, as satire does.

Magda: My impression is that a student went through their assigned reading list, without going to the library. Everything which was required was read, but no insight was then further researched.

#flaschendrehen#magdawisniowska#thebensplainer#victorsternweiler#kunstvereinmünchen#kunstvereinmuenchen#munich#maurindietrich#gloriahasnay#art#class#stephenwillats#annettewehrmann#josefkramhöller#gilital#angharadwilliams#lauraziegler#stephanjanitzky#coopfund#markfisher#pulp#montypython#johnoliver#jimmykimmel#berlusconi#covid#coronavirus#culturalcapital#culturalwork#capitalism

0 notes

Photo

Aerial #29 | 2012

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aerial #9 | 2012

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Aerial #1 | 2012

6 notes

·

View notes