#Maggie Koerth and Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Abortion

What Americans Can Expect If Abortion Pills Become Their Only Safe Option

By Maggie Koerth and Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux and Maggie Koerth and Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux

Apr. 12, 2022, at 6:00 AM

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY EMILY SCHERER / GETTY IMAGES

The things Desireé Luckey remembers most about finding out she was pregnant for the first time are how fast the little test strip turned positive — and how irritated it made her feel. It was one more hassle in a summer that already felt overwhelming. Within the span of a few weeks in 2012, Luckey had graduated college, ended an emotionally unsafe relationship and started a new — but frustratingly unpaid — job with former President Barack Obama’s reelection campaign. From her dorm bathroom, she immediately began figuring out what she’d need to do to get an abortion.

Kelsea McLain also knew she wanted an abortion as soon as she found out she was pregnant. Graduating college during the Great Recession, she was surviving on unemployment and about to lose her apartment. Both women wanted private, inexpensive abortions. Because of that, they chose medication abortion — two pills that, when taken together, effectively mimic the biology of an early miscarriage. Medication abortion allowed Luckey and McLain to abort their pregnancies at home. It was logistically simpler than going to a clinic for a procedure. It was cheaper. And it was just as safe.

But it can also be terribly painful. McLain suffered through intense cramping, nausea and weeks of heavy vaginal bleeding. Not everyone’s medication abortion is like that — Luckey’s was straightforward and less uncomfortable than periods she’d had, and she was back walking the full parade route at Capital Pride in Washington, D.C., the next day. No one knows ahead of time whether their experience will be more like Luckey’s or more like McLain’s.

In just a few months, many more Americans may be rolling that dice. The Supreme Court is weighing the constitutionality of a Mississippi law that bans most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy, with an opinion expected by June. The court’s conservative majority is expected to make it easier for states to at least restrict abortion access, and it’s possible that it could overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that established a constitutional right to abortion, which would allow states to ban abortion outright. If that happens, a lot more people will be obtaining abortion pills illegally.

Medication can be an effective tool for people trying to evade abortion restrictions, and it’s much safer than other illegal abortion methods. But as abortion access is further restricted, increased reliance on pills could also make more people struggle through an intensely painful — even traumatic — experience, with little access to medical support, lots of stigma and more legal risk than ever before.

For almost three decades after abortion became legal, Americans who wanted to end their pregnancies had one option: an in-clinic procedure. That changed in the fall of 2000, when the Food and Drug Administration approved mifepristone, an abortion-inducing drug that allows people to go through the physical process of an abortion at home. To end a pregnancy, people first take mifepristone, which stops the pregnancy from growing. Then the second drug, misoprostol, which is usually taken 24 to 48 hours later, tells the uterus to expel the pregnancy. According to current FDA regulations, the combination can be used until the 10th week of pregnancy.1

The introduction of the pill sequence transformed abortion in the U.S. At first, it wasn’t an especially popular choice, largely because the FDA imposed lots of restrictions on the medication. But that changed in recent years, in part because of the pandemic. By 2020, the Guttmacher Institute estimated that more than half of abortions in the U.S. were medication abortions.

!function(){"use strict";window.addEventListener("message",(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data["datawrapper-height"]){var t=document.querySelectorAll("iframe");for(var a in e.data["datawrapper-height"])for(var r=0;r

As access to in-person abortion dwindles, medication abortion is more available than it’s ever been. For a long time, the FDA’s regulations said that medication abortion needed to be provided in-person, in a medical setting, but after the rules changed — temporarily at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and then permanently a few months ago — a crop of abortion-focused telehealth companies sprang up with the goal of making the process as seamless as possible. As a result, it’s now possible to get an abortion in more than 20 states without ever setting foot in a clinic. That also means it’s cheaper.

Anti-abortion lawmakers have realized this and are trying to crack down on the mail distribution of abortion pills in several states. A Supreme Court decision to allow states to ban first-trimester abortion would likely increase those attempts to control supply, since it’s a big loophole: Even if abortion is illegal, someone could order abortion pills from a telehealth company in a state where it’s legal and mail them to a person in a state where it’s not, or order pills from an online pharmacy. Access to abortion pills could undermine the coming wave of abortion bans, and everyone knows it.

As medication abortion gets drawn into the political fight over abortion rights, the physical comfort of people seeking those abortions often gets overlooked. The side effects of medication abortion aren’t widely discussed, and it’s easy to understand why. There is lots of misinformation about abortion pills online, and anti-abortion advocates often greatly overemphasize side effects like pain, nausea or bleeding in an effort to make the procedure seem dangerous, which it’s not. In a country where abortion is such an intensely polarized issue, it’s hard to hold two ideas in place at the same time — that medication abortion is very safe, and also sometimes unpleasant to go through.

McLain decided to start her abortion while she was moving out of her apartment. As she carried boxes up and down the stairs, her uterus contracted over and over again, working to expel the pregnancy. She started to bleed — a lot. She threw up. After a while, she began to pass big, heavy blood clots. The pain was unbearable. “There were times that my pain was 10 out of 10,” she said. “I felt like I was going to pass out.” And it didn’t stop after a few hours. It just kept going. “I remember thinking everything was over, and then all of a sudden, bleeding heavily again,” she said. “It was like two weeks where I didn’t trust that my body was actually done.”

She didn’t regret the abortion. In fact, McLain was intensely relieved that the pregnancy was over. But she felt traumatized by the pain, the isolation and the unshakeable feeling that the pain was her punishment for getting pregnant in the first place. The difficulty of the experience felt like something she had to stoically deal with, though in retrospect she thinks her feelings of anxiety and shame actually made the pain worse. “That whole experience, how alone I felt when I didn't need to feel alone, it really just left this lasting impact on me about the injustice of it all,” she said.

But McLain’s experience is not a rare one. Although most clinical trials of medication abortion don’t track it, the few studies that do suggest pain is common. A 2006 systematic review, for example, found that 75 percent of women in five large studies from the U.S. and United Kingdom experienced pain severe enough to be treated with narcotics. In other studies, women consistently reported high levels of pain — with averages ranging from 5.6 on a 10-point pain scale to 8.4 on an 11-point pain scale. “There are people who are still experiencing severe pain, and we need to do additional studies to find ways to help people manage their severe pain at home,” said Dr. Alyssa Colwill, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University who studies pain relief for medication abortion.

And although most people who have gotten medication abortions say they are satisfied with them — as high as 98.4 percent who reported their experience in one study — that may not tell us much about how they felt. When one survey compared medication abortion with the alternative — an outpatient, physical procedure sometimes erroneously called a "surgical abortion" — more people seemed satisfied with the in-clinic option. Colwill said that to her, the high satisfaction numbers for medication abortion are just women “telling us they’re happy they’re no longer pregnant.”

This is part of a larger problem that goes far beyond abortion. In general, gynecological pain isn't well studied or well treated. “Pain, generally in medicine but particularly in obstetrics and gynecology, has been minimized and overlooked, and that's related to misogyny,” said Dr. Daniel Grossman, director of the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health program at the University of California, San Francisco. “There was kind of an assumption that women could tolerate the pain.” This is a pattern that’s well-documented in medicine — women’s pain tends to be undertreated for all kinds of conditions, from chronic illnesses like fibromyalgia to more acute issues like broken bones. Other forms of reproductive care, like IUD insertions, are also notoriously painful for some, with many women reporting that their experiences were just shrugged off.

Part of the challenge is that it’s hard to predict what any one person will experience. Doctors might not want to offer heavy hitting pain medications right away, since it’s possible that the experience will be like Luckey’s — uncomfortable, but not a big deal. But for people who have a lot of pain, the options for relief are not great. McLain, who had her abortion before the opioid crisis made doctors leery of prescribing narcotics, could take the painkiller hydrocodone if things got bad. In the U.K., where the vast majority of abortions are medication abortions, patients who choose to do their abortion at home receive another painkiller, dihydrocodeine, as part of their take-home package.

In the U.S., however, most abortion patients now get a strong dose of ibuprofen — a choice consistent with World Health Organization guidelines. In the studies those guidelines are based on, ibuprofen was the only treatment to consistently produce evidence of reducing pain during a medical abortion, said John Reynolds-Wright, a clinical research fellow at the University of Edinburgh who is currently working to synthesize the evidence on pain management for medication abortion. But that's not the same thing as ibuprofen working well, he told us. And those studies looked at 800- or even 1,600-milligram doses of ibuprofen, much higher than the 400-milligram dose people are used to taking at home.

Pain, as Colwill pointed out, doesn’t necessarily indicate something is unsafe, even though everyone wants to avoid it. But if abortion is banned, people could be taking abortion pills without much medical guidance, and the consequences could be more dire. Several states, including Oklahoma and South Carolina, already have laws on the books that can be used to prosecute people who self-manage abortion. Mary Ziegler, a professor at Florida State University College of Law who studies abortion law, said that because states will find it hard to enforce abortion bans as long as pills can be mailed in discreet packages, more anti-abortion state lawmakers might consider making it a crime to use abortion pills or help someone obtain them.

If that happens, people could end up being prosecuted if they use abortion medications in a state where it's illegal, particularly if they end up going to the hospital. Physically, there's no way for medical professionals to be able to tell the difference between a pregnancy loss induced by abortion drugs and one that happened as part of a miscarriage, Grossman said. And the only way the difference would matter medically is if the patient had induced their abortion with some other substance like an herb concoction, rather than tested, FDA-approved meds.

But that's not information people will necessarily know. In 2018, one group of researchers ordered abortion pills from 16 different websites and found that none of them came with instructions. Some people may make the mistake of telling medical staff about taking abortion meds — and then find themselves in legal trouble. It’s rare for people to be prosecuted for self-managed abortion, but it has happened. “Unfortunately, a lot of the ways that people have been criminalized is through the providers they turn to for help,” said Farah Diaz-Tello, senior counsel at If/When/How, a legal advocacy group that focuses on reproductive justice issues. That happened in 2012 when a woman in Pennsylvania helped her daughter obtain abortion pills online. The daughter later went to the hospital because the pain was so frightening and unexpected. The mother told hospital personnel about the pills, they reported her to child protective services, and she ended up in jail.

Even if it doesn’t end with prosecution, self-managing an abortion can be a scary and isolating experience. That’s a harm that women will have to absorb, too. And even though it has expanded access significantly, medication abortion won’t preserve abortion access if restrictions continue to mount. For one thing, there are limits to how much telehealth abortion companies can help people in states where abortion is illegal. Leah Coplon, the medical director at Abortion on Demand, a telehealth abortion company, said that although it’s very helpful, remote access to medication abortion can’t replace brick-and-mortar clinics. “I hesitate to have telehealth medication abortion seem like a panacea,” she said.

And perhaps most fundamentally, as abortion becomes more restricted, people are losing the ability to decide for themselves what the experience will be like. Luckey and McLain both went on to have other abortions, and their decisions weren’t what you’d necessarily expect. Despite having a good experience with medication abortion, Luckey opted for an in-clinic abortion later, wanting the procedure to be over and done with quickly.

McLain, meanwhile, had two more medication abortions — both of which were less traumatic than the first. By the time she needed another abortion, she was working in reproductive health and felt much less stressed about the whole process. For her, the feeling of being in control and lack of stress changed everything. “It was no big deal,” she said. “I remember the abortion being so completely pain-free and uneventful, I was worried it didn't work.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Until now. Given the way things are changing, the people who study the militia movement and have spent years talking to its members think there’s a risk of American militias becoming more like the militias of other, often politically unstable, countries. “What matters is if the movement becomes essentially a more traditional Latin American pro-regime paramilitary, which seems to be what Trump is trying to create or wants,” Churchill said.

How Trump And COVID-19 Have Reshaped The Modern Militia Movement | FiveThirtyEight

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un mejor control de la natalidad no ha hecho que el aborto sea obsoleto

Un mejor control de la natalidad no ha hecho que el aborto sea obsoleto

Por Maggie Koerth y Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux ¿Ha hecho el control de la natalidad moderno que el aborto sea cosa del pasado? Eso es lo que los abogados del estado de Mississippi quieren que piense la Corte Suprema de EE.UU. En un escrito en el caso pendiente que podría anular el derecho al aborto en todo el país, los abogados de Mississippi escribieron : “[A]un si el aborto alguna vez se consideró…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Link

First reactions from the Five Thirty Eight crew:

Perry Bacon Jr.: Trump Interrupts Biden, Wallace And Americans’ Ability To Follow The Debate

Maggie Koerth: What If The Presidential Debate Was Like the Worst Fight Your Uncles Ever Had At Thanksgiving

Kaleigh Rogers: First Presidential Debate Hits A New Low, In A Year Of Nothing But Lows

Amelia Thomson-Deveaux: Everyone Lost The First Presidential Debate

Nathaniel Rakich: This Was The Worst Debate America Has Ever Had

Geoffrey Skelley: Maybe The Only Debate Takeaway Is That Trump Still Refuses To Say He Will Accept The Results Of The Election

Shom Mazumber: An Anticipated Debate Leaves Much To Be Desired

Micah: 2020 Is Perfectly Encapsulated In First Presidential Debate

Galen: Trump Uses Debate As Metaphor For His Governing Style: Chaos

Chris Jackson: Response On Twitter Suggests No One Wins Race-To-The-Bottom Debate

Meena Ganesan: There Are So Many More Days Left In 2020

0 notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Will you get robbed this year? How would you rate your chances?

Over 10 years, from 1994 to 2004, the national Survey of Economic Expectations asked respondents to do just that. People estimated their risks for a whole host of bad-news life events — robbery, burglary, job loss and losing their health insurance. But the survey didn’t just ask respondents to rate their chances: It also asked whether those things had actually happened to them in the last year.

And that combination of questions revealed something important about American fear: We are terrible at estimating our risk of crime — much worse than we are at guessing the danger of other bad things. Across that decade, respondents put their chance of being robbed in the coming year at about 15 percent. Looking back, the actual rate of robbery was 1.2 percent. In contrast, when asked to rate their risk of upcoming job loss, people guessed it was about 14.5 percent — much closer to the actual job loss rate of 12.9 percent.

In other words, we feel the risk of crime more acutely. We are certain crime is rising when it isn’t; convinced our risk of victimization is higher than it actually is. And in a summer when the president is sending federal agents to crack down on crime in major cities and local politicians are arguing over the risks of defunding the police, that disconnect matters. In an age of anxiety, crime may be one of our most misleading fears.

Take the crime rate. In 2019, according to a survey conducted by Gallup, about 64 percent of Americans believed that there was more crime in the U.S. than there was a year ago. It’s a belief we’ve consistently held for decades now, but as you can see in the chart below, we’ve been, just as consistently, very wrong.

Crime rates do fluctuate from year to year. In 2020, for example, murder has been up but other crimes are in decline so that the crime rate, overall, is down. And the trend line for violent crime over the last 30 years has been down, not up. The Bureau of Justice Statistics found that the rate of violent crimes per 1,000 Americans age 12 and older plummeted from 80 in 1993 to just 23 in 2018. The country has gotten much, much safer, but, somehow, Americans don’t seem to feel that on a knee-jerk, emotional level.

“The biggest challenge really, and we’re seeing this as a society across the board right now, is that even though our organizations, our businesses, our government entities are becoming more data driven, we as human beings are not,” said Meghan Hollis, a research scholar at the Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarship.

That’s not to say that Americans are completely clueless about crime. When we spoke to John Gramlich, a senior writer with the Pew Research Center and one of the people who has been tracking and writing about this disconnect for years, he was quick to clarify that Pew didn’t like to frame Americans’ apparent inability to register their own increased safety as a product of being uninformed or misinformed. The reality, he told us, is that the nature of data collection makes it hard for the public to really assess crime rates and for experts to assess what the public knows or feels about crime rates.

Even the concept of a “crime rate” is messy. When we talk about crime rates in the context of an article like this one, what we’re actually discussing is the number of crimes, in a set of particular categories, that get reported to the police and, from there, to the Federal Bureau of Investigation — or results from a government survey about whether people have experienced crime. These stats document murder, rape, robbery and assault, among others, as well as several property crimes, including burglary, theft, car theft, and arson. That covers a lot of ground, and it gives us a pretty good idea what the crime rate truly looks like — enough that experts feel comfortable saying things like “Hey, look, the crime rate has been going down for 30 years.”

But those statistics don’t tell the whole story, and that matters in ways that become important when you’re trying to understand the difference between how people feel and what the data say. Not all crimes are reported to the police. Sexual assault, in particular, is notoriously underreported. And there are plenty of crimes we don’t really track well in data — like vandalism, drug use and sales, or public intoxication — which can affect how safe people feel in their neighborhoods, even if the crimes aren’t serious.

Wesley Skogan, professor emeritus of political science at Northwestern University, spent much of the 1990s attending neighborhood-level public meetings around Chicago and documenting the issues that residents told police were problems they wanted solved. Some of these issues weren’t even, strictly speaking, crimes, at all. In 17 percent of the meetings, residents asked police to do something about litter. Loud music or other noise-related problems were discussed in 19 percent of the meetings. Residents complained about abandoned cars more often than they complained about gang problems. Skogan thinks about these factors as measurements of social disorder, and has found evidence that these things affect how safe people feel. If violent crimes are down, but there’s still a good deal of social disorder in an area, people’s responses to a survey might reflect how they feel about litter more than how they feel about a reduced murder rate.

The way the polls are worded also don’t help. “The polling tends to be pretty generic,” said Lisa L. Miller, a political scientist at Rutgers University who studies crime and punishment, which makes it hard to capture the difference between how Americans think about murder and litter when it comes to how safe they feel. More importantly, she said, questions like “Do you think crime has gone up or down?” is not the same thing as measuring fear. “When people are genuinely worried about crime and really fearful, it tends to be in relation to violent crime. That’s the thing I’ve found really drives public pressure for the government to do something,” she said.

This whole thing is further complicated because crime is extremely localized — and estimates about the national crime rate are, well, not.

“All the homicides in Chicago occur in about 8 percent of the city’s census tracts,” Skogan said. For almost everybody, he said, that means “the crime you hear about is crime somewhere else.” And that matters because research suggests people are a lot better at estimating the crime rate in their own backyard than they are at estimating what it’s like across town, or across the country.

Finally, there’s the question of race, which permeates and complicates everything surrounding crime. It’s not just trash and loitering that make people perceive a neighborhood as more dangerous regardless of the crime rate. When Lincoln Quillian, a professor of sociology at Northwestern University, analyzed data from three surveys of crime and safety in cities across America, he found that people perceive their neighborhood as more dangerous — regardless of the actual crime rate — if more young Black men live there. That was true for both Black and white respondents of the surveys, but in some cities the effect was significantly more pronounced in white people.

This is all a long-winded way of saying the situation is messy on many levels, but it remains true that people’s personal fear of being victims of crimes and their perceptions of national crime rates are far from accurate.

So why do Americans still think crime is high?

Turns out, the local news may be responsible for convincing Americans that violent crime is more common than it really is. Researchers have consistently found that “if it bleeds, it leads” is a pretty accurate descriptor of the coverage that local television broadcasters and newspapers focus on. For years, rarer crimes like murders received a lot more airtime than more common crimes like physical assault. And that hasn’t changed as the crime rate has fallen.

Understandably, seeing stories about violent atrocities on the news every night seems to make people afraid that the same thing could happen to them. According to one study conducted in California, consumption of local television news significantly increased people’s perceptions of risk and fear of crime. “The news is not going to report on things that are going really well very often,” Hollis said. “It’s not like ‘Hey Austin, Texas doesn’t have a whole lot of crime and that’s our news for the day!'” Stories about gun violence grab attention, so you get more stories about rare, but serious, crimes. “You can have people perceiving areas of cities as much more violent than they actually are because that’s what they see in the news,” she said. “It really amplifies that view of criminal activity beyond what it really is.”

There’s a significant amount of evidence, too, that reporting on crime can prop up harmful stereotypes: Studies have found that local news media disproportionately portray Black people as perpetrators of crime, and white people as victims.

There’s also plenty of fodder for this kind of coverage because even though crime has fallen a lot over the past few decades, the U.S. is still a pretty violent country, at least compared to other developed nations. “Violence remains an American problem,” Miller said. “Just think about mass shootings. So in that sense it’s not irrational for people to be somewhat fearful of violence.”

But often, those fears can be blown out of proportion — not just by wall-to-wall murder coverage on the news, but also by politicians who bring up the crime rate in press conferences and interviews. President Trump is far from the first president to paint a dark vision of crime in American cities, but he is singularly obsessed with the topic, especially now. According to a HuffPost analysis, the vast majority of the ads his campaign aired in the month of July dealt in some way with public safety. In one ad, an elderly woman is robbed as text flashes across the screen reading, “You won’t be safe in Joe Biden’s America.”

And a recent study suggests that Trump’s words could have an effect. Researchers found that news coverage and political rhetoric — as measured by mentions of crime in presidential State of the Union speeches — were significant indicators of whether Americans thought crime was a pressing issue facing the country. The actual crime rate was not. A HuffPost poll conducted from July 22 to 24 found something similar: Only 10 percent of Americans correctly believe that crime has fallen over the past decade, while 57 percent think crime has increased.

Some Americans may be more receptive to tough-on-crime rhetoric than others, of course. Republicans are generally more apt to say that crime is a serious problem facing the country than Democrats. And although Pew analysis of polling data doesn’t uncover big racial differences in perceptions of crime, white and Black Americans likely think about crime very differently because criminal justice has become so inextricably tied to race.

Hakeem Jefferson, a political scientist at Stanford University who studies race and justice, told us that Black people’s views on criminal justice are complex, in part because they’re likelier than other demographic groups to actually live in high-crime neighborhoods and to be victims of crime. In other research, he’s found that some Black people have also internalized negative stereotypes about who commits crime, and may be more likely to embrace punitive solutions as a result. Those perceptions and experiences are hard to capture in public opinion data, but they can do a lot to shape what Black people mean when they tell a pollster that they think crime is a serious issue facing the country. And that’s important, because as the past few decades have shown, Black people are also much likelier to be mistreated by police, experience incarceration or grapple with the challenges of a criminal record.

Regardless of what’s driving fear of crime, though, the fact that it is so out of whack with reality can make it really hard to change people’s minds or reform the criminal justice system. It’s not that an out-of-proportion fear of crime automatically leads people to support more punitive policies — right now, for instance, Americans are mostly not in favor of more money for policing. But these misperceptions can make it harder for reforms to gain traction, particularly if politicians with a big national platform — like Trump — are talking about out-of-control crime at every turn.

It’s not hard, for instance, to imagine that kind of rhetoric being used as a wedge against efforts to restructure local funding for the police. Especially considering that in the past, a fear of crime has been used politically as a reason to oppose criminal justice reforms like reducing incarceration or changing the bail bond system — even though research suggests those reforms don’t increase crime in the long term.

The history of “law and order” campaigns is riddled with dog whistles, and Trump’s recent rhetoric about sending federal agents to combat crime in cities like Chicago arguably falls into this category, according to Justin Pickett, a criminologist at the University of Albany who studies attitudes toward crime and justice. Talking about the dangers of crime, he said, can turn into a cover for racist attitudes.

None of this has made us safer. And ironically, fear of crime can actually lead to other behaviors that put us at greater risk, like buying and carrying guns. If anxiety about crime keeps Americans from embracing different ways of thinking about criminal justice, that may be doing more harm than good, too. For instance, there’s no real evidence that putting more people behind bars contributed to the decrease in crime or that imprisoning fewer people will raise crime. Instead, a mountain of research points in the opposite direction to problems and inequalities linked to mass incarceration.

The trouble is that fear about crime isn’t rational, and it’s hard to convince people to think differently about a problem that they don’t experience on a day-to-day basis anyway. “You can tell Americans that the crime rate is lower today than it was in the 1990s, but it won’t feel real to them,” said Kevin Wozniak, a sociologist at the University of Massachusetts Boston. “That is, unless politicians stop drumming up the crime rate and people stop hearing about murder every night on the local news.”

And that seems unlikely to happen in 2020.

1 note

·

View note

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

In January, Philip McHarris was driving from New Haven to Boston to visit a friend when he saw a familiar sight in his rearview mirror — flashing police lights. It was late at night, and McHarris pulled into a gas station and waited, as he had done many times before, for the state trooper to approach his window. The problem, the trooper said, was the way McHarris had pulled off at an exit. Then he said that the highway where McHarris had been driving was a drug trafficking route, and asked if he could search the car for drugs.

McHarris explained that he was a Ph.D. student in sociology and African American Studies at Yale who had just left campus for the weekend. But while the officer walked away to his car, McHarris quickly took a video of himself and sent it to his mother and sisters. “I said, ‘This cop thinks I’m trafficking in drugs,’” McHarris said. “‘I just wanted to let you know that I tried and I love you. I really tried.’”

Eventually, the officer let McHarris go with a warning. It didn’t spiral into one of the deadly encounters that make the front pages of newspapers, where a Black man is killed at the hands of a police officer. The officer had even been relatively courteous, assuring McHarris that the stop wasn’t the result of racial profiling. But that just reinforced for McHarris how poorly the officer understood the racial dynamics of the interaction — much less the fear he felt throughout the encounter, and couldn’t shake even after he drove away. “What good is it if a cop is being nice to me while asking to search the car?” he said. “What I care about is that I got pulled over in the first place, and I’m sitting here thinking maybe this random gas station is the last thing I’ll see.”

Years ago, McHarris came to the conclusion that because of interactions like this, department-level policing reforms aren’t enough. And as a scholar who studies policing and works alongside the Movement for Black Lives, McHarris is part of a small network of activists who have also spent years working to defund police departments, redistribute the money to other parts of the social safety net, like housing, education and transportation, and create new systems for ensuring public safety. But now their work is suddenly everywhere. After the police killing of George Floyd, the Minneapolis City Council voted to dismantle its police department amid growing calls from protesters to “defund the police.” And it’s not just Minneapolis — officials in Los Angeles, Denver and Portland, Ore., are mulling similar ideas.

The exact meaning of the slogan varies a lot depending on who you ask. Even the Minneapolis city council members who voted to disband say their move comes with qualifications. But broadly, it involves a seismic shift in the way we think about public safety — and who is being kept safe. Some critics of the defunding movement have argued that getting rid of the police would be counterproductive — in their absence, who would keep the streets safe? But McHarris said it’s time to stop tinkering around the edges of a system that many people in heavily policed communities say is causing more harm than good. “These police reforms are implemented over and over again and Black people are still being brutalized and murdered,” he said. “Nobody is saying we can’t have mechanisms to promote safety. It just won’t look like the police.”

Defunding the police is a big departure from the reforms we’ve seen before. But although there are disagreements between activists and researchers about how sweeping change should be, pretty much everyone we spoke with agrees that the system is broken, efforts to measure it are highly flawed, and now is the moment to think big about how to fix it. In many ways, the movement to defund the police is exposing gaping holes in how we measure what good police work really is, and how we gauge a reform’s success. Because after decades of research on policing and police reform, we still don’t know that much about what police are doing, how their presence actually affects the people who experience police violence, and what people in those communities want from reform.

On its surface, large majorities of Americans support “police reform.” But “reform” is vague and gets complicated fast. For one thing, the police aren’t a single entity. There are more than 15,000 law enforcement agencies scattered throughout the U.S., which means that any change has to be piecemeal. And it’s also hard to figure out what departments are actually doing, or how to compare them. Within a single metro area, multiple departments could be operating under different rules or different standards of rule enforcement, and even using different definitions of particular buzzword-heavy reforms like “community policing.”

That lack of uniformity makes it difficult to compare police departments that have implemented similar policies. “To understand if a police reform is actually working the way you want, you need to be able to see what officers do in the field and figure out whether the reform you’re looking at changed that,” said Emily Owens, a criminology professor at the University of California, Irvine. “We don’t really have the data or the studies right now for me to say with confidence, ‘We know that these reforms work and these don’t.’”

What’s more, the data that exists is full of holes — and bias. Even when researchers try to document whether the police are doing a good job or how departments might improve, they’re often conducting those studies using metrics that help tell only part of the story. Policing data is imperfect. Due to a lack of systematic or reliable data on police misconduct, the fact that the data we do have is mostly from police departments themselves, and an emphasis on crime and police presence, it’s liable to miss important variables such as nature of police interactions with the public, or the fact that plenty of illegal or violent behavior happens in places and populations where police aren’t looking for it.

Case in point: The practice of hot spot policing. This is one of the best researched policing techniques and — after some 40-odd randomized controlled trials, by one expert’s count — also the one with the most evidence supporting its effectiveness. The basic idea is that crime is clustered throughout a city or neighborhood, so police should target those areas that see higher levels of crime.

But there are still a lot of unavoidable caveats. For instance, when scientists identify hot spots and measure whether policing in those locations has been effective, what they’re really looking at is crime statistics, said Cody Telep, a criminology professor at Arizona State University. That isn’t necessarily the same thing as measuring safety (real or perceived) in a community, he told us. After all, about half of all violent crimes are never reported to the police at all. So the appearance of a hot spot in the data doesn’t necessarily mean that’s where the most dangerous criminal activity is actually happening — something Telep’s team saw firsthand when it compared the locations of drug-related calls to police in Seattle with drug-related calls to the emergency medical services in the same city. It turns out there was a lot of drug activity the police were missing entirely.

Crime, then, and particularly crimes reported to police, are not a great metric by which to judge where the most crime in a city is happening and how dangerous that area feels to the people who live there. Nor is a reduction in crime the end-all, be-all metric to tell you whether police are doing good work. “Certainly reducing crime is a good metric, but I would add to that, at what cost?” said Rod Brunson, a professor at Northeastern University’s School of Criminology and Criminal Justice.

These statistics also don’t tell researchers anything about what police should be doing in a hot spot — or what police do in communities every day. Researchers have established that it’s effective to spend more time in certain parts of town … but, Telep said, have offered little guidance on what police should do once they’re there.

And even if police were given guidelines on what they should be doing, nobody currently keeps track of metrics that would show what those officers were actually doing. That’s about to change, at least partially — under an executive order issued by President Trump last week, the Department of Justice will begin maintaining an anonymized database of police misconduct. But there’s still a catch: The only time we find out about what police do in their day-to-day work is when someone complains or files a report about it, said Wesley Skogan, professor emeritus of political science at Northwestern University. That means there’s no incentive toward good behavior — even though some research suggests that positive interactions with police can improve public attitudes toward them. “The fact about policing is it’s two people in a car, in the night. What we know about what they do is when they choose to fill out a form,” Skogan said.

But even in the situations where it is possible to get good data on real-world police behavior, whether a reform has been successful depends a lot on your perspective. In general, research tends to focus on metrics that are easy to quantify: Did a reform lead to fewer police killings? Fewer civilian complaints? More fired officers? But those measures don’t really account for the human and social cost of police violence, and they don’t tell us much about whether people in overpoliced communities are actually feeling safer.

Part of the problem is that we don’t have a good way to measure or track the effects of dealing with the police on an everyday basis. But qualitative research can give us a window into how a heavy police presence can stoke feelings of deep mistrust. In a study of young people in Baltimore conducted shortly after the killing of Freddie Gray, Yale sociologist and law professor Monica Bell concluded that although the people she was studying were very concerned about violence in their communities, they didn’t see police as protectors. “It’s not just that people are being brutally beaten or shot and killed by police, it’s the routine, daily messaging of — they are going to be watching you in your neighborhood, they’re going to mace you at your school,” she said. “People will even report that a police officer behaved in the ‘correct’ manner but they still walk away with a deep sense that they’ve experienced a broader racism, a broader sense of exclusion that quantitative measures can’t easily capture.”

Analysis of conversations with people in heavily policed communities by a group of political scientists found a similar result: To the people in the study, the police seemed like they were everywhere — except when their help was actually needed. The deep-rooted perception that the police are there to monitor you, not protect you, is hard both to measure and undo. “There’s a very strong perception that the police are there to protect and serve the white community on the other side of the city or the suburbs,” said Gwen Prowse, a Ph.D. candidate in political science and African American studies at Yale and one of the study authors. “The idea is — if you only see me as a criminal and you don’t see me as a full member of this society, how can you protect me?”

And without input from the people who actually experience police violence, attempts to evaluate police reforms can end up reflecting what the researchers — and not the people who are affected — think is important. “There’s this weird business where people think data can solve everything, but data without thoughtful engagement with the community is actually part of the problem,” said Bocar Ba, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Law School who studies economics and crime.

Use of force is one such example — just as police departments have different definitions of what constitutes “excessive force,” so can researchers. For instance, the idea that there is an “optimal” or “reasonable” use of force may prompt researchers or policymakers to ignore or discount lower-level incidents that were still quite traumatic for the person involved. “Who are the people deciding what an ‘optimal’ use of force is?” said Ba. “Are they the people who are experiencing brutality themselves? In almost all cases, no.”

Meanwhile, researchers are just starting to scratch the surface of how an uneasy and often violent relationship with police shapes other aspects of people’s lives. A recent study of students in an urban Southwest school district found that proximity to police shootings harmed high school students’ performance. That’s in line with other research indicating that having police in schools may actually decrease high school graduation rates. But these types of social costs aren’t easily priced in when researchers evaluate whether a reform succeeded or failed.

It’s becoming increasingly clear, too, that the reforms we’ve already tried are running headlong into other difficult to measure, difficult to fix forces, like police culture. Encounters between police and civilians are often violent because police officers are taught to think of themselves as always being in danger, according to research by sociologist Michael Sierra-Arévalo of the University of Texas. At the same time, Skogan said, police culture tends to discount things people at community meetings say they are actually interested in — like controlling traffic or reducing public drinking — as boring.

These are the kinds of problems that make activists like Arissa Hall, the director of National Bail Out, argue that simply reducing contact between police and civilians, and replacing the police with other community resources, is a much better way to address police violence. There might not be many precedents for disbanding police departments, but the positive effect of reducing police presence and investing in housing and education can already be seen in other places. “Abolishing police departments might seem impractical, but there aren’t police officers on every street corner in affluent white neighborhoods,” she said. “We have actual models and examples of what it means to decenter the police and invest in people’s quality of life.”

There’s a lot of research to support the idea that putting more money into resources that improve people’s lives — like health care, housing and education — can reduce crime. The more nebulous question is how removing funding for police departments will affect public safety. But Jennifer Doleac, an economics professor at Texas A&M University who studies crime, suggested policymakers and researchers should prioritize listening to the experiences of people who are interacting with police and make sure those are taken into account when deciding which policies are implemented and how to evaluate their success.

“Clearly, the system that we have now isn’t working for a lot of people,” Doleac said. “So can I see risks to significantly rolling back funding for police departments? Sure. But there’s also a big, big risk in doing too little right now.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): Last Wednesday, the U.S. Capitol was attacked by a mob of President Trump’s supporters, many of whom had very explicit and not so explicit ties to right-wing extremism in the U.S. There are reports now, too, that there could be subsequent attacks in state capitals this weekend. President Trump’s time in office has undoubtedly had a mainstreaming effect on right-wing extremism, too, with as many as 20 percent of Americans saying they supported the rioters. But as we also know, much of this predates Trump, too. Right-wing extremism has a long, sordid history in the U.S.

The big question I want to ask all of you today is twofold: First, how did we get here, and second, where do we go from here?

Let’s start by unpacking how right-wing extremism has changed in the Trump presidency. How has it?

ameliatd (Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux, senior writer): Well, the first and most obvious thing is that Trump has spoken directly to right-wing extremists. That is to say, using their language, condoning previous armed protests at government buildings and explicitly calling on them to support and protect him. And that, probably unsurprisingly, has emboldened right-wing extremists and made their extremism seem — well, less extreme.

That goes for a wide array of extremists in the U.S., too. I’m thinking, of course, about Trump’s comment after the white supremacist violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, when he said there were “very fine people on both sides.” But Trump has also encouraged white Christian nationalists, anti-government extremists and other groups and individuals that I certainly never thought I’d hear a president expressing sympathy or support for.

jennifer.chudy (Jennifer Chudy, political science professor at Wellesley College): Absolutely, Amelia. And while the actual extremists may represent a small group of the public, the share of Republicans who support their behavior, whether explicitly or implicitly, is not as small. This is, in part, due to mainstream political institutions — like the Republican Party, with Trump at its helm — helping make their mission and behavior seem legitimate.

maggie.koerth (Maggie Koerth, senior science writer): I’ve been talking to experts about this all week, and I think it’s really interesting how even the academics who study this stuff are kind of arguing over the role class plays in it. People like Christian Davenport at the University of Michigan have argued that we should understand that all of this is happening in the context of decades of growing income inequality and political stagnation. In other words, he contends that there are legitimate reasons to be angry at and mistrust the government. But it also seems like this crowd was not even close to being uniformly working class and probably contained people from a range of different backgrounds. And that’s why I liked one of the points Joseph Uscinski at the University of Miami made: We might be seeing a coalescing of two groups: the people who have been actually hurt by that inequality and are angry about it AND the people who are doing pretty well but who feel like somebody might come and take that away. And, of course, both those positions can dovetail very easily into racial animus and white supremacy.

ameliatd: That’s interesting, Maggie. As you alluded to, though, it’s important to be clear that economic anxiety — which was used in the aftermath of Trump’s election to explain why so many Americans voted for a candidate who framed much of his candidacy around animus toward nonwhite people — doesn’t mean that racism or white supremacy isn’t a driving force here, too.

Part of what’s so complex about the mob that attacked the Capitol is that it was a bunch of different people, with somewhat disparate ideologies and goals, united under the “stop the steal” mantra. But underlying a lot of that, even people’s anger over economic inequality or mistrust in institutions, is the fundamental idea that white status and power are being threatened.

jennifer.chudy: There is also just a lot of evidence in political science that racial attitudes are associated with emotions like anger. Two great books, one by Antoine Banks of the University of Maryland and the other by Davin Phoenix of the University of California, Irvine, consider this point in depth. Insofar as right-wing extremists express anger at the system (in contrast to fear or disgust), their anger appears more likely to be motivated by racial grievances than by economic ones.

Additionally, the Republican Party’s base has, for years now, become more racially homogeneous, in part because of the party providing a welcome home to white grievances. But some have argued that this has also been exacerbated by the Democratic Party speaking more explicitly about racial inequality in the U.S., something that wasn’t the case in the 1990s. Regardless, a more racially homogeneous base can make a party’s members more receptive to this type of extremist behavior.

We also can’t underestimate the role that COVID-19 plays here. As Maggie and Amelia suggested in their article from this summer on militias and the coronavirus, many folks are at home and glued to their computers in ways that facilitate this type of organizing. They can burrow themselves into online communities of like-minded folks which may intensify their attitudes and lead to extreme behavior.

Kaleigh: (Kaleigh Rogers, tech and politics reporter): Polling has shown that ideas that previously had been considered extreme, like using violence if your party loses an election, or supporting authoritarian ideas, have definitely become more mainstream.

This is partly due to Trump’s own rhetoric, but also due to the effects of online communities where far-right extremists and white nationalists mingle with more moderate Trump supporters, effectively radicalizing some of them over time.

What’s interesting to me about all of these different factions, though, is there is actually a lot of division among these groups: Many members of the Proud Boys aren’t fans of the QAnon conspiracy, for instance. And a lot of white nationalists don’t like Trump, but they still end up uniting against a perceived common enemy. That’s why you saw people in the mob at the Capitol waving MAGA flags alongside people with clear Nazi symbolism. They are not all white nationalists, but they’re willing to march beside them because they think they’re on the same side.

But in the aftermath of the Jan. 6 attack, those divisions are becoming more stark in these online communities. I’m seeing a lot of infighting over whether planned marches are a good idea, whether they are “false flag” events or traps or whether they should be armed. There just seems to be this heightened anxiety as they draw closer to an inevitable line that they can’t come back from: Biden’s inauguration.

sarahf: That’s a super important point, Kaleigh, on how different extremist groups have rallied behind this. But given how much Trump has directly spoken to right-wing extremists, as Amelia mentioned up top, can we drill in on the violence, as well? It’s not just that different factions have united or that these views have mainstreamed under Trump, but also that there’s been an actual uptick in violence, too, right?

ameliatd: One thing Maggie and I heard from experts on the modern militia movement is that these groups’ activity levels depend on the political context. The uptick in violence under Trump is real, but it’s not something that’s only happened under Trump. There was a surge in militia activity early in Obama’s presidency, too, for example.

maggie.koerth: Very much so, Amelia. The reality is that the right-wing extremism we’re seeing now is a symptom of long-running trends in American society, including white resentment and racial animus. And on top of that, you have these trends interacting with partisan polarization, which means the political left and right (which used to have fairly similar levels of white racial resentment) began to diverge on measures of racial resentment in the late 1980s and now differ greatly.

Kaleigh: Exactly, Maggie. That’s also why the FBI and other experts are particularly concerned about planned militia marches ahead of the inauguration. These groups tend to be much more organized and deliberate in their actions than the mob we saw last week. And because of that, they’re even more dangerous.

ameliatd: Right, so this violence isn’t new. But I do think it’s fair to say that Trump has raised the stakes so dramatically for right-wing extremists that we’d see a throng of them storming the Capitol. A lot of them see him as their guy in the White House!

So when he says, look, this election is being stolen from me, and you’ve got to do something about it, they listen.

jennifer.chudy: That’s true, Amelia, but work in political science shows just how much of this change was afoot prior to Trump’s election. Some tie it to Hillary Clinton talking too much about race during the 2016 election — they argue that this drove away some white voters who had previously voted Democratic (and could do so in 2008 and ‘12 because Obama, despite being Black, did not mention race much during his candidacy). But Clare Malone’s article for FiveThirtyEight on how Republicans have spent decades prioritizing white people’s interests does a great job of tracing these roots even further back.

maggie.koerth: Yeah, I’m really leery of the tendency I’ve seen in the media to act like this is something that started with Trump, or even that started post-Obama. Most of the experts I’ve spoken with have framed this more like … Trump’s escalation of these dangerous trends is a symptom of the trends. We’re talking about a lot of indicators that have been going in this direction since at least the 1980s.

jennifer.chudy: True, Maggie, from the beginning of the Republic, I might argue! But one reason the tie to Trump and Obama is so interesting is that Trump’s baseless claims around Obama’s birth certificate correspond with his debut on the national political stage. So even as there is a long thread of white supremacy throughout American history that has facilitated Trump’s ascension, there may also be a more proximate connection to recent elections, too.

ameliatd: Ashley Jardina, a political scientist at Duke University, has done some really compelling research on white identity politics — specifically how the country’s diversification has created a kind of “white awareness” among white Americans who are essentially afraid of losing their cultural status and power.

This is a complicated force — she’s clear that it’s not exactly the same thing as racial prejudice — but the result is that many white people have a sense that the hierarchy in which they’ve been privileged is being upset, and they want things to return to the old status quo, which of course was racist. And the Republican Party has been tapping into that sense of fear for a while. Trump’s departure was that he started doing it much more explicitly than previous Republican politicians had mostly done.

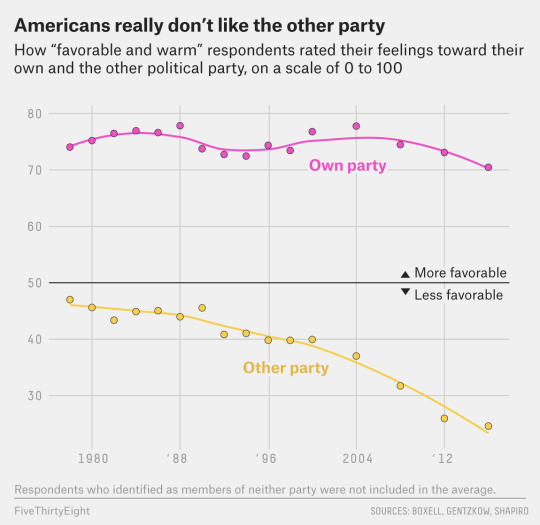

So yes, Maggie, you’re absolutely right that it’s not like Trump came on the scene and suddenly right-wing extremism or white supremacist violence became a part of our mjui78 political landscape. Or partisan hatred, for that matter! FiveThirtyEight contributor Lee Drutman has written about the effect of political polarization and how it’s created intense loathing of the other party, and he’s clear that it’s been a long time coming. It didn’t just emerge out of nowhere in 2016, as you can see in the chart below.

On the other hand, though, it’s hard to imagine the events of last week without four years of Trump fanning the flames.

maggie.koerth: Right, Amelia. Trump is a symptom AND he’s making it worse. At the same time.

Kaleigh: What you said, Amelia, also speaks to just how many Trump supporters don’t consider themselves racist and find it insulting to be called so. A lot of Trump supporters think Democrats are obsessed with race and identity politics, and think racism isn’t as systemic of a problem as it is. There are also, of course, nonwhite Trump supporters, which complicates the image that only white working-class Americans feel threatened by efforts to create racial equality.

ameliatd: That’s right, Kaleigh. We haven’t talked about the protests against police brutality and misconduct this summer, but I think that’s a big factor here as well — politicians like Biden saying that we have to deal with systemic racism is itself threatening to a lot of people.

sarahf: It does seem as if we’re in this gray zone, where so much of this predates Trump, and yet Trump has activated underlying sentiments that were perhaps dormant for at least a little while. Any child of the 1990s remembers, for instance, the Oklahoma City bombing and Timothy McVeigh, who held a number of extreme, anti-government views, or the deadly standoff between federal law enforcement officials and right-wing fundamentalists at Ruby Ridge.

And as Jennifer pointed out with Malone’s piece, the thread runs even further back. It’s almost as if it’s always been part of the U.S. but maybe not as omnipresent. That’s also possibly naive, but I’m curious to hear where you all think we go from here — in how does President Biden start to move the U.S. forward?

maggie.koerth: Honestly, that’s the scary part for me, Sarah. Because I don’t really think he can. Everything we know about how you change deeply held beliefs that have to do with identity suggests that the appeals of outsiders doesn’t work.

jennifer.chudy: Yes — one would think that a common formidable challenge, like COVID-19, would help unite different political factions. But if you look at the last few months, that’s not what we see.

maggie.koerth: Even Republican elites who they push back on this stuff get branded as apostates.

ameliatd: And there’s evidence that when Republican elites are perceived as apostates, they may also become targets for violence.

Kaleigh: But we also know that deplatforming agitators helps reduce the spread of their ideas and how much people are exposed to/talk about them. Losing the presidency is kind of the ultimate deplatforming, no?

jennifer.chudy: Is it deplatforming, though? Or is it just moving the platform to a different setting? I don’t know the ins and outs of the technology, but it seems like the message has become dispersed but maybe not extinguished.

sarahf: That’s a good point, Jennifer, and something I think Kaleigh hits on in her article — that is, this question of … was it too little, too late?

maggie.koerth: I think it has been a deplatforming, Jennifer. If for no other reason than it’s removed Trump’s ability to viscerally respond to millions of people immediately. And you see some really big differences between the things he said on Twitter about these extremists last week and the statements he’s made this week, which have had to go through other people.

It’s not so much taken away from his ability to speak, but it does seem to have affected his ability to speak without somebody thinking about the consequences first.

ameliatd: There is an argument that Trump’s presidency and the violence he’s spurred is making the underlying problems impossible to ignore. I’m not sure whether that makes it easier for Biden to deal with them, but it does make it harder for him to just say, ‘Okay, let’s move past this.’

Lilliana Mason, a professor at the University of Maryland who’s written extensively about partisan discord and political violence, told me in a recent interview that while someone like Biden shouldn’t be afraid to push back against Trump or his followers because it will lead to more violence (an argument against impeachment that’s circulated in the past week), she does think pushing back against Trump and his followers probably will result in more violence.

So that leaves us, and Biden, in a pretty scary place.

Republicans are in a bind, too. Electorally, many of them depend on a system where certain voters — white voters, rural voters, etc. — do have more power. So yeah, Sarah, that doesn’t make me especially optimistic about a big Republican elite turnaround on Trumpism, separate from the question of whether that would actually diffuse some of these tensions.

sarahf: One silver lining in all this is we don’t yet know the full extent to which Trump and Trumpism has taken a hit. That is, plenty of Republicans still support him, but his approval rating has taken a pretty big hit, the biggest since his first few months in office in 2017 — that’s atypical for a president on his way out the door. More Republicans also support impeachment of Trump this time around.

There is a radicalized element here in American politics — and as you’ve all said — it isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, but I do wonder if we still don’t fully understand where this goes next.

Kaleigh: What gives me some peace in this time is looking back at history. America has dealt with far-right extremists before. It has dealt with violent insurrectionists before. We have continued, however slowly, to make progress. Sometimes the only way out is through.

1 note

·

View note

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

For a newsroom like FiveThirtyEight’s, 2019 may as well been part of 2020. Such is the peril of covering electoral politics. But before 2020 actually arrives, we wanted to take a moment and remember some of our favorite features from the past year that the news cycle hasn’t rendered obsolete. There was a lot of good stuff! This isn’t a comprehensive list, but it’s a good place to start.

Politics

“Just because Republicans aren’t winning in cities doesn’t mean that no Republicans live there,” Rachael Dottle wrote earlier this year. Using historical vote data, she showed where every city’s Republican enclaves were, and which cities were the most politically segregated.

Clare Malone went home to Cleveland’s suburbs to examine how the 2016 election laid bare political differences among white Americans. Clare found that the fissures had been lying in wait for decades.

How do you measure a gerrymandered district? Ella Koeze and William Adler showed how math can help expose which districts have been manipulated along partisan lines.

Black politicians on the local level live different political lives than black politicians who want to be president. In August, Perry Bacon Jr. dug into why that is.

Acitivists who want to restrict access to abortion made some progress on the state level this year. Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux categorized hundreds of abortion restrictions to show why the anti-abortion movement is escalating.

Automatic voter registration is a recent hobbyhorse of progressive activists. But is it the panacea it’s made out to be? Nathaniel Rakich looked at what happened when 2.2 million people were automatically registered to vote.

We’re told over and over again that politicians need to appeal to centrist moderates if they hope to win nationally. But Lee Drutman’s analysis suggests that narrative isn’t true. The moderate middle is a myth.

Clare Malone spent weeks tailing former Vice President Joe Biden to understand a contradiction at the center of his presidential campaign: black voters provide a lot of his support, but one of his biggest vulnerabilities is his record on race.

Scott Olson / Getty Images

Speaking of Biden, it can sometimes seem like it’s tough to dislodge a primary front-runner. But Geoffrey Skelley chronicled all the other front-runners who haven’t won. The list is long.

Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux and Dan Cox wrote about one more way millennials are different than boomers: they’ve left religion behind, and they’re probably not coming back.

In the very first House vote on impeachment, to simply formalize the process, Perry Bacon Jr. identified the political faultlines that would define the inquiry into the Ukraine scandal. Hint: They had to do with partisanship.

Does it seem to you like President Trump’s job approval ratings hardly budge? Well, that’s true. But Geoffrey Skelley looked at how unusual Trump’s ratings are historically.

The number of women in the Democratic field this cycle is unprecedented. And we don’t have any research on how sexism might affect such a race. But that doesn’t mean we know nothing about sexism’s electoral impact — Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux and Meredith Conroy put together a link-heavy introduction to what we know already, and how that could influence the 2020 primary.

Sports

We try and find overlap between politics and sports wherever we can, but that doesn’t mean we’re always good at knowing which is which. Earlier this year Tony Chow quizzed us on whether color commentary happened after a game or after a Democratic primary debate.

“Space Jam 2” is coming, and we’re hoping to be LeBron James’s casting director. We used our NBA metrics to cast the true successors to the cast of the original “Space Jam” movie.

It’s always tough to measure how good a defender is in the NFL. But Michael Chiang figured out a clever new way: look at where opposing offenses aren’t throwing.

JEAN WEI

How many clichés are in your average college fight song? We tried to figure out the answer.

Chris Herring attempted to solve one of the great mysteries of the NBA: “Why are there so many bats at Spurs games?”

Another big mystery: How do you accurately evaluate college quarterbacks for the pro game? Josh Hermseyer looks at how the NFL does it (poorly), and offers some alternative solutions.

EMILY SCHERER / GETTY IMAGES

Some people watch the Super Bowl for the football, and some people watch it for the halftime show. Gus Wezerek belongs to the latter, and he used data to rank 25 years of Super Bowl halftime shows.

How national is your college football team’s fanbase? And why is a random county in South Dakota buying so many USC tickets?

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred has been on a warpath against the parts of baseball he thinks are slowing down the game. Travis Sawchik found a culprit Manfred hasn’t targeted: foul balls.

It’s still relatively early in the 2019-20 NBA season, but the pairing of LeBron James and Anthony Davis on the Los Angeles Lakers has been really good. Actually, Neil Paine found that it’s been historically great.

We put Nate Silver in a dinosaur costume.

Other gems

SONNIE KOZLOVER

Most personality quizzes on the internet are bunk. This one is backed by science.

Conspiracy theories permeate our politics and culture. But get used to them. Maggie Koerth wrote that they can’t be stopped.

We publish a lot of forecasts here at FiveThirtyEight. But are they any good? Jay Boice and Gus Wezerek collected virtually every forecast FiveThirtyEight has ever done to find out. The short answer: Yes, they’re pretty good.

Christie Aschwanden had simple advice for those who work out: you don’t need sports drinks to stay hydrated.

0 notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

In the video, the host of a local independent news radio program surveys the late-night shadows of a Kenosha, Wisconsin, car lot. You can just make out four men, long rifles in their hands, as they pace on top of the building. “We got militia on the roof here, and it’s pretty neat,” he says. On the ground, the videographer chats with other people he identifies as part of “the militia” — including an eager and excited-looking kid who tells the videographer his name is Kyle.

Kyle Rittenhouse would go on to allegedly kill two people and injure a third later that night. In the aftermath, the extent of his ties to militia activity — and militia activity itself — have been widely discussed: Are militias hate groups? Was Rittenhouse actually a part of a formal militia group? When people who identify as militia members show up in the middle of a protest … whose side are they on?

For the purposes of this article, when we refer to the militia movement, we are referring to an umbrella term that encompasses paramilitary activists and groups with strong anti-government leanings. But beyond that, modern militias are hard to explain and categorize — what even counts as a militia is up for debate. One thing is for sure: There is no one militia — not in Kenosha that night and not anywhere in the country. Instead, experts say, “the militia” is really a multifaceted movement with fluid boundaries. The key to understanding that movement’s role in the chaos of 2020 is knowing just how difficult it can be to pin down what apparent militia members believe — much less how they’re connected to each other and the broader movement.

While established militias are kind of like a heavily armed scout troop — formal organizations with ranks and membership dues and training programs and regular meetings — some academics argue that many people who are falling into the militia movement’s orbit these days are more like loosely affiliated individuals. “Members” is a strong word for this kind of community, with lots of people drifting along, sharing memes online or showing up, guns in tow, to protests — despite having no clear ties to any specific group. Even the organized, club-like militias don’t ascribe to a single overarching ideology, which makes it especially difficult to figure out what motivates individuals like Rittenhouse, or even how to describe them. “It’s almost like people are choosing their own adventure,” said Oren Segal, vice president of the Center on Extremism at the Anti-Defamation League.

So a crowd like the one that showed up in Kenosha can be made up of individuals, even strangers, with little connecting them except a shared interest in gun rights and a sense that they’re the only ones who can protect their community. And in these trying times — amid a pandemic and protests against racial injustice, plus a president who is giving them more public support than they’ve ever had from the national political establishment — those individuals are taking a collective turn in a direction that, experts fear, is likely to result in more violence.

An armed militia — or even a lone individual with ties to the militia movement — is not, of course, unique to 2020 or even the Trump era. Experts who study modern militias quibble over when the movement actually emerged, but most whom we spoke to date it to the late 1980s and early 1990s, when paramilitary groups and self-described “sovereign citizens” (who believe they, and not the government, get to decide which laws they follow) began to organize, partially in response to the deaths of political dissenters in Waco, Texas, and Ruby Ridge, Idaho. These groups didn’t bear much resemblance to the colonial-era militias mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, but they had a few things in common — specifically, anger at the federal government, and a strong belief in their individual right to own weapons and use those weapons to defend themselves against perceived government overreach or a threat to their community.

How the various members of the movement define that threat is where things get muddy. For instance, some — but not all — militia members are also part of the white power movement, and see themselves as part of a struggle against the federal government that would eventually lead to a race war. Other parts of the militia movement, conversely, have explicitly rejected the white supremacist label. But that doesn’t mean that their members don’t hold racist views. And the decentralized nature of the movement has made it easy for militia groups or leaders to disavow individual people who committed acts of violence, even when they were likely influenced by some part of the movement’s ideology. Social media has made it even easier for someone with a passing interest to find out about militias online, and get involved — even tangentially — in whatever part of the movement fits their ideology and goals.

“People are organizing more around concepts and less around groups,” Segal told us. Some people might be pro-police; others might be anti-police. Some might be libertarian, others might be trying to stoke a race war. “They identify with an ideology, maybe with a movement. But not everyone is going to be part of Militia Group A, B or C,” he said.

The rise of President Trump, and the tumultuous events of 2020, have made it even more difficult to untangle what militias are doing and what their individual adherents believe. From the beginning of his candidacy, Trump’s rhetoric — his attacks on the “deep state” or the anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant insults that peppered his tweets and speeches — have resonated with and garnered public responses from people within the militia movement. When Trump tweeted about an impending civil war or warned about threats from the left, it brought extremist theories and conversations into the national conversation. “With Trump, the fringe entered the mainstream,” said Lawrence Rosenthal, the chair and lead researcher of the Berkeley Center for Right-Wing Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

The pandemic — and the racial injustice protests that have roiled cities throughout the summer — appear to have brought even more people into the militia movement’s orbit. Suddenly, people were at home all day, feeling anxious and fearful about the future and spending a lot more time online. Many in the militia movement chafed at state lockdown orders, and started appearing, heavily armed, at state capitols across the country to protest what they saw as an assault on their individual freedoms. “It’s the same central narrative about government tyranny: ‘I have the right to get a haircut, you don’t have the right to tell us we have to shelter in place,’” said Cynthia Miller-Idriss, a sociologist at American University, where she runs the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab.

The same messages were echoing across internet forums and Facebook groups, including among more loosely organized corners of the militia movement, prompting people who weren’t part of formal militia groups to show up. And they didn’t just appear at protests of government lockdowns — militia members also materialized at the protests of police brutality that sprang up in the wake of the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. People in that city are still arguing, months later, over whether those people were supporting protesters, supporting police, simply trying to incite violence, or some combination thereof.

Many of those people might never have met before in real life, but they sported signs of a shared identity, like Hawaiian shirts, the emblem of the apocalyptic “Boogaloo” movement, an amorphous online militia that has been described as a “meme-based insurgency.” “Boogaloo” identifiers aren’t held together by a coherent ideology — or even a shared sense of what it means to don a Hawaiian shirt. But their ranks have swelled quickly since the pandemic began, according to research by the Network Contagion Research Institute and others. And what these individuals do have in common is a tendency to be armed to the teeth in situations where tensions are already very high. For obvious reasons, that increases the likelihood of a violent confrontation.