#MFMM colur themes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Colours of the Crypt

Once upon a time I blogged about the colours in various episodes of the MFMM series, using Goethe’s Theory of Colour to frame the various analyses: MFMM colour themes.

I thought it might be about time to attempt the same for The Crypt, given the extraordinary settings, contrasting locations and vibrant spectrum of colours of the film, and what they might tell us about the dramatic and aesthetic narratives.

Goethe’s theory was that colour is a sensory interpretation shaped by perception as well as elements of light and darkness. Unlike Newton’s scientifically-based theory, Goethe argued that colour needs darkness, and that most colours contain elements of it:

Light and darkness, brightness and obscurity, or if a more general expression is preferred, light and its absence, one necessary to the production of colour . . . colour itself is a degree of darkness. (Goethe, Zur Farbenlehre, 1810)

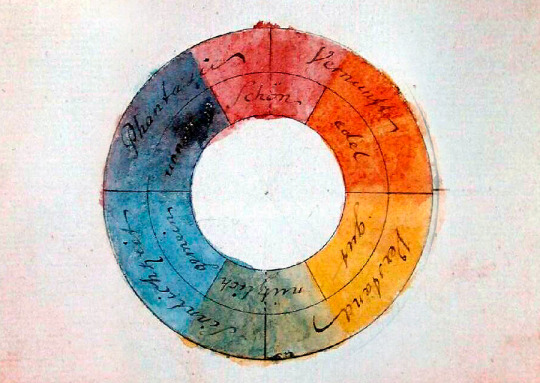

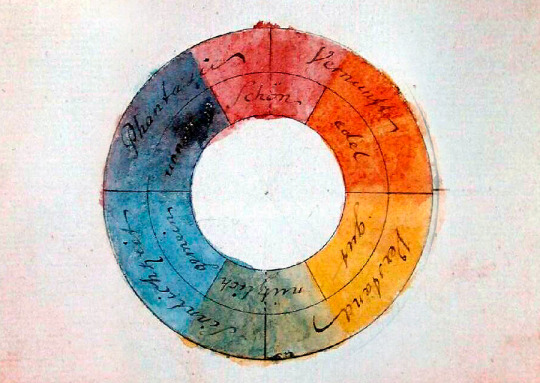

Goethe’s Colour and symbolic wheel (1809)

Part 1: A line in the sand

Goethe based his colour wheel and published writings on a yellow/blue polarity; that yellow and blue are the only pure colours; all other colours are degrees of these two.

Yellow is a light which has been dampened by darkness; blue is a darkness weakened by the light.

This yellow/blue polarity and its manifestation in shades, tones and hues of the natural and built environments, the garbs and settings of The Crypt of Tears, bring this duality into focus.

In Goethe’s colour wheel, yellow (good ’gut’) is the colour closest to light, and therefore both ‘pure and beautiful ... serene, gay, softly exciting’. But he acknowledges too the impact of combinations, of blending and shading, which he claims can produce ‘a very disagreeable effect’. The soft, stark and muted tones of desert towns, villages and landscapes represent, while not always disagreement, wariness and foreboding.

By a slight and scarcely perceptible change, the beautiful impression of fire and gold is transformed into one not undeserving the epithet, foul; and the colour of honour and joy reversed to that of ignominy and aversion.

Of blue (common ‘gemein’) he also suggests some caution:

As yellow is always accompanied with light, so it may be said that blue still brings a principle of darkness with it.

This colour has a peculiar and almost indescribable effect on the eye. As a hue it is powerful — but it is on the negative side, and in its highest purity is, as it were, a stimulating negation. Its appearance, then, is a kind of contradiction between excitement and repose.

The opening scenes of The Crypt provide an opportunity to consider the contrasting effects of the two pure colours. Jerusalem, in British-occupied and administered Palestine, is set in the yellow-browns of mudbrick and cobblestones, of ‘ignominy and aversion’, and this provides a backdrop to the complexity of the intrigue that is to follow.

Phryne erupts onto this scene in a tribute to blue’s ‘excitement’, robes whirling, glittering and billowing in her escape from the local administrative officers who are suspicious of her motives for being in Jerusalem. Her abaya and niqab with coin face veil contrast the muted, sandy tones of the squares, high walls and alleyways where the escapee jostles with crowds, donkey carts, baskets of commerce and motorbikes.

Her silhouette against a pure blue sky highlights the contrast.

Indeed as if to reinforce Goethe’s yellow/blue polarity, Phryne abandons her blues for yellow’s purest form, 'the beautiful impression of fire and gold’ and the scene is set for the next escapade, to rescue the young dissident, Shirin, held in prison for her anti-colonial views. Fire and gold from pistol to toe.

The yellow/blue contrast is reinforced in the scenes of Shirin’s imprisonment; the blue of her robes mirroring Phryne’s earlier dress, distinct from the dull yellow mudbrick prison, the walls and cobblestones of the square and the desert beyond.

The blue of Shirin’s robes are a recurring motif, not limited to her incarceration but always reflecting its distinction from her surrounds. in her memories of earlier times, Goethe’s description of blue generating the ‘kind of contradiction between excitement and repose’ is brought into sharp relief. In each of the flashbacks of her childhood in a village in the Negev, blue dominates the sandy backdrop of social life and interactions.

These early memories evince repose: the calm and order of village life and her relationship with her mother. They reveal love, warmth, closeness as well as indications of future agency.

Shirin recalls a task assigned to her, that of collecting honey from the hives on the hills above the village. Although the purpose was unclear, she knew that one day the tradition would be revealed to her by her mother. The image of her journey on the fateful day of the attack foreshadows markers in a later scene.

Away collecting honey saved Shirin’s life just as its role was the preservation of another young woman. Her absence distanced her from the sudden and shocking assault which decimated her family and the entire village. In her recollections, the blue of sky and robes is set against the gold of honey pot and honey; the shattered ceramic and spilled contents parallel the death and destruction in the village below.

As the sandstorm engulfs the village and the curse is set in motion, Shirin’s only desire is to be enveloped within it, the blue to be absorbed into the raging ochre dust.

Part 2: Rapprochement

Maybe it’s too long a bow to draw to use a term usually associated with international relationships, but I’ll linger a little longer on the metaphor anyway. We need to consider the alliance between the central duo of the film, Phryne and Jack. An entente cordiale between them is necessary to reconnoitre with a stranger, explain a mystery, break a curse, unravel a crime and, ultimately, resolve a romance.

Phryne interrupts her own memorial service with a spectacular entrance in a yellow/blue dichotomy (aka biplane).

The rapprochement gets off to a rather shaky start: Jack is hurt, Phryne bemused.

J: Do you have any idea what it was like for me... reading that you'd died a horrible death in a foreign country?

P: Why are you so angry?

J: I wrote a eulogy for you.

P: My apologies for the wasted effort.

J: Oh, don't worry. It won't be wasted. I'll save it for the appropriate day.

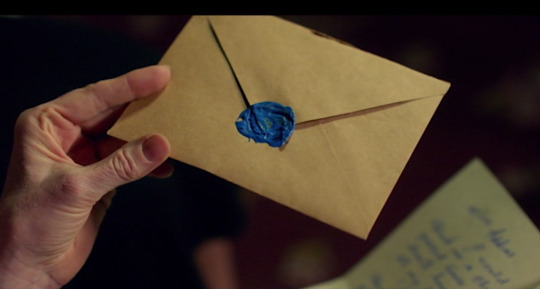

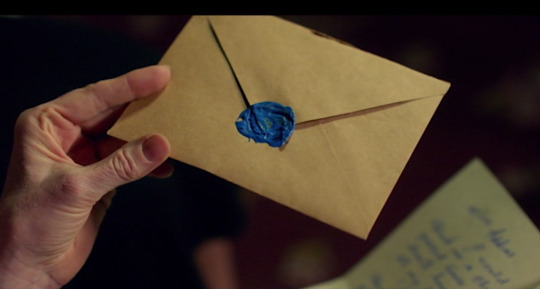

It isn't long before circumstances see their reaching an agreement to prolong the colour scheme, brokered by a mysterious sealed missive, encounters in rain-drenched alleyways, and in a journey across the Negev to find the site of Shirin’s village and the key to an ancient curse.

For Phryne and Jack this means some stunning silhouettes both in London and abroad. A precursor to purple rain perhaps:

Any mutually-acceptable, bi-lateral agreement requires time, patience and some give and take in the negotiations.

The desert landscape, like those of Jerusalem and in the scenes of Shirin’s childhood village, constantly reinforce the complementarity of sky and sand. Goethe’s ignominy and aversion of muted yellow and stimulating negation and contradiction of blue accompany the journey.

There are traps for the unwary: a dishonest cameleer for example ...

And in policy positions, stated and ceded:

P: Well, maybe I'll be absolutely fine without having to explain myself to you or any other man. And if I need your help, I'll ask for it.

J: I won't hold my breath.

P: Jack?

J: Don't worry about it.

P: I need your help! It's quicksand!

But the film isn't just about ignominy and aversion, negation and contradiction. Goethe’s colour wheel can provide the methodology for more insights - other symbols, senses and emotions circle around, wheeling about plot and character. What of red and green, purple and silver, ebony and ivory? Now there’s some food for thought.

To be continued...

#crypt of tears#MFMM#colour palette#yellow and blue#Goethe's theory of colour#parts 1 and 2#MFMM colur themes

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

🥰💖🥺

Colours of the Crypt

Once upon a time I blogged about the colours in various episodes of the MFMM series, using Goethe’s Theory of Colour to frame the various analyses: MFMM colour themes.

I thought it might be about time to attempt the same for The Crypt, given the extraordinary settings, contrasting locations and vibrant spectrum of colours of the film, and what they might tell us about the dramatic and aesthetic narratives.

Goethe’s theory was that colour is a sensory interpretation shaped by perception as well as elements of light and darkness. Unlike Newton’s scientifically-based theory, Goethe argued that colour needs darkness, and that most colours contain elements of it:

Light and darkness, brightness and obscurity, or if a more general expression is preferred, light and its absence, one necessary to the production of colour … colour itself is a degree of darkness. (Goethe, Zur Farbenlehre, 1810)

Goethe’s Colour and symbolic wheel (1809)

Part 1: A line in the sand

Goethe based his colour wheel and published writings on a yellow/blue polarity; that yellow and blue are the only pure colours; all other colours are degrees of these two.

Yellow is a light which has been dampened by darkness; blue is a darkness weakened by the light.

This yellow/blue polarity and its manifestation in shades, tones and hues of the natural and built environments, the garbs and settings of The Crypt of Tears, bring this duality into focus.

In Goethe’s colour wheel, yellow (good ’gut’) is the colour closest to light, and therefore both ‘pure and beautiful … serene, gay, softly exciting’. But he acknowledges too the impact of combinations, of blending and shading, which he claims can produce ‘a very disagreeable effect’. The soft, stark and muted tones of desert towns, villages and landscapes represent, while not always disagreement, wariness and foreboding.

By a slight and scarcely perceptible change, the beautiful impression of fire and gold is transformed into one not undeserving the epithet, foul; and the colour of honour and joy reversed to that of ignominy and aversion.

Of blue (common ‘gemein’) he also suggests some caution:

As yellow is always accompanied with light, so it may be said that blue still brings a principle of darkness with it.

This colour has a peculiar and almost indescribable effect on the eye. As a hue it is powerful — but it is on the negative side, and in its highest purity is, as it were, a stimulating negation. Its appearance, then, is a kind of contradiction between excitement and repose.

The opening scenes of The Crypt provide an opportunity to consider the contrasting effects of the two pure colours. Jerusalem, in British-occupied and administered Palestine, is set in the yellow-browns of mudbrick and cobblestones, of ‘ignominy and aversion’, and this provides a backdrop to the complexity of the intrigue that is to follow.

Phryne erupts onto this scene in a tribute to blue’s ‘excitement’, robes whirling, glittering and billowing in her escape from the local administrative officers who are suspicious of her motives for being in Jerusalem. Her abaya and niqab with coin face veil contrast the muted, sandy tones of the squares, high walls and alleyways where the escapee jostles with crowds, donkey carts, baskets of commerce and motorbikes.

Her silhouette against a pure blue sky highlights the contrast.

Indeed as if to reinforce Goethe’s yellow/blue polarity, Phryne abandons her blues for yellow’s purest form, ’the beautiful impression of fire and gold’ and the scene is set for the next escapade, to rescue the young dissident, Shirin, held in prison for her anti-colonial views. Fire and gold from pistol to toe.

The yellow/blue contrast is reinforced in the scenes of Shirin’s imprisonment; the blue of her robes mirroring Phryne’s earlier dress, distinct from the dull yellow mudbrick prison, the walls and cobblestones of the square and the desert beyond.

The blue of Shirin’s robes are a recurring motif, not limited to her incarceration but always reflecting its distinction from her surrounds. in her memories of earlier times, Goethe’s description of blue generating the ‘kind of contradiction between excitement and repose’ is brought into sharp relief. In each of the flashbacks of her childhood in a village in the Negev, blue dominates the sandy backdrop of social life and interactions.

These early memories evince repose: the calm and order of village life and her relationship with her mother. They reveal love, warmth, closeness as well as indications of future agency.

Shirin recalls a task assigned to her, that of collecting honey from the hives on the hills above the village. Although the purpose was unclear, she knew that one day the tradition would be revealed to her by her mother. The image of her journey on the fateful day of the attack foreshadows markers in a later scene.

Away collecting honey saved Shirin’s life just as its role was the preservation of another young woman. Her absence distanced her from the sudden and shocking assault which decimated her family and the entire village. In her recollections, the blue of sky and robes is set against the gold of honey pot and honey; the shattered ceramic and spilled contents parallel the death and destruction in the village below.

As the sandstorm engulfs the village and the curse is set in motion, Shirin’s only desire is to be enveloped within it, the blue to be absorbed into the raging ochre dust.

Part 2: Rapprochement

Maybe it’s too long a bow to draw to use a term usually associated with international relationships, but I’ll linger a little longer on the metaphor anyway. We need to consider the alliance between the central duo of the film, Phryne and Jack. An entente cordiale between them is necessary to reconnoitre with a stranger, explain a mystery, break a curse, unravel a crime and, ultimately, resolve a romance.

Phryne interrupts her own memorial service with a spectacular entrance in a yellow/blue dichotomy (aka biplane).

The rapprochement gets off to a rather shaky start: Jack is hurt, Phryne bemused.

J: Do you have any idea what it was like for me… reading that you’d died a horrible death in a foreign country?

P: Why are you so angry?

J: I wrote a eulogy for you.

P: My apologies for the wasted effort.

J: Oh, don’t worry. It won’t be wasted. I’ll save it for the appropriate day.

It isn’t long before circumstances see their reaching an agreement to prolong the colour scheme, brokered by a mysterious sealed missive, encounters in rain-drenched alleyways, and in a journey across the Negev to find the site of Shirin’s village and the key to an ancient curse.

For Phryne and Jack this means some stunning silhouettes both in London and abroad. A precursor to purple rain perhaps:

Any mutually-acceptable, bi-lateral agreement requires time, patience and some give and take in the negotiations.

The desert landscape, like those of Jerusalem and in the scenes of Shirin’s childhood village, constantly reinforce the complementarity of sky and sand. Goethe’s ignominy and aversion of muted yellow and stimulating negation and contradiction of blue accompany the journey.

There are traps for the unwary: a dishonest cameleer for example …

And in policy positions, stated and ceded:

P: Well, maybe I’ll be absolutely fine without having to explain myself to you or any other man. And if I need your help, I’ll ask for it.

J: I won’t hold my breath.

P: Jack?

J: Don’t worry about it.

P: I need your help! It’s quicksand!

But the film isn’t just about ignominy and aversion, negation and contradiction. Goethe’s colour wheel can provide the methodology for more insights - other symbols, senses and emotions circle around, wheeling about plot and character. What of red and green, purple and silver, ebony and ivory? Now there’s some food for thought.

To be continued…

#crypt of tears#mfmm#colour palette#yellow and blue#goethe's theory of colour#parts 1 and 2#mfmm colur themes#jack robinson#phryne fisher

56 notes

·

View notes