#Mōri Shin

Text

hello, could I take a moment of your time to show off my age the first boy band I ever loved?

thx 🖤

#鎧伝サムライトルーパー#Yoroiden Samurai Torūpā#yoroiden samurai troopers#ronin warriors#Sanada Ryō#Ryo Sanada#Shū Rei Fuan#Kento Rei Fang#Mōri Shin#Cye Mouri#Hashiba Tōma#Rowen Hashiba#Date Seiji#Sage Date#真田 遼#秀 麗黄#毛利 伸#伊達征士#羽柴当麻#anime#80’s anime#90’s nostalgia#toonami#my childhood#ryo of the wildfire#kento of hardrock#cye of the torrent#rowen of the strata#sage of the halo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (53): (1587) Ninth Month, Twenty-sixth Day.

53) Ninth Month, Twenty-sixth day¹.

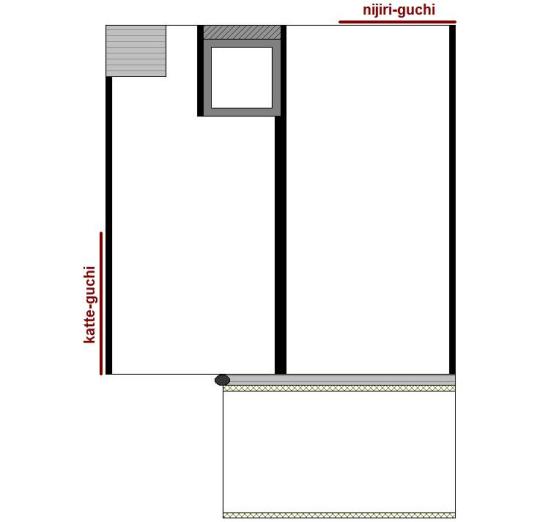

[◦ Two-mat room².]

◦ [Guests:] Terumoto [輝元]³, Sōmu [宗無]⁴, Sōun [宗雲]⁵.

Everything was the same as on the night of the Second⁶.

_________________________

¹Ku-gatsu nijū-roku nichi [九月廿六日].

The date was October 27, 1587, in the Gregorian calendar.

The time of day when this gathering took place is, oddly, not mentioned. However, because it is referenced in the subsequent two entries without comment (when a night gathering is being referred to, Rikyū seems to generally include that fact in his comments), morning or afternoon seems most likely.

²Though not mentioned, the room would have been the same one -- Rikyū’s two-mat room -- as on the Second, the gathering that the present chakai mirrors.

³Terumoto [輝元].

This was Mōri Terumoto [毛利輝元; 1553 ~ 1625], a daimyō-nobleman (as gon-chūnaigon [権中納言] he held the Third Rank); and who, eventually, served as a member of Hideyoshi’s Council of the Five Great Elders [go-tairō [五大老] as well).

While history has suggested that he was of below-average talent with regard to military matters, and so had little personal impact on the destiny of the nation*, he seems to have been an avid practitioner of chanoyu, and one of Rikyū's most cherished disciples†.

__________

*This negative assessment may have been enhanced as a result of the Tokugawa propaganda campaign against Terumoto (since he was nominally the general commander of the Seigun [西軍], which opposed Ieyasu's Tōgun [東軍] at the battle of Sekigahara -- though Mōri Terumoto was not personally present on the battlefield).

†The great disparity in their ages suggests that Rikyū harbored a paternal affection for the much younger Lord Terumoto.

⁴Sōmu [宗無].

This was the machi-shū Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu [住吉屋 宗無; 1534 ~ 1603*], who is also known as Yamaoka Hisanaga [山岡久永]. He was a wealthy townsman from Sakai, and also a highly respected chajin†, and served as one of Hideyoshi’s “Eight Masters of Tea” (sadō hachi-nin-shū [茶頭八人衆]). At other gatherings described in Rikyu's several kaiki that were attended by Konishi Yukinaga, Sōmu is also present, suggesting that he may have been one of Yukinaga's retainers, or perhaps a tea friend.

Interestingly, Sōmu was one of the guests at Rikyu's gathering on the second (which the present chakai replicates). Perhaps, being familiar with the utensils and arrangements, Sōmu was present primarily to assist Mōri Terumoto (who may still have been fairly inexperienced regarding the particulars of chanoyu).

___________

*Certain accounts suggest that Sōmu may have died in 1595, at the time when Sakai was razed on Hideyoshi’s orders (as a punishment for the city-state’s opposition to his invasion of Korea).

†Sōmu is said to have first studied chanoyu under Jōō, and then later with Rikyū (though, given his high standing with both Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, this latter assertion might be a revisionist opinion popularized by the Sen family during the Edo period; more likely, he was simply a member of the faction that eventually coalesced around Rikyū some years after Jōō's death).

Sumiyoshi-ya Hisanaga studied Zen under Shunoku Sōen [春屋宗園; ? ~ 1611], from whom he received the name Sōmu [宗無] -- which he used as his professional name later in life.

‡This gathering seems to have been the inspiration for the upcoming Kitano ō-cha-no-e [北野大茶の會].

⁵Sōun [宗雲].

Possibly* one of the senior monks of the Nanshū-ji -- though this person has, in fact, not been identified.

__________

*The name Sōun [宗雲] is known to have been used by several historical monks, though none of those identified lived during the sixteenth century -- which does not, of course, mean that there was no such person. Whomever he was, he seems not to have left any more mark on history than his mention in this kaiki.

⁶Banji futsu-ka dō-zen [萬事二日同前].

This means that the utensils, the arrangement of the room*, and the menu for the kaiseki, were the same as at the night gathering that Rikyu hosted on the Second†.

○ Shoza‡:

◦ Rikyū's Yoku-ryō-an hōgo [欲了庵法語];

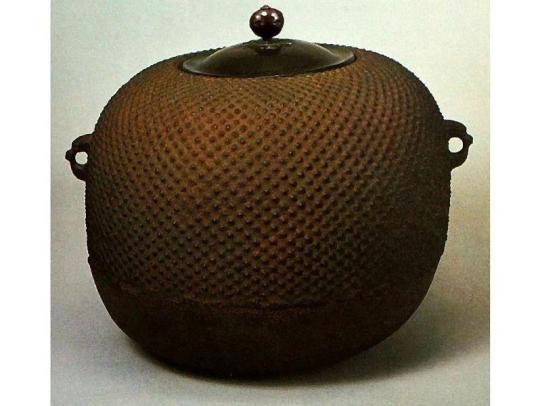

◦ the ko-arare uba-guchi kama [小霰姥口釜] (often referred to as the Hyakkai-gama [百會釜] due to its being known to Edo period practitioners primarily through its mention in that document).

◦ Rikyū's ruri-suzume kōgō [瑠璃雀香合] and a go-sun-hane [五寸羽] were arranged on the tsuri-dana.

○ Goza**:

◦ the kakemono remained hanging in the tokonoma, with the chabana†† (in Rikyū's prized Tsuru no hito-koe [鶴ノ一聲]‡‡ hanaire, shown below) arranged on the floor of the toko in front of it;

◦ Shōzan katatsuki chaire [松山肩衝茶入] on a maru-bon [丸盆]***;

◦ hikkiri [引切] (placed in association with the central kane)†††;

◦ the Soto-ga-hama ido chawan [外ヵ浜井戸茶碗];

◦ an ori-tame [折撓];

◦ Rikyū's Shigaraki mizusashi [信樂水指];

◦ mimi-guchi mizu-koboshi [耳口水飜].

The menu for the kaiseki apparently would have consisted of hoshi-na saku-saku-jiru [干菜サク〰汁] (miso-shiru containing coarsely chopped dried greens -- usually the leaves of the daikon [大根] and kabura [蕪], Japanese turnip), ume-katsuo [梅鰹] (mashed ume-boshi mixed with the katsuo-boshi and kombu -- the latter cut into small pieces -- left over from making the miso-shiru), yu-namasu [柚膾] (a sort of raw salad made from julienned daikon, carrot, and slivers of yuzu rind, dressed with a mixture of rice vinegar, soy sauce, and mirin); with fu-no-yaki [麩の焼] and grilled, salted shiitake [椎茸] as the kashi.

__________

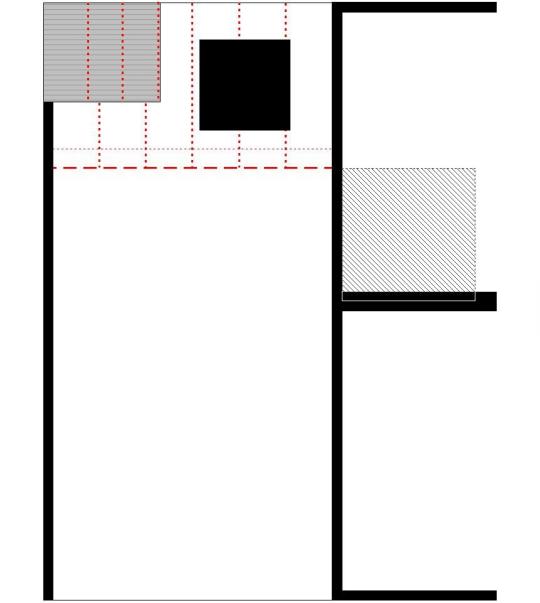

*In the chakai on which the present one is based, Rikyū tried a new arrangement by placing the futaoki in the middle of the mat. This derived from a practice associated with the old 1.5-mat room that had fallen into disuse along with that setting.

†In other words, the second day of the Ninth Month of Tenshō 15 (October 3, 1587). The post describing that gathering is entitled Nampō Roku, Book 2 (50): (1587) Ninth Month, Second Day, Night.

The URL URL for the post that details that chakai is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/184419990291/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-2-50-1587-ninth-month

‡With respect to the kane-wari: the toko held the kakemono, and so was han [半]; the room had the kama in the ro, and so was also han [半]; and the tana supported the kōgō and habōki, arranged side by side (with each contacting a different kane), and so was chō [調]: han + han + chō is chō.

**As for the kane-wari: the bokuseki remained hanging in the toko, with the chabana arranged on the floor of the toko in front of it, and so was chō [調]; the room had the kama in the ro, the mizusashi, with the chaire and chawan arranged in front of it, and the futaoki (with the hishaku resting on it) associated with the central kane, making the room han [半]; the tana was apparently empty, and so would be counted as chō [調]: chō + han + chō is han.

††Consisting, apparently, of a single chrysanthemum flower and its leaves.

‡‡This hanaire was also known as Tsuru no hashi [鶴ノ波子].

It was placed on top of a shin-nuri usu-ita (of the variety now known as the yahazu-ita [矢筈板]), which measured 1-shaku 3-sun 2-bu by 9-sun 2-bu.

***The chaire was arranged on a “maru-bon” [丸盆] – a round tray. Unfortunately, the tray that was paired with this chaire was destroyed in the (Edo) Great Fire of 1829, so its make and dimensions have been lost**.

For the sketch I assumed it was a Japanese-made tray, paired with this chaire by Rikyū (and so 2-sun larger than the chaire on all four sides) -- though a tray of the sort favored by Jōō (which would have been 3-sun larger on all four sides) would also have been possible, especially during the daytime (larger trays of this sort would make problems at night, since the tray would get in the way of the feet of the te-shoku [手燭] -- the long-handled candlestick used to provide light to the temae-za).

That said, in light of the tori-awase employed by Rikyū (specifically the large katatsuki-chaire coupled with a large ido-chawan), the size of the tray (whether based on Rikyū's preferences, or Jōō's) would have made displaying the chawan next to the bon-chaire impossible. Hence, the same kind of temae that Rikyū had been doing with the maru-tsubo chaire arranged on the (Jōō-sized) square ebony chaire-bon would have been used.

◎ This is something that is frequently ignored by the commentators: once Rikyū did something that was unusual, and he found a way to make it “work,” he often continues to use the same (or similar) arrangements, in order to habituate himself to the procedure. This is no different from what any experienced chajin would do today -- and serves to remind us that Rikyū was, indeed, an experienced chajin, rather than an all-knowing "tea god" as many make him out to be. He was as human as any of us, and his methods were exactly the same, too.

If for no other reason, the study of Rikyū's kaiki reveals to us the man behind the myth.

†††The futaoki was placed to the left of, and near the far end, of the mukō-ro, with the hishaku resting on top of it -- as seen in the sketch (above). These things were associated with the central kane (which means that the futaoki would have to rest on top of the kane, if only by a little); and the handle of the hishaku extending no farther forward than the front edge of the ro (again, as shown in the sketch), so it would not enter the yū-yo [有余].

———————————————————————————————————

The reader should understand that the above notes apply equally to the following two chakai (which essentially replicate this one) as well.

1 note

·

View note

Text

K-Pop Bands I Love (in no particular order) & My Biases

(a WIP list for my fandom master post; and for multiple biases, it's in a list from my top to least favorite)

TWICE

Chou Tzuyu

Hirai Momo

Yoo Jeongyeon

Im Nayeon

BLACKPINK

Lalisa Manoban / Lisa

Kim Jisoo

(G) I-DLE

Jeon Soyeon

Red Velvet

Kang Seulgi

Shon Seungwan / Wendy

GFRIEND / VIVIZ

Hwang Eunbi / SinB

OH MY GIRL

Yoo Siah / YooA

Kim Mihyun / Mimi

Hyun Seunghee

Choi Yewon / Arin

EVERGLOW

Park Jiwon / E:U

Heo Yoorim / Aisha

BTS

Kim Namjoon / RM

MOMOLAND

Lee Joowon / JooE

Lee Hyebin

Sung Jiyeon / Jane

MAMAMOO

Moon Byulyi / Moonbyul

Ahn Hyejin / Hwasa

Weeekly

Shin Jiyoon

TOMORROW × TOGETHER

Choi Yeonjun

WJSN

Lee Luda

Chu Sojung / EXY

Im Dayoung

Lee Jinsook / Yeoreum

Son Juyeon / Eunseo

Kim Hyunjung / SeolA

Stray Kids

Lee Felix

Hwang Hyunjin

Rocket Punch

Kim Sohee

Cherry Bullet

TBA

LE SSERAFIM

Kim Chaewon

Billlie

Fukutomi Tsuki

AOA

Park Choa / ChoA

T-ARA

Hahm Eunjung

Park Sunyoung / Hyomin

Park Soyeon

Jeon Boram

Lee Jihyun / Qri

Ryu Hwayoung

ITZY

Shin Ryujin

Choi Jisu / Lia

PURPLE KISS

Jang Eunseong / Dosie

Mōri Koyuki / Yuki

Lee Chaeyoung / Chaein

Cho Seoyoung / Ireh

Kep1er

Shen Xiaoting

Kim Dayeon

Huening Bahiyyih

Girls' Generation / SNSD

TBA

Girls in the Park / GWSN

TBA

Apink

TBA

STAYC

TBA

Monsta X

TBA

VIXX

TBA

I.O.I

TBA

Seventeen

TBA

TeenageGirls / CLASS:y

TBA

#master post#kpop bias master post#kpop bias#kpop biases#k-pop#k-pop bias#k-pop biases#k-pop bias master post#k-pop master post#my bias#my biases#my kpop biases#my kpop bias#my k-pop bias#my k-pop biases

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hideyoshi’s death - Sekigahara - chronology

This has been in my drafts for a long time and it’s a bit incomplete towards the end, but... I’m not sure if I’ll be able to answer any additional questions, these are facts (plus some rumours from secondary sources), it’s up to you to interpret them as you like.

1598

18. 8. Toyotomi Hideyoshi died | (Ishida Mitsunari informed Ieyasu that Hideyoshi died) | Tokugawa Hidetada returned to Edo

(Hideyoshi is still considered alive

some form of tension between Ieyasu and go-bugyō was apparent)

25. 8. go-bugyō issued a letter about peace with Korea

28. 8. an order to withdraw from Korea was issued by go-tairō (without Uesugi Kagekatsu’s signature) informing that Mōri Hidemoto, Asano Nagamasa and Ishida Mitsunari were being sent to Hakata to deal with it | Mōri Terumoto made an oath with Mashita Nagamori, Ishida Mitsunari, Maeda Gen’i and Natsuka Masaie about cooperation

(Ukita Hideie was often visiting Terumoto’s mansion making friends with him)

3. 9. go-tairō and go-bugyō exchanged an oath that was forbidding them from making groups of supporters from outside the ten of them and that they will protect Hideyori

5. 9. another letter about peace with Korea is issued by 4-tairō

(Ieyasu, Terumoto and Hideie were supposed to go to Hakata, but that didn’t happened)

end of the ninth month - Ishida Mitsunari, Asano Nagamasa, Mōri Hidemoto were sent to Hakata to withdraw forces from Korea.

tenth month - Uesugi Kagekatsu arrived to Fushimi from Aizu

25. 11. Ieyasu invited Mashita Nagamori to his mansion in Fushimi

26. 11. Ieyasu invited Chōsokabe Morichika to his mansion in Fushimi

3. 12. Ieyasu invited Shinjō Naoyori to his mansion in Fushimi

6. 12. Ieyasu invited Shimazu Yoshihisa to his mansion in Fushimi

7. 12. Ieyasu invited Hosokawa Tadaoki to his mansion in Fushimi

(Katō Kiyomasa, Kuroda Nagamasa returned from Korea; sometime during the 12th month, before Shimazu and Konishi; 23. 11. they departed from Korea)

10. 12. Shimazu’s forces (Yoshihiro, Tadatsune) entered Hakata

11. 12. Konishi Yukinaga and Terazawa Hirotaka (Masanari)’s forces entered Hakata

(friction between Mitsunari, Yukinaga etc. and Kiyomasa, Asanos, Kurodas)

24. 12. Mitsunari returned to Osaka together with Shimazu Tadatsune

(everyone who returned from Korea went to Osaka)

1599

10. 1. Toyotomi Hideyori moved from Fushimi castle to Osaka castle. accompanied by go-tairō and go-bugyō (it was probably a nice show). Toshiie, following Hideyoshi’s will, stayed in Osaka as Hideyori’s guardian from then on.

(Kagekatsu returned back to Fushimi)

12. 1. Ieyasu returned back to Fushimi.

(a tentative decision to return Kobayakawa Hideaki his old fiefs was made)

(Ieyasu’s marriage arrangements with Date Masamune, Fukushima Masanori, Hachisuka Ieamasa became a problem)

18. 1. go-bugyō wrote to Date Masamune that use of guns was limited in Osaka

19. 1. 4-tairō and go-bugyō sent messengers to Ieyasu that he was going against Hideyoshi’s will

(some tension appeared, some daimyō gathered at Ieyasu’s mansion)

20. 1. all was settled without an armed conflict | several generals gathered at Mōri Terumoto’s mansion in Fushimi for discussion

24. 1. 4-tairō condemned Ieyasu for going against Hideyoshi’s will

28. 1. Ieyasu went to Osaka

29. 1. Ieyasu’s vassal Sakakibara Yasumasa entered Fushimi with an army | Ieyasu was back in Fushimi

2. 2. accompanying the official announcement of Hideyoshi’s death, the go-bugyō shaved their heads

5. 2. Hideaki’s fiefs were officially returned by go-tairō

12. 2. Ieyasu exchanged an oath with 4-tairō and go-bugyō (at least on the outside it looked like Ieyasu was the one making compromise) concerning the marriage problem

(Shimazu Yoshihisa returned from Fushimi to Kyushu; 14. 3. arrived to Satsuma)

29. 2. Toshiie visited Ieyasu in Fushimi

(reconciliation between Ieyasu and Maeda Toshinaga and Ieyasu and Ukita Hideie were made before 8. 3.)

9. 3. Shimazu Tadatsune killed Ijūin Tadamune

11. 3. Ieyasu visited sick Toshiie in Osaka

3. 3. (leap year) Maeda Toshiie died

4. 3. (leap year) Ishida Mitsunari was attacked in Osaka by Katō Kiyomasa, Fukushima Masanori, Kuroda Nagamasa, Tōdō Takatora, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Asano Yukinaga and Hachisuka Iemasa and escaped to his own wing in Fushimi castle.

5. 3. (leap year) Ieyasu wrote a letter to Katō Kiyomasa, Fukushima Masanori, Kuroda Nagamasa, Tōdō Takatora, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Asano Yukinaga and Hachisuka Iemasa

8. 3. (leap year) Kita no Mandokoro (Nene) tried to mediate (either on this day or earlier)

(Mōri Terumoto and Uesugi Kagekatsu were in Fushimi at this time. Ukita Hideie was probably in Osaka being sad his father-in-law died; he could assist Mitsunari in escaping though; Satake Yoshinobu could accompany Mitsunari from Osaka to Fushimi.

Go-bugyō were also in Fushimi (maybe except for Asano, who knows). 7 generals were asking for Mitsunari’s retirement. There were also voices for Mashita Nagamori’s retirement.

Osaka was full of people loyal to Ieyasu, so anti-Ieyasu forces wouldn’t be able to enter or exit.

Mitsunari sent Konishi Yukinaga and Terazawa Hirotaka (Masanari) to Mōri Terumoto as messangers.

Mitsunari would like to attack the enemy side with Terumoto’s help, but Ōtani Yoshitsugu didn’t think it would be a good idea,

Terumoto and Uesugi Kagekatsu tried to mediate. Kagekatsu and Ieyasu talked about marriage between their two clans, but it didn’t went through)

9. 3. (leap year) Ieyasu made his final decision and the disturbance more or less ended.

(Mitsunari’s son Hayato no kami (probably Shigeie) started to serve Hideyori. He might have also become the Ishida clan family head)

10. 3. (leap year) Mitsunari left Fushimi to be confined in Sawayama. Yūki Hideyasu was sent as his escort.

13. 3. (leap year) Ieyasu entered Fushimi castle’s Nishi no maru

19. 3. (leap year) Kuroda Nagamasa and Hachisuka Iemasa’s honour was restored.

21. 3. (leap year) Mōri Terumoto and Tokugawa Ieyasu exchanged an oath letter calling each other brothers

fourth month - Konishi Yukinaga, Tachibana Muneshige, Terazawa Hirotaka returned to Kyushu accompanying Shimazu Tadatsune, who was pardoned by 3-bugyō

(a strife between Shimazu clan and Ijūin clan, their retainers)

seventh month - more daimyō who returned from Korea were allowed to return back to their provinces

eighth month - Uesugi Kagekatsu and Naoe Kanetsugu returned to Aizu | Maeda Toshinaga returned to Kaga

18. 8. Ieyasu participated in Hideyoshi’s death anniversary ceremony at Hōkoku shrine

7. 9. Ieyasu left Fushimi castle and went to Osaka. He stayed in Ishida Mitsunari’s mansion (Ieyasu didn’t have his own mansion in Osaka)

(Terumoto’s son, age 4, went through genpuku at Osaka, got Hideyori’s “hide” and was named Hidenari)

(Ieyasu offered a congratulatory speech to Hideyori 9. 9. ?)

(rumours about a planned assassination on Ieyasu appeared sometime during this period)

13. 9. Ieyasu moved to Ishida Masazumi’s mansion (Masazumi went to Sakai)

26. 9. Kita no Mandokoro left Osaka castle’s Nishi no maru and went to live in Kyoto’s Shin (New) castle

27. 9. Ieyasu started to live in Osaka castle’s Nishi no maru

(Ōtani Yoshitsugu’s adopted son Daigakusuke (Yoshiharu) and 1 000 men sent by Ishida Mitsunari following Ieyasu’s orders blocked a way to the capital from Echizen, so Maeda Toshinaga wouldn’t be able to proceed to the capital. At the same time Katō Kiyomasa’s route to the capital was also blocked.)

tenth month - subjugation of Kaga | Asano Nagamasa lost his bugyō position and was confined in Kai | Hijikata Katsuhisa and Ōno Harunaga were also punished | Hosokawa Tadaoki, related by marriage to Maeda clan, who tried to apologize for Toshinaga, sent his son Tadatoshi to Edo as a hostage

eleventh month - Maeda Toshinaga sent his mother to Edo as a hostage

1600

first month - a rebellion in the Ukita clan occurred - Togawa Michiyasu and others (mostly important Ukita vassals) VS Nakamura Jirōbee and Hideie. Ōtani Yoshitsugu and Sakakibara Yasumasa (one of Ieyasu’s Shitennō = “Four Guardian Kings”) acted as mediators (there are many stories, though, one of them goes that Ieyasu got angry with Yasumasa for sticking his nose into other clan’s business and sent him home, so Yoshitsugu also pulled himself out.)

second month - Shimazu internal strife ended with Ijūin Tadazane’s capitulation (Ieyasu sent his vassal to act as mediator)

(Ieyasu gets reports that Kagekatsu plans a rebellion)

(Kagekatsu is asked to pay homage in the capital, but he refused. Mashita Nagamori and Ōtani Yoshitsugu were acting as mediators.)

14. 4. Naoe Kanetsugu’s letter

(the rebellion in Ukita clan was settled by Ieyasu’s intervention. Togawa Michiyasu (the one who started it) and some others became Ieyasu’s vassals. Ukita clan’s power was seriously weakened.)

(At the end of fifth month, the subjugation of Uesugi was decided. The 3-bugyō were kind of against it, because Ieyasu would be “abandoning Hideyori in Osaka” but what could they do)

(After the rebellion was settled, Hideie was staying in Fushimi)

8. 6. - 11. 6. Hideie was back in his fief (what he did after that isn’t known, it’s assumed he went back to Kamigata since Terumoto was gone and Ieyasu would soon be gone. He most likely sent Ukita Akiie (Sakazaki Naomori) to Aizu as his stand-in)

8. ~ 10. 6. Terumoto departed from Osaka to return back to Hiroshima

14. 6. Terumoto ordered Ankokuji and Hiroie to depart to Aizu | Mōri Motonari’s 33rd death anniversary, which Terumoto carried out, was held at Tōshun-ji temple (today’s Yamaguchi prefecture)

15. 6. 3-bugyō gave an order to subjugate Aizu instructing the generals to follow Ieyasu’s orders

16. 6. Ieyasu departed to subjugate Aizu. He left Osaka and entered Fushimi.

17. 6. Terumoto visited Itsukushima Shrine and in the evening/night arrived to Hiroshima castle

18. 6. Ieyasu left Fushimi and departed for Edo.

2. 7. Ieyasu entered Edo | {traditionally it’s said that on this day Mitsunari and Yoshitsugu met at Sawayama, but there are many versions as to why}

4. 7. Ankokuji Ekei left Izumo

5. 7. Kikkawa Hiroie left Izumo | Ukita Hideie visited Hōkoku shrine (shrine enshrining Hideyoshi, there are theories he did that to prepare for “raising the army”)

(on his way to Aizu Ōtani Yoshitsugu stopped at Tarui in Minō (some 30 km away from Sawayama castle) because of his illness - it comes from a secondary source)

11. 7. traditionally, this is the day when Yoshitsugu and Mitsunari rose their armies together.

(around this time Ankokuji met with Ishida Mitsunari and Ōtani Yoshitsugu at Sawayama)

12. 7. Mashita Nagamori, Natsuka Masaie, Maeda Gen’i wrote to Terumoto to come back to Osaka (Terumoto got it on the 15th) | some of those who left to Aizu returned to Kamigata | some sort of disturbance was occurring in Fushimi and Osaka | rumours about Mitsunari’s possible departure for the front reached Kamigata

(from this day onward various people were writing to Ieyasu’s side about Mitsunari and Yoshitsugu’s suspicious movements. 3-bugyō, Hiroie and Yodo-dono included)

13. 7. Ankokuji Ekei and Kikkawa Hiroie arrived to Osaka | Hiroie learned about Mitsunari and Yoshitsugu’s plan

14. 7. a messenger from Ankokuji Ekei arrived to Hiroshima asking Terumoto to come to Osaka

15. 7. Terumoto departed from Hiroshima | Terumoto wrote to Katō Kiyomasa to go to Osaka | Ieyasu’s forces holed up in Fushimi castle | some forces that departed to Aizu returned back from Ōmi | Shimazu Yoshihiro sent a letter to Uesugi Kagekatsu telling him that Mōri Terumoto, Ukita Hideie, magistrates, Konishi Yukinaga, Ōtani Yoshitsugu, Ishida Mitsunari and himself decided to join his side

17. 7. Mashita Nagamori, Natsuka Masaie, Maeda Gen’i issued 13 charges against Ieyasu | Terumoto entered Osaka | Hosokawa Gracia died

18. 7. the siege of Fushimi castle started | Ieyasu’s forces in Fushimi burned down bugyo’s mansions (or wings in the castle) | Ishida Mitsunari visited Hōkoku shrine in Kyoto

19. 7. Tokugawa Hidetada’s forces left Edo to go to Aizu

21. 7. Ieyasu’s forces left Edo to go to Aizu

24. ~ 25. 7. meeting at Oyama. Ieyasu stayed at Oyama until the beginning of the eight month.

29. 7. Mitsunari left Sawayama and participated in the siege of Fushimi

30. 7. Mitsunari entered Osaka castle.

1. 8. Fushimi castle fell | the Toyotomi generals (Fukushima, Tōdō, Ikeda, Kuroda) went west followed by Honda Tadakatsu and Ii Naomasa

5. 8. Mitsunari left Osaka and returned to Sawayama | Ieyasu returned to Edo and stayed there almost a month

9. 8. Mitsunari left Sawayama and went to Tarui in Minō.

10. 8. Mitsunari entered Ōgaki castle

23. 8. Gifu castle fell

1. 9. Ieyasu left Edo and aimed back to Kinai

7. 9. siege of Ōtsu castle started

14. 9. Ieyasu arrived to Akasaka | Mitsunari, Konishi Yukinaga, Ukita Hideie, Shimazu Yoshihiro moved from Ōgaki castle to Sekigahara/Yamanaka (or wherever the battle took place) | Fukushima Masanori and other Toyotomi generals followed

15. 9. Sekigahara | Ōtsu castle capitulated

18. 9. Sawayama castle fell

23. 9. a peace between Ieyasu and Terumoto | Ōgaki castle capitulated

25. 9. Terumoto left Osaka castle’s Nishi no maru and moved to his mansion in Settsu province where he retired (in the third part of the 10th month, he gave the clan headship to his young son Hidenari (age 5), shaved his head and took a new name Sōzui)

27. 9. Ieyasu entered Osaka castle’s Nishi no maru

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tekken: Blood Vengeance

Directed by Yōichi Mōri

Produced by Yoshinari Mizushima

Written by Dai Satō

The plot, which takes place in an alternate storyline[4] between the events of Tekken 5 and Tekken 6, begins with Anna Williams setting up a decoy for her sister, Nina Williams, who is currently working with the new head of the Mishima Zaibatsu, Jin Kazama. Anna, on the other hand, works for Jin's father, Kazuya Mishima and its rival organization, G Corporation. Both are seeking information about a student named Shin Kamiya, and Anna dispatches a Chinese student, Ling Xiaoyu to act as a spy, while Jin sends humanoid robot Alisa Bosconovitch for a similar purpose. Wiki

2 notes

·

View notes

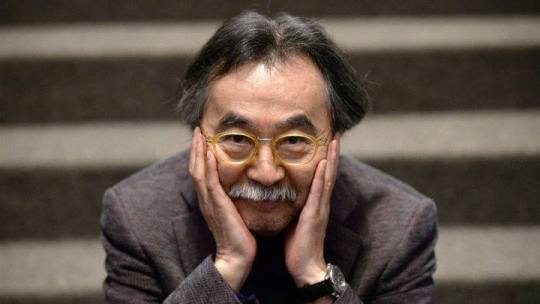

Photo

Jirô Taniguchi nous a quitté...., vu sur Akihabara no Sasayaki http://ift.tt/2lcI73t Jirô Taniguchi # Bloc TechniqueNom japonais : 谷口 ジローDate de naissance : 14 août 1947Lieu de naissance : Tottori (préfecture de Tottori)Date de décès : 11 février 2017 (à 69 ans) (à Tokyo)Editeurs associés : Shōgakukan, Futabasha, Kōdansha, Akita ShotenMaître : Kyūta Ishikawa # Biographie Jirō Taniguchi naît le 14 août 1947 à Tottori au Japon, d'une famille « endettée, assez pauvre » : son père est coiffeur, sa mère femme de ménage et employée de pachinko. Enfant à la santé fragile, il passe beaucoup de temps à lire et à dessiner. Lecteur dans sa jeunesse de mangas shōnen, il s'intéresse au seinen et au gekiga à partir de la fin des années 1960 sous l'influence de Yoshihiro Tatsumi et du magazine Garo. Il décide de devenir mangaka en 1969, et monte alors à Tokyo où il devient l'assistant de Kyūta Ishikawa, pendant cinq ans. Il publie sa première bande dessinée en 1970 : Kareta heya, répond à quelques commandes de mangas érotiques, puis devient assistant de Kazuo Kamimura. C'est à cette époque qu'il découvre la bande dessinée européenne, alors inconnue au Japon, et dont le style (netteté et diversité du dessin), notamment celui de la ligne claire, va fortement l'influencer. Il finit par prendre son indépendance et s'associe dans les années 1980 avec les scénaristes Natsuo Sekikawa (également journaliste) et Caribu Marley, avec lesquels il publiera des mangas aux styles variés : aventures, policier, mais surtout un manga historique, Au temps de Botchan, sur la littérature et la politique dans le Japon de l'ère Meiji. C'est à cette époque qu'il décide de limiter ses sorties éditoriales, bien qu'il travaille toujours « huit à neuf heures par jour ». À partir des années 1990, il se focalise sur les choses de la vie quotidienne, et sur les relations entre êtres humains, mais aussi entre les hommes et les animaux, avec L'Homme qui marche et Terre de rêves. Suivront L'Orme du Caucase, Le Journal de mon père et Quartier lointain, édités en France dans la collection Écritures de l'éditeur Casterman. Autour du thème de la relation entre l'homme et la nature, il s'attache particulièrement à l'alpinisme, avec K, Le Sauveteur, Le Sommet des dieux et avec la nouvelle La Terre de la promesse (dans le recueil Terre de rêves). Reconnu en France, le grand public japonais le découvre en 2012 avec à l'adaptation en série télé du Gourmet solitaire. Son atelier se trouve dans le quartier de Kumegawa (久米川) de la ville de Higashimurayama (banlieue ouest de Tokyo). Jirō Taniguchi s'éteint le 11 février 2017 à l'âge de 69 ans, à Tokyo, des suites d'une longue maladie. Il venait de terminer le premier volume d'une nouvelle œuvre qui aurait dû en compter trois, La Forêt millénaire. # Regards sur l'œuvre À ses débuts, Jirō Taniguchi s'inspire avec Natsuo Sekikawa du roman noir américain, avec pour objectif d'en faire une version BD humoristique, sans grand succès11. Il est également influencé par les romans animaliers, notamment ceux d'Ernest Thompson Seton dont il s'inspire pour Blanca (du nom d'un des chiens de Lobo the King of Currumpaw), et à qui il rendra hommage dans Seton. Ses histoires plus récentes traitent de thèmes universels comme la beauté de la nature, l'attachement à la famille ou le retour en enfance. Il s'inspire d'ailleurs de sa vie personnelle : souvenirs de son enfance à Tottori dans Le Journal de mon père et Quartier lointain, débuts de mangaka à Tokyo dans Un zoo en hiver, ou relations avec ses animaux domestiques dans Terre de rêves. La place de l'animal et de la nature dans l'existence des hommes est une question qui est au centre de sa création. De plus, d'après lui il est « l'un des rares auteurs de manga à dessiner des animaux, ce qui m'incite à pousser ma réflexion et mon travail sur le sujet ». Sur son attrait pour les choses du quotidien, Jirō Taniguchi déclare : « Si j'ai envie de raconter des petits riens de la vie quotidienne, c'est parce que j'attache de l'importance à l'expression des balancements, des incertitudes que les gens vivent au quotidien, de leurs sentiments profonds dans les relations avec les autres. [...] Dans la vie quotidienne, on ne voit pas souvent des gens hurler ou pleurer en se roulant par terre. Si mes mangas ont quelque chose d'asiatique, c'est peut-être parce que je m'attache à rendre au plus près la réalité quotidienne des sentiments des personnages. Si on y pénètre en profondeur, une histoire peut apparaître même dans les plus petits et les plus banals événements du quotidien. C'est à partir de ces moments infimes que je crée mes mangas. » Son dessin, bien que caractéristique du manga, est cependant accessible aux lecteurs qui ne connaissent que la bande dessinée occidentale. Taniguchi dit d'ailleurs trouver peu d'inspiration parmi les auteurs japonais, et est plus influencé par des auteurs européens, tels Jean Giraud, avec qui il a publié Icare, ou François Schuiten, proche comme lui de La Nouvelle Manga, mouvement initié par Frédéric Boilet, le promoteur du manga d'auteur en France. Il finit ainsi par sortir en France, en 2007, un titre sous le format de bande dessinée, La Montagne Magique, prépublié au Japon en décembre 2005 au format classique, puis une série de quatre tomes intitulée Mon Année à partir de novembre 2009, en collaboration avec le scénariste Jean-David Morvan, en attente de prépublication au Japon. Jirō Taniguchi se dit également influencé par le cinéaste Yasujirō Ozu, chez qui on retrouve le même rythme et la même simplicité : « C'est une influence directe. J'ai été marqué par Voyage à Tokyo et Printemps tardif. Je les ai vus enfant, mais sans en apprécier toute la portée. Je m'y suis vraiment intéressé quand j'avais 30 ans. J'aime l'universalité et l'intemporalité de ses histoires et la simplicité efficace avec laquelle il les raconte. Aujourd'hui, j'y pense à chaque fois que je dessine un manga. » Outre Voyage à Tokyo, ses films préférés sont Barberousse d'Akira Kurosawa et Le Retour d'Andreï Zviaguintsev. Et pour lui, Osamu Tezuka, Utagawa Hiroshige, Edward Hopper, Vincent van Gogh et Gustav Klimt sont les cinq plus grands dessinateurs de l'Histoire. # Œuvres Années 1970 : Kareta heya (嗄れた部屋, littéralement « Une chambre rauque »), 1970 Lindo! (リンド!), 1978, 4 volumes, réédité en 2004 en 1 volume, scénario de Natsuo Sekikawa Mubōbi toshi (無防備都市, litt. « Une ville sans défense »), 1978, 2 volumes, scénario de Natsuo Sekikawa Années 1980 : Trouble Is My Business (事件屋稼業, Jiken-ya kagyō), 1980 (Kana, 2013-2014), scénario de Natsuo Sekikawa Ōinaru Yasei (大いなる野生, litt. « Les Grandes Régions Sauvages »), 1980, recueil de 7 nouvelles, augmenté à 10 lors de sa réédition en 1985 Ao no senshi (青の戦士, litt. « Le Soldat en bleu »), 1980-1981, scénario de Caribu Marley Hunting Dog (ハンティングドッグ), 1980-1982, 2 volumes Live! Odyssey (LIVE!オデッセイ, Live ! Odessei), 1981, 3 volumes, 2 lors de ses rééditions en 1987 et 1998, scénario de Caribu Marley Knuckle Wars (ナックルウォーズ), 1982-1983, 3 volumes, 2 lors de sa réédition en 1988, scénario de Caribu Marley Shin-jiken-ya kagyō (新・事件屋稼業), 1982-1994, 4 volumes, 5 lors de sa réédition de 1994, 6 lors de celle de 1996, scénario de Natsuo Sekikawa Seifū ha shiroi (西風は白い, litt. « Le Vent d'ouest est blanc »), 1984, recueil de 8 nouvelles, scénario de Natsuo Sekikawa Rude Boy (ルードボーイ, Rūdo bōi), 1984-1985, collaboration avec Caribu Marley Blanco (ブランカ, Buranka), 1984-1986 (Casterman sous le titre Le Chien Blanco, 1996, puis volumes 1 et 2, 2009), 2 volumes Enemigo, 1985 (Casterman, 2012), scénario de M.A.T. Tokyo Killers (海景酒店 Hotel Harbour View, Kaikei shuten Hotel Harbour View), 1986 (Kana, 2016), scénario de Natsuo Sekikawa K (ケイ), 1986 (Kana, 2006), scénario de Shirō Tōzaki Au temps de Botchan (ぼっちゃんの時代, Botchan no jidai), 1987-1996 (Le Seuil, 2002-2006, Casterman, 2011-2013), scénario de Natsuo Sekikawa, fresque en cinq volumes évoquant l'ère Meiji et ses écrivains Ice Age Chronicle of the Earth (地球氷解事紀, Chikyū hyōkai-ji-ki), 1987-1988 (Casterman, 2015), 2 volumes Encyclopédie des animaux de la préhistoire (原獣事典, Genjū jiten), 1987-1990 (Kana, 2006), one shot Garôden (餓狼伝, Garōden), 1989-1990 (Casterman, 2011), scénario de Baku Yumemakura, one shot Années 1990 : Samurai non grata (サムライ・ノングラータ, Samurai-nongurāta), 1990-1991, scénario de Toshihiko Yahagi L'Homme qui marche (歩くひと, Aruku hito), 1990-1991 (Casterman, 1995), one shot Benkei in N.Y., 1991-1995, scénario de Jinpachi Mōri Kaze no shô, le livre du vent (風の抄, Kaze no shō), 1992 (Panini Comics, 2004), one shot, scénario de Kan Furuyama Terre de rêves (犬を飼う, Inu o kau, litt. « Élever un chien »), 1991-1992 (Casterman, 2005), recueil de cinq nouvelles L'Orme du Caucase (人びとシリーズ「けやきのき」, Hitobito Shirīzu : Keyaki no ki, litt. « Série sur les humains : Le Zelkova du Japon »), 1993 (Casterman, 2004), recueil de 8 nouvelles, scénario de Ryūichirō Utsumi Mori e (森へ, litt. « vers la forêt »), 1994 Le Journal de mon père (父の暦, Chichi no koyomi), 1994 (Casterman, 1999-2000, 3 vol., puis 2004, 1 vol.), one shot Le Gourmet solitaire (孤独のグルメ, Kodoku no gurume), 1994-1996 (Casterman, 2005), one shot, scénario de Masayuki Kusumi Blanco (神の犬 ブランカII, Kami no inu Buranka II, litt. « Le Chien divin, Blanca II »), 1995-1996 (Casterman, volumes 3 et 4, 2010), 2 volumes Icare (イカル, Ikaru), 1997 (Kana, 2005), one shot, scénario de Mœbius Quartier lointain (遥かな町へ, Haruka-na machi e), 1998 (Casterman, 2002-2003, 2 vol.), 2 volumes Tōkyō genshi-kō (東京幻視行), 1999 Le Sauveteur (捜索者, Sōsakusha, litt. « L'enquêteur »), 1999 (Casterman, 2007), one shot Années 2000 : Le Sommet des dieux (神々の山嶺, Kamigami no Itadaki), 2000-2003 (Kana, 2004-2005), 5 volumes, scénario de Baku Yumemakura Sky Hawk (天の鷹, Ten no taka, litt. « Le Faucon du ciel »), 2001-2002 (Casterman, 2002) Le Promeneur (散歩もの, Sampo mono), 2003-2005 (Casterman, 2008), scénario de Masayuki Kusumi L'Homme de la toundra (凍土の旅人, Tōdo no tabibito), 2004 (Casterman, 2006), recueil de 6 nouvelles Un ciel radieux (晴れゆく空, Hareyuku sora), 2004 (Casterman, 2006), one shot Seton (シートン, Shīton), 2004-2006 (Kana, 2005-2008), 4 volumes indépendants parus, scénario de Yoshiharu Imaizuma sur Ernest Thompson Seton La Montagne magique (魔法の山, Mahō no yama), prépublié en 2005 (Casterman, 2007), one shot Les Années douces (センセイの鞄, Sensei no kaban, litt. « Le Sac du professeur »), 2008 (Casterman, 2010-2011), 2 volumes, d'après le roman de Hiromi Kawakami Un zoo en hiver (冬の動物園, Fuyu no dōbutsuen), 2008 (Casterman coll. « Écritures », 2009), one shot Mon année, 2009, 1 volume sur 4, scénario de Jean-David Morvan Jirô Taniguchi, une anthologie (谷口ジロー選集, Taniguchi Jirō Senshū, litt. « Sélection/anthologie de Jirō Taniguchi ») : Inu o kau to 12 no tanpen (犬を飼うと12の短編, litt. « Élever un chien et 12 histoires courtes »), 2009 (Casterman, 2010), one shot regroupant les recueils Inu o kau (Terre de rêves) et Tōdo no tabibito (L'Homme de la toundra), ainsi que deux nouvelles inédites : La Lune finissante (秘剣残月, Hiken zangetsu) et Une lignée centenaire (百年の系譜, Hyakunen no keifu) Années 2010 : Nazuke enumono (名づけえぬもの), 2010 Furari (ふらり。, Furari.), 2011 (Casterman, 2012), one shot inspiré de la vie de Tadataka Inō Les Enquêtes du limier (猟犬探偵, Ryōken tantei), 2011-2012 (Casterman, 2013), 2 volumes, d'après le roman St Mary no ribbon (セント・メリーのリボン, Sento Merī no ribon) d’Itsura Inami Les Contrées sauvages (荒野より, Kōya yori), 2012 (Casterman, 2014, 2 volumes), recueil de nouvelles reprenant notamment Nazuke enumono Les Gardiens du Louvre (千年の翼、百年の夢, Chitose no tsubasa, hyaku nen no yume, litt. « Ailes de mille ans, rêve de cent ans »), 2014 (Louvre éditions/Futuropolis, 2014), one shot Elle s'appelait Tomoji (とも路, Tomoji), 2014 (Rue de Sèvres, 2015), one shot, avec Miwako Ogihara Rêveries d'un gourmet solitaire (孤独のグルメ2, Kodoku no gurume 2), 2014 (Casterman, 2016), one shot, scénario de Masayuki Kusumi Œuvres collaboratives Frédéric Boilet, Tōkyō ha boku no niwa (東京は僕の庭), 1997 (Tokyo est mon jardin, 1998). Jirō Taniguchi n'a réalisé que les trames de cet album. Natsu no sora (夏の空, litt. « Le Ciel d'été »), nouvelle de douze pages dans le recueil Japon, 2005, dirigé par Frédéric Boilet, avec Moyoko Anno, Aurélia Aurita, Frédéric Boilet, Nicolas de Crécy, Étienne Davodeau, Little Fish, Emmanuel Guibert, Kazuichi Hanawa, Daisuke Igarashi (en), Taiyō Matsumoto, Fabrice Neaud, Benoît Peeters, David Prudhomme, François Schuiten, Joann Sfar et Kan Takahama. L'Homme qui dessine, 2012, entretiens avec Benoît Peeters. Artbook L'Art de Jirô Taniguchi (谷口ジロー画集, Taniguchi Jirō gashū), 2016 (Casterman, 2016) # Distinctions 1992 : Prix du manga Shōgakukan, catégorie Prix spécial du jury pour Terre de rêves1993 : Prix de l'association des mangaka japonais, catégorie Prix d'excellence pour Au temps de Botchan1998 : Prix culturel Osamu Tezuka, catégorie Grand Prix pour Au temps de Botchan Prix d'Excellence du Festival des arts médias de l'Agence pour les affaires culturelles au Japon, catégorie Manga pour Quartier lointain2001 : Prix d'Excellence du Festival des arts médias de l'Agence pour les affaires culturelles au Japon, catégorie Manga pour Le Sommet des dieux - Italie Prix Micheluzzi de la meilleure bande dessinée pour Quartier lointain - France Prix du jury œcuménique de la bande dessinée pour Le Journal de mon père2002 : Espagne Prix Haxtur de la meilleure histoire longue pour Le Journal de mon père2003 : - France Alph-Art du meilleur scénario au Festival d'Angoulême 2003 pour le tome 1 de Quartier lointain - France Prix des libraires de bande dessinée Canal BD au Festival d'Angoulême 2003 pour Quartier lointain2004 : Italie Prix Micheluzzi de la meilleure série étrangère pour Au temps de Botchan (Natsuo Sekikawa)2005 : - France Prix du dessin du Festival d'Angoulême 2005 pour le tome 2 du Sommet des dieux - Espagne Prix Haxtur de la meilleure histoire courte pour L'Orme du Caucase (avec Ryūichirō Utsumi)2007 : Espagne Prix Haxtur de la meilleure histoire longue pour Seton t. 1 (avec Yoshiharu Imaizumi)2008 : - Espagne Prix Haxtur du meilleur dessin pour Seton t. 3 - Allemagne Prix Max et Moritz de la meilleure publication de bande dessinée japonaise pour Quartier lointain2011 : France Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Décoration remise par Frédéric Mitterrand à Tokyo le 15 juillet 201123,24.2015 : Norvège Prix Sproing de la meilleure bande dessinée étrangère pour Le Journal de mon père # Adaptations 2010 : Quartier lointain, film de Sam Garbarski, avec Jonathan Zaccaï, Léo Legrand, Alexandra Maria Lara et Pascal Greggory, sur une musique composée par Air. L'action se déroule en France, à Nantua, le héros s'appelant Thomas. Jirō Taniguchi fait une apparition dans le film.2011 : adaptation de Quartier lointain au théâtre par Dorian Rossel.2012 : adaptation du Gourmet solitaire en drama avec Yutaka Matsushige sur TV Tokyo.2015 : annonce de la préparation d'un film d'animation français en 3D tiré du Sommet des dieux et réalisé par Jean-Christophe Roger et Eric Valli.2016 : tournage de l'adaptation d’Un ciel radieux par Nicolas Boukhrief et Frédérique Moreau avec Léo Legrand, Dimitri Storoge et Marie Kremer. Source : wikipedia Tags : #personnalité #Jirô-Taniguchi #Taniguchi-Jirô http://ift.tt/2lHMz70

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (30): (1587) Fourth Month, First Day, Morning.

30) Fourth Month, First Day; Morning¹.

◦ Three-mat room².

◦ [Guests:] Kobayakawa Takakage [小早川隆景]³, Yoshikawa Kurando [吉川蔵人]⁴.

Sho [初]⁵.

﹆ The ahiru-kago [アヒル籠] was hung up [in the toko]⁶, [in which were arranged sprays of] unohana [卯花]⁷.

◦ On a ko-ita [小板], the furo [風爐]⁸.

◦ Kama unryū [釜 雲龍]⁹.

◦ On the tana: kōgō [香合] ・ habōki [羽帚]¹⁰.

▵ Shiru imo-gara ・ sasage [汁 イモカラ ・ サヽケ]¹¹.

▵ Uzura senba-iri [鶉 センハイリ]¹².

▵ Kuro-me [黒メ]¹³.

▵ Ae-mono [アヘモノ]¹⁴.

▵ Iri-kaya ・ kawa-take [イリカヤ ・ 川茸]¹⁵.

Go [後]¹⁶.

﹆ Yoku-ryō-an [欲了庵]¹⁷.

﹆ Shiri-bukura [尻フクラ], on [its] tray¹⁸.

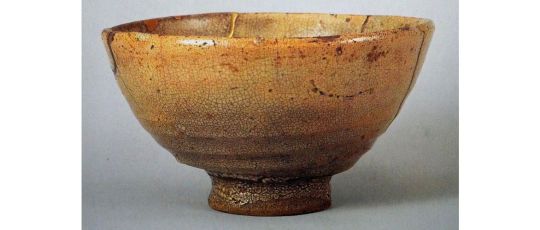

◦ Chawan shin-Seto [茶碗 新瀬戸]¹⁹.

◦ Mizusashi Shigaraki [水指 シカラキ]²⁰.

◦ On the tana: hishaku ・ futaoki [ヒシヤク ・ 蓋置]²¹.

Su [ス]²².

◦ Koboshi gōsu [コホシ 合子]²³.

_________________________

¹Shigatsu tsuitachi, asa [四月朔日、朝].

The Gregorian date was May 8, 1587.

The Fourth Lunar Month, which was classically known as U-zuki [卯月] (the month of U [卯] (Deutzia), which is a rather large shrub that flowers in great sprays of white, or pale-pink, blossoms at this time of year), marked the beginning of Summer, and Rikyū appropriately welcomes in the season during this chakai.

The guests were two important samurai, and it seems that Rikyū had traveled to Sakai to meet them upon their arrival from Kyūshū (where both of them were based) -- Sakai being the port at which larger vessels traveling from the west would berth. Though it is not known whether their ship docked that morning, or the previous evening, this chakai would, in either case, give these important guests time to rest and compose their minds before their upcoming meetings with Hideyoshi and his counselors.

Not wishing to receive such people in his private home*, Rikyū gave them chanoyu in the Shū-un-an [集雲庵], which he would have borrowed from Nambō Sōkei for the occasion. He probably escorted them to Hideyoshi's compound afterward (where he entertained their lord, Mōri Terumoto [毛利輝元], at a night gathering on the same day).

___________

*In East Asian cultures, important people were usually not entertained in ones private home; a more appropriate venue was always secured whenever possible.

²Sanjō shiki [三疊敷].

As mentioned above, this was (once again) Nambō Sōkei's Shū-un-an [集雲庵], with the mats changed for the furo season.

As always, when a tsuri-dana is present, the furo was placed on the opposite side of the mat (and so on the right, as shown in the sketch).

³Kobayakawa Takakage [小早川隆景].

Kobayakawa Takakage [1533 ~ 1597] was a daimyō and nobleman, who attained the position of chūnagon [中納言] (Middle Counselor to the Emperor), and the Junior grade of the Third Rank, through Hideyoshi's patronage. He was also the uncle of Mōri Terumoto [毛利輝元], being the third son of Mōri Motonari's [毛利元就; 1497 ~ 1571] principal wife (while Terumoto's father had been Motonari's eldest son) -- though Takakage had been adopted by the Kobayakawa family, becoming their 14th clan head.

He was probably visiting the capital (along with Yoshikawa Kurando and Mōri Terumoto himself) to converse with Hideyoshi about the upcoming Kyūshū campaign.

⁴Yoshikawa Kurando [吉川蔵人].

Yoshikawa Kurando [吉川蔵人; ? ~ 1617] was a samurai, and senior administrator* to the Fuchū Clan (Fuchū Han [府中藩]) of Tsushima [對馬]. Tsushima is the large island located between Kyūshū and the Korean peninsula, and the cooperation and assistance of Fuchū Clan would have been a desirable asset for Hideyoshi’s Kyūshū campaign to unify the Japanese islands, since troops would have to be sent by ship through waters controlled by the Lord of Tsushima, and any animosity could result in their passage being harried or obstructed.

__________

*Kuni-garō [國家老], a high-level retainer who functioned essentially as the civil administrator of his daimyō’s province.

⁵Sho [初].

The shoza.

With respect to the kane-wari:

- the toko held the chabana, suspended on the back wall, and so was han [半]*;

- the room had the furo, resting on a ko-ita, and so was han [半];

- and the tana had the kōgō and habōki, arranged side-by-side, with each of them coming into contact with a different kane, meaning it was chō [調].

Han + han + chō is chō, which is appropriate for a chakai held during the daylight hours.

__________

*Both Tanaka Sensho and Shibayama Fugen go into a discussion of why -- or whether it is possible -- to invert the order of displaying the chabana and the scroll during the daytime, without stopping to consider the meaning of the flowers that Rikyū used as his chabana.

The fact that the Enkaku-ji manuscript shows the chabana marked with a red spot clearly indicates that Rikyū wished to emphasize the arrival of the new season, and this is why he would have displayed the flowers first (since the bokuseki that he chose as the kakemono says nothing about the season at all).

Rikyū was a chajin par excellence, who expressed his heart through chanoyu; he was not an automaton who mindlessly imitated rigid forms. And on this occasion, the guests would have set sail from Kyūshū a day or two before (in other words, during the last days of the winter season); so Rikyū wished to emphasize that the season had changed while they were on their journey, and it now was summer. (Court robes, for example, were changed to the summer style from this day.)

⁶Ahiru-kago kakete [アヒル籠 カケテ].

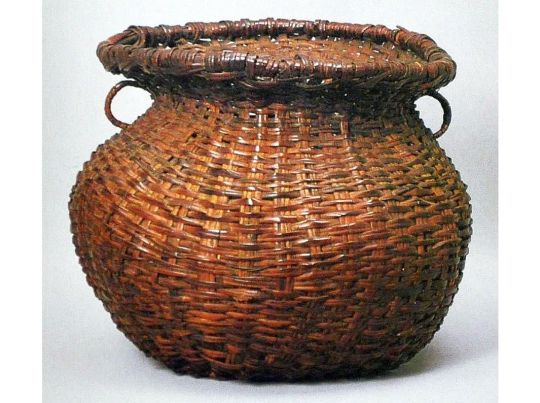

This was Rikyū's large basket hanaire.

His use of such a relatively large basket suggests that the chabana consisted of a number of long branches of unohana, which he arranged so that they would flood the tokonoma with their pristine blossoms.

In the Enkaku-ji manuscript, this entry is marked with a red spot, indicating that the chabana was one of the “special features” of the chakai. This, in turn, suggests that likely a profusion of unohana were arranged, since the idea would have been to emphasize the change of season.

⁷Unohana [卯花].

Unohana [卯の花] is the Japanese name of the shrub known botanically as Deutzia crenata. In early May this shrub is smothered with masses of white or pale-pink blossoms.

Since ancient times, the Fourth Month has commonly been referred to as U-zuki [卯月] -- the Month when Deutzia blossoms; and since ancient times the Japanese have traditionally gone quite mad over this shrub (when in bloom), festooning homes, public buildings, and even conveyances, with flowering boughs of Deutzia in every conceivable place they can be wedged -- since the arrival of this flower means that Summer is beginning.

⁸Ko-ita ni furo [小板ニ風爐].

This was probably the large Temmyō kimen-buro that had belonged to Yoshimasa, arranged on the ko-ita [小板] that Jōō had created for it.

When arranged in this kind of room (due to the location of the ro, the utensil mat was treated as if it were a daime -- albeit one without a sode-kabe -- even during the furo season), the ko-ita* is placed 2-sun back from the yū-yo [有余]†, and 9-me (4-sun 5-bu) from the heri, as shown in the following sketch.

Many modern schools teach that the ko-ita should be centered between the back wall and the naka-bashira, but that is not really correct -- at least insofar as the classical teachings are concerned‡.

__________

*As has been mentioned before, the original rule was that only the large furo (which is the only kind of furo that is supposed to be placed on a ko-ita [小板] -- this is why Rikyū did not need to say anything about the furo) could be used in the small room. While this dictum seems to have been relaxed by Rikyū's day, the rules for placement were laid down with regard to the ko-ita, and this is what I am discussing here.

†A yū-yo [有余] is a part of the mat on which nothing should be placed. The 2-sun at the front of the daime-gamae (which corresponded to the diameter of the naka-bashira) was yū-yo.

In the case of a room with a mukō-ro, the 2-sun in front of the front edge of the ro was yū-yo.

And, in both cases, when the utensil mat was a maru-jō [丸疊] (a full-length tatami, rather than a daime-tatami), the lower 1-shaku 5-sun (the space in front of the host's entrance) was also yū-yo.

‡Of course, the rise of modern chanoyu in the Edo period came about precisely because the classical teachings had either been lost, or were being ignored in light of (government sponsored) contemporary preferences.

⁹Kama unryū [釜 雲龍].

It seems that this was probably the original small unryū-gama that Rikyū had created for use with the large Temmyō kimen-buro.

As mentioned before, this kama had a lid made from a piece of sheet copper (which was imported for use as a roofing material) beaten into shape, which resembled bronze as it oxidized on exposure to heat. It also had kimen kan-tsuki, to match the furo with which it was used.

Rikyū had given both the furo and this kama to Hideyoshi, and he had probably brought them to Sakai to use for this chakai.

¹⁰Tana ni kōgō ・ habōki [棚ニ香合 ・ 羽帚].

Since Rikyū does not state otherwise*, the kōgō was probably his ruri suzume [瑠璃雀], which was his “ordinary kōgō†.”

The feathers from which the habōki was made are not known, though it would have been a go-sun-hane [五寸羽], as always in the small room.

__________

*Rikyū usually carefully recorded those occasions when he used his lacquered guri-guri kōgō [グリグリ香合].

Furthermore, the use of this lacquered kōgō (which was a Higashiyama go-motsu [東山御物] piece, and so a meibutsu kōgō) would have required the habōki to be placed horizontally in front of it, which would then change the tana from chō to han, and so disrupt the kane-wari.

†Strictly adhering to the rule of lacquered kōgō in summer, and ceramic kōgō in winter was a practice advocated by Jōō -- as it conformed (more or less) to the conventions of kōdō [香道] (from the ranks of which practitioners most of his earliest followers came). Rikyū, on the other hand, preferred to view this matter in terms of practicality: a ceramic kōgō was easy to clean, while a lacquered one could be easily damaged by the incense (including the lacquer being infiltrated by the aromatics of whatever sort of incense was placed in it), and so he felt it should be used only on special occasions.

¹¹Shiru imo-gara ・ sasage [汁 イモカラ ・ サヽケ].

Imo-gara [芋茎 or 芋莖]* are the petioles (leaf-stems) of either the taro or the sweet potato.

Sasage [大角豆] is the black-eyed pea (also known as the cowpea). This bean has extremely elongated pods, while the individual beans are white with a black spot encircling the hilum (the scar where the seed was attached to the ovary).

This was a sort of miso-shiru.

__________

*The word can also be written imo-gara [芋幹], which means sun-dried potato (taro or sweet potato) stems, and this is the meaning generally given to “imo-gara” today. However, this processed food is generally associated with autumn, while here Rikyū is hosting a chakai on the first day of summer. While he could have used dried stems, it seems more logical that he would have used fresh, green produce. Potato stems provide a sort of crispness that people of that time appear to have appreciated.

¹²Uzura senba-iri [鶉 センハイリ].

Uzura [鶉] is the quail. And senba-iri [船場煎り] -- where small birds were roasted on spits over a wood fire (while being basted with a sauce made of soy sauce, sake, mirin, sesame oil, and crushed garlic) -- was one of the special tastes of Sakai. This food was popularly sold at the food stalls that lined the wharves.

¹³Kuro-me [黒メ].

Kuro-me [黒布] is a kind of edible seaweed. It is usually served raw (either fresh, or reconstituted by soaking the dried kuro-me in water until soft) as a salad course, dressed with a mixture of rice vinegar, sesame oil, soy sauce, sugar, salt, and ginger juice.

¹⁴Ae-mono [アヘモノ].

Ae-mono [和え物] is a kind of mixed salad (chopped vegetables, hard fruits or things like yuzu-rind, and sometimes even raw fish), dressed with a soy-based sauce of some sort. Since Rikyū does not give any additional details, it is impossible to speculate on what the ae-mono might have contained.

¹⁵Iri-kaya ・ kawa-take [イリカヤ ・ 川茸].

The kashi.

Iri-kaya [煎り榧] are the roasted nuts of the Japanese allspice tree (also known, in English, as the Japanese nutmeg-yew, Torreya nucifera).

Kawa-take [川茸]* is a kind of freshwater seaweed that grows in flowing water. It can be eaten raw (sometimes with vinegar), or it can be cooked. However, because it is harvested from fresh water streams, it was usually eaten only during the colder months (when the dangers of enteric infection caused by contaminated river water will be at the minimum). Perhaps this was a miscopying of shiitake [椎茸] -- lightly salted charcoal-grilled shiitake mushrooms -- due to deterioration of the original Shū-un-an manuscript?

__________

*Tanaka Senshō's version gives the name as kawa-take [河茸].

¹⁶Go [後].

The goza.

With respect to the kane-wari:

- the kakemono was hung in the toko, making it han [半];

- the ko-ita furo remained as it was, with the mizusashi (with the bon-chaire and chawan arranged in front of it*) at its side†, and so was chō [調];

- and the hishaku and futaoki were arranged side by side on the tana, making the tana chō [調].

Han + chō + chō is han, which is appropriate for a chakai held during the daytime.

___________

*This arrangement is possible because of the small size of the chawan and chaire: the Unohana-gaki chawan is 3-sun 8-bu in diameter, while Rikyū’s Shiri-bukura chaire is 2-sun 2-bu in diameter. If the chawan or chaire were larger, arranging the chawan next to the bon-chaire like this would be difficult.

†I removed the tana from the sketch to make it clearer -- since the mizusashi sits largely beneath the tana during the furo season.

¹⁷Yoku-ryō-an [欲了庵].

Yoku-ryō-an [欲了庵] was the name by which Rikyū referred to this scroll -- which was perhaps one of his most prized possessions* -- and he indicates its importance with a red spot in the kaiki.

The scroll was written by the Yuan period Chán monk Liǎo-ān Qīng-yù [了庵清欲; 1288 ~ 1363].

___________

*The hon-shi [本紙] of this scroll can be opened to its full size at the following link:

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%95%E3%82%A1%E3%82%A4%E3%83%AB:Hogo_Liaoan_Qingyu.jpg

¹⁸Shiri-bukura bon ni [尻フクラ 盆ニ].

This was Rikyū's prized karamono chaire, which he used on the red-lacquered Chinese tray that is shown in the photo. It, likewise, is marked with a red spot in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, indicating that this was another of the featured utensils at this chakai.

Historically speaking, this was the first chaire to be used with a small chaire-bon*, and it established the precedent for Rikyū's teaching on this matter.

Though not mentioned, Rikyū would have used an ori-tame [折撓]† chashaku of his own making, carved to match this particular bon-chaire.

__________

*One which is only 2-sun larger than the chaire on all four sides.

†Ori-tame [折撓] literally means "[a branch] bent under the weight [of fruit]," and was Rikyū's term to refer to these chashaku that were bent at the node in the middle of the handle (as if weighed down by the matcha that would be scooped up with them).

¹⁹Chawan shin-Seto [茶碗 新瀬戸].

Shin-Seto [新瀬戸]* was Rikyū's term for white-glazed pottery fired at the Seto kilns, and almost certainly refers to a bowl made by Furuta Sōshitsu†.

The bowl shown above and below, known as Unohana-gaki [卯花墻], is probably one of the most famous “Shino” chawan -- though, curiously, nothing is known about its maker or transmission before it is mentioned as being in the collection of Katagiri Sadamasa (Sekishū). Sekishū, of course, spent the last part of his lifetime studying the chanoyu of Jōō and Rikyū, and his collection of tea utensils featured a number of pieces that are known to have been associated with one or the other of these two masters.

A bowl used by Rikyū (if only several times) would certainly have fit comfortably into his collection. Meanwhile, the box, rather than hako-gaki, has a small shikishi [色紙] pasted to the inside of the lid, on which Sadamasa wrote the poem yama-zato no unohana-gaki no Nakatsu-michi, yuki-fumi-wakeshi kokochi-koso sure [やまさとのうのはなかきのなかつみち 、 ゆきふみわけしここちこそすれ]‡.

It is not possible to be completely certain that this was the chawan that Rikyū used on this occasion. That said, both the poetic association and the bowl itself seem ideally suited to this chakai**.

___________

*This white-glazed ware, known as Shino [志野] pottery today, does not seem to have acquired this moniker until the Edo period.

Scholars are divided over whether this name was a corruption of the word for white (shiro [白]); or whether it refers to a (Korean) white chawan owned by Shino Sōshin [志野 宗信; 1441 ~ 1522], which this ware resembled, or to the type of chawan favored by one of the later masters of that school (the first three generations consisted of the original Korean family, while the present school descends from a Japanese disciple of the third generation, and the latter reference would appear to mean one of these Edo period masters).

“Shino” [シノ] might also simply be another “accidental contraction” of Rikyū’s expression “shin-Seto” [シンセト] resulting from deterioration in one of his memoranda -- such as we have seen from time to time while studying his manuscripts.

†The prototypes of many (if not most) of the original “Shino” pieces seem to have been made by Oribe; and only afterward (perhaps not until the Edo period) imitated by the professional potters working at that kiln -- when demand for pieces similar to the originals began to rise.

‡“In a mountain village, the unohana [cascades] over the walls [that line] the Nakatsu-michi: [the road, like] the trampled-down snow that divides [a snow-covered field in two], gives [the traveler] a feeling of comfort.”

While unohana-gaki [卯の花墻] is usually translated as “a bamboo fence over which unohana trails” (which is probably a direct reference to the underglaze iron oxide design on the chawan), kaki [墻] actually means an earthen wall (the lines represent the wooden supports for the mud-plaster structure). The Nakatsu-michi [中ツ道] was an ancient thoroughfare in Yamato province (in present-day Nara Prefecture) frequently used in poetry. The verse means that the blooming branches of the Deutzia cascading over the walls on both sides of the road, as it passes through a mountain village, remind the poet of a path that has been trampled down across a snow-covered field; and walking along this path (the “trampled-down path” is the actual Nakatsu-michi itself between the banks of unohana on both sides of the road), gives him a feeling of security and comfort (a path that has been trampled down across a field provides the traveler with sure footing -- since large stones or holes will not be lurking to cause him to stumble as they might under untouched snow).

The author or other particulars associated with this “old poem” have not been identified clearly (indeed, the diction does not appear to be all that “old”); and, in fact, it seems that this verse is unknown to precisely those poetic specialists who should be able to provide us with clarity on these points. Perhaps Sadamasa composed the poem himself? Or perhaps the poem dates back to Oribe -- who may have given this chawan its name? In either case, the phrase “yamazato” [山里] gives it a potentially suspicious connection with the chajin of the mid-sixteenth century (and after).

**This would also explain why Rikyū decided to arrange the unohana during the shoza -- so that the image of unohana could be spread across the entire chakai, and the chabana would not conflict directly with the chawan.

²⁰Mizusashi Shigaraki [水指 シカラキ].

This was Rikyū's Shigaraki mizusashi.

²¹Tana ni hishaku ・ futaoki [棚ニ ヒシヤク ・ 蓋置].

The futaoki most likely was one of Rikyū's take-wa [竹輪], since that was the most appropriate futaoki for the small room.

²²Su [ス].

This odd kana seems to have been a (perhaps intentional) miswriting of the kanji “mata” [又], meaning “and again.” It indicates that the utensil or utensils that follow were brought out from the katte (rather than being displayed in the room prior to the beginning of the koicha-temae).

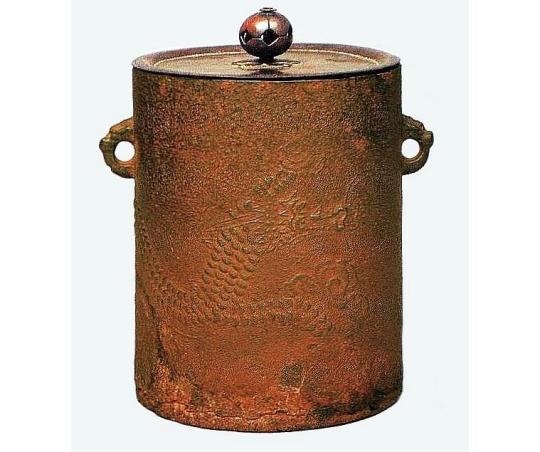

²³Koboshi gōsu [コホシ 合子].

A gōsu [合子] is a ritual vessel, made of bronze or sawari [四分一]*, provided with a lid, that was made for use when making offerings of cooked rice to the Ancestral Spirits in Korean jesa [제사 = 祭祀] ceremonies.

While the gōsu shown above has oxidized to a deep green color, it is said that Rikyū's gōsu was nearly black. While Furuta Sōshitsu used the gōsu with its lid†, it is not certain whether Rikyū used his in this way (or simply used it without the lid much like an ordinary koboshi).

__________

*Sawari [四分一] is a Korean bronze alloy that contains a certain percentage of silver (sawari [四分一] means “one part of four” or 25%). The silver kept the metal from oxidizing brown (like bronze): apparently the Koreans in the early fifteenth century (which is when this kind of alloy was produced) preferred these ritual vessels to remain a pale golden-yellow color, rather than turning brown. When sawari is very old, it eventually turns a deep black color (and this is the color that was preferred by Rikyū).

†When used with its lid, a hishaku of cold water was supposed to be placed inside before the gōsu was brought out into the tearoom, and the host had to be sure to carry it carefully with both hands.

The lid was left on the gōsu until it was time to empty the chawan into it, at which time the lid was lifted off, the lower edge was brushed with the fingers of the left hand above the bowl (to allow any drops of water to fall into the bowl rather than on the mat or on the ji-ita of the daisu), and then leaned against the side of the bowl (with the handle facing forward).

At the end of the temae the lid was closed again; and it was carried out of the room using both hands.

When using the daisu (or naga-ita), at the end of the temae it was taken back to the mizuya and emptied, and then returned to the daisu containing a hishaku of cold water.

The modern schools’ daisu-temae where the koboshi remains on the ji-ita throughout the temae actually derive from the original use of the gōsu (other sorts of koboshi were lowered to the mat and placed beside the host’s hip on the katte-side of the utensil mat: because of its lid, the gōsu should always contain some water, and because it contains cold water at the beginning of the temae, it does not get hot enough to damage the lacquer of the ji-ita when hot water is discarded into it during the temae; but because all other sorts of koboshi are empty, pouring hot water into them could theoretically heat the lacquer underneath to the point where, over time, the ji-ita could be damaged, hence they are moved onto the mat to protect the daisu).

1 note

·

View note