#Lynda roscoe Hartigan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Courtesy Albina Felski.

Felski, who began painting in 1960, wrote: "Im very busey [sic] around the house and I work in a factory I paint in fall, winter & spring time I enjoy summers the most." In 1945 she came to Chicago from Canada and worked for twenty-seven years in an electronics factory, doing machine and assembly work. Like The Circus, [SAAM 1986.65.108] her paintings are usually on four-by-four-foot canvases, and are brightly colored and extremely detailed. Though she has an easel, Felski prefers to paint with her canvas spread flat on a table. In this work, she includes virtually every conceivable circus act, particularly those involving animals. She was often inspired to paint animals—bears, deer, mountain goats, etc.—from photographs taken by her brothers in their native British Columbia.

Lynda Roscoe Hartigan Made with Passion: The Hemphill Folk Art Collection in the National Museum of American Art (Washington, D.C. and London: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990)

0 notes

Text

Book 377

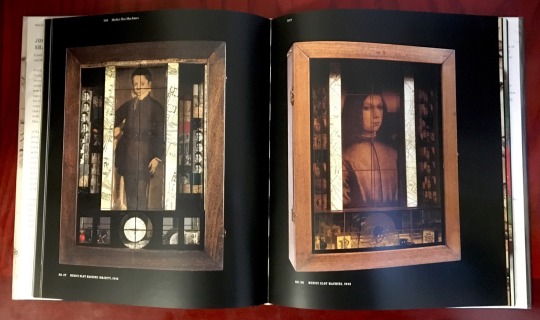

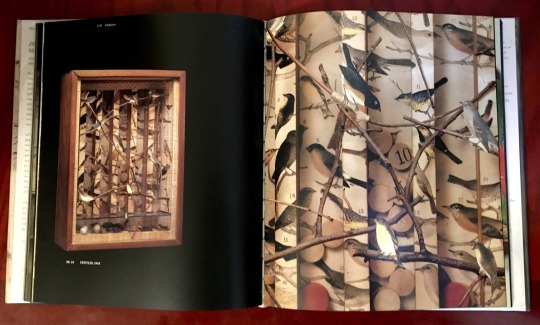

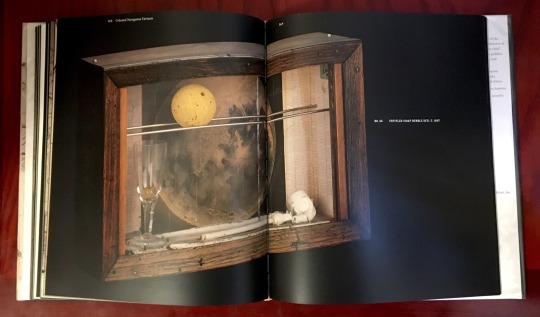

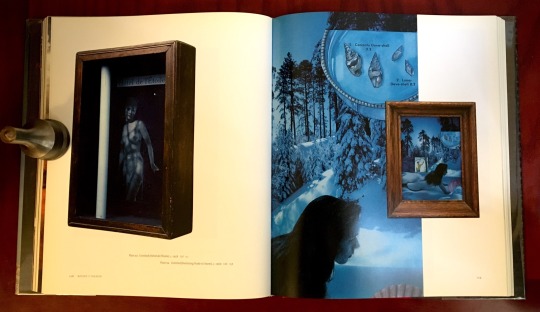

Joseph Cornell: Shadowplay…Eterniday

Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, Walter Hopps, Richard Vine, and Robert Lehrman

Thames & Hudson 2003

Every few years or so, someone publishes a new book on Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) to mark a new retrospective or anniversary, and I seemingly need to buy all of them. This one was published to celebrate the centennial of Cornell’s birth, and it’s very well done. With over 200 illustrations of Cornell’s work, many in detail, it’s an impressive volume. What’s different about this book are the various perspectives offered about Cornell and his work from the four essayists, and the DVD-ROM included with the book that includes a compendium of the art and source materials, commentary by scholars and critics, and access to his experimental films.

#bookshelf#illustrated book#library#personal library#personal collection#books#book lover#bibliophile#booklr#joseph cornell#shadowplay eterniday#Lynda roscoe hartigan#Walter hopps#Richard vine#Robert lehrman#thames & hudson#Art

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Like the Gaudy Butterfly…”: A Discussion on Lace Tatting

By: Lisa Timmerman, Executive Director

The Weems-Botts Museum will be opening their doors soon to safely welcome visitors as we enter Phase 3. One of our treasures, our framed and donated lace tatting, is ready to take the spotlight again! But what is tatting? Why do we sell a Lace Tatting Kit in our Gift Shop? And why are doilies so ubiquitous?

Like crochet and knitting, tatting is a type of needlework that uses thread and tools (shuttle, needle, crochet hook) to create intricate and decorative knotwork. While this type of work could have evolved from netting and ropework, we find tatting popular throughout Europe and Great Britain in the 19th century with different names: frivolite in France, knotting in England, Schiffchenarbeit in Germany, and tatting in America. People used tatting to either accent an item (such as our 19th century petticoat with lace tatting on bottom – not on display!) or create delicate pieces, such as doilies.

Many reading this article may already know or could easily recognize tatting thanks to the surge of popularity it experienced in the 1930s-1950s and then again in the 1970s. It was popular throughout the Victorian era with Eleonore Riego de la Branchardiere publishing numerous needlework manuals/guides, such as Golden Stars in Tatting and Crochet, 1861, currently available via Project Gutenberg. Mlle Riego de la Branchardiere started with some reassurances, “The following Designs are formed by a very simple combination of Tatting and Crochet, the more elaborate style of both Works being avoided, so that any Lady with a knowledge of the first rules of each Art will be able to accomplish the patterns without the least difficulty, the Stars and Diamonds being made in Tatting and afterwards worked round with loops of chain Crochet.” Thank goodness! Let us check in with an anonymous author who included a chapter on tatting in the 1844 publication, The Ladies’ Work-Table Book; Containing Clear and Practical Instructions in Plain and Fancy Needlework, Embroidery, Knitting, Netting, and Crocheting. This author boldly declared the purpose and high importance of needlework specifically aimed at the female population, “If it be true that “home scenes are rendered happy or miserable in proportion to the good or evil influence exercised over them by woman—as sister, wife, or mother”—it will be admitted as a fact of the utmost importance, that every thing should be done to improve the taste, cultivate the understanding, and elevate the character of those “high priestesses” of our domestic sanctuaries. The page of history informs us, that the progress of any nation in morals, civilization, and refinement, is in proportion to the elevated or degraded position in which woman is placed in society; and the same instructive volume will enable us to perceive, that the fanciful creations of the needle, have [iv]exerted a marked influence over the pursuits and destinies of man.” The instructions for tatting included open stitches, stars (a popular theme), and common tatting edges. This author concluded by reinforcing their opinion that needlework contained a Christian imperative and service, a way for women to “endeavor” and develop their “moral goodness”, “We were not sent into this world to flutter through life, like the gaudy butterfly, only to be seen and admired.”

(Source: Project Gutenberg Ebook of Golden Stars in Tatting and Crochet by Eleonore Riego de la Branchardiere)

However, needlework and crafted items, such as doilies, should not be viewed as crafted (and useful!) curiosities only. While women’s magazines published many ideas, guides, patterns, etc. in the early 20th century, artists also used these same objects in more meaningful expressions. Horace Pippin survived but sustained an injury during WWI that limited the mobility of his arm. Using small canvasses and drawing upon his experiences, knowledge, and imagination, his work gained national attention and the Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibited his items in their “Masters of Popular Painting: Exhibitions of Modern Primitives of Europe and America”. Supporters such as Robert Carlen and Albert Barnes helped boost his popularity through solo exhibitions and purchases. According to scholar Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, “Equally crucial is valuing these diverse subjects for their autobiographical, regional, and cultural under- pinnings—underpinnings that link them irrevocably to Pippin’s more celebrated paintings of war, spiritual harmony and African-American life”. Notably, Pippin painted numerous doilies in his artwork, whether draped across seating furniture or tables. His paintings featured an impressive depth and scope – whether a reflection/recollection on the war, social injustices, slavery, or famous events such as the execution of John Brown. He remarked, “The pictures . . . come to me in my mind and if to me it is a worthwhile picture I paint it . . . I do over the picture several times in my mind and when I am ready to paint it I have all the details I need." Just studying the doilies alone show his attention and mastery to still life and detail.

So why are doilies ubiquitous? We could discuss reasons ranging from potential cost to efficiency and décor, but doilies are definitely still a “thing”. While we could joke about its function as a glorified coaster, it is hard not to be excited when opening a family chest and discovering these delightful items crafted by our families and friends.

(Sources: Project Gutenberg Ebook of Golden Stars in Tatting and Crochet by Eleonore Riego de la Branchardiere; Project Gutenberg Ebook of The Ladies Work-Table Book, by Anonymous; The Spruce Crafts: What is Tatting?; Jonathan Boos: Specializing in 20th Century American Art: The Floral Still Lifes of Horace Pippin”; National Gallery of Art: Pippin’s Story)

#museumfromhome#destinationdumfries#lace#doilies#collection#community#crafts#needlework#horace pippin

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

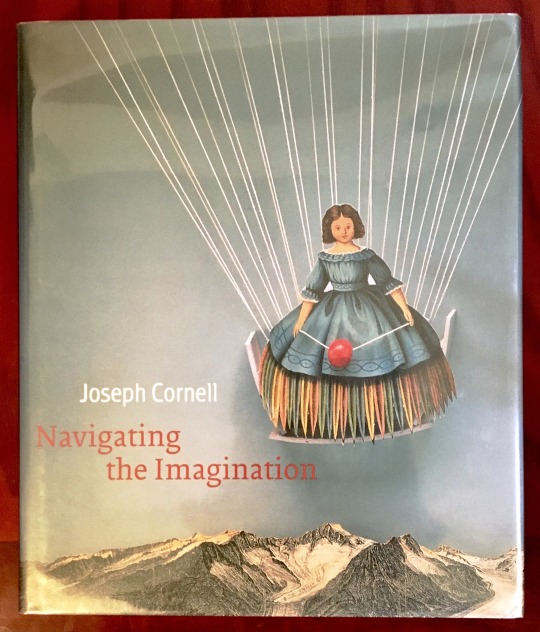

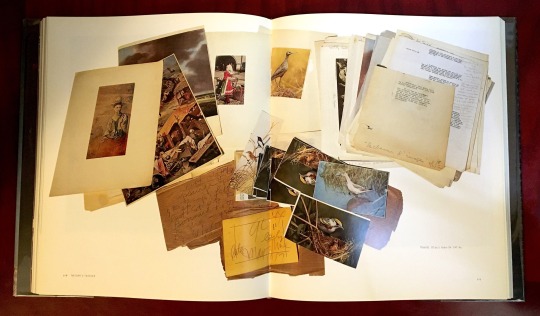

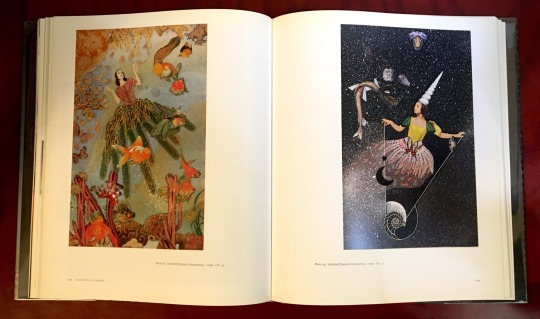

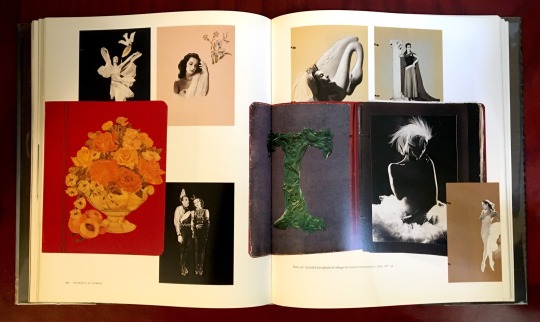

Book 385

Joseph Cornell: Navigating the Imagination

Lynda Roscoe Hartigan

Peabody Essex Museum / Smithsonian American Art Museum / Yale University Press 2007

Published to accompany a traveling retrospective of Joseph Cornell’s (1903-1972) work in 2007 and 2008, this book is a beautiful tribute to an artist whose work defies easy categorization. Of the two large-format books I own about Cornell, I would have to give the edge to this one in terms of which is the better book. First off, this one is beautifully bound in full red cloth. Secondly, it offers much more of Cornell’s illuminating source material, some rarer pieces that are not usually reproduced, and even includes some previously unpublished art.

#bookshelf#illustrated book#library#personal library#personal collection#books#book lover#bibliophile#booklr#joseph cornell#navigating the imagination#Lynda roscoe Hartigan#Peabody essex museum#smithsonian american art museum#Yale university press#Art

4 notes

·

View notes